Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the effectiveness of the role of advanced nurse practitioners compared to physicians-led/ usual care (care managed by medical doctors or non-advanced nurse practitioners)

Background

Advanced nurse practitioners contribute to the improvement of quality patient care and have substantial potential to optimise the health of people globally. Since the formal recognition of advanced nurse practitioners by the International Council of Nurses, among others, the role has been adopted across most departments and clinical specialties, particularly in high-income countries.

Design

Systematic review of primary research evidence

Data Source

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane registry, Cochrane trials, and Cochrane EPOC (PDQ Evidence) were searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of patient care and health resource utilisation outcomes associated with advanced nurse practitioners.

Review Methods

The review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement. The chosen articles were restricted to full-text English language trials published in the last 20 years, incorporating comparators of usual care. Search terms were limited to variations of advanced nurse practitioner role and practice. The eligible studies were bias risk assessed and quality assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). Clinical and service outcomes were analysed using narrative synthesis as the marked heterogeneity between studies precluded meta-analysis.

Results

Thirteen RCTs were reviewed. All of them were conducted across high-income countries within primary care and hospital settings involving paediatric and adult patients. Five trials were assessed as high quality, and eight were of low to moderate quality. Positive effects were demonstrated for the impact of advanced nurse practitioners on usual care; for indigestion, mean difference [MD] 2.3: 95% CI 1.4, 3.1]), perceptions of health status [ (MD –140.6; 95% CI –184.8, –96.5)], satisfaction levels [ (MD ranged from –8.79; 95% CI –13.59, –3.98 to 0.61; 95% CI –4.84, 6.05)], physical function (1.58 [SD 0.76] v. 1.81 [SD 0.90]), and blood pressure control (systolic [133 [SD 21] v. 135 [SD 19] mmHg p = 0.04] and diastolic [77 [SD 10] v. 80 [SD 11] mmHg p = 0.007]) were looked at. Positive effects related to service provision included improved patient satisfaction and reductions in waiting times and costs, which significantly favored advanced nurse practitioners (all p < 0.05).

Conclusion

The evidence of this review supports the positive impact of advanced nurse practitioners on clinical and service-related outcomes: patient satisfaction, waiting times, control of chronic disease, and cost-effectiveness especially when directly compared to medical practitioner-led care and usual care practices - in primary, secondary and specialist care settings involving both adult and pediatric populations.

Keywords: Advanced nursing practice, Advanced nurse practitioner, Clinical impact, Service improvement, Care quality, Patient care

-

•

What is already known about this topic?

-

•

Previous randomized control trials and systematic reviews identify that nurse-led care (as a substitute for physician-led care) can improve overall patient care and service outcomes delivery.

-

•

Consistently reported positive outcomes include greater patient satisfaction, improved access to health advice, and better chronic disease self-management.

-

•

Previous reviews, of this nature, have focused on evaluating the impact of nurses working as substitutes for doctors in the primary care setting. This review differs in that it explores the role and capacity of Advanced Nurse Practitioners (ANPs) - in primary, secondary and specialist care settings involving both adult and pediatric populations.

-

•

Previous reviews focus on the study outcomes of specific nurse-led care interventions. This review evaluates studies that explore the comparable effect of advanced nurse practitioners-led care programes as they directly compare to physician-led/usual care programes.

-

•

This paper highlights the need for more high-quality randomized control trials design studies to further explore this clinical concept - given the notable existence of methodological flaws in the current research literature.

What this review paper adds?

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Advanced Nurse Practitioners (advanced nurse practitioners) are now a well-recognized subset of nurses who have acquired expert knowledge and advanced clinical skills. Since the formal acceptance and recognition of advanced nurse practitioners by the International Council of Nurses and other formal regulatory bodies and organizations, the role has been adopted by most departments and clinical specialties; particularly in high-income countries (81 countries classed as high-income countries [World Bank, 2019]) such as the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and the Netherlands (Scanlon et al., 2020). Advanced nurse practitioners have been perceived to benefit patient care and experiences while. At the same time reducing the workload of medical staff, and subsequently optimizing the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of health care services and improving overall patient satisfaction. Emerging evidence has revealed that advanced nurse practitioners can provide comparable levels of care and achieve similar outcomes as physicians (both junior and senior clinicians / medical doctors) and, in some cases, attain superior outcomes with regards to patient satisfaction, waiting times, control of chronic disease, and cost-effectiveness. Although this position has been supported by the International Council of Nurses, Carney (2014) highlights that defining the distinctive nature of advanced nursing practice, recognizing the key competencies and capabilities of advanced nurse practitioners, and exploring facilitative strategies in maintaining, implementing. and supporting the role of advanced nurse practitioners worldwide, is still incrementally developing and on-going studies are needed to map and monitor ANP progression. Given this context, this review aims to explore the impact of advanced nurse practitioners’ role and practice on nurse-led care – especially when aligned with other key health professional groups who have traditionally previously led this care.

Background

An advanced nurse practitioner has been formally defined by the International Council of Nurses as a nurse with professional registration, who has acquired additional expert or specialist knowledge, clinical skills, and complex decision-making capabilities and whose role varies in accordance with the contextual demand (ICN, 2002). In the UK, the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) has outlined the minimum standards for advanced nurse practitioners, which encompass a masters-level education in one of several core clinical or research areas through to the capacity of being able to independently prescribe medication (RCN, 2018) – competencies that are required of most advanced nurse practitioners at an international level. The role development of advanced nurse practitioners is usually congruent with the four defining pillars of advanced practice, which are clinical practice, leadership, education, and research, and reflect the level at which advanced nurse practitioners are able to operate (RCN, 2010).

Over recent years, up to 13 different titles have been used to denote advanced nursing practice: clinical nurse specialists (CNS), advanced practice nurse (APN), Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN), nurse consultant (NC), nurse endoscopist, nurse anaesthetist etc (Cooper et al., 2019). This has led to confusion related to role definition and structure – and exactly where such roles fit within the role of the medical disciplines (King et al., 2017). While CNS, APN, and NCs continue to play fundamental supportive roles in various medical disciplines, it is only in the last two decades that countries have observed an increasing utilisation of these advanced nurse practitioners (Delamaire and Lafortune, 2010).Notably, global health care services are currently experiencing unprecedented pressure, through the growing demands rising of rising population numbers, a rapidly ageing demographic, an increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, shortage of staffing among frontline health professionals, and financial austerity (Ham, 2017). Efforts to address these issues have included considerations around the advanced nurse practitioners’ role in adapting to and coping with such adversity and generating new initiatives to maintain and improve patient care practice (Baileff, 2015). Indeed, ANPs are now considered essential in meeting the complex care needs of patients and generating overall improvements in patient care quality and safety (Brook and Rushforth, 2011). Advanced nurse practitioners are also considered crucial in improving the cost effectiveness and efficiency of healthcare delivery and waste reduction, which may help achieve various government's efficiency savings target. For instance, such saving has been valued at £10 billion (NHS England, 2014). However, conducting research that can directly measure the impact (financial and otherwise) of advanced nurse practitioners in the healthcare arena as the variable that independently benefits patient outcomes is a methodological challenge. In a previous systematic review, Carter and Chochinov (2007) evaluated the impact of nurse practitioners (NP) on four key Emergency Department outcomes: cost, quality of care, satisfaction, and waiting times. After reviewing the primary evidence, the authors suggested that nurse practitioners reduced waiting times, promoted high patient satisfaction levels with care, and provided care that was equivalent to that of a senior medical doctor. No positive effect on cost was demonstrated, but this was compounded by insufficient data regarding the hiring of medical practitioners. In a later systematic review, Wilson et al. (2009) explored the clinical effectiveness of advanced nurse practitioners’ management of minor injuries among adults in the Emergency Department and found that there was no statistically significant difference demonstrated in comparison with the management provided by junior doctors. This review seeks to extend these previous review studies through adding further information related to the expansive roles and capacity of ANPs in both primary and secondary care settings between ANP- led care and physician led care and/or usual care.

The efficiency and impact of the greater utilization of the advanced nursing practice is recognized on an international scale, with advanced nurse practitioners being reported to exist in approximately 70% of all health care systems worldwide (Parker and Hill, 2017; Sheer and Wong, 2008). Given the international prevalence of advanced nurse practitioners, it has been observed that such nurses are contributing to current patient care and outcomes, driving improvements in hospital admission and readmission rates, and playing an instrumental role in reducing healthcare costs and improving efficiency within primary and secondary care settings (Parker and Hill, 2017). Table 6 identifies the current international advanced nursing practice context, set criteria, capabilities, and regulations by country of origin.

Table 6.

Existence of advanced nursing practice, set criteria, capabilities and its regulations by country of origin

| Country name | Existence of advanced practice nursing role: Y/N | RegulationY/N | LegislationY/N | Form of legislation/ regulatory bodies | Criteria of Advanced Nurse Practice | Roles and Capabilities | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Y | Y | Y | Health practitioner regulatory agency | Must possess core competencies and assist in indicating the scope of nursing practice | Autonomous practitioner Prescriber |

Austrian Nursing and Midwifery Council (ACNM 2009) https://www.anmac.org.au/standards-and-review/nurse-practitioner |

| Canada | Y | Y | Y | Provincial Responsibility | Pan-Canadian framework- core competencies to autonomously diagnose, order and interpret diagnostic tests, independent proscribing | Autonomous primary care practitioner role Limited prescribing rights |

Canadian Nurses Association, Nurses Practitioners’ Association of Ontario https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/nursing-practice/the-practice-of-nursing/advanced-nursing-practice |

| Denmark | N | N | N | Bachelor's degree in nursing regulated by Ministry of Education but advanced practice nurse role in development | Nurses specialists | Advanced nursing roles in nursing management, nursing education and public health nursing No prescribing rights |

Organisation of Economic, Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2012) and Danish Nurses Organisation, 2008) https://internationalapn.org/2014/06/29/denmark/ |

| France | N | N | N | Regulation of first level nurses is approved by the ministry of Health. Minimum qualification to advanced practice nurse has been master's level of education since 2010. |

advanced nurse practitioner role expansion is in its early stage of development | Uncertain role development Uncertain prescriptive authority |

French nursing organisation was initiated by a group of Advanced practice educated nurses in France in 2010. The French Nursing Council (2009) OECD (2006) (ICN 2008 a, b) https://internationalapn.org/2014/06/29/france/ |

| Finland | Y | N | N | Professional nursing regulated by law | Existence of registered nurse specialisation rather than advanced practice nurse role. The First advanced practice nurse graduated in 2006 |

Autonomous health care practitioner with a potentially wider scope of practice Limited prescribing authority |

https://internationalapn.org/category/europe/finland/ (Robinson and Griffiths, 2007) (Delamaire and Lafortune, 2010) |

| Germany | N | N | N | General nurse education regulated by The National Nursing Act and Ordnance of 1985 | Nationally defined professional competence and responsibilities of nurses Advanced practice nurse role will not be established in near future |

No advanced nurse practitioner role but specialist nursing role existed with no prescribing authority | OECD (2006) https://internationalapn.org/category/europe/germany/ (Sheer and Wong, 2008) |

| Hongkong | Y | Y | Y | The Nursing Council of Hongkong 1997- recognition of nurse specialist role and advanced practice nurse role | Clinical nurse specialists has been the birth of advanced practice nurse and nurse practitioners in the Hong Long health care system with greater acceptance in in-patient wards within acute hospital as well as outpatient nurse-led clinics but master's level of education has been as minimum requirement. | Varying autonomous practitioner Uncertain prescribing authority |

https://internationalapn.org/category/asia/hong-kong/ (Vernon and Jinks, 2013) |

| Ireland | Y | Y | Y | The Nurses and Midwives Act (2011) The Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland formerly known as An Bord Altranais |

The role is known as Registered Advanced Nurse Practitioner (Radvanced nurse practitioner for those master's degree has been a minimum requirement | Autonomous practitioner Certain treatment and prescribing authority |

https://internationalapn.org/category/europe/ireland/ (Delamaire and Lafontaine, 2010; Sheer and Wong, 2008). |

| Italy | N | N | N | Provincial College of Nursing | Role implementation is currently under development and may not be in the near future. No central control/ validation process for degree courses of nursing profession |

Role in development stages as well as treatment and prescribing |

https://internationalapn.org/category/europe/italy/ (OECD, 2006) |

| Japan | N | N | N | Japanese Nursing Association, JNA, 2006 | Two levels of nurse: registered nurse (First) & Licensed Practice Nurse (second level)-the latter is legislated by JNA- Nurse practitioner program is underway |

Role existed as practice nurse but no permitted to practise autonomously, nor treatment/ prescribing authority | https://internationalapn.org/category/asia/japan/ |

| Netherlands | Y | Y | Y | Specialist training programmes been recognised by both nursing associations and employers |

The role of advanced nurse practitioner/ APN is nurse practitioner in the Netherlands- requires a Master of Advanced Nursing Practice degree. Role introduced in 1997-predominantly incorporated within primary care |

Role existed as autonomous practitioner with treatment/ prescribing authority |

https://internationalapn.org/category/europe/netherlands/ (OECD, 2006) (Storedur and Leonard, 2010) |

| New Zealand | Y | Y | Y | Nursing Council of New Zealand Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act |

Advanced clinician role was initiated as nurse practitioner role, introduced in 2001-minimum requirement as master's degree for nurse practitioner scope of practice | Autonomous practitioner Certain treatment/ prescribing authority |

https://international.aadvanced nurse practitioner.org/Content/docs/New_Zealand.pdf |

| Norway | Y | Y | Y | Ministry of Education and Research | Master's degree as minimum entry to become nurse practitioner | Autonomous practitioner Varying treatment/ prescribing rights |

https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Item-2a-Nurses-advanced-roles-Maier-University-Technology.pdf |

| Singapore | Y | Y | Y | Singapore Nursing Board which maintains Advanced Practice Nurses Register | Role comprising Clinical Specialist Nurses and Nurse Practitioners | Variable autonomous practitioner Treatment authority permitted Prescribing right allowed under acute care protocols |

https://internationalapn.org/category/asia/singapore/ (Sheer and Wong, 2008; Tan Tock Seng Hospital, 2013). Singapore Nursing Board on https://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/snb |

| Spain | Y | Y | Y | General Council of Nursing Ministry of Education and Science |

Nurse practitioners Specialist Nurses Minimum requirement of master's degree |

Autonomous practitioner with treatment and prescribing authority | https://fhs.mcmaster.ca/globalhealthoffice/documents/AdvancedPracticeNurseinSpain.pdf |

| Sweden | Y | N | In development | National Board of Health and Welfare | Role existed as Nurse Specialists and Advanced Clinical Nurse specialists Master's degree |

Roles existed as advance clinical nurse specialists but not treatment/ prescribing rights nor autonomous practice |

https://internationalapn.org/category/europe/sweden/ (Lindblad, Hallman, Gillsjo, Lindblad, and Fagerstom, 2010). |

| Switzerland | Y |

N | N | Federal Level for all First level nurses | Role existence in Advanced Practice Nurse and Nurse anaesthetist Master's degree |

Role existed but no treatment/ prescribing authority nor autonomous practice |

https://internationalapn.org/2013/09/10/switzerland/ (Sprig, Schwendimann, Spichiger, Cignacco, and De Geest, 2009). |

| United Kingdom | Y | N | Emerging: Individual Health-care organisations Accredited through professional bodies |

Nursing and Midwifery Council Royal College of Nursing |

Role existence in Advanced Nurse Practitioner (advanced nurse practitioner) / Advanced Care Practitioners advanced nurse practitioner role greatly focused on Masters level of education |

Roles existed as advanced car/ clinical practitioner with prescribing authority – non -medical prescribing right Autonomous practitioner |

https://internationalapn.org/category/europe/united-kingdom/ (Morgan, 2010). (RCN, 2012) (Pulcini et al., 2009). |

| United States | Y | Y | Y | Licensed in all states and District of Columbia | Role existence in Nurse practitioners (NP), Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs), Clinical Nurse Specialists including nurse anaesthetists Role utilised in all health care settings |

Roles existed as APRN, with prescribing and treatment authority |

https://international.aadvanced nurse practitioner.org/Content/docs/USA.pdf The American Nurse Association - http://www.nursingworld.org The National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculty - https://nonpf.site-ym.com/ The American Association of Nurse Practitioners - https://www.aadvanced nurse practitioner.org/ |

Research aim

Given the above background and the increases in the number of published studies pertaining to the effectiveness of widely implemented advanced nurse practitioner roles in preliminary literature search, it was deemed appropriate to systematically review the most recent primary research evidence, particularly since this could be used to inform current advanced nursing practice, which does and will continue to play a critical role in meeting increasing population demands and managing rising patient complexity both nationally and internationally (Christensen et al., 2009). The uniqueness of this review is that it adds expansive roles and capacity of ANPs in both primary and secondary care settings between ANP- led care and physician led care and/or usual care. The care settings, in this review, were expanded to include further specialized disciplines/settings, such as intensive care, whereas studies such as the Laurant and colleagues (2018) Cochrane review focused specifically on primary care and was not exclusively ANP-specific. Furthermore, their study focused on nurse-led care outcomes alone (whilst discussing them against physician-led care) – whereas this review focuses on studies that directly compare ANP-led care to physician-led care. Therefore, this review sought to evaluate the effectiveness of advanced nursing practice on patient outcomes in comparison with other relevant healthcare practitioner providers. The main aim, of this review then, was:

-

•

To summarize and critically evaluate the evidence of how advanced nurse practitioners can best be utilized to help meet the growing complexity and demands of service-user populations in high-income nations, to further inform current advanced nursing practice by way of how and in what context the role of advanced nurse practitioners can maximally benefit patient care – related to ANPs in both primary and secondary care settings between ANP-led care and physician led care and/or usual care.

Method

This review of the primary literature pertaining to patient outcomes associated with the effectiveness of advanced nurse practitioners was performed against the Cochrane Collaborations criteria for producing credible reviews (Higgins and Thomas, 2018).

Search methods

A search for relevant primary studies was conducted using a series of bibliographic databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane registry, Cochrane trials, and Cochrane EPOC (PDQ Evidence) in April 2019. Studies were restricted to publication in the last two decades (2000–2019), which were subjected to peer-review and available in English. However, no restrictions were placed on the age of the research subjects, as this would allow for a broader capturing of the impact of advanced nurse practitioners. The final search terms were truncated where necessary and combined using Boolean logic. Grey literature was searched using key and unique terms: Advanced nursing practice, advanced nurse practitioner, clinical impact, resource utilisation outcomes, care quality, patient satisfaction, international and adherence in the research question was searched. Moreover, EThoS British Library and GreyNet were visited. The outcomes were based on an exploratory range of patient- and service-related measures of quality of care, in accordance with the fundamental standards of care of the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and the indicators of care quality defined by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (Care Quality Commission, 2019; NICE, 2019). Restricting the review to just RCT design studies was deemed necessary to facilitate the derivation of causal inferences between exposure to advanced nurse practitioners and reported outcomes, since RCTs represent the agreed standard for evaluating the effect of interventions by being able to control for a range of biases (Spieth et al., 2016; Whitehead, 2020). Exclusion criteria included studies of non-RCT design, studies published in a non-English language, and studies reporting data irrelevant to the ‘PICO’ framework (see Table 1).

Table 1.

PICO/ Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Research Design | RCTs | Observational studies, case-control studies, case reports, theses |

| Language | English | Non-English |

| Population | Paediatric and adult patients in primary care settings including care home, rehabilitation centre, specialist clinics. and acute care settings which include chest pain clinic, intensive care units, ambulatory care unit within acute care hospital | Patients from mental health institution Patients from mother and baby units |

| Intervention | Exposure to advanced nurse practitioner-led / advanced practice nurse-led intervention or service | Exposure to nurse-led interventions or services that lack advanced or specialist training |

| Comparator | Physician-led care (care provided by medical doctors) or usual care (care provided by medical doctors or non-advanced practice nurse) | Comparators comprising health professionals other than physicians |

| Outcomes | Resource utilization outcomes, health status, morbidity, mortality, quality of life, satisfaction, knowledge, adherence Preferences, length of stay Re-admission, re-attendance, need for admission, cost, other exploratory outcomes |

- |

Search outcomes

Following the acquisition of articles through database searching, the eligibility of the studies was determined by the development and application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 1) and complemented by the ‘PICO’ framework (Whitehead, 2020).

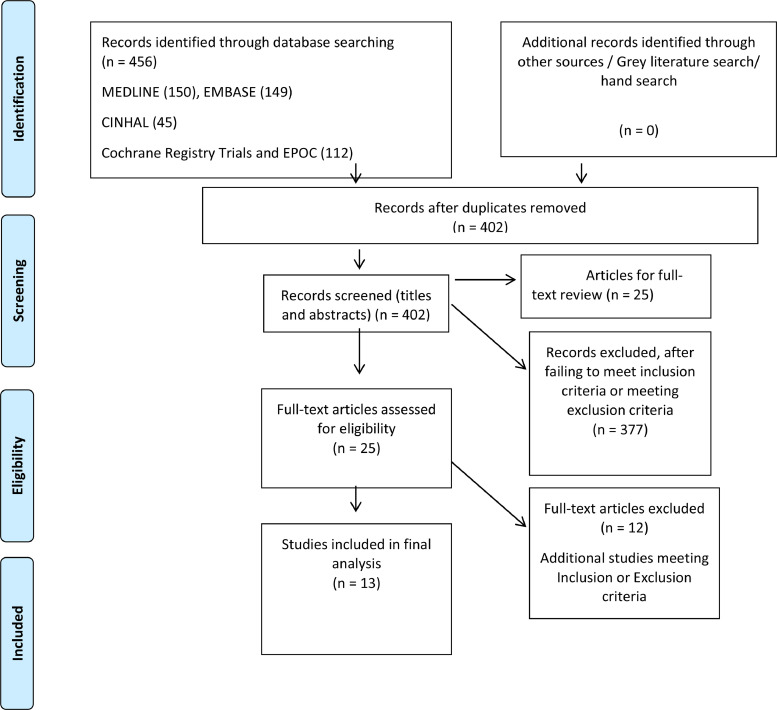

A total of 456 studies were identified through electronic database searching and, after the removal of duplicates, 402 were subjected to title and abstract screening. At this stage, the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria led to the exclusion of a further 377 studies, leaving 25 key sources for full-text review and appraisal. The appraisal process resulted in the identification of 12 more studies for exclusion. The reasons included the reporting of incongruent data, insufficient operational definition of an advanced nurse practitioner (N = 4), lack of effective comparison (N = 1), and insufficient training of nurses to meet the requirements of advanced nurse practitioners (N = 7). Consequently, 13 studies were deemed eligible for the final synthesis of results (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA chart showing the process leading to study eligibility.

Quality appraisal

In order to assess the risk of different biases in the included RCTs, Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Assessment Bias Tool for EPOC Reviews was used (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care, 2017) (see Table 2). Risk of bias was expressed in terms of internal and external validity. Internal validity included information on the reliability and completeness of the measurement as well as the ability of the study to control for potential confounding factors (Griffiths et al., 2018) (e.g., binding of outcomes assessment, incomplete outcomes data, and selective reporting). External validity was assessed primarily by considering the representative sampling of a center for a large region/country (Griffiths et al., 2018) (e.g., random sample of hospitals/countries) and reported sampling power. The complete quality appraisal checklist used in this literature review is available for access (see Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Synthesis of Risk Assessment of Included Studies

| Study | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Baseline characteristics | Baseline outcome measurement | Blinding of participants and staff (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Contamination | Bias due to insufficient power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan et al. (2009) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | |

| Dierick-van Daele et al. (2009) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | |

| Kamps et al. (2003) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | High | |

| Kinnersley et al. (2000) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Krichbaum (2007) | Low |

Low |

Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | High | High | |

| Kuethe et al. (2011) | Low |

Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | |

| Mundinger et al. (2000) | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | High | Low | |

| Ndosi et al. (2014) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | |

| Ryden et al. (2000) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low | Low | Unclear | |

| Stables et al. (2004) | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | |

| van Zuilen et al. (2011) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | |

| Venning et al. (2000) | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

| Williams et al. (2005) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | |

Data extraction

Data from eligible studies were extracted using proformas developed by the Cochrane Collaboration (2019), which provide a systematic structure for extracting data. The extracted data were then evaluated for amenability to meta-analysis and, if the degree of inter-study heterogeneity permitted, these were presented using standard Forest plots (Campbell, Machin, and Walters, 2007). However, marked heterogeneity was anticipated, and the review, therefore, contingently analyzed data using a descriptive or narrative-type approach, which could provide meaningful and information-rich findings to inform nursing practice (Thomas and Harden, 2008).

Synthesis

The majority of the studies were at a low or unclear risk of selection, confounding, and ascertainment biases, although a number of studies were deemed to be at high risk of attrition (Krichbaum, 2007; Mundinger et al., 2000; Ryden et al., 2000; Venning et al., 2000). This was where the rates of dropouts or loss to follow-up exceeded 15–20%. Two RCTs (Krichbaum, 2007; Mundinger et al., 2000) were also deemed at a high risk of contamination, as the advanced nurse practitioners’ intervention group also received input from the comparator of physician care. Finally, a number of studies were of high or unclear risk of bias resulting from insufficient statistical power (Dierick-van Daele et al., 2009; Kamps et al., 2003; Krichbaum, 2007; Ryden et al., 2000; van Zuilen et al., 2011; Venning et al., 2000), in turn, increasing the possibility of type II or false-positive errors (Kim, 2015) (see Table 2 for details).

Results

Included studies

A total of 13 international RCTs were included in this review (see Table 3). The countries of study origin were the United Kingdom (Chan et al., 2009; Kinnersley et al., 2000; Ndosi et al., 2014; Stables et al., 2004; Venning et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2005), the United States (Krichbaum, 2007; Mundinger et al., 2000; Ryden et al., 2000), and the Netherlands (Dierick-van Daele et al., 2009; Kamps et al., 2003; Kuethe et al., 2011; van Zuilen et al., 2011). The NPs as the intervention or exposure of interest were situated in a number of different care settings. These were primary care/general practices (Dierick-van Daele et al., 2009; Kinnersley et al., 2000; Venning et al., 2000), a cardiothoracic day-unit in a hospital setting (Stables et al., 2004), out-patient hospital clinics (Chan et al., 2009; Ndosi et al., 2014; Kamps et al., 2003; Kuethe et al., 2011; Mundinger et al., 2000; van Zuilen et al., 2011), and community-based care involving home-visits, nursing homes, and rehabilitation centres (Krichbaum, 2007; Ryden et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2005).

Table 3.

Included Studies, Study Characteristics, and Main Findings

| Study, setting, and number of centres | Participants | Intervention | Comparator | Follow-up duration | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chan et al. (2009) United Kingdom Multiple (unclear number) |

Patients with mild gastro-oesophageal reflux diseaseN = 175 |

Nurse Practitioner in Gastroenterology with one outpatient appointment | Care by usual General Practitioner | Six months | Significant symptom (dyspepsia) improvement was noted in the use of Glasgow Dyspepsia Severity Score (mean difference [MD] 2.3: 95% CI 1.4, 3.1) in the GNP group. Health status (140.6; 95% CI –184.8, –96.5) and cost of medication (£39.60; 95% CI 24.2, 55.1) were all in favour of the Nurse Practitioner group (p < 0.001) compared to the General Practitioner group. Although the baseline ulcers healing drug use was similar in both groups, 6 month-follow up reviews showed that the GNP group consumed less full-dose PPI medications (p < 0.0001) and more patients in the group required no treatment (p < 0.001). The study finds variable follow-up management of dyspepsia following gastroscopy, but this can be standardised by involving experienced GNP in the view of empowering patients for effective self-care. |

|

Dierick-van Daele et al. (2009) Netherlands 15 |

Patients with minor health problems (upper respiratory, ear and nose, musculoskeletal, skin, urinary, gynaecological and geriatric problems) N = 1501 |

Nurse Practitioner in Primary Care | General Practitioner-led care | Two weeks | Patients perceived of the high-quality care provided by both Nurse Practitioners and General Practitioners, but there were no significant between-group differences in relation to health status (MD 0.82 [SD 0.18] v. 0.80 [SD 0.18], medical resource consumption (composite of prescriptions administered, investigations performed, number of referrals, and invitation to return for review) and adherence to guidelines (79.8% v. 76.2%) (all p > 0.05). However, patients in the Nurse Practitioner group observed significantly longer and more follow-up consultations than those in the General Practitioner group (12.2 [SD 5.7] v. 9.2 [SD 4.8] min, p < 0.05). The study demonstrates the prolonged duration that the nurse practitioners spend on face-to-face consultation (12.2 min on average) in contrast to the GPs (9.20 min (SD 4.8, p < 0.001). Although NP consultation is slightly longer in comparison with GP consultation, it was noted that time in consultation mattered to patients. The study concluded that NPs provided positive and comparable quality of care to GP. The study indicates that there is potential for greater continuity of care while proposing a widespread national and international debate about appropriate skill mix in primary care and evaluate the value of NP role. |

|

Kamps et al. (2003) Netherlands 1 |

Paediatric patients newly referred from the Primary Care to an outpatient clinic N = 74 |

Clinical Nurse Specialist in Paediatric Asthma | Usual care delivered by Paediatrician | 12 months | No significant differences between groups were observed at 12 months for any of the reported outcomes in terms of percentage of symptom-free days (MD 2.5%; 95% CI –8.8, 13.8), airway hyper-responsiveness (MD 0.06%; 95% CI –0.19, 0.32), functional health status (MD 10.1%; 95% CI –0.3, 19.8), and quality of life (MD 0.08%; 95% CI –0.9, 0.7) (all p > 0.05). However, considerable improvements in the outcomes were observed among both groups at 12 months, with 26% of the children requiring a lower daily dose of inhaled corticosteroids compared to baseline (p = 0.03). Additionally, all parents in the NP group were satisfied with the asthma care they received. There were no emergency room visits or hospital admission in both groups during the study time. This could suggest improved asthma control. The study clearly signaled that in both primary and secondary care settings, asthma nurses can safely provide safe and comparable long term management of mild to moderate childhood asthma without compromising quality of care or control of disease. |

|

Kinnersley et al. (2000) United Kingdom Multiple (unclear number) |

Patients seeking a same-day consultation in General Practice. N = 1368 |

advanced nurse practitioner with a nurse practitioner diploma | General Practitioner care | Two weeks | Generally, patients in the Nurse Practitioner group were more satisfied with the care received, although not for all included primary care trusts (MD ranged from –8.79; 95% CI –13.59, –3.98 to 0.61; 95% CI –4.84, 6.05). There was no significant difference in the resolution of symptoms between groups (OR 0.32; 95% CI 0.23, 0.43), nor were the number of prescriptions issued OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.80, 1.28), investigations ordered (OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.58, 1.16), need for re-attendance (OR 0.91; 95% CI 0.70, 1.17), and referrals to secondary care (OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.58, 1.57) (all p > 0.05). Patients in the NP groups felt that they had received better communication i.e. information about their illnesses and causes. This could reduce chances of recurrence. A higher number of patients would consider future same day consultations with the nurse practitioners. The study findings highlight a wide acceptance of the role of nurse practitioners in the provision of care to patients requesting same day consultations. |

|

Krichbaum (2007) United States 2 |

Elderly patients discharged from hospital post hip fracture. N = 191 |

Nurse Practitioner in Gerontology | Usual care protocol | 12 months | The results at 12 months follow-up showed that the Nurse Practitioner group observed significant improvements in outcomes related to the need for physical assistance (1.58 [SD 0.76] v. 1.81 [SD 0.90]), mobility (1.24 [SD 0.34] v. 1.42 [SD 0.48]), personal care (1.41 [SD 0.53] v. 1.22 [SD 0.32]), and home chores (1.48 [SD 0.51] v. 1.44 [SD 0.19]), than compared to the comparator (all p < 0.05), although no differences were found for general health status, depression, or living situation (all p > 0.05). |

|

Kuethe et al. (2011) Netherlands 19 |

Paediatric patients with stable asthma N = 107 |

Clinical Nurse Specialist in Paediatric Asthma | General Practitioner-led care and care delivered by Paediatrician | Two years | The findings showed that there was a significantly lower number of review visits required among subjects assigned to the General Practitioner group (45.7%) than the Pediatrician group (87.9%) and Nurse Practitioner group (94.3%) at the two-year follow-up (p < 0.0005). However, the study suggests a low follow-up frequency does not detract from maintenance of good disease control in children with stable asthma. The MD between the Nurse Practitioner and the General Practitioner groups was 49.7% (95% CI 39.2, 92.7) and the MD between the Nurse Practitioner and the Pediatrician group was 6.0% (95% CI 0.1, 74.4). There were no significant differences between any of the groups regarding respiratory outcomes and unplanned patient visits, and it was also reported that Nurse Practitioners were able to provide care without consulting a Pediatrician. The specialized asthma nurse can safely provide comparable and equivalent long-term asthma management in both primary care and hospital care settings. The asthma nurse also improves the confidence of parents caring for asthmatic children leading to reduction in exacerbation, school absences and parental leave. The authors suggested that the findings in this study are applicable in secondary as well as in primary care, given that the same criteria of baseline characteristics are met. |

|

Mundinger et al. (2000) United States 5 |

Patients being followed up in primary care following an Emergency Department or urgent care visit. N = 1316 |

Nurse Practitioners in Primary Care | General Practitioner-led care | 12 months | No significant differences between groups were found for patients’ health status and indices of diabetes and asthma control (p > 0.05). However, patients with hypertension who were assigned to the Nurse Practitioner group observed a significantly lower diastolic blood pressure compared to those assigned to the General Practitioner group (p = 0.04). No other significant findings were observed for health resource utilization. There was no statistically significant difference in “overall patient satisfaction” or “patients’ mean ratings of satisfaction between the two groups. However, the provider attributes in terms of technical skills, communication skills and time spent with patients, the General Practitioners had significantly higher satisfaction ratings compared to Nurse Practitioners (p = 0.05). This finding may be attributable to the fact that the nurse practitioners were transferred to another new site after 2 years before recruitment and data collection were completed whereas the physician practices were not moved during the study period. |

|

Ndosi et al. (2014) United Kingdom 10 |

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis N = 181 |

Clinical Nurse Specialist in Rheumatology | Rheumatologist-led care | 12 months | Overall, the results showed that the mean change in Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) was significant for non-inferiority on both per-protocol and intention-to-treat analyses (–0.31; 95% CI –0.63, 0.02 and –0.15; 95% CI –0.45, 0.14 respectively). In addition, significant intention-to-treat non-inferiority was also found for pain (MD –1.34; 95% CI –7.13, 4.45, p = 0.004), physical functioning (MD 8.91; 95% CI –2.66, 20.5, p = 0.0113), satisfaction (MD –0.92; 95% CI –4.96, 3.12, p = 0.019), and consultation costs (£128; 95% CI –1263, 1006). The study finds that NLC had lower consultation cost and supports that NLC can provide safe and comparable care to manage RA patients. However, evidence on drawing probability of cost effectiveness was inconclusive due to varying disease specific activity and generic outcomes. |

|

Ryden et al. (2000) United States 3 |

Patients newly admitted to a resident nursing home. N = 319 |

Nurse Practitioner in Gerontology | Usual care | Six months | Patients assigned to the advanced nurse practitioner group observed significantly greater improvements in outcomes related to incontinence as well as fewer pressure ulcers and episodes of aggressive behavior and higher composite trajectory scores compared to usual care (p < 0.05). Moreover, patients with cognitive impairment were also found to observe a more stable effect, which was statistically significant in favor of the Nurse Practitioner group than the control group. The study suggests that the use of APNs in gerontology care incorporating scientifically based protocols into every day practice was encouraging: improvement in level of continence, pressure ulcer care, enhanced progress of mental health wellbeing among the elders. |

|

Stables et al. (2004) United Kingdom 1 |

Patients requiring day-case cardiac catheterisation. N = 339 |

Nurse Practitioner in Cardiothoracic Surgery | Care by junior medical staff | Unclear, but less than one year | There were no significant differences between the groups with regards to major adverse events and the Cardiologists’ acceptance of the patients’ preparation was high for both groups (98.3% and 98.8%). However, patients’ level of satisfaction was significantly greater among those assigned to the Nurse Practitioner (NP) group (p = 0.04) compared to group of Junior Medical Staff (JMS). In addition, the time taken in the clinic visit was lower in the NP group than for JMS group (p = 0.01). The overall event rate including minor adverse clinical events was 4/175 (2.3%) in NP group and 1/161 (0.6%) in JMS group. The calculated absolute risk difference = +1.7%, the upper boundary of the one-sided 95% CI = 6.2%. The study reveals NP role recognition and acceptance among junior medical staff who recommend the NP role should be continued. The study concludes that NPs with appropriate training, education, and support can safely prepare patients for elective cardiac catheterisation. |

|

van Zuilen et al. (2011) Netherlands 9 |

Patients with diagnosed chronic kidney disease. N = 788 |

Nurse Practitioner | Usual care by Physician | Five years (median) | At the two-year follow-up, the Nurse Practitioner group had significantly lower systolic (133 [SD 21] v. 135 [SD 19] mmHg p = 0.04) and diastolic blood pressures (77 [SD 10] v. 80 [SD 11] mmHg p = 0.007), LDL cholesterol (2.45 [SD 0.81] v. 2.30 [SD 0.75] mmol/L p = 0.03), and a higher but non-significant use of ACE inhibitors, statins, aspirin, and vitamin D compared to the controls (p > 0.05). Subjects assigned to the Nurse Practitioner group also had no significant improvements in smoking cessation, weight, physical activity levels, or sodium excretion (p > 0.05). |

|

Venning et al. (2000) United Kingdom 20 |

Patients requesting same-day appointment in Primary Care. N = 1316 |

Nurse Practitioner | General Practitioner | Two weeks | Nurse Practitioner consultation times were significantly longer (MD 4.2 minutes; 95% CI = 2.98, 5.41), the number of tests ordered were significantly higher (MD 8.7% v. 5.6%; 95% CI 1.04, 2.66), patients were asked to return for review more frequently (MD 37.2% v. 24.8%; 95% CI = 1.36, 2.73), and costs were lower (MD £2.33; 95% CI = 1.62, 6.28) compared to General Practitioners (all p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed between the groups for health status, prescribing patterns, or health service costs (p > 0.05). However, patients were generally more satisfied with Nurse Practitioner consultations, with an adjusted mean difference of 0.18 (95% CI = 0.092, 0.257), but this was not significant (p > 0.05). |

|

Williams et al. (2005) United Kingdom Multiple (unclear number) |

Patients with frequent urinary incontinence that affects their quality of life. N = 3748 |

Nurse Practitioner for Incontinence | Usual General Practitioner-led care and local continence advisory services | Six months | At the three-month follow-up, a significantly higher number of patients in the Nurse Practitioner group found that their incontinence episodes had improved compared to the controls (59% v. 48%, MD 11%; 95% CI 7, 16, p < 0.001). Moreover, a significantly higher proportion of subjects in the Nurse Practitioner group reported that their urinary symptoms had completely resolved compared to the controls (25% v. 15%, MD 10%; 95% CI 6,13, p = 0.001). The associated quality of life between the two groups (74% v. 68%, MD 6%, 95% CI = 2, 10, p = 0.003), patient satisfaction rate with the service provision (52% v. 45%, MD 7%, 95% CI = 3, 12, p = 0.001). These effects were maintained at the six-month follow-up. The study finds that the continence nurse practitioner-led service is both feasible and directly applicable for a wider implementation of continence service which is effective in symptoms reduction associated with incontinence, urinary frequency, urinary urgency and nocturia. |

Participants and nursing intervention

Two studies included paediatric patients requiring management of asthma (Kamps et al., 2003; Kuethe et al., 2011), whilst the majority included adults aged more than 18 years. Three studies restricted the population to older persons aged 60 years and above, with problems related to urinary incontinence (Williams et al., 2005), management following a hip fracture (Krichbaum, 2007), and multiple comorbidities or complex problems necessitating nursing home admissions (Ryden et al., 2000). In three studies, the NP acted as the first contact of care and managed the ongoing care (Mundinger et al., 2000; Kamps et al., 2003; Ryden et al., 2000). In four studies, the NP was the principal contact for patients seeking same-day or urgent consultations (Dierick-van Daele et al., 2009; Venning et al., 2000; Kinnersley et al., 2000; Stables et al., 2004). Five studies identified that the NP was responsible for the management or follow-up of patients with chronic disease (Chan et al., 2009; Ndosi et al., 2014; Kuethe et al., 2011; van Zuilen et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2005), while one study confirmed that the NP was responsible for co-ordinating and supporting post-acute care (Krichbaum, 2007).

Quality assessment of included studies

Use of GRADE criteria

Following the methodological quality assessment of the included studies, the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) criteria, which is the most widely used and validated transparency framework, was applied for quality assessment of reproducibility, applicability, and generalzability of the included study findings. The GRADE criteria assisted by developing and presenting summaries of evidence in order to determine the methodological quality of the included studies (Guyatt et al., 2011). The rating of quality, using the GRADE criteria, is based on study design and the presence and/or degree of different biases and other factors, where the overall quality is subjectively determined to be very low, low, moderate, or high (Guyatt et al., 2011). In addition to the risk of bias, the downgrading of research quality is informed by other factors such as imprecision in confidence intervals, inconsistency in comparison with other reports and influence of heterogeneity, indirectness in applicability of outcomes to the target population, and publication bias regarding inferences about missing data. Alternatively, the quality of research can be upgraded in the presence of large effects, dose-response effects, and reduction of the effect when accounting for residual confounders (Siemieniuk and Guyatt, 2019).

Based on the GRADE criteria, five studies (Chan et al., 2009; Kinnersley et al., 2000; Kuethe et al., 2011; Stables et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2005) were considered to be of high quality, with minimal risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, and indirectness. Three of these studies were upgraded due to the reporting of large effect sizes (Chan et al., 2009; Kuethe et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2005). The remaining studies were of moderate quality (Dierick-van Daele et al., 2009; Ndosi et al., 2014; Ryden et al., 2000; van Zuilen et al., 2011) and low quality (Kamps et al., 2003; Mundinger et al., 2000; Venning et al., 2000). One study (Krichbaum, 2007) was deemed to be very low in its methodological quality due to the high number of biases and evidence of indirectness (see Table 4).

Table 4.

GRADE Evidence Profile of Included Studies

| Study | Number of biases for downgrading | Publication bias | Indirectness of evidence | Imprecision of confidence intervals | Inconsistency with other trials | Reasons for quality upgrading | Overall quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan et al. (2009) | One | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Large Effect Size | High |

| Dierick-van Daele et al. (2009) | Two | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Moderate |

|

Kamps et al. (2003) |

Three | Undetected | Undetected | Some imprecision | Undetected | Undetected | Low |

| Kinnersley et al. (2000) | One | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | High |

| Krichbaum (2007) | Four | Undetected | Detected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Very Low |

| Kuethe et al. (2011) | One | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Large Effect Size | High |

| Mundinger et al. (2000) | Three | Undetected | Detected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Low |

| Ndosi et al. (2014) | One | Undetected | Undetected | Some imprecision | Undetected | Undetected | Moderate |

| Ryden et al. (2000) | Three | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Large Effect Size | Moderate |

| Stables et al. (2004) | One | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | High |

| van Zuilen et al. (2011) | Two | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Moderate |

| Venning et al. (2000) | Three | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Low |

| Williams et al. (2005) | One | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Undetected | Large Effect Size | High |

Excluded studies

A total of 12 studies were excluded from this review after full-text scrutiny (see Table 5). They did not meet the inclusion criteria for the study selection: either poorly defined the level of training of the nurses and their role or additional education and training carried out by the nurse but to a degree that was inconsistent with formal or operational definition of an advanced nurse practitioner.

Table 5.

Excluded Studies

| Study | Reason for Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Barrett et al. (2011) | Insufficient definition of the nurse intervention |

| Campbell et al. (2015) | Insufficient training of nurses to meet definition of advanced nurse practitioner – practice nurses |

| Houweling et al. (2011) | Insufficient training of nurses to meet definition of advanced nurse practitioner – practice nurses |

| Huber et al. (2017) | Insufficient definition of the nurse intervention |

| Iglesias et al. (2013) | Insufficient definition of the nurse intervention |

| Larsson et al. (2014) | Insufficient training of nurses to meet definition of advanced nurse practitioner – nurses with extensive experience in the field of rheumatology |

| Moher et al. (2001) | Insufficient training of nurses to meet definition of advanced nurse practitioner – practice nurses |

| Ogren et al. (2018) | Insufficient definition of the nurse intervention |

| Sanne et al. (2010) | Insufficient training of nurses to meet definition of advanced nurse practitioner – nurses with some extra training |

| Scherpbier-de Haan et al. (2013) | No effective comparison – crossover of shared nurse/physician care |

| Shum et al. (2000) | Insufficient training of nurses to meet definition of advanced nurse practitioner – practice nurses |

| Voogdt-Pruis et al. (2010) | Insufficient training of nurses to meet definition of advanced nurse practitioner – practice nurses |

Discussion

The studies, included in this review reported a diverse range of outcomes associated with the utilization of advanced nursing practice, with positive benefits observed in relation to the management of dyspepsia (Chan et al., 2009), medication costs and requirements (Chan et al., 2009; Kamps et al., 2003), health status (Chan et al., 2009), patient satisfaction levels (Stables et al., 2004; Venning et al., 2000; Kinnersley et al., 2000), duration of time spent in outpatient clinics (Stables et al., 2004), physical functioning (Krichbaum, 2007), blood pressure levels (van Zuilen et al., 2011; Mundinger et al., 2000), frequency of urinary symptoms (Williams et al., 2005), severity of rheumatoid arthritis symptoms and related costs (Ndosi et al., 2014), frequency of incontinence, pressure ulceration, and aggressive behavior (Ryden et al., 2000).

Advanced nurse practitioners demonstrated greater adherence to recommended targets and practical guidelines. The central themes reported are reflective of the number of diverse ways in which advanced nurse practitioners are currently employed in clinical practice, in settings that vary from long-term nursing home facilities to inpatient clinics. Overall, 13 RCTs were eligible for this review, with almost all trials reporting that care from advanced nurse practitioners led to positive effects on patient care and service outcomes, including symptom severity (Chan et al., 2009; van Zuilen et al., 2011; Mundinger et al., 2000; Williams et al., 2005; Ndosi et al., 2014; Ryden et al., 2000), physical function (Krichbaum, 2007), satisfaction (Stables et al., 2004; Venning et al., 2000; Kinnersley et al., 2000), waiting times (Stables et al., 2004), and costs (Chan et al., 2009; Kamps et al., 2003; Ndosi et al., 2014). No studies were found that explored the impact of advanced nurse practitioner/NP on staff experiences and job satisfaction, although Krichbaum et al. (2007) acknowledged that gerontological APRNs have effective links between current scientific knowledge and nursing home staff. A small number of studies support the positive impacts of collaborative care by advanced nurse practitioners and medical doctors. These studies were mostly conducted within critical care settings where the technical skills of advanced nurse practitioners are similar to those of their medical counterparts, i.e., performing blood gas sampling via the arterial line and analysing its result.

Several other studies were also found to have investigated the impact of nurse-led care on similar outcomes, with most being conducted in primary care settings. For example, in a multi-centered randomized controlled trial, Shum et al. (2000) assessed the acceptability and safety of a minor ailment service in general practice between trained nurses and physicians. They found that patients were more satisfied with the care received from nurses compared to that provided by doctors (p < 0.05). In another primary care-based trial, Moher et al. (2001) evaluated the effectiveness of a nurse-led service compared to general practitioner-led service in promoting secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in a cohort of older adults. The results demonstrated that the assessment of blood pressure, cholesterol, and smoking status was more frequent in patients assigned to the nurse group, although clinical outcomes related to these measures were comparable between groups at the study conclusion. Furthermore, Sanne et al. (2010) explored the impact of ‘nurse versus doctor-led’ management of anti-retroviral therapy care for patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Their results identified that both groups observed comparable outcomes related to treatment failure (48% v. 44%), mortality (10% v. 11%), virological failure (44% v. 39%), adverse effect failure (68% v. 66%), and program losses (70% v. 63%), which were all significantly non-inferior. Notably, these trials were excluded from their review, as the definition of the nurse intervention was not congruent with that of advanced nurse practitioners. A range of previous studies also assessed the effect of nurse-led care. They found that their input could provide safe care, markedly reduced the workload of general practitioners, and promoted a more rapid access to clinical advice and clinical care (Lattimer et al., 1998; Lewis and Resnik, 1967; Chambers and West, 1978).

The results of this systematic review are also congruent with a relatively recent Cochrane review, where Laurant et al. (2018) investigated the impact of nurses as substitutes for primary care physicians on patient outcomes, care processes, and resource utilization. Their study evaluated a total of 18 RCTs, including several studies in this review; however, they also analyzed outcomes from interventions comprising across a range of advanced and non-advanced practice nurses – rather than a focus on just advanced nurse practitioners. The results demonstrated a moderate quality evidence to suggest that nurses positively improved patient satisfaction levels and clinical or health status indicators, such as blood pressure. However other outcomes, such as patient satisfaction and mortality, highlighted a lower degree of certainty and evidence compared to this study. The authors could only conclude that there is some evidence that nurses probably provide equal or even superior care to that of doctors for a range of minor and urgent illnesses and chronic conditions. In a preceding systematic review, Laurant et al. (2005) confirmed that trained nurses could safely deliver care and achieve outcomes that were non-inferior to that of doctors, although the review included studies with a range of methodological flaws and a limited duration of patient follow-up. Numerous other reviews have supported and considered advanced nurse practitioners as professionals who can deliver equal and even, at times, superior care than physicians. For example, Swan et al. (2015) conducted a systematic review of 10 randomized trials comprising over 10,000 patients, in order to investigate the safety and efficacy of advanced nurse practitioners in the provision of acute care. The follow-up period ranged from one to two years and, notably, advanced nurse practitioners conferred an equal or improved outcome benefit upon a range of physiological measures, service costs, and patient satisfaction levels in contrast to patients receiving physician-only care. In another systematic review of advanced practice nurses, outcomes, among studies published within an 18-year period, Newhouse et al. (2011) found that, in acute clinical settings, advanced nurse practitioners were associated with reductions in length of hospital stay and healthcare costs. However, in a systematic review of the effect of nurse-led and physician-led care for patients with chronic diseases, Martinez-Gonzalez et al. (2015) discovered that there were no significant or meaningful differences between the intervention groups and only 40% of patients preferred nurse-led care. Indeed, this finding is congruent with this review, where a number of studies (Dierick-van Daele et al., 2009; Kamps et al., 2003; Kinnersley et al., 2000; Mundinger et al., 2000) reported non-significant outcomes related to clinical and service-related measures of care quality.

With regard to specific settings, in a systematic review of 15 studies comprising 23681 participants, Woo et al. (2017) evaluated the impact of advanced nurse practitioners on quality of care, clinical outcomes, satisfaction, and cost within emergency and critical care environments. In the Emergency Department setting, the authors found mixed results with regards to the duration of stay, waiting time, patient satisfaction, mortality, cost, and greater adherence of advanced nurse practitioners to the recommended targets of administering analgesia. Two out of the fifteen studies reported a significant reduction in waiting time in the Emergency Departments, but this was confounded by doctors being responsible for patients with greater acuity and complexity of illness, whilst other studies demonstrated no difference between nurses’ and physicians’ associated length of stay and waiting time for treatment. The positive impact of advanced nurse practitioners on waiting times was less marked, with only the study by Colligan et al. (2011) demonstrating that patients with minor injuries endured a 14 min median shorter waiting time compared to the time that would have been taken on being managed by an emergency medical doctor. Meanwhile, other studies demonstrated that waiting times were equal between groups of advanced nurse practitioners and physicians working in the same setting. With regards to the critical care setting, 7 out of the 15 studies used comparative designs, with one evaluating direct management of patient care delivered by advanced nurse practitioners and others analyzing the impact of collaborative advanced nurse practitioner and physician-led care. The length of stay was found to be largely similar between direct care by advanced nurse practitioners and usual/physician-led care. Although one study (Landsperger et al., 2016) showed that patients had significantly lower odds (13%) of a longer stay, this was associated with a higher patient-to-nurse ratio. Nonetheless, it may imply that directed care provided by advanced nurse practitioners may be more efficient than conventional physician-managed care. Interestingly, the time of stroke treatment was found to be significantly lower when on-site care was provided by advanced nurse practitioners and when these nurses were available 24/7 (p < 0.001) as compared to the usual service model that was managed by physicians (Moran et al., 2016). However, this merely reflects better availability of stroke intervention measures such as thrombolysis rather than highlighting advanced nurse practitioners as the independent beneficial factor for this service outcome measure (Moran et al., 2016).

The collaboration of advanced nurse practitioners and physicians was also found to have positive effects on mortality in intensive care units, with significantly lower mortality rates compared to physician-only care (6.3% v. 11.6%, p = 0.01). However, general in-hospital mortality was comparable between groups (p = 0.11) (Skinner et al., 2013; Scherzer et al., 2016). However, the findings of the identified studies, which relied on propensity scoring, are likely to have missed important confounders, thus limiting the reliability of the results. Patient satisfaction levels were comparable between advanced nurse practitioners and physicians, with cost-effective analyses being generally similar between the advanced nurse practitioners–physician collaborative and physician-only models. However, only two studies (Skinner et al., 2013; Hiza et al., 2015) identified results that demonstrated cost saving comparison between NP-physician groups and physician-only groups. Skinner et al. (2013) suggested that annual staffing costs of more than £170,000 could be saved if advanced nurse practitioners were employed to manage intensive care unit patients.

While this review and previous studies have reported a variety of beneficial effects from the widespread utilization of advanced nursing practice, the findings are limited by the challenges associated with conducting comparative studies among different health professionals and the inability to account for non-interventional factors and extraneous influences such as physical activity, dietary habits, and the occupational stress of these professionals. This could clearly have confounded the outcome effects (Laurant et al., 2018). Considering the findings, a number of implications and recommendations have been identified for nursing practice and future research. These need to be interpreted in light of the study's limitations.

Limitations

Firstly, the limitations of this systematic review mostly involve the inclusion and exclusion criteria that have been used to define study eligibility. In this regard, while efforts were sought to reduce the risk of reporting-type bias (that is, the avoidance of excluding relevant studies for addressing the research question), there is always a risk that important studies may be missed from the database indexing processes. Second, studies had to be restricted to the English language due to limited investigator resources, which may have excluded important and relevant studies conducted in non-English speaking countries as well as some other high-income countries and low-to-middle income countries. Indeed, the exclusion of grey literature and non-English studies could have excluded pertinent articles from collective evaluation, although this was not deemed overall a negatively impactful risk – as this is commonplace with systematic reviews. Thirdly, the credibility of the findings in this review are inherently linked to and limited by the methodological quality of informing RCTs, which was on average moderate at best, with some trials comprising a high number of biases and having detectable inconsistencies and statistical imprecision.

Implications for practice

As the majority of studies have supported advanced nurse practitioners as providers of non-inferior care and outcomes compared to physicians/ doctors-led care and usual care, they pose several implications for practice. These include: the incorporation of advanced nurse practitioners into various clinical settings is both feasible and required to help alleviate the burden placed upon physicians and reduce waiting times for patients; the study findings also extend to implications related to the cost of healthcare and service provisions, as it appears that advanced nurse practitioners may help reduce costs and improve efficiency in the health care system; wider benefit for patient flow, with advantages in terms of higher patient throughput among acute admitting departments and more timely discharge of patients from general medical/surgical wards; and subsequently, inclusion of advanced nurse practitioners can lead to reducing diagnosis and treatment delays and alleviating the risks associated with protracted hospital stays, such as nosocomial infections and venous thromboembolism.

In the interim, since the current literature is predominately of moderate quality, additional RCTs are required to further evaluate the clinical impact of extensive utilization of advanced nurse practitioner role. However, this may prove challenging as a number of biased studies from the past already exist. Future research should not only re-explore the clinical impact of advanced nurse practitioners using RCT design, but also attempt to enhance the methodological quality of the trials by accounting for residual confounders and minimizing the risk of other biases that were identified in this review.

Conclusion

This systematic review has found that advanced nurse practitioners enhance patient care, service cost-effectiveness, efficiency, and general patient satisfaction with the overall quality of care provided. Studies evaluating the impact of advanced nurse practitioners on clinical and service outcomes appear to be generalizable to all health settings, supporting the diverse capability of this professional discipline in addressing current and future health care needs of patients and their families. Despite that the findings are somewhat limited by methodological issues informing trials, it is apparent that advanced nurse practitioners offer a promising solution for addressing the rising complexity and demand of health service users worldwide. Undeniably, the continued delivery of high-quality patient care during times of unprecedented complexity and pressure is fundamental to the present and future safety of patients. Although most of the studies included in this review were conducted in high-income countries, they provide strong evidence that the positive, comparable effectiveness of advanced nurse practitioners, can be explored and exported into low to middle-income countries. Utilizing advanced nurse practitioners to facilitate effective healthcare should be considered an international healthcare imperative at the policy level.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors of this review declare no known conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Natalie Gabe (NB) as an expert librarian of the Hampshire Hospitals Foundation Trusts in refining the search strategy used for this review.

Funding

This review received no funding.

Authors’ contributions

MH conducted the preliminary literature search and final literature search, completed the study selection, critically appraised the studies, extracted data, analyzed, interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript. DW participated in the data analysis, interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Maung Htay, Email: maung.htay@hhft.nhs.uk.

Dean Whitehead, Email: dean.whitehead@utas.edu.au.

Appendix 1

file:///C:/Users/Maung/Downloads/suggested_risk_of_bias_criteria_for_epoc_reviews.pdf

Key search terms used for ANP outcomes/ effects

| Databases | Key search terms | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed/Medline | ("Physician Assistant*" OR "Mid Level Pract*" OR "Advance* Nurs* Pract*" OR "Consultant Nurse*" OR "Clinical Nurse Specialist*" OR "ANP*" OR "Advanc* Pract* Nurs**" OR "Nurse Practitioner*" OR "Nurse Clinician*" OR "Non-Physician*" OR "ENP*" OR "Emergency Nurs* Pract*" OR "Advanc* Clinical Pract*" OR "Nurse Led" OR "Nurse Specialist*").ti,ab ("meta analys*" OR "RCT*" OR "literature review*" OR "systematic review*" OR "randomised control trial*" OR "randomized control trial*" OR "scoping review*" OR "Cochrane Review*").ti,ab |

429 |

| Embase | 605 | |

| CINHAL | 324 | |

| Corchrane Registry | 545 | |

|

Cochrane Trials Cochrane EPOC |

175 2 |

|

| Edit |

Cochrane Registry looking into SR database for ANP.text – 545, but looking for ANP and variations .txt- 175 Trials & Cochrane SR database looking at ANP and variations .txt- 1

Among the first search, only a few studies were conducted related to the cost associated with ANP involvement. Therefore, search continued using original key terms combined with (cost* OR economic* OR expenditure*).ti,ab,

| Results were; |

|---|

| CINHAL-131 |

| EMBASE 257 |

| Medline 192 |

| Pubmeds 605 |

| Cochrane EPOC Trials- 112 |

| View Results (137,964) |

| Edit |

References

- Appleby J., Galea A., Murray R. The Kings Fund; UK: 2014. The NHS productivity challenge Experience from the front line. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett B.J., Garg A.X., Goeree R., Levin A., Molzahn A., Rigatto C., Singer J., Soltys G., Soroka S., Ayers D., Parfrey P.S. A nurse-coordinated model of care versus usual care for stage 3/4 chronic kidney disease in the community: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011;6(6):1241–1247. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07160810. Available from: https://doi.org/[accessed 24/04/2019] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook S, Rushforth H. Why is the regulation of advanced practice essential? Br J Nurs. 2011 Sep 8–22;20(16):996, 998–1000. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.16.996. PMID: 22067493. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Campbell J.L., Fletcher E., Britten N., Green C., Holt T., Lattimer V., Richards D.A., Richards S.H., Salisbury C., Taylor R.S., Calitri R., Bowyer V., Chaplin K., Kandiyali R., Murdoch J., Price L., Roscoe J., Varley A., Warren F.C. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telephone triage for managing same-day consultation requests in general practice: A cluster randomised controlled trial comparing general practitioner-led and nurse-led management systems with usual care (the ESTEEM trial) Health Technol. Assess. 2015;19(13):1–212. doi: 10.3310/hta19130. Available from: https://doi.org/[accessed 21/11/2018] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M.J., Machin D., WAlters S.J. 4th edition. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2007. Medical statistics: A textbook for the health sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Carney M. Regulation of advanced nurse practice: its existence and regulatory dimensions from an international perspective. J. Nurs. Manage. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jonm.12278. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jonm.12278 [accessed 20/03/2020] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission . 2019. The fundamental standards.https://www.cqc.org.uk/what-we-do/how-we-do-our-job/fundamental-standards [online]. Available from: [accessed 09/04/2019] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AJ, Chochinov AH. A systematic review of the impact of nurse practitioners on cost, quality of care, satisfaction and wait times in the emergency department. CJEM.2007 Jul;9(4):286-95. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500015189. PMID: 17626694. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chambers L.W., West A.E. The St John's randomized trial of the family practice nurse: Health outcomes of patients. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1978;7(2):153–161. doi: 10.1093/ije/7.2.153. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/681061 Available from: [accessed 25/04/2019] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D., Harris S., Roderick P., Brown D., Patel P. A randomised controlled trial of structured nurse-led outpatient clinic follow-up for dyspeptic patients after direct access gastroscopy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:12–19. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-12. Available from: https://doi.org/[accessed 09/04/2019] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K., Doblhammer G., Rau R., Vaupel J.W. Ageing populations: The challenges ahead. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61460-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2810516/ Available from: [accessed 16/05/2018] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M.A., McDowell J., Raeside L. The similarities and differences between advanced nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists. Br. J. Nurs. 2019;28(20):1308–1314. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2019.28.20.1308. Available from: https://doi.org/[accessed 01/01/2020] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamaire M., Lafortune G. Vol. 54. OECD Publishing; 2010. (Nurses in Advanced Roles: A Description and Evaluation of Experiences in 12 Developed Countries. OECD Health Working Papers). http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kmbrcfms5g7-en. [Google Scholar]

- Dierick-van Daele A.T., Metsemakers J.F., Derckx E.W., Spreeuwenberg C., Vrijhoef H.J. Nurse practitioners substituting for general practitioners: randomized controlled trial. J Adv. Nurs. 2009;65(2):391–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04888.x. Available from: https://doi.org/[accessed 08/04/2019] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grittfiths P., Recio-Saucedo A., Dall'Ora C., et al. The association between nurse staffing and omission in nursing care. a systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018;74 doi: 10.1111/jan.13564. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jan.13564 Available from: 1747–1484 [accessed 03/02/2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G., Oxman A.D., Akl E.A., Kunz R., Vist G., Brozek J., Norris S., Falck-Ytter Y., Glasziou P., DeBeer H., Jaeschke R., Rind D., Meerpohl J., Dahm P., Schunemann H.J. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. Available from: https://doi.org/[accessed 28/09/2018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham C., Alderwick H., Dunn P., McKenna H. The Kings Fund, UK; 2017. Delivering sustainability and transformation plans From ambitious proposals to credible plans. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J., and Thomas, J. (2018). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions[online]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook [accessed 28/07/2018].