Abstract

Sodium selenate (SS) activates protein phosphatase 2 (PP2A) and reduces phosphorylated tau (pTAU) and late post-traumatic seizures after lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI). In EpiBioS4Rx Project 2, a multi-center international study for post-traumatic targets, biomarkers, and treatments, we tested the target relevance and modification by SS of pTAU forms and PP2A and in the LFPI model, at two sites: Einstein and Melbourne. In Experiment 1, adult male rats were assigned to LFPI and sham (both sites) and naïve controls (Einstein). Motor function was monitored by neuroscores. Brains were studied with immunohistochemistry (IHC), Western blots (WBs), or PP2A activity assay, from 2 days to 8 weeks post-operatively. In Experiment 2, LFPI rats received SS for 7 days (SS0.33: 0.33 mg/kg/day; SS1: 1 mg/kg/day, subcutaneously) or vehicle (Veh) post-LFPI and pTAU, PR55 expression, or PP2A activity were studied at 2 days and 1 week (on treatment), or 2 weeks (1 week off treatment). Plasma selenium and SS levels were measured. In Experiment 1 IHC, LFPI rats had higher cortical pTAU-Ser202/Thr205-immunoreactivity (AT8-ir) and pTAU-Ser199/202-ir at 2 days, and pTAU-Thr231-ir (AT180-ir) at 2 days, 2 weeks, and 8 weeks, ipsilaterally to LFPI, than controls. LFPI-2d rats also had higher AT8/total-TAU5-ir in cortical extracts ipsilateral to the lesion (WB). PP2A (PR55-ir) showed time- and region-dependent changes in IHC, but not in WB. PP2A activity was lower in LFPI-1wk than in sham rats. In Experiment 2, SS did not affect neuroscores or cellular AT8-ir, AT180-ir, or PR55-ir in IHC. In WB, total cortical AT8/total-TAU-ir was lower in SS0.33 and SS1 LFPI rats than in Veh rats (2 days, 1 week); total cortical PR55-ir (WB) and PP2A activity were higher in SS1 than Veh rats (2 days). SS dose dependently increased plasma selenium and SS levels. Concordant across-sites data confirm time and pTAU form-specific cortical increases ipsilateral to LFPI. The discordant SS effects may either suggest SS-induced reduction in the numbers of cells with increased pTAU-ir, need for longer treatment, or the involvement of other mechanisms of action.

Keywords: epilepsy, protein phosphatase 2A, selenium, sodium selenate, tau protein, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI)1 is a major cause of neurological deficits including epilepsy, cognitive and neuropsychiatric comorbidities, and mortality.2–6 Post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE)7 may develop in 2–50% of individuals with TBI, with highest rates being after severe TBI.5,8,9 TBI pathologies include neuroinflammation, mitochondrial damage, synaptic reorganization, gliosis and neurodegeneration, and excessive, pathological phosphorylation of tau protein.3,4,10–21

TAU is a microtubule-associated protein expressed predominantly in neurons.22,23 Phosphorylated tau (pTAU) is needed for physiological cellular functions, but excessive or abnormal pTAU can aggregate and impair cellular functions and contribute to neurodegeneration.24–26 Increased pTAU has been implicated in the development of PTE and cognitive disorders, in both human and animal models.10,19–21,27 Protein phosphatase 2 (PP2A) is a serine/threonine phosphatase formed by a family of four classes of regulatory subunits (B [PR55], B’ [B56 or PR61], B’’ [PR72], and B’’’ [PR93/PR110])28, which dephosphorylates pTAU at multiple sites.29,30 PP2A also regulates other kinases, such as glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), and cyclin dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), which may phosphorylate tau at different epitopes.23 Sodium selenate (SS) activates PP2A enzymatic activity; reduces pTAU in Alzheimer's disease (AD), TBI, and epilepsy models; and has been proposed as a potential antiepileptogenic therapy.20,31–33 SS has entered phase 2a clinical trials for AD34 and reduced the frequency of PTE seizures in the lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) model of moderate to severe TBI.31

The Epilepsy Bioinformatics Study for Antiepileptogenesis Therapy (EpiBioS4Rx) is a multi-center international study for the identification of PTE biomarkers and treatments, with the goal of informing future clinical trials. Project 2 of EpiBioS4Rx investigates the target relevance and modification of novel PTE targets and treatments, including SS, using the LFPI model of moderate to severe TBI, and also organizes a multi-center pre-clinical study to test whether tested treatments may reduce PTE rate, and modify candidate PTE biomarkers.35–39 Severe LFPI induces PTE in 25–50% of rats between 6 and 12 months post-injury31,37,40,41 similar to the incidence of PTE reported in TBI patients.42–44 LFPI also induces neuromotor deficits, cognitive impairments, and anxiety- and depressive-like phenotypes.20,35,45–47 In a single laboratory study, reduction of the high pTAU by SS seen in the LFPI models improved functional outcomes and PTE, a pathogenic role for pTAU.10,20

In this study, we examined the target relevance of pTAU and PP2A and modification by SS in the LFPI model, using a short 1week treatment exposure, starting after LFPI, in two pre-clinical laboratories (Einstein, Melbourne) in preparation for a multi-center pre-clinical trial with SS to prevent PTE in the LFPI model. The primary outcomes of this study would be to determine whether (1) cortical perilesional pTAU increase differentiates LFPI from sham craniotomy or naïve control rat brains, and (2) if the main mechanism of action of SS is to reduce the pathological increase in cortical pTAU-ir, by activating PP2A activity. If successful, the findings would inform the selection of biomarker panels that could be used to monitor SS efficacy or PTE prevention.

We investigated the time-, region-, and site-specific tau phosphorylation after LFPI and tested whether 1 week treatment with SS post-injury increases PP2A expression or activity and modifies the pTAU pathology. We assessed the expression of various pTAU forms, using antibodies for different phosphorylation sites, total tau (TAU5), the PR55 regulatory subunit of PP2A, and the PP2A activity in the neocortex, using immunohistochemistry (IHC), Western blots (WB), and a PP2A activity assay. We selected the antibodies to the specific B subunit PR55 isoform (PR55/Bα), because previous studies had shown that this subunit is included in the PP2A holoenzyme associated with microtubules48 and is specific for PP2A-mediated dephosphorylation of tau.20,31,49–51 We examined the neocortical regions in this model because neocortical regions (temporal, frontal, parietal, or occipital) commonly become epileptogenic after severe TBI in humans,52 whereas late spontaneous seizures often have onsets from the perilesional cortical regions in the LFPI model37 (unpublished data from EpiBIOS4Rx project 2).

Methods (Details in Supplementary Text)

Study sites, animals, and experimental design

Two EpiBioS4Rx pre-clinical sites participated: Einstein (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx NY, USA) and Melbourne (Monash University and The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia). All procedures were approved by Einstein Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #20170107) and The Florey Animal Ethics Committee (protocol #17-049 UM). We adhered to the guidelines of the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Animal Research: Reporting of in Vivo Experiments Guidelines and the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats were individually housed in a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle with water and food. Euthanasia and perfusions were performed with isoflurane anesthesia (5%) and intraperitoneal pentobarbital injection (100–150 mg/kg). The experimental design is described in Figure 1.

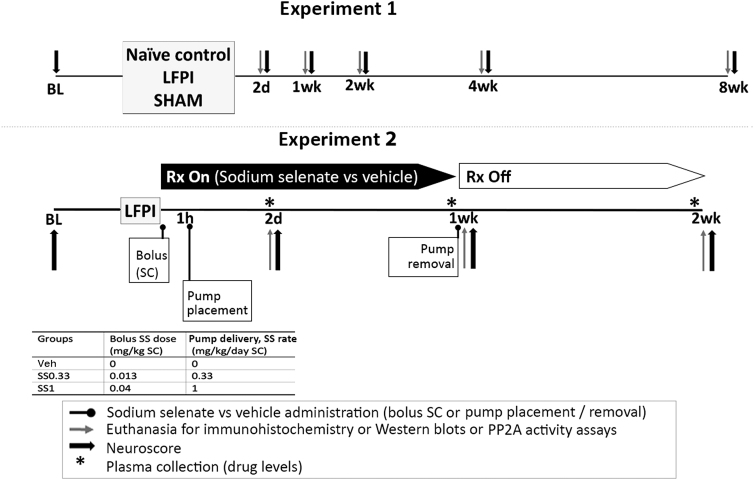

FIG. 1.

Experimental design. (A) Experiment 1. Experiment 1 aimed to identify the target relevance of pTAU forms and treatment windows for pharmacological modification of pTAU in the lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) model. Eleven-week-old sham and LFPI rats were subjected to left parietal 5 mm craniotomy, and only the LFPI group was submitted to FPI. Naïve controls were age matched and not subjected to any survival surgery. Neuroscore assessments were conducted before the craniotomy (BL = baseline), 2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks post-craniotomy or at equivalent ages in naïve controls. Rats were either perfused for immunohistochemistry (Einstein) or had the brains frozen for Western blots or protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activity assays (Melbourne) at 2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks post-craniotomy or at equivalent ages in naïve controls. (B) Experiment 2. Experiment 2 investigated whether sodium selenate (SS) modified early stage post-LFPI functional outcomes (neuroscores) and the pTAU relevant targets that were explored in Experiment 1. Rats were subjected to LFPI as in Experiment 1, and received a bolus injection of either SS or vehicle (Veh group) immediately after the hit. A 2 mL1 Alzet minipump (Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA, USA) was implanted subcutaneously 1 h later to deliver SS or vehicle continuously. Bolus doses and minipump delivery rates are listed in the inserted table. Minipumps were removed 1 week post-LFPI, with the animals under isoflurane anesthesia. Plasma was collected for drug levels prior to euthanasia (2 days, 1 week, or 2 weeks) and prior to pump removal (2 days, 1 week) when this was not a terminal time point, to confirm drug exposure. Neuroscore assessments were conducted before LFPI (BL: baseline), and at 2 days, 1 week, and 2 weeks after injury. Rats were euthanized at 2 days, 1 week (Rx On: during treatment), or 2 weeks (Rx Off: 1 week post- treatment discontinuation) and brains were either perfused for immunohistochemistry or were snap frozen for Western blots or PP2A activity assays. In both experiments, assessment of outcomes, data collection, and analyses were performed by investigators blinded to group allocation.

Craniotomy, LFPI induction, and assessments

Eleven-week-old rats underwent left parietal craniotomy (center: 4.5 mm posterior to bregma, 3 mm left of sagittal suture)53,54 under isoflurane anesthesia (5% induction, 1.5–2.5% maintenance) and buprenorphine analgesia (0.05mg/kg, subcutaneously [SC] after isoflurane induction; Henry Schein, Melville, NY) using trephine (Einstein) or electric drill (Melbourne). After regaining pain response, LFPI rats were connected to the straight connector of the FPI device (AmScien model FP 302, Richmond VA, USA) through the craniotomy hub, and received a pressure pulse.20,31,37,40,54 Time to the first breath (apnea time), hindlimb withdrawal to toe pinch (pain response), and self-righting reflex (SRT) were recorded.20 In shams, the timer started when the rat was connected to the FPI device. Motor function was assessed with neuroscores55,56 (Fig. 1).

SS treatment

SS (Einstein: S8295-25G, MilliporeSigma, St Louis MO; Melbourne: 71948-100G, Sigma-Aldrich, Australia) was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline vehicle (Veh). Treatment groups (Veh, SS0.33, SS1) are described in Figure 1B. In experiment 2, we chose the first post-TBI week as the treatment period to assess the effects of SS on early brain pathologies (expression of pTAU forms, PP2A activity, PR55 expression), as well as early post-traumatic seizures and plasma biomarkers (tested in a follow up study of EpiBioS4Rx project 2).

Selenium and selenate levels measurement (Minnesota)

Plasma samples from blood collected with lateral tail vein puncture were used. Selenium analysis was performed using Thermo Scientific Xseries-2 Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) (University of Minnesota, Department of Earth Science) and Selenium (Se-78), Krypton (Kr-83), and Yttrium (Y-83) as internal standards. Selenate was detected using High Pressure Thermo Scientific Dionex ICS 5000 ion chromatography system (University of Minnesota, Department of Earth Science) and Chromeleon 7 software.

IHC and immunofluorescence (IF) (Einstein)

Rats were anesthetized (isoflurane/pentobarbital) and transcardially perfused with 10% buffered formalin (MilliporeSigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and brains were frozen (-800C).57 Free-floating, cryostat-cut 30μm coronal brain sections underwent IHC using the antibodies listed in Table 1, Ultra-Sensitive ABC Peroxidase Standard Staining Kit, and Vector NovaRED Peroxidase (HRP) Substrate Kit.57,58 Initial studies revealed some non-specific staining in LFPI brains with AT8 antibody, when using secondary antibody BA-2000 (Vector labs) which prompted the use of highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies in our studies (#A16082, Invitrogen, Table 2) as well as shorter times to develop the colorigenic substrate reaction.

Table 1.

Antibodies Used for Immunohistochemistry, Western Blot, and PP2A Activity Assay Experiments

| Antibody | Experiment | Company | Catalog # | Source | Epitope | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Einstein | ||||||

| Primary antibodies | ||||||

| AT8 | IHC | ThermoFisher, USA | MN1020 | Mouse, monoclonal | pTAU-Ser202/Thr205, partially purified human PHF tau | 1:1,000 |

| AT180 | IHC | ThermoFisher, USA | MN1040 | Mouse, monoclonal | pTAU-Thr231, partially purified human PHF tau | 1:1,000 |

| Anti-pTAU Ser199/202 | IHC, IF | ThermoFisher, USA | 44-768-G | Rabbit, polyclonal | pTAU-Ser199/202 of human tau | 1:1,000 (IHC), 1:100 (IF) |

| Anti-pTAU Thr205 | IF | ThermoFisher USA | 44-738G | Rabbit, polyclonal | pTAU-Thr205 of human tau | 1:100 |

| Anti-PP2A/Ba (14-27) (PR55) | IHC | MilliporeSigma, USA | 539521 | Rabbit polyclonal | PP2A/Bα regulatory subunit (FSQVKGAVDDDVAE peptide conjugated to KLH) | 1:500 |

| Anti-NeuN, clone A60 | IF | MilliporeSigma, USA | MAB377 | Mouse monoclonal | Neuron-specific protein NeuN | 1:100 |

| Anti-GFAP, Astro6 | IF | Invitrogen | MA512023 | Mouse monoclonal | Glial fibrillary acidic protein | 1:100 |

| Anti-Iba1, GT10312 | IF | Invitrogen | MA527726 | Mouse monoclonal IgG1 | Iba1 (Ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1), central region | 1:100 |

| Anti-MAP2, mouse IgG1, MT-08 | IF | Thermo Fisher | MA1-19426 | Mouse monoclonal |

Microtubule protein (bovine brain, AA1375-1395 of MAP2ab) | 1:50 |

| Anti-neurofilament H&M, IgG1 (NF-H/NF-M) | IF | Biolegend | 835601 SMI-35R |

Mouse IgG1, k monoclonal |

Neurofilament heavy (H) and medium (M) polypeptide. Reacts with neurofilaments with both high and low levels of phosphorylation. | 1:50 |

| Anti rat RECA-1, clone HIS52 | IF | AbD Serotec | MCA970R | Mouse IgG1, monoclonal | Cell surface antigen of rat endothelial cells. | 1:100 |

| Secondary antibodies | ||||||

| Biotinylated horse anti-mouse antibody | ICH | Vector Labs | BA-2000 | Horse | Anti-mouse IgG | 1:200 |

| Biotinylated goat anti-mouse highly cross adsorbed antibody | ICH | Thermo Fisher, Invitrogen | A16082 | Goat | Anti-mouse IgG | 1:200 |

| Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (heavy chain) superclonal antibody | ICH | Thermo Fisher, Invitrogen | A27035 | Goat | Anti-rabbit IgG | 1:200 |

| Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody | ICH | Vector Labs | BA-1000 | Goat | Anti-mouse | 1:200 |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 546 | IF | Thermo Fisher, Invitrogen | A-11003 | Goat IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed | Anti-mouse IgG | 1:200 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed, Alexa Fluor 488 | IF | Thermo Fisher, Invitrogen | A-11008 | Goat IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed | Anti-rabbit IgG | 1:200 |

| Monash | ||||||

| AT8 | WB | ThermoFisher, Aus | MN1020 | Mouse | pTAU-Ser202/Thr205, partially purified human PHF tau | 1:200 |

| Anti-TAU (TAU5) |

WB | MilliporeSigma, Aus | 577801 | Mouse, monoclonal | Purified bovine microtubule-associated proteins | 1:50 |

| Anti-PP2A, B subunit, clone 2G9 | WB | MilliporeSigma, Aus | 05-592 | Mouse, monoclonal | Residues 398-411 of human PP2A, B subunit (α and δ) | 1:200 |

| GAPDH | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Aus | sc-47724 | Mouse, monoclonal | Human recombinant GAPDH | 1:200 |

| Anti-PP2A Antibody, C subunit, clone 1D6 | PP2A Activity | Millipore Sigma, Aus | 05-421 | Mouse, monoclonal | Residues 295-309 of human catalytic PP2A subunit | 1:200 |

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IF, immunofluorescence; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2; pTAU, phosphorylated tau; WB, Western blot.

Table 2.

Effects of SS on pTAU Forms, PP2A(PR55) and PP2A Activity Are Method and Target Specific

| Antibodies / assays | Target | Method | SS effects at 2 d | SS effects at 1 wk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT8 | pTAU- Ser202/Thr205 | IHC | No effect | No effect |

| AT8/TAU5 | pTAU- Ser202/Thr205 / total TAU ratio | WB | Decrease by SS0.33 and SS1 | Decrease by SS0.33 and SS1 |

| pTAU- Ser199/202 | pTAU- Ser199/202 | IHC | No effect | Not done |

| AT180 | pTAU-Thr231 | IHC | No effect | No effect |

| PR55 | PP2A(PR55) | IHC | No effect | No effect |

| PR55/GAPDH | PP2A(PR55) / GAPDH ratio | WB | Increase by SS1 | No effect |

| PP2A activity | PP2A | Activity assay | Increase by SS1 | No effect |

Using immunochemistry (IHC), we found no effect of SS on AT8-ir, Ser202-ptau-ir, AT180-ir, or PR55 at the neocortex of LFPI rats. Using Western blots (WB), a significant decrease in AT8/TAU5 ratio was seen at 2 days and 1 week of treatment (SS0.33 and SS1) and an increase in PR55/ glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) ratio and PP2A activity was seen at 2 days of treatment.

IF, immunofluorescence; LFPI, lateral fluid percussion injury; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2; pTAU, phosphorylated tau; SS, sodium selenate.

IF staining was done on mounted sections as described,59 with secondary cross-adsorbed antibodies conjugated with AlexaFluor (AF) 488 (#A32731, Invitrogen) or AF546 (#A11003, Invitrogen). Prolong gold antifade with DAPI (P36931, Thermofisher) was used to mount the sections. All IHC and IF kits and secondary antibodies were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

Signal densitometry was performed on IHC sections using ImageJ (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health [NIH]). We selected four regions of interest (ROI) from each hemisphere (i.e., eight ROIs per brain), from a coronal section located 2.12–2.56 mm posterior to bregma,60 which was imaged using an ECLIPSE E1000M microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA). ROIs included the middle layers of the primary motor (M1), somatosensory (S2a, S2b), and granular insular (GI) cortex. For each ROI, we selected ∼20 cells, which appeared intact within the section, to measure the mean somatic signal densities per ROI. Each neuronal cell body was selected with the freehand selection tool of ImageJ and its mean gray value was measured, excluding the axons or processes. The mean somatic signal density per ROI was then calculated by averaging the mean somatic signal densities of all somata measured in each ROI. A single “mean somatic signal density per ROI” value was entered for analysis for each ROI. Signal densities of extracellular matrix (ECM)/processes were derived from areas within each ROI of the section which did not have any visible cell somata. A single mean signal density of ECM/processes per ROI of each section was entered for analysis. Signal densities were normalized to same-assay reference groups to minimize inter-assay variability.

Confocal images of double immunostained IF sections were obtained with the Airyscan module fitted on the Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope, which was set to super resolution mode. Images were acquired with a 63X 1.4NA oil immersion objective at a zoom of 2 × with XY pixel dimensions set at 35 nm. Image data were further deconvolved with the native Airyscan processing software.

Capillary WB (Melbourne)

Rats were euthanized (isoflurane/pentobarbital) and the ipsilateral cortex under the impact site (3–6 mm posterior to bregma, 1.5–4.5 mm left of midline) was rapidly dissected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C. Frozen cortical tissue homogenized and supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (SigmaFast, S8820 and PhosStop, 4906837001, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) had protein concentrations measured with the bicinchonic acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific Pierce Biotechnology, USA).20,31 We used the WES Protein Simple Western System (12-kDA Wes separation module kit, SWM-W001, ProteinSimple, USA) as described.7 Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. Antibody information is in Table 1.

PP2A enzymatic activity assay (Melbourne)

We developed a novel PP2A enzymatic activity assay based on our previous work.20,31 Serial dilutions (1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, and 0.0625 μg/μL) of cortical brain lysates were made. The PP2A catalytic subunit was immunoprecipitated using the anti-PP2A, C subunit (Table 1) or 100 μL/well of normal mouse IgG (5 μg/mL, #12-371, MilliporeSigma) as a negative control and the PP2A activity assay was performed with the EnzChek™ Phosphatase Assay Kit (E12020, ThermoFisher Scientific) and 6,8-difluoro-4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate (DiFMUP) as a substrate. The reaction product of DiFMUP fluoresces with excitation/emission maxima of ∼358/455 nm which was measured with FLUOstar Omega at 5 min intervals (excitation 360 nm; emission 460 nm). Sample concentrations were estimated by linear regression from a standard curve of serial DiFMUP concentrations (10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, and 0.3125 μM). We expressed PP2A activity as the rate of DiFMUP produced at 37°C and 1 unit of PP2A activity was defined as 1 pmol DiFMUP converted by PP2A per min. The fluorescence intensity over time (min) was drawn and the slope of line was calculated. The PP2A activity was calculated as pmol released free phosphate/min/mg protein:20,31

Blinding

Assessment of outcomes, data collection, and analyses were performed by investigators blinded to group allocation, treatments, time points, and hemisphere. Specimens (cortical extracts) and stained sections (IHC, IF) were renamed with blinded codes to permit unbiased analyses by blinded investigators.

Statistical analysis

The two-sample Student's t test (for normally distributed data) or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test (for non-normally distributed data) was used (injury parameters and early outcomes). Composite neuroscores (Fig. 2) and individual components of neuroscore (Figs. S1 and S2) were analyzed using linear mixed models accounting for repeated measures, and Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test was used for pairwise comparisons. Linear regression or linear mixed models to account for same-animal ipsilateral and contralateral ROIs were used in IHC. Given the exploratory nature and multiple groups, we used t tests for pairwise comparisons. Paired t tests assessed hemispheric signal densitometry differences. Mixed-effects analysis with Geisser-Greenhouse correction and Tukey's multiple comparisons test were performed (WB, PP2A activity). We used GraphPad Prism 8.1 (GraphPad Software, LLC, San Diego, CA, USA), JMP 16 Pro, and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) with significance set at p < 0.05.

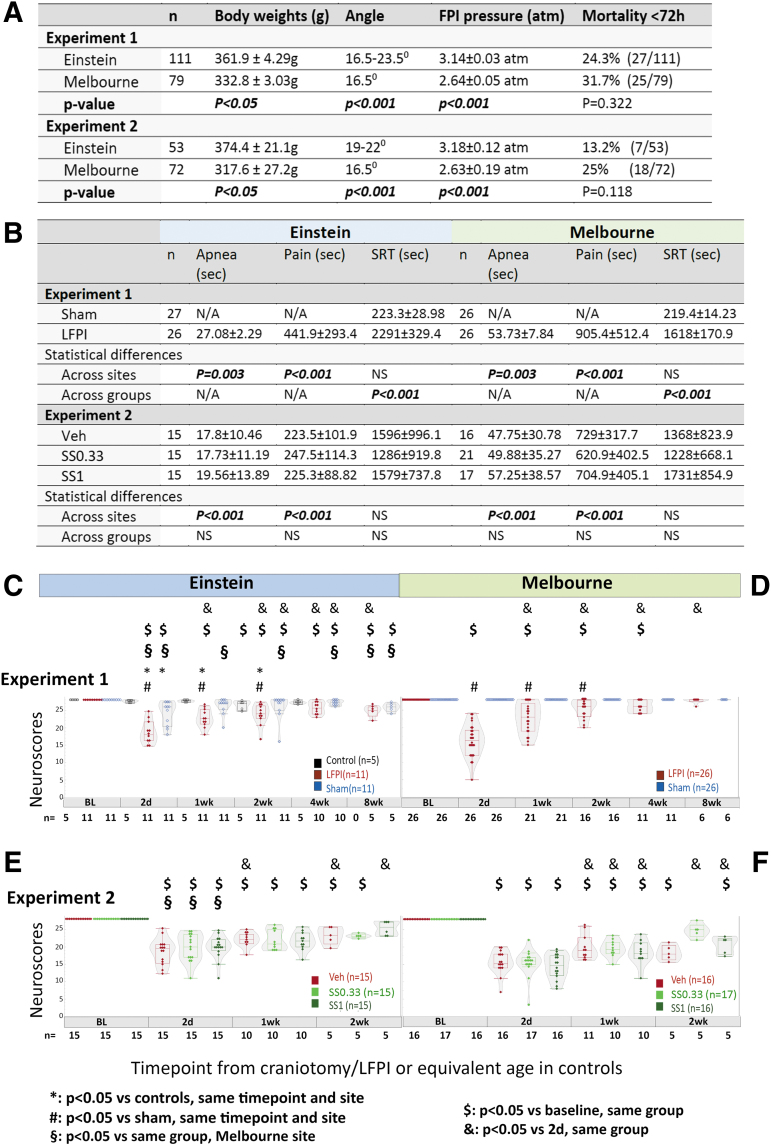

FIG. 2.

Severity assessments in Experiment 1 and 2 (Einstein and Melbourne). (A) Body weights, fluid percussion injury (FPI) settings, and mortality across sites. Means and standard deviations of body weights on the day of recruitment (just prior to injury), FPI pressures (atm), and ranges of FPI angles used to deliver the injury. The p values across sites are derived from Student's t tests. (B) Early outcomes. Mann–Whitney test was used for comparisons in Experiment 1 and Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test were used in Experiment 2. Experiment 1: Einstein LFPI rats had shorter apnea times and first toe pinch responses (pain) than rats from Melbourne. No site differences were seen in the self-righting reflex (SRT) of LFPI or sham rats. At both sites, LFPI rats had significantly longer SRT than shams. Experiment 2: Within sites, no difference in apnea, pain response, or SRT was found across LFPI groups. Across-sites comparisons for each treatment group revealed increased apnea times and pain reflex at Melbourne compared with at Einstein, but not in SRT. (C and D) Neuroscores in Experiment 1 at the Einstein (C) and Melbourne (D) sites. At both sites, LFPI rats showed pronounced neuroscore deficits 2 days after injury compared with baseline or same time point sham (both sites) or controls (Einstein). Neuroscores were more impaired at Melbourne than at Einstein at 2 days only. Neuroscores improved at both sites from 1 week onwards and between 1 and 4 weeks they were consistently better than the 2 day neuroscores at both sites. At 8 weeks post-LFPI, neuroscores were more impaired compared with baseline at Einstein but were still worse than those of Melbourne LFPI rats, which had returned to baseline levels. At Einstein, neuroscores of sham rats showed mild impairment compared with controls at 2 days and compared with their baseline at 2 days as well as between 2 and 8 weeks. Sham rats at Melbourne had no neuroscore impairment and consistently had higher neuroscores than at Einstein at all time points. (E and F) Neuroscores in Experiment 2 at the Einstein (E) and Melbourne (F) sites. All LFPI groups had reduced neuroscores after injury compared with their baseline. No difference was observed among vehicle (Veh), SS0.33, or SS1 groups at any of the sites. Neuroscore statistics were computed using linear mixed-model comparisons, with repeated measures when applicable; Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc was used for pairwise comparisons. The number of rats per group is written under the X axes of panels C–F. atm, atmospheres; LFPI, lateral fluid percussion injury; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; Rx, treatment; SC, subcutaneous; SS, sodium selenate; SS0.33, sodium selenate dose 0.33mg/kg/day; SS1, sodium selenate dose 1mg/kg/day.

Results

Acute injury severity assessments

The site-specific differences in rats and settings for injury and post-injury assessments are described in Figure 2. Although the FPI pressure at Einstein was higher than at Melbourne, acute mortalities (< 72 h from injury) were not statistically different, although Einstein rats demonstrated less severe apnea (p = 0.003) and faster recovery of response to pain after the injury (p < 0.001). SRT did not show significant site differences. Sham rats manifested quicker recovery of SRT than LFPI rats, at both sites (p < 0.001), without site differences. Rats randomized to Veh or SS treatments showed similar acute post-injury assessments at both sites (Fig. 2B).

Neuroscores: Site differences but no effects of SS

Experiment 1 (Fig. 2 C and D)

In LFPI rats, the most impaired neuroscores were observed at 2 days, at both sites; 2 day-neuroscores were worse at Melbourne than at Einstein. Melbourne LFPI rats returned to baseline neuroscores at 8 weeks, whereas Einstein rats were still impaired. Sham rats also manifested mild impairments compared with controls (2 days) and compared with their baseline (2 days, 2–8 weeks) at Einstein, but not at Melbourne. Analysis of each neuroscore component (Fig. S1A) showed that at Einstein the impairment was more consistent on the right (forelimb and hindlimb flexion), more pronounced at 2 days and 1 week after injury, and that some deficits (angleboard) were still detectable at 8 weeks post-LFPI. At Melbourne (Fig. S1B), deficits were also detected between 2 days and 1 week. Except for the right forelimb flexion deficits that were significant up to 2 weeks post-LFPI, they were less lateralizing, and resolved by 4 weeks.

Experiment 2 (Fig. 2 E and F)

At both sites, LFPI rats displayed impaired neuroscores after injury compared with baseline, but there was no treatment-related effect. Einstein rats, regardless of Veh or SS treatment, had less impaired neuroscores than Melbourne rats at 2 days only (p < 0.05). SS had no consistent effect upon individual neuroscore components (Fig. S2).

Early increase in AT8-ir and pTAU-Ser199/202-ir in LFPI rats (IHC)

Cortical AT8-ir was consistently higher (p < 0.05) ipsilateral to the LFPI at all evaluated ROIs (M1, S2a, S2b, GI) at 2 days, at both neuronal somata and ECM/processes, compared with all other groups and the contralateral cortex at the same level (Fig. 3). An exception was the LFPI-2d and Sham-1wk groups, which had no significant differences in AT8-ir staining at the ECM/processes of the M1 region. Sham-1wk had higher somatic AT8-ir only in the ipsilateral M1 cortex at both somata (Fig. 3B) and ECM/processes (p < 0.05 vs each of other groups, except for Sham-2d and LFPI-2d).

FIG. 3.

Early increase in AT8-ir at the cortical middle layers of the M1 and GI cortices (Einstein). (A) Representative AT8-stained 400 × magnified photographs of the left (ipsilateral) lateral cortex (CCX) of control, Sham-2d and left (ipsilateral to injury) or right (contralateral to injury) lateral cortex of LFPI-2d. Intense AT8-ir staining was observed around stained AT8-ir neuronal somata at the left lateral CCX of lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) rats, 2 days after injury. This staining pattern could be the result of increased presence of pTAU AT8-ir in neuronal processes or at the extracellular matrix (ECM), and was not observed at the right lateral cortex. (B) Somatic AT8-ir in the M1 cortex. (C) Somatic AT8-ir in the GI cortex. The asterisks indicate p < 0.05 versus each of the other groups. The total numbers of rats (n) per group are shown in panels B and C. Five rats per group and time point were used except for control (n = 11), Sham-2wk, and LFPI-2wk (n = 6/group) groups. Statistics in B and C used linear mixed- model analyses, including repeated measures when left and right cortical expression was compared. (D) Example of AT8-ir staining consistent with perivascular AT8-ir in the cerebral cortex of an LFPI rat, 2 weeks after the injury. Red arrows show a cortical blood vessel and the black arrow shows a patchy area with increased AT8-ir staining in its vicinity. Double immunostaining with anti-mouse rat RECA-1 antibody (1:100, recognizes endothelial cells) detected by anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to AF546 (red) and rabbit anti-pTAU-Thr205 antibody (rabbit antibody recognizing the Thr205 phosphorylation site as AT8 does) detected with a secondary anti-rabbit antibody labeled with AF488 (green) is also shown. Vessels and capillaries are shown in red and are surrounded by an area with increased pTAU-Thr205-ir staining (green). For antibody information please see Table 1. Each data point at panels B and C represents a different rat. Five rats per group and time point were used except for Sham-2wk and LFPI-2wk, which included six rats/group. AF, Alexa Fluor; CCX, cerebral cortex; GI, granular insular; -ir, immunoreactivity; M1, primary motor cortex.

Initial studies showed occasional nonspecific staining in the absence of AT8 antibody, in some LFPI rats at 2 days, but not in sham or naïve controls or LFPI brains from later time points. The non-specific staining followed the same regional distribution (both background and low-level cellular staining) as the 2 day AT8-ir of LFPI rats, although AT8-ir was significantly stronger than the non-specific staining. Highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies and shorter duration of the colorigenic reactions improved AT8-ir signal-to-noise ratio. Examples of negative controls with omission of primary antibodies are included in Figure S3. Use of rabbit antibodies recognizing a common epitope (e.g., anti- pTAU-Ser199/202) also confirmed the increased pTAU-Ser202 expression (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). This focal AT8-ir pattern of staining was not observed with other mouse antibodies, such as AT180 (Fig. 6), suggesting that AT8-ir epitopes are more specifically linked to areas with injury or altered blood–brain barrier permeability.

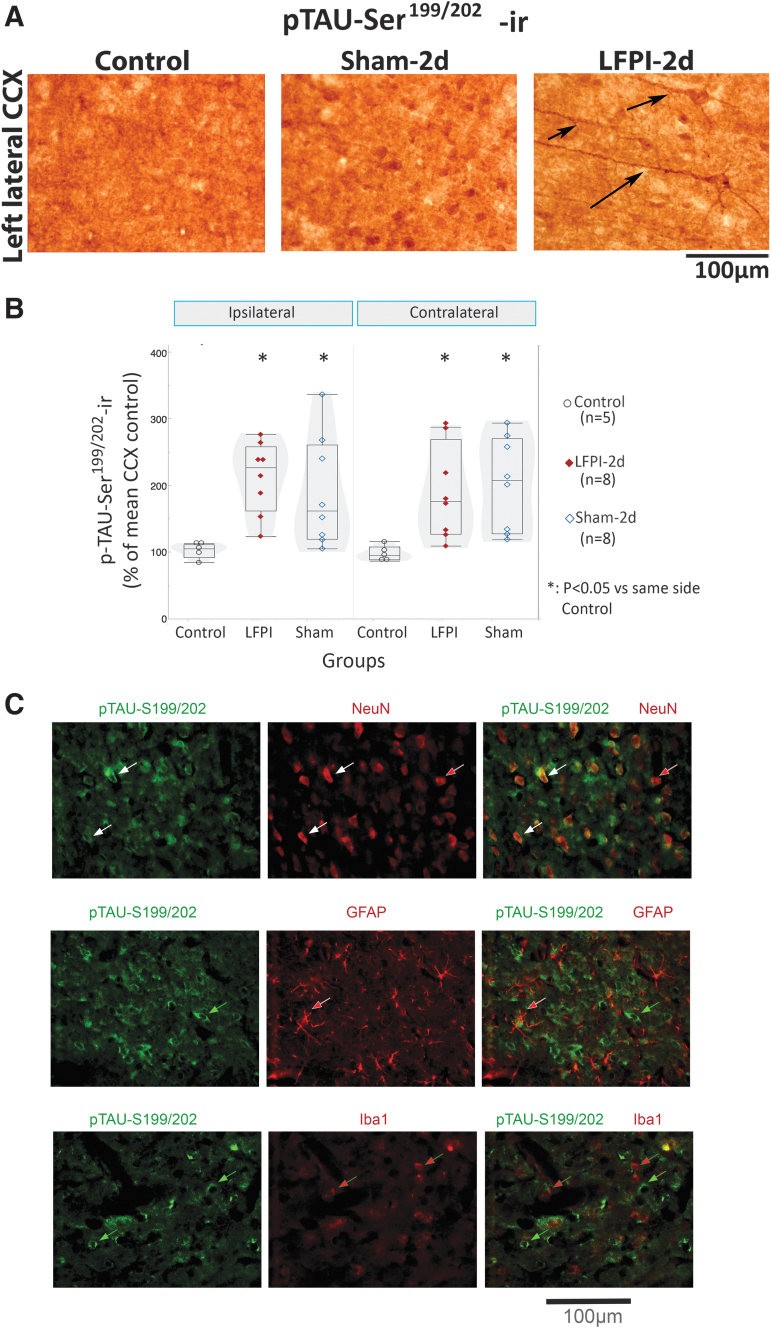

FIG. 4.

pTAU-Ser199/202-ir is present in NeuN-ir neurons in the neocortex of lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) rats (Einstein). (A) Representative pTAU- Ser199/202-stained 400 × photographs of the left lateral cortex (CCX) of control, Sham-2d and LFPI-2d rats. Pathological expression of pTAU- Ser199/202-ir in the processes (black arrows) at the ipsilateral (left) lateral CCX differentiated LFPI rats (11/13 rats) from sham (2/7) or control rats (0/5) (p = 0.0009, Pearson; Fisher's exact two-sided p = 0.0005). Pairwise comparisons with two-tail Fisher's exact test yielded: LFPI versus sham p = 0.0073, LFPI versus control p = 0.0025, sham versus control p = 0.5, and two-tail Wilcoxon test right versus left cortex p = 0.001). (B) Expression of pTAU- Ser199/202-ir is significantly higher in LFPI and sham rats than in controls (Fgroup[2,18] = 5.923, p = 0.01, linear mixed model with repeated measures). LFPI rats had higher pTAU- Ser199/202-ir in the lateral cortex than naïve controls (LCCX or RCCX: p = 0.004, Wilcoxon's test). Sham rats also had increased pTAU- Ser199/202-ir in both the LCCX (p = 0.0157) and the RCCX (p = 0.0068, Wilcoxon's test). Box plots present quantile box plots of mean somatic pTAU- Ser199/202-ir per region of interest and rat. Data are from eight LFPIs, eight shams, and five controls. (C) Double staining of coronal sections from an LFPI-2d rat was performed using a rabbit pTAU-Ser199/202 antibody and a mouse NeuN antibody. The secondary antibodies included an AF488 Goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig)G (H+L) (green) and an AF546-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (red). Double staining shows neurons labeled with both pTAU-Ser199/202-AF488 (green) and NeuN-AF 546 (red) (white arrows), and occasional neurons pTAU-Ser199/202-negative and NeuN-positive (red arrow). We did not see pTAU-Ser199/202 staining in GFAP-AF546 labeled astroglia (red arrows, middle panels) or Iba1-AF546 labeled microglia (red arrows, lower panels). For antibody information please see Table 1. AF, Alexa Fluor; CCX, cerebral cortex; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; Iba1, ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1; -ir, immunoreactivity; LCCX, left CCX; NeuN, neuronal nuclear antigen; pTAU, phosphorylated TAU.

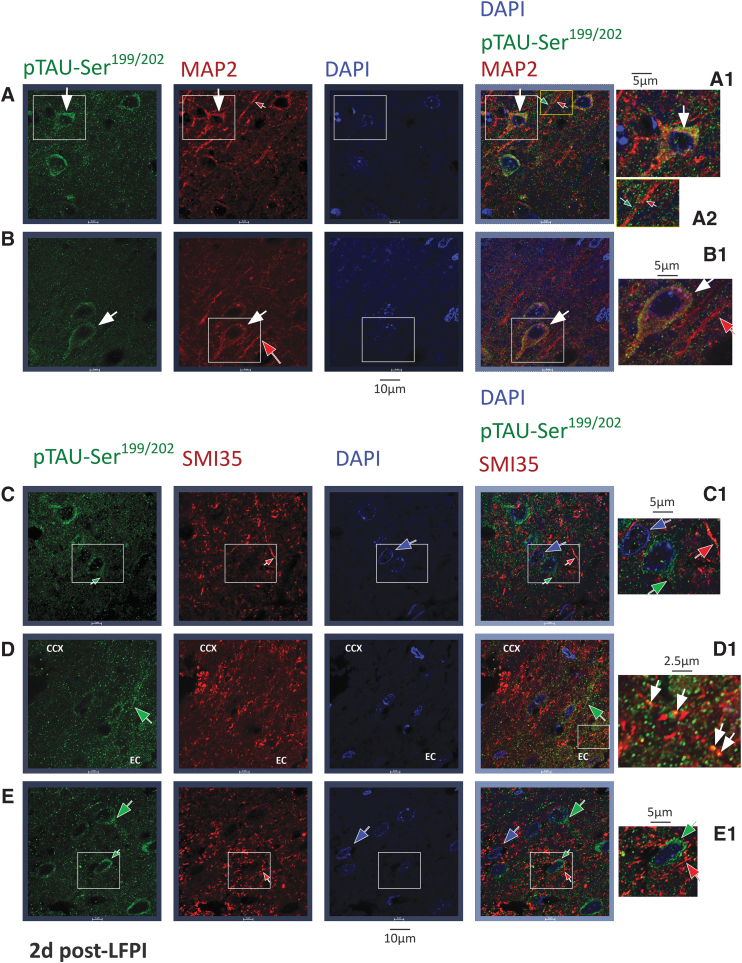

FIG. 5.

pTAU-Ser199/202 : double staining studies with microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP2) and neurofilament H/M (SMI35) markers in the cerebral cortex of lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) rats, 2 days post-LFPI (Einstein). Double immunostaining experiments using anti-pTAU-Ser199/202 antibody detected with AF488 conjugated secondary antibody (green) and either anti-MAP2 (panels A and B) or SMI35 antibody, (panels C–E) detected with AF546-conjugated secondary antibody (red). DAPI was used to label nuclei (blue). Confocal images are from neocortical sections 2 days post-LFPI, ipsilateral to the injury. Panels A1–E1 are magnifications of the white rectangles in panels A–E respectively. Panel A2 is a magnification of the yellow rectangle at panel A. A and B: pTAU-Ser199/202 (green), MAP2 (red), and DAPI (blue) staining. Staining with both pTAU-Ser199/202 and MAP2 (white arrows) was seen at the cytoplasm and proximal MAP2-labeled neuronal processes (likely dendritic). MAP2-labeled distal dendrites with no visible pTAU-Ser199/202 staining are indicated with red arrows. Panels A1 and A2 show neurons labeled with both pTAU-Ser199/202 and MAP2 at cytoplasmic and proximal processes, likely dendritic (magnified white rectangle, white arrows). Panels A2 and B1 show distinct processes labeled with either MAP2 (likely dendritic, red, red arrow) or pTAU-Ser199/202 (green, green arrow). C–E: pTAU-Ser199/202 (green), SMI35 (red), and DAPI (blue) staining. There was no significant double staining between pTAU-Ser199/202 (green arrows) and SMI35 (red arrows) labeled structures. Panels C1 and E1 show SMI35-ir processes (likely axons, red arrows), pTAU-Ser199/202-ir proximal processes (green arrows), or DAPI-positive nuclei (blue) without pTAU-Ser199/202 cytoplasmic staining. Panel D1 shows punctate pTAU-Ser199/202 staining over SMI35-ir processes (yellow spots, likely on axons, white arrows) within the externa capsule. Scale bars indicate the distance. For antibody information please see Table 1. CCX, cerebral cortex; EC, external capsule; DAPI, 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, DNA stain; -ir, -immunoreactivity; SMI35, labels neurofilament heavy (H) and medium (M).

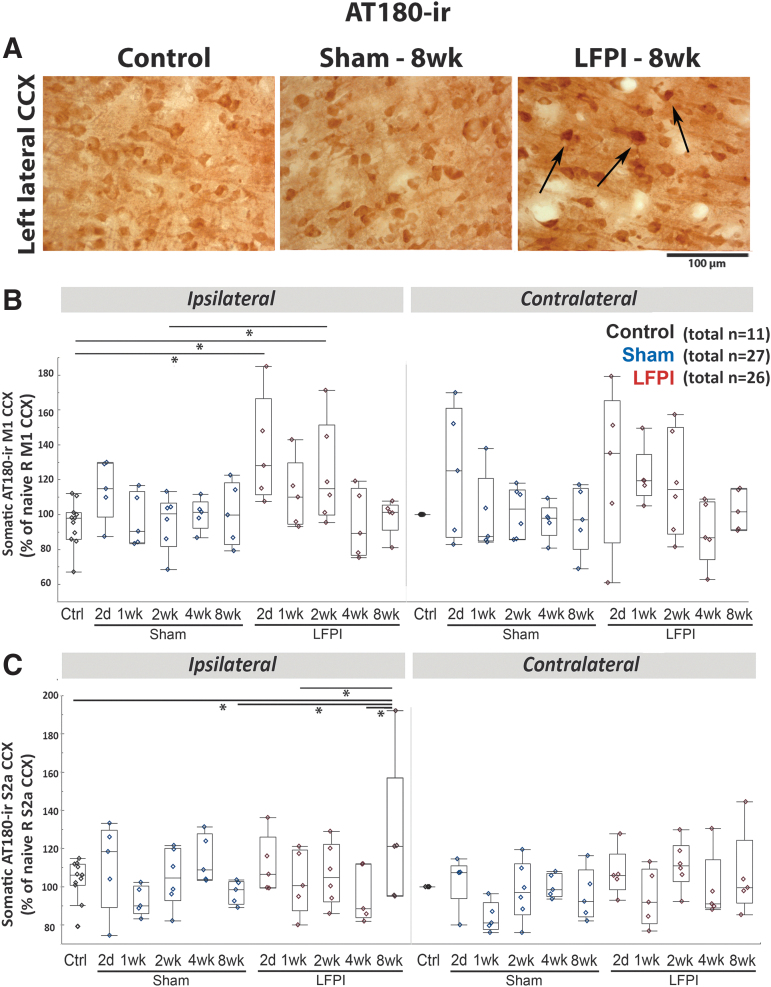

FIG. 6.

AT180-ir: sustained increase at the cortical middle layers of the M1 and S2a cortices of lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) rats, ipsilateral to the injury (Einstein). (A) Representative AT180-stained 400 × magnified photographs of the left lateral cortex (CCX) of control, Sham-8wk and LFPI-8wk rats. (B) Somatic AT180-ir of M1 CCX. Linear mixed model showed increase in AT180-ir of LFPI-2d and LFPI-2wk compared with naïve controls (p < 0.001 and p = 0.004, respectively) and LFPI-2wk compared with Sham-2wk (p = 0.012). No difference was found in the contralateral hemisphere. (C) Somatic AT180-ir of S2a CCX. Linear mixed model showed late increase in AT180-ir at the left S2a cortex of LFPI-8wk compared with naïve controls (p = 0.027), Sham-8wk (p = 0.149), LFPI-1wk (p = 0.049), and LFPI-4wk (p = 0.011) and compared with the right S2a (p = 0.005). Quantile box plots are shown in panels B and C. Each data point represents mean somatic AT180-ir per region of interest and rat. The total numbers of rats per group are shown in panels B and C. Five rats per group and time point were used except for controls (n = 11), Sham-2wk, and LFPI 2wk (n = 6/group). Asterisks indicate p < 0.05 between linked groups. CCX, cerebral cortex; Ctrl, control; 2d, 2 days post LFPI or craniotomy; M1, motor cortex; S2a, sensory cortex S2a.

Perivascular patches of AT8-ir staining at both cellular and extracellular structures around blood vessels were seen in 30.43% (7/23) of the LFPI and 34.78% (8/23) of the sham rats but not in controls (0/10) (p = 0.07) (Fig. 3D). Perivascular AT8-ir was more common at the early (2 days–1 week) than the late time points (2–8 weeks) after LFPI (60% vs 7.7%, p = 0.019) or sham-craniotomy (60% vs 15.4%, p = 0.039) (Fisher's exact test, two-tailed) and was more common at cortical regions than at the hippocampus, amygdala, or hypothalamus.

Higher somatic pTAU-Ser199/202-ir was present in LFPI-2d (n = 8) compared with controls (n = 5) (left: p = 0.043; right: p = 0.007; Wilcoxon test, Fig. 4 A and B). However, pTAU-Ser199/202-ir staining in processes was selective for LFPI-2d rats (11/13) versus Sham-2d (2/7) or controls (0/5) (Fig 2A p = 0.0009, Pearson; Fisher's exact two-sided p = 0.0005). Pairwise comparisons with two-tail Fisher's exact test yielded: LFPI versus Sham p = 0.0073, LFPI versus control p = 0.0025, Sham versus control p = 0.5, and two-tail Wilcoxon test right versus left cortex p = 0.001). A similar result was found in the parasagittal cortex. Double IF experiments were performed on five rats per group (control, sham-2d, LFPI-2d) and confirmed the presence of pTAU-Ser199/202-ir in cortical NeuN-ir neurons but not in astrocytes (GFAP-ir) or microglia (Iba1-ir) (Fig. 4C). The pTAU-Ser199/202-ir was also detected on microtubule-associated protein (MAP)2-ir neuronal somata and proximal MAP2-ir processes, likely dendrites (Fig. 5 A and B). Double staining with pTAU-Ser199/202 and SMI35 antibodies visually resulted in only occasional overlapping pixels in confocal images (Fig. 5 C–E). Overall, pTAU-Ser199/202-ir in LFPI rat cortices is primarily seen in neuronal somata and the dendritic processes of cortical neurons. However, fibrillar or punctate pTAU-Ser199/202-ir structures were also seen outside the cell somata, which were not stained with MAP2-ir (Fig. 5 A2, green arrow) or SMI35-ir (Fig. 5 D, green arrow).

Region- and time-specific induction of AT180-ir (pTAU-Thr231-ir) by LFPI (IHC)

We observed higher AT180-ir staining at both somatic and ECM/processes sites in the ipsilateral than in the contralateral hemisphere of LFPI rats (Fig. 6A). At M1, LFPI-2d and LFPI-2wk had higher somatic staining than controls and LFPI-2wk compared with Sham-2wk (Fig. 6B). At the ECM/processes of the ipsilateral M1 cortex, LFPI-2d (p = 0.005), LFPI-1wk (p = 0.049), and LFPI-2wk (p = 0.011) had higher AT180-ir than the naïve controls. In the lateral cortex ipsilateral to the lesion, S2a and S2b somatic AT180-ir was higher than in controls (S2a: p = 0.027; S2b: p = 0.019) and shams (S2a: p = 0.0149; S2b: p = 0.041), as well as higher than in the contralateral cortex of LFPI-8wk rats (S2a: p = 0.005; S2b: p = 0.049) (Fig. 6 C). In the lateral S2a cortex ipsilateral to the lesion, AT180-ir at the ECM/processes was higher than in controls (S2a: p = 0.01) and shams (S2a: p = 0.003) as well as higher than in the contralateral cortex of LFPI-8wk rats (S2a: p < 0.001). No significant differences were found in AT180-ir at ECM/processes across groups or sides. At the GI, somatic AT180-ir was higher in LFPI-8wk than in LFPI-1wk and Sham-1wk ipsilaterally to the injury side as well as higher than in the contralateral GI of the LFPI-8wk group. AT180-ir at the ECM/processes of the GI cortex was significantly higher ipsilaterally to the lesion in LFPI-8wk rats (p = 0.003); LFPI-8wk rats also had higher AT180-ir at GI ECM/processes than Sham-2d (p = 0.031) and Sham-1wk (p = 0.046). There were no perivascular AT180-ir areas consistently associated with LFPI and/or Sham groups.

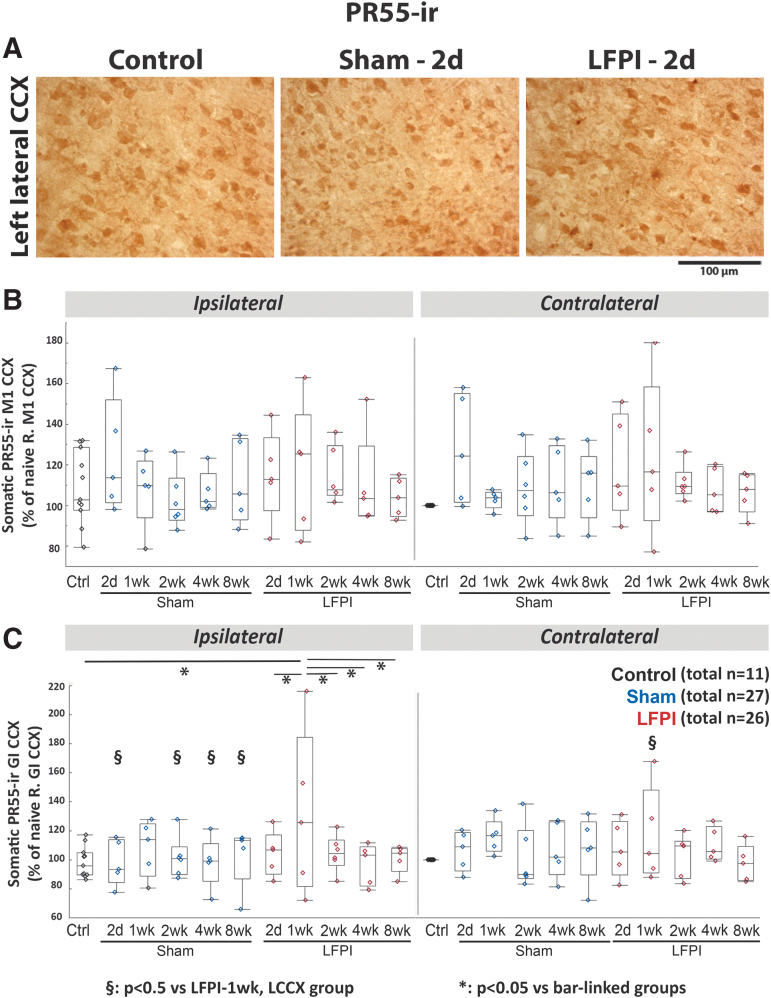

Time- and region-specific PR55-ir expression changes in the lateral cortex (IHC)

No significant differences were observed in somatic PR55-ir expression at the M1 cortex between 2 days and 8 weeks post-LFPI, compared with control or sham rats (Fig. 7B). Somatic PR55-ir expression at the ipsilateral to the lesion lateral cortex was reduced compared with the contralateral at 2 days (S2a: p = 0.012) and 4 weeks (S2b: p = 0.03; GI: p = 0.03). However, higher somatic PR55-ir was seen at the ipsilateral than at the contralateral GI, 1 week post-LFPI compared with the other time points in LFPI rats (p = 0.017) (linear mixed-model analyses). At 1 week post-LFPI, somatic PR55-ir at the ipsilateral GI was also higher than in controls (p = 0.005) and LFPI rats at 2 days (p = 0.047), 2 weeks (p = 0.04), 4 weeks (p = 0.013), and 8 weeks (p = 0.026) (analysis of variance [ANOVA]) (Fig. 7 C). No differences in somatic PR55-ir expression were seen at the other time points at the ipsilateral GI (Fig. 7A and C) Sham-1wk rats demonstrated higher somatic PR55-ir than controls ([left S2a: p = 0.048; left S2b: p = 0.029] [ANOVA])

FIG. 7.

PR55-ir at the cortical middle layers of the M1 and GI cortices (Einstein). (A) Representative PR55-stained 400 × magnified photographs of the left lateral neocortex of control, in Sham-2d and LFPI-2d rats. (B) Somatic PR55-ir of M1 cortices. No difference in PR55-ir was found between groups, sides, or time points. (C) Somatic PR55-ir of GI cortices. Linear mixed model showed increase in PR55-ir of LFPI-1wk compared with all other lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) groups as well as controls and some sham ipsilateral groups (*p < 0.05 between bar-linked groups; §p < 0.05 vs. LFPI-1wk ipsilateral cortex). Increased PR55-ir was seen in the LFPI-1wk groups compared with the ipsilateral GI of the other LFPI time point groups and controls and reduced PR55-ir was seen in the LFPI-4wk groups ipsilateral to the lesion compared with the contralateral side (§p < 0.05 vs. LFPI-1wk, LCCX group). Quantile box plots are shown in panels B and C. Each data point represents mean somatic PR55-ir per region of interest and rat. The total numbers of rats per group are shown in panels B and C. Five rats per group and time point were used except for controls (n = 11), Sham-2wk, and LFPI-2wk (n = 6/group) groups. CCX, cerebral cortex; GI, granular insular; -ir, immunoreactivity; M1, motor cortex.

In the ECM/processes, no significant differences were found in PR55-ir of ECM/processes at the M1 cortex. Higher PR55-ir was present at the ECM/processes of the left S2a of Sham-1wk compared with LFPI-8wk (p = 0.018), LFPI-2wk (p = 0.046), LFPI-2d (p = 0.006), Sham-4wk (0.018), Sham-2d (0.038), and controls (0.01) as well as at the left S2a of LFPI-1wk compared with LFPI-2d (p = 0.039). Lower PR55-ir was also present at the ECM/processes of left S2b of LFPI-4wk (p = 0.006) and Sham-8wk (p = 0.033) groups; Sham-1wk had higher PR55-ir than controls (p = 0.016), Sham-2wk (p = 0.034), and LFPI-8wk (p = 0.032). However, the left GI of LFPI-1wk rats had higher PR55-ir in the ECM/processes than the right GI (p = 0.014) and the left GI of controls (p = 0.008), LFPI-2d (p = 0.048), LFPI-4wk (0.037), and LFPI-8wk (0.049).

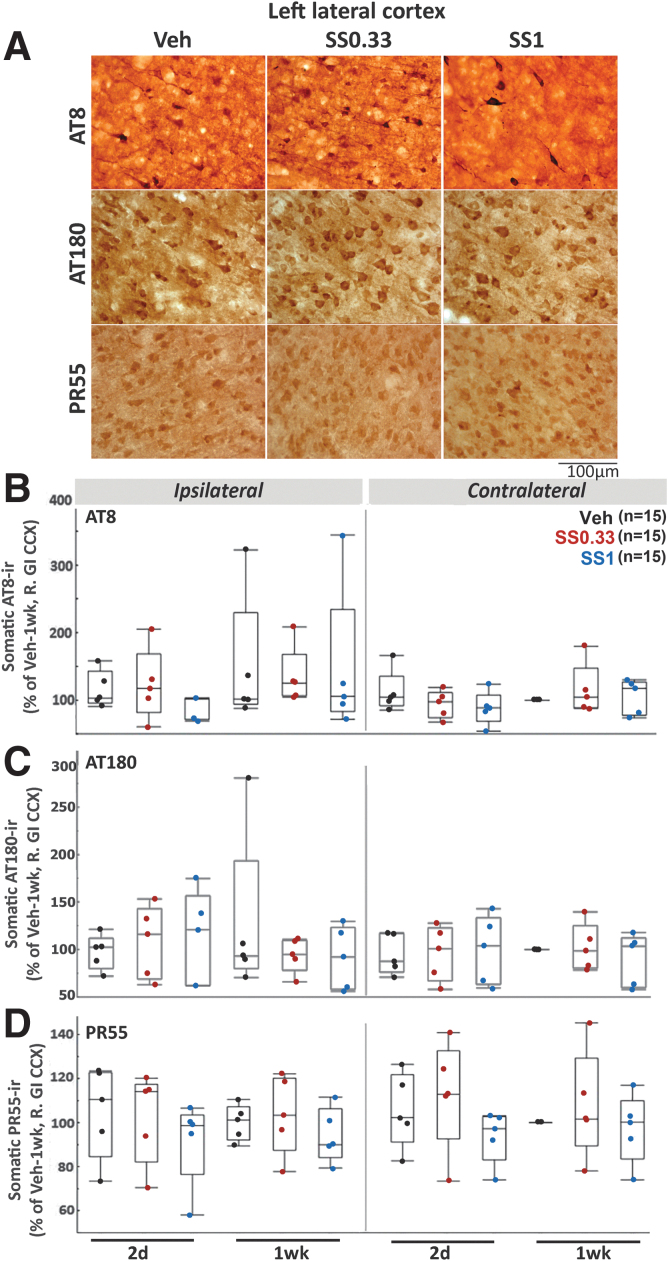

SS treatment did not alter AT8, AT180 or PR55 immunoreactivity in the cortex in IHC

SS did not alter AT8-ir (Fig. 8A and B), AT180-ir (Fig. 8A and C), or PR55-ir (Fig. 8A and D) in any of the four cortical regions in IHC studies, based on ANOVA for dose and time point, conducted for each side separately.

FIG. 8.

Sodium selenate (SS) does not alter AT8-ir, AT180-ir, or PR55-ir expression in the cerebral cortex (CCX) of lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) rats (Einstein). (A) Representative AT8, AT180, and PR55-stained sections from 400 × magnified photographs of the left (ipsilateral) CCX from each experimental group: Vehicle (Veh), SS0.33, and SS1. (B–D) Somatic AT8-ir (B), AT180-ir (C), and PR55-ir (D) in the middle layers of the granular insular cortices (GI CCX) of LFPI rats treated with Veh or SS (SS0.33, SS1 groups), as described in Figure 1. Graphs depict quantile boxes from densitometric measurements from the side ipsilateral (left) or contralateral to the LFPI CCX (right). The number of rats per group is included in panels B–D. Individual data points represent mean somatic immunoreactivity per region of interest, per rat, expressed as percent of the right GI CCX from the Veh-1wk group. No significant effect was found for any of the SS treatment groups. Each data point is derived from a different rat. Five rats per group and time point were used. GI, granular insular cortex; -ir, immunoreactivity; M1, primary motor cortex; SS0.33, sodium selenate dose 0.33mg/kg/day (Table 1); SS1, sodium selenate dose 1mg/kg/day (Table 1).

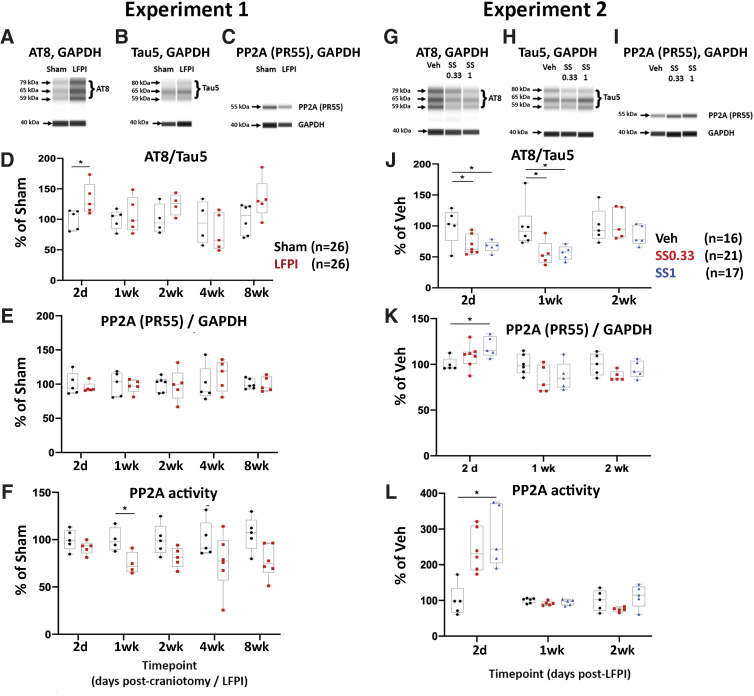

LFPI and SS effects on cortical AT8/TAU5 and PR55/GAPDH (WB) and cortical PP2A activity

Experiment 1:

Automated capillary WBs were used to quantify AT8/TAU5 (Fig. 9A, B, and D) and PR55/GAPDH (Fig. 9 C and E) ratios in the ipsilateral cortex. Although the linear mixed model analyses failed to identify significant changes, there were trends suggesting higher AT8/TAU5 and lower PR55/GAPDH after LFPI (Fig. 9 D and E). Therefore, further pairwise comparisons revealed higher AT8/TAU5 (p < 0.05) in LFPI-2d (Fig. 9 D). Linear mixed-model analysis identified a significant injury effect on the PP2A enzymatic activity (F[1, 40] = 18.5, p < 0.001) (Fig. 9 F). Post-hoc analyses indicated significantly lower PP2A activity in LFPI than in Sham, 1 week after craniotomy/LFPI (p < 0.05) (Fig. 9 F).

FIG. 9.

Lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) increases Tau phosphorylation and reduces PP2A expression and enzymatic activity (Monash). Automated capillary Western blots were used to quantify protein expression of AT8-ir and PP2A subunit B at different time points post-TBI. (A–C) Digital-gel images of representative blots stained with AT8 (A), TAU5 (B), PR55 (C), and GAPDH antibodies (A–C, 40 kDa band) from Sham and LFPI. (D) AT8/TAU5 ratio is higher in LFPI than in sham rats, 2 days after LFPI. The AT8-ir results were expressed as the ratio of AT8-ir bands (MW 59, 65, and 79 kDa) over the TAU5-ir (total Tau) bands (MW 59, 65, and 80 kDa).20 (E) PR55/GAPDH ratio was not significantly different between Sham and LFPI. (F) Linear mixed-model analysis of a novel PP2A enzymatic activity assay showed a significant injury effect on the activity of PP2A after LFPI. Asterisks: p < 0.05 versus Sham in panels D–F.

(G-I) Digital-gel images of representative blots of AT8 (G) TAU5 (H), PR55 (I), and GAPDH (G-I, 40 kDa) stained blots from Veh, SS0.33, and SS1 LFPI rats. (J) Both sodium selenate (SS) treatment protocols reduced AT8/TAU5 at 2 days and 1 week post-LFPI. (K) Only the SS1 treatment was able to significantly increase PR55/TAU5 ratio 2 days after LFPI. (L) The PP2A enzymatic activity was significantly increased in the high-dose SS1 treatment group at 2 days only. The total numbers of rats per group are indicated next to panels D and J. Each data point corresponds to data from a different rat. Five rats per group were used except for: Sham-2wk, LFPI-2wk (n = 4/group) and Sham-8wk (n = 6/group) at panel D; Sham-2wk (n = 6) at panel E; Sham-1wk (n = 4), LFPI-1wk (n = 4), and LFPI-4wk (n = 6); SS0.33-2d (n = 7), Veh-1wk (n = 6) at panel J; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; SS, sodium selenate; SS0.33, sodium selenate dose 0.33 mg/kg/day; SS1, sodium selenate dose 1 mg/kg/day; Veh, vehicle.

Experiment 2

We then asked whether treatment with SS could modify the protein expression of AT8/TAU5, PR55/GAPDH, and PP2A enzymatic activity. Linear mixed-model analysis did not show significant AT8/TAU5 (Fig. 9G, H, and J) and PR55/GAPDH (Fig. 9I and K) changes between Veh and SS0.33 or SS1 (Fig. 9 J and K). Further pairwise comparisons showed that both doses of SS treatment significantly lowered AT8/TAU5 expression 2 days and 1 week after LFPI (p < 0.05) (Fig. 9 J). T test analysis also revealed that SS-treated LFPI rats (1 mg/kg/day) had significantly higher PR55/GAPDH than vehicle-treated LFPI rats, 2 days post-LFPI (Fig. 9 K). Linear mixed-model analysis of PP2A enzymatic activity identified a significant treatment effect (F[1.924, 9.618] = 8.34, p < 0.01) (Fig. 9 L). The SS1 group had higher PP2A activity than Veh, 2 days post-LFPI (p < 0.05, Tukey post-hoc). It is unclear why the PR55/GAPDH and PP2A activity at 1week was not also changed in response to SS treatment. Figure 9 F data demonstrate lower PP2A activity in cortical extracts of LFPI rats, 1 week post-LFPI, than in Sham, which may have rendered the assay at this time point less sensitive to documenting significant increases in PP2A activity in SS-treated LFPI rats compared with Veh-treated LFPI rats (Fig. 9 L).

Plasma selenium and SS plasma concentration is dose dependent

Plasma selenium concentrations increased dose dependently during SS treatment (2 days, 1 week) and returned to baseline 1week after pump removal (Table 3). Plasma SS concentrations were undetectable in the Veh group and increased dose dependently in SS-treated groups.

Table 3.

Plasma Selenium and Selenate (SS) Concentrations in LFPI Rats

| |

Plasma selenium concentrations (ng/mL) |

Plasma SS concentrations (ng/mL) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 2 d (Rx ON) | 1 wk (Rx ON) | 2 wk (Rx OFF) | 1 wk (Rx ON) |

| Veh | 180 ± 24.8 | 164 ± 40.6 | 181 ± 33.1 | Undetectable |

| SS0.33 | 351 ± 49.6 # | 304 ± 119 # | 228 ± 81.2 | 8.41 ± 7.2 |

| SS1 | 521 ± 109 * | 433 ± 95.2 * | Not assessed | 24.2 ± 14.3 * |

Plasma selenium and sodium selenate (SS) concentrations (means ± standard deviation [SD]) in LFPI rats during treatment (Rx on, 2 days or 1 week) and a week after treatment discontinuation (Rx off, 2 weeks) (Minnesota). SS was delivered subcutaneously (SC) for 7 days via an osmotic minipump as in the Methods section and Figure 1. Plasma selenium concentrations increased with dose during treatment (2 days, 1 week) and returned to baseline a week after pump removal (n = 7–9/group and time point). Plasma SS levels also increased dose dependently at 1 week after treatment initiation (n = 7/group). Treatment groups (Veh, SS0.33, SS1) are described in Figure 1.

p < 0.05 versus SS0.33; #p < 0.05 versus Veh.

LFPI, lateral fluid percussion injury; Rx, treatment; Veh, vehicle.

Discussion

We report time-, pTAU phosphorylation form-, and region-specific increases in cortical pTAU expression following LFPI, ipsilateral to the lesion with both IHC and WB. The PR55-ir expression changes were not consistent in IHC and not present in WB. PP2A activity was reduced 1week post-LFPI at the ipsilateral to the lesion cortical extracts. SS, a PP2A activator shown by the Melbourne group to reduce pTAU and seizures in various experimental models, including the LFPI,20,31,61 had divergent effects on pTAU-ir or PR55-ir using IHC and WB. We saw no effects of SS in the IHC studies, but saw significantly lower AT8/TAU5 (2 days, both SS doses), higher of PR55/GAPDH levels (2 days, SS1 only) in the WB, and higher PP2A activity (2 days, SS1 only) in protein extracts from the ipsilateral to the injury neocortex. Our data suggest that SS does not change pTAU-ir or PR55-ir expression in individual cells, but has an apparent injury-modifying effect, resulting in lower total pTAU and higher total PP2A activity in the ipsilateral to the lesion cortex.

LFPI resulted in a transient, early (2 days post-LFPI) AT8-ir increase in both intra- and extracellular structures (IHC) as well as in the total AT8-ir content of the perilesional cortex (WB). A third of the LFPI and sham rats, but not controls, showed clear perivascular AT8-ir staining, which was more common during the 1st week after LFPI or craniotomy. Previous IHC/WB studies reported small AT8-ir increases after controlled cortical impact and FPI from 4 h post-injury and increasing at 6–12 months post-TBI.62–65 Perivascular AT8-ir has also been shown in models of repetitive TBI,1,66–68 and in patients with chronic traumatic encephalopathy1,69 or drug-resistant epilepsy.70 Perivascular AT8-ir deposits have not yet been systematically investigated in models of severe TBI. We also observed similar perivascular AT8-ir deposits in some sham rats, consistent with the observations in IHC and neuroscores at Einstein that craniotomy alone may produce some pathology. It is possible that the local pressure during the preparation of the craniotomy may result in mild local cerebral edema and capillary extravasation, as has been shown previously in cats.71 In the models of repetitive TBI,66–68 sham animals did not have such pathologies; however, those shams also did not have a craniotomy, as injury was done on an intact skull. The different time course and magnitude of changes across studies may be attributed to the different models, species, techniques, severities of injury, or sensitivity of the detection methods. The concordant findings in our study conducted independently at two laboratories using different detection techniques provide robust evidence for transient high cortical AT8-ir ipsilateral to the lesion. We also show higher somatic AT180-ir after LFPI in the cerebral cortex ipsilateral to the lesion, which was more persistent than the increased AT8-ir and followed region-specific patterns, possibly tracking the lesion progression. The morphology of the AT180-ir cells suggests a neuronal phenotype. Higher AT180-ir was also reported in a parasagittal FPI model 4–24 h after injury.63 The early increase in AT8-ir and more sustained increase in AT180-ir in the cerebral cortex of LFPI rats render pTAU-ir a valid target in treatment trials aiming to modify the PTE and associated pathologies, as planned in the EpiBioS4Rx SS trial.

Sham rats had elevated AT8-ir 1 week post-craniotomy, in a very localized area of the M1 cortex, whereas the AT8-ir higher in the lateral cortex was specific to the LFPI rats. Perivascular AT8-ir was also observed in shams, most commonly 2 days–1 week post-craniotomy. The mild impairment of neuroscores in the Einstein sham cohort (Fig. 2) also corroborates that craniotomy may occasionally cause mild injury and hence pTAU increase.72–74 The use of trephine (Einstein) versus a drill (Melbourne)74 or the different sources of rats75 could contribute to the site differences in the neuroscores of sham rats.74

Tau phosphorylation occurs at different and multiple Ser or Thr residues depending upon the Tau conformation. Excessive/abnormal pTAU may cause paired helical filament formation and aggregation into pretangles or filamentous intra- or extracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs).23,76 However, the susceptibility to form aggregates and NFTs varies according to the phosphorylation site as well as to additional post-translational modification of Tau.77,78 Further studies to determine whether and when the observed high levels of pTAU in the LFPI model may result in aggregation or NFTs are needed.

There was occasional non-specific staining in the absence of AT8 antibody, in some LFPI rats at 2 days, but not in sham or naïve controls or LFPI brains from later time points. The non-specific staining followed the same regional distribution (both background and low-level cellular staining) as the 2 day AT8-ir of LFPI rats ipsilateral to the lesion, although AT8-ir was significantly stronger. This could be the result of acute post-TBI pathologies; that is, tissue injury or blood–brain barrier disruption, that generate epitopes cross-reactive with the anti-mouse immunoglobulin and AT8 antibodies. Use of highly cross-adsorbed secondary antibodies and shortening of the duration of the colorigenic reaction improved AT8-ir signal-to-noise ratio. We did not observe the same staining patterns with other mouse antibodies (AT180), suggesting that AT8 may recognize epitopes exposed during the LFPI injury and/or the resultant blood–brain barrier disruption.

Using a pTAU-Ser199/202 specific antibody, we confirmed higher pTAU-Ser199/202-ir 2 days after LFPI but also in sham rats compared to controls. Interestingly, we observed a pathological presence of pTAU-Ser199/202-ir in processes at the lateral cortex of most LFPI animals. Double staining identified such pTAU-Ser199/202-ir proximal processes as possibly dendritic, as they were labeled by MAP2. However, there were pTAU-Ser199/202-ir punctate or fibrillar structures that were not labeled by MAP2 or SMI35; further studies using electron microscopy would be needed to further characterize them.

Higher AT180-ir, both somatic (2 days, 2 weeks) and at ECM/processes (2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks), was seen at the parasagittal cortex ipsilaterally to the LFPI injury. Unlike AT8-ir, higher AT180-ir levels at the lateral cortex were seen at later time points (8 weeks), probably reflecting the injury evolution.

The effects of LFPI on PR55 were inconsistent, but PP2A activity was reduced in the perilesional LFPI cortex at 1 week. A prior study showed reduced PR55 expression and PP2A activity between 2 and 72 h post-LFPI (WB).20 This discrepancy may be the result of the different strains (Long–Evans in the study by Shultz and coworkers20 Sprague–Dawley here), or sampling effect given the intrinsic inter-animal heterogeneity of TBI pathologies, also demonstrated in the human specimens assessed for pTAU-Ser198 and PR55.20

SS is an oxidized form of selenium and a potent activator of PP2A,32,79 which improved pTAU pathologies and outcomes in other tauopathy models.20,32,33,61 SS potentiates the activity and expression of PP2A in AD patients and TBI models.20,21,32,34 We obtained different results when studying the SS effects on the somatic expression of pTAU-ir forms and PR55-ir by IHC as opposed to when using techniques that measure the overall changes of pTAU-ir, PR55-ir and PP2A activity in cortical extracts (WB and PP2A activity assays), which are a derivative not only of the cellular expression but also of the abundance of stained cells within the cell extract. The differences in results may therefore be reconciled, if SS1 had a greater effect in reducing the number of cells that overexpress pTAU-ir and increased the number of cells that express PP2A-ir in the cortical extracts. Alternatively, the differences may reflect the different sensitivities of the two methods. On the other hand, the lack of SS effect in IHC and the lack of correspondence between the dose and time-dependent effects of SS effects on AT8/TAU5 (both doses, 2 days and 1 week) and PR55 and PP2A activity (SS1 only, 2 days) in the WB and activity assays suggest that SS mechanisms beyond PP2A activation maybe involved. It is unclear why the effects of SS1 on PP2A/GAPDH and PP2A activity were observed at 2 days but not at 1 week (Fig. 9 K and L). Although a trend for higher plasma selenium, because of the SS treatment, was seen at 2 days rather than at 1 week (Table 3), this was not statistically significant. It is also possible that the low PP2A activity in LFPI rats, 1 week post-LFPI (Fig. 9 F), may have rendered the assay less sensitive in demonstrating SS-induced increases in PP2A activity (Fig. 9 L). In contrast, the apparent lower AT8-ir and higher PR55-ir and PP2A activity in cortical extracts in response to SS may be consistent with the previously reported reduction in the volume of cortical injury by SS, as suggested previously by Shultz and coworkers20 Candidate mechanisms include modification of other kinases,26 such as glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β), CDK5, and LRRK2, which phosphorylate Tau at Ser202/Thr205 (AT8 epitope).23,26,80–84 Anti-oxidant SS effects caused by the increased selenium (Table 3) that regulates selenoenzymes85–87 could also be involved. Indeed, mitochondrial oxidative stress mediated by amyloid-β (Aβ) may lead to Tau hyperphosphorylation.88–90

We cannot exclude that longer SS treatment may be needed to modify AT8-ir or AT180-ir cellular expression. SS ameliorated PTE, post-TBI lesion, and related affective and cognitive comorbidities in models of acquired epilepsy, if given immediately and continuously for a prolonged period of time after the epileptogenic insult.20,21,31,61 Prolonged SS administration (>12 weeks) generated long-lasting reduction of pTAU-Ser198 and pTAU-Ser262, even after 4 weeks of drug washout.20,31 Our data support some effectiveness of SS in modifying total pTAU expression in the cortical extracts in the WB studies only; however, the effect does not persist a week after SS is discontinued. The tolerability of both dose protocols of SS was, overall, good at both sites.

We observed more severe acute impairments (worse 2 day neuroscores, apnea, and return of pain response), but also earlier recovery of baseline neuroscores by the Melbourne rats by 8 weeks. Limitations of our study include the small number of rats per group and high variability within some of the experimental groups. Differences in site protocols, inter-experimenter variability, breeder-related genetic factors or environmental differences,54 or FPI device may also account for these differences.

Conclusion

This study provides concordant evidence from two laboratories for high pTAU levels in the rat LFPI model of TBI, and reports temporal, regional, and pTAU form-specific differences in pTAU and PP2A expression and activity in the perilesional cortex. We provide evidence for target relevance of pTAU in early (AT8, AT180) and late (AT180) post-LFPI pathologies supporting the consideration of administering treatments that reduce pTAU formation in this model, starting early after LFPI. One-week treatment with SS, a PP2A activator, did not modify any of the IHC measurements (somatic signal densitometry results of pTAU-ir forms or PR55), albeit it reduced AT8-ir pTAU (2 days and 1 week, both doses) and enhanced PP2A expression and activity (1 week, high dose only) in perilesional cortical extracts. The discordant effects of SS across the two laboratories and the different techniques (IHC, WB) might be reconciled if SS could reduce injury volume, as suggested by Shultz and coworkers,20 reducing the relative abundance of cells or structures (e.g., extracellular deposits) with increased pTAU-ir within the total volume of cortical extracts used in the WB or activity assays, without necessarily altering the mean somatic expression of pTAU-ir. Alternatively, the discordant results may indicate that other mechanisms of action should be considered, such as regulation of other kinases or antioxidative effects, which are also supported by the elevated selenium levels, or other mechanisms leading to lesion modification. Treatments with SS that are longer than 1 week could also be needed to observe the effects reported in the previous studies. The ongoing EpiBioS4Rx pre-clinical multi-center trial is therefore using a 12 week-treatment period with SS in the LFPI model to explore its therapeutic potential on post-LFPI pTAU pathologies and PTE.3 The possibility that the differences in SS effects in IHC compared with biochemical methods might be the result of SS-induced reduction in injury volume will be addressed in the pre-clinical antiepileptogenesis EpiBioS4Rx trial by tracking the SS effects on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-detected injury volume. Additional mechanisms of action of SS are considered in the biomarker studies to correlate with the response to SS and PTE development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the expert assistance of Dr. Kostantin Dobrenis (Albert Einstein College of Medicine) in obtaining the confocal microscope images of Figure 3. We acknowledge the technical assistance provided by Drs. Sheela Gnanapackiam and Shijie Liu for this study.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: for the EpiBioS4Rx Study Group

Authors' Contributions

P.G.S. collected the data at Einstein, prepared the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. P.M.C.E. collected the data at Melbourne, prepared the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. C.P.L. collected the data at Einstein, provided feedback for the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. W.B.M. performed the statistical analyses of the Einstein data and approved the final version of the manuscript. Q.L. and W.L. collected the data at Einstein and approved the final version of the manuscript. R.D.B., I.A., J.S., G.Y., M.H., C.L., and E.L.B. collected the data at Melbourne, provided feedback for the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. L.C. contributed to the planning and performance of the selenium and selenate measurements, provided the data in Figure 8, provided feedback for the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. J.C.C. contributed to the planning of the selenium and selenate measurements, provided feedback on the manuscript, and approved its final version. N.C.J. and S.R.S. contributed to the planning of the study, provided feedback for the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. S.L.M. contributed to the planning of the study, provided feedback for the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. T.J.O'B. contributed to the conceptualization and planning of the study, coordinated the Melbourne studies, provided feedback for the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. A.S.G. contributed to the conceptualization and planning of the study and data analyses, coordination of the Einstein studies, manuscript preparation, and final version of the manuscript, and approved the manuscript for its content.

Funding Information

The study was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stronke (NINDS) Center without Walls, U54 NS100064 (EpiBioS4Rx). J.C.C. was supported by NINDS/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) U54 NS065768, NINDS NS100064, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) R01 MH107394, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) R21 HD101075, and a research grant from Pfizer. S.R.S. was supported by a National Health and Medical Records Council (NHMRC) Career Development Fellowship (#APP1159645). S.L.M. is the Charles Frost Chair in Neurosurgery and Neurology and acknowledges grant support from NIH U54 NS100064 and NS43209, the United States Department of Defense (W81XWH-18-1-0612), the Heffer Family and the Segal Family Foundations, and the Abbe Goldstein/Joshua Lurie and Laurie Marsh/Dan Levitz families. T.J.O'B. was supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (#APP1176426). A.S.G. received grant support from NIH U54 NS100064, R01 NS091170, R01 NS127524, the United States Department of Defense (W81XWH-18-1-0612), an American Epilepsy Society seed grant, the Heffer Family and the Segal Family Foundations, and the Abbe Goldstein/Joshua Lurie and Laurie Marsh/Dan Levitz families. The Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope with Airyscan housed in Einstein's Neural Cell Engineering and Imaging Core was obtained through an NIH Shared Instrument Grant S10 OD025295 (Kostantin Dobrenis, Albert Einstein College of Medicine).

Author Disclosure Statement

J.C.C. received research support from Pfizer for a project unrelated to this study.

S.L.M. is serving as associate editor of Neurobiology of Disease. He is on the editorial board of Brain and Development, Pediatric Neurology, Annals of Neurology, MedLink, and Physiological Research. He receives annual compensation from Elsevier for his work as associate editor of Neurobiology of Disease; annual compensation from MedLink, and royalties from two books that he co-edited. T.J.O'B.'s institution has received funding and consultancy fees from Eisai, UCB, Biogen, Supernus, Praxis, ES Therapeutics, and Epiminder. A.S.G. is the editor-in-chief of Epilepsia Open, and associate editor of Neurobiology of Disease, and receives royalties from Elsevier (publications, journal editorial board participation), Medlink (publications), and Morgan and Claypool (publications). The other authors have no conflicts to report.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Bieniek KF, Cairns NJ, Crary JF, et al. The Second NINDS/NIBIB Consensus Meeting to Define Neuropathological Criteria for the Diagnosis of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2021;80(3):210–219; doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlab001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Piccenna L, Lannin NA, Scott K, et al. Guidance for community-based caregivers in assisting people with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury with transfers and manual handling: evidence and key stakeholder perspectives. Health Soc Care Community 2017;25(2):458–465; doi: 10.1111/hsc.12327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saletti PG, Ali I, Casillas-Espinosa PM, et al. In search of antiepileptogenic treatments for post-traumatic epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis 2019;123:86–99; doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M. Animal models of traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013;14(2):128–142; doi: 10.1038/nrn3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Englander J, Bushnik T, Wright JM, et al. Mortality in late post-traumatic seizures. J Neurotrauma 2009;26(9):1471–1477; doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uski J, Lamusuo S, Teperi S, et al. Mortality after traumatic brain injury and the effect of posttraumatic epilepsy. Neurology 2018;91(9):e878–e83; doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun M, Brady RD, van der Poel C, et al. A concomitant muscle injury does not worsen traumatic brain injury outcomes in mice. Front Neurol 2018;9:1089; doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ding K, Gupta PK, Diaz-Arrastia R.. Epilepsy after Traumatic Brain Injury. In: Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury. (Laskowitz D, Grant G, eds.) Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group; 2016. Chapter 14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pease M, Gonzalez-Martinez J, Puccio A, et al. Risk factors and incidence of epilepsy after severe traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol 2022;92(4):663–669; doi: 10.1002/ana.26443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ali I, Silva JC, Liu S, et al. Targeting neurodegeneration to prevent post-traumatic epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis 2019;123:100–109; doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hunt RF, Boychuk JA, Smith BN. Neural circuit mechanisms of post-traumatic epilepsy. Front Cell Neurosci 2013;7:89; doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klein P, Dingledine R, Aronica E, et al. Commonalities in epileptogenic processes from different acute brain insults: do they translate? Epilepsia 2018;59(1):37–66; doi: 10.1111/epi.13965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Semple BD, Zamani A, Rayner G, et al. Affective, neurocognitive and psychosocial disorders associated with traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis 2019;123:27–41; doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lifshitz J, Sullivan PG, Hovda DA, et al. Mitochondrial damage and dysfunction in traumatic brain injury. Mitochondrion 2004;4(5–6):705–713; doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Poudel GR, Dominguez DJ, Verhelst H, et al. Network diffusion modeling predicts neurodegeneration in traumatic brain injury. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2020;7(3):270–279; doi: 10.1002/acn3.50984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Semple BD, Bye N, Rancan M, et al. Role of CCL2 (MCP-1) in traumatic brain injury (TBI): evidence from severe TBI patients and CCL2-/- mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010;30(4):769–782; doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verweij BH, Muizelaar JP, Vinas FC, et al. Impaired cerebral mitochondrial function after traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurosurg 2000;93(5):815–820; doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.5.0815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Casillas-Espinosa PM, Ali I, O'Brien TJ. Neurodegenerative pathways as targets for acquired epilepsy therapy development. Epilepsia Open 2020;5(2):138–154; doi: 10.1002/epi4.12386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rubenstein R, Sharma DR, Chang BG, et al. Novel mouse tauopathy model for repetitive mild traumatic brain injury: evaluation of long-term effects on cognition and biomarker levels after therapeutic inhibition of tau phosphorylation. Front Neurol 2019;10:124; doi: ARTN 12410.3389/fneur.2019.00124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shultz SR, Wright DK, Zheng P, et al. Sodium selenate reduces hyperphosphorylated tau and improves outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Brain 2015;138(Pt 5):1297–1313; doi: 10.1093/brain/awv053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tan XL, Wright DK, Liu S, et al. Sodium selenate, a protein phosphatase 2A activator, mitigates hyperphosphorylated tau and improves repeated mild traumatic brain injury outcomes. Neuropharmacology 2016;108:382–393; doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buee L, Bussiere T, Buee-Scherrer V, et al. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33(1):95–130;doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tenreiro S, Eckermann K, Outeiro TF. Protein phosphorylation in neurodegeneration: friend or foe? Front Mol Neurosci 2014;7:42; doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee G, Leugers CJ. Tau and tauopathies. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2012;107:263–293; doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385883-2.00004-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morris M, Maeda S, Vossel K, et al. The many faces of tau. Neuron 2011;70(3):410–426; doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cho JH, Johnson GV. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta phosphorylates tau at both primed and unprimed sites. Differential impact on microtubule binding. J Biol Chem 2003;278(1):187–193; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206236200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thom M, Liu JY, Thompson P, et al. Neurofibrillary tangle pathology and Braak staging in chronic epilepsy in relation to traumatic brain injury and hippocampal sclerosis: a post-mortem study. Brain 2011;134(Pt 10):2969–2981; doi: 10.1093/brain/awr209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Janssens V, Goris J. Protein phosphatase 2A: a highly regulated family of serine/threonine phosphatases implicated in cell growth and signalling. Biochem J 2001;353(Pt 3):417–439; doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goedert M, Cohen ES, Jakes R, et al. p42 MAP kinase phosphorylation sites in microtubule-associated protein tau are dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 2A1. Implications for Alzheimer's disease [corrected]. FEBS Lett 1992;312(1):95–99; doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81418-l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, et al. Contributions of protein phosphatases PP1, PP2A, PP2B and PP5 to the regulation of tau phosphorylation. Eur J Neurosci 2005;22(8):1942–1950; doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu SJ, Zheng P, Wright DK, et al. Sodium selenate retards epileptogenesis in acquired epilepsy models reversing changes in protein phosphatase 2A and hyperphosphorylated tau. Brain 2016;139(Pt 7):1919–1938; doi: 10.1093/brain/aww116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Corcoran NM, Martin D, Hutter-Paier B, et al. Sodium selenate specifically activates PP2A phosphatase, dephosphorylates tau and reverses memory deficits in an Alzheimer's disease model. J Clin Neurosci 2010;17(8):1025–1033; doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Eersel J, Ke YD, Liu X, et al. Sodium selenate mitigates tau pathology, neurodegeneration, and functional deficits in Alzheimer's disease models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107(31):13,888–13,893; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009038107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malpas CB, Vivash L, Genc S, et al. A Phase IIa randomized control trial of VEL015 (sodium selenate) in mild-moderate Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;54(1):223–232; doi: 10.3233/JAD-160544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brady RD, Casillas-Espinosa PM, Agoston DV, et al. Modelling traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic epilepsy in rodents. Neurobiol Dis 2019;123:8–19; doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kharatishvili I, Immonen R, Grohn O, et al. Quantitative diffusion MRI of hippocampus as a surrogate marker for post-traumatic epileptogenesis. Brain 2007;130:3155–3168; doi: 10.1093/brain/awm268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]