Abstract

E2F integrates and coordinates cell cycle progression with the transcription apparatus through its cyclical interactions with important regulators of cellular proliferation, such as pRb, cyclins, and cdk's. Physiological E2F is a heterodimeric transcription factor composed of an E2F and a DP family member, and while E2F proteins can stimulate proliferation, certain members of the family are known to be endowed with growth-inhibitory and tumor suppressor-like activity. We have investigated the product of the human mdm2 oncogene, hDM2, and report on its ability to regulate E2F-dependent apoptosis in a fashion that is independent of p53. hDM2 can prevent p53−/− cells from entering E2F-dependent apoptosis, an outcome that is dependent upon the presence of the DP subunit. Cells rescued from apoptosis possess lower levels of E2F subunits, although the rescued cells show an increase in DNA synthesis and possess enhanced viability that reflects cooperation between E2F-DP and hMD2. Furthermore, the regulation of E2F activity correlates with an hDM2-dependent effect on the intracellular distribution of DP-1, since hDM2 causes the nuclear accumulation of DP-1. The control of E2F by hDM2 therefore has certain parallels with the targeted degradation by MDM2 of p53. However, the domains in hDM2 required for the regulation of E2F activity can be distinguished from those necessary for p53 degradation, suggesting that control of E2F and p53 by hDM2 may be mechanistically distinct. These experiments define a new level of interplay between E2F and hDM2 whereby hDM2 has a profound impact on the physiological consequences of E2F activation. They suggest that the oncogenic properties of hDM2 may in part be mediated by an antiapoptotic activity that converts E2F from a negative to a positive regulator of cell cycle progression and thereby retains E2F at a level that contributes to a continual state of growth stimulation.

Murine double minute 2 (mdm2), which was first described as one of the genes amplified on the double minute chromosomes present in the spontaneously transformed BALB/c 3T3 murine cell line 3T3 DM (6), is an evolutionarily conserved gene whose protein product, MDM2, is endowed with growth-promoting activity. The overexpression of MDM2 can immortalize rodent primary fibroblasts and transform a variety of cell lines (14), and the human homologue of mdm2, hdm2, is frequently overexpressed in tumors (44). MDM2 can antagonize transcriptional activation by p53 (39) and p53-dependent growth arrest (8), which is mediated through the ability of the N-terminal region of MDM2 to bind to the N-terminal trans activation domain of p53 (7, 32, 39). Furthermore, mice deficient for mdm2 are not viable unless they lack the p53 gene (23, 33), suggesting that the regulation of p53 is an important physiological function of MDM2. In addition to its ability to antagonize p53-dependent transcription, MDM2 can promote the degradation of p53, apparently through a ubiquitin-dependent proteasome pathway (18, 28), and recent studies have shown that MDM2 undergoes nucleocytoplasmic export and continuously shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm, and a nuclear export signal (NES) in MDM2 may be involved in a similar export mechanism similar to that of the human immunodeficiency virus rev protein (10, 46). Some evidence has suggested that the inhibition of MDM2 export interferes with the ability of MDM2 to destabilize p53 (46).

Also, MDM2 has been shown to functionally interact with a number of other proteins, including the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein pRb (52), E2F (38), the ribosomal protein L5 (37), and the human TATA box binding protein (32), and the C-terminal RING finger in MDM2 may interact with RNA (13). Overall, it appears that although the regulation of p53 is an important target in mediating the oncogenic effects of MDM2, it is likely that additional proteins can be subject to control by MDM2.

The E2F family of transcription factors plays an important role in orchestrating early cell cycle progression (12, 30). Hypophosphorylated pRb, which is active in negative growth control, binds to E2F and thereafter becomes progressively phosphorylated during the cell cycle through the sequential activity of cdk's, with the subsequent release of E2F allowing the transcriptional activation of target genes required for the early cell cycle. In mammalian cells E2F is composed of one of six E2F family members bound to a DP family member (12, 29), in which the transcriptional activity of E2F is mediated through a C-terminal activation domain that is under the control of pRb or its relatives p107 and p130, proteins that physically interact with E2F in a heterodimer and in a temporally specific fashion (12). Many target genes that are subject to control by E2F have been identified. In general, these genes encode proteins that are required for cell cycle progression and, for example, include enzymes for DNA synthesis, such as dihyduofolate reductase, or regulatory proteins, such as cyclins A and E (50).

It has been shown that MDM2 can bind to pRb through a domain located in the C-terminal region of pRb which overlaps with a domain required for the interaction of pRb with E2F and for growth suppression (52). Furthermore, a direct interaction with both the E2F and DP subunits of the E2F heterodimer may be important in augmenting the response of E2F-regulated genes (38), and in p53−/− tumor cells, MDM2 can override pRb- or p107-induced growth arrest (11). In p53−/− Rb−/− cells MDM2 can mediate anchorage-independent growth, an effect that requires a domain in MDM2 suggested to be involved in E2F regulation (11). Therefore, considerable evidence supports a functional connection between MDM2 and E2F.

An overwhelming body of evidence has established a role for E2F in promoting proliferation, although certain E2F family members may also function as negative regulators of cell growth (12). For example, overexpression of E2F-1 promotes cell cycle progression and is sufficient to drive quiescent cells into S phase (22), and both E2F-1 and DP-1 can cooperate with an activated ras oncogene to transform cells (22). However, E2F-1−/− knockout mice suffer a significant increase in the incidence of tumors, arguing that E2F-1 is also endowed with growth-inhibitory and tumor suppressor activities (15, 52, 53). Indeed, this apparent dichotomous function of E2F-1 may be partially attributable to its apoptotic function, as the overexpression of E2F-1 can not only cause quiescent cells to enter S phase but also promote apoptosis (25, 45, 48, 51).

We have explored the regulation of apoptosis by E2F in different types of p53−/− cells and specifically addressed the influence of hDM2 on apoptosis. We find that hDM2 can prevent cells from entering E2F-dependent apoptosis and further that this outcome is critically dependent on the DP component of the E2F heterodimer. Cells that have been rescued from apoptosis by hDM2 contain lower levels of E2F, which we show is dependent on the presence of the DP subunit and on the ability of MDM2 to promote E2F degradation. Moreover, the regulation of E2F correlates with an hDM2-dependent influence on the nuclear accumulation of DP-1, suggesting that an altered intracellular distribution is important in mediating the physiological effects of hDM2. Most importantly, in rescued cells hDM2 and E2F-DP cooperate in promoting DNA synthesis and cell viability. These data define a new level of interplay between the pathways of control mediated by hDM2 and E2F that occurs independently of p53. Furthermore, they support a model whereby in tumor cells hDM2 can antagonize the apoptotic properties of E2F and thereby maintain E2F in a permanent state of growth stimulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection.

SAOS2 cells and early-passage p53−/− mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) (35) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. For transient transfections, immunostaining, and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) assays, about 3 × 105 SAOS2 cells or 2 × 105 p53−/− MEFs were seeded onto glass coverslips in 30-mm-diameter dishes and transfected 12 h later using the calcium phosphate procedure described previously (54), in which the total amount of transfected DNA was made equivalent with empty vector. The cells were transfected for 6 h, washed, and grown under low-serum conditions (0.2% fetal calf serum) for a further 18 h prior to being fixed for immunostaining, BrdU staining, or TUNEL assay. Transfection efficiency usually was between 18 and 24%.

Expression vectors.

The plasmids pCMVHA-HA-E2F-5 and pHA-E2F-5ΔTAD were described previously (1). The plasmid pCMVE2F-4, which encodes human E2F-4, was described previously (4). The plasmid pRcCMVHA-E2F-1wt, encoding human E2F-1, was a kind gift from W. Krek (26). Plasmids pG4-DP-1 and the DP-1 derivatives pG4DP3α, pG4DP3ΔE, pG4DP3ΔDEF, and pCMVβ gal have been previously described (3, 9, 31). Plasmid pC53-SN3, expressing wild-type p53 (2), and the hDM2 expression vectors (7, 8) have been previously described.

Apoptosis TUNEL assay and immunostaining.

Cells on coverslips were transfected as indicated in the figures and, at the appropriate time, fixed for 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature. The cells were permeabilized at 4°C for 2 min in 0.1% Triton X-100–0.1% sodium citrate and treated for an additional 10 min with 10% fetal calf serum in PBS. TUNEL staining (Boehringer Mannheim) for apoptotic cells was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. For immunostaining, the coverslips were incubated with the primary antibody for 30 min at room temperature and washed in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used at a 1:200 dilution, and mouse monoclonal antibodies were used at a 1:1,000 dilution unless otherwise stated. Secondary antibodies, either anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate- or tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated or anti-rabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate- or tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc.), were incubated for ′30 min at room temperature and washed in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin with 1 μg of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole)/ml to visualize nuclei. Transfected cells were identified by immunostaining them with an appropriate antibody, and the level of apoptosis is expressed relative to the number of cells transfected (antihemagglutinin [HA] was used to detect E2F-1, E2F-4, and E2F-5; anti-DP-1 was used to detect DP-1; and Ab-1 [Calbiochem] was used to detect hDM2); the data shown were derived from at least three independent experiments.

BrdU staining.

Following transfection and overnight incubation in 0.2% serum, cells were incubated with BrdU (Boehringer Mannheim) for between 5 and 10 min. The cells were fixed in 70% ethanol–2 mM glycine (pH 2.0) for 20 min at −20°C, and BrdU incorporation was detected according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfected cells were identified by immunostaining them with an appropriate antibody, and the level of BrdU incorporation was expressed relative to the total number of cells transfected.

Immunoblotting.

For immunoblotting, about 5 × 105 SAOS2 cells or 3.5 × 105 p53−/− MEFs were seeded in 60-mm-diameter dishes and transfected with plasmid as described above. The cells were harvested, snap frozen, and subsequently lysed in sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer before separation on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Protein loading was standardized by β-galactosidase activity (derived from transfected pCMVβ gal) and carried out as described previously (9). The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Colony assay.

For the colony assay, about 5 × 105 SAOS2 cells in 60-mm-diameter dishes were transfected with 12 μg of each plasmid. Equal amounts of neoresistant plasmid DNA were added to each transfection. The cells were transfected for 6 h, split, and grown in 10% DMEM with 0.5 mg of G418 (Sigma)/ml added on the third day to select for resistant colonies. Alternatively, following transfection, the cells were incubated for 18 h in low serum prior to being split and subjected to selection. The data shown were derived from three independent experiments.

Antibodies.

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to DP-1 and DP-3 have been described previously (9). Other primary antibodies used were the anti-E2F-1 mouse monoclonal antibody KH95 (Santa Cruz), anti-p53 mouse monoclonal antibody DO1 (Santa Cruz), the anti-MDM2 mouse monoclonal antibody Ab-1, and the anti-HA mouse polyclonal antibody (BabCo).

RESULTS

Apoptotic properties of E2F family proteins.

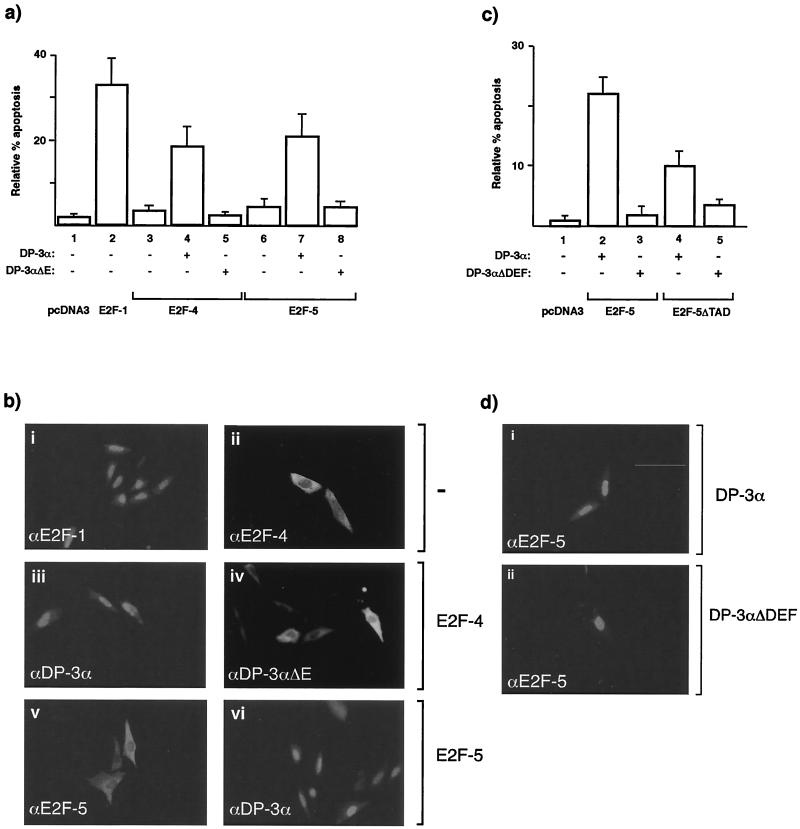

It is known that E2F-1 can induce apoptosis (45, 48, 51), but the properties of the other family members, such as E2F-4 and -5, have not been elucidated. To explore their apoptotic activities, we compared the properties of exogenous E2F-1 to those of E2F-4 and -5 in SAOS2 osteosarcoma cells into which E2F expression vectors were transfected under low-serum growth conditions (31). SAOS2 cells, which are p53−/− Rb−/−, undergo apoptosis upon the introduction of exogenous E2F-1 (45). By TUNEL assay, and consistent with previous reports, E2F-1 could promote apoptosis, whereas under the same conditions, E2F-4 and E2F-5 had negligible activity (Fig. 1a, compare bar 2 to 3 and 6).

FIG. 1.

Properties of E2F responsible for apoptosis. (a) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with 6 μg of E2F-1 (bar 2), 6 μg of E2F-4 (bar 3), or 6 μg of E2F-5 (bar 6) alone or with (+) 6 μg of DP3-α (bars 4 and 7) or 6 μg of DP3-αΔE (bars 5 and 8). After 6 h, the cells were washed and further grown overnight in 0.2% fetal calf serum in DMEM. Apoptosis was assayed ∼18 h after transfection, and apoptotic cells were quantitated as described in the text. The total amount of transfected DNA was made up with pcDNA3. The percentage of apoptosis is expressed relative to the total number of transfected cells, and the data shown represent the average values (+ standard deviations) from three independent experiments. (b) The intracellular distribution of the indicated E2F proteins was determined under apoptotic conditions after SAOS2 cells were transfected with 6 μg of E2F-1 (i), 6 μg of E2F-4 (ii), 6 μg of both E2F-4 and DP-3α (iii), 6 μg of both E2F-4 and DP-3αΔE (iv), 6 μg of E2F-5 (v), or 6 μg of both E2F-5 and DP-3α (vi) and treated as described. Anti-HA was used to detect E2F-1 (i), -4 (ii, iii, and iv), and -5 (v and vi). (c) SAOS2 cells were transfected with 6 μg of E2F-5 (bars 2 and 3) or 6 μg of E2F-5ΔTAD (bars 4 and 5) together with 6 μg of DP-3α (bars 2 and 4) or 6 μg of DP-3αΔDEF (bars 3 and 5) and treated as described for panel (a). (d) The intracellular distribution of the indicated proteins was determined under apoptotic conditions after SAOS2 cells were transfected with 6 μg of E2F-5 together with 6 μg of DP-3α (i) or DP-3ΔDEF (ii). The intracellular distribution of E2F-5 is shown.

In considering the properties of E2F-4 and -5 that might influence apoptosis, we evaluated the importance of nuclear accumulation (1, 9, 36). Since E2F-1 possesses an intrinsic nuclear localization signal (NLS) whereas E2F-4 and E2F-5 do not (1), we reasoned that the observed differences in apoptotic activity may reflect their distinct intracellular locations. We tested this idea by coexpressing E2F-4 and E2F-5 with a member of the DP family, the physiological heterodimeric partners of E2F proteins (3, 16), that contains an alternatively spliced NLS, referred to as DP-3α (1, 9, 42). When expressed alone, DP-3α failed to induce apoptosis (data not shown). However, in the presence of DP-3α, both E2F-4 and E2F-5 induced apoptosis (Fig. 1a, bars 4 and 7), a result suggesting that nuclear translocation and accumulation are necessary for E2F-dependent apoptosis; under these conditions, expressing DP-3α alone failed to induce apoptosis (data not shown). We confirmed this view by studying the effect of coexpressing either DP-1 (which lacks an intrinsic NLS [9]) or a mutant DP-3α protein, referred to as DP-3αΔE, which lacks a 16-residue sequence, known as the E region, that forms part of the bipartite NLS (9). Coexpression of either DP-1 or DP-3αΔE with E2F-4 or -5 failed to stimulate apoptosis (Fig. 1a, bars 5 and 8, and data not shown), arguing that nuclear E2F-4 and -5 heterodimers possess apoptotic activity.

The intracellular distribution (1, 9) for each of the E2F and DP components was verified in cells grown under low-serum conditions. In contrast to E2F-1, both E2F-4 and -5 were predominantly cytosolic (Fig. 1b, compare i with ii and v) but underwent nuclear accumulation when coexpressed with DP-3α and failed to do so with DP-3αΔE (Fig. 1b, compare ii with iii and iv and v with vi).

The results suggest that a nuclear E2F heterodimer can induce apoptosis. To examine other functionally relevant domains, we studied two mutant derivatives. The first possessed a deletion in the DEF region of DP-3α, which is a protein sequence conserved in all known DP proteins that is necessary for DNA binding but fails to affect dimerization with E2F family members (3). In the context of DP-3α, the mutation in DP-3αΔDEF leaves the NLS intact, as DP-3αΔDEF can undergo nuclear accumulation and recruit E2F-5 into nuclei (Fig. 1d, compare i with ii). For the second derivative, a mutant E2F-5 protein lacking the transcriptional activation domain, E2F-5ΔTAD, was studied. When coexpressed with wild-type E2F-5, DP-3αΔDEF failed to induce apoptosis (Fig. 1c, compare bars 2 and 3), suggesting that nuclear accumulation and dimerization are not sufficient and that DNA binding subunits are necessary for the induction of apoptosis. In contrast, E2F-5ΔTAD together with wild-type DP-3α retained apoptotic activity (Fig. 1c, compare bars 2 and 4), albeit at a lower level than that possessed by wild-type E2F-5 (Fig. 1c, compare bars 2 and 4).

These results extend previous studies of E2F-dependent apoptosis (21, 43). Specifically, they document the fact that apoptosis can be induced by E2F-4 and E2F-5 heterodimers and that nuclear localization and DNA binding of the E2F-DP heterodimer is necessary for apoptotic activity. In contrast, the transcriptional activation domain of E2F-5 is not necessary but rather augments apoptosis.

hDM2 overcomes E2F-mediated apoptosis in SAOS2 p53−/− cells.

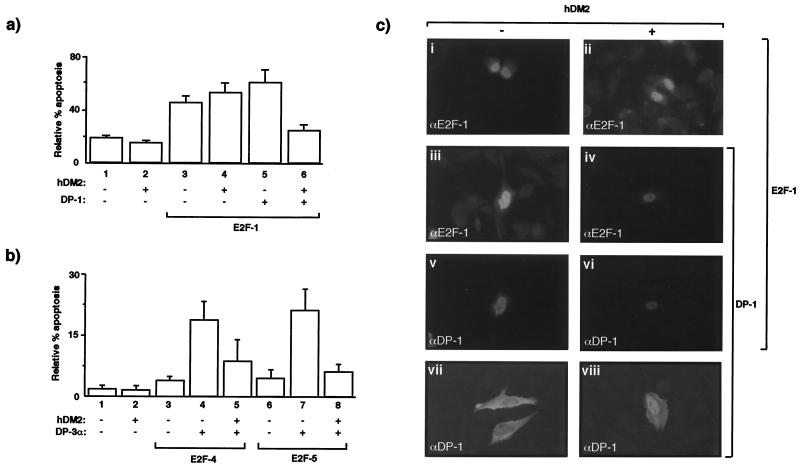

The fact that MDM2 activity is integrated with the pRb-E2F pathway of growth control (38, 52) prompted us to examine the possibility that hDM2 could alter the apoptotic activity of E2F; experiments were performed with p53−/− cells to rule out any influence of p53. For these studies, we capitalized on the information described above and in the first instance explored the influence of hDM2 on E2F-dependent apoptosis in SAOS2 cells. Therefore, hDM2 was expressed in cells undergoing apoptosis as a result of E2F-1 expression, and the level of apoptotic cells was compared to that of transfected cells expressing both components of the physiological heterodimer, namely E2F-1 and DP-1. We found that the apoptotic activity of E2F-1, when expressed alone, was not affected by hDM2, as the number of apoptosing cells remained at a level very similar to that caused by E2F-1 alone (Fig. 2a, compare bars 3 and 4), a result consistent with earlier studies, which established that hDM2 fails to overcome E2F-1-dependent apoptosis (21). Remarkably, however, although the level of apoptosis was only marginally greater when DP-1 and E2F-1 were coexpressed (Fig. 2a, compare bars 3 and 5), there was a highly significant decline in apoptosis upon the expression of hDM2 (Fig. 2a, compare bars 5 and 6), similar results being obtained with DP-3α (data not shown). Thus, hDM2 can down-regulate E2F-dependent apoptosis, but it does so in a fashion that reflects the presence of the DP subunit.

FIG. 2.

hDM2 overcomes E2F-dependent apoptosis in a DP subunit-dependent fashion in SAOS2 cells. (a) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with 6 μg of E2F-1 (bars 3 to 6), 6 μg of DP-1 (bars 5 and 6), or 6 μg of hDM2 (bars 2, 4, and 6). After 6 h, the cells were washed and grown overnight in 0.2% fetal calf serum in DMEM. Apoptosis was assayed ∼18 h after transfection, and apoptotic cells were quantitated as described in the text. The percentage of apoptosis is expressed relative to the total number of transfected cells, and the data shown represent the average values (+ standard deviations) from three independent experiments. +, present; −, absent. (b) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with 6 μg of E2F-4 (bars 3, 4, and 5) or E2F-5 (bars 6, 7, and 8) together with 6 μg of DP-3α (bars 4, 5, 7, and 8) and 6 μg of hDM2 (bars 2, 5, and 8) and treated as described for panel a. (c) The intracellular distribution of the indicated proteins was determined under apoptotic conditions after SAOS2 cells were transfected with the appropriate expression vectors encoding the indicated proteins as described in for panel a. Anti-HA was used to detect E2F-1, anti-DP-1 was used to detect DP-1, and anti-MDM2 was used to detect hDM2 (data not shown). The transfected expression vectors are indicated, and the immunostained protein is shown by white lettering. Note that iii and v, and iv and vi, show the same field stained with either anti-HA (iii and iv) or anti-DP-1 (v and vi) and that the images shown result from the same time of exposure.

To assess the generality of these observations, we extended our studies to the other E2F and DP family members. Under conditions where E2F-4 or E2F-5 cause apoptosis, namely, when coexpressed with the α isoform of DP-3 (Fig. 1a), the presence of hDM2 effectively reduced the level of apoptosis (Fig. 2b, compare bar 4 with 5 and 7 with 8). Since the apoptotic activity of E2F-4 and E2F-5 is dependent upon the presence of a DP protein (Fig. 1c), these results support the idea that the presence of a DP partner plays an important role in facilitating the antiapoptotic effects of hDM2.

As the intracellular location of the E2F heterodimer is a critical determinant in causing apoptosis (Fig. 1), we next assessed whether the antiapoptotic activity of hDM2 correlated with any alteration in the distribution or abundance of E2F. Coexpressing hDM2 with E2F-1 had no apparent effect on the distribution of E2F-1 (Fig. 2c, compare i and ii). Consistent with previous results (9), coexpressing DP-1 with E2F-1 caused DP-1 to undergo nuclear accumulation which, without E2F-1, was mostly cytosolic (Fig. 2c, compare v and vii). However, in cells expressing both E2F-1 and DP-1, the coexpression of hDM2 caused a marked reduction in the level of immunostaining arising from either DP-1 or E2F-1 (Fig. 2c, compare iii and v with iv and vi). These results suggest that hDM2 can influence the levels of E2F subunits and that it does so in a fashion that is dependent upon the presence of the DP subunit.

hDM2 down-regulates the levels of E2F and DP proteins.

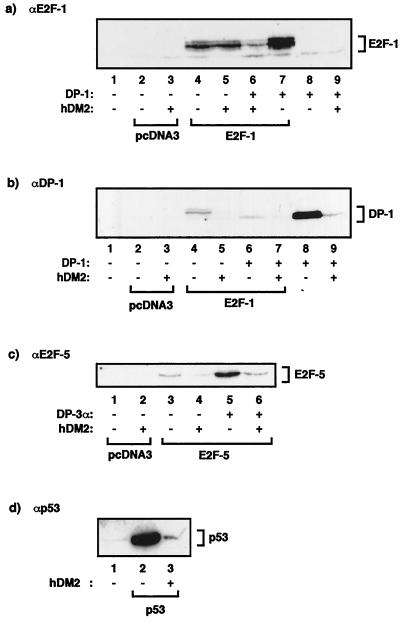

Since the immunostaining results (Fig. 2) suggested that hDM2 can down-regulate the levels of the E2F and DP subunits, we tested this idea by directly measuring E2F and DP levels under conditions of E2F-dependent apoptosis. Firstly, we studied the effects of hDM2 on E2F-1, either alone or together with DP-1. Although the presence of hDM2 failed to affect the level of E2F-1 (Fig. 3a, compare lanes 4 and 5), a clear reduction in E2F-1 was apparent in cells that coexpressed DP-1 (Fig. 3a, compare lanes 6 and 7), thus suggesting that a DP partner is necessary to allow hDM2 to modulate the levels of E2F-1. In contrast to E2F-1, the level of DP-1 was reduced either in the presence or absence of E2F-1 upon coexpressing hDM2 (Fig. 3b, compare lane 6 with 7 and lane 8 with 9), consistent with the idea that the DP subunit is the component in the E2F heterodimer that is targeted by hDM2.

FIG. 3.

hDM2 regulates the levels of E2F and DP subunits. (a and b) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with expression vectors encoding E2F-1 (12 μg; lanes 4, 5, 6, and 7) or DP-1 (12 μg; lanes 6, 7, 8, and 9) together with hDM2 (12 μg) as indicated. After 6 h, the cells were washed and further grown for ∼18 h in 0.2% fetal calf serum in DMEM. The cells were harvested and assayed for immunoblotting with anti-E2F-1 (a) or anti-HA for DP-1 (b) as described in the text. The band apparent in panel b, lane 4, results from a nonspecific reaction of the anti-HA antibody. (c) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with expression vectors encoding E2F-5 (12 μg; lanes 3, 4, 5, and 6) and DP-3α (12 μg; lanes 5 and 6) together with hDM2 (12 μg; lanes 2, 4, and 6) treated as described above and were immunoblotted with anti-HA for E2F-5. (d) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with expression vectors encoding p53 (12 μg; lanes 2 and 3) or hDM2 (12 μg; lane 3) treated as described above and were immunoblotted with anti-p53. For each of the experiments shown, the amount of extract loaded was determined by reference to the level of β galactosidase activity derived from pCMVβ gal (see Materials and Methods). +, present; −, absent.

Having established that hDM2 can regulate the levels of the E2F–DP-1 heterodimer, we examined the effect of hDM2 on E2F-5. Specifically, we coexpressed E2F-5 with DP3α to create conditions that favor apoptosis and where a functional influence on apoptosis by hDM2 was apparent (Fig. 2b). In a fashion similar to the effect of hDM2 on the E2F-1–DP-1 heterodimer, expressing hDM2 with E2F-5 caused a marked reduction in the levels of E2F-5 (Fig. 3c, compare lanes 5 and 6).

hDM2 can regulate the stability of p53 (18, 28). As a positive control, therefore, we monitored the effect of hDM2 on exogenous p53 in SAOS2 cells. As expected, there was a clear and significant reduction in the level of p53 in the presence of hDM2 (Fig. 3d, compare lanes 2 and 3).

Overall, a comparison of the effect of hDM2 on E2F-dependent apoptosis with the levels of E2F and DP proteins indicated that a correlation exists between the abilities of hDM2 to overcome apoptosis and to compromise the level of the E2F subunits. The results lend themselves to the suggestion that hDM2 may exert its antiapoptotic effect by stimulating a reduction in the level of the E2F heterodimer.

hDM2 modulates E2F activity in p53−/− MEFs.

As SAOS2 cells are human tumor cells which have sustained mutations in genes other than p53, such as Rb, it was important to establish that similar effects were observed in nontumorigenic p53−/− cells. To this end, we assessed the effect of hDM2 in early-passage MEFs in which the p53 gene had been knocked out through homologous recombination (35).

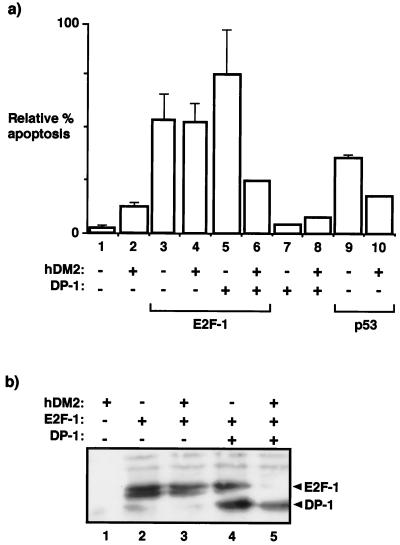

The introduction of E2F-1 into p53−/− MEFs stimulated apoptosis in a fashion similar to that observed in SAOS2 cells (Fig. 4a, compare bar 1 with 3), and the subsequent introduction of DP-1 together with E2F-1 marginally affected the level of apoptosis (Fig. 4a, compare bar 3 with 5). In contrast to the lack of effect of hDM2 on E2F-1-dependent apoptosis (Fig. 4a, compare bar 3 with 4), hDM2 caused a marked reduction in the apoptotic activity induced by E2F-1 and DP-1 (Fig. 4a, compare bar 5 with 6), an outcome that reflects the observations made in SAOS2 cells. As a control for hDM2 activity, the apoptosis induced in p53−/− MEFs upon the expression of wild-type p53 was significantly reduced upon the coexpression of hDM2 (Fig. 4a, compare bars 9 and 10).

FIG. 4.

hDM2 overcomes E2F-dependent apoptosis in p53−/− MEFs. (a) p53−/− MEFs were transfected with expression vectors encoding hDM2 (6 μg; bars 3, 4, 6, 8, and 10), E2F-1 (6 μg; bars 3, 4, 5, and 6), DP-1 (6 μg; bars 7 and 8), or p53 (6 μg; bars 9 and 10) as indicated. After 6 h, the cells were washed and grown overnight in 0.2% fetal calf serum in DMEM. Apoptosis was assayed ∼18 h after transfection, and the apoptotic cells were counted. The percentage of apoptosis is expressed relative to the total number of cells counted, and the data shown (+ standard deviations) were derived from two separate experiments. (b) p53−/− MEFs were transfected as indicated with expression vectors encoding hDM2 (12 μg; lanes 1, 3, and 5), E2F-1 (12 μg; lanes 2, 3, 4, and 5), or DP-1 (12 μg; lanes 4 and 5). The cells were treated as described in the legend to Fig. 3a and immunoblotted with anti-HA for E2F-1 and DP-1; E2F-1 and DP-1 are indicated. +, present; −, absent.

We measured the levels of E2F-1 and DP-1 in p53−/− MEFs in the presence and absence of hDM2. While E2F-1 levels were not affected by hDM2 (Fig. 4b, lanes 2 and 3), there was a clear and striking down-regulation of E2F-1 when hDM2 was coexpressed with E2F-1 and DP-1 (Fig. 4b, compare lanes 4 and 5). Overall, this analysis of the properties of E2F-dependent apoptosis in p53−/− MEFs indicates that apoptosis is regulated by hDM2 in a fashion similar to that observed in SAOS2 cells, namely, that for hDM2 to be able to rescue cells from undergoing E2F-dependent apoptosis, both subunits of the E2F heterodimer must be present.

hDM2 cooperates with E2F in DNA synthesis and colony-forming activity.

We reasoned that in overcoming E2F-dependent apoptosis, it was likely that hDM2 promoted cell cycle progression and enhanced cell viability. Therefore, we monitored the level of DNA synthesis through BrdU incorporation in cells grown under low-serum conditions. When expressed alone, either E2F-1 or DP-1 stimulated BrdU incorporation (Fig. 5c, compare bars 2 and 6), and coexpressing E2F-1 with DP-1 resulted in a level of BrdU incorporation similar to that with E2F-1 or DP-1 alone (Fig. 5c, compare bars 2, 4, and 6). However, although hDM2 had a small effect on BrdU incorporation in the presence of E2F-1, a marked induction was apparent when hDM2 was coexpressed with E2F-1 and DP-1 (Fig. 5c, bar 5), suggesting that in the presence of both subunits, hDM2 can stimulate a greater level of DNA synthesis than in the presence of either subunit alone.

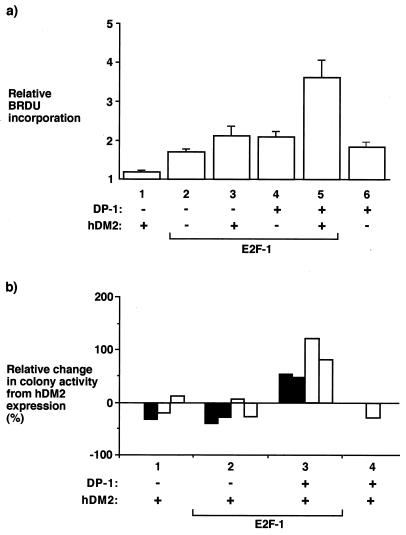

FIG. 5.

hDM2 regulation of E2F promotes DNA synthesis and confers a survival advantage. (a) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with expression vectors encoding E2F-1 (6 μg; bars 2, 3, 4, and 5) or DP-1 (6 μg; bars 4, 5, and 6) together with hDM2 (6 μg; bars 1, 3, and 5). After 6 h, the cells were washed and grown for ∼18 h in 0.2% fetal calf serum in DMEM. BrdU incorporation was assayed at ∼18 h as described in the text, and immunostaining was performed in parallel to determine transfection efficiency (data not shown). The BrdU incorporation was determined relative to the transfection efficiency, and the data shown represent the average values (+ standard deviations) from three independent experiments where the BrdU incorporation is expressed relative to the control treatment of pcDNA3-transfected cells. (b) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with expression vectors encoding E2F-1 (12 μg; bars 2 and 3), DP-1 (12 μg; bars 3 and 4), and hDM2 (12 μg; bars 1, 2, 3, and 4). After 6 h, the cells were washed and grown in either 0.2% (■) or 10% (□) fetal calf serum for ∼18 h, after which the cells were placed under G418 selection under normal culture conditions; each bar represents the average data from a single experiment involving duplicate treatments. The average number of colonies over three distinct experiments obtained after transfection with pcDNA3 was 588. The colonies were stained with crystal violet, and colony-forming activity is presented as the increase in colony numbers in the presence of hDM2 relative to the numbers in the absence of hDM2 in cells treated with the indicated expression vectors. +, present; −, absent.

As a further measure of the proliferative capacity of cells expressing E2F, DP, and hDM2, we performed a colony assay. A dramatic increase in colony formation was apparent in cells coexpressing E2F-1, DP-1, and hDM2 but not in cells expressing E2F-1 or DP-1 with or without hDM2 (usually between 50 and 100% [Fig. 5d]), an effect that was apparent in cells cultured in low or high serum levels. Thus, these results imply that the reduced level of E2F-dependent apoptosis caused by hDM2 correlates with increased DNA synthesis and enhanced cell viability, suggesting that rescued cells are endowed with a significant growth advantage. Moreover, as the enhanced colony-forming activity was only apparent when hDM2 was coexpressed with the E2F-DP heterodimer, the results imply that hDM2 and E2F-DP functionally cooperate in stimulating colony formation.

Domains in hDM2 required for the regulation of E2F activity.

We continued to analyze the mechanism through which hDM2 modulates the activity of the E2F heterodimer by examining the regions in hDM2 that are necessary for the observed effects on E2F-dependent apoptosis, colony formation, and altered protein level. We employed a number of mutant proteins derived from hDM2 (Fig. 6a) that have previously been examined for their regulatory effects on p53 activity (7). Thus, mutant hDM2Δ222–437 lacks most of the C-terminal half but retains the p53 binding domain, NLS, NES, and RING finger and has been reported to bind to p53, but it fails to affect the level of p53 protein (8, 28). hDM21–440 has a truncation in the C-terminal region and has wild-type activity for p53 regulation (8), and hDM2Δ59–89 possesses a deletion in the p53 interaction domain and fails to regulate p53 activity (7).

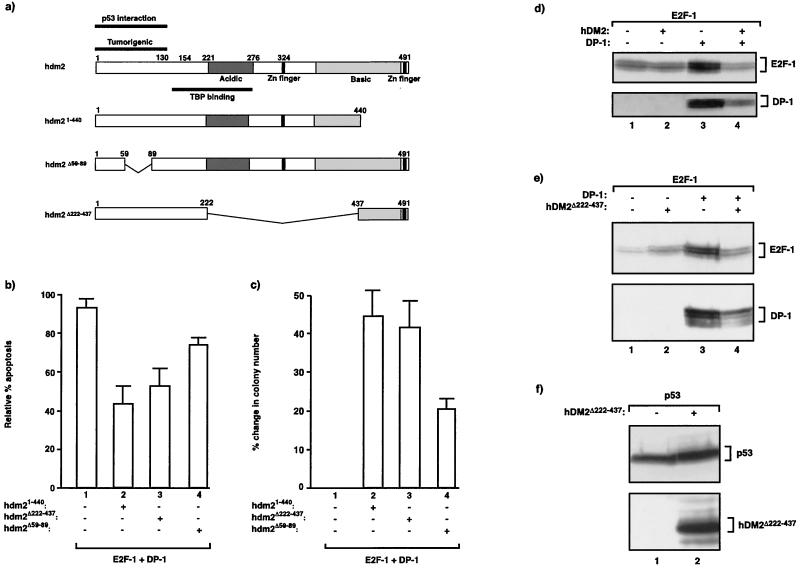

FIG. 6.

Domains in hDM2 required to regulate E2F. (a) Diagrammatic summary of wild-type hDM2 (indicating the relevant domains) and the hDM2 mutant derivatives. (b) SAOS2 cells were transfected under low-serum conditions as indicated with expression vectors encoding E2F-1 (6 μg) and DP-1 (6 μg) together with the hDM2 derivative hDM21–440, hDM2Δ222–437, or hDM2Δ59–89 (6 μg; bars 2, 3, and 4). Apoptotic cells were assayed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The values shown indicate the percent change in apoptotic activity relative to the control treatment (cells transfected with pcDNA3) and represent the average values (+ standard deviations) from three independent experiments. The control-treated cells usually showed less than 5% apoptosis. (c) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with expression vectors encoding E2F-1 (12 μg) and DP-1 (12 μg) together with the indicated hDM2 derivatives (12 μg; bars 2, 3, and 4) and treated as described (grown in 0.2% fetal calf serum) in the legend to Fig. 5b. The percent change in colony numbers was calculated as the colony activity in the presence of hDM2 relative to that in the absence of hDM2, and the data represent the average values (+ standard deviations) derived from three independent experiments. (d and e) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with expression vectors encoding E2F-1 (12 μg; lanes 1 to 4) and DP-1 (12 μg; lanes 3 and 4) together with wild-type hDM2 (d) or hDM2Δ222–437 (e) (12 μg; lanes 2 and 4). The cells were harvested and assayed by immunoblotting with anti-E2F-1 or anti-HA for DP-1 as indicated. (f) SAOS2 cells were transfected as indicated with expression vectors encoding p53 (12 μg; lanes 1 and 2) together with hDM2Δ222–437 (12 μg; lane 2). The cells were harvested and assayed by immunoblotting with anti-p53 or anti-MDM2 as indicated. The amount of extract loaded was determined by reference to the level of β galactosidase activity derived from pCMVβ gal. +, present; −, absent.

In a fashion similar to that of wild-type hDM2, both hDM21–440 and hDM2Δ222–437 could overcome apoptosis, whereas hDM2Δ59–89 rescued some cells from undergoing apoptosis but nevertheless was less efficient than the other mutants (Fig. 6b, compare bars 2, 3, and 4). In the colony assay, mutants hDM21–440 and hDM2Δ222–437 augmented colony formation as efficiently as wild-type hDM2, whereas hDM2Δ59–89, while causing a significant induction of colony formation, possessed reduced activity (Fig. 6c, compare bars 1, 2, and 3).

Next, we investigated the effects of the hDM2 mutants on the levels of E2F-1 and DP-1 under apoptotic conditions, where coexpression of wild-type hDM2 caused a marked reduction in the levels of both subunits (Fig. 6d). Data derived from one of the mutants, namely, hDM2Δ222–437, are presented. In comparison to wild-type hDM2, hDM2Δ222–437 affected the levels of E2F-1 and DP-1 to similar extents. Specifically, the increased level of E2F-1 apparent upon coexpression of DP-1 was significantly compromised by hDM2Δ222–437 (Fig. 6e, compare lanes 1, 3, and 4). In a fashion similar to that of wild-type hDM2, the effect of hDM2Δ222–437 was dependent upon the presence of DP-1, since little reduction in the E2F-1 level was apparent without a coexpressed DP subunit (Fig. 6e, compare lanes 1 and 2 with 3 and 4). The same effect was seen when the level of DP-1 was analyzed, as hDM2Δ222–437 caused a significant reduction in the DP-1 level (Fig. 6e, compare lane 3 to 4). As a control, we investigated the effect of hDM2Δ222–437 on exogenous p53 in SAOS2 cells. As expected from previous studies (28), hDM2Δ222–437 did not affect the level of p53 (Fig. 6f, compare lanes 1 and 2) despite high expression levels of the hDM2 mutant (Fig. 6f, lane 2). A similar analysis was performed with hDM2Δ59–89, where an effect upon the level of E2F-1 or DP-1 was not apparent (data not shown). (For a summary of the results from the analysis of hDM21–440 and hDM2Δ59–89, see Fig. 8c.)

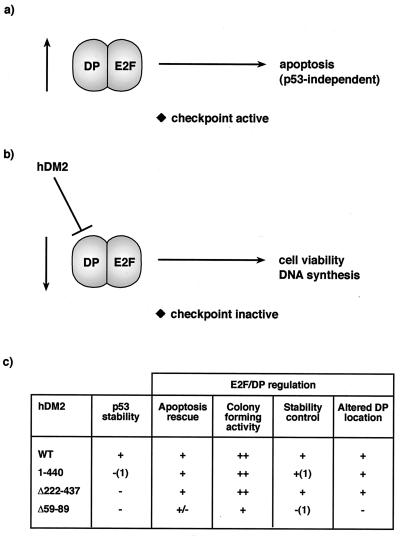

FIG. 8.

Model for regulation of E2F by hDM2. (a and b) It is envisaged that inappropriately high levels of E2F-DP activity cause the activation of a checkpoint pathway of control which thereafter leads to apoptosis (a). Since hDM2 can influence apoptosis by causing a reduction in E2F and DP subunit levels (b), it is suggested that this process may allow hDM2 to modulate checkpoint activity, limit apoptosis, and thereby facilitate cell cycle progression. The data suggest that the DP subunit is instrumental in enabling hDM2 to regulate E2F-dependent apoptosis. (c) Summary of the effects of hDM2 and mutant derivatives on E2F-DP regulation. (1), data not shown.

hDM2 modulates the intracellular location of DP-1.

The interaction between DP-1 and hDM2 (38) and the role of MDM2 in nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (46), combined with the data presented here, led us to consider the possibility that hDM2 can influence the intracellular location of DP-1. In the first instance, we performed the experiments with apoptotic cells coexpressing wild-type hDM2 and DP-1. As expected (9, 46), hDM2 was present predominantly in nuclei (Fig. 7a), whereas DP-1 was located mostly in the cytosol (Fig. 2 and 7a). In contrast, expressing hDM2 with DP-1 caused DP-1 to undergo a dramatic alteration in intracellular distribution: thus, although hDM2 possessed a nuclear location, a significant nuclear presence was observed for DP-1 (Fig. 7, compare b to d), suggesting that hDM2 can modulate the intracellular distribution of DP-1.

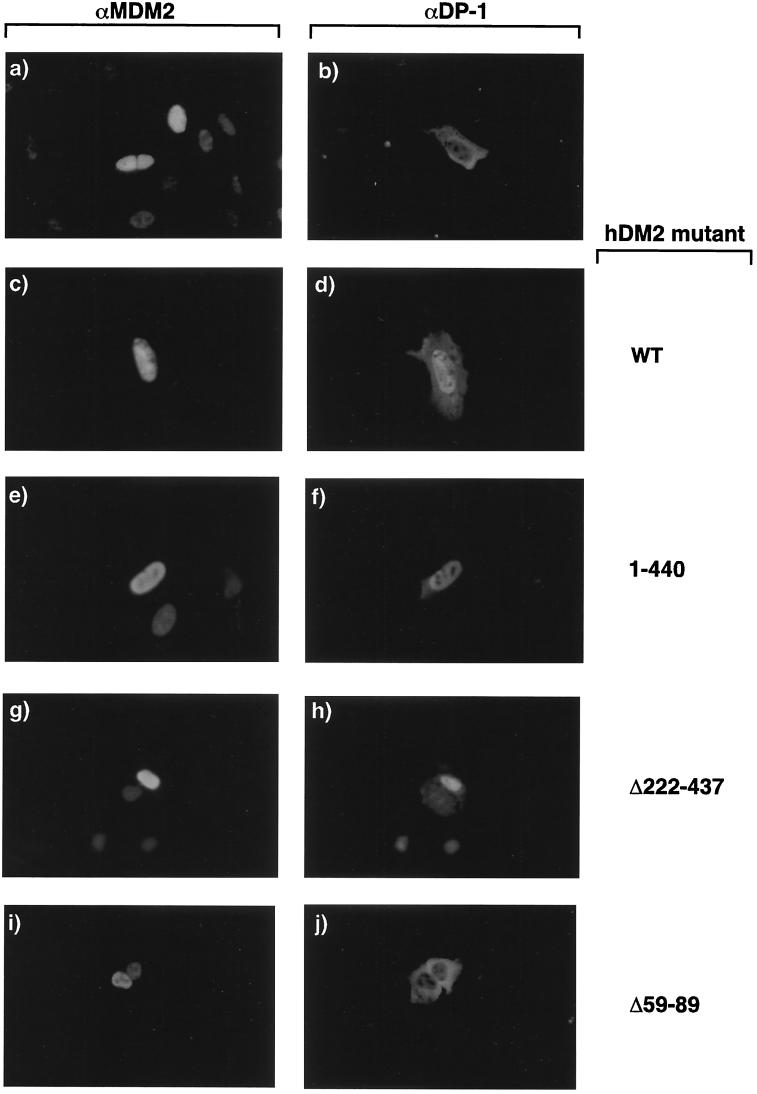

FIG. 7.

Influence of hDM2 on the intracellular distribution of DP-1. The intracellular distribution of the indicated proteins was determined under apoptotic conditions after SAOS2 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding hDM2 (6 μg) (a), DP-1 (6 μg) (b), or both hDM2 and DP-1 (6 μg each) (c, d, e, f, g, and h). The cells were treated as described in the text with anti-DP-1 (b, d, f, g, and h) and anti-MDM2 (a, c, e, g, and i). Panels a and b show different cells, whereas panels c and d, e and f, g and h, and i and j show the same cells stained with anti-MDM2 and anti DP-1, respectively; note that the images result from different exposure times. The hDM2 mutant derivatives are indicated. Similar results were obtained with U20S cells (data not shown).

We then studied the effect of the hDM2 mutant derivatives on DP-1 location. For this analysis, each mutant was coexpressed with wild-type DP-1, and thereafter, the influence on the intracellular location was determined in cells double stained with anti-MDM2 and anti-DP-1. Each of the hDM2 derivatives had an intracellular distribution similar to that of wild-type hDM2, possessing a mostly nuclear location (Fig. 7e, g, and i). In a fashion similar to that of wild-type hDM2, both hDM2Δ1–440 and hDM2Δ222–437 caused DP-1 to undergo nuclear accumulation (Fig. 7f and h). In contrast, hDM2Δ59–89 failed to affect the location of DP-1, as DP-1 remained cytosolic despite the nuclear presence of hDM2Δ59–89 (Fig. 7, compare i and j).

This analysis suggests that the ability of hDM2 to influence the nuclear accumulation of DP-1 may be functionally important for hDM2 in regulating the activity of the E2F heterodimer because a correlation exists between the ability of hDM2 to regulate E2F activity, namely, apoptosis and cell cycle progression, and the hDM2-stimulated nuclear accumulation of DP-1.

DISCUSSION

hDM2 overcomes E2F-dependent apoptosis.

A significant conclusion from the study reported here relates to the ability of hDM2 to overcome E2F-dependent apoptosis and the important role played by the DP subunit of the E2F heterodimer in facilitating the antiapoptotic effect of hDM2. This effect is exerted independently of the established role of hDM2 in regulating the p53 response (44), as most importantly, the ability of hDM2 to control E2F-dependent apoptosis was apparent in p53−/− cells. Furthermore, the data suggest that once cells have been rescued from apoptosis by hDM2, hDM2 and the E2F-DP heterodimer cooperate to enhance cell viability and cell cycle progression; thus, the data establish the fact that an antiapoptotic and growth-promoting activity of hDM2 may be channelled through a single cellular target. In a physiological setting, the results imply that hDM2 can alter the cellular consequences of deregulating the E2F pathway from the induction of apoptosis to that of growth stimulation, a process that may be critically important during tumorigenesis.

Of relevance to these results is the considerable body of evidence in support of the idea that the oncogenic properties of MDM2 proteins may be influenced by mechanisms other than the regulation of p53 activity. For example, the targeted expression of MDM2 to breast epithelial cells uncouples S-phase progression and causes multiple rounds of chromosomal replication, a process that is independent of p53 (34). Furthermore, mdm2 transcripts that lack the region encoding the p53 binding domain yet possess oncogenic activity have been isolated from human tumor cells (49), again suggesting that MDM2 can exert oncogenic activity independently of p53. It is possible, based on the information presented here, that the regulation of E2F activity by hDM2 plays a significant role in both of these situations.

Although physiological E2F DNA binding activity is a heterodimer composed of a DP and an E2F subunit (12), little information is available on the regulatory roles played by the DP subunit. At a generic level, the formation of the E2F-DP heterodimer augments DNA binding activity, transcriptional activity, and the interaction with pocket proteins, although the domains recognized by pocket proteins and the trans activation domain reside in the E2F subunit (29). The role described here for the DP subunit in allowing regulation of E2F-DP activity by hDM2 documents an example of a distinct role for the DP component. In this respect, it is noteworthy that earlier studies have addressed the regulation of E2F-1-dependent apoptosis by hDM2 and concluded that hDM2 has little influence on apoptotic activity (21), data that are consistent with the studies presented here (Fig. 2a). However, in a physiological context where E2F DNA binding activity normally exists as an E2F-DP heterodimer (12), the analysis documented in this study of the role played by the DP component is likely to be highly relevant.

In considering a possible explanation for the requirement for both components of the E2F-DP heterodimer in facilitating the rescue from apoptosis by hDM2, it is feasible that the phenomenon relates to different properties in the regulation of target genes by E2F-1 compared to E2F-1–DP-1. While E2F-1 can bind to the E2F consensus DNA binding site, the binding activity is stimulated upon formation of the E2F-1–DP-1 heterodimer (12). In contrast, the efficiencies of apoptosis induction by E2F-1 alone and by E2F-1–DP-1 appear to be similar (Fig. 2a). A potential model to explain these data therefore suggests that E2F-1 alone and E2F-1–DP-1 induce apoptosis through similar mechanisms. Following on, it is possible that the E2F-1 homodimer and the E2F-1–DP-1 heterodimer target a set of genes which is principally required to regulate apoptosis and that the presence of the DP subunit allows regulation by hDM2 and enhanced cell viability.

Previous studies that have addressed a role of MDM2 in E2F-dependent apoptosis were performed with p53−/− cells, where it was concluded that the inhibition of apoptosis caused by MDM2 was mediated through the ability of hDM2 to down-regulate p53 activity (25). More recently, it has been suggested that E2F-1 is up-regulated in a fashion similar to that of p53 in response to DNA damage and furthermore that MDM2 plays a role in this process (5). However, while these results are compatible with the data presented here, it is important to note that in contrast to these studies, our analysis was performed with p53−/− cells that lack wild-type p53 activity (both tumor cells and early-passage p53−/− MEFs) and therefore our results point towards a mechanism that operates independently of p53 in enabling hDM2 to monitor the status of E2F activity.

Does hDM2 regulate an S-phase checkpoint?

A variety of studies have ascribed both oncogenic and apoptotic activity to E2F (12). In this respect, given the important role that E2F plays in the control of proliferation, it makes considerable sense that cellular mechanisms should exist that monitor E2F and, in circumstances of aberrant control, stimulate apoptosis. Indeed, it is likely that E2F-dependent apoptosis represents a physiologically relevant process, as E2F-1−/− mice have defects in apoptosis during normal thymocyte ontogeny (15). Furthermore, the apoptosis seen in Rb−/− mice shows a clear tissue dependence on p53, as apoptosis is dependent upon p53 in the eye lens but is p53 independent in the peripheral nervous system (35, 40).

The properties of the E2F-DP transcription factor and its role in regulating early cell cycle progression, particularly entry into S phase, are consistent with a model in which inappropriately high levels of E2F-DP activity activate a pathway that induces apoptosis. There is a considerable body of evidence that supports the existence and functional importance of a pathway that monitors E2F-DP levels for the normal exit from S phase, and the suppression of such an S-phase checkpoint through the down-regulation of E2F-DP levels may be the basis of normal cell cycle progression (27).

The data presented here indicate that hDM2 can influence apoptotic activity but that it does so in a fashion that is dependent upon the DP component and, further, correlates with a reduction in the levels of the E2F and DP subunits. It is possible that high levels of E2F-1 activate a checkpoint pathway which eventually leads to apoptosis (Fig. 8a and b). As the levels of the E2F-DP subunits are down-regulated during progress through S phase (26, 27), one potential scenario to explain our results envisages that hDM2 either activates a process normally used by cells to regulate E2F-DP protein levels or mimics such an activity and that this process is necessary for cells to suppress the S-phase checkpoint and continue cell cycle progression.

hDM2 influences E2F-DP levels and augments E2F-dependent growth.

The ability of hDM2 to regulate the levels of E2F and DP correlated with the rescue of cells from apoptosis and induction of DNA synthesis. While it is necessary to clarify the mechanism involved in the down-regulation of E2F and DP subunits, it is noteworthy that the regulation of p53 by hDM2 involves a stimulation of ubiquitin-dependent degradation mediated by the E3 ligase-like activity in hDM2 (18, 28), and further, that the regulation of E2F and DP protein levels involves ubiquitin-dependent degradation (17, 19). It is consistent with this idea that the N-terminal region of hDM2, which is required for p53 regulation (39, 41), plays an important role in the regulation of E2F-DP activity, as the hDM2 derivative hDM2Δ59–89 has reduced capacity to control E2F-DP activity. It is possible that the p53 binding domain of hDM2 plays a wider role in mediating the effects of hDM2. However, despite these parallels between the regulation of p53 and that of E2F-DP, it is likely that each process is mechanistically distinct. This was most clearly suggested from studying hDM2Δ222–437, which cannot influence p53 levels (28) but possesses properties very similar to those of wild-type hDM2 in the control of the E2F-DP heterodimer.

Further evidence to support this viewpoint came from studies of the effect of hDM2 on the intracellular location of DP-1 which found that hDM2 can augment the nuclear accumulation of DP-1, a process that most likely results from a physical interaction between DP-1 and hDM2 (38). In contrast, the regulation of p53 by hDM2 has been suggested to involve nuclear export, as disruption of a candidate NES in hDM2 impairs the regulation of p53 activity by hDM2 (46). Therefore, although hDM2 can modulate the levels of both p53 and DP-E2F, and the processes involved may show certain similarities, they are nevertheless likely to be distinct.

We observed a good correlation between the domains in hDM2 required to overcome apoptosis and those responsible for enhanced cell viability in rescued cells (Fig. 8c). Given the role of E2F in stimulating apoptosis and promoting cell cycle progression (12), there is a clear possibility that hDM2 modulates E2F both to oppose apoptosis and to enhance cell viability, particularly because of the convergence between the hDM2 domains required for apoptosis rescue and enhanced cell viability and previous reports documenting the increased activity of E2F with hDM2 (38, 52).

In conclusion, the results reported here establish a new role for hDM2 which relates to the control of the E2F heterodimer. Specifically, hDM2 can alter the properties of E2F from a negative to a positive regulator of cell cycle progression. This effect occurs in p53−/− cells and therefore is exerted in a fashion that is independent of documented hDM2-p53 interaction. In tumor cells, where hdm2 undergoes increased expression, the physiological impact of this process is likely to be considerable. Thus, by targeting p53, hDM2 inactivates p53-stimulated apoptosis, while through its ability to regulate the apoptotic activity of E2F, it retains E2F in a growth-stimulating state. Given the importance of E2F in cell cycle control, the regulation of E2F reported here likely makes a highly significant and important contribution to the process of tumorigenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marie Caldwell for help in preparing the manuscript, Karen Vousden and Arnie Levine for reagents, and David Lane for the p53−/− MEFs. We thank the Medical Research Council for supporting this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen E K, de la Luna S, Kerkhoven R M, Bernards R, La Thangue N B. Distinct mechanisms of nuclear accumulation regulate the functional consequence of E2F transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2819–2831. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.22.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker S J, Markowitz S, Fearson E R, Willson J K U, Vogelstein B. Suppression of human colorectal-carcinoma cell-growth by wild type p53. Science. 1990;249:912–915. doi: 10.1126/science.2144057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandara L R, Girling R, La Thangue N B. Apoptosis induced in mammalian cells by small peptides that functionally antagonize the Rb-regulated E2F transcription factor. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:896–901. doi: 10.1038/nbt0997-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beijersbergen R L, Kerkoven R M, Zhu L, Carlee L, Voorhoeve P M, Bernards R. E2F4, a new member of the E2F gene family, has oncogenic activity and associates with p107 in vivo. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2680–2690. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blattner C, Sparks A, Lane D. Transcription factor E2F-1 is upregulated in response to DNA damage in a manner analogous to that of p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3704–3713. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cahilly-Snyder L, Yang-Feng T, Francke U, George D L. Molecular analysis and chromosomal mapping of amplified genes isolated from a transformed mouse 3T3-cell line. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1987;13:235–244. doi: 10.1007/BF01535205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Marechal V, Levine A J. Mapping of the p53 and mdm-2 interaction domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4107–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Wu X, Lin J, Levine A J. mdm2 inhibits the G1 arrest and apoptosis functions of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2445–2452. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de la Luna S, Burden M J, Lee C-W, La Thangue N B. Nuclear accumulation of the E2F heterodimer regulated by subunit composition and alternative splicing of a nuclear localization signal. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2443–2452. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.10.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobbelstein M, Roth J, Kimberly W T, Levine A J, Shenk T. Nuclear export of the E1B 55-kDa and E4 34-kDa adenoviral oncoproteins mediated by a rev-like signal sequence. EMBO J. 1997;16:4276–4284. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubs-Poterszman C, Tocque B, Wasylyk B. MDM2 transformation in the absence of p53 and abrogation of the p107 cell-cycle arrest. Oncogene. 1995;11:2445–2449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyson N. The regulation of E2F by pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2245–2262. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elenbaas B, Dobbelstein M, Roth J, Shenk T, Levine A J. The MDM2 oncoprotein binds specifically to RNA through its RING finger domain. Mol Med. 1996;2:439–451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fakharzadeh S S, Trusko S P, George D L. Tumorigenic potential associated with enhanced expression of a gene that is amplified in a mouse tumor cell line. EMBO J. 1991;10:1565–1569. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field S J, Tsai F-Y, Kuo F, Zubiaga A M, Kaelin W G, Jr, Livingston D M, Orkin S H, Greenberg M E. E2F-1 functions in mice to promote apoptosis and suppress proliferation. Cell. 1996;85:549–561. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girling R, Partridge J F, Burden N, Totty N F, Hsuan J J, La Thangue N B. A new component of the transcription factor DRTF/E2F. Nature. 1993;362:83–87. doi: 10.1038/362083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hateboer G, Kerkhoven R M, Shvarts A, Bernards R, Beijersbergen R L. Degradation of E2F by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: regulation by retinoblastoma family proteins and adenovirus transforming proteins. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2960–2970. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387:296–299. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman F, Martelli F, Livingston D M, Wang Z. The retinoblastoma gene product protects E2F-1 from degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2949–2959. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 1997;420:25–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh J-K, Fredersdorf S, Kouzarides T, Martin K, Lu X. E2F-1-induced apoptosis requires DNA binding but not transactivation and is inhibited by the retinoblastoma protein through direct interaction. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1840–1852. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson D G, Schwarz J K, Cress W D, Nevins J R. Expression of E2F-1 induces quiescent cells to enter S phase. Nature. 1993;365:349–352. doi: 10.1038/365349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones S N, Roe A E, Donehower L A, Bradley A. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature. 1995;378:206–208. doi: 10.1038/378206a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kowalik T F, DeGregori J, Schwartz J K, Nevins J R. E2F1 overexpression in quiescent fibroblasts leads to induction of cellular DNA synthesis and apoptosis. J Virol. 1995;69:2491–2500. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2491-2500.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kowalik T F, DeGregori J, Leone G, Jakoi L, Nevins J R. E2F-1-specific induction of apoptosis and p53 accumulation, which is blocked by Mdm2. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krek W, Ewen M E, Shirodkar S, Arany Z, Kaelin W G, Livingston D M. Negative regulation of the growth-promoting transcription factor E2F-1 by a stably bound cyclin A-dependent protein kinase. Cell. 1994;78:161–172. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krek W, Xu G, Livingston D M. Cyclin A-kinase regulation of E2F-1 DNA binding function underlies suppression of an S phase checkpoint. Cell. 1995;83:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubbutat M H G, Jones S N, Vousden K H. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam E, La Thangue N B. DP and E2F proteins: co-ordinating transcription with cell cycle progression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:859–866. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.La Thangue N B. DRTF1/E2F: an expanding family of heterodimeric transcription factors implicated in cell-cycle control. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:108–114. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee C-W, Sørensen T S, Shikama N, La Thangue N B. Functional interplay between p53 and E2F through co-activator p300. Oncogene. 1998;16:2695–2710. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leng P, Brown D R, Debs S, Deb S P. The human oncoprotein MDM2 binds to the human TATA-binding protein in vivo and in vitro. Int J Oncol. 1995;6:251–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luna R M, Wagner D S, Lozano G. Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature. 1995;378:203–206. doi: 10.1038/378203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundgren K, Moutes de Oca Luna R, McNeil Y B, Emerick E P, Spencer B, Barfield C R, Lozano G, Rosenberg M P, Finlay C A. Targeted expression of MDM2 uncouples S phase from mitosis and inhibits mammary gland development independent of p53. Genes Dev. 1997;11:714–725. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macleod K F, Hu Y, Jacks T. Loss of Rb activates both p53-dependent and independent cell death pathways in the developing mouse nervous system. EMBO J. 1996;15:6178–6188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magae J, Wu C L, Illenye S, Harlow E, Heintz N H. Nuclear localization of DP and E2F transcription factors by heterodimeric partners and retinoblastoma protein family members. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1717–1726. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marechal V, Elenbaas B, Piette J, Nicolas J C, Levine A J. The ribosomal L5 protein is associated with mdm-2 and mdm-2-p53 complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7414–7420. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin K, Trouche D, Hagemeier C, Sørensen T S, La Thangue N B, Kouzarides T. Stimulation of E2F1/DP1 transcriptional activity by MDM2 oncoprotein. Nature. 1995;375:691–694. doi: 10.1038/375691a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Momand J, Zambetti G P, Olson D C, George D L, Levine A J. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with p53 and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morgenbesser S D, Williams B O, Williams T, DePinho R A. p53 dependent apoptosis produced by Rb-deficiency in the developing lens. Nature. 1994;371:72–74. doi: 10.1038/371072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliner J D, Pietenpol J, Thiagalingam S, Gyuris J, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 1993;362:857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ormondroyd E, de la Luna S, La Thangue N B. A new member of the DP family, DP-3, with distinct protein products suggests a regulatory role for alternative splicing in the cell cycle transcription factor DRTF/E2F. Oncogene. 1995;11:1437–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips A C, Bates S, Ryan K M, Helin K, Vousden K H. Induction of DNA synthesis and apoptosis are separable functions of E2F-1. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1853–1856. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piette J, Neel H, Maréchal V. Mdm2: keeping p53 under control. Oncogene. 1997;15:1001–1010. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qin X-Q, Livingston D M, Kaelin W G, Adams P D. Deregulated transcription factor E2F-1 expression leads to S-phase entry and p53-mediated apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:10918–10922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roth J, Dobbelstein M, Freedman D A, Shenk T, Levine A J. Nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of the hdm2 oncoprotein regulates the levels of the p53 protein via a pathway used by the human immunodeficiency virus rev protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:554–564. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shan B, Farmer A A, Lee W-H. The molecular basis of E2F-1/DP-1 induced S-phase entry and apoptosis. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:689–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shan B, Lee W H. Deregulated expression of E2F-1 induces S-phase entry and leads to apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8166–8173. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sigalas I, Calvert A H, Anderson J J, Neal D E, Lunec J. Alternatively spliced mdm2 transcripts with loss of p53 binding domain sequences: transforming abilities and frequent detection in human cancer. Nat Med. 1997;2:912–915. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slansky J E, Farnham P J. Introduction to the E2F family: protein structure and gene regulation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;208:1–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79910-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu X, Levine A J. p53 and E2F-1 co-operate to mediate apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3602–3606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao Z H, Chen J, Levine A J, Modjathedi N, Xing J, Sellers W R, Livingston D M. Interaction between the retinoblastoma protein and the oncoprotein MDM2. Nature. 1995;375:694–698. doi: 10.1038/375694a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamasaki L, Jacks T, Bronson R, Goillot E, Harlow E, Dyson N J. Tumor induction and tissue atrophy in mice lacking E2F-1. Cell. 1996;85:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zamanian M, La Thangue N B. Adenovirus E1a prevents the retinoblastoma gene product from repressing the activity of a cellular transcription factor. EMBO J. 1992;11:2603–2610. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]