Abstract

Depression is a leading cause of disability, morbidity, and mortality among adolescent girls in Africa, with varying prevalence across different populations. However, there is paucity of data on the burden of depression among priority groups in unique settings like adolescent girls living in refugee settlements, where access to mental health services including psychosocial support and psychiatric consultation is scarce. We conducted a cross-sectional, descriptive, observational study among adolescent girls from 4 selected refugee settlements in Obongi and Yumbe districts, Uganda. A multi-stage sampling, and cluster sampling techniques, where each settlement represented 1 cluster was done. Prevalence of depression was assessed using the patient health questionnaire-9 modified for adolescents, followed by the P4 screener assessment tool for suicidal risks. We performed modified Poisson regression analysis to establish predictors of depression. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. We included 385 participants with a mean age of 17 (IQR: 15–18) years. The prevalence of depression was 15.1% (n = 58, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 11.6–19.0). Overall, 8.6% (n = 33) participants had recent suicidal thoughts (within 1 month) and 2.3% (n = 9) attempted suicide. Participants who experienced pregnancy (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR]: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.00–5.94, P = .049), sexual abuse (aPR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.19–3.76, P = .011), and physical abuse (aPR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.01–2.74, P = .044) were independently associated with depression. In this study, we found about one in every 6 adolescents living in refugee settlements of northern Uganda to suffer from depression, particularly among those who experienced adolescent pregnancy and various forms of abuses. Incorporating mental health care in the existing health and social structures within the refugee settlements, exploring legal options against perpetrators of sexual abuse and encouraging education is recommended in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: adolescent, depression, mood disorders, suicide

1. Introduction

Depression is a mood disorder characterized by persistently low mood/sadness, loss of appetite, poor sleep, loss of interest in previously pleasurable activities and social withdrawal, lasting at least for 2 weeks.[1] Depression can exist independently as major depressive disorder or can exist in a more complex bipolar mood disorder, where the individual experiences episodes of elevated mood, depressed mood, and periods of normalcy.[2]

Depression is a major contributor of mortality among mentally ill patients, due to its close linkage with suicide. It is also associated with impaired family, peer and romantic relationships, alcohol/drug abuse, lower educational attainment, and socioeconomic status.[3] Genetic predisposition plays a central role in the development of depression. Other factors including psychosocial stressors, especially in genetically predisposed individuals, and organic causes (stemming from substances and preexisting physical illness such as HIV infection), also have an important contribution to the development of depression.[4]

Typically, mood disorders, including depression, emerge in late adolescent years. It is however not uncommon that the subtle signs of depression among adolescents are easily missed, since the predominant presentation is somatic or physical, or symptoms may be mistaken for age-appropriate behaviors, hence remain untreated.[5] Adolescence, a developmental period between ages 10 to 19 years, is a period in which individuals’ transit from childhood to adulthood. It involves the main transformations in the domain of physical, psychological, social, and cognitive development, crucial for mental well-being. This change is associated with a state of high-level stress, and emotional instability, thus a window of opportunity for many mental illnesses including depression.[6]

Adolescents with mental health conditions are particularly vulnerable to social exclusion, discrimination, stigma (affecting readiness to seek help), educational difficulties, risk-taking behaviors, physical ill-health and human rights violations.[7,8]

Globally, 34% of adolescents, aged 10 to 19 years, are at risk of developing clinical depression.[9] It is further estimated that 1 in 7 (14%) 10 to 19-year-olds experience mental health conditions including depression, yet these remain largely unrecognized and untreated.[7]

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability, morbidity, and mortality among adolescent girls in Africa,[10] with varying prevalence across different populations, including people living with HIV.[11] The African region represents about 5.4% of the global burden of depression.[12] In Africa, about 29.19 million people (9% of 322 million) suffer from depression, and estimates place the lifetime prevalence of depressive disorders from 3.3% to 9.8%.[13] Unfortunately, these statistics are not representative of the real extent of depression in African countries due to factors including misdiagnosed, undiagnosed, and unpublished data of cases of depression and its complications, including suicide and self-harm.

In sub-Saharan Africa, there is limited epidemiological data on the prevalence of depression in adolescents. Studies on adolescent depression in sub-Saharan Africa countries documented a magnitude of 31.5% in Malaysia.[14] A few studies done in Eastern Africa showed a higher prevalence; 26.4% in Kenya,[15] and 21% in Uganda.[16]

Meanwhile[17] found a high prevalence of depression (47%) in Nakivale refugee settlement camp, western Uganda, there is paucity of information on depression among priority groups in unique settings like adolescent girls living in refugee settlements, where access to mental health services including psychosocial support and psychiatric consultation is scarce. Additionally, adolescent girls living in refugee settlements are faced with childhood abuse, physical and sexual violence, poverty, loss and grief, social exclusion, early unintended pregnancy among others,[7] which increase on the number of psychosocial stresses, perpetuating depression. In this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of depression and associated factors among adolescent girls living in 4 refugee settlements in northern Uganda.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted a community-based, cross-sectional, descriptive observational study, adopting quantitative techniques between March and June 2023.

2.2. Study setting

We conducted this study in 4 randomly selected refugee settlements of northern Uganda. According to World Vision,[18] this region is now home to more than 500,000 refugees from South Sudan, living in 48 refugee settlements in 5 districts: Adjumani, Arua, Koboko, Obongi, and Yumbe districts. Adjumani and Arua districts both have 17 refugee settlements each, Koboko has 8 while Yumbe has 6. This setting was chosen because it hosts the biggest number of refugee settlements, proposed to provide a big pool of potential respondents for sampling.

2.3. Study population

We enrolled adolescent girls living in the refugee settlements of northern Uganda. We included only respondents between 15 to 19 years old, who provided informed consent or assent and participants with major mental illnesses were excluded from the study.

2.4. Sample size estimation

We used the Kish and Lisle[19] formula for calculation of sample size for an unknown population. At 95% confidence interval, we used an error of 5%, alpha risk expressed in z score of 1.96 and proportion of 50%. We obtained a sample size of 385.

2.5. Sampling method

We used multi-stage sampling to randomly select 2 of the 5 districts within northern Uganda that host refugee settlements, where the study was conducted. The 5 districts; Adjumani, Arua, Koboko, Obongi, and Yumbe were listed in small pieces of paper, put together, mixed, and 2 of these were randomly picked out.

We also used cluster sampling to randomly identify 2 refugee settlements from each of the sampled districts that participated in the study. The refugee settlements were listed down on small pieces of paper, with each settlement representing one cluster. Two pieces of paper were randomly picked for each district (2 clusters), from which the study was conducted (4 clusters in total). The refugee settlements were randomly selected in order to avoid bias, and ensure reliability of results. We used convenience sampling in each of the clusters to select study participants.

2.6. Research instruments

We developed a semi structured questionnaire including both open and closed ended questions. We pretested the tool among respondents of similar characteristics outside the study area, after which we refined and fine-tuned the tool for reliability and validity. Depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire, a self-reported diagnostic measure of depression widely used and well validated in different settings and population groups including with adolescents. Each of the 9 items were scored on a scale of 0 to 3, allowing a total score ranging from 0 to 27. The sum score (range 0–27) indicates the degree of depression, with scores of 0 to 4, 5 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19, and ≥20 representing no depression, mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe levels of depression. Suicide ideation was assessed using the P4 screener. The P4 screener asks about the “4 P’s”: past suicide attempts, suicide plan, probability of completing suicide, and preventive factors. The tool was then exported into Kobo toolbox installed in mobile phone devices which was used for data collection.

2.7. Data collection procedures

We recruited research assistants, who were given a one-day training for acquaintance with the tool and were taken through research ethics and good clinical practice. The research assistants carried out the collection of data. They explained the purpose of the study to each of the respondents identified, and obtained informed consent, followed by administration of the questionnaire using an electronic form stored in Kobotoolbox mobile application.

2.8. Data management

The phone devices that were used to collect data were fully charged at every moment the research team set off to collect data, and the data captured in the phone was regularly saved to avoid loss of data. We safely kept the devices under key and lock before and after data collection, and limited access.

2.9. Data analysis

Data was analyzed using STATA version 15. Prevalence of depression was expressed as a percent with corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). We performed Pearson chi square and Fisher exact tests at bivariate analysis. We then performed modified Poisson regression analysis for multivariable logistic regressions on variables with P < .2 to assess associations, controlling for all potential confounders. Results were presented as adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR), with corresponding 95% CI. Level of significance was set at P < .05.

2.10. Ethical considerations

We obtained ethical approval and clearance letter from Gulu University Research and Ethics Committee (approval number: GUREC-2022-291) which was presented to the district health offices of the selected districts, to seek administrative clearance. We presented the introductory letter from the district health offices to the refugee welfare council 2 of selected refugee settlements to seek entry into the community and commence data collection. A private and comfortable room was acquired and used during the process of data collection to ensure privacy and confidentiality. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents and participation was free and voluntary. Participants were assured of their freedom to withdraw from the study at any time with no penalty. Confidentiality of the information collected was observed by using numbers and not names. The ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were observed.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics (n = 385)

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics of respondents. We included a total of 385 adolescent girls living in refugee settlements in this study. The mean age was 17 (IQR: 15–18), years, and 99.5% (n = 383) were Christians, 316 (82.1%) had attained primary education as the highest level, 85.6% (n = 329) were not working. About 56.1% (n = 216) did not live with both parents, 45.2% (n = 174) of household heads were male, and 22.1% (n = 85) of household leads were spouses. Overall, 178 (46.2%) were sexually active, and mean age of sex debut was 15.8 (SD: 1.44), years, sexual abuse was reported by 5.2% (n = 20) of respondents, of whom 25% (n = 20) were sexually abused by relatives, meanwhile physical abuse was reported by 21.6% (n = 83) of respondents, alcohol consumption was reported by 8.8% (n = 34) of respondents, 24.9% (n = 96) were married, of whom 38.5% (n = 37) were forced/ arranged. Overall, 34% (n = 131) had ever gotten pregnant, the median number of pregnancies was 1, with a minimum of 1 and maximum of 3. Up to 9.8% (n = 7) of the respondents had ever had an abortion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 385 adolescent girls living in 4 refugee settlements of northern Uganda.

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (interquartile range), years | 17 | 15–18 | 16.34–16.66 |

| Religion | |||

| Christian Muslim |

383 2 |

99.5 0.5 |

0.99–1.00 |

| Occupation | |||

| Working Not working |

56 329 |

14.6 85.6 |

0.11–0.18 |

| Average monthly income, median (interquartile range), Ugx | 0 | 0–1000 | 60.63–60.64 |

| Education | |||

| No education Primary Secondary and beyond |

5 316 64 |

1.3 82.1 16.6 |

0.78–0.86 |

| Sex of household head | |||

| Female Male |

211 174 |

54.8 45.2 |

0.50–0.60 |

| Relationship to household head | |||

| Parent Relative Husband/spouse |

251 49 85 |

65.2 12.7 22.1 |

0.60–0.70 0.09–0.16 0.18–0.26 |

| Ever gotten pregnant | |||

| Yes No |

131 254 |

34.0 66.0 |

0.29–0.39 0.61–0.71 |

| Number of pregnancies, median (min, max), times | 1 | 1, 3 | 135.57–135.64 |

| Pregnancy outcome | |||

| Live births Abortions Both |

110 7 5 |

90.2 5.7 4.1 |

0.24–0.33 0.00–0.03 0.001–0.025 |

| Married | |||

| Yes | 96 | 24.9 | 0.21–0.29 |

| No | 289 | 75.1 | 0.71–0.79 |

| Mode of marriage | |||

| Arranged/forced Willingly |

37 59 |

38.5 61.5 |

0.07–0.13 0.12–0.19 |

| Living with both parents | |||

| Yes No |

169 216 |

43.9 56.1 |

0.39–0.49 0.51–0.61 |

| Sexual abuse | |||

| Yes No |

20 365 |

5.2 94.8 |

0.03–0.08 0.93–0.97 |

| Perpetrator | |||

| Relative Stranger |

5 15 |

25.0 75.0 |

0.19–0.31 0.56–0.94 |

| Physical abuse | |||

| Yes No |

83 302 |

21.6 78.4 |

0.18–0.26 0.74–0.83 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| Yes No |

34 351 |

8.8 91.2 |

0.06–0.11 0.89–0.94 |

| Depression | |||

| Yes No |

58 327 |

15.1 84.9 |

0.11–0.19 0.81–0.89 |

3.2. Depression and suicide screening among respondents

Table 2 summarizes an overview of the results obtained from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Little interest in doing things for several days was reported by 70 (18.2%) participants, 76 (19.7%) reported feeling down, depressed, irritable or hopeless for several days, trouble falling asleep, staying asleep or sleeping too much for more than half the days was also reported by 18 (4.7%) participants, meanwhile 43 (11.2%) participants reported feeling bad about themselves or feeling that they are a failure or that they have led their self or family down for several days. Up to 43 (11.2%) participants reported thoughts that they would be better off dead or hurting themselves in some way for several days. Recent suicidal thoughts (within 1 month) were reported in 8.6 % (n = 33) of the respondents, and suicidal attempt was reported in 2.3% (n = 9) of the participants.

Table 2.

Patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression screening among 385 adolescent girls in 4 refugee settlements of northern Uganda.

| Variables | Not at all n (%) |

Several days n (%) |

More than half the days n (%) | Nearly everyday n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little interest in doing things | 299 (77.7) | 70 (18.2) | 15 (3.9) | 1 (0.3) |

| Feeling down, depressed, irritable or hopeless | 298 (77.4) | 76 (19.7) | 9 (2.3) | 2 (0.5) |

| Trouble falling asleep, staying asleep or seeping too much | 291 (75.6) | 75 (19.5) | 18 (4.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Feeling tired or having little energy | 310 (80.5) | 68 (17.7) | 7 (1.8) | 0 (0) |

| Poor appetite or eating, weight loss | 328 (85.2) | 48 (12.5) | 7 (1.8) | 2 (0.5) |

| Feeling bad about yourself or feeling that you are a failure or that you have led yourself or family down | 333 (86.5) | 43 (11.2) | 4 (1.0) | 5 (1.3) |

| Trouble concentrating on things like school, work or reading and watching TV | 318 (82.6) | 54 (14.0) | 5 (1.3) | 8 (2.1) |

| Moving or speaking slowly that other people could have noticed (or the opposite) | 368 (95.6) | 16 (4.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| Thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way | 326 (84.7) | 43 (11.2) | 9 (2.3) | 7 (1.8) |

3.3. Prevalence of depression among adolescent girls living in refugee settlements of northern Uganda

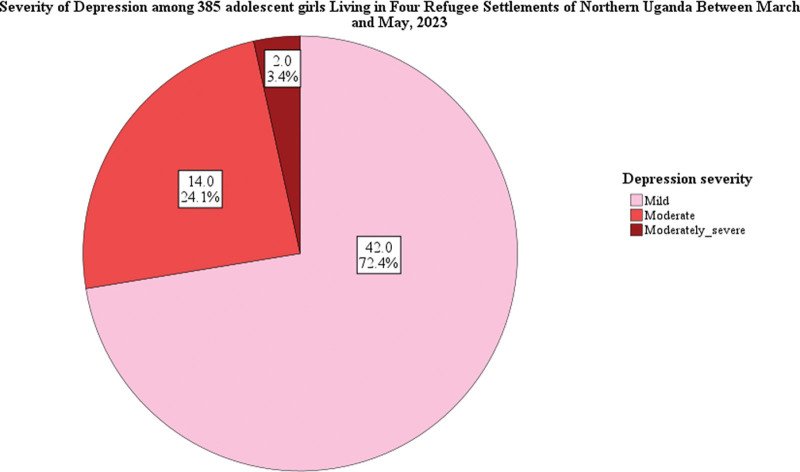

Overall, 58 (15.1%) participants had depression (95% CI: 11.6–19.0%). Figure 1 summarizes the severity of depression observed in 58 (15.1%) among the study participants. Of these, mild depression was reported in 42/58 (72.4%), moderate in 14/58 (24.1%), moderately severe in 2/58 (3.5%), and none had severe depression.

Figure 1.

Depression severity among 385 adolescent girls living in 4 Refugee settlements of northern Uganda.

3.4. Factors associated with depression among adolescent girls living in refugee settlements of northern Uganda

Table 3 summarizes bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses of factors associated with depression among adolescent girls living in refugee settlements of northern Uganda. At bivariate level, factors such as lack of formal education (PR: 4.4, 95% CI: 2.04–9.51, P < .001), female household head (PR: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.21–3.24, P = .006), living with a husband/spouse (PR: 2.3, 95% CI: 1.37–3.84, P = .002), pregnancy (PR: 3.2, 95% CI: 1.95–5.17, P < .001), no peer pressure (PR: 3.2, 95% CI: 1.95–5.31), married (PR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.33–3.40, P = .002), sexual abuse (PR: 3.4, 95% CI: 1.93–5.81, P < .002), and physical abuse (PR: 2.6, 95% CI: 1.62–4.08, P < .001) were positively associated with depression.

Table 3.

Factors independently associated with depression among 385 adolescent girls living in 4 refugee settlements of northern Uganda.

| Variable | All (N = 385) freq (%) |

Depression | Crude PR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted PR (95% CI) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=) freq (%) |

No (n=) freq (%) |

||||||

| Occupation | |||||||

| Working Not working |

56 (14.6) 329 (85.6) |

11 (2.9) 47 (12.2) |

45 (11.7) 282 (73.3) |

1.4 (0.76–2.49) Reference |

.293 | N/A | |

| Education | |||||||

| No education Primary Secondary and beyond |

5 (1.3) 316 (82.1) 64 (16.6) |

3 (0.8) 43 (11.2) 12 (3.1) |

2 (0.5) 273 (70.9) 52 (13.5) |

4.4 (2.04–9.51) Reference 1.4 (0.77–2.46) |

<.001 .280 |

2.1 (0.94–4.76) Reference N/A |

.070 |

| Sex of household head | |||||||

| Female Male |

211 (54.8) 174 (45.2) |

22 (5.7) 36 (9.4) |

189 (49.1) 138 (35.8) |

2.0 (1.21–3.24) Reference |

.006 | 0.7 (0.37–1.20) Reference |

.175 |

| Relationship to household head | |||||||

| Parent Relative Husband/spouse |

251 (65.2) 49 (12.73) 85 (22.1) |

27 (7.0) 10 (2.6) 21 (5.5) |

224 (58.2) 39 (10.1) 64 (16.6) |

Reference 1.9 (0.98–3.67) 2.3 (1.37–3.84) |

.057 .002 |

Reference 1.5 (0.78–2.84) 0.7 (0.17–2.68) |

.238 .578 |

| Pregnancy | |||||||

| Yes No |

131 (34.0) 254 (66.0) |

36 (9.35) 22 (5.7) |

95 (24.7) 232 (60.3) |

3.2 (1.95–5.17) Reference |

<.001 | 2.4 (1.00–5.94) Reference |

.049 |

| Married | |||||||

| Yes No |

96 (25.0) 289 (75.1) |

24 (6.2) 34 (8.8) |

72 (18.7) 255 (66.2) |

2.1 (1.33–3.40) Reference |

.002 | 1.3 (0.36–4.60) Reference |

.689 |

| Living with both parents | |||||||

| Yes No |

169 (43.9) 216 (56.1) |

27 (7.0) 31 (8.1) |

142 (36.9) 185 (48.1) |

1.1 (0.69–1.79) Reference |

.659 | N/A Reference |

|

| Sexual abuse | |||||||

| Yes No |

20 (5.2) 365 (94.8) |

9 (2.3) 49 (12.7) |

11 (2.9) 316 (82.1) |

3.4 (1.93–5.81) Reference |

<.001 | 2.1 (1.19–3.76) Reference |

.011 |

| Physical abuse | |||||||

| Yes No |

83 (21.6) 302 (78.4) |

24 (6.2) 34 (8.8) |

59 (15.3) 268 (69.6) |

2.6 (1.62–4.08) Reference |

<.001 | 1.7 (1.01–2.74) Reference |

.044 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||||

| Yes No |

34 (8.8) 351 (91.2) |

4 (1.0) 54 (14.0) |

30 (7.8) 297 (77.1) |

1.3 (0.50–3.39) Reference |

.582 | N/A | |

At multivariable analysis, pregnancy (aPR: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.00–5.94, P = .049), sexual abuse (aPR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.19–3.76, P = .011), and physical abuse (aPR: 1.7, 95% CI: 1.01–2.74, P = .044) were independently associated with depression.

4. Discussion

In this study, we found about 15% of adolescent girls living in the refugee settlements of northern Uganda to be having depression. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting a prevalence of 13% in Zimbabwe[20] and 16% in South Africa.[21] Conversely, Atak et al[22] found out a lower prevalence of depression among immigrant pregnant women in Turkiye, possibly due to the difference in population studied (older women vs adolescent girls). Furthermore, Anyango et al[17] found a much higher prevalence of depression in Nakivale refugee settlement, south western Uganda. This disparity could possibly be because the latter study was conducted among all adults, unlike our study that focused on adolescent girls. The ministry of health, together with implementing partners, including the office of the prime minister, need to strengthen mental health care, and increase access to these services in refugee settings. Incorporating mental health awareness campaigns and holding sensitization programs would go a long way in the early detection and treatment of depression, especially among the vulnerable population, like adolescent girls. This would also encourage help seeking among those affected, and increase adherence to treatment among those already diagnosed.

Development of depression is related to several predisposing factors, which include family history of mental health issues, genetic predisposition, or personal history of trauma among others. Our study was conducted among adolescent girls living in refugee settlements, who have undergone several psychosocial stressors like leaving their homes due to political conflict, others might have lost loved ones, property, disrupted education and other livelihood activities. These factors cannot be underestimated in considering the prevalence of depression in this unique population.

We found out several factors independently associated with the development of depression among adolescent girls living in refugee settlements of northern Uganda. Adolescent pregnancy contributed close to 3-fold risk of developing depression in our study. This was similar to findings of Mathur et al[11] in Zambia and Kenya. Similarly, Atak et al[22] also found a positive correlation between pregnancy and depression. Adolescent pregnancy, whether intended or unintended, has quite a few physical and psychosocial effects, including depression. For adolescent girls living in refugee settlements, pregnancy only adds to the already stressful refugee status, and these findings are not surprising. There is therefore need for integration of mental health and reproductive health issues in refugee settings to fully address these problems. Encouraging abstinence from sex among adolescent girls in refugee settlements will reduce on the high statistics of pregnancy, which has a secondary effect of depression. Unfortunately, policies surrounding contraceptive methods use among adolescents could be too strict, impeding its uptake. Revising these policies to allow unrestricted access to modern contraceptive methods for adolescent girls in refugee settlements will be an important consideration for addressing depression in this population.

Sexual abuse also contributed more than 2-fold risk of developing depression in our study. Sexual exploitation has similarly been reported by Kapungu et al,[23] to contribute to depression. Sexual abuse can act as a precipitating factor to the development of depression in individuals already predisposed genetically or can present an independent trigger in nongenetically predisposed individuals. There is need for exploring legal opportunities against the perpetrators of sexual abuse in this vulnerable population. Educating adolescent girls on their rights especially pertaining sexual violence and child protection will encourage help seeking among victims. The government of Uganda, in conjunction with legal societies need to create awareness of the presence of help, and put in place favorable channels through which victims can access justice. This will not only deal with the moral challenges related to sexual abuse, but also curb down the associated effects, including depression.

Our study also found out that physical abuse presented close to a 2-fold risk of developing depression among the adolescent girls living in refugee settlements of northern Uganda. It is also possible that physical abuse contributes towards adolescent pregnancies, since most of these girls will go out looking for favorable environments, only compounding on the factors that contribute to depression in this population. Physical abuse to adolescent girls living in refugee settlements presents on going psychosocial stress, perpetuating the duration of depression. Civil society organizations need to expand and strengthen their involvement in refugee settlements, mitigating challenges associated with physical abuse in this vulnerable population. It is not surprising if the perpetrators of abuses among adolescent girls living in these refugee settlements are largely relatives, or care takers from whom protection is expected. This even makes it harder for the victims to seek help, necessitating the active involvement of civil society organizations and other partners.

Additionally, the lack of protective factors like access to mental health resources, effective copying skills, positive school environment, and supportive family and social relationships, since we also found out that up to 34.8% of the respondents do not live with their parents, could possibly make it even harder for the adolescent girls living in these settlements to deal with depression and its effects, making them vulnerable to the complications that arise, including suicide. Notably, our study found out that recent suicidal thoughts (within 1 month) was reported in 8.6 % of the respondents, and suicidal attempt was reported in 2.3% of the respondents. Our findings were similar to that of Bukuluki et al[24] who found out that the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 12.6% while a suicide attempt was reported by 3.5% of the female adolescents. Incorporating mental health care in the existing health and social structures within the refugee settlements will go a long way in dealing with challenges related to depression, reducing morbidity and mortality risks in this vulnerable population. Holding sensitization campaigns will encourage help seeking, create awareness and improve adherence to treatment among adolescent girls dealing with depression, hence curb down suicide statistics in this setting.

4.1. Study limitations and strengths

Our study’s inclusion of only 4 refugee settlements might limit the generalizability of findings to all refugee settlements in Uganda, potentially affecting the external validity of our results. To address this limitation, we randomly selected settlements and employed a substantial sample size within each, strengthening the statistical reliability of our conclusions and compensating for the restricted number of settlements studied. Additionally, our study’s design is cross-sectional, which limits knowledge of causality of relationships. Future research could adopt longitudinal approaches to track changes over time and incorporate historical data, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of causal associations and enhancing the depth of our findings.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found about one in every 6 adolescents living in refugee settlements of northern Uganda to suffer from depression, particularly among those who experienced adolescent pregnancy and various forms of abuses. Incorporating mental health care in the existing health and social structures within the refugee settlements, exploring legal options against perpetrators of sexual abuse and encouraging education is recommended in this vulnerable population. There is a pressing need to explore effective interventions tailored to the unique needs of adolescents in refugee settings. Research focusing on community-based interventions, psychosocial support programs, and resilience-building strategies can provide valuable insights into addressing depression and promoting mental well-being in similar populations. Additionally, longitudinal studies assessing the long-term impact of interventions and evaluating the effectiveness of policy interventions are warranted.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Refugee Welfare Councilors (RWCs) and the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) for allowing us conduct this study in the refugee settlements. Similarly, we thank the participants for taking part in this study. We also appreciate the research assistants for the tremendous work they did. Pre-Publication Support Service (PREPSS) supported the development of this manuscript by providing author training.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Donald Otika.

Data curation: Donald Otika.

Formal analysis: Donald Otika.

Funding acquisition: Donald Otika, Felix Bongomin, Pebalo Francis Pebolo.

Investigation: Donald Otika.

Methodology: Donald Otika.

Project administration: George Odongo, Pebalo Francis Pebolo.

Supervision: George Odongo, Felix Bongomin, Pebalo Francis Pebolo.

Writing – original draft: Donald Otika, George Odongo, Ruth Mary Muzaki, Felix Bongomin.

Writing – review & editing: Donald Otika, Ruth Mary Muzaki, Beatrice Oweka Lamwaka, Felix Bongomin, Pebalo Francis Pebolo.

Abbreviations:

- aPR

- adjusted prevalence ratio

- CI

- confidence interval

This research was funded with support from Center for International Reproductive Health Training at University of Michigan (CIRHT-UM).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

How to cite this article: Otika D, Odongo G, Muzaki RM, Lamwaka BO, Bongomin F, Pebolo PF. Depression and suicidal ideation among adolescent girls in refugee settlements in northern Uganda. Medicine 2024;103:19(e38077).

Contributor Information

George Odongo, Email: georgeodong16@gmail.com.

Ruth Mary Muzaki, Email: muzakiruth16@gmail.com.

Beatrice Oweka Lamwaka, Email: lamwakabeatrice12@gmail.com.

Felix Bongomin, Email: bongomin@umich.edu.

References

- [1].American Psychiatric Association. What is depression? Source. Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression. [Google Scholar]

- [2].American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Available at: https://www.gammaconstruction.mu/sites/default/files/webform/cvs/. [Google Scholar]

- [3].World Health Organization. Adolescent mental health. 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Alshaya DS. Genetic and epigenetic factors associated with depression: an updated overview. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29:103311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Crabb J, Stewart RC, Kokota D, et al. Attitudes towards mental illness in Malawi: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].WHO. Depression and other common mental disorders global health estimates 2017. 2017. a. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [7].WHO. Mental health of adolescents. 2021. Source: Mental health of adolescents (who.int.

- [8].WHO. Adolescent mental health. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescentmental-health. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CH. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61:287–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Organization WH. Global Health Estimates 2015: Disease Burden by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2015. Geneva, 2016; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mathur S, Okal J, Musheke M, et al. High rates of sexual violence by both intimate and non-intimate partners experienced by adolescent girls and young women in Kenya and Zambia: findings around violence and other negative health outcomes. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].World Health Organization. Mental health status of adolescents in South-East Asia: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2017. b; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- [13].Esan O, Esan A. Epidemiology and burden of bipolar disorder in Africa: a systematic review of data from Africa. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. JAMA Netw. 2017;273:1–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Erskine HE, Baxter AJ, Patton G, et al. The global coverage of prevalence data for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26:395–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fattah A, Fattah MMA. Prevalence, symptomatology, and risk factors for depression among high school students in Saudi Arabia. Eur J Psychol. 2017;2:1–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Anyango L. Depression and Associated Factors Among Refugees Amidst Covid-19 in Nakivale Refugee Camp in Uganda. 2020. Available at: https://www.onlinescientificresearch.com/articles/depression-and-associated-factors-among-refugees-amidst-covid19-in-nakivale-refugee-camp-in-uganda.html. [Google Scholar]

- [18].World Vision. Building social cohesion with children West Nile, Uganda. 2018. Source: Social Cohesion Uganda.pdf (wvi.org.

- [19].Kish L. “Survey sampling 1965. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, London. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mbawa M, Vidmar J, Chingwaru C, et al. Understanding postpartum depression in adolescent mothers in Mashonaland Central and Bulawayo Provinces of Zimbabwe. Asian J Psychiatr. 2018;32:147–50. 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Govender D, Naidoo S, Taylor M. Antenatal and postpartum depression: prevalence and associated risk factors among adolescents’ in KwaZuluNatal, South Africa. Depress Res Treat. 2020;2020:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Atak M, Sezerol MA, Koçak EN, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and associated factors in immigrant pregnant women in Türkiye: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltim). 2023;102:e36616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kapungu C, Petroni S. Understanding and tackling the gendered drivers of poor adolescent mental health. International Center for Research on Women. 2020, Available at: https://www.icrw.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/09/CRW_Unicef_MentalHealth_WhitePaper_FINAL.pdf. 21. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bukuluki P, Kisaakye P, Wandiembe SP, et al. Suicide ideation and psychosocial distress among refugee adolescents in Bidibidi settlement in West Nile, Uganda. Discov Psychol. 2021;1. [Google Scholar]