Abstract

The 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of many eukaryotic mRNAs is essential for their control during early development. Negative translational control elements in 3′UTRs regulate pattern formation, cell fate, and sex determination in a variety of organisms. tra-2 mRNA in Caenorhabditis elegans is required for female development but must be repressed to permit spermatogenesis in hermaphrodites. Translational repression of tra-2 mRNA in C. elegans is mediated by tandemly repeated elements in its 3′UTR; these elements are called TGEs (for tra-2 and GLI element). To examine the mechanism of TGE-mediated repression, we first demonstrate that TGE-mediated translational repression occurs in Xenopus embryos and that Xenopus egg extracts contain a TGE-specific binding factor. Translational repression by the TGEs requires that the mRNA possess a poly(A) tail. We show that in C. elegans, the poly(A) tail of wild-type tra-2 mRNA is shorter than that of a mutant mRNA lacking the TGEs. To determine whether TGEs regulate poly(A) length directly, synthetic tra-2 3′UTRs with and without the TGEs were injected into Xenopus embryos. We find that TGEs accelerate the rate of deadenylation and permit the last 15 adenosines to be removed from the RNA, resulting in the accumulation of fully deadenylated molecules. We conclude that TGE-mediated translational repression involves either interference with poly(A)'s function in translation and/or regulated deadenylation.

Regulatory elements in the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) can dramatically influence cell fate and early development by controlling mRNA stability, location, and translational activity (3, 4, 8, 18, 31, 35, 43, 51, 61). Negative translational control elements in 3′UTRs have been identified genetically that disrupt pattern formation, cell-cell interactions, and cell fate determination in the early embryo (reviewed in references 8 and 61). In many cases, repression by such negative control elements is correlated with the presence of shorter poly(A) tails. Although the activity of 3′UTR control elements commonly requires binding to regulatory proteins, the mode of action of these RNA-protein complexes has not been elucidated in detail.

Caenorhabditis elegans is a self-fertilizing hermaphrodite worm, in which a single individual produces both oocytes and sperm. Hermaphrodites are somatic females that first produce sperm and then switch and make oocytes. The tra-2 gene normally directs female development (19), and its repression is required for the onset of hermaphrodite spermatogenesis. The tra-2 gene product, presumed to be a transmembrane protein, inhibits male determinants and coordinates neighboring cells to adopt the same fate (29, 37). tra-2 gain-of-function (gf) mutants are defective in a cis-acting translational control element located in the tra-2 3′UTR (see Fig. 5A) (17). This element mediates translational repression of tra-2 RNA, as judged by polysome analysis and reporter experiments in C. elegans (17). In tra-2 mRNA, the element is tandemly repeated. Each individual element is called a TGE (for tra-2 and GLI elements). TGEs are not limited to the C. elegans tra-2 mRNA but have been identified in tra-2 from Caenorhabditis briggsae, C. elegans tra-1, and the human oncogene GLI (23).

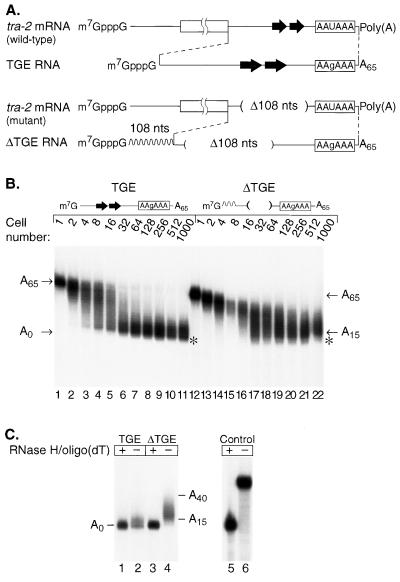

FIG. 5.

tra-2 TGEs promote rapid deadenylation in Xenopus embryos. (A) Diagram of the 3′UTR RNAs used in this experiment for injections into Xenopus embryos. A box represents the coding region, and lines represent the 5′UTR and 3′UTR. The TGEs are represented by large arrows. The TGE RNA substrate consists of the entire 3′UTR of tra-2. The ΔTGE RNA contains a 108-nucleotide deletion (Δ108 nts) and lacks the TGEs and flanking sequences. To compensate for size differences, it has an insert of 108 nucleotides of vector sequences 5′ to the tra-2 sequences (represented by a wavy line). Both RNAs contain a point mutation in AAUAAA (AAgAAA) and a 65-nucleotide poly(A) tail. (B) TGE RNA (lanes 1 through 11) or ΔTGE RNA (lanes 12 through 22) containing AAgAAA and a A65 poly(A) tail were injected into one-cell Xenopus embryos. Embryos were collected at various stages of development ranging from 1-cell to 1,000-cell stage. The position of a fully deadenylated RNA is indicated by an asterisk. (C) RNase H-oligo(dT) treatment of injected RNAs. RNA was extracted from 1,000-cell embryos injected with TGE RNA (lanes 1 and 2) or ΔTGE RNA (lanes 3 and 4). Extracted RNAs were treated with RNase H-oligo(dT) (odd-number lanes) or not (even-number lanes) and then analyzed by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. As a control for the effectiveness of the RNase H-oligo(dT) digestion, an uninjected RNA containing a poly(A) tail of A65 was treated (lane 5) with RNase H-oligo(dT) or untreated (lane 6). The migration position relative to those of molecular weight standards is consistent with complete removal of the poly(A) tail.

GLD-1 was identified using the Saccharomyces cerevisiae three-hybrid system as a protein that specifically binds to TGEs and represses translation of TGE-containing reporter RNAs in vivo and in vitro (22). GLD-1 is germ line specific and is required for oogenesis as well as spermatogenesis (16, 24). GLD-1 is a member of the STAR protein family, consisting of a single KH RNA-binding domain with conserved QUA1 and QUA2 motifs (for a review, see reference 55). STAR proteins are found in a wide range of species, from invertebrates to mammals.

In several systems, regulated changes in poly(A) length are correlated with changes in translational activity. Increases in length are correlated with increases in translation, and decreases with repression (reviewed in references 18 and 41). Changes in poly(A) length may be required for translational regulation. For example, in the Drosophila embryo, translation of bicoid mRNA requires a distinct length of poly(A) such that the mRNA must undergo polyadenylation to become translationally active (44), while repression of hunchback mRNA apparently requires deadenylation (62). However, translational repression can also cause deadenylation (34), indicating that changes in poly(A) length can also be the result, rather than the cause, of altered translational activity. In yeast and in somatic cells, poly(A) may facilitate translation by binding to poly(A) binding protein (PAB). The poly(A)-PAB complex interacts with eIF-4G, a translation initiation factor, which in turn binds to eIF-4E, the cytoplasmic cap binding protein (52, 53, 59). This end-to-end linkage could play a role in the effects of regulated changes in poly(A) length on translational activity in embryos and in the function of 3′UTR regulatory elements (reviewed in references 18 and 43).

Sequences that control poly(A) tail lengths commonly are located within the 3′UTR (reviewed in reference 41) and can function across species (56). In Xenopus embryos, the length of poly(A) present on an mRNA at any given time is determined by competing reactions that add and remove adenosines. Poly(A) tail lengthening requires a cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE) and the nuclear polyadenylation signal, AAUAAA. Poly(A) shortening occurs by two mechanisms: a rapid deadenylation caused by specific sequences in the 3′UTR (e.g., references 1, 39, and 58) and a slow deadenylation that acts on RNAs without either a CPE or AAUAAA, termed default deadenylation (15 54).

In this report we investigate the molecular mechanism by which TGEs regulate translation. In the Xenopus embryo, TGEs repress translation and do so through a mechanism that requires a poly(A) tail. TGEs promote rapid, regulated deadenylation in the Xenopus embryo and cause shorter poly(A) tails in C. elegans. Since TGEs function across species and in multiple developmental stages, their poly(A)-dependent mechanism of repression may be widespread.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides.

The sequences and nomenclature of oligonucleotides are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| RACE-1 | GCGAGCTCCGCGGCCGCGT12 |

| CAH-1 | CACTTCCACCAGTTGGTCGATT |

| RACE-2 | GCGAGCTCCGCGGCCGCG |

| CAH-3 | ACCGAACTGGACAGCTACCTCCAG |

| CAH-4 | ATTCGAGCTCACTCTGACCCCA |

| EBG-20 | ATTTTTATTGTCGACAATGTCTGTTTCCTTTTCAG |

| EBG-21b | AAATTTTATAGATCTTTTCTTAACAAGAAAACAAAA |

| 5′ insert | GACTGAAGCATTTATCAGGG |

| 3′ insert | GACCACTTTCGGGGAAATG |

| EBG-21a | AAATTTTATAGATCTTTTATTAACAAGAAAACAAAA |

| 9408.01 | GATCCTCGAGCCCGGGACTAGTA |

| 9408.02 | GATCTACTAGTCCCGGGCTCGAG |

| SpeI L1 | CTAAGGCAGCGGAAAACTAGTAATCCCAGAGCG |

| TGE1 | CTAGTTATTTAATTTCTTATCTACTCATATCTACTCATATTTAATTTCTTATCTACTCATATCTAG |

| TGE2 | CTAGCTAGATATGAGTACATAAGAAATTAAATATGAGTGAGTAGATAAGAAATTAAATAA |

RNA sequences and transcription templates. (i) mRNAs containing HA-tagged luciferase followed by TGE or ΔTGE tra-2 3′UTRs.

The SalI/BglII fragments containing the tra-2 3′UTR sequences (see pBtra-2 [wild type] and pBtra-2 [ΔTGE]) were subcloned into pLuc/polylinker. pLuc/polylinker was constructed by inserting annealed oligonucleotides 9408.01 and 9408.02 into the BglII site of pLuc/cyclin B1 (49); J. Collar and M. Wickens, unpublished data). A StyI fragment from pXlpap-HA containing a hemagglutinin (HA) tag (2) was placed in frame upstream of the luciferase coding region by insertion at the StyI site in the pLuc/wild-type and pLuc/ΔTGE plasmids. An A65 sequence was introduced by inserting the XbaI/ScaI fragment from pAFB102 (A. Barkoff and M. Wickens, unpublished data) into the SpeI/ScaI site of the pHA-Luc/wild-type and pHA-Luc/ΔTGE plasmids to generate pHA-Luc/wild-type-pA and pHA-Luc/ΔTGE-pA, respectively. To prepare HA-Luc/TGE tra-2 and HA-Luc/ΔTGE tra-2 RNAs, pHA-Luc/wild-type and pHA-Luc/ΔTGE plasmids were linearized with SpeI and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (Stratagene). To prepare HA-Luc/TGE-pA tra-2 and HA-Luc/ΔTGE-pA tra-2 RNAs, pHA-Luc/wild-type-pA and pLuc/ΔTGE-pA plasmids were linearized with BglII and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (Stratagene).

(ii) 3′UTR RNAs with or without TGE that lack AAUAAA.

To construct pBtra-2pA (wild type) and pBtra-2pA (ΔTGE plus insert), a PCR product was generated using primers EBG-20 and EBG-21b to amplify the tra-2 3′UTRs from genomic DNA isolated from either tra-2 (wild-type) or tra-2(gf) animals. The 3′ primer contains a U-to-G mismatch to generate the AAgAAA mutant polyadenylation signal. The PCR products were digested with SalI and BglII and cloned into the SalI and BamHI sites of pBluescript II KS(+), creating pBtra-2 (wild type) and pBtra-2 (ΔTGE). The A65 poly(A) tail was added by digesting these constructs with XbaI and ScaI, replacing this fragment with the XbaI/ScaI fragment containing a A65 poly(A) tract from pABF102 (Barkoff and Wickens, unpublished). To generate a ΔTGE tra-2 transcript with a length equivalent to that of the TGE tra-2 RNA, a 108-nucleotide insert was generated by amplifying pBluescript II KS (+) with a 5′ insert primer and 3′ insert primer using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). This product was ligated into the HincII (Promega) site of pBtra-2pA (ΔTGE) to generate pBtra-2pA (ΔTGE plus insert). The resulting insert did not create an open reading frame or an AUG in a favorable context for use as a start codon based on Kozak consensus sequences (25, 26). Identical results were obtained with a ΔTGE tra-2 RNA lacking the 108-nucleotide insert at the 5′ end of the RNA (data not shown). TGE and ΔTGE tra-2 RNAs were transcribed with T3 RNA from BglII-digested pBtra-2pA (wild type) and pBtra-2pA (ΔTGE plus insert). To prepare RNAs without the A65 poly(A) tail, the DNA was linearized before the poly(A) tract with SpeI and transcribed with T3 RNA polymerase.

(iii) 3′UTR RNAs with or without TGE that contain AAUAAA.

The templates for these RNAs were constructed as above except that the EBG-21b primer was replaced with the EBG-21a primer that encodes a wild-type nuclear polyadenylation signal, AAUAAA. The pBtra-2pA (wild-type) and pBtra-2pA (ΔTGE plus insert) with AAUAAA constructs were further manipulated to reduce the distance between AAUAAA and the beginning of the poly(A) tail by digesting with XbaI and SpeI (Promega) followed by mung bean nuclease treatment as described by the manufacturer (Promega). These ends were religated, resulting in an 11-nucleotide deletion and generating pBtra-2pA (wild-type) XS and pBtra-2pA (ΔTGE plus insert) XS. To prepare TGE and ΔTGE tra-2 RNAs with AAUAAA, BglII-digested DNA was transcribed with T3 RNA polymerase.

(iv) RNAs containing zero or four TGEs (see Fig. 3).

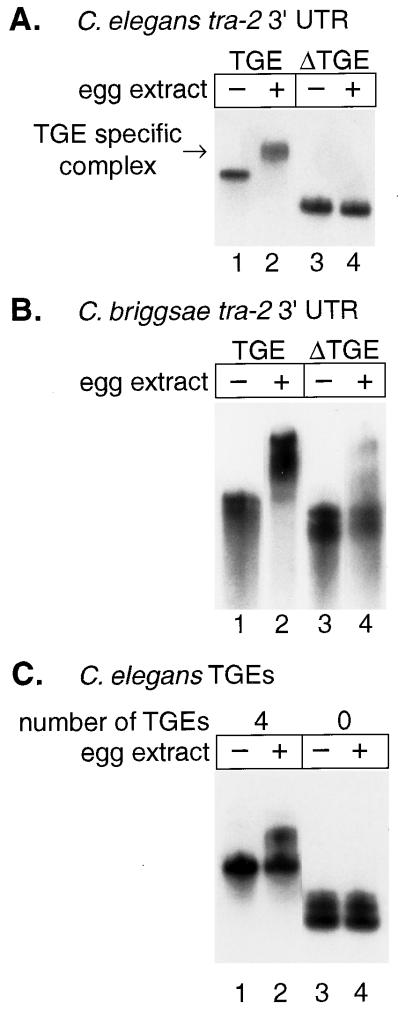

FIG. 3.

A TGE-specific binding factor in Xenopus egg extract. (A) Labeled RNAs carrying the C. elegans tra-2 3′UTR either with the TGEs (lanes 1 and 2) or lacking the TGEs (ΔTGE) (lanes 3 and 4) were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of Xenopus egg extract. (B) Labeled RNAs carrying the C. briggsae tra-2 3′UTR either with the TGE (lanes 1 and 2) or lacking the TGE (ΔTGE) (lanes 3 and 4) were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of Xenopus egg extract. (C) RNAs containing four C. elegans TGEs alone (in the absence of the rest of the tra-2 3′UTR) (lanes 1 and 2) or no TGEs (lanes 3 and 4) were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of Xenopus egg extract. RNA complexes were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

A SpeI site was introduced into pL1+ CPE/3Zf+ (56) by site-directed mutagenesis (28) using the SpeI L1 oligonucleotide. The resulting plasmid, pSpeI L1+CPE/3Zf+, was linearized with SpeI (Promega), and the annealed oligonucleotides, TGE1 and TGE2 (consisting of two TGEs), were inserted. A clone containing two inserts was isolated (4TGE/3Zf+). To prepare RNAs containing zero or four TGEs, pL1 + CPE/3Zf+ and 4TGE/3Zf+, respectively, were linearized with Hsp92I, upstream of the CPE and AAUAAA sequences.

(v) RNAs that contain the 3′UTR of C. briggsae tra-2.

RNAs were prepared from Cb-tra-2(+) 3′UTR and Cb-tra-2 (−38) 3′UTR as described in reference 23.

(vi) HA-C100 RNA.

Transcripts were produced by linearizing pHA-C100 (9) with HpaI and transcribing with SP6 polymerase (Promega).

PAT assay.

tra-2 mRNA was isolated from wild-type and gain-of-function (e2020) worms using the method of Chomczynski and Sacchi (7). Endogenous mRNA poly(A) tail lengths were measured by the poly(A) test (PAT) analysis (45) essentially as previously described (23). RACE-1 oligonucleotide was used for the reverse transcription reactions. A PCR was performed as previously described (23), using primers CAH-1 (which hybridizes to the coding region of tra-2) and RACE-1 [which anneals to the poly(A) tail]. Then a nested PCR was performed using the RACE-2 oligonucleotide and specific oligonucleotides for the wild-type tra-2, for CAH-3, or for the gain-of-function, CAH-4. The products of this PCR were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide (Sigma).

In vitro transcription.

Capped RNAs of specific radioactivity of 1 × 103 to 20 × 103 cpm/fmol (injection of 3′UTRs), 2 × 102 cpm/fmol (injected translational reporter mRNAs), or unlabeled (HA-C100 RNA) were prepared by in vitro transcription of linearized plasmid templates using either bacteriophage T3 (Gibco BRL), T7 (Promega or Stratagene), or SP6 (Promega) RNA polymerase. Transcription reactions were carried out essentially as described by the manufacturers, using m7GpppG (cap analog) (New England Biolabs) and, if radiolabeled, 40 to 100 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (DuPont). RNAs consisting of 3′UTR sequences were gel isolated from a denaturing gel containing 6% polyacrylamide. RNAs were eluted from a gel slice by incubating overnight at 25°C in a solution of 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5 M ammonium acetate. Reporter mRNAs were treated with DNase I, and free nucleotides were removed with a G-50 Sephadex column (Boehringer Mannheim). All RNAs were extracted three times with a 5:1 mixture of phenol-chloroform (pH 4.7) (Amresco). Transcripts were precipitated three times with ethanol. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol after each precipitation. RNA was resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water.

Embryo injections. (i) RNA injections.

Eggs were obtained, fertilized, and dejellied essentially as described previously (36). To obtain eggs for fertilization, adult females were injected with 50 U of pregnant mare serum (Calbiochem) 2 to 5 days prior to oviposition. Females were induced to lay eggs by injection with 500 U of human chorionic gonadotropin hormone (Sigma). Eggs were collected in 1× MMR (1× MMR is 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.4]) at 18°C. The eggs were drained of any buffer and smeared with macerated testes. Water was added to activate the sperm. Fertilized eggs were identified by contraction of the animal hemisphere and cortical rotation. Approximately 30 min after fertilization, the eggs were treated with 2% cysteine (Sigma) in 1× MMR, neutralized to pH 7.8. The dejellied eggs were rinsed several times with 1× MMR and placed in 5% Ficoll400 (Sigma) in 1× MMR. Injection of the embryo was performed essentially as previously described (57). RNA (2 fmol) (10 nl) was injected into the embryo before the first cleavage. Single embryos were collected by freezing on dry ice. The embryos were moved to 0.1× MMR between the 8-cell and 16-cell stage.

(ii) [35S]methionine-cysteine injections.

Embryos which previously had been injected with reporter RNAs were subsequently injected with 0.1 μCi (10 nl) of Tran35S-label (ICN) or [35S]methionine (Amersham) at the 64-cell stage. Incubation of the embryos was continued for 60 min (approximately two cleavage events) following injection with label. Embryos were collected in sets of 10 and frozen on dry ice.

Extraction and analysis of RNA.

Each individual embryo was analyzed separately. RNAs were isolated from single embryos by homogenization in 400 μl of a solution containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.9), 5 mM EDTA, 2% SDS, and 300 mM NaCl, followed by extraction with phenol-chloroform (5:1) (pH 4.7) (Amresco) and ethanol precipitation of the aqueous phase. The RNA was resuspended in 8 μl of DEPC-treated water and 4 μl of loading buffer (46). The equivalent of 0.5 to 1 embryo was analyzed on a single lane of a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea (47). Electrophoresis was performed for 2.5 h at 1,200 V. Autoradiographic exposures of dried gels were generally for 12 to 36 h with an intensifying screen at −70°C.

Molecular size standards.

MspI fragments of pBR322 were labeled using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (Promega) and [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham). Protein molecular size standards were SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) low range standards (Bio-Rad) or BenchMark prestained protein standards (Gibco BRL). DNA standards were a 100-bp ladder (Gibco BRL).

RNase H-oligo(dT) digestion.

RNA was extracted from a single embryo as described previously (see above) except the RNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol. Half of the RNA isolated from a single embryo was incubated in 1× RNase H buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, and 1 mM dithiothreitol) with 5 μg of oligo(dT)12–18 (Pharmacia) at 65°C for 5 min and slowly cooled to 37°C, at which point 0.5 to 2 U of RNase H (Promega) was added to the reaction mixture. The RNase H reaction mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The other half of the RNA sample from the embryo was treated identically except that no oligo(dT) or RNase H enzyme was added. Then the reaction mixture was diluted to 200 μl with DEPC-treated water containing 100 mM NaCl, and proteins were extracted with phenol-chloroform 5:1 (pH 4.7) (Amresco); the aqueous phase was then mixed with ethanol. The precipitated RNA was resuspended in DEPC-treated water and loading buffer and analyzed on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel as described previously.

Analysis of formation of complexes.

Capped, labeled RNA (2 fmol) and Xenopus egg extract (5 μg) (prepared as described previously [13]) were incubated as previously described (17). Loading buffer III (46) was added to the RNA and egg extract, and the mixture was loaded on a 2× TBE (46) 7% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel (ratio of acrylamide to bisacrylamide was 19:1) (gel dimensions were 25 cm long and 1.5 mm thick), which had been preequilibrated to 4°C. The gel was run in 2× TBE running buffer at 4°C for 1.5 to 3 h at 10 W.

Immunoprecipitation.

Ten embryos were homogenized in 1 ml of radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) plus protease inhibitors (150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8], 10 μg of leupeptin per ml, 1 μg of pepstatin per ml, 1 μg of chymostatin per ml, 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, and 17.4 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride per ml). Homogenates were centrifuged for 2 min at 16,000 × g at 4°C. The cleared lysate was collected and incubated with 30 μg of anti-HA mouse monoclonal antibody clone 12CA5 (Berkeley Antibody Company), rocking gently for 1 h at 4°C. Protein A-Sepharose beads CL4B (Sigma) (5 μg) were added, and the incubation was continued for 1 h at 4°C with gentle rocking. Beads were collected by centrifuging for 5 min at 2,000 × g and washed three times with RIPA plus protease inhibitors. Beads were resuspended in protein loading buffer and boiled for 3 min. Proteins were analyzed on an SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gel. The protein gel was stained (0.25% Coomassie blue, 50% methanol, 10% acetic acid) and destained (40% methanol and 10% acetic acid) followed by a 30-min incubation in Amplify (Amersham). The protein gel was dried and exposed to a preflashed film using a Sensitize preflash unit RPN 2051 (Amersham) for quantitative analysis. Quantitations were performed using NIH image 1.60.

RESULTS

TGEs repress translation in Xenopus embryos.

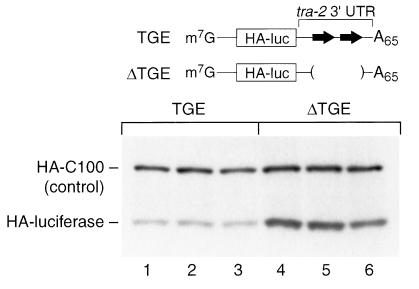

To determine whether TGE-dependent translational repression occurs in Xenopus embryos, we injected reporter mRNAs with or without TGEs into fertilized Xenopus eggs. These reporter RNAs contained an N-terminal HA tag linked to a luciferase coding region followed by either the wild-type C. elegans tra-2 3′UTR or a tra-2 3′UTR without TGEs. These mRNAs both contain a wild-type nuclear polyadenylation signal (AAUAAA) and a 65-nucleotide poly(A) tail. The in vitro-transcribed RNAs were coinjected into 1-cell embryos, together with a control RNA (HA-C100) whose expression is constant throughout early development (9). To measure translation of the injected mRNAs, we injected [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine at the 64-cell stage, continued the incubation for 1 h, and then immunoprecipitated the proteins using an anti-HA antibody. Newly synthesized proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. For each mRNA, three separate groups of embryos are shown in Fig. 1. The injected RNAs were equally stable, as judged by electrophoresis and autoradiography (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

TGE-regulated translational repression is conserved in Xenopus embryos. HA-tagged luciferase reporter mRNAs carrying the tra-2 3′UTR were prepared and injected into embryos. The 3′UTRs either contained the TGEs (lanes 1 to 3) or lacked the TGEs (ΔTGE) (lanes 4 to 6); both mRNAs contained a wild-type (AAUAAA) polyadenylation signal and an A65 poly(A) tail. mRNAs were coinjected with HA-C100 mRNA (a control) into 1-cell embryos. The embryos were reinjected at the 64-cell stage with [35S]methionine-cysteine, and incubated for 1 h before collecting embryos and immunoprecipitating HA-tagged proteins. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Translation of the mRNA carrying the wild-type 3′UTR (TGE) was repressed compared to that of an mRNA from which the TGEs had been deleted (ΔTGE) (Figure 1, compare lanes 1 to 3 to lanes 4 to 6). The magnitude of repression was comparable to that observed in C. elegans (two- to threefold; E. Jan and B. Goodwin, personal communication). We conclude that TGEs cause translational repression in Xenopus embryos.

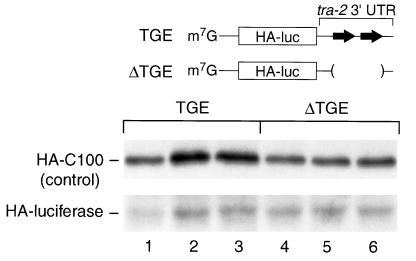

Repression requires a poly(A) tail.

To elucidate whether TGE-mediated repression required a poly(A) tail, we prepared reporter mRNAs identical to those in Fig. 1, except that they lacked a poly(A) tail and carried a point mutation in AAUAAA, converting it to AAgAAA (point mutation shown in lowercase). This mutation blocks poly(A) elongation in embryos (50). Thus, these mRNAs enabled us to assess the effects of TGEs on translation in the absence of poly(A) or poly(A) metabolism. Translation was monitored by the same protocol as that used to prepare Fig. 1.

The level of translation of the reporter was unaffected by the presence of the TGEs (Fig. 2). To confirm that there is no difference in translation dependent on the TGEs for RNAs that lack a poly(A) tail, we performed luciferase assays. Luciferase activity was assayed at the 64-cell stage: the mRNAs with and without TGEs yielded equivalent luciferase activity (110,000 ± 10,000 U versus 125,000 ± 20,000 U, with and without TGEs, respectively). The mRNA lacking TGEs was translated less well than was its counterpart with a poly(A) tail and AAUAAA (compare Fig. 2, lanes 4 to 6, with Fig. 1, lanes 4 to 6), consistent with the stimulatory effect of poly(A) tails in Xenopus embryos (49, 50). The two mRNAs were comparably stable in embryos (not shown). We conclude that a poly(A) tail must be present for the TGEs to regulate translation of the injected reporters.

FIG. 2.

TGE-mediated translational repression requires a poly(A) tail. HA-tagged luciferase reporter mRNAs either contained the TGEs (lanes 1 to 3) or lacked the TGEs (ΔTGE) (lanes 4 to 6). Both mRNAs contained a mutant (AAgAAA) polyadenylation signal and no poly(A) tail. mRNAs were coinjected with HA-C100 (a control) into 1-cell embryos. The embryos were reinjected at the 64-cell stage with [35S]methionine-cysteine and incubated 1 hour before collecting and immunoprecipitating HA-tagged proteins. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

A Xenopus TGE-binding factor.

C. elegans extracts contain a factor that associates specifically with the tra-2 TGE (17). To determine whether such a factor was present in Xenopus eggs, we incubated radiolabeled tra-2 3′UTR RNAs in Xenopus egg extracts and analyzed RNA-protein complexes by native gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. These RNAs contain only the 3′UTR and adjacent polylinker sequences. Wild-type tra-2 RNA formed a specific complex that was not detected with an RNA lacking the TGEs (Fig. 3A). To examine further the binding specificity of this Xenopus factor, we tested the C. briggsae tra-2 3′UTR, which contains only a single TGE and forms a TGE-dependent complex in both C. elegans and C. briggsae extracts (23). Again, the wild-type tra-2 3′UTR from C. briggsae had a lower mobility in the presence of Xenopus egg extract (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 and 2); a mutant RNA that lacked the TGE did not form the complex efficiently (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4). Taken together, these results demonstrate that a factor in the Xenopus extract binds the TGE with a sequence specificity similar to that of the TGE-binding factor in C. elegans.

To determine whether TGEs are not only necessary but also sufficient for binding to the Xenopus factor, we prepared RNAs containing only the TGE sequences from C. elegans tra-2 (plus vector sequences). These RNAs contain either four tandemly duplicated TGEs or, as a control, lacked TGEs entirely (Fig. 3C). Complexes were detected readily on the RNA possessing four TGEs (Fig. 3C, lanes 1 and 2) and were not detected in the absence of the TGEs (Fig. 3C, lanes 3 and 4). Complexes formed less efficiently with the RNA possessing only four TGEs than with the entire 3′UTR, suggesting that other 3′UTR sequences can influence binding. We conclude that Xenopus egg extracts contain a TGE-specific binding factor, consistent with the presence of a TGE-dependent repression mechanism in the Xenopus embryo.

TGEs regulate poly(A) tail lengths in C. elegans.

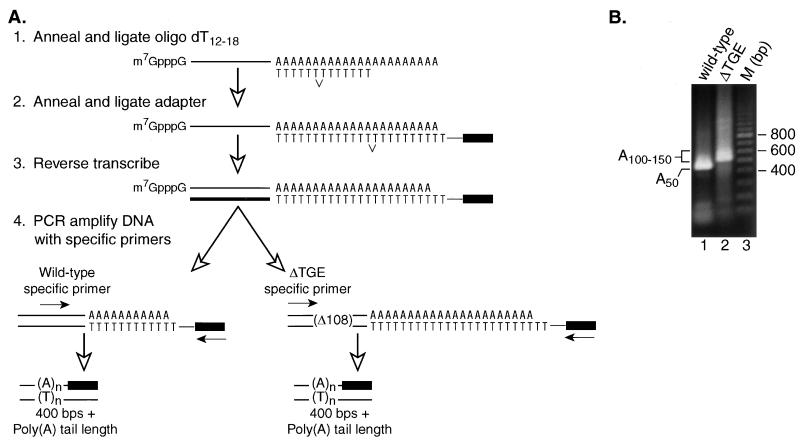

The finding that TGE-mediated repression requires the presence of a poly(A) tail (Fig. 1 and 2) suggests that TGEs might influence poly(A) tail length in C. elegans. To test this possibility, we analyzed endogenous tra-2 mRNAs isolated from wild-type worms and from mutant (gain-of-function) worms carrying a deletion in the tra-2 3′UTR that spans the TGEs (ΔTGE). Poly(A) lengths were assayed using the reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR)-based assay diagrammed in Fig. 4A (45). Primers for RT-PCR were designed to detect differences in poly(A) tail lengths. To compensate for the 108-nucleotide deletion in the 3′UTR of the gain-of-function allele, specific primers located at equal distances upstream of the 3′ ends were used for the wild-type or gain-of-function mRNAs. The primers were designed such that a tra-2 mRNA with no poly(A) tail, derived from either the wild-type or deletion mutant allele, would result in a product of 400 nucleotides.

FIG. 4.

C. elegans endogenous wild-type tra-2 mRNA has a shorter poly(A) tail than gain-of-function mRNA. (A) Diagram of the PAT assay used to measure endogenous poly(A) tail lengths. Primers were designed to result in products of equal sizes if poly(A) lengths are equivalent. A tra-2 mRNA having a poly(A) tail of A0 would result in a final product of 400 bp. (B) Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel containing the products of the PAT assay performed on either wild-type (lane 1) or gain-of-function (ΔTGE) (lane 2) worms. It is important to note that any length over 400 bp is contributed by the poly(A) tail. The length of the PCR product generated by a nonadenylated mRNA would be 400 bp. Lane 3 (M) contains a 100-bp ladder.

The presence of the TGEs in tra-2 mRNA reduced its poly(A) length in C. elegans (Fig. 4B). The RT-PCR products obtained from wild-type mRNA were approximately 50 to 100 nucleotides shorter than those derived from the gain-of-function mRNAs that lack the TGEs. The length of PCR products above 400 nucleotides corresponds approximately to the actual length of poly(A) on the mRNA (45). Thus, any differences in length correspond to differences in poly(A) tail lengths between the mRNAs. These data demonstrate that TGE-mediated translational repression is correlated with a reduction in poly(A) tail length of endogenous tra-2 mRNA in C. elegans.

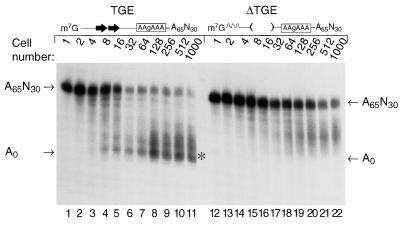

tra-2 TGEs promote rapid deadenylation in Xenopus embryos.

To test whether TGEs control deadenylation in vivo, capped and polyadenylated tra-2 3′UTR RNAs with or without TGEs were injected into Xenopus 1-cell embryos. These RNAs comprise the 3′UTR of tra-2 mRNA, plus a 65-nucleotide poly(A) tail (Fig. 5A). A 108-nucleotide polylinker sequence was inserted into the RNA from which the TGEs had been deleted, to compensate in length for the removal of the TGEs. To eliminate any possible effects of cytoplasmic polyadenylation, both RNAs carried a point mutation in the AAUAAA that abolishes the poly(A) addition reaction in oocytes and embryos (14, 33, 50). Synthetic RNAs were injected into fertilized 1-cell embryos. At various stages of development following injection, RNA was isolated and analyzed by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

The RNA that contained TGEs underwent rapid deadenylation (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 11). Fully deadenylated RNAs first appeared in the 4- to 8-cell embryo, after approximately 2.5 to 3 h (Fig. 5B, lanes 3 and 4); most RNAs were deadenylated by the 32-cell to 128-cell stages (Fig. 5B, lanes 6 through 8). In contrast, the majority of the RNAs lacking the TGEs (ΔTGE) were not fully deadenylated at any stage (Fig. 5B, lanes 12 through 22). Slow deadenylation that occurs in the absence of specific sequences has been observed in both oocytes and embryos (15, 30, 38, 54).

These data reveal that the TGEs affect deadenylation in at least two respects.

(i) Kinetics and distribution of products.

Shortly after injection, a minority of molecules carrying TGEs were fully deadenylated (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 through 4). In contrast, without the TGEs (ΔTGE), the entire population of RNA slowly and relatively synchronously underwent poly(A) shortening. One simple explanation of these data is that deadenylation of some or all of the wild-type RNA is processive, while that of the mutant is distributive. This possibility has not been tested rigorously, however.

(ii) Final lengths following deadenylation.

The majority of the RNA molecules carrying TGEs ultimately were completely deadenylated, while the RNA lacking TGEs (ΔTGE) retained a short poly(A) tail even at very long times after fertilization (Fig. 5B). To confirm these differences, RNAs isolated from 1,000-cell embryos were incubated with oligo(dT) and RNase H (Fig. 5C). The majority of the RNA that contained TGEs comigrated with an RNA lacking any adenosines, suggesting that it had been fully deadenylated or nearly so in vivo (Fig. 5C, lanes 1 and 2); in contrast, the oligo(dT)-RNase H-treated RNA that lacked TGEs (ΔTGE) migrated more slowly and possessed a poly(A) tail of approximately 15 to 40 adenosines (Fig. 5C, lanes 3 and 4). The efficiency of the oligo(dT)-RNase H treatment was confirmed using a synthetic RNA with a 65-nucleotide poly(A) tail (Fig. 5C, lanes 5 and 6).

Deadenylation in frog oocytes and embryos is impeded by the presence of a non-A tract after the poly(A) tail (15, 54). To test whether the TGEs could overcome such an impediment, we prepared RNAs identical to those in Fig. 5, but carrying a 30-nucleotide tract of polylinker sequence after the 65-nucleotide poly(A) tail (Fig. 6). These RNAs were injected into 1-cell Xenopus embryos, embryos were collected at various cell stages, and RNA was extracted and analyzed on a polyacrylamide gel. With RNAs that contain TGEs, fully and partially deadenylated products appeared by the 8- to 16-cell stage and accumulated thereafter (Fig. 6, lanes 1 to 11). In contrast, with the RNA lacking TGEs, deadenylation was very inefficient, and no fully deadenylated products were detected even at the 1,000-cell stage (Fig. 6, lanes 12 to 22). The fraction of RNA molecules that were susceptible to the deadenylation pathway was only slightly reduced for the TGE RNA (compared to Fig. 5); in contrast, the ΔTGE RNA was much less susceptible to deadenylation, leaving a greater fraction of the molecules full length. Thus, TGE-mediated deadenylation is not significantly impeded by the presence of nonadenylate nucleotides following the poly(A) tail. We cannot distinguish whether the activity responsible is an exonuclease or an endonuclease.

FIG. 6.

TGEs promote rapid deadenylation of an internal poly(A) tail. The sequence of the TGE (lanes 1 through 11) and ΔTGE (lanes 12 through 22) tra-2 RNAs used here are identical to those in Fig. 5A, except that they contain an additional 30 nucleotides of vector sequence following the poly(A) tail. RNAs were injected into 1-cell Xenopus embryos. Embryos were collected at various cell stages indicated. RNA was isolated and analyzed by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. The position of a fully deadenylated RNA is indicated by an asterisk.

We conclude that the TGEs regulate poly(A) length by affecting deadenylation. The presence of the TGEs accelerated deadenylation, caused the rapid appearance of fully deadenylated molecules, and permitted the last 15 adenosines to be removed, resulting in the accumulation of fully deadenylated products. Furthermore, the enhancement of deadenylation by TGEs enabled removal of even an internal poly(A) segment.

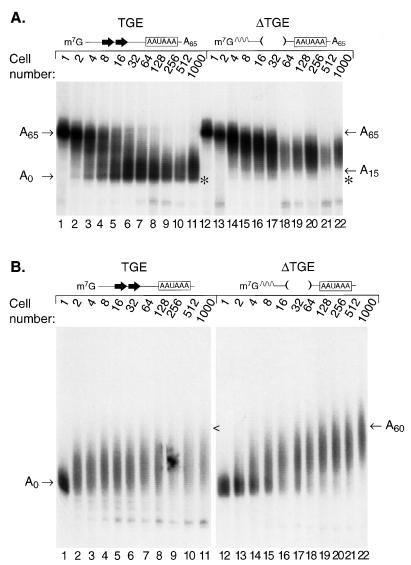

TGE-dependent deadenylation competes with cytoplasmic polyadenylation.

To determine whether TGEs promote rapid deadenylation in the presence of polyadenylation signals (AAUAAA), as would be found in the natural mRNA, wild-type and ΔTGE RNAs containing AAUAAA and a 65-nucleotide poly(A) tail were injected into 1-cell Xenopus embryos (Fig. 7A). The TGE tra-2 RNA underwent rapid and apparently processive deadenylation (Fig. 7A, lanes 1 through 11), while the ΔTGE tra-2 RNA did not (Fig. 7A, lanes 12 through 22). The pattern of reaction products containing AAUAAA or AAgAAA are similar (compare Fig. 5B to Fig. 7A). However, the final lengths of products with AAUAAA are longer by approximately 20 nucleotides, suggesting cytoplasmic polyadenylation.

FIG. 7.

tra-2 TGEs promote rapid deadenylation in Xenopus embryos in the presence of both competing reactions, cytoplasmic polyadenylation and deadenylation. (A) The sequences of the TGE (lanes 1 through 11) and ΔTGE (lanes 12 through 22) tra-2 RNAs used here are identical to those in Fig. 5A, except that they contain AAUAAA. RNAs were injected into 1-cell Xenopus embryos. The position of a fully deadenylated RNA is indicated by an asterisk. (B) tra-2 RNAs are substrates for polyadenylation. The RNAs used are identical to those in panel A, except that they lack a poly(A) tail as injected. TGE (lanes 1 through 11) and ΔTGE (lanes 12 through 22) tra-2 RNAs were injected into 1-cell Xenopus embryos. Embryos were collected at various cell stages as indicated. RNA was isolated and analyzed by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. The positions of RNAs with poly(A) tails of A0 or A60 are indicated. The position of the TGE RNA with an A60 poly(A) tail is indicated by the < symbol.

To test directly whether the tra-2 RNAs were substrates for polyadenylation and whether TGEs could overcome poly(A) addition, we injected RNAs identical to those in Fig. 7A except that they lacked a poly(A) tail (Fig. 7B). Both the RNAs with and without TGEs received short poly(A) tails. The RNA that lacked TGEs (ΔTGE) continued to increase gradually in poly(A) tail length throughout the time course, while the wild-type tra-2 RNA maintained a shorter poly(A) tail. We conclude that the tra-2 RNAs are substrates for cytoplasmic polyadenylation in Xenopus embryos and that their final differences in poly(A) tail length are due to differences in deadenylation rather than polyadenylation.

DISCUSSION

Mutations in the 3′UTR of tra-2 mRNA partially relieve translational repression of tra-2 mRNA in C. elegans and cause the hermaphrodite worm to switch to female (17). The work reported here permits three main conclusions. First, TGEs repress translation in Xenopus embryos but only if the mRNA carries a poly(A) tail. Second, a TGE-binding factor exists in Xenopus egg extracts. Third, TGEs promote rapid and complete deadenylation of tra-2 RNAs in frog embryos and cause tails to be shorter in C. elegans. We conclude that TGE-mediated translational repression requires either the poly(A) tail or changes in its length and that TGE-mediated repression and enhanced deadenylation is conserved between Xenopus and C. elegans.

TGEs and deadenylation.

Several lines of evidence demonstrate that TGEs stimulate deadenylation in fertilized Xenopus embryos. In experiments using synthetic 3′UTRs, TGEs accelerate the rate of poly(A) removal, cause the accumulation of deadenylated molecules, and confer the ability to remove an internal poly(A) segment. The effects on deadenylation are not likely to be due to a secondary consequence of inhibition of translation initiation or cap recognition, since no translational repression is observed in the absence of poly(A).

TGEs qualitatively alter the deadenylation reaction in a manner explicable by a shift from distributive and slow to processive and rapid. By definition, a processive deadenylase would associate with an RNA molecule and remove the entire poly(A) tail before disassociating, while a distributive deadenylase would associate with an RNA molecule and remove only a few adenosines before disassociating. Elements in the 3′UTR of certain growth factor and lymphokine mRNAs accelerate deadenylation in somatic cells, apparently conferring either processive or distributive characters to the reaction (6). In neither case have processive and distributive mechanisms been tested directly. A TGE-bound factor could confer processive character to the deadenylation reaction by stably recruiting a deadenylase or by inducing a TGE-dependent alteration in the RNP substrate that makes it more susceptible to complete and rapid deadenylation. Such an alteration might be removal of poly(A) binding protein. Alternatively, TGEs could cause endonucleolytic cleavage between the poly(A) tail and the body of the mRNA.

In addition to accelerating deadenylation, TGEs stabilize fully deadenylated molecules, such that they accumulate during early cleavage stages (e.g., Fig. 5B): in their presence, synthetic 3′UTR RNAs of equivalent lengths are stabilized three- to fourfold in the embryo (data not shown). AU-rich elements (AREs), such as those found in the 3′UTRs of c-myc and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor mRNAs, accelerate deadenylation and are thought to thereby destabilize the mRNA in mammalian cells (reviewed in references 6, 20, and 42). Similarly, AREs may cause translational repression in embryos (27, 32) through effects on deadenylation (58). Thus, both AREs and TGEs promote deadenylation and cause repression. A protein of the ELAV family, HuR, stabilizes deadenylated molecules by interacting with AREs in a recently developed in vitro system from mammalian cells (12). Similarly, overexpression of Hel-N1 or HuR can stabilize ARE-containing mRNAs in vivo (11, 21, 40). Two different factors may be involved in accelerating deadenylation and stabilizing the deadenylated species (12). The Xenopus embryo may contain analogous TGE-specific factors that both accelerate deadenylation and stabilize the product (this work). AREs behave very similarly in Xenopus embryos (58). Thus, the behavior of TGEs in the embryo is similar to that of AREs in embryos (58) and in the mammalian cell-free system (12). It is possible that common components participate in TGE- and ARE-dependent regulation, though no such common RNA-binding factors have yet been identified to our knowledge.

Systems that promote deadenylation appear to be highly conserved. TGE-mediated translational repression is conserved between species including C. elegans, C. briggsae, Xenopus, and mammals (23; this work). Similarly, AREs from mammalian cells accelerate deadenylation in amphibian embryos (58). Sequences in the Xenopus c-mos 3′UTR promote rapid deadenylation in embryos, as do 3′UTR elements in several other Xenopus maternal mRNAs (1, 5, 30, 39). Although the sequences of AREs, TGEs, and the c-mos elements are not obviously related, these diverse elements may act through similar mechanisms. In each case, the elements accelerate poly(A) loss in the Xenopus embryo and lead to reduced translational activity.

Translational regulation by TGEs.

TGEs repress translation in Xenopus through a mechanism that requires a poly(A) tail. This conclusion follows from the observations that reporter mRNAs that possess a poly(A) tail are repressed, while those that lack one are not (Fig. 1 and 2). Moreover, TGE-mediated repression does not require the tra-2 5′UTR, since it is observed in C. elegans and in Xenopus with mRNAs containing various 5′UTRs (17, 23; this report). The data are consistent with two mechanistic interpretations. First, a TGE-bound factor might interfere with a communication between the poly(A) tail and the 5′ end of the mRNA and the m7GpppG cap in particular. Subsequently, the poly(A) tail shortens, perhaps enhancing the repressed state. Alternatively, a TGE-bound factor might repress translation by promoting deadenylation, thereby decreasing the length of the poly(A) tail. Consistent with this hypothesis, injected mRNAs that acquire comparable length poly(A) tails, added in vivo, are not repressed (not shown).

Xenopus factors and natural substrates.

Recently, a TGE-binding factor, GLD-1, was identified in C. elegans using a yeast three-hybrid screen, and has been shown to specifically bind to TGEs and inhibit translation (22). GLD-1 is a member of the STAR family of RNA-binding proteins (reviewed in reference 55). The single known Xenopus STAR protein, identified as a homologue of mouse quaking, is expressed in embryonic neural tissue (64). It appears not to be the TGE-binding factor detected here, since it is undetectable in eggs or cleavage stage embryos and first appears in early gastrulation (63).

In Xenopus, TGE-mediated repression and deadenylation are detected after fertilization but not before, demonstrating that TGE function can be regulated in stage-specific fashion in vivo. The mode of regulation of TGE activity in C. elegans is unclear, but TGE-mediated repression is required to permit spermatogenesis (10, 48). In one simple model, TGE activity is controlled temporally. Initially, in hermaphrodites, TGEs would be active, causing rapid deadenylation and translational repression; later, TGE activity would be shut off, resulting in extension of the tail and activation of the mRNA. This mode of control would be analogous to the regulation of several mRNAs in vertebrate oocytes during meiotic maturation, in which short poly(A) tails are elongated to derepress the mRNA at specific times (reviewed in reference 41). Alternatively, the regulation of TGE activity might be sex specific, being active in XO males, but not in XX hermaphrodites. In this model, TGEs would reduce the level of tra-2 protein present in males, and thereby permit spermatogenesis. These two models are not mutually exclusive, and TGEs may repress expression constitutively.

The identity of the Xenopus mRNAs that are subject to the mode of repression seen with TGEs is not yet known. Although specific endogenous mRNAs are rapidly deadenylated during early frog development, the sequences that mediate that control (5, 30, 39) are not strikingly similar to those in the TGEs. The finding that the TGEs of mammalian GLI mRNAs can function in C. elegans (23) and that the TGEs of C. elegans tra-2 can function in Xenopus embryos (this report), strongly suggests that multiple mRNAs with different biological functions are targets of this widespread regulatory system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to members of the Wickens and Goodwin laboratories for scientific discussions and comments on the manuscript. We appreciate the help of the U.W. Biochemistry Media Lab in preparing figures.

Work in the Goodwin and Wickens laboratories is supported by the NIH (GM51836 to E.G. and GM31892 to M.W.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Audic Y, Omilli F, Osborne H B. Embryo deadenylation element-dependent deadenylation is enhanced by a cis element containing AUU repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6879–6884. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballantyne S, Bilger A, Astrom J, Virtanen A, Wickens M. Poly(A) polymerases in the nucleus and cytoplasm of frog oocytes: dynamic changes during oocyte maturation and early development. RNA. 1995;1:64–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker D D, Wang C, Moore J, Dickinson L K, Lehmann R. Pumilio is essential for function but not for distribution of the Drosophila abdominal determinant Nanos. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2312–2326. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beelman C A, Parker R. Degradation of mRNA in eukaryotes. Cell. 1995;81:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouvet P, Omilli F, Arlot-Bonnemains Y, Legagneux V, Roghi C, Bassez T, Osborne H B. The deadenylation conferred by the 3′ untranslated region of a developmentally controlled mRNA in Xenopus embryos is switched to polyadenylation by deletion of a short sequence element. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1893–1900. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C Y, Shyu A B. AU-rich elements: characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis D, Lehmann R, Zamore P D. Translational regulation in development. Cell. 1995;81:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickson K, Bilger A, Ballantyne S, Wickens M. Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor in Xenopus laevis oocytes is a cytoplasmic factor involved in regulated polyadenylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5707–5717. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doniach T. Activity of the sex-determining gene tra-2 is modulated to allow spermatogenesis in the C. elegans hermaphrodite. Genetics. 1986;114:53–76. doi: 10.1093/genetics/114.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan X C, Steitz J A. Overexpression of HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, increases the in vivo stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. EMBO J. 1998;17:3448–3460. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford L P, Watson J, Keene J, Wilusz J. ELAV proteins stabilize deadenylated intermediates in a novel in vitro mRNA deadenylation/degradation system. Genes Dev. 1999;13:188–201. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox C A, Sheets M D, Wahle E, Wickens M. Polyadenylation of maternal mRNA during oocyte maturation: poly(A) addition in vitro requires a regulated RNA binding activity and a poly(A) polymerase. EMBO J. 1992;11:5021–5032. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox C A, Sheets M D, Wickens M P. Poly(A) addition during maturation of frog oocytes: distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic activities and regulation by the sequence UUUUUAU. Genes Dev. 1989;3:2151–2162. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox C A, Wickens M. Poly(A) removal during oocyte maturation: a default reaction selectively prevented by specific sequences in the 3′UTR of certain maternal mRNAs. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2287–2298. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francis R, Barton M K, Kimble J, Schedl T. gld-1, a tumor suppressor gene required for oocyte development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;139:579–606. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin E B, Okkema P G, Evans T C, Kimble J. Translational regulation of tra-2 by its 3′ untranslated region controls sexual identity in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:329–339. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80074-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray N K, Wickens M. Control of translation initiation in animals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:399–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodgkin J A, Brenner S. Mutations causing transformation of sexual phenotype in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1977;86:275–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson A, Peltz S W. Interrelationships of the pathways of mRNA decay and translation in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:693–739. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain R G, Andrews L G, McGowan K M, Pekala P H, Keene J D. Ectopic expression of Hel Nq, an RNA binding protein, increases glucose transporter (GLUT 1) expression in 3T3 L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:954–962. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jan E, Motzny C K, Graves L E, Goodwin E B. The STAR protein, GLD-1, is a translational regulator of sexual identity in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 1999;18:258–269. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jan E, Yoon J W, Walterhouse D, Iannaccone P, Goodwin E B. Conservation of the C. elegans tra-2 3′UTR translational control. EMBO J. 1997;16:6301–6313. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones A R, Schedl T. Mutations in gld-1, a female germ cell-specific tumor suppressor gene in Caenorhabditis elegans, affect a conserved domain also found in Src-associated protein Sam68. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1491–1504. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozak M. At least six nucleotides preceding the AUG initiator codon enhance translation in mammalian cells. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:947–950. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozak M. The scanning model for translation: an update. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:229–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruys V, Marinx O, Shaw G, Deschamps J, Huez G. Translational blockade imposed by cytokine-derived UA-rich sequences. Science. 1989;245:852–855. doi: 10.1126/science.2672333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunkel T A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuwabara P E, Okkema P G, Kimble J. tra-2 encodes a membrane protein and may mediate cell communication in the Caenorhabditis elegans sex determination pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:461–473. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legagneux V, Omilli F, Osborne H B. Substrate-specific regulation of RNA deadenylation in Xenopus embryo and activated egg extracts. RNA. 1995;1:1001–1008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macdonald P M, Smibert C A. Translational regulation of maternal mRNAs. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:403–407. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marinx O, Bertrand S, Karsenti E, Huez G, Kruys V. Fertilization of Xenopus eggs imposes a complete translational arrest of mRNAs containing 3′UUAUUUAU elements. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGrew L L, Dworkin-Rastl E, Dworkin M B, Richter J D. Poly(A) elongation during Xenopus oocyte maturation is required for translational recruitment and is mediated by a short sequence element. Genes Dev. 1989;3:803–815. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muckenthaler M, Gunkel N, Stripecke R, Hentze M W. Regulated poly(A) tail shortening in somatic cells mediated by cap-proximal translational repressor proteins and ribosome association. RNA. 1997;3:983–995. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murata Y, Wharton R P. Binding of pumilio to maternal hunchback mRNA is required for posterior patterning in Drosophila embryos. Cell. 1995;80:747–756. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newport J, Kirschner M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos. I. Characterization and timing of cellular changes at the midblastula stage. Cell. 1982;30:675–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okkema P G, Kimble J. Molecular analysis of tra-2, a sex determining gene in C. elegans. EMBO J. 1991;10:171–176. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paillard L, Legagneux V, Osborne H B. Poly(A) metabolism in Xenopus laevis embryos: substrate-specific and default poly(A) nuclease activities are mediated by two distinct complexes. Biochimie. 1996;78:399–407. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paillard L, Omilli F, Legagneux V, Bassez T, Maniey D, Osborne H B. EDEN and EDEN-BP, a cis element and an associated factor that mediate sequence-specific mRNA deadenylation in Xenopus embryos. EMBO J. 1998;17:278–287. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng S-Y, Chen C-Y A, Xu N, Shyu A-B. RNA stabilization by the AU-rich element binding protein, HuR, an ELAV protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:3461–3470. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richter J D. Dynamics of poly(A) addition and removal during development. In: Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 481–503. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross J. mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:423–450. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.423-450.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sachs A B, Sarnow P, Hentze M W. Starting at the beginning, middle, and end: translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salles F J, Lieberfarb M E, Wreden C, Gergen J P, Strickland S. Coordinate initiation of Drosophila development by regulated polyadenylation of maternal messenger RNAs. Science. 1994;266:1996–1999. doi: 10.1126/science.7801127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salles F J, Strickland S. Rapid and sensitive analysis of mRNA polyadenylation states by PCR. PCR Methods Applic. 1995;4:317–321. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.6.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanger F, Coulson A R. The use of thin acrylamide gels for DNA sequencing. FEBS Lett. 1978;87:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schedl T, Kimble J. fog-2, a germ-line-specific sex determination gene required for hermaphrodite spermatogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1988;119:43–61. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheets M D, Fox C A, Hunt T, Vande Woude G, Wickens M. The 3′-untranslated regions of c-mos and cyclin mRNAs stimulate translation by regulating cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:926–938. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simon R, Tassan J P, Richter J D. Translational control by poly(A) elongation during Xenopus development: differential repression and enhancement by a novel cytoplasmic polyadenylation element. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2580–2591. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.St. Johnston D. The intracellular localization of messenger RNAs. Cell. 1995;81:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarun S Z, Jr, Sachs A B. Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J. 1996;15:7168–7177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tarun S Z, Jr, Wells S E, Deardorff J A, Sachs A B. Translation initiation factor eIF4G mediates in vitro poly(A) tail-dependent translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9046–9051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Varnum S M, Wormington W M. Deadenylation of maternal mRNAs during Xenopus oocyte maturation does not require specific cis-sequences: a default mechanism for translational control. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2278–2286. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vernet C, Artzt K. STAR, a gene family involved in signal transduction and activation of RNA. Trends Genet. 1997;13:479–484. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verrotti A C, Thompson S R, Wreden C, Strickland S, Wickens M. Evolutionary conservation of sequence elements controlling cytoplasmic polyadenylylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9027–9032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vize P D, Melton D A, Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Harland R M. Assays for gene function in developing Xenopus embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:367–387. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voeltz G K, Steitz J A. AUUUA sequences direct mRNA deadenylation uncoupled from decay during Xenopus early development. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7537–7545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wells S E, Hillner P E, Vale R D, Sachs A B. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol Cell. 1998;2:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wharton R P, Struhl G. RNA regulatory elements mediate control of Drosophila body pattern by the posterior morphogen nanos. Cell. 1991;67:955–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wickens M, Kimble J, Strickland S. Translational control of developmental decisions. In: Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 411–450. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wreden C, Verrotti A C, Schisa J A, Lieberfarb M E, Strickland S. Nanos and pumilio establish embryonic polarity in Drosophila by promoting posterior deadenylation of hunchback mRNA. Development. 1997;124:3015–3023. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zorn A M, Grow M, Patterson K D, Ebersole T A, Chen Q, Artzt K, Krieg P A. Remarkable sequence conservation of transcripts encoding amphibian and mammalian homologues of quaking, a KH domain RNA-binding protein. Gene. 1997;188:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00795-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zorn A M, Krieg P A. The KH domain protein encoded by quaking functions as a dimer and is essential for notochord development in Xenopus embryos. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2176–2190. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.17.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]