Abstract

Background

Preterm birth, defined as birth between 20 and 36 completed weeks, is a major contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality globally. Oxytocin receptor antagonists (ORA), such as atosiban, have been specially developed for the treatment of preterm labour. ORA have been proposed as effective tocolytic agents for women in preterm labour to prolong pregnancy with fewer side effects than other tocolytic agents.

Objectives

To assess the effects on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes of tocolysis with ORA for women with preterm labour compared with placebo or any other tocolytic agent.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (1 December 2013).

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials (published and unpublished) of ORA for tocolysis of labour between 20 and 36 completed weeks' gestation.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently evaluated methodological quality and extracted trial data. When required, we sought additional data from trial authors. Results are presented as risk ratio (RR) for categorical and mean difference (MD) for continuous data with the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where appropriate, the number needed to treat for benefit (NNTB) and the number needed to treat for harm (NNTH) were calculated.

Main results

This review update includes eight additional studies (790 women), giving a total of 14 studies involving 2485 women.

Four studies (854 women) compared ORA (three used atosiban and one barusiban) with placebo. Three studies were considered at low risk of bias in general (blinded allocation to treatment and intervention), the fourth study did not adequately blind the intervention. No difference was shown in birth less than 48 hours after trial entry (average RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.15 to 7.43; random‐effects, (two studies, 152 women), perinatal mortality (RR 2.25, 95% CI 0.79 to 6.38; two studies, 729 infants), or major neonatal morbidity. ORA (atosiban) resulted in a small reduction in birthweight (MD ‐138.86 g, 95% CI ‐250.53 to ‐27.18; two studies with 676 infants). In one study, atosiban resulted in an increase in extremely preterm birth (before 28 weeks' gestation) (RR 3.11, 95% CI 1.02 to 9.51; NNTH 31, 95% CI 8 to 3188) and infant deaths (up to 12 months) (RR 6.13, 95% CI 1.38 to 27.13; NNTH 28, 95% CI 6 to 377). However, this finding may be confounded due to randomisation of more women with pregnancy less than 26 weeks' gestation to atosiban. ORA also resulted in an increase in maternal adverse drug reactions requiring cessation of treatment in comparison with placebo (RR 4.02, 95% CI 2.05 to 7.85; NNTH 12, 95% CI 5 to 33). No differences were shown in preterm birth less than 37 weeks' gestation or any other adverse neonatal outcomes. No differences were evident by type of ORA, although data were limited.

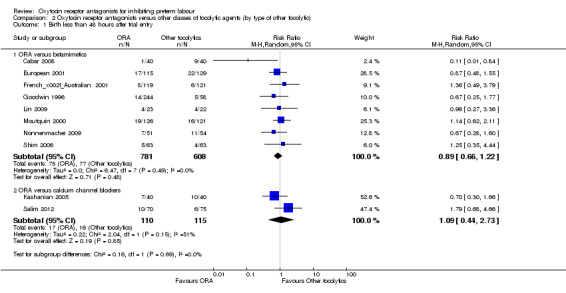

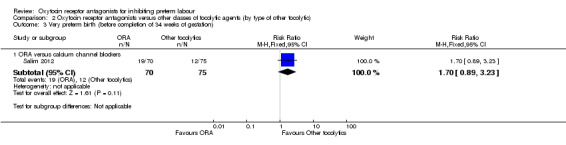

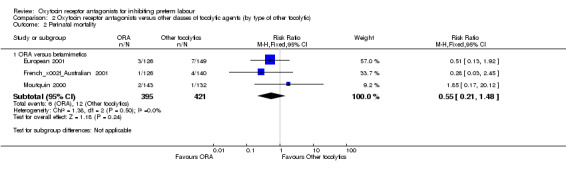

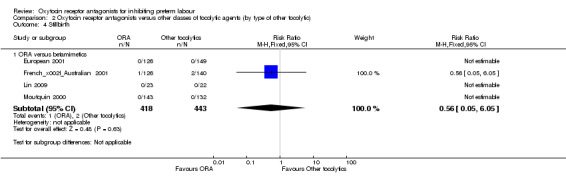

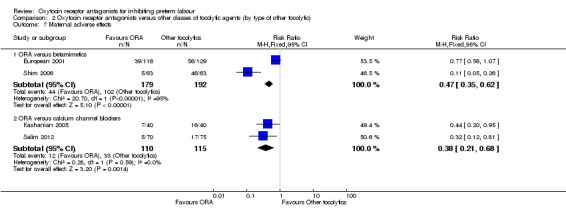

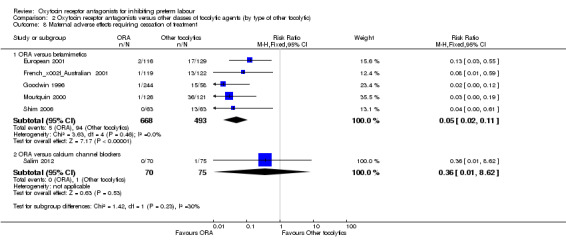

Eight studies (1402 women) compared ORA (atosiban only) with betamimetics; four were considered of low risk of bias (blinded allocation to treatment and to intervention). No statistically significant difference was shown in birth less than 48 hours after trial entry (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.22; eight studies with 1389 women), very preterm birth (RR 1.70, 95% CI 0.89 to 3.23; one study with 145 women), extremely preterm birth (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.92; one study with 244 women) or perinatal mortality (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.48; three studies with 816 infants). One study (80 women), of unclear methodological quality, showed an increase in the interval between trial entry and birth (MD 22.90 days, 95% CI 18.03 to 27.77). No difference was shown in any reported measures of major neonatal morbidity (although numbers were small). ORA (atosiban) resulted in less maternal adverse effects requiring cessation of treatment (RR 0.05, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.11; NNTB 6, 95% CI 6 to 6; five studies with 1161 women).

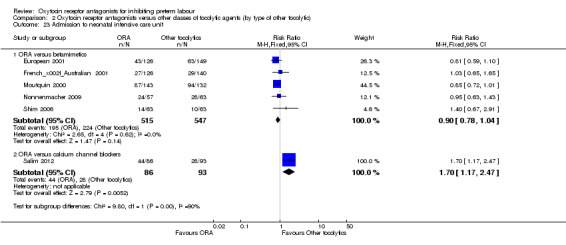

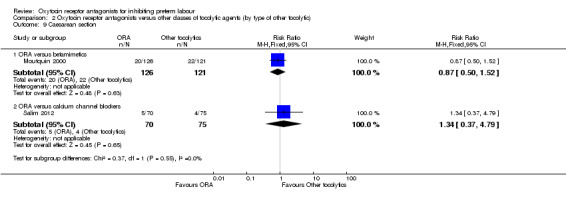

Two studies including (225 women) compared ORA (atosiban) with calcium channel blockers (CCB) (nifedipine only). The studies were considered as having high risk of bias as neither study blinded the intervention and in one study it was not known if allocation was blinded. No difference was shown in birth less than 48 hours after trial entry (average RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.73, random‐effects; two studies, 225 women) and extremely preterm birth (RR 2.14, 95% CI 0.20 to 23.11; one study, 145 women). No data were available for the outcome of perinatal mortality. One small trial (145 women), which did not employ blinding of the intervention, showed an increase in the number of preterm births (before 37 weeks' gestation) (RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.14; NNTH 5, 95% CI 3 to 19), a lower gestational age at birth (MD ‐1.20 weeks, 95% CI ‐2.15 to ‐0.25) and an increase in admission to neonatal intensive care unit (RR 1.70, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.47; NNTH 5, 95% CI 3 to 20). ORA (atosiban) resulted in less maternal adverse effects (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.68; NNTB 6, 95% CI 5 to 12; two studies, 225 women) but not maternal adverse effects requiring cessation of treatment (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.62; one study, 145 women). No longer‐term outcome data were included.

Authors' conclusions

This review did not demonstrate superiority of ORA (largely atosiban) as a tocolytic agent compared with placebo, betamimetics or CCB (largely nifedipine) in terms of pregnancy prolongation or neonatal outcomes, although ORA was associated with less maternal adverse effects than treatment with the CCB or betamimetics. The finding of an increase in infant deaths and more births before completion of 28 weeks of gestation in one placebo‐controlled study warrants caution. However, the number of women enrolled at very low gestations was small. Due to limitations of small numbers studied and methodological quality, further well‐designed randomised controlled trials are needed. Further comparisons of ORA versus CCB (which has a better side‐effect profile than betamimetics) are needed. Consideration of further placebo‐controlled studies seems warranted. Future studies of tocolytic agents should measure all important short‐ and long‐term outcomes for women and infants, and costs.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Infant, Newborn; Pregnancy; Albuterol; Albuterol/therapeutic use; Infant, Extremely Low Birth Weight; Obstetric Labor, Premature; Obstetric Labor, Premature/drug therapy; Oligopeptides; Oligopeptides/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Receptors, Oxytocin; Receptors, Oxytocin/antagonists & inhibitors; Ritodrine; Ritodrine/therapeutic use; Terbutaline; Terbutaline/therapeutic use; Tocolytic Agents; Tocolytic Agents/therapeutic use; Vasotocin; Vasotocin/analogs & derivatives; Vasotocin/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Oxytocin receptor antagonists for inhibiting preterm labour

Tocolytic drugs suppress preterm labour and have the potential to postpone preterm birth long enough to, hopefully, improve infant outcome. This may be by allowing normal growth and maturation of the baby, or by allowing time for administration of magnesium sulphate to reduce risk of cerebral palsy and corticosteroids to help the baby's lungs and other organs to mature. They may also provide the opportunity, if necessary, for the mother to be transferred to a hospital that has facilities to provide neonatal intensive care. However, prolonging pregnancy may instead have adverse outcomes for the baby and so it is important to assess infant outcomes alongside duration of pregnancy. Oxytocin receptor antagonists (ORAs) are a group of tocolytic drugs, and we undertook this review to see if ORAs prolonged pregnancy and improved outcomes for infants compared with no treatment or with other tocolytic drugs.

The tocolytic drugs, atosiban and barusiban, were the only ORAs we found that had been studied in trials; some trials compared with no treatment and others compared atosiban with betamimetics (another group of tocolytic drugs). We identified 14 studies, involving 2485 women. We found that, although atosiban resulted in fewer maternal side effects than other tocolytic drugs (especially betamimetics), atosiban was not effective in delaying or preventing preterm birth or improving neonatal outcome, and may possibly contribute to poorer infant outcomes. Further well‐designed studies would be helpful, especially in women with threatened preterm at low gestations where preterm birth puts babies at particularly high risk of death or disability.

Atosiban is no better than placebo or other drugs in delaying or preventing preterm birth but it has fewer maternal side effects compared to other tocolytics.

Background

Description of the condition

Preterm birth, defined as birth occurring between 20 and 36 completed weeks, is a major contributor to perinatal mortality and morbidity (Liu 2012; WHO 2012). Worldwide, it is estimated that more than one in 10 births is preterm, affecting 15 million babies annually (Blencowe 2012; WHO 2012). The incidence of preterm birth is 8.6% of births in high‐resource countries, and between 7.4% to 13.3% in low‐resource countries, and rose in both at least until the middle of the last decade (Chang 2013; WHO 2012).

In high‐income countries, very preterm birth (i.e. birth before 32 weeks' gestation) has an incidence of 1% to 2% (Tucker 2004) but despite the availability of perinatal and neonatal care, it is responsible for approximately one third to one half of all perinatal deaths (Dorling 2008; Zeitlin 2008). In high‐income countries, almost 95% of neonates born between 28 and 32 weeks' gestation will survive, with more than 90% surviving without impairment. In contrast, in many low‐income countries, only 30% of neonates born between 28 and 32 weeks will survive (WHO 2012).

Preterm birth is associated not only with high immediate costs attributable to neonatal intensive care, but also with substantial long‐term costs, including costs for special education (Petrou 2011), and other services for infants and children with intellectual and physical disability (Petrou 2011). In addition to the lengthy neonatal intensive care treatment required for many preterm infants, preterm birth often places stress on parents, which is greater with decreasing gestational age (Schappin 2013).

Approximately 65% to 70% are spontaneous preterm births either following spontaneous preterm labour (40% to 45%) and those following preterm rupture of membranes (25% to 30%) (Goldenberg 2008). While the cause of spontaneous preterm birth is often unclear, some risk factors have been identified including: maternal age (adolescence and advanced age); history of preterm birth; race; multiple pregnancy, short inter‐pregnancy interval; infections; medical conditions; poor nutrition; psychological factors and genetic predisposition (Goldenberg 2008; Plunkett 2008).

There has been little progress in reducing the incidence of preterm birth, even in high‐income countries despite intensive antenatal care programs aimed at high‐risk groups, the widespread use of pharmacological agents to inhibit preterm birth (tocolytics) and other preventive and therapeutic interventions. Nevertheless, short‐term prolongation of pregnancy has the potential to allow other interventions to improve outcomes, including maternal corticosteroid administration to accelerate maturation of fetal lungs (Roberts 2006) and other organs (Crowley 1996), magnesium sulphate administration to reduce risk of cerebral palsy (Doyle 2009) and maternal transfer before birth to a centre that can provide appropriate neonatal special or intensive care (Lasswell 2010). For these reasons, short‐term tocolytic therapy is commonly used to inhibit preterm labour and postpone preterm birth.

Description of the intervention

A range of tocolytic agents that have been used to inhibit preterm labour are the topics of Cochrane systematic reviews including: nitric oxide donors (glyceryl trinitrate) (Duckitt 2002), calcium channel blockers (CCB) (commonly nifedipine) (update of King 2003 in progress), betamimetics (Anotayanonth 2006), magnesium sulphate (Crowther 2002), cyclo‐oxygenase (COX) inhibitors (Khanprakob 2012) and progesterone (Su 2010). The betamimetics (ritodrine, salbutamol and terbutaline) have been shown to be effective in delaying delivery by seven days and longer, although no impact has yet been shown on perinatal mortality (Anotayanonth 2006; Gyetvai 1999; King 1988). Furthermore, betamimetics have a high frequency of unpleasant, sometimes severe maternal side effects including tachycardia, hypotension, tremor and a range of biochemical disturbances, and they have been associated with life‐threatening cardiovascular and respiratory events and deaths (FDA 2011). Compared with other tocolytic agents (mostly betamimetics), CCB prolonged pregnancy and improved short‐term neonatal outcomes, with fewer maternal adverse effects (update of King 2003 in progress). However, a fifth of women still delivered within 48 hours of CCB treatment, and nearly a third within seven days, so there is still a need for other safe, effective tocolytic agents, particularly at very early gestations.

A number of oxytocin receptor antagonists have been developed, and of these, three, atosiban, barusiban and retosiban have been investigated in humans as tocolytic agents. To date, only atosiban is in use outside of clinical trials. Atosiban is an oxytocin receptor antagonist which was specifically developed for the treatment of preterm labour (Melin 1994). Early reports of the use of atosiban for tocolysis showed promise both in vitro and in animal studies, and preliminary studies in pregnant and non‐pregnant humans suggested a very low incidence of maternal side effects (Goodwin 1996b; Goodwin 1998b). Potential maternal side effects include adverse injection site reaction, nausea, vomiting, headache, chest pain and hypotension (Moutquin 2000; Tsatsaris 2004).

How the intervention might work

Oxytocin is a peptide hormone produced in the pituitary, uterus, placenta and amnion. It has a variety of functions, which include stimulating myometrial activity (uterine contractions) as part of the pathway to normal and preterm labour. It binds receptors on myometrial cells, activating several intracellular pathways, which include protein kinase C phosphorylation of various proteins and a rise in intracellular calcium ions, both from intracellular stores via a GTP/phospholipase/inositol phosphate pathway and by activating voltage gated membrane channels allowing entry of extracellular calcium ions. Calcium ion binding to calmodulin then activates myosin light chain kinase, causing myometrial muscle contraction (Vrachnis 2011).

The oxytocin receptor antagonist, atosiban, is a peptide analogue of oxytocin that binds oxytocin receptors in the myometrial cell membrane, preventing the oxytocin‐induced rise in intracellular calcium and leading to relaxation of the myometrium (Melin 1994). Atosiban is an antagonist with high affinity to both the vasopressin receptor (V1a) and oxytocin receptor (Akerlund 1999).

Goodwin 1994 first described in 1994 the use of atosiban in humans for tocolysis. A previous review suggested that oxytocin antagonists could be effective and safe in preterm labour (Coomarasamy 2003). It has not been established whether the tocolytic effects of atosiban is due to its oxytocin or vasopressin receptor antagonist properties.

Barusiban is a selective oxytocin receptor antagonist with its effect on the vasopressin receptor (Nilsson 2003). Both atosiban and barusiban have a molecular structure very similar to the oxytocin molecule (a nonapeptide) (Vrachnis 2011). However, as peptide antagonists lack oral bioavailability, development of novel non‐peptide compounds with high oxytocin receptor selectivity is currently ongoing. Non‐peptides such as retosiban are small molecules, structurally not related to oxytocin (Borthwick 2013). It is currently not established how the molecular structure affects signalling pathways. It is plausible that the tocolytic effects of nonapeptides may differ from non‐peptide compounds based on their different binding affinity and selectivity to oxytocin receptors and also other receptors (Borthwick 2013; Vrachnis 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

Preterm labour is often insidious in onset and difficult to anticipate, and the causes are likely to be multifactorial, so prevention by treating the underlying causes has proved elusive. Therefore, effective tocolysis in suspected or established preterm labour is likely to remain critical to reducing infant morbidity and mortality associated with preterm birth, and to mitigating the long‐term consequences of prematurity on developmental and health outcomes. Since oxytocin receptor antagonists have undergone clinical trials and are available in some countries for the management of women in preterm labour, this updated review is important to assist clinicians and women in informed decision making about which tocolytic to use.

Objectives

Primary objectives of the review

To assess the effects on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes of any oxytocin receptor antagonist administered as a tocolytic agent to women in preterm labour when compared with placebo.

To assess the effects on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes of any oxytocin receptor antagonist administered as a tocolytic agent to women in preterm labour when compared with other classes of tocolytic agents.

Secondary objective

A secondary objective of the review is to determine whether the effects of oxytocin receptor antagonists, when compared with placebo or any other tocolytic agent, are influenced by different population characteristics and duration of tocolytic therapy as follows: (i) women randomised before 28 weeks' gestation versus those randomised at 28 weeks or after; (ii) women with ruptured membranes at randomisation versus women with intact membranes; (iii) women with a singleton pregnancy versus women with a multiple pregnancy; (iv) women who received maintenance therapy* versus women who did not; and also by type of tocolytic agent as follows: (v) type of other tocolytic; betamimetics versus calcium channel blockers (CCB); (vi) type of oxytocin receptor antagonists (ORA); atosiban versus other ORA.

(*Use of continued tocolytic agents after successful suppression of threatened preterm labour.)

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised and cluster‐randomised studies in which oxytocin receptor antagonists were used for tocolysis in the management of preterm labour. Studies using quasi‐random methods of allocation and cross‐over studies were excluded.

Types of participants

Women assessed as being in preterm labour (between 20 and 36 completed weeks' gestation) and considered suitable for tocolysis.

Types of interventions

Oxytocin receptor antagonists administered as a tocolytic by any route compared with placebo.

Oxytocin receptor antagonists administered as a tocolytic by any route compared with other classes of tocolytic agents.

Types of outcome measures

This review aimed to assess the effects of oxytocin receptor antagonists on clinically relevant outcome measures relating to perinatal and infant short‐term and long‐term outcome as well as prolongation of pregnancy. Furthermore, maternal side effects and outcomes were also examined.

Clinically relevant outcomes for trials of tocolysis for inhibiting preterm labour have been prespecified following consultation with the editors and authors of the individual reviews.

Consensus was reached on a set of six ‘core’ outcomes, which are highlighted below. These will be included in all tocolysis reviews. In addition to these core outcomes, individual teams may include other outcomes as necessary.

Primary outcomes

Short‐term and long‐term serious infant outcome determined by the presence of any of the following.

Serious maternal outcome (defined as death, cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest, admission to intensive care unit).

Birth less than 48 hours after trial entry.

Serious infant outcome (defined as death or chronic lung disease [need for supplemental oxygen at 28 days of life or later], grade three or four intraventricular haemorrhage or periventricular leukomalacia, major neurosensory disability (defined as any of legal blindness, sensorineural deafness requiring hearing aids, moderate or severe cerebral palsy, or developmental delay/intellectual impairment [defined as developmental quotient (DQ) or intelligence quotient (IQ) less than 2 standard deviations below mean])).

Perinatal mortality (stillbirth defines as a birth not showing signs of life defined by any gestational age and birthweight in the trials and neonatal death up to 28 days).

Very preterm birth (before completion of 34 weeks of gestation).

Secondary outcomes

These include other measures of effectiveness, complications and health service use.

Maternal

Maternal adverse effects.

Maternal adverse effects requiring cessation of therapy.

Caesarean section.

Antepartum haemorrhage.

Postpartum haemorrhage.

Satisfaction with care.

Quality of life after the birth (measured by validated instruments).

Infant/child

Extremely preterm birth (before completion of 28 weeks of gestation).

Preterm birth (before completion of 37 weeks of gestation).

Preterm neonate delivered with full course of antenatal steroids.

Interval between trial entry and birth.

Gestational age at birth.

Birthweight.

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes.

Respiratory distress syndrome.

Use of mechanical ventilation.

Duration of mechanical ventilation.

Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the neonate.

Intraventricular haemorrhage.

Necrotising enterocolitis.

Retinopathy of prematurity.

Neonatal jaundice.

Neonatal sepsis.

Infant death.

Quality of life in childhood (measured by validated instruments).

Health service use

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

Neonatal length of hospital stay.

Maternal length of hospital stay.

In this update, primary and secondary outcomes measures were revised to enhance consistency across Cochrane tocolytic reviews and to better reflect important outcome measures.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (1 December 2013).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of Embase;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Studies identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the studies identified in the previous version of this review, see Appendix 1.

For this update, we used the following methods when assessing all new and previously included studies.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed all potential studies identified from the search strategy for inclusion in this review. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion, or via consultation of a third author if required.

Data extraction and management

The authors used the standard methods of The Cochrane Collaboration and considered all potential studies for inclusion. At least two authors (D Papatsonis, V Flenady, H Reinebrant and E Tambimuttu) evaluated the methodological quality of studies and independently performed data extraction, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion, or via consultation of a third author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2012) and checked for accuracy.

When information was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judge that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the method as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or was supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses that we undertook.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies are at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it is likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, results are presented as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where appropriate, calculations for number needed to treat for benefit (NNTB) and number needed to treat for harm (NNTH) were performed.

Continuous data

For continuous data, the mean difference was used if outcome measures were comparable between studies. The standardised mean difference was intended for use to combine studies measuring comparable outcomes but using different methodology.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials were excluded from this review.

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in this review, but trials of this type may be identified and included in future updates.

If cluster‐randomised trials are included in future updates, they will be included in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. Their sample sizes will be adjusted using the methods described in the Handbook (Higgins 2011) using an estimate of the intra cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from another source. If ICCs from other sources are used, this will be reported and sensitivity analyses will be conducted to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials are identified, the relevant information will be synthesised. The authors consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely. Heterogeneity in the randomisation unit will also be acknowledged and a sensitivity analysis will be performed to investigate the effects of the randomisation units.

Multi‐arm studies

For the subgroup comparisons undertaken, to avoid double counting, we planned to divide out data from the shared group approximately evenly among the comparisons as described in the Handbook 16.5.4 (Higgins 2011).

One study (Thornton 2009) compared four different dosage regimens of barusiban (0.3, 1, 3 or 10 mg) with placebo. For the analyses undertaken in this review, we have combined all doses for comparison with placebo.

Multiple pregnancy

Where multiple pregnancies are included, wherever possible, analyses should be adjusted for clustering to take into account the non‐independence of neonates from the same pregnancy (Gates 2004). Treating neonates from multiple pregnancies as if they are independent, when they are more likely to have similar outcomes than neonates from different pregnancies, will overestimate the sample size and give CIs that are too narrow. Each woman can be considered a cluster in a multiple pregnancy, with the number of individuals in the cluster being equal to the number of fetuses in her pregnancy. Analysis using cluster trial methods allows calculation of relative risk and adjustment of CIs. Usually this will mean that the confidence intervals get wider. Although this may make little difference to the conclusion of a study, it avoids misleading results in those studies where the difference may be substantial.

Seven studies reported outcomes for twin pregnancies (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1994; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009; Romero 2000; Salim 2012). Two of these studies (Goodwin 1994; Romero 2000) compared ORA (atosiban) versus placebo, one study (Salim 2012) compared ORA versus CCB, and four studies compared ORA (atosiban) versus betamimetics (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009).

For the studies with twin pregnancies, the sample sizes for reported newborn outcomes were adjusted using the methods described in the Handbook (Higgins 2011) using an estimate of the intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.2 as described by Yelland et al (Yelland 2011).

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, levels of attrition in the 'Risk of bias' table were noted. The authors planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis. Analyses were, as far as possible, performed on an intention‐to‐treat basis for all outcomes. Attempts were made to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each study was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes are known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. Heterogeneity was regarded as substantial if the Tau² was greater than zero and either the I² was greater than 30% or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If 10 or more studies had contributed data to meta‐analysis for any particular outcome, we planned to assess reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. Possible asymmetry would have been assessed visually, and if asymmetry was suggested, we planned exploratory analyses for investigation. In this version of the review, insufficient data were available to allow us to carry out this planned analysis.

Data synthesis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2012). Fixed‐effect meta‐analysis was used for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect; i.e. where studies were examining the same intervention, and the studies’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If clinical heterogeneity was deemed sufficient to expect differences between studies in regards to the underlying treatment effects, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, random‐effects meta‐analysis was used to produce an overall summary. This was performed if an average treatment effect across studies was considered clinically meaningful.

In one study (Thornton 2009), which compared four dosing regimens of barusiban with placebo and one study (Goodwin 1996) comparing four different dosing regimens of atosiban with betamimetics, outcomes from all four dosing regimens were combined in the analyses.

The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and the authors discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between studies. If the average treatment effect was deemed to be not clinically meaningful studies were not combined.

Where random‐effects analyses were used, the results are presented as the mean treatment effect with its 95% CI, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we performed investigations using subgroup analyses. Consideration was taken to whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if deemed relevant, we performed a random‐effects analysis. We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2012).

A priori subgroup analyses

We planned the following subgroup analyses.

By population

Women randomised before 28 weeks' gestation versus those randomised at 28 weeks or after.

Women with ruptured membranes at randomisation versus women with intact membranes.

Women with a singleton pregnancy versus women with a multiple pregnancy.

Women who received maintenance therapy* versus women who did not.

(*Use of continued tocolytic agents after successful suppression of threatened preterm labour.)

By intervention

Oxytocin receptor antagonists compared with placebo, further subgrouped by type of oxytocin receptor antagonist.

Oxytocin receptor antagonists compared with other classes of tocolytic agents, further subgrouped by type of other tocolytic agent and type of oxytocin receptors antagonist.

We will assess the following outcomes in subgroup analyses.

Fetal/neonatal outcomes

Perinatal mortality (stillbirth and neonatal death up to 28 days).

Infant death (up to 12 months).

Major childhood sensorineural disability.

Extremely preterm birth (before completion of 28 weeks of gestation).

Very preterm birth (before completion of 34 weeks of gestation).

Preterm birth (before completion of 37 weeks of gestation).

Birth less than 48 hours after trial entry.

Respiratory distress syndrome.

Intraventricular haemorrhage.

Necrotising enterocolitis.

Retinopathy of prematurity.

Chronic lung disease (need for supplemental oxygen therapy at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age).

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

Neonatal length of hospital stay.

Quality of life in childhood (measured by validated instruments).

Maternal outcomes

Serious maternal outcome.

Maternal adverse effects requiring cessation of treatment.

Quality of life after the birth (measured by validated instruments).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of study quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates (greater than 20%), or both. The intention was to exclude poor‐quality studies (including those assessed as low or unknown risk of bias) from the analyses in order to assess whether this made any difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In this review, 29 studies were identified as potentially eligible for inclusion. Nine studies were excluded (Al‐Omari 2006; de Heus 2008; Gagnon 1998; Husslein 2006; Husslein 2007; Poppiti 2009; Steinwall 2005; Valenzuela 1997; Valenzuela 2000). Another five studies are awaiting classification pending additional information from authors (de Heus 2009; Lenzen 2012; Neri 2009; Renzo 2003; Snidow 2013). For further information please seeCharacteristics of studies awaiting classification. One study is ongoing (APOSTEL III).

In this review update, an additional eight studies, involving 790 women testing the effects of oxytocin receptor antagonists for tocolysis in preterm labour, have been included, giving a total of 14 included studies, involving 2485 women.

Included studies

Fourteen studies, involving 2485 women, are included.

Four studies (854 women) compared an oxytocin receptor antagonists with placebo (Goodwin 1994; Richter 2005; Romero 2000; Thornton 2009). Eight studies compared an oxytocin receptor antagonist (atosiban) with betamimetics (Cabar 2008; European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1996; Lin 2009; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009; Shim 2006). Two studies compared an oxytocin receptor antagonist (atosiban) with a calcium channel blocker (CCB) (nifedipine) (Kashanian 2005; Salim 2012).

Participants

The participants in these studies were reasonably homogenous. In the placebo‐controlled studies, the minimum gestational age at inclusion was 20 weeks, and the maximum gestational age at inclusion was 37 weeks. In the studies comparing atosiban with betamimetic agents, the minimum gestational age at study entry ranged from 20 to 23 weeks and the maximum from 33 to 35 weeks. The presence of ruptured membranes was an exclusion criterion in all studies, except one (Nonnenmacher 2009). Exclusion of women with ruptured membranes reflects the clinical uncertainty about the role of tocolytic agents in this situation because infection is more likely to be present and delay in delivery may harm the mother and baby. In all studies, standard maternal and fetal contraindications to tocolysis were reported, e.g. pre‐eclampsia and gestational hypertension. Exclusion criteria also included the use of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents 12 hours prior to randomisation in five studies (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Lin 2009; Moutquin 2000; Shim 2006), and prior tocolytic therapy within 72 hours in one study (Goodwin 1996) and within seven days in one study (Thornton 2009). High‐order multiple gestations (triplets or more) were reported as excluded in six studies (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Lin 2009; Moutquin 2000; Richter 2005; Salim 2012) and all multiple pregnancies were excluded in three studies (Goodwin 1996; Shim 2006; Thornton 2009).

Tocolysis

Three studies compared atosiban with placebo (Goodwin 1994; Richter 2005; Romero 2000), one study compared barusiban with placebo (Thornton 2009), two studies compared atosiban with a CCB (nifedipine) (Kashanian 2005; Salim 2012) and eight studies compared atosiban with betamimetics (ritodrine, fenoterol, salbutamol, terbutaline) (Cabar 2008; European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1996; Lin 2009; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009; Shim 2006).

In the placebo‐controlled studies, two studies (Richter 2005; Romero 2000) administered atosiban as a initial bolus dose of 6.75 mg intravenously (i.v.) followed by an infusion of 300 µg/min for three hours, then 100 µg/minutes for 45 hours. In Romero 2000, maintenance therapy was thereafter administered via subcutaneous injections up to 36 weeks. One study (Goodwin 1994) administered atosiban as a initial bolus dose of 6.75 mg i.v. followed by an infusion of 300 µg/minutes for two hours. One study administered barusiban as a single bolus dose (1 mL of either 0.3 mg, 1 mg, 3 mg or 10 mg barusiban, i.v.). Two of the placebo‐controlled studies included rescue tocolysis as a part of the study protocol. In Goodwin 1994, the primary aim was to determine the effect of atosiban on uterine activity during an infusion limited to two hours. In the atosiban group, 19.6% of the participants required an additional rescue tocolytic agent versus 32% in the placebo group. In this study (Goodwin 1994), maintenance therapy after the two hour infusion was not instituted. In Goodwin 1994, of the 120 women enrolled, 29 (11 atosiban and 18 placebo) required additional tocolysis with magnesium sulphate (n = 23) or subcutaneous terbutaline (n = 6). There is, however, no description of the doses or duration of this additional tocolysis. In Romero 2000, rescue therapy was given in 42% of the atosiban group and in 51% of the placebo group. Participants received rescue tocolytic therapy with an alternate tocolytic of the investigator's choice after discontinuation of the study drug. Rescue tocolysis was considered in this study when preterm labour has progressed after at least one hour of observation and either of the following occurred: (1) cervical effacement of ≥ 75% (≤ 0.5 cm) with no decrease in the frequency or intensity of contractions and continued cervical change (at least a 1 cm change in dilatation or effacement); or (2) cervical dilatation of ≥ 4 cm with a 1 cm increase since the last cervical examination. Maintenance therapy was started with either atosiban or placebo in women who achieved uterine quiescence with a subcutaneous infusion of 0.004 mL (30 µg/minute for atosiban) and was ceased at the end of the 36th week of gestation, at delivery, or if progression of labour necessitated an alternate tocolytic agent. In the third placebo‐controlled study (Richter 2005), rescue tocolysis was not performed. In cases of successful tocolysis but with persisted cervical dilatation, the woman was informed of the option of a cerclage and/or total occlusion of the cervix. One study (Thornton 2009) did not allow any tocolytics as rescue therapy.

In the studies comparing atosiban with nifedipine, one study (Salim 2012), administered atosiban as a initial bolus dose of 6.75 mg i.v. followed by an infusion of 300 µg/minute for three hours, then 100 µg/minute for 45 hours. The other study (Kashanian 2005) administered atosiban as an i.v. infusion of 300 µg/minute up to 12 hours, or six hours after contractions ceased. In one of the studies comparing atosiban with nifedipine (Kashanian 2005), rescue tocolysis was not performed. Nifedipine was given at an initial dose of 10 mg (one capsule) sublingually every 20 minutes for four doses. Maintenance dose with nifedipine was continued orally (20 mg) every six hours for the first 24 hours, and then every eight hours for the following 24 hours, and finally 10 mg every eight hours for the last 24 hours. In the other nifedipine‐controlled study (Salim 2012), rescue tocolysis was performed if progression of labour was determined after one hour but before 48 hours, or if adverse effects of the drug were noted, a cross‐over of the study drugs was performed and the alternative tocolytic drug (i.e. rescue treatment) was initiated. Nifedipine was given as a loading dose of 20 mg orally followed by another two doses of 20 mg, 20 to 30 minutes apart as needed. Maintenance was started after six hours with 20 to 40 mg four times daily for a total of 48 hours. If tocolysis failed from both drugs before 48 hours or admission at a gestational age below 28 weeks, indomethacin as a second rescue agent was started. Initial dose of indomethacin was two 100 mg per rectum tablets, one hour apart, followed by oral tablets of 25 mg four times daily up to a total of 48 hours.

In most of the studies comparing atosiban with betamimetics (Cabar 2008; European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Lin 2009; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009; Shim 2006), an initial bolus dose of 6.75 mg (i.v.) atosiban was given, followed by a continuous infusion of 300 µg/minute for three hours, then 100 µg/minute for a maximum of 15 to 48 hours. One study (Goodwin 1996) tested four atosiban regimens: 6.5 mg bolus dose followed by infusion 300 µg/mL, two mg bolus dose followed by infusion of 100 µg/mL, 0.6 mg bolus dose followed by infusion of 30 µg/minute. All treatments were continued up to 12 hours. In the studies comparing atosiban with betamimetics, betamimetic therapy was administered i.v. for a maximum of 48 hours. Rescue tocolytic therapy was reported as a part of the study protocol for all studies in this comparison. In the European study (European 2001), administration of an alternative tocolytic agent was dependent on both efficacy and tolerability of study medication and could be administered when there was recurrence or progression of preterm labour. In the French/Australian study (French/Australian 2001), if labour was progressing or women experienced intolerable adverse effects of study drug administration, an alternative tocolytic agent could be given. There were 58% (n = 69) in the atosiban group versus 63.1% (n = 77) in the salbutamol group who needed an alternate tocolytic agent. Goodwin 1996 included an alternate tocolytic agent to be used when: (1) the cervix dilated 1 cm or more during therapy; (2) uterine contraction persisted at a same or higher rate; or (3) labour was not controlled, according to the judgement of the investigator. In Shim 2006, rescue tocolysis could be given if the study drug failed either by progression of labour or intolerable adverse events judged by the investigator. Alternative drugs could be ritodrine or magnesium sulphate, but not atosiban as rescue tocolytic in case of failure for women in the ritodrine group. In Lin 2009, re‐treatment with the study drug was allowed when there was recurrence of preterm labour. In Moutquin 2000, an alternative tocolytic agent could be given after the study treatment was stopped if labour was progressing, or if any woman had an intolerable adverse event. Maintenance therapy was used in at least one study in this comparison (Goodwin 1996); however, the details of the regimen were not provided. One study reported that maintenance therapy was not a part of the study protocol (French/Australian 2001). Maintenance therapy was not used in the remaining six studies where atosiban therapy was administered i.v. for a maximum of 48 hours.

Please seeCharacteristics of included studies for further details.

Outcome measures

Most of the studies included reported on the important clinical outcome of respiratory distress syndrome (except Cabar 2008; Kashanian 2005; Nonnenmacher 2009; Richter 2005). Many studies also reported maternal adverse drug reaction (European 2001; Goodwin 1994; Kashanian 2005; Romero 2000; Salim 2012; Shim 2006; Thornton 2009). The outcome of birth within 48 hours of initiation of treatment was reported in 12 (Cabar 2008; European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1994; Goodwin 1996; Kashanian 2005; Lin 2009; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009; Richter 2005; Salim 2012; Shim 2006) of the 14 included studies and perinatal mortality in four studies (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Moutquin 2000; Romero 2000). Other important outcomes were inconsistently reported including preterm birth, which was reported in four studies (European 2001; Romero 2000; Salim 2012; Thornton 2009), and major neonatal morbidity, which was largely not well reported across the studies.

Long‐term outcomes up to two years of age were reported as an abstract (Goodwin 1998a) for infants enrolled in one placebo‐controlled study (Romero 2000). Unfortunately, data were not reported in a format suitable for inclusion In this review. The authors have been contacted for further details before publication of the previous version of this review, but no further information has been forthcoming. The following outcomes were assessed: (1) illness, accidents, and physical abnormalities; (2) measurements of infant weight, length, and head circumference; (3) neurological examinations; (4) Bayley II assessment of mental and motor development; and (5) infant deaths. Although the report stated all infants were followed up and infant death up to 12 months was reported, only 55% of the infants who were originally included in the study were assessed for Bayley II Mental and Motor Development Index (Mean ± SD) and neurological examination at two years. One study comparing barusiban and placebo reported long‐term outcomes (Thornton 2009) for Bayley Scale evaluations of psychomotor developmental index (PDI) and mental developmental index (MDI) and physical growth. The long‐term outcomes were assessed at one year of age (Thornton 2009) and, as this time point was not prespecified, these data have not been included in this review.

In Romero 2000, data for the outcomes of birth less than 48 hours after trial entry and birth less than seven days after trial entry were reported only for women who did not receive alternative tocolytics and therefore these data were not included in the review.

Please seeCharacteristics of included studies for further details.

Excluded studies

We excluded nine studies.

One study was excluded on the basis of quasi‐random allocation (Al‐Omari 2006). Eight studies were excluded as they did not fulfil the intervention inclusion criteria as follows: A study in term labour (de Heus 2008); studies of maintenance tocolysis (Gagnon 1998; Valenzuela 2000); no comparison between different dosing regimens or tocolytic treatment (Husslein 2006); undefined treatment in control group (Husslein 2007); repeat course treatment with tocolysis (Poppiti 2009); did not use an oxytocin receptor antagonist (Steinwall 2005); study aimed to measure oestradiol levels before and after treatment (Valenzuela 1997a).

Please seeCharacteristics of excluded studies for further details.

Risk of bias in included studies

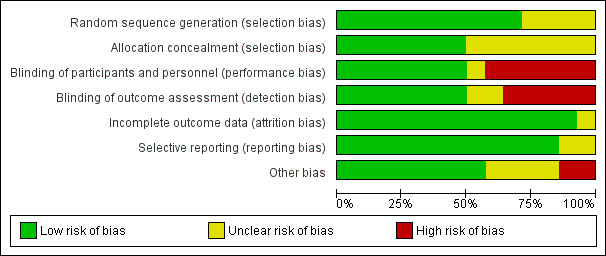

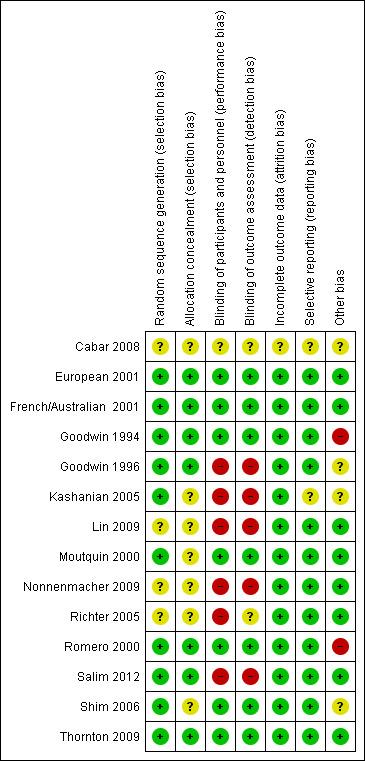

Overall the quality of the included studies was considered fair to good. Refer to Characteristics of included studies for further details and to Figure 1 and Figure 2 for a summary of 'Risk of bias' assessment.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The randomisation sequence generation was judged as adequate in 10 of the 14 included studies (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1994; Goodwin 1996; Kashanian 2005; Moutquin 2000; Romero 2000; Salim 2012; Shim 2006; Thornton 2009) and therefore assessed as having a low risk of selection bias. In the remaining four studies, the randomisation sequence generation process was unclear.

Allocation to treatment was adequately concealed in seven of the 14 included studies (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1994; Goodwin 1996; Romero 2000; Salim 2012; Thornton 2009) and therefore assessed as having low risk of selection bias. In the remaining studies the allocation process was unclear.

Blinding

Blinding of the intervention and outcome assessment was performed in seven of the 14 included studies (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1994; Moutquin 2000; Romero 2000; Shim 2006; Thornton 2009). These studies were placebo controlled. For one study, the blinding of the intervention process was unclear (Cabar 2008). In one study, while a saline infusion control group was used, as different dosing regimens were used, the study was assessed as having a high risk of bias(Richter 2005). For the remaining studies, the lack of blinding of the intervention may be, in part, as a result of the difficulties with adequately blinding such interventions, i.e. presentation of the intervention as either oral versus intravenous and the well‐known side effects of certain interventions.

Incomplete outcome data

The majority (13 of the 14 included studies) had minimal or no attrition and were therefore assessed as having a low risk of attrition bias. For the remaining study, it was unclear whether outcome data were complete (Cabar 2008).

Selective reporting

In 12 of the 14 included studies, no reporting bias was evident (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1994; Goodwin 1996; Lin 2009; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009; Richter 2005; Romero 2000; Salim 2012; Shim 2006; Thornton 2009) and these studies were judged to be at low risk of bias. In the remaining two studies it was unclear whether reporting bias was present (Cabar 2008; Kashanian 2005).

Other potential sources of bias

In eight of the 14 included studies, no other potential sources of bias were apparent European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Lin 2009; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009; Richter 2005; Salim 2012; Thornton 2009) based on baseline characteristics being similar and no other biases were evident. In four studies, the risk of other bias was unclear (Cabar 2008; Goodwin 1996; Kashanian 2005; Shim 2006). In two studies, the risk of other bias was judged to be high (Goodwin 1994; Romero 2000). These two studies (Goodwin 1994; Romero 2000) included women of lower gestational age in the atosiban group compared with the placebo group. One of these studies (Goodwin 1994) also recruited women from five different centres, and the inclusion criteria differed between the centres, which may have introduced bias. In the Romero 2000 trial, there were nearly twice as many atosiban‐treated patients enrolled at < 26 weeks’ gestation. Among the women enrolled at less than 26 weeks' gestation, the number who had advanced cervical dilation was higher in the atosiban group compared with the placebo group.

Assessment of studies that included multiple pregnancies

Seven studies included data from women with a multiple pregnancy (European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1994; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009; Romero 2000; Salim 2012). Two of these studies (Goodwin 1994; Romero 2000) compared ORA (atosiban) versus placebo, one study (Salim 2012) compared ORA versus CCB, and four studies compared ORA (atosiban) versus betamimetics (Nonnenmacher 2009; European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Moutquin 2000). As described previously (Methods), we have adjusted for clustering in the analyses of infant outcomes.

Effects of interventions

Two main comparisons were undertaken as follows.

Comparison 1: Oxytocin receptor antagonists compared with placebo further subgrouped by type of oxytocin receptor antagonist. Comparison 2: Oxytocin receptor antagonists compared with other classes of tocolytic agents by type of other tocolytic agent.

We did not undertake other planned subgroup analyses by population characteristics and by intervention due to insufficient data.

Comparison 1: Oxytocin receptor antagonists (ORA) compared with placebo, further subgrouped by type of ORA

Four studies are included in this analysis. Three studies including 691 women comparing atosiban and placebo (Goodwin 1994; Richter 2005; Romero 2000) and one study (163 women) (Thornton 2009) comparing barusiban with placebo are included in this comparison. For the comparison between atosiban and placebo, the Romero and Goodwin studies (Goodwin 1994; Romero 2000) contributed the majority of data (651 women) and the Richter study (Richter 2005; 40 women) contributed to two outcomes only; stillbirth and birth less than 48 hours after trial entry.

Primary outcomes

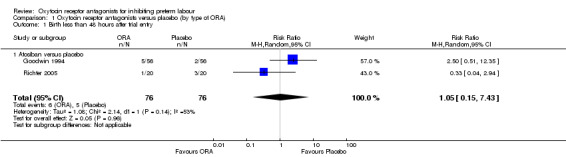

Birth less than 48 hours after trial entry (Analysis 1.1)

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 1 Birth less than 48 hours after trial entry.

Comparing ORA (atosiban) with placebo, no difference was shown in birth less within 48 hours after trial entry (average risk ratio (RR) 1.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.15 to 7.43; random‐effects, Tau² = 1.08, Chi² = 2.14, df = 1 (P = 0.14), I² = 53%) (two studies with 152 women) Analysis 1.1. A moderate degree of statistically heterogeneity was evident for this outcome measure. However, upon exploration of the possible reasons for the heterogeneity by examining clinical features of the studies, we considered an overall summary was meaningful using a random‐effects analysis.

No data were available for the subgroup of barusiban versus placebo.

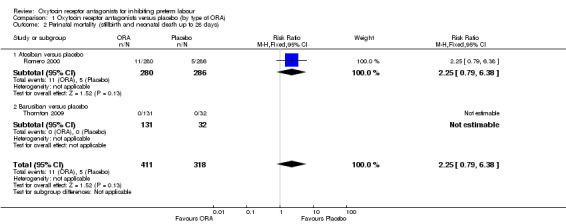

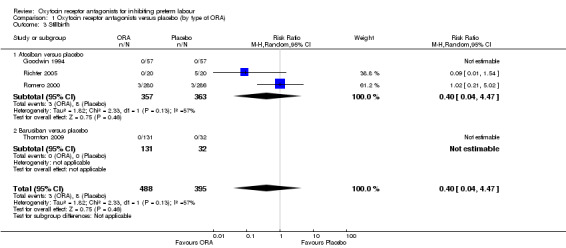

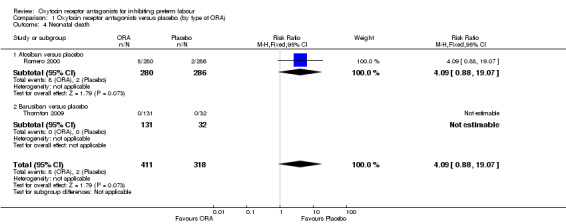

Perinatal mortality, Stillbirth, Neonatal death and Infant death (Analysis 1.2) (Analysis 1.3) (Analysis 1.4) (Analysis 1.5)

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 2 Perinatal mortality (stillbirth and neonatal death up to 28 days).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 3 Stillbirth.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 4 Neonatal death.

1.5. Analysis.

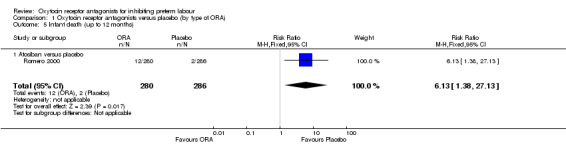

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 5 Infant death (up to 12 months).

Comparing ORA versus placebo no difference was shown in perinatal mortality (RR 2.25, 95% CI 0.79 to 6.38; two studies with 729 infants) (Analysis 1.2), stillbirth (average RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.04 to 4.47 random‐effects; four studies with 883 infants) (Analysis 1.3), or neonatal death (RR 4.09, 95% CI 0.88 to 19.07; two studies with 729 infants) (Analysis 1.4). These findings are driven by the subgroup of trials comparing atosiban versus placebo as no events were reported for the barusiban subgroup including a single trial (Thornton 2009).

A moderate degree of statistical heterogeneity was evident for the outcome measure of stillbirth (Heterogeneity: Tau² = 1.82; Chi² = 2.33, df = 1 (P = 0.13); I² = 57%). However, upon exploration of the possible reasons for the heterogeneity by examining clinical features of the studies, we considered an overall summary was meaningful using a random‐effects analysis.

Infant death (up to 12 months) was increased with the use of the ORA atosiban in one trial (Romero 2000; 566 infants) (RR 6.13, 95% CI 1.38 to 27.13; number needed to treat for harm (NNTH) 28, 95% CI 6 to 377) (Analysis 1.5).

As mentioned in Other potential sources of bias, it is likely that the adverse infant outcomes associated with atosiban in the Romero 2000 trial are due to an imbalance in randomisation which resulted in more women under 26 weeks' gestation and fewer over 32 weeks assigned to the atosiban group. It is of note that in the publication of the trial results, the authors used the denominator of women who were enrolled less than 28 weeks' gestation and reported a non‐statistically significant increase in birth less than 28 weeks' gestation.

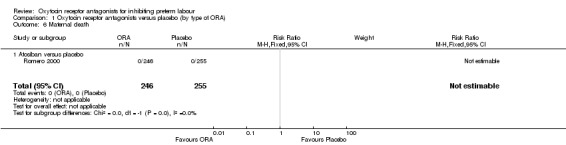

Serious maternal outcome (Analysis 1.6)

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 6 Maternal death.

One study Romero 2000 comparing ORA (atosiban only) with placebo (501 women) reported that no maternal deaths occurred during the trial period.

No data were available on other serious maternal outcomes or the other primary outcomes measure of very preterm birth before 34 weeks' gestation or long‐term outcomes for the child.

Secondary outcomes

For the infant/child

Preterm birth (before 37 weeks gestation) (Analysis 1.10) and Extremely preterm birth (before completion of 28 weeks of gestation) (Analysis 1.11)

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 10 Preterm birth (before completion of 37 weeks of gestation).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 11 Extremely preterm birth (before completion of 28 weeks of gestation).

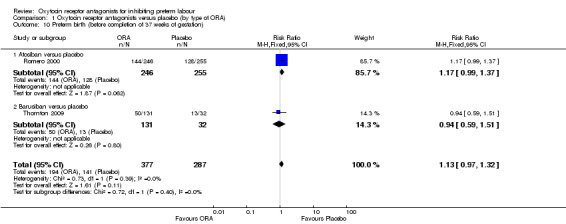

Comparing ORA versus placebo, no difference was found in preterm birth (before 37 weeks' gestation) (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.32; two studies with 664 women). (Analysis 1.10).

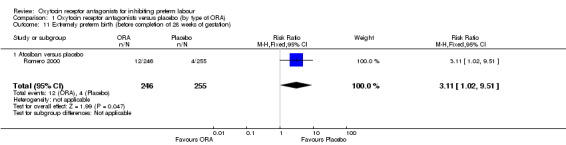

Comparing ORA (atosiban only) with placebo, one trial (Romero 2000) (501 women) showed an increase in extremely preterm birth (before completion of 28 weeks of gestation) (RR 3.11, 95% CI 1.02 to 9.51; NNTH 31, 95% CI 8 to 3188).

No data were available for the subgroup of barusiban versus placebo.

No differences were evident according to type of ORA.

Gestational age (Analysis 1.12) and Birthweight (Analysis 1.13)

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 12 Gestational age (weeks).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 13 Birthweight (grams).

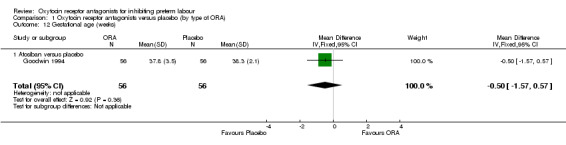

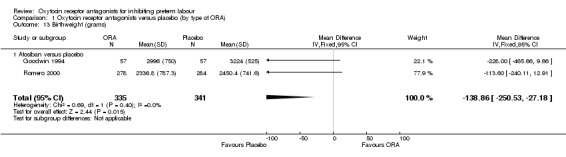

No difference was shown in gestational age at birth comparing ORA (atosiban only) with placebo (mean difference (MD) ‐0.50 weeks, 95% CI ‐1.57 to 0.57; one study with 112 women) (Analysis 1.12). ORA (atosiban) was associated with lower birthweight (MD ‐138.86 g, 95% CI ‐250.53 to ‐27.18; two studies with 676 infants) (Analysis 1.13), however the clinical importance of this difference (139 g) is questionable.

No data were available for the subgroup of barusiban versus placebo.

Neonatal morbidity

No difference was shown when comparing ORA versus placebo overall (or by type of ORA where data were available for these comparisons) for the following outcomes measures.

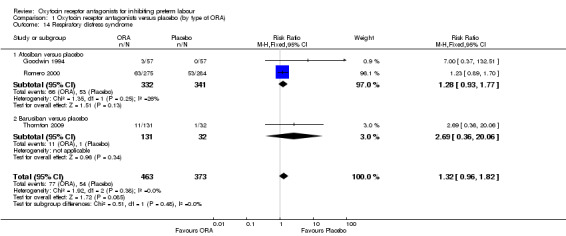

Respiratory distress syndrome (Analysis 1.14)

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 14 Respiratory distress syndrome.

For the comparison ORA versus placebo, no difference was shown in respiratory distress syndrome (RR 1.32; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.82; three studies with 836 infants).

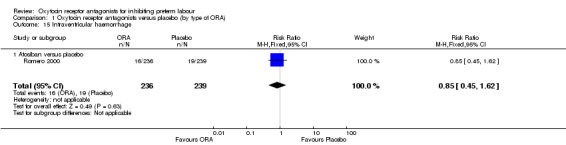

Intraventricular haemorrhage (Analysis 1.15)

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 15 Intraventricular haemorrhage.

ORA (atosiban only) versus placebo: RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.62 (one study with 475 infants).

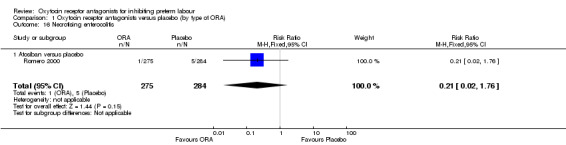

Necrotising enterocolitis (Analysis 1.16)

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 16 Necrotising enterocolitis.

ORA (atosiban only) versus placebo: RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.76 (one study with 559 infants).

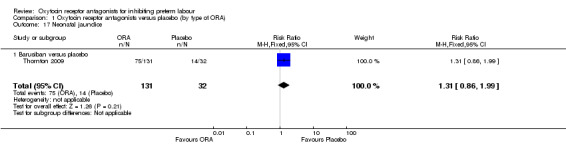

Neonatal jaundice (Analysis 1.17)

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 17 Neonatal jaundice.

ORA (barusiban only) versus placebo: RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.99 (one study with 163 infants).

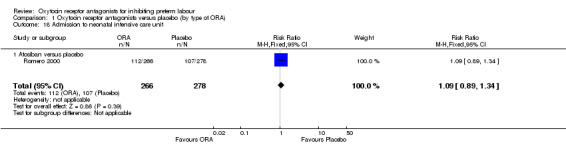

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit (Analysis 1.18)

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 18 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

ORA (atosiban only) versus placebo: RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.34 (one study with 544 infants).

For the woman

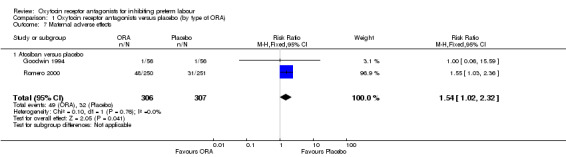

Maternal adverse effects (Analysis 1.7)

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 7 Maternal adverse effects.

ORA (atosiban only) resulted in a significant increase in maternal adverse effects (RR 1.54, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.32; two studies with 613 women; NNTH 18, 95% CI 8 to 480); representing 19% of women having an adverse effect in the ORA group versus 14% in the placebo.

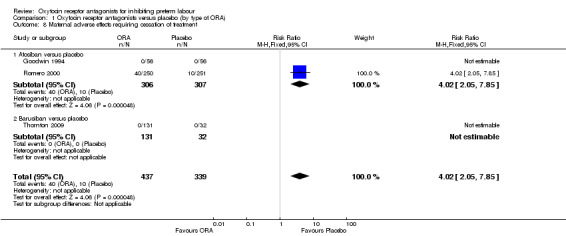

Maternal adverse effects requiring cessation of treatment (Analysis 1.8)

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 8 Maternal adverse effects requiring cessation of treatment.

Maternal adverse effects requiring cessation of treatment was increased for the ORA group when compared to placebo (RR 4.02, 95% CI 2.05 to 7.85; NNTH 12; 95% CI 5 to 33; three studies with 776 women); representing 16% of women having an adverse effect in the ORA group versus 4% in the placebo.

These findings are driven by the subgroup of trials comparing atosiban versus placebo as no events were reported for the barusiban subgroup including a single trial (Thornton 2009).

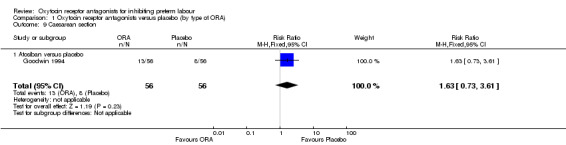

Caesarean section (Analysis 1.9)

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus placebo (by type of ORA), Outcome 9 Caesarean section.

No difference was shown in caesarean section birth comparing atosiban with placebo (RR 1.63, 95% CI 0.73 to 3.61; one study with 112 women).

Comparison 2: Oxytocin receptor antagonists (ORA) compared with other tocolytic agents by type of other tocolytic agent

Eight studies (with 1402 women) are included in the comparison between ORA (atosiban only) and betamimetics (Cabar 2008; European 2001; French/Australian 2001; Goodwin 1996; Lin 2009; Moutquin 2000; Nonnenmacher 2009; Shim 2006). Two studies including 225 women are included in the comparison of ORA (atosiban only) and calcium channel blockers (CCB) (nifedipine only) (Kashanian 2005; Salim 2012). All studies used the ORA atosiban.

Primary outcomes

Birth less than 48 hours after trial entry (Analysis 2.1)

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 1 Birth less than 48 hours after trial entry.

No statistically significant differences were shown within or across subgroups.

ORA versus betamimetics: RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.22 (eight studies with 1389 women).

ORA versus CCB: average: RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.73 (two studies with 225 women).

Moderate heterogeneity was present for the ORA versus CCB comparison (Tau² = 0.22; Chi² = 2.04, df = 1 (P = 0.15); I² = 51%); however, upon exploration of the possible reasons for heterogeneity by examining clinical features of the studies, we considered an overall summary was meaningful using a random‐effects analysis.

Very preterm birth (before completion of 34 weeks of gestation) (Analysis 2.3)

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 3 Very preterm birth (before completion of 34 weeks of gestation).

ORA versus betamimetics: no data were available.

ORA versus CCB: no statistically significant difference was shown (RR 1.70, 95% CI 0.89 to 3.23; one study with 145 women).

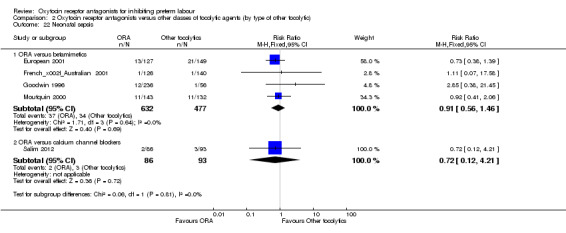

Perinatal mortality (Analysis 2.2), Stillbirth (Analysis 2.4) and Neonatal death (Analysis 2.5).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 2 Perinatal mortality.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 4 Stillbirth.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 5 Neonatal death.

No statistically significant differences were shown within or across subgroups

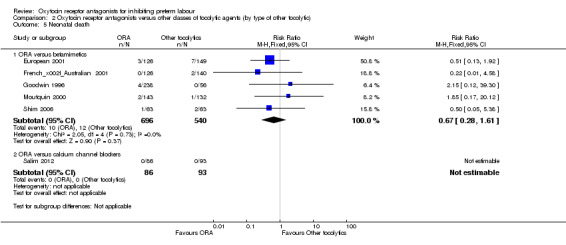

ORA versus betamimetics: perinatal mortality (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.48; three studies with 816 infants) (Analysis 2.2), stillbirth (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.05 to 6.05; four studies with 861 infants) (Analysis 2.4) or neonatal death (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.61; five studies with 1236 infants) (Analysis 2.5).

ORA versus CCB: the single trial in this comparison (Salim 2012, 179 infants), reported that no neonatal deaths occurred during the trial period. No data were available on stillbirth or perinatal mortality.

Serious maternal outcome (Analysis 2.6)

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 6 Maternal death.

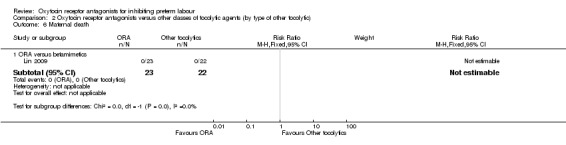

ORA versus betamimetics: one study with 45 women (Lin 2009) reported that no maternal deaths occurred during the trial period.

ORA versus CCB: no data were available.

No other data were available on other serious maternal outcomes or long‐term outcomes for the child.

Secondary outcomes

For the infant/child

Interval between trial entry and birth (Analysis 2.10)

2.10. Analysis.

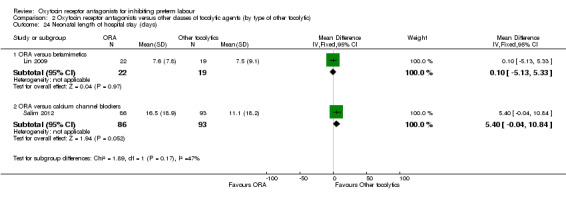

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 10 Interval between trial entry and birth (days).

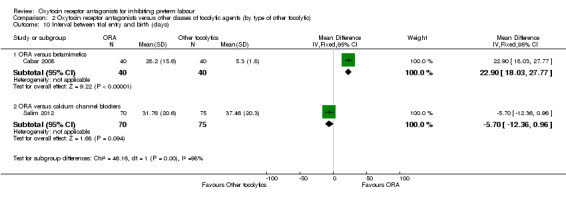

ORA versus betamimetics: an increase in the Interval between trial entry and birth was shown with the use of ORA (MD 22.90 days, 95% CI 18.03 to 27.77; one study with 80 women) (Cabar 2008).

ORA versus CCB: no difference was shown in the interval between trial entry and birth (Salim 2012) (MD ‐5.70 days, 95% CI ‐12.36 to 0.96; one study with 145 women) (Salim 2012).

These results were statistically significantly different across subgroups; test for subgroup differences:Chi² = 46.16, df = 1 (P < 0.01), I² = 97.8%.

Preterm birth (before completion of 37 weeks of gestation) (Analysis 2.11)

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 11 Preterm birth (before completion of 37 weeks of gestation).

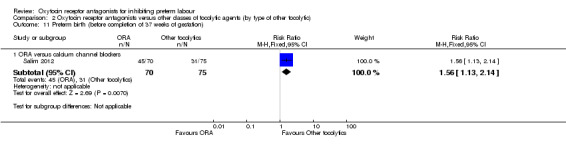

ORA versus betamimetics: no data were available.

ORA versus CCB: in a single study (145 women) ORA (atosiban) resulted in significantly more preterm births compared with CCB (RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.13 to 2.14; NNTH 5, 95% CI 19 to 3).

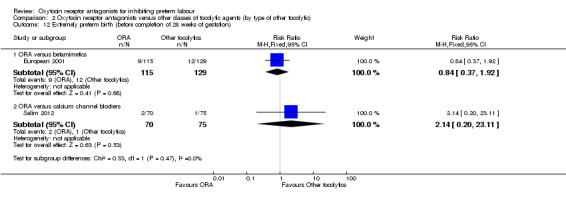

Extremely preterm birth (before completion of 28 weeks of gestation) (Analysis 2.12)

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 12 Extremely preterm birth (before completion of 28 weeks of gestation).

No statistically significant differences were shown within or across subgroups.

ORA versus betamimetics: RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.92 (one study with 244 women).

ORA versus CCB: RR 2.14, 95% CI 0.20 to 23.11 (one study with 145 women).

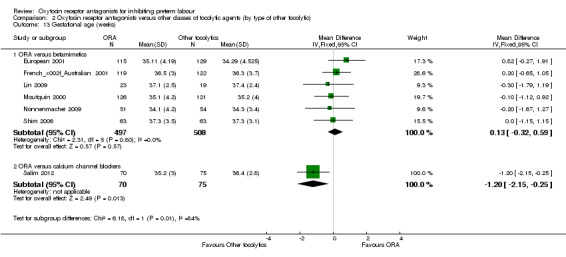

Gestational age at birth (Analysis 2.13)

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 13 Gestational age (weeks).

ORA versus betamimetics: no difference was shown in gestational age at birth (MD 0.13 weeks, 95% CI ‐0.32 to 0.59; six studies with 1005 women).

ORA versus CCB: a lower mean gestational age for ORA group (atosiban) compared with CCB (MD ‐1.20 weeks, 95% CI ‐2.15 to ‐0.25; one study with 145 women).

These results were statistically significantly different across subgroups; test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 6.18, df = 1 (P = 0.01), I² = 83.8%.

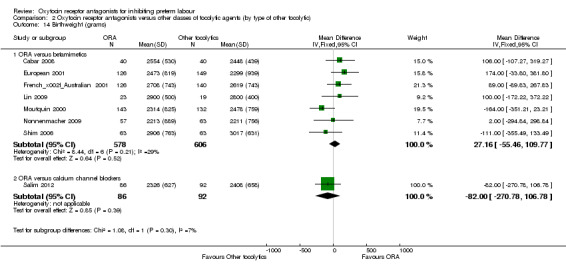

Birthweight (Analysis 2.14)

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 14 Birthweight (grams).

No statistically significant differences were shown within or across subgroups.

ORA versus betamimetics: MD 27.16 g, 95% CI ‐55.46 to 109.77 (seven studies with 1184 infants).

ORA versus CCB: no difference was shown MD ‐82.00 weeks, 95% CI ‐270.78 to 106.78; (one study with 178 infants).

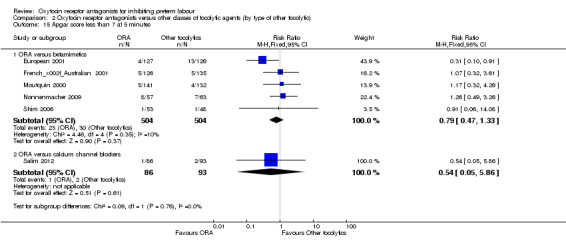

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes (Analysis 2.15)

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 15 Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes.

No statistically significant differences were shown within or across subgroups.

ORA versus betamimetics: RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.33 (five studies with 1008 infants).

ORA versus CCB: RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.05 to 5.86 (one study with 179 infants).

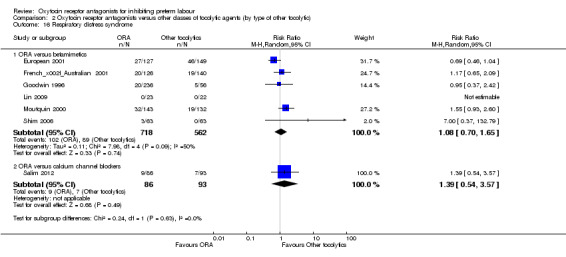

Respiratory distress syndrome (Analysis 2.16)

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 16 Respiratory distress syndrome.

No statistically significant differences were shown within or across subgroups.

ORA versus betamimetics: (average RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.65; random‐effects; six studies with 1280 infants). Moderate heterogeneity was evident (Tau² = 0.11, Chi² = 7.98, df = 4 (P = 0.09), I² = 50%) which was driven by one study (European 2001). However, as no clear reason for the heterogeneity could be identified, we considered an overall summary was meaningful using a random‐effects analysis.

ORA versus CCB: (RR 1.39, 95% CI 0.54 to 3.57; one study with 179 infants).

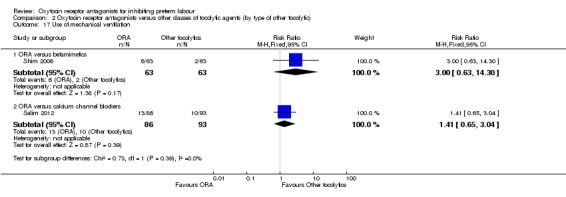

Use of mechanical ventilation (Analysis 2.17)

2.17. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 17 Use of mechanical ventilation.

No statistically significant differences were shown within or across subgroups.

ORA versus betamimetics: RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.63 to 14.30 (one study with 126 infants).

ORA versus CCB: RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.65 to 3.04 (one study with 179 infants).

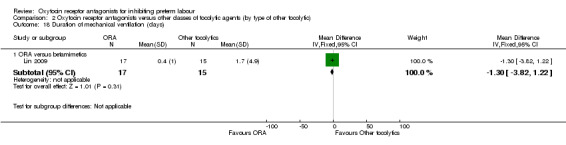

Duration of mechanical ventilation (Analysis 2.18)

2.18. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 18 Duration of mechanical ventilation (days).

No statistically significant differences were shown.

ORA versus betamimetics: MD ‐1.30 days, 95% CI ‐3.82 to 1.22 (one study with 32 infants).

ORA versus CCB: no data were available.

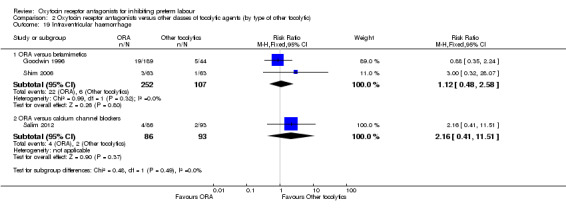

Intraventricular haemorrhage (Analysis 2.19)

2.19. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 19 Intraventricular haemorrhage.

No statistically significant differences were shown.

ORA versus betamimetics: RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.48 to 2.58 (two studies with 359 infants).

ORA versus CCB: RR 2.16, 95% CI 0.41 to 11.51 (one study with 179 infants).

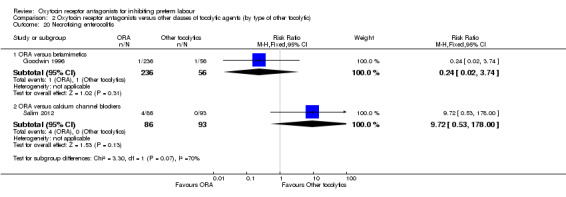

Necrotising enterocolitis (Analysis 2.20)

2.20. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 20 Necrotising enterocolitis.

No statistically significant differences were shown within or across subgroups.

ORA versus betamimetics: RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.02 to 3.74 (one study with 292 infants).

ORA versus CCB: RR 9.72, 95% CI 0.53 to 178.00 (one study with 179 infants).

These results were statistically significantly different across subgroups; test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 3.30, df = 1 (P = 0.07), I² = 69.7%

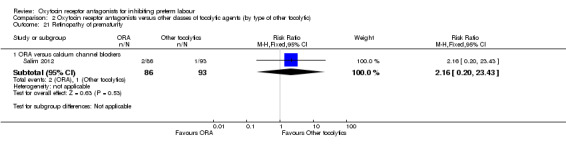

Retinopathy of prematurity (Analysis 2.21)

2.21. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Oxytocin receptor antagonists versus other classes of tocolytic agents (by type of other tocolytic), Outcome 21 Retinopathy of prematurity.

No statistically significant differences were shown.

ORA versus betamimetics: no data were available.

ORA versus CCB: RR 2.16, 95% CI 0.20 to 23.43 (one study with 179 infants).

Neonatal sepsis (Analysis 2.22)

2.22. Analysis.