Summary

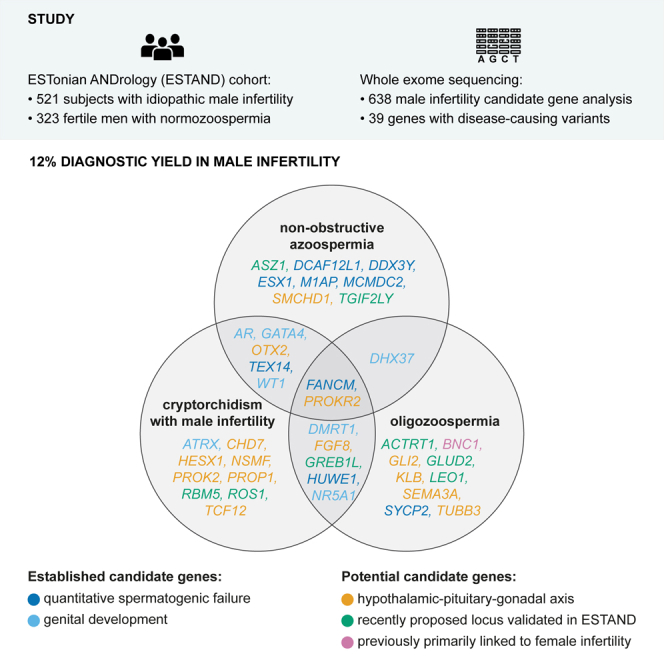

Infertility, affecting ∼10% of men, is predominantly caused by primary spermatogenic failure (SPGF). We screened likely pathogenic and pathogenic (LP/P) variants in 638 candidate genes for male infertility in 521 individuals presenting idiopathic SPGF and 323 normozoospermic men in the ESTAND cohort. Molecular diagnosis was reached for 64 men with SPGF (12%), with findings in 39 genes (6%). The yield did not differ significantly between the subgroups with azoospermia (20/185, 11%), oligozoospermia (18/181, 10%), and primary cryptorchidism with SPGF (26/155, 17%). Notably, 19 of 64 LP/P variants (30%) identified in 28 subjects represented recurrent findings in this study and/or with other male infertility cohorts. NR5A1 was the most frequently affected gene, with seven LP/P variants in six SPGF-affected men and two normozoospermic men. The link to SPGF was validated for recently proposed candidate genes ACTRT1, ASZ1, GLUD2, GREB1L, LEO1, RBM5, ROS1, and TGIF2LY. Heterozygous truncating variants in BNC1, reported in female infertility, emerged as plausible causes of severe oligozoospermia. Data suggested that several infertile men may present congenital conditions with less pronounced or pleiotropic phenotypes affecting the development and function of the reproductive system. Genes regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis were affected in >30% of subjects with LP/P variants. Six individuals had more than one LP/P variant, including five with two findings from the gene panel. A 4-fold increased prevalence of cancer was observed in men with genetic infertility compared to the general male population (8% vs. 2%; p = 4.4 × 10−3). Expanding genetic testing in andrology will contribute to the multidisciplinary management of SPGF.

Keywords: monogenic infertility, azoospermia, oligozoospermia, cryptorchidism, exome sequencing, gene panel, molecular diagnostics, diagnostic yield, oligogenic, infertility management

Graphical abstract

The study screened exomes of 521 infertile men for causative variants in 638 candidate genes. It reported 12% diagnostic yield, including recurrent variants and oligogenicity in male infertility; validated eight recently proposed male infertility genes, identified BNC1 truncating variants to cause oligozoospermia, and showed increased cancer risk in genetic infertility.

Introduction

Failure to conceive a child affects 5%–10% of men and is predominantly caused by quantitative spermatogenic failure (SPGF, total sperm count ≤39 × 106 per ejaculate1). Today, >50% of subjects with SPGF remain idiopathic, and therefore, efficient and timely infertility management cannot always be delivered. Although genetic factors are considered a key etiology behind SPGF, the current clinical guidelines recommend testing only for chromosomal abnormalities, Y chromosome microdeletions, and variants in CFTR (MIM: 602421) linked to obstructive azoospermia that cumulatively account for ∼10% of male infertility.2 Studies performing whole-exome sequencing (WES) on male infertility cohorts have proposed hundreds of candidate genes and variants for SPGF.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 The added value of these findings in improving patient management, reproductive counseling, and decision making in routine clinical practice is to be clarified.12,13,14

This study aimed to screen likely pathogenic (LP) and pathogenic (P) variants in 486 male infertility candidate genes using WES data generated for 844 Estonian men, including 521 individuals with idiopathic SPGF and 323 normozoospermic individuals (Figure S1). As the critical role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis in the development and regulation of the male reproductive system is well established15 and shared etiology of genetic causes of SPGF and premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) have been documented,14 we additionally analyzed 73 HPG axis and 79 POI-linked genes. This is a comprehensive in silico gene panel-based study, screening a total of 638 candidate loci for male infertility. The study included a broad distribution of male factor infertility phenotypes—185 individuals with non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) and 181 with oligozoospermia (OZ), as well as 155 subjects with a primary diagnosis of cryptorchidism (CR) accompanied by SPGF. This enabled more generalizable conclusions from the outcomes and evaluation of their translational potential and value in clinical practice.

Subjects and methods

Ethics statement

The study of the ESTonian ANDrology (ESTAND) cohort was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Human Research of the University of Tartu, Estonia (permission 74/54 and 118/69 with last amendment 288/M-13; 221/T-6, last amendment 286/M-18). The study of the Barcelona cohort of infertile men was approved by the ethics committee of Fundació Puigvert, Spain (2014/04c). Written informed consent for evaluating and using their clinical data for scientific purposes was obtained from each person before recruitment. The study was carried out in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Recruitment and andrological phenotyping of the ESTAND cohort

All study participants were recruited to the nationwide ESTAND cohort,2 and the material was collected at the Andrology Clinic of Tartu University Hospital (AC-TUH), Estonia. All study subjects had undergone identical routine andrological workup2 following standard protocols at the AC-TUH. All participants were of white European ancestry and living in Estonia.

SPGF was defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.1 NOA refers to a complete lack of sperm in the ejaculate due to primary SPGF (Table S1). OZ corresponds to the total sperm count >0 and ≤39 × 106, and normozoospermia to >39 × 106 sperm per ejaculate. Men presenting NOA or OZ with at least one testicle missing in the scrotum at the recruitment or medical history of CR (orchidopexy or spontaneous descent) were diagnosed with congenital CR. Details about physical examination, semen and hormonal analyses, and histological profiling are available in supplemental methods.

Formation of the study group for WES

The total number of ESTAND cohort participants subjected to WES was 844 (Table S1). Men with idiopathic SPGF (n = 521, median age 34 years at the recruitment) were prioritized to WES based on their unexplained extreme clinical phenotype suggestive of a possible monogenic cause. Data considered in the cohort formation included azoospermia, extremely low sperm count, abnormal hormonal parameters, reduced total testis volume (TTV), CR, and hypospadias. Complete andrological and other available health records of included subjects were assessed and discussed. Individuals diagnosed with known genetic and non-genetic causal factors of male infertility1,2 were excluded (supplemental methods). The final SPGF study group was subdivided into three clinical subgroups based on their primary diagnosis: 185 men with NOA, 181 men with OZ (median sperm count 2.0 × 106 per ejaculate), and 155 men presenting CR and SPGF (either NOA or OZ).

Normozoospermic men (n = 323; median sperm count 303.1 × 106 per ejaculate; median age 31 years) recruited during an ongoing pregnancy were used as control subjects.2,16 Sperm quality parameters (motility and morphology) and time to pregnancy were not considered exclusion/inclusion criteria for the control group. Therefore, it may include men with other forms of male (sub)infertility apart from quantitative SPGF, which was the focus of this study.

WES data generation

WES data generation was performed in three sequencing centers: the Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM), Helsinki, Finland (n = 447 DNA samples); the McDonnell Genome Institute of Washington University in St. Louis, MO, USA (n = 82); and the Huntsman Cancer Institute High-Throughput Genomics Core Facility at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, UT, USA (n = 315) (supplemental methods).

Processing of VCF files, variant annotation, and filtering

All sample VCF files generated in the three sequencing service centers were filtered for quality. Variants with low depth of coverage (DP < 10) and low genotype quality (GQ < 20) were excluded. VCF files were annotated with Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP; v.105)17 using the flags and plugins listed in Table S2.

Custom filters were applied to the annotated VEP files to filter out unlikely variants for monogenic infertility (Table S3). Only missense, frameshift, stop-gained (nonsense), stop/start-lost, and splice region/acceptor/donor variants of the canonical transcript were considered with minor allele frequency ≤1% in the gnomAD (v.2.1.1) database across all subjects. The applied filters excluded known likely benign (LB) and benign (B) variants (e.g., based on ClinVar records18) and variants with a low probability of being causative to a monogenic condition (CADD < 10, SIFT: benign, PolyPhen: tolerated). The variants that passed all the criteria were considered for further analysis.

The list of 638 candidate genes

The formed in silico gene panel included 156 genes linked to male infertility in medical genetics databases and reported in more than one independent study (Table S4), 330 candidate genes from single studies reporting variants causing male infertility (Table S5), 73 genes implicated in HPG axis irrespective of their previous links to male infertility (Table S6), and 79 loci that, so far, have primarily been implicated in POI (Table S7). The core list of 156 male infertility genes was further subdivided based on their primary action—implicated in quantitative spermatogenesis (n = 80 genes), qualitative spermatogenesis (n = 37), or genital development (n = 39).

Filtering and prioritization of variants

VEP output files were subjected to custom-designed automatic exclusion of variants with an unlikely disease-causing effect (Table S3), followed by implementation of the open access AI-based interpretation engine Franklin by Genoox for variant pathogenicity predictions. Variants predicted by this platform as LP, P, or variants of uncertain significance (VUS) were included in the final manual assessment performed in parallel by two researchers. All manually analyzed variants passed a visual quality inspection using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software.19 Pathogenicity of retained variants was assessed according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines.20 In addition, we considered recent literature and database records, as well as data collected during this study, e.g., clinical and pedigree information gathered from medical records and during the follow-up assessment (22 subjects with confident findings, 33%; supplemental methods) or recurrent rare variants identified in more than one individual.

All 66 men with LP/P variants identified in the candidate gene panel underwent extended analysis across all genes in the WES dataset to identify further variants that may contribute to their phenotype. In all instances with more than one LP/P finding, the significance of the digenic pathogenicity was tested using the Oligogenic Resource for Variant AnaLysis (ORVAL; v.3.0.0) platform.21

All variants were validated by Sanger sequencing (supplemental methods, Table S8; Figures S2–S7).

External validation of the link between BNC1 loss-of-function variants and SPGF

The Fundació Puigvert (Barcelona, Spain) male infertility cohort was used for a targeted lookup for loss-of-function (LoF) variants in the SPGF candidate gene BNC1 (MIM: 601930). The cohort consisted of 129 men with SPGF and has been previously described by Riera-Escamilla et al.11 (supplemental methods).

Additional data sources

Gene expression levels in distinct testicular cell types in six adult control men were derived from the human testis single-cell RNA sequencing dataset, available through the human infertility single-cell testis atlas (HISTA; v.2.9.6).22

Data on health comorbidities in Estonian men aged 40–49 years was derived from the national public health project (https://tai.ee/et/valjaanded/eesti-40-49aastaste-meeste-tervis-pilootprojekt-pikema-sopruse-paev in Estonian; supplemental methods).

Results

Disease-causing variants in 39 candidate genes detected in 66 study subjects

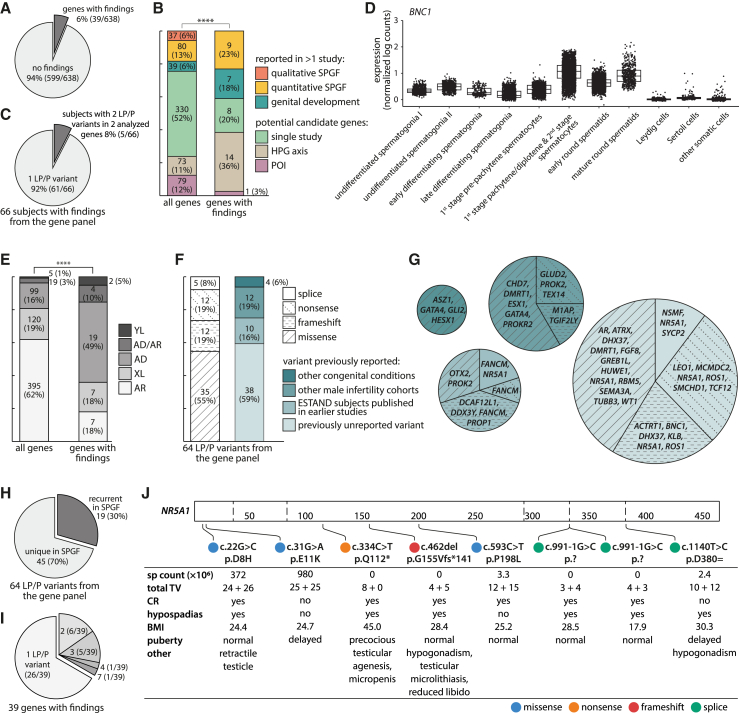

LP/P variants were identified in 39 of 638 (6%) analyzed genes, including 24 male infertility candidate genes (of 486 in the panel, 5%), 14 genes contributing to the HPG axis (of 73, 19%), and one POI-linked gene (of 79, 1%) (Figure 1A; Tables S9 and S10–S12). Genes regulating the HPG axis were ∼3-fold enriched among the loci with identified LP/P variants compared to their representation in the gene panel (36% vs. 11%; Fisher’s exact test, p = 1.2 × 10−4; Figure 1B). The total number of different LP/P variants was 64 (38 previously unreported, 59%) identified in 66 study subjects, including 64 individuals with SPGF and two normozoospermic men (Figure 1C). Five men with SPGF had LP/P variants in two genes in the analyzed gene panel (Figures S3 and S4; Table S11).

Figure 1.

Likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants in 638 candidate genes identified in 521 men with spermatogenic failure and 323 normozoospermic men in the ESTAND cohort

(A) Proportion of genes with findings in the analyzed panel.

(B) Distribution of genes with LP/P variants according to the gene category. Fisher’s exact test, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001.

(C) Singleton and digenic LP/P findings from the analyzed gene panel.

(D) Cell-type-specific testicular expression (normalized log counts) of BNC1 from the human single-cell testis atlas (HISTA).22

(E) LP/P variants according to the previously reported inheritance mode. Fisher’s exact test, ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001.

(F) Stratification of LP/P variants by molecular consequence and novelty.

(G) Genes with findings grouped by molecular consequence and novelty.

(H) Distribution of unique and recurrent LP/P variants.

(I) Number of LP/P variants identified per gene.

(J) Genotype-phenotype data of the identified NR5A1 LP/P variants.

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; BMI, body mass index; CR, cryptorchidism; ESTAND, ESTonian ANDrology; HPG, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal; LP, likely pathogenic; P, pathogenic; POI, primary ovarian insufficiency; sp, sperm; SPGF, spermatogenic failure; TV, testis volume; XL, X-linked; YL, Y-linked.

This study validated phenotype-genotype links for eight recently proposed SPGF candidate genes3,4,9,10,11 (2% of 330 genes; Table S5). Independent findings in the ESTAND cohort confirmed the relevance to male infertility for GREB1L10 (MIM: 617782), LEO110 (MIM: 610507) and RBM510 (MIM: 606884) (autosomal dominant [AD]), ASZ13 (MIM: 605797) and ROS13 (MIM: 165020) (autosomal recessive [AR]), ACTRT14 (MIM: 300487) and GLUD211 (MIM: 300144) (X-linked [XL]), and TGIF2LY9 (MIM: 400025) (Y-linked [YL]) (Tables 1 and S13). TGIF2LY (GenBank: NM_139214.3) (c.534_535del [p.Leu179Serfs∗63]) (phenotype NOA) and GLUD2 (GenBank: NM_012084.4) (c.412C>T [p.Gln138∗]) (NOA,11 OZ in this study) were identical LoF variants to previous reports.

Table 1.

Disease-causing variants identified in male infertility candidate genes proposed in a single study or primarily linked to POI

|

Variant dataa |

Subject datab |

Literature data |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene cDNA, protein change (zygosity) | rs number MAF | Age (y) |

H (cm) W (kg) BMI |

Total sperm count ×106 |

TV (mL) L + R total |

FSH (IU/L) LH (IU/L) T (nmol/L) |

Other relevant clinical data | Reported phenotype in the discovery study |

|

ACTRT1 (NM_138289.4) c.547dup (p.Met183Asnfs∗17) (hemi) |

previously unreported | 45 | N/A | 3.0 | 15 + 15 30 |

31.7 12.7 31.6 |

N/A | missense in NOA, severe OZ4 |

|

ASZ1 (NM_130768.3) c.460A>G (p.Met154Val) (hom)c |

rs186384831 1.3 × 10−4 |

35 | 176 78 25.1 |

0 | 17 + 16 33 |

16.8 6.3 16.8 |

hypospermatogenesis, maturation arrest | missense in NOA, severe OZ3 |

|

BNC1 (NM_001717.4) c.621_637del (p.Phe207Leufs∗5) (het) |

previously unreported | 31 | 182 95 28.6 |

2.4 | 15 + 12 27 |

22.9 13.8 22.2 |

N/A | LoF in POI23 |

|

GLUD2 (NM_012084.4) c.412C>T (p.Gln138∗) (hemi) |

rs140532390 4.9 × 10−4 |

25 | 180 71 22.0 |

31.2 | 14 + 15 29 |

10.1 7.8 8.2 |

N/A | recurrent variant previously reported in NOA (SCOS)11 |

|

GREB1L (NM_001142966.3) c.23A>C (p.Gln8Pro) (het) |

rs1212136611 1.3 × 10−4 |

35 | 180 82 25.6 |

1.3 | 11 + 13 24 |

31.5 11.6 10.4 |

hypospermatogenesis, primary spermatocyte sloughing | LoF in NOA10 |

|

GREB1L (NM_001142966.3) c.311C>T (p.Pro104Leu) (het) |

rs1254264958 6.5 × 10−5 |

55 | 179 98 30.6 |

0 | 7 + 0 7 |

34.9 14.2 10.1 |

CR (unilateral), testicular cancer | LoF in NOA10 |

|

LEO1 (NM_138792.4) c.607C>T (p.Gln203∗) (het) |

previously unreported | 29 | 189 92 25.0 |

4.4 | 18 + 19 37 |

20.7 8.5 7.8 |

N/A | missense in severe oligoasthenozoospermia10 |

|

RBM5 (NM_005778.4) c.217G>A (p.Glu73Lys) (het) |

rs201956265 N/A |

52 | 184 100 29.5 |

0 | 0 + 40 40 |

9.2 3.5 18.8 |

CR (unilateral, untreated) | missense in NOA, severe OZ, CR, low TV10 |

|

ROS1 (NM_001378902.1) c.5588dup (p.Ile1864Asnfs∗15), c.3611T>A (p.Leu1204∗) (both het) |

rs1257346590, rs35302901 N/A, 9.9 × 10−4 |

33 | N/A | 7.6 | 18 + 4 22 |

22.0 14.0 18.8 |

CR (unilateral) | missense in NOA, severe OZ3 |

|

TGIF2LY (NM_139214.3) c.534_535del (p.Leu179Serfs∗63) (hemi) |

rs760614599 8.0 × 10−4 |

40 | 178 90 28.2 |

0 | 11 + 10 21 |

30.7 10.3 9.4 |

N/A | recurrent variant previously reported in NOA9 |

BMI, body mass index; CR, cryptorchidism; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; H, height; hemi, hemizygous; het, heterozygous; hom, homozygous; L, left; LH, luteinizing hormone; LoF, loss-of-function; N/A, not available; NOA, non-obstructive azoospermia; OZ, oligozoospermia; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; R, right; SCOS, Sertoli cell-only syndrome; T, testosterone; TV, testis volume; W, weight; y, years.

hg38; minor allele frequency (MAF) based on gnomAD v.2.1.1 for non-Finnish Europeans; additional data on each variant and phenotype in the ESTAND participant, and references to original studies and previously reported variants are provided in Tables S10, S12, and S13

Clinical data at the time of recruitment

Variant previously reported in ClinVar

Among the genes previously linked primarily to POI, BNC1 emerged as a potential candidate gene for male infertility. BNC1 (GenBank: NM_001717.4) (c.621_637del [p.Phe207Leufs∗5]) truncating variant was identified in an infertile ESTAND participant (Table 1). The link between SPGF and BNC1 was externally validated in the Fundació Puigvert (Barcelona, Spain) male infertility cohort. BNC1 (GenBank: NM_001717.4) (c.1874_1875del [p.Pro625Argfs∗12]) change was detected in one affected Spanish individual (Table S12; Figure S5). Both men with BNC1 frameshift variants presented severe OZ (sperm count 2.4 × 106 and 4.2 × 106 per ejaculate, respectively). BNC1 encodes the transcription regulator basonuclin 1, which is highly expressed in pachytene stage spermatocytes and spermatids (Figure 1D).

Consistent with the clinical profile of the study group, no pathogenic genotypes were identified in the 37 genes linked to qualitative sperm defects. Heterozygous (het) truncating variants in SEPTIN12 (MIM: 611562) (previously linked to AD SPGF10) (MIM: 614822) were identified in two normozoospermic men with fully normal sperm motility and morphology, as well as a successful natural conception (Figure S6). These results did not support the haplosensitivity of SEPTIN12.

A significant ∼10-fold overrepresentation of affected genes linked to AD compared to AR conditions was observed relative to the composition of the gene panel (19 of 99, 19% vs. 7 of 395, 2% analyzed genes; Fisher’s exact test, p = 2.4 × 10−9; Figure 1E). The representation of missense (n = 35) and LoF (n = 29) variations among the identified LP/P variants was not significantly different (Figure 1F).

A high overall proportion of recurrently detected LP/P variants in male infertility genes

Overall, 19 of 64 LP/P variants (30%; eight LoF, 11 missense) identified in 28 ESTAND SPGF-affected individuals represented recurrent findings detected in more than one unrelated individual when considering this study and previous reports in the literature (Figures 1G and 1H; Tables 1, 2, 3, and S14). This included 12 variants reported in other male infertility cohorts9,11,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 and seven ESTAND cohort-specific variants. Among genes implicated in spermatogenesis, M1AP (MIM: 619098) (GenBank: NM_001321739.2) (c.676dup [p.Trp226Leufs∗4]) (homozygous [hom]) detected in an ESTAND subject with Sertoli cell-only syndrome (SCOS) (Figure S7) has been previously reported in eight European men with meiotic or maturation arrest (hom or compound het).29 Other examples of previously reported NOA-linked recurrent variants identified in the ESTAND participants were TEX14 (MIM: 605792) (GenBank: NM_031272.5) (c.1003C>T [p.Arg335∗]) (hom; SCOS) and ESX1 (MIM: 300154) (GenBank: NM_153448.4) (c.1094C>G [p.Pro365Arg]) (XL; NOA).27

Table 2.

Disease-causing variants identified in genes implicated in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis

|

Variant dataa |

Subject datab |

Other genotype-phenotype data |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene cDNA, protein change (zygosity) | rs number MAF | Age (y) |

H (cm) W (kg) BMI |

Total sperm count ×106 |

TV (mL) L + R total |

FSH (IU/L) LH (IU/L) T (nmol/L) |

Other relevant clinical data | Recurrent variant in this study | Phenotype in the literature |

|

CHD7 (NM_017780.4) c.6194G>A (p.Arg2065His) (het)c |

rs1197494895 N/A |

27 | 176 80 25.7 |

3.1 | 8 + 16 24 |

2.4 3.7 3.5 |

CR (untreated), tertiary adrenal insufficiency, severe hypogonadism | no | CHH, anosmia, CR, delayed puberty25 |

|

HESX1 (NM_003865.3) c.326G>A (p.Arg109Gln) (het)c |

rs768165720 1.9 × 10−6 |

CPHD32,33 | |||||||

|

FGF8 (NM_033163.5) c.290T>C (p.Leu97Pro) (het) |

rs537681304 7.8 × 10−6 |

26 | 180 83 25.5 |

0 | 18 + 24 42 |

4.7 9.3 12.0 |

CR (uni, op. in childhood), gingivitis, personality disorder | yes | N/A |

|

FGF8 (NM_033163.5) c.290T>C (p.Leu97Pro) (het) |

rs537681304 7.8 × 10−6 |

22 | 179 131 40.7 |

0.02 | 24 + 23 47 |

10.1 4.2 12.8 |

situs inversus, total urinary incontinence, hypertension, type 2 diabetes | yes | N/A |

|

GLI2 (NM_001374353.1) c.1253A>G (p.Tyr418Cys) (het)c |

rs759585885 2.3 × 10−5 |

50 | 177 81 25.9 |

1.5 | 8 + 12 20 |

21.5 7.3 16.1 |

multiple joint operations | yes | GLI2-related conditions |

|

GLI2 (NM_001374353.1) c.1253A>G (p.Tyr418Cys) (het)c |

rs759585885 2.3 × 10−5 |

27 | 189 86 24.2 |

21.0 | 9 + 11 20 |

19.3 11.1 16.8 |

mucocele, nasal cysts | yes | GLI2-related conditions |

|

KLB (NM_175737.4) c.2676del (p.Ile892Metfs∗16) (het) |

previously unreported | 44 | 172 71 24.1 |

0.02 | 15 + 20 35 |

13.5 11.0 31.7 |

radiculopathy, thrombosis | no | N/A |

|

NSMF (NM_001130969.3) c.710+1G>A (het) |

rs923607827 5.0 × 10−5 |

37 | 182 100 30.2 |

0 | 15 + 27 47 |

10.4 5.0 12.2 |

CR (uni, op. at 15 years), insulin-independent diabetes, hypertension | no | N/A |

|

OTX2 (NM_021728.4) c.425C>G (p.Pro142Arg) (het)c |

rs199761861 3.1 × 10−4 |

50 | 181 104 31.7 |

0 | 5 + 5 10 |

13.7 8.4 3.2 |

SCOS, severe hypogonadism, duodenal ulcer, liver cysts, hypertension, frequent infections, depression; family history of hereditary cancer and early mortality | yes | CPHD, microphthalmia34 |

|

OTX2 (NM_021728.4) c.425C>G (p.Pro142Arg) (het)c |

rs199761861 3.1 × 10−4 |

18 | 165 49 17.9 |

0 | 4 + 3 7 |

35.6 11.1 18.6 |

CR (bil, op. in childhood), severe penoscrotal hypospadias, preterm birth due to premature placental aging; family history of infertility and genital dysgenesis35 | yes | CPHD, microphthalmia34 |

| Primary variant35: NR5A1 (NM_004959.5) c.991−1G>C (het) |

rs2131277756 N/A |

N/A | |||||||

| no | |||||||||

|

PROK2 (NM_001126128.2) c.313C>T (p.His105Tyr), c.122G>A (p.Gly41Asp) (both het) |

rs201632855, rs200922174 N/A, 1.2 × 10−4 |

22 | 175 106 34.4 |

0 | 16 + 16 32 |

25.1 9.4 16.2 |

CR (bil, op. twice in childhood), early puberty, reduced libido, testicular microlithiasis, short arms, brachydactyly, joint hypermobility, obesity, mild hearing impairment (one ear), depression (since 20 years), germ cell neoplasia in situ; family data: Figure 2C | no | N/A |

| Incidental finding: KMT2D (NM_003482.4) c.16051C>T (p.Arg5351Trp) (het) |

rs940848278 4.1 × 10−6 |

||||||||

|

PROK2 (NM_001126128.2) c.163del (p.Ile55∗) (het)c |

rs554675432 2.6 × 10−4 |

36d | 180 83 25.6 |

0 | 17 + 9 26 |

27.3 13.8 13.6 |

CR (uni, op. in puberty), SCOS, microphthalmia (one eye), anxiety, chronic fatigue, premature birth; mother (het): GERD, obesity; sister: three kidneys | no | CHH, anosmia, CR, NOA, absent or delayed puberty, low TV, micropenis, gynecomastia31 |

|

PROKR2 (NM_144773.4) c.253C>T (p.Arg85Cys) (het)c |

rs141090506 3.7 × 10−4 |

49 | 173 106 35.3 |

0 | 12 + 13 25 |

8.4 4.5 4.7 |

severe hypogonadism, obesity; ART: one child; sister: lymphoma, early death; father: heart disease | no | CHH, anosmia, micropenis, hypodontia30 |

|

PROKR2 (NM_144773.4) c.254G>A (p.Arg85His) (het)c |

rs74315418 1.2 × 10−3 |

31 | 171 79 26.9 |

3.1 | 13 + 9 22 |

24.8 10.4 12.1 |

short limbs, mild anemia; ART: one child with abdominal epilepsy, dental abnormalities, dysarthria, educational impairment; half-sister (mat): obesity, thyroid issues; nephew: educational impairment | yes | CHH, anosmia, delayed puberty, CR, sleep disorder, bimanual synkinesia24 |

|

PROKR2 (NM_144773.4) c.254G>A (p.Arg85His) (het)c |

rs74315418 1.2 × 10−3 |

40 | 185 79 23.1 |

6.0 | 26 + 8 34 |

29.3 9.3 24.7 |

CR (left: spont. descent, right: op. 11 years), aortic defect (op. 4 years), multinodular goiter (op.), hypothyroidism, sleep, and anxiety disorders; brother (55 years): childless, one miscarriage; mother: thyroid disease, impaired thermoregulation | yes | CHH, anosmia, delayed puberty, CR, sleep disorder, bimanual synkinesia24 |

|

PROKR2 (NM_144773.4) c.868C>T (p.Pro290Ser) (het)c |

rs149992595 1.6 × 10−4 |

29 | 174 70 23.1 |

0.3 | 14 + 15 29 |

33.1 4.5 15.6 |

asthma, mildly impaired thermoregulation; ART: one child; sister (45 years), two cousins (>40 years), uncle (mat, d. 72 years): childless; father: prostate cancer | no | CHH, anosmia, CR, micropenis24 |

| Other finding: FANCM (NM_020937.4) c.5101C>T (p.Gln1701∗) (hom) |

rs147021911 1.0 × 10−3 |

yes (see Table 3) | NOA,36 POI,37 breast cancer38 | ||||||

|

SEMA3A (NM_006080.3) c.1450C>T (p.Arg484Trp) (het) |

rs756204489 7.4 × 10−5 |

25 | 186 86 24.9 |

16.0 | 25 + 23 48 |

1.1 2.8 11.1 |

low gonadotropin levels | no | N/A |

|

SMCHD1 (NM_015295.3) c.2656C>T (p.Arg886∗) (het) |

rs201632358 6.6 × 10−6 |

25 | 169 72 25.3 |

0 | 8 + 5 13 |

32.7 8.3 7.7 |

SCOS | no | N/A |

|

TCF12 (NM_207037.2) c.314C>A (p.Ser105∗) (het) |

previously unreported | 22 | 180 65 20.0 |

8.5 | 20 + 0 20 |

17.3 9.8 25.1 |

CR (uni, right testis removed due to atrophy at 8 years) | no | N/A |

|

TCF12 (NM_207037.2) c.1597C>T (p.Gln533∗) (het) |

previously unreported | 44 | 186 155 44.8 |

0 | 20 + 16 36 |

29.2 15.6 14.4 |

CR (uni, op. at 7 years), bariatric surgery | no | N/A |

|

TUBB3 (NM_006086.4) c.953G>A (p.Arg318Gln) (het) |

previously unreported | 43 | 183 83 24.8 |

2.2 | 11 + 13 24 |

17.1 9.8 6.0 |

kidney transplant due to a nephrotic syndrome | no | N/A |

ART, assisted reproductive technology; bil, bilateral; BMI, body mass index; CHH, congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism; CPHD, combined pituitary hormone deficiency; CR, cryptorchidism; d., died; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; H, height; het, heterozygote; hom, homozygous; L, left; LH, luteinizing hormone; mat, maternal; N/A, not available; NOA, non-obstructive azoospermia; op., operated; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; R, right; SCOS, Sertoli cell-only syndrome; spont., spontaneous; T, testosterone; TV, testis volume; uni, unilateral; W, weight; y, years.

hg38; minor allele frequency (MAF) based on gnomAD v.2.1.1 for non-Finnish Europeans; additional data on each variant and phenotype in the ESTAND participant and references to previously reported variants are provided in Tables S10 and S11

Clinical data at the time of recruitment, unless noted otherwise

Variant previously reported in ClinVar

Data from the follow-up interview

Table 3.

Recurrent disease-causing variants previously reported in other male infertility cohorts or identified in multiple unrelated Estonian men

|

Variant dataa |

Subject datab |

Other genotype-phenotype data |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene, cDNA, protein change (zygosity) |

rs number MAF |

Age (y) |

H (cm) W (kg) BMI |

Total sperm count ×106 |

TV (mL) L + R total |

FSH (IU/L) LH (IU/L) T (nmol/L) |

Other relevant clinical data | Recurrent variant in this study | Phenotype in the literature |

|

DMRT1 (NM_021951.3) c.425C>T (p.Ala142Val) (het) |

rs767829750 8.8 × 10−6 |

23 | 175 75 24.5 |

7.0 | 13 + 16 29 |

13.8 5.3 17.6 |

hernias, brain cysts, hypertension | no | NOA (SCOS), reduced TV26 |

|

ESX1 (NM_153448.4) c.1094C>G (p.Pro365Arg) (hemi) |

rs782108131 7.4 × 10−5 |

52 | 172 73 24.5 |

0 | 7 + 5 12 |

62.6 31.8 6.4 |

N/A | no | NOA (SCOS), reduced TV27 |

|

FANCM (NM_020937.4) c.1491dup (p.Gln498Thrfs∗7) (hom)c |

rs797045116 N/A |

28 | 185 79 23.1 |

0 | 13 + 13 26 |

17.9 10.5 10.9 |

hypospadias (glans) | yes | N/A |

|

FANCM (NM_020937.4) c.1491dup (p.Gln498Thrfs∗7)c, c.4387−10A>G (chet) |

rs797045116, rs1555365959 N/A, N/A | 29 | 187 84 24.1 |

0 | 10 + 12 22 |

16.0 4.1 14.8 |

SCOS, seminiferous tubule atrophy and sclerosisd | yes (p.Gln498Thrfs∗7) | N/A |

|

FANCM (NM_020937.4) c.1491dup (p.Gln498Thrfs∗7)c, c.4387−10A>G (chet) |

rs797045116, rs1555365959 N/A, N/A | 26 | 190 85 23.5 |

0 | 14 + 16 30 |

31.0 9.6 14.1 |

SCOS, CR (spontaneous descent by 1 year)d | yes (p.Gln498Thrfs∗7) | N/A |

|

FANCM (NM_020937.4) c.5101C>T (p.Gln1701∗) (hom)c |

rs147021911 1.0 × 10−3 |

58 | 180 85 26.1 |

0 | 9 + 10 19 |

42.3 18.6 5.8 |

myocardial infarction | yes (see Table 2) | N/A |

|

GATA4 (NM_001308093.3) c.487C>T (p.Pro163Ser) (het)c |

rs387906769 4.4 × 10−5 |

29 | 166 107 38.8 |

0.9 | 16 + 18 34 |

3.7 3.1 13.6 |

mild CR, premature ejaculation, obesity; 1st child: long TTP (natural conception); 2nd child: infertility treatment; 3rd child: ART; brother: died of cardiac arrest (46 years); son: heart murmur | no | 46,XY DSD with atrial septal defect28 |

|

HUWE1 (NM_031407.7) c.5632G>T (p.Ala1878Ser) (hemi) |

previously unreported | 29 | 171 93 31.9 |

0.1 | 23 + 24 47 |

8.1 7.0 15.6 |

CR (unilateral, op. at 3 years) | yes | NOA, severe OZ, CR10 |

|

HUWE1 (NM_031407.7) c.5632G>T (p.Ala1878Ser) (hemi) |

previously unreported | 38 | 178 82 25.7 |

1.6 | 7 + 2 9 |

50.6 20.4 16.9 |

testicular microlithiasis, moderate cognitive, intellectual, and speech impairment; ART: 1 child with speech delay | yes | NOA, severe OZ, CR10 |

| Other primary finding: DHX37 (NM_032656.4) c.1156G>A (p.Gly386Ser) (het) |

rs780020505 1.8 × 10−5 |

no | N/A | ||||||

| Incidental findings: DYRK1A (NM_001347721.2) c.371G>A (p.Arg124Gln), c.994G>T (p.Ala332Ser) (both het) |

previously unreported, rs200519444 7.8 × 10−5 |

||||||||

|

M1AP (NM_001321739.2) c.676dup (p.Trp226Leufs∗4) (hom)c |

rs144217347 3.8 × 10−3 |

32 | 185 66 19.4 |

0 | 21 + 22 43 |

26.1 9.2 16.4 |

SCOS | no | NOA or severe OZ due to MA7 |

|

MCMDC2 (NM_173518.5) c.1767T>A (p.Tyr589∗) (hom) |

rs143895635 3.7 × 10−4 |

32 | 178 154 48.5 |

0 | 15 + 12 27 |

33.7 21.8 6.0 |

N/A | yes | NOA due to MA7 |

|

MCMDC2 (NM_173518.5) c.1363C>T (p.Gln455∗), c.1767T>A (p.Tyr589∗) (both het) |

rs751075073, rs143895635 2.3 × 10−5, 3.7 × 10−4 |

30 | 181 91 27.8 |

0 | 20 + 20 40 |

10.5 8.1 9.9 |

maturation arrest | yes (p.Tyr589∗) | NOA due to MA7 |

|

TEX14 (NM_031272.5) c.1003C>T (p.Arg335∗) (hom)c |

rs141801212 1.3 × 10−3 |

45 | N/A | 0 | 14 + 15 29 |

10.7 7.1 22.2 |

SCOS | yes | NOA |

|

TEX14 (NM_031272.5) c.1003C>T (p.Arg335∗) (hom)c |

rs141801212 1.3 × 10−3 |

36 | 185 106 31.1 |

0 | 20 + 19 39 |

17.6 7.2 15.3 |

CR (unilateral, op. in childhood), SCOS | yes | NOA |

ART, assisted reproductive technology; BMI, body mass index; chet, combined heterozygous; CR, cryptorchidism; DSD, disorders of sex development; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; H, height; hemi, hemizygous; het, heterozygous; hom, homozygous; L, left; LH, luteinizing hormone; MA, maturation/meiotic arrest; N/A, not available; NOA, non-obstructive azoospermia; op., operated; OZ, oligozoospermia; R, right; SCOS, Sertoli cell-only syndrome; T, testosterone; TTP, time to pregnancy; TV, testis volume; W, weight; y, years.

hg38; minor allele frequency (MAF) based on gnomAD v2.1.1 for non-Finnish Europeans; additional data on each variant and phenotype in the ESTAND participant, and references to previously reported variants are provided in Tables S10 and S11

Clinical data at the time of recruitment

Variant previously reported in ClinVar

Brothers

Further recurrent LP/P variants in genes linked to quantitative spermatogenesis were detected in FANCM36 (MIM: 609644), MCMDC26,7 (MIM: 617545), and HUWE110 (MIM: 300697). Men with bi-allelic truncating variants in FANCM (GenBank: NM_020937.4) (c.1491dup [p.Gln498Thrfs∗7], c.5101C>T [p.Gln1701∗]) and MCMDC2 (GenBank: NM_173518.5) (c.1767T>A [p.Tyr589∗]) presented NOA, consistent with literature data. Both oligozoospermic subjects with HUWE1 (GenBank: NM_031407.7) (c.5632G>T [p.Ala1878Ser]) (XL) showed signs of testicular dysgenesis—CR, or low TTV, also observed in the discovery study.10

Highest load of LP/P findings in NR5A1

More than one LP/P variant was identified in 14 of 39 (36%) genes (Figure 1I). Seven disease-causing variants in eight individuals were detected for NR5A1 (MIM: 184757) encoding SF-1 transcription factor (Figure 1J). Infertile men with NR5A1 variants (four LoF, one missense) had reduced TTV and, in most instances, NOA (4/6 subjects) and high BMI (5/6). Adjacent NR5A1 missense substitutions (GenBank: NM_004959.5) (c.22G>C [p.Asp8His] and c.31G>A [p.Glu11Lys]) were each detected in a single normozoospermic man, representing the only LP variants identified in 323 reference subjects in this study. Both men had normal TTV and naturally conceived children. However, the individual with p.Asp8His presented unilateral CR, retractile testicle, hypospadias, and urinary problems, while the person with p.Glu11Lys reported delayed puberty.

Hypospadias had been reported in six men with LP/P NR5A1 variants. Notably, only eight ESTAND individuals with LP/P variants identified in this study had hypospadias. AR (MIM: 313700) (GenBank: NM_000044.6) (c.1723C>G [p.Leu575Val]) (XL; CR with NOA) and FANCM (GenBank: NM_020937.4) (c.1491dup [p.Gln498Thrfs∗7]) (hom; NOA) variants were observed in the other two affected men.

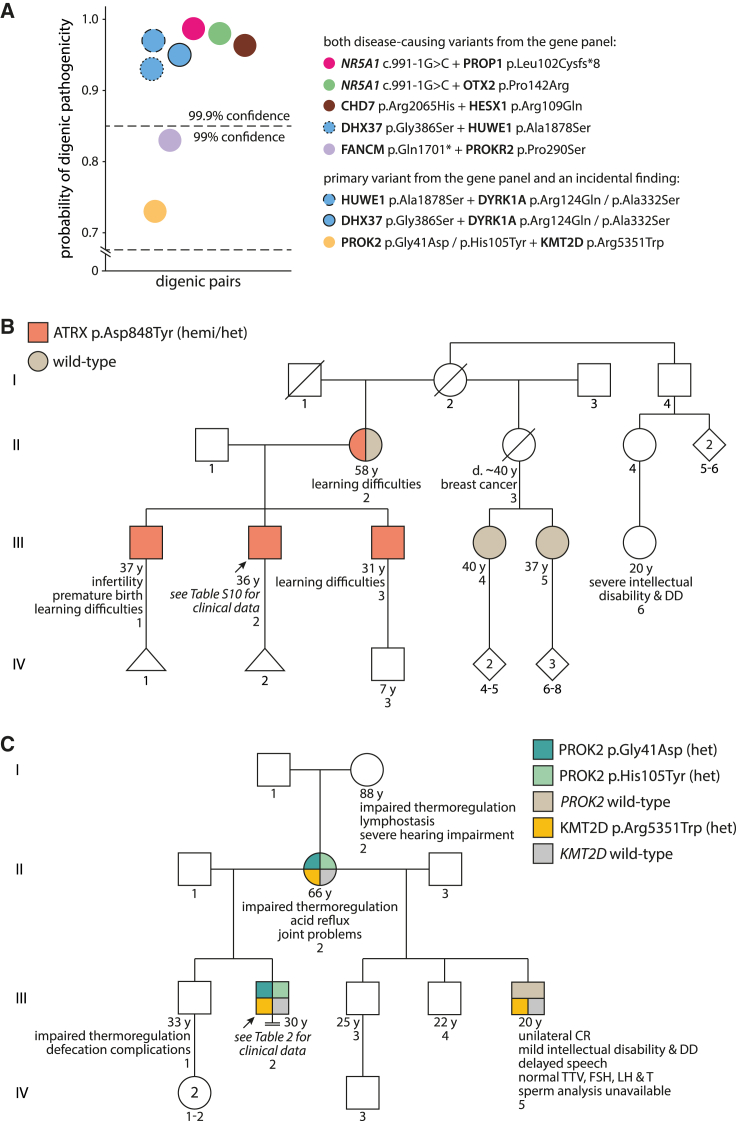

Diversifying the spectrum of genotype-phenotype links of LP/P variants in the HPG axis genes

Disease-causing variants in 20 subjects with SPGF, representing ∼31% of all affected men with findings, were detected in genes implicated in the HPG axis (Table 2). Among 13 affected loci, CHD7 (MIM: 608892), PROK2 (MIM: 607002), and PROKR2 (MIM: 607123) variants have been published in primary SPGF.13 Seven identified variants—CHD7 (GenBank: NM_017780.4) (c.6194G>A [p.Arg2065His]), HESX1 (MIM: 601802) (GenBank: NM_003865.3) (c.326G>A [p.Arg109Gln]), OTX2 (MIM: 600037) (GenBank: NM_021728.4) (c.425C>G [p.Pro142Arg]), PROK2 (GenBank: NM_001126128.2) (c.163del [p.Ile55∗]), and PROKR2 (GenBank: NM_144773.4) (c.868C>T [p.Pro290Ser], c.253C>T [p.Arg85Cys], c.254G>A [p.Arg85His])—in eight men with SPGF have been previously reported in CHH and/or combined pituitary hormone deficiency (CPHD).39 An individual with CR, OZ, and low testosterone levels had two previously reported LP variants, CHD7 p.Arg2065His linked to the CHARGE syndrome25 (MIM: 214800) and HESX1 p.Arg109Gln implicated in CPHD32,33 (MIM: 182230). The platform ORVAL21 predicted a 96% probability of a digenic pathogenic effect (Figure 2A). Four variants in the HPG axis genes were recurrent, detected in two affected ESTAND participants (Table S14), including PROKR2 p.Arg85His, representing a prevalent finding in CHH.24

Figure 2.

Examples of syndromic phenotypes and oligogenicity

(A) Prediction of digenic pathogenicity using the ORVAL platform.40 Alternative colors denote individuals with two LP/P findings except for the blue stroked circles that report the analysis of three gene pairs from a man with trigenic findings (details in Table S11).

(B) Pedigree with the segregating X-linked (XL) ATRX c.2542G>T (p.Asp848Tyr) variant.

(C) Pedigree with the segregating autosomal-dominant (AD) variants PROK2 c.122G>A (p.Gly41Asp) and c.313C>T (p.His105Tyr) (from the gene panel), and KMT2D c.16051C>T (p.Arg5351Trp) (incidental finding). Variant validation by Sanger sequencing is provided in Figures S3 and S4. CR, cryptorchidism; d., died; DD, developmental disorder; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; hemi, hemizygous; het, heterozygous; LH, luteinizing hormone; T, testosterone; TTV, total testis volume; y, years.

Contrary to the CHH phenotype, most subjects with primary SPGF had elevated FSH (14/20, 70%) and LH (11/20, 55%). The lowest levels of FSH (1.1 IU/L; reference ≥1.5 IU/L) and LH (2.8 IU/L) were measured for the individual with SEMA3A (MIM: 603961) (GenBank: NM_006080.3) (c.1450C>T [p.Arg484Trp]). Reduced testosterone levels were observed in 5 of 20 men (25%) with LP/P variants in the HPG axis genes.

Nine men carrying LP/P variants in the HPG axis genes had CR, and an additional eight presented low TTV. Most individuals with available extended health data presented syndromic phenotypes (e.g., joint, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, renal, endocrine, or mental health conditions; obesity; situs inversus) and family health history of various chronic diseases.

Genotype-phenotype links of some less studied candidate genes of syndromic male infertility

GREB1L is a recently proposed male infertility candidate gene.10 The ESTAND participants with heterozygous GREB1L (GenBank: NM_001142966.3) (c.311C>T [p.Pro104Leu]) had NOA, unilateral CR (TTV 7 + 0 mL), and testicular cancer (Table 1). The individual with GREB1L (GenBank: NM_001142966.3) (c.23A>C [p.Gln8Pro]) presented reduced TTV (11 + 13 mL) and severe OZ (sperm count 1.3 × 106/ejaculate). Both had extremely elevated FSH (>31 IU/L).

ATRX (MIM: 300032) truncating variants are linked to developmental delay (DD) and intellectual disability syndromes (MIM: 301040, 309580), and the affected men have been reported to have severe genital anomalies.41,42,43 The subject with hemizygous ATRX (GenBank: NM_000489.6) (c.2542G>T [p.Asp848Tyr]) missense variant (III-2 in Figure 2B) had severe OZ (sperm count 0.3 × 106/ejaculate), unilateral CR (right testis), and seminoma (left testis) diagnosed at 26 years of age (Table S10). Cascade screening revealed maternally inherited ATRX p.Asp848Tyr in the proband and his two brothers (III-1 and III-3 in Figures 2B and S4A). The subject and one brother (III-1 in Figure 2B) were infertile with a history of one miscarried naturally conceived conceptus and no further pregnancies despite long partnerships. Multiple rounds of IVF performed with the cryopreserved sperm of the proband failed. Notably, the subject, his brothers, and his mother (II-2 in Figure 2B) experienced learning difficulties, and the proband’s second cousin (III-6 in Figure 2B; DNA unavailable) presented intellectual disability and DD.

Two men were detected with LP variants in GATA4 (MIM: 600576) (GenBank: NM_001308093.3) (c.1078G>A [p.Glu360Lys], c.487C>T [p.Pro163Ser]) (Tables 3 and S10) previously identified in subjects with structural heart defects with or without 46,XY disorders of sex development28,44 (MIM: 615542). Both ESTAND individuals presented broadly concordant phenotypes: NOA or severe OZ (sperm count 0.9 × 106/ejaculate), mild CR or reduced TTV, short stature, lifelong obesity with comorbidities, and family history of cardiac and fertility concerns. Both had normal FSH, LH, and testosterone levels.

Multiple disease-causing variants in syndromic male infertility phenotypes

Six ESTAND participants were identified with more than one LP/P variant, including five men with two variants found from the gene panel (Table S11; Figures S3 and S4). An individual with multiple childless family members had two recurrently reported disease-causing variants, FANCM (GenBank: NM_020937.4) (c.5101C>T [p.Gln1701∗])36,38,37 and PROKR2 (GenBank: NM_144773.4) (c.868C>T [p.Pro290Ser])24 (83% probability of a digenic pathogenic effect; Figure 2A).

One infertile man (III-2 in Figure 2C) had three maternally inherited variants: PROK2 (GenBank: NM_001126128.2) (c.122G>A [p.Gly41Asp] and c.313C>T [p.His105Tyr]) from the gene panel, and KMT2D (MIM: 602113) (GenBank: NM_003482.4) (c.16051C>T [p.Arg5351Trp]) as an incidental finding (Table 2). He presented bilateral CR and NOA, early puberty, reduced libido, germ cell neoplasia in situ, and general health problems. The family health history included three generations of impaired thermoregulation and gastrointestinal tract conditions, hearing impairment, and joint problems. The proband’s maternal half-brother presented unilateral CR (III-5 in Figure 2C). The cascade screening in the half-brother identified KMT2D p.Arg5351Trp but neither of the PROK2 variants. KMT2D is highly expressed in Sertoli cells (Figure S8) and is linked to Kabuki syndrome (MIM: 147920), characterized by variable congenital conditions, mild to moderate intellectual disability in >90% of subjects, and genital anomalies in 25% of affected men.40 No apparent intellectual or cognitive problems were observed in the proband or his mother (II-2 in Figure 2C), but his half-brother had been diagnosed with mild intellectual disability and DD. Modeling the digenic pathogenicity of the PROK2 and KMT2D variants was inconclusive (probability 73%, Figure 2A).

Another SPGF-affected individual had four variants: DHX37 (MIM: 617362) (GenBank: NM_032656.4) (c.1156G>A [p.Gly386Ser]) (AD, het) and HUWE1 (GenBank: NM_031407.7) (c.5632G>T [p.Ala1878Ser]) (XL; recurrent variant in the cohort) identified from the candidate gene panel and incidental finding DYRK1A (MIM: 600855) (GenBank: NM_001347721.2) (c.371G>A [p.Arg124Gln] and c.994G>T [p.Ala332Ser]) (AD, both het). He presented severe OZ (sperm count 1.6 × 106/ejaculate), extremely reduced TTV (9 mL), and an apparent cognitive, intellectual, and memory impairment during the follow-up assessment (Table 3). Both HUWE1 and DYRK1A have been linked to intellectual disability (MIM: 309590) and DD45,46 (MIM: 614104). DYRK1A is highly transcribed in undifferentiated spermatogonia (Figure S8), and men with LoF variants present variable genitourinary abnormalities.46 Modeling the digenic effect resulted in a 93%–97% probability of pathogenicity of the combined variant effect (Figure 2A).

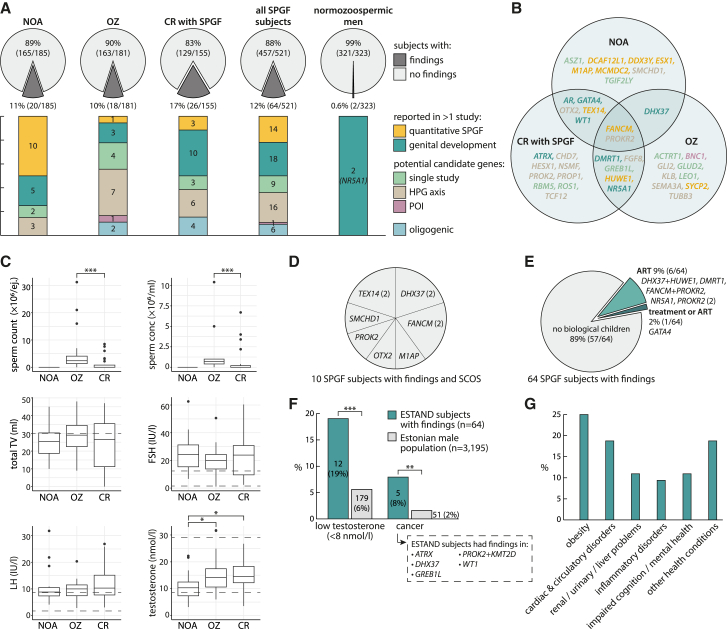

High diagnostic yield in all analyzed male infertility phenotypes

The overall diagnostic yield of the candidate gene analysis in men with SPGF was 12.3% (64 of 521; Figure 3A). This was ∼20-fold higher than the proportion of findings in normozoospermic men (2 of 323, 0.6%, both NR5A1 variants; Fisher’s exact test, OR = 22.4 [95%CI 5.9–190.1; p = 6.2 × 10−12]). There was no statistical difference in the diagnostic yield between the clinical subgroups: NOA (20 of 185, 10.8%), OZ (18 of 181, 9.9%), or CR with SPGF (26 of 155, 16.8%; Table S15). Individuals with NOA had the highest proportion of findings in quantitative spermatogenesis-linked genes. CR accompanied by SPGF was mainly linked to the HPG axis and genital development genes. LP/P variants in ∼1/3 of genes (13 of 39) were identified in more than one clinical subgroup (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Diagnostic yield and clinical characteristics of ESTAND infertile men with causal genetic findings

(A) Diagnostic yield and affected gene categories in the clinical subgroups.

(B) Affected genes stratified by primary diagnosis.

(C) Comparison of the distribution of andrological parameters among men with genetic findings in each clinical subgroup (Mann-Whitney U test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). The box indicates the inter-quartile range with the median line, whiskers show the 1.5× inter-quartile range, and points show outliers.

(D) Distribution of affected genes in men with Sertoli cell-only syndrome (SCOS).

(E) Affected genes in SPGF-affected individuals reaching biological fatherhood.

(F) The prevalence of low testosterone levels and cancer in SPGF subjects with genetic findings and the general male population (Fisher’s exact test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

(G) Other reported health conditions in SPGF-affected individuals with causal genetic findings. Detailed data are provided in Tables S10–S12.

ART, assisted reproductive technologies; conc, concentration; CR, cryptorchidism; ej., ejaculate; ESTAND, ESTonian ANDrology; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HPG, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis; LH, luteinizing hormone; NOA, non-obstructive azoospermia; OZ, oligozoospermia; POI, primary ovarian insufficiency; SPGF, spermatogenic failure; TV, testis volume.

Most men with genetic infertility had extremely elevated FSH (median 21.8 IU/L) and LH (median 9.8 IU/L) and reduced TTV (median 27 mL) at the time of recruitment before any infertility treatments, also reflecting the composition of the study cohort (Figure 3C; Tables 1 and S16). Testis biopsies to screen for immature sperms had been performed for 17 of 64 infertile men with findings, none of whom were able to have biological children. Among these, SCOS was observed in 10 individuals carrying LP/P variants in seven genes, including FANCM, TEX14, and DHX37 in two instances (Figure 3D). Biological fatherhood after infertility management had been successful for 7 of 64 (10.9%) men with diverse causative findings mainly affecting the HPG axis or gonadal development (Figure 3E; Tables S10 and S11). All these men presented severe OZ on their first visit to the andrology clinic.

Health comorbidities in men with genetic SPGF

Individuals with genetic SPGF (median age 32 years) compared to the population-based cohort of 3,195 Estonian men (40–49 years) showed a 3-fold higher prevalence of low testosterone levels (<8 nmol/L; 19% vs. 6%, p = 2.6 × 10−4) and a 4-fold higher prevalence of cancer (8% vs. 2%; p = 4.4 × 10−3; Figure 3F). Men with ATRX, GREB1L, and PROK2 altering variants had early-onset testicular cancer (≤30 years), whereas subjects with WT1 (MIM: 607102) and DHX37 variants had been diagnosed with melanoma. No significant difference was detected in the prevalence of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular, urinary-renal, or mental health conditions compared to the general Estonian male population (Figure 3G).

Discussion

This large study aimed at a comprehensive analysis of 638 candidate genes for primary SPGF with a long-term goal to pave the way toward clinical exomes in male infertility workup. Likely causal variants were identified for 12.3% of the study cohort comprised of 521 ESTAND participants with idiopathic SPGF. Previous studies of candidate genes linked to primary SPGF have included smaller cohorts and/or a lower number of loci, and on most occasions, the diagnostic yield has been ∼5% or less.14,47 Notably, the proportion of molecular findings in ESTAND individuals with NOA (36 of 281, 12.8%) and OZ (28 of 239, 11.7%) was similar. Most of the previous studies have solely focused on the NOA phenotype. Even when individuals with severe OZ were included, these subsets were not assessed independently (Table S13). Additionally, the current study analyzed separately a large sample of adult men presenting CR with SPGF, which has previously received limited attention. This clinical subgroup had the highest diagnostic yield, 26 of 155 subjects (17%) with confident LP/P findings (Figure 3A).

Disease-causing variants were identified in 39 of 638 (6%) analyzed genes implicated in human reproduction. High genetic heterogeneity, population-specific genetic architecture in male infertility, and a different study design are possible explanations for the limited number of candidate genes affected in our study cohort. Supportive to diverse genetic etiologies, two recent extensive WES studies (924 NOA-affected individuals9 and 185 NOA/OZ-affected individuals10) reported most of their findings in genes not previously linked to male infertility (Table S5). Much work is still ahead to confirm genotype-phenotype links for hundreds of proposed genes in an increasing load of publications frequently based on one or two affected men or families. As an example, the genotype-phenotype data in the current study did not support the previously suggested haplosensitivity of SEPTIN12.48 Our observation aligns with the study showing that Septin12−/− male mice are infertile, whereas Septin12+/− male mice are not.49

The study validated the phenotype-genotype link for eight candidate genes proposed by a single study (Table 1) and strengthened the evidence for several more recently proposed SPGF candidate genes. For example, two different LP/P variants were detected in the ESTAND cohort in MCMDC26,7 and GREB1L.10 With the current study, the link between bi-allelic MCMDC2 truncating variants and NOA (maturation arrest) has been documented in three independent reports in populations with different demographic contexts. A homozygous MCMDC2 nonsense substitution was also reported in a woman with POI,50 referring to a shared genetic etiology likely due to defective DNA repair. GREB1L is known to be involved in genitourinary development and an AD form of renal agenesis (MIM: 617805).51,52,53 The two ESTAND infertile subjects and a previously reported azoospermic man10 with GREB1L findings presented reduced TTV (and CR in one subject) but no congenital renal phenotypes.

We detected a surprisingly high fraction of recurrent variants (∼30%) that had been previously reported in infertile men in other population(s) and/or were observed in more than one ESTAND participant (Figure 1F; Tables 2 and 3). Several alternative explanations can be considered. As there is no selective pressure to filter out rare variants in genes linked to AR conditions in an outbred population, these variants may trace back thousands of years and reflect a shared demographic history. XL and AD variants linked to SPGF can be maternally inherited (see examples in Figures 2 and S3) or may represent de novo mutations in DNA sites prone to changes as has been suggested.10 The penetrance and expressivity of disease-causing variants can be modulated by oligogenic contribution.35,54,55 This study identified six infertile individuals with more than one disease-causing variant that may jointly explain their phenotype (Figure 2A; Table S11).

Approximately 1/3 of genes with findings had more than one LP/P variant, allowing us to explore the phenotypic diversity linked to the disrupted gene. An example is NR5A1, with seven previously unreported variants identified in six severely affected men and two normozoospermic subjects also presenting some reproductive concerns (Figure 1J). Disease-causing variants in NR5A1 are frequently inherited from a parent with no or mild reproductive phenotype, such as POI or hypospadias.35,56 A review of 238 affected men with NR5A1 LP/P variants concluded that it was nearly impossible to establish a concise phenotype-genotype link due to variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance.56

Previous research in male infertility genes has focused chiefly on spermatogenesis-linked loci that function after the induction of sperm production in puberty. This study broadened the molecular etiology of SPGF, suggesting that a fraction of individuals with SPGF may present undiagnosed congenital developmental conditions with less pronounced phenotypes that, on some occasions, may affect only the reproductive system. For example, the HPG axis has been linked to CHH, primarily identified due to absent or incomplete sexual maturation in puberty.24,31 This study identified infertile men with known CHH-linked variants without the classical hypogonadal phenotype. On the contrary, CR, reduced TTV, and high FSH observed in most affected individuals suggested testicular dysgenesis as the primary cause of their condition. Men carrying LP/P variants in CHD7, HESX1, PROK2, PROKR2, OTX2, and PROP1 (MIM: 601538) presented an oligogenic disease model, as already shown for CHH >10 years ago54 (Table 2; Figure 2). Several gonadal developmental genes are well known (e.g., NR5A1, WT1) but have been mainly studied in individuals with more extreme phenotypes, such as sex reversal. Pleiotropic congenital defects that also affect testis development in utero and/or puberty have not been considered enough as primary causes of SPGF.

Among the known POI-linked genes, BNC1 emerged as a plausible candidate locus also for male infertility. We identified BNC1 frameshift variants in two men with severe OZ, one recruited to the ESTAND and the other to the Fundació Puigvert validation cohort (Table S12). As BNC1 is intolerant to LoF variations (pLI score 1.0), these variants were most likely de novo; however, parental data for these individuals were unavailable. Several lines of evidence support the identified link between BNC1 truncating variants and SPGF. BNC1 is required for the maintenance of spermatogenesis57,58 with considerable expression in various testicular cell types (Figure 1D), that has been reported to be reduced in men with NOA.59 Bnc1-null and Bnc1-mutated male mice present a progressive loss of germ cells, early testicular aging, and subfertility.60,61

This study has several additional strengths. All ESTAND SPGF-affected and normozoospermic men were recruited and uniformly thoroughly phenotyped in one clinical center serving the whole country. The unique subgroup of 323 normozoospermic men with a complete andrological phenotype2,16 and WES data allowed us to filter out rare variants also detected in fertile men. If consented by study participants, the follow-up clinical assessment and gathered family health history increased the confidence in establishing the genotype-phenotype links. The documentation of general health concerns at the time of recruitment and follow-up interviews facilitated the analysis of genetic comorbidities in the current study. As a clinically important secondary outcome, we identified a 4-fold higher incidence of early-onset cancer among men with genetic SPGF compared to the general male population (Figure 3F). A limitation was that only a subset of participants was available for the follow-up assessment, and cascade screening was possible in only a few cases due to difficulties in recruiting family members.

As a final remark, the clinical impact and perspectives of the results are to be highlighted. One in eight men with idiopathic SPGF received a molecular diagnosis from the targeted gene panel analyzed from the WES dataset. This highlights the added value of introducing clinical exomes in andrology services worldwide, leading to an improved and timely management of SPGF and couples seeking assistance and counseling due to involuntary childlessness. This study was performed in a nationwide cohort representing an outbred population, so its results are transferable to various clinical settings. Genetic male infertility may also be syndromic and/or accompanied by variant-specific comorbidities. The expansion of molecular diagnostics tools in andrology will be highly informative for the multidisciplinary clinical management of men with SPGF.

Data and code availability

All data supporting the findings and conclusions of this study are available within the paper and supplemental information. The accession numbers for the genotype-phenotype data reported in this paper are ClinVar https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar: SCV000803407.1, SCV000803408.1, SCV000803409.3, SCV003803706.1, SCV002525859–SCV002525861, SCV004239139–SCV004239202.

The exome datasets supporting the current study have not been deposited in a public repository because of ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and ethical approval.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants in the ESTAND cohort and the clinical team at the Andrology Center of Tartu University Hospital for the phenotyping and recruitment of participants. We acknowledge the personnel of the Chair of Human Genetics at the Institute of Biomedicine and Translational Medicine, University of Tartu, for DNA extractions and management of the ESTAND Androgenetics Biobank. We thank Carson Holt, Steve Boyden, and the Utah Center for Genetics Discovery for assistance with the primary processing of the GEMINI WES data.

This work was supported by grants from the Estonian Research Council (PRG1021 to M.L.), the National Institutes of Health (R01HD078641 to D.F.C. and K.I.A. and P50HD096723 to D.F.C.), a Research Foundation Flanders (F.W.O.) Infrastructure project associated with ELIXIR Belgium (I002819N to T.L.), Innoviris Joint R&D project Genome4Brussels (2020 RDIR 55b to N.V. and T.L.), and Spanish Ministry of Health Instituto Carlos III-FIS (PI20/01562 to C.K. and A.R.-E.). S.P. was supported by a personal fellowship from Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique - FNRS Postdoctoral Researcher Fellowship (40005602) and M.L. from the Baltic-American Freedom Foundation (BAFF).

Author contributions

Study conceptualization and study cohort formation, M.L. and M.P.; cohort recruitment and phenotyping, M.P., K.P., O.P., E.T., V.V., S. Tjagur, V.K., S. Tennisberg, and P.K.; exome data generation, M.L., L.N., K.I.A., H.C.-M., and D.F.C.; bioinformatics processing and filtering of exomes, A.D.; gene panel formation, exome data analysis, and interpretation, K.L., A.-G.J., A.V., L.K., and M.L.; follow-up clinical data collection, K.L., A.-G.J., K.P., M.S., L.K., M.P., and M.L.; experimental validation of variants, K.L., A.-G.J., A.V., and L.K.; analysis of BNC1 variants in the validation cohort, A.R.-E., G.F., and C.K.; modeling digenic effects, A.D., S.P., N.V., and T.L.; testicular gene expression analysis, E.M.; histopathology: E.T.; writing, K.L. and M.L.; visualization, K.L. with the help of E.T., E.M., and M.L.; supervision, M.L.; funding acquisition, M.L., M.P., T.L., K.I.A., D.F.C., and C.K. All authors provided comments and approved the paper.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 12, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2024.03.013.

Contributor Information

Margus Punab, Email: margus.punab@kliinikum.ee.

Maris Laan, Email: maris.laan@ut.ee.

Web resources

ClinVar, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar

Franklin, https://franklin.genoox.com

GenBank, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/

Genomics England PanelApp, https://panelapp.genomicsengland.co.uk

HISTA homepage, https://conradlab.shinyapps.io/HISTA/

HISTA program, https://github.com/eisascience/HISTA

MGI, https://www.informatics.jax.org

OMIM, https://www.omim.org

ORVAL, https://orval.ibsquare.be

Supplemental information

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Sixth Edition. 2021. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Punab M., Poolamets O., Paju P., Vihljajev V., Pomm K., Ladva R., Korrovits P., Laan M. Causes of male infertility: A 9-year prospective monocentre study on 1737 patients with reduced total sperm counts. Hum. Reprod. 2017;32:18–31. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alhathal N., Maddirevula S., Coskun S., Alali H., Assoum M., Morris T., Deek H.A., Hamed S.A., Alsuhaibani S., Mirdawi A., et al. A genomics approach to male infertility. Genet. Med. 2020;22:1967–1975. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0916-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S., Wang G., Zheng X., Ge S., Dai Y., Ping P., Chen X., Liu G., Zhang J., Yang Y., et al. Whole-exome sequencing of a large Chinese azoospermia and severe oligospermia cohort identifies novel infertility causative variants and genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020;29:2451–2459. doi: 10.1093/HMG/DDAA101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fakhro K.A., Elbardisi H., Arafa M., Robay A., Rodriguez-Flores J.L., Al-Shakaki A., Syed N., Mezey J.G., Abi Khalil C., Malek J.A., et al. Point-of-care whole-exome sequencing of idiopathic male infertility. Genet. Med. 2018;20:1365–1373. doi: 10.1038/gim.2018.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghieh F., Barbotin A.L., Swierkowski-Blanchard N., Leroy C., Fortemps J., Gerault C., Hue C., Mambu Mambueni H., Jaillard S., Albert M., et al. Whole-exome sequencing in patients with maturation arrest: a potential additional diagnostic tool for prevention of recurrent negative testicular sperm extraction outcomes. Hum. Reprod. 2022;37:1334–1350. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deac057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kherraf Z.E., Cazin C., Bouker A., Fourati Ben Mustapha S., Hennebicq S., Septier A., Coutton C., Raymond L., Nouchy M., Thierry-Mieg N., et al. Whole-exome sequencing improves the diagnosis and care of men with non-obstructive azoospermia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022;109:508–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malcher A., Stokowy T., Berman A., Olszewska M., Jedrzejczak P., Sielski D., Nowakowski A., Rozwadowska N., Yatsenko A.N., Kurpisz M.K. Whole-genome sequencing identifies new candidate genes for nonobstructive azoospermia. Andrology. 2022;10:1605–1624. doi: 10.1111/ANDR.13269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagirnaja L., Lopes A.M., Charng W.-L., Miller B., Stakaitis R., Golubickaite I., Stendahl A., Luan T., Friedrich C., Mahyari E., et al. Diverse Monogenic Subforms of Human Spermatogenic Failure. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:7953. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35661-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oud M.S., Smits R.M., Smith H.E., Mastrorosa F.K., Holt G.S., Houston B.J., de Vries P.F., Alobaidi B.K.S., Batty L.E., Ismail H., et al. A de novo paradigm for male infertility. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:154. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riera-Escamilla A., Vockel M., Nagirnaja L., Xavier M.J., Carbonell A., Moreno-Mendoza D., Pybus M., Farnetani G., Rosta V., Cioppi F., et al. Large-scale analyses of the X chromosome in 2,354 infertile men discover recurrently affected genes associated with spermatogenic failure. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022;109:1458–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houston B.J., Riera-escamilla A., Wyrwoll M.J., Salas-Huetos A., Xavier M.J., Nagirnaja L., Friedrich C., Conrad D.F., Aston K.I., Krausz C., et al. A systematic review of the validated monogenic causes of human male infertility: 2020 update and a discussion of emerging gene–disease relationships. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2021;28:15–29. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmab030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasak L., Laan M. Monogenic causes of non-obstructive azoospermia: challenges, established knowledge, limitations and perspectives. Hum. Genet. 2021;140:135–154. doi: 10.1007/s00439-020-02112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laan M., Kasak L., Punab M. Translational aspects of novel findings in genetics of male infertility - status quo 2021. Br. Med. Bull. 2021;140:5–22. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldab025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaprara A., Huhtaniemi I.T. The hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis: Tales of mice and men. Metabolism. 2018;86:3–17. doi: 10.1016/J.METABOL.2017.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehala-Aleksejev K., Punab M. The different surrogate measures of adiposity in relation to semen quality and serum reproductive hormone levels among Estonian fertile men. Andrology. 2015;3:225–234. doi: 10.1111/andr.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaren W., Gil L., Hunt S.E., Riat H.S., Ritchie G.R.S., Thormann A., Flicek P., Cunningham F. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17:122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landrum M.J., Lee J.M., Benson M., Brown G.R., Chao C., Chitipiralla S., Gu B., Hart J., Hoffman D., Jang W., et al. ClinVar: Improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1062–D1067. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Turner D., Mesirov J.P. igv.js: an embeddable JavaScript implementation of the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) Bioinformatics. 2023;39 doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTAC830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renaux A., Papadimitriou S., Versbraegen N., Nachtegael C., Boutry S., Nowé A., Smits G., Lenaerts T. ORVAL: a novel platform for the prediction and exploration of disease-causing oligogenic variant combinations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W93–W98. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahyari E., Guo J., Lima A.C., Lewinsohn D.P., Stendahl A.M., Vigh-Conrad K.A., Nie X., Nagirnaja L., Rockweiler N.B., Carrell D.T., et al. Comparative single-cell analysis of biopsies clarifies pathogenic mechanisms in Klinefelter syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021;108:1924–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang D., Liu Y., Zhang Z., Lv P., Liu Y., Li J., Wu Y., Zhang R., Huang Y., Xu G., et al. Basonuclin 1 deficiency is a cause of primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:3787–3800. doi: 10.1093/HMG/DDY261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodé C., Teixeira L., Levilliers J., Fouveaut C., Bouchard P., Kottler M.L., Lespinasse J., Lienhardt-Roussie A., Mathieu M., Moerman A., et al. Kallmann syndrome: Mutations in the genes encoding prokineticin-2 and prokineticin receptor-2. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e175–e1652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonçalves C.I., Patriarca F.M., Aragüés J.M., Carvalho D., Fonseca F., Martins S., Marques O., Pereira B.D., Martinez-de-Oliveira J., Lemos M.C. High frequency of CHD7 mutations in congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1597. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38178-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang D., Li K., Geng H., Xu C., Lv M., Gao Y., Wang G., Yu H., Shao Z., Shen Q., et al. Identification of deleterious variants in patients with male infertility due to idiopathic non-obstructive azoospermia. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2022;20:63. doi: 10.1186/s12958-022-00936-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma Q., Du Y., Luo X., Ye J., Gui Y. Association of ESX1 gene variants with non-obstructive azoospermia in Chinese males. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:4587. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shichiri Y., Kato Y., Inagaki H., Kato T., Ishihara N., Miyata M., Boda H., Kojima A., Miyake M., Kurahashi H. A case of 46, XY disorders of sex development with congenital heart disease caused by a GATA4 variant. Congenital. Anom. 2022;62:203–207. doi: 10.1111/cga.12482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyrwoll M.J., Temel Ş.G., Nagirnaja L., Oud M.S., Lopes A.M., van der Heijden G.W., Heald J.S., Rotte N., Wistuba J., Wöste M., et al. Bi-allelic Mutations in M1AP Are a Frequent Cause of Meiotic Arrest and Severely Impaired Spermatogenesis Leading to Male Infertility. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;107:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vizeneux A., Hilfiger A., Bouligand J., Pouillot M., Brailly-Tabard S., Bashamboo A., McElreavey K., Brauner R. Congenital Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism during Childhood: Presentation and Genetic Analyses in 46 Boys. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitteloud N., Zhang C., Pignatelli D., Li J.D., Raivio T., Cole L.W., Plummer L., Jacobson-Dickman E.E., Mellon P.L., Zhou Q.Y., Crowley W.F., Jr. Loss-of-function mutation in the prokineticin 2 gene causes Kallmann syndrome and normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:17447–17452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707173104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi J.H., Jung C.W., Kang E., Kim Y.M., Heo S.H., Lee B.H., Kim G.H., Yoo H.W. Rare frequency of mutations in pituitary transcription factor genes in combined pituitary hormone or isolated growth hormone deficiencies in Korea. Yonsei Med. J. 2017;58:527–532. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2017.58.3.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takagi M., Takahashi M., Ohtsu Y., Sato T., Narumi S., Arakawa H., Hasegawa T. A novel mutation in HESX1 causes combined pituitary hormone deficiency without septo optic dysplasia phenotypes. Endocr. J. 2016;63:405–410. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ15-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorbenko Del Blanco D., Romero C.J., Diaczok D., De Graaff L.C.G., Radovick S., Hokken-Koelega A.C.S. A novel OTX2 mutation in a patient with combined pituitary hormone deficiency, pituitary malformation, and an underdeveloped left optic nerve. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012;167:441–452. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laan M., Kasak L., Timinskas K., Grigorova M., Venclovas Č., Renaux A., Lenaerts T., Punab M. NR5A1 c.991-1G > C splice-site variant causes familial 46,XY partial gonadal dysgenesis with incomplete penetrance. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021;94:656–666. doi: 10.1111/cen.14381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasak L., Punab M., Nagirnaja L., Grigorova M., Minajeva A., Lopes A.M., Punab A.M., Aston K.I., Carvalho F., Laasik E., et al. Bi-allelic Recessive Loss-of-Function Variants in FANCM Cause Non-obstructive Azoospermia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;103:200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fouquet B., Pawlikowska P., Caburet S., Guigon C., Mäkinen M., Tanner L., Hietala M., Urbanska K., Bellutti L., Legois B., et al. A homozygous FANCM mutation underlies a familial case of non-syndromic primary ovarian insufficiency. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/ELIFE.30490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiiski J.I., Pelttari L.M., Khan S., Freysteinsdottir E.S., Reynisdottir I., Hart S.N., Shimelis H., Vilske S., Kallioniemi A., Schleutker J., et al. Exome sequencing identifies FANCM as a susceptibility gene for triple-negative breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:15172–15177. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.1407909111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cangiano B., Swee D.S., Quinton R., Bonomi M. Genetics of congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: peculiarities and phenotype of an oligogenic disease. Hum. Genet. 2021;140:77–111. doi: 10.1007/S00439-020-02147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheon C.K., Ko J.M. Kabuki syndrome: Clinical and molecular characteristics. Korean J. Pediatr. 2015;58:317–324. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2015.58.9.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takagi M., Yagi H., Fukuzawa R., Narumi S., Hasegawa T. Syndromic disorder of sex development due to a novel hemizygous mutation in the carboxyl-terminal domain of ATRX. Hum. Genome Var. 2017;4 doi: 10.1038/HGV.2017.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ji J., Quindipan C., Parham D., Shen L., Ruble D., Bootwalla M., Maglinte D.T., Gai X., Saitta S.C., Biegel J.A., Mascarenhas L. Inherited germline ATRX mutation in two brothers with ATR-X syndrome and osteosarcoma. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2017;173:1390–1395. doi: 10.1002/AJMG.A.38184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibbons R.J., Higgs D.R. Molecular-clinical spectrum of the ATR-X syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000;97:204–212. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200023)97:3<204::AID-AJMG1038>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang W., Li X., Shen A., Jiao W., Guan X., Li Z. GATA4 mutations in 486 Chinese patients with congenital heart disease. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2008;51:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moortgat S., Berland S., Aukrust I., Maystadt I., Baker L., Benoit V., Caro-Llopis A., Cooper N.S., Debray F.G., Faivre L., et al. HUWE1 variants cause dominant X-linked intellectual disability: A clinical study of 21 patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;26:64–74. doi: 10.1038/s41431-017-0038-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blackburn A.T.M., Bekheirnia N., Uma V.C., Corkins M.E., Xu Y., Rosenfeld J.A., Bainbridge M.N., Yang Y., Liu P., Madan-Khetarpal S., et al. DYRK1A-related intellectual disability: a syndrome associated with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Genet. Med. 2019;21:2755–2764. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0576-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wyrwoll M.J., Köckerling N., Vockel M., Dicke A.K., Rotte N., Pohl E., Emich J., Wöste M., Ruckert C., Wabschke R., et al. Genetic Architecture of Azoospermia—Time to Advance the Standard of Care. Eur. Urol. 2023;83:452–462. doi: 10.1016/J.EURURO.2022.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y., Wang Y., Wen Y., Zhang T., Wang X., Jiang C., Zheng R., Zhou F., Chen D., Yang Y., Shen Y. Whole-exome sequencing of a cohort of infertile men reveals novel causative genes in teratozoospermia that are chiefly related to sperm head defects. Hum. Reprod. 2021;37:152–177. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deab229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen H., Li P., Du X., Zhao Y., Wang L., Tian Y., Song X., Shuai L., Bai X., Chen L. Homozygous Loss of Septin12, but not its Haploinsufficiency, Leads to Male Infertility and Fertilization Failure. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2022.850052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ke H., Tang S., Guo T., Hou D., Jiao X., Li S., Luo W., Xu B., Zhao S., Li G., et al. Landscape of pathogenic mutations in premature ovarian insufficiency. Nat. Med. 2023;29:483–492. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02194-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacquinet A., Boujemla B., Fasquelle C., Thiry J., Josse C., Lumaka A., Brischoux-Boucher E., Dubourg C., David V., Pasquier L., et al. GREB1L variants in familial and sporadic hereditary urogenital adysplasia and Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Clin. Genet. 2020;98:126–137. doi: 10.1111/CGE.13769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanna-Cherchi S., Khan K., Westland R., Krithivasan P., Fievet L., Rasouly H.M., Ionita-Laza I., Capone V.P., Fasel D.A., Kiryluk K., et al. Exome-wide Association Study Identifies GREB1L Mutations in Congenital Kidney Malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;101:789–802. doi: 10.1016/J.AJHG.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brophy P.D., Rasmussen M., Parida M., Bonde G., Darbro B.W., Hong X., Clarke J.C., Peterson K.A., Denegre J., Schneider M., et al. A gene implicated in activation of retinoic acid receptor targets is a novel renal agenesis gene in humans. Genetics. 2017;207:215–228. doi: 10.1534/GENETICS.117.1125/-/DC1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sykiotis G.P., Plummer L., Hughes V.A., Au M., Durrani S., Nayak-Young S., Dwyer A.A., Quinton R., Hall J.E., Gusella J.F., et al. Oligogenic basis of isolated gonadotropin-releasing hormone deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:15140–15144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009622107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Posey J.E., Harel T., Liu P., Rosenfeld J.A., James R.A., Coban Akdemir Z.H., Walkiewicz M., Bi W., Xiao R., Ding Y., et al. Resolution of Disease Phenotypes Resulting from Multilocus Genomic Variation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:21–31. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1516767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fabbri-Scallet H., de Sousa L.M., Maciel-Guerra A.T., Guerra-Júnior G., de Mello M.P. Mutation update for the NR5A1 gene involved in DSD and infertility. Hum. Mutat. 2020;41:58–68. doi: 10.1002/humu.23916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]