Abstract

Protein production by ribosomes is fundamental to life, and proper assembly of the ribosome is required for protein production. The RNA, which is post-transcriptionally modified, provides the platform for ribosome assembly. Thus, a complete understanding of ribosome assembly requires the determination of the RNA post-transcriptional modifications in all of the ribosome assembly intermediates and on each pathway. There are 26 RNA post-transcriptional modifications in 23S RNA of the mature Escherichia coli (E. coli) large ribosomal subunit. The levels of these modifications have been investigated extensively only for a small number of large subunit intermediates and under a limited number of cellular and environmental conditions. In this study, we determined the level of incorporations of 2-methyl adenosine, 3-methyl pseudouridine, 5-hydroxycytosine, and seven pseudouridines in an early-stage E. coli large-subunit assembly intermediate with a sedimentation coefficient of 27S. The 27S intermediate is one of three large subunit intermediates accumulated in E. coli cells lacking the DEAD-box RNA helicase DbpA and expressing the helicase inactive R331A DbpA construct. The majority of the investigated modifications are incorporated into the 27S large subunit intermediate to similar levels to those in the mature 50S large subunit, indicating that these early modifications or the enzymes that incorporate them play important roles in the initial events of large subunit ribosome assembly.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Ribosome assembly is a complex process that involves many intermediates and pathways.1,2 RNA molecules provide the platform for ribosome assembly.3 In all known organisms, the rRNA (rRNA) molecules are extensively post-transcriptionally modified.4 The rRNA modifications regulate RNA folding, RNA interactions with ribosomal proteins (r-proteins), the translation process, and antibiotic resistance.3,5-9 In addition, a few RNA modifying enzymes serve as RNA chaperons.10,11 Lastly, the rRNA modifications provide advantages during environmental stress.8,12 Thus, characterizing the rRNA modifications in all the intermediates accumulated during ribosome assembly and in each pathway is required for a complete understanding of ribosome maturation in the cell, which could facilitate the development of novel antibiotics and improve the understanding of how cells adapt to environmental stress. Here, we investigate the incorporation of 10 rRNA post-transcriptional modifications in an early-stage, large subunit ribosome intermediate of Escherichia coli (E. coli).

The E. coli ribosome migrates in a sucrose gradient as a particle with a sedimentation coefficient of 70S and is composed of small and large subunits.13 The properly assembled small subunit migrates in a sucrose gradient as a particle with a sedimentation coefficient of 30S, while the properly formed large ribosome subunit migrates in a sucrose gradient as a particle with a sedimentation coefficient of 50S. The 50S large subunit is made up of 33 r-proteins and two RNA molecules: 5S rRNA, which is 120 nucleotides long, and 23S, which is 2907 nucleotides long.13 23S rRNA of the properly formed 50S contains 26 RNA post-transcriptional modifications.14,15 No modifications have been observed in E. coli 5S rRNA.3 The most abundant modifications in 23S rRNA are pseudouridines (Ψs) combined with methylated nucleotides. The 10 pseudouridines of 23S rRNA (Ψs) are at nucleotide positions 748, 957, 1915, 1919, 1921, 2461, 2508, 2584, 2608, and 2609.14 The pseudouridine 1919 is methylated at the N3 position (m3Ψ).14 The other methylated nucleotides are 1-methylguanine 747, 5-methyluridine (m5U) 749, 6-methyladenine (m6A) 1620, 2-methylguanine (m2G) 1837, m5U 1943, 5-methylcytidine 1966, m6A 2034, 7-methylguanine 2073, 2′O-methylguanine 2255, m2G 2449, 2′O-methylcytidine 2502, 2-methyladenine (m2A) 2507, and 2′O-methyluridine 2556.14 Moreover, 23S rRNA contains 5-hydroxycytidine (OH5C) 2505 and dihydrouridine 2453.14,15 To date, the levels of modifications have been investigated only for a small number of large subunit ribosomal intermediates and under a limited number of cellular conditions.2,16-20

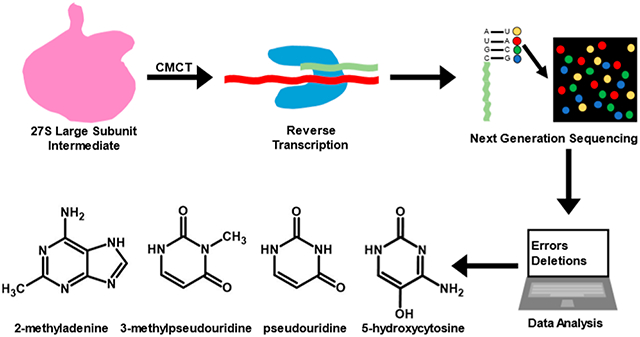

Recently, we determined the levels of 12 23S rRNA modifications in the 35S and 45S intermediates, accumulating in cells expressing the helicase inactive R331A DbpA.20 The modifications we characterized are as follows: Ψ 748, Ψ 957, Ψ 1915, m3Ψ 1919, Ψ 1921, Ψ 2461, Ψ 2508, Ψ 2584, Ψ 2608, Ψ 2609, OH5C 2505, and m2A 2507. These modifications were determined by treating the 23S rRNA with 1-cyclohexyl-3-(2-morpholinoethyl) carbodiimide metho-p-toluenesulfonate (CMCT) followed by alkaline reaction conditions. CMCT adds adducts to Ψ at the N1 and N3 positions, G at the N1 position, U at the N3 position, and unknown positions of m2A and OH5C nucleotides.20-23 Exposing the RNA to alkaline reaction conditions hydrolyzes the CMCT adducts from N1 of Ψ, N1 of G, and N3 of U.21,22 On the other hand, the CMCT adducts incorporations at m2A and OH5C nucleotides and N3 of Ψ are resistant to alkaline treatment.20-22 The Ψ, m2A, and OH5C CMCT modifications and methylation at the N3 position of Ψ produce reverse transcriptase mismatches and deletions.20 We determined the extent of the Ψ, m3Ψ, m2A, and OH5C in the 23S rRNA of 35S and 45S intermediates by comparing the deletions and mismatches of the reverse transcriptase reaction in the 35S or 45S intermediates’ 23S rRNA with those of the wild-type 50S large subunit’s 23S rRNA.20 The reverse transcriptase products were sequenced using Illumina next-generation sequencing (NGS), while the errors of the reverse transcriptase were computed using ShapeMapper.24

In this work, we also used the Illumina NGS and ShapeMapper24 to determine the extent of Ψ 957, Ψ 1915, m3Ψ 1919, Ψ 1921, Ψ 2461, Ψ 2508, Ψ 2584, Ψ 2608, Ψ 2609, OH5C 2505, and m2A 2507 modifications in a large subunit intermediate with a sedimentation coefficient of 27S. The 27S intermediate, similar to 35S and 45S intermediates, accumulates in cells expressing R331A DbpA.25 The 27S intermediate accumulates at an earlier stage of large subunit ribosome assembly than the 35S and 45S intermediates.25 However, because the three intermediates rearrange to form native 50S via three independent pathways,25 the modifications present in the 35S or the 45S intermediates are not necessarily present in the 27S intermediate. Hence, the 23S rRNA modifications of the 27S intermediate remain unknown, and the determination of these modifications is the objective of this study.

Lastly, based on the sedimentation coefficient, the 27S intermediate is a very early-stage large subunit assembly intermediate.18,25-28 The characterizations, in the present work of 10 23S rRNA modifications’ levels, and the determinations of when the modification enzymes act in the pathway where the 27S intermediate accumulates, will inform on the early steps and events of in vivo large subunit ribosome assembly. These steps and events remain largely enigmatic.1,29,30

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. 27S Intermediate Preparation.

The 27S intermediate was purified from the cells precisely in the same manner as the 35S and 45S intermediates and the wild-type 50S large ribosome subunit were purified in our previous study.20 The 27S intermediate was purified from E. coli BLR (DE3) pLysS ΔdbpA: kanR cells expressing the helicase inactive R331A DbpA protein from the pET3a plasmid.25 200 mL of cells were grown at 37 °C in a medium consisting of 10 g/L tryptone, 1 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl, 100 μg/mL carbenicillin, and 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol until they arrived at an optical density of about 0.3 at 600 nm wavelength (OD600nm).25 No isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside was used to induce the R331A DbpA protein production. The R331A DbpA protein production was a consequence of the basal expression of the R331A DbpA protein from the pET3a plasmid.18,20,25,31

The cells were precipitated by spinning at 6500g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellets were resuspended in a buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 30 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM MgCl2, 4 mM BME (β-mercaptoethanol), and 300 μg of lysozyme. The resuspended cells were incubated in ice for 30 min. To further break the cells’ membranes, the samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and thawed at room temperature. The freeze and thaw cycle was repeated two more times. Subsequently, the DNA was digested by incubating the lysed cells with 20 units of RNase-free DNase I (New England Biolabs) for 90 min in ice. The cell debris was cleared by centrifuging the mixture at 17,000g for 30 min at 4 °C. After that, about 80 OD260nm of the cleared cell lysate was either directly loaded onto a 38 mL linear 20–40% sucrose gradient or stored at −80 °C to be loaded on the sucrose gradient at a later time.

The BioComp Gradient Master system was used to create the linear 20–40% sucrose gradients. The gradients were made in a buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES KOH (pH 7.5), 150 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 4 mM BME. To separate ribosomal particles, the sucrose gradients were spun at a centrifugal force of 174,587g for 16 h at 4 °C.

To isolate the 27S intermediate from other ribosomal particles, the 20–40% sucrose gradients were fractionated using the ISCO Teledyne R1 Foxy Jr fraction collector linked to the SYR-101 syringe pump.20,25 70% sucrose solution was used to push the gradient from the bottom. The gradient fractions were collected in flat-bottom 260 nm ultraviolet transparent 96-well plates (Corning). The plates’ absorbance at 260 nm was read using the SpectraMax Plus 384 plate reader (Molecular Devices) (Figure S1). The fractions containing the 27S intermediate samples were combined and concentrated, and the sucrose solution was exchanged with a buffer consisting of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, and 4 mM BME. Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (Millipore Sigma) with a pore size of 10 kDa were used for the 27S fractions’ buffer exchange and concentration. The concentrated 27S samples were either immediately employed for the CMCT modification experiments or stored at −80 °C for later use.

In a linear 20–40% sucrose gradient, the fractions containing the 27S intermediate migrated near and together with the 30S small ribosome subunit fractions (Figure S1).25 Consequently, the isolated 27S intermediate samples also contained 16S rRNA from the 30S small ribosome subunit in addition to 23S rRNA.25 The presence of 16S rRNA is inconsequential for our data analysis because the ShapeMapper 1.2 pipeline correctly discriminates between the 16S and 23S rRNA Illumina NGS reads and aligns to 23S rRNA gene sequence only the 23S rRNA NGS reads.20,24 The 16S rRNA NGS reads are not aligned by the ShapeMapper 1.2 to 23S rRNA gene sequence and are disregarded.

2.2. CMCT-NaHCO3 Modification of 23S rRNA.

The CMCT chemical modification of the 27S intermediate’s 23S rRNA was carried out precisely as previously described for the 35S and 45S intermediates’ and wild-type 50S large subunit’s 23S rRNA.20 To briefly summarize, the 23S rRNA was extracted from the 27S intermediate using phenol/chloroform. The naked rRNA was treated with 170 mM CMCT for 30 min at 37 °C. The CMCT modification reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.3 M sodium acetate, pH 5.5. To hydrolyze the CMCT adducts from N1 of Ψ, N1 of G, and N3 of U nucleotides, the rRNA was incubated with NaHCO3 pH 10.4 at 37 °C for 2.5 h and at 65 °C for 30 min.32 The extended incubation of RNA with NaHCO3 at high temperatures is required for the complete hydrolysis of the CMCT adducts from N1 of Ψ, N1 of G, and N3 of U nucleotides.32 The NaHCO3 hydrolysis reaction was stopped with 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5).33 Lastly, the rRNA was precipitated in ethanol and subsequently used for Illumina NGS library generation.

To determine the presence or the lack of Ψ, m3Ψ, OH5C, and m2A in the 27S intermediate, CMCT and NaHCO3 treatments were applied to two different biological samples, while one sample was treated solely with NaHCO3. The sample treated solely with NaHCO3 was the control sample, and this sample was used to calculate the background-corrected mutation rates.20

2.3. Illumina Sequencing.

The Illumina NGS library preparation was carried out precisely as described in our previous study.20 In short, the Randomer Workflow of the selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension and the mutational profiling (SHAPE-MaP) protocol were employed for Illumina NGS library preparation.24 The random primer length used for the Superscript II (Invitrogen) reverse transcriptase reaction was 9 nucleotides long. The reverse transcriptase reaction was performed in the presence of 6 mM MnCl2. The 9 nucleotide-long random primer mix was purchased from New England Biolabs.

The Nextera XT kit from Illumina was employed to simultaneously fragment the DNA and add the sequencing adaptors. The DNA was sequenced using the MiSeQ 2 × 150 paired-end Illumina platform. The sequencing adaptors were trimmed before ShapeMapper 1.2 data analysis.

2.4. Determination of 23S rRNA Ψ, m3Ψ, OH5C, and m2A Post-transcriptional Modifications in the 27S Intermediate.

SHAPE-MaP Randomer Workflow used in our study is appropriate for the investigation of RNA molecules longer than 500 nucleotides, while molecules shorter than 150 nucleotides are poorly recovered.24 23S rRNA is 2907 nucleotides long, and 5S rRNA is 120 nucleotides long. Thus, the Randomer Workflow used here cannot be employed to investigate the 27S intermediate’s 5S rRNA modifications. On the other hand, this workflow is ideal for the investigation of the 27S intermediate’s 23S rRNA modifications.

SHAPE-MaP Randomer Workflow and the ShapeMapper 1.2 program utilizing Bowtie 2 are suitable for the analysis of complex mixtures of RNA molecules including complete RNA transcriptomes.24 Bowtie 2 is employed extensively for aligning NGS data,34 and with no significant sequence similarities between 23S rRNA and 16S rRNA,13 will correctly align the 23S rRNA fragment from the 27S sample to the rrlB gene. For this study, the 16S rRNA reads were disregarded.

Once the reads were aligned, the level of the 23S rRNA modifications in the 27S intermediate was computed by comparing the mutation rates of 23S rRNA in the 27S intermediates obtained in this study to the mutation rates of the wild-type 50S large subunit obtained in our previous study.20 The mutation rate for each residue of the 27S intermediate’s 23S rRNA was computed precisely as in our previous work.

ShapeMapper 1.2 was used to calculate mutation rates.24 For the mutation rate computations, the ShapeMapper 1.2 suggested parameters for the Randomer primer workflow and the Nextera XT kit were used.24 The mutation rates of a nucleotide were computed by ShapeMapper 1.2 as the ratio of the sum of misincorporations plus deletions divided by the read depth.24 In other words, the ShapeMapper 1.2 mutation rate is the fraction of the reverse transcriptase reaction errors at a specific nucleotide position in the 23S rRNA.

After we computed the values of the mutation rates, the mutation rates were background-corrected.20 The background-corrected mutation rate for each nucleotide was acquired by subtracting from the mutation rate of the nucleotide in the experimental sample the mutation rate of the nucleotide in the control sample, as described in the equation below.20

| (1) |

In eq 1, is the background-corrected mutation rate for nucleotide of biological replicate . is the ShapeMapper 1.2-calculated mutation rate for the experimental samples’ nucleotide and biological replicate . Lastly, is the ShapeMapper 1.2-calculated mutation rate for the control sample’s nucleotide .

The average background-corrected mutation rate was computed using this equation20

| (2) |

In eq 2, is the average mutation rate background-corrected for nucleotide . and are the background-corrected mutation rates for nucleotide and biological replicates 1 and 2, respectively, as computed in eq 1.

The standard deviations were computed using this equation20

| (3) |

In eq 3, is the standard deviation of the error for the averages calculated by eq 2. is the background-corrected average mutation rate, calculated using eq 2. and are the background-corrected mutation rates for biological replicates 1 and 2, which were computed from eq 1.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The determination of whether a nucleotide was modified at the same level in the 27S intermediate and wild-type 50S large subunit, or if a nucleotide was modified significantly less in the 27S intermediate than in the wild-type 50S large subunit, was made by comparing the average mutation rates’ (eq 2), the standard deviations’ (eq 3), and the 95% confidence intervals' (Table S1) values of the 27S and 50S particles’ nucleotides.20 For Ψ 748 and Ψ1915, the mutation rate standard deviation values were 1.5 and 0.61 folds of the values of the average mutation rates, respectively (Table 1). Due to the large mutation rate standard deviation values when compared to the mutation rate average values, the NGS data were not used to determine the level of modification for the 784 and 1915 nucleotides of the 27S intermediate.

Table 1.

23S rRNA Modification Composition

| 23S rRNA modificationa | mutation rateb | |

|---|---|---|

| 27S | 50Sd | |

| Ψ 748 | 0.008 ± 0.012 | 0.029 ± 0.001 |

| Ψ 957 | 0.253 ± 0.005 | 0.261 ± 0.012 |

| Ψ 1915 | 0.018 ± 0.011 | 0.039 ± 0.005 |

| m3Ψ 1919c | 0.139 ± 0.011 | 0.605 ± 0.004 |

| Ψ 1921 | 0.038 ± 0.003 | 0.156 ± 0.006 |

| Ψ 2461 | 0.118 ± 0.010 | 0.108 ± 0.003 |

| OH5C 2505 | 0.075 ± 0.038 | 0.265 ± 0.006 |

| m2A 2507 | 0.089 ± 0.031 | 0.090 ± 0.008 |

| Ψ 2508 | 0.085 ± 0.001 | 0.080 ± 0.000 |

| Ψ 2584 | 0.337 ± 0.047 | 0.322 ± 0.010 |

| Ψ 2608 | 0.050 ± 0.012 | 0.034 ± 0.001 |

| Ψ 2609 | 0.065 ± 0.009 | 0.070 ± 0.000 |

23S rRNA modifications investigated in this study.

The values shown are the averaged background-corrected mutation rates from two biological replicates (eq 2). The listed errors reflect the standard deviations (eq 3).

As explained in the Results and Discussion, the average mutation rate for m3Ψ 1919 was not background-corrected.

The average mutation rates and the standard deviation values shown for the wild-type 50S large subunit are from our previous publication.20

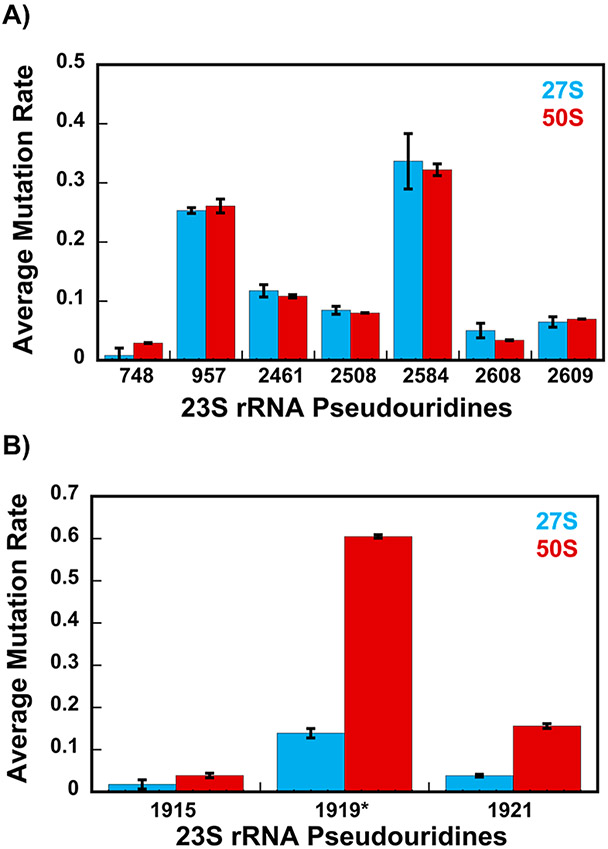

The average mutation rates for nucleotides 957, 2461, 2508, 2584, 2608, and 2609 of 23S rRNA are similar between the 27S and 50S native large subunits (Figure 1A and Tables 1 and S1). In the native 50S, all these nucleotides are U nucleotides isomerized to Ψ nucleotides.14 Thus, the isomerization of U nucleotides 957, 2461, 2508, 2584, 2608, and 2609 to Ψ nucleotides has taken place at the same level in the 27S intermediate and the wild-type 50S large ribosome subunit.

Figure 1.

Average mutation rates (with error bars depicting the standard deviation) of the 27S (blue) and 50S (red) Ψ modifications. (A) Ψ isomerizations at positions 957, 2461, 2508, 2584, 2608, and 2609, which occur at the early stages of large subunit ribosome assembly, have similar levels of average mutation rates in the 27S and 50S. (B) Ψ isomerizations, which occur after the 27S intermediate accumulates in the cell, are U nucleotides 1919 and 1921. The U nucleotides 1919 and 1921 to Ψ isomerizations and methylation of Ψ 1919 occur at the intermediate and/or late stage of large subunit ribosome assembly. As explained in the Results and Discussion, we are showing the background-uncorrected average mutation rates for Ψ 1919*. All the average mutation rate and the standard deviation values for the wild-type 50S large subunit depicted in this figure are from our previous publication.20 The averages and standard deviations depicted in this figure were calculated using eqs 2 and 3.

The RluC enzyme isomerizes U nucleotides 957, 2508, and 2584 to Ψ nucleotides.35 The RluE enzyme isomerizes U 2461 to Ψ,36 the RluF enzyme isomerizes U 2608 to Ψ,36 while the RluB enzyme isomerizes U 2609 to Ψ.36 The observation that the average mutation rates for nucleotides 957, 2461, 2508, 2584, 2608, and 2609 are similar between the 27S intermediate and the 50S large subunit (Figure 1A and Tables 1 and S1) indicates that RluC, RluE, RluF, and RluB pseudouridine synthases have performed their Ψ isomerase functions before the 27S intermediate is accumulated in E. coli cells.

Since the 27S particle is a very early-stage large subunit intermediate,25 the RluC, RluE, RluF, and RluB pseudouridine synthases perform the U to Ψ isomerizations at the nascent stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.

Recently, we demonstrated that in cells expressing the helicase inactive R331 DbpA, on the large subunit ribosome assembly pathway where the 35S accumulates, the RluC, RluE, RluF, and RluB pseudouridine synthases also perform their functions during the early stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.20 Moreover, the RluC, RluE, RluF, and RluB enzymes were shown to perform their functions at the early stages of large subunit ribosome assembly in cells treated with chloramphenicol17 or erythromycin,17 in cells lacking the DEAD-box RNA helicase SrmB,19 and in wild-type cells.19 Therefore, on the large subunit assembly pathways investigated to date, the rRNA and rRNA-protein structures that the RluC, RluE, RluF, and RluB pseudouridine synthases recognize are populated in the early stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.

RluD concurrently isomerizes U nucleotides 1915, 1919, and 1921 to Ψ nucleotides.37 Subsequently, RlmH adds a methyl group at the N3 position of Ψ 1919.38,39 The standard deviation for 1915 is significant when compared to the average mutation rate for that nucleotide (Figure 1B, Table 1). Thus, based on the NGS data, we cannot make a determination concerning the magnitude of Ψ incorporation at position 1915.

In the control sample, the mutation rate at the 1919 nucleotide consists of the reverse transcriptase errors produced by RlmH methylation of the 1919 Ψ nucleotide’s N3 position.20 In the CMCT-treated sample, the CMCT adduct is added at the N3 position of the 1919 Ψ nucleotides, which lack the RlmH N3 methylation, and at the N3 position of the 1921 Ψ nucleotides. Thus, the mutation rates we observe for the 1919 nucleotides in the CMCT-treated samples are the sum of the errors caused by the CMCT adduct additions plus the RlmH methylation at the N3 position of the Ψ nucleotides. Because ShapeMapper 1.2 clusters the reverse transcription errors in an NGS read adjacent in sequence to the last 3′ end-modified nucleotide,40 a fraction of the reverse transcription errors of the 1919 Ψ nucleotides in the CMCT-treated samples are counted by ShapeMapper 1.2 as errors of the 1921 nucleotides.20 This error counting method by ShapeMapper 1.2, together with the observation that in a fraction of the 27S intermediate, U 1919 is modified to m3Ψ, results in a negative background-corrected average mutation rate for the 1919 nucleotide (Table S2). Thus, the 1919 nucleotide’s average mutation rates shown in Figure 1B and Tables 1 and S1, which are positive numbers, are the background-uncorrected average mutation rates.

The finding that the average mutation rates for U nucleotides 1919 and 1921 are significantly smaller in the 27S intermediate when compared to those in the wild-type 50S large subunit reveals that RluD has not performed U 1919 or U 1921 to Ψ isomerization in the 27S intermediate (Figure 1B and Tables 1 and S1). Since RlmH in the cell expressing RluD acts after RluD has isomerized U 1919 to Ψ,39 the comparison of the average mutation rates for the 1919 nucleotide between the 27S intermediate and the wild-type 50S large subunit also reveals that RlmH has not performed its function in the 27S intermediate (Figure 1B and Tables 1 and S1).

Our recent study demonstrated that the RluD enzyme, in the cells expressing R331A DbpA and on the large subunit ribosome assembly pathway where the 45S intermediate accumulates, acts at the late stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.20 Similarly, the RluD enzyme was shown to act at the late stages of large subunit ribosome assembly in wild-type cells2,19 and in cells lacking the DEAD-box RNA helicases SrmB19 or DeaD.16 Moreover, in cells treated with chloramphenicol or erythromycin, the U nucleotides 1915, 1919, and 1921 are isomerized to Ψ nucleotides by the RluD enzyme during the intermediate-to-late stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.17 Therefore, in all of the in vivo ribosome assembly pathways investigated to date, including this study’s U nucleotides 1919 and 1921, the RluD enzyme acts at either the intermediate or late stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.

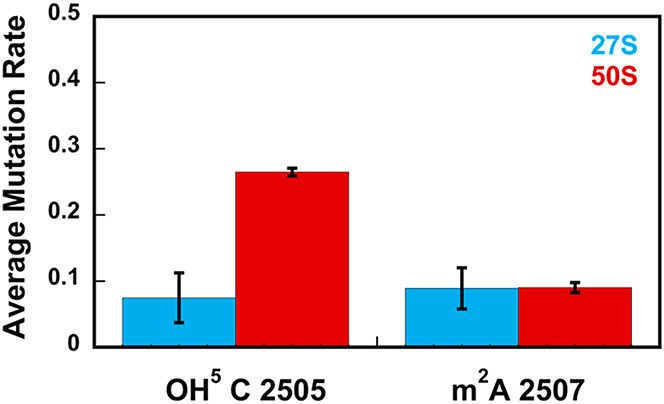

The RlhA enzyme performs the hydroxylation at the C5 position of 23S rRNA’s C 2505 nucleotide.41 The average mutation rate of C 2505 in the 27S intermediate is significantly smaller than the average mutation rate of C 2505 in the wild-type 50S large subunit (Figure 2 and Tables 1 and S1). Thus, the C 2505 is not extensively hydroxylated in the 27S and the RlhA enzyme has not performed its function in this intermediate. Because the 27S particle is an early-stage large subunit intermediate, the RlhA enzyme acts on the pathway where the 27S intermediate accumulates at the intermediate and/or late stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.

Figure 2.

Hydroxylation of cytosine 2505 at the C5 position is performed during the intermediate- and/or late stages of large subunit ribosome assembly, while the methylation of adenine 2507 at the C2 position is performed before the 27S intermediate accumulates in the cell, thus, at the early stages of large subunit ribosome assembly. The data shown are the averages of mutation rates obtained from two biological replicates for nucleotides 2505 and 2507 of the 27S intermediate (blue) and 50S large subunit (red). The error bars represent the standard deviations from the average values. The level of modification for cytosine 2505 of the 27S intermediate is significantly smaller than the level of modification for cytosine 2505 of the 50S large subunit, while the level of modification for A 2507 is similar in the 27S and 50S particles. All the average mutation rates and the standard deviations depicted in this figure for the wild-type 50S large subunit were obtained in our previous work.20 The averages and the standard deviations depicted in this figure were calculated using eqs 2 and 3.

The C 2505, which is located in the peptidyl transferase center (PTC), is evolutionarily conserved from bacteria to humans.12 The hydroxylation of C 2505 at the C5 position is found across many evolutionary distant bacteria.12 In addition, in yeast and humans, the C 2505 nucleotide is methylated at the C5 position.12 The location of C 2505 in the PTC combined with the determination that this nucleotide is conserved and modified across most organisms suggests that C 2505 modification plays a role in the translation process. Indeed, a recent study showed that the hydroxylation of C 2505 in E. coli decreases the in vitro rate of translation and this decrease in the rate of translation, via a process not fully understood, provides a significant advantage during oxidative stress.12 Thus, the bacterial C 2505 hydroxylation regulates the translation process.12

In addition to regulating translation, the C 2505 hydroxylation or the RlhA enzyme could regulate large subunit ribosome assembly. Alternatively, the different rRNA structures populated and/or protein—rRNA interactions taking place within different cellular or environmental conditions could regulate when the C 2505 is hydroxylated in the course of large subunit ribosome assembly.

We have shown previously that in cells expressing the helicase inactive R331 DbpA, on the pathway where the 45S accumulates, RlhA performs its function at the late stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.20 Similarly, RlhA was found to act at the late stages of large subunit ribosome assembly in cells lacking SrmB.19 On the other hand, in wild-type E. coli cells grown in minimal media, RlhA was found to act at the intermediate stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.19 Lastly, in the wild-type E. coli cells grown in Luria Broth media, RlhA was found to act at the early stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.41 Together, the present work and previous studies reveal that RlhA acts at different stages of large subunit ribosome assembly depending on the cellular or environmental conditions. Importantly, it is not clear from present data what the benefits are for the cells of incorporating the OH5C C 2505 modification, contingent upon the cellular or environmental conditions, at different time points during the course of large subunit ribosome assembly. Future structural investigation of large subunit intermediates isolated from diverse cellular and environmental conditions could elucidate how the RlhA enzyme’s interaction with 23S rRNA and/or the OH5 C 2505 modification’s incorporation in 23S rRNA are/is interconnected spatially and temporally with other processes of large subunit ribosome assembly.

The RlmN enzyme incorporates a methyl group at the C2 position of A 2507 of 23S rRNA and A 37 of several transfer (tRNA) molecules.41 The A 2507 average mutation rate is similar for the 27S intermediate and wild-type 50S large subunit (Figure 2 and Tables 1 and S1). Thus, the methyltransferase RlmN performs its function before the 27S intermediate accumulates in cells and at the nascent stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.

We showed recently that in cells expressing the inactive helicase R331 DbpA, on the pathway where the 35S accumulates, RlmN also performs its function at the early stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.20 Moreover, RlmN was shown to methylate A 2507 of 23S rRNA at the early stages of large subunit assembly in the cells treated with chloramphenicol and17 erythromycin,17 wild-type cells,19 and cells lacking the SrmB protein.19 Thus, in the various large subunit intermediates interrogated to date, RlmN methylates A 2507 in the early stages of large subunit ribosome assembly. These findings differ from those obtained when the RlmN enzyme performs its function during the tRNA maturation process. The tertiary structure of the tRNA molecules is required to support the methyltransferase activity of RlmN.42 Thus, RlmN methylates the tRNA molecules at the late stages of their maturation.42

The A 2507 nucleotide, which the RlmN enzyme methylates, is located in the PTC region of the large subunit.13 This work and previous studies determined that the RlmN acts at the early stages of large subunit ribosome assembly in several cellular and environmental conditions.17,19,20 The above determinations combined with the finding that the tertiary structure of tRNA is required to support the methyltransferase activity of RlmN,42 suggest the local PTC rRNA tertiary structure recognized by the RlmN enzyme is likely formed early during large subunit ribosome assembly. Interestingly, cryo-EM studies have shown that the PTC region as a whole matures late during large subunit ribosome assembly.1,2,19,43

4. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, using CMCT chemical treatment combined with the reverse transcriptase reaction’s deletion and mismatch counting, we characterized 10 23S rRNA modifications in a very early-stage large subunit intermediate, the 27S. The characterization of modification levels in the 27S reveals the time points when the modification enzymes perform their functions during large subunit ribosome assembly. We find that the incorporations of Ψ 957, Ψ 2461, Ψ 2508, Ψ 2584, Ψ 2608, Ψ 2609, and m2A 2507 take place before the 27S intermediate is accumulated in the cell. Thus, the enzymes that add these modifications, RluB, RluC, RluE, RluF, and RlmN, perform their functions at the initial stages of large subunit ribosome assembly before the 27S intermediate is formed (Table 2). The Ψ 1919, Ψ 1921, m3Ψ 1919, and OH5C 2505 modifications are significantly less abundant in the 27S intermediate when compared to those in the wild-type 50S large subunit. Therefore, the present study reveals that the RluD enzyme, which incorporates the Ψ 1919 and Ψ 1921 modifications; the RlmH enzyme, which methylates the Ψ 1919 nucleotide; and the RlhA enzyme, which hydroxylates the C 2505 nucleotide, are working in the above 27S intermediate modifications or will work in those modifications at the later stages of large subunit ribosome assembly (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the Large Subunit Stages at Which the Modification Enzymes Perform Their Functions in 23S rRNA

| Ribosome Large Subunit Assembly Stages | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymea | 23S rRNA Modificationb | Earlyc | Intermediate/ Latec |

| RluC | Ψ 957,2508,2584 |

|

|

| RluD | Ψ 1919, 1921 |

|

|

| RlmH | m3Ψ 1919 |

|

|

| RlhA | OH5C 2505 |

|

|

| RlmN | m2A 2507 |

|

|

| RluE | Ψ 2461 |

|

|

| RluF | Ψ 2608 |

|

|

| RluB | Ψ 2609 |

|

|

Enzymes incorporating the modifications.

The modification and the 23S rRNA sequence position.

The 27S particle is an early-stage large subunit ribosomal assembly intermediate.25 The modifications present in the 27S intermediate at similar levels as in the wild-type 50S large subunit indicate that the enzymes incorporating the modifications perform their functions at the early stage of large subunit ribosome assembly. Alternatively, the modifications significantly missing from the 27S intermediate indicate that the enzymes incorporating these modifications perform their functions at the intermediate and/or late stages of large subunit ribosome assembly.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Riley C. Gentry and the University of Florida Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research for the collection of NGS data.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant R01-GM131062, the University of Texas System Rising STARs Program, and the startup from the Chemistry and Biochemistry Department at the University of Texas at El Paso (to E.K.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.biochem.3c00291.

Examples of sucrose gradients, 95% confidence intervals of mutation rates for 27S and 50S particles’ 23S rRNA-modified nucleotides, and mutation rates of 27S and 50S particles’ m3Ψ 1919 nucleotide treated with CMCT and NaHCO3, or only NaHCO3 (PDF)

Accession Codes

E.coli RluB uniprot entry:P37765; E. coli RluC uniprot entry:P0AA39; E. coli RluD; uniprot entry:P33643; E. coli RluF uniprot entry:P32684; E. coli RlmH uniprot entry:-P0A818; E. coli RlhA uniprot entry:P76104; E. coli RlmN uniprot entry:P36979; E. coli DbpA uniprot entry:P21693.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Gyan Narayan, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79968, United States.

Luis A. Gracia Mazuca, Bioinformatics Program, The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79968, United States.

Samuel S. Cho, Department of Physics, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27109, United States; Department of Computer Science, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27109, United States

Jonathon E. Mohl, Bioinformatics Program and Department of Mathematical Sciences, The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79968, United States

Eda Koculi, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79968, United States.

Data Availability Statement

The Illumina NGS and ShapeMapper 1.2 data were deposited on Gene Expression Omnibus. The accession code for these data is GSE232539.

REFERENCES

- (1).Davis JH; Williamson JR Structure and dynamics of bacterial ribosome biogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 2017, 372, 20160181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Nikolay R; Hilal T; Schmidt S; Qin B; Schwefel D; Vieira-Vieira CH; Mielke T; Bürger J; Loerke J; Amikura K; et al. Snapshots of native pre-50S ribosomes reveal a biogenesis factor network and evolutionary specialization. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 1200–1215.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Shajani Z; Sykes MT; Williamson JR Assembly of bacterial ribosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2011, 80, 501–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Boccaletto P; Baginski B MODOMICS: An Operational Guide to the Use of the RNA Modification Pathways Database. Methods Mol. Biol 2021, 2284, 481–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kaczanowska M; Rydén-Aulin M Ribosome biogenesis and the translation process in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 2007, 71, 477–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chow CS; Lamichhane TN; Mahto SK Expanding the nucleotide repertoire of the ribosome with post-transcriptional modifications. ACS Chem. Biol 2007, 2, 610–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Decatur WA; Fournier MJ rRNA modifications and ribosome function. Trends Biochem. Sci 2002, 27, 344–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Antoine L; Bahena-Ceron R; Devi Bunwaree H; Gobry M; Loegler V; Romby P; Marzi S RNA Modifications in Pathogenic Bacteria: Impact on Host Adaptation and Virulence. Genes 2021, 12, 1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Babosan A; Fruchard L; Krin E; Carvalho A; Mazel D; Baharoglu Z Nonessential tRNA and rRNA modifications impact the bacterial response to sub-MIC antibiotic stress. microLife 2022, 3, uqac019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Gutgsell NS; Del Campo M; Raychaudhuri S; Ofengand J A second function for pseudouridine synthases: A point mutant of RluD unable to form pseudouridines 1911, 1915, and 1917 in Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA restores normal growth to an RluD-minus strain. RNA 2001, 7, 990–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gc K; Gyawali P; Balci H; Abeysirigunawardena S Ribosomal RNA Methyltransferase RsmC Moonlights as an RNA Chaperone. Chembiochem 2020, 21, 1885–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Fasnacht M; Gallo S; Sharma P; Himmelstoß M; Limbach P; Willi J; Polacek N Dynamic 23S rRNA modification ho5C2501 benefits Escherichia coli under oxidative stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 473–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Noeske J; Wasserman MR; Terry DS; Altman RB; Blanchard SC; Cate JHD High-resolution structure of the Escherichia coli ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2015, 22, 336–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ofengand J; Del Campo M Modified Nucleosides of Escherichia coli Ribosomal RNA. EcoSal Plus 1 2004, 1, DOI: 10.1128/ecosalplus.4.6.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Havelund JF; Giessing AMB; Hansen T; Rasmussen A; Scott LG; Kirpekar F Identification of 5-hydroxycytidine at position 2501 concludes characterization of modified nucleotides in E. coli 23S rRNA. J. Mol. Biol 2011, 411, 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Leppik M; Peil L; Kipper K; Liiv A; Remme J Substrate specificity of the pseudouridine synthase RluD in Escherichia coli. FEBS J. 2007, 274, 5759–5766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Siibak T; Remme J Subribosomal particle analysis reveals the stages of bacterial ribosome assembly at which rRNA nucleotides are modified. RNA 2010, 16, 2023–2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sharpe Elles LM; Sykes MT; Williamson JR; Uhlenbeck OC A dominant negative mutant of the E. coli RNA helicase DbpA blocks assembly of the 50S ribosomal subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 6503–6514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Rabuck-Gibbons JN; Popova AM; Greene EM; Cervantes CF; Lyumkis D; Williamson JR SrmB Rescues Trapped Ribosome Assembly Intermediates. J. Mol. Biol 2020, 432, 978–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Koculi E; Cho SS RNA Post-Transcriptional Modifications in Two Large Subunit Intermediates Populated in E. coli Cells Expressing Helicase Inactive R331A DbpA. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 833–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gilham PT An Addition Reaction Specific for Uridine and Guanosine Nucleotides and its Application to the Modification of Ribonuclease Action. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1962, 84, 687–688. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Naylor R; Ho NWY; Gilham PT Selective chemical modifications of uridine and pseudouridine in polynucleotides and their effect on the specificities of ribonuclease and phosphodiesterases. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1965, 87, 4209–4210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gilham PT; Ho NWY Reaction of pseudouridine and inosine with N-cyclohexyl-N’-beta-(4-methylmorpholinium)-ethylcarbodiimide. Biochemistry 1971, 10, 3651–3657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Smola MJ; Rice GM; Busan S; Siegfried NA; Weeks KM Selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension and mutational profiling (SHAPE-MaP) for direct, versatile and accurate RNA structure analysis. Nat. Protoc 2015, 10, 1643–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Gentry RC; Childs JJ; Gevorkyan J; Gerasimova YV; Koculi E Time course of large ribosomal subunit assembly in E. coli cells overexpressing a helicase inactive DbpA protein. RNA 2016, 22, 1055–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Charollais J; Pflieger D; Vinh J; Dreyfus M; Iost I The DEAD-box RNA helicase SrmB is involved in the assembly of 50S ribosomal subunits in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol 2003, 48, 1253–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Charollais J; Iost I CsdA, a cold-shock RNA helicase from Escherichia coli, is involved in the biogenesis of 50S ribosomal subunit. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 2751–2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Arai T; Ishiguro K; Kimura S; Sakaguchi Y; Suzuki T; Suzuki T Single methylation of 23S rRNA triggers late steps of 50S ribosomal subunit assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2015, 112, E4707–E4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Baßler J; Hurt E Eukaryotic Ribosome Assembly. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2019, 88, 281–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Qin B; Lauer SM; Balke A; Vieira-Vieira CH; Burger J; Mielke T; Selbach M; Scheerer P; Spahn CMT; Nikolay R Cryo-EM captures early ribosome assembly in action. Nat. Commun 2023, 14, 898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Elles LM; Uhlenbeck OC Mutation of the arginine finger in the active site of Escherichia coli DbpA abolishes ATPase and helicase activity and confers a dominant slow growth phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 36, 41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Durairaj A; Limbach PA Improving CMC-derivatization of pseudouridine in RNA for mass spectrometric detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 612, 173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bakin AV; Ofengand J Mapping of pseudouridine residues in RNA to nucleotide resolution. Methods Mol. Biol 1998, 77, 297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Langmead B; Salzberg SL Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Conrad J; Sun D; Englund N; Ofengand J The rluC gene of Escherichia coli codes for a pseudouridine synthase that is solely responsible for synthesis of pseudouridine at positions 955, 2504, and 2580 in 23 S ribosomal RNA. J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273, 18562–18566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Del Campo M; Kaya Y; Ofengand J Identification and site of action of the remaining four putative pseudouridine synthases in Escherichia coli. RNA 2001, 7, 1603–1615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Huang L; Ku J; Pookanjanatavip M; Gu X; Wang D; Greene PJ; Santi DV Identification of two Escherichia coli pseudouridine synthases that show multisite specificity for 23S RNA. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 15951–15957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Ero R; Peil L; Liiv A; Remme J Identification of pseudouridine methyltransferase in Escherichia coli. RNA 2008, 14, 2223–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ero R; Leppik M; Liiv A; Remme J Specificity and kinetics of 23S rRNA modification enzymes RlmH and RluD. RNA 2010, 16, 2075–2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Siegfried NA; Busan S; Rice GM; Nelson JAE; Weeks KM RNA motif discovery by SHAPE and mutational profiling (SHAPE-MaP). Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 959–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kimura S; Sakai Y; Ishiguro K; Suzuki T Biogenesis and iron-dependency of ribosomal RNA hydroxylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 12974–12986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Benítez-Páez A; Villarroya M; Armengod ME The Escherichia coli RlmN methyltransferase is a dual-specificity enzyme that modifies both rRNA and tRNA and controls translational accuracy. RNA 2012, 18, 1783–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Wang W; Li W; Ge X; Yan K; Mandava CS; Sanyal S; Gao N Loss of a single methylation in 23S rRNA delays 50S assembly at multiple late stages and impairs translation initiation and elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2020, 117, 15609–15619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Illumina NGS and ShapeMapper 1.2 data were deposited on Gene Expression Omnibus. The accession code for these data is GSE232539.