Abstract

Objective:

This article provides an up-to-date review of the diagnosis and management of the most common neuropathies seen in patients with diabetes.

Latest Developments:

Most neuropathies are due to hyperglycemia’s effect on small and large fiber nerves and glycemic control in individuals with type 1 diabetes reduces neuropathy prevalence. However, among people with type 2 diabetes, additional factors, particularly metabolic syndrome components, play a role and should be addressed. While length-dependent distal symmetric polyneuropathy is the most common form of neuropathy, autonomic syndromes in particularly cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is associated with increased mortality, whereas lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy and treatment-induced neuropathy cause substantial morbidity.

Essential Points:

The prevalence of diabetes continues to grow worldwide and, as a result, the burden of diabetic neuropathies is also increasing. Identifying and appropriately diagnosing these neuropathies is key to prevent progression. Until better disease-modifying therapies are identified, management remains focused on diabetes and metabolic risk factor control and pain management.

Learning objective

Diagnose and manage the spectrum of peripheral neuropathies associated with diabetes.

Introduction

In 2021, more than half a billion people worldwide had either type 1 or type 2 diabetes.1 Diabetes is one of the fastest growing diseases so that, by 2045, 783 million people will be affected.1 The burden of diabetes in the United States is equally bleak. Currently, over 32 million Americans have diabetes, yet more than one in ten are unaware of their diagnosis.1 Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are well known for their causal association with peripheral neuropathies. These neuropathies result in significant physical and psychological morbidity, including disabling pain, depression, and worse quality of life, as well as cost.2 Currently, more than 10 billion dollars a year is spent on diabetic neuropathy and its associated complications in the United States.3 Unfortunately, the prevalence of diabetic neuropathies will continue to rise as the burden of diabetes increases worldwide. Due to a lack of disease-modifying treatment for neuropathy, early diabetes diagnosis is essential to controlling factors that increase the risk of developing neuropathy. For patients with existing neuropathy, appropriate diagnosis and management is key to reduce the likelihood of developing complications, such as ulcer formation and lower extremity amputation [KP1].

The diabetic neuropathies present with a myriad of clinical signs and symptoms [KP2]. This review article will focus on the distinct clinical presentations of the most common forms of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. These include distal symmetric polyneuropathy, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy, and treatment-induced peripheral neuropathy. Clinical descriptions of these disorders will be followed by sections focused on diagnosis and management. The aim of this review is to provide neurologists with the diagnostic and management knowledge necessary to care for patients with diabetic neuropathies in conjunction with the patient’s primary care provider or endocrinologist.

Distal symmetric polyneuropathy of diabetes

Distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSPN) is the most frequent type of diabetic neuropathy. Often described as presenting with ‘stocking and glove’ symptoms, this chronic disorder presents as symmetric, altered sensation in the toes that spreads up the calves before beginning in the fingers and hands.4 Patients often report numbness, tingling, and altered sensation, including hyperalgesia. Symptoms vary dramatically between patients and almost half endorse burning, stabbing, or aching pain.5 Neurologic examination of these patients often reveals a combination of small and large nerve fiber involvement [KP3]. Reduced sensation to pinprick and temperature suggests injury to unmyelinated and thinly myelinated small fibers whereas decreased vibration, proprioception, and pressure occurs after damage to myelinated, large fibers. Weakness detected via confrontational or functional strength assessment can be seen in the setting of damage to myelinated motor fibers, though this is much less common than altered sensation.

DSPN occurs in approximately 30% of people with diabetes and is more common among people with type 2 diabetes than type 1.6 However, any form of chronically-elevated blood glucose has been associated with the development of DSPN, including pre-diabetes which is defined as a hemoglobin A1C percentage between 5.7 and 6.4 [KP4].7 While patient age is a well-known risk factor for the development of neuropathy,8 a DSPN prevalence as high as 22% has been reported among youth with type 1 diabetes indicating that individuals of all ages are vulnerable to developing this complication.9 Large population-based studies suggest that individuals of Black race/ethnicity are at higher risk for peripheral neuropathy after controlling for age and sex,10 yet it is unclear whether this association is due to a higher diabetes prevalence among non-Hispanic Black Americans or other factors. Additional diabetes-related risk factors associated with the development of DSPN include disease duration and severity, as measured by hemoglobin A1C.11 The risk of developing DSPN is further increased by comorbid medical conditions, in particular the metabolic syndrome. Individuals are diagnosed with metabolic syndrome if they have at least three of the following five conditions: elevated fasting glucose, obesity, hypertension, elevated triglycerides, and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL).12 While central obesity has been repeatedly associated with the development of DSPN, there may also be a dose-response relationship between the number of metabolic syndrome components a patient has and the risk of DSPN.11,12 Therefore, identification of metabolic syndrome components among patients with pre-existing diabetes, or pre-diabetes, is warranted [KP5].

Diagnosis

DSPN is diagnosed via clinical history and neurological examination (Case 1). Electrodiagnostic testing is generally not recommended to screen for suspected DSPN unless the patient has features that are atypical, such as rapid onset, non-length dependent symptoms, asymmetry, or motor-predominant symptoms.13 While confirmation is generally not needed for clinical care, available tests include electrodiagnostic testing for those with large fiber symptoms and exam findings and skin biopsy for intraepidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD) for small fiber symptoms and exam findings. Nerve conduction studies will be consistent with axonal loss: low amplitude responses with normal to slightly slowed distal latencies and conduction velocities. Sensory studies will be more affected than motor studies. Similar to electrodiagnostic testing, IENFD is not recommended as a routine test. IENFD of a punch skin biopsy will show decreased density of small unmyelinated nerve fibers in the epidermal skin layer. Both modalities are good, but not great diagnostic tests for the diagnosis of DSPN (areas under the curve 0.76-0.90 and 0.75-0.82 for electrodiagnostic testing and IENFD, respectively).14 However, cutoffs for an abnormal test often vary between centers and patients may be reluctant to complete these tests due to concerns regarding discomfort, particularly for IENFD which is an invasive test.

Management

Management of diabetic DSPN is focused both on risk factor modification to reduce the likelihood of disease progression and on pain management. Among patients with type 1 diabetes, glycemic control has been shown to prevent the development of DSPN and improve electrodiagnostic and vibratory threshold testing results among individuals with existing DSPN.15 While glycemic control likely plays a role in management of DSPN progression among those with type 2 diabetes, alone it has not led to a significant reduction in DSPN incidence.15 Instead, glycemic control in conjunction with modifying other metabolic syndrome components has shown promise. Medical weight loss improves multiple metabolic syndrome components among individuals with diabetes as well as neuropathy symptoms.16 While, dietary weight loss does not significantly improve examination findings, it has been associated with stabilization of IENFD.17 Therefore, medical weight loss may limit DSPN progression. Similarly, exercise is also associated with improvement in patient-reported symptoms and small fiber branching on IENFD, though, notably participants did not have a significant reduction in weight.18 To date, no intervention has resulted in improvement in electrodiagnostic testing or clinical examination. Thus, multiple interventions, or earlier intervention, may be necessary to modify DSPN progression [KP6].

In the absence of disease-modifying therapies, DSPN management is largely focused on pain management. Among individuals with DSPN, pain is often underreported and, therefore, undertreated.19,20 Recent American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guidelines support the use of four different drug classes for the treatment of painful DSPN – gabapentinoids, which includes gabapentin and pregabalin, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and sodium channel blockers.21 Topical medications, such as capsaicin, are also available and are effective in some patients.21 OPTION-DM, a recent multi-center, randomized, double blind crossover trial, showed similar clinical efficacy between amitriptyline, duloxetine, pregabalin, and gabapentin among participants with diabetic DSPN [KP7].22 Therefore, selection of initial treatment for painful DSPN should focus primarily on potential adverse effects, comorbid medical conditions, as well as medication cost. Opioids, including tramadol, likely have no role in the management of painful DSPN given the profound downsides of this class of medication.21 OPTION-DM also showed that the addition of a second agent further improved pain control among participants with a mean daily pain numerical rating scale >3 after 6 weeks.22 Therefore, combination therapy is likely a good approach for patients that are refractory to the first pain medication attempted. Further, regular assessment of a patient’s level of pain is important to facilitate medication titration [KP8].

Data regarding the impact of non-pharmacological interventions on painful DSPN are limited. Cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, and aerobic exercise may be promising among individuals with DSPN based on limited existing literature.23 While surgical interventions are available, great caution must be used when interpreting results of a recent randomized trial of spinal cord stimulation in 216 participants as it was an open label study without a sham surgery in the control arm.24 Additional investigation into non-pharmacologic pain management approaches for patients with diabetic DSPN is much needed in order to improve patients’ quality of life.

Case 1

A 50-year-old woman with a 15-year history of type 2 diabetes presents to his primary care doctor with numbness and tingling in the legs. Her symptoms began almost a year ago as altered sensation in her toes, as though her socks were too tight, and have slowly spread up her feet to her ankles and back of her legs. Sometimes she will get zaps of shooting pain in her feet, which will keep her from sleeping. She will often have to keep her feet uncovered because she finds the blankets irritating.

On examination, her body mass index (BMI) was 30.5 kg/m2. She has normal strength, reflexes, and coordination. Sensory examination showed intact proprioception at the great toes, sensation to vibration using at 128-Hz tuning fork was 5 seconds (10 seconds being normal) and there was decreased sensation to pinprick to just above the ankles. Gait is normal.

A review of her medical records revealed an elevated Hemoglobin A1C for the past 20 years, most recently 6.4%. She also had an elevated total cholesterol (220 mg/dL) and triglycerides (230 mg/dL).

Comment:

This case illustrates a typical clinical presentation for a patient with distal symmetric polyneuropathy in the setting of diabetes with slow progression in symptoms over several months with an onset that cannot be clearly defined. Further diagnostic testing is unnecessary due to the absence of atypical features. Treatment should include control of glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides integrated with exercise and diet for weight loss. Both exercise and weight loss have been shown to improve symptoms in multiple small studies. Regularly evaluating pain and initiating medications, such as SNRIs, TCAs, gabapentinoids, and/or sodium channel blockers, to reduce pain is essential to improve quality of life.

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy of diabetes

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is one of many forms of autonomic dysfunction seen in patients with diabetes. Other signs of autonomic dysfunction include gastroparesis, constipation, bladder dysfunction, and sexual and sudomotor dysfunction. Here, we have chosen to focus on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction as it is associated with increased cardiovascular events, including arrhythmia, myocardial ischemia, and mortality both from cardiovascular events as well as all causes [KP9]. A recent meta-analysis of nineteen studies (16,099 patients with diabetes) found a pooled relative risk of 3.17 [95% Confidence Interval 2.11-4.78] for increased all-cause mortality among patients with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy.25 Patients may not notice the symptoms of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy for several years and late diagnosis increases the risk of mortality.1 Further, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is associated with the development of other diabetes complications, such as stroke and renal failure.26,27 Therefore, identifying patients with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is essential to improve outcomes [KP10].

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy affects both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. Like DSPN, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy follows a length-dependent pattern, affecting the longest autonomic nerves first. As a result, early signs of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy are from parasympathetic dysfunction of the vagal nerve and include elevated resting heart rate and impaired heart rate variability. These signs are often asymptomatic. Later in the course of disease, decreased sympathetic activity, namely to peripheral efferent sympathetic vasomotor nerves, leads to decreased peripheral vasoconstriction. Combined, parasympathetic and sympathetic autonomic nerve damage eventually leads to decreased cardiac output. Therefore, patients with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy often endorse dizziness and decreased exercise tolerance early, whereas orthostatic hypotension (defined as a drop in systolic blood pressure >20 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >10 mmHg when going from lying to sitting or sitting to standing after three minutes) and syncope occur later (Case 2).28 Increased mortality among patients with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is thought to be due to QT-interval prolongation leading to arrythmias, reduced awareness of myocardial ischemia, and diminished hemodynamic response in the setting of physiologic stressors, such as infection or ischemia.

The primary risk factor for developing cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy is prolonged hyperglycemia, which includes both poor glucose control, as measured by Hemoglobin A1c, as well as diabetes duration.28 In the population-based Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study, autonomic impairment was present in 54% of people with type 1 diabetes and 73% of those with type 2 diabetes.29 Decreased heart rate variability has also been reported in up to 38% of individuals with pre-diabetes, suggesting that even low levels of hyperglycemia can result in damage to autonomic nerves.30 In addition, among individuals with type 2 diabetes, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as age, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and central obesity, are also associated with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy.31 Therefore, addressing these risk factors, in conjunction with addressing hyperglycemia, is important among people with diabetes to prevent autonomic nervous system damage [KP11].

Diagnosis

The American Diabetes Association recommends screening all patients with existing microvascular complications of diabetes (i.e. DSPN, retinopathy, or nephropathy) for signs and symptoms of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy [KP12].13 As symptoms of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy often occur late in the course of disease, proactive screening for signs, namely elevated resting heart rate and orthostatic hypotension is recommended via a battery of cardiovascular reflex tests.13 Originally proposed by Ewing et al, these noninvasive tests include: heart rate response to Valsalva maneuver, standing up, and deep breathing to assess parasympathetic function as well as blood pressure response to standing up and sustained handgrip to assess sympathetic function (Figure 1 in Case 2).32 Ewing’s battery is considered the gold standard test for cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy diagnosis and facilitates disease staging. Individuals with one positive test result on Ewing’s battery are considered to have possible or early cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy; two abnormal results are definite cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, whereas the presence of orthostatic hypotension denotes severe cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy.33 Given the large number of people with diabetes worldwide, there are concerns about the cost and time required to conduct all the tests in Ewing’s battery.13 Therefore, attempts to reduce the number of tests necessary to screen for cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy are ongoing. While questionnaires have been developed to screen patients for symptoms of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, these have not been widely integrated into clinical care.

Figure 1:

Graphs for two separate patients depicting heart rate response to deep breathing – (A) is for the patient in Case 2, compared to (B) a normal study. This test is an assessment of parasympathetic cardiovagal function. The heart rate increases at the end of inspiration and decreases at the end of expiration. The R-R interval is the distance in milliseconds between successive QRS complexes on a single-lead ECG tracing. A graph of the R-R interval versus time should have a clear sinusoidal shape that mimics the patient’s respiratory rate, as seen in (B), when parasympathetic cardiovagal function is intact. This response is blunted in the patient from Case 2 as seen in (A).

Management

Treatment of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy requires a multifaceted approach to reducing risk factors to prevent disease progression while also addressing symptoms. Lifestyle modification to improve glucose control and reduce insulin resistance is essential. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial and its follow up observational Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study showed that intensive insulin therapy targeting normoglycemia among 1,441 people with type 1 diabetes reduced the incidence of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy by 45%.34 Among people with type 2 diabetes, targeting hyperglycemia may not be enough, however, as interventions targeting multiple risk factors, including hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, may be more effective in this patient population [KP13].35 Surgical weight loss has also been shown to stabilize, but not reverse, cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy progression.36

Among patients with orthostatic hypotension, symptomatic management should also be considered. Treatment of orthostatic hypotension is often challenging and includes nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions. Medication lists should be carefully reviewed and medications that may be contributing to hypotension should be discontinued in conjunction with the patient’s primary provider. Nonpharmacological interventions for orthostatic hypotension include (Table 1): increasing intravascular volume with liberal fluids and salt intake; compression stockings to reduce vascular pooling in the legs; avoiding activities that contribute to vascular dilation, such as warm baths; and behavioral modifications such as making changes to posture slowly to reduce symptoms [KP14]. Pharmacologic interventions include medications such as fludrocortisone and midodrine, and droxidopa. Typical medication doses and adverse effects are provided in Table 1.

Table 1:

Behavioral and pharmacologic interventions for orthostatic hypotension

| Non-pharmacologic interventions | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Pharmacologic interventions | ||

|

Medication and mechanism of

action |

Dosing | Adverse Effects |

| Fludrocortisone Synthetic mineralocorticoid, volume expander by increasing sodium and water reabsorption. |

0.1-0.2 mg, 2-3 times daily | Hypokalemia, supine hypertension, peripheral edema, renal failure. Use cautiously in congestive failure. |

| Midodrine Direct α1-adregergic receptor agonist |

2.5-10 mg, every 3-4 hours. | Severe supine hypertension, piloerection, urinary retention. Do not use within 4 hours of bedtime. Use cautiously in congestive heart failure and chronic renal failure. |

| Droxidopa Synthetic norepinephrine precursor |

100-600 mg three times daily | Headache, supine hypertension, nausea, fatigue. Use cautiously in congestive heart failure and chronic renal failure. |

Case 2

A 60-year-old man presents after a syncopal episode while watching a fourth of July parade. Evaluation in the emergency room after the episode was unremarkable. Though this is the first time that he has lost consciousness, he notes that for the past few years, he has been increasingly “woozy” when getting out of bed to use the bathroom at night. In addition to longstanding diet-controlled type 2 diabetes, he is taking lisinopril for hypertension and atorvastatin for hyperlipidemia.

His neurologic examination is generally unremarkable except for decreased sensation to pinprick on his feet. He underwent testing for cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in the office with a portion of his test results shown in Figure 1. Resting heart rate was 105 beats per minute. Blood pressure while lying down was 120/75 and 90/50 after standing for 3 minutes.

Comment:

Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes is often asymptomatic in its early stages and symptoms will only develop late in the course of disease. The patient underwent Ewing’s battery in the office. Figure 1 displays the R-R interval during deep breathing for our patient (A) and normal study (B) for comparison. The R-R interval is a measure of the time elapsed between two successive R waves of the QRS signal on the electrocardiogram. Normal heart rate variation can be greater than 10 beats per minute, increasing with inspiration and decreasing with expiration. Therefore, a graph of the R-R interval versus time would be expected to take a sinusoidal shape that mirrors the pattern of breathing. The patient has an abnormal resting heart rate as well as blunted heart rate response to deep breathing. Combined, these findings support a diagnosis of definite cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. Management should consist of working with his primary care provider to stop medications that could be contributing to his symptoms, such as lisinopril, treating risk factors, including his diabetes, and anticipatory guidance. Given that his syncopal episode occurred in July, recommending caution and avoid standing for prolonged periods in the heat, is warranted. Of note, he met criteria for orthostatic hypotension today in clinic. This is consistent with his description of feeling “woozy” when going from a lying to standing position and he should consider nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions to improve his blood pressure when standing.

Diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy

Also known as diabetic amyotrophy or Bruns-Garland syndrome, diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy occurs most commonly in individuals with type 2 diabetes. It is uncommon, with an prevalence of 2.79 cases per 100,000 people over five years in Olmstead County, Minnesota.37 Although rare, diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus may be more common than other inflammatory neuropathies , such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, brachial plexus neuropathy (Parsonage Turner Syndrome) or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy.37 Unlike other neuropathies, patients who experience lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy often have fairly well controlled diabetes, with a median hemoglobin A1C of 7.5% in one study.38 While the etiology of diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy is unknown, it often occurs in the setting of recent weight loss, typically more than 10 pounds.38 No other predictors have been identified, however, a recent study of patients with lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy and age/sex-matched controls suggest that, in addition to diabetes, risk factors for lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy may include a prior history of stroke, elevated body mass index, or a comorbid autoimmune disorder, such as thyroiditis, inflammatory bowel disease, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, or psoriasis.39

Patients diagnosed with diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy endorse acute, severe pain in the hip or thigh described as burning, tightness, or allodynia. They are often able to name the exact day that their symptoms began. This is followed by leg weakness that is initially focal then generalizes to the entire leg. Leg weakness can progress over months [KP15]. Pain often improves first so that, depending on how long it takes to seek care, patients may only have asymmetric leg weakness, muscle atrophy, and absent knee and ankle reflexes. Sensory loss is not typically seen on exam, though patients may have a concomitant distal symmetric polyneuropathy due to their diabetes.

Significant morbidity occurs with diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy. Initial pain can be debilitating, and patients often require adaptive devices, such as wheelchairs or walkers for ambulation. Over time, most report improvements in pain and strength, though recovery often requires up to two years and few return to normal. While this is often a unilateral, monophasic acute neuropathy, patients may have a subsequent episode on the opposite leg.38 Cervical radiculoplexus neuropathy and thoracic radiculopathy are separate entities that can also occur concomitantly with lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy or independently and have a similar presentation and natural history.40,41 Focal microvasculitis of individual nerves is likely the underlying mechanism for diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy.

Diagnosis

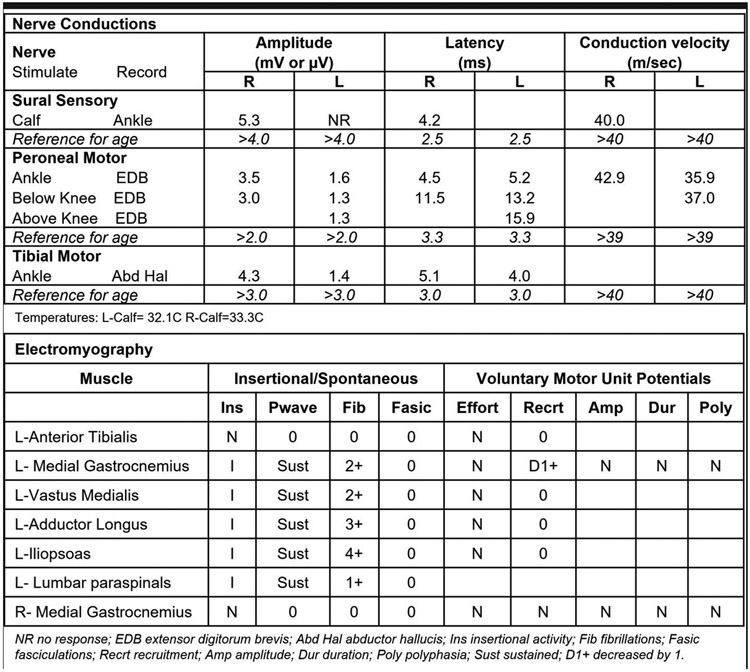

Due to the severity of symptoms, most patients with diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy seek care. Diagnosis is largely based on clinical history and exam. Laboratory studies are generally normal, however, biopsy of an involved nerve can show focal or multifocal nerve fiber loss, perivascular mononuclear inflammation and neovascularization in the epineurium, segmental demyelination, and axonal degeneration.38 Cerebrospinal fluid studies performed on patients with diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy are notable for elevated protein, which supports nerve root involvement in this disorder. Nerve conduction studies will often show reduced or absent compound muscle action potentials (CMAP) in the tibial and peroneal nerve as well as decreased sensory nerve action potentials (SNAP) in the sural nerve. There is usually asymmetry in nerve conduction studies between the affected and unaffected leg. Needle examination will show widespread increased insertional activity (fibrillations and positive sharp-waves) and motor unit action potential changes that cannot be localized to one nerve or root in the affected limb (Figure 2) [KP16]. An MRI of the lower spine is generally unrevealing, however, a magnetic resonance neurography (MRN) may reveal abnormalities. On MRN, signals for fat and blood are suppressed on T2 images so that nerve appears brighter than surrounding tissue.42,43 This approach can be used to examine single nerves or the plexus, though may not be available at all imaging centers. MRI of the plexus will often show increased T2 signal intensity and thickening of nerve roots (Figure 3).44 It can also be used to assess the terminal branches of nerves for individual muscle involvement. Edema, atrophy and, in late stages, fatty infiltration can be seen in involved muscles.45 At this time, neither electrodiagnostic studies nor MRN are used to guide treatment, however, they are able to confirm localization and shed light on the extent of nerve involvement which may inform discussions with patients and their families. If a patient presents to clinical care early in the disease course prior to improvement in weakness, MRI of the lumbosacral plexus is needed to evaluate for other causes of a radiculoplexus neuropathy such as cancer and other infiltrative conditions.

Figure 2:

Nerve conduction studies show decreased CMAPs in the left tibial and peroneal motor nerves as well as an absent sural sensory response. There is increased positive sharpwaves and fibrillations in muscles in the left leg with absent voluntary motor unit action potentials in muscles innervated by the peroneal, tibial, obturator, and femoral nerves. There is asymmetry between the sides. These findings are typical for diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy.

Figure 3:

MRI without contrast of the pelvis in a patient with asymmetric leg weakness. Asymmetric increased T2 signal and thickening of the left lumbosacral plexus coronal STIR image (A) and thickening of the left femoral nerve on the axial FLAIR (B). In the appropriate clinical context, these findings are consistent with a diagnosis of diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy.

Management

Currently, no treatment has proven effective for diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy. While inflammation of blood vessels likely plays a substantial role, there is limited data to support the use of immunotherapy in diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy [KP17].46 A multicenter double-blind clinical trial of IV methylprednisolone showed no significant difference in functional outcomes between steroids and placebo, though the authors report that delayed timing of treatment initiation may have played a role.47 Pain was improved in those receiving steroids; therefore, IV steroids may be indicated early in the course if patients have refractory pain. Earlier diagnosis, which often requires referral to a neurologist, may facilitate better treatment of diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy as well as improved long-term outcomes. However, the use of steroids in patients with diabetes requires careful care coordination with the patient’s primary provider or endocrinologist. Therefore, until effective treatments are identified, management should focus on pain control and providing adaptive devices, such as wheelchairs or ankle foot orthoses (AFOs), as needed, to improve mobility.

Treatment-Induced Neuropathy of Diabetes

Treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes develops acutely in patients who have rapid improvement in glycemic control after a period of prolonged hyperglycemia. Within eight weeks of a significant change in Hemoglobin A1C, patients experience sudden onset of severe, burning or shock-like pain that can be length-dependent or diffuse [KP18]. Allodynia and hyperalgesia are often present as are autonomic symptoms, including orthostatic hypotension, postprandial fullness, erectile dysfunction, and hyperhidrosis (Case 3).48 The etiology of this condition is thought to be due to damage to small nerve fibers. Existing theories suggest that the mechanism of disease may be secondary to a relative period of hypoglycemia leading to inadequate energy production and nerve damage, whereas another theory suggests that change in glycemic state may lead to an increase in proinflammatory cytokines. Regardless, electrodiagnostic studies in these individuals are often normal which suggests that large nerve fibers are not involved.

Treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes is more common than previously thought. A retrospective chart review of patients presenting for evaluation of possible diabetic neuropathy, 10.9% met criteria for treatment-induced diabetic neuropathy.48 This condition is perhaps best characterized as an iatrogenic complication of diabetes management as the magnitude and rate of Hemoglobin A1C change is directly proportional to the likelihood of symptom onset. Gibbons et al found that individuals who have a decrease in Hemoglobin A1C of 2-3% points over 3 months had a 20% absolute risk of developing treatment-induced neuropathy, whereas those with a decrease of >4% points had an absolute risk of greater than 80%.48 Individuals with a greater change in Hemoglobin A1C were also more likely to report a larger area of body involvement and more severe pain.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of treatment-induced neuropathy is based on clinical history and review of the patient’s laboratory results. Graphing the results of Hemoglobin A1C over many months often reveals the diagnosis without the need for further testing. For patients from other health systems, acquiring past Hemoglobin A1C levels is essential. If typical symptoms start within the time period of a 2-3% drop in Hemoglobin A1C, then the diagnosis is clear. If the patient reports autonomic symptoms, formal autonomic function testing could be considered, though this is unlikely to significantly change management. Screening for retinopathy and nephropathy, is essential as patients with treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes often experience progression of other diabetic microvascular complications [KP19].

Management

Management of treatment-induced neuropathy is focused on preventing neuropathy progression, symptom management, and preventing recurrence. Case reports suggest that patients with treatment-induced neuropathy often improve with stable glucose control. However, patients should be made aware that neuropathy may not completely resolve. Further, labile glycemic control may result in symptom progression and liberalizing blood sugar control is not recommended [KP20]. To minimize this risk, patient and, if needed, provider education is warranted. Pain management is essential in patients with treatment-induced neuropathy and should be maximized. As in DSPN, neuropathic pain medications include serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentinoids, and sodium channel blockers. Pain levels should be regularly evaluated as two and even three agents may be necessary for control in these patients. However, tricyclic antidepressants should be used cautiously as they may worsen orthostatic symptoms. Preventing recurrence is essential as patients with recurrent treatment-induced neuropathy have an escalation of morbidity including worsening sensory symptoms, motor involvement, and retinal and kidney damage.49

Even more important than identifying and treating patients with treatment-induced neuropathy is the primary prevention of this highly morbid condition [KP21]. Primary care providers and endocrinologists need to be aware of this condition and the predictable harms of fast drops Hemoglobin A1C. Neurologists need to help educate other providers since neurologists are more likely to recognize this condition and understand the underlying cause. Interventions to increase provider awareness are needed to prevent this underrecognized condition.

Case 3

A 30-year-man presents to the electrodiagnostic lab for workup of diffuse shock-like pain. He was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes as a teenager and historically had poor glycemic control. However, he notes that he recently got engaged and, for the past three months, has been seeking regular medical care to “turn over a new leaf”. Three weeks ago, he developed new burning and shock like pain in his hands, feet, and abdomen. He had no symptoms of neuropathy prior to this.

On exam, he is wearing a baggy sweatshirt, sweatpants, and sandals despite the cold weather. On examination, he has normal strength and reflexes. Vibration and proprioception were also normal. He endorses severe pain to pinprick in his hands and feet to pinprick. Similarly, he endorses pain across his abdomen that does not localize to one dermatome.

A review of his recent laboratory testing reveals that his Hemoglobin A1C was historically between 14 and 16 percentage points, but most recently was 9.

Comment:

Treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes is seen in patients who are chronically hyperglycemic and then experience a rapid improvement in glycemic control. The severity and extent of symptoms is driven largely by the magnitude and rate of glucose correction. In this case, the patient’s severe symptoms were secondary to the very rapid change in his Hemoglobin A1C level, which decreased by up to 7 percentage points over three months. Treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes is best localized to the small fiber nerves and examination of large fiber nerves are often normal. Therefore, electrodiagnostic testing in this case is unlikely to add to diagnosis or management. Therefore, next steps should focus on symptoms – glycemic control should be stabilized (i.e., no further decreases in Hemoglobin A1C until symptoms begin to improve), and pain control should be initiated. The patient should also undergo assessment for retinopathy and nephropathy as these have both been reported in patients with treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes. Prognosis is quite good if recurrent episodes of abrupt drop in Hemoglobin A1C are avoided.

Conclusions

Diabetes is a burgeoning worldwide epidemic. Neuropathy is common in diabetes and can present sub-acutely, in the case of diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy, or develop insidiously as in DSPN and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. As the burden of diabetes continues to grow, even uncommon neuropathies will be present more frequently and clinicians must be adept at identifying these conditions to facilitate earlier intervention. In all cases, a careful history and neurologic exam is essential for diagnosis. Ancillary studies can supplement a neurologic history and exam, particularly if there is concern for an alternative diagnosis. However, these tests may not be necessary for diagnosis in all cases. Unfortunately, disease-modifying treatments for diabetic neuropathies are limited and, as a result, the focus should continue to be neuropathy prevention and symptom management including pain treatment.

Key Points.

The prevalence of diabetic neuropathies will continue to grow as the burden of diabetes increases worldwide and, until disease-modifying treatments are identified, management is reliant on addressing risk factors that increase the risk of neuropathy and neuropathy-related complications.

Neuropathy in diabetes can present with length-dependent, autonomic, focal, or generalized signs and symptoms.

Distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DSPN) is the most common neuropathy in diabetes and presents with length-dependent numbness, tingling and pain. Neurologic exam should include assessment of both large and small fiber function as small fiber nerves are often affected first in DSPN.

Any form of chronically-elevated blood glucose has been associated with the development of DSPN, including pre-diabetes.

Screening for comorbid medical conditions among people with neuropathy is essential. In addition to diabetes duration and severity, metabolic syndrome components, in particular central obesity, are also associated with an increased risk of DSPN among people with type 2 diabetes.

While glycemic control alone prevents the development of DSPN among people with type 1 diabetes, it is insufficient among people with type 2 diabetes. Therefore, multiple interventions targeting metabolic syndrome components are necessary. Exercise has bene associated with improvement in patient-reported symptoms.

DSPN management is focused on risk factor reduction and pain management. AAN guidelines recommend four classes of medications for neuropathic pain management. Opioids are not recommended as there are little data to support their long-term effectiveness and the emerging downsides include death, overdose, abuse, addiction amongst many others.

Setting reasonable expectations and regular assessment of a patient’s pain level are essential to titrate medications for neuropathic pain control.

Screening for cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetic patients is critical as those with cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy are more than two times more likely to die than those without cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy.

Symptoms of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy often present late as dizziness orthostatic hypotension, and syncope.

Risk factors for developing cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy include prolonged hyperglycemia, but also include traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as age, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and central obesity.

Patients with a history of microvascular complications of diabetes, such as DSPN, should be screened for signs and symptoms of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy. These tests, known as Ewing’s battery, can often be completed in the office with an electrocardiogram and blood pressure cuff.

Among people with type 2 diabetes, targeting traditional cardiovascular risk factors as well as hyperglycemia is essential to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy.

Symptomatic management of cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, particularly among patients with orthostatic hypotension, is critical. A multifaceted approach that includes stopping offending medications, increasing fluid and salt intake, and behavioral modifications is most effective.

Patients with lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy endorse sudden-onset pain in the hip or thigh followed by focal leg weakness that becomes generalized over time. Symptoms slowly improve but can take up to two years and few patients report returning to their prior neurologic baseline.

Nerve conduction studies in a patient with diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy will show reduced motor and sensory nerve action potentials as well as increased insertional activity in muscles that cannot be localized to one nerve or nerve root. Findings will be asymmetric between legs.

There are currently no effective treatments for diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy and management is focused on adaptive devices to improve quality of life.

Treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes should be considered in an individual with diabetes who presents with acute or subacute pain in the setting of a rapid improvement in glycemic control. Symptoms are best localized to the small fiber nerves and present with burning, shock-like pain, allodynia, and hyperalgesia.

Patients with treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes should undergo screening for other microvascular complications as they often experience progression of retinopathy and nephropathy that needs to be appropriately monitored.

Management of treatment-induced neuropathy should focus on preventing neuropathy progression by stabilizing labile glycemic control, symptom management via neuropathic pain management, and preventing recurrence. Patients should be counseled that symptoms may improve but may not completely resolve.

Prevention of treatment-induced neuropathy in diabetes by educating primary care providers and endocrinologists to avoid fast drops in hemoglobin A1C is essential as this is a highly morbid neuropathy. Among patients with existing treatment-induced neuropathy, coordination with the patient’s primary care provider or endocrinologist is essential to prevent neuropathy progression.

Disclosures:

Dr. Elafros acknowledges funding from the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (5R25NS089450), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR002240), and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (P30-DK-02926 and P30-DK089503). Dr. Callaghan acknowledges funding from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK115687) and JDRF (5COE-2019-861-S-B). Dr Callaghan consults for DynaMed, performs medical legal consultations including consultations for the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, and receives research support from the American Academy of Neurology.

Footnotes

Unlabeled use of products/investigational use disclosure: Drs Elafros and Callaghan report no disclosures.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas: International Diabetes Federation, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gylfadottir SS, Christensen DH, Nicolaisen SK, et al. Diabetic polyneuropathy and pain, prevalence, and patient characteristics: a cross-sectional questionnaire study of 5,514 patients with recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Pain 2020; 161(3): 574–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordois A, Scuffham P, Shearer A, Oglesby A, Tobian JA. The health care costs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the US. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(6): 1790–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callaghan BC, Price RS, Feldman EL. Distal Symmetric Polyneuropathy: A Review. JAMA 2015; 314(20): 2172–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbott CA, Malik RA, van Ross ER, Kulkarni J, Boulton AJ. Prevalence and characteristics of painful diabetic neuropathy in a large community-based diabetic population in the U.K. Diabetes Care 2011; 34(10): 2220–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun J, Wang Y, Zhang X, Zhu S, He H. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in patients with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes 2020; 14(5): 435–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stino AM, Smith AG. Peripheral neuropathy in prediabetes and the metabolic syndrome. J Diabetes Investig 2017; 8(5): 646–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen DH, Knudsen ST, Gylfadottir SS, et al. Metabolic Factors, Lifestyle Habits, and Possible Polyneuropathy in Early Type 2 Diabetes: A Nationwide Study of 5,249 Patients in the Danish Centre for Strategic Research in Type 2 Diabetes (DD2) Cohort. Diabetes Care 2020; 43(6): 1266–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaiswal M, Divers J, Dabelea D, et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy in Youth With Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care 2017; 40(9): 1226–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hicks CW, Wang D, Windham BG, Matsushita K, Selvin E. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy defined by monoflament insensitivity in middle-aged and older adults in two US cohorts. Nature 2021; 11: 19159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callaghan BC, Gao L, Li Y, et al. Diabetes and obesity are the main metabolic drivers of peripheral neuropathy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2018; 5(4): 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callaghan BC, Xia R, Banerjee M, et al. Metabolic Syndrome Components Are Associated With Symptomatic Polyneuropathy Independent of Glycemic Status. Diabetes Care 2016; 39(5): 801–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJ, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2017; 40(1): 136–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callaghan BC, Xia R, Reynolds E, et al. Better diagnostic accuracy of neuropathy in obesity: A new challenge for neurologists. Clin Neurophysiol 2018; 129(3): 654–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callaghan BC, Little AA, Feldman EL, Hughes RA. Enhanced glucose control for preventing and treating diabetic neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; (6): CD007543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Look ARG. Effects of a long-term lifestyle modification programme on peripheral neuropathy in overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes: the Look AHEAD study. Diabetologia 2017; 60(6): 980–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaghan BC, Reynolds EL, Banerjee M, et al. Dietary weight loss in people with severe obesity stabilizes neuropathy and improves symptomatology. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2021; 29(12): 2108–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kluding PM, Pasnoor M, Singh R, et al. The effect of exercise on neuropathic symptoms, nerve function, and cutaneous innervation in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications 2012; 26(5): 424–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen TS, Karlsson P, Gylfadottir SS, et al. Painful and non-painful diabetic neuropathy, diagnostic challenges and implications for future management. Brain 2021; 144(6): 1632–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daousi C, MacFarlane IA, Woodward A, Nurmikko TJ, Bundred PE, Benbow SJ. Chronic painful peripheral neuropathy in an urban community: a controlled comparison of people with and without diabetes. Diabet Med 2004; 21(9): 976–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price R, Smith D, Franklin G, et al. Oral and Topical Treatment of Painful Diabetic Polyneuropathy: Practice Guideline Update Summary: Report of the AAN Guideline Subcommittee. Neurology 2022; 98(1): 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tesfaye S, Sloan G, Petrie J, et al. Comparison of amitriptyline supplemented with pregabalin, pregabalin supplemented with amitriptyline, and duloxetine supplemented with pregabalin for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (OPTION-DM): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised crossover trial. Lancet 2022; 400(10353): 680–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Laake-Geelen CCM, Smeets R, Quadflieg S, Kleijnen J, Verbunt JA. The effect of exercise therapy combined with psychological therapy on physical activity and quality of life in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy: a systematic review. Scand J Pain 2019; 19(3): 433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen EA, Stauss TG, Scowcroft JA, et al. Effect of High-frequency (10-kHz) Spinal Cord Stimulation in Patients With Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol 2021; 78(6): 687–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chowdhury M, Nevitt S, Eleftheriadou A, et al. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2021; 9(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forsen A, Kangro M, Sterner G, et al. A 14-year prospective study of autonomic nerve function in Type 1 diabetic patients: association with nephropathy. Diabet Med 2004; 21(8): 852–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen JA, Estacio RO, Lundgren RA, Esler AL, Schrier RW. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy is associated with an increased incidence of strokes. Auton Neurosci 2003; 108(1-2): 73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duque A, Mediano MFF, De Lorenzo A, Rodrigues LF Jr. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: Pathophysiology, clinical assessment and implications. World J Diabetes 2021; 12(6): 855–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lozeron P, Nahum L, Lacroix C, Ropert A, Guglielmi JM, Said G. Symptomatic diabetic and non-diabetic neuropathies in a series of 100 diabetic patients. J Neurol 2002; 249(5): 569–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eleftheriadou A, Williams S, Nevitt S, et al. The prevalence of cardiac autonomic neuropathy in prediabetes: a systematic review. Diabetologia 2021; 64(2): 288–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang Y, Shah H, Bueno Junior CR, et al. Intensive Risk Factor Management and Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy in Type 2 Diabetes: The ACCORD Trial. Diabetes Care 2021; 44(1): 164–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ewing DJ, Martyn CN, Young RJ, Clarke BF. The value of cardiovascular autonomic function tests: 10 years experience in diabetes. Diabetes Care 1985; 8(5): 491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spallone V. Update on the Impact, Diagnosis and Management of Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy in Diabetes: What Is Defined, What Is New, and What Is Unmet. Diabetes Metab J 2019; 43(1): 3–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin CL, Albers JW, Pop-Busui R, Group DER. Neuropathy and related findings in the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(1): 31–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, Jensen GV, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2003; 348(5): 383–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reynolds E, Wantanabe M, Elafros MA, Feldman EL, Callaghan B. 1158-P: The Effect of Surgical Weight Loss on Diabetic Complications in the Severely Obese. Diabetes 2022; 71: 1158–P. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ng PS, Dyck PJ, Laughlin RS, Thapa P, Pinto MV, Dyck PJB. Lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy: Incidence and the association with diabetes mellitus. Neurology 2019; 92(11): e1188–e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyck PJ, Norell JE, Dyck PJ. Microvasculitis and ischemia in diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy. Neurology 1999; 53(9): 2113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinto MV, Ng PS, Laughlin RS, et al. Risk factors for lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2022; 65(5): 593–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell DSH. Diabetic Mononeuropathies and Diabetic Amyotrophy. Diabetes Ther 2022; 13(10): 1715–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Massie R, Mauermann ML, Staff NP, et al. Diabetic cervical radiculoplexus neuropathy: a distinct syndrome expanding the spectrum of diabetic radiculoplexus neuropathies. Brain 2012; 135(Pt 10): 3074–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Filler AG, Howe FA, Hayes CE, et al. Magnetic resonance neurography. Lancet 1993; 341(8846): 659–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hlis R, Poh F, Bryarly M, Xi Y, Chhabra A. Quantitative assessment of diabetic amyotrophy using magnetic resonance neurography-a case-control analysis. Eur Radiol 2019; 29(11): 5910–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCormack EP, Alam M, Erickson NJ, Cherrick AA, Powell E, Sherman JH. Use of MRI in diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy: case report and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2018; 160(11): 2225–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ku V, Cox C, Mikeska A, MacKay B. Magnetic Resonance Neurography for Evaluation of Peripheral Nerves. J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj 2021; 16(1): e17–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan YC, Lo YL, Chan ES. Immunotherapy for diabetic amyotrophy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 7: CD006521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tracy JA, Engelstad JK, Dyck PJ. Microvasculitis in diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2009; 11(1): 44–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gibbons CH, Freeman R. Treatment-induced neuropathy of diabetes: an acute, iatrogenic complication of diabetes. Brain 2015; 138(Pt 1): 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibbons CH. Treatment induced neuropathy of diabetes-Long term implications in type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2017; 31(4): 715–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]