Abstract

The ability of polyomavirus large T antigen (LT) to promote cell cycling, to immortalize primary cells, and to block differentiation has been linked to its effects on tumor suppressors of the retinoblastoma susceptibility (Rb) gene family. Our previous studies have shown that LT requires an intact N-terminal DnaJ domain, in addition to an Rb binding site, for activation of simple E2F-containing promoters and stimulation of cell cycle progression. Here we show that some LT effects dependent on interaction with the Rb family are largely DnaJ independent. In differentiating C2C12 myoblasts, overexpression of LT caused apoptosis. Although this activity of LT completely depended on Rb binding, LTs with mutations in the J domain remained able to kill. Comparisons of Rb− and J− LTs revealed additional differences. Wild-type but not Rb− LT activated the cyclin A promoter under serum starvation conditions. Genetic analysis of the promoter linked the Rb requirement to an E2F site in the promoter. LTs with mutations in the J domain were still able to activate the promoter. Finally, J mutant LTs caused changes in phosphorylation of both pRb and p130. In the case of p130, Thr-986 was shown to be a site that is regulated by J mutant LT. Taken together, these observations reveal that LT regulation of Rb function can be separated into both DnaJ-dependent and DnaJ-independent pathways.

Polyomaviruses (Pys) have provided valuable models because the cellular pathways they use are generally important for cell function. The multifunctional large T antigens (LTs) represent one example. Their most obvious role is in DNA replication. Murine PyLT functions in initiation (21) of viral DNA synthesis, but it is also responsible for integration (15) and excision (4) of the viral genome. Biochemical studies on simian virus 40 (SV40) LT have provided important clues about basic cellular processes such as DNA replication (9, 78). LT's broad effects on the host cell led to the discovery of p53 (40, 46) and to considerable insight into the Rb tumor suppressor and E2F transcription factor families (47).

The effects of murine PyLT on the host cell can be viewed from a biological or a mechanistic perspective. LT induces cellular DNA synthesis (24, 66) and can immortalize primary cells (3, 58). LT can also block the differentiation of either myoblasts (51) or preadipocytes (14). It has the ability to promote apoptosis (20). Finally, LT is a transactivator of cellular genes (39, 54, 55).

Much of what LT does to cells depends upon its interactions with the Rb tumor suppressor family through an LXCXE motif starting at residue 141 (17, 32). Immortalization (22, 34, 41), induction of cell DNA synthesis (70), overcoming p53-induced cell cycle arrest (16), and prevention of differentiation (52) can all depend on Rb family binding. Transactivation of the thymidine kinase, polymerase α, PCNA, dihydrofolate reductase, and thymidylate synthase genes (54) as well as regulation of interferon-inducible gene expression (80) also requires an intact pRb/p107 binding site on LT and is mediated via the cellular transcription factor E2F.

A major shift in the perception of how LT regulates Rb family function began with the realization that the highly conserved N terminus (56) of all the Py T antigens looks like a DnaJ domain (12, 38). DnaJs bind to and stimulate the activity of DnaK proteins (44, 53). Subsequent biochemical studies (61, 72) and genetic domain swapping experiments (10, 37) confirmed the T antigen/J domain connection. J domains make multiple contributions to LT function. For SV40 they contribute, for example, to DNA replication (10). However, the most striking aspect of their function was that mutation of the J domain prevented its interaction with hsc70, a DnaK, thereby blocking LT functions related to Rb family member binding (27, 70, 72, 86). Since many of the effects of the Rb family are mediated through interactions with the E2F family, these results have been interpreted in terms of effects on protein complexes containing Rb and E2F family members.

The Rb family is, however, clearly multifunctional and can work independently of E2F. Studies of transgenic mice point to additional roles in development (76). A mutant pRb that does not bind to E2F or oncoproteins can still induce a flat-cell phenotype in Saos-2 cells and retains the ability to collaborate with MyoD in the differentiation of myoblasts (68). The minimal growth suppression domain of pRb contains at least three independent protein-binding functions (79). In addition to the A/B “pocket” domain and the E2F binding site, Rb has a C pocket domain required for interaction with MDM2 and c-Abl (82, 83) that is not found in p130 or p107. An N-terminally truncated pRb fails to rescue pRb−/− mice from embryonic lethality, indicating that the N-terminal sequences of pRb may also be important for pRb function (60).

The work presented here extends our analysis of the interaction between PyLT and the Rb family. Our previous work demonstrated that DnaJ was required for LT to affect Rb functions related to cell cycle progression or activation of promoters containing E2F sites. This work characterizes LT effects on the Rb family related to apoptosis and release of promoter repression that are largely independent of a functional DnaJ domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

NIH 3T3 cells originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection were provided by Bruce Cohen. Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% calf serum (Hyclone). C33A, a human cervical carcinoma cell line, was from Amy Yee and was maintained in DMEM containing 10% calf serum. Murine C2C12 myoblasts, an in vitro model for muscle differentiation (5, 84), were also a gift from Amy Yee and were grown in DMEM supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum. C42 cells, a pRb−/− myoblast cell line, were obtained from Ken Walsh and cultured the same way as the C2C12s.

Plasmids and mutagenesis.

pCMV-LT (62) and pCMV-Rb−-LT, which contains two point mutations in the L-X-C-X-E motif of PyLT (32), have been described previously. The J domain mutants H42Q and P43S were also described earlier (70). Both mutants were used in each assay with similar results. The pCMV-neoBAM vector lacking an LT insert was used as a control (CON) plasmid. Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) β-galactosidase (β-Gal) (2, 18) and EMSV MyoD were also provided by Amy Yee. CMV-HA-Rb (31), pcDNA1-HA-p130 (77), and CMV-p107-HA (88) were obtained from Jim DeCaprio. CMV-RbT821A was made using primers 5′TCAGAAGGTCTGCCAGCACCAACAAAAATGACTC3′ and 5′GAGTCATTTTTGTTGGTGCTGGCAGACCTTCTGA3′. pcDNA1-HA-p130 T986A was made using primers 5′AGCAGTGCTCCTCCCGCACCTACTCGCCTCAC3′ and 5′GTGAGGCGAGTAGGTGCGGGAGGAGCACTGCT3′. The −89/+11 cyclin A-luc construct (73) was a gift from Antonio Giordano. The −37/−33 cyclin A E2F substitution mutant was made using primers 5′ATTGGTCCATTTCAATAGAGCTTGGATACTTGAACTGCAAG3′ and 5′CTTGCAGTTCAAGTATCCAAGCTCTATTGAAATGGACCAAT3′. Mutations were introduced using standard PCR techniques based on PfuI polymerase (Stratagene). All the mutants were verified by sequencing (65).

Protein analysis.

After washing and collection in PBS+ (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] with 1 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 mM MgCl), cells were extracted in T extraction buffer (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 1% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40) for 20 min at 4°C. Cleared extracts were incubated with antibody and protein A or protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia) for 1 h. After washing in PBS+, immunoprecipitates were boiled for 2 min in dissociation buffer (62.5 mM Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], 5% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 25% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.0075% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, 50 μl of β-mercaptoethanol per ml) and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). After electrophoresis, samples were blotted onto nitrocellulose and analyzed by immunoblotting (75). Antibodies used in blotting included mouse monoclonal antibody PN116 (32) or anti-LT polyclonal rabbit serum to detect LT and HA11 or 12CA5 to detect hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Rb, p130, or p107.

For hydroxylamine digestion, p130 was immunoprecipitated and labeled in vitro. Afterwards, samples of p130 were separated on 7.5% cylindrical gels. Then the gel was pushed out of the cylinder and soaked with 7.5% acetic acid–5% methanol (vol/vol) for 1 h at room temperature. The gel was then treated with 0.2 M K2CO3, pH 9.0, for an additional hour at room temperature and with hydroxylamine solution (4 M hydroxylamine in 0.4 M K2CO3 [pH 9.0]) for another 3 h at 45°C. Afterwards, the gel was washed with 100 ml of 0.125 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8)–1% SDS–0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol–0.03% bromophenol blue for 1.5 h with one change of wash solution. The gel was placed on top of a 13% acrylamide gel, sealed with chemical agarose (1% agarose, 0.125 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% SDS, 1% β-mercaptoethanol), and electrophoresed overnight. Finally the gel was dried and used to expose Kodak XAR5 film with an intensifying screen.

Transient transfections and reporter assays.

Transient transfections using BES (N,N-bis[2-hydroxyethyl]-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid)-buffered saline were done with both C33A cells and NIH 3T3 cells (13). For luciferase assays, 1 μg of reporter together with 3 μg of different DNA constructs were added to a 60-mm-diameter plate of cells. For some experiments, at 24 h after transfection, cells were starved for another 24 h in DMEM with 0.2% calf serum. At 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested by freeze-thawing, and 5 μl from a 100-μl extract was used for measurement of luciferase activity.

In the case of C2C12 cells and C42s, HEPES-buffered saline solutions were used for transfection (25, 64). HEPES-buffered saline was obtained from 5′→3′. For a 60-mm-diameter plate of cells, a total of 15 μg of DNA was added. Five hours after the addition of precipitate, the cells were rinsed twice with PBS and incubated in PBS containing 20% glycerol for 2 to 3 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and incubated with fresh medium.

Apoptosis.

For LT-induced apoptosis, 90 to 100% confluent 30-mm-diameter dishes of murine C2C12 myoblasts were cotransfected in duplicate with different pCMV-LT constructs, pCMV-MyoD, and RSV β-Gal reporter plasmid. One set of transfections was fixed at 24 h posttransfection. For this, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. The other half of the experiments were incubated with differentiation medium (DMEM with 2% horse serum) for an additional 24 h before fixation. To identify β-Gal enzyme activity in the fixed cells, dishes were stained with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactosidase) solution [0.5% X-Gal, 3 mM K3Fe(CN)6, K4Fe(CN)6 · 3H2O, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.01% Triton X-100] in PBS at 37°C for 12 to 24 h. Apoptosis was calculated as the decrease in the number of normal, nonapoptotic blue cells between dishes stained at 24 h after transfection and those allowed to differentiate for another 24 h.

Apoptosis was assessed using terminal transferase in the form of the Apoptag Kit (Oncor). C2C12 cells grown on coverslips were transfected with RSV β-Gal, MyoD, and wild-type LT in DMEM containing 20% fetal calf serum. At 24 h after transfection, cells were supplemented with DMEM containing 2% horse serum for another 24 h. Coverslips were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and assayed as described by the manufacturer (Oncor).

RESULTS

PyLT induced apoptosis in differentiating C2C12 cells in a transient assay.

C2C12 cells are myoblasts that undergo terminal differentiation upon serum withdrawal. PyLT interferes with in vitro terminal differentiation of myoblasts (52). Comparisons of established cell lines showed that this activity of LT requires pRb binding (52). Recently, it was also shown that myoblast cell lines expressing PyLT underwent apoptosis upon serum withdrawal (20). Apoptosis induced by PyLT was further enhanced by factors that induce differentiation (20). To explore this activity of PyLT, a collection of LT mutants and effector proteins were tested in the differentiating C2C12 system. Transient assays were used so that a large number of mutant LTs and effector proteins could be tested. Full differentiation of C2C12 cells normally occurs within a week after serum withdrawal. For a transient assay, full differentiation should occur within 48 to 72 h. To shorten the time required for C2C12 differentiation, MyoD, which has been shown to induce myoblast differentiation (reviewed by Weintraub [81]), was used in our transient assays. RSV β-Gal was cotransfected together with different constructs as a transfection marker. Staining of terminal differentiation markers, such as myosin heavy chain (MHC), revealed that in the presence of MyoD, over 90% of the transfected cells were differentiated within 72 h (not shown). Similar to the cell line result reported earlier, expression of PyLT in this transient assay blocked C2C12 differentiation in over 95% of the cells; a difference from isolated cell lines was that in these transient assays, even LT mutant in Rb binding blocked MHC expression (not shown).

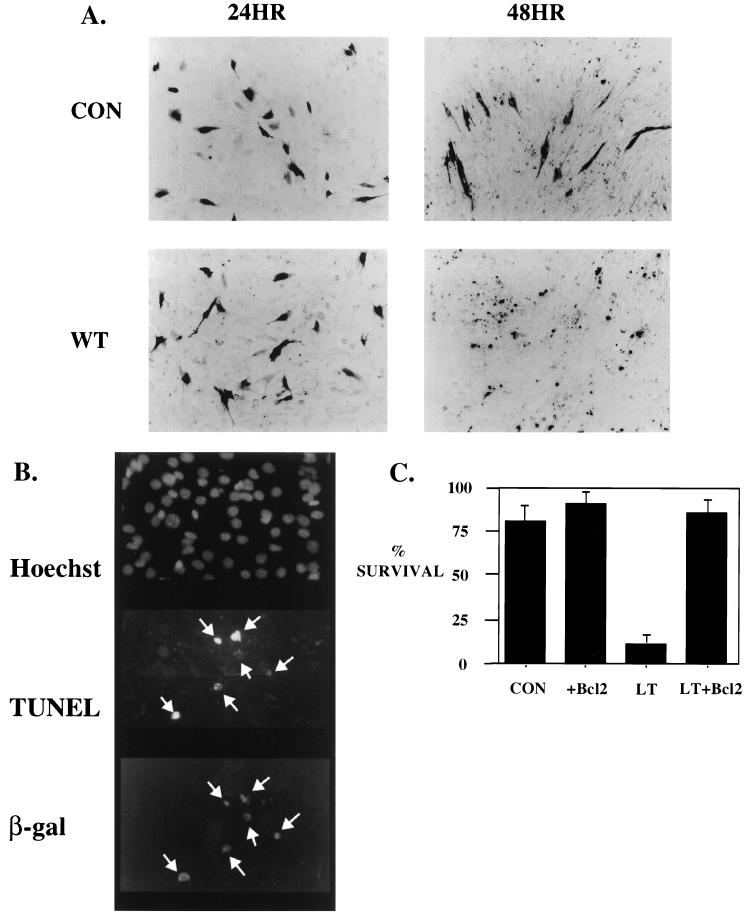

Apoptosis was next assayed in this transient C2C12 system. Cells were cotransfected with wild-type LT together with MyoD and RSV β-Gal. At 24 h after transfection, half of the experiment was stained for β-Gal activity, while the other half was incubated in DMEM with 2% horse serum for an additional 24 h before staining. At 24 h, the number of β-Gal-positive cells in LT-transfected plates was comparable to that in the control plate (Fig. 1). With an additional 24-h incubation in low serum, most of the β-Gal-positive cells disappeared from the LT-transfected plates, whereas approximately 80% of transfected cells remained on the control plates (Fig. 1A). The loss of β-Gal-positive cells in LT-transfected plates is a result of apoptosis. Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assays (Fig. 1B) were positive in LT-expressing cells. In addition, cotransfected antiapoptotic factor Bcl2 completely blocked PyLT-induced cell death (Fig. 1C). Both results support the conclusion that LT induced apoptosis in this transient system.

FIG. 1.

LT-induced apoptosis in differentiating C2C12 cells. (A) Expression of wild-type LT induced loss of C2C12 cells. Two sets of identical plates were transfected with 2.5 μg of RSV β-Gal, 2.5 μg of MyoD, and 5 μg of either a control vector (CON) or wild-type (WT) LT. One set of plates were fixed and stained for β-Gal activity 24 h after transfection. A second set of plates were incubated in DMEM with 2% horse serum for an additional 24 h before staining for β-Gal activity. (B) PyLT-expressing cells were positive for Apop-tag staining. C2C12s were transfected with 5 μg of wild-type LT, 2.5 μg of MyoD, and 2.5 μg of RSV β-Gal. At 24 h after transfection, cells were starved in DMEM with 2% horse serum for another 14 h before being fixed and stained with tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC) anti-β-Gal antibody. The cells were then incubated with terminal digoxigenin transferase to have its free 3′OH overhang conjugated with digoxigenin. Lastly, these cells were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) antidigoxigenin and Hoechst dye. Fluorescence was observed on a Nikon microscope with appropriate filters. Arrows indicate stained transfected cells. (C) LT-induced apoptosis can be rescued by Bcl2 expression. Two identical sets of C2C12s were transfected with 2 μg of RSV β-Gal, 2 μg of MyoD, and 5 μg of control vector (CON) or wild-type LT in the presence or absence of 1 μg of Bcl2 and treated as described for panel A. The β-Gal-positive cells in all the plates were counted, and data are expressed as [(number of β-Gal-positive cells at 48 h)/(no. of β-Gal-positive cells at 24 h)] × 100 to get percent survival values.

pRb is one of the downstream targets for PyLT-induced apoptosis.

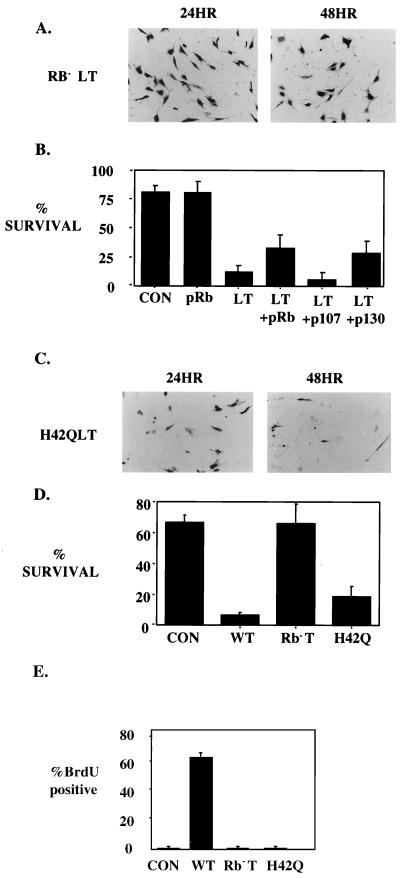

Since it is already known that pRb family binding is part of LT's effect on myoblasts (52), a pRb binding mutant of LT was assayed for the ability to induce apoptosis using the β-Gal staining assay. As shown in Fig. 2A and D, cells transfected with Rb− LT survived as well as the control cells when incubated in low serum for 24 h. In some cases, better survival was observed in Rb− LT-transfected plates than in controls (not shown). Two kinds of experiments were performed to test the role of Rb family members. To try to determine whether pRb was specifically involved, RB−/− myoblasts (C42 cells) were examined. C42s treated with a control vector showed significant cell death when treated in the same manner as the C2C12s (not shown). This is consistent with the suggestion that pRb plays an important role in protection from apoptosis during differentiation. When wild-type LT was introduced into C42 cells, the percentage of cell death upon serum starvation was comparable to that of controls (not shown). In other words, LT had no additional proapoptotic effect of its own. This result indicates that LT kills by interaction with pRb. A different, opposite kind of experiment involved overexpressing Rb family members to try to protect against LT-mediated killing. As shown in Fig. 2B, Rb and p130 but not p107 could reduce the amount of killing caused by LT.

FIG. 2.

Rb binding but not J function is necessary for LT to induce apoptosis. (A) Rb− LT did not induce apoptosis in C2C12s. Two sets of identical plates were transfected with 2.5 μg of RSV β-Gal, 2.5 μg of MyoD, and 5 μg of Rb− LT. Plates were fixed and stained as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. (B) Overexpression of pRb partially protects C2C12s from LT-induced apoptosis. C2C12s were cotransfected with 2.5 μg of RSV β-Gal, 2.5 μg of MyoD, and either 2.5 μg of control vector (CON), 2.5 μg of wild-type LT, or 2.5 μg of Rb− LT in the presence or absence of 2.5 μg of HA-Rb, HA-130, and HA-107. Cells were stained and counted as described above. (C) H42Q-induced apoptosis in C2C12s. Two sets of identical plates were transfected with 2.5 μg of RSV β-Gal, 2.5 μg of MyoD, and 5 μg of H42Q LT. Plates were fixed and stained as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. (D) Wild-type and H42Q but not Rb− LT can induce apoptosis in C2C12s. C2C12s were transfected with 2.5 μg of RSV β-Gal, 2.5 μg of MyoD, 5 μg of control vector (CON), wild-type LT, Rb− LT, or H42Q LT. Cells were stained for β-Gal and counted as described above. (E) H42Q was incapable of promoting cellular DNA replication in C2C12 cells. C2C12 cells were transfected with the indicated DNAs. Transfected cells incubated in 2% horse serum for approximately 36 h were labeled with 100 μM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) for an additional 14 h. After staining for LT with rabbit polyclonal antibody-FITC anti-rabbit Ig and BrdU with the monoclonal antibody BU-1-TRITC anti-mouse Ig (Amersham), nuclear fluorescence was scored with a Zeiss microscope. Values represent counts of more than 300 T-positive cells in each case.

A functional J domain is not required for PyLT to induce apoptosis.

Previous work showed that LT required both an intact pRb binding site and a functional J domain to activate E2F (70). However, a critical question is whether a requirement for J function is universal or if it is limited to certain pRb functions such as E2F regulation. J mutants were therefore tested to determine if J domain function is necessary for LT's ability to induce apoptosis.

As shown in Fig. 2C, cells transfected with H42Q had an intermediate phenotype. After 24 h in low-serum medium, the number of positive surviving cells in the H42Q-transfected plates as scored by β-Gal staining was much reduced. However, the extent of cell death was not as severe as that of wild-type LT-transfected plates. Figure 2D is a summary of the LT constructs used in the β-Gal staining assay. It is clear that H42Q did not have wild-type activity in inducing cell death. About 20% of H42Q-transfected cells survived, compared to less than 5% cell survival of wild-type-LT-transfected cells. Nevertheless, H42Q was still very effective in inducing apoptosis (over 70% of the cells survived in the control sample). The killing induced by H42Q cannot be the result of leakiness, because a deletion mutant lacking the J domain (Δ2-79) also completely induced cell death.

Apoptosis is often associated with inappropriate growth signals. Although we have shown previously that H42Q was defective in promoting S phase in NIH 3T3s, the differences between wild-type and J− LT could be imagined to result from signals for cell cycle progression in C2C12s. The ability of H42Q to promote cell cycle progression was compared to that of wild-type LT in C2C12s (Fig. 2E). Since LT induced apoptosis in these cells under low-serum conditions, the number of LT-positive cells that survived after serum withdrawal was low (10%). It was nonetheless feasible to score over 300 LT-positive cells for DNA replication. The results, shown in Fig. 2E, demonstrate that J− mutants were as defective in stimulating DNA synthesis in C2C12s as in 3T3s. This result indicates that apoptosis induced by LT is not simply a result of inducing S phase under inappropriate conditions.

After serum withdrawal, LT activation of the cyclin A promoter, like induction of apoptosis, requires an intact Rb binding site but not J function.

In considering possible J-independent targets for LT, the cyclin A promoter was an attractive candidate for several reasons. First, it has been reported that LT affects cyclin A levels in myoblasts (20). Second, cell cycle regulation of the human cyclin A gene promoter is mediated by a variant E2F site at −37 to −33 (67). While a mutation at that site abolished the increased promoter activity resulting from serum stimulation, it also gave rise to a higher basal activity, suggesting a role for the E2F site in restricting activity of the promoter. In addition, repression of the promoter by p130 and histone deacetylase HDAC1 was observed (73). These findings raised the possibility that LT's effect on such a promoter might differ from that observed in a simple E2F model promoter.

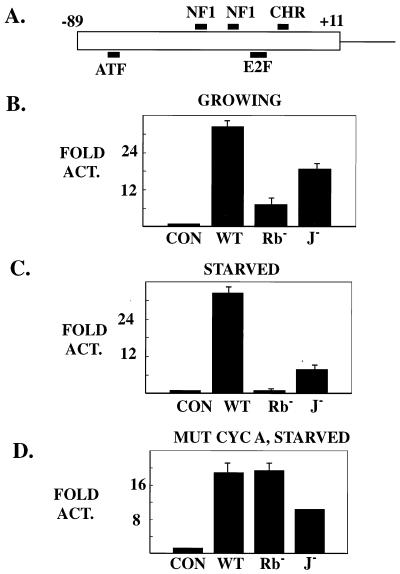

The −89/+11 fragment of cyclin promoter A (Fig. 3A), which contains the serum-responsive E2F site and which was the smallest construct displaying the cell cycle regulation profile of the full-length promoter (29, 67), was used in these studies. Even in growing cells it was obvious that LT regulates the cyclin A promoter differently than the simple E2F-containing promoters described previously. Mutant LT that is defective in Rb binding still retained substantial ability to activate the cyclin A promoter (8-fold) (Fig. 3B) compared to a value of 36-fold for the wild type. A J mutant (H42Q) of LT was also active in the cyclin A-luciferase assay, inducing the promoter 21-fold. Therefore, in growing cells, LT's effect on the cyclin A promoter, which has an E2F site, is only partially dependent on Rb binding and J domain function. By comparison, previous work on simple E2F-containing promoters showed that LT activation is almost completely Rb and J dependent (70).

FIG. 3.

Regulation of cyclin A promoter by PyLT. (A) Diagram of the cyclin A promoter. The −89 to +11 sequence of the cyclin A promoter was fused to the luciferase reporter (67). One ATF site, two NF1 sites, one CHR site, and an E2F site (−37/−33) have been noted in this promoter. The −37/−33 site that was mutated is involved in serum responsiveness. (B) LT activation of the cyclin A promoter in growing NIH 3T3 cells. Cells incubated in 10% calf serum were transfected with 3 μg of the indicated plasmids together with 1 μg of the cyclin A-luc reporter. The luciferase activity was measured at 48 h after transfection. All values are fold activation compared to the control samples. (C) Effects of LT and its mutants on the cyclin A promoter in serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells. NIH 3T3 cells cultured with 10% calf serum were transfected with 3 μg of either a control vector (CON), wild-type LT, Rb− LT, or H42Q LT together with 1 μg of reporter DNA. At 24 h after transfection, cells were washed and incubated in DMEM with 0.2% calf serum for another 24 h. (D) LT regulation of the −37/−33 E2F mutant cyclin A promoter in serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells. This experiment was done similarly to that shown in Fig. 4B except the mutant cyclin A (MUT CYC A) promoter was used instead of the wild-type cyclin A promoter.

Even more striking results were obtained when transfected cells were placed in low serum in the same manner as in the apoptosis assay. J− LT (H42Q) and Rb− LT behaved very differently towards the cyclin A promoter (Fig. 3C). NIH 3T3 cells were transfected in 10% calf serum, changed to 0.2% calf serum 24 h after transfection, and harvested at 48 h. In 19 experiments wild-type LT always caused strong expression from the cyclin A promoter. While activation of as much as 100-fold has been observed, an average value of 32-fold was seen. This activation was strikingly dependent on its pRb binding, as the Rb− LT had almost no activity. The J domain mutant of LT, although not as active as wild-type LT, induced a 7.9-fold activation. Therefore, in serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells, Rb binding but not J function was necessary for LT to activate the cyclin A promoter fully.

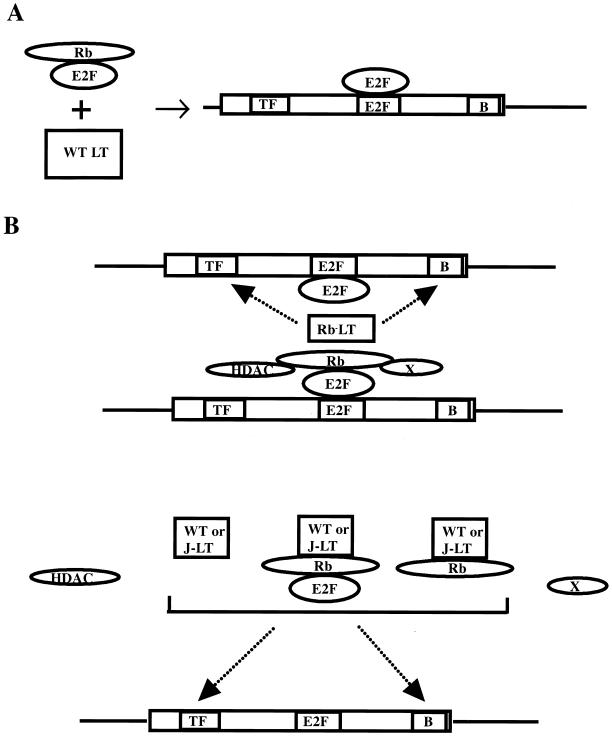

The requirement for Rb binding for LT activity in starved cells prompted us to examine the involvement of the −37/−33 E2F site responsible for serum responsiveness (67) in LT activation of the cyclin A promoter. Mutation of the E2F site had a small effect on activation (18-fold) of the cyclin A promoter by wild-type LT in starved cells (Fig. 3D). Therefore, there must be targets other than the E2F site for LT activation of the cyclin A promoter. These could be one of the upstream sites (ATF or NF1). Alternatively, it could be the basal transcription factor machinery. SV40 LT is clearly capable of affecting TATA binding elements (59). More importantly, the genetics of LT activation were very different. The J mutant acted towards the mutant promoter as it did with the wild-type promoter, that is, somewhat less than wild-type LT (11-fold). In contrast to the wild-type promoter, Rb− LT activated the mutant cyclin A promoter similarly to the wild type (Fig. 3D). In other words, the E2F site in the cyclin A promoter conferred Rb dependence for LT activation in serum-starved cells but was not needed for promoter activity in the presence of LT. This means that the principal function of this E2F site is repression. Rb binding is necessary for LT to release that repression so it can activate at other sites. The ability of Rb− and J− LTs to transactivate the E2F mutant promoter suggests that LT has transactivation functions that do not require these particular LT functions.

J mutant LTs induced hyperphosphorylation of Rb and p130.

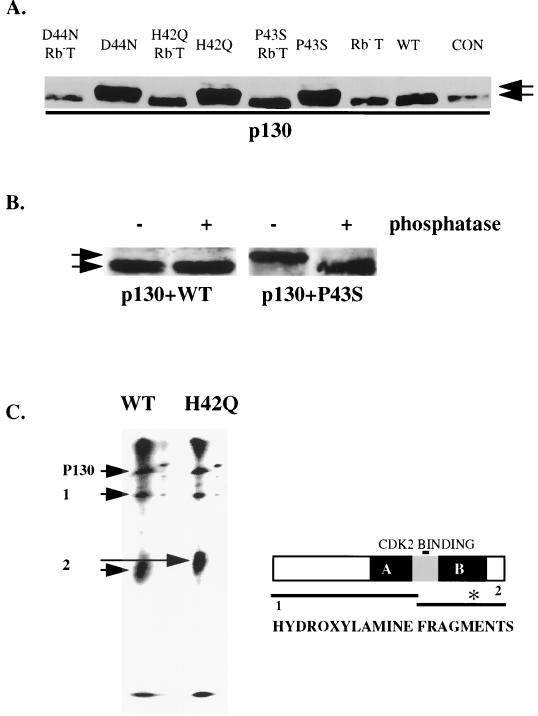

The data on the cyclin A promoter indicate that the effect of LT is restricted by the E2F site unless it binds Rb. Further, because J mutants are active in serum-withdrawn cells, binding of Rb family members by LT is sufficient for significant activity. The Rb effect is mediated by the E2F site in the cyclin A promoter. This raised the question of what effect the J mutant has on Rb family members that could be acting through the E2F site. Previous work showed a mobility shift in p130 when J− PyLT was present compared to when wild-type LT was present (70). A similar difference for p130 was also observed by the DeCaprio group for SV40 LT (74).

A decrease in the mobility of HA-p130 compared to either p130 alone or cotransfected with wild-type LT was observed in growing C33As (Fig. 4A). Mutation in the H, P, or D residue in the J domain enabled the mutant to supershift HA-p130. This mobility shift of p130 was dependent on pRb binding of LT, because LT mutants that are defective in both pRb binding and J function were unable to change the mobility of HA-tagged p130. The same supershift was observed in serum withdrawal protocols such as those used for the cyclin A promoter and apoptosis experiments (e.g., see Fig. 6). It also did not matter which cells (3T3, Rb− C33As, or wild-type RB C2C12s) were used.

FIG. 4.

J mutant LT modifies the phosphorylation of p130. (A) J− LT-induced p130 mobility shift in C33A cells. C33A cells were transfected with 6 μg of HA-p130 and 3 μg of the indicated different LT constructs. At 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested and extracted. Cell extracts were run on SDS–7.5% PAGE and blotted for HA-p130 with 12CA5. Arrowheads indicate p130 with different mobilities. (B) Phosphatase treatment of HA-p130 reverses the mobility shift induced by J− LT. C33A cells were transfected with either wild-type (WT) LT or P43S together with HA-p130. At 48 h after transfection, cells were extracted and extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA-antibody 12CA5 bound to SAS beads. The immunoprecipitates were then separated into two sets. One set was treated with 20 U of λ phosphatase per sample for 1 h at 37°C, and the other set was incubated under the same conditions without phosphatase. Finally, these immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS–7.5% PAGE and blotted for HA-p130 with 12CA5. Arrows indicate differently phosphorylated states of p130. (C) Hydroxylamine treatment of HA-p130. The left panel shows hydroxylamine mapping of p130, and the right panel displays a diagram of p130 with the two large potential hydroxylamine fragments shown and the CDK2 binding site marked. The asterisk in the right panel represents Thr-986. C33A cells were transfected with either wild-type (WT) LT or H42Q together with HA-p130. At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 12CA5 bound on SAS beads. The immunoprecipitates were then in vitro labeled with 32P as described in Materials and Methods. The labeled precipitates were then subjected to electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, the area corresponding to the p130 position was cut and treated with hydroxylamine and then subjected to a second round of electrophoresis. Arrow 1 indicates the N-terminal fragment of p130. Arrow 2 indicates the C-terminal fragment.

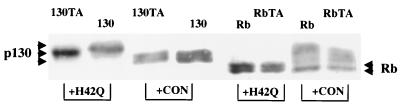

FIG. 6.

Threonine 986 on p130 is a phosphorylation site modified by J− LT. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with either wild-type p130 (130), a mutant p130 that has a T986A mutation (130TA), wild-type Rb (Rb), or mutant RbT821A (RbTA) together with either H42Q LT or a control vector (CON). At 24 h after transfection, cells were fluid changed with 0.2% calf serum medium. Cells were harvested at 48 h, and cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted with anti-HA antibody HA-11. Arrowheads indicate different mobilities of p130, Rb, and their mutants.

The mobility change in HA-p130 was due to phosphorylation of p130. After cotransfection of H42Q and HA-p130, immunoprecipitated HA-130 was treated with lambda phosphatase and run on SDS-PAGE. HA-p130 was then detected by 12CA5 on a Western blot. As shown in Fig. 4B, the slow-moving p130 shifted to the control level upon phosphatase treatment. Although the mobility of p130 was changed by cotransfection of LT J mutants, 32P labeling data indicated that there was only minimal change in the overall phosphorylation (not shown). Therefore, it seems that the mobility shift seen in the J− LT complexes results from specific phosphorylation of p130 rather than a global change in the p130 phosphorylation state.

To localize this phosphorylation on the p130 molecule, hydroxylamine mapping was carried out. To obtain labeled material, immunoprecipitates were labeled with [32P]ATP in vitro. This labeling simply marks the molecule, since the mobility shift observed by Western blot is retained after this treatment (not shown). After the protein was subjected to SDS–7.5% PAGE, the portion of the gel containing p130 was treated with hydroxylamine. The fragments were then resolved on a second SDS–13% acrylamide gel. p130 has two hydroxylamine sites (NG), dividing p130 into three fragments: residues 1 to 739, 739 to 754, and 754 to 1139. The second piece is too small to be observed on the gel, and therefore, only two labeled fragments were seen (Fig. 4C, left panel). In the presence of H42Q, only the carboxy-terminal fragment showed a mobility change compared to the corresponding fragment in the presence of wild-type LT (Fig. 4C, right panel).

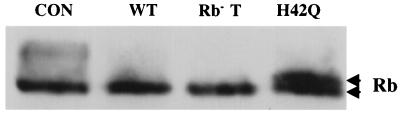

In addition to p130, we also examined the phosphorylation patterns of Rb and p107 in the presence of J domain mutant LT in 3T3s using the 24-h low-serum treatment. The results were more complicated. Control cells still showed slower-migrating phosphorylated forms of Rb. Cells coexpressing wild-type LT or Rb− LT showed predominantly a rapidly migrating Rb band. Compared to this band, the Rb band seen when J− LT was coexpressed was hyperphosphorylated and showed a doublet (Fig. 5). There was no obvious change in p107 mobility in the presence of J mutant LT in any cell tested (not shown).

FIG. 5.

Modification of pRb by J− LT. J− LT induced a mobility shift in Rb in serum-starved NIH 3T3 cells. NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with 4 μg of HA-Rb and 4 μg of the indicated different LT constructs. At 24 h after transfection, cells were fluid changed into 0.2% calf serum medium. Cells were harvested at 48 h, and cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted with anti-HA antibody HA-11. Arrowheads indicate Rb at different mobilities.

Mutation of threonine 986 on p130 changes its response to J− mutant LT.

In considering where phosphorylation of 130 must occur when J− LT is expressed, we were struck by the sequence homology between Thr-986 of p130 and Thr-821 of Rb. Thr-821 of pRb is known to be phosphorylated in vivo (45). The sequence surrounding this site, P-T821-P-T-X (where X represents a basic residue), bears homology to both cdc2 and JNK/p38 phosphorylation sites, Ser/Thr-Pro (11). This site is conserved in both human and murine pRb and p130, but not p107. A mutant p130 was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis in which Thr-986 was converted to Ala. This mutation caused the protein to migrate slightly slower on SDS-PAGE. The striking result was that coexpression of J− LT caused little shift of this p130 mutant (Fig. 6) compared to the wild type. This result indicated that Thr-986 in p130 is one of the phosphorylation sites responsible for the observed supershift of p130 in the presence of J− LT. In the case of Rb, it is unclear if Thr-821 is also targeted by J− LT, since there was no obvious change in RbT821A in the presence of J− LT compared to wild-type Rb (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

PyLT induces apoptosis in differentiating C2C12 cells in a manner that is completely dependent on Rb family binding. Although cell death induced by LT was completely dependent on pRb binding, cells transfected with J domain mutants underwent apoptosis. This function of J− mutants is strikingly different than that seen in assays such as DNA synthesis and simple E2F-containing promoter activation. J− LTs are inactive in those assays. Distinctions in the ways LTs reach the Rb family, seen here for PyLT, has recently been noted for SV40 LT in other kinds of assays (23a).

It is not surprising that interactions between LT and Rb family members affect cell survival. Loss of Rb in Rb−/− fibroblasts results in apoptosis when cells are placed under conditions that would promote growth arrest (1, 30, 48). A role in protecting myoblasts from apoptosis has also been observed in transgenic mouse experiments (85). In some mouse strains, p130 null phenotypes have also been associated with apoptosis (43).

The phenotype of LT J domain mutants was intermediate; killing was less efficient than that of wild-type LT. The difference suggests that two Rb-dependent pathways lead to apoptosis: one pathway requires J function, while the other is J function independent. Activation of E2F family members may be involved in the J-dependent pathway. Overexpression of E2F-1 in serum-starved cells can cause apoptosis (57, 69). In our hands, C2C12s were killed by transfection of E2F1 (not shown). Efforts to confirm the role of E2F1 directly by inhibition of the pathway were not successful. Transfection of dominant negative forms of E2F-1, DP1, or both did not prevent LT-induced apoptosis. Since E2F1 has been reported to kill via p53 (57), dominant negative p53 was also tried. Even though reporter assays showed that dominant negative p53 could repress wild-type p53 activity, expression of the dominant negative p53 in C2C12s failed to prevent apoptosis. In any of these experiments, the existence of a second pathway might obscure effects from the dominant negatives. Since heat shock proteins are also known to have antiapoptotic effects (23, 36), it is also possible that the J-dependent killing includes sequestering cellular heat shock proteins by LT via the J domain.

How can the apoptosis caused by J− LT be understood? There are at least two possible models to explain J independence. The first is more passive. In such a model, pRb, which is known to have antiapoptotic function, might bind a cellular target to prevent apoptosis. LT binding to Rb may simply prevent the interaction necessary for its antiapoptotic function. This would be different, for example, from promoter activation at E2F sites, which is thought to require release of active E2F from Rb/E2F complexes. There are a number of potential candidates for antiapoptotic targets. HDAC1, a general transcriptional repressor that binds to Rb and has the potential to induce apoptosis through a variety of pathways (6–8, 19, 49, 50), is one attractive possibility. Riz1 is a proapoptotic protein that binds Rb and could potentially be regulated in such a manner (28). Rb binding to MDM2 can affect its antiapoptotic activity (35). Finally, another candidate is HBP-1, a specific transcriptional regulator that becomes apoptotic when its LXCXE and IXCXE motifs are mutated to prevent Rb family binding (A. Yee, unpublished data). In models of sequestration, phosphorylation obviously could affect Rb association with partners. A second model, perhaps less likely, envisions a more active role for Rb in which a modified Rb form itself contributes directly to apoptosis. In the case of J− LT, this might be a phosphorylated form.

What do we know in molecular terms about the differences between J− and Rb− LTs? There are at least two things that J− LT can do that Rb− LT does not: modify the phosphorylation state of Rb and p130 and transactivate promoters such as cyclin A under serum-starved conditions. These two functions are not necessarily independent.

We have demonstrated that J− LT affects phosphorylation of the Rb family members. In the case of p130, J− LT clearly modifies its C terminus; genetic analysis suggests that T986 is one significant site. It is possible that this phosphorylation is novel for the J domain mutants, since the mobility shift is not observed with the wild type. However, we favor the notion that the wild type induces the same phosphorylation. For the wild type, the regulation of Rb family members proceeds with subsequent loss of the phosphorylated species, whereas the J mutants are stopped at the step requiring the J domain. Phosphorylation of Rb family members is well known to be involved in regulation of their function. In cell cycle progression, phosphorylation is involved in the inactivation of Rb regulation of E2F; J− LT-induced phosphorylation is clearly insufficient to affect Rb regulation of E2F, since the J mutants of LT are not active in E2F transactivation. However, phosphorylations may serve to regulate Rb functions besides E2F regulation. For example, phosphorylation of Rb family members has been associated with apoptosis (33), although it is not clear that it is causal. Attempts to block cell killing with the phosphorylation mutants of p130 or Rb described here have not been successful so far. Therefore, the connection between the phosphorylation of Rb family members induced by J− LT and the ability of J− LT to influence their function remains an open question.

Regulation of the cyclin A promoter is another function that differentiates J− from Rb− LT. Under conditions of low serum, LT transactivation is Rb dependent but only somewhat J dependent, just like apoptosis. Interestingly, Fimia and colleagues (20) have shown that LT-expressing myoblasts express higher levels of cyclin A than controls. Since transfection of vectors expressing cyclin A did not kill, cyclin A itself does not appear to be responsible for cell death. However, it would be reasonable to think that other promoters might be regulated the same way.

The cyclin A data suggest a simple explanation for LT promoter activation that may be Rb dependent but largely J independent (Fig. 7). In contrast to simple E2F promoters where LT causes activation by generating active E2F from Rb/E2F complexes (Fig. 7A), on the cyclin A promoter LT affects the ability of Rb family members to act in repression (Fig. 7B). The basic considerations are these. Mutation of the E2F site had very little effect on the activity of the promoter. In other words, LT was not activating through this site. However, in a wild-type promoter with the −37/−33 E2F site intact, LT needed an Rb binding function to transactivate. LT transactivation of a cyclin A promoter lacking the −37/−33 E2F site is largely Rb independent because there is no repression to relieve. Repression at an E2F site occurs when it is occupied by an Rb family-E2F family complex. Such a complex could contain additional components, such as HDAC1. It is well known that E2F sites can function as repressors. For example, in myoblasts, such a site is known to repress activity under differentiating conditions (71). One way that this can occur is via interaction with histone deacetylase and basal transcription factors such as TFIID (63). The complex prevents LT from activating through other sites on the promoter. When LT binds Rb family members, it prevents formation of the restricting complex, perhaps by preventing entry of something like HDAC1. This would make LT activity highly dependent on Rb binding in serum-starved cells. In growing cells, where E2F may occupy the site without an Rb family members, then Rb binding would be less important, and Rb− LT would have activity. These are the results observed. Is the cyclin A promoter effect completely separate from the observed effect on phosphorylation? It need not be; phosphorylation could be responsible for disrupting complexes between Rb family members and Rb binding proteins. For cyclin A, p130 has been reported to inhibit the wild-type promoter (73). It is certainly possible that phosphorylated p130 or pRb behaves differently from unphosphorylated p130. Such differences could have a direct effect on activity through the E2F sites or an indirect effect by changing access to the rest of the promoter.

FIG. 7.

Model for LT regulation of the cyclin A promoter. (A) LT activates simple E2F-containing promoters by releasing E2F-1 from the E2F/Rb complex. (B) LT activates a more complicated promoter, such as a cyclin A promoter, in a manner not dependent on the E2F site. This activation (indicated by the arrows) could be through either basal (B) or transcription factor (ATF or NF1) sites. When the E2F site is occupied by an E2F complex containing Rb and other elements (HDAC-1 or some other Rb-binding protein X), Rb− LT lacks the ability to transactivate. When LT can bind Rb, even if it is J−, the complex (Rb/E2F/X or HDAC-1) does not assemble and LT can transactivate regardless of whether the site is occupied.

Finally, the data also underscore additional Rb-independent mechanisms for LT transactivation. The notion that LT might have Rb-independent functions in transactivation is not novel (34, 42); in SV40 LT, several different targets of transactivation have been demonstrated (26, 87). In addition to targeting transcription factors, LT may also target the basal transcriptional machinery, since this appears to happen for SV40 LT (59). Since the E2F mutant promoter is fully activated by LT, the non-Rb-dependent transactivation accounts for the major activity of LT. LT activates promoters like cyclin A through sites other than E2F.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant CA34722.

We thank Jennifer A. Kean for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almasan A, Yin Y, Kelly R E, Lee E Y, Bradley A, Li W, Bertino J, Wahl G M. Deficiency of retinoblastoma protein leads to inappropriate S-phase entry, activation of E2F-responsive genes and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5436–5440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonucci T K, Wen P, Rutter W J. Eukaryotic promoters drive gene expression in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17656–17659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asselin C, Bastin M. Sequences from polyomavirus and simian virus 40 large T genes capable of immortalizing primary rat embryo fibroblasts. J Virol. 1985;56:958–968. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.3.958-968.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basilico C, Zouzias D, Della Valle G, Gattoni S, Colantuoni V, Fenton R, Dailey L. Integration and excision of polyoma virus genomes. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1980;44:611–620. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1980.044.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blau H M, Pavlath G K, Hardeman E C, Chiu C P, Silberstein L, Webster S G, Miller S C, Webster C. Plasticity of the differentiated state. Science. 1985;230:758–766. doi: 10.1126/science.2414846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brehm A, Kouzarides T. Retinoblastoma protein meets chromatin. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:142–145. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brehm A, Miska E A, McCance D J, Reid J L, Bannister A J, Kouzarides T. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature. 1998;391:597–601. doi: 10.1038/35404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brehm A, Nielsen S J, Miska E A, McCance D J, Reid J L, Bannister A J, Kouzarides T. The E7 oncoprotein associates with Mi2 and histone deacetylase activity to promote cell growth. EMBO J. 1999;18:2449–2458. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullock P. The initiation of simian virus 40 DNA replication in vitro. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:503–568. doi: 10.3109/10409239709082001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell K S, Mullane K P, Aksoy I A, Stubdal H, Zalvide J, Pipas J M, Silver P A, Roberts T M, Schaffhausen B S, DeCaprio J A. DnaJ/hsp40 chaperone domain of SV40 large T antigen promotes efficient viral DNA replication. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1098–1110. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.9.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chauhan D, Hideshima T, Treon S, Teoh G, Raje N, Yoshihimito S, Tai Y T, Li W, Fan J, DeCaprio J, Anderson K C. Functional interaction between retinoblastoma protein and stress-activated protein kinase in multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1192–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheetham M E, Brion J P. Human homologues of the bacterial heat-shock protein DnaJ are preferentially expressed in neurons. Biochem J. 1992;284:469–476. doi: 10.1042/bj2840469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C A, Okayama H. Calcium phosphate-mediated gene transfer: a highly efficient transfection system for stably transforming cells with plasmid DNA. BioTechniques. 1988;6:632–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherington V, Morgan B, Spiegelman M, Roberts T M. Recombinant retroviruses that transduce individual polyoma tumor antigens: effects on growth and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4307–4311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Della Valle G, Fenton R G, Basilico C. Polyoma large T antigen regulates the integration of viral DNA sequences into the genome of transformed cells. Cell. 1981;23:347–355. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doherty J, Freund R. Polyomavirus large T antigen overcomes p53 dependent growth arrest. Oncogene. 1997;14:1923–1931. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyson N, Bernards R, Friend S H, Gooding L R, Hassell J A, Major E O, Pipas J M, Vandyke T, Harlow E. Large T antigens of many polyomaviruses are able to form complexes with the retinoblastoma protein. J Virol. 1990;64:1353–1356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1353-1356.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edlund T, Walker M D, Barr P J, Rutter W J. Cell-specific expression of the rat insulin gene: evidence for role of two distinct 5′ flanking elements. Science. 1985;230:912–916. doi: 10.1126/science.3904002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira R, Magnaghi-Jaulin L, Robin P, Harel-Bellan A, Trouche D. The three members of the pocket proteins family share the ability to repress E2F activity through recruitment of a histone deacetylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10493–10498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fimia G M, Gottifredi V, Bellei B, Ricciardi M, Tafuri A, Amati P, Maione R. The activity of differentiation factors induces apoptosis in polyomavirus large T-expressing myoblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1449–1463. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Francke B, Eckhart W. Polyoma gene function required for viral DNA synthesis. Virology. 1973;55:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(73)81014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freund R, Bronson R T, Benjamin T L. Separation of immortalization from tumor induction with polyoma large T mutants that fail to bind the retinoblastoma gene product. Oncogene. 1992;7:1979–1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabai V L, Meriin A B, Yaglom J A, Volloch V Z, Sherman M Y. Role of Hsp70 in regulation of stress-kinase JNK: implications in apoptosis and aging. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Gjoerup O, Chao H, DeCaprio J A, Roberts T M. pRB-dependent, J domain-independent function of simian virus 40 large T antigen in override of p53 growth suppression. J Virol. 2000;74:864–874. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.864-874.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gjørup O, Rose P, Holman P, Bockus B, Schaffhausen B. Protein domains connect cell cycle stimulation directly to initiation of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12125–12129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham F L, van der Eb A J. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruda M C, Zabolotny J M, Xiao J H, Davidson I, Alwine J C. Transcriptional activation by simian virus 40 large T antigen: interactions with multiple components of the transcription complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:961–969. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris K F, Christensen J B, Radany E H, Imperiale M J. Novel mechanisms of E2F induction by BK virus large-T antigen: requirement of both the pRb-binding and the J domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1746–1756. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He L, Yu J X, Liu L, Buyse I M, Wang M S, Yang Q C, Nakagawara A, Brodeur G M, Shi Y E, Huang S. RIZ1, but not the alternative RIZ2 product of the same gene, is underexpressed in breast cancer, and forced RIZ1 expression causes G2-M cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4238–4244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henglein B, Chenivesse X, Wang J, Eick D, Brechot C. Structure and cell cycle-regulated transcription of the human cyclin A gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5490–5494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrera R E, Sah V P, Williams B O, Makela T P, Weinberg R A, Jacks T. Altered cell cycle kinetics, gene expression, and G1 restriction point regulation in Rb-deficient fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2402–2407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinds P W, Mittnacht S, Dulic V, Arnold A, Reed S I, Weinberg R A. Regulation of retinoblastoma protein functions by ectopic expression of cyclins. Cell. 1992;70:993–1006. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90249-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holman P, Gjoerup O, Davin T, Schaffhausen B. Characterization of an immortalizing N-terminal domain of polyomavirus large T antigen. J Virol. 1994;68:668–673. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.668-673.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Honma N, Hosono Y, Kishimoto T, Hisanaga S. Phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein at apoptotic cell death in rat neuroblastoma B50 cells. Neurosci Lett. 1997;235:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00709-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howes S, Bockus B, Schaffhausen B. Genetic analysis of polyomavirus large T nuclear localization: nuclear localization is required for productive association with pRb family members. J Virol. 1996;70:3581–3588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3581-3588.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh J K, Chan F S, O'Connor D J, Mittnacht S, Zhong S, Lu X. RB regulates the stability and the apoptotic function of p53 via MDM2. Mol Cell. 1999;3:181–193. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaattela M, Wissing D, Kokholm K, Kallunki Y, Egeblad M. Hsp70 exerts its anti-apoptotic function downstream of caspase-3-like proteases. EMBO J. 1998;17:6124–6134. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelley W L, Georgopoulos C. The T/t common exon of simian virus 40, JC, and BK polyomavirus T antigens can functionally replace the J-domain of the Escherichia coli DnaJ molecular chaperone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3679–3684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelley W L, Landry S J. Chaperone power in a virus? Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:277–278. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kingston R E, Cowie A, Morimoto R I, Gwinn K A. Binding of polyomavirus large T antigen to the human hsp70 promoter is not required for trans activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3180–3190. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.9.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lane D P, Crawford L. T antigen is bound to a host of protein in SV40-transformed cells. Nature. 1979;278:261–263. doi: 10.1038/278261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larose A, Dyson N, Sullivan M, Harlow E, Bastin M. Polyomavirus large T mutants affected in retinoblastoma protein binding are defective in immortalization. J Virol. 1991;65:2308–2313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2308-2313.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larose A, St-Onge L, Bastin M. Mutations in polyomavirus large T affecting immortalization of primary rat embryo fibroblasts. Virology. 1990;176:98–105. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90234-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LeCouter J E, Kablar B, Whyte P F, Ying C, Rudnicki M A. Strain-dependent embryonic lethality in mice lacking the retinoblastoma-related p130 gene. Development. 1998;125:4669–4679. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liberek K, Marszalek J, Ang D, Georgopoulos C, Zylicz M. Escherichia coli DnaJ and GrpE heat shock proteins jointly stimulate ATPase activity of DnaK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2874–2878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin B T, Wang J Y. Cell cycle regulation of retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Ciba Found Symp. 1992;170:227–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linzer D I H, Levine A J. Characterization of a 54K Dalton cellular SV40 tumor antigen present in SV40-transformed cells and uninfected embryonal carcinoma cells. Cell. 1979;17:43–52. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livingston D. Functional analysis of the retinoblastoma gene product and of RB-SV40 T antigen complexes. Cancer Surv. 1992;12:153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lukas J, Bartkova J, Rohde M, Strauss M, Bartek J. Cyclin D1 is dispensable for G1 control in retinoblastoma gene-deficient cells independently of cdk4 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2600–2611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo R X, Postigo A A, Dean D C. Rb interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Cell. 1998;92:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80940-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Magnaghi-Jaulin L, Groisman R, Naguibneva I, Robin P, Lorain S, Le Villain J P, Troalen F, Trouche D, Harel-Bellan A. Retinoblastoma protein represses transcription by recruiting a histone deacetylase. Nature. 1998;391:601–605. doi: 10.1038/35410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maione R, Fimia G M, Amati P. Inhibition of in vitro myogenic differentiation by a polyomavirus early function. Oncogene. 1992;7:85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maione R, Fimia G M, Holman P, Schaffhausen B, Amati P. Retinoblastoma antioncogene is involved in the inhibition of myogenesis by polyomavirus large T antigen. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCarty J S, Buchberger A, Reinstein J, Bukau B. The role of ATP in the functional cycle of the DnaK chaperone system. J Mol Biol. 1995;249:126–137. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mudrak I, Ogris E, Rotheneder H, Wintersberger E. Coordinated trans activation of DNA synthesis and precursor-producing enzymes by polyomavirus large T antigen through interaction with the retinoblastoma protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1886–1892. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogris E, Rotheneder H, Mudrak I, Pichler A, Wintersberger E. A binding site for transcription factor E2F is a target for trans activation of murine thymidine kinase by polyomavirus large T antigen and plays an important role in growth regulation of the gene. J Virol. 1993;67:1765–1771. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1765-1771.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pipas J M. Common and unique features of T antigens encoded by the polyomavirus group. J Virol. 1992;66:3979–3985. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.3979-3985.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qin X, Livingston D, Kaelin W, Adams P. Deregulated transcription factor E2F-1 expression leads to S-phase entry and p53-mediated apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10918–10922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rassoulzadegan M, Naghasfar Z, Cowie A, Carr A, Grisoni M, Kamen R, Cuzin F. Expression of the large T protein of polyoma virus promotes the establishment in culture of “normal” rodent fibroblast cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:4354–4358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rice P, Cole C. Efficient transcriptional activation of many simple modular promoters by simian virus 40 large T antigen. J Virol. 1993;67:6689–6697. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6689-6697.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riely D J, Liu C Y, Lee W H. Mutations of N-terminal regions render the retinoblastoma protein insufficient for functions in development and tumor suppression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7342–7352. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riley M I, Yoo W, Mda N Y, Folk W R. Tiny T antigen: an autonomous polyomavirus T antigen amino-terminal domain. J Virol. 1997;71:6068–6074. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6068-6074.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rose P, Schaffhausen B. Zinc-binding and protein-protein interaction mediated by the polyomavirus large T zinc finger. J Virol. 1995;69:2842–2849. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2842-2849.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ross J F, Liu X, Dynlacht B D. Mechanism of transcriptional repression of E2F by the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein. Mol Cell. 1999;3:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schlegel R, Benjamin T L. Cellular alterations dependent upon the polyoma virus hr-t function: separation of mitogenic from transforming capacities. Cell. 1978;14:587–599. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schulze A, Zerfass K, Spitkovsky D, Middendorp S, Berges J, Helin K, Jansen-Durr P, Henglein B. Cell cycle regulation of the cyclin A gene promoter is mediated by a variant E2F site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11264–11268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sellers W, Novitch B, Miyake S, Heith A, Otterson G, Kaye F, Lassar A, Kaelin W. Stable binding to E2F is not required for the retinoblastoma protein to activate transcription, promote differentiation, and suppress tumor cell growth. Genes Dev. 1998;12:95–106. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shan B, Lee W H. Deregulated expression of E2F-1 induces S-phase entry and leads to apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8166–8173. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sheng Q, Denis D, Ratnofsky M, Roberts T M, DeCaprio J A, Schaffhausen B. The DnaJ domain of polyomavirus large T antigen is required to regulate Rb family tumor suppressor function. J Virol. 1997;71:9410–9416. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9410-9416.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shin E K, Shin A, Paulding C, Schaffhausen B, Yee A S. Multiple changes in E2F function and regulation occur upon muscle differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2252–2262. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Srinivasan A, McClellan A J, Vartikar J, Marks I, Cantalupo P, Li Y, Whyte P, Rundell K, Brodsky J L, Pipas J M. The amino-terminal transforming region of simian virus 40 large T and small t antigens functions as a J domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4761–4773. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stiegler P, De Luca A, Bagella L, Giordano A. The COOH-terminal region of pRb2/p130 binds to histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), enhancing transcriptional repression of the E2F-dependent cyclin A promoter. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5049–5052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stubdal H, Zalvide J, DeCaprio J A. Simian virus 40 large T antigen alters the phosphorylation state of the Rb-related proteins p130 and p107. J Virol. 1996;70:2781–2788. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2781-2788.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsai K Y, Hu Y, Macleod K F, Crowley D, Yamasaki L, Jacks T. Mutation of E2F-1 suppresses apoptosis and inappropriate S phase entry and extends survival of Rb-deficient mouse embryos. Mol Cell. 1998;2:293–304. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vairo G, Livingston D M, Ginsberg D. Functional interaction between E2F-4 and p130: evidence for distinct mechanisms underlying growth suppression by different retinoblastoma protein family members. Genes Dev. 1995;9:869–881. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Waga S, Stillman B. Anatomy of a DNA replication fork revealed by reconstitution of SV40 DNA replication in vitro. Nature. 1994;369:207–212. doi: 10.1038/369207a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J Y J. Retinoblastoma protein in growth suppression and death. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weihua X, Ramanujam S, Lindner D, Kudaravalli R, Freund R, Kalvakolanu D. The polyoma virus T antigen interferes with interferon-inducible gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1085–1090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weintraub H. The MyoD family and myogenesis: redundancy, networks, and thresholds. Cell. 1993;75:1241–1244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Welch P J, Wang J Y J. A C-terminal protein binding domain in RB regulates the nuclear c-AB1 tyrosine kinase in the cell cycle. Cell. 1993;75:775–790. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90497-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xiao Z X, Chen J D, Levine A, Modjtahedl N, Xing J, Sellars W R, Livingston D M. Interaction between the retinoblastoma protein and the oncoprotein MDM2. Nature. 1995;375:694–697. doi: 10.1038/375694a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yaffe D, Saxel O. Serial passaging and differentiation of myogenic cells isolated from dystrophic mouse muscle. Nature. 1977;270:725–727. doi: 10.1038/270725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zacksenhaus E, Jiang Z, Chung D, Marth J D, Phillips R A, Gallie B L. pRB controls proliferation, differentiation, and death of skeletal muscle cells and other lineages during embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3051–3064. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zalvide J, Stubdal H, DeCaprio J A. The J domain of simian virus 40 large T antigen is required to functionally inactivate RB family proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1408–1415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhu J Y, Rice P W, Chamberlain M, Cole C N. Mapping the transcriptional transactivation function of simian virus 40 large T antigen. J Virol. 1991;65:2778–2790. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2778-2790.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhu L, van den Heuvel S, Helin K, Fattaey A, Ewen M, Livingston D, Dyson N, Harlow E. Inhibition of cell proliferation by p107, a relative of the retinoblastoma protein. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1111–1125. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]