Abstract

Background

International nurses (migrant nurses who are recruited to work in different countries) make essential contributions to global health and care workforces that are experiencing domestic nurse shortages. Global recruitment and migration is increasing, and with growing dependency on international nurses, health and care employers must understand their lived experiences if they want to support acculturation and subsequent retention.

Aim

This paper reports a systematic review of qualitative literature on the experiences of international nurses working overseas. The aim is to explore the lived experiences of international nurses working and living in different countries globally. We argue their experiences shape socialisation and contribute to longer term retention of this fundamental nursing workforce.

Method

A systematic literature search was carried out in Medline, CINAHL, PsychInfo, PubMed and Web of Science for global research publications from 2010 to 2020. Research studies conducted in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States were identified, quality appraised and subjected to data extraction/analysis.

Findings

The findings of twenty seven papers were synthesised into six themes: (1) individual and organisational preparedness, (2) communication and the art of language, (3) principles and practices of nursing, (4) social and cultural reality, (5) equality, diversity and inclusion, and (6) facilitators of integration and adaptation.

Discussion

Whilst experiences are multifaceted and complex, factors shaping acculturation of international nurses were transferable across various countries. Individual motivations for migration should be recognised, and short term, transitional and long term needs must be identified to support development needs and ongoing career progression. Cultural integration and language barriers should be sensitively managed to enable effective acculturation. Culturally sensitive leadership is also key to ensuring zero tolerance of inappropriate racist and discriminatory behaviours.

Conclusion

Health and care employers offer tangible benefits for international nurse workforces and in culturally compassionate and professional sociocultural environments, international nurses can thrive. However, to effectively retain this workforce in the longer term, significant improvement is required across a number of areas.

Tweetable abstract

This new systematic review paper explores the factors that can support acculturation and retention of internationally-recruited nurses globally.

Keywords: International nurses, Migrant nurses, Retention, Systematic review, Workforce planning, Overseas nurses, Foreign nurses

Highlights

-

•

Nursing workforce shortages are an issue of international concern, with the gap between demand for services and limited supply of nurses widening.

-

•

Countries impacted by nursing shortages have recruited internationally to fill vacancies, with many countries now dependent on international nurses to meet domestic shortages.

-

•

Despite the success of overseas recruitment drives in attracting international nurses, there has been limited attention to the supporting acculturation and the longer term retention of an important nursing workforce.

-

•

International nurses can experience challenges and frustrations alongside unique learning needs that makes their transitional period difficult.

-

•

Through examining the lived experiences of international nurses, we identify factors that shape acculturation and may support retention of this key workforce.

-

•

To support retention of international nurses, health care providers must increase support and development opportunities to meet their expectations and aspirations.

1. Introduction

International migration was estimated to involve around 272 million people in 2019, a rise of 51 million people since 2010 (United Nations, 2020). In the ‘age of migration’ (de Haas, Castles and Miller, 2019), a significant amount of human mobility involves health workers (Bludau, 2021), including internationally-recruited nurses from predominately low and middle-income countries to high-income countries with developed health care systems (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017). The Philippines has been the world's primary sender of internationally-recruited nurses for several decades, whilst India, and the southern state of Kerala, is recognised as a growing supplier (Thompson and Walton-Roberts, 2019). Whilst shortages of nurses are acute in the African, South-East Asia and Eastern Mediterranean regions (World Health Organisation, 2020a), the situation is also significant in developed countries, where recent estimates suggested nine million nurse and midwifery positions remained vacant (World Health Organisation, 2020a; World Health Organisation, 2020b), Within this context, developed countries have turned to international recruitment to fill nursing vacancies. In 2015, 26 percent of nurses in New Zealand were qualified overseas (an increase from 14.7 percent in 2002) (Nursing Council of New Zealand, 2015), and in Australia (although perhaps not precise terminology) around 18 percent of nurses were registered as ‘foreign-born’ in 2017 (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017). In 2019, nurses trained overseas amounted to around 18 percent of the total nursing workforce in the United Kingdom (Office for National Statistics, 2019), whilst in Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, international nurses reached as high as 79 percent of the total nursing workforce in 2008 (Aspen Institute, 2008).

Globalisation and demand for nurses in developed countries has created a situation in which registered nurses have greater choice over where to work, and whether to apply internationally. The desire of nurses to work overseas has been supported by large-scale international recruitment drives of developed countries and networks of intermediaries including recruitment agencies (Hussein et al., 2013; Kingma, 2018). However, whilst overseas recruitment can be considered successful in the short term by attracting large numbers of international nurses to fill positions (Buchan et al., 2005; Philip et al., 2019 Roth et al., 2021), there is the evolving significant issue of retention. For example, in the United Kingdom, 23,243 international recruits were recorded as leaving the Nursing and Midwifery Council register between April 2014 and March 2019, a sizeable figure considering 39,164 international recruits joined the register during the same period (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2019). This suggests whilst developed countries have turned to international recruitment, an overemphasis on recruitment has excluded from view factors that can support successful acculturation and retention of international nurses for longer periods of time.

There is evidence exploring the motivations and lived experiences of international nurses recruited to work in different countries (Walani, 2015; Thompson and Walton-Roberts, 2019; Gerchow et al., 2021). Some reviews have enabled understanding of the experiences of international nurses working across a range of countries, and within specific countries (Nichols and Campbell, 2010; Davda et al., 2018; Bond et al., 2020; Abuliezi et al., 2021). However, as far as we are aware, no systematic review has explored the experiences of international nurses working within different countries with a focus on understanding factors that support international nurses’ desires to stay in overseas positions. This is important for two reasons. First, as noted, developed countries have grown increasingly dependent on international recruitment of nurses, a dependency strengthened by the acceleration of international recruitment to manage service pressures during COVID-19 pandemic (Buchan et al., 2022). This includes countries that have not traditionally been active in international recruitment (Buchan et al., 2022), suggesting intensified competition between countries and therefore highlighting the urgency of enculturating and retaining this workforce. Second, the reputation of countries’ health care systems may be damaged if there is a revolving door of international nurses, a possibility foregrounded by a failure to understand factors that facilitate nurses to stay and embed into societies of host countries. Given the growing dependency of countries on international nurse, intensified competition between countries and the potential for reputational damage caused by high turnover, our systematic review exploring this topic is pertinent.

2. Aim of the study

Acknowledging the importance of acculturation and retention of international nurses, the aim of the review is to explore the lived experiences of international nurses working and living in different countries globally to examine how these factors have potential to inform acculturation and longer term retention. We define international nurses as individuals who are educated and registered in nursing prior to being recruited to work in a different country.

Whilst ‘nurse retention’ has been critiqued for being ambiguous and poorly defined as an end state transactional impact (Buchan et al., 2018; Efendi et al., 2019), we have deployed the concept of acculturation for examination. Acculturation is defined as the process by which an individual begins to settle in a new culture and learns about its practices and values (Alamilla et al., 2017), something recognised as a crucial prerequisite for successful long-term integration (Politi et al., 2021). We therefore view this as a useful bridging concept between international nurses’ experiences of working overseas and ‘retention’, which we conceptualise as an individual's decision to stay or leave their overseas employment position.

3. Method

A systematic review of qualitative studies was conducted in February 2021. Data were collected from five databases (Medline, CINAHL, PsycInfo, PubMed and Web of Science). International primary research studies using a qualitative design published in 2010 to 2020. Search terms and limitations were determined and selected with the aid of a subject librarian.

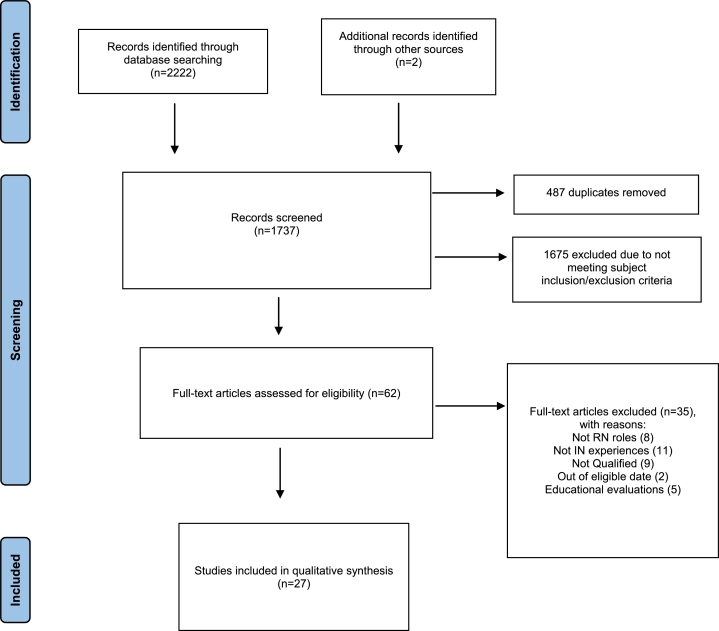

The key phrases [International OR overseas OR migra* OR foreign] AND [Nurs*] AND [Experiences OR perceptions OR attitudes OR views OR feelings] AND [Qualitative] identified articles addressing the experiences of registered nurses travelling abroad to work. From the initial database searches, 2222 records were identified. Duplicates (487) were removed, and the remaining 1737 articles were screened and tested for eligibility against the study inclusion/exclusion criteria through analysis of titles, abstracts and then in 62 instances, the full articles were reviewed. Studies were excluded if they failed to meet the requirements detailed in the SPIDER criterion (Table 1), and studies were only included if they were qualitative research, focussed on the experiences of internationally recruited nurses, written in English and published from 2010. In total, twenty seven papers were selected for quality appraisal. Fig. 1 shows the search strategy in full.

Table 1.

Search details conducted on 01 February 2021.

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample (S) | Internationally recruited nurses (that are nurses educated and registered in nursing prior to being recruited to work in a different country) travelling abroad to work in any health or care setting. | Not involving international nurses Allied Health Professionals Student health professionals |

| Phenomenon of Interest (P of I) | The centrality of experiences of international nurses educated and registered in a country different to the one they are working in. | Educational interventions |

| Design (D) | Interview, focus group, case study, or observational study. | Non qualitative approaches |

| Evaluation (E) | The perceptions, attitudes, views, feelings of international nurses working in a country different to the one they were initially educated and registered in. | |

| Research type (R) | Qualitative primary research. | Quantitative primary research Secondary research |

Fig. 1.

The search strategy in full.

3.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search strategy tool SPIDER (Cooke et al., 2012) was applied to define the key elements of the qualitative research questioning. Only qualitative research studies were included that had a primary outcome of experiences reported by internationally recruited nurses.

3.2. Study selection

A total of 2222 studies were retrieved from the electronic databases as follows: Medline (n=1658), CINAHL (n=258), PsychInfo (n=31), PubMed (n=274) and Web of Science (n=1). A further 2 additional sources were identified through reference lists. Duplicate papers were then removed, and studies were selected according to the eligibility criteria (see Fig. 1). Two reviewers (Author 1 and Author 3) independently screened titles and abstracts against the review criteria. Full texts of potentially relevant studies were retrieved and independently screened for eligibility. Reviewers were not blinded to study authors, their affiliations or the title of the journal. Any disagreements were resolved through the project advisory group (all review authors), although due to the specificity of inclusion criteria, contention was minimal, and all borderline decisions were recorded.

3.3. Quality appraisal

To determine the quality of the studies and to increase review reliability, a critical review of the final twenty seven selected papers was conducted. A Joanna Briggs Institute qualitative critical appraisal checklist was applied independently, by two of the review authors (Author 1 and Author 3) and applied systematically to each study and used to evaluate study quality, internal and external validity and reporting quality (Santos et al., 2018). Any questionable methodological concerns were reported; we did not however, exclude studies that met the reviews criteria on the grounds of perceived methodological quality. Each included study was scrutinised assiduously for the risk of bias in its conduct and data were similarly interrogated to confirm that these adequately supported the findings and any subsequent claims made for each study.

3.4. Data extraction and analysis

The data extraction from full text versions of each study were carried out using a data extraction form. The analysis process was conducted by two researchers and agreed by the project advisory group. We were focused on addressing the research aim and analysed the papers with this purpose. Therefore, the data extraction processes were formed following Braun and Clarke's (2006) six phase inductive thematic review process to identify, analyse and report patterns and themes in the research findings.

Once the analysts (author one and author three) were fully conversant with the selected papers, and they independently coded each section of data that captured or demonstrated relevance to the project aim. This process thereby established to classify the categories of information emerging from the selected research reported findings. Open coding was applied, therefore did not have pre-set codes to inform the analysis. The authors then met to discuss their initial coding, identifying overlap and any points of difference in coding schemas. At this stage it was clear there was a high degree of congruence in initial coding schemas, so these were combined. Initial codes [72] were then combined into the initial themes. These themes were refined through a process of discussion between author one and three to improve coherence and accuracy before discussion and agreement with the project advisory group. Each theme was present in at least nine of the papers reviewed for the study. The selected studies are summarised in Table 2 and identified themes linked to each paper.

Table 3.

Themes linked to selected papers.

| Author | Database | Themes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Adhikari (2015) | PsychInfo | Y | Y | ||||

| Alexis (2015) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Al-Hamdan (2015) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Allen (2018) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Brunton (2018) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Brunton (2019) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Choi (2019) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Connor (2016) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Connor (2014) | CINAHL | Y | Y | ||||

| Higginbottom (2011) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Jose (2011) | PsychInfo | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Kishi (2014) | CINAHL | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Likupe (2015) | MEDLINE | Y | |||||

| Lin (2014) | PsychInfo | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Mapedzahama (2011) | CINAHL | Y | |||||

| Neiterman (2013) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| O'Brien (2012) | PsychInfo | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| O'Neill (2011) | CINAHL | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Philip (2019) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | ||||

| Salma (2012) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Salami (2018) | MEDLINE | Y | |||||

| Smith (2011) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Thekdi (2011) | CINAHL | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Vafeas (2018) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Wolcott (2013) | MEDLINE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Zhou (2011) | CINAHL | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Zhou (2014) | PsychInfo | Y | Y | Y | |||

Theme 1: Individual and organisational preparedness 2: Communication and the art of language 3: Principles and practices of nursing 4: Social and cultural reality 5: Equality, diversity and inclusion 6: Facilitators of integration and adaptation

Table 2.

Characteristics of twenty seven selected studies.

| Author, year & country | Study design or methodology & data collection | Method of Analysis | Study aim/objectives | Sample and participant country of origin | Relevant findings to the current study | Study Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adhikari and Melia (2015) United Kingdom |

A multi-sited ethnographic approach In-depth interviews |

Analytical memos, themes & insights (Silverman, 2012) | … to examine Nepali migrant nurses’ professional life in the UK | Snowball sample of 21 Nepali Nurses | Professional aspirations Mismatched skills and expectations Deskilling and ‘brain waste’ |

High |

|

Alexis and Shillingford (2015) United Kingdom |

Husserl's phenomenological approach Semi-structured face-to-face interviews |

Colaizzi's (1978) analytical framework | … to explore the perceptions and work experiences of internationally recruited neonatal nurses | Purposeful sample of 13 nurses from Jamaica and the Philippines | Support mechanisms Unfamiliarity with family centred care Feelings of being treated like a child Coping strategies |

Moderate |

|

Al-Hamdan et al. (2015) United Kingdom |

Qualitative Face to face & phone interviews |

Content analysis | … how Jordanian nurses experienced the transition from home to host country to illuminate the elements of transformation | Snowball sample of 18 Jordanian nurses and 7 from other countries | Professional transformation Personal transformation Socio-cultural experiences. |

High |

|

Allen (2018) United States |

Qualitative, phenomenological study Demographic questionnaire and Open-ended interviews |

Colaizzi's (1978) seven-step phenomenological process | … to explore the experiences of internationally educated nurses in management positions in United States health care organisations. | Internal invitation for 7 IEN managers originally from Philippines (2), India (3), Jamaica (1) and China (1) | The role of supervisors in acceptance of management positions Challenges regarding job responsibilities Diversity and culture Language and communication Work relationships and support Opportunities for education and professional growth |

Moderate |

|

Brunton and Cook (2018) New Zealand |

Qualitative Interviews using a questionnaire schedule |

Thematic analysis | …to examine the viewpoints and experience of both NZ qualified nurses and internationally qualified nurses in managing communication within teams and the clinical practice context | Call through national nursing journal of 53 participants (17 New Zealand registered nurses and 36 internationally qualified nurses) | Interpersonal challenges Organizational challenges Value-based conflict and learning |

Moderate |

|

Brunton et al., (2019) New Zealand |

Qualitative Face to face interviews |

Thematic analysis and sensemaking theory | …the communication and practice experiences of migrant nurses in geographically distant, culturally dissimilar countries in Eastern and Western contexts | Call through journal of 36 nurses practising in NZ and 20 nurses practising in the UAE The NZ sample were from UK (8), China (5), the Philippines (11), India (9) and S Africa (3) UAE: 9 participants of Asian origin (Indian and Filipino), 7 Western (US, UK, Canada, S Africa and Romanian), 4 of Arab origin |

Lost in translation Who's in charge? “But I know best” Challenges to professionalism Who makes the decisions? |

High |

|

Choi et al (2019) New Zealand |

Qualitative: Interpretative Phenomenology Semi structured interviews |

Coded for common threads and meaning | … to explore the experiences of eight migrant nurses drawing on the concept of acculturation | Purposive sample of 8 nurses from India (5) and the Philippines (3) | Un/learning and the ‘hidden curriculum’ Destabilisation of expertise Preceptors and leaders as navigators Finding one's voice |

Moderate |

|

Connor (2016) United States |

Cross-sectional qualitative descriptive design Semi-structured interviews. |

Auerbach and Silverstein's (2003) qualitative analysis | … to explore the strategies that Filipino IENs use to cope effectively with their work-related and non-work-related stress. (Part of a larger study Connor et al 2014). | Purposive sample of 20 nurses from the Philippines | Coping behaviours and strategies: (a) familial, (b) intracultural, (c) fate and faith-based, (d) forbearance (patience and self-control) and contentment, (e) affirming the nursing profession and proving themselves, and (f) escape and avoidance |

Moderate |

| Connor et al. (2014) United States |

Qualitative: descriptive cross sectional Semi structured interviews |

Auerbach and Silverstein's (2003) qualitative analysis | …to explore the stresses and work experiences of Filipino immigrant nurses. | Purposive sample of 20 nurses from the Philippines | Specific stressors experienced: Immigration and resettlement challenges related to unexpected social and living environments. Immigration stressors interact with and intensify work-related stressors. Challenges arise from encountering cultural differences. |

Moderate |

|

Higginbottom (2011) Canada |

Ethnography Semi-structured interviews |

Roper & Shapira's framework for Ethnography | … to understand the transitioning experiences of IENs upon relocation to Canada and creating recommendations for improving the quality of their transition and their retention. | Purposive sample of 23 nurses from the Philippines (12), the Caribbean (2), UK (6) & NZ (3) | Motivation and decision to relocate Expectations versus actual experiences of recruitment, reception, salary & support on arrival The health care system nursing work environment Discrimination in the professional lives Life beyond the nursing setting Learning to overcome challenges |

High |

|

Jose (2011) United States |

Qualitative, phenomenology Guided interviews |

Giorgi's principles. | …to elicit and describe the lived experiences of internationally educated nurses who work in a multi-hospital medical centre in the urban USA. | Purposive sample of 20 nurses from the Philippines (8), Nigeria (5) and India (7) | Dreams of a better life, A difficult journey A shocking reality Rising above the challenges Feeling and doing better Ready to help others |

High |

|

Kishi et al. (2014) Australia |

Qualitative Semi structured interviews |

Thematic Analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). |

… to investigate the experiences of Japanese nurses and their adaptation to their work environment in Australia | Purposive and snowball sample of 14 Japanese nurses | Seeking: new/different experiences, stressful working environment, unsatisfactory working conditions, unhappy relationships in the workplace, Acclimatizing: struggles, languages, unfairness, active approaches, passive approaches, social support Settling: aspects subject to change, stepping away from the Japanese health work environment, future prospects, reaffirmation of sense of self-worth |

Moderate |

|

Likupe (2015) United Kingdom |

Qualitative (part of a larger study) Focus Group & individual interviews, |

van Manen's (1990) selective analysis. | …to explore experiences of racism, discrimination and equality of opportunity among black African nurses and their managers’ perspective on these issues. | Purposive sample of 36 nurses from sub-Saharan Africa (Malawi, Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Cameroon) | Perceptions of discrimination and racism from managers, colleagues and patients Lack of equal opportunities. Stereotyping |

Moderate |

|

Lin (2014) United States |

Qualitative In-depth interviews |

Strauss and Corbin (2008) comparing codes to develop categories, connections, and sequences. | … to increase understanding of perceptions of role transitioning into the US healthcare system by providing new information about their unique experience, and ways to help ease their transitions | Purposive sample of 31 nurses from the Philippines | Stages of adaptation: (1) pre-arrival, (2) early adaptation, and (3) late adaptation. Strategies for FNs, recruiting agencies, and recruiting facilities are also shown for each stage. |

Moderate |

| Mapedzahama et al. (2012) Australia |

Qualitative; Conceptual framework: Filomena Essed's (1991) theory of ‘everyday racism’. Individual interviews |

Interpretative approach, utilising thematic manual coding | … to examine how skilled African migrant nurses working in Australia forge social and professional identities within their transnational, cross-cultural existences | Snowballing sample of 14 black African nurses | The salience of skin colour: becoming the black nurse How black nurses experience everyday racism The white gaze and surveillance of the black nursing body Contesting racial stereotypes |

Moderate |

|

Neiterman and Bourgeault (2013) Canada |

Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

Thematic analysis | … to explore how and why cultural competence of IENs becomes a challenge in their professional integration. | Snowballing sample of 71 international nurses and 70 key stakeholders 29 different countries |

Cultural differences as a challenge to professional integration and lack of fit Language proficiency Nursing licensure examinations Local model of nursing practice Policy Solutions: facilitating integration Cultural competence |

High |

|

O'Brien and Ackroyd (2012) United Kingdom |

Comparative case study Multiple methods of data collection, including observations, semi structured interviews |

Assimilation model | … to gain an understanding of the processes underlying successful (or failing) assimilation of nurses into the long-term nursing labour force. | Overall, seven cohorts of international nurses from India (3 cohorts), the Philippines (2 cohorts) and Spain (2 cohorts). Convenience sample for 40 nurses for the interviews |

A comparative model of the key processes involved in the overseas nurse's assimilation process. Culture shock Home nurse attitudes and ‘everyday racism’ Informal occupational closure and occupational segmentation Formal occupational closure (or credentialism) Explaining patterns of variation in outcome for cohorts |

Moderate |

|

O'Neill (2011) Australia |

Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

Thematic Analysis | … how IENs for whom English is a second language engage with language and culture during their journey from the language classroom to the clinical context | Convenience sample of 10 nurses from India (5), Chinese (4) and Nepal (1) | Cultural and professional identity and belonging Competence & safety Adapting to new roles and ways of communicating are revealed |

Moderate |

| Philip, Woodward-Kron, Manias and Noronha (2019) Australia |

Qualitative Interview & Participant observation | Discourse Analysis | … to understand the interprofessional and intra-professional communication patterns of overseas qualified nurses as they coordinate care for patients in Australian hospitals | Convenience sample of 13 nurses from India (6), Philippines (6) and Nigeria (1) | Clinical communication: Coordinating care Communication strategies Discourse patterns Peer communication with peers Positive interpersonal interactions |

High |

|

Salma, Hegadoren and Ogilvie (2012) Canada |

Qualitative: Interpretive descriptive study Semi-structured interviews |

Thematic analysis (Green, 2007) | … to look at the perceptions of IENs regarding career advancement and educational opportunities in Alberta, Canada | Convenience and purposive sample of 11 nurses from Iran, Guyana, Britain, India, China and the Philippines. | Motherhood as a priority, communication and cultural challenges, Skill recognition, Perceptions of opportunity Mentorship. |

Moderate |

|

Salami, Meherali and Covell (2018) United States |

Exploratory transnational feminist qualitative research Interviews |

Thematic analysis | … to explore the experience of baccalaureate prepared IEN who work as licensed practical nurses in Canada. | Purposive & snowballing sample of 14 nurses from the Philippines (9), India (3), Nigeria (1) and Mauritius (1). | Migrating with hope for a better personal and professional life Experiencing barriers to RN workforce integration Deskilling and ambivalent skill recognition Feeling dissatisfied as an LPN in Canada |

Moderate |

|

Smith, Fisher and Mercer (2011) Australia |

Transcendental Phenomenology Individual interviews |

Moustakas's (1994) method of analysis | … to explore how overseas qualified nurses experienced the practice of nursing in WA, Australia. | Snowball sample of 13 Nurses from China, S Africa, Japan, Taiwan, Zimbabwe, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Sweden and Nepal. | Preparedness to work: it's the same… but it's different Working with patients: patient-centred approach Working with doctors: team approach, doctor–nurse hierarchy Feeling valued? etiquette and professionalism |

Moderate |

|

Thekdi et al. (2011) United States |

Qualitative Open ended interviews |

Thematic analysis | …to examine the transitional/ adaptation challenges of IENs in the U.S. healthcare system from multiple stakeholders: clinical educators, preceptors, and the IENs themselves | Recruitment of 6 nurses from India, Haiti, the Philippines, and the UK 4 clinical educators, and four preceptors |

FENs’ point of view Communication, Attitude of peers. Preceptors’ point of view Learning the “American way” of nursing. Clinical educators’ point of view Lack of initiative and autonomy. Communication challenges. Nursing practice knowledge. Cultural understanding between FENs and preceptors. |

Moderate |

|

Vafeas and Hendricks (2018) Australia |

Heuristic enquiry Focus group, individualised interviews & journal |

Coding and Thematic Analysis (Moustakas 1990) | … to understand the experience of migration for RNs moving from the UK to WA | Purposive and Snowball sample of 21 nurses from the UK | Making the move; finding a way New life; fitting in Here to stay |

Low |

|

Wolcott, Llamado and Mace (2013) United States |

Qualitative pilot study Interviews |

Constant comparison, thematic analysis | …to explore the experiences of IEN and the nurse managers and educators working with them, to understand the issues, and to highlight potential solutions for addressing integration challenges. | Purposive and snowballing sampling for 5 IEN from Denmark, Germany, India, Philippines and Portugal, their managers, and educators - | Communication difficulties Financial challenges Social support Educational orientations focused on culture, Nurse role Communication techniques. |

High |

|

Zhou et al. (2011) Australia |

Symbolic interactionist approach In-depth interviews |

Initial and focused coding and constant comparison of data | … to explore the social construction of difference and the related intersection of difference and racialisation | Snowball sample of 28 Chinese nurses | Difference in: - You are you and I am I - We cannot live a life like that - We are among but not in… Difference as: - ‘incompetence’ - ‘not knowing’ - ‘deviance’ |

Moderate |

|

Zhou (2014) Australia |

Grounded theory In-depth interviews |

GT analysis methods (Glazer 2005). | … to explore experiences of China-educated nurses working in Australia. | Purposive sample of 28 Chinese nurses | Reconciling different realities. Three phases of reconciling were conceptualised: realising, struggling, and reflecting. (Second publication of same study – Zhou et al 2011) |

High |

4. Findings

Of the twenty seven studies included in the review, papers from the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Canada presented the experiences of international nurses who had migrated from the Philippines and African regions. Indian nurses are represented in studies from the United Kingdom, United States, New Zealand, Australia and Canada. The United Kingdom, New Zealand and Canada publications included international nurses who had migrated from the Middle East, United States, New Zealand, Canada and a range of European countries. The themes identified were not unique and appeared to be transferable across the countries included in the review.

The final six themes presented are: (1) individual and organisational preparedness (2) communication and the art of language (3) principles and practices of nursing (4) social and cultural reality (5) equality, diversity and inclusion, and (6) facilitators of integration and adaptation.

4.1. Individual and organisational preparedness

Sixteen of the twenty seven papers presented some aspects of individual and/or organisational preparedness for the international nurses migrating to the host country. This theme is separated into two subcategories: motivations for migration and onboarding.

4.1.1. Motivations for migration

Despite wide-ranging motivations that inform the migration of international nurses, reasons for travelling to work in different countries can be sorted into professional factors, personal reasons or a combination of both. Professional factors include the desire to learn more skills, work in advanced health care systems with the latest technologies, gain better qualifications and strengthen work experience that can further nursing careers (Higginbottom, 2011; Adhikari and Melia, 2015; Alexis and Shillingford, 2015). In the studies, international nurses from low-income countries cited unfavourable working conditions and poor pay in their country of origin as motivations to migrate (Salami, 2018; Lin, 2014; Kishi et al., 2014), with motivations driven primarily by the need to improve social and economic conditions (Higginbottom, 2011). These studies often described this group of international nurses as deeply motivated with dreams of a better life and desires to provide a better future for their families and children (Jose, 2011), with responsibilities to families therefore serving as an important motivator of their migration (Jose, 2011). In contrast, alongside dissatisfaction with working conditions and poor pay in their countries of origin, international nurses from high-income countries who migrated to the UK, Australia and Canada were motivated primarily by a desire to travel and experience different lifestyles (Higginbottom, 2011; Vafeas and Hendricks, 2018).

4.1.2. Onboarding

The arrival and initial onboarding stage, (being, the process of occupational socialisation or integrating the newly hired employee into the organisation) is described as a period that causes significant anxiety and apprehension (Higginbottom, 2011; Lin, 2014; Connor and Miller, 2014; Alexis and Shillingford, 2015; Vafeas and Hendrick, 2018). Whilst some of the international nurses described their expectations as being met (Higginbottom, 2011; Lin, 2014; Connor and Miller, 2014), many describe negative experiences of recruitment and reception, primarily because of an absence of appropriate or sufficient support upon arrival to their destination countries (Higginbottom, 2011; Lin, 2014; Connor and Miller, 2014). Arrival in a new country is a time when international nurses hope for something new and for ‘dreams to come true’ (Vafeas and Hendricks, 2018), however, the studies outline persistent shortcomings in organisational preparedness that created significant impediments for individuals. Whilst the details of entry criteria, adaptation and induction programmes that prepare international nurses vary depending on the host country, the overall suggestion was that organisations are ill-prepared for receiving new international nurses: “I think they didn't know what to do with us when we came. They didn't know where to start with us, what to tell us. They had absolutely nothing planned for us. So, it was a stressful situation for all of us” (Alexis and Shillingford, 2015, p. 421). Onboarding stresses for international nurses are compounded by being far away from the support of loved ones and familiar cultures (Jose, 2011; Connor, 2016). This can result in a profound loneliness,a sense of loss and feeling overwhelmed during the period of change in work and everyday life (Zhou et al., 2011). Connections through mentorships and the importance of social networks are therefore noted as making significant differences to personal and professional induction at the start of the acculturation process (Wolcott, 2013; Lin, 2014; Vafeas and Hendricks, 2018).

4.1.3. Communication and the art of language

Fourteen of the twenty seven studies highlighted language and the art of communication as pertinent findings. This theme is separated into three subcategories: language and communication barriers, language and professional capability and language and the concept of belonging.

4.1.4. Language and communication barriers

A fundamental aspect to the provision of nursing care is the ability to communicate effectively to engage in clinical tasks (Kishi et al., 2014). Adapting to work in a new environment alongside difficulties of being able to effectively communicate in a second language is significant (O'Neill, 2011; Kishi et al., 2014; Philip et al., 2019), an issue highlighting a clear gap between international nurse preparation and the reality of nursing practices (O'Neill, 2011; Wilcott et al., 2013; Lin, 2014; Zhou, 2014; Philip et al., 2019). Language complexities such as regional dialects, colloquialisms, turns of phrase, conversational speeds, abbreviations and medical terminology can restrict international nurses from recognising the nuance of nursing situations (Neiterman & Bourgeault, 2013; Zhou et al., 2011; Kishi et al., 2014). These can create additional burdens on the complexity of overall interpersonal and written communication (Nieterman & Bourgeault, 2013; Kishi et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2011).

4.1.5. Language and professional capability

International nurses described a difficult balance of constructing a legitimate professional identity that is perceived as competent and safe, whilst asking questions to confirm and clarify linguistic uncertainties and understandings (O'Neill, 2011). Professional success is often described as hinging on the ability to communicate openly and with spontaneity (Zhou et al., 2011): “I sometimes don't understand what patients talk about. I still feel there is a big language barrier in front of me” (Kishi et al., 2014). Perceptions of clinical competence and safety was judged on communication skills, with language barriers often making international nurses appear incompetent rather than careful and thorough (O'Neill, 2011; Kishi et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2011); “when your language is not good you appear stupid and people look down on you”(Zhou et al., 2014, p. 6). In turn, when targeting promotion or development opportunities, less sociable international nurses described themselves as unable to apply for management positions because of the hinderance of language (Zhou et al., 2011) or the self-perception of being less knowledgeable than others (Thekdi et al., 2011, Salma et al., 2012).

4.1.6. Language and the concept of belonging

Philip et al. (2019) studied intra and interprofessional communication between linguistically diverse health and care workers, finding that whilst linguistic abilities were unequal, there was a distinct lack of workplace ‘small talk’ with team members of an English-speaking background. Conversely, interactions with international nurses were short and purposive, aimed at functionally completing nursing goals or activities. Language constraints can therefore result in the exclusion of comfort, fluency and spontaneity of their first language, ultimately leading to feelings of disempowerment, isolation and negative impact on sense of belonging (O'Neill, 2011; Philip et al., 2019). “I can function well in daily work. However, when it comes to a joke, usually everyone laughs except for me’ (Zhou et al., 2011 p. 5). In turn, international nurses in some studies reported a longing for lively exchanges and laughter in their first language, a lack of which resulted in feeling frustrated at not having the conversational gambits to articulate their identities (Kishi et al., 2014; Philip et al., 2014).

4.2. Principles and practices of nursing

Fifteen of the twenty seven studies highlighted contrasts in nursing models and variations in nursing practices as key impediments to successful integration of international nurses. This theme can be separated into two clear subcategories: different professional realities and deskilling and disempowerment.

4.2.1. Different professional realities

Whilst it was recognised that ‘nursing is nursing’ and ‘patients are patients’ regardless of national context (Higginbottom, 2011), and whilst no studies described the clinical competence of international nurses as a barrier to integration, major differences in professional realities, team dynamics and models of nursing care impact the adaptation of international nurses settling into a new milieu (Jose 2011). Many health and care systems in the developed countries adopt an autonomous, person-centred or holistic approach to nursing care, while developing countries undertake a more task-focused, medically driven model of nursing practices (Al Hamdan et al., 2015). This contrast can be explained by differences in developing countries in which families have a moral and practical obligation to provide hands-on and personalised care in activities of daily living (Zhou, 2014; Brunton & Cook, 2018). Levels of professional autonomy varies widely across health and care systems, with some cultures having greater emphasis on hierarchical management style where individuals are expected to obey commands without question (Allen, 2018). For example, in developing countries, nurses are not expected to question the doctor's absolute authority, whereas in developed countries nurses have greater independency and authority to make decisions in collaboration with wider caring teams (Neiterman and Bourgeault, 2013). Understanding the roles of international nurses within different health and care systems and the manner of interaction with managers, doctors and other members of health and care teams is therefore required for building assertiveness and critical thinking skills (Wolcott, 2013). However, this variation does not seem to be recognised by host nations, with one study highlighting the major adjustments required by international nurses to engage in activities not previously seen as the domain of registered nurses (Choi et al., 2019). Consequently, many international nurses can find themselves unprepared or ill-equipped to quickly assimilate to new and unaccustomed approaches to care (Adhikari and Melia, 2015).

4.2.2. Deskilling and disempowerment

International nurses experience challenges during the transition period, particularly when previous qualifications, authority and expertise are not recognised, or when they commence roles in junior positions or areas not matching previous experience or expertise (O'Brien, 2012; Neiterman and Bourgeault, 2013; Alexis and Shillingford, 2015; Choi et al., 2019). This can create unmet expectations which result in deskilling, frustrations, a perceived disempowerment with an associated downward professional mobility and ‘receding status’ (Adhikari and Melia, 2015; Choi, 2018).

4.3. Social and cultural reality

Nineteen of the twenty seven papers reported experiences associated with social and cultural realities within the orientation period. This theme is separated into two subcategories: personal sociocultural reality and cultural imprint and acculturation.

4.3.1. Personal sociocultural reality

In the initial months following migration, international nurses can experience feelings of cultural displacement (Higginbottom, 2011), with fundamental changes in social and nursing values challenging personal identity and resulting in cultural dissonance and disillusionment (Kishi, 2014; Brunton et al., 2019; Choi et al., 2019). Within this context, social interaction is essential for relationship-building, with the studies noting that international nurses would align themselves with a colleague or friend as a strategy for overcoming challenges and accessing social support in the form of information, peer and language assistance (Zhou et al., 2011; Wolcott, 2013; Kishi, 2014; Connor, 2016): “When I came to the hospital the first thing I do is look for the other Filipinos and then you feel comfortable … even if you do not know them… if there is another Filipino there; I feel like I belong” (Connor, 2016, p. 197).

4.3.2. Cultural imprint & acculturation

Culture is deeply ingrained in a sense of self, with immersion in cultures providing an important source of belonging despite having a taken-for-granted nature. Unsurprisingly, migration can throw cultural identity into disarray (Al-Hamdan et al., 2015). When moving between the cultures of different countries, individuals are required to make a psychological adjustment, referred to in the literature as acculturation. Cultural adaptation for international nurses inevitably occurs in a complex milieu (Brunton et al., 2019), where international nurses describe employing differing strategies to process their experience of change (Zhou et al., 2011). Some describe a passive acceptance and resigned willingness in transitioning to life in a different social setting (Jose, 2011). In this context, Wolcott (2013) suggests that greater attention to the cultural components of migration can be critical to smoother transitions for international nurses where nurse educators and managers can work in partnership to better support international nurses.

4.4. Equality, diversity and inclusion

A serious challenge facing international nurses globally is the frequent and varied examples of discrimination, racism and stereotyping. This is explicitly identified in nine of the twenty seven selected papers, with this theme separated into three categories: racism, discrimination, and impacts.

4.4.1. Racism

Overt hostility and racism, both within workplaces and wider societies, was an experience reported by international nurses who had moved to societies that now perceived them as ‘ethnic minorities’ (Mapedzahama et al., 2011; Higgingbotton, 2011; O'Brien, 2012; Likupe, 2015). Overt racism was more commonly reflected in patients’ attitudes towards being cared for by ‘racialised’ international nurses (meaning, nurses for whom ‘race’ was perceived as a differentiating feature) and were rarely perpetuated by host professionals (O'Brien, 2012). However, health professional colleagues’ can still express attitudes to international nurses that range from indifference to scarcely concealed hostility (O'Brien, 2012), with Black African nurses perceiving themselves as particular recipients of racism from white colleagues, managers and other white international nurses (Likupe, 2015). Passive racism can be compounded further by senior colleagues not managing or dismissing the racist behaviours of patients (Higgingbotton, 2011; Mapedzahama, 2011; Alexis & Shillingford, 2015). Likupe (2015, p. 235) cites evidence that an international nurse was told not to care for a number of patients because ‘they don't like to be looked after by a black person’, arguing divides in the experiences of international nurses are split between the ‘west and the rest’, with nurses from European and/or western cultures perceiving themselves as superior to international nurses from minoritised backgrounds.

4.4.2. Discrimination

In turn, international nurses describe feeling their nursing practice as under surveillance and excessive scrutiny compared with domestic colleagues (Mapedzahama et al., 2011; Higgingbotton, 2011; Likupe, 2015). Similar practices and incivilities are described by international nurses who had progressed to managerial positions, with the studies noting the widespread suggestion these international nurses perceived themselves as having to work harder and obtain better qualifications to gain similar posts to (white) host country nurses (Salma et al., 2012; Likupe, 2015; Allen, 2018). Concerns centred on fairness and equity in daily workload allocations, with occupational closure practices and overt discourtesy in the workplace creating perceptions that international nurses were treated differently to their counterparts (Alexis and Shilligford, 2015). Reflective of supervisory discriminatory practices, international nurses were assigned different duties, heavier workloads and menial tasks that put them at greater social and professional disadvantages (Higgingbotton, 2011; Zhou et al., 2011).

4.4.3. Impacts

The impact on the individual in response to racist and discriminatory behaviours is complex and varies in detail across the studies. Feelings of disappointment and unhappiness can replace the initial expectations and aspirations international nurses develop prior to migrating to a new country, with their hopes for a better life also threatened by the society outside of work (O'Brien, 2012). Acceptance and compliance is commonplace: [you are] ‘…made to feel small because of course we are alien here, you have to get used to it” (Lin et al., 2014 p. 686). This in turn leads to distress and confusion that are amplified by fears patients could make false, racially-biased accusations that in turn jeopardise positions and job security (Likupe, 2015). Likupe's (2015) cohort of Black African nurses suggested they were perceived as arrogant if they voiced dislike of their treatment by white colleagues. Conversely O'Brien (2012) reports that international nurses became ‘very quiet’, ‘non-assertive’ and/or ‘deferential’ and this was taken as evidence of acceptance of subservience; symptoms of a resigned willingness to comply rather than for properly resolved disagreements.

4.5. Facilitators of integration and adaptation

Nine of the twenty seven papers highlighted factors that support the integration and adaptation of international nurses into host countries. Interestingly, where successful integration was achieved, this was due much more to the motivation of the recruits to remain in host countries rather than effectiveness of provisions made to integrate them (O'Brien, 2012).

Whilst nursing practices vary, the professional or clinical competence of international nurses is not a complication reported throughout the literature within this review. However, recognition of the learner status of international nurses and their specific learning needs are highlighted as requiring focus on both a formal and informal basis (O'Brien, 2012). Organisational commitment to supporting international nurses is therefore crucial, with effective mentorship and supportive leadership emphasised as a pre-requisite for effective integration (Salma et al., 2012; Wolcott, 2013). The studies describe how informal support and connection with peers through social networks can make positive and significant differences to the personal confidence and process of professional integration (Wolcott, 2013; Lin, 2014; Vafeas and Hendricks, 2018). Both Vafeas and Hendricks (2018) and Lin (2014) emphasise the needs for new social connections and finding fresh ways to reconcile the cultural disparities associated with the lived experiences of new migrants.

5. Discussion

This review has explored the experiences of internationally-recruited nurses who have migrated to work in other countries. This builds on other reviews on the topic (Nichols and Campbell, 2010; Moyce et al., 2015; Pung and Goh 2017; Davda et al., 2018; Bond et al., 2020; Abuliezi et al., 2021) by focusing specifically on how facets of experiences may determine acculturation and inform desires to stay or leave positions. This review therefore details a broader retention lens on the international nursing workforce.

International nurses can be motivated by high expectations and aspirations for a new life for them and their families (O'Brien, 2012), the need to support their families financially through remittance (Dahl et al., 2021), and a desire to develop and experience professional growth that enhances careers within different health and care settings (Smith and Gillin, 2021). However, we revealed a mixed picture of these aspirations, expectations, desires and dreams being met, with many international nurses describing how they had entered new health and care workforce with many years of experience and qualifications yet became recruited into junior positions (Adhikari and Melia, 2015). Therefore, whilst professional and personal development broadly remain the two most reported reasons for migration, it is important for policy makers and employers to understand and manage individual experiences and migration motivations. Integration and support planning should be based on the holistic migration motivations of the individual nurse. Employers should also look to recognise, match and reward prior skills and experiences into employment opportunities based on the range of experiences and qualifications of the individual international nurse brings.

International nurses often leave friends and family behind, with this challenge compensated partly by developing strong transnational ties and maintaining links with associated cultures. We highlight how an individual's culture frames understanding and beliefs which in turn drives values and behaviours (Brunton et al., 2019; Choi et al., 2019). Cultural networks and the power of communities are therefore an essential component for successful retention, given the sense of non-belonging commonly reported when international nurses are not accepted, respected, valued, and not being part of defined groups (Skaria et al., 2019). International nurses can feel caught between two personal and professional realities, perhaps involving tensions between the desire to hold onto old identities and the need to change and integrate with new societies (Zhou et al., 2011; Kishi, 2014). Greater understanding of these tensions by employers with a focus on building and enhancing culturally-sensitive networks of support are therefore essential for promoting positive experiences, supporting job-embeddedness and perhaps strengthening longer term retention.

Language and communication is a major barrier to integration into the professional workforce and successful job-embeddedness within teams. Relative experience of integration will vary depending on country of origin and whether a new international nurse is arriving at a country with sufficient language proficiency. Greater acknowledgment and understanding of this experience by international nurses, recruiters and employers could assist overcoming language and communication barriers. To overcome these barriers, Moyce et al. (2015) suggest orientation training that could include common terminology encountered in practice, telephone communication and transcribing orders and medications in communication to reduce negative impact. In this context, some authors suggest that international nurses who find a new cultural and professional identity that accommodates linguistic limitations could lead to an improved sense of belonging (Kishi et al., 2014; Philip et al., 2014).

Nursing and patient care is recognised with underlining similarities regardless of national context (Higginbottom, 2011). It was the professional realities, team dynamics, models of nursing and population health which appeared to shape the experiences of international nurses working in new environments which varies depending on the nurse's country of origin. Contrasts in previous working cultures, team structures and dynamics of professional relationships, autonomy and clinical decision-making are important for employers to consider, particularly within orientation phases (Wolcott, 2013; Al-Hamdan et al., 2015).

The diversity of countries, language, cultures, political, social, religious and economic backdrops from which international nurses migrate mean that cultural backgrounds and nursing practices vary significantly when moving between countries. Individuals are required to make a psychological adjustment to their meaning system, a process referred to as acculturation (Lin, 2014). The orientation period where acculturation takes place can be described as the liminality period of migration. Liminality is an initial period of ambiguity and uncertainty which disrupts previous status and beliefs (Choi et al., 2019). The needs and challenges of international nurses during the liminality of migration and acculturation into the new workplace is multifaceted and complex. Learner needs are transient and change over time with initial international learner needs differing to those of ongoing career development. Meaningful recognition of prior experience and knowledge is essential at all stages of international nurses’ careers for personal and professional esteem and autonomy. While our review demonstrates great courage and resourcefulness of international nurses, this does not reduce the need to address the learner gap and provide adequate preparation and ongoing training for this group of highly skilled professionals (O'Neill, 2011).

Orientation programs should attempt to create a culture of safety for both patient and international nurses (Moyce et al., 2015). Moreover, the importance of acknowledging and understanding the international nurse unique learner status continues to echo throughout this review. Learner needs are transient and change over time with initial needs differing to those of ongoing career development. Meaningful recognition of prior experience and knowledge is essential throughout nursing careers for personal and professional esteem and autonomy. Employers in turn need to feel equipped to compassionately support the international nursing workforce with their unique learning needs. Recognising the increasing diversity of countries our nurses are being recruited from, employers must adapt their education and training needs accordingly.

Unfortunately, commonly reported is that international nurses experience racism and discrimination in all countries identified in the review. There were accounts of international nurses who had experienced overt racial discrimination perpetuated by patients, and there was also evidence of more subtle forms of discrimination perpetuated by colleagues and staff. It is important to note this differed sharply from the overt racism of patients/service users, and instead pertained to thoughts, feelings and perceptions. We found the concept of ‘racial microaggression’ appropriate for interpreting this form of discrimination, with racial microaggressions defined as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioural, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory or negative racial slights and insults to the target person or group’’ (Sue et al. 2007, p. 273). Previous literature indicates that international nurses face system-wide discrimination causing lack of opportunity at work, devaluing, deskilling and delay in career progression (Walani, 2015; Sands et al., 2020). This systematic review highlights that workplace discrimination can cause job dissatisfaction (Schilgen et al., 2017) and therefore may impact retention. To effectively move this agenda forward, policy makers should ensure robust and zero tolerance policies are enacted. This must include formal proactive anti-racist responses to inappropriate racist and discriminatory behaviours for all staff and service users.

Informal support and connection with peers can make a positive and significant difference to personal confidence and acculturation. Supportive supervision and strong leadership should lay excellent foundations on which to onboard international nurses and provide the platform on which to build opportunities for ongoing careers. Recruiters and employers should work in collaboration with international colleagues to help shape experiences, and this could be achieved by shared learning, embracing our diversity and unique perspectives, and ensuring strategic representation and presence from international nurses is visible in all high-level strategy discussions.

6. Limitations

This review should be considered within the limitations of the scope of the study. Whilst we have strived to examine experiences of international nurses working in a range of countries, it is important to note that available studies were based in five countries. These countries were all developed countries, and we attribute this to the established nature of research structures within developed countries more generally. It should also be noted that many studies only described the early stages of migration, exposing a potential gap in knowledge of longer term retention experiences.

7. Conclusion

Our research demonstrates that employers offer a range of career opportunities for international nurses including equitable pay, economic rewards and opportunities for continuing professional development.. Commitment by all who have a responsibility to support and retain international nurses is paramount, and within a culturally compassionate and professional sociocultural environment there is potential for international nurses to thrive. Policy makers must embrace differences and support international nurses learning needs to enable them to live and work in new social and professional realities. This could involve an optimisation of professional autonomy through recognition of prior experience and learner status to successfully integrate international nurses as they transition through the liminality phase and beyond to achieve career fulfilment. However, this paper has also identified significant areas to improve the integration and professional experiences in order to promote acculturation and longer term retention. Whilst recognising this review contains sobering empathies into international nurses’ post-migration experiences, we believe the insights provided needed to be systematically outlined to highlight how to positively effect change and improve future experiences. We conclude with a series of research recommendations to develop further understanding of the experiences of international nurses to support acculturation, which we believe may promote longer term retention:

-

•

Understand the complex interplay of teams, mentors, line managers and employers and their experiences of supporting international nurses.

-

•

Explore factors supporting successful integration into communities as well as understanding barriers to settling in different localities and how this may vary across different countries of origin.

-

•

Explore the range of approaches used for language integration and support to compare outcomes and any links to successful integration and retention.

-

•

Explore international nurses’ access to continuing professional development and long term career progression in comparison to host nurses.

Funding sources

No external funding.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Abuliezi R., Kondo A., Qian H.L. The experiences of foreign-educated nurses in Japan: a systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021;68(1):99–107. doi: 10.1111/inr.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari R., Melia K.M. The (mis)management of migrant nurses in the UK: a sociological study. J. Nurs. Manage. 2015;23(3):359–367. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamilla S., Kim B., Walker T., Sisson F. Acculturation, enculturation, perceived racism, and psychological symptoms among Asian American college students. J. Multicult. Counsel. Develop. 2017;45(1):37–65. doi: 10.1002/jmcd.12062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexis O., Shillingford A. Internationally-recruited neonatal nurses’ experiences in the National Health Service in London. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2015;21(4):419–425. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hamdan Z.M., Al-Nawafleh A.H., Bawadi H.A., James V., Matiti M., Hagerty B.M. Experiencing transformation: The case of Jordanian nurse immigrating to the UK. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015;24(15–16):2305–2313. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen L.A. Experiences of internationally educated nurses holding management positions in the United States: Descriptive phenomenological study. J. Nurs. Manage. 2018;26(5):613–620. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspen Institute . Aspen Institute; 2008. Policy Brief for the Global Policy Advisory Council The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and Health Worker Migration [Policy brief]https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/files/content/images/GCC%20and%20HWM%20Policy%20Brief.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bludau H. Global healthcare worker migration. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Bond S., Merriman C., Walthall H. The experiences of international nurses and midwives transitioning to work in the UK: A qualitative synthesis of the literature from 2010 to 2019. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020;110(103693) doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunton M., Cook C. Dis/Integrating cultural difference in practice and communication: a qualitative study of host and migrant Registered Nurse perspectives from New Zealand. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018;83:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunton M., Cook C., Kuzemski D., Brownie S., Thirlwall A. Internationally qualified nurse communication—a qualitative cross country study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019;28(19–20):3669–3679. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan, J., Jobanputra, R., Gough, P., & Hutt, R. (2005). Internationally-recruited nurses in London. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.477.2700&rep=rep1&type=pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Buchan, J., Shaffer, F. A., & Catton, H. (2018). Policy Brief: Nurse Retention. https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/2018_ICNM%20Nurse%20retention.pdf.

- Buchan, J., Catton, H., & Shaffer, F. A. (2022). Sustain and Retain in 2022 and Beyond.https://www.enc22.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Sustain-and-Retain-in-2022-and-Beyond-The-global-nursing-workforce-and-the-COVID-19-pandemic.pdf.

- Choi M.S., Cook C.M., Brunton M.A. Power distance and migrant nurses: the liminality of acculturation. Nurs. Inq. 2019;26(4) doi: 10.1111/nin.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke A., Smith D., Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J.B. Cultural influence on coping strategies of Filipino immigrant nurses. Workplace Health Safety. 2016;64(5):195–201. doi: 10.1177/2165079916630553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J.B., Miller A.M. Occupational stress and adaptation of immigrant nurses from the Philippines. J. Res. Nursing. 2014;19(6):504–515. doi: 10.1177/1744987114536570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl K., Bjørnnes A.K., Lohne V., Nortvedt L. Motivation, Education, and Expectations: Experiences of Philippine Immigrant Nurses. SAGE Open. 2021;11(2) 3657021582440211016554. [Google Scholar]

- Davda L.S., Gallagher J.E., Radford D.R. Migration motives and integration of international human resources of health in the United Kingdom: Systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies using framework analysis. Human Resources for Health. 2018;16(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0293-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas H., Castles S., Miller M.J. Red Globe Press; 2019. The Age Of Migration: International Population Movements In The Modern World. [Google Scholar]

- Efendi F., Kurniati A., Bushy A., Gunawan J. Concept analysis of nurse retention. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019;21(4):422–427. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerchow L., Burka L.R., Miner S., Squires A. Language barriers between nurses and patients: a scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021;104(3):534–553. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbottom G.M.A. The transitioning experiences of internationally-educated nurses into a Canadian health care system: A focused ethnography. BMC Nursing. 2011;10(14):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein S., Stevens M., Manthorpe J. Migrants’ motivations to work in the care sector: experiences from England within the context of EU enlargement. Eur. J. Ageing. 2013;10(2):101–109. doi: 10.1007/s10433-012-0254-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose M. Lived experiences of internationally educated nurses in hospitals in the United States of America. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2011;58:123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingma M. Cornell University Press; 2018. Nurses on the move: Migration and the global health care economy. [Google Scholar]

- Kishi Y., Inoue K., Crookes P., Shorten A. A model of adaptation of overseas nurses: exploring the experiences of Japanese nurses working in Australia. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2014;25(2):183–191. doi: 10.1177/1043659613515716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likupe G. Experiences of African nurses and the perception of their managers in the NHS. J. Nurs. Manage. 2015;23(2):231–241. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.C. Filipina nurses’ transition into the US hospital system. J. Immigr. Minority Health. 2014;16(4):682–688. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapedzahama V., Rudge T., West S., Perron A. Black nurse in white space? Rethinking the in/visibility of race within the Australian nursing workplace. Nurs. Inq. 2011;19(2):153–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyce S., Lash R., Lou de L., Siantz M. Migration experiences of foreign educated nurses: a systematic review of the literature. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2015;27(2):181–188. doi: 10.1177/1043659615569538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiterman E., Bourgeault I.L. Cultural competence of internationally educated nurses: Assessing problems and finding solutions. Canad. J. Nursing Res. Arch. 2013:88–107. doi: 10.1177/084456211304500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. (2019). The NMC Register.https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/data-reports/march-2019/nmc-register-data-march-19.pdf?visitorgroupsByID=undefined. Accessed 04 April 2022.

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2015). The New Zealand nursing workforce. http://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/download/186/31march2010.pdf. Accessed 15 December 2021.

- Nichols J., Campbell J. The experiences of internationally-recruited nurses in the UK (1995–2007): an integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010;19(19–20):2814–2823. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. (2019). International migration and the healthcare workforce.https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/articles/internationalmigrationandthehealthcareworkforce/2019-08-15. Accessed 15 December 2021.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . Health at a Glance: OECD Indicators Paris. OECD; 2017. Foreign-trained Doctors and Nurses. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien T., Ackroyd S. Understanding the recruitment and retention of overseas nurses: realist case study research in National Health Service Hospitals in the UK. Nurs. Inq. 2012;19(1):39–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2011.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill F. From language classroom to clinical context: The role of language and culture in communication for nurses using English as a second language. A thematic analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011;48(9):1120–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip S., Woodward-Kron R., Manias E, Noronha M. Overseas Qualified Nurses’(OQNs) perspectives and experiences of intraprofessional and nurse-patient communication through a Community of Practice lens. Collegian. 2019;26(1):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2018.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pung L.X., Goh Y.S. Challenges faced by international nurses when migrating: an integrative literature review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017;64(1):146–165. doi: 10.1111/inr.12306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth C., Berger S., Krug K., Mahler C., Wensing M. Internationally trained nurses and host nurses’ perceptions of safety culture, work-life-balance, burnout, and job demand during workplace integration: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing. 2021;20(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00581-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salma J., Hegadoren K.M., Ogilvie L. Career advancement and educational opportunities: experiences and perceptions of internationally educated nurses. Nurs. Res. 2012;25(3):56–67. doi: 10.7939/R3GT0G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salami B., Meherali S., Covell C.L. Downward occupational mobility of baccalaureate‐prepared. internationally educated nurses to licensed practical nurses. International Nursing Review. 2018;65(2):173–181. doi: 10.1111/inr.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands S.R., Ingraham K., Salami B.O. Caribbean nurse migration—a scoping review. Human Resources For Health. 2020;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00466-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilgen B., Nienhaus A., Handtke O., Schulz .H., Mosko M. Health situation of migrant and minority nurses: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos W., Secoli S., Püschel V. The Joanna Briggs Institute approach for systematic reviews. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2018;26 doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.2885.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaria R., Whitehead D., Leach L., Walshaw M. Experiences of overseas nurse educators teaching in New Zealand. Nurse Educ. Today. 2019;81:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.D.A., Fisher C., Mercer A. Rediscovering nursing: A study of overseas nurses working in Western Australia. Nurs. Health Sci. 2011;13(3):289–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue D.W., Capodilupo C.M., Torino G.C., Bucceri J.M., Holder A.M.B., Nadal K.L., Esquilin M. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. Am. Psychol. 2007;62(4):271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M., Walton-Roberts M. International nurse migration from India and the Philippines: the challenge of meeting the sustainable development goals in training, orderly migration and healthcare worker retention. J. Ethnic Migration Stud. 2019;45(14):2583–2599. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1456748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thekdi P., Wilson B.L., Xu Y. Understanding post-hire transitional challenges of foreign-educated nurses. Nurs. Manage. 2011;42(9):8–14. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000403285.34873.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . United Nations; 2020. Migration.https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/migration Accessed 15 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Walani SR. Global migration of internationally educated nurses: experiences of employment discrimination. Int. J. Africa Nurs. Sci. 2015;3:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2015.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolcott K., Llamado S., Mace D. Integration of internationally educated nurses into the US workforce. J. Nurses Profession. Develop. 2013;29(5):263–268. doi: 10.1097/01.NND.0000433145.43933.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafeas C., Hendricks J. A heuristic study of UK nurses’ migration to WA: Living the dream downunder. Collegian. 2018;25(1):89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2017.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]