Abstract

Background

Nurses’ involvement of children in their care is essential to quality pediatric care. Various international guidelines stress the need for children's involvement in decisions and activities affecting their care and lives; widely known among them is the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. This convention gives children the right to participate in decisions and activities that affect their growth and development.

Objective

This study assessed the level of nursing staff involvement of children in care activities and the benefits they perceived from this involvement.

Design

Descriptive cross-sectional study.

Setting

Units of Evangelical Church of Ghana Hospital, Kpandai rendering services for children.

Participants

A total of 116 nursing staff members were invited to participate; 97 (84%) responded. The term "nurses" in this study includes unlicensed nursing assistants, as well as licensed professional nursing staff.

Methods

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze participants’ demographic characteristics and the nurses’ perceived benefits derived from children's involvement in care activities. A Chi-square test was used to analyze associations between nurses’ demographic data and the level of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities at a significance level of p< 0.05.

Results

A majority (56.7%) of the nurses poorly involved children in their care activities. They either involved children to some extent or did not involve children at all. Nurses’ age and gender predicted involvement. Older nurses aged 30 and above (56.4%) were more likely to involve children in care activities than those under 30 (26.1%) [p=0.003]. Female nurses (31.7%) were marginally less likely to involve children in their care activities than their male colleagues (51.8%) [p=0.049]. Most of the nurses agreed to several impactful benefits of involving children in care activities, thus benefiting children, caregivers, and health professionals.

Conclusion

The overall level of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities was poor. Policy documents to safeguard children's rights in healthcare involvement must be developed and implemented from the national down to the hospital level to safeguard children's rights to healthcare involvement.

Keywords: Children, Children involvement, Children's rights, Children's rights in Ghana, Nursing care involvement, Pediatric Care, Patient participation

What is already known about the topic?

-

•

International policy makers widely recognize children's rights to involvement in their healthcare.

-

•

In the healthcare setting, parents, caregivers, and healthcare professionals are the major decision-makers for children.

-

•

Children's involvement in decision-making and activities in their care is generally low.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

What this paper adds.

-

•

The overall level of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities was low; however, there was a significant increase in children's involvement in care activities compared to previous studies.

-

•

We found a statistically significant association between the overall level of children's involvement in care activities and the age and gender of participants, although the latter was borderline.

-

•

Nurses in this study appeared to understand the benefits of children's involvement in care activities; however, they did not carry it out in their practice.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Background

Children are well-positioned to influence their growth, development, and general well-being through active involvement in issues and activities that directly or indirectly impact their lives (Gilljam et al., 2016; UNICEF, 2018b, 2018a). The concept of children's involvement in care could be described as assisting and supporting children to play active roles in their daily clinical care (Coyne, 2008; Coyne and Gallagher, 2011; Quaye et al., 2019). The approach of care involvement could be verbal or nonverbal (Berg et al., 2020; Miller, 2018). The focus on this in the nursing care context is to plan, prioritize, implement, and evaluate nursing care procedures with sick children, their parents/caregivers, and other cadres of healthcare professionals (Larsson et al., 2018; Phiri et al., 2019; Sabatello et al., 2018).

Historically, the healthcare setting has seen a highly – dominant, paternalistic view of patients and is often denoted as ‘children should be seen and not heard’ (D'Agostino et al., 2017). This practice of care sees parents as major decision-makers for children of all ages, as stated by Hallström & Elander (2004) and Quaye et al. (2019), irrespective of children's capability or competence in forming and expressing their views. Owing to this old-age practice, children receive little to no support from parents/caregivers and healthcare professionals during hospitalization (Mitchell et al., 2019). Researchers in these studies indicated that major decisions of children's hospitalization were made by healthcare professionals, as the healthcare professionals felt they knew how children behaved, thought, and felt in terms of their healthcare needs (Coyne, 2008; Hallström and Elander, 2005). In the cultural and social context, parents or the elderly are considered the best decision-makers for children due to their social status and level of maturity (Brown and Guralnick, 2012; Sabatello et al., 2018). Therefore parents, caregivers, and health professionals play key roles in the consultation processes of pediatric cases and thus have the power to influence, facilitate, or constrain a child's involvement in key decisions and activities of their care, as well as their social and cultural lives (Coyne, 2008; Coyne et al., 2014).

Despite this practice, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Bäckström, 1989), ratified by many nations since its adoption in 1989 (Aston and Lambert, 2010), has given children all the legal rights required to participate in decisions and activities that impact their lives, with other significant documents, legislation, and policies supporting the position of the convention (Aston and Lambert, 2010; Hallström and Elander, 2005). On a policy level, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child is the single major landmark framework for children's involvement and participation in decision-making and activities of their lives (Adonteng-kissi, 2021; Berrick et al., 2015; Koomson, 2016). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, according to Berrick et al. (2015), can be summarized under four basic fundamental principles: a) children's right to life, b) acting in the best interest of children, c) children's right to free expression and participation in matters of their concern, and d) children's right to no discrimination. Children's involvement and participatory rights can be examined under Article 3 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states that the best interest of a child comes first and must always be prioritized (UN General Assembly, 1989; UNICEF, 2009). This can be achieved only when children are given the opportunity to express their needs and preferences (active participation) in issues that influence their general well-being (Gutman et al., 2018; Nicholson et al., 2020). Articles 12 and 13 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Bäckström, 1989), further support children's involvement and participation in the rights of “freedom of expression” for children (Aston and Lambert, 2010; Quaye et al., 2019; UNICEF. 2009. State of the WorldR8S2Q1M7s Children: Celebrating 20 Years of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, 2009, UNICEF 2018b). Invariably, children have the fundamental human right to free expression in matters affecting their welfare (Berrick et al., 2015; Moore and Kirk, 2010).

According to Coyne (2008), Ghana was one of the first nations to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in February 1990, three months after its adoption. This convention became its first legislation on children's rights. Ghana further developed an act on children's rights, named the “Children's Act (Act 560)” in 1998, which was amended in 2016. This act draws its inspiration from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, providing that “no one shall deprive a child capable of forming opinions of the right to express an opinion, to be heard, and to participate in decisions that impact his or her wellbeing” (The Children's Act, 1998, Act 560, 2023). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Children's Act of Ghana, and other similar regulations mandate that children have “free expression” of their views. The right to express their views is not dependent upon their capacity to express a mature view; it is dependent only on their ability to form a view. Whether or not those views are mature is irrelevant (Laura, 2007).

The actual implementation of rights of children has not been successful, regardless of the numerous documents in favor of their right to be heard, consulted, and involved in the activities of their lives (Berrick et al., 2015; Coyne, 2008; Gilljam et al., 2016). According to a study by Bach and colleagues, which aimed to determine the level of influence children had on their care activities, only 27% of the children's parents had their decisions influenced by their children before the children underwent surgical treatment (Bach et al., 2020). Another study, conducted to empower children's participation in healthcare, revealed that some children felt satisfied with the level at which healthcare professionals incorporated their requests and preferences into their care. However, a significant majority of them expressed their displeasure at their lack of involvement in care (Gutman et al., 2018). A similar study conducted in England also revealed how young people experienced less care involvement. As a result of their limited involvement in care, they felt their behavior as young people might have directly influenced the healthcare providers’ reduced engagement (Aston and Lambert, 2010). In a study in Sweden, where 26 children aged 6–17 were interviewed to ascertain their level of care involvement, it was revealed that the wishes and preferences of children were ignored or not elicited at all during care in most cases (Coyne, 2008). Similarly, children's description of their non-participation in healthcare processes was reported to be 14 (8 younger and 6 older) out of 23 children, representing a 60% non-care involvement (Runeson et al., 2007).

The reduced or non-involvement of children in care activities could be attributed to multiple hindering factors linked to parents/caregivers, healthcare professionals, and the children themselves (Coyne, 2006; Harder et al., 2018; Rost et al., 2017). The major challenging factor for healthcare professionals is the ethical dilemma of involving children who are believed not to have the cognitive ability or capacity to make mature decisions (Grootens-Wiegers et al., 2017; Quaye et al., 2019). Berrick et al. (2015) and Phiri et al. (2019) revealed that the behavior of nurses affected the participation level of children in care activities. Historically, the healthcare setting has seen health professionals and parents being the major decision-makers for children. It is assumed that they know how children think and feel about treatment and hence do not require children's input during care (Hallström and Elander, 2005). Culturally, parents/caregivers assume the responsibility of making decisions for children, citing children's immaturity to act in their own best interests (Berrick et al., 2015; Coyne, 2006; Quaye et al., 2019).

Despite the numerous limitations to children's involvement in decisions and activities regarding their care, creating enabling environments for such involvement yields useful and positive health impacts on children, parents, and healthcare staff (Rasmussen et al., 2017). Researchers have found that involving children in healthcare processes, including the planning, implementation, and evaluation phases, enables them to see themselves as active participants in the healthcare team and, as a result, improves their cooperation level (Coyne, 2008; De Freitas, 2017; Hallström and Elander, 2004, 2005; UNICEF, 2018b). This catalyzes children's active involvement and participation during hospital admission (Coyne, 2006). Similarly, these researchers report that allowing the opinion of children to influence care decisions helps them develop a sense of themselves, giving them the self-confidence to take charge of their healthcare needs post-hospitalization. Furthermore, their sense of belongingness also becomes more evident, leading to better cooperation with clinicians and healthcare providers (Coyne et al., 2014; Hallström and Elander, 2004).

Despite numerous policies and regulations regarding children's rights to care involvement and participation, the actual implementation has been poor at all stages of children's growth and development. A literature search on children's participation or involvement in nursing care activities in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Ghana, yielded scant results. This paper, therefore, presents a preliminary quantitative analysis of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities, as well as their perceived benefits of such involvement. This quantitative study sought to generate new evidence in the area of children's rights implementation and the adherence to children's rights regarding healthcare involvement and participation.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study design was used. This research design provides a numerical description of a sample's trends, patterns, and attitudes within a given population of interest (Salkind, 2013). The attitude of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities was quantified, and descriptions were derived from the patterns and trends of the quantified data.

2.2. Setting

The study was conducted in the Evangelical Church of Ghana Hospital in Kpandai, Ghana, a 72-bed capacity health facility providing primary and secondary health services.

2.3. Study participants and eligibility criteria

The study population was made up of nurses, nursing assistants, and midwives working under the nursing and midwifery division of the Evangelical Church of Ghana Hospital. It comprised nurse practitioners, registered nurses, registered midwives, community health nurses, and nursing assistants clinical. Hereafter, the term "nurses" in this study includes unlicensed nursing assistants, as well as licensed professional nursing staff. Nurses and midwives with a minimum of six months of working experience with children were included in the study. We excluded nurses and midwives whose units did not offer nursing services to children.

2.4. Sampling and sample size

Convenience sampling was employed due to the small size of the target population. Therefore, a census of all the nursing staff and midwives in the hospital was conducted to recruit them. All 116 eligible nurses and midwives in the hospital were contacted and invited to participate in the study. However, only 97 agreed to participate.

2.5. Data collection and source of information

Data were gathered with an adapted Patient Participation Questionnaire used by Berg et al. (2020). The tool was adjusted by rephrasing the sentences to meet the study objective and target population. All variables in the sociodemographic section were retained except marital status, employment status, and comorbidity. The involvement section of the original questionnaire was categorized into involvement, information, communication, and relationship with children. Each of these had four questions, and all were retained except the relationship to staff, which had five questions, two of which we dropped.

The modified instrument was categorized into sections A, B, and C. The sociodemographic data of participants were gathered in Section A. Section B examined nurses’ involvement of children in their care activities. The areas examined were involvement in procedures, communication, information, and nurse-child relationship. Section C reviewed nurses’ perceived benefits of involving children in care activities. A pre-test of the modified instrument was conducted in a district hospital within Kpandai, involving 20 nurses and midwives who were randomly selected. The final study questions were all contained in the pre-test and were rephrased only for clarity following the pre-test. The pre-test's Cronbach alpha for the modified instrument was 0.76, as opposed to 0.89 for the original Patient Participation Questionnaire. The final modified instrument was reviewed by the expert panel of the Institutional Review Board of the Christian Health Association of Ghana before approval was given for data collection.

Between June 13 and July 13, 2022, we contacted participants at their respective units and took them through the study information sheet and consent form. Participants who signed the consent form were then given the study questionnaire.

2.6. Data management and analysis

Outcome parameters were described as absolute numbers and percentages for categorical variables or mean and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. The Chi-square test was used to test for an association between the level of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities and their sociodemographic characteristics. A statistically significant difference was defined as a p< 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

2.7. Ethical consideration

Ethics approval number CHAG-IRB06022022 was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Christian Health Association of Ghana. We provided participants with full disclosure of the purpose, content, risks, and benefits of the study. Participation was voluntary, as participants could exit the study at their will.

3. Results

The total sample size was 97, representing an 83.6% questionnaire response rate (out of 116 of the total invited to participate). Ten nurses were on annual leave, while 7 declined participation citing personal reasons. The results are presented in the ensuing sections.

3.1. Demographic characteristics

The ages of respondents ranged from 22 to 40, with a mean age of 30 (SD ±4). There were more male than female respondents. A majority of the participants had certificates as their basic educational qualification. Regarding respondents' categories, nursing assistants clinical made up the majority, while nurse practitioners were the least numerous. The average working experience was 4 years (SD ±3). See Table 1 for sociodemographic statistics.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents.

| Sociodemographic | Frequency (N=97) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age Group | ||

| <30 years | 42 | 43.3 |

| ≥30 years | 55 | 56.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 56 | 57.7 |

| Female | 41 | 42.3 |

| Basic qualification | ||

| Certificate | 52 | 53.6 |

| Diploma | 39 | 40.2 |

| 1st Degree | 5 | 5.2 |

| Masters | 1 | 1.0 |

| Highest educational level | ||

| Certificate | 45 | 46.4 |

| Diploma | 35 | 36.1 |

| 1st Degree | 16 | 16.5 |

| Masters | 1 | 1.0 |

| Years of practice | ||

| < 1yr | 10 | 10.3 |

| 1–4 years | 46 | 47.4 |

| ≥5 years | 41 | 42.3 |

| Category of profession | ||

| NP | 2 | 2.1 |

| RN | 36 | 37.1 |

| RM | 11 | 11.3 |

| CHN | 8 | 8.3 |

| NAC | 40 | 41.2 |

| Working unit | ||

| OPD | 17 | 17.5 |

| General Ward | 27 | 27.8 |

| A&E | 14 | 14.4 |

| Theater | 12 | 12.4 |

| ANC | 10 | 10.3 |

| Maternity | 17 | 17.5 |

Source: Field Survey (2022).

Footnote: N = number of participants, % = percentage of participants, NP = Nurse Practitioner, RN = Registered Nurse, RM = Registered Midwife, CHN = Community Health Nurse, NAC = Nursing Assistant Clinical, OPD = Out-Patient Department, A&E = Accident and Emergency, ANC = Antenatal Clinic.

4. Association of nurses’ demographic data and the level of their involvement of children in care

Respondents’ age and gender were significantly associated with the level of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities. Nurses who were ≥30 years old were 8.83 times more likely to involve children in their care activities on a higher level compared to those who were <30 years old (p=0.003). Male nurses were marginally 3.88 times more likely to involve children in their care activities on a higher level compared to their female colleagues (p=0.049). All other variables were not significantly associated with the level of nurses’ involvement of children in their care. Table 2 presents details.

Table 2.

Association between Nurses’ Demographic Data and the Level of their Involvement of Children in Care Activities.

| Variables | Involvement |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poorly Involved n (%) | Highly Involved n (%) | Chi-Square (χ2) | p-value (< 0.05) | |

| Age group | ||||

| <30 years | 31 (73.8) | 11 (26.2) | ||

| ≥30 years | 24 (43.6) | 31 (56.4) | 8.83 | 0.003* |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 27 (48.2) | 29 (51.8) | ||

| Female | 28 (68.3) | 13 (31.7) | 3.88 | 0.049* |

| Basic qualification | ||||

| Certificate | 30 (57.7) | 22 (42.3) | ||

| Diploma | 23 (59.0) | 16 (41.0) | ||

| 1st Degree | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| Masters | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | 1.98 | (0.633) # |

| Highest education level | ||||

| Certificate | 27 (60.0) | 18 (40.0) | ||

| Diploma | 23 (65.7) | 12 (34.3) | ||

| 1st Degree | 5 (31.3) | 11 (68.7) | ||

| Masters | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | 6.89 | (0.055) # |

| Years of practice | ||||

| < 1yr | 7 (70.0) | 3 (30.0) | ||

| 1–4 years | 28 (60.9) | 18 (39.1) | ||

| ≥5 years | 20 (48.8) | 21 (51.2) | 2.09 | (0.367) # |

| Category of profession | ||||

| NAC | 24 (60.0) | 16 (40.0) | ||

| CHN | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | ||

| RN | 18 (50.0) | 18 (50.0) | ||

| RM | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | ||

| NP | 2 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 2.72 | (0.711) # |

| Working unit | ||||

| OPD | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) | ||

| General ward | 17 (63.0) | 10 (37.0) | ||

| A&E unit | 6 (42.9) | 8 (57.1) | ||

| Theater | 8 (66.7) | 4 (33.3) | ||

| ANC | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | ||

| Maternity unit | 9 (52.9) | 8 (47.1) | 2.32 | (0.807) # |

Footnote:.

= Significant p-value.

= Fisher's exact p-value, n = number of participants, % = percentage of participants, NP = Nurse Practitioner, RN = Registered Nurse, RM = Registered Midwife, CHN = Community Health Nurse, NAC = Nursing Assistant Clinical, OPD = Out-Patient Department, A&E = Accident and Emergency, ANC = Antenatal Clinic.

5. Nurses’ involvement of children in care activities

5.1. Involvement in procedures

A significant majority (61.8%) of the nurses did not ask for children's opinions when performing their nursing procedures. In the situations where they did, it was to a lesser extent. Additionally, a substantial proportion of nurses (70.1%) did not prioritize facilitating children's involvement in decisions related to their care. When they did engage in such facilitation, it was to a minor extent. An equal percentage of nurses (70.1%) were found to have excluded children from the majority of nursing procedures they performed on them. In instances where they did include them, it was to a lesser extent. Furthermore, 53.6% of the nurses failed to adhere to children's preferences entirely. In cases where they did accommodate these preferences, it was to a lesser extent. This is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

5.2. Involvement in communication

More than half (55.6%) of the nurses failed to effectively involve children in conversations or discussions concerning their care. Additionally, 55.7% of the nurses frequently ignored children's opinions, and when they did consider them, it was only to a limited extent. Furthermore, a majority (75.2%) of the nurses refrained from involving children in discussions unrelated to their medical condition, and when they did engage them, it was to a limited extent. This is presented in Supplementary Table 2.

5.3. Involvement in information

A significant majority (82.4%) of the nurses were found to have provided information to children to a greater or some extent. Over half of the nurses abstained from seeking input from the children. In situations where they did, it was to a lesser extent. Given the limited information shared with children, 77.3% of the nurses indicated that children understood the disease conditions, treatments, and procedures they underwent during their hospitalization. This is presented in Supplementary Table 3.

5.4. Involvement in nurse-child relationship

About 59% of the nurses had trust in children's competence. Additionally, a significant majority (95.9%) of the nurses indicated that children were treated respectfully. We found that 62.9% of the nurses respected children's rights as they performed their nursing duties. This is presented in Supplementary Table 4.

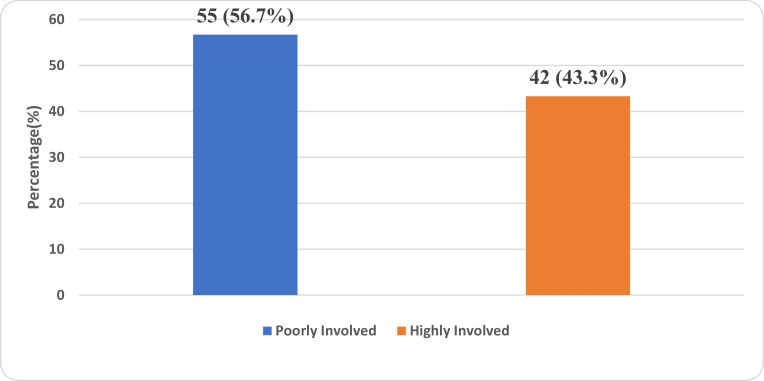

5.5. The overall level of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities

Fig. 1 depicts the overall level of nurses’ involvement of children in their care, determined by respondents scoring half or more [≥7.5 (≥50%)] of the total number of items in Section B of the data collection tool. This was calculated by dividing the sum of “to a great extent” and “to some extent” or the sum of “to a lesser extent” and “not at all,” according to respondents’ responses (numerator) by the total number of items in Section B (15, denominator). The result was then multiplied by 100 to express it as a percentage. Respondents who scored ≥7.5 in nominal terms or ≥50% in percentage terms were classified as “highly involved,” indicating a higher level of nurses’ involvement of children in their care activities. Respondents who scored <7.5 in nominal terms or <50% in percentage terms were classified as “poorly involved,” indicating a poor level of nurses’ involvement of children in their care activities.

Fig. 1.

Level of Nurse’ Involvement of Children in their Care.

In the overall outcome of the nurses’ involvement of children in their care activities, a significant majority (56.7%) of the nurses were classified as “poorly involved” with children in their care activities. On the other hand, 43.3% of the nurses were found to be “highly involved” with children in their care activities. This is shown in Fig. 1.

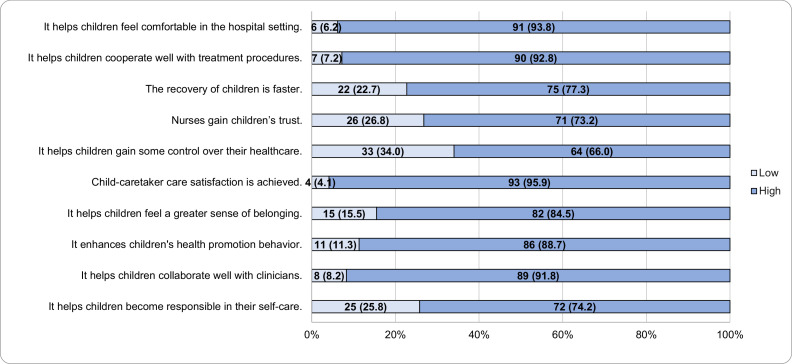

6. Benefits of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities

Fig. 2 depicts ratings of the nurses’ perceived benefits of children's involvement in their care. The perceived benefits were for sick children, parents, caregivers, or nurses. According to the nurses’ ratings, 93.8% indicated that it helped children feel more comfortable in the hospital setting, 92.8% indicated that it improved children's cooperation when undergoing nursing procedures, 95.9% indicated that it enhanced children and caretakers’ care satisfaction level, and 91.8% indicated that it helped children collaborate well with clinicians. For the lowest rating, 66.0% of the nurses indicated that it helped children gain control over their health post-hospitalization. The detailed ratings of the benefits of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Ratings of the Benefits of Nurses’ Involvement of Children in Care Activities

Source: Field Survey (2022).

7. Discussion

This study assessed nurses’ involvement of children in care activities. The study focused on the level of nursing staff involvement of children in care activities, as well as their perceived benefits of the involvement. Nursing staff were the target group, as it is their responsibility to initiate the invitation to children for their involvement and participation in the care process. In pediatric care, all activities within the nursing care process are to be done with the consent of children, parents/caregivers, and all other healthcare team members involved in caring for the sick child. Through this approach, children can play active roles in their nursing care activities. The recent discussions on children's rights to care involvement on both international and national levels have placed much focus on implementing the rights of children's involvement in the existing healthcare systems (Gilljam et al., 2016; Moore and Kirk, 2010). There is a clarion call for healthcare managers and stakeholders to develop policy measures to enhance the implementation of children's rights in care involvement at all levels of the healthcare systems (Davies and Randall, 2015; Larsson et al., 2018). Participation in healthcare activities depends on strong policy measures favorable for patients’ seamless participation (De Freitas, 2017).

We found a significant majority of the nurses had “poorly involved” children in their care activities. This finding is consistent with that of Coyne (2006), who found that most children did not experience nursing care involvement. The children reported, in their own experiences, how they felt neglected in their healthcare. Coyne (2008) also revealed how most doctors failed to support children's participation in their healthcare activities. In her conclusion, Coyne (2008) indicated that the identified gaps in her study on how doctors failed to involve children in their healthcare process could not be explained by educational theory. However, she offered some possible explanations for why doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals fail to involve children in healthcare activities, suggesting that most healthcare professionals feel threatened by empowered children as they lack the professional skills required to manage such children. Building the competence, skills, and confidence of healthcare professionals through continuous professional development and establishing policies and protocols that support the seamless integration of children's involvement and participation in healthcare situations is the solution to overcoming this assertion (Gilljam et al., 2016). With these enhancements, nurses and other healthcare providers will have the requisite knowledge and skills to engage children in procedures, communication, information, and nurse-child relationships during their period of hospitalization.

A significant majority of the nurses failed to seek children's opinions during care. The finding is consistent with a study conducted in Australia on children's nurses (N=6), where nurses admitted to overruling the opinions, preferences, and wishes of children in the performance of their nursing duties, even though children were given the free will to express them (Bricher, 2000). According to Bricher (2000), these acts by the nurses affected the level of children's involvement and participation in nursing care activities. In the overall outcome of our study, a significant majority of the nurses poorly involved children in their care activities; however, a significant majority of them provided information to children as required by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Similarly, the study by Coyne (2006), reported that children often spoke about their need for information on their care. This was to help them understand their illnesses, feel involved in the care, and prepare themselves for treatment and procedures. Their request for information was not always granted by healthcare professionals (Coyne, 2006).

Information provision is an important aspect of preparing children for medical procedures (Jaaniste et al., 2007). After providing information, it is quite important to strive to obtain feedback following the information provided. It is an indicative measure of ascertaining the comprehension and assimilation level of the information given, bearing in mind the age-appropriateness of the a child in question. In our study, more than half of the nurses did not obtain any feedback from children after providing information. Supporting this outcome, some researchers have found that children are often not given information about their medical treatment due to their inability to process and handle difficult medical information (Berrick et al., 2015; Coyne, 2006; Grootens-Wiegers et al., 2017; Rost et al., 2017). Contrary to this, other researchers have established that providing children with information and asking for feedback helps them cooperate well with treatment, feel involved in their care, and feel more comfortable with clinicians and helps them exercise some control over their self-care as they grow (Coyne, 2008; D'Agostino et al., 2017; Denyes et al., 2013; Gutman et al., 2018; Hallström and Elander, 2005; Quaye et al., 2019). Asking for feedback following information delivery is, therefore, critical to making information available to children.

The outcome of the nurse-child relationship during nursing care was generally good, as the nurses had some trust in children. Gilljam and colleagues indicated in their study that children's experience of being surrounded by a sense of security and comfort was an important dimension in promoting their trust in healthcare providers (Gilljam et al., 2016). Another study also indicated that relating cordially with children and treating them with respect promotes their cooperation during care (Sahlberg et al., 2020). For further strengthening the cordial relationship with children, healthcare professionals are tasked with frequent communication with children. This gives them a better understanding of the conversations they have with healthcare professionals. Through frequent communication with children, they become more prepared for medical procedures (Coyne and Kirwan, 2012; Jaaniste et al., 2007).

Hospitalization can be stressful and traumatic for children as well as their parents. It involves traumatizing and stressful experiences because children are moved away from their familiar environments to new settings filled with unfamiliar routines, strange pieces of equipment, and different types of healthcare professionals. Relating well to and frequently communicating with children reduces the stress and trauma they go through during hospitalization (Gilljam et al., 2016). In our study, an average of 83% of the nurses agreed that children's involvement in their care activities yielded positive impacts on children, their parents/caregivers, and the nursing staff. The rated benefits included children feeling comfortable within the hospital environment, children cooperating well with clinicians, faster recovery of children, nurses gaining children's trust, children gaining control over their healthcare, achieving a higher level of child-caretaker care satisfaction, children feeling a sense of belonging, improvement in children's health promotion behavior, and children becoming more responsible for their self-care as they grow. Consistent with the findings of Coyne and Kirwan (2012), Gumidyala et al. (2017), Gutman et al. (2018), Hallström and Elander (2004), and Quaye et al. (2019), nurses gained children's cooperation during nursing care, children expressed themselves freely with less fear, and children obtained a better understanding of their conditions and treatments. Miller (2018), in a study, also demonstrated that, just as in adults, involving children in their healthcare activities led to the improvement of children's health promotion practices. It has already been established that building good relationships with children and constantly communicating with them improves their cooperation level, which, according to Gilljam and colleagues, releases them from the stress and trauma they often experience during hospitalization (Gilljam et al., 2016). These researchers also established that, as children aged, they often gained self-confidence in their health through their active involvement and participation in healthcare activities (D'Agostino et al., 2017; Denyes et al., 2013; Hallström and Elander, 2005). The skill of taking control of their health was enhanced by their frequent involvement and participation in their healthcare processes.

Notwithstanding the benefits of children's involvement in healthcare activities, there remain several hindering factors to children's involvement and participation in matters concerning them. According to Coyne (2008), D'Agostino et al. (2017), Mitchell et al. (2019), Phiri et al. (2019) Runeson et al. (2007), and Sahlberg et al. (2020), the hindering factors within the healthcare system could be categorized into four perspectives: a) laws and regulations – there exist numerous laws and regulations on children's rights to care involvement; however, the implementation is poor; b) the perspective of children – factors such as children's age, maturity level, competence and capacity to understand and process complex medical information can hinder their involvement; c) the perspective of parents/caregivers – the indigenous, traditional, and cultural practices of parents/caregivers often position them as major decision-makers for children, leading to the notion of “children should be seen and not heard”; and d) the perspective of healthcare professionals – barriers include the knowledge level, attitudes, and behavior of health professionals, as well as the ethical dilemma of considering children's age, competence, maturity level, and mental state at the time of care. Consistent with these studies, D’ Agostino et al. (2017), in another study, also presented clear evidence of how culture, poverty, and unemployment impede children's involvement and participation in activities of their concerns.

Surmounting these challenges and supporting children's involvement and participation in healthcare activities is the key to promoting children's self-confidence and health promotion behavior as they transition into adulthood (Miller, 2018). Rekindling the commitment of stakeholders within the healthcare system in mapping out feasible and sustainable interventions to implement children's participatory rights within the healthcare system is the way to realize children's active involvement and participation in healthcare activities. Governance and institutional approaches are therefore required to rethink the meaning of “children's involvement and participation” in decision-making and other activities that influence the lives of today's younger generation (Nolas, 2015). Policy documents to safeguard children's rights in care involvement should be developed by governments and their health agencies, starting from national levels down to hospital levels, to protect and uphold children's rights to healthcare involvement and participation. Commitment to the full implementation of the policies should, therefore, be given the uttermost priority.

8. Limitations

Only one facility and its nursing staff were included in this study. A larger sample size with representation from other health institutions could have yielded different results. The research method used for the study quantified only the trends and attitudes of nurses’ involvement of children in care activities. Using a qualitative research method would have revealed the nurses’ attitudes toward their involvement of children in care activities.

9. Conclusions

We have provided preliminary evidence of the level of nurses’ involvement of children in nursing care activities in a Ghanaian hospital. The overall level of nurses’ involvement of children in daily clinical practice in this study was generally poor. The actions demonstrated by the nurses did not fully fulfill the requirements of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Children's Act of Ghana and other similar policies that give children the right to healthcare involvement and other matters concerning them. A novel revelation was that male nurses were likelier to involve children in their care activities than female nurses. Nurses’ involvement of children in nursing care yielded multiple benefits for children, their parents/caregivers, and healthcare staff. It was noteworthy that although nurses’ involvement was generally poor, their self-reported perceived benefits of involving children were high. Further studies are required to explore why nurses understand the benefits of children's involvement in care but fail to involve them in their nursing practice. The authors, therefore, conclude that policy documents to safeguard children's rights in the healthcare system should be developed and implemented by the government, the Ministry of Health, the Ghana Health Service, and other interested stakeholders, from the national down to the facility level to ensure children's rights, especially their rights to healthcare involvement, are protected.

Funding

No funding to declare.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Richard Kwaku Bawah: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Wahab Osman: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision. Diana Pireh: Formal analysis, Data curation. Millicent Aarah Bapuah: Writing – review & editing. Vida Nyagre Yakong: Writing – review & editing. Millicent Kala: Supervision, Validation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No conflict of interest exists, according to the authors.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the study participants for taking time out of their busy schedules to provide this valuable information. We extend our sincere gratitude to Salina Kikkenborg Berg and Anne Vinggaard Christensen for allowing the authors to use the Patient Participation Questionnaire. Additionally, we would like to thank the hospital managers for their cooperation in facilitating this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijnsa.2023.100160.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Adonteng-kissi O. Child labour versus realising children's right to provision, protection, and participation in Ghana. Aust. Soc. Work. 2021;74(4):464–479. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2020.1742363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aston H.J., Lambert N. Young people's views about their involvement in decision-making. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2010;26(1):41–51. doi: 10.1080/02667360903522777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bach Q., Thomale U., Müller S. Parents’ and children's decision-making and experiences in pediatric epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;107 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström K. Convention on the rights of the child. Int. J. Early Childhood. 1989;21(2):35–44. doi: 10.1007/BF03174582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg S.K., Færch J., Cromhout P.F., Tewes M., Pedersen P.U., Rasmussen T.B., Missel M., Christensen J., Juel K., Christensen A.V. Questionnaire measuring patient participation in health care: scale development and psychometric evaluation. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020;19(7):600–608. doi: 10.1177/1474515120913809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrick J.D., Dickens J., Pösö T., Skivenes M. Children's involvement in care order decision-making: a cross-country analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;49:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricher G. Children in the hospital: issues of power and vulnerability. Pediatr. Nurs. 2000;26(3):277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.E., Guralnick M.J. International human rights to early intervention for infants and young children with disabilities. Tools for global advocacy. Infants Young Child. 2012;25(4):270–285. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0b013e318268fa49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I. Consultation with children in hospital: children, parents’ and nurses’ perspectives. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006;15(1):61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I. Children's participation in consultations and decision-making at health service level: a review of the literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008;45(11):1682–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I., Amory A., Kiernan G., Gibson F. Children's participation in shared decision-making: children, adolescents, parents and healthcare professionals’ perspectives and experiences. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014;18(3):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I., Gallagher P. Participation in communication and decision-making: children and young people's experiences in a hospital setting. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011;20:2334–2343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne I., Kirwan L. Ascertaining children's wishes and feelings about hospital life. J. Child Health Care. 2012;16(3):293–304. doi: 10.1177/1367493512443905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino T.A., Atkinson T.M., Latella L.E., Rogers M., Morrissey D., DeRosa A.P., Parker P.A. Promoting patient participation in healthcare interactions through communication skills training: a systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017;100(7):1247–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A., Randall D. Perception of children's participation in their healthcare: a critical review. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015;38(3):202–221. doi: 10.3109/01460862.2015.1063740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Freitas C. Public and patient participation in health policy, care and research. Porto Biomed. J. 2017;2(2):31–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pbj.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denyes M.J., Orem D.E., Bekel G. Self-Care: a Foundational Science. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2013;14(1):48–54. doi: 10.1177/089431840101400113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilljam B., Arvidsson S., Nygren J.M., Svedberg P. Promoting participation in healthcare situations for children with JIA: a grounded theory study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well Being. 2016;11(1):30518. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.30518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootens-Wiegers P., Hein I.M., van den Broek J.M., de Vries M.C. Medical decision-making in children and adolescents: developmental and neuroscientific aspects. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0869-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumidyala A.P., Plevinsky J.M., Poulopoulos N., Kahn S.A., Walkiewicz D., Greenley R.N. What teens do not know can hurt them: an assessment of disease knowledge in adolescents and young adults with IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017;23(1):89–96. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman T., Hanson C.S., Bernays S., Craig J.C., Sinha A., Dart A., Eddy A.A., Gipson D.S., Bockenhauer D., Yap H.K., Groothoff J., Zappitelli M., Webb N.J.A., Alexander S.I., Goldstein S.L., Furth S., Samuel S., Blydt-Hansen T., Dionne J.…Tong A. Child and parental perspectives on communication and decision making in pediatric CKD: a focus group study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018;72(4):547–559. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallström I., Elander G. Decision-making during hospitalization: parents’ and children's involvement. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004;13(3):367–375. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallström I., Elander G. Decision making in paediatric care: an overview with reference to nursing care. Nurs. Ethics. 2005;12(3):223–238. doi: 10.1191/0969733005ne785oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder M., Söderbäck M., Ranheim A. Health care professionals’ perspective on children's participation in health care situations: encounters in mutuality and alienation. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well Being. 2018;13(1) doi: 10.1080/17482631.2018.1555421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaaniste T., Unit P.M., Hayes B. Providing children with information about forthcoming medical procedures: a review and synthesis. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2007;14(2):124–143. [Google Scholar]

- Koomson, K.N. (2016). The rights of children in Ghana. (2023, April 24). Retrieved from: https://www.grin.com/document/340676.

- Larsson I., Staland-nyman C., Svedberg P., Nygren J.M., Carlsson I. Children and young people's participation in developing interventions in health and well-being: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018;18(1):1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3219-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laura L. Voice” is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br Educ Res J. 2007;33(6):927–942. doi: 10.1080/01411920701657033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller V.A. Optimizing children's involvement in decision making requires moving beyond the concept of ability. Am. J. Bioeth. 2018;18(3):20–22. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2017.1418923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S., Spry J.L., Hill E., Coad J., Dale J., Plunkett A. Parental experiences of end of life care decision-making for children with life-limiting conditions in the paediatric intensive care unit: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore L., Kirk S. A literature review of children's and young people's participation in decisions relating to health care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010;19(15–16):2215–2225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson E., McDonnell T., De Brún A., Barrett M., Bury G., Collins C., Hensey C., McAuliffe E. Factors that influence family and parental preferences and decision making for unscheduled paediatric healthcare-systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020;20(1):1–23. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05527-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolas S. Children's participation, childhood publics and social change: a review. Child. Soc. 2015;29(2):157–167. doi: 10.1111/chso.12108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phiri P., Kafulafula U., Chorwe-Sungani Exploring paediatric nurses’ experiences on application of four core concepts of family centred nursing care in Malawi: findings from a resource limited paediatric setting. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2019;12(1):231–239. https://search.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/exploring-paediatric-nurses-experiences-on/docview/2236689154/se-2?accountid=25704 [Google Scholar]

- Quaye A.A., Coyne I., Söderbäck M., Hallström I.K. Children's active participation in decision-making processes during hospitalisation: an observational study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019;28(23–24):4525–4537. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S., Water T., Dickinson A. Children's perspectives in family-centred hospital care. Contemp. Nurse. 2017;53(4):445–455. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2017.1315829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost M., Wangmo T., Niggli F., Hartmann K., Hengartner H., Ansari M., Brazzola P., Rischewski J., Beck-Popovic M., Kühne T., Elger B.S. Parents’ and physicians’ perceptions of children's participation in decision-making in paediatric oncology: a quantitative study. J. Bioeth. Inq. 2017;14(4):555–565. doi: 10.1007/s11673-017-9813-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runeson I., Mårtenson E., Enskär K. Children's knowledge and degree of participation in decision making when undergoing a clinical diagnostic procedure. Pediatr. Nurs. 2007;33(6):505–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatello M., Janvier A., Verhagen E., Morrison W., Lantos J. Pediatric participation in medical decision making: optimized or personalized? Am. J. Bioeth. 2018;18(3):1–3. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2017.1418931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlberg S., Karlsson K., Darcy L. Children's rights as law in Sweden – every health-care encounter needs to meet the child's needs. Health Expect. 2020;23(4):860–869. doi: 10.1111/hex.13060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkind N. Quantitative research methods. Encycl. Educ. Psychol. 2013;1:833–838. doi: 10.4135/9781412963848.n224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Children's Act, 1998, Act 560. (2023, April 24). Retrieved from: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/56216/101251/F514833765/GHA56216.pdf.

- UN General Assembly Convention on the Rights of the Child. United Nations. Treaty Series. 1989;1577(3):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. (2009). State of the World’s Children: Celebrating 20 Years of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Unicef. Google Scholar. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. (2018a). Conceptual framework for measuring outcomes of adolescent participation. (2023, March, 1-23). Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/media/59006/file.

- UNICEF. (2018b). National human rights institutions (NHRIs) Series: tools to support child-friendly practices. 48. (2023, March, 29). Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/2019-02/NHRI_Participation.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.