Abstract

We have described an oligomeric gp140 envelope glycoprotein from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that is stabilized by an intermolecular disulfide bond between gp120 and the gp41 ectodomain, termed SOS gp140 (J. M. Binley, R. W. Sanders, B. Clas, N. Schuelke, A. Master, Y. Guo, F. Kajumo, D. J. Anselma, P. J. Maddon, W. C. Olson, and J. P. Moore, J. Virol. 74:627–643, 2000). In this protein, the protease cleavage site between gp120 and gp41 is fully utilized. Here we report the characterization of gp140 variants that have deletions in the first, second, and/or third variable loop (V1, V2, and V3 loops). The SOS disulfide bond formed efficiently in gp140s containing a single loop deletion or a combination deletion of the V1 and V2 loops. However, deletion of all three variable loops prevented formation of the SOS disulfide bond. Some variable-loop-deleted gp140s were not fully processed to their gp120 and gp41 constituents even when the furin protease was cotransfected. The exposure of the gp120-gp41 cleavage site is probably affected in these proteins, even though the disabling change is in a region of gp120 distal from the cleavage site. Antigenic characterization of the variable-loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins revealed that deletion of the variable loops uncovers cryptic, conserved neutralization epitopes near the coreceptor-binding site on gp120. These modified, disulfide-stabilized glycoproteins might be useful as immunogens.

An immunogen able to induce effective humoral immune responses would be a valuable component of combination vaccines against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Such vaccines include ones in which cellular immunity is stimulated by live, recombinant viruses or DNA-based vectors (3, 19, 23, 30, 52). The monomeric HIV-1 gp120 glycoprotein does not elicit broadly neutralizing antibody responses against representative primary isolates (3, 14, 49). However, such proteins are still being included in combination vaccines, for want of anything better.

The HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein complex contains two subunits, the transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 and the surface glycoprotein gp120. The latter contributes most of the exposed surface area to the complex and contains the binding sites for the CD4 receptor and a coreceptor, either CCR5 or CXCR4 or both (35, 53, 64, 71, 72). The crystal structures of the core fragments of both gp41 and gp120 have been described (11, 26, 28, 68, 72). During envelope glycoprotein synthesis, a peptide bond that links the gp120 and gp41 components of the precursor polyprotein, gp160, is cleaved by proteases in the Golgi complex (17, 24, 31, 58, 69, 70). The gp120 and gp41 subunits are then noncovalently but weakly associated (22, 32, 38, 57). On the cell and virion surface, the envelope glycoproteins are organized in trimers via noncovalent gp41-gp41 interactions (11, 28, 29, 68).

The trimeric envelope glycoprotein complex mediates HIV-1 attachment and fusion. First, gp120 binds to the CD4 receptor, inducing conformational changes that expose the normally occult coreceptor binding site (64, 71). This involves the movement of the first, second, and third variable loops (V1, V2, and V3 loops) away from the coreceptor-binding site (59, 61, 73). Once gp120 interacts with the coreceptor, additional conformational changes expose fusion peptides at the N termini of the gp41 moieties, which then mediate fusion of the viral and cell membranes (11, 13, 25, 45, 68).

The envelope glycoproteins are important targets for the humoral immune response in that neutralizing antibodies are known that interfere with virus-cell attachment and fusion (41, 49, 50). To persist as a chronic infection in the face of a vigorous humoral response, HIV-1 has evolved ways to limit the generation of neutralizing antibodies and/or to minimize their effect on its life cycle. There is unusually extensive shielding of the conserved regions of gp120 by nonimmunogenic carbohydrates (48, 51); the CD4-binding site is recessed (26, 72); escape mutants can be generated in a relatively facile way, even to antibodies against the CD4-binding site (26, 72); variable loops hide the coreceptor-binding site until after the CD4 interaction has occurred, thereby minimizing the time and space available for antibodies to intervene against this stage of the fusion process (26, 36, 53, 59, 72).

Another defense mechanism is that the trimeric envelope glycoprotein spikes are poorly immunogenic compared to their dissociated subunits (9, 40, 50). Most infection-induced antienvelope antibodies are raised to uncleaved gp160 precursors, dissociated gp120, or gp41 ectodomains from which gp120 has been shed (39, 40, 50, 56), as is also the case in respiratory syncytial virus infection (55). Such “viral debris” does not antigenically mimic the native trimeric complex, so although the immune response to viral antigens is strong, that against infectious virus is weak. Viral debris might not just create an irrelevant immune response—it may even actively decoy antibody production away from the functionally important forms of the envelope glycoproteins (40, 50, 55).

All these factors impact upon the design of vaccines for inducing humoral immunity: The natural mechanisms used by HIV-1 to limit the immunogenicity of its envelope glycoproteins need to be understood and overcome. One approach that we and others are pursuing is the development of antigenic mimics of the native complex (5, 20, 74). We previously described such a protein (SOS gp140) in which the weak association between gp120 and the gp41 ectodomain is stabilized by the introduction of an intersubunit disulfide bond (5). However, it may be necessary to modify this protein to improve its immunogenicity. Several mutants of HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) gp120s have been made with the intent of immunogenicity enhancement; these include proteins that lack glycosylation sites or one or more of the variable loops (6, 10, 30, 51). Variable-loop-deleted gp120s are properly folded (4); indeed, one such protein from the HxBc2 strain was successfully crystallized as a ternary complex with soluble CD4 (sCD4) and the Fab fragment of the human monoclonal antibody (MAb) 17b (26, 72).

Here, we describe versions of the SOS gp140 protein with deletions of the V1, V2, and V3 loops. These modifications uncover conserved neutralization epitopes around the coreceptor-binding site in the context of a properly folded, fully processed, oligomeric envelope glycoprotein complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The envelope glycoproteins used in this study were derived from HIV-1 JR-FL, a subtype B, CCR5-using primary isolate. The pPPI4 plasmid expressing soluble gp140 lacking the transmembrane and intracytoplasmic domains of gp41 has been described elsewhere (5). Furin was expressed from the plasmid pcDNA3.1-furin (5, 62).

Construction of mutant envelope glycoproteins.

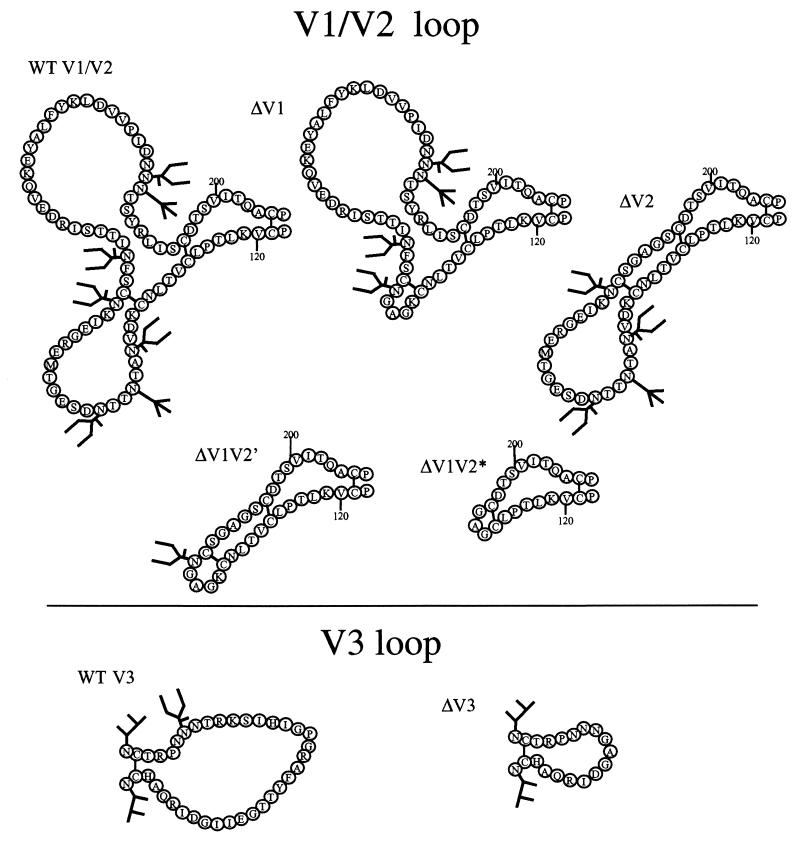

Plasmids encoding single-loop-deletion mutants were generated as follows; restriction sites are underlined. To delete the V1 sequences, two primers were designed that contain a unique NaeI site: 5JV1-N (5′-GTCTGAGTCGCCGGCTCCCTTGCAATTTAAAGTAACACAGAG-3′) and 3JV1-N (5′-GTCTGAGTCGGAGCCGGCAACTGCTCTTTCAATATCACC-3′). PCR amplification with primer pair 5′Kpn1env (5′-GTCTATTATGGGGTACCTGTGTGGAAAGAAGC-3′, which contains a unique KpnI site) and 5JV1-N and with primer pair 3JV1-N and 3′BstB1env (5′-GTCTGAGTCTTCGAATTAATAACCACAGCCATTTTG-3′, which contains a unique BstBI site) produced two fragments without the V1 sequences that contained the NaeI site. Cloning of these fragments into pPPI4 using the KpnI, NaeI, and BstBI sites produced the plasmid lacking the V1 sequences. Plasmids lacking the V2 or V3 sequence were constructed in an analogous manner. The primer pairs used to create ΔV2-env were 5′Kpn1env and 5JV2-B (5′-GTCTGAGTCGGATCCGGCACCAGAGCAGTTTTTTATTTCTCC-3′′) and 3′BstB1env and 3JV2-B (5′-GTCTGAGTCGGATCCTGTGACACCTCAGTCATTACACAG-3′). Primers 5JV2-B and 3JV2-B both contain a unique BamHI site. The fragments were cloned into pPPI4 using the KpnI, BamHI, and BstBI sites. The primers used to create the ΔV3 env gene were 5′Kpn1env and 5JV3-N (5′ - GTCTGAGTCGGAGCCGGCGATATAAGACAAGCACATTGTAAC - 3′) and 3′BstB1env and 3JV3-N (5′-GTCTGAGTCGCCGGCTCCATTGTTGTTGGGTCTTGTACAATTAATTTC-3′). Primers 5JV3-N and 3JV3-N both contain a unique NaeI site. The fragments were cloned into pPPI4 using the KpnI, NaeI, and BstBI sites. In the encoded glycoproteins, amino acids 133 to 155 (ΔV1), 159 to 194 (ΔV2), or 303 to 324 (ΔV3) were replaced by a glycine-alanine-glycine linker (GAG) (Fig. 1). The numbering of amino acids was based on the HxBc2 sequence, with the initiator methionine designated residue 1.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the V1, V2, and V3 regions of JR-FL gp120 and the deletions made in the various mutants. The structures and residue numbering scheme are based on the representation of JR-FL gp120 in reference 5, which is in turn based on the gp120 secondary structure described by Leonard et al. (27).

PCR amplification by primers 5′KpnIenv and 5JV1V2-B (5′-GTCTGAGTCGGATCCGGCACCAGAGCAGT TGCCGGCTCCCT TGCAAT T TAAAGTAACAA-3′), using a DNA template (pPPI4) coding for a V1-deleted Env, followed by digestion by KpnI and BamHI generated a fragment lacking the sequences encoding the V1 loop. This fragment was cloned into a pPPI4 plasmid lacking the sequences for the V2 loop using the KpnI and BamHI restriction sites. The resulting plasmid encoded gp140 lacking both the V1 and V2 loops and was named ΔV1V2′ (Fig. 1). A gp140 protein without the V1, V2, and V3 loops was created in a similar way but using a DNA fragment generated by PCR on a ΔV3 template with primers 3JV2-B and J140-BB. This was cloned into the ΔV1V2′ plasmid by using BamHI and BstBI. The resulting env sequences were named ΔV1V2′V3. Another, more extensively deleted form of ΔV1V2, termed ΔV1V2*, was also constructed (Fig. 1). Here, PCR amplification was performed with primers 3′ΔV1V2STU1 (5′-GGCTCAAAGGATATCT TTGGACAGGCCTG TGTAATGACTGAGG TGTCACATCCTGCACCACAGAG TGGGG TTAATTTTACACATGGC-3′, containing an StuI site) and 5′Kpn1env. The resulting fragment was digested with StuI and KpnI and cloned into a pPPI4 gp140 vector using the internal StuI site. The resulting ΔV1V2* gp140 protein had amino acids 127 to 195 replaced by the GAG linker (Fig. 1). The ΔV1V2*V3 protein was constructed in an analogous manner to ΔV1V2′V3. Amino acid substitutions were made with the Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene Inc.) using appropriate primers. The fidelity of all mutations was confirmed by sequencing. The absence of variable-loop epitopes from the loop-deleted proteins was confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with appropriate antibodies (4, 37, 39, 41, 42).

Transfection, labeling, and immunoprecipitation.

Adherent 293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine. Transient transfection of 293T cells was performed by calcium phosphate precipitation. The plasmids based on pPPI4 gp140 were transfected with and without the furin expression vector pcDNA3.1-furin, each at 10 μg per 10-cm2 plate. One day post-transfection, the medium was changed to DMEM supplemented with 0.2% bovine serum albumin, penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine. For radioimmunoprecipitation analysis (RIPA), [35S]cysteine and [35S]methionine (200 μCi per plate; Amersham International PLC) were added for 24 h in DMEM lacking cysteine and methionine as described previously (5). The culture supernatants were cleared of debris by low-speed centrifugation before addition of concentrated RIPA buffer to adjust the composition to 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.2). Envelope glycoproteins were immunoprecipitated with biotin-labeled or unlabeled MAbs in a 1-ml volume for 10 min at room temperature, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with either streptavidin-coated agarose beads (Vector Labs) or protein G-coated agarose beads (Pierce Inc.), as appropriate. The beads were washed three times with RIPA buffer containing 1% NP-40 detergent. Proteins were eluted by heating the beads at 100°C for 5 min in 60 μl of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) buffer supplemented with 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and, when indicated, 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The immunoprecipitates were fractionated by electrophoresis on SDS–8% PAGE gels at 200 V for 1 h. The gels were dried and exposed to a phosphor screen, and the positions of the radiolabeled proteins were determined using a PhosphorImager with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics Inc.).

MAbs to HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein epitopes and sCD4.

The epitopes and immunochemical properties of all the anti-gp120 and anti-gp41 MAbs used in this study have been described previously, as have their donors (5). Additional information on these MAbs has also been published (4, 7, 8, 18, 37, 39, 41–43, 46, 47, 53, 61, 65, 66, 72, 73). The tetrameric CD4-immunoglobulin G2 (CD4-IgG2) and monomeric sCD4 molecules, from Progenics Pharmaceuticals Inc., have also been described elsewhere (2).

Quantitation and characterization of gp120 and gp140 proteins by ELISA.

To measure the secretion of gp120 and gp140 proteins from transfected 293T cells, we used a gp120 antigen capture ELISA based on a previously described assay (4, 37, 39). Briefly, envelope glycoproteins in the culture supernatants were denatured and reduced by boiling with 1% SDS and 50 mM DTT. Purified, monomeric JR-FL gp120 treated in the same way was used as a reference standard for gp120 expression (5, 64). The denatured proteins were captured onto plastic via sheep antibody D7324, which was raised against the continuous sequence APTKAKRRVVQREKR at the C terminus of gp120. Bound envelope glycoproteins were detected using a mixture of MAbs B12 and B13 against continuous epitopes exposed on denatured gp120 (1, 39). This assay allows the efficient detection of both gp120 and any gp140 molecules in which the peptide bond between gp120 and the gp140 ectodomain is still intact (5, 64). Nondenatured envelope glycoproteins were detected using the QC256 pool of sera from HIV-1-infected individuals (37, 38).

RESULTS

Generation of variable-loop-deleted versions of the wild-type and SOS gp140 proteins.

Throughout the text, we refer to proteins that contain gp120 and the gp41 ectodomain (gp41ECTO) as wild-type (WT) gp140 proteins. The variants with cysteine substitutions that form an intermolecular disulfide bond between residues 501 of gp120 and 605 of gp41 are designated SOS gp140 proteins. Versions of these proteins without additional mutations are sometimes referred to as full-length to distinguish them from proteins from which one or more variable loops have been deleted; the latter are described as ΔV1, ΔV1 SOS, etc. For convenience, we refer to the variable-loop-deleted mutants as gp120s or gp140s irrespective of their actual size, the gp140s possessing the gp41 ectodomain in each case.

We generated a set of WT and SOS gp140 proteins with a deletion in one or more of the variable loops (Fig. 1). These were ΔV1 (amino acids 133 to 155 replaced by the GAG tripeptide), ΔV2 (amino acids 159 to 194 replaced by GAG), ΔV3 (amino acids 303 to 324 replaced by GAG), ΔV1V2′ (amino acids 133 to 155 and 159 to 194 replaced by GAG), and ΔV1V2* (amino acids 127 to 195 replaced by GAG). Two proteins with multiple loop deletions were also made, ΔV1V2′V3 and ΔV1V2*V3. Unlike the ΔV1V2* and ΔV1V2*V3 proteins, the ΔV1V2′ and ΔV1V2′V3 proteins still contained natural sequences between the V1 and V2 loops, including the glycosylation site at position 156 and the cysteines at positions 131 and 157 that form an intramolecular disulfide bond (Fig. 1). The designs of these various mutants were based on the results from previous studies with loop-deleted versions of gp120 monomers (4, 72, 73). To create disulfide-stabilized versions of the variable-loop-deleted gp140 proteins (loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins), we substituted residues alanine-501 of gp120 and threonine-605 of gp41 with cysteines, as previously described for the full-length gp140 protein (5).

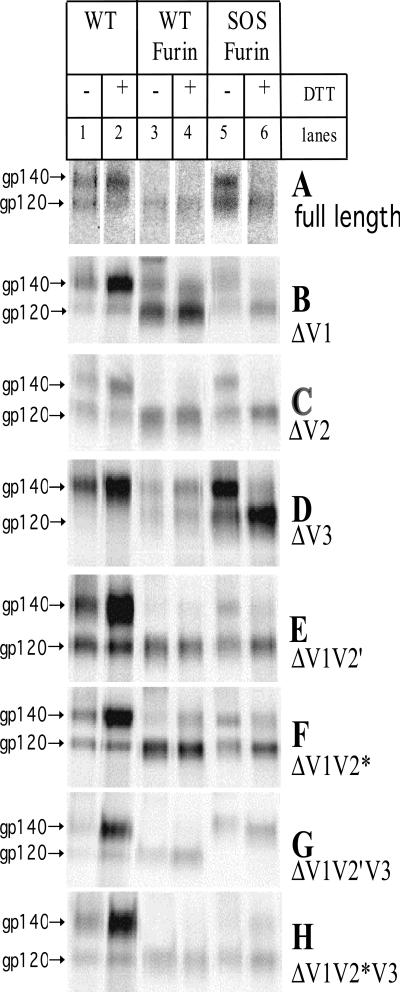

To investigate whether variable-loop-deleted gp140 proteins were properly folded and cleaved and whether they formed the SOS disulfide bond, they were expressed in the presence and absence of cotransfected furin and then immunoprecipitated with MAb 2G12. This recognizes a neutralizing, glycan-dependent epitope in the C3 and V4 regions of gp120 (similar results were obtained using anti-gp41 MAb 2F5; data not shown). The precipitated proteins were incubated with or without DTT prior to SDS-PAGE analysis to determine whether there was an uncleaved peptide bond or a reducible disulfide bond between gp120 and gp41ECTO (Fig. 2). The full-length gp140 proteins were also analyzed for comparison (Fig. 2A). Because of variations in the expression of the different gp140 variants and in their immunoprecipitation efficiencies, the intensities of different bands in Fig. 2 cannot be precisely compared. However, the various envelope proteins appeared to be secreted with different efficiencies. For example, ΔV1 SOS gp140 (Fig. 2B, lane 5) and ΔV2 gp140 (Fig. 2C, lane 1) were expressed relatively poorly, whereas ΔV3 SOS gp140 was expressed with significantly greater efficiency than the others (Fig. 2D, lane 5). Measurements of protein expression by ELISA were consistent with the RIPA analyses (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Analysis of cleavage and intermolecular disulfide bond formation in full-length and variable-loop-deleted gp140 proteins. Envelope glycoproteins secreted from transfected 293T cells were immunoprecipitated with MAb 2G12. Furin was cotransfected only with the SOS gp140 proteins. The WT gp140 proteins were produced in the absence (lanes 1 and 2) or presence (lanes 3 and 4) of cotransfected furin. The SOS gp140 proteins were produced in the presence of cotransfected furin (lanes 5 and 6). In each lane, the upper band represents a gp140 protein containing gp120 plus the gp41 ectodomain. These bands from WT proteins comprise uncleaved gp140 species in which the gp120-gp41ECTO cleavage site is unprocessed. In the case of SOS gp140 proteins, the upper bands represent disulfide-stabilized, proteolytically cleaved gp140s. In all cases, the lower bands are gp120 proteins, with or without deletions in their variable loops. The precipitated proteins were treated with DTT or not treated, as indicated. The full-length proteins are analyzed in panel A, and different variable-loop-deleted proteins are analyzed in panels B through H.

In most cases, both a gp120 band (or the variable-loop-deleted equivalent) and a gp140 band (or the variable-loop-deleted equivalent) were detected. Note that a gp140 (upper) band can represent either an uncleaved gp140 protein, in which gp120 is still linked to gp41ECTO by a peptide bond (Fig. 2, lanes 1 to 4), or an SOS gp140 protein, in which the gp120 and gp41ECTO moieties are associated by an intermolecular disulfide bond (Fig. 2, lane 5) that is susceptible to reduction by DTT (Fig. 2, lane 6). The two forms of gp140 proteins migrate identically on SDS-PAGE gels (5).

Like full-length WT gp140, none of the variable-loop-deleted gp140 proteins was completely cleaved in the absence of cotransfected furin, as indicated by the presence of uncleaved gp140 bands that survived DTT treatment (Fig. 2, compare lanes 1 and 2). In the presence of furin, the different variable-loop-deleted proteins were cleaved to various extents (Fig. 2, lane 3). For example, the ΔV2 and ΔV1V2′ gp140 proteins were efficiently cleaved, in that no gp140 band was now visible (Fig. 2C and E, lanes 3 and 4), whereas some residual uncleaved gp140 was produced from the ΔV1 and ΔV1V2* gp140 constructs, even in the presence of furin (Fig. 2B and F, lanes 3 and 4).

An intermolecular disulfide bond forms successfully in the SOS versions of the ΔV1, ΔV2, ΔV3, ΔV1V2′, and ΔV1V2* proteins (Fig. 2B to F, lanes 5 and 6). These are generally processed efficiently in the presence of furin, although some uncleaved gp140 protein is still present with ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 (Fig. 2F, lane 6). This apparently DTT-resistant gp140 is probably derived from high-molecular-weight aggregates that are disrupted by boiling with DTT (5). Such aggregates are produced from transient transfections with gp140- or SOS gp140-expressing plasmids but not from CHO cells stably expressing the SOS gp140 protein and furin (5) (data not shown).

Although the majority of the variable-loop deletants behaved like their full-length counterparts, some did not. The most notable differences were the absence of a gp140 band derived from the ΔV1V2*V3 SOS gp140 construct (Fig. 2H, lane 5) and the absence of gp120 bands derived from the ΔV3 gp140 and ΔV1V2′V3 SOS gp140 constructs even in the presence of furin and/or DTT (Fig. 2D, lanes 1 to 4, and Fig. 2G, lanes 5 and 6).

SOS bond does not form in ΔV1V2*V3 gp140.

No gp140 band was expressed from the ΔV1V2*V3 SOS gp140 construct (Fig. 2H, lane 5). However, when ΔV1V2*V3 SOS gp140 was treated with DTT, a faint DTT-insensitive gp140 band was visible (Fig. 2H, lane 6), derived from the DTT disruption of uncleaved gp140 aggregates. That the ΔV1V2*V3 SOS gp140 construct does not yield a gp140 protein while producing a gp120 could have one of two explanations. Either the 2G12 MAb does not bind the gp140 form of this protein because of structural perturbations introduced by the triple loop deletion that limit 2G12 epitope exposure, or the disulfide bond between cysteine residues 501 of gp120 and 605 of gp41 does not form in the context of this triple-loop-deleted protein.

To investigate the first possibility, we used a panel of MAbs to the CD4-binding site (CD4BS), CD4-induced (CD4i), and C4 epitopes on gp120 and the neutralizing anti-gp41 MAb 2F5. None of these MAbs precipitated a gp140 protein from the ΔV1V2*V3 SOS gp140 transfection. In contrast, every MAb, including 2G12, was able to precipitate an uncleaved ΔV1V2*V3 WT gp140 protein (data not shown). Hence, the deletion of all three variable loops does not cause a major structural perturbation to the gp120 core and its conserved epitopes.

The most likely explanation of the failure of multiple MAbs to detect the ΔV1V2*V3 SOS gp140 protein is that the protein is simply not secreted. Hence, when the V1, V2, and V3 loops are all deleted, the intermolecular disulfide bond cannot form between gp120 and gp41, so that no stable gp140 is produced. This is not the case when only the V1 and V2 loops are deleted or when only the V3 loop is removed (Fig. 2D to F, lane 5). Presumably, the triple-loop-deleted gp140 protein folds in such a way that the cysteine residues at positions 501 and 605 are not close enough to form a disulfide bond. On this assumption, we tried moving the gp120 cysteine from residue 501 to residue 500 or 502, but this did not restore the formation of the intermolecular disulfide bond (data not shown).

Some gp140 mutants are incompletely processed to gp120 and gp41ECTO.

The most likely explanation for the absence of gp120 bands from the ΔV3 gp140 (Fig. 2D, lanes 1 to 4) and ΔV1V2′V3 SOS gp140 preparations (Fig. 2G, lanes 5 and 6), even in the presence of furin, is due to inefficient cleavage of gp140 into gp120 and gp41ECTO subunits. In contrast to the extremely limited cleavage of the WT ΔV3 gp140 protein (Fig. 2D, lanes 1 to 4), the ΔV3 SOS gp140 protein was fully cleaved (Fig. 2D, lanes 5 and 6). It appears, then, that the deletion of the V3 loop modifies the conformation of the WT gp140 protein in such a way that its cleavage into gp120 and gp41ECTO subunits becomes inefficient. However, the introduction of the intermolecular disulfide bond into the SOS version of the ΔV3 gp140 protein restores the protein's conformation and permits cleavage to occur.

In contrast to WT ΔV3 gp140, the WT ΔV1V2′V3 gp140 protein was cleaved efficiently to gp120 in the presence of furin (Fig. 2G, lanes 3 and 4). Moreover, while the cleavage deficiency of the WT ΔV3 gp140 was rescued by introduction of an SOS bond, the ΔV1V2′V3 SOS gp140 expressed uncleaved gp140 (Fig. 2G, lanes 5 and 6). The diffuseness of the band and its low mobility compared with its WT gp140 counterpart (this is more easily discernable on gels that were run further; data not shown) suggests that the ΔV1V2′V3 SOS gp140 is a misfolded protein (5, 16) (Fig. 2G, compare lanes 5 and 1). Hence, the cysteine residues at positions 501 and 605 must inhibit the processing of the triple-loop-deleted SOS gp140 protein.

The processing efficiencies of the various loop-deleted WT and SOS gp140 proteins are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Proteolytic cleavage and intermolecular disulfide bond formation in full-length and loop-deleted WT and SOS gp140 proteinsa

| gp140 mutant | gp140 cleavage

|

Disulfide bond formation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT protein | SOS protein | ||

| WT, full length | +++ | +++ | + |

| ΔV1 | ++ | +++ | + |

| ΔV2 | +++ | +++ | + |

| ΔV3 | − | +++ | + |

| ΔV1V2′ | +++ | +++ | + |

| ΔV1V2* | ++ | ++ | + |

| ΔV1V2′V3 | +++ | − | − |

| ΔV1V2*V3 | +++ | +++ | − |

The original data are presented in Fig. 3 and 4. The extent of gp140 cleavage in the presence of cotransfected furin was determined. +++, 90 to 100% cleavage; ++, 60 to 90% cleavage; +, 30 to 60% cleavage; −, 0 to 30% cleavage. The formation of intermolecular disulfide bonds was determined in SOS gp140.

Exposure of gp120 C5 and gp41 epitopes on loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins.

We have shown that full-length uncleaved gp140 proteins differ in their antigenic structure from the SOS gp140 protein (5). Nonneutralizing epitopes in the C1 and C5 domains of gp120 and all gp41 epitopes except the neutralizing 2F5 epitope are obscured in the SOS gp140 protein, whereas they are exposed on the uncleaved gp140 proteins. In this respect, the SOS gp140 protein has antigenic properties similar to those of the native, virion-associated envelope glycoprotein complex, in which the C1 and C5 domains and much of the gp41 surface are involved in intersubunit interactions (5, 39, 56).

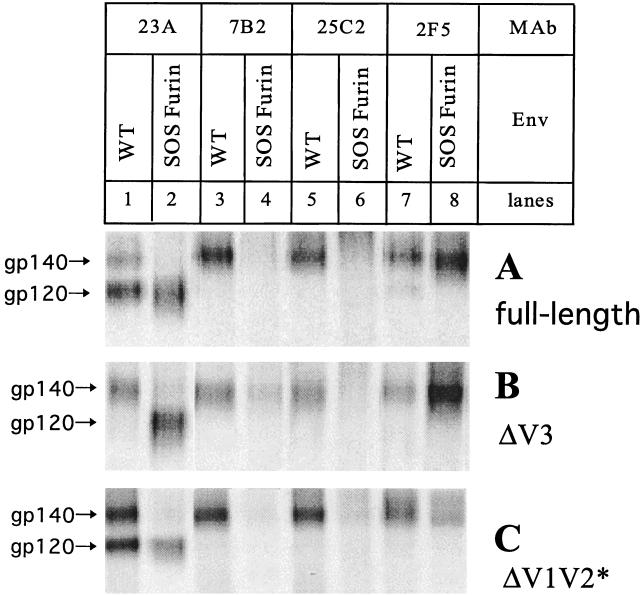

To study the antigenic structures of loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins, we first performed immunoprecipitations with MAb 23A, directed to the gp120 C5 domain, and to several regions of gp41 (MAb 7B2 to cluster I, MAb 25C2 to the cluster II/fusion domain, and MAb 2F5 to neutralization epitope ELDKWAS). The SOS gp140 forms of the full-length, ΔV3, and ΔV1V2* proteins (Fig. 3, even-numbered lanes) were compared with the WT versions of the same proteins, which produce gp120 and uncleaved gp140 (Fig. 3, odd-numbered lanes).

FIG. 3.

Antigenic structure analysis of variable-loop-deleted gp140 proteins. Envelope glycoproteins from (A) full-length, (B) ΔV3, and (C) ΔV1V2* WT and SOS gp140 proteins were precipitated with MAb 23A to the gp120 C5 region or with MAb 2F5, 25C2, or 7B2 to the gp41 ectodomain, as indicated. The WT gp140 proteins were expressed in the absence of cotransfected furin, yielding gp120 and uncleaved gp140 (odd-numbered lanes). Furin was cotransfected with the SOS gp140 proteins (even-numbered lanes).

The gp120 C5 MAb 23A failed to recognize the properly processed full-length SOS, ΔV1V2* SOS, and ΔV3 SOS gp140 proteins, but it bound to the uncleaved gp140 version of each of these proteins. The recognition by MAb 23A of the gp120 bands derived from the SOS gp140 transfections indicates that its epitope was not destroyed by the nearby cysteine substitution in the C5 domain (Fig. 3, compare lane 2 with lane 1). The nonneutralizing anti-gp41 MAbs 25C2 and 7B2 also did not bind to the full-length SOS, ΔV1V2* SOS, and ΔV3 SOS gp140 proteins, but they reacted efficiently with the corresponding uncleaved WT gp140 proteins (Fig. 3, compare lanes 4 and 6 with lanes 3 and 5). Similar results were obtained with several other nonneutralizing MAbs to various gp41 epitopes, such as 4D4, T15G1, and 2.2B (data not shown).

In contrast to what was found with the nonneutralizing MAbs, the neutralizing MAb 2F5 bound much more efficiently to the full-length and ΔV3 SOS gp140 proteins than to the uncleaved WT gp140 proteins (Fig. 3, compare lane 8 with lane 7). Taking into account the slightly reduced expression of the ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 protein compared with the WT ΔV1V2* gp140 protein (Fig. 3C, lanes 1 and 2), 2F5 reactivity was also greater with the SOS gp140 version (Fig. 3C, lanes 7 and 8). A similar pattern of data on 2F5 reactivity was obtained with other variable-loop-deleted gp140 and SOS gp140 proteins (data not shown).

Taken together, these experiments confirm that the ΔV1V2* SOS and ΔV3 SOS gp140 proteins are processed properly and that they retain the fundamental antigenic properties of the full-length SOS gp140 protein.

Exposure of CD4-binding site and CD4-induced epitopes on loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins.

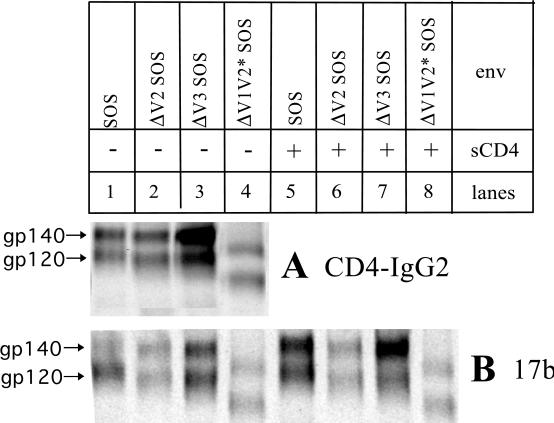

To assess whether the receptor-binding sites were preserved on the ΔV2 SOS, ΔV3 SOS, and ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 proteins, we first performed immunoprecipitations with the tetrameric CD4-IgG2 molecule (Fig. 4A). Like the full-length SOS gp140 protein, the variable-loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins could be efficiently precipitated with CD4-IgG2, confirming that the CD4-binding site was retained on these proteins (Fig. 4A). Similar results were obtained using MAbs IgG1b12 and F91 to epitopes which overlapped the CD4BS (data not shown). There was, however, reduced reactivity of IgG1b12 with SOS gp140 proteins lacking the V2 loop, consistent with the known influence of the V2 loop structure on the epitope for this MAb (8, 34, 54, 73).

FIG. 4.

Exposure of CD4BS and CD4i epitopes on variable-loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins. Envelope glycoproteins expressed from the full-length SOS gp140 protein and the ΔV2 SOS, ΔV3 SOS, and ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 proteins in the presence of cotransfected furin were immunoprecipitated with (A) the CD4-IgG2 molecule or (B) MAb 17b to a CD4i epitope in the presence and absence of sCD4.

Important elements of the coreceptor-binding site on gp120 overlap the epitopes for the human MAbs 17b and 48d, so these MAbs can be used as surrogates for the coreceptor interactions of gp120 proteins (26, 53, 72). The variable loops of gp120 partially occlude the 17b/48d epitope cluster until the binding of CD4 induces conformational changes that fully expose these epitopes; hence their designation as CD4i epitopes (59, 64, 71–73). The removal of the variable loops, especially the V1 and V2 loop structure, from monomeric gp120 constitutively increases the exposure of the CD4i epitopes (4, 73). We have shown that the CD4i epitopes are almost completely occluded on the SOS gp140 protein but that their exposure is greatly increased by sCD4 binding (5). We now sought to determine the effect on these epitopes of removing the variable loops from the SOS gp140 protein.

The full-length, ΔV2, ΔV3, and ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 proteins were immunoprecipitated with MAb 17b in the presence and absence of sCD4 (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained with MAb 48d and also with MAb A32 to a separate CD4i epitope (data not shown). Without sCD4, the 17b epitope was almost completely obscured on the full-length SOS gp140 protein, but it was strongly induced by sCD4 binding (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 1 and 5). In the absence of sCD4, the 17b epitope was partially exposed on the ΔV2 SOS and ΔV3 SOS gp140 proteins and well exposed on the ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 protein (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 2 to 4 with lanes 6 to 8). The binding of sCD4 strongly induced the 17b epitope on the ΔV3 SOS gp140 (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 7) but had little or no effect on the binding of 17b to the ΔV2 SOS and the ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 proteins (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 2 and 4 with lanes 6 and 8).

These results confirm that the CD4i epitopes are present on the variable-loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins. They are also consistent with the known involvement of the V1-V2 loop structure in shielding the CD4i epitopes (4, 73); the CD4i epitopes can be exposed either by removal of the variable loops or by sCD4 binding. Although both mechanisms can operate, once the CD4i epitopes are well exposed (as on the ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 protein), they can be further uncovered to only a limited extent by sCD4 binding.

The effect of sCD4 on 17b binding was much greater on the full-length and ΔV3 SOS gp140 proteins than on the corresponding gp120 monomers (compare the effect of sCD4 on the upper and lower bands in Fig. 4B, lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7). This presumably reflects the additional involvement of intersubunit interactions as part of the mechanisms that shield the CD4i epitopes on oligomeric envelope glycoproteins (5).

DISCUSSION

We aim to create envelope glycoproteins that are more immunogenic than presently available gp120 monomers or oligomers in which a peptide bond links gp120 with the gp41 ectodomain either by design or because of inefficient processing of the cleavage site. We have described oligomeric gp140 proteins stabilized by an intermolecular disulfide bond between gp120 and gp41ECTO (SOS gp140 proteins). These proteins mimic the antigenic structure of the native, fusion-competent glycoprotein complex found on the surfaces of virions or infected cells (5). The immunogenicity of the SOS gp140 proteins has yet to be evaluated, but we have anticipated the possibility that it might be necessary to alter their structure to improve the presentation of conserved neutralization epitopes.

Here, we describe SOS gp140 proteins from which one or more of the gp120 variable loops have been deleted to better expose underlying, conserved regions around the CD4- and coreceptor-binding sites. Two parameters that required characterization were whether an intermolecular disulfide bond could form between gp120 and gp41ECTO after deletion of variable loops and whether loop-deleted proteins could be properly processed at the gp120-gp41ECTO proteolytic cleavage site.

It was not possible to remove all three of the V1, V2, and V3 loop structures without adversely affecting the formation of the intermolecular disulfide bond and/or the proper proteolytic processing and folding of SOS gp140 proteins. However, each of the individual loops could be safely deleted, as could the V1 and V2 loops in combination. When the disulfide bond did form, the cleavage site was always efficiently utilized in the presence of cotransfected furin. Thus, we could successfully make the ΔV1, ΔV2, ΔV3, ΔV1V2′, and ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 proteins.

In the context of the WT gp140 protein, deletion of the V3 loop prevented cleavage of gp120 from gp41ECTO so that only uncleaved gp140 proteins were secreted, even when furin was cotransfected. An unexpected observation was that the formation of the intermolecular disulfide bond in the ΔV3 SOS gp140 protein completely reversed the cleavage deficiency. The removal of the V3 loop from gp120 appears to prevent the ΔV3 gp140 protein from folding correctly, so that the proteolytic cleavage site becomes inaccessible. The formation of the intermolecular disulfide bond presumably rescues the folding defect at an early stage of the synthesis of the ΔV3 SOS gp140 protein, so that the cleavage site becomes properly exposed (Table 1).

Introduction of the same intermolecular disulfide bond into the ΔV1V2′V3 gp140 protein had the opposite effect, however, in that this protein was efficiently cleaved but the ΔV1V2′V3 SOS gp140 protein was not. Conversely, the ΔV1V2*V3 SOS protein, which lacks the intramolecular disulfide bond at the base of the V1-V2 loop structure, was fully cleaved. However, in this protein, the intermolecular disulfide bond between gp120 and gp41ECTO did not form (Table 1). Neither triple-loop-deleted SOS gp140 construct gave rise to a disulfide-stabilized SOS gp140 protein.

Other than the presence or absence of the REKR cleavage site for furin proteases at the gp120 C terminus (24, 31, 44, 58, 69), several factors influence gp160 proteolysis. The cysteine residues at the base of the V3 loop are important for proper gp160 processing, at least in the context of envelope glycoproteins from the T-cell-line-adapted isolate LAI (12, 21, 63, 67). Substitutions within and around the small intramolecular disulfide-bonded loop in the gp41 ectodomain also impair the efficiency of gp160 cleavage (15, 60), especially in primary-isolate envelope glycoproteins (33). This loop is proximal to the gp41 cysteine substitution in the SOS gp140 proteins and is implicated in gp120 binding (5).

Many other cysteine residues in gp120 are also indispensable for proper processing and folding of the envelope glycoproteins (67). We therefore made two different ΔV1V2 proteins, one of which (ΔV1V2*) lacked the cysteines at positions 131 and 157 near the base of the V1-V2 loop structure. This protein was processed efficiently, indicating that these two cysteines are dispensable for the folding and cleavage of gp140. Deleting these cysteines is a known not to affect the folding of monomeric gp120 (72, 73). A Leu-to-Asp substitution at residue 266 in the third constant region of gp120 also dramatically impaired gp160 cleavage (70).

Overall, the efficiency of gp160 or gp140 cleavage can be sensitive to changes in multiple regions of the envelope glycoproteins in an unpredictable fashion. It may be that amino acid substitutions, even at distal locations, influence the folding of the envelope glycoprotein complex in a way that affects the exposure of the cleavage site and hence the extent to which it is processed by proteases. The WT gp140 proteins from a variety of HIV-1 and SIV isolates differ significantly in their cleavage efficiency (5) (data not shown). This again indicates the sensitivity of the conserved cleavage site to differences in protein conformation during envelope glycoprotein synthesis. A similar hypothesis could explain the lack of SOS bond formation in the triple-loop deletants.

Notwithstanding what remains to be learned about envelope glycoprotein processing pathways, we were able to make the ΔV1, ΔV2, ΔV3, ΔV1V2′, and ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 proteins. Among these, we have characterized the antigenic structure of the ΔV3 SOS gp140 and the ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 proteins in the most detail. These variable-loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins retain the desirable features of their full-length counterpart. Thus, the C5 region of gp120 and all the gp41 epitopes (except the 2F5 neutralization epitope) are not exposed on any of the SOS gp140 proteins. In contrast, gp120 epitopes relevant to virus neutralization are well exposed on the variable-loop-deleted SOS gp140 proteins; indeed, on the ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 protein, the CD4i epitope for MAb 17b is constitutively exposed without sCD4 addition. The CD4i epitopes are moderately accessible on the ΔV3 SOS gp140 protein but are still inducible by sCD4. On the full-length SOS gp140 protein, MAb reactivity with the CD4i epitopes is almost entirely dependent upon the presence of sCD4. Of note is that the occlusion of the CD4i epitopes is greater on the full-length, oligomeric SOS gp140 protein than in the corresponding gp120 monomer. This suggests that oligomerization increases the extent to which the CD4i epitopes, and presumably the proximal coreceptor-binding site, are shielded prior to CD4 binding.

Further modifications can be made to the SOS gp140 proteins, including reductions in their carbohydrate content. Deletion of the V1-V2 loop region removes almost one-third of the gp120 N-linked glycans, but we have found that other glycosylation sites in the C3 and V4 regions can be eliminated from the ΔV1V2* SOS gp140 protein without affecting its overall conformation. Removing variable loops and glycans from SOS gp140 proteins might also be useful for structural studies, based on how the gp120 core was crystallized (26, 72).

In summary, we have now made disulfide-stabilized SOS gp140 proteins with deletions of the V3 or the V1 and V2 loops. These proteins are properly processed and have favorable antigenic properties. The deletion of the variable loops increases the accessibility of the underlying, conserved neutralization epitopes on the gp120 moieties. However, the entire approach of deleting the variable loops depends upon the assumption that any antibodies that are induced to previously cryptic epitopes will be capable of binding back to the same structures on native virions and thereby neutralizing HIV-1 infectivity. The virions that must be countered by a vaccine contain the unmodified envelope glycoproteins on which the conserved epitopes remain shielded. Of note is that the 17b and 48d MAbs to the conserved, CD4i epitopes have little or no ability to neutralize primary isolates (59, 64, 71, 73). The deletion of the V1, V2, and V3 loops from gp120, uncleaved gp140, and gp160 forms of the envelope glycoproteins from the T-cell-line-adapted strain HXB2 either decreased the ability of the proteins to induce autologous neutralizing antibodies or had little effect (30). Whether modifications to the antigenic structure of SOS gp140 glycoproteins by variable-loop deletion translate into improvements in their immunogenicity remains to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gary Thomas for provision of the pGEMfurin plasmid and James Robinson and Herman Katinger for the gifts of several monoclonal antibodies. We appreciate the use of expression vectors and other reagents from Paul Maddon, Norbert Schuelke, and William Olson at Progenics Pharmaceuticals, as well as their advice and support.

This work was supported by RO1 grants AI 39420 and AI 45463.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abacioglu Y H, Fouts T R, Laman J D, Claassen E, Pincus S H, Moore J P, Roby C A, Kamin-Lewis R, Lewis G K. Epitope mapping and topology of baculovirus-expressed HIV-1 gp160 determined with a panel of murine monoclonal antibodies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:371–381. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allaway G P, Davis-Bruno K L, Beaudry G A, Garcia E B, Wong E L, Ryder A M, Hasel K W, Gauduin M C, Koup R A, McDougal J S, Maddon P J. Expression and characterization of CD4-IgG2, a novel heterotetramer that neutralizes primary HIV type 1 isolates. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:533–539. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett S W, Rajasekar S, Legg H, Doe B, Fuller D H, Haynes J R, Walker C M, Steimer K S. Vaccination with HIV-1 gp120 DNA induces immune responses that are boosted by a recombinant gp120 protein subunit. Vaccine. 1997;15:869–873. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binley J M, Wyatt R, Desjardins E, Kwong P D, Hendrickson W, Moore J P, Sodroski J. Analysis of the interaction of antibodies with a conserved enzymatically deglycosylated core of the HIV type 1 envelope glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:191–198. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binley J M, Sanders R W, Clas B, Schuelke N, Master A, Guo Y, Kajumo F, Anselma D J, Maddon P J, Olson W C, Moore J P. A recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein complex stabilized by an intermolecular disulfide bond between the gp120 and gp41 subunits is an antigenic mimic of the trimeric virion-associated structure. J Virol. 2000;74:627–643. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.627-643.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolmstedt A, Sjolander S, Hansen J E, Akerblom L, Hemming A, Hu S L, Morein B, Olofsson S. Influence of N-linked glycans in V4-V5 region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp160 on induction of a virus-neutralizing humoral response. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;12:213–220. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199607000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchacher A, Predl R, Strutzenberger K, Steinfellner W, Trkola A, Purtscher M, Gruber G, Tauer C, Steindl F, Jungbauer A, Katinger H. Generation of human monoclonal antibodies against HIV-1 proteins: electrofusion and Epstein-Barr virus transformation for peripheral blood lymphocyte immortalization. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:359–369. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burton D R, Pyati J, Koduri R, Sharp S J, Thornton G B, Parren P W, Sawyer L S, Hendry R M, Dunlop N, Nara P L, Lamacchia M, Garratty E, Stiehm E R, Bryson Y J, Moore J P, Ho D D, Barbas C F., III Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science. 1994;266:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7973652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton D R. A vaccine for HIV type 1: the antibody perspective. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10018–10023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao J, Sullivan N, Desjardin E, Parolin C, Robinson J, Wyatt R, Sodroski J. Replication and neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lacking the V1 and V2 variable loops of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:9808–9812. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9808-9812.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan D C, Fass D, Berger J M, Kim P S. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiou S H, Freed E O, Panganiban A T, Kenealy W R. Studies on the role of the V3 loop in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein function. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:1611–1618. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cladera J, Martin I, Ruysschaert J M, O'Shea P. Characterization of the sequence of interactions of the fusion domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus with membranes. Role of the membrane dipole potential. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29951–29959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor R I, Korber B T M, Graham B S, Hahn B H, Ho D D, Walker B D, Neumann A U, Vermund S H, Mestecky J, Jackson S, Fenamore E, Cao Y, Gao F, Kalams S, Kuntsman K, McDonald D, McWilliams N, Trkola A, Moore J P, Wolinsky S M. Immunological and virological analyses of persons infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1, while participating in trials of recombinant gp120 subunit vaccines. J Virol. 1998;72:1552–1576. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1552-1576.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dedera D, Gu R L, Ratner L. Conserved cysteine residues in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane envelope protein are essential for precursor envelope cleavage. J Virol. 1992;66:1207–1209. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1207-1209.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doms R W, Lamb R A, Rose J K, Helenius A. Folding and assembly of viral membrane proteins. Virology. 1993;193:545–562. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubay J W, Dubay S R, Shin H J, Hunter E. Analysis of the cleavage site of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein: requirement of precursor cleavage for glycoprotein incorporation. J Virol. 1995;69:4675–4682. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4675-4682.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Earl P L, Broder C C, Long D, Lee S A, Peterson J, Chakrabarti S, Doms R W, Moss B. Native oligomeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein elicits diverse monoclonal antibody reactivities. J Virol. 1994;68:3015–3026. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3015-3026.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Excler J L, Plotkin S. The prime-boost concept applied to HIV preventive vaccines. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl. A):S127–S137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farzan M, Choe H, Desjardins E, Sun Y, Kuhn J, Cao J, Archambault D, Kolchinsky P, Koch M, Wyatt R, Sodroski J. Stabilization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein trimers by disulfide bonds introduced into the gp41 glycoprotein ectodomain. J Virol. 1998;72:7620–7625. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7620-7625.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freed E O, Risser R. Identification of conserved residues in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 principal neutralizing determinant that are involved in fusion. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1991;7:807–811. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelderblom H R, Reupke H, Pauli G. Loss of envelope antigens of HTLV-III/LAV, a factor in AIDS pathogenesis? Lancet. 1985;ii:1016–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90570-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu S L, Klaniecki J, Dykers T, Sridhar P, Travis B M. Neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 BRU and SF2 isolates generated in mice immunized with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HIV-1 (BRU) envelope glycoproteins and boosted with homologous gp160. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1991;7:615–620. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inocencio N M, Sucic J F, Moehring J M, Spence M J, Moehring T J. Endoprotease activities other than furin and PACE4 with a role in processing of HIV-1 gp160 glycoproteins in CHO-K1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1344–1348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones P L, Korte T, Blumenthal R. Conformational changes in cell surface HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins are triggered by cooperation between cell surface CD4 and co-receptors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:404–409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet R W, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W A. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonard C K, Spellman M W, Riddle L, Harris R J, Thomas J N, Gregory T J. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10373–10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu M, Blackow S, Kim P. A trimeric structural domain of the HIV-1 transmembrane glycoprotein. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:1075–1085. doi: 10.1038/nsb1295-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu M, Ji H, Shen S. Subdomain folding and biological activity of the core structure from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41: implications for viral membrane fusion. J Virol. 1999;73:4433–4438. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4433-4438.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu S, Wyatt R, Richmond J F, Mustafa F, Wang S, Weng J, Montefiori D C, Sodroski J, Robinson H L. Immunogenicity of DNA vaccines expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein with and without deletions in the V1/2 and V3 regions. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:151–155. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCune J M, Rabin L B, Feinberg M B, Lieberman M, Kosek J C, Reyes G R, Weissman I L. Endoproteolytic cleavage of gp160 is required for the activation of human immunodeficiency virus. Cell. 1988;53:55–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90487-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKeating J A, McKnight A, Moore J P. Differential loss of envelope glycoprotein gp120 from virion of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: effects on infectivity and neutralization. J Virol. 1991;65:852–860. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.852-860.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merat R, Raoul H, Leste-Lasserre T, Sonigo P, Pancino G. Variable constraints on the principal immunodominant domain of the transmembrane glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1999;73:5698–5706. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5698-5706.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mo H, Stamatatos L, Ip J E, Barbas C F, Parren P W H I, Burton D R, Moore J P, Ho D D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants that escape neutralization by human monoclonal antibody IgG1b12. J Virol. 1997;71:6869–6874. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6869-6874.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore J P. Co-receptors: implications for HIV pathogenesis and therapy. Science. 1997;276:51–52. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore J P, Binley J. HIV: envelope's letters boxed into shape. Nature. 1998;393:630–631. doi: 10.1038/31359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore J P, McKeating J A, Jones I M, Stephens P E, Clements G, Thomson S, Weiss R A. Characterization of recombinant gp120 and gp160 from HIV-1: binding to monoclonal antibodies and soluble CD4. AIDS. 1990;4:307–315. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore J P, McKeating J A, Weiss R A, Sattentau Q J. Dissociation of gp120 from HIV-1 virions induced by soluble CD4. Science. 1990;250:1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.2251501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore J P, Sattentau Q J, Wyatt R, Sodroski J. Probing the structure of the human immunodeficiency virus surface glycoprotein gp120 with a panel of monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1994;68:469–484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.469-484.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore J P, Ho D D. HIV-1 neutralization: the consequences of viral adaptation to growth on transformed T cells. AIDS. 1995;9(Suppl. A):S117–S136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore J P, Sodroski J. Antibody cross-competition analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1996;70:1863–1872. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1863-1872.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore J P, Thali M, Jameson B A, Vignaux F, Lewis G K, Poon S W, Charles M, Fung M S, Sun B, Durda P J, Akerblom L, Wahren B, Ho D D, Sattentau Q J, Sodroski J. Immunochemical analysis of the gp120 surface glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: probing the structure of the C4 and V4 domains and the interaction of the C4 domain with the V3 loop. J Virol. 1993;67:4785–4796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4785-4796.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore J P, Trkola A, Korber B, Boots L J, Kessler J A, 2nd, McCutchan F E, Mascola J, Ho D D, Robinson J, Conley A J. A human monoclonal antibody to a complex epitope in the V3 region of gp120 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 has broad reactivity within and outside clade B. J Virol. 1995;69:122–130. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.122-130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morikawa Y, Barsov E, Jones I. Legitimate and illegitimate cleavage of human immunodeficiency virus glycoproteins by furin. J Virol. 1993;67:3601–3604. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3601-3604.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munoz-Barroso I, Salzwedel K, Hunter E, Blumenthal R. Role of the membrane-proximal domain in the initial stages of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion. J Virol. 1999;73:6089–6092. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6089-6092.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muster T, Guinea R, Trkola A, Purtscher M, Klima A, Steindl F, Palese P, Katinger H. Cross-neutralizing activity against divergent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates induced by the gp41 sequence ELDKWAS. J Virol. 1994;68:4031–4034. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.4031-4034.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muster T, Steindl F, Purtscher M, Trkola A, Klima A, Himmler G, Ruker F, Katinger H. A conserved neutralizing epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67:6642–6647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6642-6647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olofsson S, Hansen J E. Host cell glycosylation of viral glycoproteins—a battlefield for host defence and viral resistance. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:435–440. doi: 10.1080/00365549850161386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parren P W H I, Moore J P, Burton D R, Sattentau Q J. The neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1: viral evasion and escape from humoral immunity. AIDS. 1999;13(Suppl. A):S137–S162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parren P W H I, Burton D R, Sattentau Q J. HIV-1 antibody—debris or virion? Nat Med. 1997;3:366–367. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-366d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reitter J N, Means R E, Desrosiers R C. A role for carbohydrates in immune evasion in AIDS. Nat Med. 1998;4:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richmond J F, Lu S, Santoro J C, Weng J, Hu S L, Montefiori D C, Robinson H L. Studies of the neutralizing activity and avidity of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env antibody elicited by DNA priming and protein boosting. J Virol. 1998;72:9092–10000. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9092-9100.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rizzuto C D, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong P D, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280:1949–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roben P, Moore J P, Thali M, Sodroski J, Barbas C F, 3rd, Burton D R. Recognition properties of a panel of human recombinant Fab fragments to the CD4 binding site of gp120 that show differing abilities to neutralize human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:4821–4828. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4821-4828.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sakurai H, Williamson R A, Crowe J E, Beeler J A, Poignard P, Bastidas R B, Chanock R M, Burton D R. Human antibody responses to mature and immature forms of viral envelope in respiratory syncytial virus infection: significance for subunit vaccines. J Virol. 1999;73:2956–2962. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2956-2962.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sattentau Q J, Zolla-Pazner S, Poignard P. Epitope exposure on functional, oligomeric HIV-1 gp41 molecules. Virology. 1995;206:713–717. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schneider J, Kaaden O, Copeland T D, Oroszlan S, Hunsmann G. Shedding and interspecies type sero-reactivity of the envelope glycopolypeptide gp120 of the human immunodeficiency virus. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:2533–2538. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-11-2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stein B S, Engleman E G. Intracellular processing of the gp160 HIV-1 envelope precursor. Endoproteolytic cleavage occurs in a cis or medial compartment of the Golgi complex. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2640–2649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sullivan N, Sun Y, Sattentau Q, Thali M, Wu D, Denisova G, Gershoni J, Robinson J, Moore J P, Sodroski J. CD4-induced conformational changes in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 glycoprotein: consequences for virus entry and neutralization. J Virol. 1998;72:4694–4703. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4694-4703.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Syu W J, Lee W R, Du B, Yu Q C, Essex M, Lee T H. Role of conserved gp41 cysteine residues in the processing of human immunodeficiency virus envelope precursor and viral infectivity. J Virol. 1991;65:6349–6352. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6349-6352.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thali M, Moore J P, Furman C, Charles M, Ho D D, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Characterization of conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J Virol. 1993;67:3978–3988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3978-3988.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomas G, Thorne B A, Thomas L, Allen R G, Hruby D E, Fuller R, Thorner J. Yeast KEX2 endoprotease correctly cleaves a neuroendocrine prohormone in mammalian cells. Science. 1988;241:226–230. doi: 10.1126/science.3291117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Travis B M, Dykers T I, Hewgill D, Ledbetter J, Tsu T T, Hu S L, Lewis J B. Functional roles of the V3 hypervariable region of HIV-1 gp160 in the processing of gp160 and in the formation of syncytia in CD4+ cells. Virology. 1992;186:313–317. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trkola A, Dragic T, Arthos J, Binley J M, Olson W C, Allaway G P, Cheng-Mayer C, Robinson J, Maddon P J, Moore J P. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its co-receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:184–187. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trkola A, Pomales A B, Yuan H, Korber B, Maddon P J, Allaway G P, Katinger H, Barbas C F, 3rd, Burton D R, Ho D D, Moore J P. Cross-clade neutralization of primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by human monoclonal antibodies and tetrameric CD4-IgG. J Virol. 1995;69:6609–6617. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6609-6617.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trkola A, Purtscher M, Muster T, Ballaun C, Buchacher A, Sullivan N, Srinivasan K, Sodroski J, Moore J P, Katinger H. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:1100–1108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1100-1108.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tschachler E, Buchow H, Gallo R C, Reitz M S., Jr Functional contribution of cysteine residues to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope. J Virol. 1990;64:2250–2259. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2250-2259.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison S C, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Willey R L, Bonifacino J S, Potts B J, Martin M A, Klausner R D. Biosynthesis, cleavage, and degradation of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 envelope glycoprotein gp160. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9580–9584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Willey R L, Klimkait T, Frucht D M, Bonifacino J S, Martin M A. Mutations within the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp160 envelope glycoprotein alter its intracellular transport and processing. Virology. 1991;184:313–321. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu L, Gerard N P, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsetti A, Cardoso A A, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:179–183. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wyatt R, Kwong P D, Desjardins E, Sweet R W, Robinson J, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J G. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wyatt R, Moore J P, Accola M, Desjardin E, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Involvement of the V1/V2 variable loop structure in the exposure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitopes induced by receptor binding. J Virol. 1995;69:5723–5733. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5723-5733.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang X, Florin L, Farzan M, Kolchinsky P, Kwong P D, Sodroski J, Wyatt R. Modifications that stabilize human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein trimers in solution. J Virol. 2000;74:4746–4754. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4746-4754.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]