Abstract

A man in his late 50s presented with severe dysphagia caused by a complex refractory benign stenosis that was completely obstructing the middle oesophagus. The patient was unsatisfied with the gastrostomy tube placed via laparotomy as a long-term solution. Therefore, we performed robot-assisted minimally invasive oesophagectomy (video). Mobilisation of the stomach and gastric conduit preparation were more difficult due to the previously inserted gastrostomy tube; thus, the conduit blood supply was assessed using indocyanine green fluorescence. After an uncomplicated course, the patient was referred directly to inpatient rehabilitation on the 16th postoperative day. At 9 months after surgery, the motivated patient returned to full-time work and achieved level 7 on the functional oral intake scale (total oral diet, with no restrictions). At the 1-year follow-up, he positively confirmed all nine key elements of a good quality of life after oesophagectomy.

Keywords: Endoscopy, Oesophagus, Rehabilitation medicine, Gastrointestinal surgery

Background

Complex strictures—that is, those that are long (>2 cm), tortuous or associated with a severely compromised luminal diameter—reduce a patient’s quality of life (mainly due to dysphagia) and may lead to severe adverse or even life-threatening events, such as malnutrition, weight loss and aspiration. Endoscopic treatment is often invasive and may require repetition, depending on the complexity. Satisfactory long-term results are achieved in less than half of cases. A suggested algorithm includes surgical therapy as a last option, that is, final resort, when endoscopic procedures are unsuccessful.1 2 Therefore, the low rate of elective oesophagectomy may be attributed to patients being satisfied with repeated endoscopic therapy, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube or jejunostomy tube; or to patients being anxious about and/or unfit for two-cavity major surgery. It is also conceivable that surgery may not be considered in many cases due to concerns regarding the morbidity and mortality associated with open oesophagectomy, which was the standard until a few years ago.

At our academic teaching hospital, the jointly developed technique of fully robotic four-arm robot-assisted minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy (da Vinci Xi Surgical System, Intuitive Surgical)3 has been successfully introduced. In a consecutive series of cases treated with robot-assisted minimally invasive oesophagectomy (RAMIE), the 10th case was of a multimorbid patient with adverse events related to a complex benign oesophageal stenosis that eventually became completely obstructive. Due to the prior open PEG placement with gastropexy, it was impossible to predict the preferred creation of a gastric conduit with certainty, presenting a particular challenge.

Case presentation

A man in his late 50s presented with an interest in potentially undergoing oesophageal resection for complete oesophageal stenosis. He was diabetic and hypertensive, suffered from heart failure and had only recently quit smoking (40 pack-years). His work as a sales representative had been suspended for 9 months. Over the past 7 months, the patient’s weight had decreased by 40 kg due to progressive dysphagia, yielding a body mass index (BMI) decrease from 36.4 to 22.3 kg/m2. Several oesophagogastroscopies revealed bleeding ulceration and long stenosis at 28–38 cm from the incisors. High-dose acid blockers had been prescribed in advance, and oesophageal dilatations and bougienage had been performed. Histopathological analysis of consecutive biopsies revealed non-specific inflammatory infiltrates without malignancy. The stenosis was refractory; therefore, a laparotomy was performed to insert a PEG tube. However, the patient’s oral intake of food and liquids had worsened to the lowest functional level on a 7-point ordinal scale (nothing by mouth, PEG-tube dependent).4 At the last external outpatient follow-up, endoscopic passage was not possible with either a small endoscope or a wire (table 1).

Table 1.

Patient’s medical history prior to presentation for oesophagectomy at our hospital

| Months prior to presenting | Finding | Treatment |

| 18 | Hidradenitis suppurativa, chronic abscess formation left axilla | Excision |

| 15 | Car accident due to stroke | Neurological and cardiovascular evaluation |

| 8 | Angina pectoris, three-vessel ischaemic heart disease; left ventricular ejection fraction ≈15% | Implementing intra-aortic balloon pumping, coronary bypass surgery |

| 6 | Dysphagia, feeling disgusted with eating | Nutritional care during postsurgery inpatient rehabilitation |

| 4 | Syncope, bolus obstruction, oesophageal stenosis and bleeding (Forrest Ib) | Intensive care unit, catecholamines, bolus removal and clipping by endoscopy, dilatation, placing nasogastric tube |

| 3 | Sternal wound infection, sepsis | Intensive care unit, catecholamines, antibiotics, debridement, vacuum sealing drainage, bilateral pectoralis major flap |

| 3 | >5 cm long filiform oesophageal stenosis, dysphagia, malnutrition | Bougienage <9 mm, placing nasogastric tube |

| 3 | Tube intolerance, parenteral nutrition | Laparotomy, PEG, gastropexy |

| 2 | Complete oesophageal obstruction | One-on-one interviews with psychologists, enteral nutritional care via PEG during inpatient rehabilitation |

| 1 | Complete oesophageal obstruction 22 cm from the incisors | Enteral nutritional care via PEG |

PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube.

Investigations

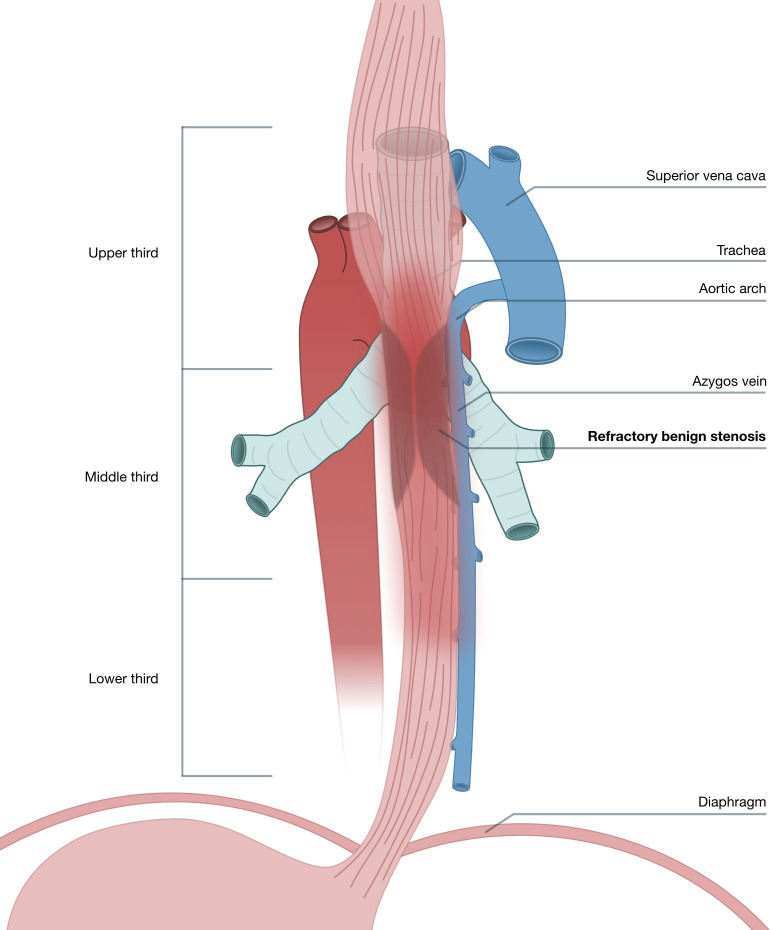

After an 18-month medical history, the divorced single male patient presented to us as depressed and physically weak, requiring a rollator. Endoscopy confirmed complete stenosis in the middle oesophagus (figure 1). CT revealed thickening of the upper and middle intrathoracic oesophageal wall, and a >6 cm long stenosis without contrast agent transit. The PEG entry is projected onto the antrum corpus junction. Laboratory test results revealed elevated squamous cell carcinoma antigen serum level (9.4 ng/mL; Cobas ECLIA Roche; reference range: ≤2.7 ng/mL), while other tumour markers (CA 72-4 and CEA) were within the reference range. Biopsies at the upper edge of the stenosis revealed base components of an ulcer with lymphoplasmacellular and granulocytic inflammation and fibrin precipitates, without evidence of malignancy. Colonoscopy revealed no abnormalities.

Figure 1.

Anatomical scheme, showing localisation of the stenosis in the middle and lower thoracic third of the oesophagus (posterior view).

Cardiological examination confirmed heart failure NYHA grades II–III. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed limited left heart function (25%–30%). It was estimated that the patient would have significantly increased cardiovascular risk during major surgery, which could not be optimised. There were no objections from the pulmonologist. Fibrobronchoscopy ruled out tracheal involvement. The increased perioperative risk profile was confirmed by the anesthesiologists and intensive care physicians (ASA III). Surgical therapy was desired by the patient and agreed on.

Differential diagnosis

A caustic, postradiotherapy or surgical aetiology of the complex stenosis could be excluded based on the patient’s medical history. There was no evidence supporting even rarer causes, such as lichen planus or AIDS.5 6 Inflammatory, drug-induced or ischaemic causes were probable, especially during the perioperative phase of urgent heart surgery 8 months prior. However, malignancy could not be completely ruled out. Therefore, in our multidisciplinary team conference for gastrointestinal tumours, the indication for minimally invasive oesophagectomy (MIE) with lymphadenectomy was accepted.

Treatment

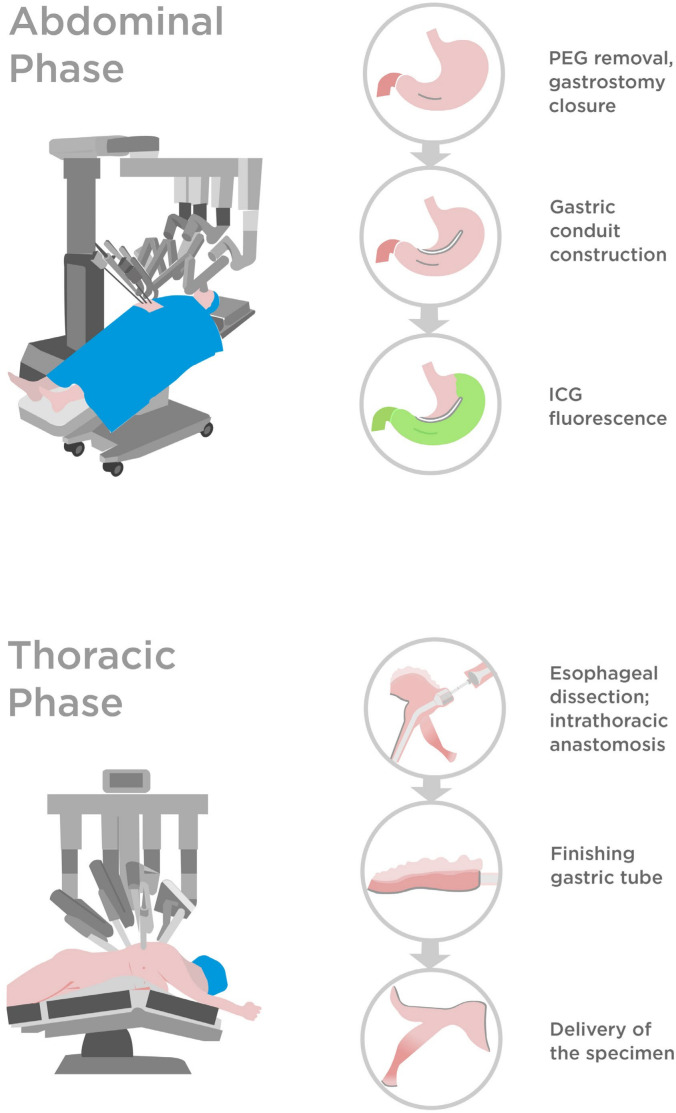

Unfortunately, oesophageal resection had to be postponed for 4 weeks due to severe sepsis with pulmonary involvement. After appropriate therapy, definitive robotic surgery was performed (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Key steps of the robot-assisted oesophagectomy (Ivor-Lewis) in the present case. ICG, indocyanine green; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

The tube was located in the middle of the corpus-antrum junction. After sparingly widening the gastrotomy, the PEG plate was completely removed. Next, the gastrohepatic ligament was dissected, with meticulous care taken to preserve the right gastric artery. The defect in the anterior wall was reinforced and tightened with three sutures, and a robotic stapler was used to close the stomach. This ventral stapler line was aligned to be approximately 2.5 cm below and parallel to the later ‘first’ stapler line—thereby forming the gastric conduit, beginning from the lesser curvature at the level of the incisura angularis. After full mobilisation of the stomach, radical lymph node dissection was feasible. The conduit blood supply, especially around the ventral staple line, was assessed using indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence (video 1).

Video 1. Robot-assisted oesophagectomy (Ivor-Lewis) for a complex stenosis previously managed by open gastrostomy tube placement (3 min).

The thoracic part of the RAMIE was standardised. However, we used both the Vessel Sealer and the Monopolar Cautery Hook for oesophageal and lymph node dissection, which was challenging due to perifocal inflammatory conditions and severe peristenotic fibrosis. The azygos vein was cut through with a linear stapler, and anastomotic reconstruction was performed using a circular stapler. The duration of the abdominal and thoracic portion of the surgery was 400 min.

Outcome and follow-up

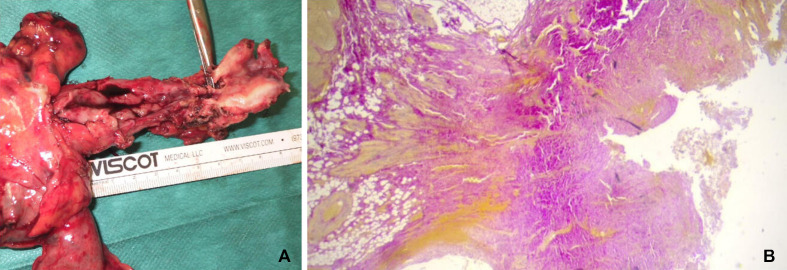

Final histopathological examination excluded oesophageal carcinoma. Partly granulomatous inflammatory reactions were observed in 24 examined lymph nodes. Examination revealed a high-grade ulcerative and stenosing oesophagitis with transmural fibrosis and intramural abscesses (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Specimen with oesophageal stenosis (A) ulcerated area, fibrosis (Elastica-van-Gieson, ×2.5) (B).

No postoperative complications were noted. The still-weakened patient was cared for by our multiprofessional team and was discharged 16 days after the operation, directly to rehabilitation, without dysphagia. During the 3-week inpatient rehabilitation phase, all individually set goals were achieved—including somatic, functional, psychosocial and informative-educational goals. The patient gained 3 kg in weight (to 68 kg) and was mobile without a rollator.

Three months later, at the surgical follow-up, the patient weighed 72 kg. He reported no dysphagia, and no longer exhibited a diabetic metabolic situation. The patient was again able to drive, and professional reintegration into his company was planned. In the cardiological follow-up, a defibrillator was recommended and was implanted 6 months postoperatively. At the 9-month surgical follow-up examination, the patient appeared with his new female partner. He achieved level 7 on the functional oral intake scale (total oral diet, with no restrictions)4 and returned to full-time work at his company. His weight was stable at 90 kg (BMI of 30 kg/m2). At 12 months postoperatively, the patient positively confirmed the following nine key elements of a good quality of life after oesophagectomy7: being able to eat adequately and enjoy it; to drink as desired, with moderate alcohol consumption; to do both of the above socially; to sleep comfortably in a normal position; to earn one’s living; to participate in sports or hobbies; to be free of pain; to have weight stability and to have an unimpaired libido.

Discussion

From an analytical point of view, our patient’s case constellation should be very rare. Long-term follow-up of approximately 4 years was realised in a large consecutive series of 70 selected patients with recurrent benign oesophageal stenosis, treated at two dedicated centres, within a period of 15 years.8 Long stenosis (>2 cm) was identified in 21 of these patients (30%), stenosis in the middle third of the oesophagus in 9 patients (12.8%) and post-inflammatory stenosis in only 3 cases (4.3%). Notably, less than 40% of cases experienced a satisfactory long-term result (>6 months dysphagia-free without needing further intervention and without a PEG tube) achieved by continuous or combined antegrade and retrograde dilation, bougienage and temporary stenting.

Considering that advanced endoscopic treatments carry an 8%–10% reported rate of serious adverse events and an 8% risk of death, our patient was also critically informed about equally risky surgical options, as requested. On one hand, surgery is part of complication management (4%); on the other hand, oesophagectomy is an elective option if endoscopic treatments fail (7%).8 9 MIE procedures are considered superior to open surgery. In a very large consecutive series of 1011 elective minimally invasive oesophagectomies, only 51 (5%) patients had benign disease.10 Therefore, patients and referring gastroenterologists should be informed that experience with elective oesophagectomy in the setting of benign disease is based on significantly smaller collectives. Such cases may involve far greater difficulties, especially due to long-term inflammation and fibrosis, compared with those encountered in patients who require surgery for malignancy.6 11

It must be noted that RAMIE is a pioneering procedure, requires a structured training pathway12 and can be combined with other assistance systems. It provides thtree-dimensional imaging of superior quality and free articulation of the robotic instruments, facilitating precise dissection and reducing the incidence of postoperative complications compared with open surgery, without increasing total hospital costs.3 13 For the complex treatment of colorectal, urological, endometrial, cervical and thoracic cancers, robotic-assisted surgery is usually equivalent to—or advantageous over—laparoscopic and thoracoscopic techniques.14 A comparative study showed that the rate of postoperative pneumonia after Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy was significantly lower after RAMIE than after MIE. Accordingly, hospital stays tended to be shorter after RAMIE (15 vs 17 days), which compensated for the significantly higher surgical costs.15 Similar results regarding cost efficiency have also been obtained for left colorectal resections, with robot-assisted surgical techniques having the benefit of reduced systemic inflammation.16

Before the surgery in our presently described case, RAMIE had already been easily carried out in our newly established robotic centre. Given the high volume of total complex robot-assisted colorectal, pancreas and liver operations that are already being performed, the hospital could be classified as a so-called mixed-volume hospital. Since the surgeon’s learning curve for RAMIE had already been overcome and the requirements for oesophageal cancer surgery in mixed and high-volume hospitals can be considered equivalent,17 we gave the patient the option of this innovative approach.

Considering two cases of robot-assisted McKeown oesophagectomy with cervical oesophagogastrostomy for dolichomegaesophagus,18 we discussed this fallback option with the patient. Gastric interposition was our procedure of choice; however, this could not be planned with certainty due to the PEG previously implanted via open surgery. This point is critical because PEG and jejunostomy tubes are formally an end-point for complex stenosis, with rates of 9%–42%.8 9 In the collective of Luketich et al, the minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy was preceded by a gastrostomy tube in only 2% of cases (9/530), but they did not provide information regarding technique in the case of gastric pull-up.10 In the case of elective oesophagectomy and gastric pull-up for cancer, the indication for PEG should be extremely critical and only determined in consultation with experienced surgeons (German guidelines).19 Catheter jejunostomy is preferable and can also be used in prehabilitation, and left as is during RAMIE.

In the present case, we determined that the robotic Ivor-Lewis procedure (RAMIE) was the best option. It was performed after successful PEG removal and with the use of ICG to monitor perfusion of the gastric conduit. The patient experienced an uncomplicated postoperative course, inpatient rehabilitation treatment and a medium-term course of a year and a half, with very satisfactory outcomes for the patient and our multiprofessional team.

Learning points.

Complex oesophageal stenosis can be treated with standardised Ivor-Lewis robot-assisted minimally invasive oesophagectomy (RAMIE). Treatment can be offered after considering the patient’s characteristics, the surgeon’s skillset and case volume and the recommendations of a highly experienced multidisciplinary team.

RAMIE may be considered earlier in the management of complex benign oesophageal stenosis, particularly to avoid unsolicited percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEGs), as these complicate or endanger gastric pull-up.

After the removal of a PEG from a potential gastric conduit, indocyanine green can be used to verify a sufficient blood supply.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the employees at St Georg Klinikum Eisenach/Thuringia who were involved in the treatment and care of the patient. I thank Dr. Peter Middel from the Institute of Pathology in Eisenach/West Thuringia and Dr. Torsten Winzer, director of the clinic and rehabilitation center and center for digestive diseases and metabolic diseases as well as teaching clinic for nutritional medicine in Bad Hersfeld/Hesse for their close cooperation. I am grateful to Sebastian Apweiler, Rebecca Donner and Remzi Gashi for their help with the schematic illustrations and the video editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: The following author was responsible for drafting of the text, sourcing and editing of clinical images, investigation results, drawing original diagrams and algorithms, and critical revision for important intellectual content: WK. The following author gave final approval of the manuscript: WK.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1. van Boeckel PGA, Siersema PD. Refractory Esophageal strictures: what to do when dilation fails. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2015;13:47–58. 10.1007/s11938-014-0043-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fugazza A, Repici A. Endoscopic management of refractory benign Esophageal strictures. Dysphagia 2021;36:504–16. 10.1007/s00455-021-10270-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tagkalos E, Goense L, Hoppe-Lotichius M, et al. Robot-assisted minimally invasive Esophagectomy (RAMIE) compared to conventional minimally invasive Esophagectomy (MIE) for Esophageal cancer: a propensity-matched analysis. Dis Esophagus 2020;33:doz060. 10.1093/dote/doz060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crary MA, Mann GDC, Groher ME. Initial Psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for Dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86:1516–20. 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rosic Despalatovic B, Bratanic A, Puljiz Z, et al. Esophageal stenosis in a patient with Lichen Planus. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2019;13:134–9. 10.1159/000498907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thakkar C, Joshipira V. Case report on Thoracoscopic Esophagectomy for long segment resistant Oesophageal Stricture in HIV infected patient. Int J Surg Case Rep 2021;80:105634:105634. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirby JD. Quality of life after Oesophagectomy: the patient perspective. Dis Esophagus 1999;12:168–71. 10.1046/j.1442-2050.1999.00040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Repici A, Small AJ, Mendelson A, et al. Natural history and management of refractory benign Esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;84:222–8:S0016-5107(16)00115-2. 10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jayaraj M, Mohan BP, Mashiana H, et al. Safety and Efficacy of combined Antegrade and retrograde endoscopic dilation for complete Esophageal obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Gastroenterol 2019;32:361–9. 10.20524/aog.2019.0385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Awais O, et al. Outcomes after minimally invasive Esophagectomy: review of over 1000 patients. Ann Surg 2012;256:95–103. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182590603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Young MM, Deschamps C, Allen MS, et al. Esophageal reconstruction for benign disease: self-assessment of functional outcome and quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:1799–802. 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01856-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kingma BF, Hadzijusufovic E, Van der Sluis PC, et al. A structured training pathway to implement robot-assisted minimally invasive Esophagectomy: the learning curve results from a high-volume center. Dis Esophagus 2020;33:doaa047. 10.1093/dote/doaa047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goense L, van der Sluis PC, van der Horst S, et al. Cost analysis of robot-assisted versus open transthoracic Esophagectomy for Resectable Esophageal cancer. results of the ROBOT randomized clinical trial. Eur J Surg Oncol 2023;49:106968:S0748-7983(23)00562-0. 10.1016/j.ejso.2023.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leitao MM, Kreaden US, Laudone V, et al. The RECOURSE study: long-term oncologic outcomes associated with Robotically assisted minimally invasive procedures for endometrial, Cervical, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2023;277:387–96. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Knitter S, Maurer MM, Winter A, et al. Robotic-assisted Ivor Lewis Esophagectomy is safe and cost equivalent compared to minimally invasive Esophagectomy in a tertiary referral center. Cancers (Basel) 2023;16:112. 10.3390/cancers16010112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Widder A, Kelm M, Reibetanz J, et al. Robotic-assisted versus Laparoscopic left Hemicolectomy-postoperative inflammation status, short-term outcome and cost effectiveness. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:10606. 10.3390/ijerph191710606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Romatoski KS, Chung SH, de Geus SWL, et al. Combined high-volume common complex cancer operations safeguard long-term survival in a low-volume individual cancer operation setting. Ann Surg Oncol 2023;30:5352–60. 10.1245/s10434-023-13680-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vetshev FP, Shestakov AL, Tadzhibova IM, et al. Initial experience of robot-assisted minimally invasive Mckeown Esophagectomy. Khirurgiia (Mosk) 2021;2:20–6. 10.17116/hirurgia202102120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie der Plattenepithelkarzinome und Adenokarzinome des Ösophagus, Langversion 2.0, 2018, AWMF Registernummer, Available: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/oesophaguskarzinom/ [Accessed 1 May 2023].