Abstract

Background and Objectives

Vidofludimus calcium suppressed MRI disease activity compared with placebo in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in the first cohort of the phase 2 EMPhASIS study. Because 30 mg and 45 mg showed comparable activity on multiple end points, the study enrolled an additional low-dose cohort to further investigate a dose-response relationship.

Methods

In a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial, patients with RRMS, aged 18–55 years, and with ≥2 relapses in the last 2 years or ≥1 relapse in the last year, and ≥1 gadolinium-enhancing brain lesion in the last 6 months. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) vidofludimus calcium (30 or 45 mg) or placebo in cohort 1 and vidofludimus calcium (10 mg) or placebo (4:1) in cohort 2 for 24 weeks. The primary end point was the cumulative number of combined unique active (CUA) lesions at week 24. Secondary end points were clinical outcomes and safety.

Results

Across cohorts 1 and 2, 268 patients were randomized to placebo (n = 81), 10 mg (n = 47) vidofludimus calcium, 30 mg (n = 71) vidofludimus calcium, or 45 mg (n = 69) vidofludimus calcium. The mean cumulative CUA lesions over 24 weeks was 5.8 (95% CI 4.1–8.2) for placebo, 5.9 (95% CI 3.9–9.0) for 10 mg treatment group, 1.4 (95% CI 0.9–2.1) for 30 mg treatment group, and 1.7 (95% CI 1.1–2.5) for 45 mg treatment group. Serum neurofilament light chain decreased in a dose-dependent manner. The number of patients with confirmed disability worsening after 24 weeks was 3 (3.7%) patients receiving placebo and 3 (1.6%) patients receiving any dose of vidofludimus calcium. Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 35 (43%) placebo patients compared with 11 (23%) and 71 (37%) patients in the 10 mg or any dose of vidofludimus calcium groups, respectively. The incidence of liver enzyme elevations and infections were similar between placebo and any dose of vidofludimus calcium. No new safety signals were observed.

Discussion

Compared with placebo, vidofludimus calcium suppressed the development of new brain lesions with daily doses of 30 mg and 45 mg, but not 10 mg, establishing the lowest efficacious dose is 30 mg.

Classification of Evidence

This study provides Class II evidence that among adults with active RRMS and ≥1 Gd+ brain lesion in the past 6 months, the cumulative number of active lesions decreased with vidofludimus calcium.

Trial Registration Information

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03846219) and EudraCT (2018-001896-19).

Introduction

Dihydro-orotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) is a mitochondrial enzyme involved in the rate-limiting step of de novo pyrimidine synthesis. Blockage of DHODH activity with teriflunomide is efficacious in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis and is believed to work by preventing the activation and proliferation of pathologic T and B cells and their migration into the CNS.1,2

Vidofludimus calcium is a next-generation, orally available DHODH inhibitor that significantly reduced the development of MRI brain lesions in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 study with efficacy comparable with that of other disease-modifying therapies.3-9 In the first cohort, doses of 30 mg and 45 mg suppressed the cumulative number of combined unique active (CUA) lesions by 70% and 62% after 24 weeks of treatment, respectively, compared with placebo. In addition, both doses of vidofludimus calcium were effective in reducing gadolinium-enhancing, T1, and T2 lesions. Vidofludimus calcium was also shown to be safe and well-tolerated in the trial, with low discontinuation rates and an incidence of diarrhea, neutropenia, and liver enzyme elevations comparable with placebo control. The mentioned adverse events have been linked for teriflunomide to be related to off-target effects on kinases,10 which are not found for vidofludimus calcium. Preclinical studies have also shown vidofludimus calcium has potent activity against Epstein-Barr virus reactivation, a known risk factor of the onset of multiple sclerosis and involved in ongoing autoimmunity,11-14 and is an agonist for Nurr1, a constitutively active ligand-activated transcription factor that has neuroprotective and antineuroinflammatory activity.15-17

No statistically significant differences or otherwise clear signals suggested a difference between the 30 mg or 45 mg dose on the suppression of MRI brain lesions, which warranted the investigation of lower doses of vidofludimus calcium to strengthen the understanding of the dose-response relationship in patients with RRMS. Therefore, a second cohort receiving 10 mg of vidofludimus calcium was enrolled to assess the activity of a lower dose of vidofludimus calcium. In this study, we report the extended results from the pooled data of cohorts 1 and 2 in the phase 2, multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial (EMPhASIS). The primary question being addressed by this study was whether the cumulative number of active lesions decreased with vidofludimus among adults with active RRMS and ≥1 Gd+ brain lesion in the prior 6 months.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This is a randomized, 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial designed to assess the efficacy and safety of 10, 30, or 45 mg of vidofludimus calcium compared with placebo in patients with RRMS who have evidence of disease activity. The study consists of 2 cohorts. Cohort 1 randomized patients to placebo or vidofludimus calcium (30 mg or 45 mg) in a 1:1:1 ratio using a centralized interactive web response system by a group of independent biostatisticians; the results from cohort 1 have been previously reported.3 Based on the results from cohort 1, the study protocol was amended to allow enrollment of a second cohort (cohort 2) to investigate a lower dose of vidofludimus calcium, which randomized patients to placebo or 10 mg of vidofludimus calcium (1:4 ratio). Patients in cohort 2 were enrolled to placebo or vidofludimus calcium to allow blinding and assessment of comparability of the 2 cohorts through their placebo groups. Before any clinical activities were performed in cohort 2, patients were informed of the trial and the safety profile of vidofludimus calcium and signed an informed consent form specific to cohort 2. Patients were enrolled from Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, and Ukraine in cohort 1 and from Bulgaria, Poland, and Ukraine in cohort 2.

Male and female patients between the ages of 18 and 55 years who had a diagnosis of RRMS according to the 2017 revised McDonald criteria were included.18 The study required patients to have (1) at least 2 relapses in the last 24 months or at least 1 relapse in the last 12 months before randomization, and (2) 1 or more documented gadolinium-enhancing multiple sclerosis (MS)–related brain lesions in the last 6 months before enrollment. The study excluded patients with an MS type other than RRMS and a relapse within 30 days of or during the screening period. Patients were excluded if they had prior use of any DHODH inhibitor. Full description of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Assessments

The study design has been previously described.3 In short, patients received daily oral doses of vidofludimus calcium or matching placebo for 24 weeks with an option to continue in an open-label extended treatment period if they met respective eligibility criteria. The extended treatment period for both cohorts is currently ongoing. Randomization was stratified by the number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions (either 0 or ≥1).

Standardized brain MRI scans were collected at baseline and every 6 weeks in addition to clinical assessments (e.g., Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS], Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication19 according to the schedule of assessments; see eTable 1). Corticosteroid treatment was offered at the choice of the investigator if a relapse occurred or was suspected. Blood samples were also collected for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (biomarker) analysis. The study design and assessments were identical between cohort 1 and cohort 2 with the following exception: MRI machines with a field strength of ≥1.5T were allowed in cohort 1, whereas those with only 1.5T were allowed in cohort 2.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the difference in adjusted mean of cumulative CUA lesions over 24 weeks between placebo and each dose of vidofludimus calcium (10 mg, 30 mg, and 45 mg). Secondary MRI outcomes were gadolinium-enhancing lesions, new/enlarging T2 lesions, and new/enlarging T1 lesions. Secondary clinical end points included time-to-first-relapse, EDSS progression, and confirmed disability worsening (CDW). The definitions for these end points are listed in the Supplementary Materials. Investigators monitored for adverse events throughout the duration of the study which were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 22.0. Analyses of safety and clinical end points were conducted using the intent-to-treat population, defined as patients who received at least 1 dose of placebo or vidofludimus calcium. MRI outcomes were based on patients who received at least 1 dose of placebo or vidofludimus calcium, who were investigated using 1.5T MRI, and were from the same sites as those enrolled in cohort 2. Data for patients who received placebo in cohort 1 and cohort 2 were combined into a single placebo group to enrich the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Brain lesions were calculated using a generalized linear model with a negative binomial distribution and a logarithmic link function adjusted for the number of baseline gadolinium-enhancing lesions. For the cumulative number of CUA and gadolinium-enhancing lesions, the baseline volume of T2 lesions was also included as independent effect in the negative binomial regression model. Time-to-first relapse was calculated using Cox regression. CDW was defined as an EDSS worsening (an increase in the EDSS compared with baseline of at least 1.5 points if baseline EDSS = 0, 1.0 point if baseline EDSS was between 1 and 5, or 0.5 point if baseline EDSS ≥5.5) confirmed 12 or 24 weeks later. The initial progression had to occur within the blinded treatment period, although confirmation could have been during the open-label extension period. Formal hypothesis testing was conducted for cohort 1 but not in this analysis to prevent the risk of bias due to multiplicity.3 Sample size and power analysis for cohort 1 was previously described.3 No formal sample size calculation was conducted for cohort 2, although based on previous phase 2 MS trials, 60 patients were considered sufficient to estimate dose-response. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in eSAP 1 and eSAP 2, respectively.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study was conducted in a manner consistent with all relevant regulatory authorities and ethics committees including International Council for Harmonization, Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and the Declaration of Helsinki (version of 1996). Local ethics committees approved and provided oversight of the study. In addition, a steering committee provided advice on the conduct of the trial and periodically reviewed blinded safety data. All study participants provided written informed consent before any study-related procedure. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03846219) and EudraCT (2018-001896-19).

Data Availability

Data will be shared with qualified researchers who submit a research proposal following approval by an independent review board and a signed data sharing agreement. Requests for data can be made 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the United States and Europe with no expiration date on requests. Deidentified data, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and case report forms, will be provided in a secure sharing environment.

Results

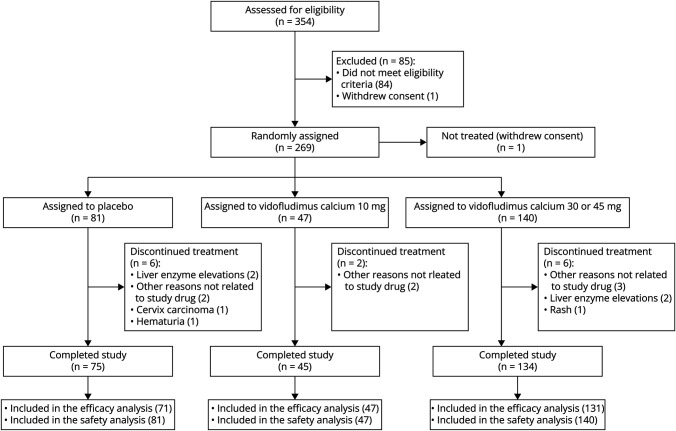

Between January 2019 and April 2020 for cohort 1 and November 2020 and June 2021 for cohort 2, 269 patients were randomized to receive placebo (n = 69 in cohort 1 and n = 12 in cohort 2), 10 mg (n = 47), 30 mg (n = 71), or 45 mg (n = 69) vidofludimus calcium, of which 1 was not treated (Figure 1). Fourteen patients (6 [7%] given placebo and 8 [4%] given any dose of vidofludimus calcium) discontinued the study prematurely before the 24-week blinded treatment period, of which 7 (3%) were treatment-related adverse events (4 [5%] in the placebo group and 3 [4%] in the 45 mg group). The safety population consisted of 268 patients who received at least 1 dose of placebo or vidofludimus calcium. The efficacy analysis consisted of 249 patients. The patient flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. Baseline patient demographics, clinical, and MRI characteristics were comparable between groups (Table 1). In patients treated with any dose of vidofludimus calcium, 99 (56%) patients were treatment-naïve, and the remainder had prior exposure to other disease-modifying therapies (77 [31%], 38 [15%], and 2 [1%], respectively) (eTable 2). Inclusion criteria required a gadolinium-enhancing lesion any time in the past 6 months, which all patients met. Table 1 reports the proportion with 1 or more gadolinium-enhancing lesion at baseline; this was not a requirement for inclusion in the trial.

Figure 1. Patient Disposition.

Patient disposition for the 30 mg and 45 mg groups individually are previously reported.3

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and MRI Characteristics at Baseline

| Placebo, cohort 2 (n = 12) | Placebo, cohort 1 + 2 (n = 71) | Vidofludimus calcium, 10 mg (n = 47) | Vidofludimus calcium, any dose (n = 178)a | |

| Age (y) | 37.4 (8.8) | 36.7 (8.7) | 38.1 (98) | 37.0 (9.0) |

| Female, n (%) | 8 (67) | 49 (69) | 34 (72) | 117 (66) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 12 (100) | 71 (100) | 47 (100) | 178 (100) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Duration of disease (y)b | 4.96 (1.01, 13.8) | 3.61 (1.26, 10.2) | 4.66 (0.77, 8.38) | 3.61 (1.36, 9.11) |

| EDSS score | 3.50 (1.50, 3.50) | 3.00 (2.00, 3.50) | 3.00 (2.00, 3.50) | 2.50 (2.00, 3.50) |

| Number of relapses in the last 24 mo, n (%) | ||||

| 1c | 4 (33) | 35 (49) | 19 (40) | 82 (46) |

| 2 | 5 (42) | 27 (38) | 19 (40) | 75 (42) |

| ≥3 | 3 (25) | 9 (13) | 9 (19) | 21 (12) |

| MRI characteristics | ||||

| Gadolinium-positive lesions, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 7 (58) | 36 (51) | 28 (60) | 95 (53) |

| ≥1 | 5 (42) | 35 (49) | 19 (40) | 83 (47) |

| No. of gadolinium-positive lesions | 1.08 (2.07) | 1.24 (2.23) | 0.91 (1.73) | 1.03 (1.73) |

| Volume of T2 lesions per patient (cm3)d | 18.1 (16.8) | 12.7 (12.0) | 10.1 (12.3) | 11.9 (12.9) |

| Treatment-naïve | 7 (58) | 50 (70) | 20 (43) | 99 (56) |

| Previous exposure to disease-modifying drugsc, n (%) | ||||

| Interferon or glatiramer acetate | 4 (33) | 14 (20) | 23 (49) | 51 (29) |

| Oral drugs | 1 (20) | 7 (10) | 4 (9) | 27 (15) |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (<3) |

Abbreviation: EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale.

Data are n (%), mean (SD), or median (interquartile range) and consist of the modified full analysis set.

Consists of patients receiving 10 mg, 30 mg, or 45 mg vidofludimus calcium. Patient characteristics for the 30 mg and 45 mg groups individually are previously reported.3

Duration since time at which the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis was first documented.

Last treatment line.

Consists of the patients included in the efficacy analysis.

MRI Outcomes

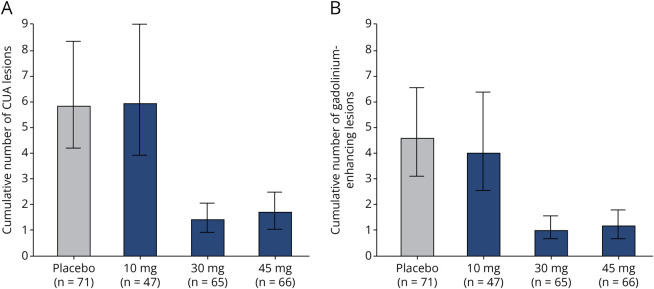

The adjusted mean cumulative number of combined unique active lesions up to 24 weeks was 5.8 (95% CI 4.1–8.2) in the placebo group, 5.9 (95% CI 3.9–9.0) in the 10 mg vidofludimus calcium group, 1.4 (95% CI 0.9–2.1) in the 30 mg vidofludimus calcium group, and 1.7 (95% CI 1.1–2.5) in the 45 mg vidofludimus calcium group (Figure 2A). This represents a 2% increase (10 mg group), 76% reduction (30 mg group), and 71% reduction (45 mg group) in the mean cumulative number of combined unique active lesions up to 24 weeks compared with placebo. The adjusted mean number of cumulative gadolinium-enhancing lesions, T1 lesions, and T2 lesions up to 24 weeks was also lower in the 30 mg and 45 vidofludimus calcium groups compared with that in the placebo group, but not in the 10 mg vidofludimus calcium group (Table 2 and Figure 2B). The proportion of patients without new lesions was lower in the 30 mg and 45 mg dose groups compared with that in the placebo group (Table 2).

Figure 2. Cumulative CUA Lesions (A) and Gadolinium-Enhancing Lesions (B) at Week 24 in Patients Treated With Vidofludimus Calcium or Placebo.

CUA = combined unique active. Data presented as mean (95% CI).

Table 2.

MRI and Clinical Outcomes

| Placebo (n = 71) | Vidofludimus calcium 10 mg (n = 47) | Vidofludimus calcium 30 mg (n = 65) | Vidofludimus calcium 45 mg (n = 66) | |

| MRI outcomes | ||||

| Cumulative CUA lesions up to week 24 (95% CI) | 5.8 (4.1–8.2) | 5.9 (3.9–9.0) | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) |

| Cumulative Gd+ lesions up to week 24 (95% CI) | 4.6 (3.2–6.5) | 4.0 (2.6–6.3) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) | 1.2 (0.7–1.8) |

| Cumulative T1 lesions up to week 24 (95% CI) | 2.8 (2.0–4.1) | 2.1 (1.3–3.4) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) |

| Cumulative T2 lesions up to week 24 (95% CI) | 5.3 (3.8–7.5) | 5.2 (3.4–8.0) | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 1.6 (1.0–2.3) |

| Proportion of patients without new lesions up to week 24, % (95% CI) | ||||

| Gd+ lesions | 38 (27–50) | 40 (26–56) | 60 (47–72) | 50 (37–63) |

| T2 lesions | 31 (21–43) | 35 (21–50) | 52 (40–65) | 42 (30–55) |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| Annualized relapse rate (95% CI) | 0.52 (0.33–0.81) | 0.28 (0.12–0.62) | 0.38 (0.22–0.66) | 0.47 (0.28–0.78) |

| Mean change in EDSS score between BL and week 24 | 0.07 (0.36) | 0.06 (0.51) | 0.01 (0.25) | 0.00 (0.39) |

| Proportion of patients with 24wCDW event between BL and week 24a, n (%) | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

Abbreviations: 24wCDW = confirmed disease worsening was met if there was an EDSS worsening was confirmed 12 or 24 wk later; BL = baseline; CUA = combined unique active; EDSS = Expanded Disability Status Scale; Gd+ = gadolinium-enhancing.

Data presented as mean (SD or 95% CI).

Cumulative lesions are presented as adjusted mean.

Consists of patients receiving at least 1 dose of placebo or vidofludimus calcium.

Clinical Outcomes

Patients receiving any dose of vidofludimus calcium had lower adjusted mean annualized relapse rate than patients receiving placebo (Table 2). Cox regression for time to relapse showed a 33% reduction in the risk of relapse in patients who received 30 mg of vidofludimus calcium compared with that in those who received placebo (HR: 0.67, 95% CI 0.29–1.54) (eFigure 1 and eTable 3). Change in the mean EDSS score after 24 weeks was similar between placebo and any dose of vidofludimus calcium (Table 2). The number of patients who had confirmed disability worsening after 24 weeks was 3 (3.7%) patients receiving placebo and 3 (1.6%) patients receiving any dose of vidofludimus calcium.

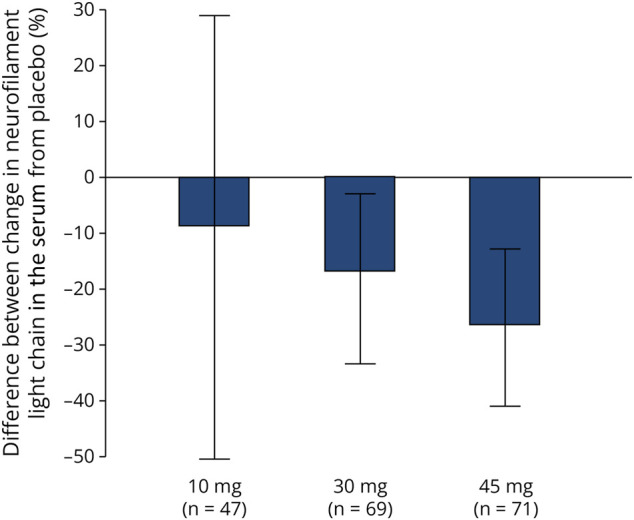

Neurofilament Light Chain

At baseline, median neurofilament light chain concentrations in the serum (pg/mL) was 74.1 (range: 26.4–1,340) in the placebo group, 52.2 (range: 16.1–273) in the 10 mg vidofludimus calcium group, 64.1 (range 22.2–1,110) in the 30 mg vidofludimus calcium group, and 68.3 (range 15–341) in the 45 mg vidofludimus calcium group. After 24 weeks, the median percent change from baseline was 7.0 (95% CI −11.0 to 25.0) in the placebo group, 7.5 (95% CI −17.0 to 24.0), −17.0 (95% CI −24.0 to −7.0), and −20.5 (95% CI −29.0 to −13.0) in patients who received 10 mg, 30 mg, and 45 mg of vidofludimus calcium, respectively. Relative to placebo, neurofilament light chain in the serum after 24 weeks decreased from baseline in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Difference in Percentage Change of Neurofilament Light Chain in the Serum From Baseline to Week 24 Relative to Placebo.

Data presented as median (95% CI). Neurofilament light chain was measured using electrochemiluminescent immunoassay.

Pharmacokinetics

Mean trough plasma concentrations of vidofludimus calcium (µg/mL) at week 24 were 1.94 (SD 0.98), 4.06 (SD 1.8), and 6.07 (SD 3.14) in patients who received 10 mg, 30 mg, and 45 mg doses, respectively (eFigure 2).

Safety and Tolerability

Thirty-five (43%) patients in the placebo group experienced any treatment-emergent adverse event during the study, compared with 11 (23%) patients who received 10 mg of vidofludimus calcium and 71 (37%) who received any dose of vidofludimus calcium. All treatment-emergent adverse events were mild except for 9 (11%) patients in the placebo group compared with 3 (6%) who received 10 mg of vidofludimus calcium and 30 (16%) patients who received any dose of vidofludimus calcium with events that were moderate. The most common treatment-emergent adverse event by preferred term was headache, which occurred with similar incidence in the placebo group (5 [6%]) and in patients who received any dose of vidofludimus calcium (7 [4%]) (Table 3). Treatment-emergent adverse events that did not occur in the placebo group but occurred in patients treated with any dose of vidofludimus calcium were bronchitis (3 [2%]), rash (4 [2%]), fatigue (4 [2%]), alopecia (4 [2%]), and cystitis (4 [2%]). Of patients from cohort 2 who enrolled during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, 3 (25%) patients in the placebo group and 4 (9%) patients in the 10 mg vidofludimus calcium group had a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

Table 3.

Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events

| Placebo (n = 81) | Vidofludimus calcium, 10 mg (n = 47) | Vidofludimus calcium, any dose (n = 187)a | |

| Any event, n (%) | |||

| Treatment-emergent adverse eventb | 35 (43) | 11 (23) | 71 (37) |

| Serious adverse event | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Treatment-emergent adverse event leading to treatment discontinuation | 4 (5) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in >2% of patients in any group by preferred termc, n (%) | |||

| Headache | 5 (6) | 0 | 7 (4) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 3 (4) | 0 | 8 (4) |

| Coronavirus infection | 3 (4) | 4 (9) | 4 (2) |

| Upper respiratory infection | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Respiratory tract viral infection | 3 (4) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Respiratory tract infection | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (<1) |

| Back pain | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Influenza | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Bronchitis | 0 | 1 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Rash | 0 | 0 | 4 (2) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 4 (2) |

| Alopecia | 0 | 0 | 4 (2) |

| Cystitis | 0 | 0 | 4 (2) |

Consists of patients receiving 10 mg, 30 mg, or 45 mg of vidofludimus calcium. Primary safety analysis for the 30 mg and 45 mg groups individually are previously reported.3

Treatment-emergent adverse events were defined as any event not present before the first dose of placebo or vidofludimus calcium or any event already present that worsened in either intensity or frequency following treatment.

Patients were counted only once by preferred term.

Adverse events defined by the investigator as treatment related occurred in 7 (9%) and 21 (11%) patients receiving placebo or any dose of vidofludimus calcium, respectively. Adverse events leading to discontinuation occurred in 4 (5%) and 3 (2%) patients receiving placebo or any dose of vidofludimus calcium, respectively. In the placebo group, these consisted of liver enzyme elevations (2 [3%]), squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix (1 [1%]), and hematuria (1 [1%]). In vidofludimus calcium–treated patients, these consisted of liver enzyme elevations (2 [2%]) and rash (1 [1%]), all which occurred in the 45 mg dose group. Three serious adverse events occurred during the trial (squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix in the placebo group and open fracture and ureterolithiasis/tubulointerstitial nephritis in the vidofludimus calcium 30 mg group), all of which were considered unrelated to study treatment. No deaths occurred during the study.

Few liver enzyme elevations, defined as ALT or AST >5 times the upper limit of normal, occurred during the study and were similar in patients treated with 10 mg (1 patient [1%]) or any dose of vidofludimus calcium (4 patients [2%]) when compared with those who received placebo (2 patients [3%]). There were no remarkable changes in hematologic laboratory parameters during the study including the incidence of neutropenia (1 [<1%] vs 1 [1%]) and lymphopenia (0 vs 0) between patients treated with any dose of vidofludimus calcium and placebo, respectively. The incidence of infections (37 [20%] vs 20 [25%]) and renal events (5 [3%] vs 2 [2%]) was also similar between patients treated with any dose of vidofludimus calcium and placebo, respectively.

Discussion

Phase 2 dose-range finding studies of disease-modifying therapy for multiple sclerosis have been challenging due to expense, and thus, typically use only 2 doses.4,6 In this study, we used a sequential phase 2 trial approach wherein the initial phase 2 trial findings informed selection of an additional dose to study within the same phase 2 trial; specifically, after results from the first 2 dose cohorts (30 and 45 mg) in this phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled trial–guided selection of a third, 10 mg dose group. Overall, we found that doses of 30 mg and 45 mg, but not 10 mg, suppressed new MRI brain lesions after 24 weeks when compared with placebo, demonstrating a dose-dependent effect and suggesting the dose of 30 mg vidofludimus calcium once daily as the most appropriate for phase 3 studies in patients with RRMS.20,21

The cumulative number of CUA lesions up to week 24 was 76% and 71% lower in 30 and 45 mg vidofludimus calcium groups when compared with that in placebo, respectively. This finding is consistent with the primary results and after the addition of more patients in the placebo group from cohort 2. The observed activity of vidofludimus calcium on brain lesions compares similarly with other disease-modifying therapies.4,7-9 The results for cumulative number of CUA lesions, T1 lesions, or T2 lesions were similar in the 10 mg group and placebo group, although there was a slight decrease observed for gadolinium lesions (13% reduction) and for neurofilament light chain in the serum (9% reduction) with 10 mg. The dose-dependent trend in the reduction of serum neurofilament light chain across 10, 30, and 45 mg dose groups suggests that neurofilament light chain may be a sensitive measure of anti-inflammatory effects complementary to the assessment of new MRI lesions.

As expected, mean trough concentrations of vidofludimus calcium increased proportionally with higher doses. In the previous report, we demonstrated that the suppression of MRI lesions after a 30 mg and 45 mg dose of vidofludimus calcium was evident already at week 6, which corresponds to the earliest posttreatment MRI assessment in this study.3 Although the event rate was low, the rate of CDW after 24 weeks was approximately double in the placebo group compared with patients who received any dose of vidofludimus calcium. This may be an early signal that treatment with vidofludimus calcium may avoid or delay disability progression, which is being evaluated in the open-label extension phase of this study and ongoing phase 3 studies.

The safety profile of vidofludimus calcium was comparable with that of placebo, with an overall incidence of TEAEs of 37% and 43%, respectively. Treatment with any dose of vidofludimus calcium was associated with a very low discontinuation rate (2%) and incidence of serious adverse events (1%), supporting a favorable safety and tolerability profile. Safety for the 30 mg and 45 mg dose cohorts was previously reported individually and showed no clear dose-related effect on adverse events.3 With the addition of patients on active treatment, we continued to observe low rates of adverse events and serious adverse events, similar to placebo. More patients in this analysis vs the initial patient cohorts continued to show a low rate of hepatic adverse events in patients treated with vidofludimus calcium (<1%), which was not different than placebo.

The rate of adverse events in this trial can be compared with teriflunomide, a DHODH inhibitor currently approved for relapsing forms of MS. Across all doses of vidofludimus calcium, the rates of diarrhea (0%) and alopecia (2%) compare favorably with those observed in the phase 3 TOWER and TEMSO trials of terifludomide, where diarrhea was reported in 11%–18% and alopecia in 10%–13% of participants who received teriflunomide.1,2 Similarly, hepatic adverse events were reported in <1% of vidofludimus calcium–treated participants but in 11%–14% of terifludomide-treated participants. No neutropenia or lymphopenia was observed with vidofludimus calcium, too. It is difficult to compare across different trials, where patient characteristics may differ, so ongoing trials of vidofludimus calcium will further clarify its safety profile. The observed difference may be explained by vidofludimus calcium lacking off-target inhibition of other kinases, thereby limiting generalized antiproliferative and/or immunosuppressive effects.1,2,10,19

Of the 59 patients enrolled during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, 3 patients (25%) in the placebo group and 4 patients (9%) in the 10 mg dose group tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. In addition, there was also no increase in the overall incidence of any infection between placebo and vidofludimus calcium–treated patients, suggesting vidofludimus calcium does not impair humoral or cellular immunity and increase the risk of infection. The CALVID-1 trial of vidofludimus calcium in COVID-19 showed that in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the rate and timing of developing SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was not different between patients treated with placebo or 45 mg vidofludimus calcium.22 These findings imply that vidofludimus calcium can be safely administered in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and may also allow for effective humoral vaccination responses.

The relatively short study duration (i.e., 24 weeks) limits the interpretation of clinical end points such as annualized relapse rate, confirmed disability worsening events, and change in EDSS; therefore, these end points should be interpreted with caution and should be considered exploratory. Two phase 3 studies evaluating vidofludimus calcium in patients with RRMS are ongoing.20,21 Hypothesis testing was not conducted in this analysis because it was not preplanned and risks introducing bias due to multiplicity after the primary analysis. The results from this analysis are consistent with the primary analysis.3

In conclusion, a dose-dependent effect of vidofludimus calcium on the suppression of new MRI lesions was demonstrated with an acceptable safety profile. This analysis confirms the justification for the 30 mg dose carried forward in ongoing clinical trials in RRMS.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the study participants, study investigators, and study personnel.

Glossary

- CDW

confirmed disability worsening

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- CUA

combined unique active

- DHODH

dihydro-orotate dehydrogenase

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- RRMS

relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Appendix 1. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Robert J. Fox, MD | Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis, Cleveland Clinic, OH | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design |

| Heinz Wiendl, MD | Department of Neurology with Institute of Translational Neurology, University of Münster, Germany | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Christian Wolf, MD | Lycalis sprl, Brussels, Belgium | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Nicola De Stefano, MD, PhD | Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, University of Siena, Italy | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design |

| Johann Sellner, MD | Department of Neurology, Landesklinikum Mistelbach-Gänserndorf, Austria | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Viktoriia Gryb, PhD | Regional Clinical Hospital Department of Vascular Neurology, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Konrad Rejdak, MD | Department of Neurology, Medical University of Lublin, Poland | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Plamen S. Bozhinov, MD | Medical University of Pleven, Bulgaria | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Daniel Vitt, PhD | Immunic AG, Gräfelfing, Germany | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Hella Kohlhof, PhD | Immunic AG, Gräfelfing, Germany | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Jason Slizgi, PhD | Independent consultant, Raleigh, NC | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Matej Ondrus, MD | Immunic AG, Gräfelfing, Germany | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Valentina Sciacca, MSc | Immunic AG, Gräfelfing, Germany | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Andreas R. Muehler | Immunic AG, Gräfelfing, Germany | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

Appendix 2. Coinvestigators

| Coinvestigators are listed at Neurology.org/NN. |

Contributor Information

for the EMPhASIS investigators:

Penko Shotekov, Plamen Bozhinov, Maya Danovska, Ivaylo Tarnev, Lachezar Traykov, Ivan Milanov, Paraskeva Stamenova, Ara Kaprelyan, Ekaterina Titianova, Radostina Dimova, Rosen Ikonomov, Kosta Kostov, Anastasiya Trenova, Neli Petrova, Kana Prinova, Sasho Kastrev, Maciej Czarnecki, Konrad Rejdak, Robert Bonek, Jozef Koscielniak, Katarzyna Jarus-Dziedzic, Aura Panea, Ana Maria Ionescu, Cristina Mitu, Serhiy Kareta, Olena Moroz, Vladyslav Mishchenko, Larysa Sokolova, Victoriia Gryb, Nataliya Tomakh, Nataliya Lytvynenko, Sergii Moskovko, Nataliia Buchakchyiska, Pavlo Khaitov, Olga Shulga, Iryna Skrypchenko, Oleksandra Tsivkovska, Volodymyr Smolanka, and Tjalf Ziemssen

Study Funding

Immunic AG, Lochhamer Schlage 21, 82166, Gräfelfing, Germany.

Disclosure

R.J. Fox reports personal fees from AB Science, Biogen, Celgene, EMD Serono, Genentech, Genzyme, Immunic AG, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, Siemens, and TG Therapeutics; clinical trial contracts from Biogen, Novartis, and Sanofi; H. Wiendl reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Biogen, Merck Serono, and Sanofi Genzyme; personal fees from Actelion, Alexion, Evgen, F. Hoffmann‐La Roche, Gemeinnützige Hertie‐reStiftung, Immunic, Lundbeck, MedDay Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Roche Pharma AG, Teva, and WebMD Global; and grants from Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft (DFG), Else Kröner Fresenius Foundation, European Union, Fresenius Foundation, German Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF), GlaxoSmithKline, Hertie Foundation, Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Studies (IZKF) Muenster, NRW Ministry of Education and Research, PML Consortium, RE Children's Foundation, and Swiss MS Society, outside the submitted work; C. Wolf is a partner at Lycalis sprl and reports compensation for his organization from BMS, Celgene, Desitin, Immunic, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Roche, Synthon, Teva, and Viatris for consulting and speaking; N. De Stefano has received honoraria from Biogen‐Idec, Genzyme, Immunic, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Celgene, and Teva for consulting services, speaking, and travel support. He serves on advisory boards for Merck, Novartis, Biogen‐Idec, Immunic, Roche, and Genzyme, and he has received research grant support from the Italian MS Society; J. Sellner received honoraria for participation in advisory boards, consultancy, and lecturing from Biogen, BMS, Immunic, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi; V. Gryb reports grants/personal fees from Medpace, PPD, PRA Health Sciences, PSI, Roche, Sanofi, and Verum; K. Rejdak is the president elect of the Polish Neurologic Society; P.S. Bozhinov reports no declaration of interests; D. Vitt is a shareholder and employee of trial sponsor and a holder of patents for the drug under investigation; H. Kohlhof is a shareholder and employee of trial sponsor and a holder of patents for the drug under investigation; M. Ondrus is an employee of trial sponsor; V. Sciacca is an employee of trial sponsor; A.R. Muehler is a shareholder and employee of trial sponsor and a holder of patents for the drug under investigation. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Confavreux C, O'Connor P, Comi G, et al. Oral teriflunomide for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (TOWER): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(3):247-256. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70308-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Connor P, Wolinsky JS, Confavreux C, et al. Randomized trial of oral teriflunomide for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(14):1293-1303. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1014656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox RJ, Wiendl H, Wolf C, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial evaluating the selective dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor vidofludimus calcium in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9(7):977-987. doi: 10.1002/ACN3.51574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kappos L, Antel J, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod (FTY720) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(11):1124-1140. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa052643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen JA, Arnold DL, Comi G, et al. Safety and efficacy of the selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator ozanimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RADIANCE): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):373-381. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00018-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kappos L, Gold R, Miller DH, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral fumarate in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIb study. Lancet. 2008;372(9648):1463-1472. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61619-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selmaj K, Li DKB, Hartung HP, et al. Siponimod for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (BOLD): an adaptive, dose-ranging, randomised, phase 2 study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):756-767. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70102-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Comi G, Filippi M, Wolinsky JS. European/Canadian multicenter, double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study of the effects of glatiramer acetate on magnetic resonance imaging–measured disease activity and burden in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(3):290-297. doi: 10.1002/ana.64.abs [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Connor PW, Li D, Freedman MS, et al. A phase II study of the safety and efficacy of teriflunomide in multiple sclerosis with relapses. Neurology. 2006;66(6):894-900. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000203121.04509.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muehler A, Kohlhof H, Groeppel M, Vitt D. The selective oral immunomodulator vidofludimus in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: safety results from the COMPONENT study. Drugs R D. 2019;19(4):351-366. doi: 10.1007/s40268-019-00286-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider-Hohendorf T, Gerdes LA, Pignolet B, et al. Broader Epstein-Barr virus-specific T cell receptor repertoire in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2022;219(11):e20220650. doi: 10.1084/JEM.20220650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lublin FD, Häring DA, Ganjgahi H, et al. How patients with multiple sclerosis acquire disability. Brain. 2022;145(9):3147-3161. doi: 10.1093/BRAIN/AWAC016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022;375(6578):296-301. doi: 10.1126/SCIENCE.ABJ8222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marschall M, Peelen E, Müller R, et al. IMU-838, a small molecule DHODH inhibitor in phase 2 clinical trial for multiple sclerosis, shows potent anti-EBV activity in cell-culture-based systems: potential additional benefits in multiple sclerosis treatment. ECTRIMS. 2021. ePoster P372. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2021;27(2_suppl):134-740. doi: 10.1177/13524585211044667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vietor J, Gege C, Stiller T, et al. Development of a potent Nurr1 agonist tool for in vivo applications. J Med Chem. 2023;66(9):6391-6402. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willems S, Merk D. Medicinal chemistry and chemical biology of Nurr1 modulators: an emerging strategy in neurodegeneration. J Med Chem. 2022;65(14):9548-9563. doi: 10.1021/ACS.JMEDCHEM.2C00585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Decressac M, Volakakis N, Björklund A, Perlmann T. NURR1 in Parkinson disease--from pathogenesis to therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(11):629-636. doi: 10.1038/NRNEUROL.2013.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, et al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Study to Evaluate the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of IMU-838 in Patients With Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis (ENSURE-2). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05201638. Updated October 24, 2022.

- 21.Study to Evaluate the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of IMU-838 in Patients With Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis (ENSURE-1). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05134441. Updated October 24, 2022.

- 22.Vehreschild MJGT, Atanasov P, Yurko K, et al. Safety and efficacy of vidofludimus calcium in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Infect Dis Ther. 2022;11(6):2159-2176. doi: 10.1007/S40121-022-00690-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be shared with qualified researchers who submit a research proposal following approval by an independent review board and a signed data sharing agreement. Requests for data can be made 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the United States and Europe with no expiration date on requests. Deidentified data, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and case report forms, will be provided in a secure sharing environment.