Abstract

A prominent threat to causal inference about peer effects in social science studies is the presence of homophily bias, that is, social influence between friends and families is entangled with common characteristics or underlying similarities that form close connections. Analysis of social study data has suggested that certain health conditions such as obesity and psychological states including happiness and loneliness can spread between friends and relatives. However, such analyses of peer effects or contagion effects have come under criticism because homophily bias may compromise the causal statement. We develop a regression-based approach which leverages a negative control exposure for identification and estimation of contagion effects on additive or multiplicative scales, in the presence of homophily bias. We apply our methods to evaluate the peer effect of obesity in Framingham Offspring Study.

Keywords: Causal inference, Collider, Exogeneity, Homophily, Negative Control Exposure

1. INTRODUCTION

In social studies, it is of great interest to assess the causal contagion effect of one individual on their social contacts. Historically, causal inference was primarily developed within the potential outcome framework to explicitly allow for interference. Recently, causal inference research has extended the classical potential outcome framework to allow for interference, i.e., that an individual’s outcome may be affected by another’s exposure (Sobel, 2006; Hudgens and Halloran, 2008; VanderWeele and Tchetgen Tchetgen, 2011; Tchetgen Tchetgen and VanderWeele, 2012; Liu and Hudgens, 2014; Liu et al., 2016). However, inferring causation from social studies remains challenging because correlation in outcomes between individuals with social ties may not only be due to social influence, but also to latent factors that influence social relation formation. The phenomenon that individuals tend to associate and bond with persons that they have most in common with is known as homophily (Shalizi and Thomas, 2011).

Different types of experimental designs and analytic methods have been developed to study social relationship formation or to adjust for homophily bias. For example, Camargo et al. (2010) investigated friendship formation among randomly assigned roommates in college and concluded that randomly assigned roommates of different races are as likely to become friends as of the same race. In observational studies, Christakis and Fowler (2007) explored the spread of obesity to one individual (ego) from their friend or spouse (alter). Specifically, they included in a regression model for ego’s BMI, a time-lagged measurement of ego’s obesity status, the obesity status of alter, a time-lagged measurement of alter’s obesity status and some observed covariates. They found evidence suggesting that obesity spreads through social ties. Using the same approach, Christakis and Fowler examined the evidence of social influence for smoking, happiness, loneliness, depression, drug use, and alcohol consumption (Christakis and Fowler 2007, 2008; Fowler and Christakis 2008; Christakis and Fowler 2013).

In recent years, published analyses by Christakis and Fowler have come under critical scrutiny. For instance, Shalizi and Thomas (2011) argued that controlling for alter’s lagged obesity status may at best only partially account for homophily bias. They pointed out that if the latent factor influencing friendship formation affects current obesity status even after controlling for past obesity status, one may still observe an association between ego’s and alter’s obesity status using classical regression methods even if alter has no social influence on ego’s obesity status. Cohen-Cole and Fletcher (2009) argued that using the same method as Christakis and Fowler’s on traits unlikely to be transmitted among social relationships such as height, acne and headaches led to the same conclusion that they spread among friends and relatives. To account for both unmeasured confounding and homophily, O’Malley et al. (2014) leveraged multiple genes in an instrumental variables (IV) approach to identify peer effects under a linear model for the outcome and exposure. They assume that the causal relationship is non-directional and found a positive causal peer effect of BMI between ego and alter using this IV approach. However, the IV approach requires the exclusion restriction that none of the genes used to define the IV has a causal effect on any of the unmeasured factors that give rise to formation of social ties, an assumption which may be difficult to justify in social relationship problems (Fowler et al., 2009).

In this paper, we are also interested in evaluating the person-to-person spread of traits in a social study. We develop an alternative regression-based approach that explicitly accounts for the presence of homophily bias without requiring a valid IV or relying on linear exposure and outcome regression models. Instead of an IV approach, we consider a negative control design that one observes a variable associated with the unmeasured factor inducing homophily, and that such a variable is independent of the outcome conditional on the unmeasured factor inducing homophily. Such a variable is formally called a negative control exposure variable.

Negative control variables have primarily been used in epidemiological applications to detect and sometimes correct for unmeasured confounding (Lipsitch et al., 2010; Tchetgen Tchetgen, 2013; Sofer et al., 2016; Miao et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2020). Elwert and Christakis (2008) recently used a negative control exposure to detect homophily bias in the analysis of dyadic data, i.e., data with pairs of two individuals. Specifically, they used the death of an ex-wife as a negative control variable to investigate the “widowhood effect”, i.e., the effect of the death of a spouse on the mortality of a widow. However, they do not provide a formal counterfactual approach for inference leveraging a negative control outcome to completely account for homophily bias. Partly inspired by this work, we develop theoretical grounds for the use of negative control exposures in peer influence settings. In order to illustrate our approach, we reconsider as running example the analysis performed by Christakis and Fowler (2007) to evaluate the contagion effect of obesity using dyadic data from the Framingham Study. In the Framingham study, we consider as negative control exposure, the alter’s BMI measurement from the subsequent visit. In contrast to the IV assumption which rules out any dependence between the IV and the unmeasured factor implicated in homophily mechanism, our method requires and leverages such dependence. We provide sufficient conditions under which our negative control exposure can be used to detect and account for homophily bias in order to recover the causal effect of primary interest. Moreover, it is worth noting that the proposed method accommodates both directional and mutual nameship in social influences.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce notation. We propose a general regression-based framework to adjust for homophily bias with a negative control exposure variable in Section 3. We evaluate our methods in a simulated study in Section 4. Next, we illustrate our methods in estimating the spread of obesity in the Framingham Offspring Study in Section 5. We conclude with a discussion in Section 6.

2. PRELIMINARIES

In the dyadic analysis terminology, the key subjects of interest are called “egos” and any subjects to whom egos are linked are called “alters.” The roles of ego and alter are exchangeable depending on which person’s outcome is of interest. To simplify the problem, we only consider data where the study population can be partitioned into pairs, or “dyads”. Although the approach equally applies to overlapping dyads but requires appropriately accounting for dependence across dyads as discussed in VanderWeele et al. (2012). Following the notation of O’Malley et al. (2014), we use subscript 1 to denote alter and 2 to denote ego for any given dyad. We focus on the spread of a trait between two time points. That is, we take the perspective of individual 2 and the goal is to estimate the effect of individual 1’s trait at baseline on the trait of individual 2 at follow-up. For example, in Framingham Offspring Study, we are interested in the effect of having an obese person as alter at baseline on ego’s BMI status at a subsequent study visit. Such information is important for clinical and public health interventions (Christakis and Fowler, 2007).

We consider a study design where the dyads are based on nameship. As in Framingham Offspring Study, each study participant is required to name a single person of contact in an effort to mitigate loss to follow-up. A dyad is formed between two persons if at least one person names the second. Let if alter names ego as their contact person at baseline and otherwise . Similarly, let denote whether ego names alter as their contact at baseline. We restrict nameship variables and within a dyad. Because both and are binary variables, there are four different nameship types, which we encode with : (a) null naming if ; (b) active naming if ; (c) passive naming if and (d) mutual naming if . Active naming indicates ego names alter while the alter does not name the ego. Passive naming indicates alter names the ego while the ego does not name the alter. Null naming indicates neither individual names the other while mutual naming indicates both individuals name the other. Because dyad formation requires at lease one person naming another, in the observed sample of dyads.

Let and denote the observed traits of individual at baseline and at follow-up . The outcome of interest is ego’s trait at follow-up, i.e., . For clarity sake, subscripts and superscripts are sometime suppressed, such as . Let denote ego’s exposure value, i.e., that is, the indicator of alter’s trait at baseline. For example, in the case where obesity defines the trait of interest, is alter’s obesity status, i.e., (alter’s ). Our methods apply more generally, whether is binary, continuous, polytomous or a count exposure. Let be a possible realization of (e.g., for obese and for no obese), and denote an ego’s potential outcome if her exposure were hypothetically set to . Throughout, we make the consistency assumption that the observed outcome is almost surely, when .

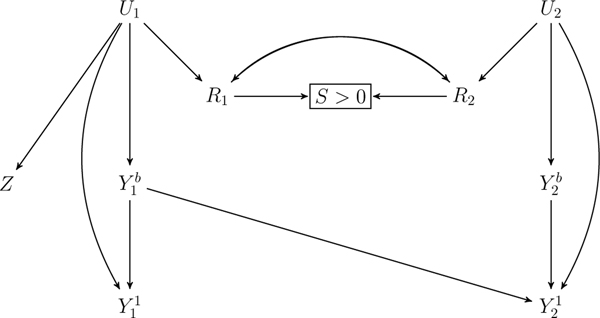

Let denote covariates for alter and ego. Let denote an unmeasured factor that affects not only past and current traits of the alter , but also the nameship variable . Define similarly. The corresponding directed acyclic graph is given in Figure 1 (Shalizi and Thomas, 2011). The parameter of interest is for , which corresponds to the average treatment effect of the alter’s baseline trait on ego’s trait at the follow-up visit, given that the dyad is of type and covariates .

Figure 1:

Causal diagram illustrating homophily bias.

The parameter of interest is the effect of the obesity status of alter (individual 1) at baseline on ego BMI (individual 2) at follow-up, i.e., , . We use and to denote the observed weight information on individual baseline and follow-up, is the unmeasured factor that affects both the nameship and the weight of individual , is the nameship variable for individual and is the summary of nameship type. We omit observed covariates for simplicity. In our empirical example, we use as the negative control exposure .

Because for all observed dyads, , the DAG in Figure 1 represents the conditional distribution of conditional on . Because is a descendant of both and , in the terminology of graph theory, is called a collider (Conditioning on collider or its descendant unblocks a back-door path ) (Pearl, 2009, Shalizi and Thomas, 2011). A direct consequence of this graphical structure is that a standard regression model for conditional on , and , which fails to condition on either or will generally be subject to collider bias so that it may reveal a non-null association between and even when fails to cause and there is no unmeasured confounding of the effects of on in the underlying population (see Figure 1). This specific type of collider bias is called homophily bias. Because and are unobserved and is always conditioned on, homophily bias (Shalizi and Thomas, 2011) cannot be accounted for without an additional assumption. Next we consider leveraging a negative control exposure to both detect and correct for collider bias.

Let denote a negative control exposure variable that satisfies the following assumptions:

Assumption 1.

;

Assumption 2.

almost surely;

Assumption 3.

, where denotes independence between variables and denotes dependence. Assumption 1 states that must be associated with given and . This assumption is represented in the DAG of Figure 1, provided that the arrow between and is known to be present. The assumption would also hold if were a direct cause of even if were independent of . Assumption 2 is a form of exclusion restriction of no direct causal effect of on upon setting to . Assumption 3 is an assumption of no unmeasured confounding between and conditional on , , , and . Thus, the association between and given , , can be attributed completely to homophily bias. Hereafter, a negative control exposure for homophily bias control is a variable known to satisfy Assumptions 1–3.

Furthermore, we assume that the exposure variable is not subject to unmeasured confounding given as illustrated in the DAG in Figure 1:

Assumption 4.

.

Assumption 4 rules out residual confounding of the causal effect of on upon conditioning on , and nameship type . However, is not independent of given and only and therefore, homophily may be interpreted as inducing a violation of changeability upon conditioning on , even though is not a common cause of and in the overall population (i.e., upon marginalizing over ).

The following two examples provide choices of negative control exposures that have been considered in social studies.

Example 1.

Elwert and Christakis (2008) investigated the potential presence of homogamy bias (homophily bias due to spousal similarity) in making inference about the widowhood effect.Specifically, they proposed to use the potential death of an ex-wife as a negative control exposure of the widowhood effect on the mortality of their ex-husband to test for homogamy bias. They found a significant effect of a current wife’s death on her husband’s mortality but no significant effect of an ex-wife’s death on her ex-husband’s mortality. These results support the existence of a causal widowhood effect, which cannot be explained away by homogamy bias.

Example 2.

Cohen-Cole and Fletcher (2009) applied the regression methods in Christakis and Fowler (2007) and Christakis and Fowler (2008) to traits that are unlikely to be transmitted via social connections including acne, headaches, and height. They found that these traits are significantly associated among friends and thus conclude the existence of homophily bias of such social studies in the literature. Technically, these analyses may be viewed as double negative control analyses as they incorporate both negative control exposure and outcome variables (Miao and Tchetgen Tchetgen, 2017; Miao et al., 2018).

We reanalyze the Framingham data considered by Christakis and Fowler (2007) using our proposed methodology taking as negative control exposure variable, the ego’s BMI measure at follow-up . Ego and alter’s contemporaneous BMI measures cannot be causally related, therefore fullfilling Assumption 2. Furthermore, it is clear that such a choice of is guaranteed to satisfy Assumption 1 because any unmeasured cause of ego’s baseline BMI (and S) is likely also a cause of his or hers BMI at follow-up. In Section 3, we provide conditions under which Assumption 3 is also credible for this choice of negative control exposure.

3. REGRESSION BASED APPROACH

3.1. Identification

We first discuss the case where is continuous. Suppose the data generating mechanism satisfies

| (1) |

where , and are otherwise unrestricted. The outcome regression model (1) assumes that the effect of on ego’s trait does not interact with . Under Assumptions 2–3 encoded in the model, the right-hand side of model (1) does not depend on . Furthermore, under Assumption 4, The conditional causal effect of interest under model (1) is . For example, in Framingham Offspring Study, the parameter of interest can be interpreted as the contagion effect in nameship of alter’s obesity status at baseline on ego’s BMI at the follow-up visit within levels of . A detailed derivation of the causal contagion effect is given in the Appendix. The standard linear structural model is a special case corresponding to , , where denotes matrix transpose.

However, because is unobserved, an additional assumption is needed for identification. We consider the following generalized polytomous logit model for and

| (2) |

where and is the baseline log odds function of when is set to its reference value 0. Equation (2) specifies a log linear odds ratio association between and conditional on , and while leaving and unrestricted. An important example within this class of models we will primarily focus on is given by a multinomial logistic regression .

Additionally, we assume that in the population, and are mean independent conditional on :

| (3) |

Equation (3) is consistent with the causal diagram in Figure 1 because and , are marginally independent for any pair of individuals in the underlying population, i.e. in absence of collider bias induced by conditioning on .

Finally, we assume that

| (4) |

where . Equation (4) states that conditional on and , the association between and is entirely due to a location shift. This assumption would hold if were normally distributed with homoscedastic error, conditional on , , , . In principle, as apparent in proving our main results, equation (4) only needs to hold for , and therefore selection bias may in fact be more severe for dyads with so that association between and may manifest itself beyond the mean in these dyads, e.g., with the shape and spread of .

Assumptions (1)–(4) are not testable without an additional restriction. The following example illustrates a familiar shared random effect model under which equations (1)–(4) hold.

Example 3.

Suppose that ,

and is the random effect shared between models for and to encode a latent association between them with , then Assumptions (1)–(4) hold.

We now give our main identification result under Model (1).

Proposition 1.

Under Model (1), Assumptions 1–4 and equations (2)–(4), we have that

| (5) |

where is an unrestricted function of ,

We provide a detailed proof in the Appendix. Comparing (5) with (1), we note that the left hand-side of (5) is by iterated expectation equal to , and therefore the proof of Proposition 1 hinges on establishing that under our assumptions . Equation (5) highlights the important role of the negative control variable which appears on the right hand side of the equation only through its association with in . Note that equation (5) would continue to hold even if were not conditioned on (or the edge from to were removed in Figure 1, such that were independent of given , , ), with in for . In this case it would generally not be possible to tease apart this latter term which captures selection bias from structural part of the equation as both are unrestricted function of , thus rendering the causal effect non-identified. Identification of the causal contagion effect now depends on identification of given dyadic study design. Below, we provide sufficient conditions under which such identification is possible.

According to Proposition 1, the coefficient . Hence, encodes the association between and and therefore is zero if either does not predict , i.e., is the same for all , or if is degenerate in the sense that it does not predict . In the Gaussian case of Example 3, we show in the Appendix that making explicit the aforementioned interpretation. An important advantage of the proposed approach is that it provides a framework to formally test the null hypothesis of no homophily bias as a test of the null hypothesis that for all , .

Proposition 1 presumes the identity link function is specified for the outcome model. Similar results can be obtained for a multiplicative model (i.e. log link) which may be more appropriate for binary or count outcomes. For instance, when the response is binary, the following conditional causal risk ratio may be of interest for . To ground ideas, suppose that

| (6) |

Because is conditioned on in (6), suppose Assumption 4 holds, can be interpreted as the causal contagion effect of alter on ego on the multiplicative scale, e.g. on the risk ratio scale for binary . A similar effect can be defined when the treatment is continuous. We have the following result for the multiplicative model, the proof of which is given in the Appendix. With a slight abuse of notation, we use the same notation for parameters as in the case of the additive model.

Proposition 2.

Under Model (6), Assumptions 1–4 and equations (2)–(4), we have

| (7) |

where is an unrestricted function of .

Propositions 1 and 2 are only useful to the extent that one can identify the selection mechanism from observed dyadic sample. Because the sample implicitly conditions on , nonparametric identification is in general not an option, and therefore one must impose a restriction in order to make progress. In this vein, we propose to posit a model of form with finite dimensional unknown parameter .

3.2. Estimation and Inference

Consider under the assumed model given above, a dyad’s contribution to the likelihood function of in the underlying population

| (8) |

where is a user specified function of , e.g., . Because the observed sample space conditions on , the corresponding contribution of the observed likelihood function for a given dyad is:

Because according to Proposition 1, the propensity score is also involved in the outcome model, one obtain an MLE for all unknown parameters by maximizing a joint likelihood of for a given dyad. For example, although unnecessary, it is convenient to specify a normal working model for the outcome giving rise to following likelihood for any specific dyad using Proposition 1,

Let denote the vector of the parameters in the nameship mechanism and the outcome regression. The log likelihood is therefore

where is the index for dyad and is the total number of dyads in the study. The maximum likelihood estimator for is defined as .

The asymptotic distribution of the contagion effect estimator follows from the standard likelihood theory. We assume dyads are non-overlapping and people from different dyads are independent.

Proposition 3.

Under Model (1), suppose that Assumptions 1–4 hold and that equations (2)–(4) hold, and additionally assume the likelihood of is correctly specified, then as , where , is the Fisher information matrix.

Under a multiplicative model (7), one can carry out a likewise estimation in a similar fashion by maximizing the joint likelihood of and given , , , . Asymptotic distribution of the proposed estimator under model (7) can be obtained as in Proposition 3.

4. SIMULATION

We evaluate the proposed estimator for the causal effect of peer effect using simulations. As a reference, we include a naive estimator which regresses outcome directly on the exposure without adjusting for homophily bias . The simulation is carried out in the following steps.

We first generate a sample of size . For each dyad, we generate a covariate from a standard normal distribution. We also generate and independently from a Bernoulli distribution with probability 0.5.

Let . In model (8), we set , and . We generate the nameship variable and jointly from probability mass function given in (8). Set , , and and . Given , , , , we generate the unmeasured variable from a normal distribution with mean from (1) and standard deviation 0.5.

For each individual , generate identically and independently from normal distribution with mean and variance 1.5.

Calculate our estimator by maximizing the likelihood . We also calculate a naive estimator which regresses directly on , for each nameship without adjusting for homophily bias.

Repeat Steps 3–4 100 times.

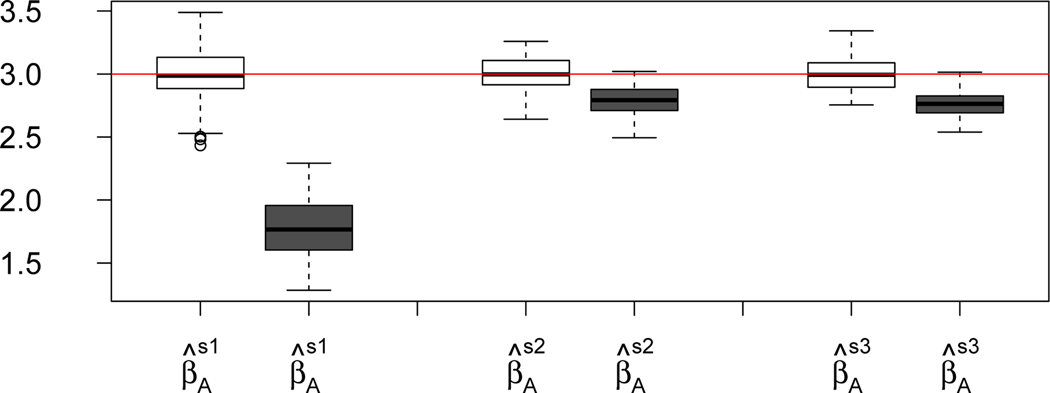

We verify in the Appendix that equations (2)–(4) are satisfied for the data generating model. The boxplot of the two estimators for three nameships are given in Figure 2. This figure appears in color in the electronic version of this article, and any mention of color refers to that version. The white boxes correspond to our estimator and the gray boxes are the naive estimator. Our estimator has much smaller MSE than the naive estimator. For example under nameship , the MSE of our estimator is 0.04 and that of the naive estimator is 1.56. A detailed point estimate of all the relevant nuisance parameters of our proposed methods and their Monte Carlo standard error and the average estimated standard error are given in Table 1. The standard errors are estimated using the Fisher information matrix. The point estimates and the standard error estimates are close to their true values, demonstrating that our methods can accurately estimate the causal effects in the presence of homophily bias.

Figure 2:

Boxplot of the causal effects using our estimator and a naive regression estimator in a simulation study. White boxes denote our proposed estimators and gray boxes denote the naive estimators. This figure appears in color in the electronic version of this article, and any mention of color refers to that version.

Table 1:

Estimates, standard error and p-values of coefficients in a naive analysis without distinction among relationships

| Est | SE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.01 | |

| ego’s BMIb | 0.92 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| ego’s age | −0.22 | 0.06 | <0.01 |

| alter’s age | 0.17 | 0.06 | <0.01 |

5. FRAMINGHAM OFFSPRING STUDY

The Framingham Offspring Study was initiated in 1971 and the study population consists of most of the offsprings of the original Framingham Heart Study cohort and the spouses of the offsprings. Clinical exams were offered every four years. During each clinical exam, the participants underwent a detailed examination including physical examination, medical history, laboratory testing, and electrocardiogram. At the end of each exam, each participant was asked to name a single friend, sibling or spouse, which was likely to be the one with the most influence. The original purpose of the naming process was to record a person of contact, but such information also revealed relationship ties and thus has been used to assess the social influence (Christakis and Fowler, 2007; O’Malley et al., 2014). Among the relationship ties provided, approximately 50% of the nominated friend contacts were also participants in the FHS and thus they had the same information, including BMI collected. Most spouses of FHS participants were also FHS participants.

Therefore, by design, the Framingham Offspring Study population could be partitioned into dyads. We estimated our model with unique dyads of spousal and nearly disjoint friendship. Occasional overlap of dyads when the same person was named by multiple individuals was ignored similar to O’Malley et al. (2014). Because later visits suffered from severely low attenuation rate, we focused on the spread of obesity between baseline and the first follow-up.

We carried out a peer effect analysis for 4531 distinct dyads for which alters are spouses (1527 dyads), siblings (2674 dyads), or friends of egos (330 dyads). The status of ego and alter was randomly assigned. In principle, one can use both assignments in single analysis, however, that required clustering analysis at the level of dayad to account for correlation within dyad. For the purpose of illustration, we considered a single contribution per dyad. Obesity status was defined as a binary variable that takes value 1 if BMI is over 30, and 0 if otherwise. Let denote the exposure of ego, that is, the obesity status of alter at baseline. We were interested in the causal effect of alter’s obesity status at baseline on the ego’s BMI at follow-up. Covariates included age of both ego and alter and ego’s BMI at baseline. Ages were mostly between 19 to 52 (5% and 95% quantile respectively). We mean centered age for both ego and alter for numerical stability.

We first carried out a standard regression-based analysis which did not adjust for the potential homophily bias. More specifically, we first fitted a naive model without distinction among different nameships to the data. Results are given in Table 1. Ego’s BMI at baseline was significantly associated with ego BMI at the follow-up. Adjusting for ego and alter’s age, alter’s obesity status had a significant positively association with the ego’s BMI at follow-up (, with standard error 0.11). This effect was subject to homophily bias. Next, we fitted a naive model stratifying by different nameship types, i.e., we fitted to the data. Results are given in Table 2. Alter’s obesity status at baseline had a significant positive association on ego’s current BMI in a mutual nameship ( with standard error 0.13). Although this model is more informative than the naive model which does not condition on nameship type, such an effect still may not have causal interpretation due to possible homophily bias.

Table 2:

Estimates, standard error and p-values of coefficients in a naive analysis across different nameships: active naming , passive naming and mutual naming

| Est | SE | Est | SE | Est | SE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| −0.05 | 0.25 | 0.84 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.01 | |

| ego’s BMIb BMIb | 0.95 | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.92 | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.91 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| ego’s age | −0.11 | 0.15 | 0.44 | −0.34 | 0.15 | 0.03 | −0.21 | 0.07 | <0.01 |

| alter’s age | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.87 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.64 | 0.20 | 0.07 | <0.01 |

Next, we carried out a negative control regression adjustment for homophily bias. We selected alter’s BMI at follow-up as a negative control variable, i.e., . Alter’s follow-up weight is an appropriate choice of negative control exposure because it cannot be causally related to ego’s contemporaneous weight, therefore satisfying Assumptions 2–3. Such assumptions presume absence of any feedback in alter and ego weight change between baseline and follow-up, which is certainly expected under the sharp null of no contagion effect of weight, but may be violated under the alternative, as discussed in conclusion. Because is associated with ego’s baseline weight, it may be reasonable to expect that it would also be associated with ego’s weight at follow-up , therefore fulfilling Assumption 1. The parameter estimates of the nameship process are given in Table 3. Negative control variable, the alter BMI at follow-up, was significantly associated with nameship process. The odds ratio parameter is also significant in the nameship process, which shows the dependency of nameship between two individuals. The estimated nameship mechanisms were then included as predictors in the outcome regression model under an assumption that does not depend on . Outcome regression model estimates were given in Table 4. Standard errors were estimated following Proposition 3. Our analysis provides formal evidence that homophily bias may be operating in these data. Specifically, a subset of homophily coefficients were marginally significant (for example, with standard error 5.41) indicating at least part of the association between ego and alter’s weight within each dyad may be subject to homophily bias and therefore not causal. In contrast with the naive analysis result, our proposed method finds that alter’s obesity status at baseline had a negative association with ego’s BMI at the follow-up for all three nameships after adjustment for the homophily bias.

Table 3:

Nameship mechanism estimates adjusted for alter’s age gender and .

| Ego model | Alter model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Est | SE | Est | SE | |||

|

|

|

|||||

| 0.19 | 0.07 | <0.01 | −0.22 | 0.02 | <0.01 | |

| −0.35 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.20 | 0.01 | <0.01 | |

| ego’s age | 0.04 | 0.01 | <0.01 | −0.72 | < 0.00 | <0.01 |

| alter’s age | −0.54 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.19 | <0.00 | <0.01 |

| 2.36 | 0.17 | <0.01 | ||||

Table 4:

Estimates, sandwich standard error and p-values of coefficients in homophily-adjusted analysis with an negative control exposure variable across different nameships: active naming , passive naming and mutual naming

| Est | SE | Est | SE | Est | SE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| −0.84 | 0.21 | <0.01 | −0.45 | 0.22 | 0.04 | −0.47 | 0.19 | 0.01 | |

| ego’s BMIb | 0.95 | 0.00 | <0.01 | 0.93 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.91 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| ego’s age | −1.31 | 0.14 | <0.01 | −1.63 | 0.15 | <0.01 | −1.45 | 0.13 | <0.01 |

| alter’s age | −0.53 | 0.08 | <0.01 | −0.39 | 0.08 | <0.01 | −0.31 | 0.06 | <0.01 |

| −1.58 | 7.40 | 0.83 | −3.61 | 8.86 | 0.68 | 9.46 | 5.41 | 0.08 | |

6. DISCUSSION

In this paper, we have proposed a simple regression-based adjustment for homophily bias with a negative control exposure variable . The unmeasured variables and could in principle also directly affect and respectively, in which case, under our negative control assumptions the proposed approach still applies. Our method accounts for homophily, and is not meant to account for unmeasured environment factors that may confounds the relationship of interest. In this work, we assume to be continuous, which is not a stringent assumption given the existing literature on continuous latent factors such as random effects model. Nevertheless, we agree with the reviewer that it is of interest to extend our model to latent class models where indexes discrete classes.

We leverage the null causal effect of a negative control exposure on the outcome in view to identify the causal effect accounting for homophily bias. Our framework relies on an ability to identify relevant negative control exposure, that is a variable known to be associated with the unmeasured factor inducing homophily. A potential concern not explicitly addressed in this paper is that a poor choice of negative control exposure may in fact lead to weak identification analogous to the weak IV problem. We leave exploration of weak negative controls for future research topics.

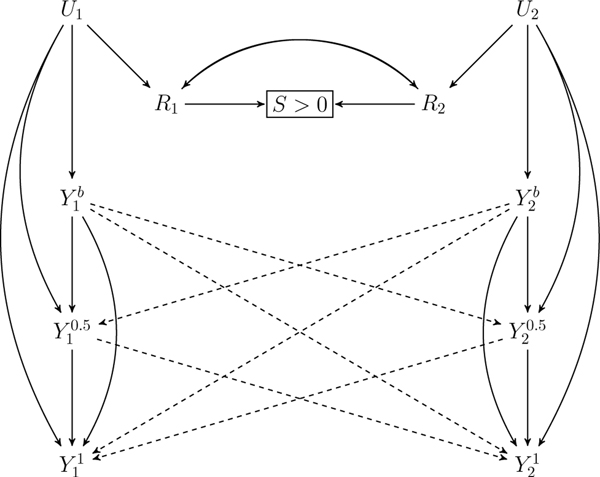

A reviewer noted that our choice of negative control exposure in Framingham application, ego BMI at follow-up is only applicable as a negative control variable if contagion only occurs at discrete times which are directly observed, i.e. ruling out feedback effects alluded to in Section 5. To illustrate this, consider a situation where there is an intermediate time in between baseline and follow-up (shown in Figure 3). Ego and alter BMI can affect the other person’s BMI at a follow-up visit. The dashed line denotes effects between individuals. Although alter BMI at follow-up is unlikely to have a direct causal effect on ego BMI at follow-up, they are both confounded by ego BMI at the intermediate time, . Such confounding could potentially invalidate the negative control assumption 3. This point has also been suggested in Ogburn and VanderWeele (2014): estimation of contagion effects at multiple time points may be complicated by the feedback issue as the entire evolution history need to be considered. The problem of potential uncontrolled confounding may also persist when we have multiple time points as compared with continuous time points. Because the Framingham Offspring Study follow-up was at 4 years post baseline, it is possible that causal contagion effects exist at some intermediate time between the two visits. The assumption of no unmeasured intermediate time with contagion effects is more plausible in the setting where individuals only interact during visits not in between, e.g., patients usually interact with their doctors at clinic visits. It is still notable as suggested in Section 5 that such complication will not occur even in Framingham Offspring Study under the sharp null hypothesis of no contagion effect, in which case, our approach would provide a valid test of the sharp null hypothesis of no contagion within 4 year window between baseline and follow-up.

Figure 3:

Causal diagram illustrating homophily bias for multiple time points.

The parameter of interest is the effect of the obesity status of alter (individual 1) at baseline on ego BMI (individual 2) at time 1. We use to denote the observed weight information on individual at a time point between baseline and follow- up.The dashed line denotes causal effects between individuals. We take as the negative control exposure variable.

The method proposed in this paper is only applicable to dyadic data. It is also of interest to extend our methods to general network data. Identification and estimation is far more challenging in general network settings. We conjecture that leveraging both negative control exposure and outcome variables may potentially be useful in such more complex settings, thus extending result due to Miao et al. (2018) for causal inference of independent identical distributed data subject to unmeasured confounding. We also plan to explore the settings in De Giorgi et al.(2010), who considered a network where peer groups do not overlap fully, and Bramoullé et al. (2009) who considered inference under linear-in-means model where each individual has his own specific reference group. We leave these extension of our methods to general network structure as a future research direction.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to give special thanks to Prof. O’Malley for insightful discussion and his patience and tremendous help on the data analysis section. The authors also thank the editor, associate editor and two reviewers for their insightful comments and helpful suggestions. Lan Liu’s research is supported by NSF DMS 1916013.

References

- Bramoullé Y, Djebbari H, and Fortin B. (2009). Identification of peer effects through social networks. Journal of econometrics 150, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo B, Stinebrickner R, and Stinebrickner T. (2010). Interracial friendships in college. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N. and Fowler J. (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. New England Journal of Medicine 357, 370–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N. and Fowler J. (2008). The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. New England Journal of Medicine 358, 2249–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N. and Fowler J. (2013). Social contagion theory: examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Statistics in Medicine 32, 556–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Cole E. and Fletcher J. (2009). Detecting implausible social network effects in acne, height, and headaches: longitudinal analysis. British Medical Journal 338, 28–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi G, Pellizzari M, and Redaelli S. (2010). Identification of social interactions through partially overlapping peer groups. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2, 241–75. [Google Scholar]

- Elwert F. and Christakis N. (2008). Wives and ex-wives: A new test for homogamy bias in the widowhood effect. Demography 45, 851–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler J. and Christakis N. (2008). Estimating peer effects on health in social networks: a response to cohen-cole and fletcher; and trogdon, nonnemaker, and pais. Journal of Health Economics 27, 1400–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler J, Dawes C, and Christakis N. (2009). Model of genetic variation in human social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, 1720–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgens M. and Halloran M. (2008). Toward causal inference with interference. Journal of the American Statistical Association 103, 832–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, and Cohen T. (2010). Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology 21, 383–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. and Hudgens M. (2014). Large sample randomization inference with interference. Journal of the American Statistical Association 109, 288–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Hudgens M, and Becker-Dreps S. (2016). On inverse probability-weighted estimators in the presence of interference. Biometrika 103, 829–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao W, Geng Z, and Tchetgen Tchetgen E. (2018). Identifying causal effects with proxy variables of an unmeasured confounder. Biometrika 105, 987–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao W. and Tchetgen Tchetgen E. (2017). Invited commentary: bias attenuation and identification of causal effects with multiple negative controls. American journal of epidemiology 185, 950–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogburn E. and VanderWeele T. (2014). Causal diagrams for interference. Statistical Science 29, 559–578. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley A, Elwert F, Rosenquist J, Zaslavsky A, and Christakis N. (2014). Estimating peer effects in longitudinal dyadic data using instrumental variables. Biometrics 70, 506–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl J. (2009). Causality. Cambridge university press. [Google Scholar]

- Shalizi C. and Thomas A. (2011). Homophily and contagion are generically confounded in observational social network studies. Sociological Methods & Research 40, 211–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Miao W, and Tchetgen Tchetgen E. (2020). A selective review of negative control methods in epidemiology. Current Epidemiology Reports. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel M. (2006). What do randomized studies of housing mobility demonstrate?: Causal inference in the face of interference. Journal of the American Statistical Association 101, 1398–1407. [Google Scholar]

- Sofer T, Richardson D, Colicino E, Schwartz J, and Tchetgen Tchetgen E. (2016). On negative outcome control of unobserved confounding as a generalization of difference-in-differences. Statistical Science 31, 348–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchetgen Tchetgen E. (2013). The control outcome calibration approach for causal inference with unobserved confounding. American Journal of Epidemiology 179, 633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchetgen Tchetgen E. and VanderWeele T. (2012). On causal inference in the presence of interference. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 21, 55–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele T, Ogburn E, and Tchetgen Tchetgen E. (2012). Why and when” flawed” social network analyses still yield valid tests of no contagion. Statistics, Politics, and Policy 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele T. and Tchetgen Tchetgen E. (2011). Bounding the infectiousness effect in vaccine trials. Epidemiology 22, 686–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.