Abstract

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth was employed to enhance clinical outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. However, the effectiveness of telehealth remains inconclusive.

Objective

This study aimed to examine the impact of telehealth on the glycemic control of individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus during the pandemic.

Design

A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Setting

N/A

Participants

A total of 669 studies was sourced from electronic databases, including EMBASE, PubMed, and Scopus. Among these, twelve randomized controlled trials, comprising 1498 participants, were included.

Methods

A comprehensive search was performed in electronic databases. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, and statistical heterogeneity was assessed using I² and Cochran's Q tests. A random-effects model was utilized to combine the outcomes. Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations was used to evaluate the certainty of the evidence.

Results

The meta-analysis showed that participants receiving a telehealth intervention achieved a greater reduction in the glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C) compared to those receiving usual care, with a weighted-mean difference of -0.59 (95 % CI -0.84 to -0.35, p < .001, I² = 74.1 %, high certainty of evidence). Additionally, participants receiving telehealth interventions experienced better secondary outcomes, including a reduction in fasting blood sugar (16.06 %, 95 %CI -29.64 to -2.48, p = .02, high certainty of evidence), a decrease in body mass index (1.5 %, 95 %CI -1.98 to -1.02, p < .001, high certainty of evidence), and a decrease in low-density lipoprotein (7.8 %, 95 %CI -14.69 to -0.88, p = .027, low certainty of evidence).

Conclusions

In our review, we showed telehealth's positive impact on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Healthcare professionals can use telehealth in diabetes care. Caution is needed due to heterogeneity of the results. Further research should explore the long-term impacts of telehealth interventions.

Registration

The study was registered with PROSPERO, CRD42022381879.

Keywords: Telehealth, Telemedicine, Diabetes mellitus, Glycaemic control, Meta-analysis, COVID-19

What is already known about the topic?

-

•

During the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth was employed to enhance clinical outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

-

•

Access to telehealth is not within everyone's reach, and the clear conclusions about the effects of telehealth in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus during the pandemic have yet to be fully understood.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

What this paper adds.

-

•

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate and synthesize the current evidence from randomised controlled trials on the effectiveness of telehealth for achieving glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus during the COVID-19 pandemic into a single, aggregated reference resource.

-

•

We provided potentially valuable insights for healthcare professionals to enhance the provision of diabetes care services through telehealth, especially during a pandemic or other disruptive event.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Background

Diabetes mellitus is a major public health issue globally, with over 537 million adults affected, a number expected to rise to 783.2 million by 2045 (Sun et al., 2021). Type 2 diabetes mellitus accounts for 90 % of cases and imposes a significant burden on individuals and society (Goyal et al., 2022), impacting life expectancy and quality of life (Rapoport et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2018). The projected health expenditures related to diabetes mellitus are estimated to increase from 966 billion USD in 2021 to 1054 billion USD by 2045 (Sun et al., 2022).

Poor glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus increases the risk of complications, such as retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease, which can lead to disability and premature death (Fasil et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2021). Glycaemic control is measured by maintaining the glycated haemoglobin levels below 7 %. (The American Diabetes Association [ADA], 2022a) The American Diabetes Association recommends a comprehensive approach to managing diabetes, including nutrition therapy, physical activity, medication adherence, glucose monitoring, and lifestyle changes. (The American Diabetes Association [ADA], 2022b; The American Diabetes Association [ADA], 2022c) Telehealth interventions can play a crucial role in improving access to care, self-management, and communication between patients and healthcare providers. Previous meta-analyses have shown that effective management of diabetes can significantly improve glycaemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus, thereby reducing the risk of complications associated with diabetes (Garcia-Molina et al., 2020; Hildebrand et al., 2020).

Telehealth is an electronic information and telecommunication-based healthcare delivery method that facilitates information exchange, education, consultation, monitoring, and management between healthcare professionals and patients [The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), 2020; World Health Organization (WHO), 2022]. It is useful for individuals in remote areas or situations where in-person care is not feasible. Telehealth interventions have been shown to improve health outcomes for patients with chronic diseases, including diabetes mellitus (Kuan et al., 2022b; De Groot et al., 2021; Saragih et al., 2022; Chiaranai et al., 2023).

The rapid outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in December 2019 resulted in millions of severe respiratory infections that led to respiratory failure and death worldwide (Clark et al., 2020). To control the outbreak, many governments implemented community lockdown and social distancing measures. However, these measures disrupted daily activities and significantly impacted routine healthcare services, including limiting outpatient visits, preventing face-to-face education, and canceling appointments. As a result, individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus were particularly vulnerable and experienced negative impacts on their glycaemic control, metabolic control, exercise levels, and dietary patterns during the pandemic (Biamonte et al., 2021; Ojo et al., 2022; Ruiz-Roso et al., 2020). The vulnerability could be due to factors such as the need for continuous monitoring, the potential for acute complications, and the impact of lifestyle changes on disease management. These changes could increase the risk of their illness's progression or mortality. Unlike other chronic conditions, diabetes is characterized by the need for continuous management and monitoring of blood glucose levels, medication adjustments, and lifestyle modifications. Regular check-ups and consultations with healthcare providers are fundamental for effective diabetes management. In contrast, stroke is an acute event that may necessitate immediate medical attention and rehabilitation, but it can also be a one-time occurrence. While ongoing care and support are essential for stroke patients, the frequency of medical visits may fluctuate depending on their specific condition and recovery stage.

During the pandemic, telehealth was most frequently utilized to ensure continuing care for several chronic diseases, including diabetes mellitus. People with diabetes mellitus are at higher risk for cardiovascular diseases, kidney problems, and other health issues. The vulnerability could be due to factors such as the need for continuous monitoring, the potential for acute complications, and the impact of lifestyle changes on disease management. Telehealth interventions could provide a way to address these vulnerabilities by offering more frequent and convenient access to healthcare services and support. Evaluating the effectiveness of telehealth for diabetes patients is important because it addresses the need for convenient and efficient ways to support diabetes management, potentially leading to better health outcomes and reduced healthcare costs.

However, access to telehealth is not within everyone's reach, and clear conclusions about the effects of telehealth in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus during the pandemic have yet to be fully understood. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate and synthesize the current evidence from randomised controlled trials on the effectiveness of telehealth for achieving glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus during the COVID-19 pandemic into a single, aggregated reference resource. The findings could provide valuable insights for healthcare professionals to enhance the provision of diabetes care services through telehealth, especially during a pandemic or other disruptive event.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

We thoroughly searched electronic databases (EMBASE, PubMed, Scopus) from each database's inception to November 2022, focusing on articles published after March 11, 2020—the date when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic (Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020). The search strategy was optimized to capture studies in telehealth, people with type 2 diabetes mellitus, glycaemic control, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Telehealth is a broad and evolving field encompassing various aspects of remote healthcare delivery. While our search strategies primarily focused on the MeSH term “telehealth,” it is important to acknowledge that this field includes a wide range of related terms, such as “telemonitoring,” “telemedicine,” “mobile health” (mHealth), “eHealth,” “teleconsultation,” “digital health”, and “telenursing.” These terms are interconnected within the realm of telehealth, and understanding their relationships is crucial for a comprehensive search. “Telemonitoring” involves remote patient monitoring, “telemedicine” pertains to remote medical consultations and diagnosis, “mobile health”, “digital health”, and “eHealth” refer to healthcare facilitated through mobile devices and electronic means, while “teleconsultation” and “telenursing” encompass remote healthcare consultations and nursing services, respectively. By including these related terms in our search strategies, we aimed to capture a broader spectrum of relevant literature that contributed to the overarching field of telehealth. Our search terms included “(telehealth OR telemedicine OR telemonitoring OR mobile health OR mHealth OR eHealth OR telenursing OR digital health OR teleconsultation) AND (type 2 diabetes OR type 2 DM) AND (“glycaemic control” OR HbA1C) AND (COVID-19 OR Coronavirus disease 2019). We imposed no language restriction in our inclusion criteria for the search. The full search strategy is shown in the Supplementary Material (Appendix 1).

After conducting the literature search, we imported all the retrieved studies into Rayyan software. To ensure accuracy, duplicates were removed by two researchers (AU and ND). Three investigators (CC, SC, and AU) independently screened the titles and abstracts of potentially eligible articles. Articles meeting the inclusion criteria underwent a full-text review in the second screening stage. Any conflicts were resolved through team discussions to ensure a final consensus.

We examined randomised controlled trials that investigated outcomes of telehealth interventions, such as case management, consultations, education, monitoring, and reminders about glycaemic control. The inclusion criteria were: (1) participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus (age ≥ 18 years old); (2) studies had to include at least one telehealth intervention that was compared to a control group that received traditional, standard, or usual care; (3) studies reporting glycaemic control measured by glycated haemoglobin; or (4) studies reporting secondary outcomes, such as fasting blood sugars, body mass indexes, systolic blood pressures, diastolic blood pressures, and lipid profiles. Given that type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus are distinct conditions with unique underlying causes and treatment strategies, each presenting distinct etiologies and risk factors, it is imperative to recognize that studies about type 1 diabetes mellitus may delve into different interventions, outcomes, or aspects compared to those focused on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Consequently, when studies encompass both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus, it is crucial that the outcomes for each group are reported separately to ensure meaningful comparisons, and summarizing results might be more straightforward when focusing on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Additionally, to ensure that grey literature collection is composed of more substantive and useful documents, the exclusion criteria were: (1) patients diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus; (2) data collection performed before March 11, 2020; (3) full text of the article unavailable; and (4) literature that contained insufficient information, such as reviews, case studies, conference abstracts, proceedings, and studies describing methodological protocols without results. Additionally, studies not written in English were excluded.

The study protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD42022381879 (Chaomuang et al., 2023).

2.2. Outcome measurements

We compared the primary and secondary outcomes between the intervention and control groups. The primary outcome was the participants’ glycated haemoglobin levels, and the secondary outcomes were their fasting blood sugars, body mass indexes, systolic blood pressures, diastolic blood pressures, and lipid profiles, including cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein, and low-density lipoprotein. All outcomes were reported as means and standard deviations (SD). If studies did not report the SD, we calculated the SD. using the upper and lower limits and sample size. Glycated haemoglobin values were presented as percentages in accordance with the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (Little et al., 2019); therefore, the values from studies that reported glycated haemoglobin in millimoles per mole were converted to glycated haemoglobin%. Likewise, fasting blood sugars reported in millimoles per mole were converted to milligrams per deciliter. Subgroup-specific prevalence information was collected from each eligible study and then was calculated based on the participants’ characteristics, including age, the continent of study, follow-up time, and type of intervention.

2.3. Data extraction

We (ND and CC) developed a comprehensive data extraction form in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions guidelines (Higgins et al., 2019) and refined it with input from experts (SS, PB). To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of our findings, we piloted the form on a subset of included studies before extracting information from all studies (CC, SC, and ND). Our data extraction included publication details (title, journal, and year), author information (names, affiliations, funding, and conflicts of interest), study characteristics (start and end date, country, design, purpose, blinding and randomization method, and statistical analyses), participant demographics, intervention details, comparison details, and results (time points for follow-up, primary and secondary outcomes with their standard deviations, standard errors of means, 95 % confidence intervals, statistical significance, and the validation tools for the measurements). We classified all the telehealth interventions according to the World Health Organization's recommendations, as described elsewhere (Kuan et al., 2022a), including remote consulting, remote monitoring, medical data transmission, and remote case management. Both qualitative and quantitative data were extracted independently by three researchers (CC, SC, ND). Discrepancies were resolved through team discussions and expert input (SS, PB).

2.4. Quality assessment of the included studies

All the included studies were independently assessed for methodological quality by five researchers (NC, CC, SC, SS, PN) using a revised Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for randomised controlled trials (Sterne et al., 2019). The tool assessed potential biases arising from the randomisation process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and selection of reported results. Disagreements in assessment were resolved through discussion and review of study materials to reach a consensus.

2.5. Certainty of evidence

The overall quality of the evidence for the meta-analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes ranged from low to high quality. The summary of the quality of evidence according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation system is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of findings: certainty of evidence.

. . |

2.6. Data synthesis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software. A p-value of less than .05 indicated statistical significance. We acknowledge the potential for heterogeneity in our analysis. As a result, we chose to utilize a random-effects model, which is well-suited for combining results when there may be variability both within and between the included primary studies, among other sources of variation. The random-effects model and a 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI) were used to determine the pooled effect of telehealth versus usual care for continuous data, with I² inconsistency statistics used to examine statistical heterogeneity. Higgins et al. (2021) recommendations were used to classify heterogeneity levels as high (>75 %), moderate (25–75 %), and low (<25 %). (Higgins et al., 2021) In cases where heterogeneity was detected, we attempted to identify potential sources of heterogeneity. If appropriate, we performed a subgroup analysis based on participant characteristics. Funnel plot asymmetry tests, Begg's tests, and Egger's regression tests were used to assess publication bias for each outcome.

3. Results

Initially, we identified 669 studies from electronic databases (EMBASE n = 362, PubMed n = 218, Scopus n = 89). After removing duplicates, 543 articles were screened based on eligibility criteria, and 259 full-text articles were assessed. Ultimately, 21 studies remained after screening full text, but nine were excluded due to unintelligibility. In the Supplementary Material, Appendix 2 shows the list of excluded studies at the full-text screening stage with brief reasons. Finally, 12 studies (Bao et al., 2022; Esferjani et al., 2022; Franco et al., 2022; Gómez et al., 2022; Haghighinejad et al., 2022; Heald et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2022; Leong et al., 2022; Molavynejad et al., 2022; Pamungkas et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2022; Yin et al., 2022) were included in the meta-analysis. The study selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Selection flow diagram.

An overview of the characteristics of all the eligible studies is presented in Table 2. Each of the studies incorporated at least a single intervention, but four of the studies employed a more complex design and implemented more than two interventions (Bao et al., 2022; Pamungkas et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2022; Yin et al., 2022). The studies involved a total of 1498 participants, with 51.82 % females and 48.18 % males in the intervention groups, and 48.22 % females and 51.78 % males in the control groups. The participants’ overall mean age was 57.75 years. Their overall, average baseline glycated haemoglobin was 8.47 %.

Table 2.

Characteristic of included studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

| First Author | Extra criteria | Location of study | Number of participants I/C |

Age (mean±S.D.) (years) |

Sex M/F (%) |

T2DM duration (years) |

Telehealth intervention | Control | Follow-up duration (weeks) |

Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bao S, Bailey R, Calhoun P, Beck RW, 2022 (A: Age < 65 year) |

Aged 30–79 years, HbA1C 7.8–11.4 % | US (North America) |

89/44 |

I: 53±7 C: 55±7 |

I: 47/53 C: 50/50 |

I: 13±9 C: 14±8 |

Continuous glucose monitoring | Blood glucose monitoring (BGM) | 32 | HbA1C, FBG, TIR, Medication change, Hypoglycemic events, DKA events, Other adverse events, QoL |

| Bao S, Bailey R, Calhoun P, Beck RW, 2022 (B: Age ≥ 65 year) |

Aged 30–79 years, HbA1C 7.8–11.4 % | US (North America) |

27/15 | I: 68±3 C: 70±4 |

I: 48/52 C: 67/33 |

I: 16±9 C: 17±13 |

CGM | BGM | 32 | HbA1C, FBG, TIR, Medication change, Hypoglycemic events, DKA events, Other adverse events, QoL |

| Esferjani SV, Naghizadeh E, Albokordi M, Zakerkish M, Araban M. 2022 | Aged ≥ 60 years | Iran (Asia) |

59/59 | 63.5 ± 2.26 (Mean age total) |

I: 44.1/55.9 C: 47.5/52.5 |

I: 5.8 ± 2.47 C: 5.68±3.4 |

Online education via mobile phone | Routine care | 12 | HbA1C, Attitude, Self-efficacy, Social support |

| Franco DW, Alessi J, de Carvalho TR, Kobe GL, Oliveira GB, Knijnik CP, et al. 2022 | Available weekly phone calls during study | Brazil (South America) |

46/46 | I: 61.6 ± 9.2 C: 61.1 ± 8.9 |

I: 37/63 C: 32.6/67.4 |

I: 16.9 ± 9.9 C: 18±9.9 |

Phone callapplication and usual care | Usual care | 16 | HbA1C, BMI, SBP, DBP, Lipid profile, Self-management |

| Gómez AM, Henao DC, Vargas FL, Muñoz OM, Lucero OD, Jaramillo MG, et al. 2022 | HbA1C ≥ 6.5 %, Under basal-plus/basal-bolus insulin* or taking insulin ≥ 2 tabs/day | Columbia (South America) |

42/45 | I: 58.6 ± 10.6 C: 60.5 ± 12.8 |

I: 55/45 C: 54.2/45.8 |

I: 7.7 ± 3.64 C: 7.8 ± 6.5 |

Application | Usual care | 12 | HbA1C, FBG, BMI, Hypo-hyperglycemic events, Hospitalization |

| Haghighinejad H, Liaghat L, Malekpour F, Jafari P, Taghipour K, Rezaie M, et al. 2022 | Aged 30–70 years, HbA1C > 7 %, No insulin therapy, had no other disease, able to use telephone | Iran (Asia) |

56/56 | I: 54±8.5 C: 57.5 ± 9 |

I: 40/60 C: 50/50 |

NA | Text message daily | Routine care | 12 | HbA1C, FBG, Self-management |

| Heald AH, Gimeno LA, Gilingham E, Hudson L, Price L, Saboo A, et al. 2022 |

HbA1C > 7.5 % | UK (Europe) |

17/19 | NA | NA | NA | Mobile application and usual care | Usual care | 24 | HbA1C, BMI |

| Khan YH, Alzarea AI, Alotaibi NH, Alatawi AD, Khokhar A, Alanazi AS, et al. 2022 | Aged > 30 years, HbA1C > 7 % | Saudi Arabia (Asia) |

54/55 | I: 58.8 ± 7.51 C: 57.8 ± 7.88 |

I: 59.3/40.7 C: 60/40 |

I: 7.3 ± 2.17 C: 6.42±3.37 |

Phone call/message or |

Usual care | 24 | HbA1C, SBP, DBP, Lipid profile, Hypoglycemic events, Knowledge, Self-care practice, Medication adherence |

| Leong CM, Lee TI, Chien YM, Kuo LN, Kuo YF, Chen HY. 2022 | HbA1C > 6 %, install the LINE application | Taiwan (Asia) |

91/90 | I: 59±11.4 C: 58.1 ± 11.9 |

I: 73.6/26.4 C: 63.3/36.7 |

I: 10.4 ± 9 C: 10.3 ± 8.1 |

Videos, chat room, messages, website, and usual care | Usual care | 12 | HbA1C, Knowledge, Attitude, Self-care |

| Molavynejad S, Miladinia M, Jahangiri M. 2022 | Were Diagnosed T2DM ≥ 1 year, had no other chronic disease | Iran (Asia) |

126/126 | I: 45.9 ± 9.09 C: 48.3 ± 7.61 |

I: 40.7/59.3 C: 54.2/45.8 |

I: 6.34±5.12 C: 5.43±5.38 |

Video education | Education via pamphlet | 12 | HbA1C, FBG, Lipid profile, Satisfaction |

| Pamungkas RA, Usman AM, Chamroonsawasdi K. 2022 | Aged > 35–59 years, HbA1C > 7 %, Living with DM > 2 years, | Indonesia (Asia) |

30/30 | I: 56.2 ± 7.63 C: 54.5 ± 9.2 |

I: 20/80 C: 36.7/63.3 |

NA | Mobile application, online consultation, phone call/line call, and messages | Routine care | 12 | HbA1C, BMI, SBP, DBP, Lipid profile, Screen complication, Self-management |

| Xia SF, Maitiniyazi G, Chen Y, Wu XY, Zhang Y, Zhang XY, et al. 2022 | Able to use the Wechat application, including can send and receive SMS, voice calls, and video calls | China (Asia) |

78/78 | I: 61.9 ± 12.59 C: 57.96±12.3 |

I: 63/37 C: 64/36 |

I: 10.8 ± 8.88 C: 10.09±7.09 |

Web-based education and mobile application | Usual care | 24 | HbA1C, FBG, BMI, SBP, DBP, Lipid profile, |

| Yin W, Liu Y, Hu H, Sun J, Liu Y, Wang Z. 2022 | Aged > 18–55 years, HbA1C > 7–10 %, BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2, diagnose T2DM > 6 months, Able to use internet and smartphone | China (Asia) |

60/60 | I: 47.5 ± 15.81 C: 47±17.78 |

I: 43/57 C: 38/62 |

I: 4 ± 7.9 C: 3 ± 5.93 |

Application | Conventional health education | 24 | HbA1C, FBG, BMI, SBP, DBP, Lipid profile, Renal function test, Waist-hip ratio |

Note:.

*Basal plus insulin therapy = a diabetes management approach combining a basal insulin regimen with additional short-acting insulin or medications for flexible mealtime control. Basal-bolus insulin therapy = a combination of long-acting basal insulin for background control and short-acting bolus insulin before meals for precise blood sugar management in diabetes.

A = group A, B = group B, BMI = Body mass index, CGM=continuous glucose monitoring, DBP = Diastolic blood pressure, SBP = Systolic blood pressure, DKA = Diabetic ketoacidosis, DM = Diabetes mellitus, FBG = Fasting blood glucose, HbA1C = Hemoglobin A1C, I = Intervention group, C = Control group, kg/m2 = kilogram per meter square QoL = Quality of Life, T2DM = Type 2 diabetes mellitus, TIR = time in range, SD= Standard deviation,.

UK = United Kingdom, US = United States, LINE = Freeware application for instant communications on electronic devices operated by LY Corporation.

Most of the studies (eight ) were conducted in Asia, including Iran (three) (Esferjani et al., 2022; Haghighinejad et al., 2022; Molavynejad et al., 2022), China (two) (Xia et al., 2022; Yin et al., 2022), Indonesia (Pamungkas et al., 2022), Saudi Arabia (Haghighinejad et al., 2022), and Taiwan (Leong et al., 2022). Out of the studies included in the analysis, three were carried out in the Americas, specifically in Brazil (Franco et al., 2022), Colombia (Gómez et al., 2022), and the United States. (Bao et al., 2022) The last remaining study was conducted in Europe (the United Kingdom) (Heald et al., 2022).

The follow-up duration of the telehealth interventions ranged from 12 to 32 weeks, with an average of 18 weeks. The studies used various types of telehealth interventions, such as (1) remote monitoring like continuous glucose monitoring (Bao et al., 2022) and application monitoring (Gómez et al., 2022); (2) remote consulting, such as online education (Esferjani et al., 2022), mobile applications (Franco et al., 2022; Heald et al., 2022), short text messages (Haghighinejad et al., 2022), the integration of websites, text messages, VDO tele-education, chatrooms, phone calls, messages, and e-mails (Khan et al., 2022; Leong et al., 2022; Molavynejad et al., 2022); and (3) remote case management, which included both consulting and monitoring. (Pamungkas et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2022; Yin et al., 2022) Most of the studies included in the analysis compared the effectiveness of the interventions against usual care, with the control groups receiving normal routine care.

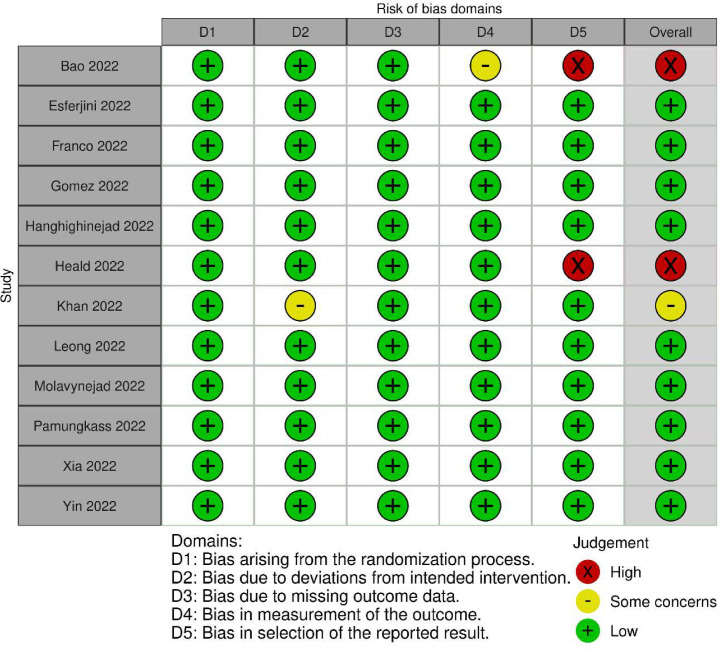

In general, the methodological quality of the studies included in the analysis varied significantly. Most of the studies were deemed to be at a low risk of bias. Specifically, nine out of the 12 studies (Esferjani et al., 2022; Franco et al., 2022; Gómez et al., 2022; Haghighinejad et al., 2022; Leong et al., 2022; Molavynejad et al., 2022; Pamungkas et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2022; Yin et al., 2022) were classified as having a low risk of bias. However, two studies (Bao et al., 2022; Heald et al., 2022) were determined to have a high risk of bias, while one study (Khan et al., 2022) was deemed to have a moderate risk of bias. The risk of bias assessment is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Cochrane risk of bias summary based on author's judgements.

Among the 12 randomised controlled trials that enrolled participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus during the COVID-19 pandemic, those that had higher baseline values for glycated haemoglobin had the greatest observed effectiveness in terms of improving glycated haemoglobin (Gómez et al., 2022; Leong et al., 2022). In addition, 11 studies (Bao et al., 2022; Esferjani et al., 2022; Franco et al., 2022; Gómez et al., 2022; Haghighinejad et al., 2022; Heald et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2022; Leong et al., 2022; Molavynejad et al., 2022; Pamungkas et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2022) reported clinically meaningful reductions in glycated haemoglobin level (0.5 % or more) among their telehealth intervention groups, while only one reported a similar reduction in their control groups (Yin et al., 2022).

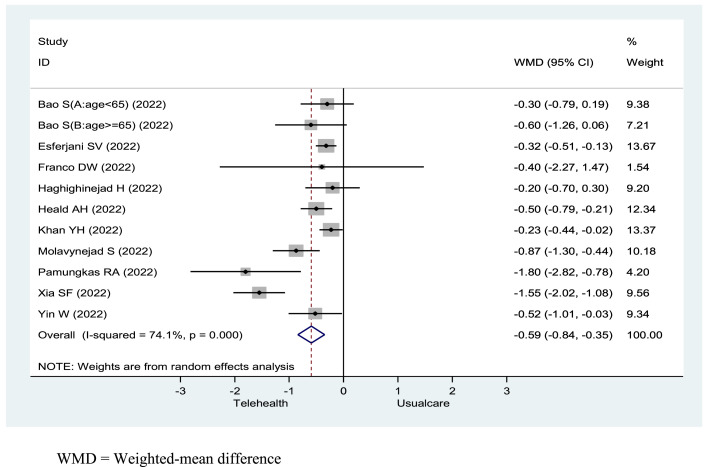

Initially, the meta-analysis showed that, on average, participants who received a telehealth intervention achieved a greater reduction in glycated haemoglobin compared to those who received usual care, with a weighted mean difference (WMD) of −0.63 (95 %CI −0.95 to −0.31) and a high heterogeneity (I2 = 89.2 %) (See the forest plot in the Supplementary Material, Appendix 3). Heterogeneity was detected, and two randomised controlled trials were found to report outlier levels of glycated haemoglobin at baseline (12.4 % and 6.8 %, respectively) (Gómez et al., 2022; Leong et al., 2022). After excluding these two randomised controlled trials, the results were similar. The final analysis showed that the telehealth interventions’ impact on the improvement of glycated haemoglobin had a WMD of −0.59 (95 % CI −0.84 to −0.35, p < .001) and moderate heterogeneity (I² = 74.1 %) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot shows effectiveness of telehealth compared with usual care on HbA1C in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Table 3 shows that telehealth interventions were associated with improved outcomes in secondary measures. Fasting blood sugar decreased by 16.1 %, body mass index decreased by 1.5 %, and low density lipoprotein decreased by 7.8 % in participants who received telehealth interventions compared to those who received usual care. Sub-group and sensitivity analyses based on age, follow-up time, type of intervention, and continent showed that telehealth had a significant impact on reducing glycated haemoglobin levels in all sub-groups, regardless of whether a fixed or random effects model was used (Table 4).

Table 3.

Effect of telehealth compared with usual care on secondary outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

| Outcome (Number of pooled studies) |

WMD (95 %CI) |

P-value | I (Goyal et al., 2022) (%) | P-value for heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBS (n = 6) | −16.06 (−29.64, −2.48) | 0.02 | 57.9 | 0.068 |

| BMI (n = 6) | −1.5 (−1.98, −1.02) | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.557 |

| SBP (n = 5) | −2.3 (−9.41, 4.82) | 0.527 | 77.2 | 0.002 |

| DBP (n = 5) | −1.71 (−4.11,0.69) | 0.163 | 43.1 | 0.134 |

| Lipid profile | ||||

| Cholesterol (n = 5) | −6.80 (−16.17, 2.57) | 0.155 | 78.9 | 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (n = 5) | −9.44 (−22.45, 3.56) | 0.155 | 67.3 | 0.016 |

| HDL (n = 6) | 2.07 (−0.70, 4.84) | 0.144 | 88.0 | <0.001 |

| LDL (n = 6) | −7.78 (−14.69, −0.88) | 0.027 | 82.3 | <0.001 |

*Note:.

FBS = Fasting blood sugar, BMI = Body mass index, SBP = Systolic blood pressure, DBP = Diastolic blood pressure, HDL = High-density lipoprotein, LDL = Low-density lipoprotein.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses.

| Characteristics | HbA1C |

BMI |

FBS |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies (n) |

WMD (95 %CI) | No. of studies (n) |

WMD (95 %CI) | No. of studies (n) |

WMD (95 %CI) | |

| Overall | 10 | −0.59 (−0.84, −0.35) | ||||

| Models | ||||||

| Fixed effects model | 10 | −0.45 (−0.55, −0.34) | 5 | −1.50 (−1.98, −1.02) | 4 | −17.70 (−25.94, −9.47) |

| Random effects model | 10 | −0.59 (−0.84, −0.35) | 5 | −1.50 (−1.98, −1.02) | 4 | −16.06 (−29.64, −2.48) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| < 65 | 10 | −0.60 (−0.86, −0.33) | 5 | −1.50 (−1.98, −1.02) | 4 | −16.06 (−29.64, −2.48) |

| ≥ 65 | 1 | −0.60 (−1.26, 0.06) | NA | NA | ||

| Follow-up time | ||||||

| ≥ 6 months | 5 | −0.60 (−0.96, −0.24) | 3 | −1.63 (−2.15, −1.12) | 2 | −19.64 (−31.39, −7.88) |

| < 6 months | 5 | −0.62 (−1.05, −0.18) | 2 | −0.60 (−1.94, 0.74) | 2 | −14.45 (−43.48, 14.57) |

| Types of intervention | ||||||

| Remote monitoring | 1 | −0.41 (−0.80, −0.01) | NA | NA | ||

| Remote consultation | 6 | −0.39 (−0.56, −0.21) | 3 | −1.20 (−1.87, −0.54) | 2 | −14.45 (−43.48, 14.57) |

| Remote case management | 3 | −1.23 (−2.04, −0.42) | 2 | −1.82 (−2.52, −1.13) | 2 | −19.64 (−31.39, −7.88) |

| Continent | ||||||

| America | 2 | −0.41 (−0.79, −0.02) | 1 | 0.70 (−4.29, 5.69) | NA | |

| Asia | 7 | −0.68 (−1.03, −0.33) | 3 | −1.59 (−2.23, −0.94) | 4 | −16.06 (−29.64, −2.48) |

| Europe | 1 | −0.50 (−0.79, −0.21) | 1 | −1.40 (−2.16, −0.64) | NA | |

*Note:.

HbA1C = Hemoglobin A1C, FBS = Fasting blood sugar, BMI = Body mass index, WMD = Weighted mean differences, NA = Not available, No. = Number, n = Sample.

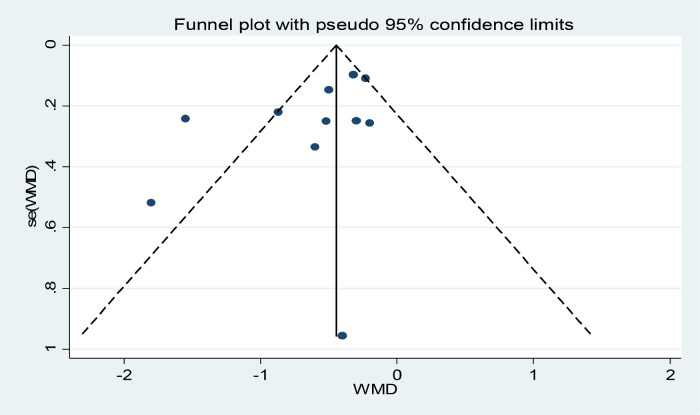

Funnel plots, Begg's, and Egger's tests were conducted to assess publication bias related to the number of included articles. The funnel plot inspection revealed minimal potential for publication bias. Begg's and Egger's tests did not indicate evidence of a small-studies effect (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Publication bias.

4. Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we showed that telehealth interventions were effective in improving glycaemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus, with significant reductions in glycated haemoglobin and improvements in other outcomes. The superior effectiveness of telehealth interventions over usual care can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, advanced technology has been instrumental in the development and widespread adoption of telehealth. Telehealth relies on telecommunication technologies, such as video conferencing, remote monitoring devices, SMS, and mobile health applications to deliver healthcare services and information. These technologies enable the collection and transmission of health data, facilitate communication between patients and healthcare providers, and enable the remote delivery of care (Frias et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2020; Sheehan et al., 2012). Without the availability of such advanced technology, the implementation and delivery of telehealth services would not have been possible.

Secondly, telehealth overcomes geographical barriers and increases access to care, particularly in areas where healthcare services are limited or not available. Patients can remotely connect with healthcare providers and receive care, regardless of their location. This is especially beneficial for patients living in rural or remote areas who may face challenges in accessing healthcare services due to geographical barriers, limited transportation options, or restrictions on face-to-face visits. Telehealth technologies can help bridge this gap by allowing patients to receive care from healthcare providers. This has allowed telehealth to emerge as a crucial tool that aids in the process of providing patient care. Because it facilitates the collection and exchange of data and information between patients and healthcare professionals, telehealth has the potential to generate new shared knowledge and collective wisdom. This exchange of information can strengthen patients’ self-management capacities and engagement in their care trajectory, thus enhancing their overall health outcomes (Ji et al., 2020; Khoshrounejad et al., 2021; Rockwell and Gilroy, 2020; Speyer et al., 2018; Vitaceae et al., 2018). Moreover, telehealth technologies can help reduce healthcare costs by minimizing the need for in-person visits, which can be expensive and time-consuming for patients (Ben-Assuli, 2022; Niu et al., 2022; Snoswell et al., 2020; Monaghesh and Hajizadeh, 2020). In summary, it is explicitly clear that telehealth interventions streamlined healthcare delivery processes, reduced administrative tasks, or optimized resource utilization. These efficiency gains can lead to cost reductions indirectly, even if a formal cost analysis is not performed. In addition, due to a decrease in hospital admissions or readmissions among patients using telehealth services, we have inferred potential cost savings from reduced healthcare utilization. Moreover, telehealth can save patients time and expenses associated with travel to healthcare facilities. While this might not directly offset the cost of telehealth implementation, it can imply cost savings for patients.

Thirdly, telehealth had gained global attention among scientific communities well before the COVID-19 pandemic, as evidenced by the number of existing studies (Speyer et al., 2018; Vitaceae et al., 2018). However, the pandemic has served as a driving force for the development and adoption of telehealth technologies. Health systems have rapidly innovated existing and created new virtual health facilities and telecare platforms to minimize the effects of the pandemic. Additionally, to address the pandemic's threat, telehealth was rapidly and extensively implemented to maintain the continuity of care through multi-purpose technology platforms that were considered virtual healthcare facilities (Blandford et al., 2020; Bouabida et al., 2022).

Telehealth can have a positive effect on patient safety and outcomes. Nevertheless, telehealth comes with risks, including exacerbating the digital divide, poor software engineering, and security breaches. Future telehealth platforms must be secure, reliable, and flexible enough to accommodate the demands of regulatory, professional, and health-care organization requirements. These platforms should all be updated regularly (Bouabida et al., 2022). In addition, unlike their counterparts with higher socio-economic status, individuals with lower socio-economic status may not be able to reap the full benefits of telehealth care services. In fact, their experiences using telecare may be even worse than with their use of traditional health services. This can be attributed to several factors, such as the level of education and familiarity with the fundamental aspects of connected devices' features, technology, and the functionality of telehealth platforms. Additionally, they may lack the financial resources to acquire telehealth devices, and the inability to access a reliable internet network may also hinder their access to telehealth services (Hamadi et al., 2021; Folk et al., 2021; Gajarawala and Pelkowski, 2021).

5. Limitations

There are several limitations to our review that should be considered. First, we searched only three databases, so there is a possibility that some studies may have been published in other databases that may have been overlooked. Nevertheless, after testing with funnel plots, Egger's tests, and Begg's tests, no small study effect was observed. Second, since we included telehealth interventions from only randomised controlled trials, which are considered the gold standard of study design, the number of studies available for the meta-analysis was limited. However, relying solely on randomised controlled trials gave us greater confidence in the observed effects because it reduced the risk of bias from residual effects that may be present in observational studies. Third, our study populations were diverse in terms of their geographic locations and contexts, which means that there may have been significant variations in the healthcare systems and typical treatment protocols. Additionally, the dominance of eight Asian countries among 12 studies does indeed have implications for the generalizability of our results beyond this region. While our study aimed to provide insights into the effectiveness of telehealth for diabetes management during the COVID-19 pandemic, the concentration of studies from Asia limits the extent to which our findings can be extrapolated to other regions with potentially different healthcare systems and cultural contexts. Fourth, the effectiveness of telehealth can be influenced by the healthcare providers involved, as well as the specific characteristics of the providers. Providers who are well-trained in using telehealth tools and effectively communicating with patients through remote channels are more likely to deliver high-quality care. A strong provider-patient relationship is important for effective healthcare delivery. Telehealth can sometimes impact the interpersonal dynamics between providers and patients, potentially affecting patient satisfaction and treatment adherence. Nevertheless, further research in this area presents an intriguing opportunity. Exploring the specific characteristics and practices of healthcare providers within the context of telehealth could yield valuable insights and contribute to the ongoing improvement of telehealth services. Although subgroup analysis was not performed, we successfully addressed the research question regarding the effectiveness of telehealth on glycaemic control in patients with diabetes. Fifth, moderate heterogeneity was observed in our analysis, suggesting that there was considerable variation in the results among the included studies. This variation may be attributed to several factors, such as differences in study populations, interventions, and outcome measures. To address this issue and potentially reduce heterogeneity, focusing on specific terms like mHealth or telemedicine for further analysis is a valid approach. Narrowing down the analysis to one or two terms can help in creating a more homogeneous subset of studies with similar interventions or contexts, which might lead to more consistent and interpretable results. In addition, it is essential to approach the interpretation of the results with caution due to the presence of heterogeneity. Lastly, most studies reported on clinical parameters and had a short-term intervention duration. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the outcomes better. The fact that the results were consistent across separate analyses of both short- and long-duration interventional periods suggests that the findings can be considered reliable and applicable.

6. Conclusions and implications

We suggest that healthcare professionals should utilize and develop telehealth for diabetes management and explore ways to leverage it to provide the most optimal diabetes care services possible. Moreover, preparing for telehealth implementation would be beneficial in future pandemics based on the experience gained during the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the significant impact of telehealth on glycaemic control in these populations, policymakers and guideline developers should consider supporting the use of telehealth as an alternative to maximize patients’ outcomes. Future research should prioritize selecting large randomised control trials to confirm the effectiveness of telehealth in managing type 2 diabetes mellitus during the lockdown. Additionally, it would be beneficial to explore the potential use of telehealth in managing the care of patients with other chronic diseases. Finally, the cost-effectiveness of utilizing telehealth should be assessed.

Funding sources

This study was supported by Suranaree University of Technology (Grant number: HS8-807-66-12-05) and the University of Phayao via the Unit of Excellence for Clinical Outcomes Research and Integration (UNICORN; Grant number: FF66-UoE004). The funding sources did not have any involvement with the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or manuscript production.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chantira Chiaranai: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Saranya Chularee: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Surasak Saokaew: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Patraporn Bhatarasakoon: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Adinat Umnuaypornlert: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Natthaya Chaomuang: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Nudchaporn Doommai: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. Porntip Nimkuntod: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijnsa.2023.100169.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Bao S., Bailey R., Calhoun P., et al. Effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in older adults with type 2 diabetes treated with basal insulin. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2022;24(5):299–306. doi: 10.1089/dia.2021.0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Assuli O. Measuring the cost-effectiveness of using telehealth for diabetes management: a narrative review of methods and findings. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2022;163 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104764. JulEpub 2022 Apr 15. PMID: 35439671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biamonte E., Pegoraro F., Carrone F., et al. Weight change and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients during COVID-19 pandemic: the lockdown effect. Endocrine. 2021;72(3):604–610. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02739-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandford A., Wesson J., Amalberti R., et al. Opportunities and challenges for telehealth within, and beyond, a pandemic. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8(11):e1364–e1365. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30362-4. Epub 2020 Aug 10. PMID: 32791119; PMCID: PMC7417162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouabida K., Lebouché B., Pomey M.P. Telehealth and COVID-19 pandemic: an overview of the telehealth use, advantages, challenges, and opportunities during COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare. 2022;10(11):2293. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10112293. (Basel)Nov 16PMID: 36421617; PMCID: PMC9690761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaomuang N., Chiaranai C., Chularee S., et al. 2023 The effects of telehealth on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus during Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO2022 CRD42022381879 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022381879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chiaranai C., Chularee S., Prawatwong W., Srituanglueng S. Two-way SMS reminders for medication adherence and quality of life in adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2023;27(3):457–471. doi: 10.60099/prijnr.2023.262244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A., Jit M., Warren-Gash C., et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8(8):1003–1017. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30264-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J., Wu D., Flynn D., et al. Efficacy of telemedicine on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. World J. Diabetes. 2021;12(2):170–197. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v12.i2.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esferjani S.V., Naghizadeh E., Albokordi M., et al. Effectiveness of a mobile-based educational intervention on self-care activities and glycemic control among the elderly with type 2 diabetes in southwest of Iran in 2020. Arch. Public Health. 2022;80(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13690-022-00957-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasil A., Biadgo B., Abebe M. Glycemic control and diabetes complications among diabetes mellitus patients attending at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2018;12:75–83. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S185614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folk J.B., Schiel M.A., Oblath R., et al. The transition of academic mental health clinics to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2021;61 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.06.003. 277–90.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco D.W., Alessi J., de Carvalho T.R., et al. The impact of a telehealth intervention on the metabolic profile of diabetes mellitus patients during the COVID-19 pandemic-a randomized clinical trial. Prim. Care Diabetes. 2022;16(6):745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2022.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias J., Virdi N., Raja P., et al. Effectiveness of digital medicines to improve clinical outcomes in patients with uncontrolled hypertension and type 2 diabetes: prospective, open-label, cluster-randomized pilot clinical trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e246. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7833. https://www.jmir.org/2017/7/e246 URL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajarawala S.N., Pelkowski J.N. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J. Nurse Pract. 2021;17:218–221. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Molina L., Lewis-Mikhael A.M., Riquelme-Gallego B., et al. Improving type 2 diabetes mellitus glycaemic control through lifestyle modification implementing diet intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020;59(4):1313–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00394-019-02147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez A.M., Henao D.C., Vargas F.L., et al. Efficacy of the mHealth application in patients with type 2 diabetes transitioning from inpatient to outpatient care: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022;189 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong E., Baptista S., Russell A., et al. My diabetes coach, a mobile app-based interactive conversational agent to support type 2 diabetes self-management: randomized effectiveness-implementation trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(11):e20322. doi: 10.2196/20322. Nov5PMID: 33151154; PMCID: PMC7677021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal R., Jialal I., Castano M. Diabetes mellitus type 2 (nursing). InStatPearls [Internet] 2022. [cited 2022 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568737/.

- Haghighinejad H., Liaghat L., Malekpour F., et al. Comparing the effects of SMS-based education with group-based education and control group on diabetes management: a randomized educational program. BMC Fam. Pract. 2022;23(1):209. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01820-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamadi H.Y., Zhao M., Haley D.R., et al. Medicare and telehealth: the impact of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021;28:43–48. doi: 10.1111/jep.13634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heald A.H., Gimeno L.A., Gilingham E., et al. Enhancing type 2 diabetes treatment through digital plans of care. First results from the East Cheshire Study of an App to support people in the management of type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022;11(3):1–4. doi: 10.1097/XCE.0000000000000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P.T., Thomas J., Chandler J., et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0. 2019. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v6 (accessed Nov 18, 2022).

- Higgins J.P.T., Thomas J., Chandler J., et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0. 2021.

- Hildebrand J.A., Billimek J., Lee J.A., et al. Effect of diabetes self-management education on glycemic control in Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020;103(2):266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Ma Z., Peppelenbosch M.P., et al. Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and health-care resource availability. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8:e480. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30068-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Y.H., Alzarea A.I., Alotaibi N.H., et al. Evaluation of impact of a pharmacist-led educational campaign on disease knowledge, practices and medication adherence for type-2 diabetic patients: a prospective pre-and post-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19(16):10060. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191610060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshrounejad F., Hamednia M., Mehrjerd A., et al. Telehealth-based services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of features and challenges. Front. Public Health. 2021;9:977. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.711762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan P.X., Chan W.K., Fern Ying D.K., et al. Efficacy of telemedicine for the management of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit. Health. 2022;4(9):e676–e691. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00124-8. SepPMID: 36028290; PMCID: PMC9398212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan P.X., Chan W.K., Ying D.K., et al. Efficacy of telemedicine for the management of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Digit. Health. 2022;4(9):e676–e691. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong C.M., Lee T.I., Chien Y.M., et al. Social media–delivered patient education to enhance self-management and attitudes of patients with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022;24(3):e31449. doi: 10.2196/31449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R.R., Rohlfing C., Sacks D.B. The national glycohemoglobin standardization program: over 20 years of improving hemoglobin A1C measurement. Clin. Chem. 2019;65(7):839–848. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.296962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molavynejad S., Miladinia M., Jahangiri M. A randomized trial of comparing video telecare education vs. in-person education on dietary regimen compliance in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a support for clinical telehealth Providers. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022;22(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s12902-022-01032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghesh E., Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1193. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu B., Mukhtarova N., Alagoz O., et al. Cost-effectiveness of telehealth with remote patient monitoring for postpartum hypertension. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(25):7555–7561. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1956456. DecEpub 2021 Sep 1. PMID: 34470135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojo O., Wang X.H., Ojo O.O., et al. The effects of COVID-19 lockdown on glycaemic control and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19(3):1095. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamungkas R.A., Usman A.M., Chamroonsawasdi K. A smartphone application of diabetes coaching intervention to prevent the onset of complications and to improve diabetes self-management: a randomized control trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2022;16(7) doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport M., Chetrit A., Cantrell D., et al. Years of potential life lost in pre-diabetes and diabetes mellitus: data from a 40-year follow-up of the Israel study on glucose intolerance, obesity and hypertension. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2021;9(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell K.L., Gilroy A.S. Incorporating telemedicine as part of COVID-19 outbreak response systems. Am. J. Manag. Care. 2020;26(4):147–148. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2020.42784. AprPMID: 32270980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Roso M.B., Knott-Torcal C., Matilla-Escalante D.C., et al. COVID-19 lockdown and changes of the dietary pattern and physical activity habits in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2327. doi: 10.3390/nu12082327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saragih I.D., Tarihoran D.E., Batubara S.O., et al. Effects of telehealth interventions on performing activities of daily living and maintaining balance in stroke survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022;31(19–20):2678–2690. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan B., Lee Y., Rodriguez M., et al. A comparison of usability factors of four mobile devices for accessing healthcare information by adolescents. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2012;3(4):356–366. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2012-06-RA-0021. PMID: 23227134; PMCID: PMC3517216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snoswell C.L., Taylor M.L., Comans T.A., et al. Determining if telehealth can reduce health system costs: scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(10):e17298. doi: 10.2196/17298. Oct 19PMID: 33074157; PMCID: PMC7605980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speyer R., Denman D., Wilkes-Gillan S., et al. Effects of telehealth by allied health professionals and nurses in rural and remote areas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2018;50:225–235. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J.A.C., Savović J., Page M.J., et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H., Saeedi P., Karuranga S., et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022;183 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The American Diabetes Association [ADA] Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:S83–S96. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The American Diabetes Association [ADA] Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Supplement_1):S60–S82. doi: 10.2337/dc22-s005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The American Diabetes Association [ADA] Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Supplement_1):S125–S143. doi: 10.2337/dc22-s009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). Telemedicine and telehealth [internet]. 2020. [cited to 2022 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/topic/health-it-health-care-settings/telemedicine-and-telehealth.

- Vitaceae M., Montini A., Comini L. How will telemedicine change clinical practice in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2018;12 doi: 10.1177/1753465818754778. 1753465818754778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO-ITU global standard for accessibility of telehealth services [internet]. 2022. [cited to 2022 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240050464.

- Xia S.F., Maitiniyazi G., Chen Y., et al. Web-based TangPlan and WeChat combination to support self-management for patients with type 2 diabetes: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10(3):e30571. doi: 10.2196/30571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W., Liu Y., Hu H., et al. Telemedicine management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in obese and overweight young and middle-aged patients during COVID-19 outbreak: a single-center, prospective, randomized control study. PLoS One. 2022;17(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Su B., Price G., et al. Glycemic control, diabetic complications, and risk of dementia in patients with diabetes: results from a large UK cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(7):1556–1563. doi: 10.2337/dc20-2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Ley S.H., Hu F.B. Global etiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):88–98. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.