Abstract

We investigated whether interleukin-6 (IL-6) was required for the development of immunoglobulin A (IgA)- and T-helper 1 (Th1)-associated protective immune responses to rotavirus by using adult IL-6-deficient mice [BALB/c and (C57BL/6 × O1a)F2 backgrounds]. Naive IL-6− mice had normal frequencies of IgA plasma cells in the gastrointestinal tract. Consistent with this, total levels of IgA in fecal extracts, saliva, and sera were unaltered. In specific response to oral infection with rhesus rotavirus, IL-6− and IL-6+ mice exhibited efficient Th1-type gamma interferon responses in Peyer's patches with high levels of serum IgG2a and intestinal IgA. Although there was an increase in Th2-type IL-4 in CD4+ T cells from IL-6− mice following restimulation with rotavirus antigen in the presence of irradiated antigen-presenting cells, unfractionated Peyer's patch cells failed to produce a significant increase in IL-4. Moreover, virus-specific IgG1 in serum was not significantly increased in IL-6− mice in comparison with IL-6+ mice. Following oral inoculation with murine rotavirus, IL-6− and IL-6+ mice mediated clearance of rotavirus and mounted a strong IgA response. When IL-6− and IL-6+ mice [(C57BL/6 × O1a)F2 background] were orally inoculated with rhesus rotavirus and later challenged with murine rotavirus, all of the mice maintained high levels of IgA in feces and were protected against reinfection. Thus, IL-6 failed to provide unique functions in the development of IgA-secreting B cells and in the establishment of Th1-associated protective immunity against rotavirus infection in adult mice.

In humans, domestic animals, and mice, rotavirus infection is limited to the mature enterocytes of the tips of the intestinal villi and, in the young, can lead to severe gastroenteritis (11, 43). Virus-specific CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and antibody all participate in resolution of infection or protection against reinfection in mice (15–17, 27, 29). However, the mechanisms that govern how each response is induced and maintained are unclear. Moreover, the role of each effector response in protection against natural rotavirus infection has not been determined, thereby hindering the development of vaccines that could potentially boost the most favorable immune response.

Circulating and intestinal antibodies correlate with protection against rotavirus infection and disease in adult humans (42). In the mouse model of rotavirus infection, rotavirus illness could be prevented by passive transfer of antibody from immunized dams to suckling pups through breast milk (33, 34). CD8-positive T cells were also shown to protect against rotavirus-induced diarrhea following passive transfer from immunized mice to pups (35), indicating that both antibody and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are capable of preventing rotavirus disease in mice. Immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibody in serum and stool samples correlates best with protection against reinfection (14, 28). Studies with B-cell-deficient mice have confirmed that antibody plays a role in resolution of primary rotavirus infection as well as in protection from reinfection (15, 27). In one study, nonneutralizing IgA monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) directed against the group antigen (Ag), VP6, were protective in mice (8). Similar to the results found in mice, antibody responses were crucial for the normal resolution of rotavirus infection in calves (36). However, despite the apparent importance of antibody, specifically of the IgA class, there is little information regarding the regulatory requirements for rotavirus-specific IgA, especially in regard to the role of individual cytokines.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a cytokine with multiple biological functions, which include regulating a variety of immune responses within the host (41). IL-6 has been shown to stimulate IgA B-cell development in vitro (4, 5, 10, 32). In vivo studies carried out with IL-6-deficient (IL-6−) mice have revealed that some but not all experimental infections or immunizations require IL-6 for mucosal IgA responses (6, 37, 39). IL-6 had positive effects on CTL- and T helper (Th) cell-dependent activities (23, 39). In this regard, IL-6 was essential for a protective Th1 cell response to Candida albicans (39) but was unnecessary for induction of a similar response to Leishmania major (31). IL-6-deficient mice also had increased susceptibility to Listeria monocytogenes (13, 23) and vaccinia virus (23, 37) infections but not to Helicobacter felis (6). The inability of IL-6-deficient mice to control vaccinia virus correlated with an impaired cell-mediated immune response (23).

The studies reported here were undertaken to determine whether IL-6 was required for IgA B-cell and Th1 cell development in mice orally inoculated with rhesus rotavirus (RRV) and murine rotavirus strains. Furthermore, we examined whether IL-6 was necessary in controlling rotavirus infections. The experiments demonstrate that IL-6− and IL-6+ mice are equally susceptible to murine rotavirus infection strain ECw. Furthermore, mice infected with RRV were fully protected against challenge with murine rotavirus strain ECw. Protection correlated with vigorous rotavirus-specific IgA and Th1 cell activity in both IL-6− and IL-6+ mice. Our data argue against a unique role for IL-6 in protective immune responses to an enteric virus in an adult mouse model of rotavirus infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

The method for generating the IL-6-deficient mice [BALB/c background H-2d and (C57BL/6 × 129/O1a)F2 background H-2b] was described previously (13). C57BL/6 × 129/O1a mice were bred as separate IL-6−/− and IL-6+/+ colonies. All BALB/c mice used in these studies were generated from IL-6+/− parents, resulting in IL-6+ (i.e., IL-6+/+ and IL-6+/−) and IL-6− (i.e., IL-6−/−) phenotypes. All mice used in these studies were adults, 8 to 16 weeks of age. IL-6− mice were identified by their failure to produce IL-6 in serum in response to intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide, as described previously (13). Mice were fed an autoclaved diet and water ad libitum and were bred and housed in horizontal laminar flow cabinets. Mice were routinely screened for viral, bacterial, and parasitic pathogens by antibody testing and by histopathology. The guidelines proposed by the Committee for the Care of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission of Life Sciences, National Research Council, were followed in order to properly care for the mice. We have used both mouse strains for all of the studies described in this paper except for the challenge experiments, in which we used only the (C57BL/6 × O1a)F2 mice.

Viruses and oral inoculation.

Tissue culture-adapted RRV (G3, P3) was grown and counted (2 × 108 PFU/ml) in MA-104 cells (21). Wild-type murine rotavirus strain ECw (G3, P16) was an intestinal homogenate, and its 50% shedding dose (SD50) titer was determined by oral inoculation of mice with serial 10-fold dilutions (7). Mice were orally inoculated with 107 PFU of RRV per mouse and, in some experiments, challenged 6 weeks later with 104 SD50 of murine rotavirus per mouse by gut intubation (100 μl). Some mice received only a primary oral inoculation with 104 SD50 of murine rotavirus per mouse. Mice were euthanized 6 weeks after the primary inoculation of RRV for analysis of Th cell responses. The comprehensive analyses of primary immune responses were conducted with RRV-inoculated mice rather than ECw-inoculated mice to reduce the risk of murine rotavirus spread to other mouse colonies in our animal facilities. However, rotavirus shedding and IgA responses were evaluated in groups of IL-6+ and IL-6− mice that received only a primary oral dose of rotavirus strain ECw as part of our challenge studies.

Analysis of viral Ag shedding in feces by ELISA.

Viral Ag in fecal samples was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (7). Microtiter plates (Dynatech, McLean, Va.) were coated with rabbit antirotavirus serum and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk (NFDM). Suspended stool samples were added to plates in 0.5% NFDM. For detection, guinea pig antirotavirus serum and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) in 1% NFDM were employed. ABTS (2,2′-azino-di-[3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonate] substrate; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) was used for color development. The fecal viral Ag shedding data were expressed as net optical density (OD) at 405 nm, which equaled the OD reading from fecal samples minus the background OD reading from wells that did not contain a fecal suspension. The OD value was obtained by developing the plates for 10 min and stopping the reaction with 10% dodecyl sulfate. A sample was considered positive if the OD reading was at least 0.1 absorbance unit greater than the OD reading for naive mice on the day of infection. The mean OD value for naive mice on the day of the infection ranged from 0.10 to 0.30. The adult mouse model was used in all the studies described here. Since adult mice become infected with rotavirus but do not develop disease, this model uses protection against infection as its endpoint.

Analysis of antibody isotypes and IgG subclasses.

Rotavirus-specific antibodies in serum, fecal extracts, and 7-day culture supernatants were determined by ELISA (17). Falcon Microtest III microtiter plates (Becton Dickinson, Oxnard, Calif.) were coated with diluted hyperimmune rabbit antirotavirus serum (R2; 1:2,000) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were blocked with 5% NFDM for 2 h at room temperature and then incubated with a 1:8 dilution of RRV stock virus overnight at 4°C. Dilutions of samples were added to the plates and incubated for 4 h at room temperature. Detection consisted of peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse μ-, α-, and γ-chain-specific Abs (1 μg/ml) (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) and the chromogenic substrate ABTS with H2O2 (Moss, Inc., Pasadena, Md.). For IgG subclass determinations, biotinylated MAbs specific for IgG1 (2 μg/ml), IgG2a (1 μg/ml), IgG2b (0.5 μg/ml), and IgG3 (1 μg/ml) (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) and streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase were employed (40). Endpoint titers for serum and fecal extracts were expressed as the last dilution yielding an OD at 405 nm of >0.2 U above negative control values (i.e., naive mice) after a 90-min incubation period. For measurement of rotavirus-specific IgA in fecal samples collected during the challenge study, results were expressed as net OD readings as described above for the Ag ELISA. To measure total Ig in fecal extracts, saliva, serum, and culture supernatants, the coating phase consisted of goat anti-mouse IgA, IgM, or IgG (Southern Biotechnology Associates) at 2 μg/ml. Total Ig concentrations were estimated by using standard curves generated with purified mouse IgA, IgM, and IgG (Southern Biotechnology Associates). Data were recorded as nanograms of IgA, IgM, or IgG per milliliter.

B-cell enzyme-linked immunospot for antibody-forming cells.

An enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT) was used to quantitate numbers of IgG, IgA, and IgM antibody-forming cells (AFC) present in spleens, Peyer's patches (PP), and the lamina propria of the small intestine of mice orally immunized with RRV. Single-cell suspensions of spleen, PP, and lamina propria cells were prepared as previously described (40) and resuspended in complete medium (RPMI 1640; Cellegro Mediatech, Washington, D.C.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. Nitrocellulose-based plates (96 wells) were coated with 0.5 μg of purified recombinant virus-like particles (VLP) containing VP2 and VP6 in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and control wells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS. VLP were made by coinfection of Sf9 insect cells with recombinant baculovirus that express the inner-layer VP2 and VP6 proteins from the RF strain of bovine rotavirus, as previously described (19). VLP were purified twice on a cesium chloride gradient, and their purity was verified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The VLP from the RF strain of bovine rotavirus could be used because VP2 and VP6 are highly cross-reactive among the group A rotaviruses and elicit the strongest antibody responses in mice (22). In preliminary studies, we showed that the plates coated with VLP exhibited 90% of the spots observed in plates coated with whole RRV; therefore, we used only VLP to coat ELISPOT plates in the present study. For the ELISPOT assays, serial 10-fold dilutions of cells (starting at 106 cells/well) were added to the wells in duplicate and incubated for 6 h. Individual AFC were detected with peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse γ-, α-, and μ-chain-specific antibodies (1 μg/ml) (Southern Biotechnology Associates) and visualized by adding the chromogenic substrate 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Moss, Inc.).

Rotavirus-specific restimulation of PP cells.

Single-cell suspensions of spleens and PP cells (3 × 106/ml) from infected mice were cultured (1 ml/well) in flat-bottomed 24-well tissue culture plates (Corning Glass Works, Corning, N.Y.) in complete medium and restimulated with psoralen-inactivated RRV or rotavirus VLP. Control wells received psoralen-inactivated Ag prepared from mock-infected MA104 cells. To prepare psoralen-inactivated RRV, the RRV preparation was concentrated on a sucrose gradient, and then psoralen was added to a final concentration of 40 μg/ml and kept on ice for 15 min prior to exposure to a UV lamp for 20 min at a distance of 5 cm (20). The mock preparation was similarly inactivated. The inactivated RRV preparation had less than 102 PFU/ml. For optimal cytokine responses, cells were stimulated with a 1:102 dilution of each inactivated Ag preparation. For optimal antibody responses, cells were stimulated with a 1:104 dilution of Ag. Culture supernatants were collected for cytokine analysis on days 2, 4, and 6 and for antibody detection on day 7. AFC in cell suspensions were assayed by ELISPOT on day 5. These Ag doses and assay times were optimized in our preliminary studies.

Assessment of rotavirus-specific CD4+ T-cell responses.

CD4+ T cells from nonadherent PP cell suspensions were purified by a magnetic activated cell sorter system (Stefen Miltenyi Biotechnologic Equipment, Bergish-Gladbach, Germany) (40). Cells were passed through the magnetized column after incubation with biotinylated anti-L3T4 (GK 1.5) and streptavidin-conjugated microbeads. This procedure yielded CD3+ CD4+ CD8− T-cell preparations of >95%. CD4+ T cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) were restimulated in vitro with inactivated RRV (2 × 108 FFU/ml before inactivation) or purified VLP proteins (5 μg/ml) in the presence of recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2; 10 U/ml; PharMingen) and T-cell-depleted, irradiated (3,000 R) splenic Ag-presenting cells (APC) from naive mice. T-cell-depleted APC were obtained by incubation with Thy-1-specific antibody followed by complement lysis. Cells were cultured in 24-well (1 ml/well) tissue culture plates (Corning Glass Works). Culture supernatants were removed after 2, 4, and 6 days and assayed for cytokine concentration as described below. Control wells consisted of cells only or cells incubated with mock Ag preparations. All cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Cytokine ELISA.

Cytokine levels in culture supernatants were determined by ELISA for the detection of murine gamma interferon (IFN-γ), IL-4, and IL-6 as described in our previous study (40). Falcon Microtest III plates (Becton Dickinson) were coated with the appropriate concentration of anticytokine antibody. Cytokines were detected with the corresponding biotinylated anticytokine MAb (PharMingen) and peroxidase-labeled anti-biotin MAb (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, Calif.). Standard curves were generated by using murine rIFN-γ and rIL-6 (Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.) and rIL-4 (Endogen, Boston, Mass.). The ELISAs were capable of detecting 0.39 U of IFN-γ, 10 pg of IL-4, and 4 U of IL-6 per ml. For statistical analysis, levels of cytokine below the detection limit were recorded as one-half the detection limit (e.g., IFN-γ = 0.20 U/ml).

Statistics.

The significance of the difference between groups was evaluated by the Mann-Whitney U test for unpaired samples using a Statview II Program designed for Macintosh computers.

RESULTS

IgA production proceeds efficiently in naive IL-6− mice.

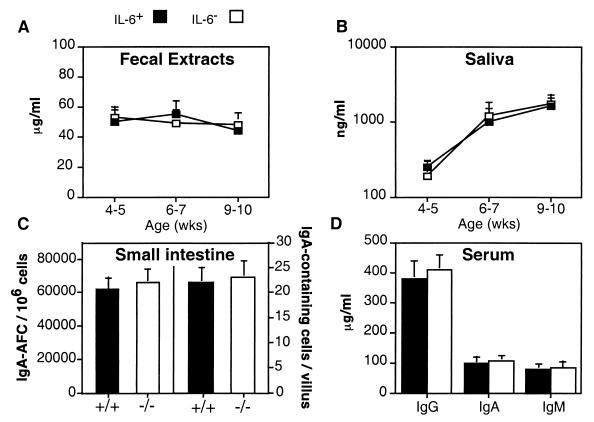

Our initial effort was to characterize total IgA levels in fecal extracts and saliva by ELISA. With sample sizes of more than 50 BALB/c mice, total IgA levels in fecal and saliva samples were similar for IL-6− and IL-6+ mice (Fig. 1A and B). IL-6− and IL-6+ mice exhibited normal adult levels of IgA in feces as early as 4 to 5 weeks of age, whereas IgA levels in saliva continued to increase to weeks 9 to 10. The numbers of IgA-AFC and IgA-containing cells in the gastrointestinal tract were enumerated by an isotype-specific ELISPOT assay and immunohistochemical analysis, respectively, at 8 to 10 weeks of age. By these methods, it was found that the frequencies of IgA-AFC and IgA-containing cells in the intestinal tract were essentially the same in IL-6− and IL-6+ mice (Fig. 1C). Also, there were no reductions in total levels of IgA, IgG, and IgM in serum of IL-6− mice (Fig. 1D). Similar results were obtained for IL-6− and IL-6+ mice derived from (C57BL/6 × 129/O1a)F2 breedings (data not shown). Together, these findings indicate that IgA B-cell development and IgA secretion proceeded efficiently in the gastrointestinal tract of IL-6− mice.

FIG. 1.

Mucosal IgA and systemic IgG, IgA, and IgM B-cell development is normal in naive IL-6− BALB/c mice. Total levels of IgA in fecal extract (A) and saliva samples (B) and IgG, IgA, and IgM in serum samples (D) were measured by ELISA. Frequencies of IgA AFC in the intestinal lamina propria (C; left side of graph) and IgA-containing cells in intestinal villi (C; right side of graph) were determined by ELISPOT and immunohistochemistry, respectively. (A, B, and D) From 30 to 50 mice were analyzed. (C) Three experiments of three to five mice per group (± standard deviation [SD]). There were no statistically significant differences between IL-6− and IL-6+ mice. Similar results were obtained with IL-6− and IL-6+ mice of a mixed (C57BL/6 × O1a)F2 background (data not shown).

Rotavirus-specific IgA responses remain vigorous in the absence of IL-6.

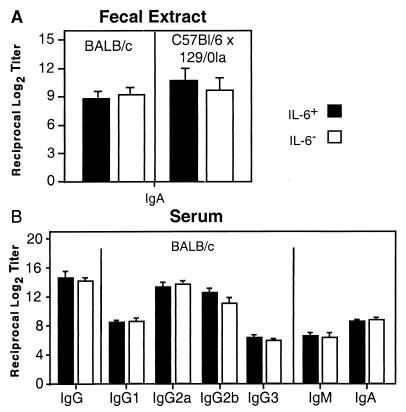

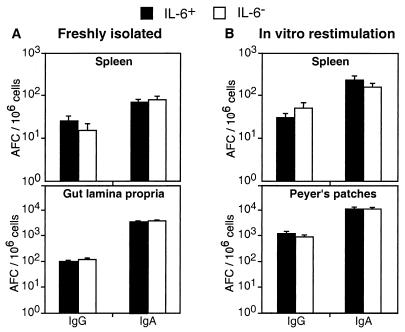

To test whether IL-6 was required for specific IgA antibody to rotavirus, IL-6− and IL-6+ BALB/c and (C57BL/6 × 129/O1a)F2 mice were orally inoculated with a single dose of RRV (107 PFU/mouse). Fecal samples were collected at weekly intervals, and Ag-specific IgA titers were determined by ELISA. IL-6− mice exhibited virus-specific IgA titers in fecal extracts comparable to those of IL-6+ mice throughout the 6-week study (Fig. 2). We also found that IL-6− mice had unaltered rotavirus-specific IgG, IgG subclass, IgM, and IgA titers in serum samples by ELISA (Fig. 2B). To determine the frequency of isotype-specific AFC, freshly isolated splenic cells and intestinal lamina propria cells were subjected to ELISPOT assays. As expected, the frequencies of virus-specific IgA-, IgG-, and IgM-AFC were similar in mucosal and systemic tissues of IL-6− and IL-6+ mice (Fig. 3A). Moreover, splenic and PP cells from IL-6+ and IL-6− mice produced substantial yet comparable amounts of IgA and IgG in vitro in response to restimulation with a 1:104 dilution of psoralen-inactivated rotavirus Ag (Fig. 3B). Thus, IL-6 was not required for an efficient rotavirus-specific recall IgA response. It should be noted that we performed four replicate experiments with the BALB/c IL-6− mice and six replicate experiments with the mixed-background IL-6− mice. In these studies, there was no evidence to support an essential role for IL-6 in the development of virus-specific intestinal IgA and systemic IgG responses following live RRV infection.

FIG. 2.

IL-6 is nonessential for development of optimal rotavirus-specific mucosal and systemic antibody responses. Fecal extracts (A) and serum samples (B) were from IL-6− and IL-6+ mice orally inoculated with RRV (107 FFU). Samples were collected 6 weeks after inoculation. Titers of IgG, IgA, and IgM isotypes and IgG subclasses were measured by ELISA and are representative of three separate experiments (± SD) for RRV-infected mice. Titers of antigen-specific IgA in fecal extracts are shown for mice on BALB/c (five experiments with three to five mice per group) and mixed (C57BL/6 × 129/O1a)F2 backgrounds (eight experiments with three to five mice per group). For serum samples, only results for BALB/c mice are shown; however, IL-6− and IL-6+ mice on a mixed background showed no differences as well. Values for IL-6− and IL-6+ mice were not statistically different.

FIG. 3.

Normal frequencies of rotavirus-specific IgG- and IgA-AFC in mucosal and systemic tissues of IL-6− mice. IL-6− and IL-6+ BALB/c mice were orally inoculated with RRV (107 FFU). Freshly isolated splenic and intestinal lamina propria cells were assayed for numbers of IgG- and IgA-AFC at 6 weeks by ELISPOT (A). At this time, splenic and PP cells were restimulated in vitro with RRV Ag (1:104 dilution) and assayed for numbers of IgG- and IgA-AFC 5 days later by ELISPOT (B). Results are from three experiments (± SD; three to five mice per group). Values for IL-6+ and IL-6− mice were not statistically different. Results for BALB/c mice are shown; however, IL-6− and IL-6+ mice on a mixed background showed no differences as well.

Development of Th1 cell response to rotavirus in the absence of IL-6.

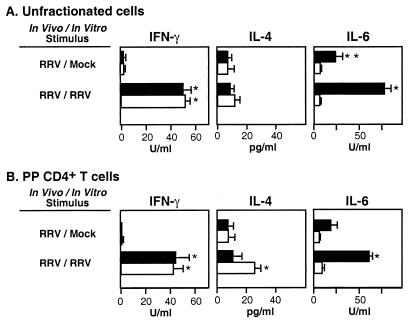

Experiments were carried out to determine the role of IL-6 in regulating the development of Th1 and Th2 responses to rotavirus. For these studies, unfractionated PP cells were obtained from IL-6− and IL-6+ BALB/c mice 6 weeks after primary oral inoculation with RRV (107 PFU/mouse) and restimulated in vitro with psoralen-inactivated RRV Ag. On select days, cytokine-specific protein was assayed by ELISA. IFN-γ levels in culture supernatants of cells from IL-6− and IL-6+ mice were both elevated and of a similar magnitude (Fig. 4A). In contrast, IL-4 levels were not significantly elevated in culture supernatants (<15 pg/ml). To demonstrate that IFN-γ and IL-4 were produced by Th cells, CD4+ T cells were purified from virus-infected mice and restimulated in vitro with RRV Ag in the presence of irradiated (3,000 R) APC from IL-6+ mice. As before, IFN-γ levels were elevated in CD4+ T-cell cultures derived from both IL-6− and IL-6+ mice (Fig. 4B). However, the pattern of IL-4 production in CD4+ T cells was altered. The findings showed that IL-6− mice but not IL-6+ mice produced significantly increased amounts of IL-4 in CD4+ T-cell cultures. These results suggested that in the absence of IL-6, rotavirus elicited increased numbers of memory Th cells capable of secreting IL-4 upon restimulation. Overall, we conclude that IL-6 was not essential for induction of an efficient Th1-type IFN-γ response to rotavirus.

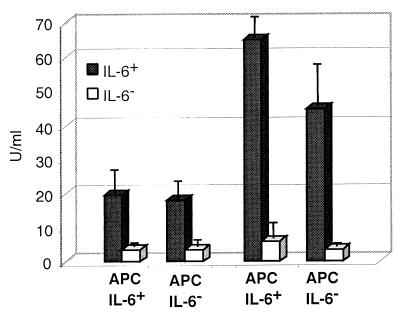

FIG. 4.

Effect of rotavirus Ag on the induction of Th1-type (IFN-γ) and Th2-type (IL-4 and IL-6) cytokine secretion by unfractionated cells (A) and CD4+ T cells (B) from PP of IL-6− (open bars) and IL-6+ (solid bars) mice (BALB/c background) orally inoculated with RRV (107 FFU). Cells were isolated from mice 6 weeks after rotavirus infection and restimulated in vitro with RRV Ag (1:102 dilution). Cytokine levels shown are from 4-day culture supernatants as determined by ELISA and represent three experiments of three to five mice per experiment (± SD). ∗, P < 0.01 versus mock-stimulated cells. ∗∗, P < 0.01 versus mock-stimulated cells from IL-6−/− mice. The significant increase in IL-4 in CD4+ T cells was not observed in culture supernatants at days 2 and 6 (data not shown). Similar results were obtained with IL-6− and IL-6+ mice of a mixed (C57BL/6 × O1a)F2 background (data not shown).

Analyses of IL-6 production in vitro confirmed that only cell suspensions from IL-6+ mice produced detectable amounts of IL-6 (Fig. 4). In additional experiments, we examined whether the source of APC (i.e., IL-6− or IL-6+ mice) could influence the secondary response of CD4+ T cells in vitro. Irradiated splenic APC from IL-6− and IL-6+ mice were cultured with CD4+ T cells from rotavirus-inoculated IL-6− and IL-6+ mice and restimulated with RRV Ag as before. Although irradiated APC from IL-6+ mice contributed some IL-6 into the culture supernatants (Fig. 5), there was no significant change in the IFN-γ and IL-4 response profiles when CD4+ T cells from IL-6− and IL-6+ mice were incubated in the presence of APC from IL-6− mice (data not shown). Thus, we can conclude that IL-6 production from APC did not alter the Th cell response in our studies. Also, the same overall IFN-γ and IL-4 responses were obtained when the in vitro Ag was VLP and when PP CD4+ T cells were from IL-6− and IL-6+ mice of a (C57BL/6 × 129/O1a)F2 background (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Irradiated (3,000 R) APC from IL-6+ mice produce low levels of IL-6 in cultures of restimulated CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells from RRV-inoculated IL-6− and IL-6+ mice (BALB/c background) were restimulated with RRV Ag in the presence of APC from either IL-6+ or IL-6− mice. The leftmost two columns of the graph are data for cells stimulated with mock Ag. The rightmost two columns are data for cells stimulated with RRV Ag. Cell cultures were restimulated with a 1:102 dilution of RRV Ag. The results are from one representative experiment with five mice (± SD).

IL-6 is not required to mediate clearance of primary murine rotavirus infection.

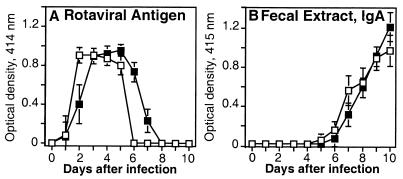

To evaluate whether IL-6 was necessary for clearance of primary murine rotavirus infection, adult IL-6− and IL-6+ (C57BL/6 × 129/O1a)F2 mice were orally inoculated with murine rotavirus strain ECw (104 SD50), and virus shedding was measured in fecal specimens for 10 days by capture ELISA. IL-6+ and IL-6− mice were equally susceptible to primary murine rotavirus infection (Fig. 6A). Moreover, both groups of mice exhibited a similar peak level of viral shedding in fecal specimens and efficiently resolved infection within 6 to 8 days. Primary murine rotavirus clearance coincided with an increase in rotavirus-specific IgA in fecal specimens beginning on day 5 (Fig. 6B). These results provided further evidence that mucosal rotavirus-specific IgA responses were unimpaired in the absence of IL-6.

FIG. 6.

Role of IL-6 in primary murine rotavirus clearance. Groups of IL-6− (□) and IL-6+ (■) (C57BL/6 × 129/O1a)F2 mice were orally inoculated with murine rotavirus strain ECw (104 SD50). Rotaviral Ag shedding (A) and IgA titers (B) in fecal samples were measured daily for 10 days after challenge. Fecal rotavirus Ag and Ag-specific fecal IgA were measured as described in Materials and Methods, and the results represent one experiment with four or five mice (± SD). These experiments were not conducted in IL-6− and IL-6+ mice of a BALB/c background.

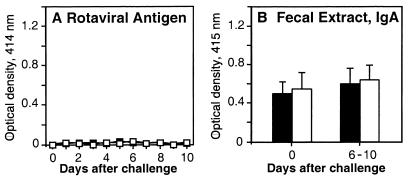

IL-6 is nonessential for the induction of protective immune responses to rotavirus.

We next investigated the role of IL-6 in protective immunity to rotavirus. To date, protection against reinfection has correlated best with intestinal IgA in the adult mouse model (14, 15). IL-6− and IL-6+ (C57BL/6 × 129/O1a)F2 mice were orally inoculated with RRV (107 PFU/mouse) at 8 to 10 weeks of age and 6 weeks later were challenged with murine rotavirus strain ECw (104 SD50). The present study demonstrated that IL-6+ and IL-6− mice were protected against reinfection, according to the absence of detectable virus in fecal samples collected until day 10 (Fig. 7A). Again, although rotavirus-specific IgA responses were variable after infection, there were no significant differences between IL-6+ and IL-6− mice in these responses (Fig. 7B). Moreover, IgA responses were not significantly increased after challenge, providing more evidence that little or no additional rotaviral replication occurred. Next, the primary RRV inoculation dose was lowered by 10-fold to 106 PFU/mouse. Most neonatal BALB/c mice receiving this dose of RRV in a previous study shed virus in feces following murine rotavirus challenge as adults (15). However, in the present study, adult IL-6+ and IL-6− mice immunized with this lower dose of RRV were protected against reinfection with murine rotavirus (data not shown). Overall, these results showed that IL-6 was not necessarily required for induction of protective immune responses to rotavirus.

FIG. 7.

Role of IL-6 in protective immunity to rotavirus. Groups of IL-6− (□) and IL-6+ (■) (C57BL/6 × 129/O1a) mice were orally inoculated with RRV (107 FFU) and 6 weeks later challenged with murine rotavirus strain ECw (104 SD50). Rotaviral Ag shedding (A) and IgA titers (B) in fecal samples were measured on the day of challenge and daily for 10 days after challenge. Fecal rotavirus Ag and Ag-specific fecal IgA were measured as described in Materials and Methods, and the results represent one experiment with three to five mice (± SD). These experiments were not conducted in IL-6− and IL-6+ mice of a BALB/c background.

DISCUSSION

Optimal control of rotavirus depends on B cells (e.g., intestinal IgA) (15, 27), CD4+ T cells (29), and CD8+ T cells (15, 17, 27, 29). However, few studies have examined the role that cytokines play in regulating rotavirus-specific immune responses, especially in regards to Th1 or Th2 cell differentiation. IL-6 is a multifunctional cytokine that is known to help shape host inflammatory and antibody- and cell-mediated immune responses (41). Therefore, we questioned whether IL-6 regulates specific immune responses to rotavirus. However, our studies demonstrate that IL-6 is nonessential for control of intestinal rotavirus infection. IL-6-deficient and control IL-6+ adult mice develop rotavirus-specific antibody and Th1 cells with similar efficiency in the gastrointestinal tract. Moreover, both IL-6− and IL-6+ mice are immune to reinfection in the adult mouse model.

IL-6 is essential for control of some viral (23, 37), bacterial (6, 13, 23, 25), and fungal (39) infections, primarily through its effects on inflammatory and cell-mediated immune responses. For example, IL-6− mice exhibit increased susceptibility to L. monocytogenes as a consequence of impaired neutrophilia or neutrophil function (13). In addition, deficient Th1-cell and neutrophil activity accounted for increased susceptibility to C. albicans in IL-6− mice (39). In contrast, control of Leishmania major correlated with induction of an efficient Th1-cell response in IL-6− mice (31). Our present observations demonstrating that rotavirus elicits a normal Th1 cell response in IL-6− mice provides evidence that alternative mechanisms are available for Th1 cell differentiation in response to an enteric virus.

Of special relevance for control of rotavirus infection is the role that IL-6 plays in stimulating IgA in vitro (5, 10) and in vivo (37). However, in our study, the IgA response to rotavirus was normal in IL-6− mice. Rotavirus-specific IgA responses and total IgA levels in IL-6− and IL-6+ mice were essentially the same. These results were confirmed in two strains of IL-6− mice, BALB/c and mixed C57BL/6 × 129/O1a mice. Moreover, we showed that high levels of IgA were produced in PP and spleen cells from IL-6− mice restimulated with RRV Ag, confirming that IL-6 was nonessential for the recall IgA response as well. Consistent with this, in nonviral systems IL-6− mice had normal levels of IgA after mucosal administration of protein Ag plus cholera toxin as the adjuvant and following infection with the mucosal pathogen H. felis (6). Moreover, human tonsillar B cells did not require IL-6 for Ag (influenza virus)-specific antibody responses (12). Yet, in other experimental systems, Ag-specific IgA responses are clearly impaired in IL-6− mice (37, 39). For example, nasal immunization with attenuated vaccinia virus expressing the hemagglutinin glycoprotein of influenza virus resulted in impaired IgA and IgG responses (37).

These divergent results may reflect the existence of alternate pathways by which IL-6 regulates IgA. Thus, IL-6 directly stimulates IgA-positive B cells to secrete IgA (5) and may also indirectly enhance IgA by stimulation of complement components, which then potentiate antibody responses (24). It should be noted too that IL-6 is likely not required for these mechanisms to become operational in all experimental models. For example, IFN-γ can also stimulate components of the complement system (9, 30). Therefore, it remains possible that rotavirus-elicited IFN-γ may compensate for the loss of IL-6 and potentiate complement-dependent IgA. Stimulation of IgA may also depend on the nature of the Ag. In the case of rotavirus, it is possible that repetitive structural proteins (e.g., VP6) may directly cross-link and activate specific Igs on B cells, as appears to occur with certain other viruses (1). Moreover, the high Ag load and replicative capacity of viruses in general may alter the threshold requirement for certain costimulatory pathways (e.g., CD40 and CD28) and, as may be the case here, for APC-derived IL-6, enabling induction of strong specific immune responses in the absence of these factors (2).

Rotavirus-induced Th1 cells may provide efficient help for IgA in the absence of IL-6 and high levels of Th2 cells that produce IL-4. However, it should be noted that a previous study showed that SP cells isolated from mice orally inoculated with heterologous simian and murine rotavirus strains as neonates produced IFN-γ, IL-5, and IL-10 without IL-4 following restimulation with Ag in vitro (18). The increase in IFN-γ without significant amounts of IL-4 was in agreement with the present study. In the absence of endogenous IL-6-mediated functions, in vivo-primed CD4+ Th cells produced increased amounts of IL-4 following in vitro restimulation with rotavirus Ag. These results suggested that Th2-type memory cells were elevated in response to rotavirus infection in IL-6− mice. Despite this increase in Th2-type memory cells in vitro, however, rotavirus-specific Th1 cell responses and IgG1/IgG2a levels in serum samples were not elevated in IL-6− mice following primary rotavirus inoculation, further suggesting that Th cell responses were not drastically altered in vivo. Moreover, unfractionated PP cells failed to exhibit significantly increased IL-4 production following in vitro restimulation. The increase we observed in Th2-type memory cells in the absence of IL-6 is in agreement with a previous study showing an increased Th2-type response following infection with C. albicans in IL-6− mice (39). Moreover, T cells primed in IL-6− mice by immunization with dinitrophenol-albumin (DNP-OVA) produced slightly elevated Th2-type responses (IL-4 and IL-5) upon secondary in vitro restimulation (24). In the former case, Th1 cell responses were impaired (39), whereas in the latter case, Th1 cell responses remained strong (24). In contrast, IL-6 was shown to promote polarization of CD4+ Th2 cells by inducing the production of IL-4 from naive CD4+ T cells in concanavalin A-activated cell cultures (38). Thus, it appears that IL-6 can have differential effects on Th cell activation.

IL-6 stimulates cytotoxic NK and CD8+ T cells (3, 26). Indeed, a decreased CTL response was observed following inoculation of IL-6− mice with vaccinia virus (23). In the rotavirus model, IL-6− and IL-6+ mice appeared to be equally susceptible to rotavirus infection, based upon viral shedding in feces. However, a deficient CTL response remains possible because such an impairment may have only minor consequences on viral clearance and likely no observable effect on protection against secondary challenge. Thus, when B2 microglobulin knockout mice (deficient in major histocompatability complex class I-restricted CD8+ T cells) were infected with rotavirus, they cleared primary rotavirus infection with a delay of only 1 to 3 days compared to immunocompetent mice and were protected against secondary challenge (15). The development of rotavirus-specific CD4+ T cells and antibody may mask a deficient CTL response. A slight delay in rotavirus clearance in the absence of IL-6 would be suggestive of an impaired CTL response to rotavirus. To resolve this issue, it will be necessary to infect additional groups of IL-6− and IL-6+ mice with murine rotavirus and compare CTL responses. However, our results show that IL-6− mice clear primary murine rotavirus infection by day 6 to 8 and that peak levels of rotavirus in fecal samples are not elevated in comparison with IL-6+ mice.

We cannot exclude the possibility that lower initial doses of primary RRV followed by challenge with murine rotavirus may have delineated a more subtle difference between IL-6− and IL-6+ mice in protective efficacy. Moreover, although IL-6 was not required for IgA and Th1 cell development, we cannot discount the possibility that IL-6 plays a role in the development of IgA and Th1 cells in the immunocompetent host. To this end, we did not perform shedding curves for RRV because in normal mice RRV seldom replicates at levels detectable by our ELISA. However, rotavirus Ag loads were similar in IL-6− and IL-6+ mice infected with murine rotavirus strain ECw, and so disparate viral loads likely do not explain the strong IgA and Th1 cell responses we observed in IL-6− mice. Moreover, IgA responses were equally strong in IL-6− and IL-6+ mice infected with the murine rotavirus strain ECw. It should be noted that these results may not fully apply to neonates, whose immune responses may differ. In addition, neonates develop diarrhea following oral inoculation with murine rotavirus ECw, whereas the adults used in this study only shed virus subclinically.

In summary, the data presented here show that IL-6 is a dispensable cytokine for control of rotavirus infection and development of Th1 cells and IgA in adult mice. Knowledge of the regulation of mucosal IgA B cells and Th1 cells is of crucial importance for a better understanding of the behavior of these cells in the immune response to human rotavirus vaccines, as well as for optimal use of the Th cell arm of the immune system in the development of new antirotavirus vaccine modalities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AI 18958, DK 44240, AI 43197, AI 21632, and DK 38707 and by a VA merit review grant. Manuel Franco was supported by a Walter and Idun Berry fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachmann M F, Zinkernagel R M. Neutralizing anti-viral B cell responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:235–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmann M F, Zinkernagel R M, Oxenius A. Immune responses in the absence of costimulation: viruses know the trick. J Immunol. 1998;161:5791–5794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass H Z, Yamashita N, Clement L T. Heterogeneous mechanisms of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte generation. II. Differential effects of IL-6 on the helper cell-independent generation of CTL from CD8+ precursor subpopulations. J Immunol. 1993;151:2895–2903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beagley K W, Eldridge J H, Kiyono H, Everson M P, Koopman W J, Honjo T, McGhee J R. Recombinant murine IL-5 induces high rate IgA synthesis in cycling IgA-positive Peyer's patch B cells. J Immunol. 1988;141:2035–2042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beagley K W, Eldridge J H, Lee F, Kiyono H, Everson M P, Koopman W J, Hirano T, Kishimoto T, McGhee J R. Interleukins and IgA synthesis: human and murine IL-6 induce high rate IgA secretion in IgA-committed B cells. J Exp Med. 1989;169:2133–2148. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.6.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bromander A K, Ekman L, Kopf M, Nedrud J G, Lycke N Y. IL-6-deficient mice exhibit normal mucosal IgA responses to local immunization and Helicobacter felis infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:4290–4297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns J W, Krishnaney A A, Vo P T, Rouse R V, Anderson L J, Greenberg H B. Analyses of homologous rotavirus infection in the mouse model. Virology. 1995;207:143–153. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns J W, Siadat-Pajouh M, Krishnaney A A, Greenberg H B. Novel protective effect of rotavirus VP6-specific IgA monoclonal antibodies that lack neutralizing activity. Science. 1996;272:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celada A, Klemsz M J, Maki R A. Interferon-γ activates multiple pathways to regulate the expression of the genes for major histocompatibility class II I-Aβ, tumor necrosis factor and complement component C3 in mouse macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:1103–1109. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffman R L, Seymour B W, Lebman D A, Hiraki D D, Christiansen J A, Shrader B, Cherwinski H M, Savekoul H F J, Finkelman F D, Bond M W, Mosmann T R. The role of helper T cell products in mouse B cell differentiation and isotype regulation. Immunol Rev. 1988;102:5–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1988.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conner M E, Ramig R F. Viral enteric diseases. In: Nathanson N, et al., editors. Viral pathogenesis. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 713–733. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costelloe K E, Smith S H, Callard R E. Interleukin 6 is not required for antigen-specific antibody responses by human B cells. 1993. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:984–987. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalrymple S A, Lucian L A, Slattery R, McNeil T, Aud D M, Fuchino S, Lee F, Murray R. Interleukin-6-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Listeria monocytogenes infection: correlation with inefficient neutrophilia. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2262–2268. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2262-2268.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng N, Burns J W, Bracy L, Greenberg H B. Comparison of mucosal and systemic humoral immune responses and subsequent protection in mice orally inoculated with a homologous or a heterologous rotavirus. J Virol. 1994;68:7766–7773. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7766-7773.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franco M A, Greenberg H B. Role of B cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes in clearance of and immunity to rotavirus infection in mice. J Virol. 1995;69:7800–7806. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7800-7806.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franco M A, Tin C, Greenberg H B. CD8+ T cells can mediate almost complete short-term and partial long-term immunity to rotavirus in mice. J Virol. 1997;71:4165–4170. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4165-4170.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franco M A, Tin C, Rott L, VanCott J L, McGhee J R, Greenberg H B. Evidence for CD8+ T-cell immunity to murine rotavirus in the absence of perforin, Fas, and gamma interferon. J Virol. 1997;71:479–486. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.479-486.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fromantin C, Piroth L, Petitpas I, Pothier P, Kohli E. Oral delivery of homologous and heterologous strains of rotavirus to BALB/c mice induces the same profile of cytokine production by spleen cells. Virology. 1998;244:252–260. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert J M, Greenberg H B. Virus-like particle-induced fusion from without in tissue culture cells: role of outer-layer proteins VP4 and VP7. J Virol. 1997;71:4555–4563. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4555-4563.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groene W S, Shaw R D. Psoralen preparation of antigenically intact noninfectious rotavirus particles. J Virol Methods. 1992;38:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(92)90172-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoshino Y, Wyatt R G, Greenberg H B, Flores J, Kapikian A Z. Serotypic similarity and diversity of rotaviruses of mammalian and avian origin as studied by plaque-reduction neutralization. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:694–702. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.5.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishida S, Feng N, Tang B, Gilbert J M, Greenberg H B. Quantification of systemic and local immune responses to individual rotavirus proteins during rotavirus infection in mice. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1694–1700. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1694-1700.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopf M, Baumann H, Freer G, Freudenberg M, Lamers M, Kishimoto T, Zinkernagel R, Bluethmann H, Köhler G. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;368:339–342. doi: 10.1038/368339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kopf M, Herren S, Wiles M V, Pepys M B, Kosco-Vilbois M H. Interleukin 6 influences germinal center development and antibody production via a contribution of C3 complement component. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1895–1906. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladel C H, Blum C, Dreher A, Reifenburg K, Kopf M, Kaufmann S H. Lethal tuberculosis in IL-6 deficient mutant mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4843–4849. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4843-4849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luger T A, Krutmann J, Kirnbauer R, Urbanski A, Schwarz T, Klappacher G, Kock A, Micksche M, Malejczyk J, Schauer E, et al. IFN-beta 2/IL-6 augments the activity of human natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1989;143:1206–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNeal M M, Barone K S, Rae M N, Ward R L. Effector functions of antibody and CD8+ cells in resolution of rotavirus infection and protection against reinfection in mice. Virology. 1995;214:387–397. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McNeal M M, Broome R L, Ward R L. Active immunity against rotavirus infection in mice is correlated with viral replication and titers of serum rotavirus IgA following vaccination. Virology. 1994;204:642–650. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeal M M, Rae M N, Ward R L. Evidence that resolution of rotavirus infection in mice is due to both CD4 and CD8 cell-dependent activities. J Virol. 1997;71:8735–8742. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8735-8742.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell T J, Naughton M, Norsworthy P, Davies K A, Walport M J, Morley B J. IFNγ up-regulates expression of the complement components C3 and C4 by stabilization of mRNA. J Immunol. 1996;156:4429–4434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moskowitz N H, Brown D R, Reiner S L. Efficient immunity against Leishmania major in the absence of interleukin-6. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2448–2450. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2448-2450.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. Th1 and Th2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Offit P A, Clark H F. Protection against rotavirus-induced gastroenteritis in a murine model by passively acquired gastrointestinal but not circulating antibodies. J Virol. 1985;54:58–64. doi: 10.1128/jvi.54.1.58-64.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Offit P A, Clark H F, Blavat G, Greenberg H B. Reassortant rotaviruses containing structural proteins VP3 and VP7 from different parents induce antibodies protective against each parental serotype. J Virol. 1986;60:491–496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.491-496.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Offit P A, Dudzik K I. Rotavirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes passively protect against gastroenteritis in suckling mice. J Virol. 1990;64:6325–6328. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6325-6328.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oldham G, Bridger J C, Howard C J, Parsons K R. In vivo role of lymphocyte subpopulation in the control of virus excretion and mucosal antibody responses of cattle infected with rotavirus. J Virol. 1993;67:5012–5019. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.5012-5019.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramsay A J, Husband A J, Ramshaw I A, Boa S, Matthaei K I, Koehler G, Kopf M. The role of interleukin-6 in mucosal IgA antibody responses in vivo. Science. 1994;264:561–563. doi: 10.1126/science.8160012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rincón M, Anguita J, Nakamura T, Fikrig E, Flavell R A. Interleukin (IL)-6 directs the differentiation of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:461–469. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romani L, Mencacci A, Cenci E, Spaccapelo R, Toniatti C, Puccetti P, Bistoni F, Poli V. Impaired neutrophil response and CD4+ T helper cell 1 development in interleukin 6-deficient mice infected with Candida albicans. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1345–1355. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.VanCott J L, Staats H F, Pascual D W, Roberts M, Chatfield S N, Yamamoto M, Coste M, Carter P B, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Regulation of mucosal and systemic antibody responses by T helper cell subsets, macrophages, and derived cytokines following oral immunization with live recombinant Salmonella. J Immunol. 1996;156:1504–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Snick J. Interleukin 6: an overview. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;8:253–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward R L, Bernstein D I, Shukla R, Young E C, Sherwood J R, McNeal M M, Walker M C, Schiff G M. Effects of antibody to rotavirus on protection of adults challenged with a human rotavirus. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:79–88. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward R L, Greenberg H B, Estes M K. Viral gastroenteritis vaccines. In: Ogra P L, Mestecky J, Lamm M E, Strober W, McGhee J R, Bienenstock J, editors. Mucosal immunology. 2nd ed. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 282–305. [Google Scholar]