Summary

Background

Rare cancers are those that exhibit an incidence of less than six per 100,000 in a year. On average, the five-year relative survival for patients with rare cancers is worse than those with common cancers. The traumatic experience of cancer can be further intensified in patients with rare cancers due to the limited clinical evidence and the lack of empirical evidence for informed decision-making. With rare cancers cumulatively accounting for up to 25% of all cancers, coupled with the rising burden of rare cancers on societies globally, it is necessary to determine the psychological outcomes of patients with rare cancers.

Methods

This PRISMA-adherent systematic review (PROSPERO: CRD42023475748) involved a systematic search of PubMed, Embase, Cochrane and PsycINFO for all peer-reviewed English language studies published since 2000 to 30th January 2024 that evaluated the prevalence, incidence and risk of depression, anxiety, suicide, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in patients with rare cancers. Two independent reviewers appraised and extracted the summary data from published studies. Random effects meta-analyses and meta-regression were used for primary analysis.

Findings

We included 32 studies with 57,470 patients with rare cancers. Meta-analyses indicated a statistically significant increased risk-ratio (RR) of depression (RR = 2.61, 95% CI: 1.43–4.77, I2 = 97%) and anxiety (RR = 2.66, 95% CI: 1.27–5.55, I2 = 92%) in patients with rare cancers compared to healthy controls. We identified a high suicide incidence (315 per 100,000 person-years, 95% CI: 162–609, I2 = 95%), prevalence of depression (17%, 95% CI: 14–22, I2 = 88%), anxiety (20%, 95% CI: 15–25, I2 = 96%) and PTSD (18%, 95% CI: 9–32, I2 = 25%). When compared to patients with common cancer types, suicide incidence, and PTSD prevalence were significantly higher in patients with rare cancers. Systematic review found that having advanced disease, chemotherapy treatment, lower income, and social status were risk factors for negative psychological outcomes.

Interpretation

We highlight the need for early identification of psychological maladjustment in patients with rare cancers. Additionally, studies to identify effective interventions are imperative.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Medical Research Council Transition Award, SingHealth Duke-NUS Oncology Academic Clinical Programme, the Khoo Pilot Collaborative Award, the National Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist-Individual Research Grant-New Investigator Grant, the Terry Fox Grant and the Khoo Bridge Funding Award.

Keywords: Rare, Neoplasms, Sarcoma, Mental health, Psychology

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We search PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cochrane from January 01, 2000 to January 31, 2024, for studies published in English, using the terms ‘rare cancers’, ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, ‘suicide’ and ‘PTSD’. Our search yielded 4281 results. Currently, there is strong evidence that patients diagnosed with common cancers such as breast and colorectal cancers face significantly increased risks of developing various psychological issues. Moreover, several cohort studies have described an increased risk of developing psychological issues amongst patients with rare cancers. However, there are no systematic reviews or meta-analyses that have evaluated these studies. There was also a lack of studies that directly compared patients with rare cancers to those with common cancers.

Added value of this study

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 57,470 patients with rare cancers across 32 studies. Our analyses showed that patients with rare cancers face significantly increased risk of developing anxiety and depression compared to healthy controls. We demonstrated a higher incidence of suicides and prevalence of PTSD amongst patients with rare cancers compared to patients with common cancers. Our study also identified specific risk factors for negative psychological outcomes such as having advanced disease, chemotherapy treatment, lower income, and social status in patients with rare cancers.

Implications of all the available evidence

Among healthcare providers, our findings call for heightened awareness of identifying those with psychological concerns. The significant prevalence of poor psychological well-being in patients with rare cancers highlights the critical need for early identification and intervention. The scarcity of individual rare cancer entities may render clinicians less attuned to the psychological challenges faced by such patients. Our study serves as a catalyst for increased vigilance and comprehensive care strategies, ensuring timely recognition and management of psychological issues within this niche patient population.

Introduction

According to the Surveillance of Rare Cancers in Europe (RARECARE) definition, rare cancers exhibit an incidence of less than six per 100,000 in a year.1 Despite the individual rarity of each entity, as a whole these cancers affect about one in four cancer patients.2 On average, the five-year relative survival for rare cancers is worse than that for common cancers.1 It is widely recognised that rare cancers, such as sarcoma, predominantly affect younger individuals, constituting approximately 21% of all paediatric solid malignant cancers and less than 1% of adult solid malignant cancers.3 This has a notable impact on the years of life lost, especially among young adults and adolescents.3 With the increasing incidence of cancer in the young who typically have a substantial portion of their expected lifespans ahead, there is a growing social and economic burden on societies.4 Collectively, rare cancers thus pose a significant challenge in societies globally.4

Coping with cancer presents an intricate and challenging journey for patients, their families, and the healthcare organisations tasked with delivering treatment and support.5 The distressing moment of receiving a cancer diagnosis and confronting subsequent treatment can instil concerns about disease recurrence or progression.6 The prevalence of psychological distresses, such as depression and anxiety, peaks significantly at the time of diagnosis amongst patients, and these effects endure throughout the continuum of treatment and into survivorship.7 Even post-treatment, a substantial portion of patients commonly experience symptoms that detrimentally affect various aspects of their quality-of-life, including sleep, physical functioning, and work capacity.8

The traumatic experience of cancer can be further intensified in patients with rare cancers. Identification of rare cancers often occurs at advanced stages, resulting in a poor prognosis.9 Clinicians, facing a scarcity of detailed knowledge and clinical expertise in rare cancers, contribute to significant delays in diagnosis.10 Moreover, managing rare cancers post-diagnosis presents challenges, requiring coordination among multiple specialists and lacking high quality clinical evidence for informed decision-making.9

With the rising demographic of patients with rare cancers of a younger age, the impact on their psychosocial well-being has been profound.2 Factors that exacerbate this, as compared to more common cancers which involve an older demographic, include having a longer timeframe of repercussions from diagnosis, as well as treatment-related side effects.2 The challenges that patients with rare cancers face also extend beyond their physical health. Many of these patients are also at their working age and potentially the breadwinner, resulting in financial instability due to impaired ability to work.11

Despite these obstacles, research on the occurrence of depression, anxiety, and other psychological outcomes in patients with rare cancers is limited due to the rarity of these cancer entities. Addressing this gap is crucial for developing comprehensive support and interventions for individuals navigating the intricate landscape of rare cancer diagnosis and treatment. This study is designed to primarily investigate the prevalence, incidence and risk of depression, anxiety, suicide, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) within the population of patients with rare cancers. Supplementary objectives include identifying specific patient characteristics that may significantly elevate their susceptibility to encountering these psychological burdens.

Methods

This systematic review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Search strategy and selection criteria

A literature search was conducted on Embase, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Cochrane. The search strategy included search terms for ‘rare cancers’, ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, ‘suicide’ and ‘PTSD’. Synonyms with truncations were used in the search for the keywords and the database-controlled subject headings. We translated the search strategy between the different databases. The full search strategies for PubMed and EMBASE are available in Supplementary Table S1. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all relevant studies. The studies deemed uncertain on initial screening were then independently evaluated by a third reviewer. We included peer-reviewed English language studies published since January 01, 2000–January 31, 2024 that investigated psychological outcomes in patients with rare cancers. We included all observational studies that aimed to assess at least one of the following as a key finding: The risk, prevalence, and incidence of depression, anxiety, suicide, and PTSD in patients with rare cancers. Prevalence and incidence were pooled for the single-arm studies and relative risk-ratio (RR) was pooled for the double-arm studies. Non-empirical studies, abstracts, grey literature, letters, case reports, and protocols were excluded. To ensure a comprehensive review, both manual-searching, and backward and forward reference searching were also conducted for the included studies.

Data analysis

Two independent reviewers extracted the data and assessed data quality. Subject matter information included demographics, types of cancer, the instruments and scales used to assess anxiety, depression, suicide, and PTSD, treatment modalities, the period of treatment and the main findings of the study. In studies with multiple timepoints, we utilised the time point with the highest number of events. The number of participants at risk and the number of events regarding their specific outcomes were extracted. In our review, patients with rare cancers are defined as any cancer diagnosis with an incidence of less than six per 100,000 in a year.1 PTSD is defined as an occurrence of a chronic impairment after exposure to traumatic events, causing disturbance in functioning.12 Reported depression, anxiety and PTSD must be tested using a validated instrument for patient-reported outcome measures or a clinical diagnosis by a registered practitioner.

Statistical analyses

We conducted the analyses using R (version 4.1.0) with the meta and metafor packages. Unless specified, a two-sided P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Metaprop was used in the meta-analysis of the prevalence under a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) model. The mixed model was specified using a random and fixed effect model. For dichotomous outcomes, meta-analyses were performed to compute the relative risk of the psychological outcome (measured using RR compared to controls). Where available, the controls were either healthy or patients with common cancers which were analysed individually. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using identifying and excluding potential outliers, random-effects, and leave-one-out analysis. To determine if any key hierarchical and categorical variables influenced the results, subgroup analyses and meta-regression were performed. The categories for the categorical variables were split based on an equal distribution to ensure methodological rigor and increase statistical power. Age was categorised based on the mean age of a cohort being either above or under 50 years old. Stage of treatment was categorised based on the timeframe at which patients were analysed, either before or after completing treatment. Cancer types were classified into sarcomas, carcinomas, and various. The chemotherapy treatments were divided based on whether less than or more than 50% of the group received chemotherapy, surgery treatments were divided based on whether less than or more than 75% of the group received surgery, and radiotherapy treatments were divided based on whether less than or more than 40% of the group received radiotherapy. As only a few single-arm studies reported data on incidence, the timepoint after the diagnosis of rare cancer was treated as prevalence data for analysis. Sensitivity analysis was then performed to ensure that prevalence data did not misrepresent the overall results.

Between-study heterogeneity was determined using I2 and τ2 statistics. I2 of >60% represented substantial heterogeneity between studies, 30%–60% demonstrated moderate heterogeneity, and <30% indicated low heterogeneity.13 We used Egger's test to assess for publication bias quantitatively. For qualitative bias, visual inspection for funnel plot asymmetry was used. When publication bias was suspected based on the funnel plot results, we conducted sensitivity analyses using the trim-and-fill method (fixed-random effects models and R0 estimator) to re-estimate the effect size after imputing potential studies.14,15 This was done by the removal of the asymmetric outliers from the funnel plot and the symmetric remainder of the funnel plot aids in approximating the final estimates of both the true mean and its variance.14 If publication bias was absent, we assume a normal distribution of effect sizes around the funnel plot's center.16

Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies were assessed using the Joanna Brigg's Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tool.17,18 Two independent reviewers performed the appraisal, and any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was not required as this study was a systematic review. The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023475748).

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. Informed consent was not required. All authors had access to the data from this study and are responsible for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

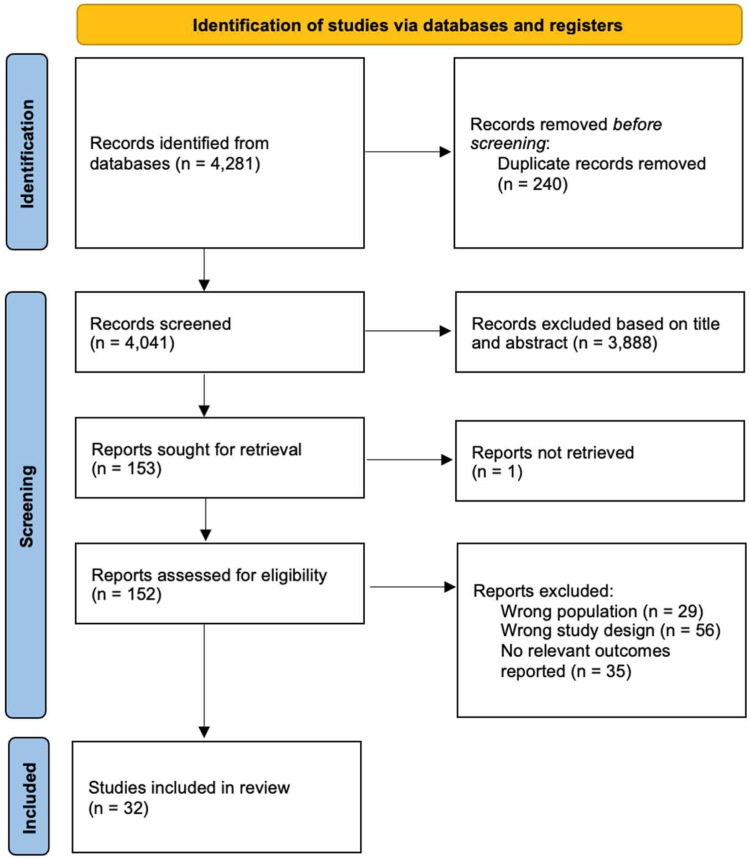

A total of 32 studies were included from 4281 records (Fig. 1). The remaining 4249 studies were excluded after removing irrelevant studies with the wrong study design or population and duplicates. 23 studies19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 investigated patients diagnosed with sarcoma, eight studies42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 investigated patients diagnosed with various rare cancers, while one study50 investigated patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma. 57,470 patients with rare cancers out of 1,287,082 participants were included. Main characteristics of the included studies are further described in Supplementary Table S2.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

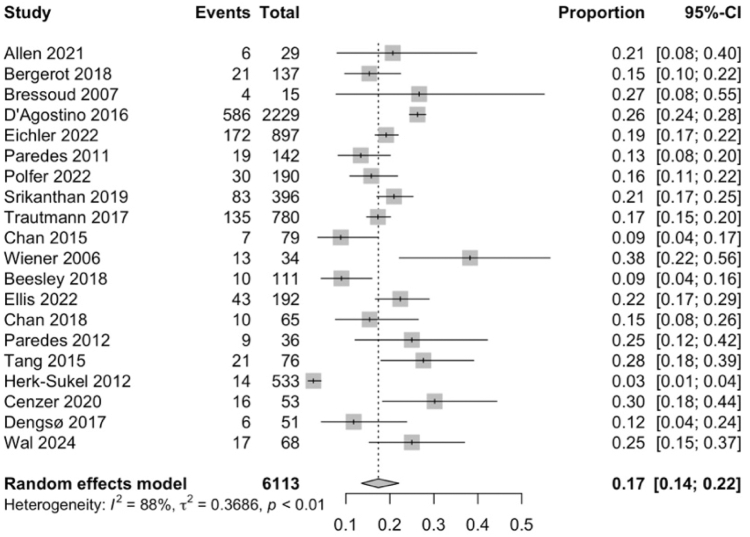

Prevalence of depression and anxiety

20 studies19,21, 22, 23,26, 27, 28,33, 34, 35, 36,38,41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47,50 were included to evaluate the prevalence of depression amongst patients with rare cancers. 1222 out of 6113 patients with rare cancers were assessed to have depression. Meta-analysis of the 20 studies (Fig. 2) indicated that depression was observed in 17% of patients with rare cancers (95% CI: 14–22). Subgroup analyses of the prevalence of depression among other categorical variables are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Overall, categorical variables such as age, gender, stage of treatment, type of cancer, and type of treatment were not found to significantly increase the prevalence of depression. Meta-regression did not reveal any significant variables (Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing that depression prevalence was 17% in patients with rare cancers. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

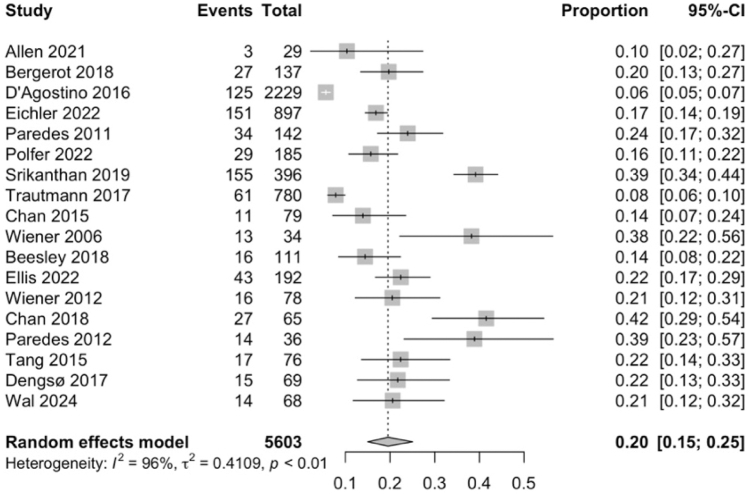

18 studies19,22,23,26, 27, 28,33, 34, 35,38,39,41, 42, 43,45, 46, 47,50 were included to evaluate the prevalence of anxiety amongst patients with rare cancers. 771 out of 5603 patients with rare cancers were assessed to have anxiety. Meta-analysis of the 18 studies (Fig. 3) indicated that anxiety was observed in 20% of patients with rare cancers (95% CI: 15–25). Subgroup analyses of the prevalence of anxiety among other categorical variables are listed in Supplementary Table S5. Overall, categorical variables such as age, gender, stage of treatment, type of cancer, and types of treatment were not found to significantly increase the prevalence of anxiety. Meta-regression did not report any significant variables (Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing that anxiety prevalence was 20% in patients with rare cancers. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

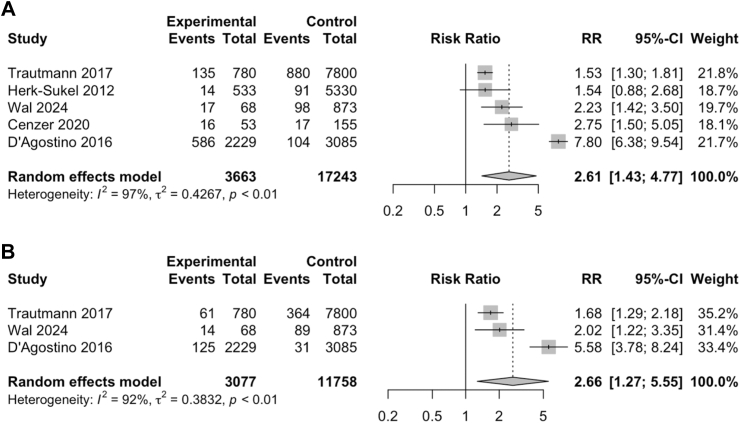

Relative risk ratios of depression and anxiety

Five studies35,36,41,44,46 were analysed to evaluate the relative risk of depression in patients with rare cancers. Meta-analysis of the five studies (Fig. 4A) indicated a statistically significant increased risk of depression in patients with rare cancers compared to the comparator arm (RR = 2.61, 95% CI: 1.43–4.77). Three studies35,41,46 were analysed to evaluate the relative risk of anxiety in patients with rare cancers. Meta-analysis of the three studies (Fig. 4B) indicated a statistically significant increased risk of anxiety in patients with rare cancers compared to the comparator arm (RR = 2.66, 95% CI: 1.27–5.55).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots showing the relative risk ratios of depression and anxiety in patients with rare cancers. (A) Depression risk ratio increased by 2.61 times compared to comparator. (B) Anxiety risk ratio increased by 2.66 times compared to comparator. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

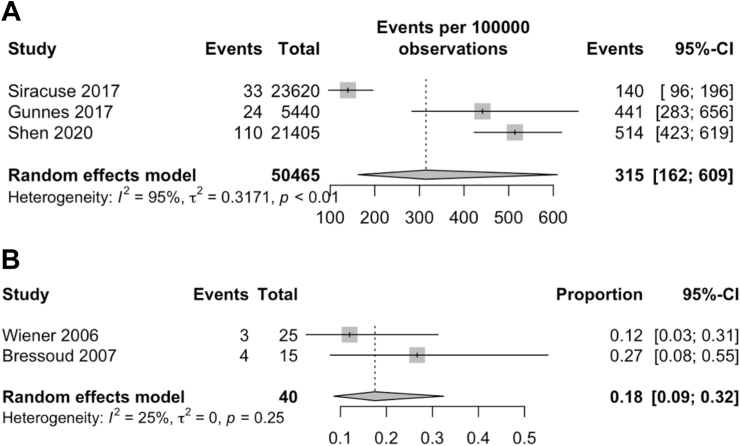

Suicide incidence and PTSD prevalence

Three studies31,32,48 were included to evaluate the incidence of suicide amongst patients with rare cancers. 167 out of 50,465 patients with rare cancers were found to have committed suicide. Meta-analysis of the three studies (Fig. 5A) indicated that the incidence of suicide was 315 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI: 162–609). Gunnes et al.48 retrospectively analysed 5440 individuals diagnosed with various rare cancers before the age of 25 as part of a nationwide study, with a suicide incidence of 24 per 100,000 person-years. Shen et al.31 retrospectively analysed 21,405 patients diagnosed with Kaposi's sarcoma without human immunodeficiency virus status as part of a nationwide study, with a suicide incidence of 115 per 100,000 person-years. Siracuse et al.32 retrospectively analysed 23,620 individuals diagnosed with primary bone and soft tissue cancers as part of a nationwide study, with a suicide incidence of 33 per 100,000 person-years.

Fig. 5.

Forest plots showing suicide incidence and anxiety prevalence in patients with rare cancers. (A) Suicide incidence was 315 events per 100,000 person-years. (B) PTSD prevalence was 18%. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Two studies21,38 were included to evaluate the prevalence of PTSD among patients with rare cancers. Seven out of 40 patients with rare cancers were assessed to have PTSD incidence. Meta-analysis of the two studies (Fig. 5B) indicated that PTSD was observed in 18% of patients with rare cancers (95% CI: 0.09–0.32). Wiener et al.38 recruited 34 survivors of paediatric sarcoma, with an average of 18 years since diagnosis. Bressoud et al.21 recruited 15 long-term survivors of osteosarcoma, with an average of 11 years since diagnosis.

Pre-existing mental illness

Two studies20,27 examined the relationship between pre-existing psychological statuses and psychological outcomes in patients with rare cancers (Supplementary Table S6). Both studies reported a significant association between having pre-existing psychological disturbances and an increased severity of anxiety and depression after a rare cancer diagnosis.

Financial status

Four studies23,38,46,47 explored the association between financial status and psychological outcomes in patients with rare cancers (Supplementary Table S7). Three studies23,38,47 indirectly reported a significant association between financial status and psychological outcomes. The studies found that being unemployed or having a disability pension were significantly associated with higher levels of distress and worse depressive symptoms. One study46 directly reported a significant correlation between an annual income of less than $19,999 and psychological outcomes.

Social status

Three studies20,27,46 reported on the association between social status and psychological outcomes in patients with rare cancers (Supplementary Table S8). Benedetti et al.20 reported a significant association between unmarried patients and having lower mental well-being. D'Agostino et al.46 reported a significant association between divorcees and having higher levels of distress. Interestingly, Paredes et al.27 reported a significant association between being married and having greater severity of depression during treatment.

Physical health

Two studies46,47 explored the association between the physical health of patients with rare cancers and their psychological outcomes (Supplementary Table S9). Both studies reported that comorbidities or poor health were associated with worse depressive symptoms.

Disease and treatment factors

Seven studies23,28,31,37,43,47,48 reported on the association between disease status, treatment modality and disease symptoms on the psychological outcomes of patients with rare cancers (Supplementary Table S10). Four studies23,43,47,48 demonstrated significant associations between the status of the rare cancer and psychological outcomes. Two out of the four studies reported a significant association between having a more severe cancer diagnosis or symptoms with worse depression, quality-of-life and distress.23,37,43 The other two studies47,48 found worse psychological outcomes among survivors and those in remission. Two studies28,31 demonstrated significant associations between chemotherapy and worse psychological outcomes. Interestingly, Shen et al.31 found a significant association between patients receiving chemotherapy and a decreased risk of suicide.

Risk of bias, publication bias and sensitivity analyses

The quality of the methodology of the 32 studies was scored with the JBI checklist and presented in Supplementary Table S11. Overall, some risk of bias was identified. Sensitivity analyses using funnel plots, trim-and-fill, and Egger's test showed some publication bias (Supplementary Figures S1–S4 and S6–S9). However, leave-one-out analyses reported that there were no singular studies that affected the overall results (Supplementary Figures S5 and S10).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence, incidence and risk of depression, anxiety, suicide, and PTSD in patients with rare cancers. Our study found a statistically significant increased risk of depression and anxiety in patients with rare cancers compared to healthy controls. We also identified a statistically high suicide incidence, prevalence of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Systematic review found that having advanced disease, chemotherapy treatment, lower income, and social status were significant risk factors for negative psychological outcomes.

As there were no studies that directly compared the psychological outcomes of patients with rare cancers and patients with common cancers, we referenced the literature and indirectly compared the prevalence and incidence of these outcomes among patients with common cancers and also the general population (Table 1). We note that the prevalence of depression and anxiety was elevated in patients with rare cancers when compared to the general population and slightly lower when compared to common cancers such as breast and colorectal cancer.

Table 1.

Comparison of the prevalence and incidence of depression, anxiety, suicide, and PTSD among various population groups.

| Author | Year | Country of study | Population | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | ||||

| Nikbakhsh et al.51 | 2014 | Iran | Patients with breast cancer | 19.56 |

| Mols et al.52 | 2018 | Netherlands | Patients with colorectal cancer | 19 |

| Johansson et al.53 | 2013 | Sweden | General population | 17.2 |

| Anxiety | ||||

| Nikbakhsh et al.51 | 2014 | Iran | Patients with breast cancer | 17.39 |

| Mols et al.52 | 2018 | Netherlands | Patients with colorectal cancer | 20.9 |

| Johansson et al.53 | 2013 | Sweden | General population | 14.7 |

| Suicide Incidence (Expressed as events per 100,000 observations) | ||||

| Misono et al.54 | 2008 | United States | General population | 16.7 |

| Misono et al.54 | 2008 | United States | Patients with breast cancer | 70.4 |

| Misono et al.54 | 2008 | United States | Patients with colorectal cancer | 165 |

| Misono et al.54 | 2008 | United States | Patients with lung cancer | 168 |

| Turaga et al.55 | 2010 | United States | Patients with pancreatic cancer | 135a |

| Yu et al.56 | 2020 | United States | Patients with leukaemia | 26.4a |

| Osazuwa-Peters et al.57 | 2018 | United States | Patients with head and neck cancers | 23.6a |

| PTSD | ||||

| Lewis et al.58 | 2019 | United Kingdom | General population | 7.8 |

| Swartzman et al.59 | 2016 | United Kingdom | Patients with breast cancer | 10.0 |

| Swartzman et al.59 | 2016 | United Kingdom | Patients with colorectal cancer | 4.3 |

| Swartzman et al.59 | 2016 | United Kingdom | Patients with prostate cancer | 9.8 |

| Varela et al.60 | 2011 | United States | Patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma | 13 |

| Goncalves et al.61 | 2011 | United Kingdom | Patients with ovarian cancer | 13 |

Incidence.

Colorectal and breast cancers are typically associated with an aggressive nature and propensity for rapid progression, leading to elevated anxiety and depression levels.47 Concerns of body image after mastectomy exacerbate anxiety in breast cancer patients, while older age in colorectal cancer patients correlates with increased anxiety and depression, likely due to extended duration of disease and heightened disability rates.48 In contrast, patients diagnosed with rare cancers often fall within the younger age demographic,1 with them having a lower risk of developing anxiety and depression.49 Being younger may be associated with a greater participation in cancer support groups amongst the young, thus allowing them to learn more about their illness and share concerns with other patients.62

Despite this, suicide incidence and PTSD prevalence are elevated in patients with rare cancers when compared to both the general population and in patients with common cancers. Patients with rare cancers encounter significant challenges, especially as distinct symptoms in the early stages contribute to the overall difficulties.26 In metastatic and refractory sarcoma, the prognosis remains unfavourable, with a median survival of only 12–18 months.63 The absence of specific symptoms often leads to delayed diagnosis and treatment, intensifying existing challenges.63 Furthermore, the physical side effects of some treatments, such as disfigurement and functional impairment, worsen the overall impact on patients' quality-of-life.63 Throughout the disease course, individuals with rare cancers grapple with significant psychological effects stemming from the uncertainty of prognosis and the adverse consequences of aggressive treatments.26

The high incidence of suicide and PTSD prevalence in patients with rare cancers may be predisposed by the high prevalence of depression and anxiety in this population. Anxiety and depression are linked to intense negative emotions such as those associated with suicidal tendencies.64 Factors such as social isolation, disability, and reductions in quality-of-life due to psychological burden may contribute to a diminished sense of purpose for individuals in this population.65 Moreover, patients with anxiety and depression often experience reduced social support, a crucial protective factor against suicide.66 The adoption of avoidant coping strategies, common in anxiety disorders, has also been identified as a risk factor for suicide.67 Additionally, the coexistence of depression and anxiety significantly increases the likelihood of suicide attempts.68 The enduring stigma surrounding mental health issues further complicates the situation, leading cancer patients to avoid acknowledging their psychological problems. Without timely and adequate treatment, anxiety can escalate into post-traumatic stress disorder.67

Although our meta-analyses did not reveal that age was a significant factor, it is noteworthy that patients with rare cancers often fall within the younger age demographics.1 This characteristic while distinct from the more prevalent cancers, has its own set of challenges. Younger patients with rare cancers may have a longer life expectancy which allows for an extended timeframe to navigate the emotional and psychological repercussions of their diagnosis.69 This extended timeframe also presents unique challenges to younger patients with rare cancers who are in the growing stage of their lives, impacting their social engagement, educational participation, and future family planning.70 Future research should therefore investigate the effects of age on the mental health outcomes of patients with rare cancers.

In the context of PTSD, the younger age of patients with rare cancers can also contribute to a prolonged and potentially more intense cancer experience. Research indicates that younger individuals facing cancer may have a longer bandwidth of time to measure PTSD compared to their older counterparts.71 The extended duration may be attributed to factors such as ongoing treatment regimens, a higher possibility of experiencing treatment-related side effects or facing more aggressive therapeutic interventions.71 In contrast, older cancer patients with more common cancers may be more inclined to opt for less aggressive treatments, potentially sparing them from some of the psychological distress associated with more rigorous therapeutic approaches.72

Our study also revealed significant correlations between specific demographic factors and heightened vulnerability to psychological outcomes. Having a lower income and social status were found to be significant risk factors for negative psychological outcomes. These factors were found to be consistent in the international literature.73 Our results emphasise the importance of proactive surveillance strategies and targeted resource allocation to effectively mitigate the psychological burden faced by these individuals.

Psychological outcomes were also influenced by both disease and treatment-related factors. Patients with rare cancers with advanced disease faced increased vulnerability to negative psychological outcomes. Those with advanced disease or those who went through chemotherapy treatment were identified as risk factors for negative psychological outcomes.74,75 For individuals with advanced disease, the psychological impact may stem from the awareness of the severity of their condition, the uncertainty of prognosis and the potential implications for their quality-of-life.76 Those who had undergone chemotherapy often face both the physical side-effects of treatment and also the emotional toll of having to navigate a challenging and intense intervention.77 It is important to integrate mental health support into the overall care plan for patients with advanced stage disease or those undergoing chemotherapy. Healthcare providers should be attuned to the emotional well-being of these individuals, offering not only medical interventions but also psychological support and resources to help them cope with any challenges that they may face.77

Our study should be interpreted with due consideration of certain limitations. Firstly, there was high heterogeneity in the reporting of outcomes. There were insufficient studies with control-arm, and data on suicide and PTSD were available for three studies each. Among those studies with a control-arm, there were only five studies for depression and three for anxiety. Hence, the resulting data on RR may not be representative and should be interpreted with prudence. The type of rare cancer was also different for some studies, further contributing to this heterogeneity. Due to the heterogeneity across different social contexts, we were unable to perform subgroup meta-analyses for variables such as pre-existing mental illness, financial status, social status, physical health, disease, and treatment factors. Nonetheless, we were still able to systematically review those factors. We also did not obtain individual patient data for our meta-analysis as the available data was insufficient to study individual risk factors affecting the psychological outcomes. However, we were still able to analyse the key characteristics in the subgroups that we planned for, including age, gender, stage of treatment, type of cancer, and types of treatment. Secondly, as many of the studies are based on patient-reported outcome measures, suicide-related behaviours are less likely to be reported due to social stigma.78 This could have led to an underrepresentation of the group and potentially caused the prevalence of suicide to be lower than the actual number. Thirdly, there were no double-arm studies that directly compared the mental health outcomes of patients with rare cancers against patients with common cancers. We therefore indirectly compared our pooled single-arm prevalence results against other single-arm studies in the literature that investigated those outcomes among patients with common cancers. Future studies should attempt to directly compare those pertinent outcomes using patients with common cancers as the comparator arm.

In conclusion, our study highlights an increased susceptibility to depression, anxiety, suicide incidence and PTSD within patients with rare cancers, surpassing rates observed in other common cancers. Notably, factors such as disease stage, chemotherapy, and socioeconomic status are significant contributors to adverse psychological outcomes. We emphasise the critical imperative for early detection and increased support for this vulnerable group. Urgent interventions and further research are warranted to elucidate additional risk and protective factors to devise targeted strategies to alleviate the burden of depression and anxiety in these vulnerable individuals.

Contributors

CEL contributed to study conceptualisation, formal analysis, investigation, statistical analysis, and writing the original draft of the manuscript. SL, GEP and BS contributed equally to formal analysis, investigation and writing the original draft of the manuscript. VSY contributed to conceptualisation, visualisation, supervision and editing of the manuscript. All authors had access to and verified the data used in this study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data sharing statement

Data used in this study are available in a public, open-access repository. The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Medical Research Council Transition Award (TA20nov-0020), SingHealth Duke-NUS Oncology Academic Clinical Programme (08/FY2020/EX/67-A143 and 08/FY2021/EX/17-A47), the Khoo Pilot Collaborative Award (Duke-NUS-KP(Coll)/2022/0020A), the National Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist-Individual Research Grant-New Investigator Grant (CNIGnov-0025), the Terry Fox Grant (I1056) and the Khoo Bridge Funding Award (Duke-NUS-KBrFA/2024/0083I).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102631.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Gatta G., van der Zwan J.M., Casali P.G., et al. Rare cancers are not so rare: the rare cancer burden in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(17):2493–2511. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Heus E., van der Zwan J.M., Husson O., et al. Unmet supportive care needs of patients with rare cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2021;30(6) doi: 10.1111/ecc.13502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burningham Z., Hashibe M., Spector L., Schiffman J.D. The epidemiology of sarcoma. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2012;2(1):14. doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fidler M.M., Gupta S., Soerjomataram I., Ferlay J., Steliarova-Foucher E., Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20–39 years worldwide in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(12):1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downe-Wamboldt B., Butler L., Coulter L. The relationship between meaning of illness, social support, coping strategies, and quality of life for lung cancer patients and their family members. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(2):111–119. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch L., Jansen L., Brenner H., Arndt V. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥ 5 years) cancer survivors--a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psycho Oncol. 2013;22(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/pon.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niedzwiedz C.L., Knifton L., Robb K.A., Katikireddi S.V., Smith D.J. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: a growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):943. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nayak M.G., George A., Vidyasagar M.S., et al. Quality of life among cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23(4):445–450. doi: 10.4103/ijpc.Ijpc_82_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeSantis C.E., Kramer J.L., Jemal A. The burden of rare cancers in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(4):261–272. doi: 10.3322/caac.21400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keat N., Law K., Seymour M., et al. International rare cancers initiative. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(2):109–110. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mor V., Allen S., Malin M. The psychosocial impact of cancer on older versus younger patients and their families. Cancer. 1994;74(S7):2118–2127. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941001)74:7+<2118::AID-CNCR2820741720>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miao X.R., Chen Q.B., Wei K., Tao K.M., Lu Z.J. Posttraumatic stress disorder: from diagnosis to prevention. Mil Med Res. 2018;5(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40779-018-0179-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters J.L., Sutton A.J., Jones D.R., Abrams K.R., Rushton L. Performance of the trim and fill method in the presence of publication bias and between-study heterogeneity. Stat Med. 2007;26(25):4544–4562. doi: 10.1002/sim.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munn Z., Barker T.H., Moola S., et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2127–2133. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-d-19-00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munn Z., Moola S., Riitano D., Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(3):123–128. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen J.M., Niel K., Guo A., Su Y., Zhang H., Anghelescu D.L. Psychosocial factors and psychological interventions: implications for chronic post-surgical pain in pediatric patients with osteosarcoma. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2021;28(3):468–476. doi: 10.1007/s10880-020-09748-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benedetti M.G., Tarricone I., Monti M., et al. Psychological well-being, self-esteem, quality of life and gender differences as determinants of post-traumatic growth in long-term knee rotationplasty survivors: a cohort study. Children. 2023;10(5):867. doi: 10.3390/children10050867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bressoud A., Real del Sarte O., Stiefel S., et al. Impact of family structure on long-term survivors of osteosarcoma. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(5):525–531. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan A., Lim E., Ng T., Shih V., Quek R., Cheung Y.T. Symptom burden and medication use in adult sarcoma patients. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(6):1709–1717. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eichler. 35 Deutscher Krebskongress, Krebsmedizin: Schnittstellen zwischen Innovation und Versorgung, 13.–16. November 2022, Berlin. Oncol Res Treat. 2022;45(Suppl. 3):6–285. doi: 10.1159/000521004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H., Gao X., Hou Y. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction combined with music therapy on pain, anxiety, and sleep quality in patients with osteosarcoma. Braz J Psychiatry. 2019;41(6):540–545. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palm R.F., Jim H.S.L., Boulware D., Johnstone P.A.S., Naghavi A.O. Using the revised Edmonton symptom assessment scale during neoadjuvant radiotherapy for retroperitoneal sarcoma. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2020;22:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2020.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paredes T., Canavarro M.C., Simões M.R. Anxiety and depression in sarcoma patients: emotional adjustment and its determinants in the different phases of disease. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paredes T., Pereira M., Simões M.R., Canavarro M.C. A longitudinal study on emotional adjustment of sarcoma patients: the determinant role of demographic, clinical and coping variables. Eur J Cancer Care. 2012;21(1):41–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polfer E.M., Alici Y., Baser R.E., Healey J.H., Bartelstein M.K. What proportion of patients with musculoskeletal sarcomas demonstrate symptoms of depression or anxiety? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2022;480(11):2148–2160. doi: 10.1097/corr.0000000000002295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranft A., Seidel C., Hoffmann C., et al. Quality of survivorship in a rare disease: clinicofunctional outcome and physical activity in an observational cohort study of 618 long-term survivors of ewing sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15):1704–1712. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.70.6226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saebye C., Amidi A., Keller J., Andersen H., Baad-Hansen T. Changes in functional outcome and quality of life in soft tissue sarcoma patients within the first year after surgery: a prospective observational study. Cancers. 2020;12(2):463. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen J., Zhu M., Li S., et al. Incidence and risk factors for suicide death among kaposi's sarcoma patients: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26 doi: 10.12659/msm.920711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siracuse B.L., Gorgy G., Ruskin J., Beebe K.S. What is the incidence of suicide in patients with bone and soft tissue cancer? : suicide and sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(5):1439–1445. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-5171-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srikanthan A., Leung B., Shokoohi A., Smrke A., Bates A., Ho C. Psychosocial distress scores and needs among newly diagnosed sarcoma patients: a provincial experience. Sarcoma. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/5302639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang M.H., Castle D.J., Choong P.F.M. Identifying the prevalence, trajectory, and determinants of psychological distress in extremity sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/745163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trautmann F., Singer S., Schmitt J. Patients with soft tissue sarcoma comprise a higher probability of comorbidities than cancer-free individuals. A secondary data analysis. Eur J Cancer Care. 2017;26(6) doi: 10.1111/ecc.12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Herk-Sukel M.P., Shantakumar S., Overbeek L.I., van Boven H., Penning-van Beest F.J., Herings R.M. Occurrence of comorbidities before and after soft tissue sarcoma diagnosis. Sarcoma. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/402109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weidema M.E., Husson O., van der Graaf W.T.A., et al. Health-related quality of life and symptom burden of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma patients: a global patient-driven Facebook study in a very rare malignancy. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(8):975–982. doi: 10.1080/0284186x.2020.1766696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiener L., Battles H., Bernstein D., et al. Persistent psychological distress in long-term survivors of pediatric sarcoma: the experience at a single institution. Psycho Oncol. 2006;15(10):898–910. doi: 10.1002/pon.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiener L., Battles H., Zadeh S., Smith C.J., Helman L.J., Kim S.Y. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: psychosocial characteristics and considerations. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(6):1343–1349. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1426-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yonemoto T., Kamibeppu K., Ishii T., Iwata S., Hagiwara Y., Tatezaki S. Psychosocial outcomes in long-term survivors of high-grade osteosarcoma: a Japanese single-center experience. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(10):4287–4290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van de Wal D., den Hollander D., Desar I.M.E., et al. Fear, anxiety and depression in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patients in the Netherlands: data from a cross-sectional multicenter study. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2024;24(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2023.100434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beesley V.L., Burge M., Dumbrava M., Callum J., Neale R.E., Wyld D.K. Perceptions of care and patient-reported outcomes in people living with neuroendocrine tumours. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(9):3153–3161. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergerot C.D., Bergerot P.G., Philip E.J., et al. Assessment of distress and quality of life in rare cancers. Psycho Oncol. 2018;27(12):2740–2746. doi: 10.1002/pon.4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cenzer I., Berger K., Rodriguez A.M., Ostermann H., Covinsky K.E. Patient-reported measures of well-being in older multiple myeloma patients: use of secondary data source. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(6):1153–1160. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01465-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan A., Poon E., Goh W.L., et al. Assessment of psychological distress among Asian adolescents and young adults (AYA) cancer patients using the distress thermometer: a prospective, longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(9):3257–3266. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4189-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D'Agostino N.M., Edelstein K., Zhang N., et al. Comorbid symptoms of emotional distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3215–3224. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellis S., Brown R.F., Thorsteinsson E.B., Pakenham K.I., Perrott C. Quality of life and fear of cancer recurrence in patients and survivors of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Psychol Health Med. 2022;27(8):1649–1660. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1913756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gunnes M.W., Lie R.T., Bjørge T., et al. Suicide and violent deaths in survivors of cancer in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood-A national cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(3):575–580. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zaid T., Burzawa J., Basen-Engquist K., et al. Use of social media to conduct a cross-sectional epidemiologic and quality of life survey of patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: a feasibility study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(1):149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elberg Dengsø K., Hillingsø J., Marcussen A.M., Thomsen T. Health-related quality of life and anxiety and depression in patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):198–204. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1266088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikbakhsh N., Moudi S., Abbasian S., Khafri S. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients. Caspian J Intern Med. 2014;5(3):167–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mols F., Schoormans D., de Hingh I., Oerlemans S., Husson O. Symptoms of anxiety and depression among colorectal cancer survivors from the population-based, longitudinal PROFILES Registry: prevalence, predictors, and impact on quality of life. Cancer. 2018;124(12):2621–2628. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johansson R., Carlbring P., Heedman Å., Paxling B., Andersson G. Depression, anxiety and their comorbidity in the Swedish general population: point prevalence and the effect on health-related quality of life. PeerJ. 2013;1 doi: 10.7717/peerj.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Misono S., Weiss N.S., Fann J.R., Redman M., Yueh B. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4731–4738. doi: 10.1200/jco.2007.13.8941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turaga K.K., Malafa M.P., Jacobsen P.B., Schell M.J., Sarr M.G. Suicide in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(3):642–647. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu H., Cai K., Huang Y., Lyu J. Risk factors associated with suicide among leukemia patients: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. Cancer Med. 2020;9(23):9006–9017. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osazuwa-Peters N., Simpson M.C., Zhao L., et al. Suicide risk among cancer survivors: head and neck versus other cancers. Cancer. 2018;124(20):4072–4079. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lewis S.J., Arseneault L., Caspi A., et al. The epidemiology of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in a representative cohort of young people in England and Wales. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(3):247–256. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(19)30031-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swartzman S., Booth J.N., Munro A., Sani F. Posttraumatic stress disorder after cancer diagnosis in adults: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(4):327–339. doi: 10.1002/da.22542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varela V.S., Ng A., Mauch P., Recklitis C.J. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in survivors of Hodgkin's lymphoma: prevalence of PTSD and partial PTSD compared with sibling controls. Psycho Oncol. 2013;22(2):434–440. doi: 10.1002/pon.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gonçalves V., Jayson G., Tarrier N. A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with ovarian cancer. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(5):422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bauman L.J., Gervey R., Siegel K. Factors associated with cancer patients' participation in support groups. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1992;10(3):1–20. doi: 10.1300/J077V10N03_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Franzoi I.G., Granieri A., Sauta M.D., et al. The psychological impact of sarcoma on affected patients. Psycho Oncol. 2023;32(12):1787–1797. doi: 10.1002/pon.6240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stein D., Apter A., Ratzoni G., Har-Even D., Avidan G. Association between multiple suicide attempts and negative affects in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(5):488–494. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199805000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mendlowicz M.V., Stein M.B. Quality of life in individuals with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):669–682. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gunnell D., Harbord R., Singleton N., Jenkins R., Lewis G. Factors influencing the development and amelioration of suicidal thoughts in the general population. Cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:385–393. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.5.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Amir M., Kaplan Z., Efroni R., Kotler M. Suicide risk and coping styles in posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1999;68(2):76–81. doi: 10.1159/000012316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bronisch T., Wittchen H.U. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: comorbidity with depression, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;244(2):93–98. doi: 10.1007/bf02193525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Botta L., Dal Maso L., Guzzinati S., et al. Changes in life expectancy for cancer patients over time since diagnosis. J Adv Res. 2019;20:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boman K.K., Bodegård G. Life after cancer in childhood: social adjustment and educational and vocational status of young-adult survivors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26(6):354–362. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200406000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee Y.-L., Santacroce S.J. Posttraumatic stress in long-term young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(8):1406–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seghers P.A.L., Wiersma A., Festen S., et al. Patient preferences for treatment outcomes in oncology with a focus on the older patient—a systematic review. Cancers. 2022;14(5):1147. doi: 10.3390/cancers14051147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mutyambizi C., Booysen F., Stornes P., Eikemo T.A. Subjective social status and inequalities in depressive symptoms: a gender-specific decomposition analysis for South Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-0996-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grotmol K.S., Lie H.C., Hjermstad M.J., et al. Depression—a major contributor to poor quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(6):889–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wen S., Xiao H., Yang Y. The risk factors for depression in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(1):57–67. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moos R.H., Schaefer J.A. In: Coping with physical illness: 2: new perspectives. Moos R.H., editor. Springer US; 1984. The crisis of physical illness; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Witham G., Haigh C., Foy S. The challenges of health professionals in meeting the needs of vulnerable patients undergoing chemotherapy: a focus group study. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(19-20):2844–2853. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oexle N., Waldmann T., Staiger T., Xu Z., Rüsch N. Mental illness stigma and suicidality: the role of public and individual stigma. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(2):169–175. doi: 10.1017/s2045796016000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.