Abstract

Background

Inadequate training on how to care for haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheters can lead to mechanical issues with the catheters and infectious complications (such as peritonitis) that could endanger patient safety, reduce the effectiveness of the dialysis treatment, and have a negative impact on patient morbidity and mortality. Such incidents can be prevented as they are mostly dependant on controllable factors – proper dialysis catheter care, which can be addressed through effective patient education. Effective patient education is crucial in ensuring that patients are equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary for both peritoneal and haemodialysis catheter care.

Aims

To synthesise evidence on the: (1) patient educational interventions on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care; and (2) reported learning and clinical outcomes of the educational interventions provided for patients with haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter.

Design

Integrative review.

Methods

This review followed the framework by Whittemore and Knafl. The literature search was performed using four electronic databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tool was used to appraise the articles that fit the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies published in the English language were retrieved.

Results

A total of 14 studies were included. All the studies focused on educating patients who were on either tunnelled (permanent) haemodialysis catheters or peritoneal dialysis catheters. The findings identified: (1) teaching strategies used for educating patients on haemodialysis catheter care (2) teaching strategies for educating peritoneal dialysis patients on peritoneal dialysis catheter care and (3) outcomes of patient education on both haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheters. Written materials and educational videos were used to instruct patients on haemodialysis catheters care. Different educational strategies for educating patients on peritoneal dialysis catheter care were also reported. They varied in terms of the composition and experience of the implementation care team members, educational approach, training duration, training location, timing relative to catheter placement, assessment method and follow-up support. The various teaching strategies were assessed and compared based on the patients' knowledge levels, catheter-related mechanical issues, and catheter-related infectious consequences (such as peritonitis).

Conclusion

This review highlighted various education materials and compared different educational practices on tunnelled (permanent) haemodialysis catheter and peritoneal dialysis catheter care that healthcare providers used to increase knowledge and reduce catheter-related blood stream infections and peritonitis rates.

Keywords: Patient education interventions, Peritoneal dialysis catheter care, Haemodialysis catheter care

What is already known?

-

•Inadequate training on how to properly care for haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter may result in catheter-related mechanical problems and infectious complications that can endanger patient safety, reduce the effectiveness of dialysis treatment and negatively affect patient morbidity and mortality.

-

•Educational strategies have been used to teach haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care; however, little is known about their effectiveness.

-

•

What this paper adds

-

•Inconclusive evidence on the efficacy of written materials and educational videos in improving knowledge on haemodialysis catheter care and reducing catheter-related mechanical and infectious complications.

-

•The use of written support and audio support, practical evaluation tools, inviting vendors from peritoneal dialysis companies to teach, requiring a minimum training duration of more than 15 h, implementing peritoneal dialysis programs using multisensory approaches or adult learning theory have all been reported to be effective teaching strategies in the education on peritoneal dialysis catheter care in reducing catheter-related infectious complications.

-

•

1. Introduction

End-stage kidney disease burden on the world's health system is rising quickly (Thurlow et al., 2021). In 2010, an estimated 2.6 million individuals received either haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis globally (Liyanage et al., 2015). Dialysis usage is anticipated to double to 5.4 million individuals worldwide by 2030, with Asia experiencing the most significant rise (Liyanage et al., 2015). Although the native arteriovenous fistula and arteriovenous grafts are widely considered the preferred vascular access option for most haemodialysis patients (Santoro et al., 2014), they are still initiated on tunnelled and non-tunnelled haemodialysis catheters due to varying reasons. The most commonly quoted reasons for the use of haemodialysis catheters were patients’ denial towards the need for dialysis, failure to establish permanent vascular access early, failure of the permanent vascular access to mature in time for use (Yap et al., 2018) or when patients switched from peritoneal to haemodialysis due to catheter-related infectious complications, causing peritoneal dialysis to be discontinued (Teakell and Piraino, 2022). Peritoneal dialysis usage has also increased steadily from 289,000 patients in 2014 to 424,000 patients in 2021 (Fresenius Medical, 2014). Therefore, it is crucial to ensure that patients are aware of how to properly care for both haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheters that serve as their lifelines.

Inadequate training on how to properly care for haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter can result in catheter-related mechanical problems (e.g., catheter dysfunction, bleeding and haematoma) and catheter-related infectious complications (e.g., peritonitis) that can compromise patient safety, reduce the effectiveness of dialysis treatment and negatively affect patient morbidity and mortality (Ma et al., 2020). Nonetheless, such incidents can be prevented as they are mostly dependant on controllable factors – proper dialysis catheter care, which can be addressed through effective patient education (Béchade et al., 2017). Therefore, effective patient education is crucial in ensuring that patients are equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary for both peritoneal and haemodialysis catheter care. A systematic literature search will inform effective educational practices and may help to reduce catheter-related mechanical complications and catheter-related infectious complications.

2. Aim

This integrative review aimed to synthesise (1) evidence on the patient educational interventions on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care and (2) reported learning and clinical outcomes of the educational interventions provided for patients with haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter.

The research questions were as follows:

-

1

What are the current evidence-based patient education interventions used to educate adult patients on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care?

-

2

What are the current clinical and reported learning outcomes of the published educational programs on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care amongst adult dialysis patients?

3. Design

An integrative review methodology was adopted, following the structured framework by Whittemore and Knafl (2005). The proposed framework incorporated five key phases: (i) formulation of key issues; (ii) conduct of literature search; (iii) evaluation of data; (iv) analysis of data, and (v) presentation of findings. All articles that met the inclusion criteria were included in the data analysis. Data were extracted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and guidelines (Moher et al., al., 2009).

3.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

The search was carried out by three reviewers (FL, JC, and SH) from October 2022 to November 2022. The search for primary studies was conducted using four electronic databases – PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Library and ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health. Secondary sources from journal reference lists and grey literature were also explored. The title and abstracts were first screened for relevance. The reviewers then retrieved the full-text of the publications that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and evaluated them for relevance. Before all the reviewers agreed on the articles to be included in the integrative review, no further data extraction was done.

The search strategy made use of Medical Subject Headings and keywords such as “patient education”, “haemodialysis catheter care”, “peritoneal dialysis catheter care”, “dialysis”, “pedagogies”, “temporary dialysis catheters”, “permanent dialysis catheters”, “dialysis catheter-related outcomes”, combined using Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’. The spelling of key variables such as haemodialysis vs haemodialysis and tunnelled vs tunnelled were also applied. All preliminary searches were limited to the English Language with no limit on the publication year.

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used for the selection of studies:

Inclusion Criteria

-

•

Studies published in the English language with full text and peer-reviewed;

-

•

Study participants were adults (aged 21 years and above);

-

•

Studies which discussed strategies used to educate patients on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care; and

-

•

Studies that reported on the outcomes measures of patient education on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care

Exclusion Criteria

-

•

Studies that did not mention patient education for patients on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care

-

•

Studies which did not state the education strategy used and did not describe the outcomes measured.

-

•

Articles published as informational pieces, literature reviews, study protocols and abstracts

3.2. Search outcome

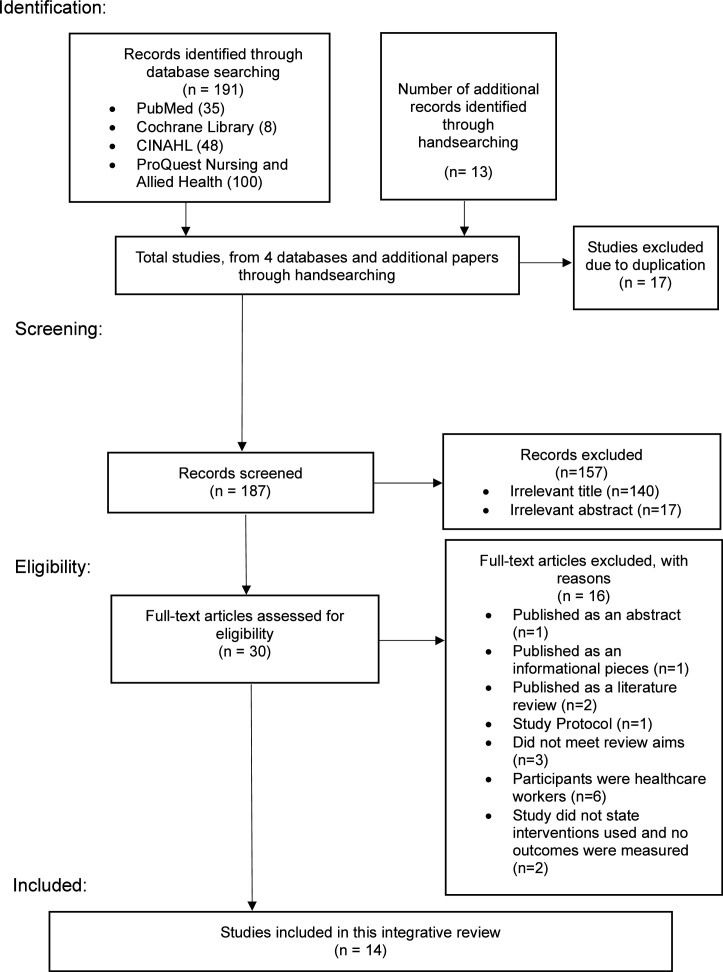

The search yielded a total of 203 articles from PubMed (n = 35), Cochrane library (n = 8), CINAHL (n = 48), ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health (n = 100) with additional records identified through hand searches (n = 13). Seventeen duplicate articles were removed, and for the remaining 186 articles, title and abstracts were examined by the primary author. Irrelevant articles (n = 157) were removed resulting in 30 full-text articles assessed for eligibility. Only 14 articles were eligible for this integrative review. The literature search is summarised in Fig. 1 according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses convention (Moher et al., al., 2009).

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow diagram. Adapted form Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Sytematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097.

3.3. Quality appraisal

The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tool was used to critically evaluate the quality of selected articles for different study designs (Table 1). A data extraction table was crafted to organise data clearly and concisely (Table 2). All included studies were assessed based on the methodological quality and magnitude of each study in addressing the probability bias in its design, methods, and analysis, except for the study by Maia et al. (2019), whose study design was not covered by the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist because it focused on validating the educational tool created by the study. Five different Joanna Brigg Institute checklist were employed to screen the randomised controlled trial (n = 1), quasi-experimental (n = 3), cohort (n = 5), analytical cross sectional (n = 2) and text and opinion papers (n = 2) (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c). Based on the levels of evidence, the included articles’ level of effectiveness ranged from one to five.

Table 1.

Overview of quality appraisal of included studies and JBI checklist used.

| JBI checklist for randomised control trial | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article number | 1 | ||||

| First author/ (year) | Kotwal et al. (2022) | ||||

| Was true randomization used for assignment of participants to treatment groups? | Yes | ||||

| Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? | No | ||||

| Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? | Yes | ||||

| Were participants blind to treatment assignment? | Yes | ||||

| Were those delivering treatment blind to treatment assignment? | No | ||||

| Were outcomes assessors blind to treatment assignment? | Yes | ||||

| Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? | Yes | ||||

| Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analysed? | Yes | ||||

| Were participants analysed in the groups to which they were randomized? | Unclear | ||||

| Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? | Yes | ||||

| Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | Yes | ||||

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | ||||

| Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | Yes | ||||

| Was the trial design appropriate, and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | Yes | ||||

| Included | Yes | ||||

| Quality scores (%) | 10/13=76.9% | ||||

| Level of evidence (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c) | 1.c | ||||

| JBI checklist for quasi experimental study | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article number | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| First author/ (year) | Mokrzycki et al. (2021) | Fadlalmola et al. (2020) | Neville et al. (2005) | ||

| Is it clear in the study what is the ‘cause’ and what is the ‘effect’ (i.e. there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Were the participants included in any comparisons similar? | Unclear | Yes | Yes | ||

| Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care, other than the exposure or intervention of interest? | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Was there a control group? | Yes | No | Unclear | ||

| Were there multiple measurements of the outcome both pre and post the intervention/exposure? | No | Yes | Yes | ||

| Was follow up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analysed? | No | Yes | No | ||

| Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | ||

| Included | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Quality scores (%) | 5/8 = 62.5% | 8/9 = 88.9% | 8/9 = 88.9% | ||

| Level of evidence (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c) | 2.d | 2.d | 2.c | ||

| JBI checklist for cohort studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article number | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| First author/ (year) | Gadola et al. (2013) | Figueiredo et al. (2014) | Gadola et al. (2019) | Bonnal et al. (2020) | Cheetham et al. (2022) |

| Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population ? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were confounding factors identified? | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Were the groups/participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or at the moment of exposure)? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was follow-up time reported and sufficient to be long enough for outcomes to occur? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was follow-up complete, and if not, were the reasons to loss to follow-up described and explored? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Were strategies to address incomplete follow-up utilised? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Included | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Quality scores (%) | 11/11=100% | 10/11=90.9% | 11/11=100% | 10/11=90.9% | 10/11 = 90.9% |

| Level of evidence (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c) | 3.e | 3.e | 3.e | 3.e | |

| JBI checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article number | 10 | 11 | |||

| First author (year) | Bordin et al. (2007) | Bernardini et al. (2006) | |||

| Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Unclear | Yes | |||

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Yes | Yes | |||

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | |||

| Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Yes | Unclear | |||

| Were confounding factors identified? | No | Unclear | |||

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | No | Unclear | |||

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Unclear | Yes | |||

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | Yes | |||

| Included | Yes | Yes | |||

| Quality scores (%) | 5/8 = 62.5% | 5/8 = 62.5% | |||

| Level of evidence (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c) | 4.b | 4.b | |||

| JBI checklist for text and opinion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article number | 12 | 13 | |||

| First author (year) | Dinwiddie et al. (2010) | Dinwiddie (2004) | |||

| Is the source of the opinion clearly identified? | Yes | Yes | |||

| Does the source of opinion have standing in the field of expertise? | Yes | Yes | |||

| Are the interests of the relevant population the central focus of the opinion? | Yes | Yes | |||

| Is the stated position the result of an analytical process, and is there logic in the opinion expressed? | Yes | Yes | |||

| Is there reference to the extant literature? | Yes | Yes | |||

| Is any incongruence with the literature/sources logically defended? | Not applicable | Not applicable | |||

| Included | Yes | Yes | |||

| Quality scores (%) | 5/5 = 100% | 5/5 = 100% | |||

| Level of evidence (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c) | 5.b | 5.c | |||

Table 2.

Overview of data extraction and characteristics of selected studies.

| Author(s)/year/country | Study aim | Outcome measured | Study design/methods | Sample characteristics/Setting/selection criteria | Relevant findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bernardini et al. (2006) United States, Canada, South America (Brazil, Columbia), The Netherlands, Hong Kong. | To survey nurses around the world about current practices for peritoneal dialysis (PD) home training programs | Peritonitis rates | Quantitative Survey based cross-sectional study design 16-items questionnaire constructed by International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) Nursing Liaison Committee sent by fax, mail, hand carried or conducted by phone |

n = 317 nurses n = 88 nurse (United States) n = 46 nurses (Canada) n = 58 (South America) n = 58 (Hong Kong) n-67 (Netherlands) |

|

| Bordin et al. (2007) Italy | Describes characteristics of education pre- dialysis (EPD), training, home visits (HV) and re-training (RT) used in Italy Evaluates the relationship between these programmes and peritonitis rates |

Peritonitis rates | Quantitative Observation study Questionnaires consisting of 40 questions, distributed by fax or e-mail during November and December 2006. |

n = 120 PD centres Public PD centres in Italy, which had been active for at least two years and had more than 10 adult patients. |

|

| Bonnal et al. (2020) France | Describe educational practices proposed to Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) patients Evaluate the effect of educational practices on the risk of peritonitis |

Occurrence of peritonitis amongst patients who receive different PD education practices | Quantitative Observational retrospective multicentric study based on data from a French Language Peritoneal Dialysis Registry from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2016 Data about the educational practices used during PD training were retrieved: (1) timing of the education regarding catheter placement, (2) whether education was provided by a nurse specialised in PD, (3) the use of audio file or printed booklet (inclusive of assessment of patients’ knowledge, and skills concerning PD with an evaluation grid), (4) the use of standard theoretical courses or adapted theoretical courses, (5) start of learning with theory or with hands-on-training |

n = 1035 (n = 937 were autonomous patients, n = 98 were family-assisted patients) n = 667 male n = 368 female Patients from 74 PD units who receive continuous ambulatory PD, automated PD, newly initiated PD and PD in administrative type of centre (non-profit, general, university or private hospital) Adults age ≥18 years when starting PD PD exchanges not assisted by nurses |

|

| Cheetham et al. (2022) United States of America | Describe and compare international PD training practices and their association with peritonitis | First peritonitis episode | QuantitativeProspective cohort studyPeritonitis episode and hospitalisations were obtained by manual abstraction of data from medical chartsTwo questionnaires used:

|

Clinic staff completed a total of 1376 medical questionnaire on patients n = 135 (Australia/New Zealand) n = 341 (Canada) n = 222 (Japan) n = 312 (Thailand) n = 127 (United Kingdom) n = 239 (United states of America) 120 PD centres returned the 14-item survey |

|

| Dinwiddie (2004) North America | Present a methodology to protect prescribed dialysis dose by team management of catheter dysfunction | Not Applicable | Text & Opinion | Not Applicable |

|

| Dinwiddie et. al (2010) North America | Describe current haemodialysis (HD) catheter usage and complications in North America Provide an overview of the research and recommendations for nephrology nursing in caring for adult and paediatric patients who use a catheter for HD Describe team approach and continuous quality improvement process in implementing these recommendations |

Not Applicable | Text & Opinion | Not Applicable |

|

| Fadlalmola et. al (2020) Saudi Arabia | Evaluate the effectiveness of an educational program on the knowledge and quality of life amongst haemodialysis patients in Khartoum state | Primary outcome: Patients’ knowledge regarding the concept of haemodialysis, catheter and fistula, care of vascular access, complications and problems associated with haemodialysis, diet, fluid restrictions, medications, recommended activities to adapt to HD Secondary outcome: Quality of life relating to health, social psychological, spiritual, and family |

Quantitative Quasi-experimental pre- and posttest design Pretest for the existing knowledge for patients was carried out pre-intervention using interview questionnaire format (15mins). Each participant will also be assessed for Quality of Life by Ferrans and Powers Quality of Life Index of dialysis. Thereafter, participants will receive the educational program which will be continued for 3 months Post-intervention data collected 6 months after the education program |

n = 100 HD patients n = 59 male n = 41 female HD units in Khartoum state Adults age ≥18 years, on regular haemodialysis not less than 6 months, attended the educational intervention program, without complications |

|

| Figueiredo et al. (2014) Brazil | Evaluate the impact of training characteristics on peritonitis rates in Brazilian cohort | Primary outcome: Incidence rate of peritonitis Secondary outcome: Time to first peritonitis |

QuantitativeProspective cohort studyAdult patients from 122 PD centres in BrazilJanuary 2008 to January 2011Data on training:

|

n = 2243 patients from 122 PD centres n = 1162 females n = 1081 males |

Patients who receive:

|

| Gadola et al. (2013) South America | Evaluate an Objective Subjective Assessment (OSA) tool in assessing patients’ skills and impact on peritonitis rates of a new multidisciplinary peritoneal dialysis (PD) education program (PDEP) | Peritonitis rates | QuantitativeRetrospective cohort analysis studyPhase 1: OSA toolPD bag exchange methods and troubleshooting questions were evaluated using an OSA based on the Objective Structured Clinical AssessmentPhase 2: New Peritoneal Dialysis Education Programme (PDEP)

|

n = 25 patients (phase 1) Patients with adequate Kt/V and no mental disabilities who had been on PD for more than 1 month. n = 31 (phase 2) n = 24 patients who were on PD for least 1 month n = 7 caregivers as patients incapable of performing the bag exchange (blindness, motor disabilities, OSA failure) Uruguayan PD centre |

|

| Gadola et al. (2019) South America | Evaluate peritonitis risk factors and its prevention with a new peritoneal educational program (NPEP). | Primary outcome: Incidence rate of peritonitis (episodes/patient-months) Secondary outcome: Time to first peritonitis |

QuantitativeRetrospective analysis cohort studyInitial Peritoneal Education Program(IPEP)

|

n = 222 patients n = 88 patients (IPEP) n = 134 patients ((NPEP) Chronic PD patients, older than 16 years old, begin PD from 1 January 1999 to 31 December 2015 with follow-up until 31 December 2016 Uruguayan PD centre |

|

| Kotwal et al. (2022) Australia | Identify whether multifaceted interventions, or care bundles, reduce catheter related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs) from central venous catheters (CVC) used for haemodialysis (HD) | Primary outcome: Rate of CRBSI per 1000 catheter days of use between the baseline and intervention trial phases Secondary outcome: Rate and incidences of suspected or possible CRBSI, total CRBSI (confirmed, suspected and possible), all HD CVC related infectious events |

Quantitative Stepped wedge, cluster randomised design After a baseline observational phase, a service-wide multifaced intervention bundle that included elements of catheter care was implemented at one of three randomly assigned time points (insertion, maintenance, and removal) between 20 December 2016 and 31 March 2020. Baseline (at all 3 time points): Receive standardised catheter care as part of the pre-existing guidelines i.e. use of antimicrobial impregnated dressing or locking solutions etc. Intervention (insertion and maintenance): Receive standardised catheter care and education using the REDUCTION catheter care sheet on the following topics: vascular access care, hand hygiene, risks related to catheter use, recognising signs of infection, instructions for access management, ensure catheter and exit sites are kept dry, seek assistance if dressing wet, soiled or slipped out, not to shower in first 72 hrs after catheter insertion |

n = 3519 (baseline phase) n = 2845 (intervention phase) mean age = 60.7 years (SD=15.9) 37 renal services across Australia Adults age ≥18 years under the care of a renal service who required insertion of new HD catheter |

Primary outcome:

|

| Maia et al. (2019) Brazil | Create and validate an instructive folder for the self-care of patient using a haemodialysis catheter | Not Applicable | Methodological study based on constructivist paradigm Stage 1 – Creation of an instructional folder to provide information on catheter definition/conceptualisation, and its purpose, time of use, risks and complications and catheter maintenance care Stage 2 – Validate the content and style through expert evaluation |

n = 13 experts n = 3 physicians n = 8 nurses n-2 pedagogist Validation conducted by professionals experts with (1) higher education in medicine or nursing and speciality in nephrology and (2) professional experience of at least 2 years working in haemodialysis area |

|

| Mokrzycki et al. (2021) United States | Determine the feasibility of implementing an electronic catheter checklist (ECC) in outpatient dialysis facilities | Primary outcome: Total number of audits/observations in dialysis catheter connection, disconnection, exit site care Secondary outcome: Adherence to recommended catheter care techniques, challenges faced when using ECC, patients’ knowledge level on catheter care |

QuantitativeQuasi-experimental studyThe ECC is developed by converting the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention's existing catheter checklist.Used to streamline the process used by dialysis facilities to perform checklists and audit and also incorporated educational resources for patients who can click for viewing.Education video contents included:

|

n = 108 patients (pre-pilot phase) n= not collected (post-pilot phase) n = 108 individual observations (pre-pilot phase) n = 954 individual observations using ECC (pilot phase) 7 haemodialysis facilities in United States Observers included staff familiar with the steps involved in catheter care (such as registered nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, physicians and dialysis technicians Patients included those on dialysis catheter and use the ECC tool |

|

| Neville et al. (2005) United Kingdom | Peritoneal Dialysis Training: A Multisensory Approach | Assess the quality of the new training program for patients with permanent learning disabilities and those with transient learning difficulties due to uraemia | QuantitativeQuasi Experimental studyQualitative analysis of the processes involved in training patients used the technique of theme identification.Quantitative analysis was undertaken of the length of time (in hours) spent on each type of intervention.Control: Traditional programmeAction plan to develop new training program:

|

n = 10 patients n = 5 patients in traditional group n = 5 patients in intervention group Patients with permanent learning disabilities and those with transient learning difficulties due to uraemia were recruited |

|

3.4. Data abstraction and synthesis

Findings from the included studies were organised systematically using the constant comparison approach (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005). In the initial data reduction process, key findings from the included studies were extracted and categorised into three main themes: (1) teaching strategies used for educating patients on haemodialysis catheter care (2) educational practices for educating patients on peritoneal dialysis catheter care and (3) outcomes of patient education on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care. The findings were further classified into subcategories based on the education approach and the evaluated outcome. A summary of the evaluated outcomes is displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Measured outcomes in the included studies.

| First Author (Year) | Educational practices for educating PD patients on tenckhoff catheter care | Teaching Strategies for educating HD patients on dialysis catheter care | Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) catheters | Tunnelled dialysis catheters | Peritonitis rates | Catheter related bloodstream infections (CRBSI) | Knowledge about haemodialysis (HD), vascular access | Not mentioned | |

| PD home training program | ✓ | |||||

| Theory and hands on training, use of written support, evaluation grid, audio support | ✓ | |||||

| Education pre-dialysis, Training, Home visits,re-training | ✓ | |||||

| Report card | ✓ | |||||

| Report card | ✓ | |||||

| Educational intervention program about HD | ✓ | |||||

| Didactic material, Verbal instruction | ✓ | |||||

| New peritoneal educational program | ✓ | |||||

| New peritoneal educational program, Objective Structured Assessment tool | ✓ | |||||

| Multifaceted intervention bundle which includes patient education at insertion, maintenance and removal | ✓ | |||||

| Instructional folder | ✓ | |||||

| Electronic catheter checklist incorporated with video for patient education | ✓ | |||||

| Multisensory training program | ✓ | |||||

4. Results

4.1. Study characteristics

This review included fourteen articles, six focused on patient education interventions for tunnelled (permanent) haemodialysis catheters and eight examined patient education interventions for peritoneal dialysis catheter care (Table 2). One study conducted a randomised controlled trial (Kotwal et al., 2022); three were quasi-experimental studies (Fadlalmola et al., 2020; Mokrzycki et al., 2021; Neville et al., 2005); five cohort studies (Bonnal et al., 2020; Cheetham et al., 2022; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Gadola et al., 2013, 2019); two cross-sectional studies (Bordin et al., 2007; Bernardini et al., 2006); two opinion papers (Dinwiddie, 2004; Dinwiddie et al., 2010) and one was a paper that developed and validated the education intervention for haemodialysis catheter care (Maia et al., 2019). As this study aimed to synthesise published evidence on educational interventions used to educate patients on haemodialysis catheter care, the study by Maia et al. (2019), which focused on creating and validating the educational material, was also included regardless of its methodological limitations.

The included articles originated from eleven countries: Australia (Kotwal et al., 2022), the United States (Mokrzycki et al., 2021), Saudi Arabia (Fadlalmola and Elkareem, 2020), France (Bonnal et al., 2020), South America (Gadola et al., 2013, 2019), North America (Dinwiddie, 2004; Dinwiddie et al., 2010), Brazil (Figueiredo et al., 2014; Maia et al., 2019), Italy (Bordin et al., 2007) and United Kingdom (Neville et al., 2005). In addition, Bernardini et al. (2006) and Cheetham et al. (2022) surveyed the current practices for peritoneal dialysis training programmes across multiple countries.

Only three (Fadlamola et al., 2020; Mokrzycki et al., 2021; Kotwal et al., 2022) out of the six studies reported on the setting of patient education for haemodialysis patients. They were either carried out at inpatient (Fadlamola et al., 2020) or outpatient haemodialysis facilities (Mokrzycki et al., 2021; Kotwal et al., 2022). Seven out of eight studies reported on the setting of patient education for peritoneal dialysis patients. Peritoneal dialysis training programmes were conducted in a combination of settings, such as inpatient settings and at outpatient peritoneal dialysis centre (Figueiredo et al., 2014; Bonnal et al., 2020), at both outpatient peritoneal dialysis centre and at home (Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013, 2019) or all three settings as mentioned above (Bernardini et al., 2006; Cheetham et al., 2022). The study by Neville et al. (2005) did not explicitly describe the setting of the peritoneal dialysis education programme.

4.2. Teaching strategies in the education for haemodialysis patients on haemodialysis catheter care and their outcomes

The two teaching strategies for haemodialysis patients were written materials and educational videos. Four studies used written materials to educate patients on how to care for their haemodialysis catheters including (i) report cards (Dinwiddie, 2004; Dinwiddie et al., 2010), (ii) patient education instructional folder (Maia et al., 2019) and (iii) the REDUCCTION (REDUcing the burden of dialysis Catheter ComplicaTIOns) catheter care sheet (Kotwal et al., 2022). Except for the instructional folder developed in the study by Maia et al. (2019), neither any tools nor a team of nephrology experts was employed to validate the report cards (Dinwiddie, 2004; Dinwiddie et al., 2010) and the REDUCCTION catheter care sheet (Kotwal et al., 2022). To keep track of the quality of the vascular access and the dialysis treatment, patients can bring the monthly vascular access report card suggested by Dinwiddie (2004) and Dinwiddie et al. (2010) to each dialysis sessions. This would help healthcare professionals better understand the state of the patient's vascular access and the progress of the dialysis treatment. The patient education instructional folder developed by Maia et al. (2019) informed patients about proper haemodialysis catheter care and its potential consequences with poor treatment. In Kotwal et al. (2022) study, the REDUCCTION catheter care sheet contained guidelines for vascular access management, information on hand hygiene, risks associated with catheter use, signs of infection, and advice on how to keep the catheter and exit site dry. Only one study utilised the educational video on haemodialysis catheter care (Mokrzycki et al., 2021). The educational video was integrated into the Electronic Catheter Checklist. The Electronic Catheter Checklist was primarily used to audit the staff members who performed the haemodialysis catheter care procedures. The educational video was also used to instruct patients on proper hand washing, preventing catheter-related bloodstream infections, and caring for haemodialysis catheters, while assisting staff in understanding the "best practice" procedures before conducting the audit. Apart from using written materials and educational videos, one study by Fadlamola et al. (2020) described the implementation of a haemodialysis educational intervention programme but did not specify the type of educational material employed.

Two studies (Fadlamola et al., 2020; Mokrzycki et al., 2021) explored the effectiveness of patient education in improving patients’ knowledge level on haemodialysis catheter care. There was, however, inconclusive evidence regarding the effectiveness of educational videos on patients’ knowledge level in Mokrzycki et al. (2021) study as post-pilot surveys could not be completed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, the haemodialysis education intervention programme implemented in the study of Fadlamola et al. (2020) revealed an overall increase in knowledge about the concept of haemodialysis catheters (p < 0.05). Nonetheless, the content and characteristics of the intervention programme were not described explicitly. Another study explored the impact of patient education in lowering catheter-related infectious complications amongst haemodialysis patients (Kotwal et al., 2022). However, the rate of haemodialysis catheter-related infectious complications did not reduce despite the use of the REDUCCTION catheter care sheet (Kotwal et al., 2022).

4.3. Teaching strategies in the education for peritoneal dialysis patients on peritoneal dialysis catheter care and their outcomes

All eight papers reported that patients received education on peritoneal dialysis catheter care via peritoneal dialysis education programmes (Neville et al., 2005; Bernardini et al., 2006; Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Gadola et al., 2019; Bonnal et al., 2020; Cheetham et al., 2022). They varied in terms of the composition and experience of the implementation care team members, training duration, timing relative to catheter placement, location, educational approach, educational material used, curriculum content, assessment method and follow-up support such as home visits or retraining sessions. Only seven studies (Neville et al., 2005; Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Gadola et al., 2019; Bonnal et al., 2020; Cheetham et al., 2022) examined the effects of different educational activities on peritonitis rates, and none examined the effect on the level of knowledge of peritoneal dialysis patients.

4.3.1. Composition and experience of the implementation care team

Most peritoneal dialysis education programs were led by a multidisciplinary team, but the team members differed. The multisensory peritoneal dialysis education program was led by peritoneal dialysis nurses, a speech and language therapist, and a media resources specialist responsible for acquiring and maintaining collateral material such as films, videos, and audiotapes (Neville et al., 2005). In contrast, the new multidisciplinary Peritoneal Dialysis Educational Programme in the study by Gadola et al. (2013) and Gadola et al. (2019) and the peritoneal dialysis education program by Bordin et al. (2007) was led by a multidisciplinary team of nurses, psychologist, social workers, dietitians, and nephrologists. Three other studies described the peritoneal dialysis education programs to be carried out by either general nurses or peritoneal dialysis-trained nurses (Bernardini et al., 2006; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Bonnal et al., 2020). Only one study reported that vendors from peritoneal dialysis companies were frequently involved in the delivery of training in addition to those already mentioned (Cheetham et al., 2022). Studies which compared the outcomes of peritonitis rates between trainers of different backgrounds (e.g., general nurse, peritoneal dialysis-trained nurse) indicated no significant differences (Bordin et al., 2007; Bonnal et al., 2020). On the contrary, training that was partly or wholly delivered by vendors from peritoneal dialysis companies was associated with a reduced risk of peritonitis compared with training by peritoneal dialysis nurses only (Cheetham et al., 2022).

4.3.2. Training duration and timing of education relative to peritoneal dialysis catheter placement

Most of the examined publications included the total average number of hours for training (Bernardini et al., 2006; Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Gadola et al., 2019; Bonnal et al., 2020; Cheetham et al., 2022). Four studies (Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Gadola et al., 2019) found comparable average training durations of 14 to 16 h, which is distinct from Cheetham et al. (2022) report of total training hours to be 16 to 30 h. Two studies did not state the training duration of the peritoneal dialysis programmes (Neville et al., 2005; Bonnal et al., 2020). Most peritoneal dialysis education was performed before catheter placement (Bordin et al., 2007; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Gadola et al., 2013, 2019; Bonnal et al., 2020). Bernardini et al. (2006) and Cheetham et al. (2022) studies were distinctive in that it examined the characteristics of the peritoneal dialysis training programs from different countries and concluded that most executed peritoneal dialysis training after catheter insertion. Only one study did not specify when peritoneal dialysis education was delivered in relation to catheter implantation (Neville et al., 2005).

Figueiredo et al. (2014) reported the total hours of training (particularly < 15 h) (p = 0.021) smaller centre size (p = 0.003) and timing of training in relation to peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion (immediate ten days after catheter insertion) (p = 0.011) were associated with a higher incidence of peritonitis. This was discovered to be different in other studies (Bernardini et al., 2006; Bordin et al., 2007; Cheetham et al., 2022), which revealed no significant association between peritonitis rates and training hours, time of peritoneal dialysis training relative to catheter placement and centre size.

4.3.3. Location of training

Peritoneal dialysis education was delivered in various settings, including hospitals, peritoneal dialysis centres, patients’ homes, and a combination of these. The proportion of peritoneal dialysis training programs in various countries was specifically compared in the two studies (Bernardini et al., 2006; Cheetham et al., 2022). The majority of training programs were delivered in hospitals/peritoneal dialysis centres, or a combination of both, along with training at home. Only a small proportion of the peritoneal dialysis programs were conducted solely at home. This was consistent with the findings of two studies that found training to be carried out in peritoneal dialysis centres (Figueiredo et al., 2014; Bonnal et al., 2020) and three other studies that found training to be carried out in both peritoneal dialysis centres and at home (Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013, 2019). The study by Neville et al. (2005) did not explicitly describe the setting of the peritoneal dialysis education programme. One study by Cheetham et al. (2022) discovered no correlation between training location and peritonitis rates and none of the studies explored how knowledge levels were affected by training location.

4.3.4. Educational approach

Only one study implemented the peritoneal dialysis education program using a multisensory approach (Neville et al., 2005). This approach is suited for patients with permanent and transient learning difficulties who exhibit symptoms including fatigue, muscle cramps, nausea, vomiting and itching from uraemia (Wulczyn et al., 2022). Two other studies developed and implemented the New Multidisciplinary Peritoneal Dialysis Educational Programme based on adult learning principles (Gadola et al., 2013, 2019). This allowed patients to review their learning whenever they were ready and at their own pace, encouraging self-directed learning (Sanchez and Cooknell, et al., 2017). The remaining five studies (Bernardini et al., 2006; Bordin et al., 2007; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Bonnal et al., 2020; Cheetham et al., 2022) did not specify their education model and approach used.

Neville et al. (2005) demonstrated that patients who participated in a peritoneal dialysis program based on a multisensory approach experienced lower incidences of peritonitis (0 episodes/patient-year vs 1 episode/patient-year; p < 0.05). The study also discovered that supervision and revision required less time during peritoneal dialysis exchange sessions, although no p-value was provided to quantify the significance of this finding. Other studies by Gadola et al. (2013) and Gadola et al. (2019) reported the peritoneal dialysis education program based on the adult-learning principles to be associated with a lower peritonitis rate (0.28 episodes/patient-year vs 0.55 episodes/patient-year with a previous peritoneal dialysis education program, p < 0.05).

4.3.5. Educational material used

Six of the eight studies that were included found varied peritoneal dialysis educational resources. Every study cited demonstrated the use of printed materials, such as books, brochures, posters (Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Gadola et al., 2019; Bonnal et al., 2020), step-by-step pictorial guide, wordings of assessment and daily record sheet (Neville et al., 2005). In three studies, a training apron with a peritoneal dialysis catheter was used as a simulated learning tool in addition to printed materials to practice peritoneal dialysis exchanges (Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013, 2019). The use of audiotape to support learning was demonstrated in two studies (Neville et al., 2005; Bonnal et al., 2020).

The effect of using several educational supports on the risk of peritonitis was only studied in the Bonnal et al. (2020) study. The use of written support (HR 1.44, 95 %CI 1.01–2.06) and starting education with hands-on training alone (HR 1.6, 95 %CI 1.04–2.46) or combined with theory (HR 1.34, 95 %CI 1.02–2.46) were associated with lower survival free of peritonitis. On the other hand, the use of an audio support (HR 0.55, 95 %CI 0.31–0.98) and starting of peritoneal dialysis training with hands-on-training in combination with theory (HR 0.57, 95 %CI 0.33–0.96) were associated with lower risk of presenting further episodes of peritonitis after the first episode.

4.3.6. Curriculum and method of assessment

Five of the eight papers revealed the curriculum of the various peritoneal dialysis programme (Table 4). All five studies taught proper dialysis bag exchange practices (Neville et al., 2005; Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Gadola et al., 2019). The curriculum content reported by Bordin et al. (2007), Gadola et al. (2013), and Gadola et al. (2019) were similar in the training content focusing on basic mechanisms of peritoneal dialysis, concepts of clean and sterile, hand washing, peritoneal solutions and supplies, bag exchanges, peritoneal dialysis adequacy and schedule, troubleshooting, nutrition and diet and pharmacological treatment. Formal peritoneal dialysis curriculum were employed in the remaining three studies (Bernardini et al., 2006; Bonnal et al., 2020; Cheetham et al., 2022), but they were not stated in detail.

Table 4.

Curriculum Details of PD Education Programme.

| Included Study | Curriculum |

|---|---|

| Bordin et al. (2007) | Anatomy and physiology of the kidney, PD definition, how PD works, recognizing the signs of infection, PD diet and exercise, principles of sterility in PD, proper handwashing techniques and bag exchange techniques, proper tenchoff catheter care, other essential skills such as administering recormon, drugs in bags |

| Gadola et al. (2019) | Definition and complications of CKD, types of renal replacement therapies, How PD works, principles of sterility in PD, proper handwashing techniques and bag exchange techniques, proper tenchoff catheter care, troubleshooting in PD, PD diet, exercise, common medications for CKD patients |

| Bernardini et al. (2006) | Developed by Gambro Healthcare and Baxter Healthcare, with guidance from an educational specialist Curriculum has not been published, nor is it available in the public domain. |

| Neville et al. (2005) | Proper PD Bag exchange |

| Bonnal et al., 2020) | Did not state the curriculum of the PD education programme |

| Figueiredo et al. (2014) | Did not state the curriculum of the PD education programme |

There were four methods of assessment: (1) questionnaire, (2) observation with the help of an interpretative scheme, (3) evaluation grid and (4) objective structured assessment inspired practical evaluation tool. A questionnaire was used to assess knowledge (Bordin et al., 2007), while observation accompanied by an interpretative scheme was used to assess patients’ skills (Bordin et al., 2007). The interpretative scheme directs the nurse trainer to assess patients' skill levels based on a set of shared assumptions, revealing some informality in the evaluation but identifying areas where teaching can be emphasised. The evaluation grid (Bonnal et al., 2020) is a typical list of items used to gauge patients' prior and subsequent peritoneal dialysis training-related knowledge and abilities. The objective structured assessment inspired practical evaluation tool (Gadola et al., 2013, 2019) was used to evaluate patients practical skills. The objective structured assessment consisted of 6 stations with 15 key steps scored at 10 points (5%) each, so any incorrectly performed or answered steps will be reflected in the final score. A satisfactory score was more than 95% correct answers. After an unacceptable score, retraining and testing will begin until a perfect score is obtained. As seen, patients were evaluated primarily based on their skills, which is consistent with a study by Cheetham et al. (2022), which found that procedural competency assessments were used in all peritoneal dialysis centres with little adoption of oral or written competency assessments. On the other hand, in both Neville et al. (2005) and Bernardini et al. (2006) studies, peritonitis rates were employed to evaluate learning.

The majority of the studies did not investigate how knowledge levels and peritonitis rates were influenced by different training curricula and assessment methods, with the exception of three studies (Gadola et al., 2013, 2019; Cheetham et al., 2022). While Cheetham et al. (2022) found no significant differences between the use of written/oral assessment compared to just procedural assessents, Gadola et al. (2013) and Gadola et al. (2019) demonstrated that peritoneal dialysis patients who completed the practical evaluation tool derived from the objective structured assessment program experienced significantly fewer cases of peritonitis (p < 0.05).

4.3.7. Follow-up support

Most peritoneal dialysis education programs in this review (n = 5) had some form of follow-up support (e.g., home visits and retraining) established even after the education program was completed. The use of home visits by nurses were reported in four studies (Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013, 2019; Cheetham et al., 2022). Four studies included retraining for patients and carers (Bernardini et al., 2006; Bordin et al., 2007; Gadola et al., 2013, 2019). In the study by Gadola et al. (2013) and Gadola et al. (2019), patients were required to attend a retraining session bi-annually. However, neither Bernardini et al. (2006) nor Bordin et al., 2007 mentioned the length of follow-up support. Two studies also included bi-annual workshops for patients to discuss their diet, physical exercise, and general wellbeing with their healthcare team (Gadola et al., 2013, 2019). Nonetheless, there were three studies which did not include follow-up support after patients had completed their education programme (Neville et al., 2005; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Bonnal et al., 2020).

Bordin et al. (2007) reported that the peritonitis rate was significantly lower (p < 0.05) in the centres that carry out home visits to identify any potential loss in knowledge or skill, compared to those centres that do not (0.34 episode/patient-year vs. 0.46 episode/patient-year). This result contrasts with that of the study by Cheetham et al. (2022), which found no association between the usage of home visits and peritonitis. None of the studies compared the impact of retraining sessions on peritonitis rates and investigated how knowledge levels and peritonitis rates were affected by retraining sessions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Teaching strategies for educating haemodialysis patients and outcomes measured

The variety of teaching materials employed could be attributed to the patients' diverse health literacy profiles and the importance of appropriate education approaches to cater to patients’ learning needs to achieve optimal learning outcomes (Paterick et al., 2017). Nonetheless, apart from the study by Mokrzycki et al. (2021) which used the education video embedded in the Electronic Catheter Checklist for patient education, there were no other studies included in the integrative review that explored the use of technology innovative patient education and their effectiveness on haemodialysis catheter care. Technology-based innovative patient education has been proved to have great potential for making patient education more engaging and interactive, leading to better information retention (Haleem et al., 2022). However, the use of technology-based education in patient education on haemodialysis catheter care has not been extensively investigated. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate this area and compare the effect of using conventional teaching strategies (e.g., printed materials) with technology-based patient education. Healthcare practitioners could discover gaps in patient education regarding haemodialysis catheters and ensure that patients receive accurate and valuable information. This could ultimately lead to better patient satisfaction, improved adherence to recommended guidelines and more efficient use of healthcare resources.

This review highlighted the importance of effective patient education for haemodialysis patients to improve their overall knowledge level. This is in line with a previous study's finding (Sousa et al., 2014), which demonstrated that patient education greatly boosted knowledge about dialysis access care. However, the written material – REDUCCTION catheter care sheet did not reduce catheter-related infectious complications amongst haemodialysis patients (Kotwal et al., 2022), which raised broader questions about the value of printed written materials and whether there are other avenues for improving the effectiveness of patient education delivery that educators can investigate. The effectiveness of the education video on catheter-related infectious complications was also not concluded due to the lack of post-pilot data (Mokrzycki et al., 2021). Therefore, future studies are needed to investigate the effectiveness of video-based education on catheter-related bloodstream infection rates amongst haemodialysis patients.

5.2. Educational practices used for educating peritoneal dialysis patients

Published patient education practices for peritoneal dialysis patients on peritoneal dialysis catheter care varied in terms of the composition and experience of members of the implementation care team, training duration, timing relative to catheter placement, location, educational approach, educational material used, curriculum content, assessment method and follow-up support. (Neville et al., 2005; Bernardini et al., 2006; Bordin et al., 2007; Figueiredo et al., 2014; Gadola et al., 2013, 2019; Bonnal et al., 2020). Results of this integrative review showed how several elements of an effective peritoneal dialysis education program might direct healthcare professionals toward creating an evidence-based peritoneal dialysis education program. In addition, it is necessary to pitch these education programs to the patient's health literacy level to allow for efficient attainment of knowledge and skill necessary for peritoneal dialysis catheter self-care.

5.2.1. Composition and experience of the implementation care team

This review compared the rates of peritonitis, in patients who received peritoneal dialysis education from general nurses versus peritoneal dialysis-trained nurses. Unfortunately, the studies included in this review did not provide the number of years of nursing experience in each centre, which could have been crucial in determining how it affected the risk of peritonitis. In theory, more experienced nurse trainers should provide more efficient training, demonstrate better communication and counselling skills, and be more sensitive to patients’ physiological and psychological challenges. On the other hand, Chow et al. (2007) discovered a negative relationship between the duration of a peritoneal dialysis trainer experience and peritonitis. As a result, a peritoneal dialysis-trained nurse with fewer years of experience might be more effective in teaching than an experienced general nurse. Further research is necessary to determine the association between risk of peritonitis and the nurse trainer competency for peritoneal dialysis centres keen on expanding the nursing training force from a general nursing pool. This is especially relevant in a setting of high general nursing workload.

5.2.2. Training duration and timing of education relative to peritoneal dialysis catheter placement

Inconsistent results were found in the studies on the effects of peritoneal dialysis education delivered prior to or following peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion on peritonitis rates. Additional studies are necessary to determine the appropriate timing to implement peritoneal dialysis education to reduce the risk of peritonitis due to poor technique.

5.2.3. Educational approach

The adoption of adult learning principles and a multisensory approach in peritoneal dialysis educational programs were found to be associated with a decreased risk of peritonitis. This outcome was consistent with past studies that demonstrated the efficacy of educational interventions created utilising the adult learning principles (Boyde et al., 2015; Kennedy and Parish, 2021). According to this theory, adults have distinct learning needs from children. Adults need to know the rationale of learning, prefers self-directed learning and autonomy in their study decisions. They use prior experience as a rich source of learning, and need to be prepared for learning (Niksadat et al., 2022). Adult learning-based peritoneal dialysis educational programs may be effective because adults are eager to learn and desire more autonomy, which motivates them to learn more. Also, research had shown that applying these principles consistently could increase the patient's willingness to follow advice given during patient education teaching (Van et al., 2015; Niksadat et al., 2022). The multisensory approach used in the peritoneal dialysis teaching program by Neville et al. (2005) study resulted in lower peritonitis rates. This might be due to the fact that the peritoneal dialysis training was provided using audiotaped verbal instructions and a step-by-step visual guide to the bag-exchange procedure, both of which suited the needs of patients in the study who exhibited permanent and temporary learning difficulties. As a result, healthcare professionals should consider the strategy that best suits the needs of each patient and may integrate more than one type of patient education approach.

5.2.4. Educational materials used

This review found that using written support increases the risk of peritonitis. The information materials intended for patients with chronic kidney disease have been shown to be written at a level above the average patient's literacy level (Morony et al., 2015). As a result, many patients do not take advantage of the written supports offered because they lack the knowledge necessary to comprehend them. Additionally, it was hypothesised that in some circumstances where health professionals may be occupied with other essential clinical duties, written support was therefore provided with fewer explanations and/or fewer efforts from the caring team to support the learning process, leading to less efficient patient education. Some patients might also find it challenging to learn theoretical and practical skills, so the peritoneal dialysis training programs should be customised for each patient. Prior studies had demonstrated a significant correlation between patients' educational background and their risk of developing peritonitis (Chern et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2017), which might be the reason why beginning education with hands-on training alone or in combination with theory was associated with a lower survival free of peritonitis.

Patients who received audio support for peritoneal dialysis training experienced fewer recurrences after a first peritonitis episode. Notably, the use of audio support was not widespread and only discussed in two studies (Neville et al., 2005; Bonnal et al., 2020). Therefore, the use of audio support might only be suitable for patients who have particular needs for auditory learning. This individualisation of the educational support could explain the better outcome. As a result, peritoneal dialysis training programs should include a variety of supports since there might not be a single support that is universally beneficial for peritoneal dialysis training in providing the best education for each patient. This review also found the use of hands-on-training in combination with theory to be associated with lower risk of presenting further episodes of peritonitis after the first episode. This could be explained by the fact that patients who gained knowledge of peritoneal dialysis through hands-on training were more assured in their capacity to take care of peritoneal dialysis catheters, which resulted in a less strict application of the rule of sepsis. They only begin to pay greater attention to the aseptic approach while handling the peritoneal dialysis catheter after the initial episode of peritonitis, which results in fewer incidences of repeated peritonitis.

5.2.5. Curriculum and method of assessment

Aside from the content and structure of the programme, the training timetable was also regarded as an important component of the training program (Kong et al., 2003). It featured specific components of the training program and completion datelines, which aided in motivating patients. According to Chow et al. (2007)'s retrospective study, patients who were late for scheduled training had an elevated risk of peritonitis. Unfortunately, none of the studies compared different training schedules covering the same topic and curriculum. The evaluation grid (Bonnal et al., 2020) and the objective structured assessment inspired practical evaluation tool (Gadola et al., 2013, 2019) were found to lower peritonitis rates which supported their use in evaluating the technical skills in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis.

5.2.6. Follow-up support

This review's findings on whether home visits lower peritonitis rates were inconsistent. Although it remains to be seen whether home visits are necessary to lower peritonitis incidence, this finding offered a starting point for the potential adoption of peritoneal dialysis training programs at home and more regular home visits. Additionally, there was no evidence found in this review to support the claim that retraining can reduce peritonitis rates. This needs to be considered as patients receiving peritoneal dialysis might be on the therapy for a long time that they grow acclimated to it and start using shortcuts (Chang et al., 2018). Retraining could act as a refresher in this case.

6. Limitations

As there was little experimental research on patient education for both haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care, this review included text and opinion articles (n = 2) and a validation study (n = 1) to expand on the quality of the findings. Readers are therefore required to interpret the review findings carefully. Furthermore, this review included studies that were of a retrospective and observational nature. Such study designs might contribute to potential bias due to uncontrollable confounding factors like patients’ sociodemographic data and possibly missing reports of catheter-related bloodstream infections and peritonitis. Moreover, only two studies were conducted in Asia, which limits the generalisability of the population and the lack of rigour of the study findings.

7. Recommendations for future research

The impact of educational videos on the knowledge of catheter care, catheter-related bloodstream infections and peritonitis rates in haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients could be further explored. This would be a useful discovery because the study by Mokrzycki et al. (2021) study, which intended to offer evidence of the educational video's usefulness, was inconclusive due to incomplete post-pilot surveys. In order to achieve optimal learning outcomes for haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis education, the findings would promote the use of educational videos as teaching tools. Furthermore, given that peritoneal dialysis patients also face infection risks, future research evaluating the impact of current patient education on the knowledge level amongst peritoneal dialysis patients is crucial. However, none of the included studies examined the relationship between patient education and the level of knowledge amongst peritoneal dialysis patients. Moreover, none of the studies discussed patient education for non-tunnelled (temporary) haemodialysis catheter care. This group of patients who are hospitalised should also be educated about their temporary haemodialysis catheter care because of risk for catheter infection and malfunction. Research into providing a practical educational resource for teaching non-tunnelled haemodialysis catheter care would be essential to mitigate the risk of catheter-related complications.

8. Recommendations for practice

Although there was insufficient evidence on the effectiveness of using videos to teach patients about haemodialysis catheter care, this may be taken into consideration if later studies demonstrate effectiveness in the improvement of patient knowledge and lowering catheter-related bloodstream infection rates in relation to haemodialysis catheters. It is also critical to recognise the advantages of written materials, and consider using them in conjunction with other teaching materials. A multisensory education approach is likely necessary, tailored to the individual patients' health literacy and background.

In this review, correlation was identified between peritonitis rates and training provider, training duration, training timing relative to catheter placement, training location, educational approach, educational material used, curriculum content, assessment method and follow-up support. Information gathered in this review may facilitate the formation of an effective patient education programme based on the evidence gathered to improve knowledge on peritoneal dialysis catheter care and reduce peritonitis rates.

9. Conclusion

Various patient education strategies were discussed in order to address the effectiveness of the strategies in promoting knowledge, reducing catheter-related mechanical problems and catheter-related infectious complications. However, there is still a paucity of research in this field of study and future studies are required to fill this vacuum. The importance of providing effective patient education on haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter care through a range of patient education strategies had been highlighted. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence regarding the effectiveness of written materials and educational videos in improving knowledge and reducing catheter-related mechanical and infectious complications, several elements of the teaching strategies in the education on peritoneal dialysis catheter care have been identified and discussed in this integrative review.

Funding

No external funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Felice Fangie Leong: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. Fazila Binte Abu Bakar Aloweni: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Jason Chon Jun Choo: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Siew Hoon Lim: Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- Béchade C., Guillouët S., Verger C., Ficheux M., Lanot A., Lobbedez T. Centre characteristics associated with the risk of peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: a hierarchical modelling approach based on the data of the French language peritoneal dialysis registry. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2017;32(6):1018–1023. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini J., Price V., Figueiredo A., Riemann A., Leung D. International survey of peritoneal dialysis training programs. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2006;26(6):658–663. doi: 10.1177/089686080602600609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnal H., Bechade C., Boyer A., Lobbedez T., Guillouët S., Verger C., Ficheux M., Lanot A. Effects of educational practices on the peritonitis risk in peritoneal dialysis: a retrospective cohort study with data from the French peritoneal dialysis registry (RDPLF) BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01867-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordin G., Casati M., Sicolo N., Zuccherato N., Eduati V. Patient education in peritoneal dialysis: an observational study in Italy. J. Ren. Care. 2007;33(4):165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2007.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyde M., Grenfell K., Brown R., Bannear S., Lollback N., Witt J., Aitken L. What have our patients learnt after being hospitalised for an acute myocardial infarction? Aust. Crit. Care. 2015;28(3):134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.H., Oh J., Park S.K., Lee J., Kim S.G., Kim S.J., Shin D.H., Hwang Y.H., Chung W., Kim H., Oh K.H. Frequent patient retraining at home reduces the risks of peritoneal dialysis-related infections: a randomised study. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):12919. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30785-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham M.S., Zhao J., McCullough K., Fuller D.S., Cho Y., Krishnasamy R., Boudville N., Figueiredo A.E., Ito Y., Kanjanabuch T., Perl J., Piraino B.M., Pisoni R.L., Szeto C.C., Teitelbaum I., Woodrow G., Johnson D.W. International peritoneal dialysis training practices and the risk of peritonitis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc. Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2022;37(5):937–949. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfab298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chern Y.B., Ho P.S., Kuo L.C., Chen J.B. Lower education level is a major risk factor for peritonitis incidence in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients: a retrospective cohort study with 12-year follow-up. Perit. Dial. Int.: J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2013;33(5):552–558. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2012.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow K.M., Szeto C.C., Law M.C., Fun Fung J.S., Kam-Tao Li P. Influence of peritoneal dialysis training nurses' experience on peritonitis rates. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN. 2007;2(4):647–652. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03981206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie L.C. Managing catheter dysfunction for better patient outcomes: a team approach. Nephrol. Nurs. J. J. Am. Nephrol. Nurses Assoc. 2004;31(6):653–662. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15686329/ Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie L.C., Bhola C. Hemodialysis catheter care: current recommendations for nursing practice in North America. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2010;37(5):507–521. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20973305/ 528Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadlalmola H.A., Elkareem E.M. Impact of an educational program on knowledge and quality of life among hemodialysis patients in Khartoum State. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2020;12 doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo A.E., de Moraes T.P., Bernardini J., Poli-de-Figueiredo C.E., Barretti P., Olandoski M., Pecoits-Filho R. Impact of patient training patterns on peritonitis rates in a large national cohort study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2014;30(1):137–142. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresenius Medical Care. (2014). Fresenius medical care annual report 2014 (pp. 1–254). (2014). (rep.). Retrieved from https://www.freseniusmedicalcare.com/fileadmin/data/com/pdf/Media_Center/Publications/Annual_Reports/FMC_AnnualReport_2014_en.pdf.

- Gadola L., Poggi C., Dominguez P., Poggio M.V., Lungo E., Cardozo C. Risk factors and prevention of peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2019;39(2):119–125. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2017.00287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadola L., Poggi C., Poggio M., Sáez L., Ferrari A., Romero J., Fumero S., Ghelfi G., Chifflet L., Borges P.L. Using a multidisciplinary training program to reduce peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit. Dial. Int. J. Int. Soc. Perit. Dial. 2013;33(1):38–45. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2011.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haleem A., Javaid M., Qadri M.A., Suman R. Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: a review. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022;3:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.susoc.2022.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M.B.B., Parish A.L. Educational theory and cognitive science: practical principles to improve patient education. Nurs. Clin. 2021;56(3):401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.J., Lee J., Park M., Kim Y., Lee H., Kim D.K., Joo K.W., Kim Y.S., Cho E.J., Ahn C., Oh K.H. Lower education level is a risk factor for peritonitis and technique failure but not a risk for overall mortality in peritoneal dialysis under comprehensive training system. PLoS One. 2017;(1):12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong I.L., Yip I.L., Mok G.W., Chan S.Y., Tang C.M., Wong S.W., Tong M.K. Setting up a continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis training program. Perit. Dial. Int. 2003;23(2):178–182. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17986543/ _supplRetrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotwal S., Cass A., Coggan S., Gray N.A., Jan S., McDonald S., Polkinghorne K.R., Rogers K., Talaulikar G., Di Tanna G.L., Gallagher M. Multifaceted intervention to reduce haemodialysis catheter related bloodstream infections: reducction stepped wedge, cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2022 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liyanage T., Ninomiya T., Jha V., Neal B., Patrice H.M., Okpechi I., Zhao M.H., Lv J., Garg A.X., Knight J., Rodgers A., Gallagher M., Kotwal S., Cass A., Perkovic V. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet (London, England) 2015;385(9981):1975–1982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Shi Y., Tao M., Jiang X., Wang Y., Zang X., Fang L., Jiang W., Du L., Jin D., Zhuang S., Liu N. Analysis of risk factors and outcome in peritoneal dialysis patients with early-onset peritonitis: a Multicentre, retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia S.F., Facundes D.M., Carneiro A.L. Patient self-care with double catheter lumen for hemodialization: validation of instructional folder. Acta Sci. Health Sci. 2019;41 doi: 10.4025/actascihealthsci.v41i1.47558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group* Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]