Abstract

“Helicopter research” refers to a practice where researchers from wealthier countries conduct studies in lower-income countries with little involvement of local researchers or community members. This practice also occurs domestically. In this Commentary, we outline strategies to curb domestic helicopter research and to foster equity-centered collaborations.

Imagine you are a researcher from an academic institution with very limited resources. You are introduced to investigators from a large, well-resourced institution eager to apply for a center grant aimed at eradicating cancer health disparities—a collaboration that comes with the allure of cutting-edge technology. However, as you discuss the details of the collaboration, you quickly realize that the majority of the funding will be allocated to faculty salaries (mostly male and from well-represented backgrounds). You find it curious that you are only offered a “co-investigator” role rather than the more equitable “multiple principal investigator” (MPI) role for your contribution to the project, and community engagement is an afterthought with little to no input from community members impacted by research in this field. The whole project is reminiscent of a military operation that is quickly in and out, with little regard for the long-term impact on the community. This is a form of “parachute research” or “helicopter research.”

Defining domestic helicopter research

Helicopter research is a term that has historically been used in global health research to describe the practice of scientists from wealthier countries conducting research in low- and middle-income countries with little to no involvement of local communities or local researchers.1,2 This approach, often criticized for lacking cultural sensitivity and equitable collaborations,3–5 is not confined to international contexts. It also occurs domestically.

Domestic helicopter research mirrors helicopter research but is distinct in its setting. Rather than engagement across countries, domestic helicopter research occurs within a single country. It is a practice where researchers from more privileged institutions or companies conduct studies in or collect data about marginalized communities with little to no involvement of local researchers or community members. This practice often exploits communities, such as those of Indigenous Peoples, Black, or Latine groups,6 as well as resource-limited institutions (RLIs) that serve these communities, including many minority-serving institutions. Resource-limited institutions are defined here as institutions holding an average of less than $50 million per year of NIH support for the past three fiscal years. They often have strong historical ties to under-resourced communities but are not always classified as minority-serving institutions (which is based on student populations).

Domestic helicopter research is also distinct in its approach, focusing on the dynamics of national inequities rather than international disparities. It often involves a top-down approach that neglects the perspectives, needs, and expertise of the community being studied, focusing primarily on the researchers’ interests or the goals of an external entity. We use this term to highlight the lack of true partnership, community involvement, and sustainable benefits for the communities and RLIs in studies that include aspects of race, ethnicity, or genetic ancestry.

We write this commentary based on our experiences and perspectives as a multidisciplinary team of health equity researchers, including two deans, a chair, an associate vice president for research, and a university president, who have served in leadership positions at multiple types of U.S. institutions. Although this Commentary centers the experiences and voices of U.S. researchers and institutions, the term “domestic helicopter research” extends well beyond the U.S. Similar institutional inequities and research dynamics are present in various countries around the world. We draw parallels between the common practice of helicopter research within global health and related fields4,7 to the conduct of inequitable research practices performed domestically with RLIs that serve populations with health disparities. Finally, we also provide examples of potential harms to RLIs, the communities they serve, and the broader health equity field while offering potential strategies to end the use of domestic helicopter research.

Examples of domestic helicopter research

Sometimes, well-intentioned academic efforts can inadvertently perpetuate systemic inequities within marginalized communities. For example, investigators from an academic institution may intentionally recruit participants from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups to examine potential differences in drug efficacy or adverse reactions for a clinical trial. However, the institution oftentimes does not have strong ties to community stakeholders who can inform the design, implementation, and interpretation of various studies. Other times, there is an intention from researchers to develop a long-lasting, equitable partnership with a local RLI serving that community, but there is a lack of significant resources devoted to the RLI. This can create a dependency on external expertise and result in partnerships that are not sustainable or even applicable to community needs and priorities. These approaches reinforce structural inequities by limiting or providing no influence and control over the collaboration’s resources, data, and dissemination efforts to the impacted community members and collaborating researchers with historical ties and commitments to that community.8

In their 2020 article, Brown and colleagues provide an in-depth reflection of a case study chronicling events that transpired between an HIV researcher and local community members.5 To summarize, the HIV researcher worked out of state and asked a local community leader to collaborate on a survey on HIV and aging. The community leader agreed, given the importance of the topic within the community. Throughout the process, the researcher refused to share pertinent study-related materials prior to submission of the study to the university’s institutional review board (IRB). Further, the community leader bore the burden of recruiting community members and the financial costs of securing space to conduct the survey. Once the survey materials were shared after IRB approval, the community leader discovered that the survey contained stigmatizing and outdated terminology, violated respect for the gender identities of participants, provided no compensation to participants within the survey, and included no plans for dissemination of the data and results.

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated racial injustices revealed a greater awareness and acknowledgment of the impact of structural racism and social injustices on health disparities to those who previously had the privilege of not paying attention.9,10 This increased awareness prompted researchers from various disciplines to expand their focus and incorporate health equity research into their studies. It led to calls from several journals for papers and special editions focused on health inequities. Funders, policymakers, and academic institutions also emphasized the need for interdisciplinary collaborations and a more comprehensive approach to biomedical research that incorporates aspects of diversity and equity. This sudden interest in health disparities research and scholarship has been referred to as “health equity tourism.” Together, these practices increased opportunities for domestic helicopter research. However, without deep-rooted knowledge of how structural factors operate to sustain health disparities within specific communities, superficial attempts to address deep injustices may lead to harmful unintended consequences.

Consequences of domestic helicopter research

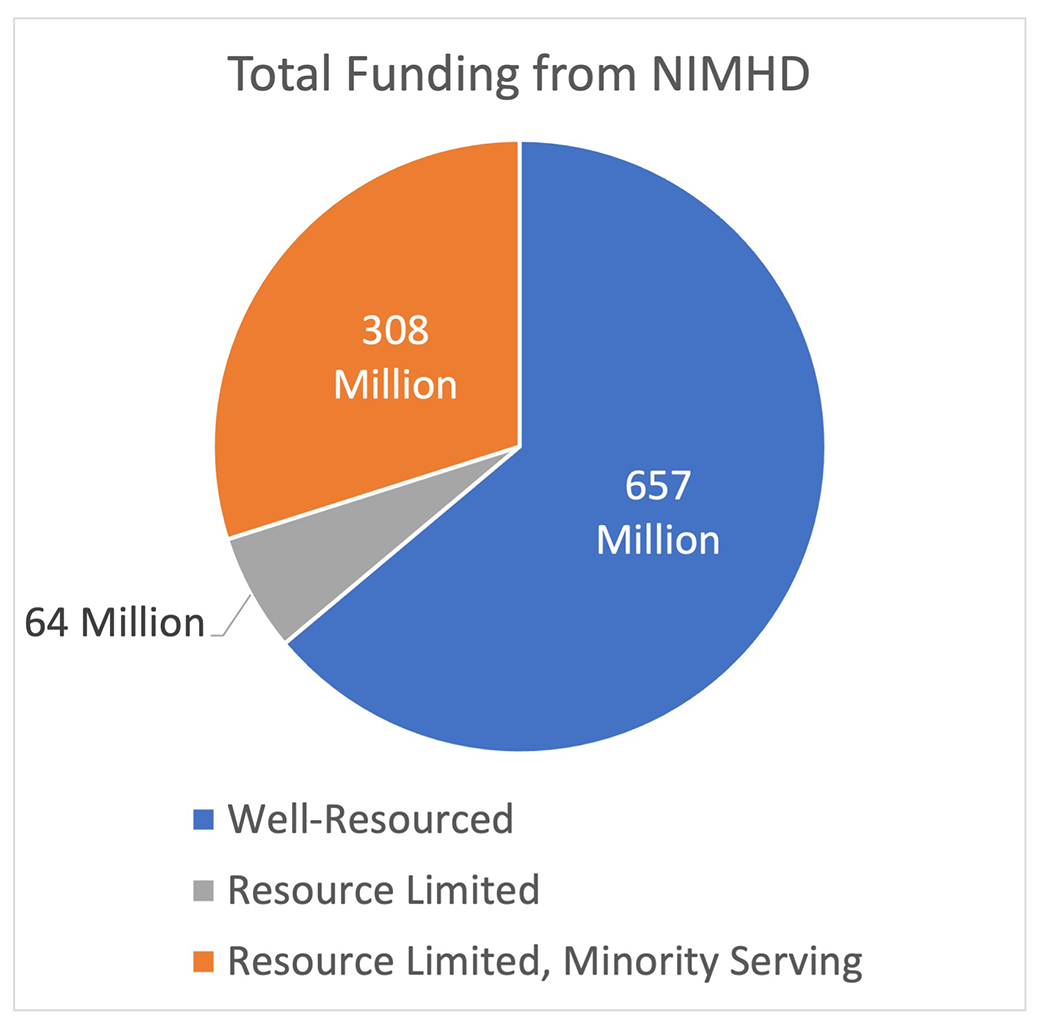

The consequences of domestic helicopter research have far-reaching implications across various domains. As observed in the examples above, it erodes trust between researchers and the communities they aim to serve, leading to a breakdown in effective collaboration and community engagement. Secondly, domestic helicopter research saps funding from RLIs that serve underrepresented populations, thereby limiting resources for long-term impact with underserved communities. Only 30% of funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) over the past three fiscal years has gone to RLIs that serve underrepresented populations (Figure 1). Capacity-building initiatives must be maintained at RLIs. The historical lack of investment in infrastructure at RLIs has perpetuated structural inequities in funding, hindering RLIs’ ability to adequately address health disparities in their surrounding communities.

Figure 1. Total funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Total funding from the top 100 institutions funded by NIMHD over the 2020, 2021, and 2022 fiscal years. Well-resourced institutions are defined as holding an average of more than $50 million per year of NIH support for the past three fiscal years (2020–2022). Resource-limited institutions hold an average of less than $50 million per year of NIH support for the past three fiscal years. Resource-limited, minority-serving institutions are resource-limited institutions that have an additional historical and current mission to educate students from any of the populations that have been identified as underrepresented in biomedical research as defined by the National Science Foundation (i.e., African Americans or Blacks, Hispanic or Latino Americans, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, U.S. Pacific Islanders, and persons with disabilities).

Additionally, domestic helicopter research degrades the quality of scholarship within the field, diverting attention from critical self-reflections and advancements from long-standing scholars. For example, many researchers continue to frame health research within minoritized communities through deficit-based models, which focus on what individuals or communities lack and emphasize weaknesses or gaps, rather than asset-based models, which center individuals’ or communities’ strengths and resources while highlighting their potential and capabilities. This approach further exacerbates inequities by favoring existing structures and practices, thereby shifting resources away from disruptive innovations essential for sustainable health equity transformation. Domestic helicopter research misses opportunities to address racism as a major driver of disparities and focus on race as a contributing factor to disparities. Finally, domestic helicopter research lacks the inclusion, development, and advancement of underrepresented faculty from RLIs, hindering the progression of talented researchers who prioritize community advancement over individual advancement.

Strategies for ending domestic helicopter research

Several strategies exist to curb the practice of domestic helicopter research and promote more equitable and mutually beneficial collaborations with RLIs (Table 1). The first strategy is predicated on the idea of involving RLI researchers in the research process from the very beginning.11 Do not wait until research funding announcements are released. Take time beforehand to visit the RLI campus and community and invite potential collaborators to give a talk. Much like community-based participatory research (CBPR), it is important to engage local RLIs at the earliest stages of idea development, rather than waiting until the idea is fully developed. The hallmark of CBPR is active and equitable involvement of the community in every aspect of the research process.11 Using principles of CBPR (discussed further below) allows RLIs and community partners to have greater input and ownership and can help to ensure that research is relevant and responsive to community needs and priorities.

Table 1.

Strategies for equitable research collaboration with RLIs

| Strategy | What it addresses | Measurable outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Take extra time to meet with RLI collaborators before the start of the planning | Building mutual trust | • Visiting the RLI campus • Inviting RLI investigators to give talks • Meeting with senior leadership |

| Engage local community partners throughout the research process with a Community Advisory Board | Shared values and goals | • Increased recruitment • Research is responsive to community needs |

| Ensure equitable distribution of funding | Resource Equity | • A significant subaward to the RLI and/or CBO • Cost share or other “in-kind contributions” |

| Share institutional resources and infrastructure | Resource Equity | • Shared core facilities • Access to software, tools, and equipment |

| Engage senior faculty from both institutions to serve as mentors and preceptors | Capacity building | • Advancement of underrepresented investigators • Sharing of diverse perspectives |

| Extend opportunities for authorship and for RLIs to be lead authors on manuscripts | Capacity building | • Increased first and senior authorship for all investigators to demonstrate independence |

| Disseminate findings directly to the community | Accountability and long-term benefits | • Townhalls or workshops directly with community members • Community education |

RLI, resource-limited institution (an institution that serves populations with health disparities); CBO, community-based organization.

Another key strategy is to ensure that there is an equitable distribution of resources and funding from the research. This could involve a subaward to the RLI or community-based organization or even the shared use of core facilities or access to tools, software, and equipment. In addition, researchers from RLIs must receive appropriate credit and recognition for their contributions to the research, both on grant applications and in publications. Include investigators whose contributions are integral to the project as a principal investigator (PI) and not simply as a co-investigator, advisor, or consultant.

Funding agencies play a pivotal role in shaping equitable research landscapes. These agencies must ensure that funding criteria and processes accommodate the unique challenges that RLIs face. One recommendation is the implementation of an anonymized review process, which can alleviate biases based on the reputation or perceived prestige of the involved institutions and focus purely on the quality and relevance of the proposed research. Another important change would involve lengthening the turnaround times for funding opportunities. The often-rushed period between a funding announcement and its application deadline is a significant barrier for RLIs, preventing them from adequately planning, building robust collaborations, and preparing comprehensive proposals. Funding bodies such as the NIH should not only continue to announce opportunities geared toward transformative health equity research but also incorporate structured planning periods. This would allow adequate time for the establishment of collaborations between institutions and for the development of research proposals that genuinely reflect the needs and expertise of all involved parties, particularly the communities that are meant to benefit from the research. Recent examples of NIH initiatives to advance these efforts include the Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society (ComPASS) initiative, which provides opportunities for community partners to direct research programs as lead institutions. Another example is the John Lewis NIMHD Research Endowment Program (S21), which provides support for research infrastructure within RLIs.

Responsibility for effecting change in research partnerships should not solely rest on funding agencies or well-resourced institutions. There is a pressing need for the leadership of RLIs to advocate for their institution’s role in research partnerships. This advocacy is not just about securing an equitable collaboration; it’s about ensuring the partnerships best align with the needs and priorities of communities they serve. RLIs should also consider the power of collective action in advocating for their roles in research partnerships. By forming coalitions, these institutions can amplify their voices, ensuring that their needs and perspectives are adequately represented in research funding agendas. The success of HBCU (historically Black colleges and universities) coalitions, which have attracted substantial investments for educational and employment advancements, demonstrates the potential of such collaborations. Such collective action would enable RLIs to assert their expertise, negotiate equitable partnerships, and drive research initiatives that truly reflect and serve their communities.

There have been some examples of successful collaborations between RLIs and researchers from institutions with high research activity that serve as positive alternatives to domestic helicopter research. One such example is the longterm partnership between Meharry Medical College and Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Since 1999, this collaboration has involved the participation of leadership at the highest level to form a Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance.12 This formal alliance has included joint research training programs, shared library services and informatics, and collaboration with community partners, focusing on care for the uninsured, poorly insured, and underserved populations. The Research Centers in Minority Institutions (RCMIs), along with their community engagement cores, also serve as models in overcoming the long-standing and present obstacles to conducting research in communities facing a disproportionate burden of health disparities.13

Collaborating with community-based organizations (CBOs) can also help curb domestic helicopter research and mitigate already strained relationships between universities and minoritized communities. For instance, the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health in Brooklyn, NY, well-known for its health promotion programs using barbershops and salons, has been a fundamental, long-term partner in SUNY Downstate’s Brooklyn Health Disparities Center.14 They have been a conduit by which Downstate researchers have been able to further build trust with the surrounding community. Additionally, collaborating with underrepresented community stakeholders can bring diverse perspectives and insights to the research, resulting in more innovative and impactful outcomes.

Community-based participatory research and community-engaged research

To critically assess the limitations of domestic helicopter research, it is essential that the research community understand and acknowledge the distinction between CBPR and community-engaged research. CBPR can be defined as a collaborative research approach that involves active partnership and close collaboration between researchers and the community, where all participants work together in the design, conduct, and application of the research. In contrast, community-engaged research is generally considered to be a broader term that encompasses various levels of community involvement, ranging from merely informing communities about research to fostering partnerships for shared decision-making. While community-engaged research can be seen as a stepping stone toward CBPR, it lacks the clearly defined steps to achieve the full level of partnership. Consequently, most attempts at CBPR end up as community-engaged research. This divergence often arises from researchers lacking the time or planning to go through the comprehensive steps necessary to achieve CBPR.

The lack of a sustained, holistic application of CBPR has significant implications for health disparities research. Researchers should consider situations where a hybrid approach might be suitable, integrating both CBPR for non-emergent research and community-engaged research in more immediate situations. One prime example of this is the recent COVID-19 pandemic. The speed and urgency of the situation necessitated rapid research responses that could not always adhere to the complete CBPR process. However, it also underlined the importance of community engagement in research, even in emergency situations.

Most COVID-19 vaccine trials, for example, did not include substantive numbers of Black and Asian participants, resulting in insufficient representation, which contributes to overall mistrust of the medical system. This exemplifies a situation where community-engaged research could address an emergency—facilitating the recruitment and inclusion of underrepresented populations in urgent trials. Such an approach would involve community stakeholders or RLIs in the research design and implementation, offering a solution to the disparity while navigating the constraints of the emergent situation. Simultaneously, researchers should pursue CBPR for non-emergent aspects, ensuring long-term equity, partnership, and sustainable benefits for the community.

Conclusion

In order to move forward and achieve true equity-centered collaborations with RLIs that serve populations experiencing health disparities, we must critically examine and challenge existing power dynamics and prioritize the inclusion and empowerment of RLI researchers and their communities. This requires adopting collaboration models that are more responsive to the needs and priorities of local communities and an investment in researchers serving these populations. We also must recognize and acknowledge the historical contexts that have shaped these power dynamics and address and rectify past wrongs.

Ending domestic helicopter research would transform science and medicine in profound ways. By shifting to an approach rooted in authentic collaboration and community engagement, researchers would gain a deeper understanding of the nuanced factors that contribute to health disparities, enabling them to develop more effective and sustainable interventions and treatments tailored to diverse populations. RLIs and communities that had once been marginalized would become empowered stakeholders, driving the research agenda and ensuring that studies address their unique needs and priorities. Moreover, this paradigm shift would promote inclusivity, diversity, and cultural and structural humility within academia and healthcare, improving the science and practice of health equity. Deploying the strategies discussed in this Commentary requires fundamental institutional changes to how partnerships are formed and sustained, as well as funder-driven initiatives to galvanize these efforts. But doing so will result in better science and health for all.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

W.M.L., M.C.-R., C.B.-F., M.S., and W.J.R. are supported by the NIMHD of the NIH under award number S21MD012474. W.M.L., M.C.-R., and C.B.-F. also acknowledge support from the NIMHD under award number R25MD017950 and the NCI under award number U54CA280808. M.C.-R. acknowledges support from the NIOSH under award number R03OH012215. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

W.J.R. receives compensation (>$10,000) and serves on the boards of three for-profit healthcare companies: HCA Healthcare, Compass Pathways, LLC, and HeartFlow, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adame F. (2021). Meaningful collaborations can end ‘helicopter research’. Nature. 10.1038/d41586-021-01795-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haelewaters D, Hofmann TA, and Romero-Olivares AL (2021). Ten simple rules for Global North researchers to stop perpetuating helicopter research in the Global South. PLoS Comput. Biol 17, e1009277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker M, and Kingori P (2016). Good and Bad Research Collaborations: Researchers’ Views on Science and Ethics in Global Health Research. PLoS One 11, e0163579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefanoudis PV, Licuanan WY, Morrison TH, Talma S, Veitayaki J, and Woodall LC (2021). Turning the tide of parachute science. Curr. Biol 31, R184–R185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown B, Taylor J, Dubé K, Kuzmanović D, Long Y, and Marg L (2021). Ethical Reflections on the Conduct of HIV Research with Community Members: A Case Study. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 16, 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith LT (2021). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (Bloomsbury Publishing; ). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ou SX, and Romero-Olivares AL (2019). Decolonizing Ecology for Socially Just Science. https://magazine.scienceconnected.org/2019/08/decolonize-science-with-global-collaboration/. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Lancet Global Health (2018). Closing the door on parachutes and parasites. Lancet. Glob. Health 6, e593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, and Pérez-Stable EJ (2020). COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA 323, 2466–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowkwanyun M, and Reed AL (2020). Racial Health Disparities and Covid-19 — Caution and Context. N. Engl. J. Med 383, 201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, and Becker AB (1998). REVIEW OF COMMUNITY-BASED RESEARCH: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 19, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance. https://www.meharry-vanderbilt.org.

- 13.Henry Akintobi T, Sheikhattari P, Shaffer E, Evans CL, Braun KL, Sy AU, Mancera B, Campa A, Miller ST, Sarpong D, et al. (2021). Community Engagement Practices at Research Centers in U.S. Minority Institutions: Priority Populations and Innovative Approaches to Advancing Health Disparities Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 6675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health (1992). https://www.arthurasheinstitute.org/.