Abstract

Background

Posttraumatic stress (PTS) and anxiety are common mental health problems among parents of babies admitted to a neonatal unit (NNU). This review aimed to identify sociodemographic, pregnancy and birth, and psychological factors associated with PTS and anxiety in this population.

Method

Studies published up to December 2022 were retrieved by searching Medline, Embase, PsychoINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health electronic databases. The modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cohort and cross-sectional studies was used to assess the methodological quality of included studies. This review was pre-registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021270526).

Results

Forty-nine studies involving 8,447 parents were included; 18 studies examined factors for PTS, 24 for anxiety and 7 for both. Only one study of anxiety factors was deemed to be of good quality. Studies generally included a small sample size and were methodologically heterogeneous. Pooling of data was not feasible. Previous history of mental health problems (four studies) and parental perception of more severe infant illness (five studies) were associated with increased risk of PTS, and had the strongest evidence. Shorter gestational age (≤ 33 weeks) was associated with an increased risk of anxiety (three studies) and very low birth weight (< 1000g) was associated with an increased risk of both PTS and anxiety (one study). Stress related to the NNU environment was associated with both PTS (one study) and anxiety (two studies), and limited data suggested that early engagement in infant’s care (one study), efficient parent-staff communication (one study), adequate social support (two studies) and positive coping mechanisms (one study) may be protective factors for both PTS and anxiety. Perinatal anxiety, depression and PTS were all highly comorbid conditions (as with the general population) and the existence of one mental health condition was a risk factor for others.

Conclusion

Heterogeneity limits the interpretation of findings. Until clearer evidence is available on which parents are most at risk, good communication with parents and universal screening of PTS and anxiety for all parents whose babies are admitted to NNU is needed to identify those parents who may benefit most from mental health interventions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12884-024-06383-5.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress symptoms, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Anxiety, Neonatal units, Preterm birth, Factors, Systematic review

Background

Having a baby admitted to a neonatal unit (NNU) can be highly distressing for parents [1, 2] and many experience mental health problems during and beyond their baby’s admission [3–5]. Evidence from a recent systematic review [5] estimated prevalence of anxiety among parents of babies admitted to NNU was as high as 42% during the first month after birth and remained high at 26% from one month to one year after birth. The prevalence of symptoms of posttraumatic stress (PTS) was equally high at 40% during the first month after birth, 25% from one month to one year and remained high at 27% more than one year after birth.

Unaddressed perinatal mental health problems can have long-term implications for parents, babies and families [6]. Identifying parents who are at risk of developing mental health problems during this vulnerable time is therefore vital so that timely support and interventions can be delivered [7]. However, it is unclear why some parents are more susceptible to develop mental health problems and others are more resilient. In the UK, women are asked about their emotional wellbeing routinely at each antenatal and postnatal contact with healthcare professionals [8]. For women in the general perinatal population, a number of factors are associated with perinatal anxiety. Obstetric factors include current or previous pregnancy complications, surgical obstetric interventions, and miscarriages; health and social factors include a history of mental health problems, domestic violence, being a single parent, having a poor couple relationship or inadequate social support [9–12]. PTS is associated with traumatic birth events including changes to birth plan, birth before arrival to hospital, emergency caesarean birth, instrumental vaginal birth, and manual removal of the placenta; third and fourth-degree perineal tears are additional risk factors for PTS after birth [13, 14]. The experience of childbirth in and of itself is an independent factor associated with PTS and therefore preterm birth and neonatal complications are considered as add-on stressors [15].

The factors associated with developing postnatal mental health problems in parents of babies admitted to NNU have received comparatively little attention and are poorly understood. It is unclear whether the factors associated with increased risk of mental health problems in the general perinatal population are applicable to parents of babies admitted to NNU, or whether there are different or additional factors for this population. Factors such as the unexpected nature of many NNU admissions, separation from the newborn, and concern about the infant’s health make the experience of parents with babies receiving neonatal care different from that of other parents. Therefore, it is important to understand the risk and protective factors for this specific population to ensure that approaches for assessment, detection and intervention for perinatal mental health problems are optimally delivered and, if necessary, appropriately tailored.

The aim of the review was to systematically collate, appraise and synthesise the current evidence on risk and protective factors for developing PTS and anxiety in parents of babies admitted to NNU.

Methods

Operational definitions

There is no formal or internationally agreed definition of NNUs. The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s definition includes special care units (SCUs), local neonatal units (LNUs) and neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) [16]. The American Academy of Paediatrics’ definition of NNUs include basic care (level I), specialty care (level II), and subspecialty intensive care (level III, level IV) [17]. Within the context of this review we included studies on parents of babies admitted to any level of NNU.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [18] defines anxiety disorders as disorders that share features of excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioural disturbance. PTS is associated with exposure to trauma. Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) occurs within four weeks of a traumatic event, while Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) occurs when symptoms persist beyond one month. Throughout this review, the term ‘PTS’ is used to cover clinically significant ASD, PTSD or PTS symptoms and the term ‘anxiety’ is used to cover both clinically significant anxiety symptoms or disorders.

The review protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021270526) and reporting followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [19].

Eligibility criteria

Studies published in any language which examined the potential association of at least one risk factor with PTS or anxiety and were conducted with parents (mothers, fathers and carers) of babies admitted to any level of a NNU in all countries were included. Studies focusing on specific groups such as parents with existing mental health conditions or parents of deceased babies were also considered for inclusion. All observational study designs were eligible.

Search strategy and selection criteria

A comprehensive search strategy was developed and tested using a combination of free-text (title/abstract) keywords and MeSH subject terms to describe the key concepts of PTS/anxiety, parents and NNUs. The search covered the period from the inception of each database until December 2022. No restriction was applied to the electronic searches. The following databases were searched: Medline, Embase, PsychoINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health literature, Web of Science, ResearchGate and Google Scholar; Grey literature was also searched including Ethos, Proquest Dissertations & Theses and OpenGREY. The reference lists of all included studies were also searched for additional eligible studies. The search strategy applied in Medline is shown in Appendix 1.

Study selection and data extraction

All screening of titles, abstracts and full texts was conducted in Covidence [20]. A data extraction form was piloted on selected studies and was then employed for the remaining studies. Data on country, study design, aims, inclusion/exclusion criteria, characteristics of included parents and babies, PTS/anxiety measuring tools, assessment time, potential risk and protective factors relevant to PTS and anxiety, data analysis method and estimated effects for each risk factor were extracted. All screening and data extraction were independently performed by at least two reviewers (RM, VP, SH, FA). Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by a third author (FA, SH). Authors were contacted when required information was missing or when full texts were not available (N = 16).

Risk of bias assessment

The quality and certainty of evidence were assessed using a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [21]. The modified tool contains seven domains of bias relating to the following sources: selection, sampling, measurement of factors/outcome, analysis, selective reporting and attrition. Low, high or unclear risk rating was used to assess the potential bias for each domain.

Data synthesis

Summary statistics were extracted from all studies, including number of participants, number of risk factors and data relevant to each risk factor identified. When results from univariable and multivariable analyses were reported, only the latter were extracted. Meta-analyses by exposures/risk factors were not feasible due to the variability in the measurement of similar risk factors across studies (e.g. type of measurement tool, cut-off point, categorical or continuous data). Therefore, results were narratively synthesized and reported for PTS and anxiety separately.

Results

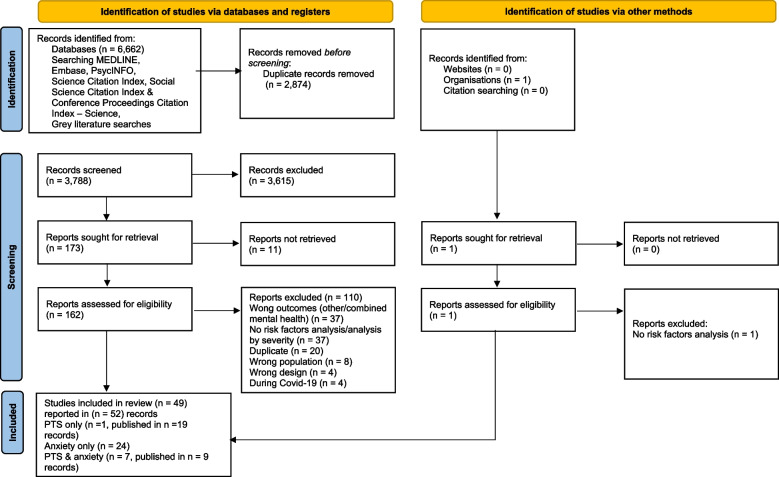

A total of 6,662 records were identified and, after removing duplicates, 3,788 records were screened, of which 3,615 records were excluded. 162 reports were assessed for full-text eligibility (11 reports could not be retrieved) and, of these, 110 reports were excluded with reasons and 49 studies, published in 52 records, were included. 18 studies, published in 19 records, reported on factors associated with PTS, 24 studies on anxiety and 7 studies, published in 9 records, reported on both, see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of study selection

Post-traumatic stress (PTS)

Description of the included studies

Table 1 presents the 25 studies published in 28 records [22–49] for PTS (including 7 studies reporting both PTS and anxiety). More than half of the studies were conducted in the USA [22, 25, 27–31, 34, 35, 41, 42, 44–47], five in Europe, published in six records [23, 26, 36, 37, 48, 49] two in Canada [32, 43], and one in each of the following countries: Australia [39], Argentina [40], Iran [38], South Korea [50] and Taiwan [24]. Six studies [24, 25, 27, 41, 44, 47] were of a cross-sectional design and the remaining studies were cohort studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of posttraumatic stress (PTS) included studies

| Study ID, country | Study design & setting, study period, neonatal unit type of care, length of stay | Study objective | Study inclusion criteria | Study exclusion criteria | Parents’ characteristics | Babies’ characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchan 2021, [22] USA | Prospective cohort,1 centre, June 2018-October 2019, NICU level 3, length of stay > 7 days | To determine the incidence of mental health symptoms in military families after NICU admission | Mothers and self-identified partners, > 18 yrs, English-speaking Department of Defense (DoD) Beneficiaries, infant remained admitted to NICU ≥ 7 days | Parents who were unable to maintain follow-up within military healthcare system beyond 7 days | N = 106 parents ( 66 mothers + 40 fathers) at 2 wks post birth (T1), N = 77 parents ( 53 mothers + 24 fathers) at 4–6 wks post NICU discharge (T2) Age – parents ≥ 35 yrs = 80 (75%) < 35 yrs = 26 (25%) SES—house income > $50.000 = 88 (83%) Ethnicity could select ≥ 1 White = 73 (69%), Other = 46 (31%) Education—college/trade school and higher = 74 (70%) LWP & parity = NR | N & BW = NR, GA = 35–38 and > 38 wks |

| Brunson 2021, [23] France | Prospective cohort, 3 centres, January 2008 and January 2011, NICU, length of stay = NR | To estimate the prevalence and predictive factors of mothers affected by posttraumatic symptoms after preterm birth | Mothers who delivered prematurely < 32 wks | Mothers with acute or chronic psychological illness, drug or alcohol abuse, underage, not speaking French For newborns life-threatening conditions, malformation and/or genetic abnormalities, and/or vulnerability of the baby evaluated by Perinatal Risk Inventory ≥ 10 |

N = 50 mothers Age = mean 30.9 ± SD 5.4 yrs Parity—nullips = 21 (42%) Education = graduated from high school = 40 (80%) SES, LWP & ethnicity = NR |

N = 50, GA = mean 209.8 ± SD 10.9 days, BW = mean 1331 ± SD 350 g |

| Chang 2016, [24] Taiwan | Cross-sectional, 1 centre, January 2010-June 2011, length of stay < 60.00 ± 53.78 days, NICU level = NR | To estimate the prevalence of symptoms of distress in mothers of preterm NICU infants and factors complications of delivery for these symptoms | Mothers to babies < 37 wks gestation, admission to the NICU, and infant survival at the time of the interview | Mothers who did not understanding Chinese, refused to consent, babies with congenital chromosomal abnormalities/congenital defects, significant heart disease after birth, or died during the hospital stay or after leaving the NICU Mothers with major illnesses, cancer, or psychiatric disorders |

N = 102 mothers Age = mean 34.28 ± SD, 4.45 Parity—nullips = 37 (36.27%) Education > 12 yrs = 95 (94.14%) SES—household income ≤ 600,000 NTD (about 19,679 USD) = 52 (50.98%) LWP & ethnicity = NR |

N = 102, GA = 31.53 SD ± 2.97 wks, BW = 1661.86 ± SD 563.82 g |

| Clark 2021, [25] USA | Cross-sectional, 1 centre, July 2009-July 2014, NICU level IV, length of stay = NR | To study the associations between parents perceptions of infant symptoms and suffering and parent adjustment following the baby death | Parents of infants who died within the previous five yrs in level IV NICU | Age < 18 yrs, infants died within the past 3 months, not speaking English |

N = 40 mothers, N = 27 fathers (27 mother-father dyads, 13 only mothers) Age – mothers = mean 33.33 ± 6 yrs Age – fathers = mean 36.74 ± 9.49 yrs LWP – mothers = 32 (80%) LWP – fathers = 24 (60%) Ethnicity – mothers = white 35 (88%) Ethnicity – fathers = white 16 (58%) Education – secondary—mothers = 34 (85%) Education—secondary – fathers = 18 (67%) SES—family income = range $50–75,000 for all Parity = NR |

N = 40, BW & GA = NR |

| Eutrope 2014, [26] France | Prospective cohort, 3 centres, January 2008-January 2010, NICU, length of stay = NR | To clarify the relationship between the mother’s post-traumatic reaction and premature birth and the mother-infant interactions | Mothers to infants < 32 wks | For mothers: Psychiatric illness, drug or alcohol abuse, aged < 18 yrs, language barriers; For newborns: Unfavourable vital prognosis evaluated Perinatal Risk Inventory score ≥ 10 infants risk of significant developmental disabilities and malformation and/or genetic anomaly diagnosed |

N = 100 mothers during 15 days after birth, N = 93 before NICU discharge Age = mean 329.8 ± 6 yrs Parity—nullips = 48 (48%) LWP = 92 (92%) Education – higher = 79 (79.29%) SES – employed = 69 (69%) Ethnicity = NR |

N = 100, BW = mean 1320g, GA < 32 wks |

| Garfield 2015 a [27], USA | Cross-sectional, 2 centres, length of stays = 31—211 days, mean = 93.1 ± SD 48.49 days, NICU level & period = NR | To identify risk factors among urban, low-income mothers, to enable NICU healthcare providers more effectively screening and referral | Mothers of VLBW < 1500 g and preterm < 37 wks, English peaking, no current mental health diagnosis, infants clinically stable and did not have a congenital neurological problems or symptoms of substance abuse | Mothers’ age < 18 yrs old, ongoing critical illness (HIV, seizure), major depression, psychosis, bipolar disease; mothers to infants receiving mechanical ventilation |

N = 113 mothers Age = mean 24.7 ± SD 5.17 yrs LWP = 59 (52.3%) SES—received public aid = 44 (39%) SES – uninsured = 45 (40%) Ethnicity—African American = 92 (81%) Education—high school graduates = 49 (43%) Parity = NR |

N = NR, GA < 37 wks, BW = mean 1,073 ± SD 342 g |

| Greene 2015 & 2019 a [28], USA | Prospective cohort, 1 urban centre, 2011–2012, NICU level IV, length of stay = mean 91 ± SD 37 days | To analyse change of depression, anxiety and perinatal-specific PTS across VLBW infants’ first year of life and to identify predictors of these changes over time | English-speaking mothers, > 18 yrs, babies likely to survive and VLBW < 1500 g | NR |

N = 69 at birth, N = 64 before NICU discharge Age = mean 27 ± SD 6 yrs Parity—nullips = 23 (34%) LWP = 32 (51%) Ethnicity—Black = 38 (54%), Non-Hispanic white = 18 (26%), Hispanic = 12 (17%), Asian = 1 (1%) Education – yrs of higher grade = 13.4 ± SD, 2.4 SES = NR |

N = 69, GA = mean 27.5 ± SD 2 wks, range 23.2 to 32.3 wks, BW = mean 957 ± SD, 243 g |

| Hawthorne 2016, [30] USA | Prospective cohort, 8 centres, period = NR, 4 NICU level III, 4 PICU, length of stay = NR | To test the relationships between spiritual/religious coping strategies and grief, mental health and personal growth for parents to babies died in intensive care unit | Parents were eligible for the study if their deceased newborn was from a singleton pregnancy and lived for more than 2 h in the NICU or their deceased infant/child was 18 yrs or younger and a patient in the PICU for at least 2 h | Parents who did not speak English or Spanish, multiple gestation pregnancy if the deceased was a newborn, being in a foster home before hospitalization, injuries suspected to be due to child abuse, death of a parent due to illness/injury event |

N = 165 both parents (114 mothers + 51 fathers) Age = mean mothers 31.1 ± SD 7.73 yrs, fathers = 36.8 ± SD 9.32 yrs LWP = mothers 84 (74%) LWP = fathers 43 (84%) SES – mothers employed = 63 (55%) SES- fathers employed = 32 (78%) Ethnicity – mothers white non -Hispanic = 22 (19%), black non-Hispanic = 50 (44%), Hispanic = 42 (37%) Ethnicity – fathers white non – Hispanic = 14 (28%) = black non-Hispanic = 16 (31%), Hispanic = 21 (41%), Education – mothers college degree = 35 (30%) Education – fathers college degree = 19 (37%) Parity = NR |

N = 124 (69 NICU and 55 PICU), GA & BW = NR |

| Holditch-Davis 2009 a [31], USA | Prospective cohort, 2 centres, NICU level & study period = NR | To examine inter-relationships among stress due to infant appearance and behaviour in the NICU exhibited by African American mothers of preterm infants | African American biological mothers of preterm infants < 1500 gm at birth or requiring mechanical ventilation. Mothers were recruited when their infants were no longer critically ill | Infants with congenital, symptomatic from substance exposure, hospitalized > 2 months post-term, or triplets or part of a higher order multiples set; mothers with no custody, follow-up for 2 yrs unlikely, HIV + , < 15 yrs, critically ill, not speak English, mental health problems |

N = 177 mothers Age = mean 25.9 ± SD 6.5 yrs LWP = 46 (26.1%) SES—Public assistance = 92 (52.8%) Education = mean 12.6 ± SD 1.8 yrs Ethnicity = all African American Parity = NR |

N = 190, mean GA = 28.3 SD ± 2.9 wks, mean BW = 1107 ± SD,394 g |

| Jubinville 2012, [32] Canada | Prospective cohort, 1 centre, February-May, 2008, NICU, level III, Length of stay = NR | To determine whether significant symptoms of (ASD) are present in mothers of premature NICU infants | Mothers of infants’ < 33 wks GA admitted to NICU | Infant with foetal anomaly, severe illness requires compassionate care and/ maternal illness precluded NICU visit and assessing women at 7–10 days after birth |

N = 40 mothers Age = mean 29.2 ± SD 5.8 yrs LWP = 37 (93%) SES—income $60, 000 per year = 23 (58%) Ethnicity = majority white Education—above high school = 24 (60%) Parity = NR |

N = 52, 10 twins, & one triplets, BW = mean 1374.5 ± SD 466.1 g range = 640–2220 g, GA = mean 29.0 ± SD 2.6 wks, range = 24.0–32.0 wks |

| Kim 2015, [33] South Korea | Prospective cohort, 1 centre, April to October 2009, NICU, level & length of stay = NR | To understand the progress and predictor factors of PTSD in mothers of high-risk infants | Mothers age of 18 to 45 yrs and who did not have a significant medical/surgical history that affected their performance on the self-report questionnaires | Mothers who did not speak Korean or problem executing the self-report questionnaires |

N = 120 mothers (90 without PTSD + 30 0 with PTSD) Age—no PTSD = mean 31.87 ± SD 3.50 yrs, Age – PTSD = mean 31.83 ± 3.23 yrs LWP – no PTSD = 89 (98.9%) LWP – PTSD = 30 (100%) SES—employed—no PTSD = 34 (39.5%) SES – employed—PTSD = 14 (50.0%) Education—level ≤ 14 yrs no PTSD = 32 (36.0%) Education—level ≤ 14 yrs PTSD = 10 (33.3%) Ethnicity & parity = NR |

N = NR, GA—no PTSD = mean 33.89 ± 3.76 wks GA – PTSD = mean 33.27 ± SD 3.91) wks, BW—no PTSD = mean 2.03 ± SD 0.78, BW—PTSD = mean 2.01 ± SD 0.72 kg |

| Lefkowitz 2010, [34] USA | Prospective cohort, 1 centre over a 9 months period, length of stay = median 14 days, NICU level = NR | To assess the prevalence and correlates of ASD and PTSD in mothers and fathers | Mothers and fathers of infants on NICU who were anticipated to stay on NICU > 5 days | Inability to read English, parent age < 18 yrs, or if the child’s death appeared imminent |

N = 130 parents ( 89 mothers + 41 fathers) Age—mothers = mean 29 yrs Age—fathers = mean 33 yrs Ethnicity—mothers Caucasian = 61 (71%), Ethnicity—fathers Caucasian = 33 (81%) Education—mothers college degree = 21 (24.4%) Education—fathers college degree = 9 (21.4%) Parity, LWP & SES = NR |

GA < 30 wks N & BW = NR |

| Lotterman 2018 a [45], USA | Prospective cohort, 1 centre, NICU level III & IV, period & length of stay = NR | To investigate whether rates of psychopathology are elevated in mothers of moderate- to late preterm infants during/following infant hospitalization in the NICU, and associated protective and risk factors | Mothers of moderate- to late preterm infants GA 32 to < 37 wks | Mothers to babies born < 32 wks or later than 36 wks, or if they had been in the NICU for > 6 months |

N = 91 mothers at NICU admission, N = 76 at 6 months Age = mean 32.45 SD ± 6.78 yrs Ethnicity = Caucasian 37 (40.7%), African American 15 (17.4%) Asian 9 (10.5%), American Indian/Alaskan Native 2 (2.3%), 27 (29.1%) other Education—mean yrs 14.29 ± SD 4.30 Parity, LWP & SES = NR |

N = 91, GA = range 32–37 wks, GA = mean 33.53 ± SD, 1.33 wks, BW = NR |

| Malin’s study, USA | ||||||

| Malin 2020 [46] | Cohort study, 1 centre, NICU – level IV, length of stay ≥ 14 days, period = NR | To determine if PTSD among parents after an NICU discharge can be predicted by objective measures or perceptions of infant illness severity | Parent of infants who were in NICU ≥ 14 days | Parents who did not speak English, infants discharged home with their non-biological parent, infant was previously discharged home or transferred to/from the cardiac ICU for surgery, infants who died in NICU |

N = 164 parents LWP = 154 (94%) SES—government insurance = 82 (50%) Parity, ethnicity & education = NR |

N = 164, GA = 23–28 wks (n = 36), 29–33 wks (n = 60), 34–36 wks (n = 29), > 37 wks (n = 39), BW < 1000 g (n = 28), BW > 1000 g (n = 136) |

| Malin 2022 [46] | Cohort study, 1 centre, September 2018-March 2020, NICU level IV, length of stay = mean 68.1 ± 65.6 days | To explore parents’ uncertainty during and after NICU discharge and the relationship between uncertainty and PTS | Parent of infants who were in NICU ≥ 14 days and had not previously been discharged from hospital |

Parents not fluent in English, parents of infants whose death appeared imminent or who would be transferred to cardiac ICU before discharge; parents who would not be caring for infant post-discharge, parents of infants who died after enrolment, only one parent of each infant could participate |

N = 319 parents during NICU, N = 245 parents at 3 months Age = mean 29.9 ± SD 5.59 yrs SES—unemployed = 52 (21%) Ethnicity = white 214 (67.3%), Black of African American 76 (24.0%), Asian 8 (2.5%), American Indian or Alaska Native 3 (0.1%), Other 17 (5.3%) Education—graduate 39 (12.2%) Parity & LWP = NR |

N = 243, GA = 22–25 wks = 34 (10.7%), 26–28 wks = 37(11.6%), 29-31wks = 60 (18.8%), 32–36 wks = 119 (37.3%), ≥ 37wks = 69 (21.6%) range 22- ≥ 37 wks, BW = NR |

| Misund 2013 & 2014 a Norway [36, 37], | Cohort study, 1 centre June 2005-July 2008, NICU level & length of stay = NR | To explore psychological distress, anxiety, and trauma related stress reactions in mothers experienced preterm birth and the predictors of maternal mental health problems | Mothers to preterm babies < 33 wks admitted to NICU | Mothers of severely ill babies that the medical staff estimated to have poor chance of survival, and non-Norwegian speakers |

N = 29 mothers at 2 wks post birth, N = 27 at 2 wks after NICU admission, N = 26 at 6 & 18 months post term, Age = mean age 33.7yrs ± SD 4.3 yrs Parity—nullips = 18 (62.1%) LWP = all SES – unemployed = 4 (13.8%) Education > 12 yrs = 26 (89.7%) Ethnicity = NR |

N = 35, GA = median 29, range 24–32) wks median BW = 1.2 kg (range 0.6–2.0), 40% twins |

| Moreyra 2021 a USA [47], | Cross-sectional, October 2017-July 2019, length of stay at least 14 days, number of centres, period & NICU level = NR | To describe the impact of depression, anxiety, and trauma screening protocol and the referral pf positively screened NICU parents | Parents of NICU babies admitted at least for 2 wks | None excluded |

N = 150 parents (120 mothers + 30 fathers) Age = 31.06 ± 6.26 yrs Parity—Para = mean 1.95 ± SD 1.2 LWP = 91 (61%) Ethnicity = white 39 26%, Other = 111 (74%) Education & SES = NR |

N = NR, mean GA = 32.3 ± 4.8 wks, BW = mean 1935.2 ± SD 1052.1 g |

| Naeem 2019, Iran [38] | Cohort, 2 hospitals, 2016, NICU level & length of stay = NR | To compare the prevalence of PTS and its related risk factors in parents of hospitalized preterm and term neonates | Parents of NICU preterm (GA 24—36 wks) and parents to hospitalized terms (GA > 38 wks), inafnts’ age 2–5 days | History of psychological or psychotic problems with the experience of hospitalization, medication or psychiatric consultation, underlying diseases, and drug abuse |

N = 160 parents (80 mothers + 80 fathers) Age – mothers = mean 33.78 ± SD 1.03 yrs Age – fathers = mean 37.14 ± SD 1.17 yrs LWP = all SES – employed = mothers 12 (15.25%) SES – employed = fathers 92.4% Education – mothers > high school = 72.2%, Education – fathers > high school = 52 (64.6%) Parity = NR |

N = 80, GA = 24–36 wks, BW = NR |

| Pace 2020, Australia [39] | Prospective cohort, 1 centre, 2011–2013, NICU level & length of stay = NR | To report the proportion of parents of VPT infants with PTS symptoms at different time points | Families with very preterm infants, GA < 30 wks admitted to NICU | Parents who did not speak English, infants with congenital abnormalities, unlikely to survive |

N = 105 parents (92 mothers and or 75 fathers) Age – mothers = mean 33 ± SD 5.3 yrs Age – fathers = 35 ± SD 6.2 yrs SES- high risk parents = 45 (43%) Education—mothers > 12 yrs = 62 (67%) Education – fathers > 12 yrs = 45 (60%) Parity, LWP & ethnicity = NR |

N = 131, GA < 30 wks, GA = mean 27.8 ± SD 1.5 wks, BW = mean 1,038 ± 261 g |

| Pisoni 2020 a Italy [49], | Prospective cohort, 1 centre, August 2013-April 2014, length of stay = mean 29, range 13–138 days, NICU level = NR | To examine maternal psychological, parental, perinatal infant variables and neurodevelopment | Preterm infants gestational age < 34 wks and their mothers age > 18 yrs old, speaking Italian | Congenital anomalies, infections, no psychiatric illness and/or drug abuse |

N = 29 mothers Age = mean 32.79 ± 6.74 yrs Parity—nullips = 19 (65.52%) SES—employed = 25 (86.21%) Education = mean 14.31 ± 2.78 yrs LWP & ethnicity = NR |

N = 29, GA = mean 30.23 ± SD 3.16, range 23–33 wks, BW = mean 528.9 5 ± SD 41.15 g, range 574–2327 g |

| Rodriguez 2020, Argentina [40] | Cohort, 1 centre, March 2014-November 2016, NICU level & length of stay = NR | To detect PTS frequency and symptoms among mothers of VLBW preterm < 32 wks | Mothers with singleton pregnancies to VLBW < 1,500g preterm babies < 32 wks | Mothers with psychiatric disorders before and/or during gestation, babies with chronic conditions & congenital malformations |

N = 146 mothers Age = range ≤ 21 to ≥ 42 yrs Parity, LWP, SE, ethnicity & education = NR |

N = 146, GA < 32 wks, BW < 1,500 g |

| Salomè 2022, Italy [48] | Prospective cohort, 1 centre, September 2018-September 2019, tertiary-level NICU, length of stay = NR | To determine the impact of parental psychological distress and psychophysical wellbeing on developing PTS at 1st yr post NICU discharge and any differences between mothers and fathers | Any couples to infants admitted to NICU during the study duration | NR |

N = 40 parents (20 couples, 20 mothers + 20 fathers) Age – mothers = mean 34 ± SD 6.6 yrs range 27 to 49 yrs LWP = all Education—university degree = 5 (25%) Parity, SES & ethnicity = NR |

N = 23, BW = mean 1,375 ± SD 458.57 g, range = 760–2500 g, GA = mean 31 ± SD 2.99 wks range = 25 to 36 wks |

| Sharp 2021, USA [41] |

Cross-sectional – media survey, November 2015- July 2016, length of stay = 29.57 (26.79) days, number of centres and NICU level = NR |

To report on maternal perceived stress to infants’ NICU admission and the relationship between traumatic childbirth and PTSD | Biological mothers ≥ 18 yrs old, USA residents, complete the survey in English, alive infants age 1–4 months | Completing < 75% of the survey, infants age > 1–4 months |

N = 77 mothers Age = mean 39.6 ± 5.8 yrs Parity—nullips = 32 (41.6%) SES—unemployed = 26 (47%) Ethnicity = White 68 (88.3%), Hispanic 7 (9.1%) Education (Bachelor’s degree or above) = 35 (45%) |

N = NR, BW < 2,500g = 47 (61.0%) , GA < 37 wks = 43 (55.8%) |

| Shaw 2009, USA [42] | Prospective cohort, 1 centre, NICU, length of stay = mean 12 ± 8 days, study period = NR | To describe the early-onset symptoms of ASD in parents and factors related to PTSD, identifying high-risk parents who may benefit from early intervention | English-speaking parents of NICU infants | NR |

N = 40 parents (25 mothers + 15 fathers) Age – mothers = 34.55 ± SD, 4.41 yrs LWP = all SES – employed = mothers 18 (72%) SES – employed = fathers all Ethnicity – mothers = white 15 (60%) Ethnicity—fathers = white 12 (92.3%) Education—university and above = mothers 17 (52%) Education – university and above = fathers 12 (92%) Parity = NR |

N = NR GA = 30.89 SD ± 4.11 wks, range = 27 to 41 wk, BW = mean 1,664.39 ± SD, 908.21 g range = 1052 to 4004 g |

| Vinall 2018, Canada [43] | Cohorts, 1 centre, July 2012 and March 2016, length of stay = mean 57.89 ± SD 35.87 days, NICU level = NR | To examine whether the number of invasive procedures together with mother’s memory for these procedures were associated with PTSS at discharge from the NICU | Mothers of infants < 37 wks GA | Infants were excluded if they had major congenital anomalies, were receiving opioids, or underwent surgery |

N = 36 mothers Age = median 31, IQR 27–36 yrs Education = median 5 IQR, 4–5 yrs, Parity, LWP, SES & parity = NR |

N = 36, GA median (IQR) 32 (30–34) wks, BW = NR |

| Williams 2021, USA [44] | Cross sectional, 1 centre, over 6 months, date = NR, level IV NICU, length of stay = 44.82 ± 51.37 days | To evaluate acute stress disorder (ASD) symptoms and their predictors in NICU mothers | English speaking biological mothers | Mothers with infants with brief lengths of stay |

N = 119 mothers SES—Medicaid insurance = 85 (71.8%) Ethnicity = African American 58 (48.7%), Caucasian 47 (39.5%), Hispanic/Latinos 10 (7.6%), Asians 3 (2.5%) Education – college degree or higher = 41 (33.6%) Age, parity & LWP = NR |

N = 115, GA = 33.2 ± 4.66 < 28 wks to > 37 wks, BW = 2278.43 ± 1037 g |

Abbreviations: ASD Acute stress disorder, BW Birth weight, FT Full term, GA Gestational age, HIV Human immunodeficiency virus, IQR Interquartile range, T1 Time one, T2 Time two, LWP Living with partner (married or cohabit), NICU Neonatal intensive care unit, NR Not reported, Nullips Nulliparous, N Number of parents, PTSD Post-traumatic stress disorder, PT Preterm, SD Standard deviation, SES Socio-economic status, wks Weeks, yrs Years, VLBW Very low birth weight, VPT Very preterm

aStudies included in both post-traumatic stress and anxiety: Garfield 2015 [27], Greene 2015 & 2019 [28, 29] Holditch-Davis 2009 [31], Lotterman 2018 [45], Misund 2013 & 2014 [36, 37] Moreyra 2021 [47], Pisoni 2020 [49]

Two studies included bereaved parents of babies who had been admitted to NNU [25, 30] and one study [22] focused entirely on military families. Both parents were included in ten studies, published in 11 records [22, 25, 30, 34, 35, 38, 39, 42, 46–48] and only mothers were enrolled in the remaining studies. Gestational age (GA) of the infant was an inclusion criterion in nine studies published in ten records [23, 24, 26, 32, 36–39, 43, 45], and birth weight (BW) was a criterion in two studies published in three records [28, 29, 31]. Two studies included both GA and BW in their inclusion criteria [27, 40]. All studies used standardised self-report scales.

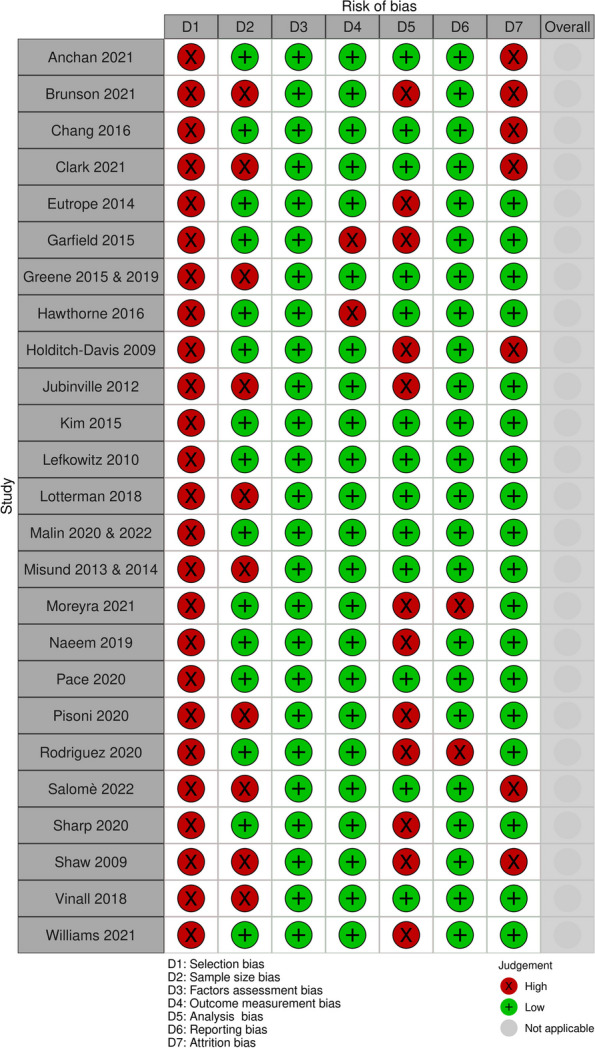

Risk of bias assessment

None of the included studies were at low risk of bias across all domains (see Fig. 2- A summary of risk of bias of PTS studies and Appendix 2). All studies had high risk of selection bias because all applied some exclusion criteria and most used convenience sampling. Ten studies, published in 12 records [23, 25, 28, 29, 32, 36, 37, 42, 43, 45, 48, 49], did not employ adequately powered sample sizes. Twelve studies [23, 26, 27, 31, 32, 38, 40–42, 44, 47, 49] had high risk of analysis bias due to unmeasured confounding factors or correlational analysis only, and seven studies [22–25, 31, 42, 47] had high risk of attrition bias due to low participation rates or high loss to follow-up. All except two studies [40, 47] had low risk of reporting bias. All studies were at low risk of bias for factor and outcome measurement.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary of post-traumatic (PTS) included studies

Factors associated with post-traumatic stress (PTS)

Overall, 2,506 parents were involved across the 25 included studies with sample sizes ranging from 29 to 245 participants. A total of 62 potential risk or protective factors were identified. The factors are detailed in Table 2, presented in a mapping diagram in Table 3 and summarised here under the following eight categories: parent demographic factors; pregnancy and birth factors; infant demographic factors; infant health factors; parent history of mental health symptoms; parent postnatal psychological factors; parent stress and coping, and other factors.

1) Parent demographic factors (Ten factors: age, education, sex, ethnicity, parents’ area deprivation, income, employment status, housing and access to transport, single parent, family social risk)

Table 2.

Summary of factors reported in posttraumatic stress (PTS) included studies

| Study ID | Study population | Time of PTS assessment | PTS measuring tool and cut-off points | Parents with PTS, N, n (%) | Statistical analysis | Factors (assessment time) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchan 2021 | Military families | 2 wks after birth | Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire (SASRQ) ≥3 score one at least 1 relevant item | Parents N = 106, n = 26 (24.5%) | Multivariable logistic regression | Factors (2 wks after birth) | OR | 95%CI | ||||||

| Parent role alteration | 1.19 | 0.47, 3.03 | ||||||||||||

| Parent sex | 1.20 | 0.47, 3.01 | ||||||||||||

| Active military service | 0.73 | 0.3, 1.79 | ||||||||||||

| Pre-existing mental health disorders (PMHD) | 3.32 | 1.07, 10.3 | ||||||||||||

| History of significant family geographic separation (SFGS) | 2.0 | 0.72, 5.54 | ||||||||||||

| GA ≤ 35 vs >35 wks | 1.64 | 0.73, 3.72 | ||||||||||||

| Parent-reported infant illness severity | 1.29 | 0.53, 3.12 | ||||||||||||

| 4-8 weeks post discharge | PLC-5 screening in each PTSD symptom cluster (re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and hyperarousal) | Parents N = 77, n = 6 (7.8%) | Multivariable logistic regression | Factors (4-6 wks post NICU discharge) | OR | 95%CI | ||||||||

| Parent role alteration | 0.9 | 0.15, 5.26 | ||||||||||||

| Active military service | 0.5 | 0.09, 3.16 | ||||||||||||

| PMHD | 1.8 | 0.19, 17.96 | ||||||||||||

| History of significant family geographic separation (SFGS) | 1.1 | 0.2, 6.75 | ||||||||||||

| GA | 0.4 | 0.1, 2.2 | ||||||||||||

| Parent-reported infant illness severity after admission (1 vs >1) | 2.1 | 0.37, 12.65 | ||||||||||||

| Parent-reported infant illness severity after discharge (1 vs >1) | 3.7 | 0.68, 20.4 | ||||||||||||

| Positive screening for ASD (SASRQ) | 2.0 | 0.34, 12.26 | ||||||||||||

| Positive screening for depression after admission (PHQ-2) | 2.0 | 0.34, 12.26 | ||||||||||||

| 4-8 wks post NNU discharge | PCL-5 | Parents N = 77, n = 28 (36.4%) | Multivariable logistic regression | Factors (4-8 wks after NICU discharge) | OR | 95%CI | ||||||||

| Parental role – alteration | 2.94 | 0.95, 9.09 | ||||||||||||

| Active military service | 0.62 | 0.24, 1.59 | ||||||||||||

| Pre-existing mental health disorders (PMHD) | 1.88 | 0.43, 8.17 | ||||||||||||

| History of significant family geographic separation (SFGS) | 1.72 | 0.64, 4.68 | ||||||||||||

| Gestational age (GA) | 0.87 | 0.3, 2.12 | ||||||||||||

| Parent-reported infant illness severity after admission 1 vs >1 | 2.06 | 0.8, 5.31 | ||||||||||||

| Parent-reported infant illness severity after discharge 1 vs >1 | 3.88 | 1.29, 11.69 | ||||||||||||

| Positive screening for ASD (SASRQ) | 8.44 | 2.38, 29.96 | ||||||||||||

| Positive screen after admission - Public Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) | 5.69 | 1.72, 18.83 | ||||||||||||

| Brunson 2021 | Mothers to babies < 32 wks | 18 months after birth | mPPQ ≥ 19 | Mothers N = 50, n = 18 (36%) | Univariate parametric tests |

Reported: HADS depression at 18 months P = 0.02, HADS anxiety at 18 months P = 0.02 Primiparous, In vitro fertilisation, Multiple pregnancy, Threatened preterm labour, C-section, Psychological support, graduated from high school p >0.05. |

||||||||

| Mothers mPPQ ≥19 VS <19 | ||||||||||||||

| Factors (18 months after birth) | Mean difference | 95%CI | ||||||||||||

| Gestational age in days | -6.40 | -12.36, -0.44 | ||||||||||||

| BW kg | -0.19 | -0.39, 0.00 | ||||||||||||

| PRI score at birth | 0.80 | -0.67, 2.27 | ||||||||||||

| Maternal age | 2.50 | -0.33, 5.33 | ||||||||||||

| Factors | OR | 95%CI | ||||||||||||

| Male sex | 1.19 | 0.37, 3.79 | ||||||||||||

| Apgar score < 7 at 5min | 0.83 | 0.25, 2.72 | ||||||||||||

| Graduated from high school | 1.28 | 0.30, 5.54 | ||||||||||||

| Primparous | 1.39 | 0.43, 4.56 | ||||||||||||

| IVF | 0.40 | 0.06, 2.62 | ||||||||||||

| Multiple pregnancy | 0.58 | 0.14, 2.37 | ||||||||||||

| Threatened preterm labour | 2.22 | 0.57, 8.68 | ||||||||||||

| CS | 3.49 | 1.01, 12.05 | ||||||||||||

| HADS anxiety > cut off | 4.33 | 1.03, 18.18 | ||||||||||||

| HADS depression > cut off | 3.24 | 0.61, 17.31 | ||||||||||||

| Psychological support | 1.92 | 0.31, 12.05 | ||||||||||||

| Clark 2021 | Parents to deceased preterm | 3 months to 5 years after infant death Mean 8.65 months (SD, 16.9) | IES-R ≥ 33 | Mothers N = 40, n = 7 (18%) | Multivariable hierarchical linear regression | Factors (3 months-5 years after death) | B | P value | ||||||

| Step 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Education | -0.31 | < 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Income | -0.15 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Medical Interventions (Chart) | 0.12 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Step 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Infant Symptoms - Mother | 0.46 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Fathers 27, 3 (11%) | Multivariable hierarchical linear regression | Factors | B | P value | ||||||||||

| Step 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Income | -0.35 | < 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Infant Suffering - Father | 0.60 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Parent sex OR 1.70, 95%CI 0.40, 7.24 | ||||||||||||||

| Eutrope 2014 | Mothers to preterms born < 32 wks | Visit 1 (v1) within 15 days after birth and visit 2 (v2) before NICU discharge | mPPQ ≥ 19 | Mothers N = 100, mean 16.4 ± SD 9.9 | Correlation | Factors ( at v1 and v2) | r | P value | ||||||

| State of health of the child (Perinatal Risk Inventory) | 0.25 | 0.04 | ||||||||||||

| State of health of the child (PRI v2 - PRI v1) | 0.25 | 0.04 | ||||||||||||

| Increase BW | -0.23 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| HADS depression score assessment within 15 days after birth (v1) | 0.54 | < 0001 | ||||||||||||

| HADS depression score assessment before discharge (v2) | 0.48 | < 0001 | ||||||||||||

| HADS anxiety score v1 | 0.54 | < 0001 | ||||||||||||

| HADS anxiety score v2 | 0.52 | < 0001 | ||||||||||||

| HADS global score v1 | 0.60 | < 0001 | ||||||||||||

| HADS global score v2 | 0.56 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Satisfaction of perceived social support (SSQ ) v1 | -0.23 | 0.03 | ||||||||||||

| SSQ v2 | -0.22 | 0.04 | ||||||||||||

| Postnatal depression v2 | 0.50 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Garfield 2015 a | Low income mothers to very low BW < 1500 g | First 3 months after birth | PPQ ≥ 6 | Mothers N = 113, n = 34 (30%) | Correlation | Factors (First 3 months after birth) | r | P | ||||||

| State Anxiety | 0.51 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Maternal age > 35 yrs | -0.02 | NS | ||||||||||||

| NBRS | 0.17 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Education | 0.02 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Parental stress | 0.50 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Greene 2015 & 2019 | ||||||||||||||

| Greene 2015a | Mothers to very low BW < 1500 g | T1 (mean 28.1 days after birth), T2 (mean 14.8 days prior to NICU discharge) | mPPQ ≥ 19 | Mothers N = 69, T1=17 (25%), T2=16 (25%), T1 and/or T 2 =22 (34%) | Multivariable logistic regression | Factors (Mean 14.8 days before NICU discharge) | OR | 95%CI | P value | |||||

| Previous Exposure to Traumatic Events | 1.07 | 1.01, 1.13 | < 0.05 | |||||||||||

| Primiparaous | 4.80 | 1.26, 18.31 | < 0.05 | |||||||||||

| Greene 2019a | T1 (mean 28.1 days after infants’ birth);T2 (mean 14.8 days prior to infants’ NICU discharge); T3 (infants’ 4 month CA follow-up visit); T4 (infants’ 8 month CA follow-up visit) | PPTS score at T1= mean 13.43 | Multivariable hierarchical linear regression | Factors (At birth) | Mean | 95%CI | P | |||||||

| Increase BW g at birth | −0.02 | −0.03, −0.01 | 0.005 | |||||||||||

| Older maternal age (years) at birth | -0.37 | -0.84, 0.10 | 0.12 | |||||||||||

| Previous traumatic events (per event) | 1.23 | 0.14, 2.3 | 0.03 | |||||||||||

| Neighbourhood poverty (z-score) | -30.92 | -54.3, −7.5 | 0.01 | |||||||||||

| Factors (Over 1st year of life) | Mean | 95%CI | P | |||||||||||

| Increase BW (g) at birth | 0.001 | -0.001, 0.002 | 0.16 | |||||||||||

| Older maternal age (years) at birth | 0.05 | 0.00, 0.11 | 0.05 | |||||||||||

| Previous traumatic events (per event) | -0.06 | -0.18, 0.07 | 0.36 | |||||||||||

| Neighbourhood poverty (z-score) | 1.73 | −0.96, 4.40 | 0.20 | |||||||||||

| Hawthorne 2016 | Bereaved parents after neonatal (NICU) or paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) death | 1& 3 months after death | IES-R, cut-off = NR | Parents N=165 ( 114 mothers and 51 fathers), n = NR | Multivariable linear regression | Factors (1 & 3 months after death) | β | 95%CI | P | |||||

| Spiritual activities at 1 & 3 months mothers | −0.33 & −0.35 | NR | < 0.01 | |||||||||||

| Spiritual activities at 1 & 3 months fathers | −0.29 & −.07 | NR | NS | |||||||||||

| Religious activities at 1 & 2 months mothers | −0.10 & −0.08 | NR | NS | |||||||||||

| Religious activities at 1 & 2 months fathers | −0.12 & −0.03 | NR | NS | |||||||||||

| Adjusted for race/ethnicity and religion | ||||||||||||||

| Holditch-Davis 2009 |

African-American mothers < BW 1500 g infants |

During NCU admission | PPQ ≥ 6 | Mothers = 117, n = 50 (42.9%) | Correlation | Factors (During NICU) | r | P value | ||||||

| PSS subscale: Infant appearance | 0.49 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| PSS subscale: Parental role alteration | 0.54 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Depressive symptoms at enrolment | 0.73 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| State anxiety at enrolment | 0.55 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Jubinville 2012 | Mothers of infants born < 33 wks | One wk (T1) and one month after birth (T2) |

Acute Stress Disorder Interview (ASDI) & Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire (SASRQ) >37 |

Mothers N = 40 T1 ASDI n= 11 (28%), SASRQ n = 20 (50%) T2 n = 34 ASDI (18%) SASRQ n= 14 (41%) |

Correlation | Factors (1 week after birth) | r | P value | ||||||

| Depression | NR | 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Kim 2015 | Mothers to infants born at GA mean 33.89 (SD 3.76) wks | when infants 1 month corrected age (CA), 3 months CA, 12 months CA | mPPQ ≥ 19 | Mothers = 120, n = 33 (28%) | Multivariable logistic regression | Factors (1 year CA) | aOR | 95%CI | P value | |||||

| Age of mothers | 1.13 | 0.93, 1.37 | 0.234 | |||||||||||

| Low education of mothers (<14 years) | 2.33 | 0.59, 9.13 | 0.226 | |||||||||||

| First-born baby | 7.62 | 1.07, 54.52 | 0.043 | |||||||||||

| Twin | 4.60 | 0.60, 35.43 | 0.143 | |||||||||||

| GA at birth | 0.98 | 0.81, 1.19 | 0.854 | |||||||||||

| Apgar score, 5 min | 1.02 | 0.59, 1.77 | 0.938 | |||||||||||

| Emergency visit or rehospitalisation | 2.82 | 0.79, 10.09 | 0.111 | |||||||||||

| Adjusted odd ratio (OR) by all the other variables | ||||||||||||||

| Lefkowitz 2010 | Parents of NNU infants | 3–5 days after the infant’s NICU admission |

Acute Stress Disorder Scale (ASDS) ≥ 1 symptom Of dissociation, re- experiencing, avoidance and arousal |

Parents N = 130, n = 42 (32%) | Correlation | Factors (During NICU) | r | P value | ||||||

| Length of NICU stay | -0.21 | < 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Parent age | -0.07 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Minority | 0.07 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Family history of depression | 0.02 | < 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Concurrent stressors | 0.15 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Parent-rated medical severity | 0.01 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Physician rated medical severity | -0.05 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Parent sex | OR 1.50 | 95%CI 0.58, 3.87 | ||||||||||||

| 30 days post NICU admission | PTSD presence of ≥ symptom ((dissociation, re-experiencing, avoidance, and arousal) plus moderate level of impairment | n = 9 (11%) | Multivariable linear regression | Factors (At 30 days post admission) | unstandardized B | SE | Β | P value | ||||||

| Total ASDS score | 0.31 | 0.053 | 0.47 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Family history of depression | 6.07 | 2.21 | 0.23 | 0.008 | ||||||||||

| Family history of mental Illness | 12.28 | 4.27 | 0.24 | 0.005 | ||||||||||

| Number of concurrent stressors | 2.56 | 0.86 | 0.23 | 0.004 | ||||||||||

| Parent sex at 30 days OR 2.03, 95%C I 0.41, 10.15 | ||||||||||||||

| Lotterman 2018 | Mothers of moderate- to late-preterm infants | During NICU stay and 6 months later | PCL > 38 |

Mothers N = 91, n = 14 (15.40%), 6 months n = 15 (15.8%) |

Multivariable linear regression | Factors (During NICU) | B | SE | P value | |||||

| Previous Mental Illness (PMI) | 124.23 | 55.73 | ≤ 0.05 | |||||||||||

| Mother-Infant Contact (MI) (verbal and physical) | -1.39 | 0.99 | NS | |||||||||||

| PMI x MI Contact | -12.45 | 5.93 | ≤0.05 | |||||||||||

| Infant health problem (IHP) | 9.48 | 11.88 | NS | |||||||||||

| Mother-Infant Contact (MI) | -1.34 | 1.34 | NS | |||||||||||

| IHP x M-I Contact | -0.79 | 1.33 | NS | |||||||||||

| Forward-Focused (FF) Coping | -0.66 | 0.54 | NS | |||||||||||

| NICU mother-Infant (MI) Contact ( physical and or verbal) | -5.18 | 4.07 | NS | |||||||||||

| FF x MI | 0.05 | 0.06 | NS | |||||||||||

| Linear regression at 6 months | Factors (At 6 months) | B | SE | P value | ||||||||||

| Baseline PTSD | 0.18 | 0.18 | NS | |||||||||||

| Mother visits per week | -0.49 | 1.49 | NS | |||||||||||

| Positive mother-nurse interaction | 2.13 | 4.10 | NS | |||||||||||

| Mother-understands explanations | -4.47 | 3.31 | NS | |||||||||||

| Mother-technical questions | -0.92 | 2.34 | NS | |||||||||||

| Mother-asks how to baby care | 1.66 | 3.70 | NS | |||||||||||

| Optimism | -0.43 | 0.22 | ≤ 0.05 | |||||||||||

| Length of Stay (days) | 0.6 | 0.3 | ≤ 0.05 | |||||||||||

| Mother-Infant Contact/NICU visit | -2.67 | 0.76 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Infant Health Problems by the mothers | 2.0 | 0.87 | ≤ 0.05 | |||||||||||

| Pessimism about baby’s recovery (Baseline) | 0.1 | 0.14 | NS | |||||||||||

| Length of Stay (days) X Pessimism | 0.01 | 0.0 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Malin 2020 & 2022 | ||||||||||||||

| Malin 2020 | Parents to babies born 23 to < 37 wks | 3 months after discharge | PPQ ≥ 19 | Parents N = 164, n = 41 (25%) | Multivariable logistic regression | Factors (3 months post discharge) | OR | 95%CI | P value | |||||

| Clinical illness indicator | 3.10 | 1.1, 9.0 | 0.040 | |||||||||||

| Parent perceives “sick” | 3.80 | 1.2, 12.6 | 0.027 | |||||||||||

| Interaction between clinical illness/parent perceives “sick” | 0.70 | 0.1, 3.9 | 0.696 | |||||||||||

| Nurses perceives “sick” | 1.00 | 0.3, 3.4 | 0.999 | |||||||||||

| Physicians perceives “sick” | 1.70 | 0.6, 5.1 | 0.355 | |||||||||||

| History of mental health (yes=1) | 0.90 | 0.4, 2.1 | 0.767 | |||||||||||

| Single parent | 1.70 | 0.4, 8.0 | 0.510 | |||||||||||

| Malin 2022 | At 3 months after discharge | PPQ ≥ 19 | Parents N = 245, n = 91 (36%) | T test comparing PTS positive vs PTS negative | Factors (3 months post discharge) | PTS positive N (%) | PTS negative N (%) | χ2T‐test | ||||||

| GA | ||||||||||||||

| 22−25 wks | 13 (48) | 14 (52) | 0.16 | |||||||||||

| 26−28 wks | 14 (50) | 14 (50) | ||||||||||||

| 29−31 wks | 12 (28) | 31 (72) | ||||||||||||

| 32−36 wks | 29 (32) | 66 (68) | ||||||||||||

| ≥37 wks | 18 (36) | 32 (64) | ||||||||||||

| ≤28 wks vs >28 wks | OR 1.42, 95%CI 0.90, 2.24 | P = 0.13 | ||||||||||||

| Palliative care consultation | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 5 (63) | 3 (37) | 0.10 | |||||||||||

| No | 81 (34) | 154 (66) | ||||||||||||

| Ventilator days | ||||||||||||||

| 0 days | 26 (25) | 77 (75) | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| 1−7 days | 28 (39) | 43 (61) | ||||||||||||

| 8−30 days | 9 (32) | 19 (68) | ||||||||||||

| >30 days | 23 (56) | 18 (44) | ||||||||||||

| Vasopressors | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 30 (51) | 29 (49) | <0.001 | |||||||||||

| No | 56 (30) | 128 (70) | ||||||||||||

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | ||||||||||||||

| None | 54 (33) | 109 (67) | 0.10 | |||||||||||

| Mild | 1 (17) | 5 (83) | ||||||||||||

| Moderate | 8 (30) | 19 (70) | ||||||||||||

| Severe | 22 (51) | 21 (49) | ||||||||||||

| Seizures | N (%) | N (%) | 0.91 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | ||||||||||||

| No | 84 (35) | 153 (65) | ||||||||||||

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy | N (%) | N (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 0.24 | |||||||||||

| No | 83 (35) | 155 (65) | ||||||||||||

| Length of NICU hospitalization in days | Mean (SD) 81.5 (69.9) | Mean (SD) 56.4 (57.4) | 0.01 | |||||||||||

| Parents’ age | Mean (SD) 29.9 (5.88) | Mean (SD) 29.7 (5.05) | 0.84 | |||||||||||

| Ethnicity | N (%) | N (%) | ||||||||||||

| Black or African American | 13 (28) | 33 (72) | ||||||||||||

| White | 70 (40) | 107 (60) | 0.13 | |||||||||||

| Asian | 0 | 6 (100) | ||||||||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 2 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Other | 3 (27) | 8 (73) | ||||||||||||

| Housing | ||||||||||||||

| Has housing | 83 (35) | 153 (65) | 0.48 | |||||||||||

| Does not have housing | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | ||||||||||||

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | ||||||||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||||

| Not finished high school | 7 (54) | 6 (46) | 0.61 | |||||||||||

| High school graduate | 13 (30) | 31 (70) | ||||||||||||

| Some college of technical school | 21 (37) | 36 (63) | ||||||||||||

| College or technical school graduate | 34 (35) | 64 (65) | ||||||||||||

| Graduate school | 11 (35) | 20 (65) | ||||||||||||

| Employment | ||||||||||||||

| Unemployed | 18 (35 | 34 (65) | 0.73 | |||||||||||

| Part‐time or temporary work | 12 (34) | 23( 66) | ||||||||||||

| Full‐time | 50 (37) | 84 (63) | ||||||||||||

| Unemployed | 6 (32) | 13 (68) | ||||||||||||

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 3 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Lack of transportation | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 7 (64) | 4 (36) | 0.05 | |||||||||||

| No | 79 (34) | 152 (66) | ||||||||||||

| History of mental illness | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 52 (50) | 51 (50) | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| No | 30 (23) | 101 (77) | ||||||||||||

| Do not know | 3 (37) | 5 (63) | ||||||||||||

| Family history of mental illness | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 47 (48) | 51 (52) | 0.001 | |||||||||||

| No | 34 (26) | 98 (74) | ||||||||||||

| Do not know | 5 (38) 9 62 | 9 (62) | ||||||||||||

| Uncertainty about infant’s health at NICU | Mean 71.6 (SD 17.2) | Mean 65.4 (SD 16.2) | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Uncertainty about infant’s health at 3 months | Mean 67.6 (SD 16.8) | 60.4 (SD 16.2) | < 0.001 | |||||||||||

| Misund 2013 & 2014 a | Mothers to infants < 33 wks | 2 weeks after hospitalization | IES ≥ 19 |

Mothers N = 29, n = 13 (44.8%) |

Multivariable linear regression | Factors (2 wks after hospitalisation) | B | 95%CI | P value | |||||

| Preeclampsia | 5.75 | 1.22, 10.27 | 0.015 | |||||||||||

| IVH | 11.34 | 3.17, 19.50 | 0.008 | |||||||||||

| Mother's age | 0.91 | 0.18, 1.64 | 0.016 | |||||||||||

| Planned caesarean section vs normal birth | -14.46 | -27.67,−1.25 | 0.033 | |||||||||||

| Moreyra 2021 a | Mothers and fathers to NICU infants | 14 days post NICU admission | PPQ ≥ 19 |

Mothers and fathers N = 150, n = 25 (17%) |

Difference between the groups using t-test and correlation analysis | Factors (During NICU stay at 14 days post admission) | T test | P | ||||||

| Parents sex mothers vs fathers | 6.53 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | NR | NS | ||||||||||||

| Correlation | r | P | ||||||||||||

| Anxiety | 0.79 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Naeem 2019 | Mothers and fathers to infants born 24-36 weeks | 3-5 days after birth | Questionnaires for acute stress disorder (ASD) part of a clinical interview ≥ 56 |

Mothers N = 80, n = 26 (32.5%) fathers N = 80, n = 3 (4%) |

Univariable logistic regression | Factors (3-5 days after birth) | P value mothers | P value fathers | ||||||

| Father unemployment | 0.22 | 0.22 | ||||||||||||

| History of an accident during recent years for father | 0.10 | 0.73 | ||||||||||||

| Mother employment | 0.82 | 0.46 | ||||||||||||

| History of an accident during recent years for mother | 0.002 | 0.50 | ||||||||||||

| Parent sex | OR 12.36, 95%CI 3.56, 42.91 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| 1 month after the first assessment | PCL ≥ 30 and PPQ > 30 | Parents N = 160 mothers N= 80, n = 63 (40%), fathers N = 80, n = 34 (21.5%) | Non paramedic test | Factors (1 month post first assessment) | P value mothers | P value fathers | ||||||||

| Father’s unemployment | 0.02 | 0.23 | ||||||||||||

| History of an accident during recent years for father | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Mother employment | 0.038 | 0.46 | ||||||||||||

| History of an accident during recent years increase mothers | 0.002 | 0.09 | ||||||||||||

| Parent sex OR 5.01, 95%CI 2.50, 10.05 | ||||||||||||||

| Pace 2020 |

Parents of infants born < 30 wks |

At TEA, 12, 24 months, |

PCL ≥ 30 |

Parents N = 105 (92 mothers and or 75 fathers) At TEA, 12, 24 months, PTSS n = 32 (36%), n = 12 (22%), n = 17 (18%) mothers & n = 26 (35%), n = 13 (25%), n = 14 (19%) fathers |

Multivariable hierarchical logistic regression | Factors (12 and 24 months CCA) | OR | 95%CI | P | |||||

| Medical risk | 2.09 | 0.81, 5.38 | 0.13 | |||||||||||

| Multiple birth | 2.18 | 0.80, 5.93 | 0.13 | |||||||||||

| Social risk | 1.66 | 0.64, 4.30 | 0.30 | |||||||||||

| Parent sex at 12 months | 1.06 | 0.56, 2.0.4 | NS | |||||||||||

| Parent sex at 24 months | 0.97 | 0.44, 2.13 | ||||||||||||

| Pisoni 2020 a | Mothers to infants born < 24 wks | During NICU stay & 12 months infant corrected age | mPPQ, cut-off = NR | Mothers N = 29, during NICU n = 5 (17.25%), at 12 months 9 (31.05%) | Correlation | Factors (during NICU) | r | P value | ||||||

| Perinatal risk inventory (PERI) | 0.611 | < 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Dyadic Synchrony Care Index | 0.144 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Factors (At 12 months) | r | P value | ||||||||||||

| Perinatal risk inventory (PERI) | 0.098 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Generalised Developmental Quotient (GQ) | -0.22 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Dyadic Synchrony Care Index | 0.009 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Rodriguez 2020 |

Mothers of infants born < 32 wks |

6 months after birth to > 36 months | Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) - DSM-IV | Mothers N = 146, n = 64 (44%) | Mantel-Haenzel method | Factors (6 to > 36 months) | OR | 95%CI | P value | |||||

| GA ≤ 28 vs 29-31.6 wks | 3.97 | 1.89, 8.33 | 0.0003 | |||||||||||

| BW < 1000 g vs 1000-1490 g | 2.19 | 1.12, 4.27 | 0.02 | |||||||||||

| Neonatal morbidity | NR | NR | 0.072 | |||||||||||

| Baby severe vs mild/moderate morbidity | 2.26 | 1.12, 4.55 | 0.02 | |||||||||||

| Maternal age ≤21-31 vs ≥32 years | 1.51 | 0.76, 3.00 | 0.24 | |||||||||||

| Children’s age 7-24 months vs 25 to > 36 months | 0.75 | 00.37, 1.53 | 0.43 | |||||||||||

|

Length of stay NICU |

NR | 0.316 | ||||||||||||

| Logistic regression | Factors | OR | 95%CI | P value | ||||||||||

| lower level of education | 0.871 | 0.771, 0.984 | 0.026 | |||||||||||

| Salomè 2022 | Couples to NICU babies | During NICU, 1 year post NICU discharge | IES-R score ≥ 33 | Parents N = 40, mothers n = 20 (55%), and 4 (20%) fathers | Multivariable regression | Factors (At 1 yr post discharge) | R | B | t | P | ||||

| Maternal Factors | ||||||||||||||

| Maternal PSS:NICU total score | 0 .37 | 0.612 | 3.28 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||

|

Maternal social functioning Subscale of Short form health survey (SF-36) |

0.40 | -0.62 | -3.43 | < 0 .01 | ||||||||||

| Paternal Factors | ||||||||||||||

| Maternal PSS:NICU total score | 0.52 | 0.72 | 4.40 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Paternal self-rating depression | 0.49 | 0.70 | 4.13 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||

| Sharp 2020 | Mothers to Term & preterm infants | 1-4 months after birth | PCL-5 > 33 | Mothers N =77, n = 18 (23.4%) | Linear regression | Factors (1-4 months) | β | SE | 95%CI | P | ||||

| Time since birth | -0.01 | 0.08 | -0.17, 0.16 | 0.937 | ||||||||||

| Duration of NICU stay | 0.13 | 0.08 | − 0.02, 0.29 | 0.093 | ||||||||||

| Prior trauma | 2.37 | 1.41 | − 0.45, 5.19 | 0.098 | ||||||||||

| Parental Stressor Scale (PSS) total | 0.65 | 0.09 | 0.11, 1.18 | 0.020 | ||||||||||

| Traumatic childbirth | 2.44 | 4.58 | -6.72, 11.60 | 0.596 | ||||||||||

| Shaw 2009 | Parents to term and preterm infants GA 27-41 wks | 2-4 wks after NICU admission and at 4 months after birth | SARQ > 38 |

Baseline mothers N = 25, n = 14 (54.5%) vs fathers n = 13, (0%) At 4 months mothers N = 11, 6 (55%) at risk, PTSD 1 (9%) PTSD, fathers at risk N= 6, 4 (67%), PTSD 2 (33%) |

Correlation | Factors (4 months after birth) | r | P value | ||||||

| GA | 0.20 | NS | ||||||||||||

| BW | 0.03 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Apgar grade at 1 minute | 0.29 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Apgar grade at 10 minutes | 0.22 | NS | ||||||||||||

| Length of stay in hospital | -0.40 | NS | ||||||||||||

|

PSS: NICU: Infant behaviour and appearance Parental role-alteration Sights and sounds Staff relationships Total |

0.09 | NS | ||||||||||||

| 0.35 | NS | |||||||||||||

| 0.52 | < 0.05 | |||||||||||||

| 0.13 | NS | |||||||||||||

| 0.42 | NS | |||||||||||||

| Acute stress disorder (ASD) | 0.54 | < 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) baseline | 0.54 | < 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| BDI at follow-up | 0.79 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

|

SCL90–R: Symptom Checklist, Revised: Somatization Anxiety Depression Interpersonal sensitivity Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Paranoid Ideation Phobia Hostility Pychoticism Global Severity Index |

0.41 | NS | ||||||||||||

| 0.56 | < 0.05 | |||||||||||||

| 0.60 | < 0.05 | |||||||||||||

| 0.53 | < 0.05 | |||||||||||||

| 0.50 | NS | |||||||||||||

| 0.62 | < 0.05 | |||||||||||||

| 0.70 | < 0.01 | |||||||||||||

| 0.46 | NS | |||||||||||||

| 0.40 | NS | |||||||||||||

| 0.68 | < 0.01 | |||||||||||||

| Parent sex OR 0.60, 95%CI 0.08, 4.76 | ||||||||||||||

| Vinall 2018 | Mothers to infants born < 37 wks GA | At NICU discharge | PTSS checklist for DSM-5 | Mothers = 36, n = 2 (6%) | Multivariable linear regression | Factors (NICU discharge) | β | 95%CI | P value | |||||

| GA | 0.30 | −0.05, 0.64 | NR | |||||||||||

| Sex of baby | 0.10 | −0.16, 0.36 | NR | |||||||||||

| Illness severity – medical chart | 0.13 | −0.12, 0.37 | NR | |||||||||||

| No. invasive procedures | 0.40 | 0.003, 0.801 | NR | |||||||||||

| Length of stay | 0.05 | −0.41, 0.51 | NR | |||||||||||

| Mother’s age | −0.159 | −0.42, 0.09 | NR | |||||||||||

| Mother’s years of education | −0.27 | −0.52, −0.02 | NR | |||||||||||

| Mothers memory of pain | 0.21 | −0.02, 0.44 | NR | |||||||||||

| Williams 2021 | Mothers to NICU infants born < 28 to > 37 wks | During first month of NICU stay | IES-R ≥ 33 | Mothers = 119, n = 66 (55%) | Correlations | Factors (During NICU) | r | P value | ||||||

| Subjective infant health | 0.60 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Chart infant health - SNAPPE II | 0.35 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Apgar at 1 minute | −0.20 | < 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Apgar at 5 min | −0.25 | < 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Worry about infant death | 0.17 | NS | ||||||||||||

Abbreviations: 95%CI 95% Confidence Interval, aOR adjusted odd ratio, BW Birth weight, CA corrected age, CES-D Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression, GA Gestational age, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, IES-R Impact of Event Scale-Revised, Italics Data calculated, mPPQ Modified Perinatal Post-traumatic stress disorder Questionnaire, NBRS Neurobiologic Risk Score, NICU Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, NR Not reported, NS Not significant, OR Odd ratio, MPI Maudsley Personality Inventory, PLC-5 Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition, PPQ Perinatal Post-traumatic stress disorder Questionnaire, PSS Perceived Stress Scale, r Correlation coefficient, Factors Risk factors, HMD Severe neonatal morbidity referred to hyaline membrane disease, IVH grade 3 and 4, periventricular leukomalacia, BPD severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, sepsis, meningitis, NEC necrotizing, enterocolitis, hyperbilirubinemia over the 90th percentile, ROP retinopathy of prematurity, symptomatic patent ductus arteriosus requiring surgery, SNAPPE-II Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology-Perinatal Extension-II, TEA Term Equivalent Age, Wks Weeks

aStudies included in both posttraumatic stress and anxiety: Garfield 2015 [27], Greene 2015 & 2019 [28, 29], Holditch-Davis 2009 [31], Lotterman 2018 [45], Misund 2013 & 2014 [36, 37], Moreyra 2021 [47], Pisoni 2020 [49]

Table 3.

Mapping of posttraumatic (PTS) factors

| Not statistically significant | FACTORS | Statistically significant | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent demographic factors | |||||||||||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Garfield 2015 [27] n = 113 |

Greene 2019 [29] n = 69 |

Kim 2015 [50] n = 120 |

Lefkowitz 2010 [34] n = 130 |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

Rodriguez 2020 [40] n = 146 |

Vinall 2018 [43] n = 36 |

age |

n = 29 |

||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Garfield 2015 [27] n = 113 |

Kim 2015 [50] n = 120 |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

education |

Clark 2021 [25] n = 67 |

Rodriguez 2020 [40] n = 146 |

Vinall 2018 [43] n = 36 |

||||||||

|

Anchan 2021 [22] n = 106 |

Clark 2021 [25] n = 67 |

Lefkowitz 2010 [34] n = 130 |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

Pace 2020 [39] n = 105 |

sex |

Moreyra 2021 [47] n = 150 |

Naeem 2019 [38] n = 160 |

||||||||

|

Lefkowitz 2010 [34] n = 130 |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

Moreyra 2021 [47] n = 150 |

ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| parents ‘area deprivation |

Greene 2019 [29] n = 69 |

||||||||||||||

|

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

housing and access to transport | ||||||||||||||

| family income |

Clark 2021 [25] n = 67 |

||||||||||||||

|

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

employment status |

Naeem 2019 [38] n = 160 |

|||||||||||||

|

Malin 2020 [46] n = 164 |

single parent | ||||||||||||||

|

Pace2020 [39] n = 105 |

family social risk | ||||||||||||||

| Pregnancy and birth factors | |||||||||||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

parity |

Greene 2015 [28] n = 69 |

Kim 2015 [33] n = 120 |

||||||||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Kim 2015 [50] n = 120 |

Pace 2020 [39] n = 105 |

multiple pregnancy | ||||||||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

mode of birth |

n = 29 |

|||||||||||||

| preeclampsia |

n = 29 |

||||||||||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

threatened preterm labour | ||||||||||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

In vitro fertilization | ||||||||||||||

|

Sharp 2021 [42] n = 77 |

traumatic childbirth | ||||||||||||||

| Infant demographic factors | |||||||||||||||

|

Anchan 2021 [22] n = 106 |

Kim 2015 [50] n = 120 |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

Vinall 2018 [43] n = 36 |

gestational age |

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Rodriguez 2020 [40] n = 146 |

||||||||

|

Eutrope 2014 [26] n = 100 |

Rodriguez 2020 [40] n = 146 |

birth weight |

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Greene 2019 [29] n = 69 |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

||||||||||

|

Williams 2021 [44] n = 119 |

Apgar score |

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Kim 2015 [50] n = 120 |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

|||||||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Vinall 2018 [43] n = 36 |

sex | |||||||||||||

|

Rodriguez 2020 [40] n = 146 |

age | ||||||||||||||

| Infant health and care factors | |||||||||||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Clark 2021 [25] n = 67 |

Garfield 2015 [27] n = 113 |

Lefkowitz 2010 [34] n = 130 |

Malin 2020 [46] n = 164 |

clinicians’ perception of infant health |

Eutrope 2014 [26] n = 100 |

Pisoni 2020 [49] n = 29 |

Rodriguez 2020 [40] n = 146 |

Williams 2021 [44] n = 119 |

||||||

| parents’ perception of infant health |

Anchan 2021 [22] n = 106 |

Clark 2021 [25] n = 67 |

Lotterman 2018 [45] n = 91 |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

Williams 2021 [44] n = 119 |

||||||||||

|

Lotterman 2018 [45] n = 91 |

mother-infant contact | ||||||||||||||

|

Lotterman 2018 [45] n = 91 |

number of NNU visits | ||||||||||||||

|

Pisoni 2020 [49] n = 29 |

mother-infant relationship | ||||||||||||||

|

Lotterman 2018 [45] n = 91 |

mother-nurse relationships | ||||||||||||||

|

Rodriguez 2020 [40] n = 146 |

Sharp 2021 [41] n = 77 |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

Vinall 2018 [43] n = 36 |

length of stay in NNU |

Lefkowitz 2010 [34] n = 130 |

Lotterman 2018 [45] n = 91 |

|||||||||

| intraventricular haemorrhage |

n = 29 |

||||||||||||||

| ventilation support |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

||||||||||||||

| severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

||||||||||||||

| vasopressors support |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

||||||||||||||

|

Clark 2021 [25] n = 67 |

number of invasive procedures |

Vinall 2018 [45] n = 36 |

|||||||||||||

|

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy | ||||||||||||||

|

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

palliative care consultation | ||||||||||||||

|

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

seizures | ||||||||||||||

|

Pisoni 2020 [49] n = 29 |

infant’s general development | ||||||||||||||

|

Kim 2015 [50] n = 120 |

rehospitalisation or emergency visits | ||||||||||||||

| Parental history of mental health and trauma factors | |||||||||||||||

| history of mental health problems |

Anchan 2021 [22] n = 106 |

Lotterman 2018 [45] n = 91 |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

||||||||||||

| family history of depression / mental health |

Lefkowitz 2010 [34] n = 130 |

Malin 2022 [46] n = 245 |

|||||||||||||

|

Sharp 2021 [41] n = 77 |

previous traumatic events |

n = 69 |

Naeem 2019 [38] n = 160 |

||||||||||||

|

Sharp 2021 [41] n = 77 |

traumatic childbirth | ||||||||||||||

| Parental postnatal mental health factors | |||||||||||||||

| postnatal depression |

Anchan 2021 [22] n = 106 |

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Eutrope 2014 [26] n = 100 |

Holditch-Davis 2009 [31] n = 117 |

Jubinville 2012 [32] n = 40 |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

Salomè 2022 [48] N = 40 |

||||||||

| postnatal anxiety |

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

Eutrope 2014 [26] n = 100 |

Garfield 2015 [27] n = 113 |

Holditch-Davis 2009 [31] n = 117 |

Moreyra 2021 [47] n = 150 |

||||||||||

|

Lotterman 2018 [45] n = 91 |

early PTS symptoms |

Anchan 2021 [22] n = 106 |

Lefkowitz 2010 [34] n = 130 |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

|||||||||||

| other mental health symptoms |

Chang 2016 [24] n = 102 |

Eutrope 2014 [26] n = 100 |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

||||||||||||

| Parent stress, coping and support factors | |||||||||||||||

|

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

parental stressor scale total score |

Sharp 2021 [41] n = 77 |

Salomè 2022 [48] N = 40 |

||||||||||||

|

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

stress related to infant’s appearance |

Holditch-Davis [31] 2009 n = 117 |

|||||||||||||

| stress related to NNU sights and sounds |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

||||||||||||||

|

Anchan 2021 [22] n = 106 |

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

stress related to role alteration |

Holditch-Davis [31] 2009 n = 117 |

||||||||||||

|

Shaw 2009 [42] n = 38 |

stress relating to staff relationships | ||||||||||||||

| concurrent stressors |

Lefkowitz 2010 [34] n = 130 |

||||||||||||||

|

Lotterman 2018 [45] n = 91 |

forward-focused coping style | ||||||||||||||

| maternal optimism |

Lotterman 2018 [45] n = 91 |

||||||||||||||

|

Williams 2021 [44] n = 119 |

worry about infant’s death | ||||||||||||||

| social support |

Eutrope 2014 [26] n = 100 |

Salomè 2022 [48] n = 40 |

|||||||||||||

|

Brunson 2021 [23] n = 50 |

psychological support | ||||||||||||||

| Other factors | |||||||||||||||

|

Anchan 2021 [22] n = 106 |

military geographic separation | ||||||||||||||

|

Anchan 2021 [22] n = 106 |

active military service | ||||||||||||||

| spiritual activity |

Hawthorne 2016 [30] n = 165 |

||||||||||||||

|

Hawthorne 2016 [30] n = 165 |

religious activities | ||||||||||||||

The association between parental age and PTS symptoms was explored in nine studies, published in ten records [23, 27, 29, 33, 34, 36, 37, 40, 43, 46]. Older mothers had significantly higher PTS scores at two weeks post NNU admission in one study of only 29 mothers, reported in two records [36, 37]. In the remaining studies there was no significant association between parental age and PTS symptoms. Seven studies [23, 25, 27, 33, 40, 43, 46] explored the association between parental education and PTS symptoms. Lower education was associated with more PTS symptoms in three studies [25, 40, 43] and consistent with this finding, one study [43] found mothers with more years of education had fewer PTS symptoms at discharge. Similarly, in another study [40], mothers who had a lower education level accounted for significantly more cases of PTS at 6–36 months after birth. Additionally, among bereaved mothers [25], higher education level was associated with fewer PTS symptoms even three to five years after the baby’s death. The remaining four studies found no association between parental education and PTS symptoms. The association between sex of parent and PTS symptoms was explored in seven studies [22, 25, 34, 38, 39, 42, 47]. Three studies [34, 38, 39] provided data at multiple time points. Two studies [38, 47] found PTS symptoms were significantly more prevalent in mothers than fathers while their babies were still in NNU and a month later [38]. Evidence from the remaining five studies showed no association between sex of parent and PTS symptoms. Three studies [34, 46, 47] explored the association between parental ethnicity and PTS symptoms, and none found any association during NNU stay [34, 47] or at three months post NNU discharge [46]. However, in one of the studies [34], only 28% of participants were from minority backgrounds. The association between parents’ area deprivation and PTS was explored in one study [29], and mothers residing in poorer neighbourhoods had lower PTS scores at birth than those residing in more privileged neighbourhoods, but this association disappeared at one year. Housing and access to transport were not associated with PTS symptoms at three months post NNU discharge in one study [46]. In bereaved parents [25], a lower family income for fathers, but not for mothers, was significantly associated with more PTS symptoms at three months to five years after the baby’s death. Two studies [38, 46] explored the association between employment status and PTS symptoms. One study [46] found employment status was not associated with PTS symptoms after birth, yet the other study [38] found PTS symptoms were significantly greater among employed mothers and mothers with unemployed partners one month after the birth [38]. One study [35] found no significant association between being a single parent and PTS symptoms three months after NNU discharge. One study [39] explored family social risk, a composite of family structure, education, occupation, employment, language spoken and maternal age, and found no association with PTS symptoms in parents of very preterm infants at 12 and 24 months corrected age.

2) Pregnancy and birth factors (Seven factors: parity, multiple pregnancy, mode of birth, pre-eclampsia, threatened preterm labour, in-vitro fertilisation, traumatic childbirth)