Abstract

With the emergence of large-scale sequencing data1,2, methods for improving power in rare variant analyses (RVAT)3–5 are needed. Here, we show that adjusting for common variant polygenic scores (PGS) improves the yield in gene-based RVAT across 65 quantitative traits in the UK Biobank (up to 20% increase at α=2.6×10−6), without marked increases in false-positive rates or genomic inflation. Benefits were seen for various models, with the largest improvements seen for efficient sparse mixed-effects models. Our results illustrate how PGS-adjustment can efficiently improve power in rare variant association discovery.

In recent years, large-scale biorepositories have seen an explosion in available high-depth sequencing data1,2, and investigators have increasingly leveraged gene-based tests to identify rare variants contributing to human phenotypic variability3–5. An important direction in the genetics field is to identify methods for improved power in rare variant association analyses (RVAT). Many quantitative traits have considerable heritability from common variants.6 Given known power benefits for inclusion of known covariates in linear models7–9, we hypothesized that adjusting for polygenic scores (PGS), which summarize common variant effects, would efficiently improve power in RVAT.

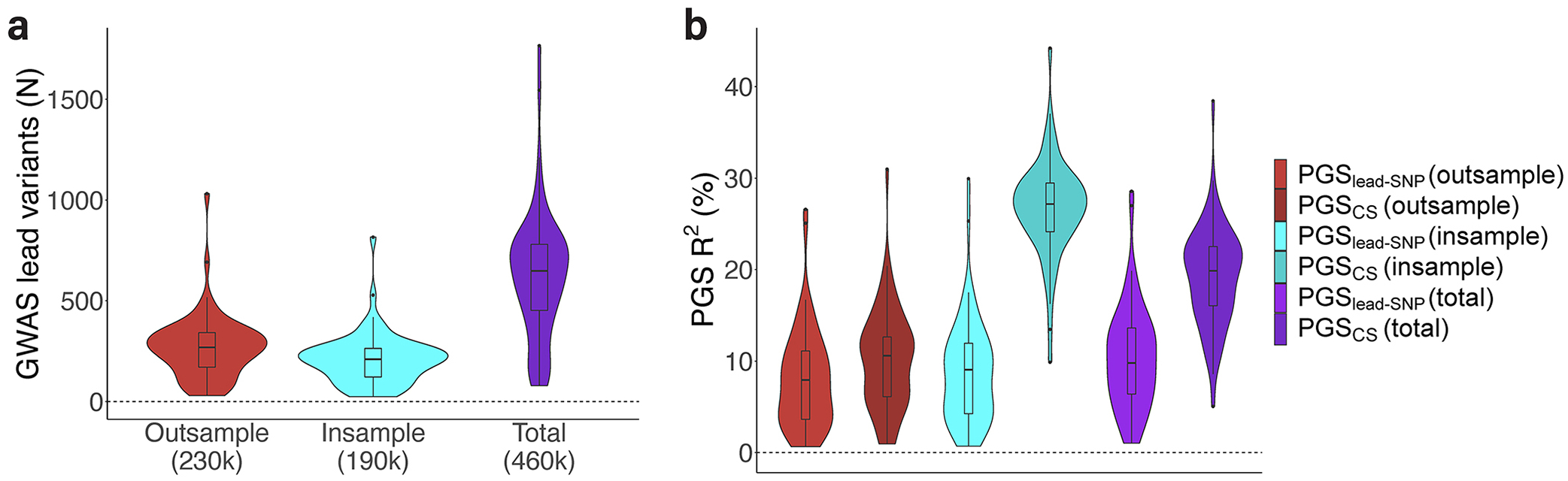

We leveraged the UK Biobank dataset, which contains imputed data on nearly 500,000 individuals10 as well as exome sequencing for over 200,000 individuals2. We first performed genome-wide association analyses (GWAS) for common variants (MAF≥1%) across 65 quantitative traits (Supplementary Table 1). We performed three types of GWAS, namely an out-of-sample GWAS within European samples who were not included in the exome sequencing subset (N=230k), an in-sample GWAS within European samples who were also exome sequenced (N=190k), and a ‘total’ GWAS within all European UK Biobank participants (N=460k) (Figure 1). All traits had multiple independent genome-wide significant (P<5×10−8) common variant hits (Extended Data Figure 1a, Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1: Analysis Flowchart.

For common variant analyses across 65 quantitative traits, we performed GWAS among UK Biobank samples who were unrelated from individuals with whole-exome sequencing (WES) data (‘out-sample’), GWAS among UK Biobank samples with WES data (‘in-sample’), and GWAS among all UK Biobank samples (‘total’). From each GWAS, we constructed PGS using clumping-and-thresholding methods and using PRS-CS (described in Ge et al. 2019; ref.11). We then performed exome-wide testing of rare variants within the WES samples, using models without PGS and adjusting for various PGS. LOF and missense variants were used to assess rare variant yields, while synonymous variants were used to assess inflation and false-positive rates. In the flowchart, blue boxes describe steps revolving around common variant analyses and PGS construction, while the red boxes highlight steps involving rare variant analyses. Note: λ, inflation factor computed as observed χ2 at the median over the expected under the null hypothesis.

Using the GWAS summary statistics, we then constructed PGS based on two methods, namely ‘lead-SNP’ PGS (P<5×10−8 and r2<0.001), and genome-wide PGS using PRScs-auto11 (Methods, Figure 1). Thus, we analyzed six PGS per trait: PGSlead-SNP (out-sample), PGSCS (out-sample), PGSlead-SNP (in-sample), PGSCS (in-sample), PGSlead-SNP (total) and PGSCS (total). All types of PGS explained variance for their respective traits (Extended Data Figure 1b, Supplementary Table 2).

We then performed exome-wide gene-based collapsing RVAT within the exome sequenced samples, focusing on ultra-rare loss-of-function (LOF) and missense variants with MAC<40 (Methods, Figure 1). We ran RVAT models with no PGS included, as well as RVAT models adjusting for each type of PGS. We used an efficient sparse mixed-effects model to account for relatedness.

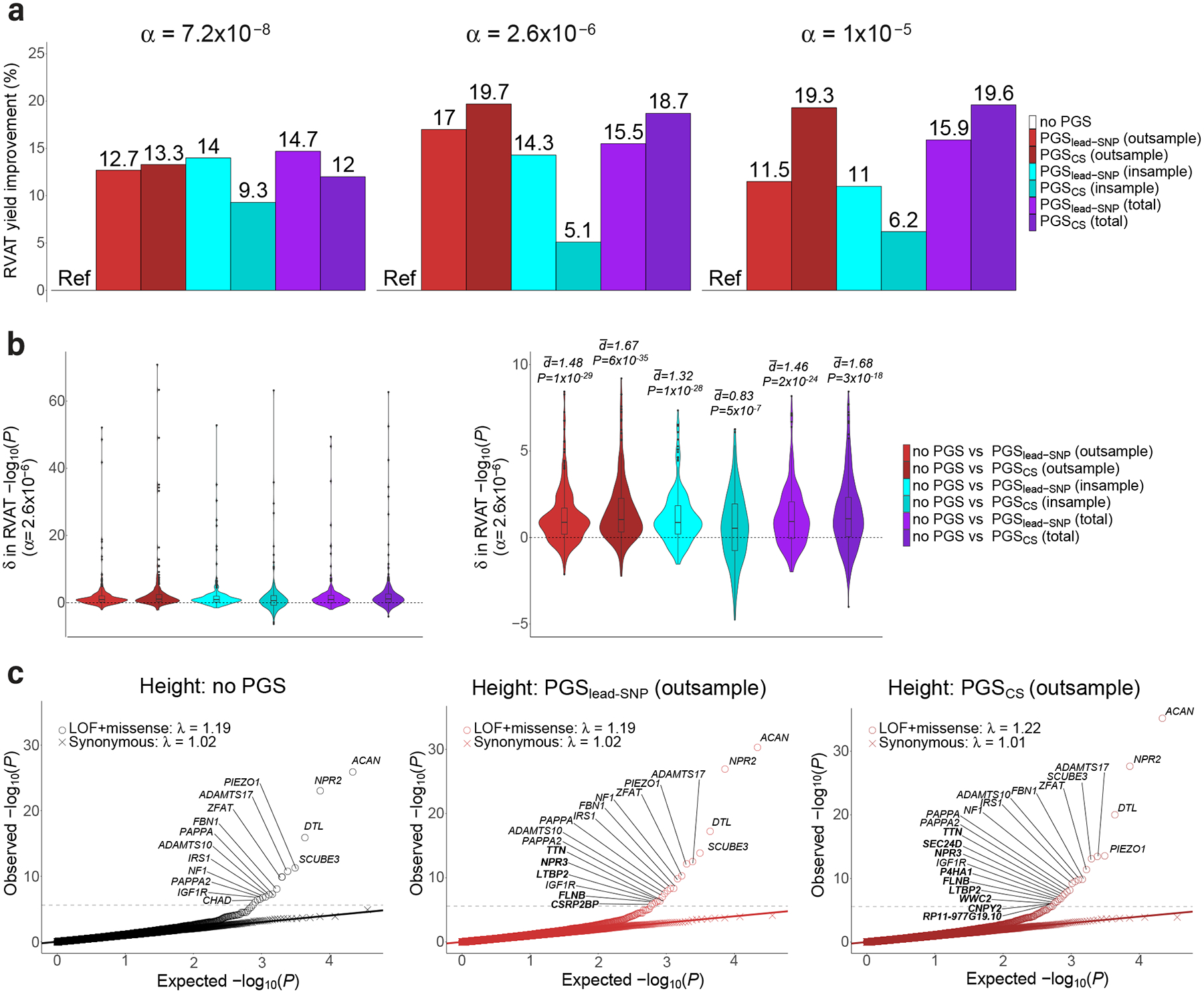

All six PGS-adjusted models showed higher numbers of RVAT gene-phenotype associations at various significance cutoffs, compared to the model without a PGS (Figure 2a, Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Tables 3–4). PGSCS (out-sample) generally yielded more total associations than PGSlead-SNP (out-sample). The PGSCS (out-sample) model yielded 13.3% and 19.7% more significant associations at Bonferroni-corrected significance (α=7.2×10−8; 170 vs 150 associations), and conventional exome-wide significance (α=2.6×10−6; 261 vs 218 associations), respectively.

Figure 2: PGS adjustment improves discovery yield in analysis of rare deleterious variants.

Part a: Bar charts for the improvement in deleterious RVAT yield after PGS-adjustment at different alpha levels, expressed in percentage relative to the no PGS model. Part b: Violin plots for the difference (δ) in significance of tests from deleterious RVAT, comparing models with PGS vs models without PGS. Here, the δ in P-values (on the -log10 scale) are displayed for tests reaching P<2.6×10−6 (Methods). The P-values and distributions are derived from two-sided paired Wilcoxon signed rank tests (where N gene-trait pairs equals 263, 270, 258, 260, 265 and 278 from left to right), while the d values plotted above the violins are derived from two-sided paired T-tests (after removing outliers). The left plot shows all results, while the right plot is capped at y=10 for clarity. Boxplots: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Part c: Quantile-quantile plots for PGS-adjusted RVAT of the phenotype height. The left plot shows expected vs observed P-values for the model with no PGS-adjustment, while the second and third plots show results for PGSleadSNP (out-sample) and PGSCS (out-sample), respectively. Exome-wide significant genes are annotated with gene names; genes highlighted in bold were only identified after PGS-adjustment. Note: , estimated paired group difference; δ, difference; α, significance cutoff; λ, inflation factor computed as observed χ2 at the median over the expected under the null hypothesis.

PGSlead-SNP (in-sample) performed similarly to PGSlead-SNP (out-sample), while PGSCS (in-sample) generally performed the least well (Figure 2a).

At various significance thresholds, PGS-adjusted models significantly improved the P-values for top gene-phenotype associations, as compared to the model without PGS (Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 5). For example, the PGSCS (out-sample) adjusted model was associated with significantly higher -log10(P) values, for associations reaching conventional exome-wide significance (P=6×10−35, paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test) (Figure 2B; Supplementary Table 5).

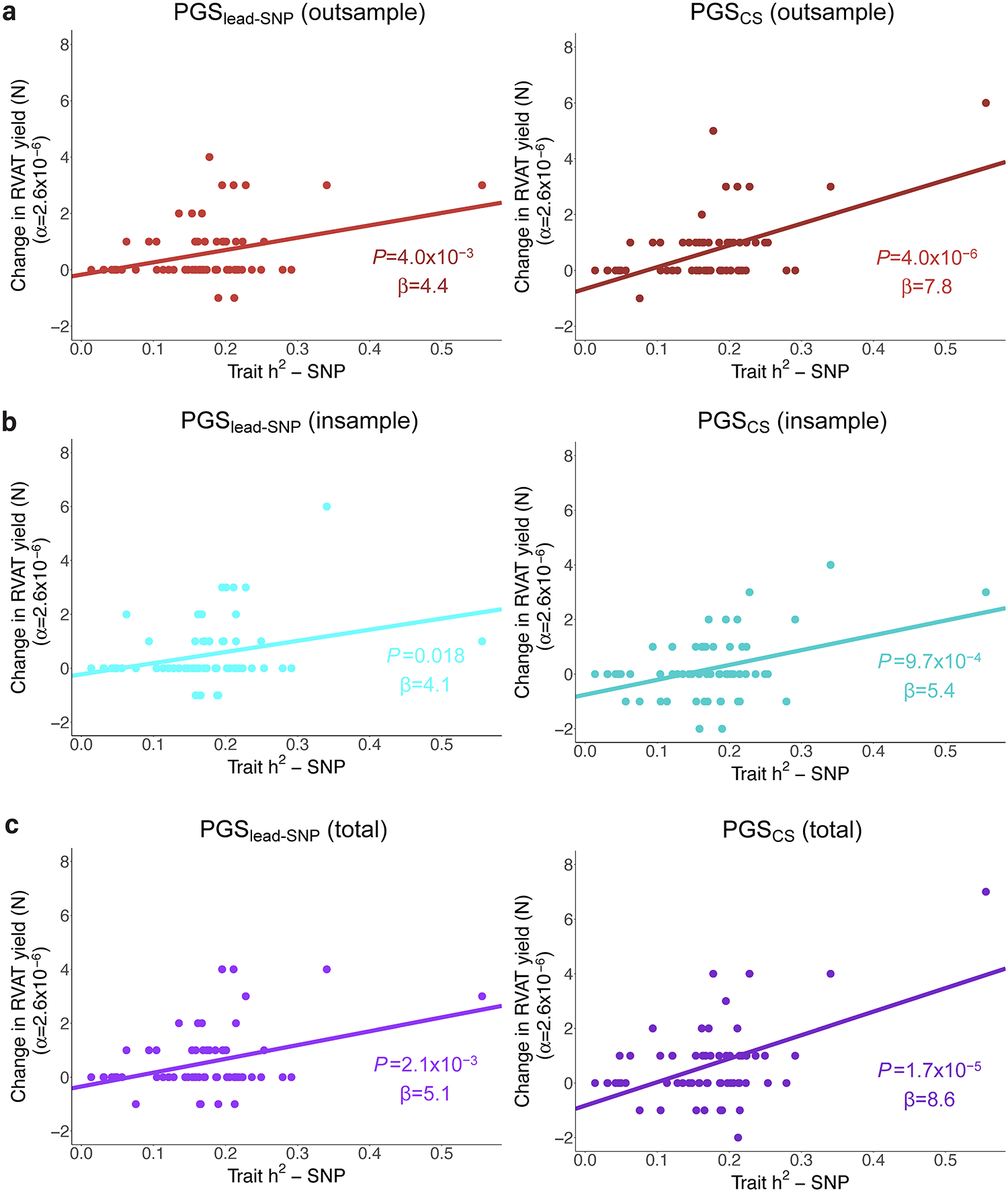

Many of the gene-phenotype associations that became significant after PGS-adjustment were biologically-plausible findings (Supplementary Note, Supplementary Table 6). As an example, for the phenotype height such associations included NPR3, LTBP2, P4HA1, FLNB, SEC24D and TTN (Figure 2c, Supplementary Note, Supplementary Figure 3). We further confirmed power improvements for positive control associations5 (Supplementary Note, Extended Data Figure 2). We found that h2SNP and PGS R2 were both significantly associated with the per-trait improvement in number of significant associations after PGS-adjustment, particularly for PGSCS models (Extended Data Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 4).

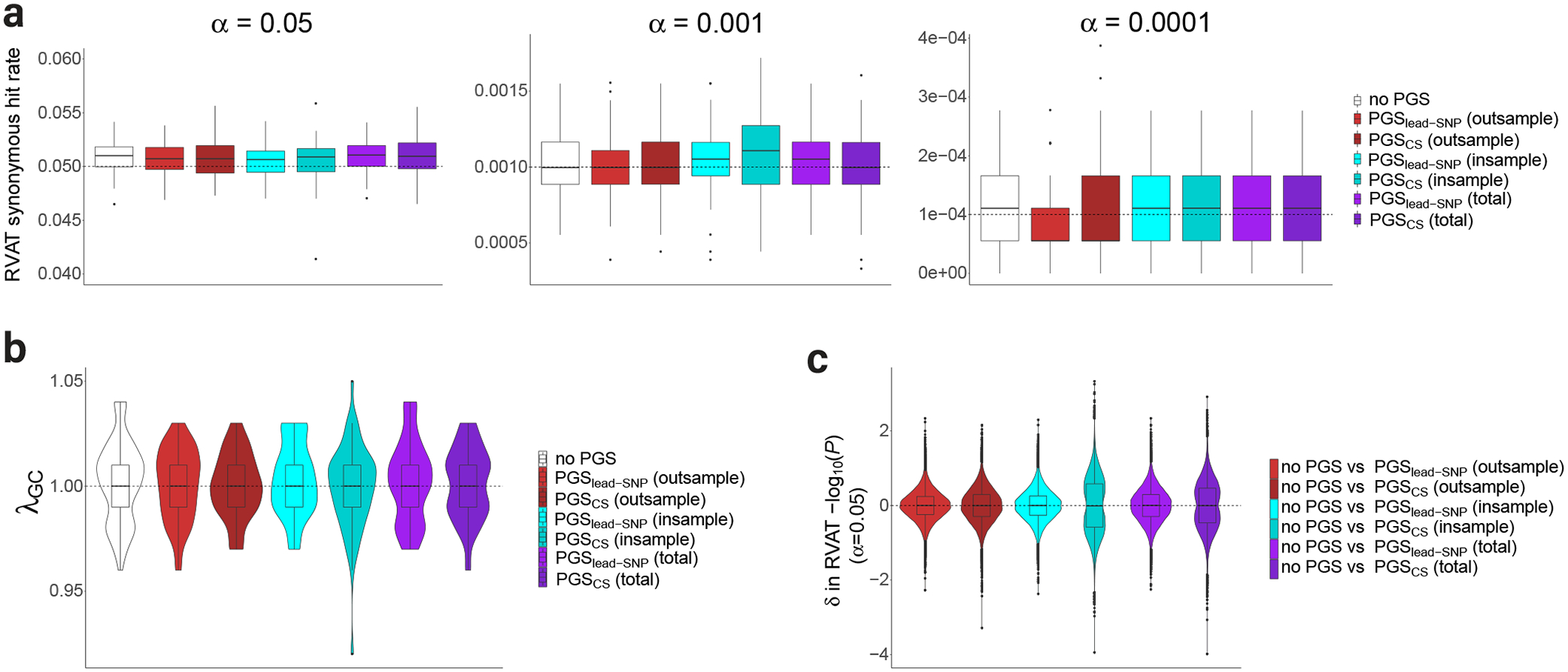

To assess genomic inflation and false-positive rates, we then performed exome-wide RVAT analyzing synonymous variants with MAC<40. At liberal α cutoffs, we observed association rates that were marginally higher or equivalent to the expectation under the null (Figure 3a, Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 7). At Bonferroni-corrected significance (α=4.3×10−8), we observed more hits than expected under the null (Supplementary Tables 8–9). We found that all these associations involved IGLL5 and white blood cell traits (Supplementary Table 10), possibly reflecting true association12. After removing IGLL5 from the analysis, synonymous association rates were well controlled at stringent α values (Supplementary Table 7).

Figure 3: PGS adjustment does not increase false-positive rates or genomic inflation in the analysis of rare synonymous variants.

Part a: Boxplots for per-trait association rate from synonymous RVAT at different alpha levels across the 65 traits. Per trait, a median of 18,060 genes were analyzed. Part b: Violin plots for genomic inflation factors for exome-wide RVAT of synonymous variants across the 65 traits. Part c: Violin plots for difference (δ) in significance of tests from synonymous variant RVAT, comparing models with PGS vs models without PGS. Here, the δ in P-values (on the -log10 scale) are displayed for tests reaching P<0.05 (Methods), with the contributing N gene-trait pairs equaling 75044, 77524, 75838, 89792, 77784 and 85187 (from left to right). Boxplots: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Note: δ, difference; α, significance cutoff; λ, inflation factor computed as observed χ2 at the median over the expected under the null hypothesis.

Importantly we did not observe a clear pattern where synonymous association rates were strongly increased after PGS adjustment. Using paired Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, we found no significant increase in -log10(P) values for the synonymous RVAT at various α levels, across the different types of PGS adjusted models (P>0.05 for all tests by paired Wilcoxon rank test; Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 11). For example, at the α=0.05 level, estimated differences between models with PGS vs without PGS centered around 0 (Figure 3c, Supplementary Table 11). Furthermore, in synonymous RVAT, per-trait λGC values did not increase after PGS adjustment across PGS types (Supplementary Figure 5, Supplementary Tables 12–13). All per-trait synonymous λGC values were within acceptable limits at λGC<1.05 (Figure 3b), and test statistics were not inflated visually (Supplementary Figure 6).

In secondary analyses, we found that RVAT at more lenient frequency thresholds (MAF<0.1%) also benefitted strongly from PGS adjustment (Supplementary Note, Extended Data Figure 4). We further found that leave-one-chromosome-out PGS performed similarly to all-chromosome-PGS (Supplementary Note, Extended Data Figure 5). In an analysis of 7 binary traits, we found minimal to no benefit for PGS-adjustment in logistic mixed-models (Supplementary Note, Supplementary Tables 14–15). When assessing other RVAT software, we found that PGS-adjustment improved power in standard linear regression models, and in burden testing using fastGWA (refs.13,14) (Supplementary Note, Extended Data Figure 6, Supplementary Table 16). PGS adjustment also had power benefit in BOLT-LMM (ref.15), where it also sped up model convergence (Supplementary Note, Extended Data Figure 7). PGS adjustment further showed power benefits for SKAT-O testing in speed-optimized SAIGE-GENE+ models (ref.16) (Extended Data Figure 8, Supplementary Table 16), although no power benefit was noted for whole-genome ridge regression models from REGENIE (ref.17) (Supplementary Note, Extended Data Figure 9).

In conclusion, we find that adjustment for common variant PGS can improve the yield in gene-based RVAT of quantitative traits, without markedly increasing false-positive rates and genomic inflation, consistent with recent findings for common variant analysis9,17. While our approach benefitted various RVAT models, our data show that PGS-adjustment is particularly useful when utilizing efficient sparse mixed-models (as implemented in STAAR, SAIGE-GENE+ and fastGWA) or when using simple linear models. Sparse mixed-models paired with PGS-adjustment may therefore offer an efficient and powerful alternative to computationally-intensive dense mixed-model approaches. Furthermore, PGSs derived from large external data may improve power in small sequencing studies, where polygenic effects may not be accurately derived internally.

The observed power increase likely reflects true biological variance being absorbed by PGS. Indeed, the genome-wide PGSCS performed better than PGSlead-SNP for out-of-sample GWAS data, with SNP-heritability and PGS R2 being strong positive predictors of yield improvement. We note that for in-sample GWAS, PGSCS did not perform as well as other PGS, likely owing to overfitting of this genome-wide model. We therefore recommend using lead-SNP scores or large out-of-sample GWAS data when available, or using cross-validation approaches such as those used in REGENIE (ref.17). Finally, our analysis was focused on testing of rare variants (MAF<0.1%). For gene-based analyses that include low-frequency variants (0.1<MAF<1%), leave-one-chromosome-out PGS may be useful (Supplementary Note) if investigators want to avoid linkage disequilibrium between PGS variants and tested variants.

In sum, we show how adjusting for common variant effects can aid in rare variant association discovery. Our approach can be applied to efficiently enhance discovery yield in future rare variant analyses.

Methods

Study population

The UK Biobank is a large population-based prospective cohort study from the United Kingdom with rich phenotypic and genetic data on 500,000 individuals aged 40–69 at enrollment18. Available genetic data currently includes genome-wide imputed data for almost all participants10, as well as whole exome sequencing data on approximately 200,000 individuals2. The UK Biobank resource was approved by the UK Biobank Research Ethics Committee and all participants provided written informed consent to participate. Use of UK Biobank data was performed under application number 17488 and was approved by the local Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Phenotypes

In the present study, we analyzed 65 quantitative traits, including anthropometric traits, metabolic blood markers, blood pressure traits, and a variety of blood count traits. Details and the number of samples for each trait per analysis are presented in Supplementary Table 1. All raw phenotypes were adjusted for lipid-lowering medication use (Supplementary Note), and were subsequently rank-based inverse normalized to ensure normality before analyses.

Genetic datasets

We utilized both genome-wide imputed data and whole exome sequencing data in the present study. Specifically, all common variant analyses were performed using genome-wide imputed data10. Briefly, genotyping was performed using Affymetrix UK Biobank Axiom (450,000 samples) and Affymetrix UK BiLEVE axiom (50,000 samples) arrays. Subsequently, the genetic data were imputed to the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel and UK10K + 1000 Genomes panels. We removed any samples that had withdrawn their consent, samples that were outliers for heterozygosity or missingness, individuals with putative sex chromosome aneuploidy, and individuals with a mismatch between self-reported and genetically inferred sex. We then removed all individuals who were determined to not be of homogeneous European ancestry (Supplementary Note). To ensure we analyzed only high-quality common imputed variants, we removed imputed variants with minor allele frequency (MAF) <1% and INFO <0.3.

For all rare variant analyses, we utilized the whole exome sequencing data, which were available for 200,642 individuals2. The revised version of the IDT xGen Exome Research Panel v1.0 was used to capture exomes with over 20X coverage at 95% of sites. Variants were subsequently called per-sample using DeepVariant and combined using GLNexus (ref.19). We utilized the quality-control procedures described previously in Jurgens et al.4 In short, we set low-quality genotypes to missing, after which we removed variants based on call rate (<90%), Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test (P < 1×10−15), presence in low-complexity regions, and minor allele count (≥1). Sample-level quality-control consisted of removal of samples that had withdrawn their consent, were duplicates, had a mismatch between sequencing and genotyping array data, had a mismatch between genetically inferred and self-reported sex, had low call rates or were outliers for a number of additional metrics (Jurgens et al.4). We finally restricted the exome cohort to individuals who also had imputed data available and were of European ancestry, leaving 188,062 samples.

Common variant association analyses

We first performed three genome-wide association analyses (GWAS) for each included trait using genome-wide imputed data (Figure 1). These included an out-of-sample GWAS within European samples who were independent of the exome cohort (not included in the exome cohort and unrelated to the exome cohort); an in-sample GWAS within the exome sequenced samples; and a total GWAS including all European individuals with imputed data. To perform the GWAS, we used linear whole-genome ridge regression models implemented in REGENIE (ref.17), adjusting for sex, age, age2, genotyping array and ancestral principal components 1 through 20. REGENIE produces results similar to linear mixed models in the presence of genetic relatedness17.

Polygenic score derivation

Using each of the GWAS summary results, we constructed polygenic scores (PGS) for each trait based on two differing methods20. We first constructed ‘lead SNP’ PGSs based only on independent (r2<0.001) genome-wide significant (P<5×10−8) variants. We also used PRS-CS-auto11 to construct genome-wide PGSs including millions of genetic variants (restricting to ~1.1 million HapMap variants). In brief, PRS-CS-auto applies a Bayesian regression framework to identify posterior variant effect sizes based on a continuous shrinkage prior, which is directly learnt from the data11. For both methods, the European ancestry subset of the UK Biobank dataset was used as a linkage-disequilibrium reference panel. In sum, two PGS were constructed for each trait based on out-sample GWAS data (PGSleadSNP [out-sample] and PGSCS [out-sample]), two PGS were constructed based on in-sample GWAS data (PGSleadSNP [in-sample] and PGSCS [in-sample]) and two PGS were constructed based on total GWAS data (PGSleadSNP [total] and PGSCS [total]).

Variance explained by PGS

We calculated the phenotypic variance explained by each PGS for each trait in the nullmodel. We did this by running ordinary linear regression for each trait among the unrelated subset of individuals with exome sequencing data, adjusting for the same fixed effects as described above for the rare variant analysis. R2 values were extracted from the model without PGS and from models with PGS added as a covariate. The variance explained by PGS for a given trait was defined as the improvement in R2 in the model with PGS as compared to the model with no PGS.

Rare variant association analyses

We used the whole exome sequencing data to run gene-based rare variant collapsing tests across the exome for each trait. We grouped and analyzed loss-of-function (LOF) and predicted-deleterious missense variants per gene (Supplementary Note). To minimize linkage-disequilibrium between common and rare variants, we only included variants with minor allele count (MAC) ≤40, which also had MAF<0.1% in each continental population in gnomAD version 2 exomes21. We utilized linear mixed models implemented in GENESIS22, adjusting for sex, age, age2, genotyping array, sequencing batch, ancestral principal components 1 through 20, and a sparse kinship matrix4. We subsequently repeated these analyses for each of the PGS, by adding the PGS to the model as an additional fixed-effect covariate. In cases where fitting of the mixed model failed, we reran models within unrelated individuals (Supplementary Table 1). Sample sizes for the rare variant analyses ranged from N=142,709 to N=187,890 (Supplementary Table 1). Only results for tests with ≥20 rare variant carriers were kept.

Assessment of rare variant discovery yield

We then evaluated the rare variant discovery power for models without PGS and those adjusted for PGS. We calculated the yield in number of gene associations for each model across all traits at various significance thresholds, including Bonferroni-corrected significance at α = 0.05/ (65 traits x ~10,743 genes) = 7.2×10−8, and at conventional exome-wide significance at α = 2.6×10−6. We then tested whether the addition of the PGS improved the significance of gene-phenotype associations. We used two-sided paired Wilcoxon signed rank tests to assess the improvement in -log10(P) values between two models, including gene-phenotype associations at various significance cutoffs (7.2×10−8, 2.6×10−6, 1×10−5, 1×10−4, 1×10−3, 0.05). For a given comparison between two models, we included any gene-phenotype pair reaching the cutoff in either model. To quantify the difference, , in -log10(P) values, we repeated this analysis using paired T-tests. For paired T-tests, we removed any gene-phenotype pair for which the difference between both models fell outside of 4 standard deviations from the mean of differences. The significance threshold was determined at α = 0.05 / (6 cutoffs x 6 model comparisons) = 0.0014.

Secondary analyses of discovery power

We further performed analyses where we performed exome-wide gene-based tests including rare variants at more common frequency thresholds, described in the Supplementary Note. We also assessed the power change for PGS-adjustment across a range of binary traits (Supplementary Note). To assess how PGS-adjustment affects discovery power in other RVAT software, we evaluated adding PGS to collapsing tests in standard linear regression, as well as adding PGS to burden tests in fastGWA (ref.13,14), collapsing tests in BOLT-LMM (ref.15) and SKAT-O tests in speed-optimized SAIGE-GENE+ models (ref.16,23). (Supplementary Note). We also assessed how addition of external PGS affected power in REGENIE, a recently proposed whole-genome ridge regression model that accounts for the polygenic effect using a fixed-effect variable similar to a PGS17 (Supplementary Note). Finally, we assessed a Leave-One-Chromosome-Out (LOCO) PGS and compared it to the full-PGSCS for two traits, height and LDL cholesterol, to evaluate whether the power improvement was due mainly to proximal or distal common variants (Supplementary Note).

Associations between trait heritability and PGS variance explained with yield improvement

We then assessed whether the improvement in RVAT associations after PGS-adjustment was associated with trait heritability or the variance explained by PGS. We used Linkage-Disequilibrium Score Regression24 to estimate SNP-heritability (h2SNP) for each of the 65 traits, using the total sample GWAS results and using the baselineLD_2.2 file from the LDSC software as the linkage-disequilibrium reference. We then used ordinary linear regression to regress the change in number of trait RVAT associations on the estimated h2SNP. Similarly, we used linear regression to regress the change in number of trait RVAT associations on the R2 of the PGS for its respective traits.

Assessment of false-positive rate using rare synonymous variation

To assess the false-positive error rate of our approach, we analyzed rare synonymous variation. Synonymous variants are generally not expected to affect the amino acid sequence encoded by genes, and therefore are strongly depleted of true genetic effects25. We grouped rare synonymous variants (MAC≤40 and MAF<0.1% in each continental population in gnomAD exomes) and ran exome-wide gene-based collapsing tests using GENESIS. We only included gene-based results if there were at least, cumulatively, 20 carriers of qualifying rare variants for the gene (e.g. >=20 individuals carrying any of the qualifying variants of the mask). The significant association rate for synonymous variants was determined at various significance cutoffs for each model: α = 4.3×10−8 (Bonferroni-corrected), 2.6×10−6, 1×10−5, 1×10−4, 1×10−3, and 0.05. As described for the deleterious variants above, we further utilized paired Wilcoxon rank tests and paired T-tests to evaluate the changes in -log10(P) values at different significance levels.

Assessment of exome-wide inflation

Exome-wide test statistics were plotted in quantile-quantile (QQ) plots to visually assess inflation per trait, per model, per variant mask. Exome-wide inflation was further quantified using λ-values, defined as the empirical χ2 statistic at the median divided by the expected χ2 statistic at the median under the null. To assess whether λ-values differed between models without PGS and those adjusted for various PGS across the 65 traits, we utilized two-sided paired Wilcoxon rank tests and paired T-tests.

Data Availability

Summary statistics from the common variant association analyses, the rare variant association analyses, as well as the common variant weights used for polygenic score construction, have been made available for download through the Cardiovascular Disease Knowledge Portal (https://cvd.hugeamp.org/downloads.html). To download the GWAS summary statistics: https://personal.broadinstitute.org/ryank/Jurgens_Pirruccello_2022_GWAS_Sumstats.zip. To download the PGS weights: https://personal.broadinstitute.org/ryank/Jurgens_Pirruccello_2022_PGS_Weights.zip. To download the RVAT summary statistics: https://personal.broadinstitute.org/ryank/Jurgens_Pirruccello_2022_RVAT_Sumstats.zip. Summary statistics for the tests of the statistical properties of different RVAT models are included in the Supplementary Tables. Access to individual level UK Biobank data, both phenotypic and genetic, is available to bona fide researchers through application on the UK Biobank website (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk). The exome sequencing data can be found in the UK Biobank showcase portal https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/label.cgi?id=170. Additional information about registration for access to the data is available at http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/register-apply/. Use of UK Biobank data was performed under application number 17488.

Other datasets utilized in this manuscript include: the dbNSFP database version 4.1a (https://sites.google.com/site/jpopgen/dbNSFP) and gnomAD exomes version 2.1 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/downloads).

Code Availability

Example scripts of our approach for the UK Biobank Research Analysis Platform (implementations of PGS-adjustment in SAIGE-GENE+ and BOLT-LMM) have been made available through the GitHub repository https://github.com/seanjosephjurgens/RVAT_PGSadjust. Quality-control of individual level data was performed using Hail version 0.2 (https://hail.is) as well as PLINK version 2.0.a (https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/2.0/). Variant annotation was performed using VEP version 95 (https://github.com/Ensembl/ensembl-vep). Main common variant association analyses (GWAS) were performed using REGENIE v2.0.2 (https://github.com/rgcgithub/regenie). Genome-wide polygenic scores were computed using PRS-CS (https://github.com/getian107/PRScs; githash: 43128be7fc9ca16ad8b85d8754c538bcfb7ec7b4). Main rare variant association analyses were performed using an adaptation of the R package GENESIS version 2.18 (https://rdrr.io/bioc/GENESIS/man/GENESIS-package.html), which has previously been made available by us through the GitHub repository https://github.com/seanjosephjurgens/UKBB_200KWES_CVD. Analyses were run within R version 4.0 (https://www.r-project.org).

Other RVAT software used in the present study include fastGWA implemented in GCTA version 1.94.0 (https://yanglab.westlake.edu.cn/software/gcta/#fastGWA), BOLT-LMM version 2.4 (https://alkesgroup.broadinstitute.org/BOLT-LMM/BOLT-LMM_manual.html) and SAIGE-GENE+ version 1.0.9 (https://saigegit.github.io/SAIGE-doc/), and REGENIE v2.0.2 (https://github.com/rgcgithub/regenie).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1: Number of significant lead variants from common variant GWAS and variance explained by subsequently derived PGS across the 65 traits.

Part a: Violin plots for the number of significant independent lead variants from common variant GWAS across 65 phenotypes. Results from out-of-sample GWAS (230k, red), in-sample GWAS (190k, blue) and total GWAS (460k, purple) in the UK Biobank are shown. Part b: Violin plots for the phenotypic variance explained (R^2) by 6 types of PGS across the 65 phenotypes. Red shows two PGS derived from out-of-sample GWAS data, blue shows two PGS derived from completely in-sample GWAS data, while purple shows results for PGS derived from total GWAS data. All types of PGS explained variance for their respective traits, although we caution the interpretation of the magnitude of the R2 values for the in-sample and total PGS, as discovery samples were naturally also included in PGS testing. Boxplots: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers.

Extended Data Figure 2: Regression of δ -log10(P) values after PGS-adjustment over the unadjusted -log10(P) values for positive control associations.

The y-axis represents the delta between PGS-adjusted -log10(P) and unadjusted -log10(P) values for positive control associations identified from Backman et al. (ref.5; Supplementary Note), while the x-axis represents the unadjusted -log10(P) values. Part a shows results for out-of-sample derived PGS, part b shows results for in-sample PGS, and part c shows results for the ‘total’ cohort derived PGS. Regression slopes and P-values from standard linear regression are added to the figure. The regression trend line is added in each plot. For all models, there is a trend towards a positive association between unadjusted -log10(P) and the subsequent improvement in RVAT power. The trend reached P<0.0083 (=0.05/6) for all PGS models except PGSCS (insample). Note: β, regression coefficient; δ, difference.

Extended Data Figure 3: Correlation between SNP-heritability and the change in the number of significant rare variant associations after PGS adjustment across the 65 traits.

In each plot, the x-axis represents trait SNP-heritability (h2SNP) estimated using Linkage Disequilibrium Score Regression. The y-axis represents the change in the number of RVAT associations reaching exome-wide significance (α=2.6×10−6) after adjusting for PGS, across the studied traits (N=65). RVAT yield change (defined as the difference in the number of significant associations after PGS adjustment compared to models without PGS) is regressed on h2SNP using ordinary linear regression; the regression trend line is added in each plot. Part a shows results for out-of-sample derived PGS, part b shows results for in-sample PGS, and part c shows results for the ‘total’ cohort derived PGS. For all models, there is a trend towards a positive association between trait h2SNP and change in RVAT yield (P<0.05 and β>0). The trend reached P<0.0083 (=0.05/6) for all PGS models except PGSCS (insample). Note: β, regression coefficient; α, significance cutoff.

Extended Data Figure 4: Results for gene-based testing of LOF and missense variants at MAF<0.1%.

Data are presented in violin plots with overlaid boxplots. The first column shows results restricting to gene-based associations reaching Bonferroni-corrected significance, while the second column shows results for gene-based associations reaching conventional exome-wide significance. Part a shows results for all qualifying gene-based associations. The N gene-trait pairs for distributions in the left panel equal 206, 217, 206, 213, 207 and 218 (from left to right), while the N values equal 321, 327, 310, 318, 320 and 335 (from left to right) in the right panel. Part b is restricted to associations that were identified using MAF<0.1% but which were not identified in the initial analysis where MAC<40 was applied. The N gene-trait pairs for distributions in the left panel equal 25, 33, 28, 33, 28 and 31 (from left to right), while the N values equal 57, 62, 57, 64, 56 and 58 (from left to right) in the right panel. The P-values from Wilcoxon signed rank tests and d values from paired T-tests (after removing outliers) are added above each violin. P-values are two-sided and unadjusted for multiple testing. Boxplots: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Note: , estimated paired group difference; δ, difference; α, significance cutoff.

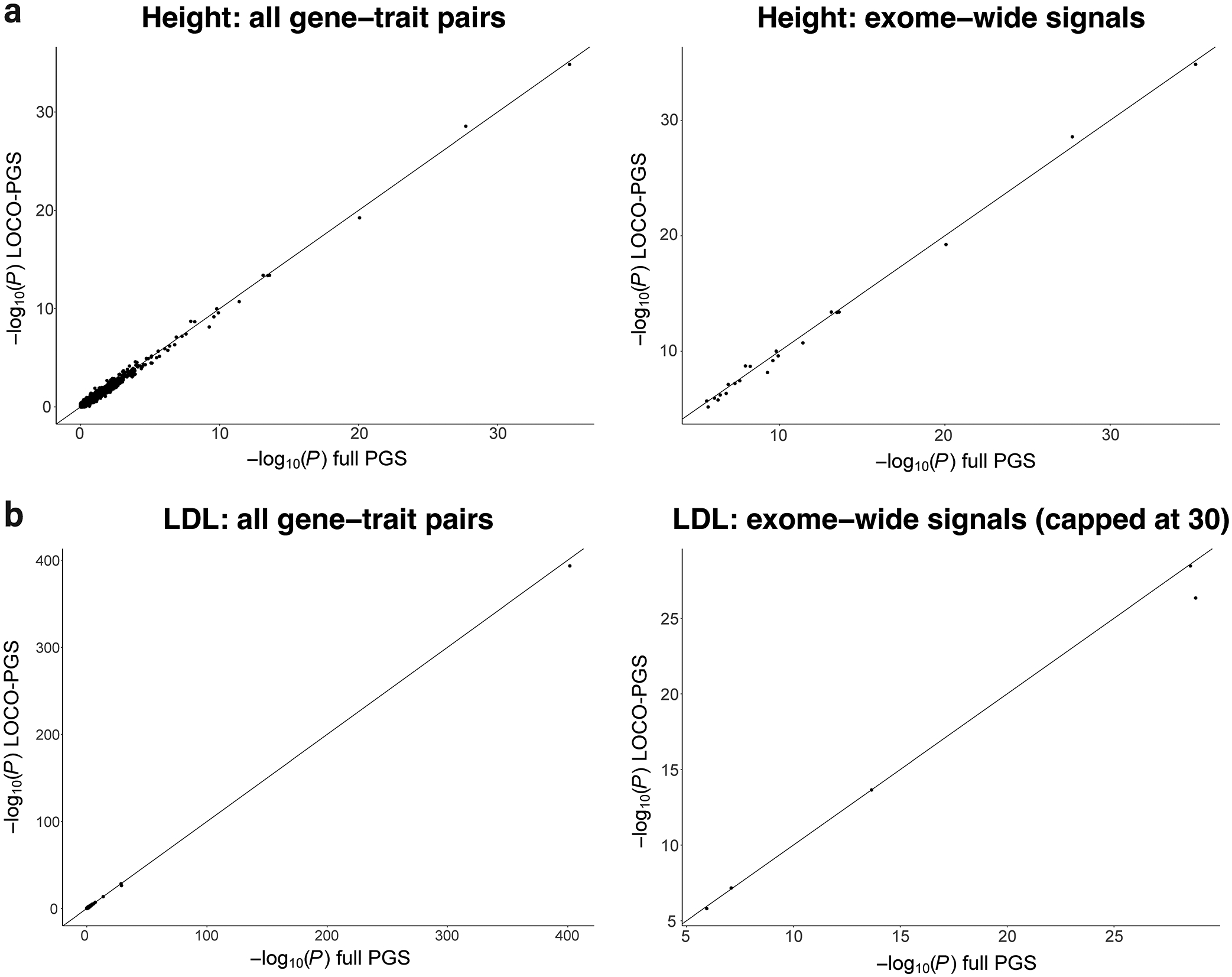

Extended Data Figure 5: Comparison of P-values between full-PGS-adjusted and LOCO-PGS-adjusted models from height and LDL.

In these scatter plots, the y-axis shows -log10(P) values from gene-based testing with adjustment for the full out-of-sample PGSCS, while the x-axis shows the -log10(P) values for the leave-one-chromosome-out (LOCO) PGSCS. Part a shows results for the trait height, while part b shows results for the trait LDL cholesterol. The left panels show all gene-trait pair results, while the right panels all exome-wide significant signals (and are capped at Y=30 and X=30 for clarity).

Extended Data Figure 6: Comparison of P-values between PGS-adjusted and unadjusted models within fastGWA.

The violin plots (with overlaid boxplots) show the distributions of differences in -log10(P) values between unadjusted and PGS adjusted models. The left panel results are restricted to associations reaching Bonferroni corrected significance in either analysis (PGS adjusted or unadjusted), while the right panel is restricted to association reaching conventional exome-wide significance in either analysis. Estimated d values (difference values from paired T-test) and P-values (from paired Wilcoxon signed rank tests) are added above each violin. In all fastGWA runs, a sparsity cutoff of 0.05 was used, while 239,686 high-quality pruned common variants were used for computation of the relatedness matrix. In the left panel, the N gene-trait pairs equal 173, 177, 176 and 175 (from left to right), while in the right panel N values equal 257, 266, 258, 261 (from left to right). P-values are two-sided and unadjusted for multiple testing. Boxplots: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Note: , estimated paired group difference; δ, difference; α, significance cutoff.

Extended Data Figure 7: Comparison of P-values between PGS-adjusted and unadjusted models within BOLT-LMM.

The violin plots (with overlaid boxplots) show the distributions of differences in -log10(P) values between unadjusted and PGS adjusted models. Panels in a show results for adjustment of out-of-sample PGS, where red indicates results for BOLT-LMM-Inf models and gold shows results for BOLT-LMM models. In the left panel, the N gene-trait pairs equal 176, 180, 175 and 182 (from left to right), while in the right panel the N values equal 262, 267, 271 and 282 (from left to right). Panels in b shows results for adjustment for in-sample PGS where blue indicates BOLT-LMM-Inf and gold indicated BOLT-LMM models. In the left panel, the N gene-trait pairs equal 175, 176, 177 and 174 (from left to right), while in the right panel the N values equal 256, 257, 269 and 268 (from left to right). In both a and b, the left panel results are restricted to associations reaching Bonferroni corrected significance in either analysis (PGS adjusted or unadjusted), while the right panel is restricted to association reaching conventional exome-wide significance in either analysis. Estimated d values (difference values from paired T-test) and P-values (from paired Wilcoxon signed rank tests) are added above each violin. In all BOLT runs, 240,699 high-quality pruned common variants were used for computation of the genetic relatedness matrix. P-values are two-sided and unadjusted for multiple testing. Boxplots: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Note: , estimated paired group difference; δ, difference; α, significance cutoff.

Extended Data Figure 8: Comparison of P-values between PGS-adjusted and unadjusted models for SKAT-O tests within SAIGE-GENE+.

The violin plots (with overlaid boxplots) show the distributions of differences in -log10(P) values between unadjusted and PGS adjusted models. The left panel results are restricted to associations reaching Bonferroni corrected significance in either analysis (PGS adjusted or unadjusted), while the right panel is restricted to association reaching conventional exome-wide significance in either analysis. Estimated d values (difference values from paired T-test) and P-values (from paired Wilcoxon signed rank tests) are added above each violin. In all SAIGE-GENE+ runs, the computationally efficient sparse matrix option was used with 0.05 cutoff, while ~240k high-quality pruned common variants (numbers differed slightly per trait) were used for computation of the relatedness matrix. In the left panel, the N gene-trait pairs equal 185, 186, 186 and 182 (from left to right), while in the right panel the N values equal 257, 266, 258 and 261 (from left to right). P-values are two-sided and unadjusted for multiple testing. Boxplots: center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Note: , estimated paired group difference; δ, difference; α, significance cutoff.

Extended Data Figure 9: Comparison of P-values between PGS-adjusted and unadjusted models from REGENIE.

The y-axis of this scatter plot shows the -log10(P) values from gene-based burden testing using REGENIE with adjustment for out-of-sample PGS, while the x-axis shows the unadjusted -log10(P) values from REGENIE. Tests are restricted to Bonferroni-correction significant associations. Part a shows results for PGSlead-SNP while part b shows results for PGSCS. The left panels show all qualifying results, while the right panels are capped at X=100 and Y=100 for clarity. Test statistics were very similar between adjusted and unadjusted models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank all UK Biobank participants, as this study would not have been possible without their contributions. P.T.E. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01HL092577, 5RO1HL139731, 1R01HL157635), the American Heart Association (18SFRN34110082) and by the European Union (MAESTRIA 965286). S.A.L. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01HL139731) and by the American Heart Association (18SFRN34250007). S.J.J. is supported by an Amsterdam UMC Doctoral Fellowship, and by the Junior Clinical Scientist Fellowship from the Dutch Heart Foundation (03-007-2022-0035). J.P.P. is supported by the John S. LaDue Memorial Fellowship for Cardiovascular Research and by the National Institutes of Health (5K08HL159346). S.H.C is supported by National Institutes of Health (R01HL149352, R01HL111024, 2R01HL127564-05A1, 1U01AG058589-01A1, 1U01AG068221-01A1, 1R01HL164824-01), and was supported by BioData Ecosystem Fellowship program.

Competing Interests Statement

P.T.E. has received sponsored research support from Bayer AG, IBM Health, Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer; he has consulted for Bayer AG, Novartis and MyoKardia. S.A.L. is a full-time employee of Novartis Institutes of BioMedical Research as of July 18, 2022. S.A.L. previously received sponsored research support from Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Fitbit, Medtronic, Premier, and IBM, and has consulted for Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Blackstone Life Sciences, and Invitae. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Taliun D et al. Sequencing of 53,831 diverse genomes from the NHLBI TOPMed Program. Nature 590, 290–299 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szustakowski JD et al. Advancing human genetics research and drug discovery through exome sequencing of the UK Biobank. Nat Genet 53, 942–948 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cirulli ET et al. Genome-wide rare variant analysis for thousands of phenotypes in over 70,000 exomes from two cohorts. Nat Commun 11, 542 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jurgens SJ et al. Analysis of rare genetic variation underlying cardiometabolic diseases and traits among 200,000 individuals in the UK Biobank. Nat Genet 54, 240–250 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Backman JD et al. Exome sequencing and analysis of 454,787 UK Biobank participants. Nature 599, 628–634 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge T, Chen CY, Neale BM, Sabuncu MR & Smoller JW Phenome-wide heritability analysis of the UK Biobank. PLoS Genet 13, e1006711 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pirinen M, Donnelly P & Spencer CC Including known covariates can reduce power to detect genetic effects in case-control studies. Nat Genet 44, 848–51 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson LD & Jewell NP Some Surprising Results About Covariate Adjustment in Logistic Regression Models. Internation Statistical Review 58, 227–240 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett D, O’Shea D, Ferguson J, Morris D & Seoighe C Controlling for background genetic effects using polygenic scores improves the power of genome-wide association studies. Sci Rep 11, 19571 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bycroft C et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ge T, Chen CY, Ni Y, Feng YA & Smoller JW Polygenic prediction via Bayesian regression and continuous shrinkage priors. Nat Commun 10, 1776 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasar S et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals activation-induced cytidine deaminase signatures during indolent chronic lymphocytic leukaemia evolution. Nat Commun 6, 8866 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang L et al. A resource-efficient tool for mixed model association analysis of large-scale data. Nat Genet 51, 1749–1755 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang L, Zheng Z, Fang H & Yang J A generalized linear mixed model association tool for biobank-scale data. Nat Genet 53, 1616–1621 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loh PR et al. Efficient Bayesian mixed-model analysis increases association power in large cohorts. Nat Genet 47, 284–90 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou W et al. SAIGE-GENE+ improves the efficiency and accuracy of set-based rare variant association tests. Nat Genet, 10.1038/s41588-022-01178-w (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mbatchou J et al. Computationally efficient whole-genome regression for quantitative and binary traits. Nat Genet 53, 1097–1103 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sudlow C et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 12, e1001779 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yun T et al. Accurate, scalable cohort variant calls using DeepVariant and GLnexus. Bioinformatics 36, 5582–5589 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi SW, Mak TS & O’Reilly PF Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat Protoc 15, 2759–2772 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karczewski KJ et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 581, 434–443 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gogarten SM et al. Genetic association testing using the GENESIS R/Bioconductor package. Bioinformatics 35, 5346–5348 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou W et al. Scalable generalized linear mixed model for region-based association tests in large biobanks and cohorts. Nat Genet 52, 634–639 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bulik-Sullivan BK et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 47, 291–5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Povysil G et al. Rare-variant collapsing analyses for complex traits: guidelines and applications. Nat Rev Genet 20, 747–759 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Summary statistics from the common variant association analyses, the rare variant association analyses, as well as the common variant weights used for polygenic score construction, have been made available for download through the Cardiovascular Disease Knowledge Portal (https://cvd.hugeamp.org/downloads.html). To download the GWAS summary statistics: https://personal.broadinstitute.org/ryank/Jurgens_Pirruccello_2022_GWAS_Sumstats.zip. To download the PGS weights: https://personal.broadinstitute.org/ryank/Jurgens_Pirruccello_2022_PGS_Weights.zip. To download the RVAT summary statistics: https://personal.broadinstitute.org/ryank/Jurgens_Pirruccello_2022_RVAT_Sumstats.zip. Summary statistics for the tests of the statistical properties of different RVAT models are included in the Supplementary Tables. Access to individual level UK Biobank data, both phenotypic and genetic, is available to bona fide researchers through application on the UK Biobank website (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk). The exome sequencing data can be found in the UK Biobank showcase portal https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/label.cgi?id=170. Additional information about registration for access to the data is available at http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/register-apply/. Use of UK Biobank data was performed under application number 17488.

Other datasets utilized in this manuscript include: the dbNSFP database version 4.1a (https://sites.google.com/site/jpopgen/dbNSFP) and gnomAD exomes version 2.1 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/downloads).