Abstract

Background

Up to 40% of adults over 65 years are full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads due to urinary incontinence. Simultaneously, urinary tract infection is amongst the most common hospital-acquired infection in older patients.

Objectives

To explore the association between (1) full-time use of absorbent incontinence pads and urinary tract infection at acute hospital admission, (2) state of frailty and becoming a pad user during hospitalization, and (3) becoming a pad user and acquiring a urinary tract infection during hospitalization in older patients.

Design

A retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Admissions in an emergency department with transfers to geriatric, cardiac, infectious, or endocrinological wards from September 7th, 2017 to February 18th, 2019.

Patients

1,958 patients aged 65 years or more, having daily homecare or moderate comorbidity, hospitalized due to acute illness, and living in the municipality of Aarhus.

Methods

The study was conducted by two researchers reviewing the patients' electronic health records combined with data on frailty status from a geriatric quality database. In the electronic health records, data on baseline characteristics, absorbent incontinence pad use at admission and during the hospital stay, and urinary tract infection were obtained.

Results

Full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads had a higher probability of being admitted with urinary tract infection (Odds Ratio=2.00 (95% Confidence Interval: 1.61–2.49); p<.001). Patients identified as severely frail had a higher probability of becoming pad users during hospitalization (Odds Ratio=1.57 (95% Confidence Interval: 1.45–1.71); p<.001) compared to non/mild/moderate frail patients. Patients who became pad users during hospitalization had a higher risk of a hospital-acquired urinary tract infection (Odds Ratio=4.28 (95% Confidence Interval: 1.92–9.52); p<.001).

Conclusions

There was an association between the use of absorbent incontinence pads and the development of urinary tract infections in older hospitalized patients, both in full-time users and those who were frail and became pad users during hospitalization. These findings emphasize the need for further research on preventing urinary tract infections and unnecessary pad use in older patients.

Keywords: Aged, Frailty, Geriatrics, Cross infection, Incontinence pads, Urinary tract infections

What is already known

-

•

Urinary incontinence is a risk factor for developing urinary tract infections.

-

•

Urinary tract infections may predispose to urge incontinence.

-

•

It is unknown whether frailty status is associated with becoming a pad user during hospitalization.

What this paper adds

-

•

Full-time use of absorbent incontinence pads was associated with urinary tract infections at hospital admission in acute admitted older patients.

-

•

Fifty percent of older patients who did not use absorbent incontinence pads before hospitalisation started using them during.

-

•

Severely frail patients were more likely to start using absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalisation.

1. Introduction

Absorbent incontinence pads are “disposable devices used to contain urine or faeces and prevent unwanted leakage” (Condon et al., 2021). In Europe, adults over 65 years are amongst the most frequent users of absorbent incontinence pads, with a prevalence of as high as 39% (Sørbye et al., 2009). Even higher is the prevalence of urinary incontinence. In adults over 65, the prevalence is found to be up to 47% (Sørbye et al., 2009). Urinary incontinence is: “[…] the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine” and can be categorized as continuous urinary incontinence if there are “[…] complaints of continuous leakage” (Abrams et al., 2003). Researchers have emphasized the lack of evidence-based research in this field (Condon et al., 2021; Melo et al., 2017; Tsang et al., 2017).

A few studies have been conducted on how absorbent incontinence pads influence the development of urinary tract infections (Girard et al., 2017; Melo et al., 2017; Omli et al., 2010). Researchers have shown urinary incontinence as a risk factor for developing urinary tract infections (Caljouw et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2008). Researchers have also found a negative spiralling cascade between urinary incontinence and urinary tract infections, as incontinence may predispose to infection due to its factors affecting the vaginal bacterial ecology, and urinary tract infections may predispose to urge incontinence (Moore et al., 2008). Women have a higher risk of urinary tract infections than men, with a ratio of 2:1 (Dexter and Mortimore, 2021). A urinary tract infection can develop into urosepsis and septic shock, which can have fatal consequences for older patients (Wagenlehner and Naber, 2000). American researchers found that about 2% of urinary tract infections progress to urosepsis before treatment (Bradley et al., 2022). However, other researchers found that urosepsis had an in-hospital mortality of 33% in older patients (Tal et al., 2005).

Various factors impact the risk of urinary incontinence, such as frailty, which has been shown to increase the risk by 2.7 independently (Chong et al., 2018). In older people, frailty is a complex interaction between psychological, cognitive, physical, and social factors and can lead to decreased strength and physiological deterioration (Chong et al., 2018). Although incontinence may result from frailty in some individuals, it may also contribute to becoming frail in others. Therefore, it leads to a negative cascade between frailty status and incontinence (Chong et al., 2018). Age-related changes in the immune system contribute to an increased infection frequency in older people and a risk of hospitalization, exemplified by the fact that urinary tract infection accounts for almost 5% of all emergency department visits by adults aged 65 years and older in the United States each year (Kline and Bowdish, 2016; Schmidt, 2010; Rowe and Juthani-Mehta, 2014).

Urinary tract infections are amongst the most prevalent hospital-acquired infections in older patients (Mynaříková et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2011). In a recent study, 9.3% of patients in a geriatric ward acquire a urinary tract infection during hospitalization (Gregersen et al., 2021). Hospital-acquired urinary tract infections and pneumonia are associated with a mortality rate of 4% amongst geriatric patients (Gregersen et al., 2021). Hospital-acquired infections are defined as an infection that occurs in a patient undergoing treatment in a hospital that is not present at admission and occurs within 48 h of discharge (World Health Organization, 2011). Urinary tract infection may lead to becoming a pad user during hospitalization. Irish researchers showed that 57% of patients who did not use absorbent incontinence pads before hospitalization became users during hospitalization (Condon et al., 2021).

According to the challenges mentioned above in older patients acutely admitted to the hospital, we aimed to investigate whether there were associations between

-

(1)

full-time use of absorbent incontinence pads before hospitalization and urinary tract infection at hospital admission,

-

(2)

frailty and becoming a full-time user of absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalization and,

-

(3)

becoming a full-time user of absorbent incontinence pads and hospital-acquired urinary tract infections.

2. Methods

2.1. Design, setting and patients

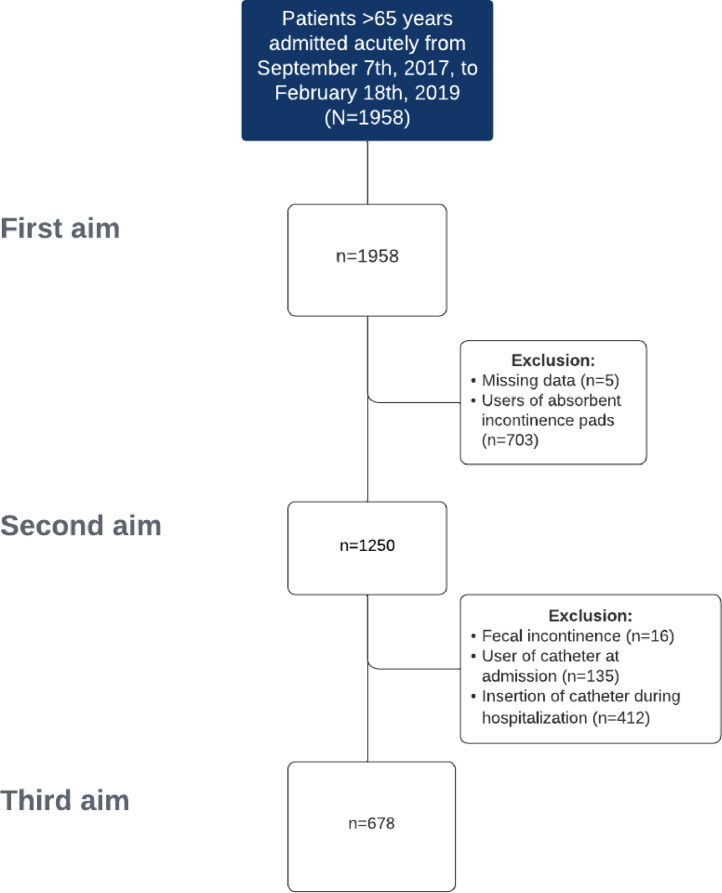

This study was designed as a retrospective observational cohort study. The patients included in the study were admitted to the emergency department due to an acute illness within the period from September 7, 2017 to February 18, 2019. After 1–2 days' emergency department stay, the patients were transferred home or to geriatric, infectious, cardiac, or endocrinological wards. On the first or second day after discharge, some patients received a multidisciplinary geriatric hospital-based team visit. The inclusion criteria were age 65 or older, daily homecare or moderate comorbidity, and living in the municipality of Aarhus. For the second and third aims, patients who were permanent pad users before admission were excluded. Additionally, for the third aim, permanent catheter users before admission and patients with faecal incontinence before or during hospitalization were excluded (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient recruitment.

2.2. Data collection

Data were obtained by reviewing the patients' electronic health records. Patients' use of absorbent incontinence pads at admission was collected by reviewing records for absorbent incontinence pads as described by the patient, hospital personnel, or in the home care admission report. Whether patients had a urinary tract infection was obtained by reviewing the microbiology record for urine samples taken before admission or up to 48 h after admission. When a urinary tract infection was registered, it required a positive microscopy response, defined by a culture of >100,000 colonies per millilitre (Boev and Kiss, 2017; Ninan et al., 2014). The use of a catheter was determined by the admission report provided by home care or hospital staff based on the descriptions of a permanent urostomy, nephrostomy, or permanent catheter. Also, data on whether the patient was diagnosed with faecal incontinence were collected.

Data on continence containment products, catheter use, and urinary tract infection during hospitalization were collected similarly.

Two researchers collected the relevant data from the patients’ electronic health records. Prior to data collection, the researchers tested the data collection method by reviewing the first 20 records together. The method was tested several times during the collection period when uncertainties occurred.

Frailty status obtained from a quality database in the Department of Geriatrics on the identical patients and period was merged with the collected data from the electronic health records. A multidisciplinary geriatric team has conducted a frailty assessment prospectively at the bedside using the Multidimensional Prognostic Index tool (Pilotto et al., 2008). This tool is based on the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment method. It classifies frailty into none/mild, moderate, or severe based on eight domains: cohabitating status, number of drugs, Activities of Daily Living, Instrumental-Activities of Daily Living, cognitive status, risk of pressure ulcer, illness severity, and nutritional status (Pilotto et al., 2008). The Multidimensional Prognostic Index is validated in a Danish version for geriatric inpatients and predicts readmission and short-term mortality (Gregersen et al., 2020).

All data were collected and managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tool hosted at Aarhus University (Harris et al., 2019).

2.3. Outcome

In this study, the outcomes of interest for the three aims were urinary tract infection at admission, becoming a full-time user of absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalisation, and hospital-acquired urinary tract infection.

2.4. Sample size

The sample size was calculated beforehand, and the power was set to 90%. The power estimation was primarily based on the research of Omli et al. (2010). They found an association between pad use and urinary tract infections in nursing home residents. To find a similar association, 100 patients were needed. However, Chao et al. (2021) found an association between the state of frailty and urinary tract infections in older patients with diabetic mellitus and chronic kidney disease. The prevalence of urinary tract infection in the patients with severe frailty was 0.229 compared to 0.161 in the less frail. Therefore, we needed a sample of 1482 patients to find a similar association. After accounting for missing data in the quality database, we included an additional 10% of patient records. Furthermore, we used a more comprehensive frailty index than Chao et al., with a minor difference between the mild/moderate and severe frail patient groups. Therefore, we included 20% of patient records additionally. It resulted in a total study population of 1958 patients.

2.5. Statistical considerations

For the first aim, two groups of patients were compared: patients who were permanent absorbent incontinence pad users before hospital admittance and those who were not. Comparisons between baseline characteristics were made by Pearson's Chi-squared test or Student's t-test. In a logistic regression model, the two groups were compared according to infections. The model was adjusted for potential confounders: age, sex, frailty, faecal incontinence, and permanent catheter use. Likewise, two groups of patients were compared for the second aim: patients who were assessed none/mild to moderately frail and patients who were assessed as severely frail. In the logistic regression model, adjustments for faecal incontinence, sex, and use of a permanent catheter before or during hospitalization were made. For the third aim, only patients who had not previously used pads or permanent catheters were included. Two groups of patients were compared: patients who became pad users during hospitalization and those who did not. The models were controlled by the goodness-of-fit test suggested by Hosmer and Lemeshow (Hosmer et al., 2013). We used two-sided significance tests for all analyses; the level of statistical significance was defined as a p-value at 5% or below. All analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

2.6. Ethical considerations

The quality database on frailty assessment was registered at the Danish Data Protection Agency (1–16–02–28–17). The data were collected in the Department of Geriatrics for a quality improvement project on early follow-up visits at home after hospital discharge (Pedersen et al., 2016). According to Danish law, no approval by The Central Denmark Region Ethical Committee was required for this study. However, permission to review the electronic health records was obtained from the managers of the respective departments at Aarhus University Hospital. The study was conducted in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and research on health databases (Declaration of Taipei) (World Medical Association, 2020, World Medical Association, 2013).

3. Results

In total, we included 1958 patients, with a mean age of 84, and about a third used absorbent incontinence pads at admission (Fig. 1). Of the included patients, the majority were female, with about 40% using absorbent incontinence pads at admission. Almost half of the patients were assessed as severely frail, while slightly over 50% lived alone. Further, approximately a third of the patients were assessed as independent in their capability to handle toilet visits. A small proportion of patients in the study were diagnosed with faecal incontinence. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of full-time pad users and non-pad users.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in 1958 patients aged 65 years or older with daily homecare or moderate comorbidity and admitted to the emergency department.

| Characteristics | Users of absorbent pads at admission N = 703 | Non-users of absorbent pads at admission N = 1255 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (%) | |||

| Women | 434 (62) | 672 (54) | |

| Men | 269 (38) | 583 (46) | <0.01 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 84.5 (7.8) | 84.2 (7.3) | .38 |

| Frailty (%), n = 1954 | |||

| Mild/Moderate | 243 (35) | 775 (62) | |

| Severe | 460 (65) | 476 (38) | <0.001 |

| Social status (%), n = 1936 | |||

| Cohabitant | 151 (22) | 381 (31) | |

| Institution | 255 (36) | 128 (10) | |

| Alone | 295 (42) | 726 (59) | <0.001 |

| Handling toilet visit (%), n = 1841 | |||

| Independent | 99 (15) | 484 (41) | |

| Minimal assistance | 83 (12) | 217 (19) | |

| Moderate assistance | 142 (21) | 205 (17) | |

| Much assistance | 205 (31) | 208 (18) | |

| Fully dependent | 142 (21) | 56 (5) | <0.001 |

| Faecal incontinence (%), n = 1953 | |||

| Yes | 76 (11) | 16 (1) | |

| No | 625 (89) | 1236 (99) | <0.001 |

| Catheter use (%), n = 1957 | |||

| Yes | 118 (17) | 140 (11) | |

| No | 585 (83) | 1114 (89) | <0.001 |

| Transferred to (%) | |||

| Home | 254 (36) | 301 (24) | |

| Dept. of Geriatrics | 406 (58) | 757 (60) | |

| Dept. of Infectious Diseases | 7 (1) | 35 (3) | |

| Dept. of Cardiology | 29 (4) | 140 (11) | |

| Dept. of Endocrinology | 1 (0) | 2 (0) | |

| Other Departments | 6 (1) | 20 (2) | <0.001 |

Of the admitted patients, 30% had a urinary tract infection in the emergency department. The use of absorbent incontinence pads was associated with a higher probability of urinary tract infection at admission. The probability was even higher amongst patients with permanent catheters at admission (Table 2). Of the included patients, about half were already full-time pad users, and four were not frailty assessed at discharge and therefore excluded before the analysis for the second aim.

Table 2.

Urinary tract infections in 65+ year old patients at admission in the emergency department.

| Before hospital admission | Urinary tract infection N = 589 | No urinary tract infection N = 1369 | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (%) n = 1106 | 361 (61) | 745 (54%) | 1.33 (1.09–1.62) | .005 | 2.04 (1.61–2.57) | <0.001 |

| Permanent pad users (%) n = 703 | 289 (49) | 414 (30%) | 2.22 (1.82–2.71) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.61–2.50) | <0.001 |

| Faecal incontinence (%) n = 92 | 33 (4.3) | 59 (5.6%) | 1.32 (0.85–2.04) | .22 | 0.79 (0.49–1.26) | .32 |

| Use of permanent catheter (%) n = 258 | 149 (25) | 109 (8%) | 3.91 (2.99–5.12) | <0.001 | 5.35 (3.92–7.29) | <0.001 |

| Assistance for toilet visits n = 611 | 223 (38) | 388 (28%) | 1.54 (1.26–1.89) | <0.001 | 1.12 (0.89–1.40) | .34 |

Mutually adjusted in a logistic regression model.

OR=Odds Ratio with 95% Confidence Interval (CI)

Females are compared to male patients and users of pads and catheters before admission are compared to non-users.

Patients with faecal incontinence are compared to no incontinence, and dependence on assistance for toilet visits is compared to non-dependents.

Table 3 shows that severe frailty was associated with faecal incontinence, use of a permanent catheter, and assistance for toilet visits during hospitalization. Also, severe frailty was associated with becoming a pad user. About half of the patients included for the second aim became pad users during their hospital stay. Patients who were assessed as severely frail compared to those mild or moderately frail had an increased probability of becoming pad users during a hospital stay (Table 4). The length of hospital stay was 6 median days, where a hospital stay of more than 7 days was also associated with becoming a pad user.

Table 3.

Frailty status according to sex, faecal incontinence, use of permanent catheter, and need of assistance for toilet visits before hospital admission to the emergency department.

| During hospitalization | Severe frailty N = 936 | No severe frailty N = 1017 | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (%) | 530 (57) | 574 (56) | 1.01 (0.84–1.20) | .90 | 1.23 (0.99–1.53) | .06 |

| Faecal incontinence (%) | 69 (7) | 23 (2) | 3.43 (2.12–5.55) | <0.001 | 2.41 (1.38–4.19) | .002 |

| Use of permanent catheter (%) | 510 (54) | 399 (39) | 1.86 (1.55–2–22) | <0.001 | 1.33 (1.07–1.65) | .01 |

| Assistance for toilet visits (%) | 532 (57) | 79 (8) | 15.6 (12.0–20.4) | <0.001 | 14.6 (11.2–19.1) | <0.001 |

Mutually adjusted in a logistic regression model.

OR=Odds Ratio with 95% Confidence Interval (CI)

Females are compared to male patients and users of catheters before admission are compared to non-users.

Patients with faecal incontinence are compared to no incontinence, and dependant on assistance for toilet visits is compared to non-dependant.

Table 4.

Becoming a permanent user of absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalization according to frailty status, sex, faecal incontinence, and length of hospital stay.

| During hospitalization | Becoming pad user N = 635 | Not becoming pad user N = 615 | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe frailty (%) n = 476 | 343 (54) | 134 (22) | 1.62 (1.49–1.76) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.45–1.71) | <0.001 |

| Females (%) n = 670 | 339 (53) | 331 (54) | 0.98 (0.79–1.23) | .88 | 1.03 (0.81–1.32) | .78 |

| Faecal incontinence (%) n = 16 | 13 (2) | 3 (0.5) | 4.24 (1.20–14.9) | .03 | 4.10 (1.08–15.5) | .04 |

| More than 7 days of hospitalization (%) n = 443 | 306 (48) | 137 (22) | 3.24 (2.54–4.15) | <0.001 | 3.01 (2.33–3.90) | <0.001 |

Mutually adjusted in a logistic regression model.

OR=Odds Ratio with 95% Confidence Interval (CI)

Severely frail are compared to non/mild/moderate frail patients. Females are compared to male patients,

Patients with faecal incontinence are compared to patients with no incontinence and length of stay of more than 7 days were compared to patients with fewer than 7 days.

Table 5 is based on 687 patients, as 1268 patients were excluded because they used absorbent incontinence pads at admission, were patients diagnosed with faecal incontinence, or used permanent catheters at admission or during hospitalization; amongst those included for the third aim, 40% became absorbent incontinence pad users during hospitalization. Of those, 11% developed a urinary tract infection compared to 2% of the patients who did not become pad users. New pad use was associated with hospital-acquired tract infection.

Table 5.

Hospital-acquired urinary infection (UTI) in patients becoming absorbent incontinence pad users during hospitalization.

| During hospitalization | Hospital-acquired UTI N = 39 | No hospital-acquired UTI N = 648 | Crude OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becoming pad user (%) n = 278 | 30 (77) | 248 (38) | 5.38 (2.51–11.5) | <0.001 | 4.28 (1.92–9.52) | <0.001 |

| Severe frailty (%) n = 209 | 19 (49) | 190 (29) | 1.32 (1.06–1.68) | .01 | 1.11 (0.88–1.39) | .40 |

| Females (%) n = 424 | 29 (74) | 395 (61) | 1.86 (0.89–3.88) | .10 | 1.71 (0.80–3.62) | .16 |

| More than 7 days of hospitalization (%) n = 167 | 17 (44) | 150 (23) | 2.57 (1.32–4.96) | .005 | 1.76 (0.88–3.51) | .11 |

Mutually adjusted in a logistic regression model.

OR=Odds Ratio with 95% Confidence Interval (CI)

Becoming a pad user is compared to not becoming a pad user. Severely frail are compared to non/mild/moderate frail patients. Females are compared to male patients, and length of stay of more than 7 days was compared to patients with fewer than 7 days.

4. Discussion

In this observational study, the first aim was to investigate whether there were associations between the full-time use of absorbent incontinence pads before hospitalization and urinary tract infection at hospital admission. Patients who were full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads before admission were twice as likely to have a urinary tract infection at admission compared to patients who were not pad users. Furthermore, the second aim was to investigate whether there were associations between frailty and becoming a full-time user of absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalization. We found that severe frailty was associated with the probability of becoming full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalization compared to patients with mild to moderate frailty. Lastly, the third aim was to investigate whether there were associations between becoming a full-time user of absorbent incontinence pads and hospital-acquired urinary tract infections. Patients who became full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalization were more than four times as likely to develop a urinary tract infection.

The findings of the first aim are consistent with a Norwegian study in which the correlation between the use of absorbent incontinence pads and urinary tract infection amongst nursing home residents was examined. Of the residents using pads, 41% acquired one or more urinary tract infections the following year, compared to only 11% non-users (Omli et al., 2010). In our study, urinary tract infection was also found in 41% of the patients admitted while using absorbent incontinence pads and 24% of the patients who did not use pads. In the Norwegian study, only nursing home residents were included. According to the literature, being a nursing home resident is related to frailty and impaired immune response (Cairns et al., 2011), all of which may have contributed to the high probability of urinary tract infections in the Norwegian study. In contrast, our study also included patients living in their own homes and who were mild to moderately frail. We therefore considered why we found the same proportion of urinary incontinence amongst the patients/residents using pads. It might be because of the inclusion of urinary and faecal continent and incontinent patients for this aim, as faecal and urinary incontinence has been shown to increase the risk of developing urinary tract infection (Caljouw et al., 2011; Melo et al., 2017). Although we made odds ratio adjustments for faecal incontinence, we cannot exclude that urinary incontinence may have contributed to the high proportion and odds ratio. Furthermore, the analysis for the first aim also showed increased odds of having a urinary tract at admission if the patient was female or had a permanent catheter. These findings are consistent with previous research, as many other studies have found an increased risk of urinary tract infection amongst females and users of permanent catheter (Girard et al., 2017).

Regarding the second aim, we found that 50% of patients who did not use absorbent incontinence pads at admission started using them during hospitalization. This finding agrees with the results of the Irish study, which showed that 57% of patients who did not use absorbent incontinence pads before hospitalization became users during hospitalization (Condon et al., 2021). Furthermore, the Irish researchers pointed out that being disabled or frail is predictive of starting the use of absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalization. Severely frail patients were more likely to start using absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalization, the same as our findings. We did not examine the reasons for becoming users of incontinence pads during hospitalization. It is not protocol to document this, and the reasons would not be found in the journals. However, other studies have shown that impaired cognitive capacity, low physical functional status, and incontinence at admission are reasons for becoming a user of incontinence pads during hospitalization (Tsang et al., 2017; Zisberg, 2011; Zisberg et al., 2011). However, in several studies, unnecessary use of incontinence pads during hospitalization has also been found. For example, Brazilian researchers found that 38% of patients who became users of incontinence pads did not have a reason to do so (Bitencourt et al., 2018). Likely, several of the older patients in our study did not have a reason either. In other studies it has been pointed out that national guidelines might reduce the unnecessary use of absorbent incontinence pads and, thereby, urinary tract infections (Bitencourt et al., 2018; Tsang et al., 2017). However, despite national guidelines regarding the use of absorbent incontinence pads in Denmark, we have found results comparable to those mentioned above (Houlind and Klarskov, 2019). Therefore, we question whether guidelines alone are enough to reduce the use of absorbent incontinence pads or whether other initiatives are needed.

Alternatives to incontinence pads during hospitalization have been studied. They include timed/prompted voiding, a commode by the bedside, and external urine collectors (bedpan or urinal) (Bitencourt et al., 2018; Kadir, 2004). Researchers have also identified the reasons for not using these alternatives as lack of time or personnel, the routine of the institution, and the patient's wish (Bitencourt et al., 2018; Kadir, 2004). Informing patients of the risk of using absorbent incontinence pads might help reduce the use of pads. Furthermore, providing information to personnel on this risk and the national guidelines regarding the use of absorbent incontinence pads might also help reduce their use. These alternatives must also be implemented in the primary care sector to prevent older people from being admitted to the hospital with a urinary tract infection. In the Danish primary care sector, the local authority grants a license for pads to receive them for free. This license is granted when someone has a medical indication for using pads. However, some older people might buy and use incontinence pads without a medical indication. In these cases, healthcare personnel should be informed of the risks of using incontinence pads and the alternatives. These alternatives can help increase patients’ health, independence, and autonomy over their bodies if implemented (Bitencourt et al., 2018).

For the third aim, we found that 11% of the patients who became full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads developed urinary tract infections during hospitalization. Furthermore, patients who became full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads had a high probability of developing urinary tract infections. We compared this finding to the 2% of the patients who did not become full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads and still developed urinary tract infections during hospitalization. To our knowledge, no studies have investigated the association between becoming a full-time user of absorbent incontinence pads and the development of urinary tract infections during hospitalization. Thus, our results may differ from previous studies investigating the association between pad use and urinary tract infections in home-care facilities. The analysis for the third aim adjustment was made regarding frailty status, female gender, and length of hospital stay. Urinary incontinence was not adjusted, which could be a potential confounder for the results. However, since patients who used absorbent incontinence pads at admission were excluded before the analysis, patients with urinary incontinence at admission were also excluded, as most urinary incontinent patients use incontinence pads. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, another study found that 38% of hospitalized patients had no reason for becoming incontinence pad users. On the other hand, older patients have a high risk of becoming urinary incontinent during hospitalization (Palmer et al., 2002). Therefore, patients who became urinary incontinent during hospitalization and started using incontinence pads were not accounted for. Urinary incontinence could not be excluded as a factor contributing to the high odds of developing urinary tract infections during hospitalization. Therefore, we concluded in the third aim that there were high odds of developing urinary tract infections amongst hospitalized older patients with a newly begun use of incontinence pads but also with a possibility for being urinary incontinent.

4.1. Strength and limitations

A homogeneous group of older patients was included in this study, which might be a strength. The specific inclusion criteria reduced the probability of a systematic error in selecting patients. Furthermore, it is a strength that we considered and accounted for several potential effect modifiers and confounders. These variables could have influenced the results. However, we note that there may be unknown confounders that were not taken into account.

Limitations include the criteria for being diagnosed with a hospital-acquired urinary tract infection, which was a positive culture of bacteria collected from a urine sample 48 h after admission and up to 48 h after discharge. During data collection, the researchers observed that several patients were readmitted to the hospital for a urinary tract infection more than 48 h after discharge, and some of the patients received no follow-up visit from the geriatric team. These patients were, therefore, not diagnosed with a hospital-acquired urinary tract infection, even though they might have acquired one. The prevalence of hospital-acquired urinary tract infection therefore may have been underestimated. Another limitation might be the potential risk of discrepancies in the retrospective data collection from the electronic health records. Although the two researchers tested the data collection method to avoid possible pitfalls, the health records might lack information on specific data. However, as the data consisted of basic geriatric information and were collected bedside by health care professionals, we consider only a few data were missing.

Urinary incontinence could be a potential confounding variable in predisposing urinary tract infections. Also, it is reasonable to assume that the full-time pad users could be urinary and faecal incontinent. However, for exploring the second and third aims, the full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads at admission were excluded to avoid confounding.

5. Conclusions

In older patients, full-time use of absorbent incontinence pads is associated with higher odds of having urinary tract infections at hospital admittance than patients who are not full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads. Being frail seems to increase the probability of becoming a pad user during hospitalization, as severely frail patients had the highest odds of becoming pad users. Patients who became full-time users of absorbent incontinence pads during hospitalization had higher odds of developing urinary tract infections. We found a need for improved care of severely frail hospital patients to prevent hospital-acquired urinary tract infections.

We recommend that home care nurses be well-educated to prevent, detect, and limit urinary incontinence in frail older adults and thereby avoid unnecessary hospital admissions. When hospitalization is unavoidable, hospital nursing staff education needs to focus on the quality of care in acutely ill older patients by prioritizing toilet assistance visits, timed/prompted voiding, and other alternatives to incontinence pads.

The clinical area warrants further development and research of new techniques to promote patients' and nurses' understanding of and motivation for alternatives to absorbent incontinence pads and reducing pad use and hospital-acquired urinary tract infections.

6. Funding sources

No external funding.

7. Data availability statement

The authors state availability of the data to foster transparency.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Emma Bendix Larsen: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Caroline Lunne Fahnøe: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Validation, Visualization. Peter Errboe Jensen: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Merete Gregersen: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the staff in the Department of Geriatrics for their careful documentation in the electronic health records and their bedside frailty assessment of patients for the quality database.

References

- Abrams P., Cardozo L., Fall M., Griffiths D., Rosier P., Ulmsten U., Van Kerrebroeck P., Victor A., Wein A. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the international continence society. Urology. 2003;61:37–49. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitencourt G.R., Alves L., de A.F., Santana R.F. Practice of use of diapers in hospitalized adults and elderly: cross-sectional study. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018;71:343–349. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boev C., Kiss E. Hospital-acquired infections: current trends and prevention. Infect. Intensive Care Unit. 2017;29:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cnc.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley M.S., Ford C., Stagner M., Handa V., Lowder J. Incidence of urosepsis or pyelonephritis after uncomplicated urinary tract infection in older women. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022;33:1311–1317. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns S., Reilly J., Stewart S., Tolson D., Godwin J., Knight P. The prevalence of health care–associated infection in older people in acute care hospitals. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011;32:763–767. doi: 10.1086/660871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caljouw M.A., den Elzen W.P., Cools H.J., Gussekloo J. Predictive factors of urinary tract infections among the oldest old in the general population. a population-based prospective follow-up study. BMC Med. 2011;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao C.T., Lee S.Y., Wang J., Chien K.L., Huang J.W. Frailty increases the risk for developing urinary tract infection among 79,887 patients with diabetic mellitus and chronic kidney disease. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:349. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02299-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong E., Chan M., Lim W.S., Ding Y.Y. Frailty predicts incident urinary incontinence among hospitalized older adults—a 1-year prospective cohort study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018;19:422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon M., Mannion E., Collins G., Ghafar M.Z.A.A., Ali B., Small M., Murphy R.P., McCarthy C.E., Sharkey A., MacGearailt C., Hennebry A., Robinson S., O'Caoimh R. Prevalence and predictors of continence containment products and catheter use in an acute hospital: a cross-sectional study. Geriatr. Nur. 2021;42:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.02.008. (Lond.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter J., Mortimore G. The management of urinary tract infections in older patients within an urgent care out-of-hours setting. Br. J. Nurs. 2021;30:334–342. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2021.30.6.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard R., Gaujard S., Pergay V., Pornon P., Martin-Gaujard G., Bourguignon L. Risk factors for urinary tract infections in geriatric hospitals. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017;97:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen M., Hansen T.K., Jørgensen B.B., Damsgaard E.M. Frailty is associated with hospital readmission in geriatric patients: a prognostic study. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020;11:783–792. doi: 10.1007/s41999-020-00335-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen M., Mellemkjær A., Foss C.H., Blandfort S. Use of single-bed rooms may decrease the incidence of hospital-acquired infections in geriatric patients: a retrospective cohort study in Central Denmark region. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy. 2021;135581962199486 doi: 10.1177/1355819621994866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., Elliott V., Fernandez M., O'Neal L., McLeod L., Delacqua G., Delacqua F., Kirby J., Duda S.N. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer D.W., Lemeshow S., Sturdivant R.X. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. 3rd ed. Wiley; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2013. Applied logistic regression. ed. [Google Scholar]

- Houlind J., Klarskov O.P. SSI; 2019. Prevention of Urinary Tract Infection in Relation to Urinary Tract Drainage and Incontinence Aids (No. 1,2), National Infection Hygiene Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- Kadir F.S. The “Pamper” generation: an explorative study into the use of incontinence aids in a local acute peripheral care setting. Singap. Nurs. J. 2004;31:34–38. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kline K.A., Bowdish D.M. Infection in an aging population. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016;29:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo L.S.D., Ercole F.F., Oliveira D.U.D., Pinto T.S., Victoriano M.A., Alcoforado C.L.G.C. Urinary tract infection: a cohort of older people with urinary incontinence. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017;70:838–844. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore E.E., Jackson S.L., Boyko E.J., Scholes D., Fihn S.D. Urinary incontinence and urinary tract infection: temporal relationships in postmenopausal women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;111:317–323. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318160d64a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mynaříková E., Jarošová D., Janíková E., Plevová I., Polanská A., Zeleníková R. Occurrence of hospital-acquired infections in relation to missed nursing care: a literature review. Cent. Eur. J. Nurs. Midwifery. 2020;11:43–49. doi: 10.15452/cejnm.2020.11.0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ninan S., Walton C., Barlow G. Investigation of suspected urinary tract infection in older people. BMJ. 2014;349:g4070–g4073. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omli R., Skotnes L.H., Romild U., Bakke A., Mykletun A., Kuhry E. Pad per day usage, urinary incontinence and urinary tract infections in nursing home residents. Age Ageing. 2010;39:549–554. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer M.H., Baumgarten M., Langenberg P., Carson J.L. Risk factors for hospital-acquired incontinence in elderly female hip fracture patients. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2002;57:M672–M677. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.10.M672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen L.H., Gregersen M., Barat I., Damsgaard E.M. Early geriatric follow-up after discharge reduces readmissions – a quasi-randomised controlled trial. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2016;7:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.eurger.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilotto A., Ferrucci L., Franceschi M., D'Ambrosio L.P., Scarcelli C., Cascavilla L., Paris F., Placentino G., Seripa D., Dallapiccola B., Leandro G. Development and validation of a multidimensional prognostic index for one-year mortality from comprehensive geriatric assessment in hospitalized older patients. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:151–161. doi: 10.1089/rej.2007.0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe T.A., Juthani-Mehta M. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection in older adults. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2014;28:75–89. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. Mortality following acute medical admission in Denmark: a feasibility study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010;195 doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørbye L.W., Finne-Soveri H., Ljunggren G., Topinkova E., Garms-Homolova V., Jensdóttir A.B., Bernabei R., for AdHOC Project Research Group Urinary incontinence and use of pads - clinical features and need for help in home care at 11 sites in Europe. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2009;23:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal S., Guller V., Levi S., Bardenstein R., Berger D., Gurevich I., Gurevich A. Profile and prognosis of febrile elderly patients with bacteremic urinary tract infection. J. Infect. 2005;50:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang L.F., Sham S.Y.A., Chan S.K. Identifying reasons, gaps and prevalence of diaper usage in an acute hospital: diaper usage. Int. J. Urol. Nurs. 2017;11:151–158. doi: 10.1111/ijun.12143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenlehner F.M.E., Naber K.G. Hospital-acquired urinary tract infections. J. Hosp. Infect. 2000;46:171–181. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2011. Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide: A systematic review of the literature. Available from: https://www.who.int.

- World Medical Association, 2013. WMA declaration of Helsinki - ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post. Last updated 6th September 2022.

- World Medical Association, 2020. WMA declaration of Taipei on ethical considerations regarding health databases and biobanks. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post. Last updated 4th June 2020.

- Zisberg A. Incontinence brief use in acute hospitalized patients with no prior incontinence. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2011;38:559–564. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e31822b3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisberg A., Gary S., Gur-Yaish N., Admi H., Shadmi E. In-hospital use of continence aids and new-onset urinary incontinence in adults aged 70 and older. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011;59:1099–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors state availability of the data to foster transparency.