Abstract

Background

Incarcerated mothers are a marginalised group who experience substantial health and social disadvantage and routinely face disruption of family relationships, including loss of custody of their children. To support the parenting role, mothers and children’s units (M&Cs) operate in 97 jurisdictions internationally with approximately 19 000 children reported to be residing with their mothers in custody-based settings.

Aim

This rapid review aims to describe the existing evidence regarding the models of service delivery for, and key components of, custodial M&Cs.

Method

A systematic search was conducted of four electronic databases to identify peer-reviewed literature published from 2010 onwards that reported quantitative and qualitative primary studies focused on custody-based M&Cs. Extracted data included unit components, admission and eligibility criteria, evaluations and recommendations.

Results

Of 3075 records identified, 35 met inclusion criteria. M&Cs accommodation was purpose-built, incorporated elements of domestic life and offered a family-like environment. Specific workforce training in caring for children and M&Cs evaluations were largely absent. Our systematic synthesis generated a list of key components for M&C design and service delivery. These components include timely and transparent access to information and knowledge for women, evaluation of the impact of the prison environment on M&C, and organisational opportunities and limitations.

Conclusion

The next generation of M&Cs requires evidence-based key components that are implemented systematically and is evaluated. To achieve this, the use of codesign is a proven method for developing tailored programmes. Such units must offer a net benefit to both mothers and their children.

Keywords: Public Health, Health policy, Maternal health, Child health

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Mothers and children’s units are reported to be operating in approximately 100 jurisdictions globally, however, evidence of best practice for models of service delivery in these units is scarce.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This rapid review systematically synthesises the evidence related to models of service delivery for mothers and children’s units operating in 16 countries allowing children to reside with their mother in a custodial setting. Findings suggest that the units are not evidence based, implemented systematically or routinely evaluated.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study provides a list of evidence-based key components to correctional centres that will inform policy and implications for practice in the future codesigned mothers and children’s units.

Introduction and background

When a mother is incarcerated, the impact on a child is far-reaching and substantial. The lifelong effects of incarceration on children with mothers in jail, prison or other correctional centres (CC) can be significant,1 however, evidence is scarce.2–5 The parent–child relationship significantly impacts a child’s social, emotional and intellectual development.6–9 In particular, there is a strong evidence supporting the importance of the mother–child bond on a child’s development. Adverse parental and/or family circumstances may act as substantial risk factors for long-term negative psychosocial effects on the child.2 10 In the context of criminal justice systems, research suggests that maternal incarceration places their children’s social, educational and emotional development at risk1 and inequitably exposes children to potentially traumatising experiences of a parent’s arrest, conviction, imprisonment and release.2 10

Following sentencing, women may enter the general prison/CC population, be diverted from prison/CC or placed on home detention or those with young children may apply for a place in a mothers and children’s unit (M&C) or nursery unit where they can reside with their child. The provision of M&Cs is common globally and is reported in 97 jurisdictions internationally where a child is allowed to reside with their mothers for a variable amount of time during their sentence.11 M&Cs have been operational for many decades and offer a way for mother and child to remain connected, furthermore, this may limit the impact on the family unit and the known substantial health and social issues for incarcerated mothers.12

There has been an alarming growth in the number of incarcerated women worldwide since 2010, many of which are mothers.13 The World Prison Population list estimates that 740 000 women are incarcerated worldwide with approximately 19 000 children residing with their mother in a CC setting.13 Women and children are residing in a variety of living arrangements in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries and non-OECD countries with a disproportionate number of incarcerated persons in non-OECD countries. The one exception is the USA, which is the country with the most people in CCs and the highest rate of incarceration globally.14 The global CC footprint continues to expand with 11.5 million people currently in CCs. Since 2000, increases are highest in South America >200%, Oceania >82%, Central America >77%, Asia >43%, Africa >38% and Europe >27%, with disproportionate increases for women and children, older people, ethnic minorities and Indigenous peoples.14 The World Female Imprisonment List reports that women and girls make up 6.9% of the global prison population. By region, African countries report 3.3%, in Europe 5.9%, in Oceania 6.7%, in Asia 7.2% and 8.0% in the Americas.13 Many women are convicted of non-violent offences connected to poverty and disadvantage and are often serving short sentences; however, any imprisonment is harmful for women and their children. The United Nations Bangkok Rules urges non-custodial sentences and diversion from prison for pregnant women, however, only 11 countries have adopted laws to prohibit the imprisonment of pregnant women or severely limit their detention.14

In the Australian context, the latest data from national statistical reports 15 16 are consistent with global trends and show the female prison population rapidly increasing over the past 10 years. Of the women imprisoned in Australia, approximately 85% reported ever having been pregnant, 1 in 50 reported being pregnant when they entered custody, and over 50% reported having at least one child for whom they were solely responsible.16 Furthermore, it has been reported that approximately 43 000 children in Australia have an incarcerated parent.17 18 Given this high number, and a context of many of the women being primary carers, there is a significant need for successful strategies to address concerns over child protection, and long-term developmental and psychosocial outcomes for children and mothers, respectively.

The rise in the number of incarcerated women presents challenges for judicial systems, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries. Moreover, there are non-standardised M&C units worldwide depending on the country’s approach towards incarcerated women. The absence of uniformity in implementation and insufficient documentation of unit evaluations has resulted in a substantial evidence gap, posing a challenge for adopting best-practice approaches to models of service delivery for M&C units. Therefore, the scope of this rapid review is to investigate the peer-reviewed published research regarding models of service delivery for custody-based units that support mothers and their children and build an evidence base for a more uniform approach to M&Cs.

Methods

This rapid review of published quantitative and qualitative research on mothers in custody who reside with their children utilises a framework synthesis approach. Framework synthesis is a systematic review method employed to address questions relating to healthcare practice and policy.19 It incorporates a stepwise approach to identify and select research studies for inclusion in the review and creates a framework of a priori themes. NVivo20 software was used to code and review relevant evidence for the included studies. Rapid reviews are a form of knowledge synthesis that follows the systematic review process in a simplified way to produce information and evidence that is timely, actionable and relevant to inform policy and systems change.21

Search strategy

The team articulated the research question with respect to Population, Context, Phenomena of Interest, Study Design and Time Frame (online supplemental table 1).22

bmjgh-2023-012979supp001.pdf (117.8KB, pdf)

Search method

In May 2022, four electronic databases were searched (Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus and SocINDEX) to identify published quantitative and qualitative literature relating to custody-based units that house mothers with their children. Databases were chosen specifically to focus on behavioural science, social science and criminology. The search strategy comprised four core concepts that were defined using a combination of words and truncations relating to “Mother”, “Children”, “Programs” and “Prison” (online supplemental table 2). The search terms were run in Google and Google Scholar. The electronic database, Google and Google Scholar searches were supplemented with a lateral search of reference lists contained in articles identified from the literature search. Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to screen articles identified via the database search (online supplemental table 3). Briefly, any primary research article published from 2010 onwards, reporting on women residing in a CC with their child for any period of time, and all outcomes were included. The United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (Bangkok Rules) were established in 2010 whereby prisons had the first guidelines that were specific to incarcerated women and related to motherhood and children. Publications describing operations after 2010 are of particular interest in respect to potential changes that may have come about in response to the Bangkok Rules.23

Screening

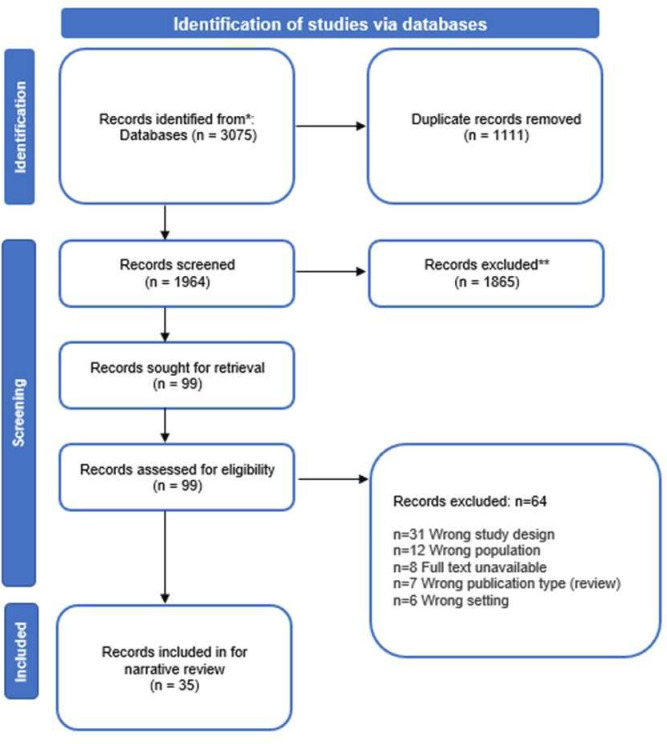

All records retrieved from electronic databases, and Google and Google Scholar searches were uploaded into Covidence,24 a Cochrane endorsed software package for conducting systematic reviews. Duplicate records were removed in Covidence and three reviewers (JT, TM and LE) screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining records. After screening titles and abstracts, the full texts of the remaining records were screened by two reviewers (JT and TB). Records that met the inclusion criteria were extracted. Reasons for exclusion of records that did not progress to full-text review were reported in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram25 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram(*Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, SocINDEX, **Records not eligible for full text review). The date of publication for included publications ranged from 2010 to 2022, with the majority (n=21, 60%) of publications occurring within the last 5 years (2017–2022). The studies reported in these publications included quantitative (n=16), qualitative (n=16) and mixed methodologies (n=3). Inconsistent comparison groups were reported in 10 publications,27 28 36–42 56 and included mothers separated from their children27 42 and mothers ineligible for an M&C.39 Table 1 details the study characteristics. M&C, mothers and children’s units; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included publications

| Study characteristics | No of publications | Reference |

| Publication date (2010–2022) | 35 | 27–61 |

| OECD Country (M&C location) |

20 | 27 28 32 33 35–37 39–43 45 48–50 52 53 55 |

| USA | 10 | 37–43 50 53 |

| France | 5 | 33 36 48 49 55 |

| UK | 2 | 27 28 |

| Australia | 1 | 35 |

| Chile | 1 | 52 |

| Finland | 1 | 32 |

| Non-OECD country | 15 | 29–31 34 44 46 47 51 54 56–61 |

| Brazil | 5 | 30 31 44 46 47 |

| Argentina | 2 | 56 58 |

| Cameroon | 1 | 54 |

| Ethiopia | 1 | 51 |

| India | 1 | 61 |

| Iran | 1 | 29 |

| Malawi | 1 | 59 |

| Mozambique | 1 | 57 |

| South Africa | 1 | 34 |

| Zimbabwe | 1 | 60 |

| Language | ||

| English | 28 | 27–29 32 34 35 37–51 53–55 58–61 |

| French | 2 | 33 36 |

| Portuguese | 3 | 30 31 57 |

| Spanish | 2 | 52 56 |

| Study design | ||

| Qualitative | 16 | 29 31 34 39 45 46 48–51 53–55 57 59 60 |

| Quantitative | 16 | 27 28 33 36–38 40–44 47 52 56 58 61 |

| Mixed methods | 3 | 30 32 35 |

| Study population | ||

| Mothers with children living in custody | 19 | 28 29 32–34 37 40 43–45 47 50 51 53 54 56 59–61 |

| Mothers with children living in custody and pregnant women | 12 | 30 35 38 39 41 46 48 49 52 55 57 58 |

| Children living in custody | 1 | 36 |

| Senior correctional stakeholders (commissioner of prison farms, senior correctional management staff, senior health officials, prison health staff, officers in charge) | 2 | 42 59 |

| Correctional staff directly involved in the female section of the prison | 4 | 32 54 59 60 |

| Representatives from a non-governmental organisation involved in prisons | 2 | 54 60 |

| Participants | ||

| Total participants | N=2168 | 27–61 |

| Total mothers | N=1101 | 27–30 32–35 37 39–57 59 60 |

| Total pregnant women | N=229 | 30 38 46 48 52 55 57 |

| Mothers and children (data not separated) | N=47 | 30 31 |

| Total children | N=699 | 28 29 32 33 36 37 40 42 44 45 48–52 55–57 61 |

| Other (correctional staff) | N=122 | 31 32 35 54 59 60 |

| Participants’ age (years) | ||

| Women’s age range | 17–46 | 27–30 33 34 36–57 |

| Women’s age NR | 31 32 35 55 59 61 | |

| Children’s age range | 0–17 | 28–30 34 36 37 40–42 44 45 48 49 51 52 55–57 61 |

| Children’s age NR | 27 31 32 35 38 39 43 46 47 50 53 54 59 60 | |

| Setting | ||

| Women and children are housed in separate units within a correctional centre | 21 | 28–32 34–37 39 41 42 45 46 48–51 53 55 56 |

| Women and children are housed units outside the correctional centre | 1 | 47 |

| Women and children are housed with the general prison population | 5 | 54 57 59–61 |

| NR | 7 | 27 33 38 40 43 44 52 |

M&Cs, mothers and children’s units; NR, not reported; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by four reviewers (JT, TM, LE and MR) who then summarised the evidence contained in the extracted data. Our team used Google translate or had language proficiency to assess the non-English publications. Following this, the research team analysed and grouped the emerging themes for narrative synthesis.

Data analysis and synthesis

Thomas and Harden’s26 approach to thematic synthesis guided the data analysis and synthesis. This included line-by-line coding of the introduction, results and discussion sections of included publications. Coding summaries of the evidence were grouped into seven themes and relevant subthemes and narratively synthesised. Results tables are included that present study characteristics, eligibility criteria, key components, policy and research considerations.

Public involvement statement

Corrective Services New South Wales (CSNSW) were industry collaborators in the development of the research question and rapid review study design. Dissemination strategies were codesigned and included an industry report, peer-reviewed publication, conference presentations nationally and internationally, and presentation to the Women’s Advisory Committee for CSNSW.

Results

Database and internet searches retrieved 3075 records (PsycINFO 815, Scopus 1188, SocINDEX 188, Web of Science 824, Google 14 and Google Scholar 46). Records were imported into Covidence, 1111 duplicates were removed and a further 1865 were removed during the title and abstract screening. We reviewed 99 full-text articles, of which 64 were excluded as they did not fit the selection criteria. Thirty-five articles met the criteria and were included in the rapid review (details in the PRISMA flow diagram,25 figure 1). Given the small number of publications that met inclusion criteria, the authors chose not to place restrictions on the outcomes, health related or otherwise, which would be assessed in our endeavour to comprehensively describe M&Cs. Note that several studies included in this review were reported in multiple publications. We extracted data and coded each of the publications separately.

The evidence extracted from the 35 included publications is presented across 7 themes: (1) ‘models of service delivery’ are presented across 6 subthemes: (1a) nomenclature; (1b) unit aims; (1c) admission processes; (1d) eligibility; (1e) accommodation type and features and 1f) unit limitations. (2) ‘Impact of the CC environment’ is presented across four subthemes: (2a) environment for the child; (2b) mothering in a CC; (2c) workforce training and support and (2d) parenting programmes. (3) ‘Key components’ extracted from all articles have been synthesised and collated and are presented in online supplemental table 6. (4) ‘Recommendations’ found in the publications are presented across two subthemes: (4a) policy considerations and (4b) future research. (5) ‘Risk and safety considerations for M&Cs’; (6) ‘delivery of healthcare’ and (7) ‘breast feeding’.

Models of service delivery

Nomenclature

Twenty-six publications used the terms ‘mothers’ and babies’ unit’ (MBUs)27–35 or ‘prison nursery’36–50 to describe the accommodation provided to mothers in a CC residing with their children. We are collectively referring to all units as M&C’s units.

M&C unit aims

The most frequently reported unit aim for M&Cs was to reduce recidivism,35 38 39 42 45 51 52 however, evidence that this aim was achieved is presented in only one publication.38 Carlso reports that there was a ‘…28% reduction of recidivism among nursery program participants as well as a 39% total reduction in the numbers of participants' returning to custody over an 18-year period…’ when compared with women not in the nursery programme, and therefore, not residing with their child.38 Maternal bonding and the attachment between mother and child underpinned unit aims described in four publications,28 35 39 52 while improved parenting was described as a unit aim in three publications.36 39 41 Walker et al 35 commented that for the M&Cs they examined, the unit ‘…goals are typically to reduce re-offending, improve mother–child attachment and protect and promote child health, well-being and development…’35 Unit aims are detailed further in online supplemental table 4.

Admission processes

CCs had variable admission processes that women had to meet to be eligible to apply for a place in an M&C. Eligibility differed from admission processes and was more specific to unit capability and specifications detailed below. Reasons for exclusion prior to the application were reported in nine publications27 35 36 38–40 43 45 53 and are detailed in online supplemental table 5.

Five publications discussed application processes required to gain a position within an M&Cs.32 35 39 45 53 These processes and approval criteria varied between the different jurisdictions in which the M&Cs were run. For instance, in one jurisdiction, the application process required the mother to complete a satisfactory written application, an essay, followed by two satisfactory in-person interviews with corrections counsellors and an in-person interview with a panel of corrections staff and facilitators who delivered parenting programmes.45 One publication reported that women were required to undertake a urine test to demonstrate that they were not currently using illicit drugs.35 Carlson38 reported that women have to sign an agreement and comply with specific requirements to be eligible for, and remain in, the M&C. Specifically, the women had to be the primary caregiver of the child on release, abide by the institution’s rules and avoid misconduct.38 Another publication reported that final decisions about whether an infant/child can live in CCs with their mother are made by CC general managers or senior executives in the corrective services35 and that the child’s best interest must be at the forefront of that decision.32 35

Eligibility

Alongside meeting the admission process steps were separate eligibility criteria. Eligibility requirements varied across countries, jurisdictions and centres. Mothers’ eligibility to access units was dependent on their security level and other factors, such as whether they had committed violent crimes and their pregnancy status. For children, eligibility depended primarily on their age and their mother’s length of stay. In practice, this meant that women who had completed the admission processes may not necessarily meet the eligibility criteria. Table 1 describes the specific requirements relating to the children (ie, age, length of stay), the units (ie, capacity and the maximum length of stay) and mothers (ie, security level, exclusions, pregnancy).

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for M&Cs

| Eligibility | Studies | OECD | Reference range | Citation |

| Age limits of child | 8 | 3 | ≤12 months | 31 34 37 41 44 47 50 |

| 13 | 12 | 18 months to 2 years | 28 32–34 36 39 42 48–50 52 53 55 | |

| 11 | 5 | 30 months to 8 years | 32 34 35 37 38 44 47 50 54 60 61 | |

| Length of stay for child | 3 | 3 | 30 days | 37 38 50 |

| 1 | 1 | 18 months | 36 | |

| 1 | 1 | 30 months mother and child released together | 45 | |

| Unit capacities | 11 | 9 | Reported on capacity | 29 32 35–39 45 48 53 61 |

| 6 | 5 | 4–29 dyads | 29 32 35 36 45 53 | |

| 1 | 44 children | 61 | ||

| Length of stay permitted by units | 14 | 5 | Linked to age limits of the child specified by each unit | 30 31 33 34 36–39 41 44 47 48 50 55 |

| Security level | 4 | 3 | Minimum security level | 34 35 45 53 |

| 1 | Moderate security level | 56 | ||

| Exclusion | 5 | 4 | History of child abuse or crimes against children | 30 35 38 42 50 |

| 2 | 2 | ‘Behaviours incompatible with care for their infants’ | 42 50 | |

| 1 | 1 | Testing positive for drugs | 50 | |

| 4 | 3 | Violent crimes | 34 42 50 | |

| 2 | 1 | High security | 34 35 | |

| 2 | 1 | ‘Longer sentences’ | 34 38 | |

| 1 | 1 | ‘Short sentences’ | 35 | |

| 1 | 1 | On remand (unsentenced) | 35 | |

| 1 | 1 | Aboriginal women (‘structural and systemic factors’) | 35 | |

| 1 | 1 | Rule infractions | 45 | |

| Pregnancy | 2 | 2 | Women must be pregnant at entry into custody | 39 53 |

Walker et al. 35 describe structural and systemic factors stating, ‘that keeping their baby is much harder, because of the stigma arising from their disadvantage and from simply being Aboriginal, in a society that stigmatises Aboriginal peoples.’ Other factors included, ‘children being forcibly removed, lived experience of out of home care, intergenerational trauma, poverty, worklessness, violence, drug and alcohol addiction, poor health, family disintegration, child removal, institutionalisation and chronic incarceration.’

M&Cs, mothers and children’s units; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

In M&Cs, children’s age limits ranged from birth37 50 up to 8 years of age.54 The length of stay was linked to the reported age limits for children permitted to reside in the units.30 31 34 36–39 41 44 47 48 50 55 Age 18–24 months was the most common age limit reported for the children,28 33 36 42 48 49 53 55 followed by under 18 months,32 34 39 48–50 52 however, some M&Cs only accommodated short stays up to 30 days post partum.37 50 Of the publications reporting on unit capacity (n=11), four specified that capacity was based on the number of mother–baby dyads35 37–39 with capacity ranging from 1039 to 15 babies.35 37 38 The two most commonly reported reasons for excluding women from M&Cs was a history of committing child abuse or crimes against children30 35 38 42 50 or a history of committing violent crimes.34 42 50 The most commonly required security level was minimum security34 35 45 53 while one publication reported that mothers with an intermediate security level were eligible.56

Accommodation type and features

The M&Cs described in these publications were primarily separate buildings within CC grounds that allowed the mothers and their children to reside independently from the general CC population. Such accommodation was often purpose-built, incorporated elements of domestic life,35 was child friendly and offered a family-like environment.29 One exception to this paradigm was described in an Australian M&C where the unit was located in a purpose-built separate dwelling outside the perimeter of the CC.35

In eight publications, accommodation for mothers in CCs and their children51 54 56–61 was alongside the general CC population and, in some centres, this included centres with male prisoners.54 60

Within the USA, M&Cs are only available in 11 states,50 and the included publications report that eligibility to access these M&Cs was restricted to women pregnant at the commencement of their sentence. It is notable that data on the states with the highest prisoner censuses suggests that there is limited access to M&Cs.42 Furthermore, in the USAs, mothers and newborns are routinely separated in those states that do not have M&Cs.50

CC environment and M&Cs

Environment for the child

The CC environment itself presents obstacles to the well-being of children, as noted in three publications.49 53 58 Specifically, the CC environment was described as: ‘potentially being too hostile for children’58; being an ‘overstimulating environment for children’49 and ‘prevent(ing) the ability to create a family-focused environment for both M&C’.53 One challenge experienced by mothers in an M&C was the rule of no touching between inmates; this rule also applied to children and was difficult to navigate.53 A lack of socialisation for children residing in M&Cs was discussed in four publications.49 53 57 58 Specifically, there were limitations to socialising with other women and/or children in prison.53 57 58

Mothering in a CC

Mothering ‘on the inside’ differs substantially from mothering ‘on the outside’, specifically, mothers in an M&C may be expected to bear sole responsibility for the child.30 31 35 54 57 This responsibility presents a unique paradigm of being the sole care-provider for their child while navigating reduced agency and parenting autonomy within a CC.48 Mothers reported feeling judged by staff and unable to freely parent in their own way.45 Furthermore, different mothering styles may cause direct conflict between CC staff and incarcerated mothers. This was particularly the case where some incarcerated mothers’ personal cultural practices differed from others in the M&C or from CC staff.55

These issues may be compounded where incarcerated mothers are required to participate in various activities in addition to those compulsory while in the M&C unit (eg, education, work placement and criminogenic courses) and have no autonomy to avoid participation.30 31 35 39 45 53

Workforce training and support

Reports about specific workforce training in child care are largely absent from the included publications, despite indications that custodial staff working in M&Cs are, in many cases, providing some form of care for the children.29 One publication reported that staff had expressed concerns regarding their roles in having to provide care for the infants residing with their mothers in custody and a lack of support in managing their own anxiety related to these responsibilities.35

Parenting programes within M&Cs

A number of different types of parenting courses for mothers in CC residing with their children are described in the included publications. For example, Byrne et al 37 report a nurse practitioner-led intervention in the USA designed to assist mothers in responsive parenting to foster infant security. Huber et al 52 discussed specific programmes offered to women in Chile while they are pregnant and in the postpartum period. During pregnancy, women attend 5-weekly sessions covering maternal depression, problem solving, bonding with the baby and preparation for motherhood. After the birth, weekly sessions for the mother and child are scheduled over a 4-week period with content focusing on attachment, postpartum depression, maternal awareness, sensitivity to infant, limits and structure.52 Similar programmes are offered in the UK,28 with interventions focusing on reflective practice for mothers to strengthen the mother/child bond.

Key components for service delivery

The primary function of CCs is to administer CC sentences; however, they may also be focused on rehabilitation and therefore offer additional support not consistent across M&Cs in all countries and contexts. M&Cs exist within the context of a CC environment and are subject to systems and organisational limitations that often have unintended impacts on mothers and their children. For example, the incompatibility of a hostile and noisy environment with caring for children. Our synthesis of the data from 35 publications was collated and has generated a list of key components linked to recommendations, provided by the authors, that may offer an evidence-based blueprint to streamline the service delivery of M&Cs. online supplementary table 6 summarises the most commonly reported key components and author generated linked implications for practice for consideration in the future design of M&Cs.

bmjgh-2023-012979supp002.pdf (79.6KB, pdf)

Policy and research considerations for newly designed M&C units

Policy and research recommendations were reported in many of the included publications. Table 3 summarises: (1) policy-level inputs and considerations for the development programme logic of newly designed units and (2) considerations for future research that were synthesised from the included publications. Each of these themes was explored in terms of four subthemes: systems and organisational, child, mother, mother and child.

Table 2.

Policy and research considerations from included publications

| Policy considerations | Future research | |

| Systems and organisational | Specialised training for staff associated with the M&Cs29 35 39 | Unit effectiveness27 28 33 37 50 52 53 |

| Training should include the correct application and removal of restraints as well as a basic education on the physiological process of birth39 | Continued documentation and assessment of M&Cs 39 35 | |

| Access to prerelease planning45 | Unit components and comparison of effects35 37 | |

| Child | Child-sensitive or child-reflective prison policy32 38 | Long-term anxieties or behavioural issues50 53 |

| Family support approach32 48 | Physical and mental health52 | |

| Parole supervision and postrelease placements need to accommodate coresidence (ie, drug and alcohol and mental health placements must accommodate coresiding children)42 51 | ||

| Mother | Alternatives to incarceration35 36 42 54 55 59 | Recidivism27 35 53 |

| Healthcare27 44 47 60 | Mental health41 43 52 | |

| Keeping mothers and children together35 36 | ||

| Mother and child | Attachment and mother child bond27 33 37 41 43 52 | |

| Follow-up evaluations of long-term effects on mother and child27 28 35 50 52 53 | ||

| Mother–child needs and unmet needs51 52 | ||

| Social support and stability28 33 |

M&Cs, mothers and children’s units.

Policy-level considerations

The majority (80%) of included publications recommended the need to develop policies relevant to M&Cs and conduct research into M&Cs.27–29 32–44 47 48 50–52 54–56 58–60 Policy considerations included the need for special training of M&C staff,29 35 39 that M&Cs adopt a child-sensitive CC policy32 38 and that alternatives to incarceration be made available to women with children or women who are pregnant.35 36 42 54 55 59

Future research considerations

Considerations for future research were focused on evaluating the effectiveness of units27 28 33 37 50 52 53; exploring the long-term anxieties or behavioural issues of children who have resided in an M&C50 53; measuring attachment and the quality of the mother–child bond27 33 37 41 43 52; and investigating rates of recidivism of mothers who previously resided in M&Cs.27 35 53

Risk and safety considerations for M&Cs

Risk and safety concerns for M&C residing in M&Cs included concerns related to pregnancy and childbirth, child visibility, safety and resourcing. Fritz and Whiteacre report that shackling of pregnant women at the time of birth continues in some instances, although many USA states have legislated against the practice. They argue that this policy is not supported by evidence and suggest that a thorough analysis of the practice is needed to inform policy that best protects the safety, security and dignity of all involved.39

Four publications recommended that alternatives to incarceration for mothers and pregnant women should be considered for women who commit predominately non-violent offences.42 54 55 59 Such an approach acknowledges that CC’s are not a preferred setting for pregnancy and birth and are likely to present an increased risk for mothers and infants postnatally.27 39 44 52 Diversion options suggested by Chaves and de Araújo30 include house arrest which is less restrictive for the mother–child, safer for the child, less expensive for the community and more likely to be in the best interest of the child.42

Several authors expressed that children in M&Cs are ‘institutionally invisible’.32 48 56 58 They further argued that as a result of this invisibility, the needs of these children are not adequately considered in the operational practices or policies of CCs. This is complicated further by organisational limitations in collecting data on children’s health and well-being while in an M&C and is evidenced by the absence of reported health outcomes for children.

Three publications recommend that policies be adopted within the M&Cs to protect the child’s safety.29 34 57 For example, children should not be permitted to have contact with the general CC population at any time during their stay.34 Apart from ensuring the safety of children in M&Cs, other recommendations focus on ensuring children’s contact with family outside the CC.34 61 Additionally, Mhlanga-Gunda et al noted that any M&Cs must provide appropriate and adequate foods for children residing with their mothers.60

Delivery of healthcare

Three of the included publications commented on the need for appropriate healthcare and service delivery models for incarcerated mothers and their children residing with them.27 52 60 Mhlanga-Gunda et al noted that providing adequate health services for M&C in CCs is supported under the sustainable development goals (SDGs 3, 5 and 16).60 Two publications also recommended improving access to services within CCs for mothers with mental health problems that arise during pregnancy and/or the postpartum period.27 52 The authors of one publication suggested improving access to healthcare for M&C in M&Cs by engaging clinicians from local health centres who visit children in the community through ‘mobile clinics’ to deliver similar healthcare in CCs.59 Specific health-related outcomes were not reported for children.

Breast feeding

Three publications from Brazil, Malawi and Zimbabwe noted that, in accordance with WHO policies, mothers in CCs should be encouraged to exclusively breastfeed their children for a minimum of 6 months after birth.44 59 60 Breastfeeding women have specific nutritional needs, and some authors of the included publications noted that these needs must be adequately met to prevent mother–child malnutrition in CCs.59 Breast feeding was not discussed in publications from the remaining 13 countries.

Discussion

This rapid review assessed the evidence reported in 35 publications relating to mothers residing with their children in a custodial setting known as M&C’s units. Our findings reveal a critical need for global M&Cs to implement an evidence-based and standardised approach to models of service delivery within CCs, which prioritise compassionate, empathetic and human rights-based treatment towards mothers and their children in custodial settings. M&Cs are likely to be impacted by geopolitical context and specific cultural norms, therefore, potential harms for children residing in an M&C may be specific rather than generalisable across all M&Cs. For example, in Cameroon and Zimbabwe, children are reported to be coresiding with the male prison population and is not comparable to OECD countries where M&Cs are female only separate purpose-built units.

In addressing this gap, efforts are needed across three key areas: (1) access to information and knowledge; (2) understanding the reality and impact of a CC environment on M&Cs and (3) systems and organisational opportunities and limitations for service delivery.

Information and knowledge

Entry to CC life, separation from their child/ren and assessing eligibility to an M&C are onerous and need to be streamlined and transparent. Clear information regarding eligibility criteria, application processes and current availability in M&Cs needs to be communicated to women at first contact with Corrective Services and at reception into the custodial setting to minimise the disruption in the care of the child. Additionally, efforts are needed to ensure equitable access for women with low literacy levels or from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) backgrounds, particularly if processes are written. One approach could be to link each mother with an appropriately trained support person, such as a case manager, to assist with organisational processes in order to facilitate equal access for all mothers to the units.

CC environment and health impacts

M&Cs are unique environments often located within a dominant CC culture that is at best neutral but often hostile to mothering in a CC. This brings a burden of scrutiny and judgement of the women from custodial staff incomparable to other settings. Mothering without the support of family and community is likely to be stressful for M&C, and custodial staff working in M&Cs have limited training in the care of children and knowledge of how to support mothers. To achieve any change in culture and practice the implementation of targeted training for all M&C staff is one evidence-based strategy to improve service delivery, communication and understanding.62 Additionally, the over-representation of First Nations women in CCs demands that culturally appropriate, sensitive and safe practices be imbedded in all staff training that addresses racism and intergenerational trauma.

Concurrently, there is an opportunity to include a suite of programmes to support mothers and their children, such as parenting programmes on child development, maternal bonding and reflective practice to strengthen attachment and the mother/child relationship. Adequately supporting mothers in work placements, education and training with safe and acceptable childcare may increase the likelihood of employment and secure housing postrelease.63 One example could be a shared care model45 whereby people are nominated to support mothers in M&Cs to share childcare responsibilities. This model has capacity to include educators, custodial staff and counsellors to support and monitor the well-being of the child and actively engage with M&C’s day-to-day lives. Shared responsibility may be a proportionate and appropriate response and alleviate the sole responsibility mothers currently bear. Another example is seen in a study in Texas, USA that did not meet our inclusion criteria and offered a novel approach whereby women completing their sentence were residing with their children in an ‘out-of-prison nursery programme (BAMBI)’. The impact of this programme which provided participants with closer proximity to community warrants further exploration as an alternative model for prison-based M&Cs, as such a model would better support postsentence reintegration.64

The long-term health impacts of M&Cs are unknown, however, previous studies on mother and child separation due to incarceration suggest that there may be long-term health impacts for children65 66 and mothers.65 67 68 While M&Cs seek to prevent this separation it is likely that there may be unintended consequences for M&C. Appropriate resourcing to provide commensurate healthcare, including mental health services, for M&C within an M&C is essential in minimising unintended harm and aligns with a human rights-based approach.23 69 70

Systems and organisational opportunities and limitations

Access to M&Cs is almost entirely restricted to low security level classification, posing the question as to whether women meeting these strict admission and eligibility criteria required by current M&Cs would be better placed in the community entirely. However, expanding the capacity of units to include women with higher security classifications warrants robust investigation as to the viability and impact on the child.

Women on remand or serving short sentences are often excluded from M&Cs due to insufficient time to complete criminogenic programmes, furthermore, those serving longer sentences may experience separation from their child due to operational limits of M&Cs. In addressing these limitations, novel approaches are emerging,38 45 59 60 such as, alternatives to incarceration or diversionary programmes.71 72 This is an important consideration for pregnant women and aligns with the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (Bangkok Rules),59 which state, ‘all efforts should be made to keep such women out of prison, taking into account the gravity of the offence committed and the risk posed by the offender to the public’.54

Moving towards best practice requires a systematic and standardised approach, that is, compatible with implementation and evaluation processes, however, evaluations of M&Cs are not commonplace. Evaluations of M&Cs should be undertaken using mixed methodologies including gathering data regarding participant and staff perspectives to contextualise quantitative survey data and qualitative interviews.31 39 50 52 60 Moreover, systems capability to capture relevant and meaningful data is essential.

This review highlights the need to revisit the appropriateness of custodial sentences, the benefits and harms to mother and child and the efficacy of diverting mothers from CCs, particularly, pregnant women, low-risk and non-violent offenders. Such alternatives may include a transition of oversight of M&Cs from correctional services to Community Services provided by governments. This change in practice could be supplemented by community-based parenting programmes, housing and employment support to reduce reoffending and support mothers living with their children long term. Community involvement using existing networks of family and friends is likely to maintain a child’s relationship and connection to the community. These connections can be an important predictor for children and their mothers’ effective reintegration into the community at the time of release.55 The benefits of such an approach need to be observed long-term and may include reduced contact with the criminal justice system and/or future contact with the juvenile justice system for their children.

Future research needs to be focused on outcomes for children who reside in M&Cs50 52 53 specifically, the health50 53 and development of the child.52 Study designs that can incorporate larger sample sizes27 31 39 45 50 52 59 together with specific sampling focusing on mothers,50 52 pregnant women39 and mother–child dyads are essential.45 Outcomes may differ for children born in an M&C and specific focus on how they transition to, and cope within the general community warrants investigation.50 53 Where mothers are unable to access an M&C, investigating the feasibility of family visit units for short stays to maintain family connection modelled on those operating in Finland32 and France48 warrants consideration.

Limitations

This rapid review only included publications where incarcerated mothers resided with their children in a custodial/prison-based setting. It did not include studies of mothers in CCs who are not residing with their child/ren. Our search strategy was systematic and provided a relatively thorough review of the available published literature since 2010, however, the synthesis of the findings was limited by the number of studies achieving peer-review publication and qualifying as evidence. The research question was not explored in PubMed as the authors chose to use Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus and SocINDEX. Our findings should be interpreted within the context of this limitation.

Our thematic synthesis of the data is based on 35 publications, and therefore, may not cover all M&C units in operation globally. There was a dearth of evidence reporting on First Nations Peoples and the findings of this review must be interpreted with this in mind. Although we make specific recommendations based on the findings of this review, we have not formally appraised the evidence for each of these recommendations. The authors acknowledge the differences in approaches to incarceration across jurisdictions are vast, however, this review is limited to those directly related to prion-based M&Cs.

Conclusion

M&C units that allow mothers in CCs to reside with their children are found in criminal justice systems in both OECD and non-OECD countries. However, information about the underlying policy, practices and outcomes of these units is scarce and that which exists is variable. There is a paucity of evidence on the long-term impacts of M&Cs on mothers and their children and addressing this gap in knowledge should be viewed as a priority. This rapid review synthesises research on M&Cs and can be used to inform the future design of evidence-based M&C units. New and redesigned units should be setup to ensure best practice and embed monitoring and evaluation into their design. Moreover, a system that has the capacity to measure long-term impacts of M&Cs for M&C will make an important contribution towards our understanding of whether such units are beneficial for children.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Stephanie M Topp

Contributors: ESullivan conceived the study, and MR and JT drafted the initial protocol. JT, TM, LE and MR were responsible for identifying the eligible studies. JT, LE, MR and TM worked on screening, data extraction and synthesis. All authors reviewed the themes. JT prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and TM and MR reviewed it, TM and MR continued to provide comments on revisions, with ESullivan, KA, MH and ESmith providing an expert review. The manuscript was critically reviewed by JT and all coauthors (TM, MR, LE, KA, MH, ESmith and ESullivan), who read and approved the final manuscript. ESullivan is the content guarantor.

Funding: The original report was funded by Corrective Services New South Wales.

Competing interests: The initial report was funded by Corrective Services New South Wales. Authors KA, ESmith and MH are employed by Corrective Services NSW.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Moore TG, McDonald M, Carlon L, et al. Early childhood development and the social determinants of health inequities. Health Promot Int 2015;30 Suppl 2:ii102–15. 10.1093/heapro/dav031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Comfort M. Punishment beyond the legal offender. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci 2007;3:271–96. 10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.3.081806.112829 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hagan J, Dinovitzer R. Collateral consequences of imprisonment for children, communities, and prisoners. Crime and Justice 1999;26:121–62. 10.1086/449296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnson EI, Waldfogel J. Children of incarcerated parents: multiple risks and children’s living arrangements; 2004.

- 5. Murray J, Farrington DP. The effects of parental imprisonment on children. Crime and Justice 2008;37:133–206. 10.1086/520070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frosch CA, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, O’Banion DD. Parenting and child development: a relational health perspective. Am J Lifestyle Med 2021;15:45–59. 10.1177/1559827619849028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zeanah CH, Lieberman A. Defining relational pathology in early childhood: the diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood DC:0-5 approach. Infant Ment Health J 2016;37:509–20. 10.1002/imhj.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Dev 1984;55:83–96. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zero to Three National Center for Infants T and Families, Zero to Three . Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. In: DC: 0-5TM. Washington, DC: Zero to Three, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arditti JA. Child trauma within the context of parental incarceration: a family process perspective. J Fam Theory Rev 2012;4:181–219. 10.1111/j.1756-2589.2012.00128.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Hout MC, Fleißner S, Klankwarth U-B, et al. “Children in the prison nursery”: global progress in adopting the convention on the rights of the child in alignment with United Nations minimum standards of care in prisons. Child Abuse Negl 2022;134:105829. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization . Women’s health in prison: correcting gender inequity in prison health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fair H, Roy W. World prison population list, 13th edition. World Prison Brief International Centre for Prison Studies, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Penal Reform International and Thailand Institute of Justice . Global prison trends 2022. Penal Reform International; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Australian Bureau of Statistics . National and state information about adult prisoners and community based corrections, including legal status, custody type, indigenous status, sex. A. corrective services, editor; 2021.

- 16. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Welfare AIoHa . The health and welfare of women in Australia’s prisons. Canberra: AIHW, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Catherine F. About 43,000 Australian kids have a parent in jail but there is no formal system to support them. The Conversation; 2022. Available: https://theconversation.com/about-43-000-australian-kids-have-a-parent-in-jail-but-there-is-no-formal-system-to-support-them-176039 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parliament of Victoria LC . ‘Inquiry into children affected by parental incarceration’. Victoria: Legal and Social Issues Committee; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brunton G, Oliver S, Thomas J. Innovations in framework synthesis as a systematic review method. Res Synth Methods 2020;11:316–30. 10.1002/jrsm.1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. QRS . NVIVO 12th edition. Victoria: QSR, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, et al. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev 2012;1:1–9. 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Santos C da C, Pimenta C de M, Nobre MRC. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2007;15:508–11. 10.1590/S0104-11692007000300023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. United Nations General Assembly . United Nations rules for the treatment of women prisoners and non-custodial measures for women offenders (the Bangkok rules), contract no.: 3:65; 2010.

- 24. Innovation VH . Covidence systematic review software Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; [Google Scholar]

- 25. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021;88:105906. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:1–10. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dolan RM, Birmingham L, Mullee M, et al. The mental health of imprisoned mothers of young children: a follow-up study. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol 2013;24:421–39. 10.1080/14789949.2013.818161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sleed M, Baradon T, Fonagy P. New beginnings for mothers and babies in prison: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Attach Hum Dev 2013;15:349–67. 10.1080/14616734.2013.782651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rahimipour Anaraki N, Boostani D. Mother-child interaction: a qualitative investigation of imprisoned mothers. Qual Quant 2014;48:2447–61. 10.1007/s11135-013-9900-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chaves LH, de Araújo ICA. Pregnancy and maternity in prison: Healthcare from the perspective of women imprisoned in a maternal and child unit. Physis 2020;30:1–22. 10.1590/S0103-73312020300112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diuana V, Corrêa MCDV, Ventura M. Mulheres nas prisões brasileiras: tensões entre a ordem disciplinar punitiva e as prescrições da maternidade. Physis 2017;27:727–47. 10.1590/s0103-73312017000300018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pösö T, Enroos R, Vierula T. Children residing in prison with their parents: an example of institutional invisibility. Prison J 2010;90:516–33. 10.1177/0032885510382227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Signori A, Sadoun-Haillard C, Bailly L, et al. Impact de la médiation animale sur le caregiving de mères détenues avec leur bébé Une étude pilote. Devenir 2020;32:163–79. 10.3917/dev.203.0163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Schalkwyk M, Cronje C, Thompson K, et al. An occupational perspective on infants behind bars. J Occup Sci 2019;26:426–41. 10.1080/14427591.2019.1617926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Walker JR, Baldry E, Sullivan EA. Residential programmes for mothers and children in prison: key themes and concepts. Crim Crim Just 2021;21:21–39. 10.1177/1748895819848814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Blanchard A, Bébin L, Leroux S, et al. Infants living with their mothers in the Rennes, France, prison for women between 1998 and 2013. Facts and perspectives. Arch Pediatr 2018;25:28–34. 10.1016/j.arcped.2017.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Byrne MW, Goshin LS, Joestl SS. Intergenerational transmission of attachment for infants raised in a prison nursery. Attach Hum Dev 2010;12:375–93. 10.1080/14616730903417011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carlson JR. Prison nurseries: a way to reduce recidivism. Prison J 2018;98:760–75. 10.1177/0032885518812694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fritz S, Whiteacre K. Prison nurseries: experiences of incarcerated women during pregnancy. J Offender Rehabil 2016;55:1–20. 10.1080/10509674.2015.1107001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goshin LS, Byrne MW. Predictors of post-release research retention and subsequent reenrollment for women recruited while incarcerated. Res Nurs Health 2012;35:94–104. 10.1002/nur.21451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kearney JA, Byrne MW. Reflective functioning in criminal justice involved women enrolled in a mother/baby co-residence prison intervention program. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2018;32:517–23. 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goshin LS, Byrne MW, Blanchard-Lewis B. Preschool outcomes of children who lived as infants in a prison nursery. Prison J 2014;94:139–58. 10.1177/0032885514524692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Borelli JL, Goshin L, Joestl S, et al. Attachment organization in a sample of incarcerated mothers: distribution of classifications and associations with substance abuse history, depressive symptoms, perceptions of parenting competency and social support. Attach Hum Dev 2010;12:355–74. 10.1080/14616730903416971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cavalcanti AL, Cavalcanti GM, Celino SDM, et al. Born in chains: perceptions of Brazilian mothers deprived of freedom about breastfeeding. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clín Integr 2018;18:1–11. 10.4034/PBOCI.2018.181.69 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Condon M-C. Early relational health: infants’ experiences living with their incarcerated mothers. Smith Coll Stud Soc Work 2017;87:5–25. 10.1080/00377317.2017.1246218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ferreira ACR, Rouberte ESC, Nogueira DMC, et al. Maternal care in a prison environment: representation by story drawing. Revista Enfermagem 2021;29. 10.12957/reuerj.2021.51211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leal M do C, Ayres B da S, Esteves-Pereira AP, et al. Birth in prison: pregnancy and birth behind bars in Brazil. Cien Saude Colet 2016;21:2061–70. 10.1590/1413-81232015217.02592016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ogrizek A, Lachal J, Moro MR. The process of becoming a mother in French prison nurseries: a qualitative study. Matern Child Health J 2022;26:367–80. 10.1007/s10995-021-03254-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ogrizek A, Moro MR, Lachal J. Incarcerated mothers' views of their children's experience: a qualitative study in French nurseries. Child Care Health Dev 2021;47:851–8. 10.1111/cch.12896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tuxhorn R. ““I’ve got something to live for now”: a study of prison nursery mothers”. Crit Crim 2022;30:421–41. 10.1007/s10612-020-09545-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gobena EB, Hean S. The experience of incarcerated mothers living in a correctional institution with their children in Ethiopia. JCSW 2019;14:30–54. 10.31265/jcsw.v14i2.247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huber MO, Venegas ME, Contreras CM. Group intervention for imprisoned mother-infant dyads: effects on mother's depression and on children's development. Revista Ces Psicologia 2020;13:222–38. 10.21615/cesp.13.3.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Luther Kate GJ. RESTRICTED MOTHERHOOD: parenting in a prison nursery. Int J Sociol Fam 2011;37:85–103. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Linonge-Fontebo HN, Rabe M. Mothers in Cameroonian prisons: pregnancy, childbearing and caring for young children. African Studies 2015;74:290–309. 10.1080/00020184.2015.1068000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ogrizek A, Radjack R, Moro MR, et al. The cultural hybridization of mothering in French prison nurseries: a qualitative study. Cult Med Psychiatry 2023;47:422–42. 10.1007/s11013-022-09782-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lejarraga H, Berardi C, Ortale S, et al. Growth, development, social integration and parenting practices on children living with their mothers in prison. Arch Argent Pediatr 2011;109:485–91. 10.5546/aap.2011.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Arinde EL, Mendonça MH. Política prisional e garantia de atenção integral à saúde da criança que coabita com mãe privada de liberdade, Moçambique. Saúde Debate 2019;43:43–53. 10.1590/0103-1104201912003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Di Iorio S, Ortale M, Querejeta M, et al. Growth and development of children living in incarceration environments of the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 2019;21:118–25. 10.4321/S1575-06202019000300002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gadama L, Thakwalakwa C, Mula C, et al. 'Prison facilities were not built with a woman in mind': an exploratory multi-stakeholder study on women's situation in Malawi prisons. Int J Prison Health 2020;16:303–18. 10.1108/IJPH-12-2019-0069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mhlanga-Gunda R, Kewley S, Chivandikwa N, et al. Prison conditions and standards of health care for women and their children incarcerated in Zimbabwean prisons. Int J Prison Health 2020;16:319–36. 10.1108/IJPH-11-2019-0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sarkar S, Gupta S. Life of children in prison: the innocent victims of mothers’ imprisonment. J Nurs Health Sci 2015;4. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ryan C, Brennan F, McNeill S, et al. Prison officer training and education: a scoping review of the published literature. J Crim Justice Educ 2022;33:110–38. 10.1080/10511253.2021.1958881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Baldry E. Women in transition: from prison to…. Curr Issues Crim Justice 2010;22:253–67. 10.1080/10345329.2010.12035885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kwarteng-Amaning V, Svoboda J, Bachynsky N, et al. An alternative to mother and infants behind bars: how one prison nursery program impacted attachment and nurturing for mothers who gave birth while incarcerated. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2019;33:116–25. 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mulligan C. Staying together: mothers and babies in prison. Br J Midwifery 2019;27:436–41. 10.12968/bjom.2019.27.7.436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nelson CA, Scott RD, Bhutta ZA, et al. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ 2020;371. 10.1136/bmj.m3048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rose SJ, LeBel TP. Incarcerated mothers of minor children: physical health, substance use, and mental health needs. Women Crim Just 2017;27:170–90. 10.1080/08974454.2016.1247772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Breuer E, Remond M, Lighton S, et al. The needs and experiences of mothers while in prison and post-release: a rapid review and thematic synthesis. Health Justice 2021;9:31. 10.1186/s40352-021-00153-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) . 1948.

- 70. United Nations Treaty Collection . Convention on the rights of the child, contract no.: 1577(3). UNCRC; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cassidy J, Ziv Y, Stupica B, et al. Enhancing attachment security in the infants of women in a jail-diversion program. Attach Hum Dev 2010;12:333–53. 10.1080/14616730903416955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bard E, Knight M, Plugge E. Perinatal health care services for imprisoned pregnant women and associated outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:285. 10.1186/s12884-016-1080-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2023-012979supp001.pdf (117.8KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2023-012979supp002.pdf (79.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.