Abstract

Germ cell tumors encompass a broad spectrum of neoplasms arising from germ cell lineage, demonstrating varying histological profiles and clinical presentations. These tumors encompass a range of benign and malignant entities. While global trends provide insights into their prevalence, specific regional variations, such as those within North-Western India, remain less explored. This study seeks to bridge this knowledge gap by examining the prevalence and characteristics of germ cell tumors within a tertiary cancer hospital. In this retrospective analysis, all cases of germ cell tumors diagnosed over a 3-year period in the specified tertiary cancer hospital were included. Cases with incomplete records or inadequate pathological data were excluded. Data encompassing histological subtypes, patient age distribution, clinical presentations, and histopathological features were collected and analyzed. The study comprised 145 cases of germ cell tumors. Teratomas were the most prevalent subtype, with mature teratomas accounting for the majority. The highest incidence occurred within the 21–30-year age group with a mean age of 24.77 years. Abdominal mass (56%) and abdominal pain (34%) were the prominent clinical presentations. Benign cases constituted the majority 85.5%. Solid tumors (p < 0.00001) and tumors more than 10 cm (p .029028) were found to have a high propensity to be malignant, which was proven to be statistically significant. This study comprehensively explains germ cell tumors’ prevalence, clinical features, and histopathological subtypes in a tertiary cancer hospital in North-Western India. The predominance of teratomas, particularly mature ones, aligns with global trends. The age distribution and clinical presentations reflect common patterns. The diverse histopathological appearances underscore the heterogeneous nature of germ cell tumors. This study offers valuable insights for clinical management and further regional research.

Keywords: Germ cell tumor, Teratomas, Choriocarcinoma, Dysgerminoma, Yolk sac tumor, Ovarian Tumor

Introduction

Germ cell tumors represent a complex and diverse group of neoplasms histopathologically that arise from the primordial germ cells [1], which normally give rise to gametes. These tumors exhibit a wide range of histological subtypes and clinical behaviors, making them a fascinating and challenging area of study within oncology. The varied nature of germ cell tumors is reflected in their ability to differentiate into tissues from all three germ layers, resulting in an array of tumor types that encompass teratomas, dysgerminomas, yolk sac tumors, choriocarcinomas, and embryonal carcinomas, among others.

Germ cell tumors account for a significant proportion of ovarian tumors and can occur in various age groups, ranging from infancy to late adulthood. Their clinical presentations vary, from asymptomatic to manifestations such as abdominal pain, mass, and hormonal irregularities [2]. The diverse manifestations and histological characteristics of germ cell tumors have spurred ongoing research into their etiology, pathogenesis, and optimal management strategies.

While global studies have provided insights into the prevalence and characteristics of germ cell tumors, regional variations in the incidence and clinical features exist, necessitating localized investigations. This study focuses on assessing germ cell tumors in a tertiary cancer hospital in North-Western India over a 3-year period. The aim is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the prevalence, clinical presentations, and histopathological attributes of germ cell tumors within this specific geographical context.

By exploring aspects of germ cell tumors within North-Western India, this study contributes to the broader understanding of these neoplasms and their impact on affected individuals. Such knowledge holds implications for understanding regional variations of germ cell tumors and refining clinical management, early diagnosis, and targeted therapeutic approaches, ultimately improving patient treatment outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This retrospective study was conducted to assess germ cell tumors within a tertiary cancer hospital in North-Western India. The study spanned a 3-year period, from 2020 to 2023, allowing for an encompassing evaluation of cases diagnosed within this timeframe.

Inclusion Criteria

All cases diagnosed with germ cell tumors during the specified 3-year period were included in the study. All patients who underwent staging laparotomy in our institute were included. A comprehensive evaluation of medical records, including clinical, radiological, and pathological data, were necessary for inclusion.

Exclusion Criteria

Cases with incomplete medical records, lacking crucial pathological information, or those not meeting the criteria for germ cell tumors were excluded from the study. Emergency surgery done in another department for torsion etc. leading to final diagnosis of germ cell tumor was excluded as staging would be difficult.

Histopathological Analysis

Histopathological specimens were reviewed by experienced pathologists to confirm the diagnosis and classify tumor subtypes. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification system [19] was used to categorize germ cell tumor subtypes based on distinct histological features.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations, were used to summarize the collected data. Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square test, while continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test.

Results

A total of 145 cases of germ cell tumors were identified and included in this retrospective study conducted over a 3-year period. The distribution of germ cell tumor histopathological frequency (Fig. 1) was as follows: mature teratomas (118 cases), immature teratomas (8 cases), teratoma with chondrosarcoma component (1 case), dysgerminoma (10 cases), yolk sac tumor (4 cases), embryonal carcinoma (1 case), choriocarcinoma (2 cases), and mixed germ cell tumor (1 case).

Fig. 1.

Germ cell tumor histopathology frequency

The age distribution (Fig. 2) revealed a predominant occurrence in the 21–30-year age group, accounting for 74 cases (51.0% of total cases). Cases were also distributed across other age groups: 1–10 years (2 cases), 11–20 years (31 cases), 31–40 years (23 cases), 41–50 years (13 cases), and > 50 years (2 cases).

Fig. 2.

Age distribution

Clinical manifestations varied among the cases (Fig. 3). The most common presenting symptom was abdominal mass, reported in 56% of cases (81 cases). Abdominal pain was the second most frequent symptom, noted in 34% of cases (49 cases). Menstrual irregularities were observed in 5% of cases (7 cases), while hirsutism was present in 1% of cases (2 cases). Additionally, 4% of cases (6 cases) exhibited bowel and bladder disturbances.

Fig. 3.

Symptom frequency

The distribution between benign and malignant cases indicated a predominance of benign cases, constituting 85.5% of the total (124 cases), while malignant cases accounted for 14.5% (21 cases).

Histopathological analysis revealed varying tumor appearances (Fig. 4). Cystic tumors were observed in 84 cases (57.9%), solid tumors in 18 cases (12.4%), and solid cystic tumors in 43 cases (29.7%).

Fig. 4.

Gross appearances of tumor

Of these 2 out of 84 cystic tumors were malignant, 10 out of 18 solid tumors and 9 out 43 of solid cystic were found to be malignant, and chi-square analysis was done resulting in a statistical result of 35.8936. The p-value is < 0.00001. The result is significant at p < 0.05 suggesting that solid tumors have more propensity to be malignant.

Final histopathological size distribution of ovarian mass revealed that most were more than 10 cm in size constituting 59% of all cases rest were less than 10 cm. It was also found that 4 out of 59 cases (6.78%) of < 10 cm were malignant; also, 17 out of 86 cases (19.76%) of > 10 cm were malignant. The chi-square analyses were done which showed a statistic value of 4.7659. The p-value is 0.029028. The result is significant at p < 0.05, which interprets tumor more than 10 cm there is a chance of being malignant.

The comprehensive data collected from this study provide insights into the prevalence, age distribution, clinical manifestations, histological subtypes, and tumor appearances of germ cell tumors within the specified region and timeframe. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the nature of germ cell tumors in this context, guiding improved diagnostic and management approaches for affected individuals.

Discussion

The 3-year retrospective study on germ cell tumors conducted at a tertiary care hospital in North-Western India provides valuable insights into the epidemiology and characteristics of these tumors in the region. The study’s findings shed light on the prevalence, types, and age distribution of germ cell tumors, allowing for a deeper understanding of the disease and its implications for patient care.

It is noteworthy that few studies have delved [22] into the intricacies of ovarian tumors within this geographic region. The demographic and regional variations in disease patterns often necessitate localized investigations to comprehend the nuances that might differ from broader or global trends.

Germ cell tumors represent a diverse and heterogeneous group of tumors, originating from various developmental stages of germ cells [1]. This variability gives rise to a spectrum of tumor types, with some comprised of undifferentiated cells like dysgerminoma and embryonal carcinoma, while others exhibit differentiation towards embryonic or extraembryonic structures such as teratoma, choriocarcinoma, and yolk sac tumor [3]. These tumors collectively account for approximately 20–30% of all ovarian tumors, and malignant germ cell forms 2–3% of all ovarian malignancies [4].

Initial workup with radiological imaging, such as transvaginal ultrasound, CT pelvis, and pelvic MRI, plays a crucial role in evaluating ovarian masses. These modalities assist in determining the characteristics of the tumor, including size, location, cystic or solid nature, and the presence of any concerning features like septations or calcifications. Dermoid cysts typically appear as complex ovarian masses on ultrasound due to their heterogeneous nature. They often contain various components such as solid tissue, cystic spaces, and echogenic elements. USG can reveal specific echo patterns within dermoid cysts, showcasing echogenic areas corresponding to fat, hair, teeth, or calcifications. These structures appear as mobile, shadowing, or hyperechoic foci within the cystic component. A characteristic finding in dermoid cysts is the Rokitansky nodule [21], a focal area of high echogenicity within the cyst, representing densely aggregated sebaceous material, hair, or calcification. The cyst walls of dermoid cysts might exhibit variable thickness and can contain thin septations, contributing to the heterogeneous appearance on ultrasound. While helpful, imaging findings may not definitively distinguish between different types of ovarian masses, necessitating further investigation like tumor markers.

Tumor markers play a pivotal role in the diagnosis, management, and monitoring of various cancers, including germ cell tumors of the ovary. Tumor markers we monitored before surgery were CA125, CEA, CA19-9, AFP, LDH, and β-hCG. These markers provide valuable insights into disease progression, therapeutic response, and prognosis. In our study of 145 cases of germ cell tumors, the utilization of specific tumor markers contributed to the comprehensive understanding of these complex neoplasms. β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) associated with gestational trophoblastic disease is also expressed in certain germ cell tumors, including choriocarcinoma and some mixed germ cell tumors [15]. Elevated β-hCG levels serve as a diagnostic clue and are used to monitor treatment response and disease recurrence. In our study, the presence of choriocarcinoma and mixed germ cell tumors prompted the measurement of β-hCG levels, aiding in accurate diagnosis and post-treatment monitoring. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is a well-known tumor marker for germ cell tumors, especially yolk sac tumors. Elevated AFP levels aid in distinguishing yolk sac tumors from other ovarian malignancies.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) while not specific to germ cell tumors can serve as an indicator of tumor burden and response to therapy. Elevated LDH levels often correlate with advanced disease stages [16]. Monitoring LDH levels in our study helped assess disease progression and therapeutic efficacy.

Inhibin, a marker produced by granulosa cells, is often elevated in granulosa cell tumors, a subset of ovarian germ cell tumors. The presence of inhibin in our study prompted further evaluation and histopathological confirmation of granulosa cell tumors [17].

The application of tumor markers, such as β-hCG, AFP, and LDH, in our study of germ cell tumors of the ovary showcased their utility in accurate diagnosis, monitoring treatment response, and prognostication. While not standalone diagnostic tools, tumor markers contribute to a comprehensive understanding of these neoplasms and aid in delivering effective patient care.

In all cases, utilized staging laparotomy in the assessment and staging of ovarian germ cell tumors serves as a crucial component in determining the extent of disease spread, guiding treatment decisions, and predicting prognosis. In our study, where all patients underwent staging laparotomy, the distribution of stages reveals significant insights into the disease presentation and management. Of the total cases evaluated through staging laparotomy, 134 (92.41%) cases were classified as stage 1A, 5 (3.44%) cases were identified as stage 1C, and 6 (4.13%) cases were categorized as stage 2.

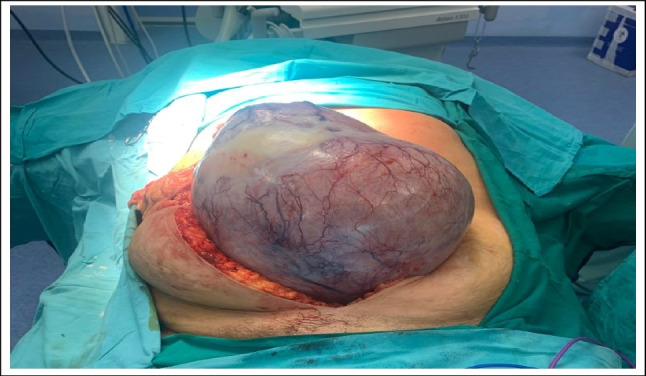

Among these, mature cystic teratoma emerged as the most prevalent subtype, accounting for a substantial portion. Mature cystic teratomas, characterized by their unilocular cystic appearance filled with hair and cheesy material, displayed predominant microscopic features related to skin and its appendages [5]. While a majority of mature cystic teratomas were detected in individuals below the age of 50, a noteworthy aspect is the occurrence of dermoid cysts in postmenopausal women (Fig. 5), implying a potentially slow-growing nature of these tumors that might have originated years earlier.

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative picture of 50-year-old lady with large dermoid cyst

Microscopic examination of dermoid germ cell tumors [3] reveals a fascinating blend of differentiated tissues derived from various germ cell layers (Figs. 5, 6). These tumors showcase a diverse assortment of cell types and structures, often resembling a miniature representation of the human body in a confined space. Under the microscope, dermoid tumors commonly exhibit skin appendages such as hair follicles, sweat glands, and sebaceous glands. Additionally, fragments of cartilage, smooth muscle, adipose tissue, and neural elements may be observed, reflecting their pluripotent origin from germ cells. The presence of these components underscores the tumor’s unique ability to differentiate into various tissue types.

Fig. 6.

Histopathological image of mature teratoma

Occasionally, dermoid tumors might display more specialized structures like mature teeth, thyroid tissue, and even neural tissue with well-defined neural elements [6]. The coexistence of these distinct tissues within the same tumor mass is a hallmark of dermoid germ cell tumors and adds to their enigmatic nature. In contrast to the leisurely growth of dermoid cysts, primitive germ cell tumors are typically encountered in girls and women of reproductive age. These primitive tumors are distinctive from their mature counterparts and carry their own set of characteristics and implications. Malignant germ cell tumors, on the other hand, represent a subset with critical clinical significance. Immature teratomas, constituting 3% of teratomas and 1% of all ovarian cancers, possess a mixed composition of mature and immature elements, often including immature cartilage, mesenchyme, and primitive neuroepithelium.

Malignant transformations in teratomas further underscore the complexity of germ cell tumors [7]. Dermoid cysts, which usually carry benign implications, can rarely harbor malignant elements, primarily squamous cell carcinomas. The incidence of such transformations is relatively low, but when they do occur, they are more commonly observed in postmenopausal women. A case of chondrosarcoma arising in a mature teratoma was observed in our study, making up a small fraction of the germ cell tumors.

Dysgerminoma, the most common malignant germ cell tumor of the ovary, constitutes a significant proportion of cases within this category [8, 9]. Our study revealed 10 cases of dysgerminoma out of a total of 21 malignant germ cell tumors, accounting for 48% of the malignant cases and 6.8% of all germ cell tumors. These cases were predominantly found in the 21–30 years age group and exhibited the characteristic histopathological pattern of dysgerminoma. They typically manifest as well-circumscribed, solid masses within the ovarian tissue. They tend to be relatively large and may vary in size, ranging from a few centimeters to more extensive dimensions. The tumor’s consistency is usually firm, and it may appear pale or grayish white in color (Fig. 7). Cross-sectionally, dysgerminomas display a homogenous appearance with minimal cystic spaces or necrotic regions [10]. This uniformity is a notable contrast to some other ovarian tumors that might show more intricate cystic and solid configurations.

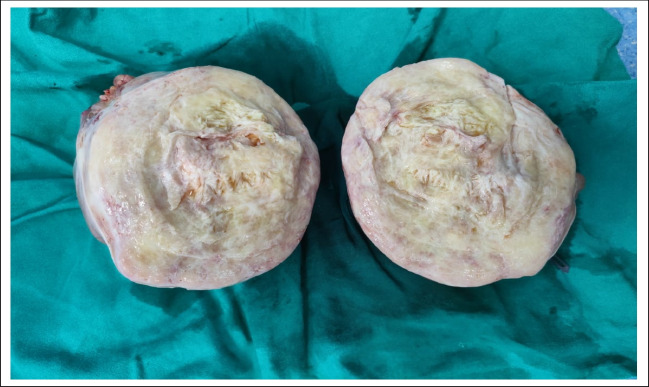

Fig. 7.

Gross picture of dysgerminoma

Yolk sac tumors, also known as endodermal sinus tumors, emerged as the second most common malignant germ cell tumors in our study. These tumors were identified in 4 cases, in a 14-year-old, 16, 20, and a 21-year-old individual. The tumors exhibited the classic reticulocystic pattern and Schiller–Duval bodies, along with the presence of characteristic hyaline globules [11].

The emergence of mixed germ cell tumors, comprising at least two different germ cell components, adds a layer of complexity to this group of tumors [12]. Such combinations, notably the pairing of dysgerminoma and yolk sac tumor, have been observed in a significant portion of cases, underscoring a possible common histogenesis for this group of tumors. We reported a unique case of a mature cystic teratoma alongside rhabdomyosarcoma in a 31-year-old female.

Non-gestational choriocarcinoma is an exceptionally rare entity within the realm of germ cell tumors, known for its distinctive histopathological features and challenging clinical management [13]. In our study of 145 germ cell tumor cases, encountering two instances of non-gestational choriocarcinoma underscores the rarity of this malignancy.

Choriocarcinoma, characterized by the presence of trophoblastic elements, is most commonly associated with gestational trophoblastic disease originating from placental tissue during pregnancy. However, non-gestational choriocarcinoma, originating outside the context of pregnancy, is a unique phenomenon that demands careful consideration due to its potential diagnostic and therapeutic complexities. Histopathologically, non-gestational choriocarcinomas often exhibit a mixed composition of cytotrophoblastic and syncytiotrophoblastic elements [14]. These tumor cells express human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a key diagnostic marker. Microscopically, they may display a dual population of cells, ranging from mononuclear cytotrophoblasts to multinucleated syncytiotrophoblasts, often forming characteristic syncytial knots.

Clinically, non-gestational choriocarcinomas can present a diagnostic challenge due to their rarity and resemblance to other germ cell tumor types. Moreover, their potential for hCG production can lead to elevated serum hCG levels, which may complicate the diagnostic process. Surgical resection, followed by chemotherapy, remains the mainstay of treatment for these tumors, although their aggressive nature and unpredictable behavior necessitate individualized management approaches. The occurrence of two cases of non-gestational choriocarcinoma in our study raises important questions about its etiology, potential underlying genetic factors, and its relationship to other germ cell tumor subtypes. Further research, encompassing genetic analyses and larger case studies, is warranted to unravel the intricate mechanisms driving the development of non-gestational choriocarcinoma.

There are differences in presentation between benign and malignant cases. Typically, benign tumors, such as mature teratomas, present themselves as asymptomatic masses or with mild, non-specific symptoms like abdominal discomfort. On the other hand, malignant germ cell tumors can lead to a range of symptoms, including abdominal pain, distension, irregular menstruation, or hormonal imbalances due to tumor secretion.

Benign tumors, such as mature teratomas, typically require surgical removal, with the primary objective being complete resection to prevent complications such as rupture or torsion. Since these tumors are localized, fertility-sparing surgeries are often possible. However, malignant germ cell tumors require a more aggressive approach. Surgery, followed by adjuvant therapies such as chemotherapy, is the mainstay of management. Preserving fertility can be challenging in malignant cases due to the need for extensive surgical interventions and aggressive treatments.

Ovarian-adnexal reporting and data system (O-RADS) is a screening tool that uses structured imaging-based assessment that can be used for the characterization and management of adnexal masses, including ovarian tumors [20]. Similar to systems used for breast and other cancers, O-RADS offers a standardized approach of utilizing ultrasound features that stratify adnexal masses into risk categories based on the likelihood of malignancy. By incorporating specific ultrasound findings such as morphology, vascularity, and solid components within adnexal masses, O-RADS aims to improve consistency in diagnosing and managing ovarian masses. It provides a structured framework for radiologists and clinicians, which aids in more precise risk stratification. This subsequently guides appropriate clinical management, including the need for further imaging or invasive procedures like biopsy or surgery.

In our study, we found relationship between tumor size more than 10 cm and having higher probability to be malignant compared to size less than 10 cm (Table 1). These have also been found in a few studies on germ cell tumors like Papic et al. [18]; they found tumors less than 10 cm and also less solid component tends to be benign compared to tumors more than 10 cm.

Table 1.

The relationship of tumor size and malignancy

| Tumor size | Malignant germ cell tumor | Benign germ cell tumor |

|---|---|---|

| < 10 cm | 4 (6.78%) | 55 (93.22%) |

| > 10 cm | 17 (19.76%) | 69 (80.2%) |

Our study primarily emphasized tumor size in diagnosing malignancy, and we acknowledge that considering a broader spectrum of ultrasound features, along with specific tumor markers, is pivotal in achieving a more comprehensive diagnosis. Incorporating these additional parameters, such as the presence of solid components, septations, vascularity, and specific tumor markers like β-hCG and AFP, can significantly enhance the accuracy and reliability of diagnosing malignant ovarian germ cell tumors, but all details such as regarding USG features could not be extracted from all cases records.

In summary, germ cell tumors represent a diverse spectrum of ovarian tumors with varying histological characteristics and clinical implications. Understanding their classifications, prevalent subtypes, and possible combinations of components sheds light on the intricate nature of these tumors and their potential implications for affected individuals. Despite the rarity of certain combinations, a comprehensive understanding of germ cell tumors is crucial for accurate diagnosis and informed clinical decision-making.

Conclusion

This retrospective study covers a span of 3 years and includes 145 cases of germ cell tumors in a tertiary cancer hospital in North-Western India. It provides valuable insights into the prevalence, diverse histological subtypes, age distribution, and clinical manifestations of these tumors in this specific geographic context. The study shows that teratomas, both mature and immature, are the most prevalent type, followed by dysgerminomas, yolk sac tumors, and non-gestational choriocarcinomas, which are relatively rare occurrences. This underlines the heterogeneity of germ cell tumors in this region.

The study also reveals that tumor size of more than 10 cm warrants suspicion of malignancy when a solid component is also present. The age distribution of the cases, with a noticeable peak in the 21–30 years age group, aligns with well-documented patterns and highlights the significance of heightened vigilance and timely diagnosis among this demographic.

Although the study has some limitations, including its retrospective design and focus on a single center, it provides a comprehensive overview of germ cell tumors in this specific region. The findings serve as a foundation for further research, emphasizing the need for larger-scale studies to validate the observed trends and explore the underlying genetic, environmental, and clinical factors influencing germ cell tumors in North-Western India. Overall, this study contributes valuable insights into the prevalence, clinical manifestations, and histopathological attributes of germ cell tumors within a defined context. It underscores the necessity for ongoing research, heightened clinical awareness, and personalized management strategies to improve patient outcomes and advance our understanding of these complex neoplasms.

Abbreviations

- hCG

Human chorionic gonadotropin

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- WHO

World Health organization

Author Contribution

AB, CS, and KKL conceived the idea. PMS, PP, and AB designed the study and laid the framework for data collection. AB and KKL did data collection and data entry. CS and SS supervised data entry and did data analyses. DM and SS laid down the framework for the paper and supervised data analysis. AB and KKL wrote the manuscript. SS and AB helped review literature. KKL and PP helped in editing and formation of the final draft.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

Approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of SMS medical college, Jaipur, was taken for the conduct of this study.

Consent to Participate

Well informed consent from patients was taken.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nogales FF, Dulcey I, Preda O. Germ cell tumors of the ovary: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(3):351–362. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0547-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sah SP, Uprety D, Rani S. Germ cell tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 121 cases from Nepal. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(4):303–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2004.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaur B. Pathology of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. Diagn Histopathol. 2020;26(6):289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.mpdhp.2020.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gică N, Peltecu G, Chirculescu R, Gică C, Stoicea MC, Serbanica AN, Panaitescu AM. Ovarian germ cell tumors: pictorial essay. Diagnostics. 2022;12(9):2050. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12092050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medeiros F, Strickland KC (2018) Germ cell tumors of the ovary. In: Diagnostic gynecologic and obstetric pathology. Elsevier pp 949–1010

- 6.Benjapibal M, Boriboonhirunsarn D, Suphanit I, Sangkarat S (2000) Benign cystic teratoma of the ovary: a review of 608 patients. J Med Assoc 83(9):1016–20. Thailand Chotmaihet Thangphaet [PubMed]

- 7.Cagino K, Levitan D, Schatz-Siemers N, Zarnegar R, Chapman-Davis E, Holcomb K, Frey MK (2020) Multiple malignant transformations of an ovarian mature cystic teratoma. Ecancermedicalscience 14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Kassanos D. Germ cell tumors of the ovary. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(5):427–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth LM, Talerman A. Recent advances in the pathology and classification of ovarian germ cell tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25(4):305–320. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000225844.59621.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warnnissorn M, Watkins JC, Young RH. Dysgerminoma of the ovary: an analysis of 140 cases emphasizing unusual microscopic findings and resultant diagnostic problems. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45(8):1009–1027. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young RH, Wong A, Stall JN. Yolk sac tumor of the ovary: a report of 150 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022;46(3):309–325. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaaban AM, Rezvani M, Elsayes KM, Baskin H, Jr, Mourad A, Foster BR, Jarboe EA, Menias CO. Ovarian malignant germ cell tumors: cellular classification and clinical and imaging features. Radiographics. 2014;34(3):777–801. doi: 10.1148/rg.343130067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cronin S, Ahmed N, Craig AD, King S, Huang M, Chu CS, Mantia-Smaldone GM. Non-gestational ovarian choriocarcinoma: a rare ovarian cancer subtype. Diagnostics. 2022;12(3):560. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12030560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Q, Guo C, Zou L, Wang Y, Song X, Ma Y, Liu A. Clinicopathological analysis of non-gestational ovarian choriocarcinoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(4):2599–2604. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moniaga NC, Randall LM. Malignant mixed ovarian germ cell tumor with embryonal component. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24(1):e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lahoud RM, O'Shea A, El-Mouhayyar C, Atre ID, Eurboonyanun K, Harisinghani M. Tumor markers and their utility in imaging of abdominal and pelvic malignancies. Clin Radiol. 2021;76(2):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geerts I, Vergote I, Neven P, Billen J (2009) The role of inhibins B and antimüllerian hormone for diagnosis and follow-up of granulosa cell tumors. Int J Gynecol Cancer 19(5):847–55 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Papic JC, Finnell SM, Slaven JE, Billmire DF, Rescorla FJ, Leys CM. Predictors of ovarian malignancy in children: overcoming clinical barriers of ovarian preservation. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(1):144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCluggage WG, Singh N, Gilks CB 2022 Key changes to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of female genital tumours introduced in the 5th edition (2020). Histopathology 80(5):762–78 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Gargan ML, Frates MC, Benson CB, Guo Y. O-RADS ultrasound version 1: a scenario-based review of implementation challenges. Am J Roentgenol. 2022;219(6):916–927. doi: 10.2214/AJR.22.28061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams PL, Dubbins PA, Defriend DE. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of ovarian dermoid cysts: a pictorial review of the characteristic sonographic signs. Ultrasound. 2011;19(2):85–90. doi: 10.1258/ult.2011.011008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khunteta N, Sulaniya C, Mangal S, Gupta S, Nahata V (2023) Ovarian tumors: a retrospective study at tertiary care cancer centre. New Indian J Obgyn. Available from: https://journal.barpetaogs.co.in/pdf/9923.pdf. Accessed 12 Nov 2023