Abstract

Background

New graduate nurses are the nursing cohort at greatest risk for turnover and attrition in every context internationally. This has possibly been heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Workplace conditions significantly impact nursing turnover; however, interventions under the positive psychology umbrella may have a mediating impact on the intention to leave. New graduate nurses are generally challenged most in their first three years of clinical practice, and the need for support to transition is widely accepted. Gratitude practice has been reported to improve individual control and resilient response to setbacks and, therefore, is of interest in testing if this intervention can impact turnover intention in the workforce.

Objective

To report on a scoping review undertaken to identify whether ‘gratitude practice’ as an intervention had the potential to improve new graduate nurses’ wellbeing and resilience.

Methods

Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review approach. Primary research papers of any methodology, published in English between January 2010 and July 2022 were included. Literature was sourced from seven databases, including CINAHL PLUS, ERIC, MEDLINE, Professional Development Collection, APA PsychInfo, APA PsychArticles, and Psychological and Behavioural Sciences Collection.

Results

We identified 130 records, of which we selected 35 for inclusion. A large range of interventions were identified; most had some form of writing, journaling, or diarising. The next most common intervention was teaching gratitude strategies via workshops, and many interventions had some form of list or activity trigger for participants to complete. Five studies had complex combined interventions, while the rest were simple, easily reproducible interventions. Interventions were delivered both face-to-face or asynchronously, with some being online only and others sent out as a ‘kit’ for participants to work through.

Conclusion

Our review of existing literature shows a significant gap in research on gratitude practice and its impact on nursing populations. To ensure robust future studies, we suggest defining concepts clearly and selecting outcome measures and tools that are not closely related. Intervention design may not be as important as the choice of measures and tools to measure outcomes.

Keywords: Graduate nurse, Positive psychology, Psychological resilience, Gratitude practice, Wellbeing, Transition to practice, Scoping review

Tweetable abstract: Choice of outcome measures and tools is more important than intervention design for interventional gratitude practice studies.

What is already known about the topic

-

•

Positive psychology interventions, like gratitude interventions, have been shown to improve wellbeing, including outcomes such as improved sleep, greater awareness of personal strengths, and greater subjective wellbeing (increased positive and decreased negative emotions).

-

•

It is unclear whether practicing gratitude can help graduate nurses during their transition to practice, which is a critical time for attrition and turnover, and improve their mental health and resilience.

What this paper adds

-

•

Most interventions had a basis in writing, reflection, and journalling, including responding to a “trigger”, most often designed to focus participants’ attention on what they have to feel grateful for.

-

•

Relationships between gratitude and elements of personal wellbeing were promising in populations and could be transferrable to the graduate nurse population.

-

•

We found that even simple gratitude interventions that were easily reproducible had positive impacts on stress, anxiety, affect, and burnout measures.

-

•

Intervention designs can be face-to-face or delivered asynchronously, be online only, have relatively low cost and little time to implement, and still support positive outcomes.

1. Introduction

Workforce recruitment and retention in nursing has historically been a significant challenge across all health contexts (Cameron et al., 2004; World Health Organization, 2010). In particular, new graduate nurses are among the highest-risk employee groups for turnover, with one study of national American data showing that 43.4 % of nurses had left their jobs in the first three years of practice (Brewer et al., 2012). Findings from a review of international literature reported that in the first three years of clinical practice, 30 %–60 % of all new nurses leave a position or the profession of nursing completely (Goodare, 2017).

Managing the workforce to deliver safe and effective healthcare is challenging (Figueroa et al., 2019), and COVID-19 has contributed to higher risks and increased complexity in care delivery (Burau et al., 2022; Halcomb et al., 2020; Riddell et al., 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic ushered in extreme stress, anxiety, and depression, with subsequent epidemic levels of burnout in the nursing profession. The pandemic highlighted that the management of the health workforce must evolve during prolonged crises (Dinić et al., 2021) and identified a lack of focus on equity and wellness in nurses (Woodward and Willgerodt, 2022). While no one has been immune to trauma, grief, pain, and human suffering during the pandemic, nurses have been increasingly impacted (Nie et al., 2020; Pérez‐Raya et al., 2021; Searby and Burr, 2021), and this has prompted further interest in other ways to improve health and wellbeing, particularly regarding working conditions.

The conditions of a workplace have a significant impact on the outcomes, such as resilience, wellbeing, burnout, stress, and job dissatisfaction, which can lead to turnover of nurses. Factors such as healthcare systems, leadership approaches, professional and patient relationships, staff shortages, and workload, all play a crucial role in this regard (D’Ambra and Andrews, 2014, Halter et al., 2017). However, there is some evidence that if the predictors of burnout are mediated, then intention to leave can be positively impacted (Leiter and Maslach, 2009). Graduate nurses already have significant turnover and leave both their jobs and the profession of nursing; however, we do not yet know the full impact of the pandemic and other burnout factors on graduates transitioning to practice. Some early studies suggested the increased challenges and stressors experienced during the transition to practice place graduates at increased risk of burnout and other mental health impacts (Aukerman et al., 2022; Kovancı and Atlı Özbaş, 2022). We believe the science of positive psychology and research about gratitude practice could explore timely and evidence-based practices to improve health and wellbeing, increase resilience, and support a positive and healthy work environment (Macfarlane, 2020; Rao and Kemper, 2017), thus reducing workforce turnover.

Positive psychology, a formal branch of psychology established in the late 1990s, is concerned with promoting optimal conditions for individuals, groups, and organisations to thrive and flourish (Gable and Haidt, 2005, Wandell, 2016). Gratitude, defined as the appreciation of meaningful elements and experiences in one's life, is a key focus of positive psychology and has been studied as both a trait and a state (Jans-Becken et al., 2020; Sansone and Sansone, 2010). While there is some debate about its nature, gratitude practice (defined as the deliberate implementation of specific tools or interventions to foster gratitude and appreciation) has been shown to have numerous benefits (Boggis et al., 2020; Day et al., 2020). In this scoping review, we were interested in ascertaining whether gratitude interventions could support successful transition of graduate nurses into clinical practice.

Graduate registered nurses in their first year of practice need support to transition effectively and safely into practice (Murray et al., 2020). Finding ways to support graduate nurses is vital, as they report feeling unprepared for the role (Fowler et al., 2018) and hold expectations that do not reflect the experience, while current education programs do little to decrease the reality shock (Bong, 2019; Graf et al., 2020). However, the factors that influence attrition and the retention of new graduate nurses are complex, with interplay among professional identity, the practice environment, and the effect of individual resilience strategies in dealing with stressors (Mills et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2020). Graduate nurse support varies, with factors such as geographical location and clinical environment impacting on the transition experience (Calleja et al., 2019). Since gratitude is linked to stress reduction, increased resilience, and creating prosocial behaviours that improve collaborative relationships (Krejtz et al., 2016), along with reframing negative thinking (Lambert et al., 2012, 2009), we explored whether gratitude interventions could have a positive impact in a nursing cohort.

Positive psychology recognises gratitude as an approach that promotes mental health and not just the absence of mental illness (Bolier et al., 2013). Through the regular systematic cultivation of gratitude, measurable psychological, physical, and interpersonal benefits have been achieved (Macfarlane, 2020). For example, a positive association has been found between gratitude and sleep quality (Wood et al., 2009). However, current findings in gratitude practice research have several limitations. These limitations have been outlined in eight reviews. These include systematic (Boggis et al., 2020; Jans-Becken et al., 2020) meta-analytic (Card, 2019; Cregg and Cheavens, 2020; Davis et al., 2016; Dickens, 2017; Ma et al., 2017; Renshaw and Olinger Steeves, 2016), and meta-narrative (Day et al., 2020) reviews of studies about the impact of gratitude interventions. Impacts of the gratitude interventions on physical factors were most often reported as inconclusive (Boggis et al., 2020; Jans-Becken et al., 2020). These reviews, while serving to describe the current knowledge and robustness of outcomes, did not generally focus on the construction and design of studies, commenting only on design and tools in relation to outcome measures. In addition, these reviews did not include populations with similar work environments as those for our population of interest: new graduates working in a clinical environment.

1.1. Aim

To ascertain whether ‘gratitude practice’, as a positive psychology intervention, had the potential to be an effective vehicle for increasing graduate nurse wellbeing and resilience.

Objectives

-

(1)

To systematically review the available literature on ‘gratitude’, identifying ‘gratitude practices’ and how and with whom they have been applied.

-

(2)

To identify the potential utility of gratitude interventions to support graduate nurse transition.

Research questions

The research questions guiding this review were:

-

1.

What is the available evidence for using gratitude practice/interventions to improve wellbeing in nurses (especially graduate registered nurses) or healthcare workers?

-

2.

What tools most appropriately measure the impact of gratitude interventions on wellbeing and resilience?

-

3.

What are the most common, replicable interventions and study implementation designs that could be useful in healthcare environments?

2. Methods

During this process, our international author team found that it was important to first consider definitions and contextual meanings of gratitude and gratitude interventions, as well as the limitations and challenges surrounding these studies and designs. An initial broad search, therefore, was conducted (not reported) with the intention of enabling the team to gain a shared and agreed understanding of the concepts related to gratitude practice and its position in positive psychology and to gain some insights regarding methodologies that have been applied to implement gratitude practice. Various meta-analysis papers were consulted during this process (Boggis et al., 2020; Card, 2019; Cregg and Cheavens, 2020; Davis et al., 2016; Day et al., 2020; Dickens, 2017; Jans-Becken et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2017; Renshaw and Olinger Steeves, 2016). In that preliminary search, we also applied search terms of ‘new graduate nurs* AND nurs* transition ‘. In undertaking that work, we found few studies had engaged nursing participants. This initial search helped develop our review protocol and search strategy (not registered). We broadened the search terms for the subsequent two searches by including any studies related to gratitude and the general population, as nurses are drawn from all areas of society. This search provided valuable insights into current debates regarding positioning of gratitude within positive psychology. It was a significant process for the team as it helped to inform the research questions, the searches, and later discussion.

We ascribed to Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) view that the scoping review process is not linear but takes an iterative approach, where some steps after reflection are undertaken again by the research team. Our scoping review evolved in this way, with significant discussion needed to help refine our approach to suit the pragmatic purpose and search steps repeated as required as proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (2005).

2.1. Eligibility criteria

All studies that met inclusion criteria were collated electronically in a shared folder that authors from all three countries could access. Inclusion criteria were: papers published between January 2010 and July 2022; in English; of any research methodology; primary research studies; studies about nurses with a focus on graduate nurses (for the second search only). Exclusion criteria included: discussion, editorials or news items; meta-analysis studies; previous literature reviews. The chosen timeframe, from 2010 onwards, marks the beginning of systematic research on gratitude interventions. Prior to this, there was limited content exploring interventions in this area.

2.2. Information sources

Literature searches were conducted on the EBSCO platform using the databases CINAHL PLUS, ERIC, MEDLINE, Professional Development Collection, APA PsychInfo, APA PsychArticles, and Psychological and Behavioural Sciences Collection. Screening of title and abstract focused on identifying publications related to the review objectives. To meet the objectives, literature searches of these cognate areas were conducted separately.

2.3. Search procedures

Selected keywords, below, with application of Boolean connectors and keyword extension as appropriate, were applied to publication Title and Abstract. Extracted sources were saved to RefWorks for detailed analysis.

Search 1 applied the terms gratitude (Title only) AND intervention* AND (Abstract only) stress OR anxiety OR wellbeing. Electronic filters were applied to ensure inclusion criteria for date range and language alignment, and duplicates were removed.

Search 2 applied a specific focus on gratitude interventions and graduate nurses with keywords (gratitude OR gratitude intervention) AND (graduate nurs*). The reference lists of these selected studies and systematic and meta-analysis reviews noted earlier were manually scrutinised for potential inclusion.

Two researchers reviewed the studies using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In cases where they could not agree, the entire research team reviewed the papers until consensus was reached. The research team then conducted a full text review to exclude papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria.

2.4. Data extraction

Included papers were summarised into two tables to describe the paper's context, country of origin, design, intervention, population/study focus, measurement tools and overarching findings (see Tables 1 and 2). All authors discussed the elements identified in the studies, including gaps and commonalities, along with robustness of results. Data were extracted according to reporting fields appropriate to intervention and non-intervention studies (see Tables 1 and 2 for fields and data extracted). In line with our design choice, while studies were not subjected to a formal quality appraisal, we have discussed elements of quality related to study design and rigour where possible and related to our area of interest.

Table 1.

Intervention studies included in review (n = 24).

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ahmed and Masoom (2021) Pakistan |

Quasi Experimental | Gratitude meditation program- three workshops x 1 weekly (half-hour) x 3 weeks Pre- and Post-intervention measures of Subjective Wellbeing |

College students (2 institutions) N = 160 (80 male, 80 female) Age 15-20 years old (69.73 % of participants were 17 to 18 years old) |

· Gratitude Questionnaire-Six Item Form · Positive and Negative Affect Scale · Satisfaction with Life Scale |

Effects on dispositional Gratitude: Increase in dispositional gratitude score. Effects on Subjective Well Being: Increase in satisfaction with life positive effect scores and decrease in negative effect scores |

|

Berger et al. (2019) Israel |

Randomised controlled trial | Participants exposed to one of five 3-week interventions (including a control group) Pre-and post-measures Intervention group 1: Interpersonal gratitude list, Intervention group 2: non-interpersonal gratitude list, Intervention group 3: interpersonal gratitude letter Intervention group 4: interpersonal gratitude list combined with interpersonal gratitude letter Control intervention group: writing daily about one event evoking positive emotion and another negative emotion |

General population: respondents to a Facebook post (n = 138) behavioural science students (n = 72) (Total N= 210), (59 male) Aged 21–36 (M 26.69; SD 3.57), 142 participants completed the study Intervention group 1 n = 40 Intervention group 2 n = 45 Intervention group 3 n = 39 Intervention group 4 n = 45 Control intervention n = 41 |

· Gratitude Simple Appreciation subscale · Gratitude Social Appreciation subscale · General trait gratitude · Patient Health Questionnaire-9 · Positive and Negative Affect Scale Negative subscale. Positive and Negative Affect Scale Positive subscale · Satisfaction With Life Scale |

Interpersonal gratitude interventions led to an increase in interpersonal trait gratitude but not non-interpersonal trait gratitude. Non-interpersonal intervention led to both increase in trait interpersonal gratitude and trait non-interpersonal gratitude |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cheng et al. (2015) Hong Kong |

Double-blind randomised controlled trial | Participants in the gratitude and hassle group wrote work-related gratitude and hassle diaries respectively twice a week for 4 consecutive weeks. A no-diary group served as control. | Health care practitioners (Physicians, nurses, and physical/occupational therapists), N= 102, assigned into 3 conditions: gratitude, hassle, and nil-treatment. | · Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale, Chinese version · Perceived Stress Scale Chinese version. |

Gratitude group showed decline in stress and depressive symptoms over time, but the rate of decline became less pronounced as time progressed. Hassle and control were indistinct from each other. |

|

Deng et al. (2019) China |

Randomised Control Trial | Two experimental groups and one control completed the measures over 5 weeks Experimental group 1: Blessings counting intervention (Daily x 5 weeks) three things or events, grateful for and why Experimental Group 2: Gratitude- sharing intervention (Weekly x 5 weeks)-shared grateful experiences and feelings with counsellor adaptive guidance Control group: Read a short essay concerning technology and summarise it every night |

Male prisoners (violent criminals) N= 96 Age range 21–53 years old |

· The Gratitude, Resentment and Appreciation Test · Chinese version of the Aggression Questionnaire · The Satisfaction with Life Scale to measure cognitive judgment aspect Subjective Wellbeing · The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience to measure affective component of subjective wellbeing |

Across all three outcomes, the two interventions had similar effects and could not be significantly distinguished from each other. Effects of interventions on: Gratitude: had significantly higher scores than the controls, (p = 0.001 & p = 0.001, respectively) Aggression: participants in the gratitude sharing and Blessing-counting groups had lower levels of aggression than the control (p = 0.022 & p = 0.024, respectively Subjective Well Being: participants in the gratitude-sharing and Blessing-counting groups had higher levels of SWB than the control (p = 0.005 & p = 0.003, respectively) |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ducasse et al., 2019) France |

Randomised controlled trial | Intervention- Gratitude journaling 7 days Control group – food diary 7 days |

Psychiatric emergency and acute care inpatients (aged between 18 and 65) who were hospitalised for current suicidal ideation or suicide attempt | At baseline only: · Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview · Beck hopelessness scale · Life orientation Test-Revised · Gratitude scale 6-item Questionnaire Between Pretherapy and Posttherapy · Current psychological pain · Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale · Scale for Suicidal Ideation · Current hopelessness and optimism using numerical rating scales 0-10 · Beck Depression Inventory & State Anxiety Inventory-state questionnaire |

As an add on intervention, positive impact on depression and anxiety levels (not suicidal ideation). Intervention using gratitude journal was well-received. Intervention was considered straightforward and more useful than a food diary |

|

Gabana et al. (2019) United States of America |

Pre- post- intervention | Introduction of a 90 min gratitude workshop Survey in week prior to (Time 1), immediately after (Time 2), and 4 weeks post-intervention. |

University students: sample 27 male wrestlers and 24 female swimmers | · Gratitude Adjective Checklist · Behavioural Symptom Inventory-18 · Satisfaction with Life Scale · Athlete Burnout Questionnaire · Perceived Available Support in Sport Questionnaire |

Post intervention, gratitude significantly increased, distress and burnout significantly decreased and social support increased. |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Jackowska et al. (2016) United Kingdom |

Single Blind Randomised Controlled Trial | 1 intervention and 2 control groups, an active control- everyday events condition, a no treatment control condition) Diary – writing task X 2 weeks (1 week pre- measure questionnaire and physiological assessment and 1 week post measure questionnaires and physiological assessments). Two email prompts through each intervention week Intervention group: express gratitude towards previously unappreciated people/things, for three people/things per day Active Control group: everyday events groups, write about three events/things noticed that day Control no treatment group: No events group- go about their daily lives and advised they would receive task in 3 weeks |

Women (N= 119) either working or studying at a London University gratitude intervention group n = 40 M age in intervention group 26 (range 24.5–27.5) |

· Background demographic questionnaire · Satisfaction with Life Scale evaluative wellbeing · Positive Emotional Style scale - stress and infectious illness (completed every evening in the pre and post intervention weeks) · Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - emotional distress. · Flourishing Scale - Eudemonic wellbeing · Life Orientation Test - optimism · The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index - global sleep disturbance and daily sleep quality ratings (ranging from 0 = ‘Very good’, to 3 =‘Very bad’) over 1 week at baseline and 1 week postintervention · Biological measures: Salivary Cortisol and ambulatory blood pressure and heart rate |

Intervention effects on Subjective Well Being: · Increased positive emotional style was highest in the gratitude and everyday events compared to no treatment group · Reduction in distress was greater in the gratitude group compared to everyday events and no treatment groups · Changes in flourishing did not differ between conditions, but the increase in optimism was greater in the gratitude intervention group Intervention effects on sleep and biological measures · Daily sleep quality was slightly but significantly improved to a greater extent in the gratitude group than in the no treatment group · Greater decrease in ambulatory diastolic blood pressure was recorded in the gratitude than no treatment condition after adjustment for age, Body Mass Index and baseline diastolic blood pressure value |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kerr O'Donovan and Pepping (2015) Australia |

Randomised controlled trial with placebo control group | 2-week diary intervention designed to cultivate gratitude (n = 16; 3 male) and kindness (n = 16; 4 male). Mood monitoring of control group (n = 15; 5 male) provided placebo. Daily self-rating of specified tools and scales | Patients seeking treatment: Adults self-reporting depression, anxiety, relational problems, posttraumatic stress, substance use disorders, and eating disorders and seeking individual psychological treatment. Sample: 48 adults (36 females and 12 males) ranging in age from 19 to 67 years (M = 43 years, SD = 11.1), |

· Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, calculated Hedonic Wellbeing as % Happy days (positive – negative affect). · Evaluation of Eudaimonic Wellbeing using the Purpose in Life test · General well being assessed using Outcome Questionnaire-45.2 and Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale. · Self-rating of Interpersonal Functioning (-3 to +3). |

· Gratitude group rated gratitude, life satisfaction more highly compared to placebo. · No significant difference in kindness ratings but that group demonstrated higher optimism. · No effects on eudaimonic wellbeing. All groups, including placebo, had increased general psychological wellbeing. · All groups showed decreased stress but only gratitude and kindness groups showed decreased anxiety and increased interconnections. |

|

Killen and Macaskill (2015) United Kingdom |

Pre-post intervention, with follow-up | ‘Three good things in life’ gratitude intervention. 2-week intervention, and 30-day follow up Use of gratitude diaries. |

General population of non-clinically depressed older adults. N= 88, aged 60+, M age 70.84, 73.86 % female |

· The Gratitude Questionnaire · The Flourishing Scale · The Satisfaction with Life Scale · The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience · The Perceived Stress Scale · The Center for Disease Control and Prevention Health Related Quality of Life, ‘‘Healthy Days Measure’’ |

· Significant increase in eudemonic wellbeing from baseline to day 15 that was maintained at day 45. · Significant increases hedonic wellbeing evident from baseline to day 45. · Decreases in perceived stress from day 1 to day 15 but these were not maintained once the intervention ended. |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kini et al. (2016) United States of America |

Randomised controlled trial | Variant of the ‘trust game’ called “Pay it forward” task. 3 groups- Randomisation a) Gratitude writing group b) Therapy as usual group (psychotherapy) – control group c) Expressive writing group (were not neurologically scanned) |

Psychotherapy clients seeking clinical counselling (N= 43) (22 in gratitude writing group and 21 in psychotherapy group), 74 % male, evenly distributed for mental health symptoms and for initial gratitude measures, M age 22.9 | Constructed a general linear model for functional neuroimaging data for each participant. This allowed the development of four Parametrically Modulated Regressors: 1. Gratitude rating; 2. Guilt rating; 3. Desire to help rating; 4. Percent of the initial endowment given. These parametrically modulated regressors afforded an estimate of how much each self-reported emotion correlated with activity at the time of decision. |

· Intervention group showed significant increases in both gratefulness and neural sensitivity to gratitude over the course of weeks to months. · Gratitude correlates with activity in specific set of brain regions. |

|

Martin et al. (2019) United Kingdom |

Pre-post study implementation of the “HOPE programme”. | Group, face-to-face intervention of six weekly sessions lasting around 2.5 h. Multi-strategy intervention using strategies such as: · hearing of others’ successful activities · talking about goals · goal setting with reward upon achievement · Individual use of a gratitude diary strategies for managing stress and improving wellbeing, [e.g., managing anger and using breathing techniques] |

Parents/caregivers (N= 108) of children with developmental disorder and who attend the “HOPE Programme”, delivered at Coventry Carers Trust. | · Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale · Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale · Gratitude Questionnaire · Adult State Hope Scale · Health Education Impact Questionnaire |

Participants who completed the intervention had significantly lower anxiety and depression scores, and higher positive mental wellbeing, gratitude, and hope measures. The change in depression and anxiety scores were clinically significant, indicating potential “recovery” from anxiety for 58 % of participants and from depression for 85 %. Outcome measures showed the intervention was relevant and trustworthy for participants. |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Măirean et al. (2019) Romania |

Quantitative: Meta analysis of experiments, surveys, and vignettes | State gratitude was induced through a gratitude exercise on a single day | Undergraduate students (N= 135) in first year of study, 75.60 % female. Participants’ age ranges from 20 to 35 (M age = 21.35 years, SD = 2). | · Gratitude Short From- used to measure dispositional gratitude · Psychological Wellbeing Scale · The Positive and Negative Affect Scale |

Interventions that aimed to improve psychological well-being, using gratitude, showed effectiveness when about everyday experiences, rather than on other people. State gratitude was not identified as a moderation among trait gratitude, affective state, and psychological well-being. No immediate change or improvement in positive feelings across groups. |

|

O'Connell et al. (2017) Ireland |

Double-blind, randomised controlled group study. Pre-post- survey design. Convenience sample plus snowballing. | Reflective interpersonal gratitude journal with two arms and control group. Cohorts included: 1. Reflective-only on instances that they had been grateful for. 2. Reflective-behavioural – as above but also write a letter expressing gratitude. · 3. Control group descriptive of events that had happened. |

General population: N= 192 mostly students (70.8 %) of the host university and non-students (28.6 %), with one person not identifying their student status. 67.2 % female 18-84 years (M age =27.1 years; SD 12.6). |

· Gratitude Questionnaire-Six Item Form · Satisfaction with Life Scale · The Scale of Positive and Negative Experiences · Center for Epidemiological Studies Short Depression Scale |

Significant reduction over time on negative affect scores for both intervention groups. Greatest different in reflective-behavioural group, including reduced depression scores for behavioural group only and increased affect balance over time for this group too. Suggestion of trends reflection-behavioural condition but mostly not significant. Post-hoc (1 month and 3 month) decrease in depression in reflection-behavioural condition only. Expression of gratitude to others is a key factor in improvements in affect. |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ramírez et al. (2014) Spain |

Experimental- Intervention and placebo group. Three points of measurement – pre, post and 4 months post intervention | Intervention program based on an intervention specifically focused on forgiveness, gratitude, and life review therapy. Consisted of nine 1.5 h weekly sessions. 1. Introductions, scales and questionnaires undertaken. 2. Positive psychology 3. Gratitude 8. Forgiveness benefits 9. Conclusion and administer scales and questionnaires. |

Members of the Senior Citizens’ Day Centre in the town of Martos (Jaen, Spain). N= 46 participants aged 60–93 years | · State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spanish version) · Beck Depression Inventory (Spanish version). · Autobiographical Memory Test. · Mini-Cognitive Exam (Mini-Examen Cognoscitivo). · Life Satisfaction Scale (Spanish version) · Subjective Happiness Scale.· |

Participants who followed the program (experimental group) showed a significant decrease in state anxiety and depression as well as an increase in specific memories, life satisfaction and subjective happiness, compared with the placebo group. |

| Rash et al. (2011), Canada | Pre-test post-test intervention, randomised double blinded allocation to groups | 4-week program either in a gratitude contemplation intervention or a memorable events control condition | General population: 56 adults recruited, 47 returned journals and completed the physiological and survey post-test. Unclear numbers in each group | Pre-test measures: · Gratitude Questionnaire-Six Item Form · Positive and Negative Affect Scale · Electrocardiogram recording (physiological measure) during induction to intervention type (gratitude or memorable events) During intervention measures: · Daily Positive and Negative Affect Scale Post intervention measures · Satisfaction with Life Scale · Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

Participants exposed to the gratitude intervention experienced higher levels of self-esteem and life satisfaction. The effect of the gratitude intervention on satisfaction with life was moderated by trait gratitude. |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Otto et al. (2016) United States of America |

Randomised, controlled study of fear of recurrence of cancer. Pre-post- survey design. Post-intervention survey for evaluation, plus 1 month & 4 month follow-up. |

1. Intervention group – 6-week online gratitude – spent 10 min writing a letter expressing their gratitude to a person of their choice. 2. Control group spent 10 min listing and briefly describing up to 20 activities that they had engaged in during the preceding weeks. |

Women with early-stage breast cancer. M age 56.89 years (SD = 10.20). Mainly White (86.6 %) and non-Hispanic (95.5 %). 71.7 % at least a bachelor's degree. Intervention group n = 34, Control n = 33 | · Weekly gratitude average scores (researcher developed tool) · Positive and Negative Affect Schedule · Weekly goal pursuit researcher developed scale. · Fear of recurrence evaluated using researcher developed scale, and Concerns About Recurrence Scale |

Putting more effort into a given letter was a marginally significant predictor of increased gratitude at the following week's survey. Personal affect remained stable in the cancer group but declined in the control. Fear of recurrence remained relatively flat across the study period in both conditions, but the gratitude group experienced a significantly greater decrease in death worry. |

|

Wolfe and Patterson (2017) United States of America |

Experimental – Gratitude intervention (n = 35), vs cognitive restructuring (n = 28) vs control (n = 45) |

Daily workbook task: gratitude list, thought records, (self-report adherence). | Undergraduate female students. N= 140 recruited, after attrition n = 108 completed. M age: 20.44 years (SD 6.93). Ethnicity: 60 % Caucasian, 24 % African/American, 6 % Hispanic or Asian. |

Body Satisfaction: · Body shape Questionnaire · Body Appreciation Scale · Body Esteem Scale Disordered Eating · Eating attitudes test -26 · Binge eating scale Mood · Positive and Negative Affect Schedule · Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Expectation of intervention: · 1 Expectancy item |

Positive outcomes in the gratitude intervention group compared with cognitive restructuring group and control group. Gratitude group identified greater increase in body esteem, sharper decrease in body dissatisfaction, greater decrease in dysfunctional eating. The decrease in depression symptoms decreased more in gratitude group. |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | · Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Osborn et al. (2020) Kenya |

Randomised controlled trial, two arm. One control group (Study skills session) and intervention group | Shamiri digital- An adapted (from in-person, 4-week application delivered universally to high school students) digital self-help single session intervention-Shamiri has three components -wise interventions (growth mindset; gratitude and value affirmation) | High school students (13-18) N= 103 (70 % were female) and covariates were age in years and sex. | · Depressive symptoms: Patient Health Questionnaire – 8 · Anxiety: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener– · Adolescent wellbeing: shortened version of the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale · Happiness and Optimism subscales of the Engagement, Perseverance, Optimism, Connectedness, and Happiness Tool |

Participants in the intervention group experienced larger declines in depressive symptoms from baseline to 2-week (effects greatest in younger adolescents). Significant (improvement) effect for age -younger had improved wellbeing and improved happiness scores from baseline to 2-week follow-up than older adolescents (but no difference in self-reported happiness). Intervention participants who self-reported clinical depressive symptoms at baseline experienced greater reductions in depressive symptoms compared to the control group. |

|

Stegen and Wankier (2018) United States of America |

Pre-test, post-test with multiple gratitude interventions | Gratitude interventions offered over a year pre-planned. Included gratitude moments in faculty meetings, book titled “Attitudes of Gratitude” given to staff, private social media site for gratitude expressions for staff was created, gratitude bulletin board set up in staff room. | Nursing faculty in an American university (N = 51). Women made up 92 % of the group, and experience in teaching ranged 1 year–28 years, median 10 years. | · Adapted from grateful organisations questionnaire from the Greater Good website | Gratitude interventions improved job satisfaction, and positively impacted teamwork and collaboration amongst faculty |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chan (2010) Hong Kong |

Pre-test, post-test after 8-week intervention | Eight week-long self-improvement projects to improve self-awareness through self-reflection. Used a ‘count your blessings’ approach with self-reflection. Participants kept weekly log of three good things that happened, then reflect using Naikan-meditation like questions. |

Chinese schoolteachers enrolled in a graduate education program at a Chinese University. Women made up 79 % of the population. Ages between 23 and 51, with 1-31 years’ experience in teaching. | · Gratitude Questionnaire · Maslach Burnout Inventory · Orientations to Happiness Scale · Satisfaction with Life Scale · Positive and Negative Affect Schedule · Gratitude Adjectives Checklist |

Those with high dispositional gratitude felt life was more meaningful, were happier with their personal accomplishments, and had lower scores for the two components of burnout: emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation. The intervention increased satisfaction with life scores and positive affect, particularly for those teachers with low-gratitude disposition at baseline. |

|

Salces-Cubero et al. (2019) Spain |

Quasi-experimental, Blinded Pre-post-intervention, with 1 month follow-up | 3 intervention and 1 control groups. Intervention groups: 1. Gratitude (n = 36) 2. Optimism (n = 28) 3. Savouring (n = 28) Approximately 4×70 min intervention sessions in each group. Each group led by educator with entertaining approaches to covering content of ‘How to’ Control group (n = 32) had no intervention. Evaluation: pre-week, 1 week after intervention, 1month after intervention. |

Older adults who attend day centres. Total sample = 124. Age 69-89 years | · Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale · Satisfaction With Life Scale · Cognitive Mini-Test (Mini-Examen Cognoscitivo) · Subjective Happiness Scale · Positive and Negative Affect Schedule Resilience Scale |

Gratitude group: No differences were found between the pre- and post- depression. No significant differences were found in the Control group. Significant increase in life satisfaction, including at follow-up. Increased happiness more so at follow-up. Increased resilience but not sustained at follow-up. |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Taylor et al. (2017) United States of America |

Pilot study, intervention, and control group. Pre-, post-treatment outcomes plus follow-up at +3 and +6 months |

Intervention group: 10×1 h sessions of therapist-delivered treatment (Positive Activity Intervention) exercises including gratitude: counting one's blessings; Gratitude: gratitude letter Control: completed pre and post assessments only, were on a waitlist for treatment during intervention time. Were offered treatment after study. |

Patients in active treatment: Adults 18-55 years with anxiety or depression Age 29.8+/-12.2 years Gender 50 % female 75 % Caucasian n = 29 recruited from clinical referrals. |

Positive and negative emotions: · Positive and Negative Affect Schedule · Modified Differential Emotions Scale Psychological wellbeing: · Quality of Life, Enjoyment, and satisfaction Questionnaire –Short Form · Satisfaction with Life Scale Anxiety symptoms: · Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale · State Trait Anxiety Inventory Depressive symptoms: · Patient Health Questionnaire-9 · Becks Depression Inventory Credibility of intervention: · Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire |

Significant improvement to all outcome measures in the Positive Activity Intervention group, including at follow-up, 3- and 6-months points |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | · Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Krejtz et al. (2016) Poland |

Longitudinal experimental design | Gratitude intervention each day was for participants to write down up to six things they were grateful for that day. 2-week daily measures collection via online tools at end of each day. Random allocation to intervention and control group. |

Adult community members of one area of Warsaw, native to Poland. 58 commenced, and 57 continued providing 781 days of valid data. Groups [intervention (n = 29, 65.5 % female, M age = 27.1, SD = 5.76) and control (n = 29, 58.62 % female, M age = 28.81, SD = 5.82)] did not significantly differ in age and gender proportion. 54 % of participants were members of an unmarried couple, 11 % were married, and 35 % were single. Participants were paid approximately $50 United States Dollars. |

· Self-designed and previously reported daily measures of wellbeing and adjustment · Gratitude Questionnaire · Daily affect measured using a circumflex model · Self-esteem measures · Daily depressogenic adjustment measures · Daily worry measures, Complaining measure (self-designed) |

• Intervention group had a reduced response to stressful events •Gratitude did not moderate relationship between daily stress and self-esteem or negative deactive-mood • intervention group reported greater positive active affect (e.g., happy). • when people felt more grateful, their wellbeing was higher •No causal link between gratitude and wellbeing. Was support for a causal link between wellbeing and gratitude •wellbeing was negatively related to stress. |

| Author (s), Date, Country | Design | Intervention(s) | Population | · Measurement Tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yang et al. (2018) China |

Pre-post-intervention, with control group | Kindness intervention: Participants asked to: · perform three acts of kindness every day and diarise · attended weekly group seminars, discuss kindness‐relevant topics. Gratitude intervention: Participants asked to: · everyday recall three events they were grateful and diarise · attend weekly group seminars, discussed gratitude‐related topics. Control participants: attended weekly group seminars, discuss topics of routine correctional education, not related to either kindness or gratitude. |

Prisoners in one Chinese prison, N= 144 Kindness intervention group n = 48 Gratitude intervention group n = 48 Control group n = 48. |

· Affect Balance Scale · Satisfaction with Life Scale · Index of Well‐Being · Subjective vitality scale |

Gratitude intervention: decreased negative affect, increased positive affect, increased life satisfaction score, Increased wellbeing index and had no significant effect on vitality index. |

Notes: n = number, M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, p = Probability Value

Table 2.

Observational studies included in review (n = 11).

| Author (s) and date | Study details and data collection | Focus/population | Measurement tools | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Starkey et al. (2019) United States of America |

Descriptive cross-sectional study. Participants recruited through nursing professional organisation. 12 weeks of weekly surveys. Sample: 146 nurses, 91.1 % female, M age 44 years, 63 % worked full time. |

Focus: How receiving expressions of gratitude predicts physical health outcomes in acute care nurses Population: Nurses |

· Self-developed ‘Gratitude expression and reception’ scale · Life Orientation Test · Quality Care Scale · Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index · Health Event Checklist |

Gratitude predicted sleep quality, sleep adequacy, headaches, and attempts to eat healthily. |

|

Kim et al. (2019) South Korea |

Descriptive cross-sectional study. Data collection – survey, single time point Sample: 360 nurses. Participants recruited from a single tertiary hospital. M age 34.1 years old, 99 % female. |

Focus: To estimate the influence of resilience and gratitude disposition on psychological well‐being in Korean clinical nurses in variety of surgical, medical, and mixed wards Population: Nurses |

· Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test · Dispositional Resilience Scale – 15 · Job Satisfaction Scale · Psychological Wellbeing Scale |

Gratitude disposition had significant direct effect on psychological well‐being. Gratitude disposition had significant indirect effects through the effect on burnout, compassion satisfaction and job satisfaction. |

|

Lau (2017) Hong Kong |

Cross-sectional study. Participants recruited from 9 local non-government organisations who support providers of dementia-related care. Sample: 101 participants completed a face-to-face verbal questionnaire. Data collection on a single time point. M age 57.6 years, 82 % female. Participants were excluded if undergoing cancer treatment or structured counselling programs. |

Focus: Investigate the role of gratitude in the coping process among familial caregivers of People With Dementia. Population: Caregivers |

· Gratitude Adjective scale · Gratitude Questionnaire · Caregiver competence · Social support measures · Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced scale · Caregiver burden- Zarit Burden Interview · Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale |

Gratitude adjective positively related to social support and emotion-focused coping. Gratitude was associated with problem-focused coping as well as emotion-focused coping and associated with greater use of planning. |

|

Lee et al. (2019) United States of America |

Study 1: Experience sampling methodology. Sample: 51 employees, also enrolled as a part time Master of Business Administration student in a large United States of America university over 10 consecutive days. Demographic data collected 1 week before the daily surveys. 49 % were female, 80.4 were Caucasian, and worked an average of 50.6 h per week. Study 2: Critical Incident Technique, single time-point survey to capture two samples both a helper's perspective (sample 1) and receiver (sample 2) of help's perspective. Sample 1: 400 full time employees, 44.9 % female, 85 % Caucasian, 72.1 % aged between 20 and 39 years old Sample 2: 250 full-time employees, 41.3 female, 79.4 % Caucasian, 76.7 % aged between 20 and 39 years. |

Focus: Association of receiving gratitude with prosocial impact and work engagement. Population: Employees in North America |

· Likert scale. | Receipt of gratitude is associated with increases in perceived prosocial impact and work engagement the following day. |

| Author (s) and date | Study details and data collection | Focus/population | Measurement tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Petrocchi and Couyoumdjian (2016) Italy |

Descriptive Cross-sectional study. Data collection – survey, single time point, Sample: 410 participants. Participants recruited from mailing lists of a university and professional organisations and web advertising. M age 33.35 years old, 61.46 % female. |

Focus: To evaluate possible mediation models for the relationship between gratitude and symptoms of depression and anxiety Population: Students, employed, unemployed adults. |

· Gratitude Questionnaire · Forms of Self-Criticizing /attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale · Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale · Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – Trait Form |

Gratitude negatively correlated with self-criticising and self-attacking scales, and positively with the self-reassuring scale. Direct effect of gratitude on anxiety but partially mediated by self-criticising and self-reassuring pathway. |

|

Lin (2015) Taiwan |

Descriptive Cross-sectional study. Data collection – survey, single time point. Sample: 375 participants. Participants recruited from undergraduates studying at 9 universities in Taiwan. M age 20.3 years old, 65 % female. |

Focus: To examine simultaneously the effect of gratitude on social, cognitive, physical, and psychological resources. Population: Undergraduate students |

· Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (Chinese version) · Inventory of coping style · Inventory of social support · Inventory of negative emotions · Inventory of positive emotions · Satisfaction with Life Scale |

Gratitude: · Was significantly associated with social support, emotional-companion support, and informational-tangible support. · Had significant effect on coping style, on problem-focused active coping, on problem-focused passive coping, on emotion-focused passive coping. · In high levels with problem focused active coping and emotion-focused active coping strategies · had a significant positive effect on negative emotions, specifically shame, anger, and on life satisfaction. · In low levels was associated with negative emotions of shame and anger Positive emotion partially mediates the association between gratitude and life satisfaction. |

| Author (s) and date | Study details and data collection | Focus/population | Measurement tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sirois and Wood (2017) United Kingdom |

Longitudinal associations study. Data collection – paired survey, two time points, 6 months apart. Arthritis sample: Timepoint 1 423 participants, M age 44.5 years, 88.1 % female, Timepoint 2. 163 participants, M age 46.9, 91.6 % female. Inflammatory Bowel Disease sample: Timepoint 1: 427 participants, M age 35.6 years, 76.8 % female, Timepoint 2: 144 participants, M age 38.3 years, 77.8 % female. Participants from North America, United Kingdom, and other countries via support groups for arthritis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease, web advertisements, classified advertisements, and support foundation resource pages. |

Focus: To evaluate associations between gratitude and depressive symptoms in chronic illness. Population: Adults with arthritis or Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

· Gratitude questionnaire -6 · Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale · Medical Outcomes Survey 36 item short form · Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales · Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire · Perceived Stress Scale · Duke-University of North Carolina Functional Social Support · Illness Cognition Questionnaire · Psychological thriving scale (based on Carver's 1998 model of psychological thriving) |

Gratitude was associated with lower depressive symptoms |

|

Leppma et al. (2018) United States of America |

Descriptive Cross-sectional study. Data collection – survey, single time point, 7 years after traumatic event. Sample: 113 participants. Participants recruited from one police department in New Orleans. M age 43.2 years old, 23.89 % female. |

Focus: Role of gratitude in Post-traumatic Growth (post-Hurricane Katrina). Population: Police Officers |

· Gratitude Questionnaire-6 · Satisfaction With Life · Recent Stressful Life Changes Questionnaire · Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory · Interpersonal Support Evaluation List |

Gratitude was positively correlated with Post-Traumatic Growth (r = 0.20, p < .05), Satisfaction with life (r = 0.64, p < .001) and Social support (r = 0.69, p < .001) |

| Author (s) and date | Study details and data collection | Focus/population | · Measurement tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Vieselmeyer et al. (2017) United States of America |

Descriptive Cross-sectional study. Data collection – survey, single time point, 4 months after a traumatic event. Sample: 359 participants, recruited from staff and students at a university where an on-campus shooting occurred. M age 27.26 years old, 75 % female, 66 % were undergraduate, 5 % postgraduate, 11 % faculty and 17 % staff members. |

Focus: To investigate relationship between trauma and mental health outcomes following university campus shooting. Population: University students and staff |

· Gratitude Questionnaire-6 · The Brief Trauma Questionnaire · Trauma exposure measures · Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – Civilian · Posttraumatic Growth Inventory · Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale- 25 |

Gratitude moderated effect of post-traumatic stress on post-trauma growth. High gratitude associated with high levels of post-trauma growth |

|

McCanlies et al. (2014) United States of America |

Descriptive Cross-sectional study. Data collection – survey, single time point, 7 years after traumatic event. Sample: 114 participants. Participants recruited from one police department in New Orleans. M age 43.0 years old, 26.3 % female. |

Focus: To evaluate if higher levels of resilience, gratitude, life satisfaction, and posttraumatic growth were associated with lower Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder symptoms among law enforcement officers Population: Police Officers |

· Gratitude Questionnaire · Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory · Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – Civilian version · Connor-Davidson resilience scale · Satisfaction With Life Scale |

Gratitude may be protective or mitigate symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Expressing gratitude or having a grateful disposition is positively associated with increased life satisfaction, hope, and happiness |

| Author (s) and date | Study details and data collection | Focus/population | Measurement tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Jans-Beken et al. (2018) Netherlands |

Four-wave prospective survey design. Data collection – survey, four time points, at Time 0, 6, 18, and 30 weeks from Time 0. Sample: 706 participants commenced, 280 completed. Adult participants recruited from the public in multiple advertisements. From completions, M age 48 years old, 71 % female. |

Focus: To evaluate if a grateful trait influences psychopathology and subjective wellbeing. Population: Adults (general population) |

· Dutch Short Gratitude, Resentment, and Appreciation Test · Dutch version of Symptom Check List -90 · Satisfaction With Life Scale · Positive and Negative Affect Scale |

The grateful trait did not predict symptoms of psychopathology. Gratitude predicted subjective wellbeing. |

Note: n = number, M= Mean, SD = Standard Deviation, p = Probability Value, r = correlation coefficient.

3. Results

Findings are described according to design fields according to interventional or non-interventional design, identified in the Methods.

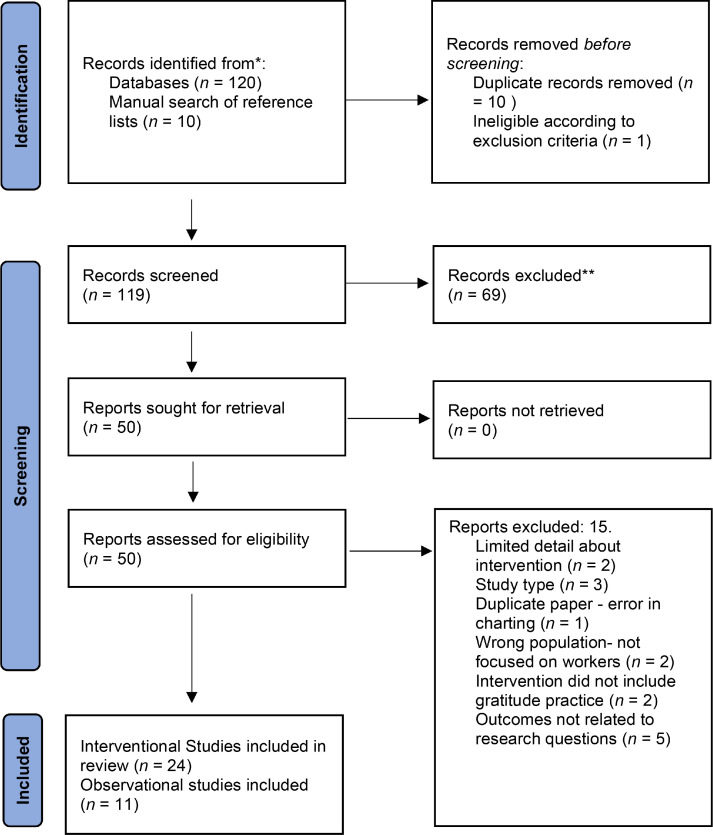

Searches 1 and 2 were run separately. Search 1 yielded 130 studies, and nil results were obtained from Search 2; this is represented in one figure (see Fig. 1 for results through the search and screening phases). After inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, 34 studies were selected for inclusion in the review, which comprised 24 interventional studies (Table 1) and 11 observational studies (Table 2). Tables 1 and 2 outline the included studies’ characteristics, including authors, year of publication, study origin, design, population, interventions or measurement tools used, and outcomes.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

n = number.

3.1. Country of study

The database identified a global focus for this subject. Overall, studies were conducted in European locations, North America, Asia, Africa, and Australia (see Tables 1 and 2). This is relevant to our review, as it demonstrates global interest in these type of positive psychology interventions, even while this review was limited to studies published in English.

3.2. Population and samples

As noted earlier, our literature search was not limited to studies that had engaged specifically with newly-graduated nurses. It is also the case, however, that nurses come from a range of backgrounds. On that basis the populations were broadened, and studies were included from police officers, prisoners, caregivers, the general population, employees, university students/staff, unwell adults, and teachers. The search did identify two studies that engaged experienced nursing staff or health workers. One was an intervention study, the nurses were not in a clinical setting (Kim et al., 2019), but rather in an academic setting as teaching faculty. The other study (Măirean et al., 2019) was conducted in a clinical setting but unfortunately did not differentiate participant data from that of physicians, nurses, and physical or occupational therapists.

3.2.1. Study designs

Of the 24 interventional studies, we categorised 10 as randomised controlled trials, based on author description. Nine were categorised as ‘pre-post’ studies, and five were categorised as ‘other studies’; e.g., quasi-experimental, longitudinal design, and others (see Table 1). Eleven further studies were categorised as observational, mostly concerned with evaluation of statistical associations between psychological factors and gratitude (see Table 2).

Interventional studies (Table 1) identified a range of interventions and designs, with variable timing of the interventions, some being once per week for 2 to 4 weeks (Ahmed and Masoom, 2021; Berger et al., 2019), others on a weekly basis of up to 10 weeks (for example, Taylor et al., 2017), and others less intensive but delivered over a year (for example, Stegen and Wankier 2018). Interventions were broadly-collated across different approaches as: diarising/journalling elements (Berger et al., 2019; Chan, 2010; Cheng et al., 2015; Ducasse et al., 2019; Jackowska et al., 2016; Kerr et al., 2015; Killen and Macaskill, 2015; Kini et al., 2016; Krejtz et al., 2016; Măirean et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2019; O'Connell et al., 2017; Wolfe and Patterson, 2017); facilitated face-to-face or workshop style interventions delivered as individual or group sessions (Gabana et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2019; Ramírez et al., 2014; Salces-Cubero et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018); gratitude exercises, such as blessings counting, gratitude letters, gratitude lists, and gratitude sharing or expression (Berger et al., 2019; Chan, 2010; Deng et al., 2019; Jackowska et al., 2016; Killen and Macaskill, 2015; Kini et al., 2016; Krejtz et al., 2016; Măirean et al., 2019; Otto et al., 2016; Rash et al., 2011; Stegen and Wankier, 2018; Taylor et al., 2017; Wolfe and Patterson, 2017; Yang et al., 2018); a gratitude meditation or contemplation programme (Ahmed and Masoom, 2021); and finally, a number of combined or complex interventions (Berger et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2019; Osborn et al., 2020; Ramírez et al., 2014; Stegen and Wankier, 2018).

Most observational studies (Table 2) were concerned with exploring relationships between gratitude and aspects of subjective, psychological wellbeing: resilience, job satisfaction, and broader psychological wellbeing (Jans-Beken et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2019; Leppma et al., 2018; Lin, 2015; McCanlies et al., 2014); coping (Lau and Cheng, 2017; Lin, 2015); emotions; such as depression and anxiety (Petrocchi and Couyoumdjian, 2016; Sirois and Wood, 2017); or post-traumatic growth (Leppma et al., 2018; Vieselmeyer et al., 2017). Some studies sought relationships that gratitude had with physical wellbeing factors that included sleep quality (Starkey et al., 2019), a range of medical outcomes with regards to chronic illness (arthritis or irritable bowel syndrome) (Sirois and Wood, 2017), and psychopathology symptoms (Jans-Beken et al., 2018). One study evaluated prosocial impact and work engagement (Lee et al., 2019), and others included social support measures as well (Leppma et al., 2018; Sirois and Wood, 2017).

3.2.2. Tools that measure impact of interventions

The measurement tools used almost entirely comprised self-report measures of gratitude and subjective psychological, social, or physical parameters. In observational studies reviewed, inferential statistics were used to assess relationships between gratitude scores and emotional state, depression or anxiety, broader psychological state measures, life satisfaction, resilience, burnout and coping measures, and stress or other health and wellbeing measures (see Table 3). Table 3 provides a summary of tools used to measure impact of gratitude interventions.

Table 3.

Summary of tools used to measure impact of gratitude interventions.

| Tools/measures related to | Tool/measure | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Gratitude | Gratitude Questionnaire-6 Item Form (or translated version) |

Ahmed and Masoom (2021) Chan (2010) Ducasse et al. (2019) Killen and Macaskill (2015) Krejtz et al. (2016) Leppma et al. (2018) Lin (2015) Martin et al. (2019) McCanlies et al. (2014), O'Connell et al. (2017), Petrocchi and Couyoumdjian (2016), Rash et al. (2011), Sirois and Wood (2017), Vieselmeyer et al. (2017) |

| Gratitude Adjective Checklist |

Gabana et al. (2019) Chan (2010) |

|

| Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test, Simple Appreciation subscale | Berger et al. (2019) | |

| Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test, Social Appreciation subscale | Berger et al. (2019) | |

| General trait gratitude | Berger et al. (2019) | |

| The Gratitude, Resentment and Appreciation Test |

Deng et al. (2019) Jans-Beken et al. (2018) |

|

| Tools adapted from Grateful Organisations Questionnaire (the Greater Good website Berkely university) | Stegen and Wankier (2018) | |

| Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test (Short Form used to measure dispositional gratitude) | Măirean et al. (2019) | |

| Self-developed gratitude scores/checklists |

Otto et al. (2016) Starkey et al. (2019) |

|

| Emotional state | Positive and Negative Affect Scale (or translated version) |

Ahmed and Masoom (2021) Berger et al. (2019) Jans-Becken et al. (2020) Kerr et al. (2015) Măirean et al. (2019) Otto et al. (2016) Salces-Cubero et al. (2019) Rash et al. (2011) Chan (2010) Taylor et al. (2017) Wolfe and Patterson (2017) |

| The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience |

Deng et al. (2019) Killen and Macaskill (2015) O'Connell et al. (2017) |

|

| Life orientation Test (or revised version of this test) |

Ducasse et al. (2019) Jackowska et al. (2016) Starkey et al. (2019) |

|

| Subjective Happiness Scale |

Ramírez et al. (2014) Salces-Cubero et al. (2019) |

|

| Positive Emotional Style scale | Jackowska et al. (2016) | |

| Daily affect measured using a circumflex model | Krejtz et al. (2016) | |

| Adult State Hope Scale | Martin et al. (2019) | |

| Engagement, Perseverance, Optimism, Connectedness, and Happiness | Osborn et al. (2020) | |

| Affect Balance Scale | Yang et al. (2018) | |

| Modified Differential Emotions Scale | Taylor et al. (2017) | |

| Inventory of positive emotions | Lin (2015) | |

| Inventory of negative emotions | Lin (2015) | |

| Orientations to Happiness Scale | Chan (2010) | |

| Depression or anxiety | Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale |

Cheng et al. (2015) Lau (2017) O'Connell et al. (2017) Petrocchi and Couyoumdjian (2016) Sirois and Wood (2017) Wolfe and Patterson (2017) |

| Beck Depression Inventory |

Ducasse et al. (2019) Ramírez et al. (2014) Taylor et al. (2017) |

|

| State and Trait Anxiety Inventory |

Petrocchi and Couyoumdjian (2016) Ramírez et al. (2014) Taylor et al. (2017) |

|

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

Jackowska et al. (2016) Martin et al. (2019) |

|

| State Anxiety Inventory-state questionnaire | Ducasse et al. (2019) | |

| Beck hopelessness scale | Ducasse et al. (2019) | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener–7 | Osborn et al. (2020) | |

| Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale | Kerr et al. (2015) | |

| Daily depressogenic adjustment measures | Krejtz et al. (2016) | |

| Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale | Salces-Cubero et al. (2019) | |

| Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale | Taylor et al. (2017) | |

| Psychological state | Mini-Cognitive Exam |

Ramírez et al. (2014) Salces-Cubero et al. (2019) |

| Behavioral Symptom Inventory-1 | Gabana et al. (2019) | |

| Psychological Wellbeing Scale (or translated version) |

Măirean et al. (2019) Kim et al. (2019) |

|

| Symptom Check List 90 | Jans-Beken et al. (2018) | |

| Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview | Ducasse et al. (2019) | |

| Quality of Life, Enjoyment, and satisfaction Questionnaire –Short Form | Taylor et al. (2017) | |

| Life Satisfaction | Satisfaction with Life Scale |

Ahmed and Masoom (2021) Berger et al. (2019) Chan (2010) Deng et al. (2019) Gabana et al. (2019) Jackowska et al. (2016) Jans-Beken et al. (2018) Killen and Macaskill (2015) Leppma et al. (2018) Lin (2015) McCanlies et al. (2014) O'Connell et al. (2017) Rash et al. (2011) Salces-Cubero et al. (2019) Taylor et al. (2017) Yang et al. (2018) |

| Job Satisfaction Scale | Kim et al. (2019) | |

| Life Satisfaction Scale | Ramírez et al. (2014) | |

| Resilience, burnout, or coping | Connor-Davidson resilience scale |

McCanlies et al. (2014) Vieselmeyer et al. (2017) |

| Resilience Scale | Salces-Cubero et al. (2019) | |

| Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced | Lau (2017) | |

| Maslach Burnout Inventory | Chan (2010) | |

| Forms of Self-Criticizing /attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale | Petrocchi and Couyoumdjian (2016) | |

| Inventory of Coping Style | Lin (2015) | |

| Stress | Perceived Stress Scale | Cheng et al. (2015), Killen and Macaskill (2015), Sirois and Wood (2017) |

| Daily worry measures | Krejtz et al. (2016) | |

| Recent Stressful Life Changes Questionnaire | Leppma et al. (2018) | |

| Other health or wellbeing | Patient Health Questionnaire | Berger et al. (2019), Osborn et al. (2020), Taylor et al. (2017) |

| Flourishing Scale | Jackowska et al., 2016, Killen and Macaskill (2015) | |

| The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | Jackowska et al. (2016), Starkey et al. (2019) | |

| Evaluation of Eudaimonic Wellbeing using the Purpose in Life test | Kerr et al. (2015) | |

| General well being assessed using Outcome Questionnaire-45.2 | Kerr et al. (2015) | |

| The Center for Disease Control and Prevention Health Related Quality of Life | Killen and Macaskill (2015) | |

| Professional Quality of Life | Kim et al. (2019) | |

| Health Related Quality of Life -14 ‘‘Healthy Days Measure” | Killen and Macaskill (2015) | |

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | Rash et al. (2011) | |

| Self-esteem measures | Krejtz et al. (2016) | |

| Self-designed and previously reported daily measures of wellbeing and adjustment | Krejtz et al. (2016) | |

| Psychological thriving scale (based on Carver's 1998 model of psychological thriving) | Sirois and Wood (2017) | |

| Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale | Martin et al. (2019) | |

| Adolescent wellbeing; Shortened version of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale | Osborn et al. (2020) | |

| Health Event Checklist | Starkey et al. (2019) | |

| Medical Outcomes Survey 36 item short form | Sirois and Wood (2017) | |

| Index of Well‐Being | Yang et al. (2018) | |

| Subjective vitality scale | Yang et al. (2018) |

Across studies, gratitude as a construct was measured (Table 3) mostly by applying the Gratitude Questionnaire; the Gratitude, Resentment, and Appreciation Test; its shorter version; or the Gratitude Adjective Checklist. Of these, the Gratitude Questionnaire was most widely applied, even though all four tools report excellent internal reliability with Cronbach's alpha values in excess of 0.70 (Card, 2019). Researchers who used these tools reported contextual relevance across cultural divides, as tools were tested for validity and sensitivity in different populations and cultural groups. Some tools were translated into several languages and so may extend the availability of a measuring tool. Despite this, our review identified five other, largely self-developed, tools that were used to measure gratitude, with no clear explanation for this choice. Table 3 also collates the other tools applied, some of which were validated and highly regarded, but others were less well known. Tables 1 and 2 identify application of 60 measures of health, wellbeing, or social factors. Although the variation in measures can be attributed to the focus of the study, such as depression, life satisfaction, and sleep quality, there seemed to be a lack of consistency in grouping them together, with little discussion of the rationale behind these groupings.

4. Outcomes

4.1. Summary of evidence

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggested that gratitude interventions may have a beneficial impact, particularly related to psychological wellbeing (Boggis et al., 2020; Cregg and Cheavens, 2020; Davis et al., 2016; Dickens, 2017; Jans-Becken et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2017). However, those studies demonstrated considerable variability in effect sizes and heterogeneity of study designs. The present review examined how gratitude interventions have been delivered to identify a design that appears most appropriate to engage with graduate nurses transitioning to practice. We found few studies that involved nurses as participants. This meant we were working only with studies that had the potential to have translatable findings, as opposed to firm evidence within our population of interest. However, as nurses are well-represented from many cultural, socioeconomic age, and previous working backgrounds, we have embraced the population diversity in which gratitude interventions were implemented in this review.

4.2. Outcomes: overarching findings

Unsurprisingly, our analysis of the 24 interventional studies supported findings from recent systematic reviews that gratitude interventions can have positive impacts on many wellbeing factors (Table 1). One group of researchers (Salces-Cubero et al., 2019) identified increased self-reported resilience scores post- intervention. Other findings included improved scores on quality of life or life satisfaction (Ahmed and Masoom, 2021; Chan, 2010; Kerr et al., 2015; Ramírez et al., 2014; Rash et al., 2011; Salces-Cubero et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018). Similarly, the findings in the 11 observational studies (Table 2) further supports the idea that gratitude has a significant role in reducing anxiety, burnout, and negative emotions, while also positively impacting personal factors such as life satisfaction and social support.

Positive outcomes, therefore, included a breadth of variables particularly related to psychological wellbeing or social behaviours, as well as clinical issues, such as depression. In systematic/meta-analytical reviews, the analysis of effect sizes identified the impact of interventions as being variable, mostly weak, or modest. One factor in evaluating that variability was that outcome variances in those reviews tended to be high. However, although removal of outlier data from analyses reduced the effect sizes, they did not alter the statistical significance of the outcomes (Cregg and Cheavens, 2020). Follow-up evaluations of up to 10-12 weeks after one gratitude intervention provided evidence of some sustained improvements, especially increased happiness and wellbeing (Davis et al., 2016) and reduced depression (Cregg and Cheavens, 2020; Jans-Becken et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2017). These latter findings were encouraging for the focus of our review and suggested a sustained effect of gratitude, which is important when considering intervention effect and how long those effects may endure.

Methodological weaknesses may affect the results of individual studies. We reviewed various study designs, including randomised controlled interventions and less rigorous designs. Some outcomes reported were not significant or even negative for certain factors. For example, some studies did not observe increased positive emotions despite strong support for it (Măirean et al., 2019). Similarly, not all studies reported a reduction in depressive symptoms (Salces-Cubero et al., 2019).

Gratitude practice was not always a stand-alone intervention but was applied within a suite of supports or part of a more complex intervention (Martin et al., 2019; Osborn et al., 2020; Ramírez et al., 2014). Alternatively, some studies utilised different intervention arms, in which the effects of gratitude were applied in different formats (see for example, Berger et al. 2019, Deng et al. 2019, O'Connell et al. 2017). To be included in our scoping review, data specifically related to gratitude intervention had to be available. The selected studies lacked consensus on gratitude intervention tools and measures. Journalling/diarising was prominent but appeared in only seven studies. Face-to-face workshops and other interventions were also used. There is no clear evidence to determine the most effective intervention. The tentative indication of positive outcomes in most studies suggests convenience for participants should be the primary concern when selecting an intervention.

5. Discussion

We conducted this scoping review to ascertain whether a gratitude intervention could potentially promote graduate nurse wellbeing and resilience. To achieve this, we sought evidence for the application of gratitude practices and their potential utility to support graduate nurse transition. Nurses were not prominent from our search, and they appeared to be a largely under-researched group. Issues of stress and burnout in nursing are well recognised, but they are not easy to rectify as their effects often arise from system-level adversities (e.g., political decisions, under-resourcing, poor management, dysfunctional and insecure organisations, disempowered nurse managers, sexism and racism), as well as emotional and relational issues (e.g., supporting the distress and suffering of the patients they care for) (Traynor, 2018). The widespread positive effects of gratitude on various psychosocial factors suggest that having a disposition of gratefulness can be an advantageous inner resource for people of all backgrounds and populations (Ahmed and Masoom, 2021; Chan, 2010; Kim et al., 2019; Măirean et al., 2019). Although not specific to nurses, the idea that promoting gratitude might decrease stress-related, negative health impacts and buffer the negative effects of burnout (Lin, 2015) is promising.

Systematic/meta-analytic reviews highlighted potential moderators of responses to gratitude that might confound study outcomes. Outcomes from interventional designs are sensitive to risk of bias arising from inadequate ‘blinding’ of participants to the intervention or control condition to which they have been allocated (Boggis et al., 2020), and this may explain the variety of designs used in the selected studies. Almost half of the studies were randomised and controlled, but even those may not have ensured that participants remained unaware, as allocation to the intervention or comparator group could be readily ascertained.