Abstract

Background:

Lung cancer diagnosis, staging and treatment may be enhanced by multidisciplinary participation and presentation in multidisciplinary meetings (MDM). We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to explore literature evidence of clinical impacts of MDM exposure.

Methods:

A study protocol was registered (PROSPERO identifier CRD42021258069). Randomised controlled trials and observational cohort studies including adults with nonsmall cell lung cancer and who underwent MDM review, compared to no MDM, were included. MEDLINE, CENTRAL, Embase and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched on 31 May 2021. Studies were screened and extracted by two reviewers. Outcomes included time to diagnosis and treatment, histological confirmation, receipt of treatments, clinical trial participation, survival and quality of life. Risk of bias was assessed using the ROBINS-I (Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions) tool.

Results:

2947 citations were identified, and 20 studies were included. MDM presentation significantly increased histological confirmation of diagnosis (OR 3.01, 95% CI 2.30–3.95; p<0.00001) and availability of clinical staging (OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.43–4.56; p=0.002). MDM presentation significantly increased likelihood of receipt of surgery (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.29–3.12; p=0.002) and reduced the likelihood of receiving no active treatment (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.21–0.50; p=0.01). MDM presentation was protective of both 1-year survival (OR 3.23, 95% CI 2.85–3.68; p<0.00001) and overall survival (hazard ratio 0.63, 95% CI 0.55–0.72; p<0.00001).

Discussion:

MDM presentation was associated with increased likelihood of histological confirmation of diagnosis, documentation of clinical staging and receipt of surgery. Overall and 1-year survival was better in those presented to an MDM, although there was some clinical heterogeneity in participants and interventions delivered. Further research is required to determine the optimal method of MDM presentation, and address barriers to presentation.

Shareable abstract

Multidisciplinary meeting presentation is a relatively low-cost intervention providing substantial benefits in receipt of active treatment and survival. Up to 40% of patients remain unpresented, risking disparity and inequity in treatment and outcomes. https://bit.ly/48yNyxi

Introduction

Lung cancer is a heterogeneous and complex cancer, in which diagnosis, staging and treatment decision-making demands careful consideration of diverse patient, disease and management factors. The rapid evolution of diagnostics and therapeutics and the complex need for multimodality therapies in primary, neoadjuvant and adjuvant roles demands diverse expertise from a range of clinical craft groups to achieve optimal decision-making [1]. The complexity of this evaluation has precipitated recommendations that all patients presenting with lung cancer be evaluated in a multidisciplinary context [2–4].

Multidisciplinary discussion aims to increase the utilisation of evidence-based management, improve treatment access and enhance coordination and communication between health professionals [5, 6]. Some of the benefits attributable to multidisciplinary meeting (MDM) presentation include increased accuracy and completeness of diagnosis and staging [7–9], better adherence to therapeutic guidelines [8, 10], increased [7, 11] and earlier provision of treatment [8], decreased length of hospital admission [12], increased enrolment in clinical trials and increased referrals to palliative care [7, 13].

Multidisciplinary evaluation in lung cancer requires the coordinated and timely collaboration of a diverse array of craft groups. This logistical demand has resulted in diverse approaches to multidisciplinary activity with groups meeting weekly to monthly, in person and virtually, prior to and following diagnosis and or treatment in single institutions and across hospital networks [14].

The use of MDM presentation has been explored in a range of retrospective and prospective studies suggesting patient benefits in accuracy and completeness of clinical staging, increased enrolment in clinical trials, variable effects on survival and impacts on management coordination and unwarranted variation [1]. The confirmation of benefit of MDM is critically important to the formulation of practice guidelines around the need for MDM utilisation.

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing literature to explore the impacts of MDM presentation on management and outcomes in the most common form of lung cancer, nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We sought to answer three questions: 1) what is the impact of MDM management on management processes in NSCLC; 2) what impact does MDM presentation have on receipt of treatment; and 3) what impact does MDM presentation have on survival in NSCLC?

Methods

Protocol and registration

A study protocol was developed and registered in the PROSPERO register of systematic reviews accessible at www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (CRD42021258069).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria included all subjects with NSCLC diagnoses, in adults aged >18 years. All cancer stages were included. We included randomised controlled trials and prospective or retrospective observational cohort studies comparing patients who underwent lung cancer MDM (tumour board) discussion with patients who had care not including MDM discussion. We excluded patients with small cell lung cancer and other thoracic malignancies.

Information sources and search strategy

A search strategy was devised (supplementary table S1), and databases searched included MEDLINE; Ovid SP from 1946 to date; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), via the Cochrane Register of Studies, all years to date; Embase Ovid SP 1974 to date; US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov; World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch) and PsycInfo. Searches were conducted on 31 May 2021 and updated to 2 January 2024.

Selection process

Citation title and abstracts were reviewed in Covidence (www.covidence.org/) independently by two reviewers (A. Harrison and R. Stirling) using specified eligibility criteria and consensus confirmed by study discussion. Studies selected for full-text review were reviewed independently by two reviewers (A. Harrison and R. Stirling) and consensus achieved after discussion with a third reviewer (H. Barnes).

Data collection process

Data were extracted independently by each assessor (V. Lee and R. Stirling) using a standardised data collection form on Covidence. Details regarding study identification, methods, patient population, interventions and outcomes were collected and consensus between assessors achieved by comparing the two forms and discussing any discrepancies.

Data items

Histological diagnosis was identified when studies reported histological confirmation of lung cancer or histological categorisation of adenocarcinoma, squamous cell cancer, large cell cancer or histology not otherwise specified. Clinical staging was confirmed by reporting of tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) stage summary prior to treatment. Receipt of treatment was confirmed by reporting of receipt of surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or palliative care. Clinical trial participation was confirmed by reporting of clinical trial enrolment. Survival was confirmed by survival fractions in MDM and non-MDM cohorts.

Risk-of-bias assessment

Risk of bias was assessed using the ROBINS-I (Risk of Bias in Non-randomised Studies – of Interventions) tool for nonrandomised studies of interventions [15]. Risk of bias was assessed by two reviewers (V. Lee and J. Taverner) and discrepancies resolved with consensus review. This tool evaluates risk in relevant domains including confounding, selection, deviation from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes and selection of the reported result. Risk-of-bias assessment results are displayed using the robvis visualisation tool [16].

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Effect measures for dichotomous outcomes were assessed by reporting odds ratios for difference between intervention (MDM exposed) and control groups, providing a ratio of the probability that a particular event will or will not occur. Odds ratios were calculated using the Mantel–Haenszel method using random-effects analysis modelling due to clinical study heterogeneity. Effect measures for continuous outcome survival measures were reported as hazard ratio (HR) or odds ratio, providing a ratio of the survival probability using an inverse variance model and random-effects modelling due to study heterogeneity. All analyses were conducted using the Review Manager (RevMan version 5.3; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Chi-squared and I2 tests. An I2 value between 50% and 75% was regarded as substantial heterogeneity and an I2 value of ≥75% as considerable heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were performed by study design, by participant type, and by intervention type, to explore heterogeneity.

Results

Study selection

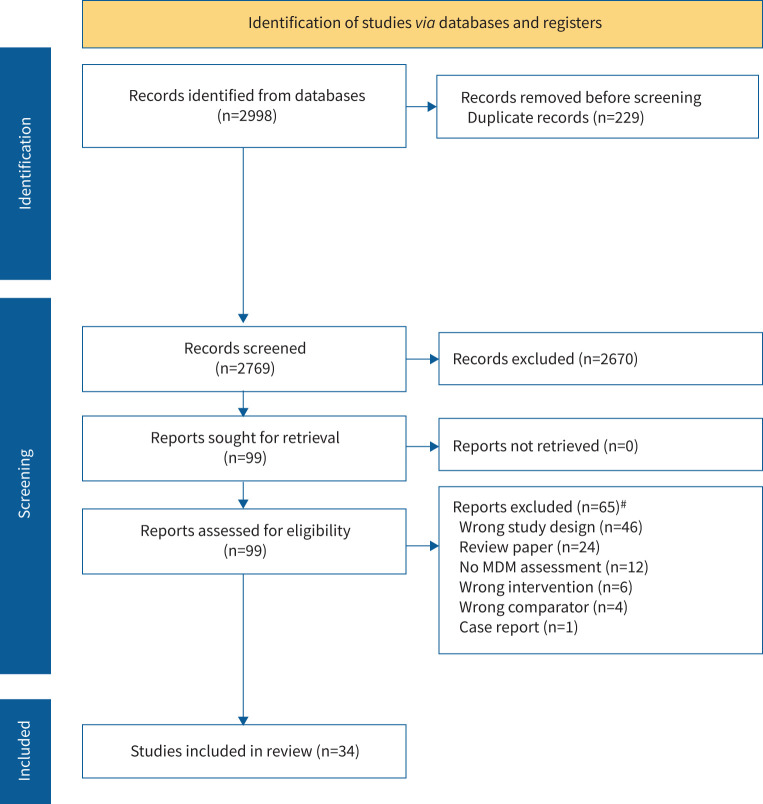

2998 articles were retrieved from the search of databases in addition to hand-searching of reference lists in relevant articles. After removal of 229 duplicates, 2769 titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion and 99 citations selected for full-text review, of which 20 studies were selected for inclusion (figure 1) [5, 7, 17–33].

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram summarising search results and study selection. MDM: multidisciplinary meeting. #: some studies were removed for a number of reasons.

Study characteristics

The search strategy provided 20 studies for systematic review and 14 studies for meta-analysis (table 1) [5, 7, 17–34]. Among the included studies were 18 retrospective cohort studies, one qualitative research study and one mixed retrospective and prospective observational cohort study. International representation included Australia, USA, Canada, Taiwan and Scotland. Nine were single-centre and 11 multicentre studies. All studies included participants with NSCLC. Ray et al. [20] excluded those with an unknown clinical stage; Peckham and Mott-Coles [29] and Stevens et al. [34] only included those with stage I or II NSCLC; Hung et al. [25] only included those with stage III NSCLC; Freeman et al. [18] only included those with stage I–III NSCLC; and Bydder et al. [23] and Forrest et al. [24] only included those with inoperable stage III or IV NSCLC. Tamburini et al. [32] only included those who underwent surgery with curative intent; and Pan et al. [28] and Wang et al. [31] only included those who received treatment.

TABLE 1.

Results of studies included in the meta-analysis

| First author, year [ref.] | Setting | Study design | Patient group | MDM exposure (in detail) | Comparator | Outcomes |

| Forrest, 2005 [24] | 1997 and 2001 Glasgow, UK |

Retrospective/prospective cohort study | MDM group n=126; non-MDM group n=117 Consecutive presentations of inoperable stage III–IV NSCLC |

Implementation of MDM (two respiratory physicians, two surgeons, a medical oncologist, a clinical oncologist, a palliative care physician, a radiologist and a specialist respiratory nurse) | Prior to implementation of MDM in 1998 | From 1997 to 2001, receipt of chemotherapy increased from 7% to 23% (p<0.001) and median survival increased from 3.2 months to 6.6 months (p<0.001) |

| Stevens, 2008 [34] | 2004–2006 Auckland, New Zealand |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=81; non-MDM group n=59 Consecutive presentations of stage I–II NSCLC |

Presented to MDM (several medical specialist groups) | Not presented to MDM | MDM discussion was associated with increased likelihood of curative management (p<0.001) |

| Bydder, 2009 [23] | 2006–2008 Nedlands, Western Australia |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=81; non-MDM group n=17 Consecutive presentations of inoperable stage III or IV NSCLC captured from an Australian tertiary hospital cancer registry database |

Presented to MDM (respiratory physicians, cardiothoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, a radiation oncologist, a palliative care physician, a radiologist, a pathologist, a nuclear physician, a specialist lung cancer nurse as well as doctors receiving specialist training) | Not presented to MDM | Those discussed at MDM had better survival than those not discussed Mean survival 280 days versus 205 days (log-rank p=0.048) |

| Bjegovich-Weidman, 2010 [22] | 2007–2009 Wisconsin, USA |

Retrospective cohort study | Consecutive presentations of SCLC and NSCLC (patients from Aurora Medical Center– Sheboygan, a community hospital serving a predominantly rural county population) | Implementation of MDC (a thoracic surgeon, radiation and medical oncologists and a cancer care coordinator) | Prior to implementation of MDC | MDC implementation resulted in reduced mean time from diagnosis to initiation of treatment (18 days from 24 days) All patients were treated with definitive minimally invasive surgery Tertiary hospital thoracic surgical referrals increased by 75% |

| Boxer, 2011 [7] | 2005–2008 South West Sydney, Australia |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=504; non-MDM group n=484 Consecutive presentations of SCLC, NSCLC and radiologically confirmed primary lung cancer with no pathological confirmation (captured from the South West Sydney Clinical Cancer Registry) |

Presented to MDM (radiation and medical oncologists, respiratory physicians, a cardiothoracic surgeon, radiologist, nuclear medicine physician, lung cancer care coordinator and trainee specialists) | Not presented to MDM during the same period | Treatment receipt for MDM patients versus non-MDM patients was 12% versus 13% for surgery (p>0.05); 66% versus 33% for radiotherapy (p<0.001); 46% versus 29% for chemotherapy (p<0.001); and 66% versus 53% for palliative care (p<0.001) MDM discussion did not influence survival |

| Mitchell, 2013 [33] | 2003–2008 Victoria, Australia |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=234; non-MDM group n=607 Consecutive presentations of SCLC, NSCLC and clinically diagnosed lung cancer (from 1 January to 30 June 2003 and identified by Victorian Cancer Registry) |

Presented to MDM | Not presented to MDM | Patients discussed at MDM were more likely to receive active treatment (81.6% versus 70.5%, p=0.004), and had improved survival (10.8 versus 5.5 months, p<0.001) |

| Keating, 2013 [26] | 2001–2005 USA |

Retrospective cohort study | Consecutive presentations of SCLC and NSCLC (captured from Department of Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry) | Presented to MDM (surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists, social workers and palliative care specialists) | Patients at a facility with no MDM | Patients presented to hospitals with MDMs were less likely to receive radiotherapy for unresected stage I–II NSCLC (63.8% versus 66.5%, p=0.04), and more likely to receive chemoradiotherapy for unresected stage IIIA NSCLC (35.6% versus 23.9%, p=0.02), and more likely to receive chemoradiotherapy for limited stage SCLC (62.9% versus 28.4%, p<0.001) There were no survival differences |

| Wang, 2014 [31] | 2005–2007 Taiwan |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=2736; non-MDM group n=20 081 (before PS), MDM group n=2724; non-MDM group n=5448 (after PS) Consecutive presentations of SCLC and NSCLC |

Presented to MDT (clinical physicians, nursing staff, a psychological consultant, a social worker and a case manager) | Not specified (MDT nonparticipants, conventional treatments) | MDM participation was associated with an 11% lower likelihood of visit to an ED (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.80–0.98) |

| Freeman, 2015 [18] | 2008–2013 Charlotte, NC, USA |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=6627; non-MDM group n=6627 Consecutive presentations of stage I–III NSCLC |

Presented to MDM (medical and radiation oncology and thoracic surgery) | No access to MDM | Prospective MDM presentation improved adherence to national guidelines (p<0.0001) for staging and treatment (p<0.0001), timeliness of care (p<0.0001) and reduction in costs (p<0.0001) |

| Pan, 2015 [28] | 2005–2011 Taiwan |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=4632; non-MDM group n=27 937 Consecutive presentations of NSCLC (patients who received treatment within the first year after diagnosis were captured from the 2005–2010 Taiwan Cancer Registry using ICD codes) |

Presented to MDM | Not specified (MDM nonparticipants) | The adjusted HR of death of MDM participants with stage III and IV NSCLC was significantly lower than that of MDM nonparticipants (adjusted HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.84–0.90) |

| Rogers, 2017 [30] | 2009–2012 South West Victoria, Australia |

Retrospective cohort study | Lung cancer MDM group n=386; non-MDM group n=207 Consecutive presentations of SCLC and NSCLC (from Barwon Health MDM programme) |

Presentation to MDM (treating physicians including at least one surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, pathologist, radiologist and respiratory physician, as well as allied health and supportive care staff) | Treatment plan not discussed at MDM | MDM presented patients had an adjusted reduction in mortality (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.50–0.76, p<0.01) |

| Bilfinger, 2018 [21] | 2002–2016 New York, USA |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=1956; non-MDM group n=2315 Consecutive presentations of SCLC and NSCLC (abstracted from the Stony Brook University Hospital cancer registry) |

Presented to MDM (thoracic surgery, interventional pulmonology, medical oncology, radiation oncology and two dedicated nurse practitioners as the core group) | Serial treatment care model (patient and responsibility of care passed on to different specialists/subspecialists) | 5-year survival rates in propensity-matched sample were greater among MDM patients versus traditional care (33.6% versus 23.0%; p<0.001) Adjusting for potential confounders in the multivariable propensity-matched analyses, the MDM 5-year survival benefit was sustained (HR 0.65, 0.54–0.77) |

| Tamburini, 2018 [32] | 2008–2015 Ferrara, Italy |

Retrospective cohort study | MTB group n=246; non-MTB group n=186 (before PS), MDT group n=170; non-MDT group n=170 (after PS) Consecutive presentations of patients who underwent surgery with curative intent for NSCLC |

Discussion at weekly MTB with or without the patient present (MTB meeting attendees include surgeons, pulmonary oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, nuclear medicine specialists, pulmonologists, pathologists, lung cancer care coordinators and trainees) | Treated prior to the conference's implementation of the MTB (before 2012) | Patients discussed at MTB had better complete staging evaluation, early TNM stages and 1-year survival rate when compared with those who were not discussed at the MTB |

| Stone, 2018 [19] | 2006–2012 Sydney, Australia |

Retrospective cohort study | MDT group n=295; non-MDT group n=902 Consecutive presentations of SCLC and NSCLC (captured from local institutional clinical cancer registry, diagnosed or receiving at least one treatment for lung cancer at the St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney campus) |

Presentation to MDT (1-h weekly meetings chaired by a respiratory physician and attended by staff from a full range of medical subspecialities, nursing and allied health; patients may be presented at various points in the course of their care) | Not presented to MDT | Stage-specific survival was greater in the MDT group at 1, 2 and 5 years for all stages except stage IIIB at 1-year post-diagnosis Adjusted survival analysis for the entire cohort showed improved survival at 5 years for the MDT group (HR 0.7, 0.58–0.85; p<0.001) |

| Peckham, 2018 [29] | 2013–2015 California, USA |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=48; non-MDM group n=35 Consecutive presentations of stage I–II NSCLC |

Presentation to MDM (weekly meetings, coordinated and presented by the oncology nurse navigator) | Prior to implementation of MDM (specialists could assume care of patient at any point, no standardised use of guidelines, varied patient care) | After implementation, diagnosis of early-stage NSCLC and the use of diagnostic workups (pulmonologist, PFTs, PET-CT scan) increased Post implementation, a 37% increase was noted in the diagnosis of early-stage NSCLC |

| Hung, 2020 [25] | 2013–2018 Taipei, Taiwan |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=242; non-MDM group n=273 Consecutive presentations of stage III NSCLC (from chart and computer record of Taipei Veterans General Hospital) |

Presentation to MDM | Discussions on a case-by-case basis | The median survival of patients who were treated after MDM discussion was 41.2 months and that of patients treated without MDM discussion was 25.7 months (p=0.018) |

| Nemesure, 2020 [27] | 2006–2015 New York, USA |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=1179; non-MDM group n=865 Consecutive presentations of SCLC and NSCLC |

Presentation to MDM | Serial treatment care model (patient and responsibility of care passed on to different specialists/subspecialists) | A higher proportion of patients in the MDT remained disease-free at 1 year compared to standard care (80.0% versus 62.3%, p<0.01) Adjusted survival rates were significantly lower among LCEC participants (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.51–0.90 at 1 year; OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.36–0.70 at 3-years) Recurrence was lower at 3 years in the MDM group (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.32–0.79) |

| Linford, 2020 [17] | 2016–2017 Ontario, Canada |

Qualitative research study | MDC group n=6; non-MDC group n=6 Consecutive presentations of SCLC and NSCLC |

Presentation to MDM | Diagnosed via LDAP and managed by a respirologist in the LDAP either 3 months before or after MDC implementation, but external to MDC model | Patients in the MDC frequently reported convenience and a positive effect of family presence at appointments Physicians reported that MDC improved communication and collegiality, clinic efficiency, patient outcomes and satisfaction and consistency of information provided to patients |

| Ray, 2021 [20] | 2011–2017 Memphis, TN, USA |

Retrospective cohort study | eMTOC group n=864; non-eMTOC metropolitan group n=3464; non-eMTOC regional group n=1931 Consecutive presentations of NSCLC |

Presentation to MDM | Conventional referral processes (no other information) | eMTOC had the highest rates of stages I–IIIB (63 versus 40 versus 50), stage-preferred treatment (66 versus 57 versus 48), guideline-concordant treatment (78 versus 70 versus 63), and lowest percentage of nontreatment (6 versus 21 versus 28) (p<0.001) Compared with eMTOC, HR for death was higher in metropolitan (1.5, 95% CI 1.4–1.7) and regional (1.7, 95% CI 1.5–1.9) non-MTOC; hazards were higher in regional non-MTOC versus metropolitan (1.1, 95% CI 1.0–1.2) (p<0.05 after adjustment) |

| Lin, 2022 [5] | 2011–2020 Victoria, Australia |

Retrospective cohort study | MDM group n=5900; non-MDM group n=3728 Consecutive presentations of SCLC and NSCLC within VLCR |

Presentation to MDM | Not specified (MDM: formal meeting process with MDT participation) | Patients were less likely to be discussed at MDM if aged ≥80 years (OR 0.73, p<0.001), ECOG 4 (OR 0.23, p<0.001), clinical stage IV (OR 0.34, p<0.001) or referred from regional (OR 0.52, p<0.001) or private hospital (OR 0.18, p<0.001) Fewer non-MDM group participants received surgery (22.1% versus 31.2%), radiotherapy (34.2% versus 44.4%) and chemotherapy (44.7% versus 49.0%) MDM-presented patients had better median survival (1.70 versus 0.75 years, p<0.001) and lower adjusted mortality risk (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.71–0.80, p<0.001) |

MDM: multidisciplinary meeting; NSCLC: nonsmall cell lung cancer; SCLC: small cell lung cancer; MDC: multidisciplinary clinic; PS: propensity score matching; MDT: multidisciplinary team; ED: emergency department; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; HR: hazard ratio; MTB: multidisciplinary tumour board; TNM: tumour, node, metastasis; PFT: pulmonary function test; PET: positron emission tomography; CT: computed tomography; LCEC: Lung Cancer Evaluation Center; LDAP: Lung Diagnostic Assessment Program; eMTOC: enhanced multidisciplinary thoracic oncology conference; VLCR: Victorian Lung Cancer Registry; ECOG: Eastern Oncology Conference Group performance status.

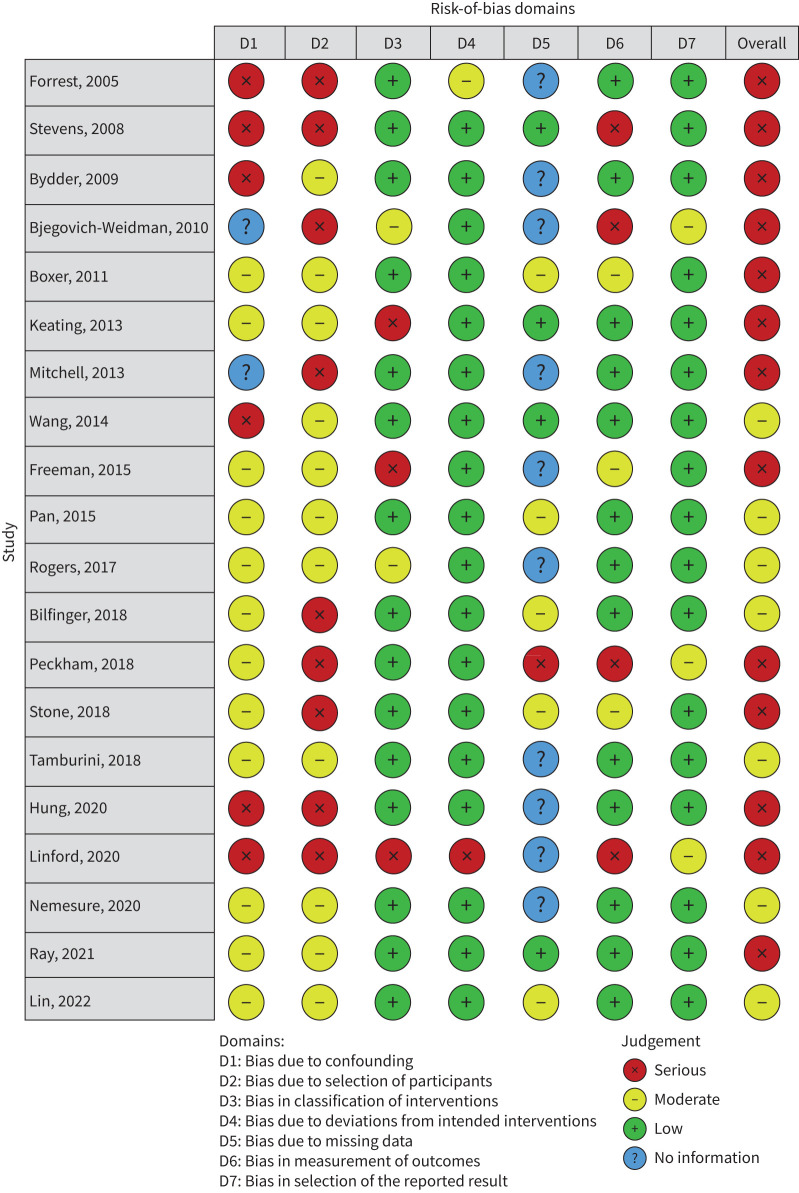

Risk of bias in studies

Risk-of-bias assessment results are displayed using the robvis visualisation tool [16]. The risk of bias was adjudged as moderate for seven studies and serious for 13 studies with the main causes of risk of bias being bias due to confounding, bias due to selection of participants and bias due to missing data (figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Risk-of-bias assessment.

Results of individual studies and syntheses

Management timeliness

Three studies reported data reflecting management timeliness. Boxer et al. [7] reported that patients in the non-MDM group had a slightly longer mean time from diagnosis to surgery, but had shorter mean time to curative radiotherapy, palliative chemotherapy and palliative care referral, although the difference was only statistically significant for those who received chemotherapy with palliative intent. Freeman et al. [8] reported a significantly reduced time from diagnosis to treatment for the MDM-presented group compared to the non-MDM-presented group (19±8 versus 32±11 days, p<0.0001). Bjegovich-Weidman et al. [22] reported on the establishment of an MDM evaluation process reporting a reduction in the time from diagnosis to initiation of treatment falling from a mean of 24 days to a mean of 18 days following MDM inception. There were insufficient data detail to consistently confirm improvement in diagnosis to treatment timeliness for various treatment modalities. There were no available data to report timeliness interval from referral to diagnosis.

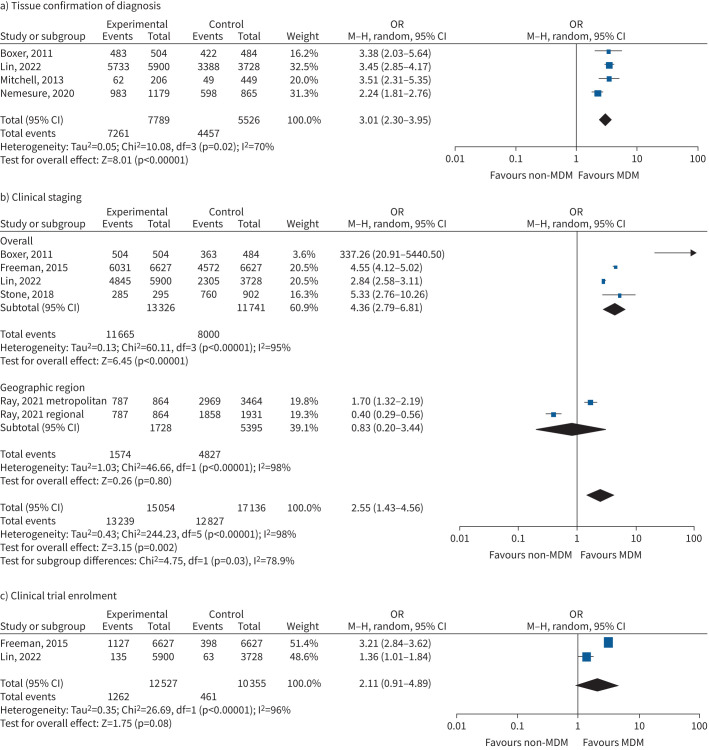

Histological confirmation of diagnosis

Four studies reporting on 13 315 subjects evaluated effects of MDM on histological confirmation of diagnosis, patients finding an increased odds of histological confirmation (OR 3.01, 95% CI 2.30–3.95, p<0.00001; 13 400 participants) with considerable statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared=10.08, p=0.02, I2=70%) (figure 3a; supplementary analyses, supplement 1) [5, 7, 27, 33].

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of clinical management outcomes associated with multidisciplinary meeting (MDM) presentation: a) tissue confirmation of diagnosis; b) clinical staging; c) clinical trial enrolment. M–H: Mantel–Haenszel.

Clinical staging

Five studies were available in 32 190 subjects evaluating likelihood of documentation of clinical stage [5, 7, 18–20]. There was an increase in availability of clinical staging for those who were discussed at MDM (OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.43–4.56; p=0.002), with substantial statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared=244.23, p<0.00001, I2=98%) (figure 3b; supplementary analyses, supplement 2).

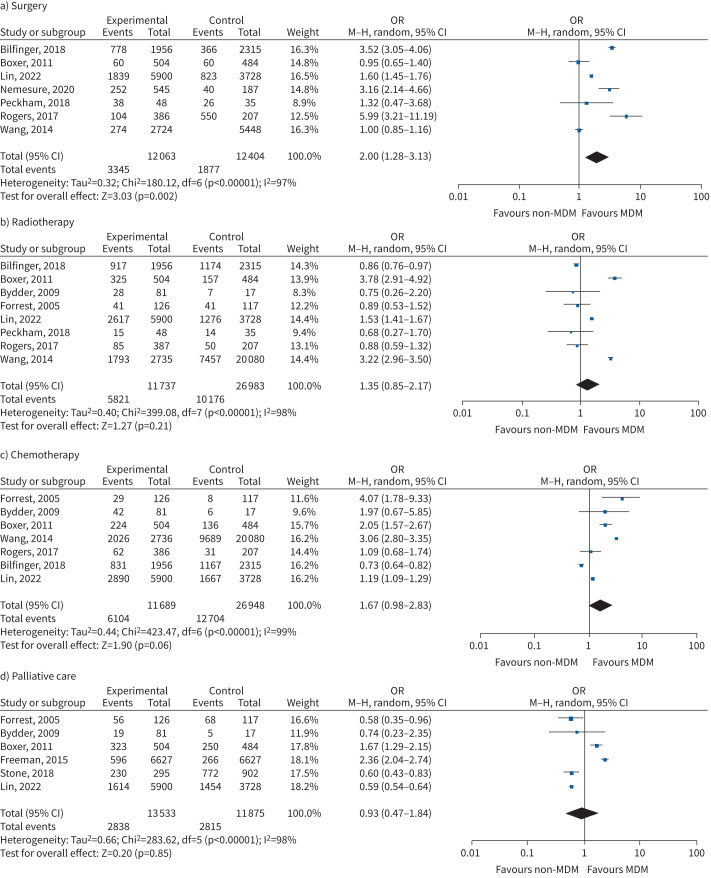

Receipt of evidence-based treatment

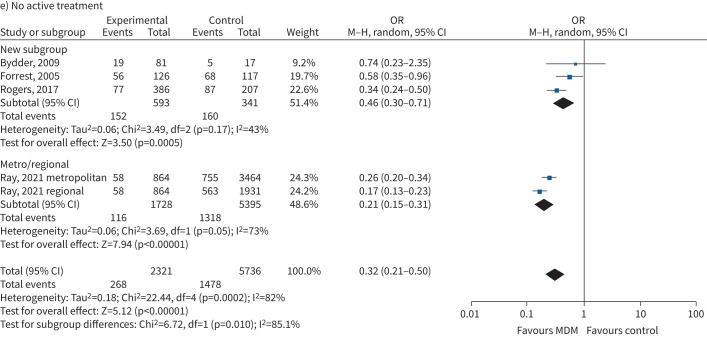

Receipt of surgery was evaluated in seven studies involving 25 779 subjects [5, 7, 21, 27, 29–31]. There was a significantly increased likelihood for MDM managed patients to undergo surgery (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.29–3.12; p=0.002), with substantial statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared=201, p<0.00001, I2=97%) (figure 4a). Eight studies in 38 720 subjects found no significant impact of MDM on receipt of radiotherapy (OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.85–2.17; p=0.21), with substantial statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared=399.08, p<0.00001, I2=98%) (figure 4b) [5, 7, 21, 23, 24, 29–31]. Seven studies on 38 637 subjects found no significant impact of MDM on receipt of chemotherapy (OR 1.67, 0.98–2.83; p=0.06), with substantial statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared=423.47, p<0.00001, I2=99%) (figure 4c) [5, 7, 21, 23, 24, 30, 31]. Six studies in 25 408 subjects found no significant impact on palliative care evaluation by MDM (0.93, 95% CI 0.47–1.84; p=0.85), with substantial statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared=283.62, p<0.00001, I2=98%) (figure 4d) [5, 7, 18, 19, 23, 24] (supplementary analyses, supplement 3). MDM evaluation was associated with a significant reduction in receiving no active treatment (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.21–0.50; p=0.01), with low statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared=22.44, p=0.0002, I2=85%), reported in four studies including 8057 subjects (figure 4e) [20, 23, 24, 30].

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of receipt of treatment outcomes associated with multidisciplinary meeting (MDM) presentation: a) surgery; b) radiotherapy; c) chemotherapy; d) palliative care; e) no active treatment. M–H: Mantel–Haenszel.

FIGURE 4.

Continued.

Clinical trial enrolment

Two studies evaluated impacts of MDM in clinical research participation, finding no significant impact (OR 2.11, 95% CI% 0.91–4.89; p=0.08), with high statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared=26.59, p<0.00001, I2=96%) (figure 3c; supplementary analyses, supplement 4) [5, 18].

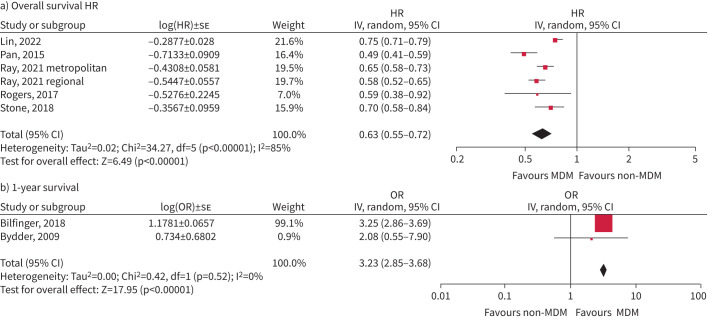

Survival

Presentation in an MDM was associated with better overall survival (using HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.55–0.72; p<0.00001), reported from five studies including 50 246 participants (I2=85%) [5, 19, 20, 28, 30], although a single-site study of 988 patients reported no significant effect (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.86–1.17) [7] (figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Survival estimates: a) overall survival; b) 1-year survival. HR: hazard ratio; IV: inverse variance; MDM: multidisciplinary meeting.

Two studies reported increased odds of 1-year survival (OR 3.23, 95% CI 2.85–3.68; p<0.00001), with minor statistical heterogeneity (Chi-squared=0.42, p=0.52, I2 0%) [21, 23].

Emergency department presentation

Wang et al. [31] reported a high emergency department burden provided by cancer patients, noting 0.9% of emergency department presentations by cancer patients, with 7.7% of cancer survivors visiting the emergency department, using some 1.4 emergency department services per year. Using a propensity score matching approach evaluating 8172 consecutive, treated, lung cancer diagnoses reduced emergency department presentation by 11% (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.80–0.98; p<0.022) compared to those not seen in the MDM [31].

Quality of life

Linford et al. [17] performed a qualitative study, interviewing patients, caregivers and physicians, exploring experiences of traditional models of care compared to multidisciplinary clinic (MDC) models. Physician participants described improved communication (attributed to real-time face-to face discussions with colleagues) and indicated that the MDC improved collegiality and collaborative relationships through a better appreciation of each other's roles and expertise. Patient participants reported enhanced convenience and efficiency, noting that concurrent appointments increased the likelihood of supporting caregiver attendance and noting a lower likelihood of being overwhelmed with information and greater consistency in physician messaging.

Bjegovich-Weidman et al. [22] reported on the development of a MDC model within a large integrated nonprofit health system. Findings included a significant reduction of time from diagnosis to definitive treatment, high patient satisfaction and increased patient retention within the clinic, a 28% increase in care delivered to patients, and improved quality of care confirmed by reduction in duplicate testing and concordance with national guidelines on work up and therapy.

Stevens et al. [34] studied management of early stage I–II NSCLC, finding that 58% of subjects were presented to an MDM, and that MDM subjects were more likely to receive curative-intent treatment and an increased likelihood of discussion of early- than late-stage disease.

Hung et al. [25] reported MDT discussion for just 39.4% of stage III subjects, observing an increase in median survival of 41.2 months for those discussed at MDT and 25.7 months for those not discussed, with increased survival likelihood also seen in those with better performance status and undergoing surgery.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that MDM presentation was associated with significant increase in the likelihood of tissue confirmation of diagnosis, documentation of clinical staging, receipt of surgery and a reduction in the likelihood of no active treatment, with nonsignificant trends to an increase in likelihood of clinical trial participation and receipt of chemotherapy. Overall survival hazard was significantly reduced for MDM-presented patients, with an increased odds ratio for 1-year survival.

Evidence-based treatment and survival

Previous studies of MDM function have suggested evidence of an increase in guideline-concordant management and potential for reduction in unwarranted practice variation [5, 35]. Pooled evidence from this study provides clear evidence of a survival benefit resulting from MDM presentation [5, 19–21, 23, 28, 30].

Organisational quality in MDM implementation

Healthcare quality assessment involves review of measures reflecting the structure, process and outcome of healthcare activities [36]. Process and outcome measures, as here reported, are highly likely to be dependent on the structural quality of the healthcare system, which describes the physical capacity, systems and organisational characteristics of the healthcare facility where care occurs [37]. In included studies there is variable reporting of structural quality, and assumptions of equivalence may be incorrect.

MDM patient evaluation is likely to be the optimum forum for management decision-making, although the implementation of these decisions may not necessarily be assumed. Recent studies identified 28–37% discordance between MDM decision-making and subsequent treatment implementation, with significantly poorer timeliness and survival outcomes associated with delivery of MDM-discordant treatment [38, 39]. These findings may imply that the measurement of treatment implementation concordance may be a useful measure and explanation for variation in process quality.

The timing of MDM presentation is not clearly reported among the included studies. Rogers et al. [30] reported 51% of patients being presented to an MDM prior to treatment, 9% receiving treatment prior to MDM presentation, 5% not being presented to an MDM until 60 days post-diagnosis and 35% not presented to an MDM. MDM presentation is likely to have impacts on management decision-making both prior to and following definitive management, including assistance with adjuvant therapy decision-making post-resection.

Opportunities for improvement in MDM function

A recent review evaluated quality of care decisions made by multidisciplinary cancer team MDTs [40]. Factors impacting decisional quality included cancer management changes by individual physicians (2–52%), failure to reach a decision at MDT discussion (27–52%), failure of implementation (1–16%), limited engagement of nursing personnel, failure of consideration of patient preferences, time pressure, excessive caseload, low attendance, poor teamwork and lack of leadership leading to lack of information and deterioration of decision-making.

A 2009 survey of multidisciplinary team function within the UK National Health Service identified team composition, infrastructure, meeting organisation and logistics, patient-centred clinical decision-making and team governance as key domains of effective MDM function [41]. Despite this address to organisational process, a 2020 audit of lung cancer MDT function provided 10 challenging stage III cases with identical information to 11 different MDTs and identified substantial functional differences in outcomes in terms of agreement in TNM staging and treatment recommendations [42]. Systematic review of MDM quality-assessment tools reports variable coverage of the key domains of MDM function, finding little evidence of engagement for quality improvement [43].

While MDM has been broadly shown to increase the delivery of desirable guideline-recommended treatments to lung cancer patients, there are a number of other potential benefits, outside formal guidelines, which are not well described in the literature. Such benefits may include increased management efficiency, optimised patient–healthcare provider interactions, reduced consultation visits and duration, reduced inappropriate treatment (such as substitution of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for resection in marginal operable cases), treatment plan optimisation, enhanced precision medicine outcomes, enhanced treatment plan communication, improved quality of life, improvements in patient and provider perceived healthcare value in addition to potential health economic benefits.

The benefits of MDM presentation are relatively well described in lung cancer (NSCLC and SCLC); however, there is scope to utilise MDM function to provide similar benefit in other thoracic cancers including thymoma, carcinoid tumours, neuroendocrine tumours and mesothelioma.

Study clinical heterogeneity

There was variation in included study participants reporting early stage I–II cohorts [34], locally advanced stage III [25], all-stage patients and inoperable lung cancer [23, 24]. Study reports included single institution reports [23, 29, 32], hospital networks [7, 20, 22, 27, 34], Veterans Affairs medical centres [26], state-based cancer registries [5, 33] and large national population registries [28]. MDM exposure included presentation to scheduled formal MDM [5, 7, 18–21, 23, 25, 26, 29, 30, 32, 33], and multidisciplinary care programmes [22, 24, 27, 28, 31], although timing of MDM presentation was not routinely specified. Study designs included evaluation before and after the implementation of multidisciplinary case meetings [22, 29, 32], contemporaneous cohorts retrospectively identified as MDM presented or nonpresented cohorts [5, 7, 17, 19, 21, 27], using landmark analysis [31] and propensity score matching of MDM presented/nonpresented [31]. Heterogeneity between observational studies is expected. We therefore planned to explore differences between studies through subgroup analyses by study design, by participants or by intervention type, which did not fully explain heterogeneity.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first substantive meta-analysis of management, treatment and survival outcomes in large populations of NSCLC patients treated in multiple national jurisdictions. While most studies described similar approaches in participation, conduct and timing of MDM meetings, it is likely that there was a degree of variation between process and outcomes of these meetings at participating centres, representing potential unwarranted variation in the intervention. The timing of exposure to the MDM process is not clearly reported and these factors may impact effective utilisation of neo-adjuvant and adjuvant therapies and become increasingly important in the modern era of immunotherapy and targeted therapies in early-stage disease [44].

Implications for practice, policy and future research

There remains a paucity of data available to describe MDM process, consensus strategies, evidence utilisation and adherence and audit outcomes in the implementation of MDM practice [45]. The literature evidence in multidisciplinary care function remains challenged by a wealth of observational study data and a paucity of prospective randomised trial evidence. There remains a lack of clarity in definitions of multidisciplinary care and process, and an absence of multidisciplinary care implementation strategies [46].

Points for clinical practice

• MDM presentation is a relatively low-cost intervention that improves histological confirmation, clinical staging, receipt of treatment and survival.

Questions for future research

• The determinants of MDM presentation are not well known.

• MDM presentation may have an important impact on cancer burden, improve equity and reduce unwarranted clinical variation in care.

Conclusion

The literature provides extensive evidence of benefit of MDM presentation, and yet substantial rates of nonpresentation exist with a lack of clarity of reasons for nonpresentation. Equity of access remains a significant concern, with clear evidence that certain populations may be underpresented, including the aged, those with stage IV disease, those living in nonmetropolitan centres and those treated in private healthcare systems.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary table S1 ERR-0157-2023.table_S1 (34.5KB, pdf)

Supplementary analyses: outcomes by subgroup ERR-0157-2023.supplementary_analyses (247.9KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Conflict of interest: All authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Guirado M, Sanchez-Hernandez A, Pijuan L, et al. Quality indicators and excellence requirements for a multidisciplinary lung cancer tumor board by the Spanish Lung Cancer Group. Clin Transl Oncol 2022; 24: 446–459. doi: 10.1007/s12094-021-02712-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2022; 20: 497–530. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Postmus PE, Kerr KM, Oudkerk M, et al. Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: Suppl. 4, iv1–iv21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2019; 30: 863–870. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin T, Pham J, Paul E, et al. Impacts of lung cancer multidisciplinary meeting presentation: drivers and outcomes from a population registry retrospective cohort study. Lung Cancer 2022; 163: 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleissig A, Jenkins V, Catt S, et al. Multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: are they effective in the UK? Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 935–943. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70940-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boxer MM, Vinod SK, Shafiq J, et al. Do multidisciplinary team meetings make a difference in the management of lung cancer? Cancer 2011; 117: 5112–5120. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman RK, Van Woerkom JM, Vyverberg A, et al. The effect of a multidisciplinary thoracic malignancy conference on the treatment of patients with lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010; 38: 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau KK, Rathinam S, Waller DA, et al. The effects of increased provision of thoracic surgical specialists on the variation in lung cancer resection rate in England. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8: 68–72. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182762315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt HM, Roberts JM, Bodnar AM, et al. Thoracic multidisciplinary tumor board routinely impacts therapeutic plans in patients with lung and esophageal cancer: a prospective cohort study. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 99: 1719–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kehl KL, Landrum MB, Kahn KL, et al. Tumor board participation among physicians caring for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Oncol Pract 2015; 11: e267–e278. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.003673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou J, Xu X, Wang D, et al. [The impacts of the multidisciplinary team model on the length of stay and hospital expenses of patients with lung cancer]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2015; 38: 370–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroki L, Stuckey A, Hirway P, et al. Addressing clinical trials: can the multidisciplinary tumor board improve participation? A study from an academic women's cancer program. Gynecol Oncol 2010; 116: 295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fennell ML, Das IP, Clauser S, et al. The organization of multidisciplinary care teams: modeling internal and external influences on cancer care quality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010; 2010: 72–80. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016; 355: i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): an R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Synth Methods 2020; 12: 55–61. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linford G, Egan R, Coderre-Ball A, et al. Patient and physician perceptions of lung cancer care in a multidisciplinary clinic model. Curr Oncol 2020; 27: e9–e19. doi: 10.3747/co.27.5499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman RK, Ascioti AJ, Dake M, et al. The effects of a multidisciplinary care conference on the quality and cost of care for lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 100: 1834–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stone E, Rankin N, Kerr S, et al. Does presentation at multidisciplinary team meetings improve lung cancer survival? Findings from a consecutive cohort study. Lung Cancer 2018; 124: 199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray MA, Faris NR, Fehnel C, et al. Survival impact of an enhanced multidisciplinary thoracic oncology conference in a regional community health care system. JTO Clin Res Rep 2021; 2: 100203. doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bilfinger TV, Albano D, Perwaiz M, et al. Survival outcomes among lung cancer patients treated using a multidisciplinary team approach. Clin Lung Cancer 2018; 19: 346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bjegovich-Weidman M, Haid M, Kumar S, et al. Establishing a community-based lung cancer multidisciplinary clinic as part of a large integrated health care system: Aurora Health Care. J Oncol Pract 2010; 6: e27–e30. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bydder S, Nowak A, Marion K, et al. The impact of case discussion at a multidisciplinary team meeting on the treatment and survival of patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Intern Med J 2009; 39: 838–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02019.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, et al. An evaluation of the impact of a multidisciplinary team, in a single centre, on treatment and survival in patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2005; 93: 977–978. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung HY, Tseng YH, Chao HS, et al. Multidisciplinary team discussion results in survival benefit for patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0236503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Tumor boards and the quality of cancer care. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105: 113–121. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nemesure B, Albano D, Bilfinger T. Lung cancer recurrence and mortality outcomes over a 10-year period using a multidisciplinary team approach. Cancer Epidemiol 2020; 68: 101804. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2020.101804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan CC, Kung PT, Wang YH, et al. Effects of multidisciplinary team care on the survival of patients with different stages of non-small cell lung cancer: a national cohort study. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0126547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peckham J, Mott-Coles S. Interprofessional lung cancer tumor board: the role of the oncology nurse navigator in improving adherence to national guidelines and streamlining patient care. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2018; 22: 656–662. doi: 10.1188/18.CJON.656-662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogers MJ, Matheson L, Garrard B, et al. Comparison of outcomes for cancer patients discussed and not discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting. Public Health 2017; 149: 74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang SM, Kung PT, Wang YH, et al. Effects of multidisciplinary team care on utilization of emergency care for patients with lung cancer. Am J Manag Care 2014; 20: e353–e364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamburini N, Maniscalco P, Mazzara S, et al. Multidisciplinary management improves survival at 1 year after surgical treatment for non-small-cell lung cancer: a propensity score-matched study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2018; 53: 1199–1204. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell PL, Thursfield VJ, Ball DL, et al. Lung cancer in Victoria: are we making progress? Med J Aust 2013; 199: 674–679. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens W, Stevens G, Kolbe J, et al. Management of stages I and II non-small-cell lung cancer in a New Zealand study: divergence from international practice and recommendations. Intern Med J 2008; 38: 758–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01523.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vinod SK, Sidhom MA, Delaney GP. Do multidisciplinary meetings follow guideline-based care? J Oncol Pract 2010; 6: 276–281. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q 2005; 83: 691–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kunkel S, Rosenqvist U, Westerling R. The structure of quality systems is important to the process and outcome, an empirical study of 386 hospital departments in Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res 2007; 7: 104. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osarogiagbon RU, Phelps G, McFarlane J, et al. Causes and consequences of deviation from multidisciplinary care in thoracic oncology. J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6: 510–516. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820b88a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ung KA, Campbell BA, Duplan D, et al. Impact of the lung oncology multidisciplinary team meetings on the management of patients with cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2016; 12: e298–e304. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamb BW, Brown KF, Nagpal K, et al. Quality of care management decisions by multidisciplinary cancer teams: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18: 2116–2125. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1675-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.NHS National Cancer Action Team . The Characteristics of an Effective Multidisciplinary Team (MDT). London, National Cancer Action Team, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoeijmakers F, Heineman DJ, Daniels JM, et al. Variation between multidisciplinary tumor boards in clinical staging and treatment recommendations for patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chest 2020; 158: 2675–2687. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown GTF, Bekker HL, Young AL. Quality and efficacy of multidisciplinary team (MDT) quality assessment tools and discussion checklists: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 2022; 22: 286. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09369-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shukla N, Hanna N. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant immunotherapy in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2021; 12: 51–60. doi: 10.2147/LCTT.S277717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rankin NM, Lai M, Miller D, et al. Cancer multidisciplinary team meetings in practice: results from a multi-institutional quantitative survey and implications for policy change. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2018; 14: 74–83. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Osarogiagbon RU. Making the evidentiary case for universal multidisciplinary thoracic oncologic care. Clin Lung Cancer 2018; 19: 294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary table S1 ERR-0157-2023.table_S1 (34.5KB, pdf)

Supplementary analyses: outcomes by subgroup ERR-0157-2023.supplementary_analyses (247.9KB, pdf)