Abstract

The stress-activated protein kinases (SAPKs, also called c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases) and the p38s, two mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) subgroups activated by cytokines of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family, are pivotal to the de novo gene expression elicited as part of the inflammatory response. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) is a MAPK kinase kinase (MAP3K) that activates both the SAPKs and p38s in vivo. Here we show that TNF receptor (TNFR) associated factor 2 (TRAF2), an adapter protein that couples TNFRs to the SAPKs and p38s, can activate ASK1 in vivo and can interact in vivo with the amino- and carboxyl-terminal noncatalytic domains of the ASK1 polypeptide. Expression of the amino-terminal noncatalytic domain of ASK1 can inhibit TNF and TRAF2 activation of SAPK. TNF can stimulate the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the redox-sensing enzyme thioredoxin (Trx) is an endogenous inhibitor of ASK1. We also show that expression of TRAF2 fosters the production of ROS in transfected cells. We demonstrate that Trx significantly inhibits TRAF2 activation of SAPK and blocks the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction in a reaction reversed by oxidants. Finally, the mechanism of ASK1 activation involves, in part, homo-oligomerization. We show that expression of ASK1 with TRAF2 enhances in vivo ASK1 homo-oligomerization in a manner dependent, in part, upon the TRAF2 RING effector domain and the generation of ROS. Thus, activation of ASK1 by TNF requires the ROS-mediated dissociation of Trx possibly followed by the binding of TRAF2 and consequent ASK1 homo-oligomerization.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is a cytokine that elicits a wide variety of inflammatory responses, including fever, shock, cachexia, and the hemorrhagic necrosis of certain tumors. TNF likely plays a key role in the pathogenesis of a number of important clinical conditions, including septic shock, arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and, possibly, type 2 diabetes mellitus. At the cellular level, TNF can promote apoptosis, cell growth, lymphocyte development, leukocyte adhesion and extravasation, induction of additional cytokines, and secretion of inflammatory mediators (38).

Many of the cellular responses to TNF require de novo gene expression. Two key transcription factors regulated by TNF are nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and activator protein 1 (AP-1) (3, 39). AP-1 is a heterodimer that typically consists of c-Jun and either a member of the Fos or activating transcription factor family. AP-1 is regulated directly by phosphorylation and indirectly by mechanisms that elevate the transcription of AP-1 constituent components. Protein kinases of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family are involved in both aspects of AP-1 regulation (13, 14).

At the heart of all MAPK pathways are so-called core signaling modules, wherein the MAPKs are activated by Tyr and Thr phosphorylation catalyzed by members of the MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase (MEK) family. MEKs, in turn, are activated by Ser/Thr phosphorylation catalyzed by a divergent array of protein kinases collectively referred to as MAPK kinase kinases (MAP3Ks) (14).

The stress-activated protein kinases (SAPKs; also called c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases [JNKs]) and the p38s are two MAPK subfamilies pivotal to the regulation of AP-1 and, therefore, gene expression in response to TNF and related cytokines. The SAPKs are activated by at least two MEKs: SAPK/ERK kinase 1 (SEK1) and MAPK kinase 7 (MKK7). Likewise, the p38s are activated by at least two MEKs, MKK3 and MKK6. Thus far, 11 MAP3Ks have been identified as upstream activators of the SAPKs and p38s. While some of these MAP3Ks are specific for a single pathway, others display considerable promiscuity with regard to their downstream targets (8, 12, 14, 37). Although many MAP3Ks have been identified as regulators of the SAPKs and p38s and despite the fact that a number of potential protein-protein interaction partners for these MAP3Ks have been identified, little is known of the molecular mechanisms of MAP3K regulation—which is key to understanding how MAP3K → MEK → MAPK core modules couple to events at the cell membrane.

Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) is a MAP3K that can activate both the SAPKs (via activation of SEK1) and the p38s (via activation of MKK3 and MKK6). In addition, ASK1 can promote apoptosis when expressed in certain cell lines (11). ASK1 itself is activated in vivo by TNF and, possibly, Fas (4, 6, 11, 28, 32). Recent insight into the mechanism of ASK1 activation by TNF came with the observation that ASK1 could physically associate with adapter polypeptides that transduce signals from TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1). Thus, the carboxyl-terminal noncatalytic domain of ASK1 has been shown to interact in vivo with TNFR-associated factor 2 (TRAF2), an adapter protein that is required for coupling TNFR1 to the SAPKs (1, 7, 16, 28, 41). ASK1 can also associate with TRAF5 and -6, additional TRAFs implicated in the regulation of the SAPKs by members of the TNF superfamily (7, 28). ASK1 has also been shown to bind and be activated by Daxx, an adapter protein originally thought to relay signals from Fas to the SAPKs (4, 40). However, establishment of a function for Daxx has been controversial; several recent studies indicate that Daxx is nuclear (ASK1 is predominantly cytosolic) and, in fact, does not associate with Fas (11, 25, 36). Still, a role for Daxx in signaling to ASK1 and the SAPKs cannot be ruled out at this time; some investigators reliably observe that Daxx can activate both ASK1 and the SAPKs (4, 40), while others do not observe SAPK activation upon overexpression of Daxx (36).

The activation of ASK1 by TRAF2 appears to constitute one of several parallel pathways by which TRAFs recruit the SAPKs. Thus, TRAF2 also signals to the SAPKs through germinal center kinase (GCK) and GCK-related (GCKR), members of the GCK family, by a process that is independent of ASK1 and involves the binding of GCK/GCKR to TRAF2 and to the SAPK-specific MAP3K MEK kinase 1 (MEKK1) (15, 34, 35, 42). TRAF2 can also interact with MEKK1 in the absence of coexpressed GCK/GCKR by a process that involves the oligomerization of TRAF2 at receptor complexes (2). The interrelationship between TRAFs and GCKs in the regulation of MEKK1 is unclear.

Treatment of cells with TNF can foster the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (5), and the protein disulfide oxidoreductase thioredoxin (Trx) is an endogenous ASK1 inhibitor that directly binds to the ASK1 amino-terminal noncatalytic domain and blocks activation of ASK1 by TNF (32). Trx binding to ASK1 is substantially reversed by ROS, suggesting that stimuli such as TNF, which generate ROS, activate ASK1 in part by promoting Trx dissociation (32). Although overexpressed TRAF2 can activate ASK1 (28), the mechanism by which TRAF2 activates ASK1 in the presence of Trx is unknown, given that endogenous Trx is more abundant in the cell than is endogenous TRAF2 (1, 9, 10, 31). Thus, it is unclear if TRAF2 binding to ASK1 is followed by Trx dissociation or if Trx dissociation from ASK1 is a prerequisite for TRAF2 binding. Moreover, once TRAF2 binds ASK1, the mechanisms by which TRAF2 activates ASK1 are unclear, although evidence (6) indicates that ASK1 is activated in part by homo-oligomerization.

Here we show that TRAF2 activates ASK1 in vivo and interacts not only with the carboxyl-terminal noncatalytic domain of ASK1 but with the 460 amino-terminal amino acids (aa) of ASK1—a domain of the ASK1 polypeptide which overlaps with that implicated in Trx binding (32). Activation of the SAPKs by both TNF and TRAF2 is blocked upon expression of ASK1[1-460], suggesting that this previously undetected amino-terminal TRAF2 binding site is physiologically relevant. Endogenous levels of Trx exceed those of TRAF2 (9, 10, 31). TNF can trigger the production of ROS in target cells. We demonstrate that this process may be TRAF2 dependent inasmuch as ectopic expression of TRAF2 leads to the production of ROS. We present evidence that the interaction between endogenous or recombinant TRAF2 and ASK1 is redox sensitive and can be prevented with free radical scavengers. We also show that ectopic expression of Trx in excess of coexpressed TRAF2 almost completely inhibits the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction in a process that is reversed by ROS. Activation of ASK1 involves, in part, stimulus-dependent ASK1 homo-oligomerization, and overexpressed ASK1 spontaneously oligomerizes in vivo. Moreover, coumermycin-dependent forced dimerization of DNA gyrase-ASK1 fusions activates coexpressed SAPK (6). We observe that expression of TRAF2 increases the recovery of stable ASK1 oligomers from transfected cells in a process reversed by free radical scavengers, suggesting that ASK1 oligomerization is fostered by TRAF2 in a ROS-dependent manner. From these results, we conclude that activation of ASK1 by TRAF2 requires the ROS-dependent dissociation of Trx and binding of TRAF2. This is followed by TRAF2-dependent ASK1 activation coincident with ASK1 oligomerization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, transfections, and stimulation.

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium–10% fetal calf serum. Cells were transfected with the plasmids indicated below and in the figures, at the concentrations indicated below and in the figures; Lipofectamine (Gibco-BRL) was used, according to the manufacturer's instructions, for all transfections. Cells were harvested 16 to 20 h after transfection. As indicated, cells were treated with human TNF (100 ng/ml, 15 min; Boehringer Mannheim), H2O2 (10 mM, 20 min), or N-acetyl cysteine (Nac; 5 mM, 16 h) as indicated in the figures. L929 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium–10% calf serum and treated with TNF and Nac as previously described (28, 32).

Plasmid constructs.

pEBG (glutathione S-transferase [GST]-tagged) human TRAF2 and rat SAPK-p54α1, as well as influenza hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged rat SAPK-p46β1 (in pMT3), pcDNA3-HA and Myc-human ASK1, FLAG- and Myc-human TRAF2, and FLAG-human Trx have been described (28, 32, 42). HA-human ASK1 truncation constructs in pMT3 were generated by PCR using standard methods (33). Trx was amplified from human placental cDNA by PCR and cloned into pCMV5-Myc as a Myc-tagged construct.

Coimmunoprecipitation and kinase assays.

Coimmunoprecipitations of recombinant proteins were performed as previously described (42). HA-SAPK or GST-SAPK were assayed as immobilized complexes as previously described (42) by using c-Jun[1-135] as a substrate. Coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous ASK1 and TRAF2 from L929 cells was performed as previously described (28).

Measurement of ROS.

293 cells were cultured in six-well plates and transfected in triplicate with vector, FLAG-TRAF2, or FLAG-TRAF2ΔRING alone, or, in parallel, with a vector encoding green fluorescent protein (pAd-TRAK-GFP). Transfection efficiency was routinely 40%, as determined by counting green fluorescent protein-expressing cells, and assays were performed under conditions of even-transfection efficiency. To measure ROS, a 5 mM stock of 2,7-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA) was deacetylated (generating DCFH) upon incubation in the dark at room temperature with 2.5 mM NaOH. Assays were performed in fluorescent black 96-well plates. To 50-μl cell culture supernatants were added 40 μl of phosphate-buffered saline and 10 μl of 1.5-mg/ml horseradish peroxidase (to convert ROS to H2O2). The reaction was started with the addition of 50 μl of DCFH stock (30 μM in PBS). After incubation in the dark for 30 min at room temperature, ROS were measured by fluorometry with a Packard Fluorocount, as the resulting H2O2-mediated oxidation of DCFH to DCF (excitation, 485 nm; emission, 530 nm). H2O2 concentrations were determined against a standard curve. Backgrounds were measured in parallel by removal of H2O2 with catalase (5 μl of 76,000-U/ml solution added to each reaction mixture). These values were subtracted from the sample ROS measurements. Assays were performed in triplicate. Data were analyzed by the Student t test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Activation of ASK1 by TRAF2.

Gene disruption studies indicate that TRAF2 is required for activation of the SAPKs in response to TNF (1, 16, 41). In addition, TRAF2 may relay signals from other TNFR family members, including CD27 and CD40, to the SAPKs (1). TRAF family proteins consist of carboxyl-terminal TRAF domains, central zinc finger loops, and, with the exception of TRAF1, amino-terminal RING finger domains. Truncation and mutagenesis studies indicate that the TRAF domains mediate interactions between TRAF proteins and their upstream regulators and downstream effectors. By contrast, the RING domains appear necessary for TRAF effector activation (1, 2, 23, 29, 34, 42).

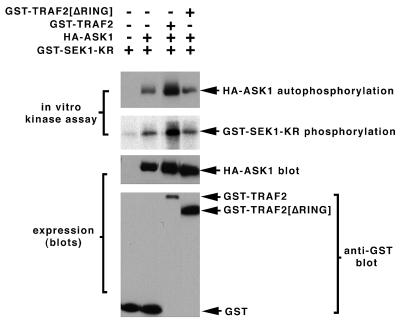

Consistent with the hypothesis that ASK1 is a TRAF2 target, we observe that coexpression of TRAF2 and ASK1 activates ASK1 (3.5-fold). Both the autophosphorylating activity of ASK1 and its phosphotransferase activity toward the substrate GST-SEK1-K129R are comparably enhanced upon coexpression with TRAF2 (Fig. 1). Deletion of the RING effector domain from TRAF2 abrogates its ability to recruit the SAPKs (19, 26). In parallel, we observe that deletion of the RING domain renders TRAF2 incapable of activating coexpressed ASK1 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Activation of ASK1 upon coexpression with TRAF2: requirement for the TRAF2 RING finger domain. 293 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA-HA-ASK1 (0.1 μg/dish) and either GST (pEBG vector), pEBG (GST)-TRAF2, or TRAF2-ΔRING (5 μg/dish) as indicated. ASK1 was immunoprecipitated and assayed in vitro for autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of the ASK1 substrate GST-SEK1[K129R]. Crude cell extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-HA to determine expression. Expression of the TRAF2 constructs was judged by isolating GST constructs on GSH agarose and subjecting the isolates to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-GST.

Interaction of ASK1 and TRAF2 in vivo: involvement of the ASK1 amino and carboxyl termini and the TRAF2 TRAF domains.

TRAF proteins are thought to transduce signals in part by directly binding their effectors (1). Thus, in the SAPK pathway, TRAF2 binds and activates kinases of the GCK family which, like ASK1, lie upstream of the SAPKs (15, 35, 42). This interaction requires the TRAF2 TRAF domains, while activation of GCKs requires the RING domains (15, 34, 35). TRAF2 can also interact with and activate MEKK1—reactions that also require the TRAF2 RING domain (2). Insofar as GCKs can also interact with MEKK1 (42), the relative contributions of TRAFs and GCKs to the regulation of MEKK1 are unclear.

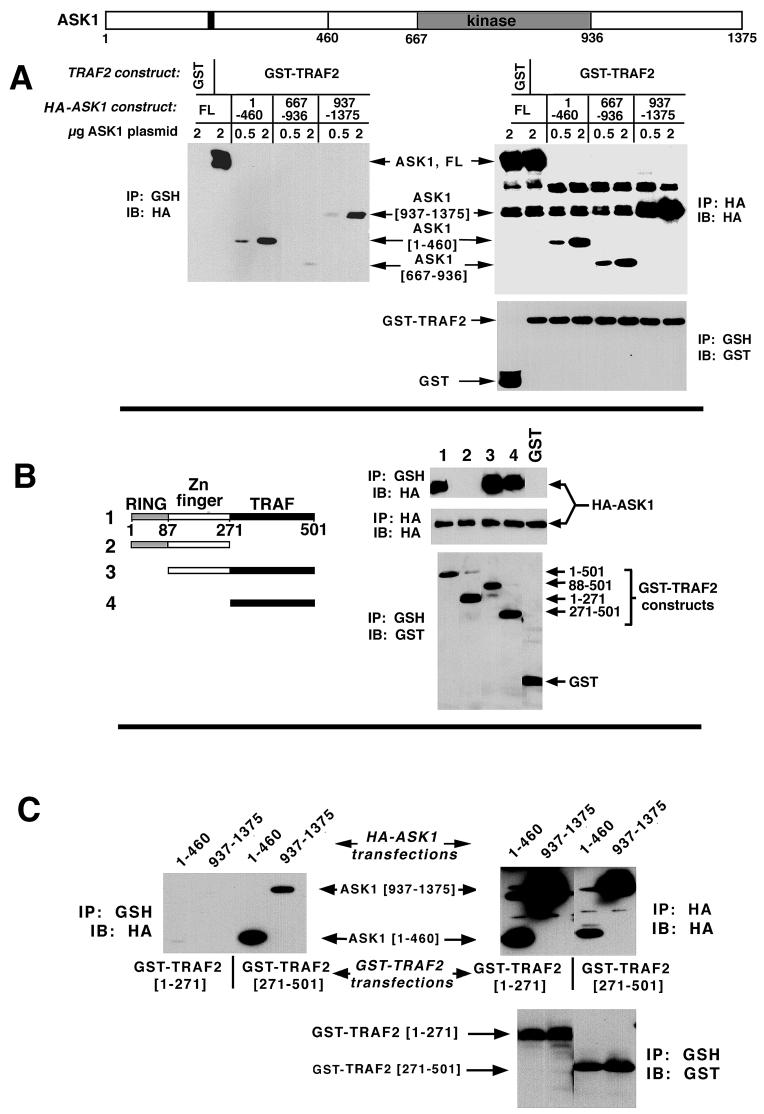

We next asked if ASK1 and TRAF2 could interact in vivo. Accordingly, HA-ASK1 was coexpressed with GST-TRAF2. GST-TRAF2 was isolated on glutathione (GSH) agarose and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting. In vivo association was determined by probing GST-TRAF2 isolates on Western blots with anti-HA to detect HA-ASK1 that associated with and copurified with the GST-TRAF2. From Fig. 2A, it is clear that, like GCK, GCKR, and MEKK1 (2, 15, 35, 42), ASK1 can physically associate in vivo with coexpressed TRAF2. In a parallel experiment, expression of progressively deleted ASK1 constructs with TRAF2 revealed that TRAF2 could interact with both the ASK1 amino-terminal (aa 1 to 460) and carboxyl-terminal (aa 937 to 1375) noncatalytic regions. The ASK1 kinase domain (aa 667 to 936) did not interact with TRAF2. This result is in apparent contrast with the findings of Nishitoh et al., who reported that TRAF2 interacted solely with the ASK1 carboxyl-terminal noncatalytic domain (28). Notably, Nishitoh et al. did not observe an interaction between TRAF2 and ASK1 aa 1 to 937 (28). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear; however, for reasons described below (Fig. 3), we believe that the interaction between ASK1[1-460] and TRAF2 is physiologically relevant.

FIG. 2.

In vivo interaction between ASK1 and TRAF2. (A) The binding of ASK1 and TRAF2 involves the amino-terminal (aa 1 to 460) and carboxyl-terminal (aa 937 to 1375) noncatalytic domains of ASK1. 293 cells were transfected with GST (pEBG vector) or pEBG (GST)-TRAF2 plus pcDNA-HA-ASK1, pMT3-HA-ASK1[1-460], pMT3-HA-ASK1[667-936], or pMT3-HA-ASK1[937-1375], as indicated. Cells were transfected with 5 μg of TRAF2 construct. The levels of ASK1 plasmid used are indicated. TRAF2 was isolated on GSH agarose and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-HA to detect associated HA-ASK1 constructs. Alternatively, GSH isolates were probed with anti-GST to gauge expression of TRAF2. Likewise, anti-HA immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-HA to determine expression of the HA-ASK1 constructs (ASK1[937-1375] consistently comigrates with a species that nonspecifically reacts with anti-HA). IP, immunoprecipitate; IB, immunoblot. (B) The TRAF2 TRAF domains are necessary and sufficient to mediate the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction. Assays were performed as above except that the indicated GST-TRAF2 truncation constructs (in pEBG) were employed. (C) The free TRAF domain of TRAF2 can interact in vivo with either ASK1[1-460] or ASK1[937-1375]. Coimmunoprecipitations were performed as above except that the indicated HA-ASK1 and GST-TRAF2 constructs were employed. IP, immunoprecipitate; IB, immunoblot.

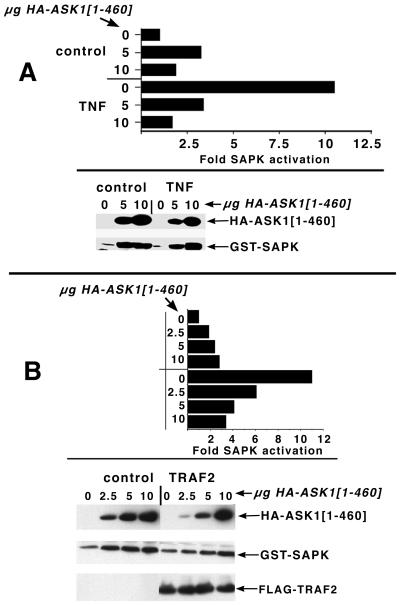

FIG. 3.

Dose-dependent inhibition of TNF and TRAF2 activation of SAPK upon expression of ASK1[1-460]. (A) Inhibition of TNF recruitment of the SAPKs by ASK1[1-460]. 293 cells were transfected with GST-SAPK (p54α1 isoform, 1 μg/plate) along with the indicated levels of HA-ASK1[1-460]. Plasmid levels were balanced with empty HA vector (pMT3). Cells were then treated with vehicle or 100 ng of TNF per ml for 5 min, as indicated. SAPK was isolated on GSH beads and assayed for phosphorylation of c-Jun as described (top). Anti-HA immunoprecipitates or GSH agarose pulldowns were probed, respectively, with anti-HA or GST to determine expression of the transfected constructs (bottom). (B) Inhibition of TRAF2 activation of the SAPKs by ASK1[1-460]. Experiments were performed as above except that half of the cells were transfected with FLAG-TRAF2 (3 μg/dish), and the cells were left untreated.

We next wished to identify the domains on TRAF2 with which ASK1 associated in vivo. Full-length HA-ASK1 and a series of GST-tagged TRAF2 deletion constructs (Fig. 2B) were coexpressed in 293 cells. The GST-TRAF2 constructs were isolated and analyzed for associated HA-ASK1, as shown in Fig. 2A. Expression of variously deleted TRAF2 constructs with ASK1 indicated that ASK1 bound to the TRAF domains of TRAF2 (Fig. 2B) and that the free TRAF domains of TRAF2, but not the RING or zinc fingers of TRAF2, could interact in vivo with the free amino-terminal (aa 1 to 460) or carboxyl-terminal (aa 937 to 1375) domains of ASK1 (Fig. 2C). Thus, although, as is shown in Fig. 1, the RING domain of TRAF2 is necessary for activation of ASK1, any interaction between the TRAF2 RING domain and ASK1 is too unstable to detect under the conditions employed in the experiments shown in Fig. 2. This finding is consistent with the results of Nishitoh et al. (28) and is similar to the observed interactions between TRAF2 and both GCK and GCKR (15, 34, 35, 42). Thus, GCK and GCKR bind the TRAF domains of TRAF2 while the RING domain of TRAF2 is necessary for activation of GCKR (15, 34, 35, 42). However, these results contrast with the findings of Hoeflich et al. (7), who noted that deletion of either the RING or TRAF domains of TRAF2 seriously compromises ASK1 binding, suggesting that the RING domain can bind ASK1. It is noteworthy that the TRAF2 RING deletion construct employed by Hoeflich et al. (Δ98-501) deletes both the RING domain (aa 26 to 87) and a small segment just upstream of the Zn finger region (1, 7). This deletion may destabilize the TRAF2 construct and reduce binding to the TRAF domain. This possibility is unlikely, however. Our results (Fig. 2B) and those of Nishitoh et al. (28) indicate that deletion of the RING and Zn finger domains is without effect while Hoeflich et al. (7) observed that this deletion abolishes ASK1 binding. These differences cannot be attributed to cell types inasmuch as we, Hoeflich et al. (7), and Nishitoh et al. (28) employed 293 cells for studies of the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction. Nor can the results be attributed to plasmid differences, given that Hoeflich et al. and Nishitoh et al. employed similar ASK1 and TRAF2 constructs (7, 28), whereas we arrived at results similar to those of Nishitoh et al. (28) employing different TRAF2 constructs. Dose-response transfections yield similar results, suggesting that transfection efficiency also cannot account for these discrepancies in mapping the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction (H. Liu, unpublished observation). Still, in spite of these differences, it is clear that the TRAF domains of TRAF2 are important for ASK1 binding. By contrast, the interaction between TRAF2 and MEKK1, as well as TRAF2 activation of MEKK1, require only the TRAF2 RING effector region (2). These observations support the contention that TRAF proteins can bind their effectors through either the TRAF or RING domains, while effector activation is mediated by the TRAF2 RING domain.

Inhibition of TNF and TRAF2 activation of SAPK by ASK1[1-460].

Figure 2A and C indicate that TRAF2 can interact with both aa 1 to 460 and 937 to 1375 of ASK1. If the interaction between ASK1[1-460] and TRAF2 were trivial, one would not expect expression of ASK1[1-460] to interfere with TRAF2 signaling to the SAPKs. In order to assess the physiologic significance of these interactions, we tested whether the TRAF2 binding domains of ASK1 could block either TNF or TRAF2 activation of coexpressed SAPK. Expression of ASK1[1-460] with SAPK inhibits the ability of both TNF (Fig. 3A) and coexpressed TRAF2 (Fig. 3B) to activate SAPKs, suggesting that in addition to aa 937 to 1375, aa 1 to 460 of ASK1 represent a physiologically significant binding site for TRAF2. By contrast, we did not reliably observe inhibition of TRAF2 activation of SAPK by ASK1[937-1375] (H. Liu, unpublished observations). However, inasmuch as ASK1[937-1375] binds TRAF2 strongly (Fig. 2A and C and reference 28), a role for this domain in the regulation of ASK1 by TRAF2-TNF must not be ruled out, and the function of these two TRAF2 binding sites with regard to the regulation of ASK1 remains to be determined.

The TNF-dependent interaction of endogenous ASK1 and TRAF2 is redox sensitive.

From the preceding results, it is plausible to conclude that ASK1 is a TRAF2 effector that recruits the SAPKs and p38s. However, the mechanism of ASK1 activation by TRAF2 is still unclear. TNF and TRAF2 activation of the SAPKs are thought to involve at least, in part, the generation of ROS (5, 6, 26, 32). Thus, TNF stimulates the production of ROS, and both TNF and TRAF2 activation of SAPK can be partially inhibited (∼30 to 40%) upon depletion of ROS with free radical scavengers (5, 6, 26, 32). Moreover, ASK1 itself can be recruited by oxidant stress—a process that apparently fosters dimerization-dependent ASK1 activation (possibly through interchain disulfide formation) (6, 32).

Although TNF is known to stimulate the production of ROS and TRAF2 activation of the SAPKs can be partially reversed with free radical scavengers (5, 6, 26, 32), TRAF2-mediated production of ROS has not been demonstrated. Accordingly, we transfected 293 cells with either vector, TRAF2, or TRAF2ΔRING. Production of ROS was determined as described in Materials and Methods, and assays were performed only under conditions of even-transfection efficiency for all plasmids. From the data in Table 1, it is clear that expression of TRAF2 results in a significant stimulation of ROS production compared to that of vector controls. This ROS production appears dependent upon the TRAF2 RING domain inasmuch as expression of TRAF2ΔRING fails to stimulate a significant increase in ROS production. Thus, as with SAPK (5, 6, 26, 32) and ASK1 activation (Fig. 1), ROS production incurred by TRAF2 requires the TRAF2 RING domain.

TABLE 1.

ROS production in 293 cells in response to TRAF2 expressiona

| Transfector | ROS production (μM H2O2 [mean ± SD]) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Vector | 2.93 ± 0.41 | NA |

| TRAF2 | 4.91 ± 0.45 | 0.016 |

| TRAF2ΔRING | 4.06 ± 0.41 | 0.057 |

NA, not applicable. Data were analyzed by Student's t test comparing the transfected cells to control cells; a P value of <0.05 is considered significant. ROS assays were performed on independent triplicate transfections under conditions of even-transfection efficiency as described in Materials and Methods. Assays were performed 24 h after transfection. A standard curve employing different H2O2 concentrations subjected in parallel to the DCF oxidation assay was used to calculate concentrations of H2O2 produced in the transfected cells.

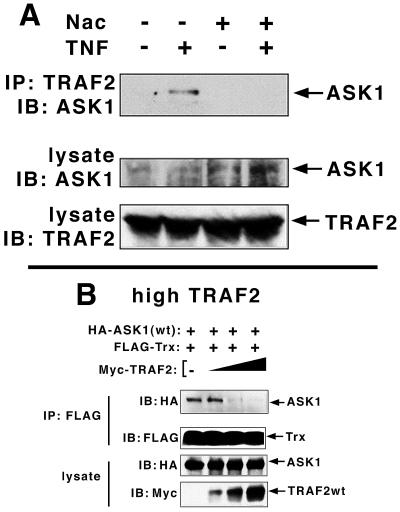

With these observations, plus the known ROS dependence of ASK1 activation in mind, we wished to determine the role of ROS in fostering the TNF-dependent association of endogenous TRAF2 and ASK1. In vivo association was characterized as the TNF-dependent coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous ASK1 and TRAF2. Consistent with a role for ROS in the regulation of the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction, we observed that the TNF-dependent in vivo association of endogenous ASK1 and TRAF2 could be completely reversed upon administration of the free radical scavenger Nac (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

TNF stimulation of the association of endogenous ASK1 and TRAF2 is ROS-dependent: reversal with Nac. Overexpression of TRAF2 against a background of low Trx blocks the ASK1-Trx interaction. (A) The TNF-dependent association of endogenous ASK1 and TRAF2 is reversed by free radical scavengers. L929 cells were treated with TNF and Nac as indicated. Endogenous TRAF2 was immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted with anti-ASK1 to detect endogenous ASK1 associated with TRAF2. Crude lysates were blotted with anti-ASK1 and TRAF2, as indicated, in order to monitor the levels of the endogenous proteins present in each assay sample. (B) Excess TRAF2 reverses the ASK1-Trx interaction. 293 cells were transfected with the indicated HA-ASK1 (0.3 μg), FLAG-Trx (1 μg) constructs (in pcDNA3), and either vector or increasing levels of Myc-TRAF2 (0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 μg of pcDNA3). FLAG-Trx was immunoprecipitated and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-FLAG. IP, immunoprecipitate; IB, immunoblot.

If the formation of an ASK1-TRAF2 complex requires the prior generation of ROS, why are ASK1-TRAF2 complexes detectable when these proteins are overexpressed? First, overexpression is sufficient to activate TRAF2 and, by extension, its effectors (2, 19, 22, 26, 28, 34, 35). Inasmuch as activation of SAPK by coexpressed TRAF2 can be reversed with free radical scavengers (28), it is likely that TNF-dependent ROS production is at least in part TRAF2 dependent, and the data in Table 1 support this idea. Thus, overexpression of TRAF2 may create conditions conducive for detection of an ASK1-TRAF2 complex. Alternatively, it is equally possible that overexpression of ASK1 is sufficient to titer out any endogenous inhibitors of the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction, with the consequence that a significant pool of free ASK1 might be present and available to bind TRAF2 under conditions of overexpression.

Saitoh et al. observed that the redox-sensing enzyme thioredoxin (Trx) is an endogenous inhibitor of ASK1 that may block ASK1 activation by TNF (32). Trx is a 12-kDa protein thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase which, in mammalian cells, has a variety of biological functions related to cell proliferation and apoptosis (9, 10). An evolutionarily conserved Trp-Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys-Lys catalytic core provides the sulfhydryls involved in Trx-dependent reducing activity, and Trx oxidation results in the formation of a disulfide bridge within this core (9, 10). Trx is a potent antioxidant that protects against peroxide (H2O2)-, TNF-, and cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity, in which ROS are thought to participate. As adult T-cell leukemia-derived factor, secreted Trx also protects leukemic cells from oxidant stress-induced apoptosis. These protective functions correlate with Trx oxidation, suggesting that Trx is an ROS target (9, 10). Overexpressed TRAF2 may generate sufficient levels of ROS (Table 1 and references 5 and 26) to displace from ASK1 endogenous Trx or Trx expressed at comparatively low levels. Consistent with this idea, we observe that coexpression of increasing levels of TRAF2 with ASK1 reverses the ASK1-Trx interaction (Fig. 4B). It is noteworthy, however, that substantial levels of TRAF2 expression are required before this reversal is observed (Fig. 4B).

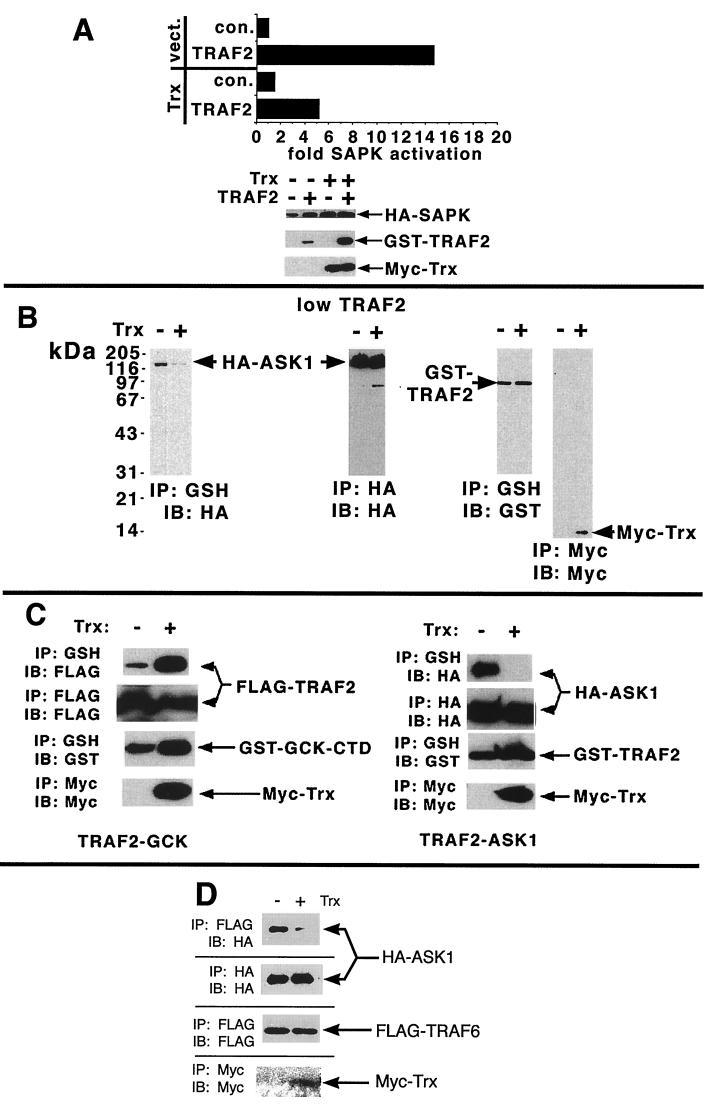

Excess Trx inhibits TRAF2 activation of SAPK and blocks the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction: reversal by ROS.

Although excess TRAF2 can disrupt the ASK1-Trx interaction (Fig. 4B), a finding that, when combined with the possibility that overexpressed ASK1 titers out endogenous Trx, provides some explanation as to how overexpressed TRAF2 might spontaneously associate in vivo with ASK1, it must be remembered that endogenous TRAF2 and ASK1 are low-abundance signaling polypeptides present in lesser quantities than endogenous Trx (1, 9, 10, 11, 31). Thus, overexpression of TRAF2 against a background of endogenous Trx or with comparatively lower levels of recombinant Trx may not accurately mimic in vivo conditions. Given that TRAF2 recruitment of the SAPKs involves the generation of ROS and that TRAF2 activates ASK1 by a process that may involve, in part, in vivo binding (Fig. 1 and 2 and references 6, 26, and 28), there are two possible mechanisms by which Trx and TRAF2 could combine in vivo to regulate ASK1. First, activated TRAF2, at the TNFR1 complex, could bind a heteromer of ASK1 and Trx, with Trx dissociation and ASK1 activation following as a consequence of subsequent TRAF2-mediated ROS production (Table 1). The results in Fig. 4A argue against this possibility inasmuch as the TNF-dependent in vivo association of endogenous ASK1 and TRAF2 is reversed by Nac, suggesting that ROS generation and the consequent dissociation of ASK1 from Trx are necessary prerequisites for the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction. Alternatively, Trx could prevent the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction through a process reversed by ROS generated in parallel through TRAF2 in response to TNF.

In order to begin to determine the effect of Trx on the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction under conditions that more closely reflect the relative abundance of Trx and TRAF2, we coexpressed SAPK plus low levels (1 μg/plate) of TRAF2 plasmid either with or without excess (5 μg/plate) ectopically expressed Trx plasmid. From Fig. 5A, it is clear that under these conditions, expression of Trx substantially (but not completely) inhibits (∼60 to 75%) TRAF2 activation of the SAPKs. In parallel, TRAF2 isolates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting to detect associated ASK1. Coexpression of ASK1 and low amounts of TRAF2 with a relative excess of Trx almost completely inhibits the interaction between ASK1 and TRAF2 (Fig. 5B). These findings suggest that when Trx is present in excess, as occurs in vivo, it sequesters ASK1 from TRAF2, pending a stimulus that fosters Trx dissociation.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction by Trx under conditions of a relative excess of Trx: reversal with oxidant (hydrogen peroxide [H2O2]. (A) Under conditions of comparatively low TRAF2 expression, Trx inhibits TRAF2 activation of SAPK. 293 cells were transfected with pMT3 (HA)-SAPK-p46β1 (1 μg/dish) and either vector pEBG-(GST)-TRAF2 (1 μg/dish) or pCMV-Myc-Trx (5 μg/dish), as indicated. SAPK was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts and assayed in immune complexes as indicated. TRAF2 was isolated on GSH beads and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-HA to detect bound ASK1. (B) Under conditions of lower TRAF2 expression, Trx inhibits the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction. 293 cells were transfected as indicated with pcDNA3-HA-ASK1 (1 μg/dish), pEBG-(GST)-TRAF2 (1 μg/dish), and pCMV5-Myc-Trx (5 μg/dish). GSH agarose isolates of TRAF2 were probed with anti-HA to detect bound ASK1. GSH isolates of TRAF2, as well as the Myc and HA immunoprecipitates, were also probed with the cognate antibody to monitor expression of the transfected constructs. (C) Expression of Trx does not inhibit the interaction between TRAF2 and GCK under conditions wherein the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction is disrupted. 293 cells were transfected with GST-TRAF2 and HA-ASK1 or the TRAF2 binding domain of GCK (GST-GCK-CTD) (42) and FLAG-TRAF2 plus either vector or Myc-Trx. GST polypeptides were isolated on GSH agarose and probed with anti-FLAG (GCK-TRAF2 interaction) or anti-HA (TRAF2-ASK1 interaction). For all panels, expression of the transfected constructs was determined by subjecting GSH agarose, anti-HA, anti-FLAG, or anti-Myc isolates to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the cognate antibody. (D) TRAF6 association with ASK1 is also reversed by excess Trx. 293 cells were transfected with FLAG-TRAF6, HA-ASK1, and Myc-Trx. TRAF6 was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG and probed with anti-HA to detect bound ASK1. HA and FLAG immunoprecipitates were also immunoblotted with the corresponding antibodies in order to judge expression of the relevant constructs. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot.

Although Trx almost completely blocks the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction, it should be noted that Trx inhibition of TRAF2 activation of SAPK is incomplete. Thus, other systems that couple TRAF2 to the SAPKs may not be ROS sensitive. The interaction of either GCK or GCKR with TRAF2 is a parallel mechanism by which TRAF2 recruits the SAPKs (15, 35, 42). Expression of Trx does not inhibit the interaction between GCK and TRAF2 under conditions wherein the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction is completely blocked (Fig. 5C). Indeed, the binding of TRAF2 to the carboxyl-terminal TRAF binding region of GCK (42) is enhanced upon expression of Trx (Fig. 5C), perhaps as a result of Trx-mediated dissociation of ASK1 and other ROS-sensitive TRAF2 effectors. Consistent with this, we observe that Nac, which completely reverses the TNF-dependent interaction of endogenous ASK1 and TRAF2 (Fig. 4A), only partially reverses the activation of SAPK by TNF (18, 26; H. Liu, unpublished observations). Thus, the inhibitory effect of Trx on TRAF2 signaling is, at least with regard to SAPK recruitment, relatively specific.

Both Nishitoh et al. (28) and Hoeflich et al. (7) observe that TRAF6 can interact with ASK1. TRAF6 is a likely effector for interleukin-1 (IL-1) and several other inflammatory signaling mechanisms (1), and there is evidence that, at least in some instances, IL-1 stimulates the production of ROS (24). We too observe that TRAF6 interacts with ASK1. Moreover, expression of an excess level of Trx strongly reverses TRAF6 binding to ASK1 (Fig. 5D). Thus, the TRAF6-ASK1 interaction, like that between TRAF2 and ASK1, is at least in part redox dependent. This result suggests that Trx dissociation may be a general prerequisite for the binding of TRAFs to ASK1. As with TNF and TRAF2 signaling to the SAPKs, several possible mechanisms by which MAP3Ks couple to TRAF6 have been identified. Thus, the MAP3K transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase-1 is also activated by IL-1 and TRAF6, and TRAF6 associates with TAK1 in vivo (27). Moreover, we observe that TRAF6 can also interact with GCK (J. M. Kyriakis, unpublished observations). It remains to be determined if ASK1 represents a dominant mechanism by which TRAF6 recruits the SAPKs.

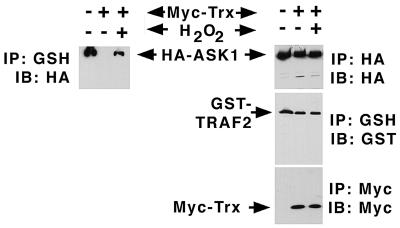

ROS generated in response to TNF through TRAF2 can promote the dissociation of ASK1 and Trx (Table 1 and reference 32), and our results (Fig. 4) indicate that the TNF-dependent association between endogenous ASK1 and TRAF2 can be reversed with free radical scavengers. Furthermore, TRAF2 activation of SAPK depends in part on the generation of ROS and is significantly blunted by free radical scavengers (26). Accordingly, we next tested if oxidation might reverse the inhibition of the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction incurred upon expression of excess Trx with low levels of TRAF2. Thus, low levels of TRAF2 and ASK1 were coexpressed with a relative excess of vector or Trx plasmid. Transfected cells were treated with vehicle or oxidant (H2O2). TRAF2 isolates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting to detect associated ASK1. From Fig. 6, it is evident that while Trx expression blocks the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction, H2O2 can partially reverse this inhibition. Any reduction in the level of ASK-Trx complexes as a consequence of H2O2 treatment is not detectable (data not shown), likely due to the fact that only a small fraction of the total pool of ASK-Trx complexes is dissociated by H2O2. The results in Fig. 5 and 6 support the idea that ROS generated in response to TNF act to promote the dissociation of Trx from ASK1, thereby enabling the binding of ASK1 and TRAF2.

FIG. 6.

Oxidant reverses Trx inhibition of the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction. 293 cells were transfected with HA-ASK1 (1 μg/dish), GST-TRAF2 (1 μg/dish), and Myc-Trx (5 μg/dish) as indicated. Cells were then treated with water or 10 mM H2O2 as indicated. GST-TRAF2 was isolated on GSH beads and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-HA to detect associated HA-ASK1.

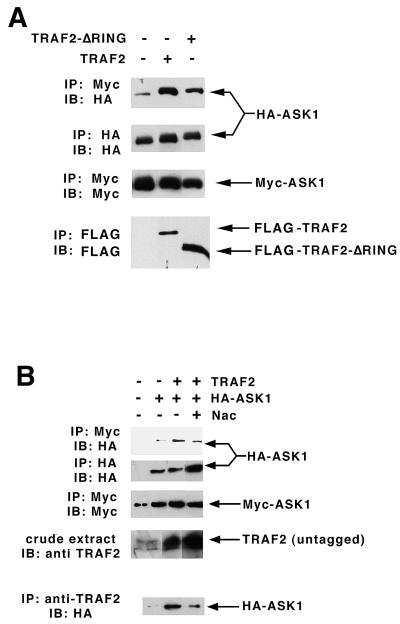

TRAF2 enhances ASK1 homo-oligomerization in a reaction dependent upon the TRAF2 RING effector domain and ROS.

A recent study from Gotoh and Cooper (6) demonstrated that ASK1 is activated in part through a mechanism involving oligomerization. Thus, coumermycin-dependent oligomerization of DNA gyrase-ASK1 fusion constructs results in activation of coexpressed SAPK, and TNF can stimulate the homo-oligomerization of transiently expressed ASK1 in vivo (6). With this observation in mind, we sought to determine if expression of TRAF2 could foster enhanced ASK1 oligomerization. Myc- and HA-tagged ASK1 were coexpressed in the presence or absence of TRAF2 or ΔRING-TRAF2. ASK1 oligomerization was detected as the presence of HA-ASK1 immunoreactivity in Myc-ASK1 immunoprecipitates. From Fig. 7A, it is evident that expression of the two ASK1 constructs results in modest spontaneous oligomerization. Coexpression with the ASK1 constructs of wild-type TRAF2 substantially enhances the level of HA-ASK1 detected in Myc-ASK1 immunoprecipitates, suggesting that TRAF2 stabilizes ASK1 oligomerization in vivo. Coexpression of the heterologous ASK1 constructs with ΔRING-TRAF2 also results in enhanced ASK1 oligomerization; however, the extent of this enhanced oligomerization is significantly less than that observed upon coexpression of ASK1 with wild-type TRAF2. Thus, as with ASK1 activation (Fig. 1), optimal TRAF2-dependent stabilization of ASK1 oligomers requires, in part, the TRAF2 RING effector domain.

FIG. 7.

TRAF2-dependent enhancement of ASK1 oligomerization. (A) TRAF2 enhancement of ASK1 oligomerization is dependent in part on the TRAF2 RING domain. 293 cells were transfected with Myc-ASK1 and HA-ASK1 plus either vector FLAG-TRAF2 or FLAG-TRAF2ΔRING. Myc-ASK1 immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-HA to detect formation of ASK1 oligomers. HA, Myc, and FLAG immunoprecipitates were probed with the cognate antibodies indicated to judge expression of the transfected constructs. (B) TRAF2-dependent oligomerization of ASK1 is dependent on ROS. 293 cells were transfected with Myc-ASK1 and HA-ASK1 plus either vector or untagged TRAF2. A portion of the TRAF2-transfected cells was treated with Nac (5 mM, 16 h) as indicated. After SDS-PAGE, Myc-ASK1 immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-HA to detect formation of ASK1 oligomers. HA and Myc immunoprecipitates were probed with the cognate antibodies to judge expression of the transfected constructs. Crude extracts were probed with anti-TRAF2 to detect expression of TRAF2. Anti-TRAF2 immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-HA to detect the formation of the ASK1-TRAF2 complex.

We also observe that TRAF2-dependent ASK1 oligomerization is dependent in part on the generation of ROS. Thus, we transfected cells with heterologously (HA or Myc) tagged ASK1 plus untagged TRAF2 or empty vector. A portion of the cells was treated with Nac. Myc-ASK1 was immunoprecipitated and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-HA to detect formation of ASK1 oligomers. Anti-TRAF2 immunoprecipitates were probed with anti-HA to detect formation of the ASK1-TRAF2 complex. Treatment of cells with Nac significantly reduces the enhanced oligomerization of ASK1 incurred upon coexpression with TRAF2 (Fig. 7B). In parallel, Nac also reduces the recovery of ASK1-TRAF2 complexes. This result is consistent with earlier findings (6) indicating that TNF-dependent ASK1 oligomerization is reversed with free radical scavengers and suggests that TNF-ROS-dependent formation of the ASK1-TRAF2 complex triggers ASK1 oligomerization.

Concluding remarks.

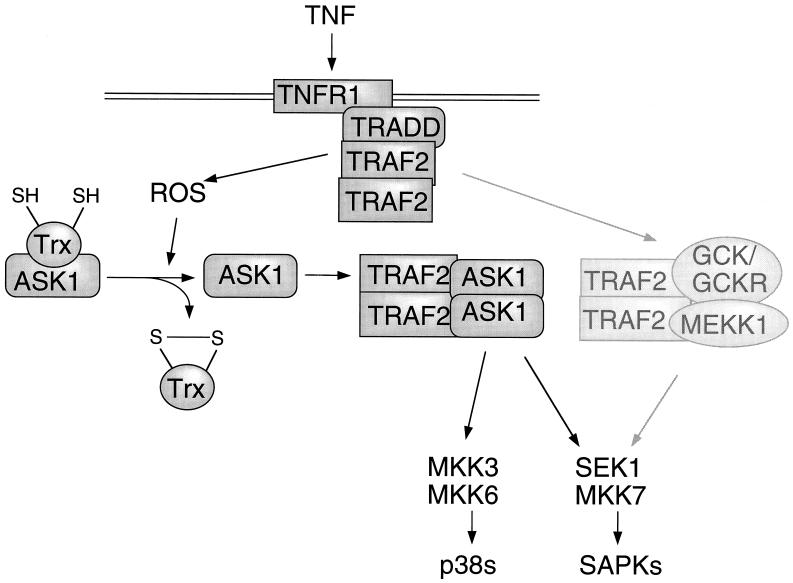

The results presented herein shed light on the mechanisms by which TNF recruits the SAPKs and p38s, thereby contributing to activation of AP-1. These findings, combined with previous results (2, 6, 7, 26, 28, 34, 35, 42), suggest a model for the regulation of the SAPKs by TNFR1 (Fig. 8). In this model, there are two parallel mechanisms of SAPK activation. Thus, GCK, GCKR, and MEKK1 interact in vivo with TRAF2, and GCK/GCKR and TRAF2 may cooperate to activate MEKK1 (2, 15, 34, 35, 42). The second mechanism of SAPK activation by TNF involves ASK1 and the TRAF2-dependent generation of ROS. Our findings suggest that the TRAF2 → ASK1 pathway requires, as a prerequisite, the oxidant-mediated dissociation of Trx from ASK1. By contrast, the TRAF2 → GCK/GCKR mechanism is not inhibited by Trx. Trx dissociation from ASK1 is followed by TRAF2 binding. This binding may trigger ASK1 oligomerization-dependent activation.

FIG. 8.

Model for the regulation of ASK1 by TNF. The parallel TRAF2 → GCK/GCKR → MEKK1 pathway is indicated for comparison. See text for details.

The functional significance of these two TRAF2-dependent mechanisms is unclear. Thus, the importance of the TRAF2 → GCK/GCKR-MEKK1 signaling axis can be inferred from the observation that expression of antisense GCKR (34) or either dominant inhibitory MEKK1, GCKR (2, 34, 35), or GCK constructs (J. M. Kyriakis, unpublished observations) can block TRAF2 activation of SAPK. However, overexpression of Trx substantially reverses TRAF2 activation of SAPK (as well as the ASK1-TRAF2 interaction) without inhibiting the TRAF2-GCK interaction. The two mechanisms of TNFR activation of SAPK may respond differentially to TNF signals of varying intensity or duration. In support of this idea, endogenous GCK and GCKR are activated comparatively rapidly by TNF (maximally within 5 to 10 min) while activation of endogenous ASK1 by TNF reaches a maximum between 20 min and 1 h (6, 7, 15, 28, 34). The TNF-dependent binding of endogenous ASK1 to endogenous TRAF2 is similarly slow, reaching a maximum at 15 to 20 min (7, 28, 32). Such differential sensitivity would be reminiscent of the osmosensing signaling pathways of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Hog1p is an S. cerevisiae osmosensing MAPK that is activated by the MEK Pbs2p. Pbs2p, in turn, is recruited by two different sets of MAP3Ks. Ssk2p and Ssk22p are MAP3Ks which lie downstream of an osmoreceptor coupled to a two-component phosphorelay mechanism. Ste11p is a MAP3K effector for Sho1p, a second osmoreceptor which contains an SH3 domain (21, 30). It is thought that these parallel pathways respond selectively to osmotic stresses of differing strength or duration (21, 30). It is also possible that the TRAF2 → GCK/GCKR-MEKK1 and TRAF2 → ASK1 pathways may be employed independently on a cell- or stimulus-specific basis. It will be important to determine how and why activation of the SAPKs by TNF involves the combined effects of two apparently redundant mechanisms.

Oligomerization is an emerging theme in MAP3K regulation and is central to the activation of the mitogen-activated MAP3K Raf-1 and the stress-activated MAP3K mixed lineage kinase-3, and may contribute to cytokine recruitment of NF-κB-inducing kinase, a MAP3K-like kinase of the NF-κB pathway (17, 18, 20). TRAF2 has been shown to homo-oligomerize in vivo (23, 29), and recent crystallographic studies indicate that the TRAF2 TRAF domain exists as a trimer when complexed with upstream receptors (23, 29). Forced oligomerization of fusion constructs consisting of the TRAF2-RING domain linked to FK506 binding protein-12 (FKBP12) occurs in response to the dimerizer drug FK1012, an analogue of FK506. This results in activation of coexpressed SAPK (2). FK1012 treatment also results in the formation of insoluble FKBP-TRAF2 aggregates that can be recovered by centrifugation. MEKK1, when coexpressed with FKBP12-TRAF2, will partition with the insoluble FKBP12-TRAF2 aggregates in an FK1012-dependent manner, suggesting that MEKK1 associates selectively with oligomerized TRAF2 (2). With this finding in mind, it is plausible to speculate that the association of MEKK1 with TRAF2 oligomers results in oligomerization-dependent MEKK1 activation. Similarly, ASK1 oligomerizes in vivo in response to TNF and oxidant stress. Moreover, coumermycin-dependent forced oligomerization of DNA gyrase-ASK1 fusions results in activation of coexpressed SAPK, suggesting that ASK1 is activated in part by oligomerization (6). We observe that TRAF2 enhances the oligomerization of coexpressed ASK1. This result is consistent with the idea that TRAF2 oligomers at cytokine receptor complexes trigger the oligomerization-dependent activation of associated ASK1. The TRAF domains of TRAF2 bind ASK1; however, the RING motif is necessary for ASK1 activation. While ΔRING-TRAF2 can also modestly enhance the oligomerization of coexpressed ASK1, optimal enhancement of ASK1 oligomerization requires the RING domain. Thus, in vivo, the binding of ASK1 to the TRAF domains of TRAF2 may not yield ASK1 oligomers competent for activation, and a functionally significant oligomerization of ASK1 may require the participation of the RING domain. Inasmuch as the TRAF2 RING domain is also necessary for ROS production and given that ASK1 oligomerization can also be triggered by ROS, functional TRAF2-dependent ASK1 oligomerization may require the TRAF2-induced generation of ROS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. Mochida for important assistance, T. Yuasa for TRAF2 constructs, H. Nakano for TRAF6, N. Cindhuchao of the M.G.H. Laboratory for Oxidation Biology for help with ROS measurements, and G. Tzivion for useful suggestions.

Support for these studies was provided by NIH grant R01-GM46577 and a Biomedical Science Grant from the Arthritis Foundation (to J.M.K.) and by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (to H.I.).

Footnotes

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Eleanor Troccoli.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arch R H, Gedrich R W, Thompson C B. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs)—a family of adapter proteins that regulates life and death. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2821–2830. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baud V, Liu Z-G, Bennett B, Suzuki N, Xia Y, Karin M. Signaling by proinflammatory cytokines: oligomerization of TRAF2 and TRAF6 is sufficient for JNK and IKK activation and target gene induction via an amino terminal effector domain. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1297–1308. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner D A, O'Hara M, Angel P, Chojkier M, Karin M. Prolonged activation of c-jun and collagenase genes by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1989;337:661–663. doi: 10.1038/337661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang H Y, Nishitoh H, Yang X, Ichijo H, Baltimore D. Activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) by the adapter protein Daxx. Science. 1998;281:1860–1863. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goossens V, Grooten J, De Vos K, Fiers W. Direct evidence for tumor necrosis factor-induced mitochondrial reactive oxygen intermediates and their involvement in cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8115–8119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gotoh Y, Cooper J A. Reactive oxygen species- and dimerization-induced activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in tumor necrosis factor-α signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17477–17482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoeflich K P, Yeh W-C, Yao Z, Mak T W, Woodgett J R. Mediation of TNF receptor-associated factor effector functions by apoptosis signal-regulating kinase-1 (ASK1) Oncogene. 1999;18:5814–5820. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland P M, Suzanne M, Campbell J S, Noselli S, Cooper J A. MKK7 is a stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase functionally related to hemopterous. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24994–24998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmgren A. Thioredoxin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1985;54:237–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmgren A. Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13963–13966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, ten Dijke P, Saitoh M, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K, Gotoh Y. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science. 1997;275:90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ip Y T, Davis R J. Signal transduction by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-from inflammation to development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karin M, Liu Z-G, Zandi E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:240–246. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyriakis J M, Avruch J. Sounding the alarm: protein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24313–24316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kyriakis J M. Signaling by the germinal center kinase family of protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5259–5262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S Y, Reichlin A, Santana A, Sokol K A, Nussenzweig M C, Choi Y. TRAF2 is essential for JNK but not NF-κB activation and regulates lymphocyte proliferation and survival. Immunity. 1997;7:703–713. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung I W-L, Lassam N. Dimerization via tandem leucine zippers is essential for the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase, MLK-3. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32408–32415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin X, Mu Y, Cunningham E T, Jr, Marcu K B, Geleziunas R, Greene W C. Molecular determinants of NF-κB-inducing kinase action. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5899–5907. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z-G, Hsu H, Goeddel D V, Karin M. Dissection of TNF receptor-1 effector functions: JNK activation is not linked to apoptosis while NF-κB activation prevents cell death. Cell. 1996;87:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Z, Tzivion G, Belshaw P J, Vavvas D, Marshall M, Avruch J. Oligomerization activates c-Raf-1 through a Ras-dependent mechanism. Nature. 1996;383:181–184. doi: 10.1038/383181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maeda T, Takekawa M, Saito H. Activation of yeast PBS2 MAPKK by MAPKKKs or by binding of an SH3-containing osmosensor. Science. 1995;269:554–558. doi: 10.1126/science.7624781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malinin N L, Boldin M P, Kovalenko A V, Wallach D. MAP3K-related kinase involved in NF-κB induction by TNF, CD-95 and IL-1. Nature. 1997;385:540–544. doi: 10.1038/385540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McWhirter S M, Pullen S S, Holton J M, Crute J J, Kehry M R, Alber T. Crystallographic analysis of CD40 recognition and signaling by human TRAF2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8408–8413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier B, Radeke H H, Selle S, Younes M, Seis H, Resch K, Habermehl G G. Human fibroblasts release reactive oxygen species in response to interleukin-1 or tumour necrosis factor-α. Biochem J. 1989;263:539–545. doi: 10.1042/bj2630539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michaelson, Bader D, Kuo F, Kozak C, Leder P. Loss of Daxx, a promiscuously interacting protein results in extensive apoptosis in early mouse development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1918–1923. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natoli G, Costanzo A, Ianni A, Templeton D J, Woodgett J R, Balsano C, Levrero M. Activation of SAPK/JNK by TNF receptor-1 through a noncytotoxic TRAF2-dependent pathway. Science. 1997;275:200–203. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishioto K, Hiyama A, Inoue J-I, Cao Z, Matsumoto K. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIK-IκB as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature. 1999;398:252–256. doi: 10.1038/18465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishitoh H, Saitoh M, Mochida Y, Takeda K, Nakano H, Rothe M, Miyazono K, Ichijo H. ASK1 is essential for JNK/SAPK activation by TRAF2. Mol Cell. 1998;2:389–395. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park Y C, Burkitt V, Villa A R, Tong L, Wu H. Structural basis for self-association and receptor recognition of human TRAF2. Nature. 1999;398:533–538. doi: 10.1038/19110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Posas F, Saito H. Osmotic activation of the HOG MAPK pathway via Ste11p MAPKKK: Scaffold role of Pbs2p MAPKK. Science. 1997;276:1702–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothe M, Wong S C, Henzel W J, Goeddel D V. A novel family of putative signal transducers associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the 75-kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell. 1994;78:681–692. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saitoh M, Nishitoh H, Fujii M, Takeda K, Tobiume K, Sawada Y, Kawabata M, Miyazono K, Ichijo H. Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J. 1998;17:2596–2606. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi C-S, Kehrl J H. Activation of stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase, but not NF-κB, by the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor 1 through a TNF receptor-associated factor 2- and germinal center kinase related-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32102–32107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi C-S, Leonardi A, Kyriakis J, Siebenlist U, Kehrl J H. TNF-mediated activation of the stress-activated protein kinase pathway: TNF receptor-associated factor 2 recruits and activates germinal center kinase related. J Immunol. 1999;163:3279–3285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torii S, Egan D A, Evans R A, Reed J C. Human Daxx regulates Fas-induced apoptosis from nuclear PML oncogenic domains (PODs) EMBO J. 1999;18:6037–6049. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tournier C, Whitmarsh A J, Cavanagh J, Barrett T, Davis R J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 is an activator of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7337–7342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tracey K J, Cerami A. Tumor necrosis factor, other cytokines and disease. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:317–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Beyaert R, Fiers W. Two tumour necrosis factor receptors: structure and function. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:392–399. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang X, Khosravi-Far R, Chang H Y, Baltimore D. Daxx, a novel Fas-binding protein that activates JNK and apoptosis. Cell. 1997;89:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80294-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeh W-C, Shahinian A, Speiser D, Kraunus J, Billia F, Wakeham A, de la Pompa J L, Ferrick D, Hum B, Iscove N, Ohashi P, Rothe M, Goeddel D V, Mak T W. Early lethality, functional NF-κB activation, and increased sensitivity to TNF-induced cell death in TRAF2-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;7:715–725. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuasa T, Ohno S, Kehrl J H, Kyriakis J M. Tumor necrosis factor signaling to stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK)/Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22681–22692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]