INTRODUCTION

Talking with adolescents who have a life-threatening or life-limiting illness is one of the most difficult tasks a health care provider (HCP) can undertake. In the past, medical providers, parents, and the public have thought that conversations about dying, advance care planning (ACP), and end-of-life discussions should be avoided with medically ill youth.1 This was due to a desire to protect children and adolescents or due to beliefs that they do not understand death and dying or do not have the capacity to make decisions about their own health. However, modern Western society has come to understand that these difficult conversations are not only often beneficial for patients and families but also are increasingly considered the standard of care. Today, the American Academy of Pediatrics,2 the Institute of Medicine,3 and the World Health Organization4 recommend involving youth in decisions regarding their health care decisions as they are developmentally and emotionally ready. This article focuses on the following:

Adolescents who have a life-limiting condition and their understanding of death,

Developmental considerations around health care decisions, and

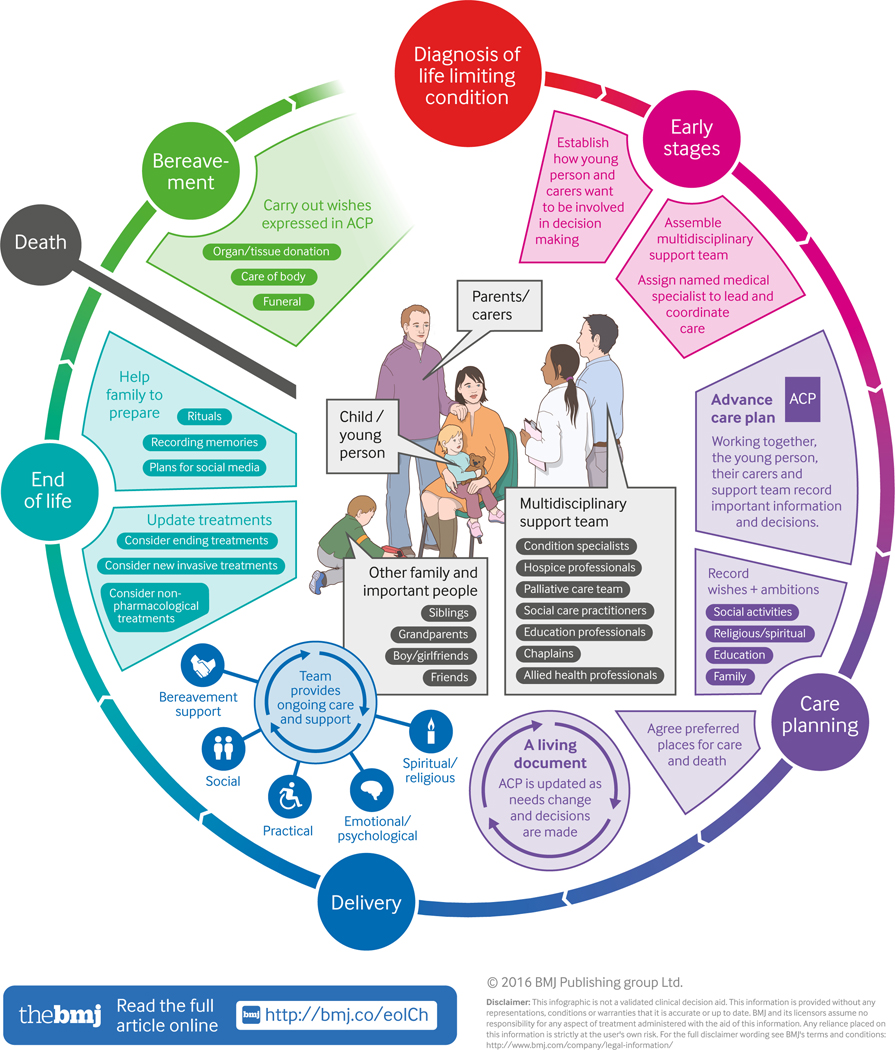

A practical approach to engaging adolescents in conversations around ACP, including addressing barriers to communication, especially at the end-of-life (Fig. 1).5

Fig. 1:

Visual summary: End of life care for children and young people

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

As recently as the 1970s, revealing a cancer diagnosis to a child was considered inhumane. Researchers believed that children and adolescents were not aware of their impending deaths and that the stigma of a cancer diagnosis should not be shared with them. However, as researchers began talking, drawing, and playing with children in hospitals, they began to notice that even sick young children were aware of their illness and would conceal knowledge of their impending death from their parents at the same time the parents were attempting to suppress any discussion about the child’s serious illness in the “maintenance of mutual pretense.”6, 7 By the early 2000s, a survey study by Kreicbergs and colleagues8 on parents who had lost a child to cancer in the 1990s showed that none of the group of parents who had talked with their child about death regretted it, but 27% who did not talk with their child about death regretted not having done so. Parents who had sensed their child was aware of imminent death were more likely to regret not talking than those who had not sensed awareness in their child. Mothers were more likely to regret than fathers, as were parents of older children compared with parents of younger children. Parents who had talked with their children were more likely to have sensed their child was aware of imminent death and were more often religious, older, and had older children. In addition, concurrent with major advances in medical technology and increased survivorship of many chronic childhood illnesses, such as sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis, cardiac anomalies, and childhood leukemia, a burgeoning movement for palliative care for the dying adolescent began taking place at pediatric hospitals and cancer programs.9, 10

HEALTH CARE PROVIDER READINESS

An individual’s own cultural and emotional experience with death will influence their ability and confidence in talking about dying with other people. Physicians and other HCPs frequently express uncertainty about how to address ACP, or involvement in medical decision-making throughout the course of the illness, primarily due to concerns about taking away hope from patients and their families. Therefore, a necessary and important first step in learning how to speak with adolescents about death or dying is assessing one’s own readiness to do so as a HCP.

HEALTH CARE PROVIDER READINESS

An individual’s own cultural and emotional experience with death will influence their ability and confidence in talking about dying with other people. Physicians and other HCPs frequently express uncertainty about how to address ACP, or involvement in medical decision-making throughout the course of the illness, primarily due to concerns about taking away hope from patients and their families. Therefore, a necessary and important first step in learning how to speak with adolescents about death or dying is assessing one’s own readiness to do so as a HCP.

Take a Self-Inventory

HCPs need to understand their personal feelings about death in order to be effective in providing support to adolescents who are facing their own impending death. HCPs are encouraged to take a self-inventory periodically throughout their medical education and practice to understand their own perception of death and its evolution over time as they mature. Each person’s experiences with death will inform the way they interact with others regarding death. This introspection can be done both formally and informally. In GRIEF, DYING, AND DEATH: CLINICAL INTERVENTIONS FOR CAREGIVERS (1984),11 Therese Rando provides exercises for self-assessment (Boxes 1 and 2).

Box 1 –. Early Experiences Influencing Reactions to Loss and Death

Our early experiences with loss and death leave us with messages, feelings, fears, and attitudes we will carry throughout life. To prevent our being controlled by our unconscious and conscious reactions to past experiences, it is important to recognize and state explicitly how these experiences have influenced us and our lifestyles.

Think about your earliest death-related experience:

When did it occur? Where was it? Who was involved? What happened?

What were your reactions, positive and negative?

What were you advised to do, and what did you do, to cope with the experience?

What did you learn about death and loss as result of this experience?

Of the things you learned then, what makes you feel fearful or anxious now?

Of the things you learned then, what makes it easier for you to cope with death now?

Think about your own feelings about death and the attitudes you maintain about it currently. Write down these feelings and attitudes.

The feelings and attitudes we have about death influence how we live all aspects of our lives. In what ways do your feelings and attitudes about death influence your own lifestyle and experience? (Do you defy death by being a daredevil? Do you deny death by avoiding wakes and funerals? Do you lessen the importance of death by espousing a religious promising eternal life? Do you attempt to accept death by being fatalistic?)

How do these feelings and attitudes about death affect how you currently cope with loss experiences, positively and negatively?

How does your interest in working with dying patients and the bereaved fit in with your issues related to death?

Box 2 –. Your Socio-Cultural, Ethnic, and Religious/Philosophical Attitudes Toward Death

Reflect on your upbringing and socialization. Think about areas such as afterlife; burial rites; expected attitudes of loved ones toward the dying person before and after death; expected attitude of the dying person; expected differences in reaction to death due to age or gender; meaning of death to life; attitude toward caregivers; or attitude toward telling children about death. Then note those attitudes held toward death by your social group, cultural group, ethnic group, and religious/philosophic group.

Which norms, mores, beliefs, sanctions, and attitudes have you internalized about death from these groups?

How do these ideas affect the ways in which you work with the terminally ill and the bereaved, positively and negatively?

As HCPs are only human, anticipatory grief of inevitable outcomes may lead to avoidance or lack of engagement with dying patients and their families. Self-awareness and self-monitoring of one’s own reactions (sometimes referred to as “countertransference”) are important areas to examine periodically if one is going to engage consistently in palliative care, especially with youth.12

Learn Communication Skills

Parents often do not talk to their child about what is happening in order to protect their child.13 Despite this, youth, especially adolescents, often know that they are very sick and/or dying. Withholding information about an adolescent’s medical status can cause them to suspect that they are more seriously ill, increase sibling suffering, strain the parental relationship, and jeopardize trust. Parents and practitioners alike can help adolescents feel less isolated by learning what their questions are and answering them concretely. Talking with the adolescent is a sensitive two-way process, where active listening is important—paying attention not only to what the adolescent says, but how they are saying it. Are their facial expressions congruent to the words coming out of their mouth? Are they looking away while speaking? Are they telling you they are not worried while complaining of headaches, stomachaches, and sleeplessness? It will be important to be aware of such nonverbal cues as they can provide insight into the adolescents’ experiences, thoughts, and feelings about their illness, thus facilitating further communication.

The truth, carefully put, is more helpful than a distortion or an evasion, which could cause a feeling of isolation or be misinterpreted. In a sample of 56 children with cancer, the children who received open information from their parents about their diagnosis and prognosis showed significantly less anxiety and depression.14 Providing information increases the child’s freedom to ask questions and express worries and reduces loneliness, alienation, and isolation.

The usual method of “see one, do one, teach one” may not be an effective way to prepare HCPs to discuss health care planning with youth who have life-limiting illnesses.15 Many clinicians report a lack of experience or formal training.16 Fortunately, in many hospitals, adolescents are generally healthy and death is rare. Therefore, ACP conversations may require more formal communication training; there are several programs available such as ComSkil,17 SPIKES,18 VitalTalk from the University of Washington (http://vitaltalk.org/),19 Education in Palliative & End-of-Life Care (EPEC) at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine (http://www.epec.net/),20 and Palliative Care Education and Practice (PCEP) at Harvard Medical School (http://www.hms.harvard.edu/pallcare/PCEP/PCEP.htm).21

Although open verbal communication is a productive and efficient way to increase patients’ and families’ understanding and make decisions about ACP, other ancillary services may help as well. Art, music, and play therapy can be used to assist with coping and communication. Child Life or Recreation Therapy Services may be used to introduce medical play and other age-appropriate activities to help explain procedures and gain mastery as well as provide recreation/diversion.

Understand Health Care Provider Barriers

HCPs face many barriers to talking to their patients about ACP, especially when talking about poor prognoses or end-of-life care. Common misconceptions in HCPs about discussing ACP include that talking about end-of-life will make it happen (magical thinking) and that it will increase rates of depression, threaten patients’ and families’ hope, and reduce rates of survival.22 In addition to these misconceptions, HCPs may also have reservations due to incomplete knowledge of the patient’s prognosis and difficulty handling the emotional nature of the news.22 However, research has suggested that prognosis IS NOT NECESSARY before initiating end-of-life care discussions.23

PATIENT AND FAMILY READINESS

After a HCP has explored their own thoughts about death and dying and has learned about communicating with adolescents on this difficult topic, the next step is to assess the patient’s readiness for the discussion. Adolescents and their families cope with terminal illness very differently. Productive conversations occur over time and are developmentally appropriate, culturally and religiously sensitive, and tailored to the specific child and family. There may be conflicts across beliefs within the family, between the family and the medical team, and within the medical teams about what information to share, treatments to pursue, and other difficult decisions. This is common and consultations from Psychiatry, Bioethics, and Palliative Care are often available to help clarify and facilitate communication around such conflicts.24

What Is Developmentally Appropriate?

Ensuring that the conversations are developmentally appropriate is critical to understanding how to talk to adolescents about death. The adolescent category can span from 12 to 24 years old, which includes individuals with a unique set of experiences in vastly different life stages. This poses a challenge for health care workers not well-versed in the spectrum of normal social, emotional, cognitive, and language skills in adolescent development. An understanding of typical adolescent development is crucial in order to identify emotional and behavioral problems.

Vignette 1

GR is a 15-year-old Hispanic female with a chronic immunodeficiency, recurrent infections and mild developmental delay. She fell behind in school starting in the 5th grade due to missing a lot of school secondary to illness and feeling tired all the time. She receives 1 hour twice a week home schooling to make up her school but at this rate she cannot catch up. Neuropsychological testing shows her full scale IQ to be 70 and her achievement to be at the 3rd grade level. While she has a hard time keeping up with her academic skills, she is friendly and talks readily about the clothes she wants and pop-stars and movies she likes. She is close to her mother who stays with her in the hospital for months at a time. She also has a 27-year-old brother with whom she is close and looks up to who is studying to be a policeman. She feels angry with her father who does not help her mother take care of her or the rest of the family. She reports he is verbally abusive to her, calling her ‘lazy’ and ‘stupid’. She is about the size of a 10-year-old due to her chronic illness.

Psychiatry is consulted initially to evaluate GR for anxiety and depression. She is tired of being in the hospital for several months because they are unable to get her infections under control. Eventually, it is clear, she is failing medically. Despite her “intellectual disability,” she is able to answer the question, “if you are too sick, who would you like to make your medical decisions?” She indicates that she wants her mother to make decisions if she is not able to participate. She would also like her brother to help her mother. She does not believe her father will act in her best interest because he has avoided visiting the hospital and has not been active in her home care. She is able to discuss what she is worried about for her mother after she dies.

Understanding of death as a concept

A person’s understanding about death includes understanding 4 general concepts: universality, irreversibility, nonfunctionality, and causality.25 Although every child learns these concepts in the context of their age, developmental stage, and environment, a complete understanding of death in most children generally emerges by 10 years old and current research suggests that much younger children understand concepts of death.26, 27 Living with a serious or terminal illness may cause youth to have an advanced understanding of death.28 Therefore, knowing that a patient may have a different conceptualization of what death means and understanding the patient’s beliefs are very important (Table 1).

Table 1.

Children’s understanding of death

| Concept of Death | Definition | Questions Youth Ask |

|---|---|---|

| Universality | All living things die | Does everyone die? Can anyone not die? |

| Irreversibility | Once dead, dead is forever | Does everyone have to die? How long do you stay dead? Do you/I have to die? What can I/we do to avoid death? When will you die? At any time? |

| Nonfunctionality | All functions of the body stop | What do you do when you are dead? Do you see? Hear? Smell? Feel? |

| Causality | What causes death | Why do people die? What caused my pet to die? Can you wish someone dead? “When mom said, ‘you’ll be the death of me one day’, is that why she died? |

| Afterwards | What happens next? Where does the soul go? My spirit? Will I come back to life again? Will I have hair in heaven? |

At different developmental stages, children will experience death as a physical separation or, alternatively, as a punishment that is perhaps temporary. As they get older and understand death is permanent, fear and regression remain common reactions. Adolescents often believe they are immortal despite the evidence before them and may take risks such as nonadherence to medication regimens or try smoking when they know they have cancer. These may be developmentally appropriate risk-taking behaviors, but the stakes are higher when they have a serious or life-threatening illness and pose challenges to themselves and the team caring for them. They often experience hospitalization and dying as a loss of privacy and independence. Denial can be a healthy defense in many cases but becomes dangerous when it interferes with treatment.

Decision-making of adolescents

The capacity to think abstractly and problem-solving abilities of adolescents are variable as many neurobiological systems mature fully.29 Increasingly, the treatment choices to be made carry implications for long-term development such as loss of fertility or cognitive abilities and fear of recurrence or second malignancies. In addition, there are 3 main developmental tasks of adolescents:

To establish independence from parents/family,

To form one’s identity, and

To create and sustain intimacy with a significant other.

These 3 tasks are often harder to achieve when one is chronically ill. Adolescents wish to be as “normal” as possible, fear rejection, and rely increasingly on peers for their identity, often trying on new and different personas. Being smaller or looking different or being sick and missing out on usual peer activities can disrupt an adolescent’s ability to become more independent or closer with peers at a particularly important time in development. Being able to ask for help and cultivate social support is one of the most critical factors in coping with setbacks and later successful transition to adulthood.30 As seen in Vignette 1, even adolescents with cognitive impairments and mild developmental delay may have sufficient capacity to choose a surrogate medical decision-maker.

A relatively safe place to start when talking with adolescents about their medical decision-making is by asking questions as in Box 3, preferably at an outpatient visit when the adolescent is medically stable.

Box 3 -. Decision-making questions for adolescents

“Has anyone talked with you about what you would like to happen if you become seriously ill in the future?”

“Is there someone you would like to help you make these decisions?”

“Who in your family? Who on your medical team or in the hospital?”

Individual personality factors

In addition to identifying where an adolescent is in the developmental understanding of death and dying, it is important to appreciate their personality and preferences. Individuals have their own preferences for how they like to receive information, and each type presents different challenges for health care planning and end-of-life discussions. For example, “monitors” are those individuals who seek detailed information, whereas “blunters” like to avoid anything but the most basic facts.31 HCPs should ask adolescents how much information they prefer to be given, from whom they prefer to receive information, and whether they prefer information to be provided verbally, in written form, or both ways.

In general, “monitors” will want more medical information, but then may be quite distressed by it and require considerable support with what they learn. “Blunters,” while wishing to avoid detailed medical information, may not have sufficient information to make informed decisions. Asking the following questions may help to assess preferences and thus prepare for any challenges (Box 4).

Box 4 -. Questions to assess preferences between monitors and blunters

“Are you someone who likes to know everything about what’s going to happen and when it will happen – the big picture? Or are you someone who likes to know a little bit at a time or, say, just before you need your blood taken, for example?”

“Does it help you to talk about things that are hard or are on your mind or are you someone who wants to work things alone?”

“What is the hardest thing for you right now?”

Contextual factors

There are vast cultural and ethnic differences in the preferences regarding treatment options, perceptions of death, and discussions about ACP and end-of-life care.32 Furthermore, religion and spirituality may influence perception of palliative care, coping, and end-of-life decision-making.33 Although religion and spirituality are often found to serve a protective or supportive role in coping with serious or terminal illness, each adolescent and family will cope differently.34 It is important to assess whether culture is why parents may be reluctant to communicate to their adolescent the severity of his or her condition. Always ask about each family’s basic cultural, ethnic, spiritual, and religious beliefs (Box 5).

Box 5 -. Assessing spirituality

“Can you tell me about your faith or spiritual beliefs?”

“Are there spiritual or religious practices you would like incorporated into your care?”

“Tell me how your family/community feels your adolescent’s illness should be handled.”

Language

Fundamental to communication is a shared language. Many HCPs identify language barriers as an obstacle to ACP with adolescents.35 Always use hospital interpretation services, rather than family or friends who speak the specific language, during ACP. Although a language barrier may not exist per se, patients and families may have vastly different levels of understanding of medical and legal terms or language. It is especially critical to clarify terms when thinking about having discussions with children and their families. Before ACP conversations, concepts of health and death literacy must be assessed.36 The Plain Language Planner for Palliative Care is a tool to help HCPs recognize and limit their use of medical jargon and thus increase patient health literacy.37

Family Adaption: Risk and Resilience Factors

Although ACP should be patient-focused, adolescents are situated within a social and family network that must also be considered. Family factors may influence the timing and manner of ACP conversations. Furthermore, understanding the psychosocial dynamics of the family system is crucial to patient-centered care. One useful tool, the Psychosocial Assessment Tool, assesses factors that place families and caregivers at risk, including structure/resources, family problems, social support, stress reactions, family beliefs, child problems, and sibling problems.38 These subscales build into the Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model, where families fall into 1 of 3 levels of overall psychosocial risk—universal, targeted, or clinical/treatment—and limited treatment resources are allocated according to risk level.38 In a study of 5 different chronic childhood medical conditions, Herzer and colleagues39 (2010) used the Family Assessment Device to assess family functioning. They found that risk factors include older child age, fewer children in the home, and lower socioeconomic status. Although many factors may contribute to how a family adapts to a chronic or terminal illness (Table 2), a family’s overall functioning plays a part in the pediatric patient’s well-being.40

Table 2.

Factors affecting family adaptation

| Predictors of Positive Family Adaptation | Predictors of Family and Caregiver Risk |

|---|---|

| • Family cohesion and flexibility • Ability to reorganize and balance demands of the illness with family needs and responsibilities • Clear family boundaries • Open and effective communication • Active coping • Strong spiritual belief system • Ability to seek social support from extended family, church, work place, community |

• Lone parenting with limited social support • Estranged or chronically conflicted relationships • Marital discord • Pre-existing medical and/or psychiatric problems • Socioeconomic vulnerabilities (unemployment, transportation, insurance) • Limited access to support • Cultural and language barriers, rigid religious belief system • Lack of consensus re: research, aggressive care • Climate of secrecy |

ENGAGING ADOLESCENTS IN ADVANCE CARE PLANNING

ACP refers to the process of HCPs talking about medical decisions in an open, honest, and comfortable manner, making themselves available to the adolescent and their families for an ongoing discussion around these issues. These conversations may not always be planned or necessarily lengthy once the relationship around and permission to talk about these topics is established early as safe topics to bring up. Otherwise, such conversations may not occur at all or happen too late when the adolescent is too ill to participate in a meaningful way.

In 2004, Himelstein and colleagues41 outlined 4 specific components to what is now referred to as ACP. First, there is identification of the decision-makers, including the adolescent; second, clarification of the patients’ and parents’ understanding of the illness and prognosis; third, establishment of care goals as curative, uncertain, or comfort care; and fourth, joint decision-making regarding use or nonuse of life-sustaining medical interventions such as mechanical ventilation, intravenous hydration, or phase I chemotherapy. Complicated and serious decisions such as these clearly take time and may evolve over the course of an illness as well.

Creating an Advance Care Planning Document

Voicing My CHOiCES™

Initial research with 52 adolescent and young adults (AYAs), aged 16 to 28 years, who were living with a life-threatening illness, such as human immunodeficiency virus infection or recurrent or metastatic cancer, showed that these AYA, although they might find it stressful, wanted to be able to participate in choosing the kind of medical treatment they wanted as well as to express their end-of-life wishes.42 Following this research, further adaptation of Five Wishes, an adult ACP guide, resulted in the development of VOICING MY CHOICES™: AN ADVANCED CARE PLANNING GUIDE FOR ADOLESCENTS & YOUNG ADULTS.43, 44, 45 The document allows patients to reflect on and record the following:

The kind of medical treatment they want and do not want,

How they would like to be cared for,

Information for their family and friends to know, and

How they would like to be remembered.

VOICING MY CHOICES™ became available to the public in November 2012. Moreover, VOICING MY CHOICES™ is written so HCPs can read parts of it verbatim to AYA in order to be more comfortable with end-of-life language. Each topic within the document can be presented, by a trusted medical team member, as a separate module starting with the sections addressing comfort or support. The modules do not have to be completed all in one sitting and should be tailored to the patients’ concerns at the time. Additional specific language and timing on how to initiate these difficult conversations using VOICING MY CHOICES™ are available.46 Since 2012, new Internet sites are available online to facilitate end-of-life conversations, although none are targeted to AYA (http://deathcafe.com/; http://deathoverdinner.org/; http://theconversationproject.org/; www.joincake.com/welcome/; www.dyingmatters.org/; www.begintheconversation.org/).

These documents serve as a guidepost for the adolescent’s desires for quality of life and may change over time as a disease progresses and additional treatments are unsuccessful. They are not legal documents for adolescents younger than 18 years and are mutable should the adolescent make new decisions as they gain a better understanding of their impending mortality.

Family-centered Advance Care Planning (FACE) intervention

Maureen Lyon and colleagues47 at Children’s National Health System developed an intervention for adolescents with chronic or terminal medical illness, consisting of a disease-specific ACP interview and completion of an advance directive. Although patients reported that these discussions prompted feelings of sadness, the patients and families involved in the intervention found it useful and helpful.48 There may be significant areas of discordance between youth and their families when considering timing of end-of-life medical decisions discussions, but in a randomized controlled trial of the ACP intervention versus sham intervention, there were higher rates of concordance between adolescent patients and their families following the pediatric ACP intervention.49, 50

ACP research is emerging to include other medical conditions as well, such as congenital heart disease, cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy and other neuromuscular diseases, and youth on long-term assisted ventilation.51, 52, 53, 54 The literature consistently demonstrates the need for ACP for youth with these serious medical conditions. However, further research is needed to understand the unique challenges that each population confronts and to develop valid interventions to foster these important discussions.

Vignette 2

LW is an 18-year-old with relapsed acute lymphocytic leukemia who had 2 failed bone marrow transplants and is admitted for experimental chemotherapy. He is legally allowed to make his own decisions, but he feels unprepared to do so. His parents have supported him throughout and do not want to talk about the possibility of a negative outcome.

Parents are willing to have LW complete an advance care document, but they do not want to be the ones to bring it up.

In his advance care plan, LW was able to tell the healthcare worker that he wanted a celebration of his life with a pizza party and that he wished to be buried wearing his favorite hockey team’s cap.

A CONVERSATION ABOUT ADVANCE CARE PLANNING INCLUDING END-OF-LIFE WISHES

When?

It is not easy to know when is best to initiate ACP conversations with patients and families. It requires a balancing act between the adolescent’s readiness and that of their family’s and, separately, the HCP’s readiness. If an HCP were to ask the following questions (Box 6) and the answer is “no” to each, then it might be time to consider initiating an ACP discussion.55 It is also helpful to check to see if the adolescent is prepared to open an end-of-life discussion, which can be probed using a readiness assessment by asking adolescents whether end-of-life conversations would be helpful or upsetting, and if they feel comfortable discussing preferences when treatment options become limited.42, 44, 46

Box 6 -. Questions to ask HCP to gauge readiness to discuss advance care planning

From Brook L, et al. A Plan for Living and a Plan for Dying: Advanced Care Planning for Children. Arch Dis Child 2008; 93 (suppl): A61–6; with permission.

Would you be surprised if this adolescent died prematurely due to a life-limiting illness?

Would you be surprised if this adolescent died within a year?

Would you be surprised if this child adolescent within this episode of care?

Do you know what the adolescent’s and family’s wishes are for the end-of-life?

Critical to the success of end-of-life discussions is identifying the adolescent’s personal beliefs, values, and goals, particularly as they relate to their quality of life. It is difficult to initiate an ACP discussion at the time of diagnosis or relapse because the adolescent and their family often does not hear or process much beyond the immediate bad news. While during hospitalization is a convenient time for HCPs to initiate ACP discussions, this time may not be opportune because the adolescent is likely to be regressed, stressed, and in a more dependent mode. Therefore, often the ideal time is during a routine outpatient visit when the adolescent is medically and emotionally stable. Understanding that a prognosis IS NOT NECESSARY before initiating such discussions is important.23 Developing a consistent message around openness to talking about the adolescent’s wishes and ambitions at regular intervals that an HCP can implement routinely may be helpful.

HCPs should demonstrate that communicating about end-of-life informs the adolescent and their family of the medical team’s goal to respect individual wishes and affirm the role of surrogate decision-making. If parents tell the medical team not to give an adolescent any medical information, it is important to review thoroughly the family history and religious, spiritual, or cultural beliefs. Further exploration and discussion with parents regarding their discomfort and reluctance about open communication with their adolescent can be helpful. In some cultures where disclosure and transparency are not the norm, the team may have to respect the family’s wishes against their personal wishes. The medical team should explain that if an adolescent asks a question that the team is constrained from answering, the adolescent will be told that their parents have asked them not to answer that question and that the adolescent should discuss it with the parents. In this situation, the team may consider discussions with other family members (with parental and patient permission) and religious counselors of the same faith, or request for an ethics consultation.

Sometimes an adolescent will be ready to stop pursing treatment after a long course of illness. It may be appropriate to have a psychiatric consultation when the adolescent reports a desire to stop the treatment, that they are “tired”, or that they “don’t care anymore,” for example, to rule out any depression or anxiety disorder that may respond to treatment. In contrast, the psychiatry consultant may point out the adolescent has no psychiatric disorder, has capacity for medical decision-making, and should be supported in their wishes.

Vignette 3

DM is a 16-year-old male who was first diagnosed with osteosarcoma when he was 12 years old. After 5 years of treatment with chemotherapy, surgical resection of metastatic lung nodules on 2 separate occasions, and a third relapse of multiple metastatic pulmonary and bony lesions, DM reports he is “tired” of treatments. He has spent a significant part of the past 5 years in the hospital. His primary caretaker is his maternal grandfather. Psychiatry is consulted to evaluate for depression, and the consultant determines that the DM is not depressed and has capacity to make medical decisions.

DM participates in his medical decision-making and indicates he wants his grandfather to make his medical decisions when he is not able. He trusts his grandfather knows what he wants. DM wants intubation if he has something that can be treated but he does not want to be kept alive if there is no chance of his improving to have significant quality of life.

Who?

Although ACP conversations should be patient-centered and focused on the wishes of the adolescent, there are often several other important individuals and medical services that may need to be included. Ask about who else is involved in the care of the patient and family (eg, pediatric palliative care service, religious or spiritual services, a special physical therapist, a psychologist or consultation psychiatrist etc.).56 If working together with a trusted medical team member or other service team on VOICING MY CHOICES™, adolescents may complete some sections independently, but it is highly recommended that they work alongside a HCP, particularly when making decisions about life support treatments.

What?

Despite being young, adolescents with terminal or life-threatening illness do think about what will happen after their death, and they are able to make concrete decisions about their preferences. When working with an advanced care planning document, adolescents and young adults demonstrate greater interest in discussing and documenting preferences about how they will be treated and remembered, rather than medical or legal technicalities.42 As part of the ACP, adolescents can voice preferences about type of service (funeral, memorial service, or celebration of life), treatment of their body (burial, cremation, organ donor, donation to science, autopsy), and publicity (open or closed casket).43 They can make decisions about the arrangements of the service (clothing, food, music, readings), the distribution of their belongings, and request future celebrations in their memory.43 Allowing these decisions to be made by participating adolescents serves to empower and respect them.

SUMMARY

Talking with adolescents about death and dying is a challenging but powerful and rewarding experience. During the process, most HCPs learn, not only about themselves, but also about the resilience and fortitude that these youths who are coping with severe illnesses and difficult circumstances have to teach us. Open communication can alleviate anxiety and distress by allowing adolescents the ability to express their preferences and helping parents and HCPs make informed decisions while potentially improving the adolescent’s quality of life.

Key Points.

Talking with adolescents who have a life-threatening or life-limiting illness is one of the most difficult tasks a healthcare provider can undertake.

A necessary and important first step in learning how to speak with adolescents about death or dying is assessing one’s own readiness as a healthcare provider (HCP).

Adolescents want to be included in medical decision making through the illness trajectory including making decisions around end-of-life.

Prognosis is not necessary before initiating advance care planning discussions.

Synopsis.

This chapter describes the preparation, rationale, and benefits of talking with adolescents who have life-threatening or life-limiting illness about advance care planning (ACP) and end-of-life concerns in a developmentally sensitive manner. The first step is to ensure that a healthcare provider is ready to work with adolescents in ACP discussions by taking a self-inventory, learning communication skills, and understanding individual barriers. Authors then outline how to assess patient and family readiness, including developmental, cultural, personal, and psychosocial considerations. Evidence-based techniques for respectfully and productively engaging adolescents in ACP conversations are discussed.

Footnotes

disclosure statement

No disclosures.

Contributor Information

Maryland Pao, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Margaret Rose Mahoney, Office of the Clinical Director, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perkins HS. Controlling death: the false promise of advance directives. Ann Intern Med 2007;147(1): 51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics: Palliative care for children. Pediatric 2000;106:351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families (2003), The National Academies Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. (2012). Persisting pain in children package: WHO guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of persisting pain in children with medical illnesses. Geneva: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44540 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villanueva G, Murphy MS, Vickers D, Harrop E, Dworzynski K. End of life care for infants, children and young people with life limiting conditions: summary of NICE guidance. Bmj. 2016. Dec 8;355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waechter EH. Children’s Awareness of Fatal Illness. The American Journal of Nursing 1971;71(6): 1168–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bluebond-Langner M. (1980). The private worlds of dying children. Princeton: Princeton U.P. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, Henter JI, Steineck G. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004. Sep 16;351(12):1175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freyer DR. Care of the Dying Adolescent. Pediatrics 2004;113:381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurwitz C Duncan J, Wolfe J. Caring for the child with cancer at the close of life. JAMA 2004;2992 (17):2141–2149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rando TA (1984). Grief, dying, and death: Clinical interventions for caregivers. Champaign, Ill: Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schonfeld DJ, Demaria T. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Disaster Preparedness Advisory Council. Supporting the Grieving Child and Family. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breyer J (2014). Talking to children and adolescents In L L Wiener, Pao M, Kazak A, Kupst MJ, Patenaude A (eds.), Quick Reference for Pediatric Oncology Clinicians: The Psychiatric and Psychological Dimensions of Pediatric Cancer Symptom Management, 2nd ed, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Last BF & van Veldhuizen AM. Information about diagnosis and prognosis related to anxiety and depression in children with cancer aged 8–16 years. Eur J Cancer 1996;32(2):290–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feraco AM, Brand SR, Mack JW, et al. Communication skills training in pediatric oncology: moving beyond role modeling. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Epub 2016. Jan 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanderson A, Hall AM, Wolfe J. Advance Care Discussions: Pediatric Clinician Preparedness and Practices. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(3):520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banerjee SC, Bialer PA, Levin TT, Maloney EK, D’Agostino TA. Communication skills training for oncology professionals. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1242–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES—A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: Application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000;5:302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VitalTalk. (n.d.). Retrieved April, 2018, from http://vitaltalk.org/

- 20.Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care. (n.d.). Retrieved April, 2018, from http://www.epec.net/

- 21.Multidisciplinary training for professionals. (n.d.). Retrieved April, 2018, from http://www.hms.harvard.edu/pallcare/PCEP/PCEP.htm

- 22.Mack JW & Smith TJ. Reasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improved. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(22):2715–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldman E & Wolfe J. Palliative care for children with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(2):100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muriel AC, Wolfe J, Block SD. Pediatric Palliative Care and Child Psychiatry: A Model for Enhancing Practice and Collaboration. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(10):1032–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenyon BL. Current research in children’s conceptions of death: a critical review. OMEGA. 2001;43:63–91 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bates AT & Kearney JA. Understanding death with limited experience in life: dying children’s and adolescents’ understanding of their own terminal illness and death. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2015;9(1):40–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luby J, Belden A, Sullivan J, Hayden R, McCadney A, & Spitznagel E. Shame and guilt in preschool depression: evidence for elevations in self-conscious emotions in depression as early as age 3. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2009;50(9):1156–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jay SM, Green V, Johnson S, et al. Differences in death concepts between children with cancer and physically healthy children. J Clin Child Psychol. 1987;16:301–306. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mills KL1, Goddings AL, Clasen LS, Giedd JN, Blakemore SJ. The developmental mismatch in structural brain maturation during adolescence. Dev Neurosci. 2014;36(3–4):147–60. doi: 10.1159/000362328. Epub 2014 Jun 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pao M. Conceptualization of success in young adulthood. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017. Apr;26(2):191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller SM. Monitoring and blunting: validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threat. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(2):345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohr S, Jeong S, & Saul P. Cultural and religious beliefs and values, and their impact on preferences for end-of-life care among four ethnic groups of community-dwelling older persons. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(11–12):1681–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinberg Steven M. Cultural and religious aspects of palliative care. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2011;1(2):154–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.López-Sierra HE, Rodríguez-Sánchez J. The supportive roles of religion and spirituality in end-of-life and palliative care of patients with cancer in a culturally diverse context: a literature review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2015;9(1):87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies B1, Sehring SA, Partridge JC, Cooper BA, Hughes A, Philp JC, Amidi-Nouri A, Kramer RF. Barriers to palliative care for children: perceptions of pediatric health care providers. Pediatrics. 2008. Feb;121(2):282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayes B, AM Fabri, Coperchini M, Parkar R, Austin-Crowe Z. Health and death literacy and cultural diversity: insights from hospital-employed interpreters. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017. Jul 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wittenberg E, Goldsmith J, Ferrell B, Platt CS. Enhancing Communication Related to Symptom Management Through Plain Language. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(5):707–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kazak AE, Schneider S, Didonato S, Pai AL. Family psychosocial risk screening guided by the Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model (PPPHM) using the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT). Acta Oncol 2015;54(5):574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herzer M, Godiwala N, Hommel KA, Driscoll K, Mitchell M, Crosby LE, Piazza-Waggoner C, Zeller MH, and Modi AC. Family Functioning in the Context of Pediatric Chronic Conditions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010; 31(1): 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leeman J, Crandell JL, Lee A, Bai J, Sandelowski M, Knafl K. Family Functioning and the Well-Being of Children With Chronic Conditions: A Meta-Analysis. Res Nurs Health. 2016;39(4):229–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Morstad Boldt A, et al. Pediatric palliative care. New Engl J Med 2004;350:1752–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiener L, Ballard E, Brennan T, Battles H, Martinez P, Pao M. How I wish to be remembered: the use of an advance care planning document in adolescent and young adult populations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(10):1309–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.“Five Wishes.” Aging with Dignity, 2018, www.agingwithdignity.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiener L, Zadeh S, Battles H, Baird K, Ballard E, Osherow J, Pao M. Allowing Adolescents and Young Adults to Plan Their End-of-Life Care. Pediatrics; October 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiener L, Zadeh S, Wexler L, et al. (2013). When silence is not golden: Engaging adolescents and young adults in discussions around end-of-life care. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 60, 715–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zadeh S, Pao M, & Wiener L. Opening end-of-life discussions: how to introduce using Voicing My Choices, an advance care planning guide for adolescents and young adults. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(3):591–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kimmel AL, Wang J, Scott RK, Briggs L, Lyon ME. Family Centered (FACE) advance care planning: Study design and methods for a patient-centered communication and decision-making intervention for patients with HIV/AIDS and their surrogate decision-makers. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;43:172–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dallas RH, Kimmel A, Wilkins ML, Rana S, Garcia A, Cheng YI, Wang J, Lyon ME. Acceptability of Family-Centered Advanced Care Planning for Adolescents With HIV. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyon ME, Dallas RH, Garvie PA, Wilkins ML, Garcia A, Cheng YI, Wang J. Paediatric advance care planning survey: a cross-sectional examination of congruence and discordance between adolescents with HIV/AIDS and their families. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lyon ME, D’Angelo LJ, Dallas RH, Hinds PS, Garvie PA, Wilkins ML, Garcia A, Briggs L, Flynn PM, Rana SR, Cheng YI, Wang J. A randomized clinical trial of adolescents with HIV/AIDS: pediatric advance care planning. AIDS Care. 2017;29(10):1287–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tobler D, Greutmann M, Colman JM, Greutmann-Yantiri M, Librach SL, Kovacs AH. Knowledge of and preference for advance care planning by adults with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(12):1797–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kazmerski TM, Weiner DJ, Matisko J, Schachner D, Lerch W, May C, Maurer SH. Advance care planning in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: A quality improvement project. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016;51(12):1304–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiscock A, Kuhn I, Barclay S. Advance care discussions with young people affected by life-limiting neuromuscular diseases: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edwards JD, Kun SS, Graham RJ, Keens TG. End-of-life discussions and advance care planning for children on long-term assisted ventilation with life-limiting conditions. J Palliat Care 2012;28(1):21–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brook L. et al. (2008) A Plan for Living and a Plan for Dying: Advanced Care Planning for Children; Arch Dis Child 2008; 93 (suppl): A61–A66 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Child Buxton D. and adolescent psychiatry and palliative care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54:791–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]