Abstract

Adolescent and young adult (AYA) participation in cancer clinical trials (CCTs) is suboptimal, hindering further improvements in survival, quality of life, and basic understanding of cancer pathophysiology in this population. Prior studies have identified barriers and facilitators to AYA CCT enrollment; however, few interventional studies have attempted to address these barriers and measure tangible changes. In September 2020, a task force was established to address CCT enrollment barriers at a multi-institutional level utilizing a quality improvement collaborative model for improvement. The AYA Trial Access Quality Initiative (ATAQI) was developed with the goal of bring multidisciplinary teams together across multiple sites to learn, apply and share their methods of improvement. It uses a structured process of learning sessions lead by quality improvement and clinical experts who help facilitate learning and problem solving which are followed by action phases. During the pilot phase of the collaboration, one key driver of CCT enrollment in AYA’s will be addressed: communication between adult and pediatric oncology by implementation of various interventions at sites. The number of AYAs screened for and enrolled on CCTs will be tracked over the course of the collaborative along with the process measures. It is expected that the interventions will promote engagement of stakeholders in the process of screening AYA oncology patients for eligibility on CCTs. This will hopefully create a favorable environment conducive for increasing enrollment on CCTs and lead to the development of a system-wide quality improvement framework to improve AYA CCT enrollment.

Keywords: Adolescent and Young Adult, Cancer, Clinical Trial Enrollment, Quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

Overall survival for patients diagnosed with cancer in the United States has increased steadily over the past five decades. An improved understanding of cancer biology has facilitated major advancements in cancer therapeutics. Cancer clinical trials (CCTs) have been integral in this process; however, enrollment is not equal across patient populations depending on their ethnic or racial background, socioeconomic status, cancer subtype, geographic location, and treatment center. Participation in CCTs is low among adolescents and young adults (AYAs, age 15 to 39 years at diagnosis), which has hindered improvements in survival, quality of life, and basic understanding of cancer pathophysiology in this population. Prior studies have identified barriers and facilitators to AYA CCT enrollment; however, few interventional studies have attempted to address these barriers and measure tangible changes.[1–8]

Our understanding of the barriers and facilitators to enrollment of AYAs on to CCTs has deepened in recent years and several efforts have been implemented on the national and local levels to improve overall accrual. Systems-level factors that impact enrollment include availability of CCTs at both the national and institutional levels, location of treatment centers, and adequate research infrastructure and funding to support clinical trial implementation, among others.[9] At the national level, interventions to address barriers to enrollment have included funding for the creation of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) to bring CCTs to community-based treatment centers and the reorganization of CCT cooperative groups with the creation of NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN). These two programs have allowed for centralization of data collection, creation of a central institutional review board and expansion of biobanking. Additionally, recent collaboration among pediatric and medical oncology CCT network groups has resulted in the development of joint CCTs that span the full AYA age range. At the institutional level, AYA programs and clinics jointly led by pediatric and medical oncology have been established to address the unique needs of this population. Improving access to CCTs is a key focus of many of these programs.[10] In addition to trial availability, physician factors such as time required to enroll patients, knowledge of available trials and willingness to enroll on open CCTs also impact overall accrual. At the patient level, barriers to enrollment include personal beliefs, knowledge, developmental maturation, socioeconomic status, insurance coverage, family and community support, and medical condition at the time of diagnosis.[11, 12]

There has been a lack of prospective studies focused on objective and measurable interventions to improve AYA accrual. Collaboration within and between cooperative cancer groups has resulted in improved patient outcomes and advanced our understanding of disease; however, enrollment on jointly developed and supported clinical trials still face many barriers. In 2018, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) AYA Oncology Discipline Committee[1] developed an international network of AYA Responsible Investigators (RIs) consisting of more than 140 individuals from demographically and geographically diverse sites that serve a variety of distinct roles at their respective institutions, including physicians, nurse practitioners, nurse navigators and research staff. The primary purpose of AYA RIs is to optimize AYA enrollment onto COG-led and other NCTN trials in which COG is partnering. The primary mechanism through which the AYA RI Network supports enrollment is by providing education and peer support to institutional AYA RIs through a series of informal webinars. Additionally, a survey was done to assess barriers and facilitators to AYA accrual at COG sites. However, this established network has not yet been utilized for quality improvement (QI) initiatives or collaborative approaches to improve CCT enrollment. Based on data gathered through the RI Network, several key targets for local intervention were identified, including improving communication between pediatric and medical oncology, implementing an AYA CCT screening process, and increasing local availability of trials.

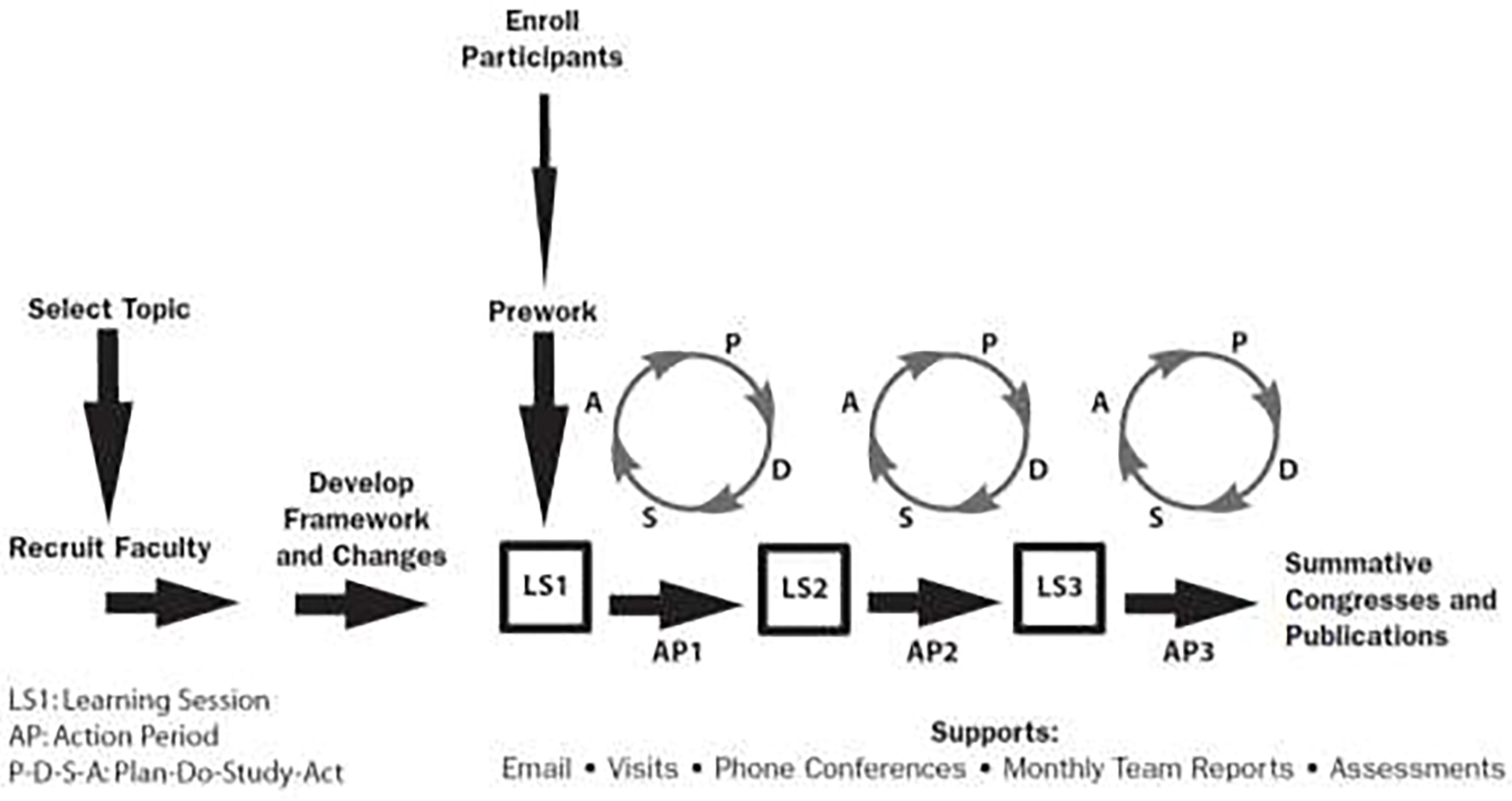

In September 2020, a task force – ATAQI (AYA Trial Access Quality Initiative) – was established to tackle identified CCT enrollment barriers at a multi-institutional level. Given the existing collaborative clinical research infrastructure in place through the RI network, a quality improvement collaborative (QIC) approach was chosen based on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s breakthrough series (BTS) design.[13] This model uses multidisciplinary teams from multiple sites that join together to learn, apply and share their methods of improvement. It uses a structured process of learning sessions lead by QI and clinical experts who help facilitate learning and problem solving which are followed by action phases. Action phases will have teams doing Plan-Study-Act-Do (PDSA) cycles as small tests of change. (Figure 1) This model was chosen because it: 1) allows for QI expertise to be shared among the collaborative, which may be lacking at an individual institution; 2) facilitates the ability to test and troubleshot different interventions in short order and allows centers to learn from each other; and 3) promotes the sharing and pooling of process and outcome data, allowing for data benchmarking and facilitates further knowledge acquisition among the larger group. The use of QICs have been successful across a board range of diseases and populations, such as ImproveCareNow for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease,[14, 15] the Vermont-Oxford Network for neonatal care delivery and T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative for patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.[16]

Figure 1.

Framework for a quality improvement collaborative. Sites are recruited to develop the framework for the initiative and select interventions. A series of PDSA cycles are guided by expert driven learning sessions, and frequent communication ensures all sites are progressing through the project. Source: The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2003. (Available on www.ihi.org)

The infrastructure and avenue presented by the COG AYA RI Network provides an opportunity to design and implement cooperative, multi-institutional initiatives, the findings of which can be used to influence and inform future efforts across individual sites. Thus, there are two global aims of ATAQI: 1) utilize the existing COG AYA RI network to develop a research cooperative infrastructure for multi-institution QI initiatives; and 2) improve CCT enrollment in AYA cancer patients. The specific aims of this collaborative are to:

Organize a group of 6–8 institutions to engage in a 12-month-long pilot QI collaborative.

Increase the number of AYA patients screened for eligibility of available AYA-relevant CCTs by 25% of baseline at each site over the pilot time period.

Increase the number of AYA patients enrolled on available AYA-relevant CCTs, including therapeutic, supportive care and registry studies by 10% of baseline at each site over the pilot time period.

Formalize the collaborative and disseminate findings and methods to other centers within the larger RI/AYA network.

DESIGN and METHODS

Context

In November 2020, members of the COG AYA RI committee came together to brainstorm and develop actionable steps to address accrual rates in AYA patients. Various key drivers to successful AYA enrollment were identified based on previous publications and COG AYA RI network shared experiences based on known barriers and facilitators. (Figure 2) The key drivers selected were communication between pediatric and medical oncology, availability of AYA relevant trials and patient willingness to enroll.[1, 3, 17, 18] The availability of AYA relevant trials refers to trials open through the NCTN for which AYA patients are eligible to enroll based on diagnosis, age and eligibility criteria as well as access to availability of NCTN trials at the site for the patient, which in turn is determined by various regulatory and other institutional constraints. Patient willingness to enroll is impacted by several factors such as trust, financial constraints, time, and understanding of the trial. Over the following months, this group determined that the creation of a QIC would be the best framework to address the problem. The pilot group will consist of 6–8 sites that are members of the AYA RI initiative network and include diverse AYA cancer care settings. All sites have pediatric and medical oncologists at their institutions and have access to the NCTN AYA trial portfolio. Team structure and expectations are outlined in Table 1.

Figure 2.

AYA enrollment key driver diagram. A SMART AIM serves as the cornerstone of a key driver diagram outlining multiple interventions designed to achieve listed secondary objectives, and ultimately the SMART AIM itself.

Table 1:

AYA Trial Access Quality Initiative Structure and Expectations

| Human Resources | Responsibilities and Details | Time commitment |

|---|---|---|

| Executive Sponsor | Authorizes system level changes | Virtual/In-person 1–2 day learning sessions (3 total) |

| Provider Champions | Physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant, with a minimum of one pediatric and one medical champion from each disease group | Participation in monthly pilot group calls |

| Data Collection/Entry Personnel | Responsible for collecting and entering data on process and outcome measures | Monthly data collection and entry |

| Project Manager | Coordinate and support team with facilitation of PDSAs to test selected factors and submission of data into AYA QI database | Bi-weekly or monthly team meetings at the local institution |

During the pilot phase of the collaboration, one key driver will be addressed: communication between adult and pediatric oncology. Communication between providers was chosen based on literature review and expert option of the planning group members that identified this area has a common facilitator or barrier based on the frequency and quality of interactions between the two teams.[3, 8] How oncology care is organized can differ depending on the size of the institution, the number of providers and the volume of cancer diagnosis cared for. These differences and fragmentation due to specialized care often create a further layer of complexity in communication among providers

For the pilot, each site will coordinate their pediatric and medical oncology teams to improve their communication based on their local structure and needs with one team per site. There are various mechanisms to improve institutional communication between pediatric and medical oncology teams regarding open trials and many sites have their own processes to achieve this.[3, 4, 19] We chose three interventions to improve communication. Prior to the first learning lesion, teams will do required pre-work which will include creating their team, gathering baseline data about their institution(s), and determining what intervention they will implement. (Figure 2) Following the initial phase, this will be expanded to additional sites.

Interventions

As noted, the key driver that will be addressed during the pilot phase is “communication between adult and pediatric oncology.” There are many interventions that may address this key driver as shown in the key driver diagram. (Figure 2) For the pilot study, three interventions were identified which could be implemented at institutions of varying sizes, and without the input of significant financial resources or excessive burden on providers and research staff. Each site will choose one of three interventions to try to address AYA accrual:

Creation of a joint pediatric and medical tumor board

Creation of a dashboard of open CCTs that can be seen by all providers

Foster weekly communication to discuss newly diagnosed AYA patients and open CCTs between pediatric and medical teams

Measures

Outcome measures

The number of AYAs screened for and enrolled on CCTs will be tracked over the course of the collaborative. A patient will be considered screened for CCT enrollment if available CCTs at the participating site were reviewed for the patient. An AYA will be deemed eligible if the patient meets criteria for enrollment set by the specific protocol. An AYA will be termed approached if an eligible patient who meets enrollment criteria is presented with the trial. Lastly, a patient will be considered enrolled if the patient consents and enrolls on the CCT.

Process measures

Analyzing each step individually will help teams to facilitate changes to the process. Process data will differ depending on what intervention is implemented. For example, sites that choose to create a joint tumor board will track frequency of and participation in the meeting, the number of patients discussed. Sites that elect to create a dashboard of clinical trials will track how frequently the dashboard is accessed by medical and pediatric oncology providers. For sites that choose to foster weekly communication, the type of communication utilized, and how frequently that communication is accessed by medical and pediatric oncologists will be tracked. For all interventions, sites will track the number of available AYA-relevant CCTs, the number of AYAs screened and enrolled on a CCT, and whether patients required a transfer of care to enroll. During action phases, each site will collect and study these measures as they work through their PDSA cycles. This data, as well as changes to the process, will be shared during learning sessions by each site. This shared learning will help facilitate and expedite improvements for the group at large. Process data about participation in learning sessions and data entry will be tracked for the entire collaborative. Finally, institutional demographics will be collected for each site, including practice size and setting. (Supplemental Figure 1)

DISCUSSION

The successful enrollment of an AYA onto a CCT requires multiple, unobstructed steps. The complexity of this process has led to system-, institution-, provider- and patient-level barriers. Recent studies have identified these multilevel barriers to CCT enrollment; however, prior research seeking to improve enrollment has largely been conducted in single institutions, most of which have been academic medical centers. This likely reduces the generalizability of study findings, misses the experiences of community-based institutions where most AYAs receive their cancer care and limits the ability to compare experiences across institutions.

There is no single solution to improving AYA CCT enrollment across sites as each site must tailor interventions to their individual resources, providers, patients, and system. Therefore, providing a quality improvement framework permits flexibility and leaves the freedom of how to implement the intervention to each institution. The AYA RI Network provides an avenue to learn from each other’s experiences and the many shared barriers and facilitators affecting different systems that can be targeted in individualized ways. A stepwise QI approach with iterative optimization of interventions based on lessons learned during implementation is a novel approach in both AYA oncology and in addressing CCT enrollment disparities. ATAQI, a multi-institutional, collaborative effort led by stakeholders at various sites, is well-suited to pilot interventions targeted toward potentially modifiable, site-level factors that influence AYA CCT enrollment. This pilot can inform longer term studies evaluating the impact of such initiatives on CCT enrollment and related outcomes.

Increased interaction via tumor boards have been effective in fostering communication between different services and disciplines.[20] Tumor boards represent an opportunity to review open trials, identify eligible patients, and identify optimal treatment approaches for patients with rare cancers and/or complicated presentations. Regular attendance and visibility of AYA team members at shared multidisciplinary tumor boards (MTBs) is crucial to establish referral networks, enable ongoing screening of eligible patients and facilitate enrollment. The development of standard communication between key AYA stakeholders and all oncology providers via email to capture eligible AYAs in real-time improved access and referral to NCTN AYA CCTs presenting to different oncology providers at an academic site. (Grimes verbal communication) None of these interventions have previously been tested as a multi-institutional collaborative as described here in ATAQI.

Potential Challenges

There are known challenges and limitations that need to be considered for this QI CCT initiative. As this is a limited institution pilot initiative, the participating sites may not be completely representative of the multitude of cancer care settings, thus limiting the generalizability of the initiative. These efforts will need to be expanded to additional sites to measure their impact across institutions with varied resources. Further, CCT enrollment is a complicated process and several barriers to AYA enrollment likely exist at each site. Thus, implementation of one change may not result in a meaningful change in enrollments.[21] However, the primary aim of the project is to assess the feasibility of creating a Quality Improvement Collaborative within a well-established research structure to test multiple interventions, with the goal of adapting them in larger multi-institutional studies. Changing hardwired processes that are often dependent on available resources and individual stakeholders is a challenge that takes time. Acknowledging the feasibility of implementing a change in the process and its acceptance at the site is a useful and important first step toward the goal of increasing enrollment.

Expectations and Future Directions

Based on what is known about barriers to AYA enrollment at various institution types, it is expected that interventions will, at minimum, promote engagement of stakeholders in the process of screening AYA oncology patients for eligibility on CCTs. This will hopefully create a favorable environment and tangible pathways conducive for boosting AYA enrollment on CCTs. We expect we will be able to create a system-wide framework that facilitates the awareness of available AYA CCTs. Paired with the increasing number of AYA collaborative trials available in the NCTN, we hope this will lead to increased enrollment. An indirect benefit of this initiative is the expectation that sites will collect and optimize tracking of AYA patient and CCT enrollment numbers. If the pilot is successful, the intervention can be expanded to more sites and will provide an evidence-based quality improvement approach to address local enrollment barriers.

Supplementary Material

Funding/Support

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health [grant number UG1 CA189955 and U10CA180886] (MR).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The funders had no role in the design of the study, conduct of the study, analysis, interpretation of data, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations:

- AYA(s)

adolescent(s) and young adult(s)

- CCT

cancer clinical trials

- QI

quality improvement

- QIC

quality improvement collaborative

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roth M, Mittal N, Saha A, Freyer DR: The Children’s Oncology Group Adolescent and Young Adult Responsible Investigator Network: A New Model for Addressing Site-Level Factors Impacting Clinical Trial Enrollment. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2020, 9(4):522–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw PH, Hayes-Lattin B, Johnson R, Bleyer A: Improving enrollment in clinical trials for adolescents with cancer. Pediatrics 2014, 133 Suppl 3:S109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittal N, Saha A, Avutu V, Monga V, Freyer DR, Roth M: Shared barriers and facilitators to enrollment of adolescents and young adults on cancer clinical trials. Sci Rep 2022, 12(1):3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siembida EJ, Loomans-Kropp HA, Trivedi N, O’Mara A, Sung L, Tami-Maury I, Freyer DR, Roth M: Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to clinical trial enrollment among adolescents and young adults with cancer: Identifying opportunities for intervention. Cancer 2020, 126(5):949–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLeod KL, Skinner AM, Beaupin LK, Vadaparampil ST, Fridley BL, Reed DR: Clinical Trial Availability by Location for 1000 Simulated AYA Patients. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2022, 11(1):95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins CL, Malvar J, Hamilton AS, Deapen DM, Freyer DR: Case-linked analysis of clinical trial enrollment among adolescents and young adults at a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2015, 121(24):4398–4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas SM, Malvar J, Tran HH, Shows JT, Freyer DR: A prospective comparison of cancer clinical trial availability and enrollment among adolescents/young adults treated at an adult cancer hospital or affiliated children’s hospital. Cancer 2018, 124(20):4064–4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siembida EJ, Loomans-Kropp HA, Tami-Maury I, Freyer DR, Sung L, Crosswell HE, Pollock BH, Roth ME: Barriers and Facilitators to Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Trial Enrollment: NCORP Site Perspectives. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2021, 5(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unger JM, Cook E, Tai E, Bleyer A: The Role of Clinical Trial Participation in Cancer Research: Barriers, Evidence, and Strategies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2016, 35:185–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw PH, Boyiadzis M, Tawbi H, Welsh A, Kemerer A, Davidson NE, Ritchey AK: Improved clinical trial enrollment in adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology patients after the establishment of an AYA oncology program uniting pediatric and medical oncology divisions. Cancer 2012, 118(14):3614–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forcina V, Vakeesan B, Paulo C, Mitchell L, Bell JA, Tam S, Wang K, Gupta AA, Lewin J: Perceptions and attitudes toward clinical trials in adolescent and young adults with cancer: a systematic review. Adolesc Health Med Ther 2018, 9:87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchanan ND, Block R, Smith AW, Tai E: Psychosocial barriers and facilitators to clinical trial enrollment and adherence for adolescents with cancer. Pediatrics 2014, 133 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S123–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilo CM: A framework for collaborative improvement: lessons from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Breakthrough Series. Qual Manag Health Care 1998, 6(4):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crandall WV, Margolis PA, Kappelman MD, King EC, Pratt JM, Boyle BM, Duffy LF, Grunow JE, Kim SC, Leibowitz I et al. : Improved outcomes in a quality improvement collaborative for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatrics 2012, 129(4):e1030–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savarino JR, Kaplan JL, Winter HS, Moran CJ, Israel EJ: Improving Clinical Remission Rates in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease with Previsit Planning. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2016, 5(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alonso GT, Corathers S, Shah A, Clements M, Kamboj M, Sonabend R, DeSalvo D, Mehta S, Cabrera A, Rioles N et al. : Establishment of the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative (T1DX-QI). Clin Diabetes 2020, 38(2):141–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson C, Smitherman AB, Meernik C, Edwards TP, Deal AM, Cannizzaro N, Baggett CD, Chao C, Nichols HB: Patient/Provider Discussions About Clinical Trial Participation and Reasons for Nonparticipation Among Adolescent and Young Adult Women with Cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2020, 9(1):41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isack A, Santana VM, Russo C, Klosky JL, Fasciano K, Block SD, Mack JW: Communication Regarding Therapeutic Clinical Trial Enrollment Between Oncologists and Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2020, 9(5):608–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed DR, Oshrine B, Pratt C, Fridgen O, Elstner C, Wilson L, Soliman H, Lee MC, McLeod HL, Shah B et al. : Sink or Collaborate: How the Immersive Model Has Helped Address Typical Adolescent and Young Adult Barriers at a Single Institution and Kept the Adolescent and Young Adult Program Afloat. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2017, 6(4):503–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mobley EM, Swami U, Mott S, Ounda A, Milhem M, Monga V: A Retrospective Analysis of Clinical Trial Accrual of Patients Presented in a Multidisciplinary Tumor Board at a Tertiary Health Care Center and Associated Barriers. Oncol Res Treat 2020, 43(5):196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freyer DR, Seibel NL: The Clinical Trials Gap for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Recent Progress and Conceptual Framework for Continued Research. Curr Pediatr Rep 2015, 3(2):137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.