Abstract

Background: Plant-based diets are not inherently healthy. Similar to omnivorous diets, they may contain excessive amounts of sugar, sodium, and saturated fats, or lack diversity. Moreover, vegans might be at risk of inadequate intake of certain vitamins and minerals commonly found in foods that they avoid. We developed the VEGANScreener, a tool designed to assess the diet quality of vegans in Europe. Methods: Our approach combined best practices in developing diet quality metrics with scale development approaches and involved the following: (a) narrative literature synthesis, (b) evidence evaluation by an international panel of experts, and (c) translation of evidence into a diet screener. We employed a modified Delphi technique to gather opinions from an international expert panel. Results: Twenty-five experts in the fields of nutrition, epidemiology, preventive medicine, and diet assessment participated in the first round, and nineteen participated in the subsequent round. Initially, these experts provided feedback on a pool of 38 proposed items from the literature review. Consequently, 35 revised items, with 17 having multiple versions, were suggested for further consideration. In the second round, 29 items were retained, and any residual issues were addressed in the final consensus meeting. The ultimate screener draft encompassed 29 questions, with 17 focusing on foods and nutrients to promote, and 12 addressing foods and nutrients to limit. The screener contained 24 food-based and 5 nutrient-based questions. Conclusions: We elucidated the development process of the VEGANScreener, a novel diet quality screener for vegans. Future endeavors involve contrasting the VEGANScreener against benchmark diet assessment methodologies and nutritional biomarkers and testing its acceptance. Once validated, this instrument holds potential for deployment as a self-assessment application for vegans and as a preliminary dietary screening and counseling tool in healthcare settings.

Keywords: diet screener, vegan diet, diet assessment, diet quality, screener development, Delphi method

1. Introduction

Veganism [1,2], which encompasses a philosophy of abstaining from the use of foods, beverages, and non-dietary products derived from animals, has seen a rising trend in Europe, particularly among younger and highly educated populations [3,4]. From a dietary perspective, vegans avoid consuming meat, fish, eggs, dairy products, animal fats (e.g., beef tallow and pork lard), and other substances of animal origin [5]. The shift towards veganism is driven by a myriad of motivations, including concerns for animal welfare, social justice issues, climate change implications, individual health, and personal food and taste preferences [6,7]. This shift is mirrored by the rapid expansion of vegan food markets in Europe, indicating a growing demand for vegan foods [8]. A recent Euromonitor’s Product Claims survey [9] showed a steep rise in vegan claims on processed foods, including processed cheese, meat substitutes, pastries, pizza, ice cream, lollipops, gums, jellies, and sauces in 2020–2021. While official surveillance data on the number of vegans across Europe are lacking, available evidence suggests prevalence rates ranging from 0.1% in Spain [10] and 1% in the Czech Republic [11] to 1.4% in Austria, 2–3% in Belgium [12], and 1.3–4% in Germany [13]. In the 2021 Euromonitor’s Lifestyle Survey [14], 3.4% Europeans stated adherence to a vegan diet. This trend is expected to continue growing due to the increasing public awareness of animal food production processes [7], food-related climate change [15,16], and the inclusion of plant-based and sustainable diets in national dietary guidelines [17]. Vegan diets are associated with a higher intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes and seeds, dietary fiber, phytochemicals, and a range of vitamins and minerals, and have a lower glycemic load compared to omnivorous diets [18,19]. They are also associated with a range of positive health outcomes, including lower risks of all-cause mortality and coronary heart disease; a reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and apolipoprotein B (apoB) levels; and improved glycemic control, beneficial gut microbiota shift, and greater weight loss [20,21,22,23,24,25]. A recent study found a higher submaximal endurance and oxygen consumption during exercise among vegans [26]. However, vegan diets may be deficient in some key nutrients, primarily vitamins, including riboflavin, niacin, B12, and D; minerals such as iodine, zinc, calcium, iron, and selenium; polyunsaturated fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA); and the amino acid lysine [18,27,28,29]. In addition, vegans may be at a higher risk of bone fracture [20], potentially due to inadequate calcium and vitamin D, of iodine overconsumption in case of frequent consumption of seaweed/kelp [30], and of hemorrhagic stroke, potentially due to a very low intake of saturated fats [31]. While research on the health effects of “healthy” vs. “less healthy/unhealthy” vegan diet patterns is still sparse, studies identified several types of specific diet patterns among vegans [32,33]. Consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and the energy contribution from UPFs was higher among vegans compared to omnivores [34]. Among vegans, both healthy (h-PDI) and unhealthy (u-PDI) plant-based diet indices were higher compared to omnivores, pesco-vegetarians, and vegetarians [34], providing further evidence of heterogeneity of vegan diets. Consumption of some plant-based foods, such as white potatoes, refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages, sweets and desserts, and salty snacks was associated with higher risks of major chronic diseases and mortality among non-meat eaters [35,36,37].

New vegans may be especially prone to having unhealthier diet patterns characterized by a higher consumption of UPFs [34], some micronutrient deficiencies, and inadequate nutrient intakes; these are often young people who embrace veganism [38,39,40] as a way of life without sufficient knowledge of healthy eating and the potential risks of prolonged inadequate nutrient intakes. They may also have misconceptions regarding fortified foods (e.g., avoiding use of iodine-fortified salt) or rely on ultra-processed products containing excessive amounts of sodium, added sugar, saturated fats (e.g., savory or sugary snacks, and coconut oil-based products), and additives [34,41,42]. Another source of variation in diet quality might stem from the motivation to become vegan in the first place. At least two subtypes of vegans [43] have been described in vegan subculture: “holistic vegans”, who primarily focus on political and ethical issues related to use of animal products beyond personal diet; and “health vegans”, whose focus is primarily on physical health and longevity. Having evidence-based, easily accessible, and quick-to-use tools for (self-)evaluating vegan diet intakes can help assess diet quality and guide dietary choices in this rapidly growing, potentially nutritionally vulnerable population.

Diet quality is a multidimensional construct developed in nutritional epidemiology to evaluate dietary patterns and their associations with the health outcomes or effectiveness of dietary interventions [44,45]. It includes four dimensions: adequacy, balance, moderation, and variety (of healthy dietary components) [46]. Some of the important features of a high-quality diet are that it provides nutrient adequacy, limits the risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and is environmentally sustainable [47]. Diet quality in a population is typically described in the form of evidence-based dietary guidelines and measured by diet quality metrics, such as diet indices or scores. Diet screeners are short-form diet assessment tools [48] aimed at the rapid assessment of overall diets (e.g., rPDQS [49]) or their components (e.g., a fruit and vegetable screener [50]). They typically consist of indicators that distinguish between low and high intakes of foods or nutrients of interest and rank individuals according to frequency of intakes, but they are not intended to estimate the absolute intakes of nutrients or foods [51]. For an indicator to be useful, it should focus on dietary components that are commonly consumed in a population (e.g., sugar-sweetened beverages/SSBs are commonly consumed in Europe) with some degree of between-person variation in intakes (e.g., some individuals frequently consume SSBs, while others do so more rarely or not at all) [51], and that these dietary components represent either important sources of nutrients in question (e.g., SSBs are an important source of added sugar among Europeans) or that are associated with NCD risk (e.g., SSBs are associated with a higher risk of adverse cardiometabolic outcomes).

The VEGANScreener project [52] is a JPI HDHL ERA-NET-funded initiative involving five scientific partners from European countries (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Spain, and Germany), with additional collaborators from the U.S. and Switzerland. Its primary objective is to develop and evaluate a diet quality screener for European vegans. This tool aims to be straightforward for both vegans and non-dietitian/non-nutritionist healthcare providers to use and interpret. Its potential applications include estimating the overall diet quality of vegans, identifying potential areas for dietary enhancement, assisting vegans and their health advisors in setting dietary goals, and monitoring vegan diet quality at both individual- and population-levels over time. This methodological manuscript describes the process for developing the VEGANScreener, a brief tool for assessing diet quality among European vegans.

2. Methods

2.1. Approach to Diet Quality-Screener Development

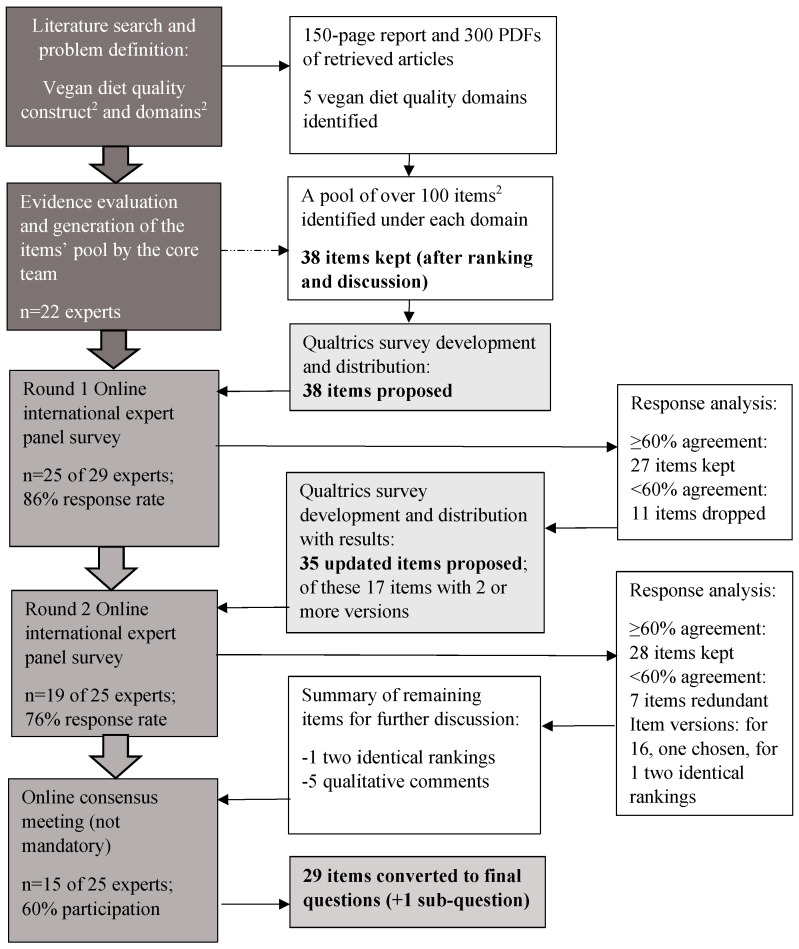

To develop the VEGANScreener, we combined approaches from diet quality metrics development with measurement scale methods in behavioral and health sciences. Our final approach, in brief, consisted of three distinct stages: (a) diet and health narrative literature search and synthesis, (b) evaluation of evidence by a group of international experts, and (c) translation of evidence into a measurement tool within pre-identified domains of the construct of interest. Diet quality metrics, such as indices and scores, are a priori defined measures developed on the basis of the current knowledge on diet-disease relationships [53]. To measure a complex construct of diet quality, we also relied on the best practices for development of scales as health and social research tools [54] that involve the development of a pool of items within a number of predefined domains by a team of experts [55], and their transformation into measurable indicators. To formalize the expert opinion collection procedure, we adopted a modified Delphi technique [56,57], a formal process for gaining consensus through controlled feedback from a group of experts on a subject. This technique, which was originally developed in the 1950s and is increasingly used in health research, is especially suitable in situations where there is limited evidence on a topic, when experts are geographically dispersed, when there is a need to mitigate the risks associated with groupthink, and where a clear and documented methodology for achieving consensus is required. It is an iterative process traditionally consisting of a large number of feedback loops, while modified Delphi process versions are more efficient, with only two to three rounds of voting to the initially proposed pool of items [58]. In our study, the modified Delphi process consisted of an item-generation phase, two rounds of anonymized expert-feedback collection, and an online “face-to-face” consensus group meeting where remaining issues were discussed and resolved. For practical reasons (experts operating in different time zones), participation at the final meeting was not mandatory. Figure 1 presents a visual overview of the screener development process.

Figure 1.

The VEGANScreener development process flow diagram.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Between April and September 2022, our project team collected and synthesized evidence on associations of plant-based and vegan diets with nutrient intake adequacy, non-communicable diseases and planetary health, diversity of vegan diet patterns, nutrient composition of novel vegan products, and metabolomic profile of vegans. We also collected data on currently existing plant-based and vegan diet guidelines, metrics, and diet assessment tools and identified literature gaps. Finally, we reviewed the existing approaches to diet screener development. Our findings were summarized in a comprehensive report with a database of over 300 retrieved articles and analyses of our existing data on vegans from Germany and the Czech Republic. The Delphi process (Figure 2) consisted of two stages: during stage 1, in October 2022, a “core team” of 22 project partners and collaborators from seven countries (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, and the U.S.), consisting of nutrition scientists, clinicians, and epidemiologists with expertise in nutritional epidemiology and dietary assessment tools, reviewed the evidence. A number of principles were agreed upon a priori:

-

-

Items should be considered for inclusion based on available evidence on their (a) associations with nutrient adequacy and/or health outcomes, (b) frequency of consumption, and (c) between-person variation in intakes [51];

-

-

The screener should include no more than 30 questions, and these questions should ideally be food group-based. However, given that the nutritional needs of vegans cannot be met without the addition of supplements/fortified foods to their diet, we agreed that questions on the use of supplements or fortified foods could be nutrient-based;

-

-

Food group-intake questions should include a frequency-based answer scheme and some indication of portion size [51];

-

-

Items receiving less than 60% agreement to keep/keep with modifications in the first voting round will be dropped in their original form; any qualitative feedback (i.e., panel comments in free text form) will be carefully reviewed with a possibility for reintroducing the item in a different form depending on presented arguments.

-

-

Items receiving less than 60% agreement to keep (i.e., 40% or more agreement on redundancy) in the second round will be deemed redundant and will be dropped.

-

-

Qualitative feedback in both rounds will be carefully evaluated and incorporated whenever possible.

-

-

Any remaining issues will be discussed at the consensus meeting.

-

-

The screener should include a balance of healthy and unhealthy food group-based questions and should also include a necessary minimum of nutrient-based questions relevant for vegans.

Figure 2.

Summary flow of the modified Delphi method process 1. (1 Adapted from Figure 5 in Taylor et al. [57]. 2 Construct, an abstraction representing a phenomenon that is not directly measurable; domain, a subcategory or dimension of a construct; item, a measurable indicator formulated as a question or a statement).

Based on the narrative literature review, the team coordinated by the lead author identified five domains of diet quality: (1) foods/food groups associated with a lower NCD risk, (2) foods/food groups associated with a higher NCD risk, (3) foods/food groups associated with nutrient (in)adequacy in vegans, (4) supplements/fortified foods supplying nutrients otherwise deficient in vegan diets, and (5) other food-related behaviors that may influence vegan diet quality. Then, under each of these domains, core team members proposed individual items. Finally, core team members ranked the proposed items by importance by assigning 0, 1, or 2 points to each of them. The summed-up values were then discussed in a plenary meeting, and the final items’ pool for further review in stage 2 was adopted. In stage 2, 29 experts in nutrition, epidemiology, and preventive medicine, with backgrounds in plant-based diets or diet assessment (including 10 core team members), were invited via email to participate in a month-long evaluative process. This process was segmented into two distinct rounds of feedback utilizing a Qualtrics-based survey [59]. This method ensured the mutual anonymity of the responses, adhering to the Delphi technique’s principles [56,57,58]. Experts were also invited to participate in the wrap-up online meeting where any eventual remaining issues would be discussed and resolved.

During the initial round, the experts were provided with a link to the Qualtrics survey containing the item pool. Simultaneously, they were given the summary of evidence report and the full texts of collected articles that were reviewed in stage 1. The experts were asked to review the proposed pool of items and opt for one of three designated responses: “include”, “exclude”, or “keep with modifications”. In the case of the third option, experts were asked to suggest specific modifications. In addition, experts were given an opportunity to include qualitative feedback about each item. For any item to transition to the subsequent round, it necessitated a consensus of at least 60%. Any qualitative feedback, including comments about the dropped items, was carefully reviewed to ensure all feedback was taken into account. A separate team, not involved in the voting process, appraised these responses, resulting in refined items or, in instances of divergent feedback, the genesis of multiple versions of an item.

In the second round, the experts were provided with a new Qualtrics survey link and summaries of the responses accumulated during the first round. This also included an updated pool of items, with certain items presented in multiple iterations. The experts were then asked to vote on the necessity or redundancy of each item. For those items existing in multiple versions, a ranking criterion was implemented to gauge preference. The voting process also requested experts to consider the comprehensive composition of the screener, ensuring the balanced representation of all relevant food groups and nutrients. Items or their specific versions that garnered an agreement threshold of 60% were marked for retention. Residual concerns, whether they related to ranking ties or feedback from the second round that warranted additional consideration, were taken forward for discussion at the online meeting.

The Delphi process was quasi-anonymous [57]; while panelists knew the names of the participating panel members, there was no interaction among the panel members during the first two rounds, and all panelist responses were anonymized.

2.3. Translation and Pretesting

Once finalized, the screener version in English was translated to Czech, Dutch, German, and Spanish and pretested. Our translation process followed the guidelines from the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) [60]. It included translation to local languages by native speakers in target languages, back-translation by English native speakers, and a comparison of the two versions (the original and the back-translated version in English) to detect any semantic shifts. Any spotted shifts were corrected by a team of reviewers and submitted for another round of translations, back-translations, and revisions until the local version corresponded to the original in English. Local versions of the screener were then pretested for clarity and ease of completion in a small convenience sample of vegans, vegetarians, and omnivores (at minimum, ten individuals for each language version). Qualitative feedback was recorded and shared with the core team for review and discussion. Any agreed changes were made to the master version in English, which was then taken for the next round of translations. The procedure was repeated until all local versions were understandable and corresponded with the master version in English. When completed, local language versions were entered into REDCap [61], a research platform used for building and managing online surveys and databases, suitable for multi-country projects.

3. Results

3.1. Voting Rounds and Feedback

The core team reviewed a pool of over 100 items extracted during the literature search and decided to keep 38 for the expert voting. After consideration of the 38 items by the panel of 25 experts participating in round 1 (25 out of 29, 86% response rate), 27 items received agreement of 60% or more and were kept for the next round, while 11 were dropped. The project team then reviewed and summarized qualitative feedback, and it was used to enhance the “kept items” and to potentially restructure the dropped items. As a result, 35 updated items (of which there were 17 with two or more versions) were proposed for round 2 of expert voting. In total, 19 experts participated in round 2 (19 out of 25, response rate 76%); 28 items received ≥60% agreement and were kept, while 1 was taken forward (due to identical agreement for both versions) to the online consensus meeting for discussion. All qualitative feedback from this round was carefully considered by the project team and incorporated for further consideration. Finally, 15 experts (15 out of 25, 60% participation rate) took part in the online consensus meeting, where remaining dilemmas were resolved, and the items were converted to 29 questions and one sub-question, creating the final screener draft.

3.2. Examples of Qualitative Feedback Incorporation

Special attention was given to qualitative feedback provided by experts and their incorporation for consideration by the panel in the next round. Between the first and the second round, a number of items were reformulated, and some merging of items, as well as splitting of items, took place as well (Table 1). For example, the initial item “intake of vegetables (any, except potato)” was deemed insufficiently specific by experts and received low agreement and a number of modification suggestions; “green vegetables” with country-specific lists was deemed overly complex, and experts called for a single list; and the “fruit and vegetable smoothies” item was dropped with a suggestion from some experts to add vegetable smoothies to the general vegetables item. As a result, in round 2, three items (two with multiple versions) were proposed. The final result of this process was three separate questions on “green vegetables”, “other vegetables”, and “dark orange and red fruits and vegetables”. Table 1 includes several examples of the “evolution” of the initially proposed items into screener questions.

Table 1.

Transformation of initial items into final screener questions: selected examples.

| Proposed Items in Round 1 | Round 1 Voting Whether Items Should Stay In | Proposed Items in Round 2 | Round 2 Voting | Final Screener Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A01. How often do you consume vegetables (excluding potatoes and legumes) A02. Consumption of the following green vegetables: → list of calcium-rich commonly consumed vegetables in each country A04. Consumption of fruit and vegetable smoothies (include only freshly made ones) |

<60% agreement on all items regarding their retention Qualitative feedback for modifications |

A02.1. Consumption of the following green vegetables, fresh or cooked:

vegetables, fresh, cooked, or in smoothie:

A01.2. Other vegetables, such as tomato, cucumber, onion, zucchini, or eggplant—fresh, frozen, canned, cooked, fried (do not include vegetables listed in previous question, white potatoes, or legumes) |

A02.1: 90% agreement to keep A07: 85% agreement to keep A01.2: 84% agreement to keep Qualitative feedback for further improvement |

Q1. The following green vegetables, fresh or cooked; whole, cut, or blended:

|

| A24. Sugar-sweetened beverages such as soft drinks, lemonades or sports drinks |

76% agreement Suggestions for further improvement |

A24.1. Sugar-sweetened beverages such as soft/fizzy drinks, lemonades, sweetened iced tea, flavored plant milk, energy drinks, ginger beer, or sports drinks A24.2. Sugar-sweetened beverages such as soft/fizzy drinks, lemonades, sweetened ice teas, flavored milk alternative, non-100% juice drinks/fruit nectars, energy drinks, ginger beer, or sports drinks A24.3. Sugar-sweetened beverages such as soft/fizzy drinks, lemonades, sweetened ice teas, flavored plant milk/yogurt drink, non 100% juice drinks/nectars, energy drinks, ginger beer, or sports drinks |

A24.1: 88% agreement to keep Qualitative feedback for further improvement |

Q23. Sugar-sweetened beverages such as soft/fizzy drinks, lemonades, sweetened iced tea, flavored plant-based milk, energy drinks, ginger beer, or sports drinks |

| A16. Beans, lentils, chickpeas, soybeans, or peas (excluding green peas and green beans) | 76% agreement Suggestions for further improvement |

A16.1. Beans, string beans, lentils, chickpeas, or peas (excluding green peas and green beans), in stews and salads, excluding their products, such as tofu, tempeh, or hummus A16.2. Beans, string beans, lentils, chickpeas or peas in stews and salads, excluding their products, such as tofu, tempeh, or hummus |

A16.1: 95% agreement to keep Qualitative feedback for further improvement |

Q16. Beans, soybeans lentils, chickpeas, or peas (excluding green peas and green beans) (do NOT include here their products, such as tofu, tempeh, or hummus) |

| A20. Consumption of cheese alternatives such as vegan sliced or grated cheese, feta, mozzarella, or cream cheese | 83% agreement Suggestions for further improvement |

A20.1. Cheese alternative such as sliced or grated vegan cheese (e.g., vegan feta, mozzarella, or cream cheese) A20.2. Cheese alternative, such as vegan sliced or grated cheese (e.g., feta, mozzarella, or cream cheese). Do not include here nut/seed-based vegan cheeses. |

A20.1: 89% agreement to keep Qualitative feedback for further improvement |

Q20. Cheese alternatives containing coconut oil, such as sliced, solid, or grated vegan cheese (e.g., vegan feta, mozzarella, or cream cheese) |

| A32. Do you consume seaweed and/or use iodized salt in food preparation and/or an iodine supplement (for Czech Republic, iodine-rich mineral water) | Accepted (over 80% agreement) Suggestions for further improvement |

A32.1. Do you use iodized salt in food preparation, use an iodine supplement or consume seaweed to supplement for iodine intake (for Czech Republic also, iodine-rich mineral water) A32.2. Do you consume seaweed to supplement for iodine intake and/or use iodized salt in food preparation and/or an iodine supplement (for Czech Republic, also iodine-rich mineral water) A32.3 Do you supplement iodine (e.g., seaweed, iodized salt, iodine supplement, and Cz/iodine-rich water) |

A32.1: 82% agreement to keep Qualitative feedback for further improvement |

Q27. Do you regularly use iodized salt in food preparation, use an iodine supplement (either individually or as a part of multimineral supplement) or consume seaweed to supplement for iodine intake (for Czech Republic, also iodine-rich mineral water) |

3.3. Examples of Changes Made during Translation and Pretesting

Between 10 and 72 respondents provided feedback on each language version of the questionnaire. Overall, participants found the screener straightforward and easy to complete. In some cases, respondents were unsure whether certain foods should be included in the response. In such cases, their comments were recorded and discussed by the core team, who gave potential solutions. For example, some respondents were unsure whether chickpea or red lentil flour products (e.g., red lentil pasta) should be reported under the question on legumes. As a result, this question was slightly reformulated to include products made of legume flour. Another example was editing the list of commonly consumed calcium-rich, oxalate-low vegetables in countries; while in some countries, bok choy was commonly consumed, it was not the case across all countries. At the same time respondents suggested adding other locally consumed green leafy vegetables such as endive or borage. Finally, respondents noted that the sub-question on the salt content of vegan meat alternatives could be difficult to answer with only “yes” and “no” options, as some respondents might not know whether they were choosing it or not. Given that our team’s intention was to capture those who take care to choose products not overly high in sodium, we added a response “do not know” to the answer scheme, assuming that those who do not intentionally choose low-sodium products from the meat alternatives category are most likely consuming sodium-rich ones [62,63,64].

3.4. Final Screener Draft for Evaluation and Testing

The final screener draft (Table 2) consisted of 29 questions and one sub-question; of these, 17 questions focus on intake of food groups and nutrients whose intake should be encouraged (e.g., wholegrain bread, bun, roll, crisp, or crackers) and 12 (+one sub-question) on intake of food groups that should be limited (e.g., white bread, bun or roll); 24 were food-based (e.g., sugar-sweetened beverages), and 5 were nutrient/supplement-based (e.g., vitamin B12 supplement). The rationale for including each screener question in its final form is presented in Table 3. One question could cover one or more reasons for inclusion; for example, nuts and seeds are good sources of many micronutrients important for vegans, as well as of amino-acids and PUFAs. Twenty-five food group intake questions had a frequency-based format including nine possible answer options (from “never” to “3 or more times a day”) and an example of one serving (e.g., one cup), four nutrient-based were binary (yes/no), and one sub-question had a “yes/no/don’t know” answer format.

Table 2.

VEGANScreener—final English version.

| Over the Past Month, How Often Did You, on Average, Consume at Least One Serving of Foods or Beverages from the Following Food Groups: | Never | Rarely/ 1×/Month |

2–3×/ Month |

1×/ Week |

2–3×/ Week |

4–6×/ Week |

1×/ Day |

2×/ day |

≥3 Times /Day |

1 Serving Example | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | The following * green vegetables, fresh or cooked; whole, cut, or blended: | 1 handful cooked/ 2 handfuls fresh vegetables |

||||||||||||

| Broccoli Kale Bok choy Arugula |

Chinese cabbage Green cabbage Savoy cabbage |

Brussel sprout Endive Artichoke |

||||||||||||

| Q2 | The following * dark orange and red fruits and vegetables, fresh or cooked; whole, cut, or blended: | 2 handfuls fresh/1 handful cooked, 1 medium piece | ||||||||||||

| Carrot Apricot Mango Cantaloupe Orange sweet potato |

Hokkaido pumpkin Butternut squash Dark orange pumpkin |

Red bell pepper Red grapefruit Kaki Chanterelle mushroom Milkcap mushroom |

||||||||||||

| Q3 | Other vegetables, such as tomato, cucumber, onion, zucchini, or eggplant—fresh, frozen, canned, cooked, fried (do not include potatoes, legumes, or vegetables listed in previous questions) | 1 medium tomato, 1 handful cooked/2 handfuls fresh vegetables | ||||||||||||

| Q4 | Other fruits, such as apples, berries, melons, or oranges—whole or cut (do NOT include fruit juices and smoothies) | 1 medium apple/orange, 1–2 slices melon, 1 handful berries | ||||||||||||

| Q5 | White/yellow potatoes | 2-3 medium potatoes | ||||||||||||

| Q6 | White bread, white bun, or white roll | 2 slices of bread, 1 bun | ||||||||||||

| Q7 | White rice, pasta/noodles, instant couscous, instant polenta, or instant breakfast cereals (e.g., crisps, flakes, and crunch) | 1 cup of cooked rice, pasta, couscous, polenta or instant breakfast cereals | ||||||||||||

| Q8 | Wholegrain bread, bun, or roll, wholegrain crackers or crispbread | 2 slices of bread, 1 roll, 2–3 crackers/crispbreads |

||||||||||||

| Q9 | Other whole grains (e.g., brown rice; brown pasta; grain kernels such as spelt, wheat, oats or barley, porridge, unsweetened wholegrain muesli, wholegrain couscous, wholegrain bulgur, quinoa, buckwheat, or amaranth) | 1 cup cooked rice, pasta, porridge, kernels, couscous, bulgur, quinoa, buckwheat, amaranth, or muesli | ||||||||||||

| Q10 | Nuts and seeds, such as walnuts, almonds, hazelnuts, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, or flaxseeds | 1 handful of nuts, 1 tablespoon of seeds | ||||||||||||

| Q11 | Nut and seed butters, such as peanut butter or tahini | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||||||

| Q12 | Vegan butter or coconut oil | 1 tablespoon | ||||||||||||

| Q13 | Plant-based oils such as olive, soybean, flaxseed, or rapeseed oil (do NOT include here palm or coconut oil), avocado or olives | 1 tablespoon oil, 1/2 avocado, 5–10 olives | ||||||||||||

| Q14 | EPA/DHA (omega 3)—fortified oils, EPA/DHA (omega 3), supplements or microalgae oil? | 1 tablespoon oil, 1 dose as per packaging instructions. | ||||||||||||

| Q15 | Traditional plant protein sources and derivates like tofu, seitan, natto, tempeh, falafel, hummus, 100% red lentil or chickpea pasta, or soy cubes/granules | ½ small block tofu, seitan, tempeh, 4 falafels;1 cup cooked pasta, 1 small bowl soy granules/cubes, 2–3 tablespoons hummus | ||||||||||||

| Q16 | Beans, soybeans, lentils, chickpeas, or peas (excluding green peas and green beans) (do NOT include here their products, such as tofu, tempeh, or hummus) | 1/2 cup cooked legumes | ||||||||||||

| Q17 | Packaged meat/fish alternatives such as vegan salami, cold cuts, sausages, burger patties, or fish fingers (excluding homemade recipes from raw sources) If 17 = “never”, go to Q18 | 1 palm-sized piece, 1 sausage, 3–4 slices of salami etc. | ||||||||||||

| Q17 a | When you buy these products, do you usually choose products low in salt? | Yes | No | Don’t know | ||||||||||

| Q18 | Calcium-fortified plant-based milks, yogurts (e.g., almond, soy, and oat) or calcium-set tofu | 1 glass of milk, 1 cup yogurt, ½ small block of tofu | ||||||||||||

| Q19 | Cheese alternatives containing coconut oil, such as sliced, solid, or grated vegan cheese (e.g., vegan feta, mozzarella, or cream cheese) |

1 slice of cheese, 1 tablespoon cream cheese or grated cheese | ||||||||||||

| Q20 | Savory snacks, such as crisps/chips or salted crackers | 1 handful | ||||||||||||

| Q21 | Ready-to-eat meals, such as frozen pizza, croquettes, fried foods, spring rolls, dumplings, instant pasta, or instant soup | 1 serving according to the package | ||||||||||||

| Q22 | Vegan sweets and desserts, such as candy, “milk” chocolate, cake, ice cream, or pudding | 1 piece of cake, 4 cookies, 1 handful of candy, 1 rip of chocolate, 1 scoop ice cream, 1 bowl of pudding | ||||||||||||

| Q23 | Sugar-sweetened beverages, such as soft/fizzy drinks, lemonades, sweetened iced tea, flavored plant-based milk, energy drinks, ginger beer, or sports drinks | 1 glass | ||||||||||||

| Q24 | Artificially sweetened beverages, such as diet/zero sugar soft/fizzy drinks, lemonades, energy drinks, “light” beverages, or sports drinks | 1 glass | ||||||||||||

| Q25 | Alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, cocktails, or spirits | 1 can, 1 glass, 1 jigger/shot | ||||||||||||

| Do you regularly use: | Yes | No | ||||||||||||

| Q26 | Supplement for vitamin B12 (either individually or as part of a multivitamin supplement) (e.g., pills, drops, injections, and fortified toothpaste)? | |||||||||||||

| Q27 | Iodized salt in food preparation, use an iodine supplement (either individually or as part of a multimineral supplement) or consume seaweed to supplement for iodine intake (for Czech Republic, also iodine-rich mineral water) | |||||||||||||

| Q28 | Vitamin D supplement (either individually or as part of a multivitamin supplement) during autumn and winter months? | |||||||||||||

| Q29 | Selenium supplement (either individually or as part of a multimineral supplement) or regularly consume Brazil nuts? | |||||||||||||

* These lists may be edited by adding country-specific fruits/vegetables if they are commonly consumed in a country AND if they contain >40 mg Ca/100 g AND have a low oxalate content (due to inhibited Ca absorption).

Table 3.

Rationale for inclusion of each question in the VEGANScreener.

| VEGANScreener Question (Abbreviated Title) * | Rationale for Inclusion and Format |

|---|---|

| Green vegetables | Critical nutrient (calcium) List of vegetables satisfying the following three requirements:

|

| Dark orange and red fruits and vegetables | Beta-carotene intake List of fruits and vegetables satisfying the following three requirements:

|

| Other vegetables | Dietary fiber and micronutrient intake, diverse vegetable intake |

| Other fruits | Dietary fiber and micronutrient intake, diverse fruit intake |

| White/yellow potatoes | High glycemic index, pro-inflammatory |

| White bread, white bun, or white roll | High glycemic index, pro-inflammatory |

| White rice, pasta/noodles, instant couscous, etc. | High glycemic index, pro-inflammatory |

| Wholegrain bread, bun or roll, etc. | Dietary fiber and micronutrient intake |

| Other whole grains | Dietary fiber and micronutrient intake |

| Nuts and seeds | Polyunsaturated fat, plant protein intake and, micronutrient intake |

| Nut and seed butters | Polyunsaturated fat, plant protein intake, and micronutrient intake |

| Vegan butter or coconut oil | Saturated fat content, pro-inflammatory |

| Plant-based oils | Long-chain omega 3 fatty acids intake |

| EPA/DHA-fortified oils or supplements | EPA/DHA intake |

| Tofu, seitan, natto, tempeh, etc. | Plant protein intake |

| Beans, soybeans, lentils, chickpeas, or peas | Dietary fiber and plant protein intake |

| Packaged meat/fish alternatives | Saturated fat and sodium content |

| Salt content (sub-question, refers to previous question) | Potentially high sodium content |

| Calcium-fortified plant-based milks, etc. | Calcium and plant protein content |

| Cheese alternatives containing coconut oil | Saturated fat content |

| Savory snacks | Saturated fat and sodium content |

| Ready-to-eat meals | Saturated fat added sugar and/or sodium content |

| Sweets and desserts | Saturated fat and added sugar content |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | Added sugar content |

| Artificially sweetened beverages | Associations with adverse CVD outcomes and possibly cancer |

| Alcoholic beverages | Inhibiting nutrient absorption |

| Use of supplement for vitamin B12 | Critical nutrient for vegans |

| Use of iodized salt, supplement, or seaweed | Critical nutrient for vegans |

| Use of vitamin D supplement | Critical nutrient for vegans |

| Use of selenium supplement | Critical nutrient for vegans |

* Refer to Table 2 for a full list of questions.

3.5. Challenges in Development of the Screener

Ensuring a highly rigorous process of development of the screener, following an a priori defined procedure and basing any decisions on available scientific evidence was our team’s priority at each stage of the process. We identified and followed best-practice steps for tool development described in the scholarly literature, conducted a comprehensive narrative literature review on aspects of vegan diets and health, and invited participation of a diverse group of international experts. During this process, however, we encountered several important challenges. The vegan food market in Europe is growing rapidly, resulting in multiple data gaps regarding the nutrient composition and health effects of these foods. As a result, we found it difficult to classify some of these novel products under traditional food groups; categorize them as “healthy” and “less healthy” food groups; and to formulate them as clear, simple, and understandable screener questions. For example, vegan cheese alternative can be based on legumes (considered “healthy”) or on coconut and shea butter fat (considered “less healthy”). Therefore, when we aimed to measure how often respondents consumed “less healthy” vegan cheese, we formulated it as follows: “cheese alternatives containing coconut oil, such as…”, assuming that respondents would know what type of cheese alternatives they use, which might not always be the case. Another similar problem was related to fortified milk alternatives, as they can be any combination of calcium-fortified/unfortified and “sugar-added”/“no added sugar”. As we aimed to capture only intakes of “healthy” calcium-fortified milk with no added sugar, we formulated the question by emphasizing calcium-fortification and combining milk with other dairy alternatives such as calcium-fortified yoghurt and calcium-set tofu, leaving out mention of sugar, as some experts felt that that would be overly complicated and confusing for participants. The lack of data on long-term effects of some foods was another challenge. As already mentioned, some vegan cheese or vegan butter products are coconut oil- and/or shea butter-based and contain high amounts of saturated fats, making them potentially unhealthy [65]. Some vegan meat alternatives and snacks may also contain excessive amounts of sodium [62,63,64]. Finally, while many of these novel products are classified as ultra-processed foods [34,66], some of which are associated with adverse health outcomes in large studies [67,68], others are not [69].

4. Conclusions

After extensive collaboration and evaluation by experts, we successfully developed the VEGANScreener, a diet quality screener tailored for vegans in Europe. The next steps involve validating the tool against reference diet assessment methods and nutritional biomarkers across different European population groups and settings, with special paid attention to evaluating any variations by gender, age, ethnicity, or motivation for becoming vegan. Its performance and acceptability will also be evaluated among both vegans and healthcare professionals. If deemed valid and well-received, the VEGANScreener could become a straightforward tool for the self-evaluation, monitoring, and enhancement of dietary quality among European vegan individuals and groups. It also holds potential for developing a similar tool for other geographical settings through the application of the process described in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The international expert panel members participating in the Delphi process were as follows, in alphabetical order: Maira Bes-Rastrollo, Leonie-Helen Bogl, Sabri Bromage, Leone Craig, Janet Kyle, Willem De Keyzer, Teresa Fung, Jan Gojda, Markus Keller, Sharon Kirkpatrick, Christian Koeder, Tilman Kühn, Miguel Ángel Martínez-González, Karin Michels, Moursi, Ute Nöthlings, Marga Ocké, Keren Papier, F.J. Armando Perez-Cueto, Joan Sabate, Eva Schernhammer, oec. troph. Sabrina Schlesinger, Maya Vadiveloo, Maria Wakolbinger, Cornelia Weikert, and Walter Willett. The Delphi process was coordinated by Selma Kronsteiner-Gicevic, did not take part in the voting. VEGANScreener Consortium members (in alphabetical order): Maira Bes-Rastrollo, Jan Gojda, Stefaan De Henauw, Markus Keller, Marek Kuzma, and Eva Schernhammer. VEGANScreener project collaborators and scientific partners: Walter Willett—Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health; Leonie-Helen Bogl—Bern University of Applied Sciences; and Willem De Keyzer—HOGENT University of Applied Sciences and Arts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.-G., L.H.B., M.W. and W.W.; funding acquisition, S.K.-G., L.H.B., M.W., M.B.-R., J.G., S.D.H., M.K. (Markus Keller), M.K. (Marek Kuzma) and E.S. (Eva Schernhammer); investigation, S.M., J.D., V.B.-V., E.S. (Eliska Selinger), V.K., A.M.T., T.A., L.C., J.K., C.K., A.O., M.H. and M.C.; methodology, W.D.K., S.S., M.A.M.G., M.B.-R., J.G., S.D.H., M.K. (Markus Keller) and M.K. (Marek Kuzma); supervision, E.S. (Eva Schernhammer); writing—original draft, S.K.-G. and W.D.K.; writing—review and editing, L.H.B., M.W., S.M., J.D., V.B.-V., E.S. (Eliska Selinger), V.K., A.M.T., T.A., L.C., J.K., S.S., C.K., A.O., M.H., W.V.L., M.C., M.A.M.G., W.W., M.B.-R., J.G., S.D.H., M.K. (Markus Keller), M.K. (Marek Kuzma) and E.S. (Eva Schernhammer). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We sought advice from the Medical University of Vienna Ethics Committee, who advised that an online Delphi survey among experts did not require formal ethical approval. All experts were provided with written information about the project and their participation, and they all gave their consent to participate by email. This study does not include experiments on humans or the use of human tissue.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Funding Statement

HDHL-INTIMIC: Standardized measurement, monitoring, and/or biomarkers to study food intake, physical activity, and health (STAMIFY 2021) in 2022-25. The VEGANScreener Study is supported by ERA-Net HDHL-INTIMIC, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No. 727565. The following institutes provide support: the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG (Austria; project no. FO999890542) and the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBWF); the Research Foundation Flanders FWO (Belgium, project no. G0G5121N); the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports (Czech Republic, project no. MSMT-88/2021-29/2 and MSMT-88/2021-29/3); the German Funding Foundation DFG (Germany, project no. 01EA2202); and the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities within the framework of Plan de recuperación, transformación y resiliencia-Next Generation EU (Spain, project no. AC21_2/00015).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.The Vegan Society Definition of Veganism. 2023. [(accessed on 9 September 2023)]. Available online: https://www.vegansociety.com/go-vegan/definition-veganism.

- 2.Greenebaum J. Veganism, Identity and the Quest for Authenticity. Food Cult. Soc. 2012;15:129–144. doi: 10.2752/175174412x13190510222101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gheihman N. Veganism as a lifestyle movement. Sociol. Compass. 2021;15:e12877. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IPSOS . An Exploration into Diets around the World. IPSOS; Paris, France: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hargreaves S.M., Rosenfeld D.L., Moreira A.V.B., Zandonadi R.P. Plant-based and vegetarian diets: An overview and definition of these dietary patterns. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023;62:1109–1121. doi: 10.1007/s00394-023-03086-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghaffari M., Rodrigo P.G.K., Ekinci Y., Pino G. Consumers’ motivations for adopting a vegan diet: A mixed-methods approach. Int. J. Consum Stud. 2022;46:1193–1208. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen M., Busch C., Rodiger M., Hamm U. Motives of consumers following a vegan diet and their attitudes towards animal agriculture. Appetite. 2016;105:643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smart Protein Plant-Based Foods in Europe: How Big is the Market? [(accessed on 15 April 2024)]. Available online: https://smartproteinproject.eu/plant-based-food-sector-report/

- 9.Euromonitor . International’s Product Claims and Positioning System. Euromonitor; London, UK: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantero P.A., Santos C.P.O., Lopez-Ejeda N. Vegetarian diets in Spain: Temporal evolution through national health surveys and their association with healthy lifestyles. Endocrinol. Diab. Nutr. 2023;70:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.endien.2022.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.IPSOS Bezmasou Stravu Preferuje Desetina Mladých. 2019. [(accessed on 5 October 2023)]. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/cs-cz/bezmasou-stravu-preferuje-desetina-mladych.

- 12.iVOX Vleesconsumptie in België Blijft verder Dalen. 2023. [(accessed on 5 October 2023)]. Available online: https://proveg.com/be/vleesconsumptie-in-belgie-blijft-verder-dalen/

- 13.Paslakis G., Richardson C., Nohre M., Brahler E., Holzapfel C., Hilbert A., de Zwaan M. Prevalence and psychopathology of vegetarians and vegans—Results from a representative survey in Germany. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:6840. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63910-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Euromonitor . Voice of the Consumer: Lifestyles Survey 2021. Euromonitor; London, UK: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willett W., Rockstrom J., Loken B., Springmann M., Lang T., Vermeulen S., Garnett T., Tilman D., DeClerck F., Wood A., et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393:447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Ibrahim A.A., Jackson R.T. Healthy eating index versus alternate healthy index in relation to diabetes status and health markers in U.S. adults: NHANES 2007–2010. Nutr. J. 2019;18:26. doi: 10.1186/s12937-019-0450-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klapp A.L., Feil N., Risius A. A Global Analysis of National Dietary Guidelines on Plant-Based Diets and Substitutions for Animal-Based Foods. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022;6:nzac144. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakaloudi D.R., Halloran A., Rippin H.L., Oikonomidou A.C., Dardavesis T.I., Williams J., Wickramasinghe K., Breda J., Chourdakis M. Intake and adequacy of the vegan diet. A systematic review of the evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2021;40:3503–3521. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker H.W., Vadiveloo M.K. Diet quality of vegetarian diets compared with nonvegetarian diets: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2019;77:144–160. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuy067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selinger E., Neuenschwander M., Koller A., Gojda J., Kuhn T., Schwingshackl L., Barbaresko J., Schlesinger S. Evidence of a vegan diet for health benefits and risks—An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational and clinical studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2022;63:9926–9936. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2075311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orlich M.J., Singh P.N., Sabate J., Jaceldo-Siegl K., Fan J., Knutsen S., Beeson W.L., Fraser G.E. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns and Mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:1230–1238. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollakova D., Andreadi A., Pacifici F., Della-Morte D., Lauro D., Tubili C. The Impact of Vegan Diet in the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2021;13:2123. doi: 10.3390/nu13062123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang T., Masedunskas A., Willett W.C., Fontana L. Vegetarian and vegan diets: Benefits and drawbacks. Eur. Heart J. 2023;44:3423–3439. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmer J., Lange B., Frick J.S., Sauer H., Zimmermann K., Schwiertz A., Rusch K., Klosterhalfen S., Enck P. A vegan or vegetarian diet substantially alters the human colonic faecal microbiota. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012;66:53–60. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin P., Zhang C., Du T., Yi S., Yu L., Tian F., Chen W., Zhai Q. Meta-analysis reveals different functional characteristics of human gut Bifidobacteria associated with habitual diet. Food Res. Int. 2023;170:112981. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boutros G.H., Landry-Duval M.A., Garzon M., Karelis A.D. Is a vegan diet detrimental to endurance and muscle strength? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020;74:1550–1555. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0639-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt J.A., Rinaldi S., Ferrari P., Carayol M., Achaintre D., Scalbert A., Cross A.J., Gunter M.J., Fensom G.K., Appleby P.N., et al. Metabolic profiles of male meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians, and vegans from the EPIC-Oxford cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;102:1518–1526. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.111989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang F.L., Wan Y., Yin K.H., Wei Y.G., Wang B.B., Yu X.M., Ni Y., Zheng J.S., Huang T., Song M.Y., et al. Lower Circulating Branched-Chain Amino Acid Concentrations Among Vegetarians are Associated with Changes in Gut Microbial Composition and Function. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019;63:e1900612. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter M., Boeing H., Grunewald-Funk D., Heseker H., Krokes A., Leschik-Bonnet E., Oberritter H., Strohm D., Watzl B. Vegan Diet Position of German Nutrition Society e. V. (GNS) Ernahr. Umsch. 2016;63:M220–M230. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung A.M., Avram A.M., Brenner A.V., Duntas L.H., Ehrenkranz J., Hennessey J.V., Lee S.L., Pearce E.N., Roman S.A., Stagnaro-Green A., et al. Potential risks of excess iodine ingestion and exposure: Statement by the american thyroid association public health committee. Thyroid. 2015;25:145–146. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Key T.J., Papier K., Tong T.Y.N. Plant-based diets and long-term health: Findings from the EPIC-Oxford study. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022;81:190–198. doi: 10.1017/S0029665121003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallagher C.T., Hanley P., Lane K.E. Pattern analysis of vegan eating reveals healthy and unhealthy patterns within the vegan diet. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25:1310–1320. doi: 10.1017/S136898002100197x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haider S., Sima A., Kuhn T., Wakolbinger M. The Association between Vegan Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity—A Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Nutrients. 2023;15:1847. doi: 10.3390/nu15081847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gehring J., Touvier M., Baudry J., Julia C., Buscail C., Srour B., Hercberg S., Peneau S., Kesse-Guyot E., Alles B. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods by Pesco-Vegetarians, Vegetarians, and Vegans: Associations with Duration and Age at Diet Initiation. J. Nutr. 2021;151:120–131. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Satija A., Bhupathiraju S.N., Rimm E.B., Spiegelman D., Chiuve S.E., Borgi L., Willett W.C., Manson J.E., Sun Q., Hu F.B. Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satija A., Bhupathiraju S.N., Spiegelman D., Chiuve S.E., Manson J.E., Willett W., Rexrode K.M., Rimm E.B., Hu F.B. Healthful and Unhealthful Plant-Based Diets and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in U.S. Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70:411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson A.S., Tresserra-Rimbau A., Karavasiloglou N., Jennings A., Cantwell M., Hill C., Perez-Cornago A., Bondonno N.P., Murphy N., Rohrmann S., et al. Association of Healthful Plant-based Diet Adherence With Risk of Mortality and Major Chronic Diseases Among Adults in the UK. JAMA Netw. Open. 2023;6:e234714. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.4714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thiele S., Mensink G.B.M., Beitz R. Determinants of diet quality. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:29–37. doi: 10.1079/Phn2003516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imamura F., Micha R., Khatibzadeh S., Fahimi S., Shi P.L., Powles J., Mozaffarian D., Dis G.B.D.N.C. Dietary quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: A systematic assessment. Lancet Glob. Health. 2015;3:E132–E142. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109x(14)70381-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams E., Vardavoulia A., Lally P., Gardner B. Experiences of initiating and maintaining a vegan diet among young adults: A qualitative study. Appetite. 2023;180:106357. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2022.106357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pointke M., Pawelzik E. Plant-Based Alternative Products: Are They Healthy Alternatives? Micro- and Macronutrients and Nutritional Scoring. Nutrients. 2022;14:601. doi: 10.3390/nu14030601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curtain F., Grafenauer S. Plant-Based Meat Substitutes in the Flexitarian Age: An Audit of Products on Supermarket Shelves. Nutrients. 2019;11:2603. doi: 10.3390/nu11112603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christopher A., Bartkowski J.P., Haverda T. Portraits of Veganism: A Comparative Discourse Analysis of a Second-Order Subculture. Societies. 2018;8:55. doi: 10.3390/soc8030055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alkerwi A. Diet quality concept. Nutrition. 2014;30:613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gil A., Martinez de Victoria E., Olza J. Indicators for the evaluation of diet quality. Nutr. Hosp. 2015;31((Suppl. S3)):128–144. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.31.sup3.8761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim S., Haines P.S., Siega-Riz A.M., Popkin B.M. The Diet Quality Index-International (DQI-I) provides an effective tool for cross-national comparison of diet quality as illustrated by China and the United States. J. Nutr. 2003;133:3476–3484. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.FAO/WHO . Sustainable Healthy Diets—Guiding Principles. FAO; Rome, Italy: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 48.NCI Dietary Assessment Primer: Screeners at a Glance. [(accessed on 9 September 2023)]; Available online: https://dietassessmentprimer.cancer.gov/profiles/screeners/index.html.

- 49.Kronsteiner-Gicevic S., Tello M., Lincoln L.E., Kondo J.K., Naidoo U., Fung T.T., Willett W.C., Thorndike A.N. Validation of the Rapid Prime Diet Quality Score Screener (rPDQS), A Brief Dietary Assessment Tool with Simple Traffic Light Scoring. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2023;123:1541–1554.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2023.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson F.E., Kipnis V., Subar A.F., Krebs-Smith S.M., Kahle L.L., Midthune D., Potischman N., Schatzkin A. Evaluation of 2 brief instruments and a food-frequency questionnaire to estimate daily number of servings of fruit and vegetables. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;71:1503–1510. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willett W. Nutritional Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Volume 40. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: 2013. 529p Monographs in epidemiology and biostatistics. [Google Scholar]

- 52.VEGANScreener VEGANScreener Project Description. 2022. [(accessed on 22 October 2023)]. Available online: https://www.veganscreener.eu/

- 53.Kant A.K. Dietary patterns and health outcomes. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2004;104:615–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boateng G.O., Neilands T.B., Frongillo E.A., Melgar-Quinonez H.R., Young S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health. 2018;6:149. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeVellis R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. 3rd ed. Volume i. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: 2012. 205p (Applied social research methods series). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woodcock T., Adeleke Y., Goeschel C., Pronovost P., Dixon-Woods M. A modified Delphi study to identify the features of high quality measurement plans for healthcare improvement projects. BMC Med. Res Methodol. 2020;20:8. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0886-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor E. We Agree, Don’t We? The Delphi Method for Health Environments Research. Herd-Health Environ. Res. 2020;13:11–23. doi: 10.1177/1937586719887709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsu C.C., Sandford B.A. The Delphi Technique: Making Sense of Consensus. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007;12:10. doi: 10.7275/pdz9-th90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qualtrics 2023. [(accessed on 9 September 2023)]. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com.

- 60.Wild D., Grove A., Martin M., Eremenco S., McElroy S., Verjee-Lorenz A., Erikson P. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Project REDCap. [(accessed on 15 April 2024)]. Available online: https://www.project-redcap.org/

- 62.Alessandrini R., Brown M.K., Pombo-Rodrigues S., Bhageerutty S., He F.J., MacGregor G.A. Nutritional Quality of Plant-Based Meat Products Available in the UK: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Nutrients. 2021;13:4225. doi: 10.3390/nu13124225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rizzolo-Brime L., Orta-Ramirez A., Martin Y.P., Jakszyn P. Nutritional Assessment of Plant-Based Meat Alternatives: A Comparison of Nutritional Information of Plant-Based Meat Alternatives in Spanish Supermarkets. Nutrients. 2023;15:1325. doi: 10.3390/nu15061325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flint M., Bowles S., Lynn A., Paxman J.R. Novel plant-based meat alternatives: Future opportunities and health considerations. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023;82:370–385. doi: 10.1017/S0029665123000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lima R.D., Block J.M. Coconut oil: What do we really know about it so far? Food Qual. Saf. 2019;3:61–72. doi: 10.1093/fqsafe/fyz004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.da Silveira J.A.C., Meneses S.S., Quintana P.T., Santos V.D. Association between overweight and consumption of ultra-processed food and sugar-sweetened beverages among vegetarians. Rev. De Nutr.-Braz. J. Nutr. 2017;30:431–441. doi: 10.1590/1678-98652017000400003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pagliai G., Dinu M., Madarena M.P., Bonaccio M., Iacoviello L., Sofi F. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2021;125:308–318. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520002688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Juul F., Vaidean G., Parekh N. Ultra-processed Foods and Cardiovascular Diseases: Potential Mechanisms of Action. Adv. Nutr. 2021;12:1673–1680. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen Z., Khandpur N., Desjardins C., Wang L., Monteiro C.A., Rossato S.L., Fung T.T., Manson J.E., Willett W.C., Rimm E.B., et al. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Three Large Prospective U.S. Cohort Studies. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:1335–1344. doi: 10.2337/dc22-1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.