ABSTRACT

Bacterial enhancer-binding proteins (bEBPs) acquire a transcriptionally active state via phosphorylation. However, transcriptional activation by the dephosphorylated form of bEBP has been observed in DctD, which belongs to Group I bEBP. The formation of a complex between dephosphorylated DctD (d-DctD) and dephosphorylated IIAGlc (d-IIAGlc) is a prerequisite for the transcriptional activity of d-DctD. In the present study, characteristics of the transcriptionally active complex composed of d-IIAGlc and phosphorylation-deficient DctD (DctDD57Q) of Vibrio vulnificus were investigated in its multimeric conformation and DNA-binding ability. DctDD57Q formed a homodimer that could not bind to the DNA. In contrast, when DctDD57Q formed a complex with d-IIAGlc in a 1:1 molar ratio, it produced two conformations: dimer and dodecamer of the complex. Only the dodecameric complex exhibited ATP-hydrolyzing activity and DNA-binding affinity. For successful DNA-binding and transcriptional activation by the dodecameric d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex, extended upstream activator sequences were required, which encompass the nucleotide sequences homologous to the known DctD-binding site and additional nucleotides downstream. This is the first report to demonstrate the molecular characteristics of a dephosphorylated bEBP complexed with another protein to form a transcriptionally active dodecameric complex, which has an affinity for a specific DNA-binding sequence.

IMPORTANCE

Response regulators belonging to the bacterial two-component regulatory system activate the transcription initiation of their regulons when they are phosphorylated by cognate sensor kinases and oligomerized to the appropriate multimeric states. Recently, it has been shown that a dephosphorylated response regulator, DctD, could activate transcription in a phosphorylation-independent manner in Vibrio vulnificus. The dephosphorylated DctD activated transcription as efficiently as phosphorylated DctD when it formed a complex with dephosphorylated form of IIAGlc, a component of the glucose-phosphotransferase system. Functional mimicry of this complex with the typical form of transcriptionally active phosphorylated DctD led us to study the molecular characteristics of this heterodimeric complex. Through systematic analyses, it was surprisingly determined that a multimer constituted with 12 complexes gained the ability to hydrolyze ATP and recognize specific upstream activator sequences containing a typical inverted-repeat sequence flanked by distinct nucleotides.

KEYWORDS: bacterial enhancer-binding protein, dephospho-DctD/dephospho-IIAGlccomplex, dodecameric conformation, upstream activator sequences

INTRODUCTION

Transcription factors capable of binding to specific DNA sequences located in the upstream regions, the so-called upstream activator sequences (UASs) (1), of target genes have been named bacterial enhancer-binding proteins (bEBPs) (2). Typically, members of Group I bEBPs must be phosphorylated via a cognate sensor kinase-mediated phosphorelay and oligomerized into appropriate multimeric forms exhibiting ATPase activity to successfully become transcriptional activators (3). DctD, a member of Group I bEBPs, has been initially isolated as the main regulator for the expression of the dicarboxylic acid transporter (DctA) in a nitrogen-fixing Rhizobium species (4). Its sensor kinase DctB, comprising a two-component system (TCS) with the response regulator DctD, senses ambient dicarboxylic acids and phosphorylates DctD, thereby activating the transcription of dctA genes (5).

DctBD systems have also been found in many bacterial species, including the model foodborne pathogen Vibrio vulnificus, in which RpoN-initiated transcription of two distinct gene clusters for exopolysaccharides (EPS) biosynthesis, EPS-II and EPS-III clusters, is activated by DctBD (6). These findings demonstrate that the regulatory roles of DctD may extend beyond the expression of genes related to the uptake and metabolism of dicarboxylic acids. Furthermore, V. vulnificus DctD has been shown to exhibit its in-vivo transcriptional activity even in the absence of DctB ligands such as dicarboxylic acids. The dephosphorylated form of V. vulnificus DctD (d-DctD) transitions into the transcriptionally active state under conditions in which the cellular levels of the dephosphorylated form of the glucose-specific enzyme IIA (d-IIAGlc) are sufficient to interact with d-DctD (7). In this novel regulatory pathway, the phosphorelay-independent activation of DctD occurs through the direct interaction of d-DctD with d-IIAGlc, which forms a transcriptionally active complex of [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD].

Based upon numerous reports regarding the transcriptionally active forms of Group I bEBPs (8), it has been speculated that the complex of [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD] forms multimeric state(s) to bind to the UAS and activate the transcription of EPS-II and EPS-III clusters. Therefore, in the present study, we examined the molecular characteristics of the complex consisting of d-DctD and d-IIAGlc. Among the multimeric states of the [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD] complex, a multimer exhibiting both DNA-binding affinity and ATPase activity was identified. Next, the DNA regions comprising the UAS specifically required for multimeric [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD] were localized, and the consensus binding sequences for multimeric [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD] were proposed.

RESULTS

A phosphorylation-deficient DctD (DctDD57Q) forms a transcriptionally inactive dimer ([DctDD57Q]2)

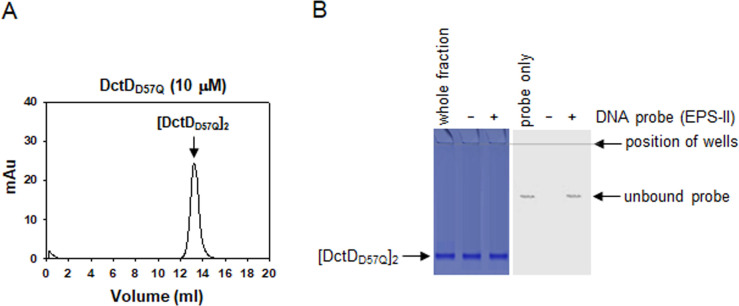

NtrC, one of the representative members of response regulators belonging to Group I of bEBPs, forms a dimer when not phosphorylated, and this dimer possesses DNA-binding ability (9). However, the dephosphorylated form of DctD (d-DctD) has been shown to be unable to bind to the UASs of targets such as EPS-II and EPS-III clusters in V. vulnificus (7). Therefore, we examined the oligomeric state of d-DctD using a phosphorylation-deficient mutant DctDD57Q. On gel permeation chromatography (GPC), recombinant DctDD57Q protein produced a major peak at 13.4 mL in its elution profile (Fig. 1A). When this peak volume was extrapolated to a regression equation derived from standard protein markers (Fig. S1) (10), it was converted to a molecular weight (MW) of 117.1 kDa, which approximated the calculated size of the dimeric DctDD57Q (107.1 kDa). To verify that this dimer did not have DNA-binding ability, as previously shown using the whole fraction of DctDD57Q (7), the fractionated dimeric DctDD57Q ([DctDD57Q]2) was added to a DNA fragment covering −418 to +62 relative to the RpoN-dependent transcription initiation site (TIS, 6) of the EPS-II cluster. The reaction mixtures were run on two identical gels: one was used to localize the proteins by staining with Coomassie Blue, and the other was used to localize the labeled probes via autoradiography (Fig. 1B). Retarded bands of dimeric DctDD57Q and the DNA probe were not observed on either gel, indicating that [DctDD57Q]2 had no DNA-binding ability.

Fig 1.

Characterization of the multimeric conformation of DctDD57Q (A) Chromatographic profile of DctDD57Q. Recombinant protein of DctDD57Q (7), whose calculated molecular weight is 53.53 kDa, was subjected to GPC as described in the Materials and Methods section. The resultant profile showing a single peak at 13.4 mL was presented with the absorbance at 280 nm (mAu). Its size was determined using a regression equation of the standard proteins, as shown in Fig. S1. The fractions (13 and 14 mL) containing this peak were collected and used for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) in Fig. 1B. (B) DNA-binding characteristic of the dimeric DctDD57Q. Approximately 130 nM of the labeled probe from −418 to +62 relative to the transcription initiation site 1 of the EPS-II cluster (6) was incubated with 250 nM dimeric DctDD57Q. Reaction mixtures were run on two identical 8% native polyacrylamide gels; one was stained with Coomassie Blue to localize the proteins (left panel), and the other was observed under a phosphoimager to localize the DNA probes (right panel). The first lanes in each gel were run with the whole fraction of DctDD57Q preparation (left panel) and the labeled probe only (right panel). The second and third lanes in each gel were run with the mixtures containing [DctDD57Q]2 in the absence (−) and presence (+) of DNA probe, respectively.

DctDD57Q complexed with d-IIAGlc (d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex) forms a dimer ([d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]2) or a dodecamer ([d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12)

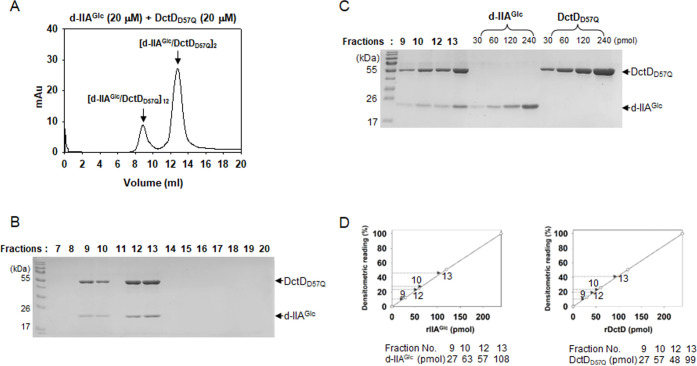

Although DctDD57Q is present in a transcriptionally inactive state, it acquires DNA-binding ability in the presence of dephosphorylated IIAGlc (d-IIAGlc), forming a transcriptionally active complex (7). In this study, we analyzed the molecular characteristics of the interaction between the two proteins, such as the multimeric state(s) of the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex and the molar ratio(s) of each protein in the complex. A mixture containing the same concentration (20 µM) of the two recombinant proteins, DctDD57Q and d-IIAGlc, was analyzed by GPC. Resultant elution profile showed two distinct peaks at 8.9 and 12.8 mL (Fig. 2A), which were converted to molecular weights of 905.5 and 151.0 kDa, respectively, by extrapolating each peak volume to a regression equation shown in Fig. S1. These converted values approximated the calculated sizes of the dodecamer (902.6 kDa) and dimer (150.4 kDa) of the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex. To verify the two multimers’ MWs determined via GPC analysis, the same mixture was analyzed by an independent method: a gradient gel electrophoresis alongside the two standards, one covering from 180 to 1,800 kDa and the other covering from 66 to 1,048 kDa (Fig. S2). The mixture was resolved into two bands: a higher MW band at 900 kDa and a lower MW band between 180 and 146 kDa. This observation strongly supported the GPC-mediated estimation of the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complexes. Subsequent analysis of each fraction collected every 1 mL revealed that the protein bands corresponding to the recombinant proteins of DctDD57Q and IIAGlc appeared only in the lanes of a gel run by the fractions covering the two peaks: fractions 9–10 for a dodecamer and fractions 12–13 for a dimer (Fig. 2B). To further examine the compositional characteristics of each complex, fractions 9, 10, 12, and 13 were separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 2C). Using densitometric readings of known amounts of each recombinant protein, ranging from 30 to 240 pmol, which were run in the same gel, the standard curves for DctDD57Q (right panel) and IIAGlc (left panel) were plotted (Fig. 2D). The amounts of DctDD57Q and IIAGlc in the four fractions were estimated, indicating that almost the same ratio of the two proteins was present in each fraction. Fractions 9, 10, 12, and 13 contained 27, 63, 57, and 108 pmol of IIAGlc and 27, 57, 48, and 99 pmol of DctDD57Q, respectively.

Fig 2.

Characterization of the multimeric conformation of the complex composed of dephospho-IIAGlc and DctDD57Q (d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex). (A and B) Chromatographic and electrophoretic analyses of d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex. A mixture of the same concentrations of two recombinant proteins (20 µM each), d-IIAGlc and DctDD57Q (7), was subjected to GPC (A), as described in Fig. 1A. Each fraction for the peaks at 8.9 and 12.8 mL was run in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (B). (C and D) Compositional analysis of the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex in the two peaks. The fractions for the peaks at 8.9 mL (fractions 9 and 10) and 12.8 mL (fractions 12 and 13) were separated in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (C). For quantitative analysis, the known amounts (30–240 pmol) of each recombinant protein were included in the same gel. Densitometric readings of each band were plotted against the protein amounts to produce the standard curves (D, open circles). Using the standard curves for d-IIAGlc (left graph) and DctDD57Q (right graph), the amounts of each protein in the four fractions were extrapolated and the resultant values were provided below the graphs.

To confirm the 1:1 molar ratio of the two proteins in either the dimeric or dodecameric form of the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex, mixtures containing different ratios of the two proteins were prepared as follows: 5 µM d-IIAGlc + 20 µM DctDD57Q and 20 µM d-IIAGlc +5 µM DctDD57Q. Two mixtures were subjected to GPC and subsequent SDS-PAGE, as shown in Fig. 2. The mixture containing more DctDD57Q than d-IIAGlc (5 µM d-IIAGlc + 20 µM DctDD57Q) produced an extra peak at 13.4 mL in the GPC profile in addition to two peaks (8.9 and 12.8 mL) whose heights and areas decreased by 2- to 5-fold compared to those shown in Fig. 2A (Fig. 3A). Fractions 14 and 15, which covered the extra peak at 13.4 mL peak, were revealed to contain only DctDD57Q (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the peak at 13.4 mL contained the dimeric DctDD57Q that was not involved in forming the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex. In contrast, the mixture containing more d-IIAGlc than DctDD57Q (20 µM d-IIAGlc + 5 µM DctDD57Q) produced two peaks at 8.9 and 12.8 mL, and their heights and areas were almost the same as those in Fig. 3A (Fig. 3C). However, an SDS-polyacrylamide gel run with each elution showed the presence of a protein band with a MW of IIAGlc in fractions 18 and 19 (Fig. 3D). To prove this band was d-IIAGlc that was not involved in forming the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex, recombinant d-IIAGlc (20 µM) was passed through GPC and the collected fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. Although d-IIAGlc could not be detected using GPC equipped with an UV detector (Fig. 3E), its presence was evident in the 18th and 19th fractions (Fig. 3F).

Fig 3.

Verification of the 1:1 binding ratio of IIAGlc and DctD in the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complexes. Mixtures containing 5 µM d-IIAGlc and 20 µM DctDD57Q (A and B) or 20 µM d-IIAGlc and 5 µM DctDD57Q (C and D) were analyzed as described in Fig. 2A and B. Both chromatographic and electrophoretic profiles showed the presence of both proteins in the fractions 9, 10, 12, and 13 mL, as shown in Fig. 2. An extra peak corresponding to dimeric DctDD57Q (A) was formed in a mixture of 5 µM d-IIAGlc and 20 µM DctDD57Q, which was evidenced in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (B, the fractions 14 and 15 mL were marked with a dashed box). SDS-PAGE analysis of a mixture of 20 µM d-IIAGlc and 5 µM DctDD57Q showed that the fractions 18 and 19 mL contained a protein with the MW of IIAGlc (D, marked with a dashed box). Its identity was verified by profiling d-IIAGlc (20 µM) using chromatographic and electrophoretic analyses (E and F).

[d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 has an ability to bind to DNA and hydrolyze ATP

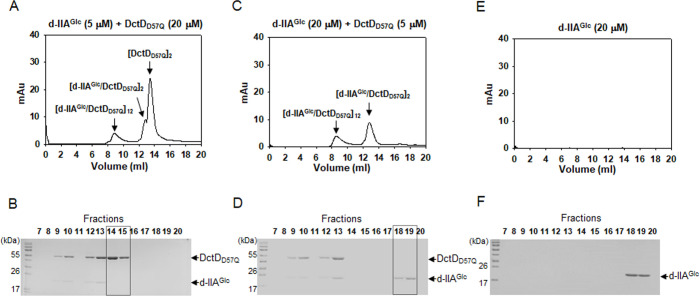

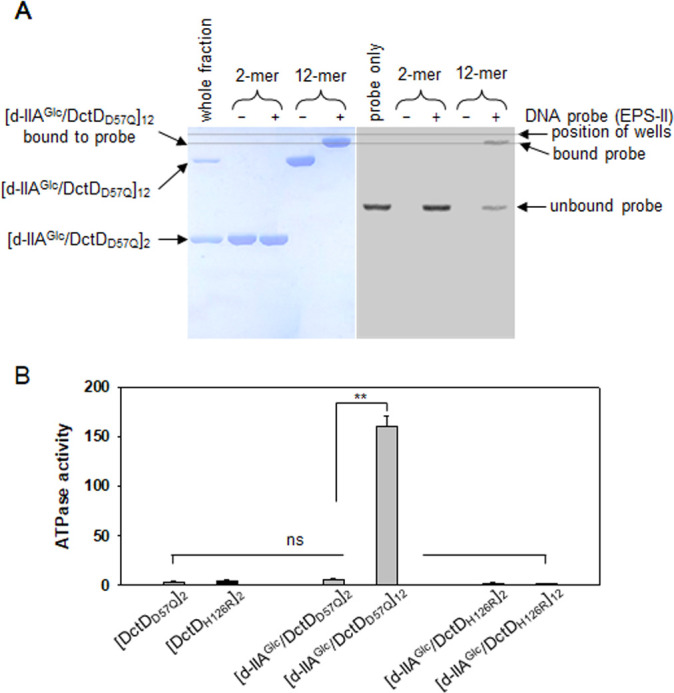

The two multimeric forms, a dimer ([d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]2) and a dodecamer ([d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12), of the complex are composed of d-IIAGlc and DctDD57Q in a 1:1 molar ratio. To identify the multimeric form(s) of the complex capable of binding to DNA, the labeled probe shown in Fig. 1 was mixed with [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]2 or [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12. The mixtures were run on two identical gels, and each gel was stained with Coomassie Blue or exposed to a phosphoimager (Fig. 4A). The mixture containing [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]2 did not show any shifted band on either gel, indicating that the dimeric form of the complex had no DNA-binding ability. In contrast, a mixture containing [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 produced retarded bands of protein and DNA, corresponding to a protein band for the probe-bound [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 (left panel, Fig. 4A) and a DNA band for the [IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12-bound probe (right panel, Fig. 4A). This suggests that [IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, which exhibits DNA-binding affinity, may be a transcriptionally active form of d-DctD.

Fig 4.

Identification of the transcriptionally active form of d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex. (A) DNA-binding ability of the multimeric forms of the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex. Approximately 100 nM of a labeled DNA probe used in Fig. 1B was incubated with 2-mer ([d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]2) and 12-mer ([d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12) of the complex (500 nM [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]1-equivalents). Reaction mixtures were run on two identical 8% native polyacrylamide gels: one was for localizing the proteins (left panel) and the other was for localizing the DNA probes (right panel). For comparison of the bands corresponding to the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex bound to DNA (left panel) with the probe bound by d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex (right panel), a dashed line was drawn parallel to the line positioning the loading wells. The first lanes in each gel were run with the whole fraction of the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex (left panel) and the labeled probe only (right panel). (B) ATPase activity of the multimeric forms of the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex. Both [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]2 and [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 were fractionated and aliquots containing 2 µM complexes ([d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]1-equivalents) were subjected to the ATPase activity assay (11). One micromolar dimeric DctDD57Q ([DctDD57Q]2) was included in the assay. As a negative control, an ATPase-deficient mutant DctD, DctDH216R, was purified as a dephosphorylated state, and then its multimeric forms ([DctDH216R]2, [d-IIAGlc/DctDH216R]2, and [d-IIAGlc/DctDH216R]12) were added to the ATPase reaction mixture (black bars). The activity was presented as μM phosphate produced by μg of proteins per minute. P-values were indicated (**P < 0.001; ns, not significant).

It has been reported that transcriptionally active forms of the Group I bEBP have the enzymatic activity to hydrolyze ATP molecules (12). Assays of ATPase activity using [DctDD57Q]2, [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]2, and [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 revealed that only the dodecameric form of the complex exhibited ATPase activity (gray bars, Fig. 4B). To exclude the possibility that the fractions containing [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 might have been coeluted with some ATPases, an ATP hydrolysis-deficient DctD (13), DctDH216R, was prepared as a dephosphorylated form (d-DctDH216R) and used for GPC analysis. The fractions containing a dodecamer of the complex composed of d-IIAGlc and d-DctDH216R ([d-IIAGlc/d-DctDH216R]12) showed insignificant ATPase activity, as [d-DctDH216R]2 and [d-IIAGlc/d-DctDH216R]2 did (black bars, Fig. 4B). It suggests that the apparent ATP hydrolysis by the fractions of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 was not derived from trace contamination of ATPase activity during GPC fractionation used in this study. Therefore, [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, which has both DNA-binding affinity and ATPase activity, is a transcriptionally active form of d-DctD.

[d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 specifically binds to the sequences homologous to a Rhizobium DctD-binding site

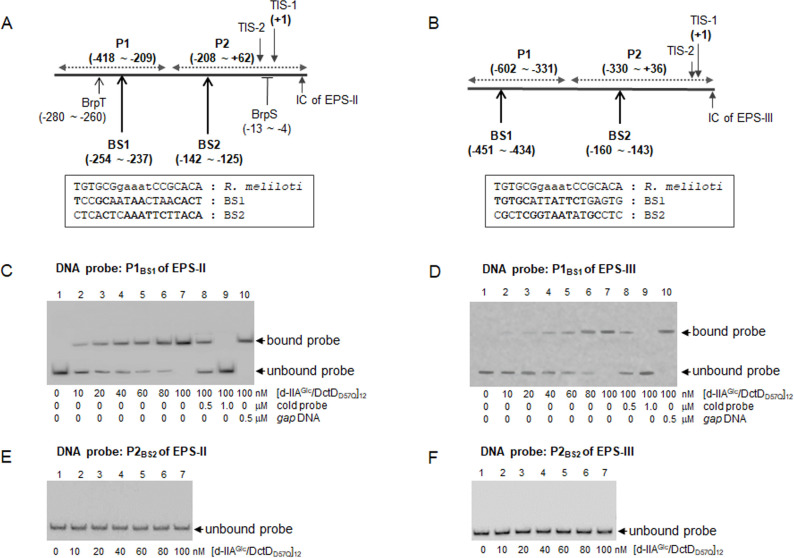

It has been commonly observed that many members of the Group I bEBP bind to multiple sites in the upstream region of a target gene to activate its transcription (3). Two sites were localized in the upstream region of dctA of Rhizobium species (14). Additionally, the DctD-binding sequences, 5′-TGTGCGgaaatCCGCACA-3′, have been identified in Rhizobium meliloti (15). Using these sequences, the putative UASs of the EPS-II and EPS-III clusters in V. vulnificus, which are homologous to the R. meliloti DctD-binding sequences, were searched in their upstream regions. Two sites with homology to the consensus sequences were discernible, which were designated as BS1 remote from TIS-1 (−254 to −237 in EPS-II and −451 to −434 in EPS-III) and BS2 close to TIS-1 (−142 to −125 in EPS-II and −160 to −143 in EPS-III) (Fig. 5A and B). To determine whether [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 could bind to these putative BSs, DNA probes containing a single BS of each gene cluster (P1BS1 for the probe including BS1 and P2BS2 for the probe including BS2) were prepared for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Only the probes containing BS1s were bound by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 and produced a shifted band in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5C and D). Furthermore, the shifted bands were decreased by the addition of the cold probes but persisted by the addition of the noncompetitive gap DNA, indicating the specific binding of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 to the BS1-probes. In contrast, the probes containing BS2s did not produce any retarded band, even in the presence of the highest concentration of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 used in this study (up to 100 nM; Fig. 5E and F). These results indicate that [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 efficiently binds to P1s containing the nucleotide sequences in BS1s.

Fig 5.

Localization of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12-binding sites in the upstream regions of EPS-II and EPS-III clusters. (A and B) Two putative DctD-binding sites in the EPS-II and EPS-III clusters. Two sites (designated as BS1 for the remote site and BS2 for the close site from TIS-1) showing moderate identity to the DctD-binding sequences previously found in R. meliloti (5′-TGTGCGgaaatCCGCACA-3′; 15) were localized in the upstream regions of two gene clusters: the nucleotides positioned at −254 to −237 (BS1) and −142 to −125 (BS2) relative to RpoN-dependent TIS-1 of EPS-II (A) and the nucleotides positioned at −451 to −434 (BS1) and −160 to −143 (BS2) relative to the TIS-1 of EPS-III (B). Homologous nucleotides in each site were marked by boldfaces. In case of the EPS-II cluster (or brp operon), the regulatory sites interacting with the other transcription factors, such as BrpS and BrpT, were marked (16, 17). (C–F) Binding of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 to the probes containing either BS1 or BS2. DNA probes containing BS1 of EPS-II (C) or EPS-III (D), which were designated as P1BS1 (a 210 bp DNA fragment from −418 to −209 of EPS-II and a 272 bp DNA fragment from −602 to −331 of EPS-III), were prepared for EMSA. Similarly, the probes containing BS2 of EPS-II (E) or EPS-III (F) were prepared, which were designated as P2BS2 (a 270 bp DNA fragment from −208 to +62 of EPS-II and a 366 bp DNA fragment from −330 to +36 of EPS-III). Each probe was labeled and 100 nM was incubated with various concentrations of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 up to 100 nM. To verify the specific binding to P1BS1 (C and D), the identical but unlabeled DNA fragments (cold probes) and the noncompetitive gap DNA were included. The resultant reaction mixtures were subjected to 8% native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and DNA bands corresponding to the unbound or bound probes were indicated by arrows. Lanes 1, probe only; lanes 2, probe with 10 nM of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12; lanes 3, probe with 20 nM of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12; lanes 4, probe with 40 nM of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12; lanes 5, probe with 60 nM of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12; lanes 6, probe with 80 nM of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12; lanes 7, probe with 100 nM of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12; lanes 8, probe with 100 nM of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 and 0.5 µM of cold probe; lanes 9, probe with 100 nM of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 and 1.0 µM of cold probe; and lanes 10, probe with 100 nM of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 and 0.5 µM of gap DNA.

Interaction of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 to DNAs containing the specific binding sites is required for successful transcription of the target gene clusters

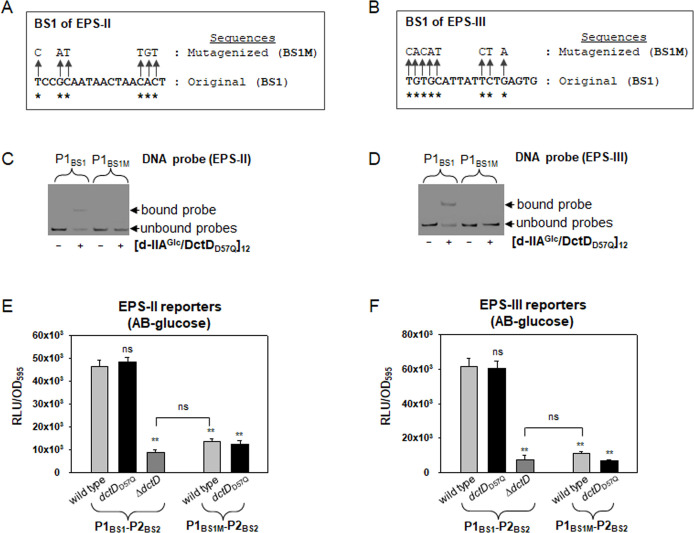

Next, to confirm whether the putative BS1s were directly and specifically recognized and bound by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, P1 probes containing the mutagenized BS1s were prepared by substituting the conserved nucleotides (BS1Ms; Fig. 6A and B). An EMSA using P1 probes containing mutagenized BS (P1BS1M) in the presence of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 did not show any retarded band (Fig. 6C and D). These results indicated that the specific binding of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 to P1 was achieved through its interaction with the regions containing the BS1s of the two gene clusters.

Fig 6.

Effect of the mutations in the BS1s on binding by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 and transcription of the EPS clusters. (A and B) Mutagenesis of the BS1s of EPS-II and EPS-III clusters. The nucleotides in BS1s of EPS-II (A) and EPS-III (B), which are conserved in the R. meliloti DctD-binding consensus sequences (5′-TGTGCGgnnntCCGCACA-3′; 15), were marked with asterisks. These conserved nucleotides were substituted with other nucleotides, as indicated by arrows, to produce BS1M. (C and D) DNA-binding affinity of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 to the probes containing BS1M. DNA fragments of P1 containing BS1 (P1BS1) or BS1M (P1BS1M) were prepared from the EPS-II (C) and EPS-III (D) clusters. Then, EMSA was performed as described in Fig. 5. Labeled DNA bands corresponding to the unbound or bound probes, which were resolved in 6% native polyacrylamide gel, were indicated by arrows. (E and F) Expression of the BS1M-containing transcription reporters of EPS-II and EPS-III clusters. The luxAB-based transcription reporters fused with the original upstream regulatory regions (P1BS1-P2BS2; 18) or the mutagenized upstream regions (P1BS1M-P2BS2) of EPS-II (E) and EPS-III (F) were transferred to the wild type and dctDD57Q (7). Then, V. vulnificus cells were grown in AB-glucose supplemented with tetracycline (3 µg/mL). At an OD595nm of 0.4, aliquots of bacterial cells were harvested, and their luciferase activities were measured, as described in the Materials and Methods section. The expression of each reporter was presented as normalized values: the relative light unit (RLU) divided by the cell mass (OD595nm) of each sample. As a negative control, ΔdctD strain carrying the original reporter was included in each assay. P-values for comparison with the P1BS1-P2BS2 reporter in the wild type or ΔdctD were indicated (**P < 0.001; ns, not significant).

To determine whether BS1 is the actual cis-element determining the in-vivo transcriptional activation by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, luxAB-based transcription reporters fused with the original DNA fragments of the gene clusters (P1BS1-P2BS2; 18)or DNA fragments containing mutated BS1s (P1BS1M-P2BS2) were prepared. Their expression was monitored in wild-type and dctDD57Q V. vulnificus grown in AB-glucose medium, in which IIAGlc and DctD were present in dephosphorylated forms, as previously shown by Kang and Lee (7) (Fig. 6E and F). Compared to the original reporters of EPS-II and EPS-III clusters, the expression of P1BS1M-P2BS2-reporters was significantly impaired, which was almost at the same levels as those in ΔdctD V. vulnificus. These results indicate the critical role of BS1 in transcriptional activation by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12.

Specific nucleotides in the downstream regions of BS1s (BS1[dn]) are additionally required for successful binding of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12

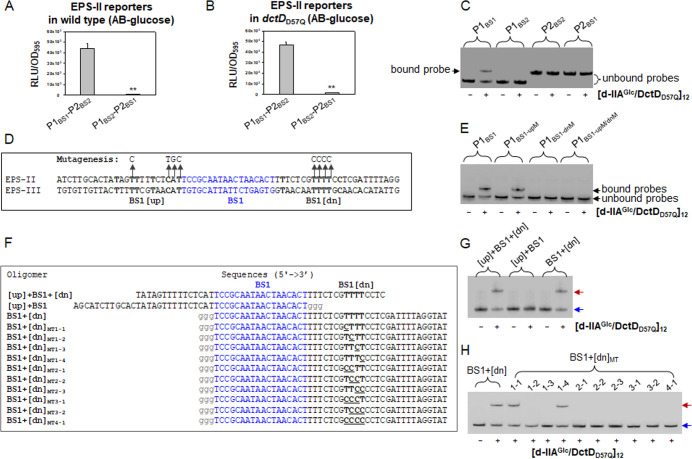

Binding sequences for R. meliloti DctD, which comprise 18 nucleotides, have been derived from footprint assays using the truncated DctD mimicking phosphorylated DctD (p-DctD) (19). Considering the molecular size of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, it was plausible to speculate that this complex might interact with an extended region in the target DNA. Therefore, we further tested whether the DNA regions flanking BS1s were required for successful transcriptional activation by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12. For this purpose, another luxAB-based transcription reporter of the EPS-II cluster was prepared using DNA fragment, in which the locations of BS1 and BS2 were switched to produce P1BS2-P2BS1. Then, its expression was monitored in wild-type (Fig. 7A) and dctDD57Q (Fig. 7B) V. vulnificus grown in AB-glucose medium. Although a reporter having P1BS2-P2BS1 contained the intact BS1 sequences, its expression was not induced in both strains of V. vulnificus, compared to the original reporter having P1BS1-P2BS2.

Fig 7.

Characterization of the flanking region of BS1 for binding by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 and successful expression of EPS-II cluster. (A and B) Expression of the BS-switched transcription reporter of EPS-II. A mutagenized reporter was constructed by switching the positions of the original BS1 and BS2 of the EPS-II cluster, to produce P1BS2-P2BS1. Its expression in wild type (A) and dctDD57Q (B) was compared to that of the original reporter (P1BS1-P2BS2). At an OD595nm of 0.4 in AB-glucose supplemented with tetracycline (3 µg/mL), the expression of each reporter was estimated and presented with normalized values, RLU per OD595nm, as described in Fig. 6. P-values for comparison with the original reporter were indicated (**P < 0.001). (C) DNA-binding affinity of [d-IIAGlc DctDD57Q]12 to BS-switched probes. Various DNA fragments of the EPS-II cluster, including the original P1 (P1BS1), switched P1 (P1BS2), the original P2 (P2BS2), and switched P2 (P2BS1), were prepared for EMSA using [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12. Each probe (100 nM) was mixed with 40 nM [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12. DNA bands corresponding to the unbound probes and the probe bound by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 were indicated by brackets and arrow, respectively. (D) Mutagenesis of BS1-flanking regions. The nucleotide sequences flanking the BS1s are conserved in the EPS-II and EPS-III clusters (marked with boldfaces). Nucleotides upstream of the EPS-II BS1 (BS1[up]) and downstream of the EPS-II BS1 (BS1[dn]) were mutagenized as indicated by arrows and substituted nucleotides, to produce BS1-dnM and BS1-upM, respectively. (E) DNA-binding affinity of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 to the probes containing BS1-dnM and BS1-upM. DNA fragments of the EPS-II cluster, including the original P1 (P1BS1), upstream-mutagenized P1 (P1BS1-upM), downstream-mutagenized P1 (P1BS1-dnM), and P1 mutagenized both upstream and downstream (P1BS1-upM/dnM), were prepared for EMSA using [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12. Each probe (100 nM) was mixed with 40 nM [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, and resultant reaction mixtures were run on a native gel, as described above. (F) Preparation of various oligomers containing BS1. Nucleotide oligomers containing BS1 with both flanking regions ([up] + BS1 + [dn]), BS1 with upstream sequences only ([up] + BS1), and BS1 with downstream sequences only (BS1 + [dn]) were prepared. Series of BS1 + [dn] derivatives, BS1 + [dn]MT, whose Ts in BS1[dn] were mutagenized in a combinatorial way, were prepared. Eighteen nucleotides corresponding to the BS1 of the EPS-II cluster were blue-colored, and the extra three Gs linked to the 3’-end of [up] + BS1 and the 5’-end of BS1 + [dn] oligomers were gray-colored. Four nucleotides in BS1 + [dn] and its derivatives were bold-faced. (G, H) DNA-binding affinity of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 to various oligomers. Each oligomer (100 nM) was labeled and used for EMSA. Oligomers of [up] + BS1 + [dn], [up] + BS1, and BS1 + [dn] were mixed to reaction buffers without (−) and with (+) 40 nM [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 (G). Ten mutant oligomers covering from BS1+[dn]MT1-1 to BS1+[dn]MT4-1 were mixed with [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, and resultant reaction mixtures were subjected to 8% native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (lanes 3–12, H). As controls, BS1 + [dn] only (lane 1) and BS1 + [dn] with [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 (lane 2) were included in the same gel. Oligomer bands corresponding to the unbound and bound probes were indicated by blue and red arrows, respectively.

To elucidate the reason for the lack of induction of the P1BS2-P2BS1 expression, two probes with switched BSs, P1BS2 and P2BS1, were prepared for EMSA in the presence of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12. No binding of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 to P1BS2 or P2BS1 was observed (Fig. 7C). This suggests that in addition to the 18 nucleotide-long BS1, the extra nucleotide sequences in P1 were required for binding by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 and the successful activation of EPS-II cluster transcription.

Alignment of the nucleotide sequences flanking the BS1s of EPS-II and EPS-III revealed the presence of conserved nucleotides in the upstream (BS1[up]) and downstream (BS1[dn]) regions (Fig. 7D). To test whether these selected sequences could affect the binding of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, conserved nucleotides in each flanking region were mutagenized to produce P1 with mutagenized upstream (P1BS1-upM), mutagenized downstream (P1BS1-dnM), or mutagenized upstream and downstream (P1BS1-upM/dnM) (Fig. 7D). When each probe was treated with [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, the probes mutagenized in the stretch of the four Ts located downstream of BS1 failed to be bound by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 (Fig. 7E), suggesting a critical role for BS1 and BS1[dn] in the interaction between P1 and [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12.

To verify that the sequences in BS1 and BS1[dn] containing multiple Ts were sufficient for [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 to successfully bind to P1, three kinds of 27 nucleotide-long oligomers were prepared: [up] + BS1 + [dn], [up] + BS1, and BS1 + [dn] (Fig. 7F). An EMSA using these probes with [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 revealed that oligonucleotides containing both BS1 and BS1[dn] were efficiently bound by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 (Fig. 7G). These results demonstrate that BS1, together with the downstream array of Ts, is required for binding by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12.

Alignments of BS1s of various DctD-regulons and localization of BS1[dn] for binding of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12

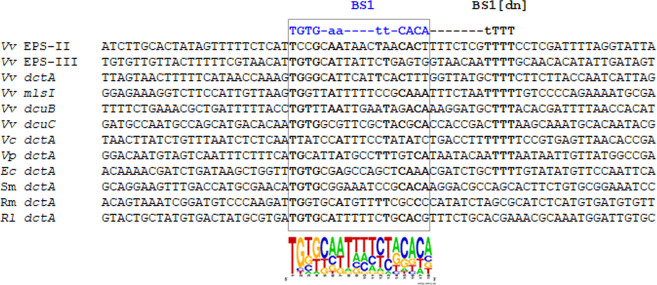

To draw the consensus-binding sequences for [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, putative BS1 and BS1[dn] were localized in the upstream regions of the known DctD-regulons (i.e., dctA genes of various bacterial species) and the tentative DctD-regulons of V. vulnificus (e.g., mlsI, dcuB, and dcuC genes). Alignment of these sequences with those of the EPS-II and EPS-III clusters revealed that 18 nucleotide-long BS1s are relatively well conserved as the following inverted repeat sequences: 5′-TGTG-aa----tt-CACA-3′ (Fig. 8). In addition, the arrays of multiple Ts apparently locate at the 7th or 8th nucleotide after the 3′-end of BS1s of the above genes encoded by three Vibrio species and Escherichia coli (6, 20, 21). In contrast, T-rich BS1[dn] was not discernible in the upstream regions of dctA genes of Sinorhizobium meliloti (14), R. meliloti (15), and Rhizobium leguminosarum (14): it is noteworthy that genes encoding the components of the typical glucose-PTS system are not present in Rhizobium and related species (22), suggesting the absence of [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD] complex in these bacteria.

Fig 8.

Proposed [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12-binding sequences in the DctD-regulons. The BS1 and BS1[dn] sequences of the EPS-II and EPS-III clusters were aligned with the putative BS1 and BS1[dn] in the upstream regions of dctA genes of V. vulnificus (Vv; 6), Vibrio cholerae (Vc; 21), Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Vp; VPY51_04360), E. coli (Ec; 20), S. meliloti (Sm; 14), R. meliloti (Rm; 15), and R. leguminosarum (Rl; 14). In addition, the upstream regions of the putative DctD-regulons, whose expression was assumed to be related to the metabolisms of dicarboxylic acids in V. vulnificus, were included in this analysis: malate synthase (mlsI, VVMO6_03414) and two C4-dicarboxylate transporters (dcuB, VVMO6_03835; dcuC, VVMO6_03887). Conserved regions among 12 BSs were marked by a dashed box and a nucleotide-frequency plot, and the highly conserved nucleotides among 12 BSs and 9 BS[dn]s were indicated with bold-faced letters.

The proposed BS1[dn]s contained three to five Ts, which led us to investigate the required number of Ts for binding by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12. For this purpose, several oligonucleotides derived from the BS1 +[dn] of EPS-II cluster, whose Ts were sequentially mutated to produce a series of BS1 + [dn]MT as described in Fig. 7F. EMSA using these probes, from BS1 + [dn]MT1-1 to BS1 + [dn]MT4-1, showed that the mutant probes containing at least three consecutive Ts, such as BS1 + [dn]MT1-1 and BS1 + [dn]MT1-4, were able to be bound by [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 (Fig. 7H). Therefore, 18 nucleotide-long BS1 and 3 consecutive Ts in BS1[dn] are essential for binding by [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD]12.

DISCUSSION

DctD is a well-known transcription factor belonging to Group I of bEBP, whose regulatory competence in activating RpoN-initiated transcription (23) is achieved after it is phosphorylated by its cognate sensor kinase, DctB. Interestingly, the transcriptionally inactive state of dephosphorylated DctD (d-DctD) is converted to its transcriptionally active form when it produces a complex with d-IIAGlc (7). To date, transcriptional activation by dephosphorylated forms of other Group I bEBPs has not been reported. Our results suggest that d-DctD or the d-IIAGlc/d-DctD complex may have unique features that have not been observed in the well-studied members of Group I bEBPs. Therefore, to understand this phosphorylation-independent regulatory mechanism, the molecular characteristics of both d-DctD and the d-IIAGlc/d-DctD complex were investigated in this study using the DctDD57Q and the DctD-regulons identified in V. vulnificus (6).

DctDD57Q, a form of recombinant DctD that mimics dephosphorylated DctD (7), exists in a dimeric conformation (Fig. 1). Although dimeric forms of dephosphorylated Group I bEBPs, such as NtrC and ZraR, were at least able to bind to specific DNA sequences (9, 24), dimeric d-DctD ([DctDD57Q]2) did not show any DNA-binding activity (Fig. 1C). Thus, while a dimeric form of truncated DctD has been shown to have DNA-binding affinity (13, 25), it is noteworthy that this recombinant protein was deleted in its regulatory domain and considered to be a constitutively active form.

DctDD57Q specifically interacted with the recombinant protein of d-IIAGlc, which has been purified from cells grown under glucose-enriched conditions (7, 26), and formed a complex in a 1:1 molar ratio (Fig. 2D, 3B and D). This complex was present in either dimeric ([d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]2) or dodecameric ([d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12) conformations (Fig. 2A), among which [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 showed the ability to bind to target DNA and hydrolyze ATP molecules (Fig. 4).

It is generally considered that the oligomerization process of bEBPs is initiated by the dimerization of two monomers and followed by the formation of a hexamer via direct interaction among three dimers (3). However, a process deviated from the above stepwise oligomerization has been observed in PspF belonging to the Group IV bEBP, which lacks the regulatory domain and requires other proteins to control its ATPase activity and DNA-binding affinity (27). When DctDD57Q was mixed with d-IIAGlc, a hexameric form of the complex was not detected. Thus, it is speculated that [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]2 undergoes hexamerization to produce [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12, in which their ATPase domains can be positioned to attain the ATP hydrolyzing activity. The amino acid residues of DctD and IIAGlc that are involved in the interaction between the two proteins have not yet been identified, and the structural characterization of this complex waits future study. Nonetheless, it has been postulated that d-IIAGlc would interact with the regulatory domain of DctD to mimic the transcriptionally active p-DctD since structural modification of the phosphorylated regulatory domains is critically important for eliciting the ATPase activity of Group I bEBPs (12). Therefore, it is plausible that the arrangement of a dodecamer composed of 12 d-DctDs, to which regulatory domains are adhered by d-IIAGlc, should be different from the arrangements of a higher-order multimer of p-DctD.

The previous studies with the Rhizobium DctD showed that DctD-binding nucleotide sequences were 5′-TGTGCGgnnntCCGCACA-3′ and the multiple (i.e., at least two) binding sites were localized in the regions upstream dctA genes (14, 19, 28). . These findings led us to putatively localize multiple DctD-binding sites, which were homologous to the above sequences, in the upstream regions of the DctD-regulon, such as the EPS-II and EPS-III clusters. Among the two candidate binding sites, BS1 and BS2 (Fig. 5A and B), BS1s locating relatively far from the RpoN-initiated TISs were specifically bound by [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD]12 (Fig. 5C through F). Alignment of the putative BS1s in the upstream regions of various DctD-regulons showed the presence of relatively well-conserved inverted repeat sequences of 5′-TGTG-aa----tt-CACA-3′ (Fig. 8).

Structural studies using recombinant NtrC, a representative member of the Group I bEBP, suggest that each monomer in a dimer is directly involved in specifically binding the target DNA sequences consisting of 17 nucleotides (29). Therefore, the binding regions for [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 may be wider than those determined using a truncated DctD dimer (14, 19, 28). To test this hypothesis, regions flanking BS1 were examined for their involvement in specific interactions with [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12. EMSA using various DNA probes, as shown in Fig. 7D and F, clearly demonstrated that both BS1 and its downstream region (BS1[dn]), containing at least three consecutive Ts, were essential for the in vitro binding of [d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q]12 (Fig. 7E, G and H) and the in vivo transcriptional activation (Fig. 7A and B).

Cellular levels of the dephosphorylated forms of glucose-PTS components are highly increased in bacteria growing in the presence of glucose (30). Thus, cellular levels of [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD]12 and its transcriptional activity are mainly determined by glucose in the ambient environments. However, complex formation between d-DctD and d-IIAGlc is further regulated by other carbon sources, such as glycerol (7). Glycerol kinase, GlpK, has high affinity to d-IIAGlc (31, 32); thus, its presence results in decreased levels of cellular [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD]12 due to competition between GlpK and d-DctD for binding d-IIAGlc. Since d-IIAGlc is a versatile protein capable of interacting with the other kinases of non-PTS sugars, including maltose, arabinose, melibiose, and raffinose (33), [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD]12-mediated regulatory pathways should be under the multilayered control of diverse carbon sources. Furthermore, complex formation with IIAGlc may play an additional role in controlling d-DctD protein stability in vivo. In this case, the formation of [d-IIAGlc/d-DctD]12 could be a way modulating the appropriate cellular levels of total DctD.

Taken together, DctD, a response regulator comprising a two-component regulatory system, can activate transcription via an alternative pathway that is independent of its cognate sensor kinase, but dependent upon a dephosphorylated component of the glucose-PTS, IIAGlc. When the dodecamer of the d-IIAGlc/d-DctD complex is formed, it specifically binds to a single but extended BS and activates transcription of the target genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1. V. vulnificus strains were grown at 30°C in AB medium (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgSO4, 0.2% casamino acids, 10 mM potassium phosphate, 100 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM L-arginine, pH7.5) (34) supplemented with glucose (33.4 mM). E. coli strains used for plasmid DNA preparation and conjugational transfer were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl) (35). Antibiotics were added to AB or LB media at the following concentrations: for V. vulnificus, tetracycline at 3 µg/mL; and for E. coli, ampicillin at 100 µg/mL and tetracycline at 15 µg/mL.

Purification and gel permeation chromatography of recombinant proteins

For the preparation of d-DctD2, pQE30-dctDD57Q (7) was expressed in E. coli JM109 in the presence of 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. To prepare d-IIAGlc, pQE30-crr was expressed in the presence of glucose, as previously described (36). Each recombinant protein was purified using an Ni+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity column (Bio-Rad). Next, 500 µL of the recombinant proteins of DctDD57Q, d-IIAGlc and the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex dissolved in a buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 20 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM NaCl) were applied to the AKTA-FPLC system (Amersham Biosciences) equipped with a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 Gl column (GE Healthcare) (37). Each sample was fractionated using a running buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 20 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2, and 300 mM NaCl) at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The void volume of the column used in this assay was 7.2 mL, which is consistent with the previously reported value (38). The apparent molecular weights of the oligomeric proteins in the collected fractions were determined using an elution profile derived from the standard proteins (Protein Standard Mix 15–600 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich) as described in Fig. S1.

Site-directed mutagenesis

DctD-binding sites (BS1) in the upstream regions of the EPS-II and EPS-III clusters were mutagenized using the overlap extension method (39) with the following sets of primers carrying the desirably substituted nucleotides: BS1M_II-F and BS1M_II-R for BS1 of EPS-II and BS1M_III-F and BS1M_III-R for BS1 of EPS-III (Table S2). To switch the positions of the BSs of EPS-II, the primer sets of EPS_II_BS1toBS2-F and EPS_II_BS1toBS2-R or EPS_II_BS2toBS1-F and EPS_II_BS2toBS1-R were used to produce P1BS2 or P2BS1, respectively. To mutagenize the nucleotide sequences in the upstream and downstream regions of BS1 of EPS-II, the primer sets of EPS_II_upst-F and EPS_II_upst-R or EPS_II_dnst_F and EPS_II_dnst_R were used to produce P1BS1-upM or P1BS1-dnM, respectively. The resultant DNA fragments were cloned into pBlunt-TOPO (MGmed) and the mutagenized nucleotide sequences were verified by DNA sequencing. To construct pQE30-dctDH216R, the internal primers including the altered nucleotides for the 216th arginine of V. vulnificus DctD, H216R-F and H216R-R (13), were utilized as described above (39, Table S2). The resultant mutagenized dctD fragment was digested with BamHI and KpnI and then ligated to pQE30 as previously described (6).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

EMSAs were performed with various kinds of probes containing a single BS or both BSs: DNA probes containing a single BS of EPS-II cluster [P1BS1 with BS1 (209 bp) and P2BS2 with BS2 (271 bp)] or EPS-III cluster [P1BS1 with BS1 (271 bp) and P2BS2 with BS2 (367 bp)]; a DNA probe containing both BSs of EPS-II cluster [P1BS1-P2BS2 (480 bp)]; and DNA probes containing switched BS of EPS-II cluster [P1BS2 (209 bp) and P2BS1 (271 bp)]. To analyze the flanking regions of BS1, oligonucleotides [up] + BS1 + [dn], [up] + BS1, BS1 + [dn], and mutant derivatives of BS1 + [dn] were prepared as described in Fig. 7F. DNA fragments were labeled with [γ-32P] ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (TaKaRa), and the resultant labeled probes were incubated in a reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 20 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM NaCl) with various concentrations of recombinant proteins of DctDD57Q (7) and d-IIAGlc (36). The reaction mixtures were resolved on 6% or 8% native polyacrylamide gels.

Measurement of ATPase activity

The enzymatic activity for ATP hydrolysis was measured by quantifying the phosphate released from ATP using ATPase/GTPase Activity Kit (Sigma-Aldrich). For the assays, FPLC fractions representing the specific multimeric states of DctDD57Q and the d-IIAGlc/DctDD57Q complex were diluted to 10 µmole/l with assay buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.0], 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 5 mM MgCl2) and mixed with 5 mM ATP. After the reaction mixtures (80 µL) were incubated at 37°C for 10 min, the mixtures were added with malachite green reagent (20 µL) and subjected to spectrophotometry at 620 nm (11). As a control, an ATPase-deficient DctD, DctDH216R, was purified from E. coli JM109 carrying pQE30-dctDH216R after treated with alkaline-phosphatase (AP) as described (40). Then, dephosphorylated form of DctDD216R (d-DctDD216R) and d-IIAGlc complex was dissolved in a buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 20 mM KCl, 50 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM NaCl) and applied to the AKTA-FPLC system equipped with a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 Gl column. Fractionated dimeric d-DctDH216R and d-IIAGlc/d-DctDH216R complexes were used for ATPase assay.

Measurement of transcriptional reporter plasmids fused with luxAB genes

The expression of various luxAB-based transcription reporters was monitored in V. vulnificus strains growing in AB-glucose medium, as previously described (6). At the designated time points, the bacterial culture aliquots were mixed with a luciferase substrate, n-decyl aldehyde (0.006%), and then the resultant light production was measured in a luminometer (GloMax 20/20 luminometer, Promega). Specific bioluminescence was presented by normalizing the RLU with respect to cell mass (OD595), as described (41).

Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as means ± standard deviations of data from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test (Systat Program, SigmaPlot version 9; Systat Software, Inc.). P-values are presented by one asterisk (*) or two asterisks (**) when 0.001 < P < 0.01 or P < 0.001, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation, Republic of Korea: NRF-2021R1A2B5B02002477 and NRF-2018R1A5A1025077 (Microbial Survival Systems Research Center).

Contributor Information

Kyu-Ho Lee, Email: kyuholee@sogang.ac.kr.

Paul Babitzke, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00330-24.

Gel permeation chromatography of standard proteins.

PAGE analysis of the mixture of d-IIAGlc and DctDD57Q.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Webster N, Jin JR, Green S, Hollis M, Chambon P. 1988. The yeast UASG is a transcriptional enhancer in human HeLa cells in the presence of the GAL4 Trans-activator. Cell 52:169–178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90505-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wigneshweraraj SR, Burrows PC, Bordes P, Schumacher J, Rappas M, Finn RD, Cannon WV, Zhang X, Buck M. 2005. The second paradigm for activation of transcription. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 79:339–369. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)79007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bush M, Dixon R. 2012. The role of bacterial enhancer binding proteins as specialized activators of Σ54-dependent transcription. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:497–529. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00006-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Engelke T, Jording D, Kapp D, Pühler A. 1989. Identification and sequence analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti dctA gene encoding the C4-dicarboxylate carrier. J Bacteriol 171:5551–5560. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5551-5560.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Golby P, Davies S, Kelly DJ, Guest JR, Andrews SC. 1999. Identification and characterization of a two-component sensor-kinase and response-regulator system (DcuS-DcuR) controlling gene expression in response to C4-dicarboxylates in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 181:1238–1248. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.4.1238-1248.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kang S, Park H, Lee KJ, Lee KH. 2021. Transcription activation of two clusters for exopolysaccharide biosynthesis by phosphorylated DctD in Vibrio vulnificus. Environ Microbiol 23:5364–5377. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kang S, Lee KH. 2022. Transition of dephospho-DctD to the transcriptionally active state via interaction with dephospho-IIAGlc. mBio 13:e0383921. doi: 10.1128/mbio.03839-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rappas M, Bose D, Zhang X. 2007. Bacterial enhancer-binding proteins: unlocking sigma54-dependent gene transcription. Curr Opin Struct Biol 17:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rippe K, Mücke N, Schulz A. 1998. Association states of the transcription activator protein NtrC from E. coli determined by analytical ultracentrifugation. J Mol Biol 278:915–933. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wyman C, Rombel I, North AK, Bustamante C, Kustu S. 1997. Unusual oligomerization required for activity of NtrC, a bacterial enhancer-binding protein. Science 275:1658–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ogura T, Wilkinson AJ. 2001. AAA+ Superfamily ATPases: common structure-diverse function. Genes Cells 6:575–597. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00447.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rappas M, Schumacher J, Beuron F, Niwa H, Bordes P, Wigneshweraraj S, Keetch CA, Robinson CV, Buck M, Zhang X. 2005. Structural insights into the activity of enhancer-binding proteins. Science 307:1972–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1105932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang YK, Lee JH, Brewer JM, Hoover TR. 1997. A conserved region in the sigma54-dependent activator DctD is involved in both binding to RNA polymerase and coupling ATP hydrolysis to activation. Mol Microbiol 26:373–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5851955.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ledebur H, Nixon BT. 1992. Tandem DctD-binding sites of the Rhizobium meliloti dctA upstream activating sequence are essential for optimal function despite a 50- to 100-fold difference in affinity for DctD. Mol Microbiol 6:3479–3492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01783.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scholl D, Nixon BT. 1996. Cooperative binding of DctD to the dctA upstream activation sequence of Rhizobium meliloti is enhanced in a constitutively active truncated mutant. J Biol Chem 271:26435–26442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guo Y, Rowe-Magnus DA. 2011. Overlapping and unique contributions of two conserved polysaccharide Loci in governing distinct survival phenotypes in Vibrio vulnificus. Environ Microbiol 13:2888–2990. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chodur DM, Rowe-Magnus DA. 2018. Complex control of a genomic island governing biofilm and rugose colony development in Vibrio vulnificus. J Bacteriol 200:e00190-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00190-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim HS, Park SJ, Lee KH. 2009. Role of NtrC-regulated exopolysaccharides in the biofilm formation and pathogenic interaction of Vibrio vulnificus. Mol Microbiol 74:436–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06875.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee JH, Scholl D, Nixon BT, Hoover TR. 1994. Constitutive ATP hydrolysis and transcription activation by a stable, truncated form of Rhizobium meliloti DCTD, a sigma 54-dependent transcriptional activator. J Biol Chem 269:20401–20409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davies SJ, Golby P, Omrani D, Broad SA, Harrington VL, Guest JR, Kelly DJ, Andrews SC. 1999. Inactivation and regulation of the aerobic C4-dicarboxylate transport (dctA) gene of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 181:5624–5635. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.18.5624-5635.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng AT, Zamorano-Sánchez D, Teschler JK, Wu D, Yildiz FH. 2018. NtrC adds a new node to the complex regulatory network of biofilm formation and Vps expression in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 200:e00025-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00025-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stowers MD. 1985. Carbon metabolism in Rhizobium species. Annu Rev Microbiol 39:89–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.39.100185.000513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gruber TM, Gross CA. 2003. Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu Rev Microbiol 57:441–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sallai L, Tucker PA. 2005. Crystal structure of the central and C-terminal domain of the sigma(54)-Activator Zrar. J Struct Biol 151:160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gu B, Lee JH, Hoover TR, Scholl D, Nixon BT. 1994. Rhizobium meliloti DctD, a sigma 54-dependent transcriptional activator, may be negatively controlled by a subdomain in the C-terminal end of its two-component receiver module. Mol Microbiol 13:51–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koo BM, Yoon MJ, Lee CR, Nam TW, Choe YJ, Jaffe H, Peterkofsky A, Seok YJ. 2004. A novel fermentation/respiration switch protein regulated by enzyme IIAGlc in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 279:31613–31621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405048200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mehta P, Jovanovic G, Lenn T, Bruckbauer A, Engl C, Ying L, Buck M. 2013. Dynamics and stoichiometry of a regulated enhancer-binding protein in live Escherichia coli cells. Nat Commun 4:1997. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang YK, Hoover TR. 1997. Alterations within the activation domain of the sigma 54-dependent activator DctD that prevent transcriptional activation. J Bacteriol 179:5812–5819. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5812-5819.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimada T, Furuhata S, Ishihama A. 2021. Whole set of Constitutive promoters for RpoN sigma factor and the regulatory role of its enhancer protein NtrC in Escherichia coli K-12. Microb Genom 7:000653. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dörschug M, Frank R, Kalbitzer HR, Hengstenberg W, Deutscher J. 1984. Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent Phosphorylation site in enzyme Iiiglc of the Escherichia coli Phosphotransferase system. Eur J Biochem 144:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Boer M, Broekhuizen CP, Postma PW. 1986. Regulation of glycerol kinase by enzyme iiiglc of the phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system. J Bacteriol 167:393–395. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.393-395.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park YH, Lee BR, Seok YJ, Peterkofsky A. 2006. In vitro reconstitution of catabolite repression in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 281:6448–6454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512672200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deutscher J, Aké FMD, Derkaoui M, Zébré AC, Cao TN, Bouraoui H, Kentache T, Mokhtari A, Milohanic E, Joyet P. 2014. The bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system: regulation by protein phosphorylation and phosphorylation-dependent protein-protein interactions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 78:231–256. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00001-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greenberg EP, Hastings JW, Ulitzur S. 1979. Induction of Luciferase synthesis in Beneckea harveyi by other marine bacteria. Arch. Microbiol 120:87–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00409093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miller, JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY. Cold Spring Harbor Press. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee KJ, Jeong CS, An YJ, Lee HJ, Park SJ, Seok YJ, Kim P, Lee JH, Lee KH, Cha SS. 2011. Frsa functions as a cofactor-independent decarboxylase to control metabolic flux. Nat Chem Biol 7:434–436. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meredith SC. 1984. The determination of molecular weight of proteins by gel permeation chromatography in organic solvents. J Biol Chem 259:11682–11685. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(20)71263-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vermeire PJ, Lilina AV, Hashim HM, Dlabolová L, Fiala J, Beelen S, Kukačka Z, Harvey JN, Novák P, Strelkov SV. 2023. Molecular structure of soluble vimentin tetramers. Sci Rep 13:8841. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-34814-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. NY. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Labugger R, Organ L, Collier C, Atar D, Van Eyk JE. 2000. Extensive troponin I and T modification detected in serum from patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 102:1221–1226. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.11.1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jeong HS, Jeong KC, Choi HK, Park KJ, Lee KH, Rhee JH, Choi SH. 2001. Differential expression of Vibrio vulnificus elastase gene in a growth phase-dependent manner by two different types of promoters. J Biol Chem 276:13875–13880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010567200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gel permeation chromatography of standard proteins.

PAGE analysis of the mixture of d-IIAGlc and DctDD57Q.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.