Abstract

Objective:

Previous studies have reported inverse associations between certain healthy lifestyle factors and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), but limited evidence showed the synergistic effect of those lifestyles. This study examined the relationship of a combination of lifestyles, expressed as Healthy Lifestyle Score (HLS), with NAFLD.

Design:

A community-based cross-sectional study. Questionnaires and body assessments were used to collect data on the six-item HLS (ranging from 0 to 6, where higher scores indicate better health). The HLS consists of non-smoking (no active or passive smoking), normal BMI (18·5–23·9 kg/m2), physical activity (moderate or vigorous physical activity ≥ 150 min/week), healthy diet pattern, good sleep (no insomnia or <6 months) and no anxiety (Self-rating Anxiety Scale < 50), one point each. NAFLD was diagnosed by ultrasonography.

Setting:

Guangzhou, China.

Participants:

Two thousand nine hundred and eighty-one participants aged 40–75 years.

Results:

The overall prevalence of NAFLD was 50·8 %. After adjusting for potential covariates, HLS was associated with lower presence of NAFLD. The OR of NAFLD for subjects with higher HLS (3, 4, 5–6 v. 0–1 points) were 0·68 (95 % CI 0·51, 0·91), 0·58 (95 % CI 0·43, 0·78) and 0·35 (95 % CI 0·25, 0·51), respectively (P-values < 0·05). Among the six items, BMI and physical activity were the strongest contributors. Sensitivity analyses showed that the association was more significant after weighting the HLS. The beneficial association remained after excluding any one of the six components or replacing BMI with waist circumference.

Conclusions:

Higher HLS was associated with lower presence of NAFLD, suggesting that a healthy lifestyle pattern might be beneficial to liver health.

Keywords: Lifestyle, Healthy Lifestyle Score, Fatty liver disease, Liver health, Chinese

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is one of the most important liver diseases which involves simple fatty infiltration (steatosis), fatty infiltration plus inflammation (NASH), fibrosis and ultimately cirrhosis, without excessive alcohol consumption(1). The prevalence of NAFLD was about 17 %−46 % around the world with diagnosis of liver ultrasound(2) and 12·5 %−27·3 % in the general population of China(3). This disease has brought a huge health burden globally(1). Therefore, effective public health measures should be implemented.

A large number of studies have shown that lifestyle factors play key roles in the prevention and treatment of NAFLD, such as non-smoking(4), moderate physical activity(5), a healthy diet(6,7), normal body weight(8), moderate sleep duration(9) and low anxiety level(10). However, most of these studies only explored the association between individual lifestyle factors and NAFLD, thus ignoring the fact that each specific healthy lifestyle factor was capable of coexisting with the others and may result in a synergistic effect on people’s health(11). Therefore, establishing a combined measure of these relevant lifestyle components, such as the Healthy Lifestyle Score (HLS), may be more useful in evaluating synergistic associations than using each single lifestyle behaviour.

Many studies showed that the HLS is associated with CVD(12–14), some cancers(15–17), osteoporosis(18) and other diseases(19). In these studies, HLS normally consisted of the following lifestyles: smoking, body weight or BMI, physical activity, diet, sleep, anxiety, etc. To our knowledge, only one study has explored the association between the healthy lifestyle index (HLI) and fatty liver disease (FLD) among 354 Germans (mean age 67·1 years)(20). In that study, individuals with all four (v. zero) favourable lifestyle factors (never smoking, favourable waist circumference (WC), moderate physical activity and healthy diet) had lower OR values for FLD (0·09; 95 % CI 0·03, 0·30).

However, there are two problems with using the HLI to assess the risk of NAFLD. First, the components of the HLI may be inappropriate. For example, the diet component included alcohol consumption, a key determinant of liver diseases. A study of 653 Chinese individuals showed that alcohol intake ≥20 g/d and drinking duration ≥5 years were associated with greater odds of liver injury (OR: 1·96 (95 % CI 1·12, 3·44) and 3·41 (95 % CI 1·79, 6·51), respectively, P < 0·05)(21). In addition, the HLI did not include other lifestyle factors related to NAFLD, such as passive smoking(4), BMI(8), sleep(9) and anxiety(10). Second, each individual component was treated equally and had the same weight not only in that study but also in many other HLS-related studies, thus ignoring the fact that the strengths of the associations may differ for the different component lifestyle factors(16,22).

To address these issues, this cross-sectional study examined the association of a six-item HLS (non-smoking, normal BMI, physically active, healthy diet pattern, good sleep and no anxiety) with NAFLD in a middle-aged and older Chinese population and explored the optimal weight for each item based on a regression model.

Methods

Study participants

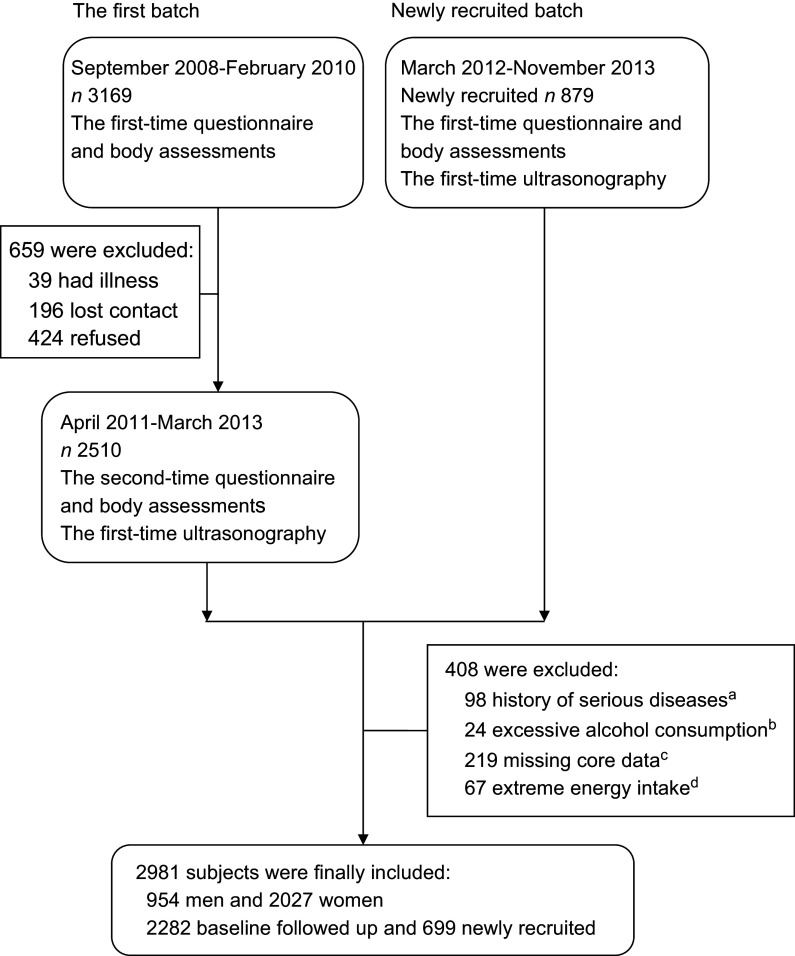

This study was based on the Guangzhou Nutrition and Health Study (GNHS), which is a community-based prospective cohort study designed to assess determinants of common chronic diseases (e.g. osteoporosis, NAFLD, cardiometabolic diseases). Participants (aged 40–75 years old) who had lived in urban Guangzhou for ≥5 years were recruited from 2008 to 2010 (n 3169) and 2012 to 2013 (n 879) using the same criteria. Questionnaire interviews, body assessments and ultrasonography evaluations for NAFLD were conducted among 3389 participants who completed the survey between 2011 and 2013, including 2510 subjects from the first batch and 879 newly recruited subjects. A total of 408 participants were excluded from this study for the following reasons: (1) history of malignancy, hyperthyroidism or viral hepatitis (n 98); (2) excessive alcohol consumption (n 24): ≥30 g/d (men) or ≥20 g/d (women)(1); (3) missing data to calculate HLS or to determine the status of NAFLD (n 219) and (4) extreme energy intake (n 67): <3348 or >17 581 kJ/d (men); <2512 or >14 650 kJ/d (women). Finally, 2981 participants were included in this study (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of participants in the present study. (a) Serious diseases: malignancy, hyperthyroidism or viral hepatitis. (b) Excessive alcohol consumption: ≥30 g/d (men) or ≥20 g/d (women). (c) Core data: data to calculate the Healthy Lifestyle Score or to determine the status of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. (d) Extreme energy intake: <3348 or >17 581 kJ/d (men); <2512 or >14 650 kJ/d (women)

Definition and assessment of the Healthy Lifestyle Score

The HLS in this study consists of six components: non-smoking, normal BMI, physical activity, healthy diet pattern, good sleep and no anxiety. One point was awarded for a healthy status and 0 point for an unhealthy status with respect to each item (Table 1), with a maximum score of six points (higher scores indicate better health). Face-to-face interviews using structured questionnaires(23) and body assessments were used to collect HLS-relevant information and covariates, such as age, sex, marital status, education level, income, history of diseases and drugs (such as statins), and use of oral oestrogen. Smoking included both active (cigarette consumption ≥100 in the last year) and passive smoking (cigarette exposure ≥1/d in the last year). Physical activity referred to moderate or vigorous activity(24). Participants’ heights and weights were measured to calculate BMI (in kg/m2). WC was measured at the widest part of the stomach (across the belly button, just above the hipbones) when participants were standing and just after breathing out. WC below 85 cm (men) or 80 cm (women) was classified as healthy(25). The alternate Mediterranean diet score(26,27) was used to assess the diet. We further modified it by excluding alcohol intake since it was a typical risk factor for liver diseases(21). The modified alternate Mediterranean diet score ranged from 0 to 8 (higher scores indicate better health) and included eight dietary components: whole grains, vegetables (excluding potatoes), fruit (including juices), legumes, nuts, fish, ratio of MUFA to SFA and red or processed meats. Insomnia was defined as having any of the following conditions for more than 6 months prior to the survey: (1) cannot get to sleep within 30 min; (2) wake up early or in the middle of the night and (3) actual sleep time <7 h/night. Anxiety neurosis was assessed using a twenty-item Self-rating Anxiety Scale(28). Each item was given a four-grade score (1–4 points) to assess the frequency of anxiety symptoms. A full standard score of 100 points was then obtained by adding the scores of twenty items and multiplying by 1·25. Participants were classified as normal, mild, moderate and severe anxiety neurosis according to the standard score of <50, 50–59, 60–69 and ≥70, respectively.

Table 1.

Criteria of Healthy Lifestyle Score in the present study

| Lifestyle factors | Score |

|---|---|

| Smoking | |

| No active or passive smoking | 1 |

| Currently active or passive smoking | 0 |

| BMI | |

| 18·5 ≤ BMI < 24·0 kg/m2 | 1 |

| BMI < 18·5 or ≥ 24·0 kg/m2 | 0 |

| Physical activity | |

| Moderate or vigorous physical activity ≥ 150 min/week | 1 |

| Moderate or vigorous physical activity < 150 min/week | 0 |

| Diet | |

| Modified alternate Mediterranean diet score: 5–8 | 1 |

| Modified alternate Mediterranean diet score: 0–4 | 0 |

| Sleep | |

| Did not have insomnia or <6 months | 1 |

| Have insomnia ≥6 months | 0 |

| Anxiety | |

| Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) < 50 | 1 |

| SAS ≥ 50 | 0 |

Assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

NAFLD was evaluated by using abdominal ultrasonography (Doppler sonography machine, Sonoscape SSI-5500) according to Graif’s criteria(29), in which radiologists were blinded to the participants’ information. The reliability was evaluated by repeatedly testing 100 participants, and the results showed great reliability (κ = 0·875, total agreement = 93 %, P < 0·001). The validity was assessed in thirty-four participants using computed tomography by researchers who did not know the ultrasonography results, and the results indicated good validity (κ = 0·691, total agreement = 85 %, P < 0·001).

Statistical analysis

Baseline data were presented as the mean and standard deviation (sd) for continuous variables, and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. All continuous variables followed a normal distribution assessed by the Q-Q plot. ANOVA and the χ 2 test were used to compare differences in baseline data among the five HLS groups as appropriate (we combined HLS groups when the sample size was too small).

Logistic regression was used to estimate OR of NAFLD under two models in all subjects, men and women. Only age and sex were adjusted in model 1. In model 2, marital status, education level, income, history of using statins and daily energy intake were further adjusted. For women, we further adjusted for menopausal age and oral oestrogen use. The statistical power of the logistic model (model 2) was estimated for the calculation of OR by treating HLS as a continuous variable. We also explored the association of each component of HLS with NAFLD by logistic regression under the same two models, and other components of HLS except the one being analysed were further adjusted in model 2.

The sensitivity analyses included the following. (1) Comparison of HLS and weighted HLS (wHLS): a wHLS was calculated based on the standardised β (sβ) values of the six components (weight i = [sβ i /(∑sβ i )] × 6); wHLS was divided into five groups, and the sample size of each group was similar to that of HLS. (2) The stability of the HLS was assessed by excluding each component of HLS in turn and replacing the BMI with WC. (3) The synergy of weaker factors: we calculated HLS weaker factors, which consisted of components that showed little or no association with NAFLD in individual lifestyle factor analysis. SPSS 22.0 (IBM) and PASS 11.0 (NCSS, LLC.) were used to perform the statistical analyses, and a two-sided P-value <0·05 was considered statistically significant in this study.

Results

A total of 2981 subjects (954 men and 2027 women) were included in this study. The mean ages of all subjects, men and women were 60·6, 62·2 and 59·9 years old, respectively, and the prevalence of NAFLD was 50·8 %, 54·0 % and 49·3 %, respectively. With the increase in HLS, participants had higher levels of income, education, physical activity, energy intake, dietary intakes of whole grain, vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts and fish, and adherence to the modified alternate Mediterranean diet score. For women, menopausal age and the proportion of oestrogen use also increased. In contrast, as HLS increased, subjects had lower levels of body weight and BMI and fewer proportions of current smoking, insomnia and anxiety (all P-values < 0·05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of study participants by Healthy Lifestyle Score (HLS)*

| HLS (n = 2981) | P-value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5–6 | |||||||

| Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | ||

| n | 238 | 718 | 984 | 753 | 288 | ||||||

| % | 8.0 | 24.1 | 33.0 | 25.2 | 9.7 | ||||||

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Men (n = 954) | |||||||||||

| n | 36 | 235 | 342 | 235 | 106 | ||||||

| % | 15.1 | 32.7 | 34.8 | 31.2 | 36.8 | ||||||

| Age (years) | 60.4 | 6.2 | 60.8 | 6.0 | 60.8 | 6.1 | 60.4 | 5.5 | 60.3 | 5.3 | 0.375 |

| Body weight (kg) | 59.3 | 8.2 | 60.1 | 9.6 | 59.4 | 9.9 | 58.3 | 9.5 | 58.1 | 9.0 | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.8 | 2.9 | 24.2 | 3.0 | 23.5 | 3.0 | 22.8 | 2.7 | 22.1 | 2.3 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 87.5 | 9.0 | 86.4 | 8.4 | 84.6 | 8.5 | 83.2 | 8.1 | 81.6 | 7.4 | 0.062 |

| Household income | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| <2000 Yuan/month per person | 60 | 25.2 | 127 | 17.7 | 151 | 15.3 | 110 | 14.6 | 43 | 14.9 | |

| 2000–3000 Yuan/month per person | 100 | 42.0 | 255 | 35.5 | 416 | 42.3 | 299 | 39.7 | 111 | 38.5 | |

| >3000 Yuan/month per person | 78 | 32.8 | 336 | 46.8 | 417 | 42.4 | 344 | 45.7 | 134 | 46.5 | |

| Education (years) | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| <9 | 101 | 42.4 | 232 | 32.3 | 259 | 26.3 | 165 | 21.9 | 50 | 17.4 | |

| 9–12 | 107 | 45.0 | 346 | 48.2 | 465 | 47.3 | 371 | 49.3 | 150 | 52.1 | |

| >12 | 30 | 12.6 | 140 | 19.5 | 260 | 26.4 | 217 | 28.8 | 88 | 30.6 | |

| Married | 202 | 84.9 | 643 | 89.6 | 874 | 88.8 | 665 | 88.3 | 253 | 87.8 | 0.394 |

| History of using statins | 40 | 16.8 | 105 | 14.6 | 116 | 11.8 | 85 | 11.3 | 35 | 12.2 | 0.087 |

| Smoker† | 169 | 71.0 | 394 | 54.9 | 292 | 29.7 | 96 | 12.7 | 0 | 0.0 | <0.001 |

| Physical activity‡ (min/week) | 52.8 | 125 | 105 | 200 | 201 | 251 | 321 | 261 | 449 | 246 | <0.001 |

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 1430 | 390 | 1523 | 425 | 1585 | 466 | 1660 | 461 | 1799 | 479 | <0.001 |

| Components of modified aMed score | |||||||||||

| Whole grains§ (g/d) | 2.9 | 3.2 | 4.76 | 13.9 | 5.2 | 13.1 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 6.51 | 5.6 | 0.003 |

| Vegetables (excluded potatoes) (g/d) | 22.9 | 9.1 | 24.8 | 10.8 | 26.8 | 11.8 | 30.7 | 12.1 | 34.8 | 13.7 | <0.001 |

| Fruits (included juices) (g/d) | 17.2 | 11.0 | 19.2 | 18.6 | 21.7 | 29.1 | 25.5 | 14.0 | 29.2 | 14.1 | <0.001 |

| Legumes|| (g/d) | 3.7 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 5.7 | <0.001 |

| Nuts (g/d) | 2.4 | 5.8 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Fish (g/d) | 10.7 | 22.1 | 10.5 | 7.6 | 12.2 | 19.1 | 13.2 | 10.3 | 16.2 | 12.3 | <0.001 |

| MUFA/SFA | 1.4 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.808 |

| Red and processed meats (g/d) | 30.1 | 25.5 | 29.9 | 16.8 | 30.3 | 16.4 | 29.8 | 19.5 | 28.9 | 16.7 | 0.668 |

| High adherence of modified aMed score | 17 | 7.1 | 104 | 14.5 | 324 | 32.9 | 488 | 64.8 | 288 | 100.0 | <0.001 |

| Insomnia¶ | 69 | 29.0 | 59 | 8.2 | 39 | 4.0 | 11 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety neurosis** | 116 | 48.7 | 104 | 14.5 | 69 | 7.0 | 14 | 1.9 | 0 | 0.0 | <0.001 |

| Ultrasound-based NAFLD | 142 | 59.7 | 409 | 57.0 | 505 | 51.3 | 355 | 47.1 | 104 | 36.1 | <0.001 |

| Women | |||||||||||

| Menopause age (years) | 46.5 | 12.6 | 48.9 | 8.1 | 48.7 | 8.7 | 48.7 | 8.6 | 48.9 | 9.1 | 0.005 |

| Oestrogen user | 10 | 5.2 | 20 | 4.3 | 45 | 7.2 | 38 | 7.5 | 20 | 10.5 | 0.035 |

Modified aMed score, modified alternate Mediterranean diet score; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Continuous variables were presented as mean and sd, while categorical variables as frequency and percentage. The differences in baseline data among HLS groups were tested by ANOVA or the χ 2 test as appropriate.

Smoking included both active (cigarettes consumption ≥ 100 in the past year) and passive (cigarettes exposure ≥ 1/d in the past year).

Physical activity included middle and vigorous activities during occupation, leisure time and household chores.

Refers to non-refined cereals, such as graham bread, oats, cereal flakes, etc., calculated as dry weight.

Values were calculated and expressed as proteins.

Subjects who had insomnia for more than 6 months.

Subjects whose Self-Rating Anxiety Scale ≥ 50.

In all subjects (Table 3), higher HLS was inversely associated with NAFLD after adjusting for age and sex in model 1. The OR of NAFLD for subjects with higher HLS (3, 4, 5–6 v. 0–1 points) were 0·68 (95 % CI 0·51, 0·91), 0·58 (95 % CI 0·43, 0·79) and 0·37 (95 % CI 0·26, 0·52), respectively (all P-values < 0·05). The same trends were observed in model 2, with corresponding OR of 0·68 (95 % CI 0·51, 0·91), 0·58 (95 % CI 0·43, 0·78) and 0·35 (95 % CI 0·25, 0·51), respectively (all P-values < 0·05), with a power of almost 100 % at a 0·05 significance level. In the sex-stratified analysis, the inverse association was only found in women, in which the corresponding OR (model 2) of NAFLD for subjects with higher HLS (3, 4, 5–6, v. 0–1 points) were 0·51 (95 % CI 0·34, 0·77), 0·44 (95 % CI 0·28, 0·67) and 0·25 (95 % CI 0·15, 0·41), respectively (Table 3). Among the six individual components of HLS, only normal BMI (OR 0·30) and physical activity (OR 0·81) were significantly associated with a lower likelihood of NAFLD in model 2 (P-values < 0·05) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression estimated OR (95 % CI) for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by Healthy Lifestyle Score (HLS) in all subjects, men and women

| Exposures | n (total/cases) | Model 1* | Model 2† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | P-value | OR | 95 % CI | P-value | ||

| All subjects | 2981/1515 | ||||||

| HLS 0–1 | 238/142 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| HLS 2 | 718/409 | 0·86 | 0·64, 1·16 | 0·327 | 0·85 | 0·63, 1·15 | 0·281 |

| HLS 3 | 984/505 | 0·68 | 0·51, 0·91 | 0·010 | 0·68 | 0·51, 0·91 | 0·010 |

| HLS 4 | 753/355 | 0·58 | 0·43, 0·79 | <0·001 | 0·58 | 0·43, 0·78 | <0·001 |

| HLS 5–6 | 288/104 | 0·37 | 0·26, 0·52 | <0·001 | 0·35 | 0·25, 0·51 | <0·001 |

| Men | 954/515 | ||||||

| HLS 0–1 | 36/18 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| HLS 2 | 235/140 | 1·45 | 0·72, 2·94 | 0·300 | 1·33 | 0·65, 2·75 | 0·440 |

| HLS 3 | 342/190 | 1·24 | 0·62, 2·47 | 0·543 | 1·21 | 0·59, 2·45 | 0.604 |

| HLS 4 | 235/122 | 1·07 | 0·53, 2·17 | 0·847 | 1·03 | 0·50, 2·13 | 0·936 |

| HLS 5–6 | 105/45 | 0·76 | 0·35, 1·62 | 0·472 | 0·69 | 0·32, 1·52 | 0·362 |

| Women | 2027/1000 | ||||||

| HLS 0–1 | 202/124 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| HLS 2 | 483/269 | 0·78 | 0·56, 1·10 | 0·155 | 0·74 | 0·48, 1·15 | 0·180 |

| HLS 3 | 642/315 | 0·60 | 0·44, 0·83 | 0·002 | 0·51 | 0·34, 0·77 | 0·001 |

| HLS 4 | 518/233 | 0·52 | 0·37, 0·72 | <0·001 | 0·44 | 0·28, 0·67 | <0·001 |

| HLS 5–6 | 182/59 | 0·32 | 0·21, 0·48 | <0·001 | 0·25 | 0·15, 0·41 | <0·001 |

Ref., Reference category.

Model 1: adjusted for age and sex (for all subjects only).

Model 2: further adjusted for marital status, education level, household income, history of using statins and daily energy intake. For women, menopausal age and oral oestrogen use were further adjusted.

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regression estimated OR (95 % CI) for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by individual lifestyle factors in all subjects, men and women*

| All subjects (n † = 2981/1515) | Men (n 954/515) | Women (n 2027/1000) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | OR | 95 % CI | P-value | n | OR | 95 % CI | P-value | n | OR | 95 % CI | P-value | |

| No smoking | ||||||||||||

| No | 951/499 | Ref. | 432/243 | Ref. | 519/256 | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 2030/1016 | 0·94 | 0·80, 1·11 | 0·464 | 522/272 | 0·94 | 0·72, 1·24 | 0·676 | 1508/744 | 0·93 | 0·73, 1·19 | 0·575 |

| Standard BMI (18·5 ≤ BMI < 24·0 kg/m2) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1084/708 | Ref. | 87/63 | Ref. | 997/645 | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 1897/807 | 0·30 | 0·25, 0·36 | <0·001 | 867/452 | 0·37 | 0·22, 0·61 | <0·001 | 1030/355 | 0·28 | 0·23, 0·35 | <0·001 |

| Physically active (moderate or vigorous physical activity ≥ 150 min/week) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1581/846 | Ref. | 532/309 | Ref. | 1049/537 | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 1400/69 | 0·81 | 0·69, 0·94 | 0·006 | 422/206 | 0·64 | 0·49, 0·84 | <0·001 | 978/463 | 0·87 | 0·71, 1·08 | 0·211 |

| Healthy diet pattern (modified aMed score: 5–8) | ||||||||||||

| No | 1760/895 | Ref. | 619/333 | Ref. | 1141/552 | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 1221/620 | 0·88 | 0·74, 1·03 | 0·105 | 335/182 | 0·91 | 0·68, 1·21 | 0·505 | 886/448 | 0·87 | 0·70, 1·09 | 0·226 |

| Good sleep (no insomnia or <6 months) | ||||||||||||

| No | 178/91 | Ref. | 42/23 | Ref. | 136/69 | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 2803/1424 | 0·73 | 0·53, 1·00 | 0·054 | 912/492 | 0·75 | 0·39, 1·45 | 0·391 | 1891/931 | 0·92 | 0·54, 1·56 | 0·743 |

| No anxiety (Self-Rating Anxiety Scale <50) | ||||||||||||

| No | 303/160 | Ref. | 60/27 | Ref. | 243/133 | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 2678/1355 | 0·92 | 0·72, 1·19 | 0·543 | 594/488 | 1·65 | 0·94, 2·88 | 0·080 | 1784/867 | 0·75 | 0·53, 1·06 | 0·103 |

Modified aMed score, modified alternate Mediterranean diet score; Ref., Reference category.

All analyses were adjusted for age, sex (for all subjects only), marital status, education level, household income, history of using statins, daily energy intake and other factors of Healthy Lifestyle Score. For women, menopausal age and oral oestrogen use were further adjusted.

The number of total subjects and NAFLD cases, expressed as total/cases.

Weighted HLS was calculated according to the standardised regression beta for each individual item with NAFLD. BMI and physical activity contributed most to the wHLS with weights of 3·94 and 0·73, and the weights of the other four items ranged from 0·15 (anxiety) to 0·52 (insomnia) (online Supplementary Table 1). The associations of wHLS with the presence of NAFLD tended to be stronger than those of HLS. The OR of NAFLD were 0·37, 0·30 and 0·23 for the higher wHLS groups (3, 4, 5 v. 1 points) in model 2 (all P-values < 0·001). The sensitivity analyses showed that the beneficial associations between HLS and NAFLD remained after excluding each component in turn, excluding the two most significant factors (BMI and physical activity), or replacing BMI with WC (P-values < 0·05) (online Supplementary table 2).

Discussion

The six-item HLS was inversely associated with NAFLD in this middle-aged and older Chinese population. BMI and physical activity were two key contributors to the association. The OR for NAFLD of weighted HLS were lower than those of HLS consisting of equal weight components. These results suggested that subjects with better adherence to a healthy lifestyle pattern (non-smoking, normal BMI, physically active, a healthy diet, good sleep and no anxiety) might have a lower risk of NAFLD, and a high weighted HLS may lead to more benefits than a high unweighted HLS.

Healthy Lifestyle Score and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Previous studies have explored the relationship between individual lifestyle factors and NAFLD(4–10); however, few studies have reported associations between synergistic lifestyle scores and NAFLD. To the best of our knowledge, only one cross-sectional study (including 354 Germans aged 67·1 years old) has examined the association of the HLI with FLD.(20) The HLI consisted of smoking, WC, physical activity and diet and ranged from 0 to 4 points (higher scores indicate better health). Consistent with our results, the study suggested an inverse association between HLI and FLD. The OR of FLD for subjects who had high HLI (2, 3 and 4 points) were 0·35 (95 % CI 0·16–0·80), 0·25 (95 % CI 0·10–0·61) and 0·09 (95 % CI 0·03–0·30), respectively.

However, the HLI may be inappropriate for assessing the risk of NAFLD since it included alcohol intake in the diet component and did not include several other NAFLD-related factors (such as BMI(8), sleep(9) and anxiety(10)). Therefore, we calculated a more comprehensive HLS by including six items (non-smoking, normal BMI, physical activity, healthy diet pattern, good sleep and no anxiety). Our results showed that the inverse association of this six-item HLS with NAFLD was robust and stable even after excluding each component in turn or replacing BMI with WC (which was a component of HLI), suggesting that it may be appropriate for the risk assessment of NAFLD (online Supplementary Table 2).

Given that each lifestyle factor may have a different association with NAFLD, simply giving equal weight to the six items of HLS may lead to misclassification. To address this issue, a weighted HLS was constructed by weighting each component based on its sβ in this study. The results showed that BMI and physical activity had the highest weights, and the OR of NAFLD in the higher weighted HLS group were lower than the OR in the higher HLS group (online Supplementary Table 2). These results suggested that the different impacts of each lifestyle factor on NAFLD should also be taken into consideration when calculating the HLS.

Healthy Lifestyle Score components and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

BMI and physical activity played key roles in the inverse association of the HLS with NAFLD among the six HLS components, which was consistent with previous studies. A cross-sectional study involving 218 men aged 33–73 years indicated that the prevalence of NAFLD significantly increased with increasing BMI categories (kg/m2) (18·5 ≤ BMI < 25·0: 1·7 %, 25·0 ≤ BMI < 30·0: 9·2 % and 30·0 ≤ BMI: 20·5 %, P = 0·002)(30). A study of 18 507 Chinese individuals aged 71·4 ± 14·2 years showed that people with NAFLD had a higher BMI (kg/m2) than those without NAFLD (25·65 v. 24·33, P < 0·05)(31). Another retrospective study (including 1994 Chinese individuals aged 18–87 years) also showed similar results regarding the association between BMI (kg/m2) and NAFLD (26·31 in NAFLD group v. 22·54 in no-NAFLD group, P < 0·05)(8). People with high BMI normally have high fat consumption, which increases the synthesis of liver TAG and decreases the synthesis of very LDL. These lipid metabolic disorders can lead to an increase in fatty tissue and free fatty acids, which in turn can damage liver cells and ultimately lead to NAFLD. In addition, hyperinsulinaemia and insulin resistance are common in obese patients, and an increase in insulin can promote the synthesis of TAG, leading to the occurrence of NAFLD(32).

A cross-sectional study (n 349) showed that people with NAFLD participated in less resistance physical activity than people without NAFLD (13 % v. 23 %, P = 0·03), and the prevalence of NAFLD was higher for those engaging in resistance physical activity less than once a week than for those engaging at least once a week (33·9 % v. 18·8 %, P < 0·01)(33). Another study also suggested an inverse association between fitness categories (metabolic equivalent) and the prevalence of NAFLD (metabolic equivalent < 10·2: 20·8 %, 10·2 ≤ metabolic equivalent < 11·8: 9·6 % and 11·8 ≤ metabolic equivalent: 2·7 %, P = 0·002)(30). The mechanism of the beneficial effect of exercise can be concluded as a reduction in weight, liver enzymes, hepatic TAG, visceral adipose tissue volume and plasma free fatty acids(34–36) or an increase in insulin sensitivity and glucose homoeostasis(37).

Interestingly, we did not find associations of non-smoking, healthy diet pattern, good sleep and no anxiety with NAFLD in this study, although previous studies have shown inverse relationships of these four lifestyle factors with NAFLD(4,6,7,9,10) (Table 4). However, in sensitivity analyses, we found a significant synergistic association of HLS consisting of the four lifestyle factors with the presence of NAFLD (online Supplementary Table 2). This finding may be due to the synergistic effect of different components of the HLS, which enables the synergistic association of these factors to be greater than that of each part. Our findings emphasised the importance of a combined health lifestyle pattern for liver protection instead of just a single lifestyle choice.

Strengths and limitations

Several strengths of this study can be concluded. First, the sensitivity analyses showed a robust and stable inverse association between HLS and NAFLD, suggesting good internal consistency for the HLS evaluated. Second, the sample size of our study (n 2981) was relatively larger than that of a previous similar study (n 354)(20).

There are also some limitations that need to be noted. First, the data of five out of six HLS components (smoking, physical activity, diet, sleep and anxiety) were obtained by the questionnaire, and recall bias could not be completely excluded in our study. However, we conducted a face-to-face interview with the help of pictures of foods instead of self-reported questionnaires to reduce the bias. Second, the cross-sectional study design limits the possibility of inferring causality between HLS and NAFLD. However, typically, the associations will tend to be attenuated but not overestimated since healthier lifestyles would be recommended to the participants with NAFLD. Third, the validity of the physical activity questionnaire could not be obtained in this study, although the questionnaire had good long-term reliability (r 0·646, P < 0·001) between surveys conducted during 2008–2010 and 3 years later for the first batch subjects. Fourth, the sleep data were assessed by simply asking whether subjects had insomnia instead of using systematic questionnaires such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Finally, the diagnostic method of NAFLD was ultrasonography in this study, which is not the gold standard (liver biopsy). However, the reliability (κ = 0·875) and validity (κ = 0·691) of ultrasonography in this study were high, and its sensitivity (84 %) and specificity (95 %) were acceptable according to a study in the USA(38).

In conclusion, there was an inverse association between the six-item HLS and NAFLD in this middle-aged and older Chinese population, and BMI and physical activity played key roles in the association. The inverse association was more significant after weighting the HLS. Our findings suggested that a healthy lifestyle pattern (non-smoking, normal BMI, physically active, healthy diet pattern, good sleep and no anxiety) might decrease the risk of NAFLD in this population. HLS-based prospective and interventional studies are needed to address the causality problem.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to other team members for their contributions in recruiting participants, conducting face-to-face interviews and collecting data. Financial support: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82073546 and 81773416), the Zhendong Physical Fitness and Health Research fund of the Chinese Nutrition Society (No. CNS-ZD2019049), the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (SZSM201611068) and the 5010 Program for Clinical Researches by the Sun Yat-Sen University (No. 2007032). All funders were used in the progress of study design, conduct of the study, analysis of samples or data, interpretation of findings and the preparation of the manuscript. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: Y.-y. D. and Q.-w. Z. contributed equally to this article. Y.-m. C. conceived and designed the study; Y.-m. C. and Y.-b. K. critically revised the manuscript; Y.-y. D. analysed the data and wrote the paper; Q.-w. Z., H.-l. Z. and F. X. collected the data. Y.-m. C. obtained the fundings. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Health at Sun Yat-sen University. Written informed consents were obtained from all subjects. This study has been registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03179657).

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021000902.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Anstee QM, Targher G & Day CP (2013) Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 10, 330–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE et al. (2012) The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology 142, 1592–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fan J-G (2013) Epidemiology of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 28, 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu Y, Dai M, Bi Y et al. (2013) Active smoking, passive smoking, and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a population-based study in China. J Epidemiol 23, 115–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zelber-Sagi S (2011) Nutrition and physical activity in NAFLD: an overview of the epidemiological evidence. World J Gastroenterol 17, 3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xiao M-L, Lin J-S, Li Y-H et al. (2020) Adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet is associated with lower presence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged and elderly adults. Public Health Nutr 23, 674–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhong Q-w, Wu Y-y, Xiong F et al. (2020) Higher flavonoid intake is associated with a lower progression risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: a prospective study. Br J Nutr. Published online: 27 July 2020. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520002846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tang Z, Pham M, Hao Y et al. (2019) Sex, age, and BMI modulate the association of physical examinations and blood biochemistry parameters and NAFLD: a retrospective study on 1994 cases observed at Shuguang hospital, China. Biomed Res Int 2019, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okamura T, Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M et al. (2019) Short sleep duration is a risk of incident nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based longitudinal study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 28, 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Youssef NA, Abdelmalek MF, Binks M et al. (2013) Associations of depression, anxiety and antidepressants with histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int 33, 1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reeves MJ & Rafferty AP (2005) Healthy lifestyle characteristics among adults in the United States, 2000. Arch Intern Med 165, 854–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Y, Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P et al. (2011) Lifestyle factors in relation to heart failure among Finnish men and women. Circ Heart Fail 4, 607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Djousse L, Driver JA & Gaziano JM (2009) Relation between modifiable lifestyle factors and lifetime risk of heart failure. JAMA 302, 394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larsson SC, Tektonidis TG, Gigante B et al. (2016) Healthy lifestyle and risk of heart failure: results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Circ Heart Fail 9, e002855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buckland G, Travier N, Huerta JM et al. (2015) Healthy lifestyle index and risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in the EPIC cohort study. Int J Cancer 137, 598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiao L, Mitrou PN, Reedy J et al. (2009) A combined healthy lifestyle score and risk of pancreatic cancer in a large cohort study. Arch Intern Med 169, 764–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arthur R, Kirsh VA, Kreiger N et al. (2018) A healthy lifestyle index and its association with risk of breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancer among Canadian women. Cancer Causes Control 29, 485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deng Y-y, Liu Y-p, Ling C-w et al. (2020) Higher healthy lifestyle scores are associated with greater bone mineral density in middle-aged and elderly Chinese adults. Arch Osteoporos 15, 129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leong TI, Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA et al. (2018) Longitudinal associations of the healthy lifestyle index score with quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis: a prospective cohort study. Front Neurol 9, 874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koch M, Borggrefe J, Schlesinger S et al. (2015) Association of a lifestyle index with MRI-determined liver fat content in a general population study. J Epidemiol Community Health 69, 732–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhe S, Li Y-M, Yu C-H et al. (2008) Risk factors for alcohol-related liver injury in the island population of China: A population-based case-control study. World J Gastroenterol 14, 2255–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Falcón LM et al. (2015) A healthy lifestyle score is associated with cardiometabolic and neuroendocrine risk factors among Puerto Rican adults. J Nutr 145, 1531–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang CX & Ho SC (2009) Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency Questionnaire among Chinese women in Guangdong province. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 18, 240–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization (2020) Global recommendations on physical activity for health; available at https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/ (accessed October 2020).

- 25. Zhou B (2002) Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference to risk factors of related diseases in Chinese adult population. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 23, 5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fung TT, McCullough ML, Newby PK et al. (2005) Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr 82, 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mitrou PN, Kipnis V, Thiebaut AC et al. (2007) Mediterranean dietary pattern and prediction of all-cause mortality in a US population: results from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Arch Intern Med 167, 2461–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zung WW (1971) A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12, 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Graif M, Yanuka M, Baraz M et al. (2000) Quantitative estimation of attenuation in ultrasound video images: correlation with histology in diffuse liver disease. Invest Radiol 35, 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Church TS, Kuk JL, Ross R et al. (2006) Association of cardiorespiratory fitness, body mass index, and waist circumference to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 130, 2023–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu M, Wang J, Zeng J et al. (2017) Association of NAFLD with diabetes and the impact of BMI changes: a 5-year cohort study based on 18,507 elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102, 1309–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang S, Zhang J, Zhang J et al. (2020) A cohort study on the correlation between body mass index trajectories and new-onset non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 28, 597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zelber-Sagi S, Nitzan-Kaluski D, Goldsmith R et al. (2008) Role of leisure-time physical activity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based study. Hepatology 48, 1791–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baba CS, Alexander G, Kalyani B et al. (2006) Effect of exercise and dietary modification on serum aminotransferase levels in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 21, 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnson NA, Sachinwalla T, Walton DW et al. (2009) Aerobic exercise training reduces hepatic and visceral lipids in obese individuals without weight loss. Hepatology 50, 1105–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. St. George A, Bauman A, Johnston A et al. (2009) Independent effects of physical activity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 50, 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boulé NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP et al. (2001) Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. JAMA 286, 1218–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R et al. (2004) Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology 40, 1387–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021000902.

click here to view supplementary material