Abstract

Objective:

To estimate the effect of diabetes group prenatal care (DGC) on rates of preterm birth and large for gestational age among patients with diabetes in pregnancy compared to individual diabetes prenatal care (IC).

Data Sources:

We searched Ovid Medline 1946-, Embase.com 1947-, Scopus 1823-, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Methods of Study Selection:

We searched electronic databases for randomized controlled trials (RCT) and observational studies comparing DGC to IC among patients with type 2 (T2DM) or gestational diabetes (GDM). The primary outcomes were preterm birth (PTB) prior to 37 weeks gestation and large for gestational age (birthweight >90th%). Secondary outcomes were small for gestational age, cesarean section, neonatal hypoglycemia, NICU admission, breastfeeding at hospital discharge, long acting reversible contraception uptake (LARC), and six-week postpartum visit attendance. Secondary outcomes, limited to the subgroup of patients with GDM, included rates of GDM requiring diabetes medication (A2GDM) and completion of postpartum oral glucose tolerance testing (GTT). Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q-test and I2 statistic. Random-effects models were used to calculate pooled relative risks (RRs) and weighted mean differences.

Tabulations, Integration, and Results:

Eight studies met study criteria and were included in the final analysis: three RCTs and five observational studies. A total of 1,701 patients were included in the pooled studies: 770 (45.3%) in DGC and 931 (54.7%) in IC. Patients in DGC had similar rates of PTB compared to IC (7 studies: pooled rates 9.5% DGC vs. 11.5% IC, pooled RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.59–1.01), which held for RCTs and observational studies. There was no difference between DGC and IC in rates of LGA overall (4 studies: pooled rate 16.7% DGC vs. 20.2% IC; pooled RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.59–1.45) or by study type. Rates of other secondary outcomes were similar between DGC and IC, except patients in DGC were more likely to receive postpartum LARC (3 studies: pooled rates 46.1% DGC vs. 34.1% IC; pooled RR 1.44; 95% CI 1.09, 1.91). When analysis was limited to patients with GDM, there were no differences in rates of A2GDM or postpartum visit attendance, but patients in DGC were significantly more likely to complete their postpartum GTT (5 studies: pooled rate 74.0% DGC vs. 49.4% IC; pooled RR 1.58; 95% CI 1.19–2.09).

Conclusion:

Patients with T2DM and GDM who participate in DGC have similar rates of preterm birth, LGA, and other pregnancy outcomes compared to those who participate in IC; however, they are significantly more likely to receive postpartum LARC and those with GDM are more likely to return for postpartum GTT.

Systematic Review Registration:

PROSPERO, CRD42021279233.

Précis:

Diabetes group prenatal care is associated with similar rates of preterm birth and LGA, but higher postpartum LARC utilization and diabetes testing after GDM than individual prenatal care.

INTRODUCTION

As rates of Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in pregnancy rise,1 so does the need to provide effective antepartum treatment and mitigate long-term risk across the lifecourse.2 The challenge in treating diabetes is that standard management – dietary control, exercise, and pharmacotherapy in selected patients – places the burden of achieving optimum glycemic control largely on the patient with suboptimal support from a heavily burdened medical system.3,4 Prenatal care for patients with diabetes often becomes a missed opportunity because this tends to be a period when people are highly motivated to establish healthy patterns of behavior that may translate into improved long-term metabolic health for the patient and their offspring; yet, there is minimal time and space to facilitate diabetes education and support during traditional individual prenatal care visits.5

Group care, also known as shared medical appointments outside of pregnancy, overcomes many of these barriers and is effective in improving glycemic control and blood pressure management for patients with diabetes outside of pregnancy.6,7 Recent meta-analyses of low-risk pregnant patients without diabetes participating in co-facilitated, 2-hour group prenatal care sessions every 2–4 weeks,8 generally show similar pregnancy outcomes to traditional individual care, including preterm birth and low-birthweight.9–11 However, studies of group prenatal care interventions adapted specifically for patients with T2DM and GDM in pregnancy show promising results. For example, these studies consistently report significant improvement in completion of postpartum GTT among patients with GDM who are randomized to group care,12–15 while most studies of postpartum GTT reminder systems have resulted in only modest improvement.16–18

Participation in diabetes-specific group prenatal care (DGC) facilitates increased time for education, support, and patient-clinician relationships, which may result in improved pregnancy outcomes with decreased rates of preterm birth and large for gestational age neonates (LGA; birthweight ≥90th%).

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to synthesize and pool results from randomized and observational studies of DGC for patients with T2DM and GDM. Our goal was to determine whether participation significantly decreases rates of PTB and LGA compared to individual diabetes prenatal care (IC).

SOURCES

A medical librarian (MD) searched the published literature using strategies to identify interventional studies of group prenatal care for pregnant patients with T2DM or GDM. The search was implemented in Ovid Medline 1946-, Embase.com 1947-, Scopus 1823-, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Clinicaltrials.gov without any limits or filters. The search used a combination of standardized terms and keywords including, but not limited to, (prenatal OR antenatal OR pregnancy OR gestational OR maternal OR perinatal) AND (diabetes OR GDM OR T2DM) AND (group care OR shared medical appointments OR centering OR peer groups). There were a total of 783 results and 290 duplicates were assumed to be accurately identified in Endnote, which brought the final total to 493 unique citations. Full search strategies are provided in Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx. The literature search was initially executed on September 17, 2021 (637 results, 239 duplicates removed, 398 unique citations), updated on January 31, 2022 (48 new citations, 24 duplicates removed, 24 unique citations added) and finalized on February 27, 2023 (98 new citations, 27 duplicates removed, 71 unique citations added). Results were exported to EndNote, Version 20.

STUDY SELECTION

Studies were included if they were English language articles, RCTs or observational studies, focused on pregnant patients with T2DM or GDM, reported pregnancy outcomes in patients participating in group versus individual prenatal care, and published before February 2023. We excluded case reports, case series, review articles, and studies without comparison groups.

The exposure of interest was diabetes group prenatal care (DGC). Maternal and fetal outcomes considered most relevant to diabetes in pregnancy and group prenatal care that could be pooled from at least two studies were included. The primary outcomes were preterm birth (PTB) and large for gestational age (LGA). Secondary outcomes included small for gestational age (birthweight <10th%), cesarean delivery, neonatal hypoglycemia, NICU admission, breastfeeding at hospital discharge, long acting reversible contraception (LARC) initiation, and postpartum visit attendance. Secondary outcomes that were only assessed in the subgroup of patients with GDM included A2GDM (requiring diabetes medication) and completion of postpartum oral glucose tolerance testing (GTT).

Titles and abstracts were independently screened by authors EC and ST. Full text articles were retrieved if they appeared relevant or if there was ambiguity regarding whether it was relevant. Full text articles (or abstracts if the full-text was unavailable) were independently reviewed against inclusion and exclusion criteria by two authors (EC and ST).

Data were independently abstracted from included papers into a standardized abstraction form by ST and RP. Any discrepancies in decisions regarding study inclusion/exclusion were resolved by discussion and consultation with the corresponding author (EC). If data needed to be obtained from a study investigator, the corresponding author was contacted via email. We critically appraised the quality of included studies using Downs and Black checklist.19 We selected this validated tool because it assesses the methodological quality of both randomized and observational studies of healthcare interventions. The checklist included 27 questions in the following quality categories: reporting, external validity, internal validity, and power. ST and RP completed the quality rating form for included manuscripts with a possible maximum score of 28 for high quality studies. While the original paper assigned five points for adequate power, we assigned a single point. High quality studies were considered those in the top quartile of scores.

The METAN software package in STATA SE (Version 17, College Station, TX) was utilized for data analysis. Cochran’s Q and Higgins I2 tests assessed heterogeneity between studies. A conservative threshold of heterogeneity, if P<0.1 or I2>30%, was considered significant. Data were pooled if there were at least two studies with similar definitions available for a given outcome. Relative risks (RR) were calculated from each study with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Publication bias for the primary outcomes was assessed using a funnel plot. Data were pooled with the DerSimonian-Laird random-effects models, even if there was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity. This conservative approach is favored because tests of heterogeneity have low statistical power and the estimated effect sizes that result are more conservative.20 Forest plots were used to plot each categorical outcome. We also performed stratified analyses by study design to assess the way that it may change effect estimates. We conducted subgroup analyses limited to patients with GDM to assess outcomes specific to this patient population, including rates of A2GDM and completion of postpartum GTT. Harbord’s test for categorical variables was used to assess publication bias graphically using funnel plots.

RESULTS

The final electronic literature search returned 783 results including 14 trials from clinicaltrials.gov (Figure 1). Automatic duplicate finder in EndNote Version 20 identified 290 duplicates that were removed for a total of 493 unique citations. Titles for each citation were reviewed for applicability and 476 full-text papers, or abstracts if they were not available, did not meet study inclusion criteria. The bibliographies were reviewed for each selected paper to determine whether any potentially relevant manuscripts were overlooked during the formal search, but none were found. Additional studies were eliminated because none of the a priori selected outcomes were included (n=3)21–23 or data were included in a manuscript that was later published in full-text form and met study criteria (n=6).24–29 Eight studies were included in the final analysis, including three RCTs12,15,30 and five observational studies (Figure 1).13,14,31–33 Characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1: four manuscripts,12–15 and four abstracts.30–33 Most studies occurred at academic medical centers in the United States, except the largest study by Yang et al,15 accounting for ~40% of the pooled sample, occurred across the 3-tier prenatal care system in the city of Tianjin in Northern China. A total of 1,701 patients participated in the pooled studies: 770 (45.3%) in DGC and 931 (54.7%) in IC. Of the 1,541 patients with specified diabetes type, the majority had GDM: 1,365 (88.6%) GDM and 176 (11.4%) T2DM.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of methodology for study selection.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Lead Author | Title | Publication Year | Study Years | Design (RCT/Obs) |

Diabetes Group Care | Individual Care (IC) | Gestational Diabetes (n) | T2DM (n) | Country | Setting | Inclusion | Exclusion | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addae-Konadu* | Group Prenatal Care for Pre-gestational Diabetes: A Feasibility Study for a Randomized Control Trial | 2019 | Unknown | Obs | 31 | 37 | 0 | 68 | USA | Academic Medical Center in Cleveland | T2DM | None listed | Birthweight, gestational age at delivery, NICU admission, LOS, hypoglycemia, RDS |

| Carter | Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Diabetes Group Prenatal Care | 2020 | 2015–2017 | RCT | 40 | 38 | 40 | 38 | USA | Academic medical centers; one in St. Louis, one in Denver | English or Spanish speaking, diabetes diagnosis <=32 weeks, initial study visit between 22.0–34.0 weeks, ability to attend group visits, willingness to be randomized, able to give informed consent | Type 1 diabetes, multiple gestation, major fetal anomaly, serious medical or psychiatric comorbidity necessitating more care | Completion of diabetes self-care activities (diet, exercise, blood sugar testing, medication adherence) |

| *Cummins | Pilot Non-inferiority study of group prenatal care vs. standard care for pregnant people with diabetes | 2022 | 2019–2020 | Obs | 14 | 39 | ? | ? | USA | Academic Medical Center in the Western U.S. | GDM or DM, >3 weeks from anticipated delivery, >18 years, spoke English or Spanish | Unknown | Completion of 6-week prenatal tests, proportion of blood glucose monitoring collected per week |

| Mazzoni | Group Prenatal care for women with gestational diabetes | 2016 | 2012–2014 | Obs | 62 | 103 | 165 | 0 | USA | Obstetric clinic in integrated safety-net healthcare system | GDM diagnosis, attended at least two group visits, English or Spanish speaking | Multiple gestation | Progression to A2GDM |

| *Palmer | Comparison of Group Prenatal Care vs. Standard Prenatal Care for Patients with Diabetes in Pregnancy | 2022 | 2014–2020 | Obs | 42 | 65 | ? | ? | USA | Academic Medical Center | Unknown | Unknown | Blood sugar log to appointments |

| Schellinger | Improved outcomes for Hispanic women with gestational diabetes using the centering pregnancy group prenatal care model | 2016 | 2010–2015 | Obs | 203 | 257 | 460 | 0 | USA | Obstetric clinic at safety-net hospital in Indianapolis | GDM diagnosis, Spanish as preferred language (group care), 18 or older | Multiple gestation, primary language other than English or Spanish, major fetal anomalies | Postpartum GTT |

| *Tate | Group Prenatal care Model Use in Pre-Gestational Diabetes | 2018 | Unknown | RCT | 39 | 31 | 0 | 70 | USA | Tennessee | Pre-gestational diabetes | Unknown | Change in HbA1c from baseline to delivery |

| Yang | A randomised translational trial of lifestyle intervention using a 3-tier shared care approach on pregnancy outcomes in Chinese women with gestational diabetes mellitus but without diabetes | 2014 | 2010–2012 | RCT | 339 | 361 | 700 | 0 | China | 3-tier prenatal care system in Tianjin, China | GDM | Unknown | Macrosomia >4000 g |

Available only as abstract

The range of Downs and Black checklist19 quality scale scores was from 8–24 (median 17, interquartile range 17–23) (Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). High quality studies were considered those in the top quartile of scores, which corresponded with two of the three RCTs12,15 and none of the observational studies; thus, the subgroup analysis by RCT was also considered the subgroup analysis for high-quality studies.

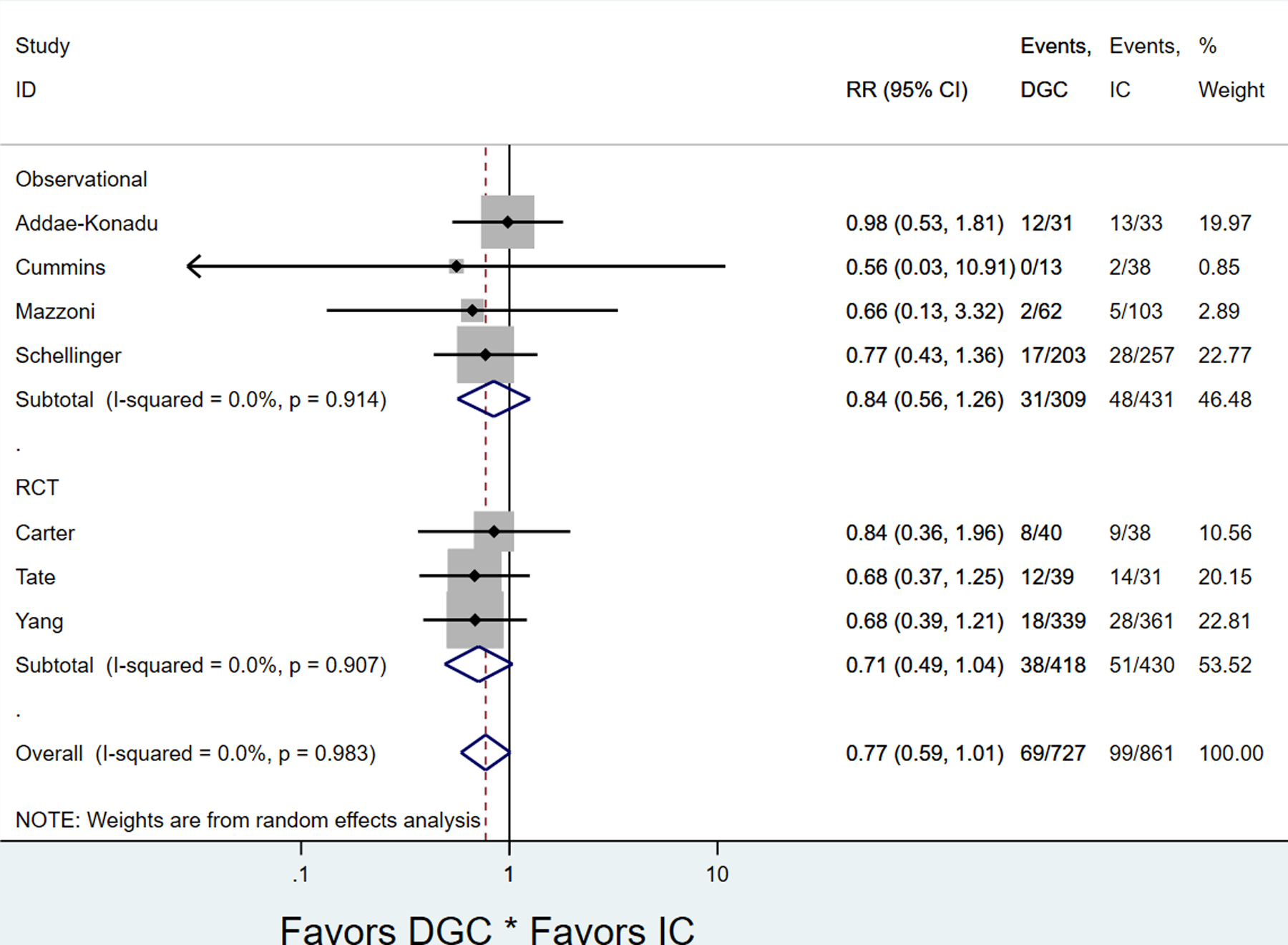

All of the RCTs and four of the five observational studies reported the primary outcome of PTB. Patients in DGC had similar rates of PTB compared to IC (7 studies: pooled rates 9.5% DGC vs. 11.5% IC, pooled RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.59–1.01) (Figure 2, Table 2), which held for RCTs and observational studies (Appendices 3 and 4, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). There was not significant heterogeneity between studies overall (P=0.983, I2=0.0%), nor for RCT’s or observational studies (Figure 2). There was no evidence of publication bias (Harbord test, P=0.225) (Appendix 5).

Figure 2.

Forest plot for pooled preterm birth rate in diabetes group care compared to individual care, stratified by study type. DCG, diabetes group prenatal care; IC, individual diabetes prenatal care; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 2:

Summary of pooled results based on random effects meta-analysis of proportions for primary and secondary endpoints overall and in GDM sub-group

| Outcome | No. of Studies | Diabetes Group Care (DGC) Pooled rate |

Individual Care (IC) Pooled rate |

Pooled RR (95% CI) |

I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcomes | |||||

| Preterm Birth | 7 | 69/727 (9.5%) |

99/861 (11.5%) |

0.77 (0.59, 1.01) | 0 |

| Large for Gestational Age | 4 | 76/454 (16.7%) |

109/540 (20.2%) |

0.93 (0.59, 1.45) | 49.6 |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||

| Small for Gestational Age | 2 | 2/53 (3.8%) |

4/76 (5.3%) |

1.02 (0.16, 6.35) | 0 |

| Cesarean Section | 7 | 377/730 (51.2%) |

428/899 (47.6%) |

0.99 (0.82, 1.20) | 48.8 |

| Neonatal Hypoglycemia | 6 | 47/688 (6.8%) |

38/830 (4.6%) |

1.50 (0.94, 2.40) | 20.7 |

| NICU Admission | 5 | 54/349 (15.5%) |

78/469 (16.6%) |

0.88 (0.64, 1.20) | 0 |

| Breastfeeding at Discharge | 4 | 285/318 (89.6%) |

329/436 (75.4%) |

1.12 (0.96, 1.32) | 82.9 |

| Long Acting Reversible Contraception | 3 | 53/115 (46.1%) |

61/179 (34.1%) |

1.44 (1.09, 1.91) | 0 |

| Postpartum Visit Attendance | 5 | 318/360 (88.3%) |

395/501 (78.8%) |

1.10 (0.96, 1.26) | 68.0 |

| Sub-Group Analysis for patients with GDM Only | |||||

| A2GDM | 5 | 126/338 (37.3%) |

257/478 (53.8%) |

0.82 (0.58, 1.14) | 75.2 |

| GTT | 5 | 250/338 (74.0%) |

236/478 (49.4%) |

1.58 (1.19–2.09) | 63.1 |

| Attended postpartum visit | 4 | 283/318 (89.0%) |

361/458 (78.8%) |

1.13 (0.96, 1.33) | 71.1 |

Bold denotes significance p<0.05

Four studies, including two RCTs and two observational studies, reported LGA. There was no difference between DGC and IC with regard to LGA overall (4 studies: pooled rate 16.7% DGC vs. 20.2% IC; pooled RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.59–1.45) (Figure 3, Table 2) or by study type (Appendices 3 and 4, http://links.lww.com/xxx). There was no evidence of significant heterogeneity overall (P=0.114, I2=49.6%), or among observational studies (P=0.686, I2=0%), but there was heterogeneity between the two RCT’s (P=0.023, I2=80.6%) (Figure 3). There was no evidence of publication bias (Harbord test, P=0.314) (Appendix 6).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for pooled large for gestational age rate in diabetes group care compared to individual care, stratified by study type. DGC, diabetes group prenatal care; IC, individual diabetes prenatal care; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Patients in DGC were significantly more likely to receive postpartum LARC (3 studies: pooled rates 46.1% DGC vs. 34.1% IC; pooled RR 1.44; 95% CI 1.09, 1.91) (Table 2). Otherwise, there were no differences in the secondary outcomes, including SGA, cesarean section, neonatal hypoglycemia, NICU admission, breastfeeding at hospital discharge, or postpartum visit attendance overall (Table 2) or when stratified by study design (Appendices 3 and 4, http://links.lww.com/xxx). However, several secondary outcomes were included in only one study and could not be pooled in stratified analysis by study design (Appendices 3 and 4, http://links.lww.com/xxx). When analysis was limited to patients with GDM, there were no differences in rates of A2GDM or postpartum visit attendance, but patients in DGC were significantly more likely to return for postpartum GTT (5 studies: pooled rate 74.0% DGC vs. 49.4% IC; pooled RR 1.58; 95% CI 1.19–2.09) (Table 2, Figure 4) (Appendix 7 available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx).

Figure 4.

Forest plot for pooled completion of postpartum glucose tolerance testing in diabetes group care compared to individual care, stratified by study type. DGC, diabetes group prenatal care; IC, individual diabetes prenatal care; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review summarized and pooled the results of 8 randomized controlled trials and observational studies and found that pregnant patients with GDM and T2DM who participate in diabetes group prenatal care have similar rates of PTB, LGA, and other diabetes-related pregnancy outcomes. However, DGC participation was associated with significantly higher rates of postpartum LARC uptake and those with GDM were nearly 50% more likely to complete postpartum GTT testing.

This study builds upon two decades of group prenatal care literature; early on, findings overwhelmingly suggested improvement in pregnancy outcomes, however in recent years there have been disappointing findings suggesting no differences between group care and individual care. Jeanette Ickovic’s landmark randomized trial of 1,047 patients in 2007 suggested a 33% risk-reduction in PTB among patients randomized to CenteringPregnancy,34 a commonly practiced form of GPC in the United States. Subsequent studies collectively showed that, compared to individual care, group prenatal care was associated with a host of improved birth outcomes including birthweight, utilization of postpartum contraception, reduction in care utilization, and breastfeeding.35,36 More recent studies make clear that group prenatal care is not the panacea many hoped it would be. Meta-analyses of group prenatal care studies consistently show similar outcomes between patients participating in group compared to individual care.9–11 Most recently, the CRADLE study of 2,350 patients randomized to group prenatal care found similar pregnancy outcomes between group and individual participants overall.37 A recent systematic review of group prenatal care among high-risk patients, including those with diabetes, suggested several positive benefits associated with the intervention, but was limited by a paucity of high-quality data.38

Group care visits outside of pregnancy are more commonly referred to as shared medical appointments. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of shared medical appointments outside of pregnancy for patients with diabetes suggest significantly improved glycemic control, with a statistically significant −0.46 to −0.87 reduction in glycated hemoglobin levels, and improvement in blood pressure management for those participating in group.6,39,40 It should be noted that this literature suffers from many of the same issues of heterogeneity and quality as the group prenatal care literature, but the positive trends in improved medical and behavioral health outcomes are consistent.7

While there was no difference in the primary outcomes or most of the pregnancy outcomes in this meta-analysis of pregnant patients participating in DGC, there are two notable exceptions with potential implications across the life course: receipt of LARC overall and completion of GTT for those with GDM. An interpregnancy interval <24 months is a significant predictor of recurrent GDM;41,42 thus, a 44% increase in LARC utilization among patients participating in DGC has the potential to decrease rates of recurrent GDM and provide adequate time to optimize glycemic control before the next pregnancy for patients with T2DM. The ultimate goal of postpartum diabetes testing is to diagnose T2DM for those who already have it and prevent it for the remainder by employing risk-reducing strategies. Unfortunately, only 20–40% of patients with GDM in the United States return for a postpartum GTT.43 This constitutes a missed opportunity to diagnose and prevent T2DM. While most interventional studies have demonstrated only modest success in improving this key metric of GDM management, DGC stands out as a notable exception.44,45 Completion of the postpartum GTT is crucial for future cardiovascular risk-reduction strategies, early diagnosis, and treatment. The pooled numbers from the studies contributing to this review do not provide the context for these findings. However, in our decade of clinical experience providing diabetes group prenatal care in mixed groups of patients with T2DM and GDM, we see a rich exchange of lived experience between patients with T2DM imparting wisdom, reassurance, and a cautionary tale to patients with GDM. We hypothesize that this regular exposure to the lived expertise of patients with T2DM may be a more powerful reminder and justification for postpartum GTTs among patients with GDM than traditional interventions.

This meta-analysis has several strengths, including a thorough literature search protocol by an experienced research librarian (MD), a registered protocol for study selection and data analysis, utilization of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)46 guidelines, and a rigorous assessment of heterogeneity to produce more conservative effect size estimates. Given the small number of studies and participants available for pooling, our approach combined observational and randomized trials to capture the strengths of each study design while still analyzing them separately and accounting for the quality of each study with the Downs and Black checklist.19 While there are several studies of shared medical appointments for diabetes outside of pregnancy, to our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of the diabetes group prenatal care literature in a pregnant sample.

The findings of this systematic review should be evaluated in the context of several limitations. Meta-analysis findings are only as reliable as the contributing studies. Our results are driven primarily by observational studies of patients with GDM and, as is the case internationally, the diagnostic criteria for GDM differed between studies. Patients with Type 1 Diabetes (T1DM) were excluded from the source studies and our analysis; thus, our findings cannot necessarily be extrapolated to this subgroup of patients with diabetes in pregnancy. Among our study of 1,701 pooled patients with T2DM or GDM, the actual diagnosis was not specified for approximately 9% of the sample. While T2DM and GDM have different diagnostic criteria that are optimally analyzed separately from a research perspective, they exist along a continuum in which many cases of early GDM may actually be previously undiagnosed T2DM; thus, we analyze the sample overall and with GDM-specific outcomes. The sample of patients with T2DM was too small for sub-group analysis.

We also note that four of the eight included studies were published only as abstracts. We contacted the corresponding authors to obtain additional information needed for the analysis when necessary, but granular details of the actual DGC interventions (i.e. range of gestational ages when it occurred, curriculum content, frequency, duration, number of visits attended) were not consistently available and limits generalizability of our findings. Only one third of studies were deemed high quality, primarily due to the limited information available in abstracts.

Preterm birth was selected as a primary outcome based on prior group prenatal care literature in low-risk patients and its availability in nearly all DGC studies. Spontaneous vs. indicated PTB was not reliably collected in the source studies so this level of detail could not be included in the meta-analysis. We were also unable to evaluate important diabetes-related outcomes (i.e. glycemic control, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, umbilical blood cord gas, APGAR score, shoulder dystocia, patient knowledge of diabetes, and satisfaction with prenatal care model) due to significant heterogeneity in the way these outcomes were assessed in the source studies.

Finally, several outcomes in the stratified analysis by study type were only assessed in 1–2 studies or were dominated by one of the three largest studies (Yang, Mazzoni, and Schellinger), which limited our ability to meaningfully pool findings. Small sample sizes—especially among RCT’s—raise the possibility of type 2 errors, even in these pooled results of all of the available literature. Additional well-powered, randomized trials are needed to assess important diabetes-related outcomes and whether DGC improves glycemic control.

In conclusion, our results suggest that pregnant patients with diabetes who participate in DGC have similar rates of preterm birth, LGA, and other pregnancy outcomes. However, there were differences in important postpartum outcomes with potential lifecourse implications, including higher rates of LARC uptake and increased rates of completion of postpartum GTT among those with GDM. While group prenatal care is not the panacea many hoped it would be to improve pregnancy outcomes, this study builds upon prior literature and suggests that DGC is a promising strategy to improve care for patients with diabetes in pregnancy during the postpartum period and, potentially, across the life course.

Ebony B. Carter is supported by the American Diabetes Association Pathway to Stop Diabetes Award (1-19-ACE-02), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Grant #74250, and NIH/NICHD K23 grant HD095075–03. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the American Diabetes Association or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Supplementary Material

Financial Disclosure

Stacey Ehrenberg Buchner reports receiving payment from Dexcom, Inc. Michelle P Debbink reports her institution received payment from the March of Dimes as part of the Reproductive Scientist Development Program, and from the Larry H. Miller Family Foundation as part of the Driving Out Diabetes Program at the University of Utah. Jeannie C. Kelly reports receiving payment to her institution from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Doris Duke Foundation, and past payments from Pew Charitable Trusts and the Barnes Jewish Foundation. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Ebony B. Carter, Associate Editor, Equity, for Obstetrics & Gynecology, was not involved in the review or decision to publish this article.

References

- 1.Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, et al. Trends in Gestational Diabetes at First Live Birth by Race and Ethnicity in the US, 2011–2019. JAMA 2021;326(7):660–669. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powe CE, Carter EB. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Gestational Diabetes: Time to Get Serious. JAMA 2021;326(7):616–617. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yee LM, Leziak K, Jackson J, Niznik CM, Simon MA. Health Care Providers’ Perspectives on Barriers and Facilitators to Care for Low-Income Pregnant Women With Diabetes. Diabetes Spectr 2020;33(2):190–200. doi: 10.2337/ds19-0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yee LM, McGuire JM, Taylor SM, Niznik CM, Simon MA. “I was tired of all the sticking and poking”: Identifying barriers to diabetes self- care among low- income pregnant women. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2015;26(3):926–940. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockliffe L, Peters S, Heazell AEP, Smith DM. Factors influencing health behaviour change during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Health Psychol Rev 2021;15(4):613–632. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2021.1938632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Housden L, Wong ST, Dawes M. Effectiveness of group medical visits for improving diabetes care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2013;185(13):E635–E644. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.130053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon K, Mousa A, de Courten MP, Soldatos G, Egger G, de Courten B. Shared Medical Appointments May Be Effective for Improving Clinical and Behavioral Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017;8:263. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rising SS. Centering pregnancy: An interdisciplinary model of empowerment. J Nurse Midwifery 1998;43(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/S0091-2182(97)00117-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter EB, Temming LA, Akin J, et al. Group Prenatal Care Compared with Traditional Prenatal Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128(3):551–561. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Wang Y, Wu Y, Chen X, Bai J. Effectiveness of the CenteringPregnancy program on maternal and birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2021;120:103981. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catling CJ, Medley N, Foureur M, et al. Group versus conventional antenatal care for women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015(2):Cd007622. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007622.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter EB, Barbier K, Hill PK, et al. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Diabetes Group Prenatal Care. Am J Perinatol 2020. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1714209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Mazzoni SE, Hill PK, Webster KW, Heinrichs GA, Hoffman MC. Group prenatal care for women with gestational diabetes (.). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29(17):2852–2856. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1107541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schellinger MM, Abernathy MP, Amerman B, et al. Improved Outcomes for Hispanic Women with Gestational Diabetes Using the Centering Pregnancy© Group Prenatal Care Model. Matern Child Health J 2017;21(2):297–305. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2114-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang X, Huiguang T : Zhang Fuxia : Zhang Cuiping : Li Yi : Leng Junhong : Wang Leishen : Liu Gongshu : Dong Ling : Yu Zhijie : Hu Gang : Chan Juliana Cn. A randomised translational trial of lifestyle intervention using a 3-tier shared care approach on pregnancy outcomes in Chinese women with gestational diabetes mellitus but without diabetes. J Transl Med 2014;12:290. doi: 10.1186/s12967-014-0290-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamel MS, Werner EF. Interventions to Improve Rate of Diabetes Testing Postpartum in Women With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Diab Rep 2017;17(2):7. doi: 10.1007/s11892-017-0835-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vesco KK, Dietz PM, Bulkley J, et al. A system-based intervention to improve postpartum diabetes screening among women with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207(4):283.e281–283.e286. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shea AK, Shah BR, Clark HD, et al. The effectiveness of implementing a reminder system into routine clinical practice: Does it increase postpartum screening in women with gestational diabetes? Chronic Dis Inj Can 2011;31(2):58–64. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.31.2.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson D The power of the standard test for the presence of heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2006;25(15):2688–2699. doi: 10.1002/sim.2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasso J, McCloskey C, Nordquist S, Franzese C, Queenan RA. The Gestational Diabetes Group Program. J Perinat Educ 2018;27(2):86–97. doi: 10.1891/1058-1243.27.2.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parikh LI, Jelin AC, Iqbal SN, et al. Glycemic control, compliance, and satisfaction for diabetic gravidas in centering group care. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;30(10):1221–1226. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1209650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parikh L, Jelin A, Iqbal S, et al. Do pregnant diabetic patients enrolled in Centering group care have improved compliance? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212(1):S134–S135. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter EB, Barbier K, Hill PK, et al. The effect of Diabetes Group Prenatal Care on Pregnancy Outcomes: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218(1):S579. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazzoni S, Hill P, Heinrichs G, Webster K, Hoffman MC. Group prenatal care for women with diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212(1):S147–S148. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.10.316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazzoni S, Hill P, Briggs A, et al. The effect of group prenatal care for women with diabetes on social support and depressive symptoms: a pilot randomized trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020;33(9):1505–1510. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1520832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schellinger M, Abernathy M, Foxlow L, Carter A, Bastawros D, Haas D. Improved outcomes for Hispanic patients with gestational diabetes using the Centering Pregnancy group prenatal care model. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208(1):S128. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schellinger MM, Barbour KD, Luebbehusen EE, Carter A, Abernathy MP. Improved outcomes for patients with gestational or type 2 diabetes mellitus using the centering pregnancy group prenatal care model. Reprod Sci 2015;22:258A. doi: 10.1177/1933719115579631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carter EB, Barbier K, Hill PK, et al. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Diabetes Group Prenatal Care. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2020;75(12):715–716. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000723720.31435.ce [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tate D, Miller A, Ramser K, et al. Group prenatal care model use in pre-gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218(1):S59. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.10.492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cummins H, Allshouse AA, Metz TD, Debbink MP. Pilot non-inferiority study of group prenatal care versus standard care for pregnant people with diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226(1, Supplement):S519. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmer HE, Crimmins S, Myers M, Martin L. Comparison of Group Prenatal Care versus Standard Prenatal Care for Patients with Diabetes in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226(1, Supplement):S427. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.11.707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Addae-Konadu KL, Stepanek T, Hackney D, Ehrenberg S. Group Prenatal Care for Pre-gestational Diabetes: A Feasibility Study for a Randomized Control Trial. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133(SUPPL 1). doi: 10.1097/01.AOG/01.AOG.0000559216.25911.a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110(2 I):330–339. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Picklesimer AH, Billings D, Hale N, Blackhurst D, Covington-Kolb S. The effect of CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care on preterm birth in a low-income population. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206(5):415.e411–415.e417. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanner-Smith EE, Steinka-Fry KT, Lipsey MW. The effects of CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care on gestational age, birth weight, and fetal demise. Matern Child Health J 2014;18(4):801–809. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1304-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crockett AH, Chen L, Heberlein EC, et al. Group vs traditional prenatal care for improving racial equity in preterm birth and low birthweight: the Centering and Racial Disparities randomized clinical trial study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;227(6):893.e891–893.e815. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byerley BM, Haas DM. A systematic overview of the literature regarding group prenatal care for high-risk pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2017;17(1):329. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1522-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, Williams JW, Jr. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(1):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2978-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papadakis A, Pfoh ER, Hu B, Liu X, Rothberg MB, Misra-Hebert AD. Shared Medical Appointments and Prediabetes: The Power of the Group. Ann Fam Med 2021;19(3):258–261. doi: 10.1370/afm.2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morris JR, Tepper NK. Description and comparison of postpartum use of effective contraception among women with and without diabetes. Contraception 2019;100(6):474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Major CA, deVeciana M, Weeks J, Morgan MA. Recurrence of gestational diabetes: who is at risk? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179(4):1038–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70211-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thayer SM, Lo JO, Caughey AB. Gestational Diabetes: Importance of Follow-up Screening for the Benefit of Long-term Health. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2020;47(3):383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Middleton P, Crowther CA. Reminder systems for women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus to increase uptake of testing for type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014(3). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009578.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang J, Forde R, Parsons J, et al. Interventions to increase the uptake of postpartum diabetes screening among women with previous gestational diabetes: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023;5(10):101137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2023.101137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA StatementThe PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.