Abstract

Introduction Pulmonary embolism (PE) is associated with approximately 10.5% of maternal deaths in the United States. Despite heightened awareness of its mortality potential, there islittle data available to guide its management in pregnancy. We present the case of a massive PE during gestation successfully treated with catheter-directed embolectomy.

Case Presentation A 37-year-old G2P1001 presented with a syncopal episode preceded by dyspnea and chest pain. Upon presentation, she was hypotensive, tachycardiac, and hypoxic. Imaging showed an occlusive bilateral PE, right heart strain, and a possible intrauterine pregnancy. Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin was positive. She was taken emergently for catheter-directed embolectomy. Her condition immediately improved afterward. Postprocedure pelvic ultrasound confirmed a viable intrauterine pregnancy at 10 weeks gestation. She was discharged with therapeutic enoxaparin and gave birth to a healthy infant at 38 weeks gestation.

Conclusion Despite being the gold standard for PE treatment in nonpregnant adults, systemic thrombolysis is relatively contraindicated in pregnancy due to concern for maternal or fetal hemorrhage. Surgical or catheter-based thrombectomies are rarely recommended. Limited alternative options force their consideration, particularly in a hemodynamically unstable patient. Catheter-directed embolectomy can possibly bypass such complications. Our case exemplifies the consideration of catheter-directed embolectomy as the initial treatment modality of a hemodynamically unstable gestational PE.

Keywords: thrombectomy, embolectomy, thrombolytic therapy, pregnancy, pulmonary embolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), is a life-threatening complication of pregnancy that occurs in approximately 5.7 in 10,000 deliveries. 1 Although the incidence of DVT in pregnancy has decreased in recent years, the incidence of PE remains largely unchanged. 1 In the United States, pregnancy-associated emboli are associated with up to approximately 10.5% of maternal deaths from 2017 to 2019. 2 Accurate diagnosis of an acute PE in a pregnant woman therefore becomes extremely important, as it can be difficult to distinguish the signs of a PE from the typical physiologic changes of pregnancy.

An acute PE is categorized as massive when the patient presents with arterial hypotension and cardiogenic shock. 3 When this occurs in pregnancy, management becomes extremely challenging with little data available to guide treatment options. 4 In the nonpregnant population, massive PE can be treated by a combination of anticoagulation, systemic thrombolysis, surgical embolectomy, or catheter-directed techniques. 5 However, in the pregnant population, potential risks of s maternal, placental or fetal hemorrhage, teratogenicity, and fetal loss lead to a limitation of alternative techniques being studied to treat PE. 6 We present a case of massive PE during pregnancy successfully managed by percutaneous catheter-directed embolectomy by entrapment. This case hopes to allow further discussion on using this technique as a first-line therapy for massive PE in pregnancy.

Case Presentation

A 37-year-old, gravida 1 para 1, presented to our emergency department (ED) with a 1-day onset of a syncopal episode after suffering from dyspnea and chest pain. At the time of presentation, the patient confirmed chest pains, palpitations, and dyspnea. She denied fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and leg swelling. Her past medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, bipolar disorder, morbid obesity, chronic microcytic anemia, and endometriosis. Surgical history included a previous uncomplicated cesarean section. Medications included venlafaxine, ziprasidone, and trazodone. Family and social history were unremarkable.

Emergency medical services reported on arrival that the patient's oxygen saturation was 70% on room air and her initial blood pressure (BP) reading was 80/60 mm Hg. She received 100 mL of intravenous fluid (IVF) on her way to the hospital. On presentation in the ED, the patient was afebrile, tachycardic at 120 beats per minute, tachypneic at 31 breaths per minute, BP of 94/73 mm Hg that improved to 122/72 mm Hg after IVF resuscitation, and oxygen saturation of 88% on nonrebreather mask. Physical exam was notable for a diaphoretic woman with obesity in acute respiratory distress. She was placed on bilevel positive airway pressure with her oxygen saturation improving to 100%.

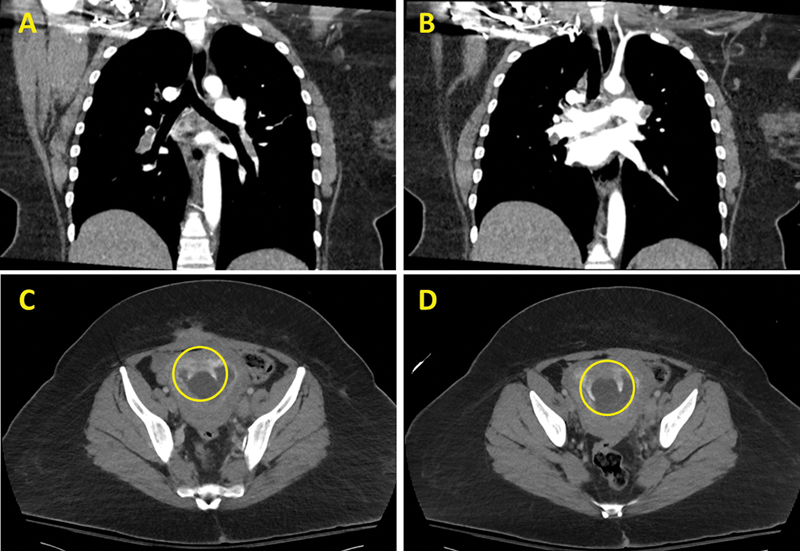

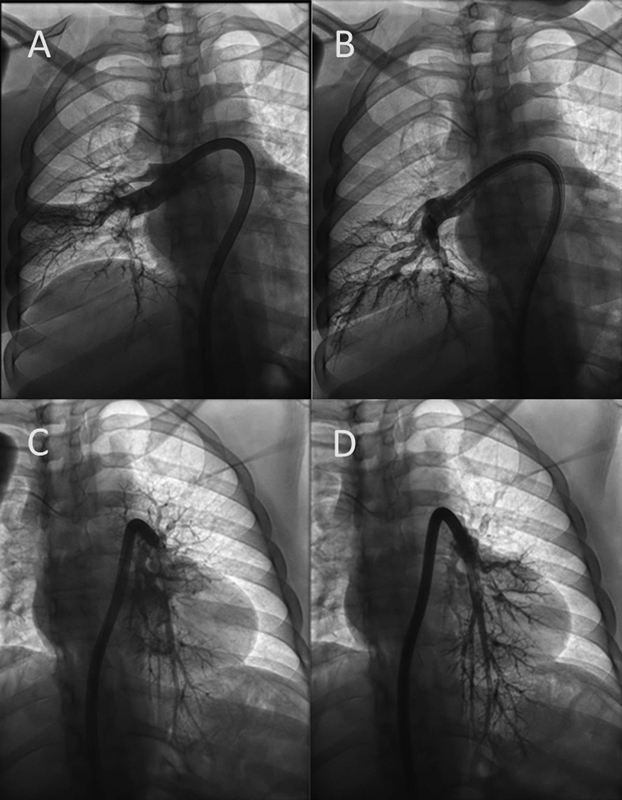

A computed tomography angiogram ( Fig. 1 ) was significant for an occlusive bilateral PE beginning at the first bifurcation of the bilateral pulmonary arteries extending to all lobes of the lung, associated significant right heart strain, and a possible intrauterine pregnancy. Therapeutic anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin drip was started and the patient was admitted to the critical care medicine service for further evaluation and monitoring. At this time, laboratory workup incidentally showed beta-human chorionic gonadotropin at 34,003 mIU/mL (normal < 5 mIU/mL) and severe lactic acidosis of 6.9 mmol/L (normal 0.5–2.2 mmol/L). The patient was taken emergently for catheter-directed embolectomy by entrapment ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography angiography of the chest. ( A and B ) Frontal view showing massive bilateral pulmonary embolism. ( C and D ) Possible intrauterine pregnancy (yellow circle).

Fig. 2.

Selective right and left pulmonary artery angiography . ( A ) Preintervention impaired perfusion to the right lower lobe. ( B ) Postintervention improvement in perfusion to the right lower lobe. ( C ) Preintervention impaired perfusion to the left lower lobe. ( D ) Postintervention improvement in perfusion to the left lower.

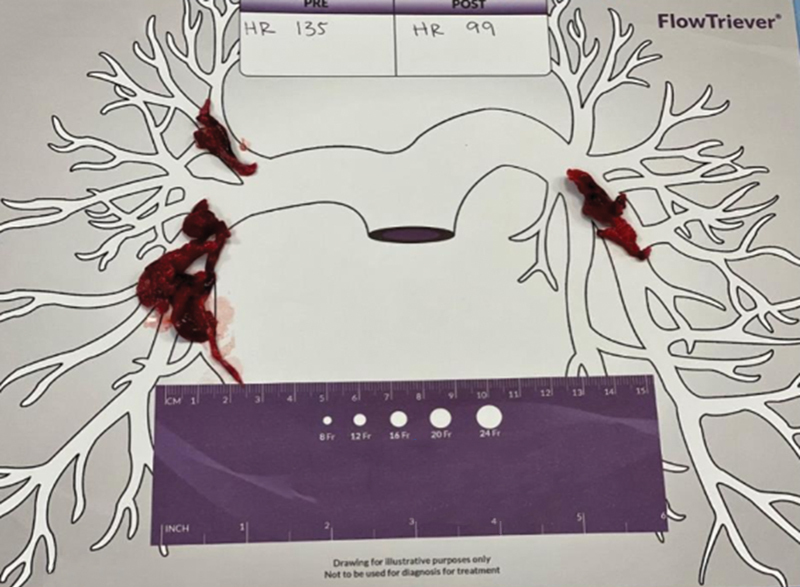

Initial survey of the pulmonary vasculature showed significant clot burden in the bilateral main pulmonary arteries, bilateral lower lobes, and the right upper lobe. Her thrombus was aspirated without complication ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Image of the gross specimen removed after catheter-directed embolectomy by entrapment.

Postprocedure, the patient's condition improved immediately with heartrate decreasing from 135 to 99 bpm and her oxygen requirements decreasing to 2L/min nasal cannula. The patient underwent hypercoagulable workup that was negative. She continued anticoagulation with heparin drip. A pelvic ultrasound confirmed a viable intrauterine pregnancy estimated at 10 weeks gestation. She was discharged on hospital day 4 with therapeutic low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and instructions for close follow-up with maternal–fetal medicine and hematology.

The patient did not have any further coagulation issues throughout her pregnancy and remained compliant on her LMWH. She underwent uncomplicated repeat cesarean section and had a female infant weighing 7 lb and 5.8 oz at 38 weeks gestation.

Discussion

Our patient met the criteria of a massive PE due to her initial BP of 80/60 requiring IVF resuscitation and her associated syncopal episode. 3 Her hemodynamic instability necessitated the consideration of thrombolysis. There is limited data on the efficacy and safety of thrombolysis in pregnancy. Pregnancy is considered a relative contraindication for thrombolysis due to concerns about potential harm to the mother or fetus. 4 However, limited alternative options warrant its consideration, particularly in the setting of a hemodynamically unstable patient. Guidelines specifying the suggested treatment of acute PE with life-threatening hemodynamic instability in pregnancy are detailed below ( Table 1 ):

Table 1. Summary of recommendations regarding use of systemic thrombolysis or catheter-guided techniques in pregnancy.

| Organization | Year | Systemic thrombolysis | Cather-guided techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 7 | 2018 | Thrombolysis indicated for life-threatening or limb-threatening thromboembolism | No discussion |

| American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) 8 | 2012 | Thrombolytic therapy is best reserved for life-threatening maternal thromboembolism | No discussion |

| American Society of Hematology (ASH) 9 | 2018 | If patient has acute pulmonary embolism (PE) and life-threatening hemodynamic instability, administer systemic thrombolysis alongside anticoagulant therapy | More data is required on the effectiveness of catheter-directed thrombolysis in the pregnant population, including patients with limb-threatening ischemia |

| European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 10 | 2018 | Thrombolysis only in patients with severe hypotension or shock | No discussion |

| Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) 11 | 2015 | Patients in shock should be assessed by a multidisciplinary team including the on-call consultant obstetrician and managed on an individual basis regarding intravenous (IV) unfractionated heparin, thrombolytic therapy, or thoracotomy and surgical embolectomy | No discussion |

The most common thrombolytic treatment for PE in pregnancy is catheter-directed thrombolysis, a technique involving the delivery of fibrinolytic drugs through a catheter embedded within a thrombus. 12 Several cases report on the safety and efficacy of pharmacologic thrombolysis to treat massive DVT and PE in pregnancy, but this is considered only when the patient's life or limbs are at risk by many prominent medical professional societies. 7 8 9 10 11 There are also several adverse events associated with pharmacologic thrombolysis in pregnancy, such as major bleeding, uterine or placental hemorrhages, and traumatic hematomas. 13 Tissue plasminogen activator has also been shown to take several hours before appreciable clinical improvement, whereas a patient who underwent percutaneous catheter-directed embolectomy such as ours showed rapid improvement afterward. 14 Surgical thrombectomies during pregnancy have been associated with major bleeding episodes (7/35; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 8–37) and fetal death (2/10; 95% CI: 3–56). 12 Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy notably has a reported maternal survival rate of 100% (7/7' 95% CI: 59–100). 12 This may be due to the technique utilizing a less invasive and targeted approach to remove the patient's clot, thus bypassing the risks of maternal or fetal hemorrhage through surgical injury or movement of fibrinolytic medication into the systemic circulation.

There have been several reported cases of using catheter-directed embolectomy as the first-line option to treat severe PE in pregnancy prior to delivery. 6 12 14 15 16 17 18 In two cases, the patients developed complications such as acute kidney injury, spontaneous abortion, and maternal decompensation requiring further treatment with surgical embolectomy. 16 18 In one case, the patient underwent an emergent cesarean section prior to the thrombectomy. 6 Two cases utilized rheolytic thrombectomy where high-pressured jet streams disrupt the thrombus that is aspirated into the catheter. 12 18 19

Our review of literature also yielded two similar cases of catheter-directed embolectomy by entrapment in a peripartum patient: one published by Yarusi et al and one presented by Nemani et al at a meeting. 19 However, the patient in both cases had to be placed emergently on venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) due to cardiac arrest, which we were able to avoid with our patient. 14 This discrepancy could be due to our patient presenting during the first trimester of her pregnancy and her initial hemodynamic instability leading to a rapid decision to treat with catheter-directed embolectomy. The other two patients were initially hemodynamically stable despite their PE and had spontaneous vaginal deliveries soon after their admissions. 14 However, both patients had cardiac arrests postpartum, necessitating VA-ECMO and later catheter-directed embolectomy. 14 Both patients recovered soon after the procedure and were discharged home on therapeutic LMWH, similar to our patient. 14 The successful outcomes of these three cases indicate there is potential for catheter-directed embolectomy to be considered as a first-line treatment for hemodynamically unstable peripartum and postpartum patients with acute PE.

Complications associated with catheter-directed embolectomy include clot dislocation, damage to the heart or vasculature, acute kidney injury, and pulmonary artery dissection. 20 Despite these risks, catheter-directed embolectomy can be considered as an initial treatment option in pregnancy where thrombolytics and surgical thrombectomy place significant risk and complications for both the mother and fetus because it can avoid potentially introducing fibrinolytic medications to the systemic circulation and injury or infection related to surgery. Further discussions and research should attempt to create evidence-based guidelines, involving the input of specialists in obstetrics, cardiology, and critical care medicine. However, this case introduces the possibility of adding catheter-directed embolectomy to the treatment algorithm of massive PE in pregnancy.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Abe K, Kuklina E V, Hooper W C, Callaghan W M. Venous thromboembolism as a cause of severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43(04):200–204. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System | Maternal and Infant Health | CDCPublished March 31, 2023. Accessed April 15, 2024 at:https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm

- 3.Kucher N, Goldhaber S Z. Management of massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2005;112(02):e28–e32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.551374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hobohm L, Farmakis I T, Münzel T, Konstantinides S, Keller K. Pulmonary embolism and pregnancy-challenges in diagnostic and therapeutic decisions in high-risk patients. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:856594. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.856594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hobohm L, Keller K, Valerio L et al. Fatality rates and use of systemic thrombolysis in pregnant women with pulmonary embolism. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7(05):2365–2372. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato T, Kobatake R, Yoshioka R et al. Massive pulmonary thromboembolism in pregnancy rescued using transcatheter thrombectomy. Int Heart J. 2007;48(02):269–276. doi: 10.1536/ihj.48.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics . ACOG practice bulletin no. 196: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(01):e1–e17. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bates S M, Greer I A, Middeldorp S, Veenstra D L, Prabulos A M, Vandvik P O.VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines Chest 2012141(2, Suppl):e691S–e736S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates S M, Rajasekhar A, Middeldorp S et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: venous thromboembolism in the context of pregnancy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3317–3359. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ESC Scientific Document Group . Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink J W, Bauersachs J et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(34):3165–3241. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomson A J.Thromboembolic Disease in Pregnancy and the Puerperium: Acute ManagementPublished online April 13, 2015. Accessed April 15, 2024 at:https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/thrombosis-and-embolism-during-pregnancy-and-the-puerperium-acute-management-green-top-guideline-no-37b/

- 12.Martillotti G, Boehlen F, Robert-Ebadi H, Jastrow N, Righini M, Blondon M. Treatment options for severe pulmonary embolism during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(10):1942–1950. doi: 10.1111/jth.13802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez D, Jerjes-Sanchez C, Fonseca S et al. Thrombolysis in massive and submassive pulmonary embolism during pregnancy and the puerperium: a systematic review. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(04):929–941. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yarusi B B, Jagadeesan V S, Schimmel D R. Not for the faint of heart: a rapidly evolving case of syncope during pregnancy. Circulation. 2020;142(05):501–506. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenblum J K, Cynamon J. Mechanical and enzymatic thrombolysis of acute pulmonary embolus: review of the literature and cases from our institution. Vascular. 2008;16(04):213–218. doi: 10.2310/6670.2008.00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodward D K, Birks R J, Granger K A. Massive pulmonary embolism in late pregnancy. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45(09):888–892. doi: 10.1007/BF03012225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dukkipati R, Yang E H, Adler S, Vintch J. Acute kidney injury caused by intravascular hemolysis after mechanical thrombectomy. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2009;5(02):112–116. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valerio L, Klok F A, Barco S.Immediate and late impact of reperfusion therapies in acute pulmonary embolism Eur Heart J Suppl 201921(Suppl I):I1–I13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nemani L, Al-Qamari A, Budd A.365: Use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for massive pulmonary embolus in a peripartum patient Critical care medicine 202149011–172.33177362 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo W T, Gould M K, Louie J D, Rosenberg J K, Sze D Y, Hofmann L V. Catheter-directed therapy for the treatment of massive pulmonary embolism: systematic review and meta-analysis of modern techniques. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20(11):1431–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]