Abstract

Background:

Children with cancer from rural and non-urban areas face unique challenges. Health equity for this population requires attention to geographic disparities in optimal survivorship-focused care.

Methods:

The Oklahoma Childhood Cancer Survivor Cohort was based on all patients reported to the institutional cancer registry and ≤18-years-old at diagnosis between January 1, 2005, and September 24, 2014. Suboptimal follow-up was defined as no completed oncology-related clinic visit five to seven years after their initial diagnosis (survivors were 7–25 years old at end of the follow-up period). The primary predictor of interest was rurality.

Results:

Ninety-four (21%) of the 449 eligible survivors received suboptimal follow-up. There were significant differences (p=0.01) as 36% of survivors from large towns (n=28/78) compared with 21% (n=20/95) and 17% (n=46/276) of survivors from small town/isolated rural and urban areas received suboptimal follow-up, respectively. Forty-five percent of adolescents at diagnosis were not seen in the clinic compared with 17% of non-adolescents (p<0.01). An adjusted risk ratio of 2.2 (95% CI 1.5, 3.2) was observed for suboptimal follow-up among survivors from large towns, compared with survivors from urban areas. Seventy-three percent of survivors (n=271/369) had a documented survivorship care plan with similar trends by rurality.

Conclusions:

Survivors from large towns and those who were adolescents at the time of diagnosis were more likely to receive suboptimal follow-up care compared to survivors from urban areas and those diagnosed younger than thirteen.

Impact:

Observed geographic disparities in survivorship care will inform interventions to promote equitable care for survivors from non-urban areas.

Keywords: Late Effects from Childhood Cancer, Survivorship, Clinical Research Informatics, Rural Health

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 500,000 adult survivors of childhood cancer live in the United States and, with therapeutic advances pushing five-year survival rates in recent years to 85%, the number will undoubtedly continue to grow.1 The recognition of late effects and risk-adapted treatment strategies, notably for leukemia and lymphoma therapy, in recent decades resulted in a decreased burden of late chronic conditions.2,3 Nevertheless, the cure comes at a cost with severe chronic health conditions occurring in over a quarter of survivors and considerable excess mortality from subsequent malignancies and cardiovascular disease.4–9 The heterogeneity of pediatric malignancies, associated treatment exposures, and subsequent comorbidities for survivors call for risk-adapted therapy to optimize lifelong health for survivors.10 Moreover, survivors from non-urban areas may face additional unique challenges and barriers to equitable survivorship care.

Guidelines and survivorship care plans offer comprehensive tools for clinicians and survivors to support optimal care delivery. The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Long-Term Follow-up Guidelines are regularly updated and efforts such as the International Guideline Harmonization Group (IGHG) help synthesize the growing body of evidence on late effects with the goal to improve care.11–13 Survivorship care plans, such as Passport for Care (PFC), serve as tools to promote patient education and the diverse care delivery models reflect the creative approaches to meet the needs of this burgeoning population.14 Nevertheless, nearly a third of survivors receive suboptimal follow-up in the early survivorship period, which worsens dramatically as 70% of adult survivors of childhood cancer report no survivorship-focused care.15,16 This decline in optimal care coincides with the progressive cumulative incidence of life-threatening late effects, such as heart failure and breast cancer, during the young adult years.17,18

Oklahoma is a highly rural state with a high burden of chronic health conditions and survivors from non-urban areas face unique challenges for optimal survivorship-focused care. Thirty-four percent of residents live in rural areas in 2019, more than twice the national average of 14%.19 Rural disparities in the general population represent an important public health challenge.20 For survivors, hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors potentiate risk for cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease from anthracyclines and radiation, thus highlighting the critical need to engage high-risk survivors in care to mitigate rural health inequities later in life.21 Rural-urban differences in the general population for diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality portend even graver consequences for childhood cancer survivors at risk for late effects.22–24 In the adult literature, rurality has been associated with poor health status and inadequate care among survivors of adult cancers.25–27 Transportation barriers and distance to tertiary care centers, which contribute to disparities while on active treatment in pediatric oncology, may also adversely impact optimal survivorship care.28,29 Follow-up care patterns and potential disparities for those from non-urban areas represent key gaps to care for this vulnerable population.

This study aimed to assess the impact of rurality on suboptimal subspecialty follow-up during the early survivorship period through the integration of cancer registry, electronic health records, and geospatial data. We hypothesized that survivors from non-urban areas would be more likely to receive suboptimal subspecialty follow-up care. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of survivors with a survivorship care plan, generated through Passport for Care, by rurality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survivor Cohort Construction

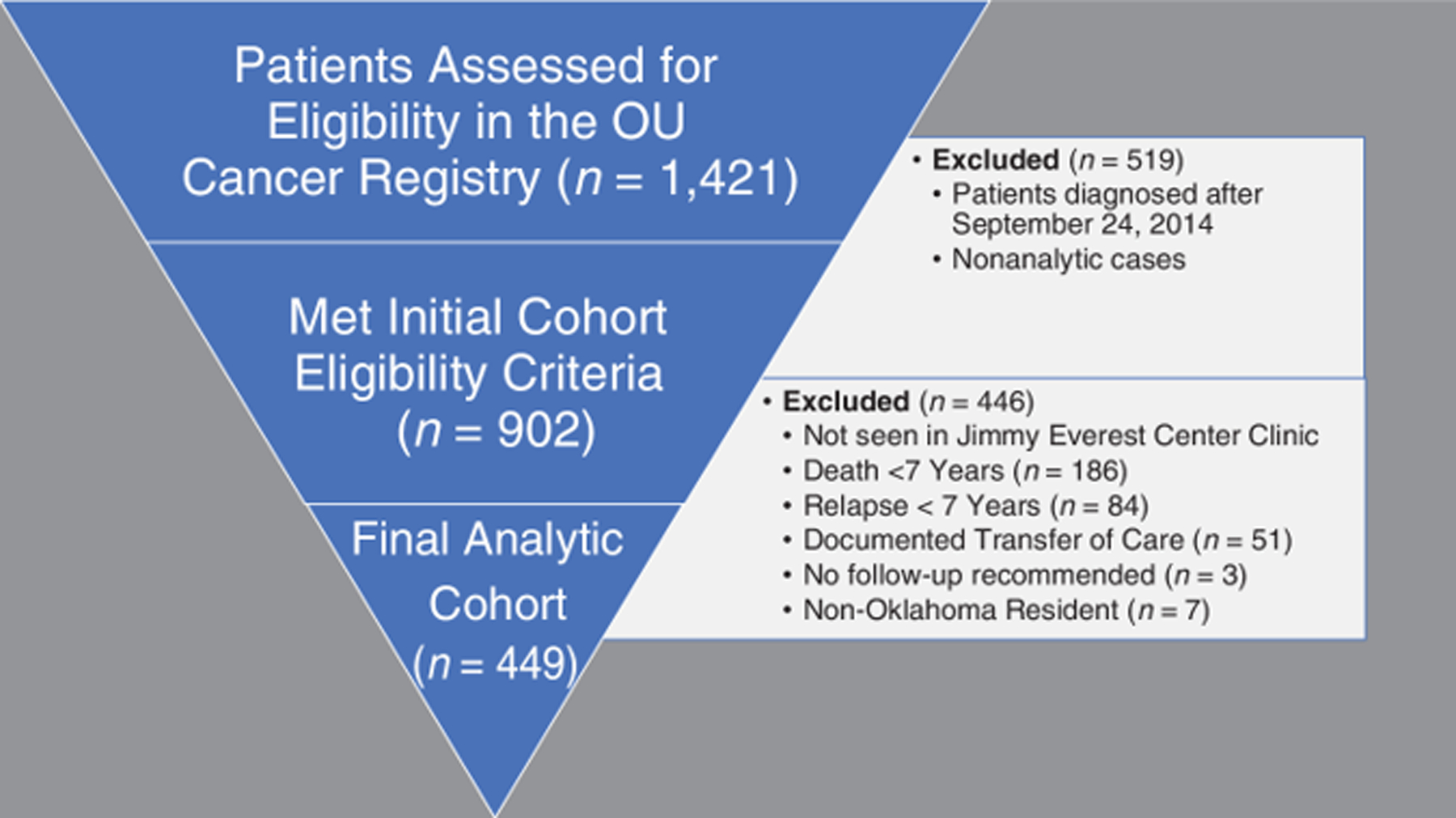

The University of Oklahoma institutional cancer registry was used as the base cohort for this analysis. The Cancer Registries Amendment Act of 1992 established federal support and standards for cancer registries across the United States.30 Over the last several decades, the National Cancer Database (NCDB), in conjunction with the Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society, provides rigorous data standards and captures greater than 70% of new diagnoses of cancer annually.31 Age at diagnosis, sex, primary diagnosis, the first course of treatment, demographic data, including the address at diagnosis, mortality, and recurrence data are all documented by trained cancer registrars. At Oklahoma Children’s Hospital, the cancer registry reliably includes new diagnoses of pediatric cancer since 2005, thus patients ≤18-years-old diagnosed after January 1, 2005, were considered for the full cohort (n=1421). Patients diagnosed after September 24, 2014, those not seen in the pediatric oncology clinic at the Jimmy Everest Center (JEC) within a year of diagnosis, non-analytic cases (those not diagnosed or receiving the first course of treatment at the institution), and those with documented death within seven years of their initial diagnosis were excluded from the analysis. Survivors with documented relapse were also excluded to focus on those off therapy or the early survivorship period. Subsequent malignant neoplasms were not excluded, as this was not routinely captured by the cancer registry. The age range of survivors at the end of the seven-year follow-up period was 7–25 years old. For the secondary analysis focused on the documentation of a survivorship care plan, we also excluded patients with a history of a primary central nervous system (CNS) tumor as they were not routinely entered into PFC. Documentation of a survivorship care plan was validated through the institutional log-in for the Passport for Care website. This research was submitted to and approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB#: 13687) on September 22, 2021.

Disease Classification and Late Effects Risk Strata

The cancer registry defines the primary malignancy by the International Classification of Diseases Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3), which facilitates additional categorization based on the International Classification of Childhood Cancer, third edition (ICCC-3).32 Major pediatric oncology disease categories were used to implement late effects risk stratification developed by the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.33 Primary diagnosis and dichotomous treatment exposures, as captured in the cancer registry, were utilized to identify survivors as low, moderate, and high risk for late effects. The full methodology for this was documented previously.15

EHR Data Elements

The University of Oklahoma Clinical Research Data Warehouse (CRDW) integrates data from multiple clinical sources across the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. For patients meeting the inclusion criteria, details were extracted using standard query language (SQL) for all clinic visits at the JEC and the Stephenson Cancer Center (SCC) for each patient in the cancer registry as the base cohort. A valid completed visit was defined as a visit that was scheduled, the patient arrived, and the visit was subsequently closed at the end of the encounter. Additionally, we limited to provider visits (e.g. laboratory-only or nurse-only visits were not considered a valid completed visit for the purposes of this analysis). These dates were landmarked to the initial date of diagnosis, as documented in the cancer registry. Optimal follow-up was defined as a completed clinic visit at the JEC or the SCC during a two-year period between five and seven years (60–84 months) after the initial diagnosis. Race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, American Indian or Other. For each patient, follow-up was assessed with informatics methods on structured database fields; valid completed clinic visits were identified in this first pass. If this approach did not recognize an oncology-related visit between five and seven years, a manual chart review was performed. Of the 152 survivors without a valid clinic visit in the follow-up window, 51 had a documented transfer of care to another institution and three were not recommended to follow-up.

Geocoded Data Elements

The primary association of interest was rurality, defined as urban, large town, small town/isolated rural based on the 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes, which consider population density and distance to nearest urban centers (Supplemental Table 1).34,35 The primary urban centers in Oklahoma are the Oklahoma City area, Tulsa, and Lawton. We geocoded patient addresses at the time of diagnosis using the Texas A&M Geocoding Service ESRI Toolbox.36 We joined the addresses to the 2010 US census tract TIGER/Line shapefiles,37 which were then joined to the appropriate census tract-level RUCA codes.35

Additional geographic variables included the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), distance to the medical center, and travel time to the medical center. We obtained the 2019 ADI from the Neighborhood Atlas ® at the census block group level and used the national rankings to classify patients into quartiles (<25%, 25–49%, 50–74%, and 75–100%).38,39 To calculate the distance and travel time from the patient’s residence to the medical center, we used the Origin-Destination Cost Matrix Tool in ArcMap, accounting for road networks. All geospatial analyses were conducted in ArcMap 10.8.1 (ESRI, Redlands, CA).

Statistical analyses

The primary outcome of interest was a completed oncology-related clinic visit at either the JEC or SCC between five and seven years after the initial diagnosis, thus categorized as a dichotomous variable. Continuous variables were presented as means or medians, as appropriate based on distribution, and differences between those with and without optimal follow-up were analyzed using the t-test. Categorical variables, such as rurality, race/ethnicity, sex, adolescent at diagnosis, late effects risk strata, primary diagnosis, and PFC, were presented as proportions and differences were assessed using the χ2 test.

To calculate risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), we used modified Poisson regression due to challenges with convergence in the log-binomial model. In this model, we assumed that the data follow an underlying Poisson distribution, although our outcome was binomial. Standard Poisson regression can lead to overdispersion in binomial data, which can result in the overestimation of the standard error. Modified Poisson regression uses the sandwich estimator to correct for any overestimation of the standard error.40–42 We used a directed acyclic graph (DAG) to guide the selection of confounders, with race/ethnicity being the only variable necessary to include in the multivariable models to remove confounding.43,44 (Supplemental Figure 1). Using a DAG allowed us to visualize the causal relationships between variables to determine which variables may confound the relationship between rurality and optimal follow-up without introducing selection bias (i.e., collider stratification bias), over adjustment (i.e., adjusting for a mediator), or unnecessary adjustment (i.e., adjusting for variables that do not introduce bias, but impact precision).45,46 We considered race/ethnicity, adolescent at diagnosis, ADI, sex, primary diagnosis, late effects risk stratification, and year of diagnosis as potential confounders or mediators on the pathway to suboptimal follow-up, using subject matter knowledge to guide DAG development. This guided statistical modeling for the association between rurality and the risk of suboptimal subspecialty follow-up care among survivors of childhood cancer in Oklahoma. As a secondary outcome and sensitivity analysis, we repeated analyses for the association between rurality and the documentation of a survivorship care plan in Passport for Care for general pediatric oncology survivors (n=369) (Supplemental Figure 2). All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/SE version 17.0 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX), SAS v. 9.4 (Cary, NC), and R (RStudio, 2022.07.1, Build 554).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

RESULTS

The final analytic cohort included 449 childhood cancer survivors (Figure 1), of whom 78.5% (n=358) had a completed clinic visit at the JEC or the SCC between five and seven years after their initial diagnosis (Table 1). Among survivors in Oklahoma (n=440), those from large towns were most likely to receive suboptimal follow-up at 36% (n=28/78) compared to 21% (n=20/95) and 17% (n=46/276) of survivors from small town/isolated rural and urban areas, respectively (p=0.01). The median distance for survivors with suboptimal follow-up was 46.7 miles compared to 24.3 miles for those with optimal follow-up (p<0.01). There was significant heterogeneity in follow-up by primary diagnosis (p<0.01) and survivors at intermediate risk for late effects were more likely to receive suboptimal follow-up at 28% in contrast to 15% of survivors at low and high risk for late effects (p<0.01). Forty-five percent of survivors who were adolescents at the time of diagnosis received suboptimal follow-up compared to 17% of survivors who were younger than thirteen at the time of diagnosis (p<0.01) There were no significant differences in optimal follow-up by sex (p=0.81), race/ethnicity (p=0.28) or ADI (p=0.06).

Figure 1.

Oklahoma Childhood Cancer Survivor Cohort Construction.

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis of Optimal Follow-up 5–7 Years After Initial Diagnosis

| Optimal Follow-up | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=355) | No (n=94) | ||

| Age at Diagnosis, in years (SE; 95%CI) | 6.5 (0.26; 6.0–7.0) | 10.2(0.64; 8.9–11.5) | <0.01 |

| Age at End of Seven-Year Follow-up, in years (SE; 95%CI) | 13.5 (0.26, 13.0–14.0) | 17.2 (0.64, 15.9–18.5) | <0.01 |

| Adolescent at Diagnosis | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 59 (16.6%) | 47 (50.0%) | |

| No | 296 (83.4%) | 47 (50.0%) | |

| Sex | 0.81 | ||

| Male | 199 (56.1%) | 54 (57.4%) | |

| Female | 156 (43.9%) | 40 (42.6%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.26 | ||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 226 (63.7%) | 65 (69.1%) | |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 29 (8.2%) | 12 (12.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 61 (17.2%) | 11 (11.7%) | |

| American Indian | 28 (7.9%) | 5 (5.3%) | |

| Other | 11 (3.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Area Deprivation Index, percentile (SE; 95%CI) | 67.6 (1.3; 65.1–70.2) | 72.9 (2.1; 67.8–78.0) | 0.06 |

| RUCA | 0.01 | ||

| Urban | 230 (64.8%) | 46 (48.9%) | |

| Large Town | 50 (14.1%) | 28 (29.8%) | |

| Small Town/Isolated Rural | 75 (21.1%) | 20 (21.3%) | |

| Distance to Medical Center, Median, in miles (SE) | 24.3 (3.0) | 46.7 (7.1) | <0.01 |

| Travel Time to Medical Center, Median, in minutes (SE) | 26.4 (3.1) | 50.9 (7.7) | <0.01 |

| Primary Diagnosis | <0.01 | ||

| Leukemia | 152 (42.8%) | 22 (23.4%) | |

| Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma | 19 (5.4%) | 9 (9.6%) | |

| Hodgkins Lymphoma | 22 (6.2%) | 19 (20.2%) | |

| CNS | 62 (17.5%) | 15 (16.0%) | |

| Retinoblastoma | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Bone | 14 (3.9%) | 5 (5.3%) | |

| Neuroblastoma | 17 (4.8%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Wilms | 28 (7.9%) | 7 (7.4%) | |

| Sarcoma | 10 (2.8%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Other | 29 (8.2%) | 14 (14.9%) | |

| Late Effects Risk Stratification | <0.01 | ||

| Low | 153 (43.1%) | 28 (29.8%) | |

| Intermediate | 146 (41.1%) | 56 (59.6%) | |

| High | 56 (15.8%) | 10 (10.6%) | |

| Passport for Care * | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 243 (83.5%) | 28 (35.9%) | |

| No | 48 (16.5%) | 50 (64.1%) | |

Excluded pediatric neuro-oncology survivors (n=77), as not routinely entered into PFC

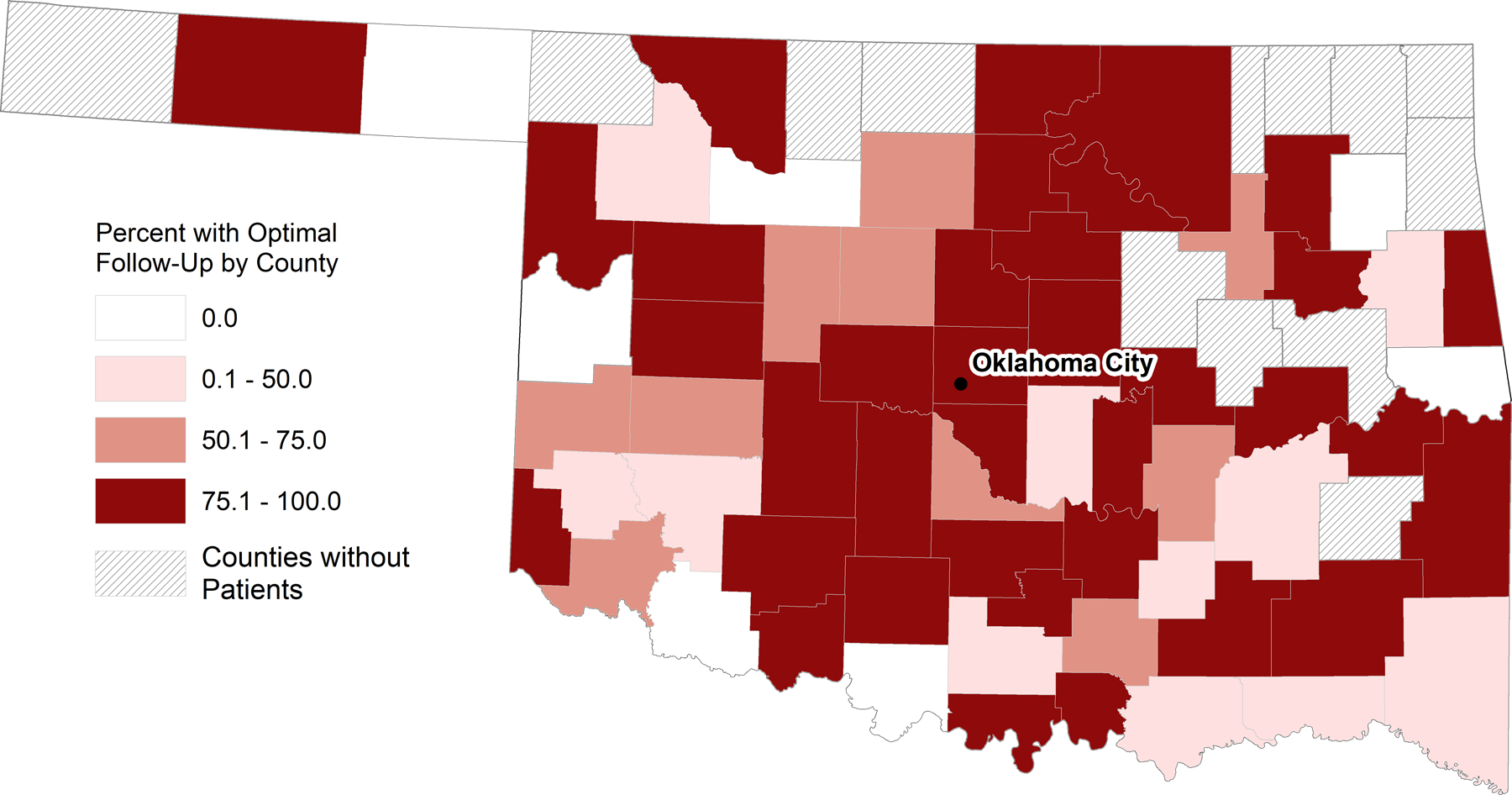

A heat map of Oklahoma provides a visualization of optimal subspecialty follow-up by county (Figure 2). We observed a higher percentage of survivors with optimal follow-up in the central part of the state, including the counties surrounding the medical center in Oklahoma City. The adjusted risk ratio for survivors from large towns was 2.17 (95% CI 1.46, 3.23) compared to survivors from urban areas as the referent population (Table 2). For survivors from small town/isolated rural areas, the risk was increased but the 95% CI encompassed one, with survivors from urban areas as the referent population. When checking the interaction between rurality and the distance from the cancer center in the modified Poisson regression model, the algorithm would not converge and therefore distance was not included in the final model. Consequently, we conducted a subanalysis to separate out non-Oklahoma City urban areas compared with Oklahoma City-urban as the referent population (Supplemental Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of optimal subspecialty follow-up 5–7 years after initial diagnosis

Table 2.

Modeling for the association between rurality and the risk of suboptimal subspecialty follow-up care five to seven years after initial diagnosis using Modified Poisson Regression with robust error variance. (n=449)

| RUCA | Unadjusted Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted1 RR (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Large Town vs. Urban | 2.04 (1.38, 3.01) | 2.17 (1.46, 3.23) |

| Small Town/Isolated Rural vs. Urban | 1.16 (0.72, 1.86) | 1.28 (0.79, 2.09) |

Based on the directed acyclic graph, we adjusted for race/ethnicity

Documentation of a survivorship care plan in PFC was strongly associated with subspecialty follow-up with a risk ratio of 0.20 (95% CI 0.14, 0.28). By rurality, 67% of survivors from large town had a survivorship care plan compared to 79% of survivors from urban areas and 70% of survivors from small town/isolated rural areas (p<0.01). Our secondary analyses yielded similar results to the analysis of rurality and suboptimal subspecialty care follow-up care (Tables 3 and 4, Supplemental Figure 4). The notable exception for this was that late effects risk stratification was not associated with a survivorship care plan (p=0.40).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis for Passport for Care documentation

| Passport for Care | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=271) | No (n=98) | ||

| Age at Diagnosis, in years (SE; 95%CI) | 6.6 (0.31; 6.0–7.2) | 9.1 (0.60; 8.0–10.3) | <0.01 |

| Age at End of Seven-Year Follow-up, in years (SE; 95%CI) | 13.6 (0.31; 13.0–14.2) | 16.1 (0.60; 15.0–17.3) | <0.01 |

| Adolescent at Diagnosis | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 54 (20.0%) | 38 (38.8%) | |

| No | 217 (80.0%) | 60 (61.2%) | |

| Sex | 0.72 | ||

| Male | 152 (56.1%) | 59 (60.2%) | |

| Female | 119 (43.9%) | 39 (39.8%) | |

| Race | 0.76 | ||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 180 (66.4%) | 63 (64.3%) | |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 21 (7.7%) | 10 (10.2%) | |

| Hispanic | 46 (17.0%) | 15 (15.3%) | |

| American Indian | 18 (6.6%) | 9 (9.2%) | |

| Other 1 | 6 (2.2%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Area Deprivation Index, percentile (SE; 95%CI) | 67.4 (1.5; 64.5–70.3) | 73.0 (2.6; 67.9–78.2) | 0.05 |

| RUCA | <0.01 | ||

| Urban | 182 (67.1%) | 47 (48.0%) | |

| Large Town | 36 (13.3%) | 28 (28.6%) | |

| Small Town/Isolated Rural | 53 (19.6%) | 23 (23.5%) | |

| Distance to Medical Center, Median, in miles (SE) | 20.6 (3.4) | 38.9 (7.1) | <0.01 |

| Travel Time to Medical Center, Median, in minutes (SE) | 24.9 (3.5) | 41.3 (7.6) | <0.01 |

| Primary Diagnosis | 0.08 | ||

| Leukemia | 130 (48.0%) | 44 (44.9%) | |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 18 (6.6%) | 10 (10.2%) | |

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 29 (10.7%) | 12 (12.2%) | |

| Bone | 14 (5.2%) | 5 (5.1%) | |

| Neuroblastoma | 14 (5.2%) | 4 (4.1%) | |

| Wilms | 31 (11.4%) | 4 (4.1%) | |

| Sarcoma | 10 (3.7%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Other | 25 (9.2%) | 18 (18.4%) | |

| Late Effects Risk Stratification | 0.43 | ||

| Low | 126 (46.5%) | 53 (54.1%) | |

| Intermediate | 115 (42.4%) | 36 (36.7%) | |

| High | 30 (11.1%) | 9 (9.2%) | |

Excluded pediatric neuro-oncology survivors (n=77), as not routinely entered into PFC

Table 4.

Modeling for the association between rurality and PFC using Modified Poisson Regression with robust error variance. (n=449)

| RUCA | Unadjusted Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Adjusted1 RR (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Large Town vs. Urban | 1.64 (1.23, 2.17) | 1.70 (1.28, 2.27) |

| Small Town/Isolated Rural vs. Urban | 1.41 (1.05, 1.89) | 1.49 (1.10, 2.01) |

Based on the directed acyclic graph, we adjusted for race/ethnicity

DISCUSSION

Survivors of childhood cancer from non-urban areas face complex challenges in optimal oncology-related follow-up care. Those from large towns were least likely to see an oncologist in the early survivorship period. This observed disparity persisted despite adjustment for race/ethnicity as a potential confounder. Furthermore, a strong association between optimal follow-up and a documented survivorship care plan with similar differences by rurality reinforces the importance to integrate late effects education into routine cancer care. The geographic distribution of suboptimal follow-up informs potential strategies to re-engage survivors at greatest risk for late effects, particularly during the transition to adult care when the burden of serious adverse events increases.

Surprisingly, survivors from small town/rural areas had a similar likelihood as those from urban areas of receiving optimal subspecialty follow-up. Among survivors from large towns, no clear pattern emerged in the geographical distribution of survivors with suboptimal care, though the small population size was a challenge and is an area for future work. One limitation of this study was the lack of data on primary care visits in the community and, if care was delivered, whether this constituted survivorship-focused care. The shortage of primary care providers across the United States is well-documented and evidence suggests worsening inequities in the workforce, especially in rural areas.47,48 Survivors from rural areas may have a differential level of access to primary care or prefer to return to their primary oncologist for their survivorship care needs whereas those from large towns may prefer exclusive care from their primary care provider. Nevertheless, a lack of clarity in provider roles portends suboptimal survivorship-focused care as primary care providers often report unmet information needs on the late effects of cancer treatment.49 Indeed, the transition to primary care requires clear, ongoing communication and additional training of community providers concerning specific treatment-related late effects.50

A team-based approach to survivorship-focused care integrates oncology, primary care, subspecialists, patients, and caregivers with the goal to optimize long-term health and outcomes for survivors.51 Shared care with oncology and primary care offers improved follow-up for survivors.52 Survivorship care plans, particularly those available digitally such as PFC, are an initial step to bridge gaps in guideline-adherent care, whether by subspecialists or primary care. Seventy-three percent of pediatric oncology survivors had a survivorship care plan in the Oklahoma Childhood Cancer Survivor Cohort, in contrast to other reports in the literature of only a minority receiving a survivorship care plan, which could facilitate care coordination.53 While an important starting point, optimal care is not guaranteed since primary care providers report additional barriers to the implementation of survivorship care plans.54,55 Therefore, evidence-based interventions to promote team-based care in partnership with primary care as standard practice for survivors are essential to ensure the long-term quality of life for this vulnerable and unique population.

The COVID-19 pandemic spurred the explosion of telehealth applications across the medical field. Within pediatric oncology, the early disruption in long-term follow-up care of survivors and the high acceptability of telehealth during the pandemic illustrate the need for adaptable health systems.56,57 Digital technologies offer innovative, evidence-based strategies to combat cancer care inequities, such as those observed among survivors from large towns in Oklahoma.58 The success of telementoring models, such as Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO), to increase local capacity for subspecialty care in limited resource settings serve as a template for survivorship care delivery among survivors far from tertiary care centers.59 Distance was strongly associated with optimal follow-up care in this study. Consequently, states with a large geographic area and limited subspecialty locations, such as Oklahoma, would benefit from approaches such as ECHO. Other digital interventions, such as mobile health, text messaging, and web-based platforms, challenge traditional models to engage survivors in their care.60

Our study has many strengths, including the availability of an institutional cancer registry at a Commission on Cancer institution. This allowed us to use high-quality cancer data, coupled with EHR data, to evaluate factors related to childhood cancer survivorship. However, limitations include only having a single address at cancer diagnosis, which may not reflect residence during survivorship care, resulting in potential misclassification of rurality status. The use of the five to seven-year window after initial diagnosis as the early survivorship period may overlap with ongoing surveillance for disease recurrence by the primary oncologist and not represent survivorship-focused care. While 73% of general pediatric oncology survivors had a documented survivorship plan (n=271/369), survivors from CNS tumors may have different recommendations for follow-up care and this merits further investigation. Moreover, because there are two children’s hospitals providing treatment and survivorship care in the state, those residing in the northeastern part of the state may seek survivorship care at another institution. A manual chart review of all survivors without a completed clinic visit within the follow-up window excluded survivors with a documented transfer of care, including survivorship care, which helps ameliorate this bias. Additionally, these observations in follow-up care may not be generalizable to rural states with earlier Medicaid expansion, particularly for the identified disparities among adolescents at diagnosis who transitioned to young adulthood during the follow-up window, as insurance status is critical and has been shown to improve access to care for young adults.61 Oklahoma was a late adopter of Medicaid expansion with implementation in July 2021, which may have exacerbated these observed disparities.62 Fragmented healthcare systems across the United States highlight the need for access to services, data interoperability, and health information exchange to improve care, particularly for survivors from non-urban areas.63

Approximately one-fifth of survivors were not seen in an oncology-related subspecialty clinic during the early survivorship period five to seven years after their initial diagnosis. Survivors from large towns, adolescents at diagnosis, and those further from the cancer center were significantly less likely to receive optimal follow-up. Primary diagnosis and late effects risk strata were also associated with optimal follow-up, which raises questions for further research to target at-risk groups. This analysis focused primarily on rurality. There is a clear need for continued, longitudinal surveillance of survivor cohorts from non-urban communities to assess inequities and develop health systems-based interventions tailored to the unique needs of this at-risk community. Clinical research informatics methods, such as those presented here, to integrate cancer registry, EHR, geospatial, and other data sources provide a framework for population health management of survivors at high risk for late effects.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Each person listed as an author is aware of the content of the manuscript and has participated in the study to a significant extent. DHN, AJ, WB and KCO, developed the concept and drafted the manuscript. DN, AJ, WB, NE contributed to the data preparation, modeling, and prepared tables and figures. All other authors provided guidance on the methodology, reviewed the manuscript, and provided critical revisions.

Funding/Support:

D. H. Noyd was supported by the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology Conquer Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. Jan 2014;14(1):61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong GT, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Reduction in Late Mortality among 5-Year Survivors of Childhood Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(9):833–842. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon SB. A decreasing cost of cure in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Jan 2022;69(1):e29429. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gibson TM, Mostoufi-Moab S, Stratton KL, et al. Temporal patterns in the risk of chronic health conditions in survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed 1970–99: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncol. Dec 2018;19(12):1590–1601. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30537-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AM, Liu Q, Bhakta N, et al. Rethinking Success in Pediatric Oncology: Beyond 5-Year Survival. J Clin Oncol. Jul 10 2021;39(20):2227–2231. doi: 10.1200/jco.20.03681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates JE, Howell RM, Liu Q, et al. Therapy-Related Cardiac Risk in Childhood Cancer Survivors: An Analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(13):1090–1101. doi: 10.1200/jco.18.01764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, et al. Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. Oct 1 2008;100(19):1368–79. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulrooney DA, Hyun G, Ness KK, et al. Major cardiac events for adult survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed between 1970 and 1999: report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Bmj. Jan 15 2020;368:l6794. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suh E, Stratton KL, Leisenring WM, et al. Late mortality and chronic health conditions in long-term survivors of early-adolescent and young adult cancers: a retrospective cohort analysis from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Lancet Oncol. Mar 2020;21(3):421–435. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(19)30800-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonorezos ES, Cohn RJ, Glaser AW, et al. Long-term care for people treated for cancer during childhood and adolescence. The Lancet. 2022/04/16/ 2022;399(10334):1561–1572. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00460-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landier W, Skinner R, Wallace WH, et al. Surveillance for Late Effects in Childhood Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol. Jul 20 2018;36(21):2216–2222. doi: 10.1200/jco.2017.77.0180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson MM, Bhatia S, Casillas J, Landier W. Long-term Follow-up Care for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3):e2021053127. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-053127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kremer LCM, Mulder RL, Oeffinger KC, et al. A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2013;60(4):543–549. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poplack DG, Fordis M, Landier W, Bhatia S, Hudson MM, Horowitz ME. Childhood cancer survivor care: development of the Passport for Care. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2014/12/01 2014;11(12):740–750. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noyd DH, Neely NB, Schroeder KM, et al. Integration of cancer registry and electronic health record data to construct a childhood cancer survivorship cohort, facilitate risk stratification for late effects, and assess appropriate follow-up care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Mar 19 2021:e29014. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casillas J, Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, et al. Identifying Predictors of Longitudinal Decline in the Level of Medical Care Received by Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Health Services Research. 2015;50(4):1021–1042. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan AA, Ashraf A, Singh R, et al. Incidence, time of occurrence and response to heart failure therapy in patients with anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Intern Med J. Jan 2017;47(1):104–109. doi: 10.1111/imj.13305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veiga LH, Curtis RE, Morton LM, et al. Association of Breast Cancer Risk After Childhood Cancer With Radiation Dose to the Breast and Anthracycline Use: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA Pediatr. Dec 1 2019;173(12):1171–1179. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Department of Agriculture ERS. State Fact Sheet: United States. https://data.ers.usda.gov/reports.aspx?ID=17854

- 20.Ziller E, Milkowski C. A Century Later: Rural Public Health’s Enduring Challenges and Opportunities. Am J Public Health. Nov 2020;110(11):1678–1686. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2020.305868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Chen Y, et al. Modifiable risk factors and major cardiac events among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. Oct 10 2013;31(29):3673–80. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.49.3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aggarwal R, Chiu N, Loccoh EC, Kazi DS, Yeh RW, Wadhera RK. Rural-Urban Disparities: Diabetes, Hypertension, Heart Disease, and Stroke Mortality Among Black and White Adults, 1999–2018. J Am Coll Cardiol. Mar 23 2021;77(11):1480–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah NS, Carnethon M, Lloyd-Jones DM, Khan SS. Widening Rural-Urban Cardiometabolic Mortality Gap in the United States, 1999 to 2017. J Am Coll Cardiol. Jun 30 2020;75(25):3187–3188. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierce JB, Shah NS, Petito LC, et al. Trends in heart failure-related cardiovascular mortality in rural versus urban United States counties, 2011–2018: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural-urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1050–1057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer NR, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD, Weaver KE. Impact of rural residence on forgoing healthcare after cancer because of cost. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. Oct 2013;22(10):1668–76. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-13-0421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedro LW, Schmiege SJ. Rural living as context: a study of disparities in long-term cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. May 2014;41(3):E211–9. doi: 10.1188/14.Onf.E211-e219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walling EB, Fiala M, Connolly A, Drevenak A, Gehlert S. Challenges Associated With Living Remotely From a Pediatric Cancer Center: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2019;15(3):e219–e229. doi: 10.1200/jop.18.00115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wercholuk AN, Parikh AA, Snyder RA. The Road Less Traveled: Transportation Barriers to Cancer Care Delivery in the Rural Patient Population. JCO Oncol Pract. Sep 2022;18(9):652–662. doi: 10.1200/op.22.00122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.State cancer registries: status of authorizing legislation and enabling regulations--United States, October 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Feb 4 1994;43(4):71, 74–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boffa DJ, Rosen JE, Mallin K, et al. Using the National Cancer Database for Outcomes Research: A Review. JAMA Oncol. Dec 1 2017;3(12):1722–1728. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Lacour B, Kaatsch P. International Classification of Childhood Cancer, third edition. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1457–1467. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frobisher C, Glaser A, Levitt GA, et al. Risk stratification of childhood cancer survivors necessary for evidence-based clinical long-term follow-up. British journal of cancer. 2017;117(11):1723–1731. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. Jul 2005;95(7):1149–55. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2004.042432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Service USDoAER. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx

- 36.University TAM. Texas A&M GeoServices. Accessed February 18, 2022. http://geoservices.tamu.edu/About/.

- 37.Bureau USC. Tiger/Line Shape Files. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.census.gov/geographies/mapping-files/time-series/geo/tiger-line-file.2019.html

- 38.Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making Neighborhood-Disadvantage Metrics Accessible — The Neighborhood Atlas. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(26):2456–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1802313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Health UoWSoP. 2015. Area Deprivation Index v2.0. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/

- 40.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Wiley series in probability and statistics. Wiley-Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. May 15 2003;157(10):940–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. Apr 1 2004;159(7):702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tennant PWG, Murray EJ, Arnold KF, et al. Use of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to identify confounders in applied health research: review and recommendations. Int J Epidemiol. May 17 2021;50(2):620–632. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal Diagrams for Epidemiologic Research. Epidemiology. 1999;10(1):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. Jul 2009;20(4):488–95. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. Sep 2004;15(5):615–25. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000135174.63482.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang D, Son H, Shen Y, et al. Assessment of Changes in Rural and Urban Primary Care Workforce in the United States From 2009 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. Oct 1 2020;3(10):e2022914. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gemelas JC. Post-ACA Trends in the US Primary Care Physician Shortage with Index of Relative Rurality. J Rural Health. Sep 2021;37(4):700–704. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Howard J, et al. Cancer Survivorship Care Roles for Primary Care Physicians. Ann Fam Med. May 2020;18(3):202–209. doi: 10.1370/afm.2498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Fardell JE, et al. The Role of Primary Care Physicians in Childhood Cancer Survivorship Care: Multiperspective Interviews. Oncologist. May 2019;24(5):710–719. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alfano CM, Oeffinger K, Sanft T, Tortorella B. Engaging TEAM Medicine in Patient Care: Redefining Cancer Survivorship From Diagnosis. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. Apr 2022;42:1–11. doi: 10.1200/edbk_349391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ducassou S, Chipi M, Pouyade A, et al. Impact of shared care program in follow-up of childhood cancer survivors: An intervention study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Nov 2017;64(11)doi: 10.1002/pbc.26541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirchhoff AC, Montenegro RE, Warner EL, et al. Childhood cancer survivors’ primary care and follow-up experiences. Support Care Cancer. Jun 2014;22(6):1629–35. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2130-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iyer NS, Mitchell HR, Zheng DJ, Ross WL, Kadan-Lottick NS. Experiences with the survivorship care plan in primary care providers of childhood cancer survivors: a mixed methods approach. Support Care Cancer. May 2017;25(5):1547–1555. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3544-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.LaGrandeur W, Armin J, Howe CL, Ali-Akbarian L. Survivorship care plan outcomes for primary care physicians, cancer survivors, and systems: a scoping review. J Cancer Surviv. Jun 2018;12(3):334–347. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0673-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kenney LB, Vrooman LM, Lind ED, et al. Virtual visits as long-term follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors: Patient and provider satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Jun 2021;68(6):e28927. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wimberly CE, Towry L, Caudill C, Johnston EE, Walsh KM. Impacts of COVID-19 on caregivers of childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Apr 2021;68(4):e28943. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arora S, Ryals C, Rodriguez JA, Byers E, Clewett E. Leveraging Digital Technology to Reduce Cancer Care Inequities. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. Apr 2022;42:1–8. doi: 10.1200/edbk_350151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McBain RK, Sousa JL, Rose AJ, et al. Impact of Project ECHO Models of Medical Tele-Education: a Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. Dec 2019;34(12):2842–2857. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05291-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mobley EM, Moke DJ, Milam J, et al. Interventions to address disparities and barriers to pediatric cancer survivorship care: a scoping review. J Cancer Surviv. Jun 2022;16(3):667–676. doi: 10.1007/s11764-021-01060-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cha P, Brindis CD. Early Affordable Care Act Medicaid: Coverage Effects for Low- and Moderate-Income Young Adults. J Adolesc Health. Sep 2020;67(3):425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Authority OHC. Medicaid Expansion. Accessed October 21, 2022, https://oklahoma.gov/ohca/about/medicaid-expansion/expansion.html

- 63.Nakayama M, Inoue R, Miyata S, Shimizu H. Health Information Exchange between Specialists and General Practitioners Benefits Rural Patients. Appl Clin Inform. May 2021;12(3):564–572. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.