Abstract

Background and aims

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) is validated for risk prediction among middle-aged adults, but there is limited research exploring implications of CAC among older adults. We used data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study to evaluate the association of CAC with domains of healthy and unhealthy aging in adults aged ≥75years.

Methods

We included 2,290 participants aged ≥75years free of known coronary heart disease who underwent CAC scoring at study visit 7. We examined the cross-sectional association of CAC=0, 1–999(reference), and ≥1000 with seven domains of aging: cognitive function, hearing, ankle-brachial index (ABI), pulse-wave velocity (PWV), forced vital capacity (FVC), physical functioning, and grip strength.

Results

The mean age was 80.5±4.3years, 38·6% male, and 77·7% White. 10·3% had CAC=0 and 19.2% had CAC≥1000. Individuals with CAC=0 had the lowest while those with CAC≥1000 had the highest proportion with dementia(2% vs 8%), hearing impairment(46% vs 67%), low ABI(3% vs 18%), high PWV(27% vs 41%), reduced FVC(34% vs 42%), impaired grip strength(66% vs 74%), and mean composite abnormal aging score(2.6 vs 3.7). Participants with CAC=0 were less likely to have abnormal ABI(aOR:0.15, 95%CI:0.07–0.34), high PWV(aOR:0.57, 95%CI:0.41–0.80), and reduced FVC(aOR:0.69, 95%CI:0.50–0.96). Conversely, participants with CAC≥1000 were more likely to have low ABI(aOR:1.74, 95%CI:1.27–2.39), high PWV(aOR:1.52, 95%CI:1.15–2.00), impaired physical functioning(aOR:1.35, 95%CI:1.05–1.73), and impaired grip strength(aOR:1.46, 95%CI:1.08–1.99).

Conclusion

Our findings highlight CAC as a simple measure broadly associated with biological aging, with clinical and research implications for estimating the physical and physiological aging trajectory of older individuals.

1. INTRODUCTION

Increasing age is a well-established risk factor for decline in physiologic and functional status that accounts for much of the variation seen in the prevalence and incidence of most chronic clinical conditions, as well as the associated outcomes.1 However, among individuals with the same chronologic age, widely varying phenotypes are observed across several domains of biologic function, and trajectories of the aging process can be very dissimilar.1 Healthy aging is a process that starts early in life and is generally defined as preserved physical, social, and mental well-being through life transitions.2 It largely depends on two major components- an innate capacity comprised of the interplay between genetics, risk factor exposure, and clinical conditions; and environmental exposure.3,4

The aging process is marked by cellular senescence via several underlying biological mechanisms, which have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.1,5,6 Coronary artery calcium (CAC) is widely validated marker of atherosclerosis that has been found to strongly predict coronary heart disease events, cardiovascular disease events, and all-cause mortality.7,8 CAC scores of 0 have been proven to have high negative predictive value for cardiovascular events and mortality, particularly among middle-aged adults.9,10 Importantly, CAC=0 is also associated with low risk of non-cardiovascular chronic diseases,11 and represents some potential as a marker of overall healthy aging. Conversely, CAC scores ≥1000 have been associated with substantially increased risk of cardiovascular disease, non-cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality,12,13 warranting aggressive preventive therapy.14 As such, CAC ≥1000 could be considered an unhealthy coronary aging phenotype.

Although some amount of CAC is common with aging, 10–20% of individuals live nearly their whole lives without developing any CAC.15 Notably, a study done among the Tsimane people of Bolivia -- a group with a hunter-gatherer diet, high physical activity, minimal traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and minimal exposure to air pollution, radiation, etc -- showed that among adults 75 years and older, the majority (65%) had no CAC.16 As CAC scores of 0 are associated with significantly reduced incidence of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular events,9,17 exploring the breadth and correlates of this phenotype among older adults will add value to further defining healthy cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular aging.

Evaluating extremes of CAC phenotypes is especially important among older adults, for whom there is limited information on the implications of zero and low CAC scores as well as elevated scores. With an average life expectancy of approximately 79 years in the U.S., 16.5% of the population is comprised of older adults aged >65 years - a percentage projected to reach 22% by 2050.18,19 While much of the research findings on imaging-derived vascular aging done in adults are extrapolated to this demographic group, they have unique characteristics and clinical profiles, and thus research focused on this age group is necessary.

In line with the goals of the United Nations Research Agenda on Ageing for the 21st century to prioritize research into the healthy determinants of aging,20 more research is required to define aging phenotypes in adults >75 years of age. Thus, we leveraged data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study to assess the degree to which CAC=0 and CAC≥1000 correlate with domains of aging, including measures of cognitive and physical function, as well as other physiologic factors such as pulmonary function and vascular morphology.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Study population

The ARIC study is an ongoing study of 15,792 individuals aged 45–64 years, enrolled between 1987 and 1989 across four communities in the United States- Jackson, Mississippi; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Washington County, Maryland; and suburban Minneapolis, Minnesota. Participants have been followed prospectively since enrollment, with extensive examination done over the course of several visits (1987–1989, 1990–1992, 1993–1995, 1996–1998, 2011–2013, 2016–2017, 2018–2019).21 The ARIC CAC ancillary study, which measured CAC among participants with no history of coronary heart disease, was completed between February 2018- December 2019 (visit 7). Informed consent was obtained from participants at each visit, and Institutional Review Boards at each center approved the research protocol.16

For the present analysis, we included participants aged 75 years and older with available information on their CAC score, excluding those with a history of coronary heart disease per the ARIC CAC sampling protocol, making our total sample size 2,290. Data was nearly exclusively from visit 7 of the ARIC study, however, two variables -pulse wave velocity [PWV] and ankle-brachial index [ABI], were collected in visit 6 (2016–2017).

2.2. CAC measurement

CAC was measured using multi-detector computed tomography scanners by trained technicians, and the cardiac CT scans were read centrally. Calcification was identified as lesions with attenuation of 130 Hounsfield units or greater and area of 1mm2 or greater in each slice. CAC was quantified using the Agatston score.

2.3. Aging indices

Several indices were evaluated based on their known correlation with aging. Supplemental table S1 shows how the various aging indices were defined and categorized.

Cognitive function was measured using participants’ performance on a comprehensive neuropsychological battery and an informant interview in a subset of participants. The cognitive assessment included several tests such as word recall task, digit symbol substitution from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R), a letter fluency task, and the mini-mental state examination. A detailed description of how ARIC participants were classified as having normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, or dementia has previously been published.22,23 For this study, we categorized cognitive function as dementia vs normal/mild cognitive impairment.

Hearing loss was measured by a trained technician using pure tone audiometry and categorized as no hearing loss (pure tone average [PTA] of thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4kHz in the better hearing ear <25 dB) vs some hearing impairment (PTA ≥25 dB).24

Indices of vessel condition included ABI and carotid-femoral PWV. ABI measurements were taken according to a standardized protocol.25 Blood pressures of the upper and lower extremities were measured using a Dinamap automated oscillometric device. ABI was then calculated and categorized as normal (≥1.0) or low (<1.0). PWV was measured using the VP-1000 Plus system (Omron, Kyoto, Japan), as previously described,26 and was dichotomized around the median value for our sample (1210.5 m/s).

Pulmonary function was measured on spirometry. Forced vital capacity (FVC) was dichotomized around the median for sex (females: 2.5L; males: 3.8L).

Physical function was assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) which was conducted by trained staff.27 The SPPB consisted of three tests - a chair stand test, standing balance, and the gait speed test. Each test was scored 0–4, with 4 being the best performance. The SPPB total score is the sum of the 3 test scores, ranging from 0 to 12, with a higher score indicating better physical function.27,28 We categorized physical function as normal for scores of 10–12, and impaired for scores <10. Grip strength, in kilograms, was measured in the participants’ preferred or best hand using an adjustable hydraulic grip strength dynamometer.29,30 We dichotomized grip strength around the top quartile for grip mean strength by sex and body mass index (BMI) categories.31

2.4. Demographic variables

Age, sex, and race were self-reported. Education was categorized as less than high school, completed high school, and at least some college. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Smoking status was categorized as never, former, and current smoker. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90mmHg or the use of anti-hypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined as glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) >6.5%, fasting blood glucose ≥126mg/dl, non-fasting glucose ≥ 200mg/dl, self-report of a prior diagnosis, or using diabetic medication. Lipid parameters included high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride concentration. Statin use was self-reported. Medication containers were brought in by participants for verification of their use over the preceding 2 weeks.

2.5. Statistical analyses

The baseline characteristics of the participants were stratified by CAC burden categories (0, 1–999, and ≥1000 Agatston Units) and summarized using proportions and means for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Differences were tested using the Chi-squared test for categorical variables and the one-way analysis of variance test for continuous variables. We then calculated the prevalence of each abnormal aging domain, first for the entire study sample and then by CAC burden categories. Data missingness for each domain is noted within the tables.

Our primary analysis made use of a composite aging score. To preserve statistical power, we used multiple imputations in the case of limited missing aging domain data. First, using multivariable models adjusting for baseline characteristics including age, sex, race, and ASCVD risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, dyslipidemia, and family history of premature CHD), we imputed the missing data for the aging domains (Supplementary Table S2). Then, we generated a composite score for each participant based on the number of abnormal aging domains present. Since seven aging domains were assessed, scores ranged from 0–7 (0 the ideal score, 7 representing the most advanced aging). We then estimated the mean composite aging score for each CAC burden category and tested differences using multivariable linear regression models.

Using logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, and study center, we then obtained the odds ratios for the association of CAC with each individual aging domain. These analyses of individual domains used a complete case approach without imputation. We did not include traditional risk factors in these models as we were primarily interested in exploring CAC as a marker of the pre-specified aging domains regardless of comorbidities that are often rife in our population of interest.

We also explored other CAC categorizations. As a sensitivity analysis, to increase the population in the ideal CAC category, we used CAC <10, CAC 10–999, and CAC ≥1000 AU as CAC burden categories. As an additional analysis, to expand our reference population, we used a 5-category CAC categorization with CAC=100–399 as reference (0, 1–99, 100–399, 400–999, ≥1000 AU).

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A 2-sided alpha (α) level of <0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics and prevalence of CAC among study participants

The mean age of participants in our study sample was 80.5 years (SD:4.3), 38.6% were male, and 77.7% of White race. In total, 10.3% had CAC scores of 0, and 19.2% had CAC ≥1000. Comparing CAC categories of 0, 1–999, and ≥1000, a larger proportion of participants with CAC scores of 0 were female, of Black race, had some college education, and were never smokers, while CAC ≥1000 had a larger proportion of people who were males, of White race, former smokers, with hypertension, diabetes, and on statin medication (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of study population

| Characteristics | Total n=2,290 (%) | CAC=0 AU n=237 (%) | CAC 1–999 AU n=1,613 (%) | CAC ≥1000 AU n=440 (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 80.5 (±4.3) | 78.9 (±3.3) | 80.4 (±4.3) | 81.6 (±4.5) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 884 (38.6) | 41 (17.3) | 558 (34.6) | 285 (64.8) | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.020 | ||||

| Asian | 7 (0.31) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Black | 503 (22.0) | 71 (30.0) | 347 (21.5) | 85 (19.3) | |

| White | 1,780 (77.7) | 166 (70.0) | 1,261 (78.2) | 353 (80.2) | |

| Education | 0.015 | ||||

| <High school | 232 (10.1) | 15 (6.4) | 174 (10.8) | 43 (9.8) | |

| Complete | 934 (40.9) | 82 (34.8) | 675 (41.9) | 177 (40.4) | |

| ≥Some college | 1,120 (49.0) | 139 (58.9) | 763 (47.3) | 218 (49.8) | |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | ||||

| Current | 108 (5.2) | 8 (3.9) | 73 (5.0) | 27 (6.7) | |

| Former | 1,179 (57.2) | 109 (52.9) | 804 (55.2) | 266 (66.3) | |

| Never | 776 (37.6) | 89 (43.2) | 579 (39.8) | 108 (26.9) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.1 (±5.4) | 27.4 (±5.7) | 28.1 (±5.3) | 28.4 (±5.5) | 0.043 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 134.9 (±19.1) | 135.2 (±19.2) | 135.3 (±18.8) | 133.5 (±20.0) | 0.227 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 66.6 (±10.9) | 67.6 (±10.7) | 66.8 (±10.7) | 65.0 (±11.6) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 1,755 (77.6) | 151 (64.0) | 1,242 (78.1) | 362 (83.0) | <0.001 |

| Anti-hypertensive medication | 1,728 (75.6) | 141 (59.5) | 1,215 (75.5) | 372 (84.7) | <0.001 |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 179.2 (±37.2) | 189.0 (±38.7) | 181.1 (±39.8) | 166.8 (±37.2) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 51.3 (±14.1) | 56.7 (±13.6) | 51.5 (±14.0) | 47.9 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 105.5 (±33.1) | 112.5 (±32.8) | 106.8 (±33.5) | 96.6 (±30.0) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 113.1 (±60.7) | 99.5 (±46.0) | 114.7 (±61.3) | 114.3 (±64.8) | <0.001 |

| Statins | 1,097 (48.7) | 79 (34.1) | 743 (46.8) | 275 (63.4) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 710 (31.8) | 48 (21.1) | 486 (30.8) | 176 (40.9) | <0.001 |

3.2. Prevalence of abnormal aging indices

A relatively smaller proportion of participants with CAC=0 had dementia (2.1%), hearing loss (45.6%), low ABI (2.5%), high PWV (26.6%), reduced FVC (33.7%), and impaired grip strength (65.8%). Conversely, the CAC≥1000 group had more participants with dementia (8.0%), hearing loss (67.3%), low ABI (17.5%), high PWV (40.9%), reduced FVC (41.8%), and impaired grip strength (74.3%). Physical function did not differ significantly across groups (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2:

Distribution of the Ageing Domains by CAC Score

| Total n=2,290 (%) | CAC=0 AU n=237 (%) | CAC 1–999 AU n=1,613 (%) | CAC ≥1000 AU n=440 (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 1,965 (85.8) | 219 (92.4) | 1,397 (86.6) | 349 (79.3) | |

| Yes | 115 (5.0) | 5 (2.1) | 75 (4.7) | 35 (8.0) | |

| Missing | 210 (9.2) | 13 (5.5) | 141 (8.7) | 56 (12.7) | |

| Hearing loss | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 715 (31.2) | 92 (38.8) | 528 (32.7) | 95 (21.6) | |

| Yes | 1,327 (58.0) | 108 (45.6) | 923 (57.2) | 296 (67.3) | |

| Missing | 248 (10.8) | 37 (15.6) | 162 (10.0) | 49 (11.1) | |

| Low ankle brachial Index | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 1,539 (67.2) | 191 (80.6) | 1,086 (67.3) | 262 (59.5) | |

| Yes | 294 (12.8) | 6 (2.5) | 211 (13.1) | 77 (17.5) | |

| Missing | 457 (20.0) | 40 (16.9) | 316 (19.6) | 101 (23.0) | |

| High pulse wave velocity | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 836 (36.5) | 118 (49.8) | 605 (37.5) | 113 (25.7) | |

| Yes | 838 (36.6) | 63 (26.6) | 595 (36.9) | 180 (40.9) | |

| Missing | 616 (26.9) | 56 (23.6) | 413 (25.6) | 147 (33.4) | |

| Reduced forced vital capacity | 0.002 | ||||

| No | 900 (39.3) | 113 (47.7) | 644 (39.9) | 143 (32.5) | |

| Yes | 899 (39.3) | 80 (33.7) | 635 (39.4) | 184 (41.8) | |

| Missing | 491 (21.4) | 44 (18.6) | 334 (20.7) | 113 (25.7) | |

| Impaired physical function | 0.058 | ||||

| No | 966 (42.2) | 110 (46.4) | 693 (43.0) | 163 (37.1) | |

| Yes | 1,244 (54.3) | 122 (51.5) | 866 (53.7) | 256 (58.2) | |

| Missing | 80 (3.5) | 5 (2.1) | 54 (3.3) | 21 (4.8) | |

| Impaired grip strength | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 485 (21.2) | 67 (28.3) | 351 (21.8) | 67 (15.2) | |

| Yes | 1,583 (69.1) | 156 (65.8) | 1,100 (68.2) | 327 (74.3) | |

| Missing | 222 (9.7) | 14 (5.9) | 162 (10.0) | 46 (10.5) |

Figure 2:

Graphical abstract

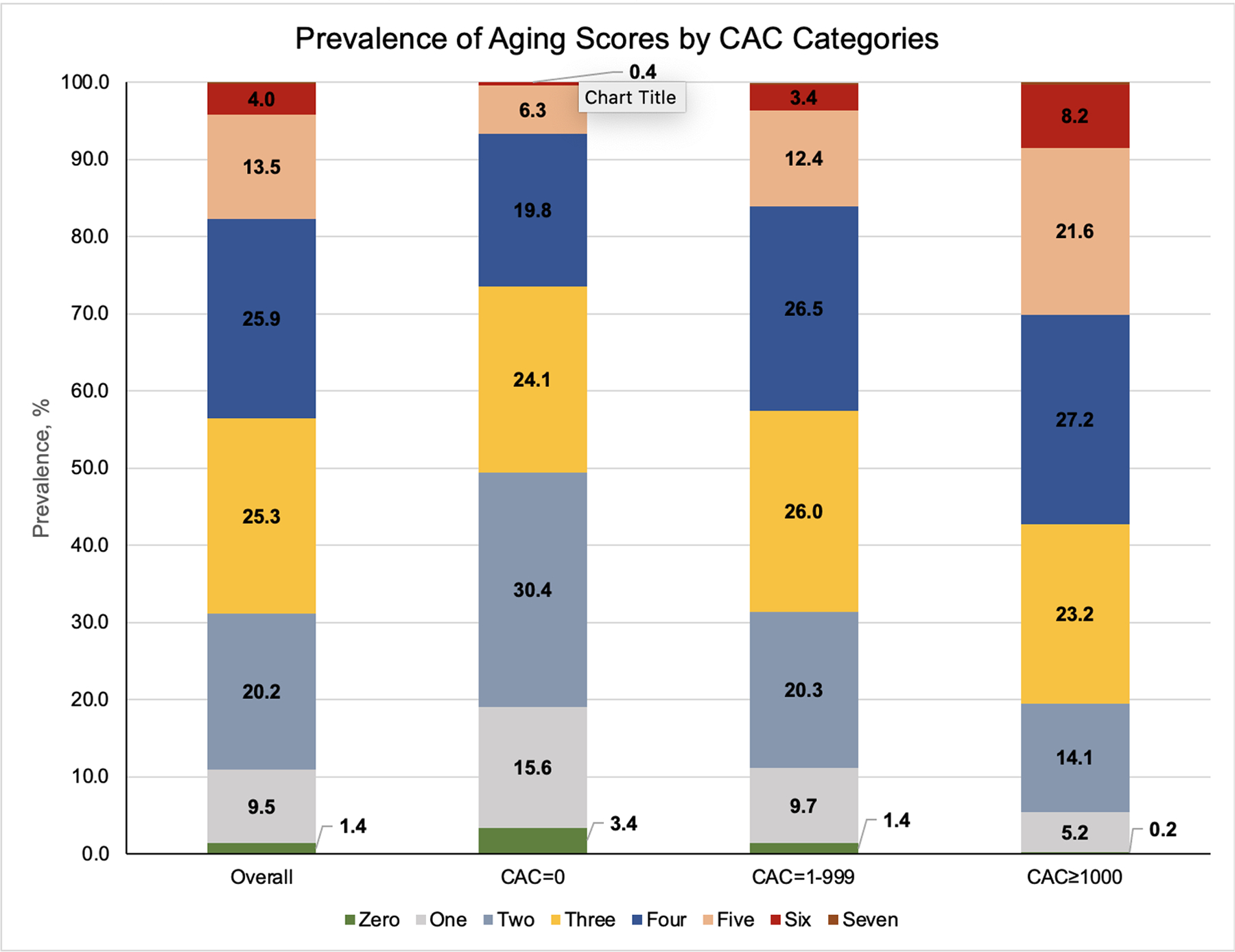

3.3. Mean composite aging score

Overall, 26.5% of participants with CAC=0 had >3 abnormal aging indices, while 57.4% of those with CAC ≥1000 had >3 abnormal indices (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table S3). The mean composite aging score of abnormal aging domains was 2.62 (±1.26) for those with CAC=0, compared to 3.71 (±1.34) for those with CAC ≥1000 (P<0.001) (Table 3 and Figure 2). After adjustment for age, sex, race, and study center, individuals with CAC scores of 0 were more likely to have a lower mean composite score of aging indices compared to the reference group of CAC: 1–999 (coefficient: −0.39, 95% CI: −0.55 - −0.22), while individuals with CAC≥1000 were more likely to have a higher composite score (coefficient: 0.37, 95% CI: 0.23 – 0.51) (Table 3).

Figure 1:

Prevalence of aging scores by CAC categories

Table 3:

Association of the mean domain score with CAC

| Mean score | Mean score | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=2,290) | 3.22 (±1.36) | - | - | ||

| CAC=0 (n=237) | 2.62 (±1.26) | −0.56 (−0.74 - −0.38) | <0.001 | −0.39 (−0.55 - −0.22) | <0.001 |

| CAC=1–999 (n=1,613) | 3.18 (±1.33) | Ref | Ref | ||

| CAC≥1000 (n=440) | 3.71 (±1.34) | 0.53 (0.39 – 0.67) | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.23 – 0.51) | <0.001 |

Model 1: Unadjusted

Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex, race, and study center

3.4. Association of CAC burden categories with individual aging indices

In logistic regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, race, and center, participants with CAC=0 were significantly less likely to have low ABI (aOR: 0.15, 95% CI: 0.07 – 0.34), high PWV (aOR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.41 – 0.80), and reduced FVC (aOR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.50 – 0.96). Conversely, participants with CAC≥1000 were more likely to have low ABI (aOR: 1.74, 95% CI:1.27 – 2.39), high PWV (aOR: 1.52, 95% CI: 1.15 – 2.00), impaired physical function (aOR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.05 – 1.73), and impaired grip strength (aOR: 1.46; 95% CI: 1.08 – 1.99) (Table 4).

Table 4:

Association of coronary artery calcification with the domains of aging (complete case analysis)

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | ||||

| CAC=0 (n=237) | 0.43 (0.17 – 1.06) | 0.067 | 0.53 (0.21 – 1.35) | 0.183 |

| CAC=1–999 (n=1,613) | Ref | Ref | ||

| CAC≥1000 (n=440) | 1.87 (1.23 – 2.84) | 0.003 | 1.48 (0.95 – 2.32) | 0.085 |

| Hearing loss | ||||

| CAC=0 | 0.67 (0.50 – 0.90) | 0.009 | 0.95 (0.70 – 1.31) | 0.774 |

| CAC=1–999 | Ref | Ref | ||

| CAC≥1000 | 1.78 (1.38 – 2.30) | <0.001 | 1.30 (0.99 – 1.71) | 0.063 |

| Low ankle brachial Index | ||||

| CAC=0 | 0.16 (0.07 – 0.37) | <0.001 | 0.15 (0.07 – 0.34) | <0.001 |

| CAC=1–999 | Ref | Ref | ||

| CAC≥1000 | 1.51 (1.13 – 2.03) | 0.006 | 1.74 (1.27 – 2.39) | 0.001 |

| High pulse wave velocity (≥ Median for sample) | ||||

| CAC=0 | 0.54 (0.39 – 0.75) | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.41 – 0.80) | 0.001 |

| CAC=1–999 | Ref | Ref | ||

| CAC≥1000 | 1.62 (1.25 – 2.10) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.15 – 2.00) | 0.003 |

| Reduced forced vital capacity | ||||

| CAC=0 | 0.72 (0.53 – 0.98) | 0.034 | 0.69 (0.50 – 0.96)a | 0.026 |

| CAC=1–999 | Ref | Ref | ||

| CAC≥1000 | 1.30 (1.02 – 1.67) | 0.033 | 1.18 (0.91 – 1.53)a | 0.211 |

| Impaired physical function | ||||

| CAC=0 | 0.89 (0.67 – 1.17) | 0.397 | 0.88 (0.65 – 1.18) | 0.389 |

| CAC=1–999 | Ref | Ref | ||

| CAC≥1000 | 1.26 (1.01 – 1.57) | 0.042 | 1.35 (1.05 – 1.73) | 0.017 |

| Impaired grip strength | ||||

| CAC=0 | 0.74 (0.54 – 1.01) | 0.061 | 0.91 (0.65 – 1.27) | 0.577 |

| CAC=1–999 | Ref | Ref | ||

| CAC≥1000 | 1.56 (1.17 – 2.08) | 0.003 | 1.46 (1.08 – 1.99) | 0.015 |

Model 1: Unadjusted

Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex, race, and study center.

Not adjusted for sex

In sensitivity analyses using CAC <10 as the lower cut-point (N=389 compared to N=237 using CAC=0), the results remained similar (Supplemental table S4). In Supplemental table S5, the association between CAC categories and aging indices analyzed on the continuous scale is presented, and the results and conclusions remained similar. Similarly, using a 5-category CAC categorization (CAC=0, N=237; CAC=1–99, N=582; CAC=100–399, N=555; CAC=400–999, N=476; CAC≥1000, N=440), the inference of our primary results was largely unchanged (Supplemental table S6).

4. DISCUSSION

In ARIC, we found that older adults aged 75 and older with CAC scores of 0 had more favorable aging indices, including normal cognitive function, favorable markers of vascular function like normal ABI and normal PWV, better hearing and lung function, and normal grip strength. Conversely, participants with CAC≥1000 had worse aging indices, including dementia, poor markers of vascular function, hearing loss, reduced lung function, and reduced grip strength. Additionally, individuals with CAC=0 had the lowest mean composite aging score while those with CAC ≥1000 had significantly higher mean composite aging score.

Many of the changes seen with aging are the result of underlying biological processes including cellular senescence, epigenetic alterations, telomere shortening, mitochondrial dysfunction and loss of proteostasis.1 Interestingly, atherogenesis is mediated by the same mechanisms occurring within the vascular walls compounded by genetic predisposition and acquired risk factors.5,6 These changes also occur in multiple cell types resulting in aging related changes across organ-systems.1,5,6

While age is typically noted as a major risk factor for cognitive decline in the elderly,32 our findings of normal cognitive function associated with the absence of CAC among older adults highlights that healthy brain aging and cognition may share similar risk factors with heart health, supporting the heart-brain hypothesis of shared risk factors.33–35 This is further emphasized by our findings of very elevated CAC being associated with dementia, consistent with a few prior studies that have associated CAC with cognitive decline, independent of age, education, sex, and other risk factors.32,36,37

Prior studies have postulated potential biochemical markers in the pathogenesis of hearing loss such as elevated serum glucose, homocysteine, and cholesterol that are also associated with CAD.38,39 Additionally, the loss of sensory cells and cortical neurons underlie the hearing loss observed with increasing age- changes that are likely due to the biological mechanisms outlined earlier.1 Similar to studies that observed a significant association between low-frequency hearing loss and subsequent CAD,38,39 our findings of an association between very high CAC scores and hearing loss among older adults support shared risk factors between hearing loss, atherosclerosis and CAD.40,41

Lung function is an established marker of aging, with a decline in FEV1, FVC and chest wall compliance observed with increasing age.1 Although studies have shown some association between lung function and CAD, few studies have explored the potential underpinnings of this association.42,43 A study done by Barr et al. among adults in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) observed no association between CAC and lung function but observed an association between poor lung function and calcification in peripheral vascular beds.43 While we did not find a significant association between very elevated CAC and poor lung function, we did observe an association between CAC scores of 0 and preserved lung function.

Frailty is a condition that culminates in increased vulnerability of individuals to physiologic stressors, and it has been associated with worse morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease, including CAD.44 Reduced physical strength is an important component of the definition of frailty in the elderly, and older age is characterized by a reduction in muscle mass and changes in muscle composition.1,44 Our findings of a significant association between markedly elevated CAC and measures of frailty suggests a potential utility of elevated CAC as a marker of subsequent frailty among older adults.

CAC is a well-established marker of vascular disease, and its strong association with ABI and PWV among our cohort of older adults adds to the body of literature emphasizing the utility of CAC in the prediction of non-coronary vascular disease.45,46 Finally, while CAC scores of 0 do not imply a complete absence of some of the decline seen with older age, as evidenced by the average composite aging score of 2.6 among individuals in that group, there was however, a strong association between increasing CAC and the composite aging score, further reinforcing an association between subclinical atherosclerosis and overall healthy/unhealthy aging.

In this study, CAC associates well with measures of healthy/unhealthy aging. Given the similar biologic basis of aging and atherosclerosis, CAC may be useful in both the research and clinical settings in identifying adults on an unhealthy aging trajectory before the changes become apparent, triggering early multi-specialist assessment and interventions aimed at improving their overall aging. Our findings are also important given the ongoing development of several pharmacologic agents that target the biological underpinnings of premature vascular aging including telomerase dysfunction and DNA damage, which could potentially extend to other organ systems.5

The strengths of our study include using a population of older adults (≥75 years), an age group that is generally understudied. Additionally, we explore several domains of aging shedding more light on potential associations between atherosclerosis and aging trajectories, identifying potential areas for future interventions in preventative and therapeutic healthcare. However, our findings should be interpreted in the setting of some limitations. First, our sample size is small, which could have attenuated the statistical significance of some of the associations observed. Additionally, since this is an older cohort, there is a potential for survival bias. However, this survival bias in inherent in most older cohorts and studies of healthy aging and is also present in the general older adult population encountered in clinical practice. Also, due to the cross-sectional nature of our study, we cannot infer causality. Finally, some of the aging domains were not assessed contemporaneously with CAC. For instance, ABI and PWV were assessed in visit 6 while CAC assessment was done in visit 7.

In conclusion, CAC scores of 0 were associated with more favorable aging indices, while CAC scores ≥1000 were associated with worse aging indices. Thus, CAC, which is easily measured, highly accessible, and endorsed in clinical guidelines, is a marker of overall healthy/unhealthy aging. Our findings highlight new ways that vascular aging, as identified by CT imaging, can be utilized as a marker for aging phenotypes and aging trajectory, potentially informing decisions to defer or trigger multi-specialist assessment and potentially guide holistic management among older adults.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Older adults with coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores of 0 had more favorable aging indices, including normal cognitive function, favorable markers of vascular function like normal ABI and normal PWV, better hearing and lung function, and normal grip strength.

Older adults with CAC≥1000 had worse aging indices, including dementia, poor markers of vascular function, hearing loss, reduced lung function, and reduced grip strength.

Vascular aging as identified by CT imaging can be utilized as a marker for aging phenotypes and aging trajectory.

Acknowledgments

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health, and Human Services, under Contract numbers (HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700004I, HHSN268201700005I). ABI and PWV measures were funded by R01AG053938.The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Declaration of interest

Michael J. Blaha has grants funded by NIH, FDA, AHA, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Amgen. He is on advisory boards for Amgen, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Roche, Inozyme, Kaleido, 89Bio; and consults for Emocha health and Kowa.

The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data sharing

De-identified data from the ARIC dataset that underlie the results in this article can be obtained from the ARIC data coordinating center. A data request form will need to be submitted and can be obtained from the ARIC website (https://sites.cscc.unc.edu/aric/distribution-agreements). Data will be accessible after the request is processed by the ARIC data coordinating center.

CREDIT author statement

Obisesan O.H, Boakye E, and Blaha M.J are the guarantors for this manuscript and take full responsibility for this work including study conceptualization and design, access to data and data analysis, interpretation of results and decision to submit and publish the manuscript.

Dardari Z. contributed to data access, analysis and review of the content of the manuscript.

Wang F.M, Dzaye O, Cainzos-Achirica M, Meyer M.L, Grottesman R, Palta P, Coresh J, Howard-Claudio C.M, Lin F.R,Punjabi N, Nasir K, Matsushita K, contributed to the editing and critical review of the content of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Khan SS, Singer BD, Vaughan DE. Molecular and physiological manifestations and measurement of aging in humans. Aging Cell. 2017;16(4). doi: 10.1111/acel.12601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2018 Key Findings Data from the National Vital Statistics System.; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db355_tables-508.pdf#1. Accessed November 23, 2020.

- 3.• U.S. - seniors as a percentage of the population 2050 | Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/457822/share-of-old-age-population-in-the-total-us-population/. Accessed November 23, 2020.

- 4.Peel NM, McClure RJ, Bartlett HP. Behavioral determinants of healthy aging. Am J Prev Med. 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang JC, Bennett M. Aging and atherosclerosis: Mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ Res. 2012;111(2). doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Sorond F, Merkely B, Csiszar A. Mechanisms of Vascular Aging, A Geroscience Perspective: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(8). doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Erbel R, Watson KE. Coronary Calcium Score and Cardiovascular Risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budoff MJ, Young R, Burke G, et al. Ten-year association of coronary artery calcium with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur Heart J. 2018. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaha M, Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, et al. Absence of Coronary Artery Calcification and All-Cause Mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaha MJ, Cainzos-Achirica M, Greenland P, et al. Role of Coronary Artery Calcium Score of Zero and Other Negative Risk Markers for Cardiovascular Disease : the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handy CE, Desai CS, Dardari ZA, et al. The Association of Coronary Artery Calcium with Noncardiovascular Disease the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng AW, Dardari Z, Blumenthal RS, et al. Very high coronary artery calcium (CAC {greater than or equal to} 1000) and association with CVD events, non-CVD outcomes, and mortality: Results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circ. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng AW, Mirbolouk M, Orimoloye OA, et al. Long-Term All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in Asymptomatic Patients With CAC ≥1,000: Results From the CAC Consortium JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, et al. 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering in the Management of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(14):1366–1418. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2022.07.006/SUPPL_FILE/MMC1.PDF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Report on Ageing And HeAltH.; 2015. www.who.int. Accessed November 25, 2020.

- 16.Michel JP, Sadana R. “Healthy Aging” Concepts and Measures. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019.doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D’Agostino RB, et al. Application of New Cholesterol Guidelines to a Population-Based Sample. N Engl J Med. 2014. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1315665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yano Y, O’Donnell CJ, Kuller L, et al. Association of coronary artery calcium score vs age with cardiovascular risk in older adults: An analysis of pooled population-based studies. JAMA Cardiol. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hecht HS. Coronary artery calcium scanning: Past, present, and future. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright JD, Folsom AR, Coresh J, et al. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: JACC Focus Seminar 3/8. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(23):2939. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2021.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knopman DS, Gottesman RF, Sharrett AR, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and dementia prevalence: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2016;2. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottesman RF, Albert MS, Alonso A, et al. Associations between midlife vascular risk factors and 25-year incident dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10). doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shukla A, Reed NS, Nicole MA, Lin FR, Deal JA, Goman AM. Hearing Loss, Hearing Aid Use, and Depressive Symptoms in Older Adults - Findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study (ARIC-NCS). Journals Gerontol - Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76(3). doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kianoush S, Al Rifai M, Cainzos-Achirica M, et al. Thoracic extra-coronary calcification for the prediction of stroke: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heffernan K, Stoner L, Meyer ML, et al. Associations between estimated and measured carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity in older Black and White adults: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. J Cardiovasc Aging. 2022. doi: 10.20517/jca.2021.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Sang Y, et al. Ankle-brachial index and physical function in older individuals: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Atherosclerosis. 2017;257. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.11.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu X, Mok Y, Ding N, et al. Physical Function and Subsequent Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Older Adults: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(17):25780. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.025780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li D, Alam AB, Yu F, Kucharska-Newton A, Windham BG, Alonso A. Sphingolipids and physical function in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1). doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80929-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kucharska-Newton AM, Palta P, Burgard S, et al. Operationalizing Frailty in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Cohort. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(3):382. doi: 10.1093/GERONA/GLW144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in Older AdultsEvidence for a Phenotype. Journals Gerontol Ser A. 2001;56(3):M146–M157. doi: 10.1093/GERONA/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujiyoshi A, Jacobs DR, Fitzpatrick AL, et al. Coronary artery calcium and risk of dementia in MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(5). doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roger VL. The heart-brain connection: From evidence to action. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(43). doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, et al. Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment andDementia: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American HeartAssociation/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(9):2672.doi: 10.1161/STR.0B013E3182299496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pase MP, Beiser A, Enserro D, et al. Association of Ideal Cardiovascular Health with Vascular Brain Injury and Incident Dementia. Stroke. 2016;47(5):1201. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuller LH, Lopez OL, MacKey RH, et al. Subclinical cardiovascular disease and death, dementia, and coronary heart disease in patients 80+ years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9). doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reis JP, Launer LJ, Terry JG, et al. Subclinical Atherosclerotic Calcification and Cognitive Functioning in Middle-Aged Adults: The CARDIA Study. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231(1):72–77. doi: 10.1016/J.ATHEROSCLEROSIS.2013.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fang Q, Wang Z, Zhan Y, et al. Hearing loss is associated with increased CHD risk and unfavorable CHD-related biomarkers in the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2018;271. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gates GA, Cobb JL, D’agostino RB, Wolf PA. The Relation of Hearing in the Elderly to the Presence of Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Arch Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 1993;119(2). doi: 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880140038006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wattamwar K, Jason Qian Z, Otter J, et al. Association of cardiovascular comorbidities with hearing loss in the older old. JAMA Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(7). doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.0643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer ME, Schubert CR, Nondahl DM, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis and increased risk of hearing impairment. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238(2). doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schroeder EB, Welch VL, Couper D, et al. Lung Function and Incident Coronary Heart Disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(12). doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barr RG, Ahmed FS, Carr JJ, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis, airflow obstruction and emphysema: The MESA Lung Study. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(4). doi: 10.1183/09031936.00165410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richter D, Guasti L, Walker D, et al. Frailty in cardiology: definition, assessment and clinical implications for general cardiology. A consensus document of the Council for Cardiology Practice (CCP), Association for Acute Cardio Vascular Care (ACVC), Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP), European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), Council on Valvular Heart Diseases (VHD), Council on Hypertension (CHT), Council of Cardio-Oncology (CCO), Working Group. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29(1):216–227. doi: 10.1093/EURJPC/ZWAA167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tillin T, Chambers J, Malik I, et al. Measurement of pulse wave velocity: Site matters. J Hypertens. 2007;25(2). doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280115bea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tullos BW, Sung JH, Lee JE, Criqui MH, Mitchell ME, Taylor HA. Ankle-brachial index (ABI), abdominal aortic calcification (AAC), and coronary artery calcification (CAC): The Jackson heart study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29(4). doi: 10.1007/s10554-012-0145-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.