Abstract

The standardization of clinical studies using extracellular vesicles (EVs) has mainly focused on the procedures employed for their isolation and characterization; however, preanalytical aspects of sample collection, handling and storage also significantly impact the reproducibility of results. We conducted an online survey based on SPREC (Standard PREanalytical Code) among members of GEIVEX (Grupo Español de Investigación en Vesiculas Extracelulares) to explore how different laboratories handled fluid biospecimens destined for EV analyses. We received 70 surveys from forty‐three different laboratories: 44% focused on plasma, 9% on serum and 16% on urine. The survey indicated that variability in preanalytical approaches reaches 94%. Moreover, in some cases, researchers had no access to all relevant preanalytical details of samples, with some sample aspects with potential impact on EV isolation/characterisation not coded within the current version of SPREC. Our study highlights the importance of working with common standard operating procedures (SOP) to control preanalytical conditions. The application of SPREC represents a suitable approach to codify and register preanalytical conditions. Integrating SPREC into the SOPs of laboratories/biobanks will provide a valuable source of information and constitute an advance for EV research by improving reproducibility and credibility.

Keywords: biobanking, biomarkers, extracellular vesicles, preanalytics, SPREC, standardisation

1. INTRODUCTION

The discovery of extracellular vesicles (EVs) and their description as fundamental players in intercellular communication has contributed to significant advances in our understanding of various physiological and pathological scenarios. Due to their therapeutic and diagnostic potential, EVs may significantly impact basic and translational research across diverse biomedical fields (Couch et al., 2021; Hadizadeh et al., 2022).

Importantly, intrinsic handicaps associated with the analysis of submicron structures lying below the resolution limit of optical techniques and the heterogeneous nature of EVs possess elevated levels of technical and methodological difficulties for the development of the field. Therefore, EV research has pushed purification and analysis techniques to their limits, making standardisation a challenging but necessary step in translating basic EV research into clinical practice.

Since its creation in 2012, ISEV (International Society of Extracellular Vesicles) has created awareness among scientists and publishers regarding the technical difficulties associated with EV‐related studies and established minimal requirements to ensure reproducibility (Nieuwland et al., 2020). ISEV supports the use of EV‐TRACK (Transparent Reporting and Centralizing Knowledge In Extracellular Vesicle Research) (Roux et al., 2020; Van Deun et al., 2017) as a means for authors to improve the description of EV‐related methods to enhance reproducibility. Hence, a significant aspect of ISEV's activity has been the establishment of a rigour and standardisation committee as a platform for the EV community to increase reproducibility and credibility (Nieuwland et al., 2020). Most approaches to date focus on the procedures employed for the isolation and characterisation of EVs from biological samples; however, preanalytical aspects of sample collection remain relatively underappreciated.

SPREC (Standard PREanalytical Code) was developed in 2009 by ISBER (International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories) to provide a comprehensive tool to document the in vitro preanalytical details of biospecimens (Betsou et al., 2010). SPREC's objective is to facilitate comparisons of preclinical and clinical studies via the annotation of biospecimens with preanalytical factors that fulfil two criteria: (a) their variation is known or highly suspected to impact analytical results, and (b) they are within the control of biorepositories or biobanks and thus can be anticipated and standardised in standard operating procedures (SOPs) (Lehmann et al., 2012). SPREC revisions have appeared as a consequence of new knowledge derived from biospecimen science (e.g., novel collection approaches, handling and processing), which include interface tools to automatize SPREC calculations and indicators for quality management (Betsou et al., 2018; Lehmann et al., 2012).

GEIVEX (Grupo Español de Investigación en Vesiculas Extracelulares; The Spanish Society for Research and Innovation in Extracellular Vesicles) was born after the first ISEV conference in Göteborg (Sweden) in April 2012 (Araldi et al., 2012). This initially small group of researchers understood the clinical relevance of EVs and the technical difficulties involved in their study; and formed a working group (Borràs et al., 2012) that gave rise to a scientific society, founded in May 2013, that actively contributes to the dissemination of scientific knowledge regarding EVs and its integration into clinical diagnostic processes in Spain.

We launched a survey among the GEIVEX community, more than 200 active members, to summarise the preanalytical conditions used in different laboratories to isolate and characterise EVs from human samples. The results indicated that many researchers lacked a complete understanding of the preanalytical conditions of their samples (displaying elevated levels of heterogeneity even when employing the same biological fluid) and that current SPREC options for codification do not reflect critical parameters impacting EV research.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

A web‐based survey of preanalytical parameters of biological fluid collection for EV isolation/characterisation was designed using Google Forms and distributed to GEIVEX members. The survey included information regarding preanalytical variables contained in the SPREC catalogue. This information was distributed in seven categories: type of sample, type of primary container, pre‐centrifugation, centrifugation, second centrifugation, post‐centrifugation delay and long‐term storage. Table S1 includes the parameters contained in each category (Lehmann et al., 2012).

3. RESULTS

From a survey aimed at collecting information from different laboratories in Spain working on EVs regarding biospecimen collection and processing, prior to EV isolation and characterisation, we received a total of 70 survey answers from 43 different laboratories between 12/04/2021 and 27/12/2021, with each answer corresponding to handling a given biofluid by a given laboratory. Each laboratory received a number ID. Tables 1 and 2 summarises the SPREC parameters resulting from the preanalytical information provided by the different laboratories, according to sample type, the container used, and protocol.

TABLE 1.

SPREC parameters from the different laboratories responding to the survey

| Laboratories IDs | Sample type | Type of primary container | Precentrifugation delay conditions | Centrifugation | Second centrifugation | Postcentrifugation delay conditions | Long Term Storage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | ASC | XXX | F | Z | N | A | Z |

| #2 | PL1 | EDG | A | Z | N | B | A |

| #2 | PL1 | EDG | D | Z | N | B | A |

| #2 | PL1 | EDG | F | Z | N | B | A |

| #3 | BLD | PED | X | B | N | N | A |

| #4 | PL1 | PIX | B | Z | N | A | D |

| #5 | PL2 | SCK | A | D | N | A | D |

| #6 | PL2 | CPD | A | A | I | B | O |

| #7 | PL2 | SED | B | C | N | A | A |

| #8 | PL1 | PED | A | B | N | D | X |

| #9 | PL2 | PED | A | A | Z | N | A |

| #10 | PL2 | SCI | A | A | I | B | A |

| #11 | SEM | XXX | A | A | A | N | D |

| #12 | PL1 | SED | A | D | N | N | A |

| #13 | PL1 | EDG | B | C | C | N | A |

| #14 | SEM | ZZZ | O | N | N | N | D |

| #15 | PL1 | SHP | C | B | N | X | D |

| #16 | BLD | HEP | A | F | N | A | B |

| #17 | PL1 | EDG | B | C | N | X | D |

| #18 | CRD | CPD | K | Z | N | N | D |

| #19 | CRD | CPD | K | Z | N | N | D |

| #20 | BLD | CPD | K | Z | N | N | D |

| #21 | SER | PXD | B | A | N | C | N |

| #22 | BMK | PET | B | J | Z | G | Z |

| #23 | PL2 | PED | A | A | N | B | A |

| #24 | BLD | ACD | A | A | N | B | A |

| #25 | PEN | PPS | K | A | N | B | J |

| #26 | PL1 | EDG | B | J | N | A | A |

| #27 | ZZZ | SED | A | N | N | N | B |

| #28 | SYN | XXX | A | C | N | N | A |

| #28 | SYN | XXX | C | C | N | N | D |

| #29 | BLD | XXX | X | X | N | X | A |

| #29 | SER | XXX | X | X | N | X | A |

| #30 | BLD | XXX | X | X | N | X | A |

| #31 | PL1 | PED | B | D | N | A | A |

| #32 | URM | PET | A | D | N | A | J |

| #33 | PL1 | SCI | A | A | N | N | A |

| #34 | URN | PIX | C | J | N | B | A |

| #35 | PL1 | SED | A | A | N | N | G |

| #35 | PL1 | SED | C | A | N | N | G |

| #36 | ZZZ | PPS | A | A | N | N | A |

| #37 | PL1 | EDG | B | D | N | N | A |

| #38 | URN | PET | E | D | N | N | A |

#SPREC codes detailed in Table S1.

TABLE 2.

SPREC codes of the different GEIVEX laboratories responding to the survey

| Laboratories IDs | Sample type | Type of primary container | Precentrifugation delay conditions | Centrifugation | Second centrifugation | Postcentrifugation delay conditions | Long Term Storage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #39 | SER | SST | A | A | N | N | A |

| #39 | SER | SST | C | A | N | N | A |

| #39 | SER | SST | B | A | N | N | A |

| #39 | SER | SST | D | A | N | N | A |

| #39 | PL2 | SCK | C | A | J | N | A |

| #39 | PL2 | SCK | E | A | J | N | A |

| #39 | PL2 | SCK | G | A | J | N | A |

| #39 | PL2 | SCK | I | A | J | N | A |

| #39 | PL2 | PED | B | A | J | N | A |

| #39 | URN | PPS | A | N | N | N | A |

| #39 | URN | PPS | B | N | N | N | A |

| #39 | URN | PPS | A | A | N | N | A |

| #39 | URN | PPS | B | A | N | N | A |

| #39 | ASC | PPS | A | A | N | N | A |

| #39 | ASC | PPS | C | A | N | N | A |

| #39 | ASC | PPS | B | A | N | N | A |

| #39 | ASC | PPS | D | A | N | N | A |

| #40 | PL1 | EDG | B | D | J | A | A |

| #40 | PL1 | EDG | B | D | N | A | A |

| #40 | URN | PET | E | C | J | A | A |

| #40 | URN | PET | E | C | N | A | A |

| #41 | PL2 | SCI | F | B | B | B | A |

| #41 | URM | PET | E | B | Z | B | K |

| #42 | PL2 | EDG | C | B | E | B | J |

| #42 | PL2 | SCK | I | B | E | B | J |

| #43 | URN | ZZZ | B | C | N | A | Z |

| #43 | ZZZ | ZZZ | A | Z | Z | B | A |

#SPREC codes detailed in Table S1.

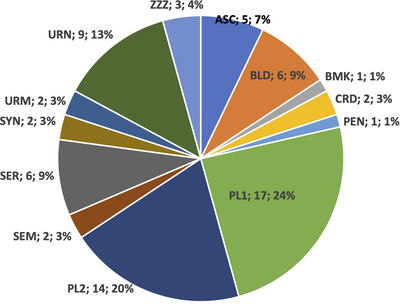

As shown in Figure 1, surveys provided information mainly on plasma (44%), urine (16%) and serum (9%), followed by a mixture of different biofluid specimens.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of protocols according to the type of fluid biospecimen. ASC, ascites fluid; BLD, whole blood; BMK, breast milk; CRD, cord blood; PEN, non‐viable cells from non‐blood specimen type (e.g., ascites, amniotic); PL1, single‐spun plasma; PL2, twice‐spun plasma; SEM, semen; SER, serum; SYN, synovial fluid; URM, first‐morning urine; URN, random (‘spot’) urine; ZZZ, Other.

Table 3 groups the protocols according to sample type, indicating the number of laboratories that provided data for each biospecimen collection and their given IDs. Specific laboratories (e.g., #2, #28, #35, #39, #40 and #42) reported using distinct protocols for the same sample type due to different collection conditions.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of protocols according to sample type

| Sample type | Number of Laboratories | Laboratory IDs | Protocols (Total) | Protocols (Lab) | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASC | 2 | #1, #39 | 5 | 1 (1); 4 (39) | |

| BLD | 6 | #3, #16, #20, #24, #29, #30 | 6 | 1 each | Laboratories 29, 30 same SPREC |

| BMK | 1 | #22 | 1 | 1 | |

| CRD | 2 | #18, #19 | 2 | 1 each | Same SPREC |

| PEN | 1 | #25 | 1 | 1 | |

| PL1 | 13 | #2, #4, #8, #12, #13, #15, #17, #26, #31, #33, #35, #37, #40 | 17 | 1 each,except 3 (2); 2 (35); 2 (40) | |

| PL2 | 9 | #5, #6, #7, #9, #10, #23, #39, #41, #42 | 14 | 1 each, except 5 (39); 2 (42) | |

| SEM | 2 | #11, #14 | 2 | 1 each | |

| SER | 3 | #21, #29, #39 | 6 | 1 each, except 4 (39) | |

| SYN | 1 | #28 | 2 | 2 (28) | |

| URM | 2 | #32, #41 | 2 | 1 each | |

| URN | 5 | #34, #38, #39, #40, #43 | 9 | 1 each, except 4 (39); 2 (40) | |

| ZZZ | 3 | #27, #36, #43 | 3 | 1 each |

3.1. Blood

Among those laboratories using plasma, a delay ranging from 2 to 24 h occurred before plasma processing (Figures 2 and S1). From the 31 surveys focused on plasma (PL1 and PL2):

20 reports (64%) described processing samples within 2 h after extraction but with different temperatures of processing (10 at room temperature [RT] and 10 at 2–10°C)

5 (16%) between 2 and 4 h (4 at RT and 1 at 2–10°C)

3 (10%) between 4 and 8 h (1 at RT and 2 between 2 and 10°C)

3 (10%) after 8 h or more (at RT)

FIGURE 2.

Schematic overview of the different approaches for handling twice‐spun plasma (PL2) biospecimens. Created with BioRender.com

Most blood biospecimens require irreversible inhibition of blood coagulation, with different laboratories using a considerable variety of anticoagulants, including:

EDTA and gel (EDG, n = 10)

Potassium EDTA (PED, n = 6)

Sodium EDTA (SED, n = 5)

Citrate phosphate dextrose (CPD, n = 4)

Sodium citrate (SCI, n = 3)

Acid citrate dextrose (ACD, n = 1)

Lithium heparin (HEP, n = 1)

Sodium heparin (SHP, n = 1)

Laboratories employed a 3000 × g centrifugation step in some (but not all) cases, followed by a second centrifugation step with variable speeds.

Data from Table 3 reflect an almost complete lack of standardisation—very few laboratories shared preanalytical conditions (same SPREC) while handling a given biofluid specimen, except for laboratories #18 and #19 which represented the only laboratories evaluating cord blood (CRD) and shared the same protocol (see Figures 2 and S1–S3). Laboratories #13 and #40 indicated that the type of sample processed is PL1 but included a second centrifugation step (Table 3 and Figure S1), suggesting that they may have misinterpreted the code meaning.

3.2. Urine

Results from laboratories assessing urine also demonstrated differences in the collection tubes, temperature and speed of the centrifugation steps (Figure 3). Moreover, different initial samples can also be defined according to their collection process (random, first urine in the morning, etc.) Our survey found that the seven laboratories (11 surveys) directly involved in urine handling also displayed a lack of consensus in their SOPs (Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 3). Similar to the analysis of blood samples, several steps in urine sample pipeline would require standardisation—from the collection of urine to biomarker analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Schematic overview of the different approaches for handling first‐morning urine (URM) and random (‘spot’) urine (URN) biospecimens. Created with BioRender.com

3.3. Other biofluids

A total of eleven laboratories reported their research with other fluid biospecimens, such as ascites (laboratories #1 and #39), semen (#11 and #14), cord blood (#18 and #19), breast milk (#22), synovial liquid (#28), (Figures S4–S6) and formats such as cell culture supernatants or peritoneal liquid effluent (#27, #36, #43) (Figure S7), that lie out of the available current SPREC codes. Unfortunately, we lack studies evaluating the impact of preanalytical variables on the characterisation of EVs from these fluid biospecimens.

3.4. SPREC codes

Importantly, laboratories #29 and #30 evaluated whole blood samples (BLD) and reported the same protocol; however, these two laboratories did not describe their protocols based on SPREC parameters (Figures S2 and S7) since some parameters employed lay outside the possibilities.

In this regard, Table 4 summarises those pre‐analytics not collected within a specific SPREC parameter. SPREC codification is lacking some biofluids (cell culture supernatant but also peritoneal dialysis effluent). Of relevance for the EV field, some sample containers are not coded, such as glass vials, while others are not detailed in their composition. Different plastics have been reported to have different adhesivity to EVs and therefore may affect EV isolation yield or characteristics (Konoshenko et al., 2018).

TABLE 4.

Preanalytics collected in the survey that was not included in SPREC (variables marked as ZZZ)

| SPREC item | Preanalytical descriptions | Laboratories involved |

|---|---|---|

| Sample type | Cell culture supernatants | #27, #36 |

| Peritoneal dialysis effluent | #43 | |

| Type of primary container | Plastic with no more specifications | #14 |

| Plastic flask containing cells | #36 | |

| 50‐mL urine sample container | #43 | |

| Not specification provided | #43 | |

| Pre‐centrifugation | ||

| First centrifugation | 4°C 30 min 1000 g × | #1 |

| RT 5 min 3000 rpm × | #2 | |

| 4°C 20 min 2500 g with braking | #4 | |

| 4°C 30 to 120 min > 10,000 g with braking | #18, #19, #20 | |

| No indication of centrifugation conditions. There is a pre‐centrifugation step before the second centrifugation (filter supernatant 0.2 μm) | #43 | |

| Second centrifugation | RT 20 min 3000 g × | #9 |

| × 60 min 3500 g × | #22 | |

| No information provided | #41, #43 | |

| Post‐centrifugation | ||

| Long‐term storage | Cristal vials –85°C to –60°C | #1, #22 |

| No information provided | #42 |

Abbreviations: RT, room temperature; X, no specification of any of the parameters included in the item (e.g., temperature, braking).

Haemolysis impacts EV‐related analytes such as microRNAs (Aguilera‐Rojas et al., 2022; Lippi et al., 2019) and requires careful assessment. For this reason, we strongly suggest the incorporation of haemolysis into SPREC. Finally, some centrifugation options and the inclusion of filtration steps are also not coded in SPREC options, or researchers lack relevant information on their preanalytical sample conditions to complete the full code for their samples.

In sum, overall, our data indicated that the variability of approaches in biofluid handling reached 94% (66 of the 70 protocols collected in the survey displayed differences). Incorporation of SPREC codes into the methods section of the manuscripts will improve awareness of this heterogeneity, while some of the SPREC codes may need an adaptation to incorporate parameters that may have a crucial impact on EV isolation.

4. DISCUSSION

The analysis of EVs obtained from liquid biopsies provides an excellent opportunity to define the pathological state of a patient; however, implementing robust EV‐based assays in a clinical scenario will require strict control of the preanalytical and analytical phases (Špilak et al., 2021). The establishment of rigorous SOPs will minimise variability in preanalytical procedures and support interlaboratory standardisation of clinically relevant data, which ideally reflect recommendations for EV‐analysis of fluid biospecimens and assays presented as a result of scientific consensus (Coumans et al., 2017; Gandham et al., 2020; Geeurickx & Hendrix, 2020; Grölz et al., 2018).

Here we aimed to analyse the current state of preanalytical aspects (i.e., liquid biospecimen handling) of protocols employed by different Spanish laboratories working in EVs. We performed a survey based on SPREC as a normalised means of collecting critical indicators describing the preanalytical process—from biospecimen collection to long‐term storage (Betsou et al., 2010).

4.1. Collection and handling

The duration of biospecimen transport represents one of the most critical preanalytical indicators for all biological samples. Different International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards define said durations, including ISO15189:2013 (requirements for quality and competence of medical laboratories) (Vermeersch et al., 2021), ISO20387:2018 (requirements designed to demonstrate the competence of a biobank's operation, and the ability to provide biological material and associated data for research and development) (De Blasio & Biunno, 2021), and UNE‐CEN/TS17747:2022 (specifications for pre‐examination processes for exosomes and other EV in whole venous blood—DNA, RNA and proteins). Biospecimen information represents a crucial means to identify samples suitable for EV analysis, as analytical stability displays time and temperature dependence for most laboratory approaches. In addition, interpreting analytical results for drug monitoring, hormones or other parameters exhibiting circadian variation (Lippi et al., 2019) requires sample information.

In terms of time and temperature related to transport, we observed considerable variability even within the same specimen type. Therefore, this level of variability might impact results and should be considered during interpretation, mainly when samples undergo processing in different collection sites, and should be definitively quoted under the methods section of the reports to evaluate the impact of changes in these parameters and to allow cross‐comparison studies among different cohorts.

4.2. Blood samples

Sixty‐two percent of surveys collected related to the handling of whole blood (BLD), plasma (PL1 and PL2) and serum (SER) (Figure 1). Preanalytical issues related to blood biospecimens remain similar to those in other diagnostic testing areas, including accurate patient identification and appropriate procedures for sample collection, handling, transportation, and storage (Buoro & Lippi, 2018).

Relevant for blood samples, and impacting also on EV isolation profiles, are coagulation parameters. It has been shown that anticoagulants have an important impact on the blood EVs composition (György et al., 2014; Palviainen et al., 2020). EDTA is one of the anticoagulants more accepted in the community and in fact it has been shown that this chelant stabilises the platelet‐derived EVs during blood collection and handling (Buntsma et al., 2022). However, some studies have provided evidence that EDTA tubes do not prevent changes in EV profiles (Geeurickx & Hendrix, 2020), we understand little regarding the impact of EDTA alternatives on EV characterisation. These concerns are important in terms of determining in a reproducible manner the concentration of blood EVs, and considering that EVs from platelets constitute one of the major challenges unmasking biomarkers of non‐platelet‐related diseases. This aspect may be of particular relevance when the initial sample is single‐spun plasma that will probably lead to some contamination of EV isolates by platelets ruptured during freezing. Another important concern to choose the anticoagulant is the preservation of the molecules that are going to be analysed afterwards. Three laboratories (#5, #39, #42) used blood collection tubes containing non‐aldehyde‐based stabilisers for cell‐free nucleic acids (SCK, Figure 2), which also stabilises EVs and would constitute an ideal blood collection tube for EV handling (Heatlie et al., 2020). Another important consideration for determining EV blood composition in a reproducible manner is to elucidate how the blood collection, handling and storage is altering the protein corona (Palviainen et al., 2020; Tóth et al., 2021) as well as the coisolation with EV of platelets, lipoproteins, soluble proteins/aggregates, viruses, cfDNA/histones or circulating mitochondria.

The results of our survey indicate that this step is far from being standardised when blood samples are to be analyzed, and further studies are required to assess the final impact on EV‐related clinical data.

Laboratory #39 used a serum separator tube with a clot activator (SST, Figure S3); however, this approach induces the release of EVs from platelets after blood collection during the clot formation, suggesting that the final result after EV isolation may not represent the initial (pre‐coagulation) main EV population (UNE‐CEN/TS 17747:2022) (Bettin et al., 2022; Siwaponanan et al., 2021). However, serum is a common sample in most clinical biobanks and its use may also provide some clinically relevant data on EVs, that would require extensive validation to overcome the issue of platelet‐derived material.

Centrifugation parameters and storage conditions also affect the number of blood‐derived EVs (Vila‐Liante et al., 2016). Haemolysis of blood samples critically impacts on microRNAs analyses that are commonly assessed on EV samples (Aguilera‐Rojas et al., 2022; Lippi et al., 2019). All these aspects will have to be taken into consideration in proper standardisation approaches. A specific task force of the ISEV Rigor and Standardization Committee focuses on increasing the reproducibility of EV isolation from blood and has reported some recommendations and pre‐analytical parameters to consider for blood EV research (Clayton et al., 2019).

4.3. Urine

Recently, the ISEV Urine task force (UTF) published a position paper that evaluated the current state‐of‐the‐art information associated with urine samples—from collection to storage and future use in EV‐related experiments (Erdbrügger et al., 2021). This study identified several challenges and gaps in the current format of urine EV‐based analyses, especially (but not exclusively) for clinical applications. Among other considerations, the UTF described minimal information addressing the collection, processing, and storage of urine samples provided in most studies. To improve rigour, reproducibility, and interoperability in urine EV research, the authors suggested recommendations that included identifying the most and least variable preanalytical parameters potentially affecting EVs. These recommendations considered parameters such as ‘Collection Method’, ‘Time and type’, ‘Volume and Void’ and ‘Storage time and temperature before processing (<8 h 4°C)’ as obligatory.

Barreiro et al. reported the effect of basic preanalytical variables on the quality of urine EV isolates for their application in transcriptomic research (Barreiro et al., 2021). They reported a reduction of EV‐associated protein marker levels and RNA yield in urine samples stored at –20°C for 4 months, which impacted sequencing quality and transcript number. Through an analysis of related studies, the UTF concluded that storage of whole urine at –80°C is optimal for long‐term storage; overall, this highlights the importance of storage‐based parameters to biases in transcriptomic/proteomic studies. Encouragingly, most surveyed laboratories reported long‐term storage at this recommended temperature.

SPREC data collected on urine samples reflects most of the UTF's recommendations, with only minor modifications required to raise standards to the recommended level. Therefore, SPREC could echo the UTF's recommendations to eliminate undesirable procedures/parameters affecting urine EVs. For instance, the ISEV community widely accepts that rapid cooling (to 4°C) of urine samples avoids microbial growth or biomolecule degradation and promotes processing within 8 h to avoid additional preservation reagents. Therefore, SPREC parameters that consider maintaining samples at RT before processing should be avoided. In sharp contrast, the UTF considers as ‘Medium recommended’ parameters required by SPREC, such as the collection device/container and added preservative formulations. Aligning UTF recommendations and SPREC parameters will improve the reproducibility and interoperability of urine EV research in different laboratories.

4.4. SPREC codes adaptation to EV analyses

Reproducibility of clinical studies in the EV field is essential to provide credibility to the potential of EVs in the biomedical environment where different stakeholders (including physicians, regulatory agencies and pharmaceutical/therapeutic industries) may require convincing translatability. The tight control of the preclinical parameters remains crucial, and initiatives must create a reporting consensus in the EV field. Our findings highlight the importance of working in a framework with harmonised SOPs and implementing a quality management system that allows the registration, control, and monitoring of preanalytical indicators to guarantee the success of analysis. In this sense, and although the use of SPREC is not extended among the EV research community so far, we can find some examples of its incorporation in defining the pre‐analytical condition in biofluids handling (García‐Flores et al., 2021). Other global EV societies should consider SPREC‐based initiatives to raise awareness and establish an initial consensus on reporting the preanalytical parameters of biofluids used for EV research. Our recommendation would be that SPREC could be incorporated into the EV‐TRACK tool to foster reproducibility and credibility in the EV field. In fact, the SPREC can be easily implemented in the information management systems of the laboratories and biobanks so that the users are not working directly with the codes but with the defined pre‐analytical conditions established for each SOP.

Interestingly, our survey detected a series of preanalytical variables that are not included in the items collected in SPREC (Table 4) and could be instrumental in harmonising this valuable information. Some additional biofluids and conditioned cell media; more detailed information about plastic containers and the inclusion of glass container options or details on haemolysis parameters or lipoprotein contamination levels are recommended for their inclusion by ISBER in the following versions of SPREC.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Collecting preanalytical information represents a crucial step in EV‐based research, as it can highlight biases appearing during the characterisation and analysis of EVs from fluid biospecimens. SPREC parameters can codify and register preanalytical conditions in biofluid specimens, and integration with laboratory and biobank SOPs will constitute a valuable source of information regarding sample handling. Although some SPREC parameters require adaptation for EV isolation, the comparable codification between laboratories will encourage the universal standardisation of processes for assessing EV parameters relevant to clinical practice.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

José A. López‐Guerrero: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing‐original draft, Writing‐review & editing. Mar Valés‐Gómez: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing‐original draft, Writing‐review & editing. Francesc E. Borrás: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing‐original draft, Writing‐review & editing. Juan Manuel Falcón‐Pérez: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing‐original draft, Writing‐review & editing. María J. Vicent: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing‐original draft, Writing‐review & editing. María Yáñez‐Mó: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing‐original draft, Writing‐review & editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to Thank Stuart P. Atkinson for English editing. For multiple agency grants: This work was supported by the Generalitat Valenciana under Grant AICO/2021/183; and Ministerio Español de Ciencia e Innovación under Grant RED2018‐102411‐T TenTaCLES (Translational NeTwork for the CLinical application of Extracellular VesicleS).

López‐Guerrero, J. A. , Valés‐Gómez, M. , Borrás, F. E. , Falcón‐Pérez, J. M. , Vicent, M. J. , & Yáñez‐Mó, M. (2023). Standardising the preanalytical reporting of biospecimens to improve reproducibility in extracellular vesicle research – A GEIVEX study. Journal of Extracellular Biology, 2, e76. 10.1002/jex2.76

REFERENCES

- Aguilera‐Rojas, M. , Sharbati, S. , Stein, T. , Candela Andrade, M. , Kohn, B. , & Einspanier, R. (2022). Systematic analysis of different degrees of haemolysis on miRNA levels in serum and serum‐derived extracellular vesicles from dogs. BMC Veterinary Research, 18(1), 355. 10.1186/S12917-022-03445-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araldi, E. , Krämer‐Albers, E.‐M. , Hoen, E. N.‐‘t. , Peinado, H. , Psonka‐Antonczyk, K. M. , Rao, P. , Niel, G. V. , Yáñez‐Mó, M. , & Nazarenko, I. (2012). International Society for Extracellular Vesicles: First annual meeting. April 17–21, ISEV‐2012. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 1(1), 19995. 10.3402/JEV.V1I0.19995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro, K. , Dwivedi, O. m. P. , Valkonen, S. , Groop, P.‐H. , Tuomi, T. , Holthofer, H. , Rannikko, A. , Yliperttula, M. , Siljander, P. , Laitinen, S. , Serkkola, E. , Af Hällström, T. , Forsblom, C. , Groop, L. , & Puhka, M. (2021). Urinary extracellular vesicles: Assessment of pre‐analytical variables and development of a quality control with focus on transcriptomic biomarker research. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 10(12), e12158. 10.1002/JEV2.12158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsou, F. , Bilbao, R. , Case, J. , Chuaqui, R. , Clements, J. A. , De Souza, Y. , De Wilde, A. , Geiger, J. , Grizzle, W. , Guadagni, F. , Gunter, E. , Heil, S. , Kiehntopf, M. , Koppandi, I. , Lehmann, S. , Linsen, L. , Mackenzie‐Dodds, J. , Quesada, R. A. , & Tebbakha, R. , The ISBER Biospecimen Science Working . (2018). Standard PREanalytical Code Version 3.0. Biopreserv Biobank, 16(1), 9–12. 10.1089/BIO.2017.0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsou, F. , Lehmann, S. , Ashton, G. , Barnes, M. , Benson, E. E. , Coppola, D. , Desouza, Y. , Eliason, J. , Glazer, B. , Guadagni, F. , Harding, K. , Horsfall, D. J. , Kleeberger, C. , Nanni, U. , Prasad, A. , Shea, K. , Skubitz, A. , Somiari, S. , & Gunter, E. (2010). Standard preanalytical coding for biospecimens: Defining the sample PREanalytical code. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 19(4), 1004–1011. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettin, B. , Gasecka, A. , Li, B. o. , Dhondt, B. , Hendrix, A. N. , Nieuwland, R. , & Van Der Pol, E. (2022). Removal of platelets from blood plasma to improve the quality of extracellular vesicle research. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 20(11), 2679–2685. 10.1111/JTH.15867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borràs, F. E. , Falcón‐Pérez, J. M. , Marcilla, A. , Mittelbrunn, M. , Del Portillo, H. A. , Sánchez‐Madrid, F. , & Yáñez‐Mó, M. (2012). First Symposium of “Grupo Español de Investigación en Vesículas Extracelulares (GEIVEX)”, Segovia, 8–9 November 2012. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 2(1), 20256. 10.3402/JEV.V2I0.20256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buntsma, N. C. , Gąsecka, A. , Roos, Y. B. W. E. M. , Van Leeuwen, T. G. , Van Der Pol, E. , & Nieuwland, R. (2022). EDTA stabilizes the concentration of platelet‐derived extracellular vesicles during blood collection and handling. Platelets, 33(5), 764–771. 10.1080/09537104.2021.1991569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buoro, S. , & Lippi, G. (2018). Harmonization of laboratory hematology: A long and winding journey. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, 56(10), 1575–1578. 10.1515/CCLM-2018-0161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, A. , Boilard, E. , Buzas, E. I. , Cheng, L. , Falcón‐Perez, J. M. , Gardiner, C. , Gustafson, D. , Gualerzi, A. , Hendrix, A. n. , Hoffman, A. , Jones, J. , Lässer, C. , Lawson, C. , Lenassi, M. , Nazarenko, I. , O'driscoll, L. , Pink, R. , Siljander, P. R.‐M. , Soekmadji, C. , & Nieuwland, R. (2019). Considerations towards a roadmap for collection, handling and storage of blood extracellular vesicles. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 8(1), 1647027. 10.1080/20013078.2019.1647027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch, Y. , Buzàs, E. I. , Di Vizio, D. , Gho, Y. S. , Harrison, P. , Hill, A. F. , Lötvall, J. , Raposo, G. , Stahl, P. D. , Théry, C. , Witwer, K. W. , & Carter, D. R. F. (2021). A brief history of nearly EV‐erything – The rise and rise of extracellular vesicles. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 10(14), e12144. 10.1002/JEV2.12144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coumans, F. A. W. , Brisson, A. R. , Buzas, E. I. , Dignat‐George, F. , Drees, E. E. E. , El‐Andaloussi, S. , Emanueli, C. , Gasecka, A. , Hendrix, A. n. , Hill, A. F. , Lacroix, R. , Lee, Y. , Van Leeuwen, T. G. , Mackman, N. , Mäger, I. , Nolan, J. P. , Van Der Pol, E. , Pegtel, D. M. , Sahoo, S. , & Nieuwland, R. (2017). Methodological guidelines to study extracellular vesicles. Circulation Research, 120(10), 1632–1648. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Blasio, P. , & Biunno, I. (2021). New challenges for Biobanks: Accreditation to the New ISO 20387:2018 Standard Specific for Biobanks. Biotech (Basel (Switzerland)), 10(3), 13. 10.3390/BIOTECH10030013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdbrügger, U. , Blijdorp, C. J. , Bijnsdorp, I. V. , Borràs, F. E. , Burger, D. , Bussolati, B. , Byrd, J. B. , Clayton, A. , Dear, J. W. , Falcón‐Pérez, J. M. , Grange, C. , Hill, A. F. , Holthöfer, H. , Hoorn, E. J. , Jenster, G. , Jimenez, C. R. , Junker, K. , Klein, J. , Knepper, M. A. , & Martens‐Uzunova, E. S. (2021). Urinary extracellular vesicles: A position paper by the Urine Task Force of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 10(7), e12093. 10.1002/JEV2.12093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandham, S. , Su, X. , Wood, J. , Nocera, A. L. , Alli, S. C. , Milane, L. , Zimmerman, A. , Amiji, M. , & Ivanov, A. R. (2020). Technologies and standardization in research on extracellular vesicles. Trends in Biotechnology, 38(10), 1066–1098. 10.1016/J.TIBTECH.2020.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Flores, M. , Sánchez‐López, C. M. , Ramírez‐Calvo, M. , Fernández‐Serra, A. , Marcilla, A. , & López‐Guerrero, J. A. (2021). Isolation and characterization of urine microvesicles from prostate cancer patients: Different approaches, different visions. BMC Urology [Electronic Resource], 21(1), 137. 10.1186/s12894-021-00902-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeurickx, E. , & Hendrix, A. (2020). Targets, pitfalls and reference materials for liquid biopsy tests in cancer diagnostics. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 72, 100828. 10.1016/J.MAM.2019.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grölz, D. , Hauch, S. , Schlumpberger, M. , Guenther, K. , Voss, T. , Sprenger‐Haussels, M. , & Oelmüller, U. (2018). Liquid biopsy preservation solutions for standardized pre‐analytical workflows‐venous whole blood and plasma. Current Pathobiology Reports, 6(4), 275–286. 10.1007/S40139-018-0180-Z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- György, B. , Pálóczi, K. , Kovács, A. , Barabás, E. , Bekő, G. , Várnai, K. , Pállinger, É. , Szabó‐Taylor, K. , Szabó, T. G. , Kiss, A. A. , Falus, A. , & Buzás, E. I. (2014). Improved circulating microparticle analysis in acid‐citrate dextrose (ACD) anticoagulant tube. Thrombosis Research, 133(2), 285–292. 10.1016/J.THROMRES.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadizadeh, N. , Bagheri, D. , Shamsara, M. , Hamblin, M. R. , Farmany, A. , Xu, M. , Liang, Z. , Razi, F. , & Hashemi, E. (2022). Extracellular vesicles biogenesis, isolation, manipulation and genetic engineering for potential in vitro and in vivo therapeutics: An overview. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10, 1019821. 10.3389/FBIOE.2022.1019821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatlie, J. , Chang, V. , Fitzgerald, S. , Nursalim, Y. , Parker, K. , Lawrence, B. , Print, C. G. , & Blenkiron, C. (2020). Specialized cell‐free DNA blood collection tubes can be repurposed for extracellular vesicle isolation: A pilot study. Biopreservation and Biobanking, 18(5), 462–470. 10.1089/BIO.2020.0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konoshenko, M. Y. u. , Lekchnov, E. A. , Vlassov, A. V. , & Laktionov, P. P. (2018). Isolation of extracellular vesicles: General methodologies and latest trends. BioMed Research International, 2018, 1–27. 10.1155/2018/8545347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, S. , Guadagni, F. , Moore, H. , Ashton, G. , Barnes, M. , Benson, E. , Clements, J. , Koppandi, I. , Coppola, D. , Demiroglu, S. Y. , Desouza, Y. , De Wilde, A. , Duker, J. , Eliason, J. , Glazer, B. , Harding, K. , Jeon, J. P. , Kessler, J. , Kokkat, T. , & Betsou [International Society For B, F. (2012). Standard preanalytical coding for biospecimens: Review and implementation of the Sample PREanalytical Code (SPREC). Biopreservation and Biobanking, 10(4), 366–374. 10.1089/BIO.2012.0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi, G. , Betsou, F. , Cadamuro, J. , Cornes, M. , Fleischhacker, M. , Fruekilde, P. , Neumaier, M. , Nybo, M. , Padoan, A. , Plebani, M. , Sciacovelli, L. , Vermeersch, P. , Von Meyer, A. , & Simundic, A.‐M. (2019). Preanalytical challenges – time for solutions. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, 57(7), 974–981. 10.1515/CCLM-2018-1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwland, R. , Falcón‐Pérez, J. M. , Théry, C. , & Witwer, K. W. (2020). Rigor and standardization of extracellular vesicle research: Paving the road towards robustness. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 10(2), e12037. 10.1002/JEV2.12037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palviainen, M. , Saraswat, M. , Varga, Z. , Kitka, D. , Neuvonen, M. , Puhka, M. , Joenväärä, S. , Renkonen, R. , Nieuwland, R. , Takatalo, M. , & Siljander, P. R. M. (2020). Extracellular vesicles from human plasma and serum are carriers of extravesicular cargo‐Implications for biomarker discovery. PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0236439. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0236439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux, Q. , Van Deun, J. , Dedeyne, S. , & Hendrix, A. (2020). The EV‐TRACK summary add‐on: Integration of experimental information in databases to ensure comprehensive interpretation of biological knowledge on extracellular vesicles. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 9(1), 1699367. 10.1080/20013078.2019.1699367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siwaponanan, P. , Keawvichit, R. , Lekmanee, K. , Chomanee, N. , & Pattanapanyasat, K. (2021). Enumeration and phenotyping of circulating microvesicles by flow cytometry and nanoparticle tracking analysis: Plasma versus serum. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology, 43(3), 506–514. 10.1111/IJLH.13407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Špilak, A. , Brachner, A. , Kegler, U. , Neuhaus, W. , & Noehammer, C. (2021). Implications and pitfalls for cancer diagnostics exploiting extracellular vesicles. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 175, 113819. 10.1016/J.ADDR.2021.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, E. Á. , Turiák, L. , Visnovitz, T. , Cserép, C. , Mázló, A. , Sódar, B. W. , Försönits, A. I. , Petővári, G. , Sebestyén, A. , Komlósi, Z. , Drahos, L. , Kittel, Á. g. , Nagy, G. , Bácsi, A. , Dénes, Á. d. , Gho, Y. S. , Szabó‐Taylor, K. É. , & Buzás, E. I. (2021). Formation of a protein corona on the surface of extracellular vesicles in blood plasma. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles, 10(11), e12140. 10.1002/JEV2.12140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deun, J. , Mestdagh, P. , Agostinis, P. , Akay, Ö. z. , Anand, S. , Anckaert, J. , Martinez, Z. A. , Baetens, T. , Beghein, E. , Bertier, L. , Berx, G. , Boere, J. , Boukouris, S. , Bremer, M. , Buschmann, D. , Byrd, J. B. , Casert, C. , Cheng, L. , Cmoch, A. , & Hendrix, A. (2017). EV‐TRACK: Transparent reporting and centralizing knowledge in extracellular vesicle research. Nature Methods, 14(3), 228–232. 10.1038/NMETH.4185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeersch, P. , Frans, G. , Von Meyer, A. , Costelloe, S. , Lippi, G. , & Simundic, A.‐M. (2021). How to meet ISO15189:2012 pre‐analytical requirements in clinical laboratories? A consensus document by the EFLM WG‐PRE. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, 59(6), 1047–1061. 10.1515/CCLM-2020-1859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila‐Liante, V. , Sánchez‐López, V. , Martínez‐Sales, V. , Ramón‐Nuñez, L. A. , Arellano‐Orden, E. , Cano‐Ruiz, A. , Rodríguez‐Martorell, F. J. , Gao, L. , & Otero‐Candelera, R. (2016). Impact of sample processing on the measurement of circulating microparticles: Storage and centrifugation parameters. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, 54(11), 1759–1767. 10.1515/CCLM-2016-0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information