Summary

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) currently lacks effective therapies, leaving a critical need for new treatment options. A previous study identified the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) amplification in HCC patients, raising the question of whether ALK inhibitors could be a viable treatment. Here, we showed that both ALK inhibitors and ALK knockout effectively halted HCC growth in cell cultures. Lorlatinib, a potent ALK inhibitor, suppressed HCC tumor growth and metastasis across various mouse models. Additionally, in an advanced immunocompetent humanized mouse model, when combined with an anti-PD-1 antibody, lorlatinib more potently suppressed HCC tumor growth, surpassing individual drug efficacy. Lorlatinib induced apoptosis and senescence in HCC cells, and the senolytic agent ABT-263 enhanced the efficacy of lorlatinib. Additional studies identified that the apoptosis-inducing effect of lorlatinib was mediated via GGN and NRG4. These findings establish ALK inhibitors as promising HCC treatments, either alone or in combination with immunotherapies or senolytic agents.

Subject areas: Biological sciences, Cancer, Cancer systems biology, Natural sciences, Pharmacology, Systems biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

ALK inhibition suppresses HCC tumor growth and metastasis

-

•

ALK inhibition induces apoptosis and senescence in HCC cells

-

•

ALK inhibition-induced apoptosis in HCC depends on its targets GGN and NRG4

-

•

Anti-PD-1 antibody and senolytic agents enhance the efficacy of lorlatinib in HCC

Biological sciences; Cancer; Cancer systems biology; Natural sciences; Pharmacology; Systems biology

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common form of liver cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide.1,2 The major etiological factors for HCC include chronic hepatitis viral infections, notably hepatitis B and C; prolonged exposure to aflatoxins, a potent fungal metabolite prevalent in contaminated foods; and metabolic disorders such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and alcoholic liver disease (ALD).1,2,3 Current treatment strategies for HCC include a range of modalities, including surgical resection, liver transplantation, locoregional therapies such as radiofrequency ablation and transarterial chemoembolization, and systemic therapies such as targeted therapies and immunotherapies.1,2,3 The choice of therapy depends on factors such as tumor stage, liver function, the patient’s overall health, and the presence of an underlying liver disease.4,5 However, despite major advances, challenges persist owing to the often-advanced stage of diagnosis and the inherent heterogeneity of HCC.4,5 This is reflected in the 18% five-year survival rate for HCC when combined for all stages.1,2,3 Furthermore, the survival rate drops significantly in patients with distal metastasis, and, accordingly, only 2% of HCC patients with distal metastasis survive beyond five years.1,2,3,6

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) is a receptor tyrosine kinase that plays a pivotal role in various cellular processes, including cell growth, differentiation, and migration.7,8,9 Originally identified as an oncogene in lymphomas, ALK aberrations have been implicated in diverse malignancies, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and neuroblastoma.7,8,9,10 ALK aberrations often lead to constitutive kinase activity and uncontrolled cell proliferation, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention. Because of the oncogenic role of ALK in various cancers, patients with ALK-positive tumors are often treated with ALK inhibitors.7,8,9 Overall, ALK inhibitors have shown superior therapeutic outcomes in ALK-positive lung cancer patients compared to chemotherapy, and third-generation ALK inhibitors such as lorlatinib have shown better survival benefits in ALK-positive lung cancers compared to previous-generation ALK inhibitors such as crizotinib.11 Similarly, ALK inhibitors have been shown to be efficacious against other ALK-positive cancers.12,13 Overall, these findings highlight that ALK inhibitors are clinically efficacious agents for treating ALK-positive tumors.

A previous study showed that HCC exhibits ALK gene amplification and that ALK gene-amplified HCC displays significantly poor overall survival.14 In this study, we show that ALK inhibitors (ceritinib and lorlatinib) and genetic ALK knockout effectively suppressed HCC growth in cell cultures. Lorlatinib also reduced tumor growth and metastasis in various models of HCC tumor growth and metastasis, including in a state-of-the-art immunocompetent humanized mouse model. Lorlatinib alone hindered tumor growth even without the immune system; however, when combined with an anti-PD-1 antibody, it displayed superior efficacy in suppressing HCC than either drug alone. Mechanistically, inhibition of ALK led to increased senescence and apoptosis induction in HCC. Furthermore, the senolytic agent ABT-263 enhanced the efficacy of lorlatinib. Finally, our RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) studies of lorlatinib-treated HCC cells identified that ALK inhibition results in the upregulation of GGN and downregulation of NRG4, which was in part necessary for apoptosis induction following lorlatinib treatment. Overall, these findings demonstrate that ALK inhibitors are effective for HCC treatment, either alone or in combination with immunotherapy or senolytic agents.

Results

Inhibition of ALK blocks HCC growth and metastatic attribute

Previous studies have shown that the receptor tyrosine kinase ALK and its fusion proteins (e.g., EML4-ALK) can function as oncogenic proteins.8 Because of the driver role of ALK and its fusion proteins in cancer, several highly efficacious ALK inhibitors have been developed and approved for the treatment of lung cancer and other ALK-positive cancers in clinical settings.9,11 A previous study demonstrated gene copy number amplification of ALK in HCC and showed that ALK amplification is associated with reduced survival of HCC patients.14 However, whether ALK targeting is of therapeutic value for treating HCC has not yet been evaluated. Therefore, we investigated whether ALK inhibition could suppress the growth and metastatic attributes of HCC cells. To test this possibility, we first treated a panel of HCC cell lines with two different ALK inhibitors, ceritinib and lorlatinib, and measured their growth in cell culture using a long-term survival assay. Ceritinib and lorlatinib are ATP-competitive ALK inhibitors. Both ceritinib and lorlatinib are approved for treating ALK-positive metastatic lung cancers and other cancer types in the clinic, and patients treated with these inhibitors show significant survival advantages.11 Ceritinib is a second-generation ALK inhibitor that can overcome some of the resistance mutations that develop after crizotinib treatment, such as L1196M and G1269A.15 However, ceritinib is still vulnerable to other mutations, such as G1202R and I1171T, which can cause resistance to ceritinib and other second-generation ALK inhibitors. Lorlatinib is a third-generation ALK inhibitor that can overcome most of the known resistance mutations to ALK inhibitors, including those that ceritinib cannot overcome, such as G1202R and I1171T.16 Furthermore, since lorlatinib can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), it has shown efficacy in treating brain metastasis in ALK-positive lung cancers.11

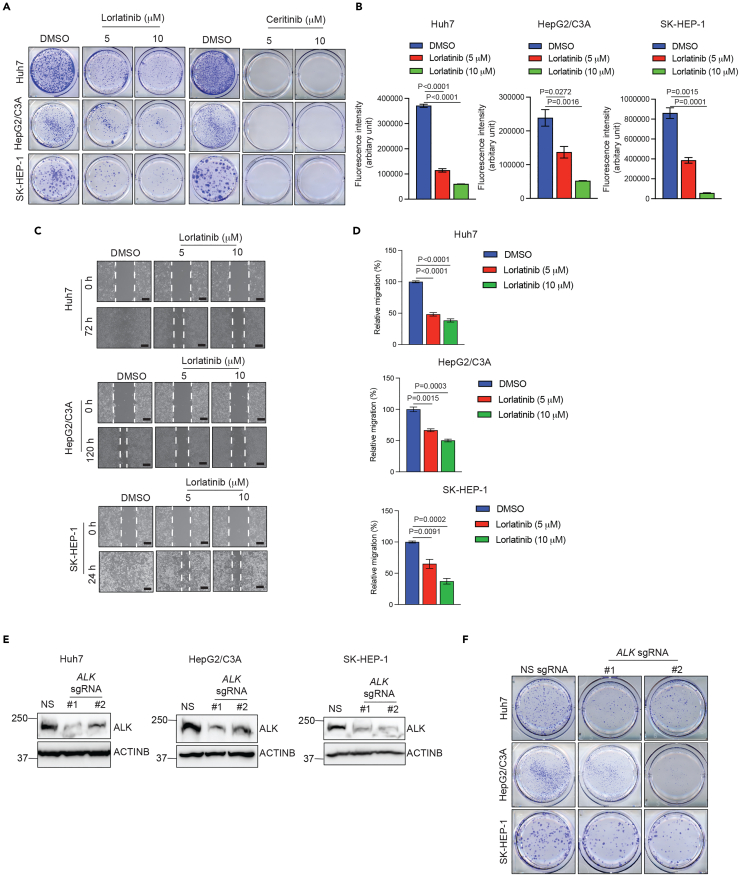

We found that both lorlatinib and ceritinib effectively blocked the colony-forming ability of HCC cells in the long-term clonogenic assay (Figure 1A). Next, to quantitatively determine the effect of lorlatinib on HCC cells, we performed quantitative soft-agar assays to measure the anchorage-independent growth of HCC cells. We found that lorlatinib blocked anchorage-independent growth of HCC cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1B). Consistent with the result of clonogenic assays, analysis of HCC cells treated with lorlatinib and ceritinib resulted in reduced p-ALK levels and its downstream signaling, as observed by reduced p-AKT levels (Figures S1A and S1B).

Figure 1.

ALK inhibition suppresses HCC growth and metastatic attributes in cell culture models

(A) Indicated HCC cell lines were treated with DMSO or indicated concentrations of lorlatinib or ceritinib and analyzed by clonogenic assay. Representative wells for the indicated HCC cell lines under the indicated treatment conditions are shown.

(B) Indicated HCC cell lines were treated with DMSO or indicated concentrations of lorlatinib and analyzed by quantitative soft agar assay. Fluorescence intensities (Arbitrary units) are plotted. For Huh7, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 5 μM (n = 3 each)), t = 28.01, df = 4, and p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 10 μM (n = 3 each). t = 50.03, df = 4. For HepG2/C3A, p = 0.0272 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 5 μM (n = 3 each), t = 3.402, df = 4), and p = 0.0016 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 10 μM (n = 3 each)), t = 7.615, df = 4. For SK-HEP-1, p = 0.0015 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 5 μM (n = 3 each)), t = 7.799, df = 4, and for p = 0.0001 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 10 μM (n = 3 each)), t = 14.93, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(C) Indicated HCC cell lines were treated with DMSO or indicated concentrations of lorlatinib, and cell migration was analyzed using a wound healing assay. Representative images under indicated treatment conditions for indicated HCC cell lines are shown. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(D) Bar diagrams are presented to show relative migration (%) from the experiment presented in (C). For Huh7, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 5 μM (n = 3 each), t = 16.11, df = 4, and for p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 10 μM (n = 3 each). t = 20.53, df = 4. For HepG2/C3A, p = 0.0015 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 5 μM (n = 3 each)), t = 7.729, df = 4), and p = 0.0003 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 10 μM (n = 3 each)), t = 11.77, df = 4. For SK-HEP-1, p = 0.0091 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 5 μM (n = 3 each)), t = 4.736, df = 4, and for p = 0.0002 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib 10 μM (n = 3 each)), t = 13.01, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(E) Indicated HCC cell lines expressing either non-specific sgRNA or ALK-specific sgRNAs were analyzed for ALK protein expression using immunoblotting. ACTINB was used as a loading control.

(F) Indicated HCC cell lines expressing either non-specific sgRNA or ALK-specific sgRNAs were analyzed for colony formation using clonogenic assays. Representative wells for the indicated HCC cell lines under indicated conditions are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM; See also, Figures S1 and S2.

To test whether ALK inhibition affects the metastatic attributes of HCC cells, we performed a wound healing assay. We found that lorlatinib also suppressed HCC cell migration (Figures 1C and 1D). After establishing the cell proliferation and metastatic attribute inhibitory effect of ALK small-molecule inhibitors, we investigated whether genetic knockout of ALK can achieve the same growth-inhibitory effect as the small-molecule inhibitors. Therefore, we deleted ALK using a CRISPR-Cas9-based approach (Figure 1E). In complete agreement with the results of ALK small-molecule inhibitors, we found that the genetic knockout of ALK also blocked the clonogenic ability of HCC cells (Figure 1F). Furthermore, consistent with the result of clonogenic assay, we observed reduced p-AKT levels in ALK-knockout HCC cells (Figure S1C). Finally, to further establish that the observed inhibition of HCC cells by lorlatinib was dependent on ALK expression, we treated ALK-knockout HCC cells with lorlatinib and performed a clonogenic assay. Consistent with the rest of the results, ALK-knockout cells were not significantly inhibited by lorlatinib, demonstrating that the effect of lorlatinib was mediated via ALK (Figure S2). Collectively, these results demonstrate that both genetic and pharmacological ALK inhibition suppress HCC cell proliferation and migration.

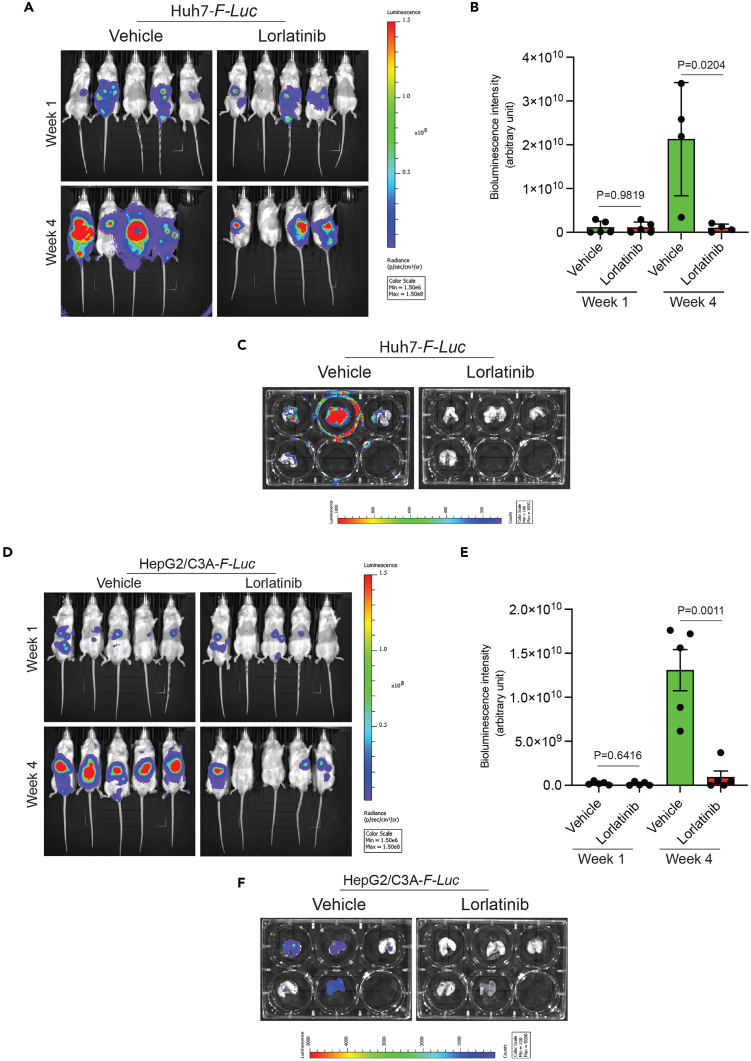

Lorlatinib inhibits tumor growth and metastasis in mouse models of HCC

Based on the cell culture results, we investigated whether lorlatinib inhibits HCC growth and metastasis in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we labeled the HCC cell lines HepG2/C3A and Huh7 with the firefly luciferase gene (F-Luc). F-Luc-labeled HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells were then injected into immunodeficient NOD scid gamma (NSG) mice via intrahepatic injection. After the hepatic tumors became detectable by bioluminescence imaging, the mice were treated with either vehicle or lorlatinib. Hepatic tumor growth and metastatic progression were monitored using F-Luc-based bioluminescence imaging. We found that lorlatinib treatment significantly blocked the tumor growth of Huh7 cells (Figures 2A and 2B). At the end of the experiments, we also isolated the lungs of mice and imaged them to monitor metastasis. Consistent with the significant reduction in tumor growth, lorlatinib-treated mice showed reduced lung metastasis (Figure 2C). Similarly, lorlatinib significantly blocked tumor growth and lung metastasis in HepG2/C3A cells (Figures 2D–2F). Collectively, these results demonstrate that lorlatinib treatment significantly inhibits HCC tumor growth and metastatic progression.

Figure 2.

Lorlatinib inhibits tumor growth and metastatic progression in the orthotopic mouse model of human HCC xenograft

(A) Firefly luciferase (F-Luc)-labeled Huh7 cells (Huh7-F-Luc) were orthotopically injected into the liver of NSG mice (n = 5) followed by treatment with lorlatinib (100 mg/kg) or vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 5% Tween-80, and 45% saline) after 1 week of injecting the cells. Tumor growth was monitored using F-Luc-based bioluminescence imaging. Mouse bioluminescence images at the indicated time points are shown.

(B) Bioluminescent intensities (arbitrary units) for the mice are shown in (A) is plotted. For p = 0.9819 (Week 1, Vehicle versus Lorlatinib (n = 5 each)), t = 0.02344, df = 8, and p = 0.0204 (Week 4, Vehicle versus Lorlatinib (n = 4 each)), t = 11.77, df = 6. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(C) Bioluminescence images of the lungs of mice isolated at the end of the experiment from the mice shown in (A).

(D) Firefly luciferase-labeled HepG2/C3A (HepG2/C3A-F-Luc) cells were orthotopically injected into the liver of NSG mice (n = 5) followed by treatment with lorlatinib (100 mg/kg) or vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 5% Tween-80, and 45% saline) after 1 week of injecting the cells. Tumor growth was monitored using F-Luc-based bioluminescence imaging. Mouse bioluminescence images at the indicated time points are shown.

(E) Bioluminescent intensities (arbitrary units) for the mice shown in (D) are plotted. For p = 0.6416 (week 1, vehicle versus lorlatinib (n = 5 each)), t = 0.4837, df = 8), and p = 0.0011 (week 4, vehicle versus lorlatinib (n = 5 each)), t = 4.973.77, df = 8. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(F) Bioluminescence images of the lungs of mice isolated at the end of the experiment from the mice shown in (D). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

We then investigated whether lorlatinib could also inhibit the growth of HCC metastatic tumors. To test this, we used a metastatic HCC cell line, SK-HEP-1, labeled with F-Luc, and injected it into mice to induce lung metastasis. Once the metastatic tumors became detectable, mice were treated with either vehicle or lorlatinib, and metastatic growth was analyzed using F-Luc-based bioluminescence imaging. We found that lorlatinib treatment significantly attenuated lung metastases compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figures 3A–3C). Taken together, these studies demonstrate that ALK is an important driver of HCC tumor growth and metastasis.

Figure 3.

Lorlatinib inhibits the lung metastatic growth of HCC in mice

(A) Firefly luciferase-labeled SK-HEP-1 (SK-HEP-1-F-Luc) cells were injected into NSG mice (n = 8) to achieve lung metastasis, followed by treatment with lorlatinib (100 mg/kg) or vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 5% Tween-80, and 45% saline) after 1 week of injecting the cells. Metastatic growth of SK-HEP-1-F-Luc cells was monitored using F-Luc-based bioluminescence imaging. Mouse bioluminescence images at the indicated time points are shown.

(B) Bioluminescent intensities (arbitrary units) for the mice shown in (A) are plotted. For p = 0.2433 (week 1, vehicle versus lorlatinib (n = 8 each)), t = 1.218, df = 14, and p = 0.0008 (week 3, vehicle (n = 8) versus lorlatinib (n = 7)), t = 4.356, df = 13. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(C) Bioluminescence images of the lungs of mice isolated at the end of the experiment from the mice shown in (A). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

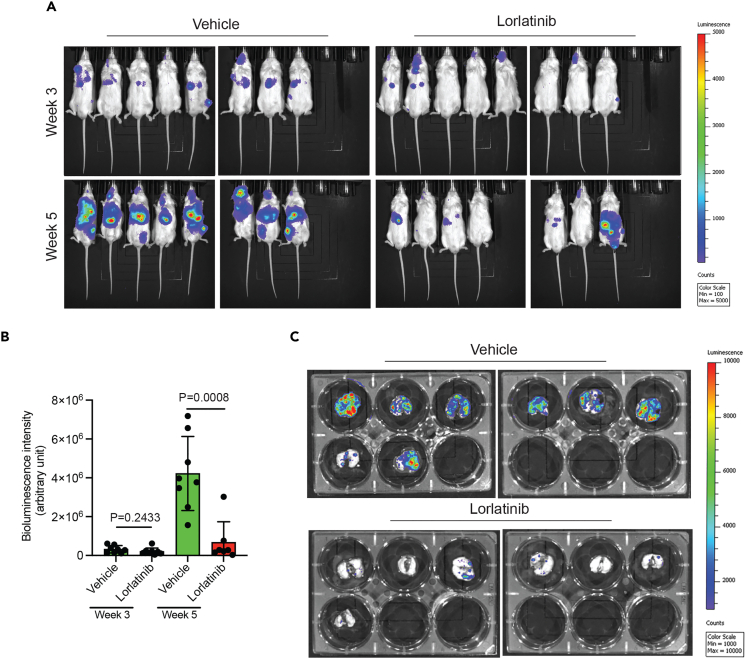

Lorlatinib impairs the growth of HCC patient-derived xenograft in mice

Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) are superior to HCC cell lines owing to their ability to retain intricate biological complexities. This includes preserving aspects such as intratumoral heterogeneity, interactions with surrounding stromal components, and the in vivo tumor microenvironment, encompassing elements such as immune cells and angiogenesis. Therefore, to further bolster the results of our study, we examined the efficacy of an HCC PDX obtained from the Novartis PDX collection. NSG mice were implanted with HCC PDX, and, once the tumors became detectable, mice were divided into two experimental groups and were treated with either lorlatinib or vehicle control. Consistent with the results of the orthotopic and metastatic HCC cell lines, lorlatinib significantly blocked the tumor-forming ability of HCC PDX (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Lorlatinib blocks HCC PDX tumor growth and enhances the anti-tumor effect of the anti-PD-1 antibody

(A) HCC PDX (NIBRX-2969) was injected subcutaneously into NSG mice (n = 6). When the tumor volumes reached approximately 100 mm3, HCC PDX-bearing mice were treated with lorlatinib (100 mg/kg) or vehicle. Tumor volumes were measured at indicated weeks. Average tumor volumes are plotted on the left and tumor pictures are shown on the right. p < 0.0001 for vehicle versus lorlatinib (n = 6 each)), t = 8.189, df = 10. Statistical assessments were performed by first calculating the area under the curve (AUC), which was then used for p value calculations using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(B) HCC PDX (NIBRX-2969) was subcutaneously injected into the flanks of immunodeficient NSG-Tg(hu-L15) mice. When the tumor volumes reached approximately 100 mm3, HCC PDX-bearing mice were treated with lorlatinib (100 mg/kg) or vehicle. Tumor volumes were measured at indicated weeks. Average tumor volumes are plotted on the left, and tumor pictures are shown on the right. p = 0.0018 for vehicle versus lorlatinib (n = 8 each), t = 3.827, df = 14. Statistical assessments were performed by first calculating the area under the curve (AUC), which was then used for p value calculations using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(C) HCC PDX (NIBRX-2969) was injected subcutaneously into immunocompetent NSG-Tg(hu-L15)-CD34 mice. When the tumor volumes reached approximately 100 mm3, HCC PDX-bearing mice were treated with lorlatinib (100 mg/kg) or vehicle. Tumor volumes were measured at indicated weeks. Average tumor volumes are plotted on the left and tumor pictures are shown on the right. p < 0.0001 for Vehicle (n = 7) versus Lorlatinib (n = 6), t = 12.25, df = 11. Statistical assessments were performed by first calculating the area under the curve (AUC), which was then used for p value calculations using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(D) Schematic showing the experimental design for lorlatinib and anti-PD-1 antibody therapy in Hepa1-6-derived tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice.

(E) Hepa1-6 cells were injected subcutaneously into the flank of C57BL/6 mice. When the tumor volumes reached approximately 100 mm3, HCC PDX-bearing mice were treated with vehicle, lorlatinib (100 mg/kg), anti-PD-1 mAb (25 μg/mice), or combination of lorlatinib and anti-PD-1. Tumor volumes were measured at indicated time points. The average tumor volumes for indicated treatment conditions are shown. p = 0.0160 for vehicle (n = 12) versus lorlatinib (n = 11), t = 2.620, df = 21. p = 0.1144 for vehicle (n = 12) versus anti-PD-1 (n = 9), t = 1.655, df = 19. p = 0.0002 for vehicle (n = 12) versus anti-PD-1+lorlatinib (n = 10), t = 4.638, df = 20. p = 0.0047 for lorlatinib (n = 11) versus anti-PD-1+ lorlatinib (n = 10), t = 3.197, df = 19. p = 0.0019 for anti-PD-1 (n = 9) versus anti-PD-1+lorlatinib (n = 10), t = 3.669, df = 17. Statistical assessments were performed by first calculating the area under the curve (AUC), which was then used for p value calculations using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(F) Representative tumors (n = 5) under the indicated conditions are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

The host immune response against tumors plays an important role in suppressing tumor initiation and progression.17 Numerous studies have shown that the host immune system enhances the effects of several anti-cancer drugs.18,19,20 Therefore, we investigated whether lorlatinib was more effective in suppressing HCC in the presence of the human immune system than in the absence of the human immune system. To test this, we used an immunocompetent mouse model transplanted with human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the NGS-(Tg-huIL15) background. NGS-(Tg-huIL15) is a transgenic mouse that expresses the human interleukin (IL)-15 gene.21 The presence of the human IL15 gene in these mice not only allows CD34+ cells to differentiate into T and B cell lineages but also allows the development of natural killer (NK) cells. As a control, we used immunodeficient NGS-Tg(huIL15) mice without human CD34+ transplantation. HCC PDX was injected into either immunocompetent human CD34+ HSC-transplanted NGS-Tg(huIL15) mice or immunodeficient NGS-Tg(huIL15) mice. These PDX-bearing mice were then treated with lorlatinib or the vehicle control. We found that lorlatinib was equally effective in suppressing HCC PDX growth in both immunocompetent (human CD34+ HSC-transplanted NGS-Tg(huIL15) mice) and immunodeficient NGS-Tg(huIL15) mice (Figures 4B and 4C). These results demonstrate that the tumor-suppressive effect of the ALK inhibitor lorlatinib largely occurs through a cell-intrinsic mechanism in HCC cells.

Lorlatinib enhances the anti-tumor effect of anti-PD-1 antibody in a syngeneic mouse model of HCC

Because the tumor-suppressive effect of lorlatinib was independent of the host immune response and largely due to a cell-intrinsic mechanism, therefore, we investigated whether lorlatinib can be combined with an anti-PD-1 antibody that overcomes the adaptive immune checkpoint and works by a cell-extrinsic mechanism. To test this hypothesis, we used a syngeneic mouse model of hepatic tumor growth based on the Hepa1-6 cell line in a C57BL/6 mouse background. C57BL/6 mice were subcutaneously injected with Hepa1-6 cells and treated with vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 5% Tween-80, and 45% saline), lorlatinib, anti-PD-1 antibody, or a combination of lorlatinib and anti-PD-1 antibody (Figure 4D). Although both lorlatinib and the anti-PD-1 antibody suppressed Hepa1-6 tumors, a combination of lorlatinib and the anti-PD-1 antibody was significantly more effective in suppressing Hepa1-6 tumors in mice than either lorlatinib or the anti-PD-1 antibody alone (Figures 4E and 4F). Collectively, these results demonstrate that combining lorlatinib to suppress the cell-intrinsic tumor regulatory pathway and an anti-PD-1 antibody to suppress anti-tumor immunity might be a preferable approach for treating HCC rather than using them alone.

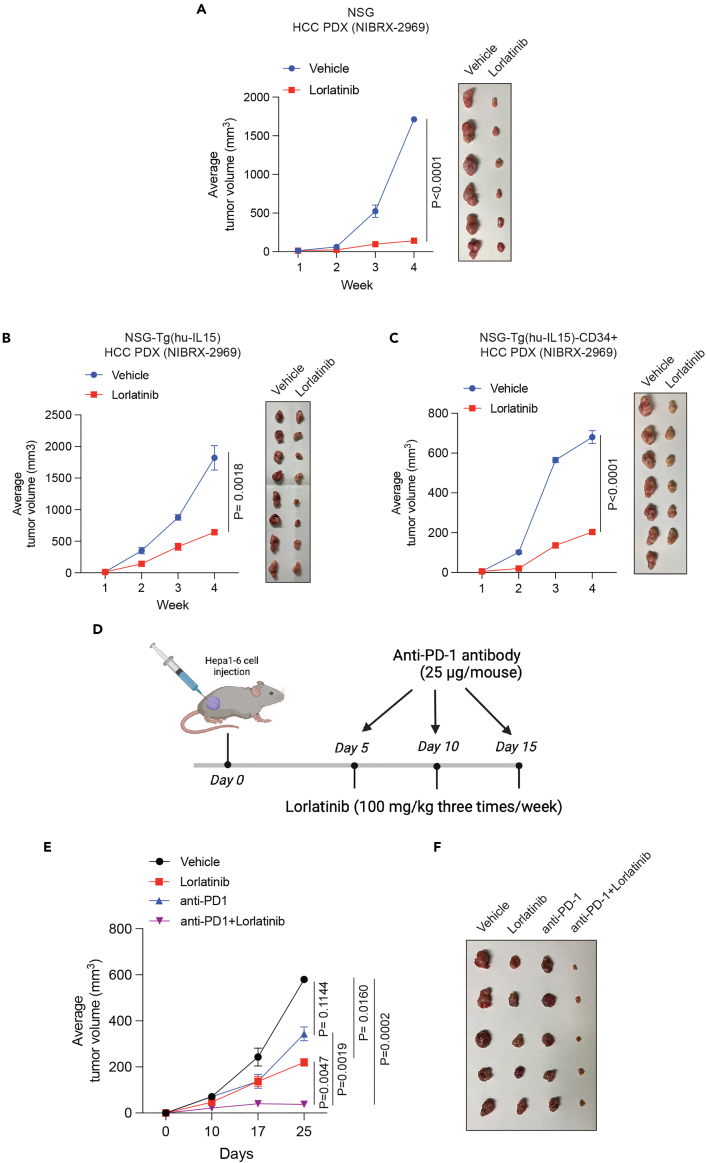

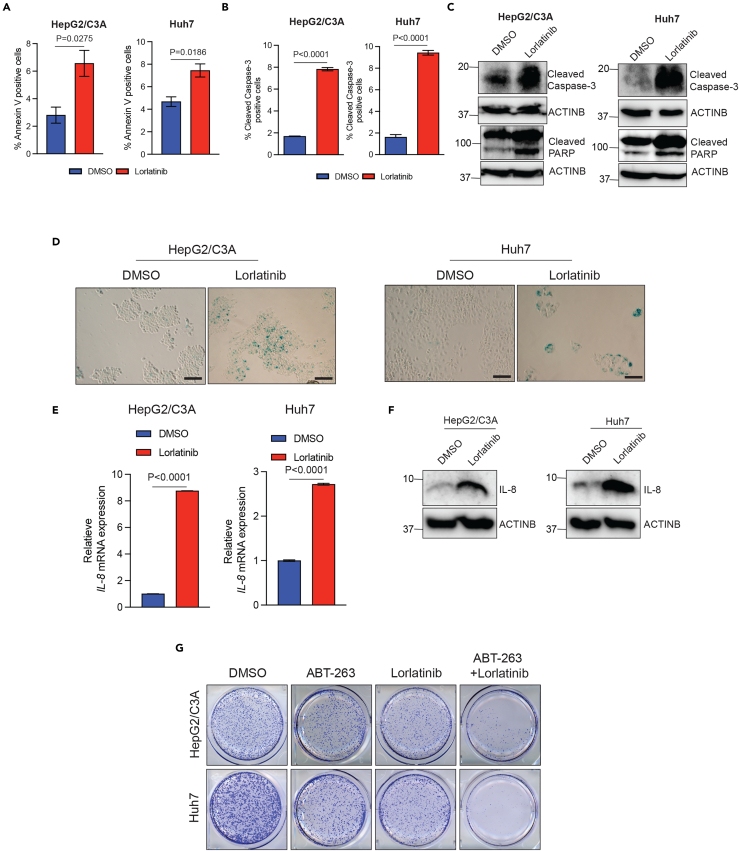

Lorlatinib-mediated ALK inhibition results in apoptosis and senescence induction, and a senolytic agent enhances the efficacy of lorlatinib against HCC cells

Previous studies have shown that apoptosis induction and senescence induction can confer tumor-suppressive effects.22,23 Therefore, we asked if lorlatinib treatment results in apoptosis and senescence induction in HCC cells. First, we tested the ability of lorlatinib in inducing apoptosis in HCC cells. To test this, we treated HCC cells (Huh7 and HepG2/C3A) with lorlatinib and performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based annexin V-staining and FACS-based cleaved caspase-3 staining as well as measured cleaved caspsase-3 and cleaved Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP). Collectively, based on these assays, we found that lorlatinib-treated cells compared to the DMSO-treated cells showed signs of apoptosis induction, as observed by increased % of annexin V-positive cells (Figure 5A), % cleaved caspase-3-positive cells (Figure 5B), and elevated levels of cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP in Huh7 and HepG2/C3A cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Lorlatinib-mediated ALK pathway inhibition results in apoptosis and senescence induction, and the senolytic agent ABT-263 enhance the efficacy of lorlatinib against HCC cells

(A) HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells were treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO for 96 h and then analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based annexin V-PE staining to analyze the apoptotic rates. For HepG2/C3A, p = 0.0275 (DMSO versus lorlatinib (n = 3 each)), t = 3.391837, df = 4. For Huh7, p = 0.0186 (DMSO versus lorlatinib (n = 3 each)), t = 3.830, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(B) HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells were treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO for 96 h and then analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based cleaved caspase-3 staining. For HepG2/C3A, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib (n = 3 each)), t = 39.89, df = 4. For Huh7, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib (n = 3 each)), t = 24.36, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(C) HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells were treated with lorlatinib or DMSO for 96 h and then analyzed for cleaved-caspase3 and cleaved PARP. ACTINB was used as a loading control.

(D) HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells were treated with lorlatinib or DMSO for 96 h and then analyzed for senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay (SA β-gal). Representative images for HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells treated with either lorlatinib or DMSO. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(E) HepG2/C3A, Huh7 cells treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO and IL-8 gene expression was analyzed using RT-qPCR. ACTINB mRNA expression was used as an internal normalization control. Relative IL-8 mRNA expression is plotted. For HepG2/C3A, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib (n = 3 each)), t = 974.0, df = 4. For Huh7, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib (n = 3 each)), t = 67.71, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(F) HepG2/C3A, Huh7cells treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO and IL-8 protein expression was analyzed using immunoblotting. ACTINB was used as a loading control.

(G) HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells were treated with DMSO, lorlatinib, ABT-263, or both lorlatinib and ABT-263, and clonogenic assay was performed. Representative wells for the HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells under the indicated treatment conditions are shown. All quantitative data represent the mean ± SEM.

Next, we asked if lorlatinib treatment of HCC cells also results in senescence induction. To test this, we performed a senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-gal) assay and measured the expression of IL-8 as a marker of senescence induction. Previous studies have shown that the presence of SA β-gal-positive cells and increased IL-8 levels can be used as reliable markers of measuring cellular senescence induction.24,25 We found that lorlatinib-treated HCC cells showed higher instances of SA β-gal-positive cells (Figure 5D) and increased expression of IL-8 (Figures 5E and 5F). These results demonstrate that lorlatinib induces cellular senescence in HCC cells. Previous studies have shown that although senescent cells cease to divide but do not die and secrete factors that can dampen the efficacy of anti-cancer drugs.26 Therefore, senolytic agents are developed as a new class of drugs to selectively eliminate senescent cells.27,28 Thus, based on our findings and the previous literature, we asked if eradicating the senescent cells following lorlatinib treatment can further enhance the efficacy of lorlatinib in suppressing HCC cells. To test this likelihood, we treated the HCC cells with either the senolytic agent ABT-263 or lorlatinib, or both ABT-263 and lorlatinib. ABT-263 has been shown to eradicate senescent cells.27 We found that ABT-263 significantly enhanced the efficacy of lorlatinib, as observed by much higher ability of this combination to suppress HCC growth in a clonogenic assay (Figure 5G). Collectively, these results demonstrate that lorlatinib-mediated ALK pathway inhibition results in apoptosis and senescence induction, and senolytic agents can enhance the efficacy of lorlatinib in suppressing HCC cell growth.

GGN upregulation and NRG4 downregulation following ALK inhibition in part mediated the HCC-suppressive effects of lorlatinib

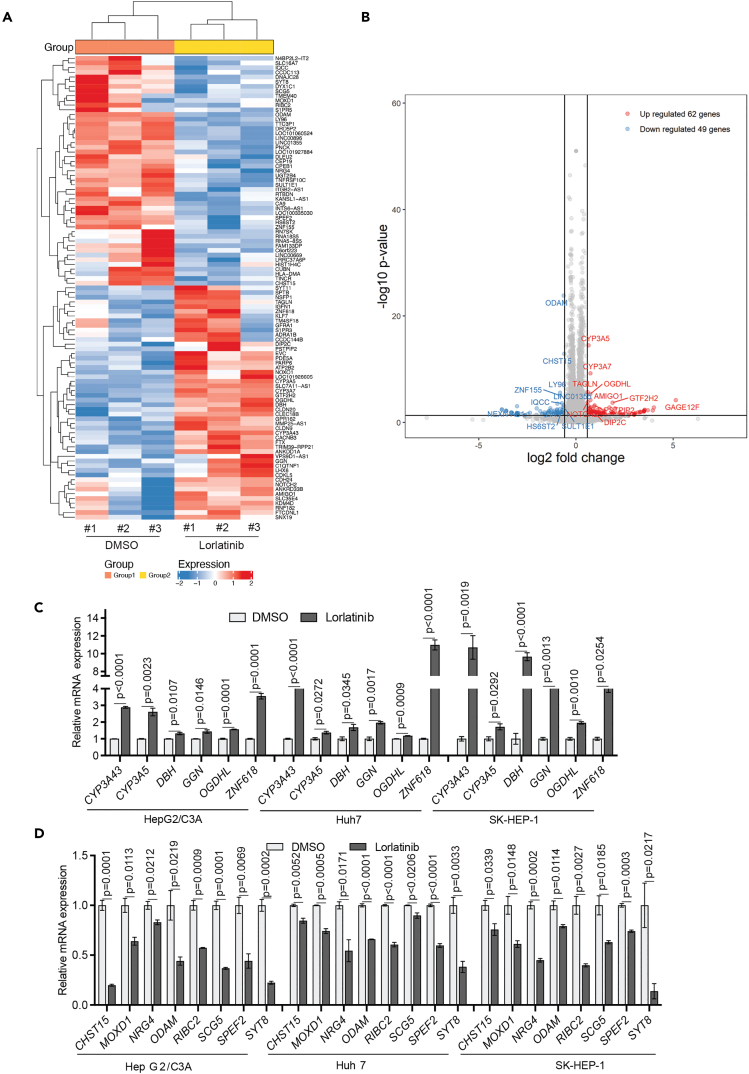

Next, we aimed to determine the mechanism by which ALK inhibition attenuated HCC growth. To do so, we performed RNA-seq to identify mRNAs whose expression was altered as a result of ALK inhibition in HCC cells. We treated the HCC cell line HepG2/C3A with lorlatinib or DMSO and performed RNA-seq analysis. We found that in lorlatinib-treated HepG2/C3A cells, mRNAs for 62 genes were upregulated while mRNAs for 49 genes were downregulated compared to the DMSO-treated HCC cells (Figures 6A and 6B; Table S1). Next, we investigated how many of these genes were commonly differentially expressed following lorlatinib treatment in other HCC cell lines. To test this, we treated two additional HCC cell lines (Huh7 and SK-HEP-1) with either lorlatinib or DMSO and measured the expression of all mRNAs for 62 upregulated genes and 49 downregulated genes. We found that 6 out of 62 genes were commonly upregulated, whereas 8 out of 49 genes were commonly downregulated following lorlatinib treatment in all three HCC cell lines (HepG2/C3A, Huh7, and SK-HEP-1) (Figures 6C, 6D, S3, and S4).

Figure 6.

Transcriptome-wide mRNA expression profiling identifies Lorlatinib-responsive gene signature in HCC cells

(A and B) HepG2/C3A cells were treated with either DMSO, or 1 μM lorlatinib for 24 h, after which RNA sequencing was performed. Heatmap (A) showing the top 100 most differentially regulated genes in lorlatinib treatment compared to DMSO treatment is shown. Volcano plot (B) showing differentially expressed genes in lorlatinib compared to DMSO-treated HepG2/C3A cells.

(C) mRNA expression for indicated genes that were identified to be upregulated from RNA-seq measured by RT-qPCR in HepG2/C3A, Huh7, and SK-HEP-1 cells after treatment with lorlatinib compared to cells treated with DMSO. ACTINB mRNA expression was used as an internal normalization control. Relative mRNA expression (n = 3 each) for indicated genes is plotted. For HepG2/C3A for CYP3A43 gene p < 0.0001, t = 36.71, df = 4, CYP3A5 gene p = 0.0023, t = 6.907, df = 4, DBH gene p = 0.0107, t = 4.516, df = 4, GGN gene p = 0.0146, t = 4.120, df = 4, OGDHL gene p = 0.0001, t = 14.57, df = 4, ZNF618 gene p = 0.0001, t = 15.25, df = 4. For Huh7 for CYP3A43 gene p < 0.0001, t = 18.40, df = 4, CYP3A5 gene p = 0.0272, t = 3.403, df = 4, DBH gene p = 0.0345, t = 3.150, df = 4, GGN gene p = 0.0017, t = 7.508, df = 4, OGDHL gene p = 0.0009, t = 8.744, df = 4, ZNF618 gene p < 0.0001, t = 17.81, df = 4. For SK-HEP-1 for CYP3A43 gene p = 0.0019, t = 7.315, df = 4, CYP3A5 gene p = 0.0292, t = 3.328, df = 4, DBH gene p < 0.0001, t = 15.66, df = 4, GGN gene p = 0.0013, t = 8.063, df = 4, OGDHL gene p = 0.0010, t = 8.518, df = 4, ZNF618 gene p = 0.0254, t = 3.477, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(D) mRNA expression for indicated genes that were identified to be downregulated from RNA-seq measured by RT-qPCR in HepG2/C3A, Huh7, and SK-HEP-1 cells after treatment with lorlatinib compared to cells treated with DMSO. ACTINB mRNA expression was used as an internal normalization control. Relative mRNA expression (n = 3 each) for indicated genes is plotted. For HepG2/C3A for CHST15 gene p = 0.0001, t = 15.54, df = 4, MOXD1 gene p = 0.0113, t = 4.448, df = 4, NRG4 gene p = 0.0212, t = 3.683, df = 4, ODAM gene p = 0.0219, t = 3.646, df = 4, RIBC2 gene p = 0.0009, t = 8.759, df = 4, SCG5 gene p = 0.0001, t = 14.89, df = 4, SPEF2 gene p = 0.0069, t = 5.120, df = 4, SYT8 gene p = 0.0002, t = 12.73, df = 4. For Huh7 for CHST15 gene p = 0.0052, t = 5.548, df = 4, MOXD1 gene p = 0.0005, t = 10.59, df = 4, NRG4 gene p = 0.0171, t = 3.930, df = 4, ODAM gene p < 0.0001, t = 22.11, df = 4, RIBC2 gene p < 0001, t = 16.45, df = 4, SCG5 gene p = 0.0206, t = 3.711, df = 4, SPEF2 gene p < 0.0001, t = 17.52, df = 4, SYT8 gene p = 0.0033, t = 6.274, df = 4. For SK-HEP-1 for CHST15 gene p = 0.0339, t = 3.167, df = 4, MOXD1 gene p = 0.0148, t = 4.103, df = 4, NRG4 gene p = 0.0002, t = 13.78, df = 4, ODAM gene p = 0.0114, t = 4.438, df = 4, RIBC2 gene p = 0.0027, t = 6.639, df = 4, SCG5 gene p = 0.0185, t = 3.838, df = 4, SPEF2 gene p = 0.0003, t = 11.80, df = 4, SYT8 gene p = 0.0217, t = 3.654, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test. All quantitative data represent the mean ± SEM; see also, Figures S3 and S4 and Table S1.

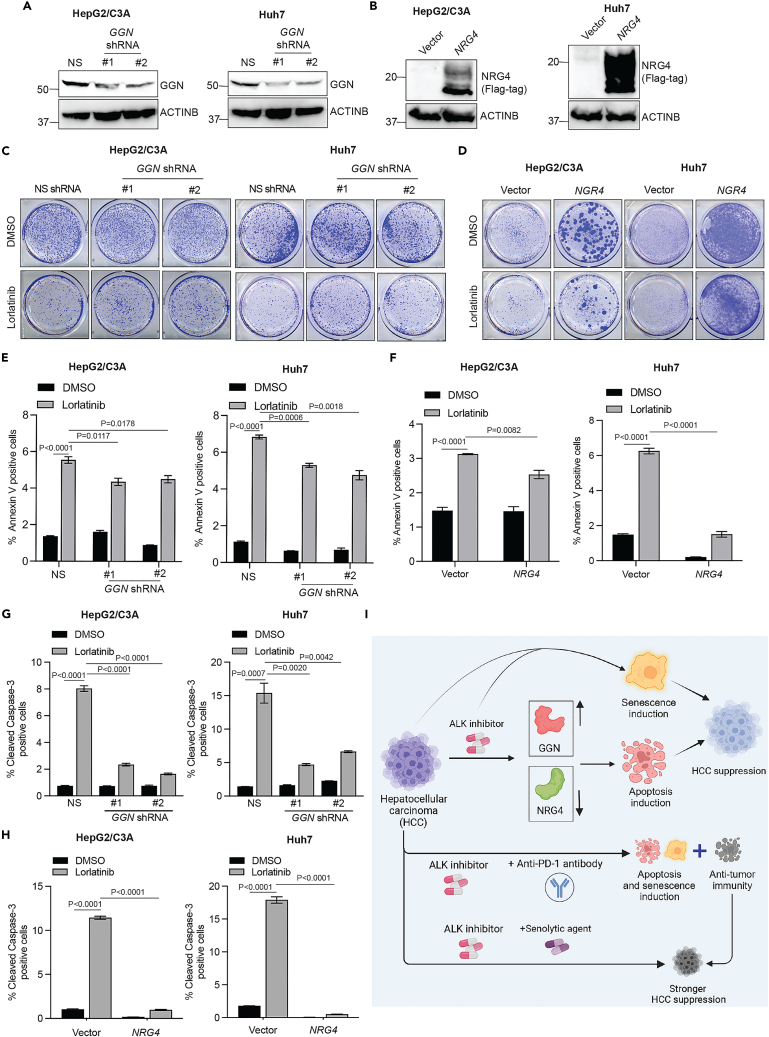

Based on this, we tested the role of these ALK target genes in mediating the HCC-suppressive effect of lorlatinib in HCC cell lines. To test this hypothesis, we knocked down the genes using short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) in HCC cells that were upregulated following lorlatinib treatment (Figure S5) or ectopically expressed the genes using gene-specific open reading frames (ORFs) in HCC cells that were downregulated following lorlatinib treatment (Figure S6). We then examined whether these genes, in part, mediated the HCC-suppressive effect of lorlatinib. To determine this, shRNA- or ORF-expressing HCC cells were treated with either DMSO or lorlatinib, and clonogenic assays were performed. We found that the knockdown of GGN and the ectopic expression of NRG4 conferred resistance to lorlatinib in Huh7 and HepG2/C3A cell lines (Figures 7A–7D), suggesting that GGN and NRG4 in part mediated the HCC-suppressive effect of ALK inhibitors, whereas ectopic expression of RIBC2, MOXD1, SCG5, CHST15, and SYT8 and knockdown of ZNF618, DBH, CYP3A5, CYP3A43, and OGDHL had no significant effect on lorlatinib-mediated HCC suppression when tested in multiple HCC cell lines (Figures S7 and S8). ODAM was not tested because we were unable to ectopically express it even after multiple attempts. To ascertain whether GGN knockdown- or NRG4 ectopic expression-mediated resistance is specific to the ALK inhibitor lorlatinib, we treated HCC cells with GGN knockdown or NRG4 ectopic expression with the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin. We found that GGN knockdown or NRG4 ectopic expression in HCC cells did not cause resistance to doxorubicin, suggesting that GGN- and NRG4-mediated effects were specific to the ALK inhibitor lorlatinib in HCC (Figure S9).

Figure 7.

GGN upregulation and NRG4 downregulation following ALK inhibition in part mediated the HCC-suppressive effects of lorlatinib

(A) Indicated HCC cell lines expressing either non-specific shRNA or GGN-specific shRNAs were analyzed for GGN protein expression using immunoblotting. ACTINB was used as a loading control.

(B) Indicated HCC cell lines expressing either empty vector or NRG4 ORF were analyzed for NRG4 protein expression using immunoblotting. ACTINB was used as a loading control.

(C) HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells expressing an NS or GGN shRNAs were treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO, and survival was measured in clonogenic assays. Representative wells for cells grown under the indicated conditions are shown.

(D) HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells expressing empty vector or NRG4 ORFs were treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO, and survival was measured in clonogenic assays. Representative wells for cells grown under the indicated conditions are shown.

(E) HepG2/C3A or Huh7 cells expressing either NS- or GGN-specific shRNAs were treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO for 96 h and then analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based annexin V-PE staining and analyzed apoptotic rates. For HepG2/C3A cells, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib for Non-specific (NS) shRNA expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 23.02, df = 4, p = 0.0117 (lorlatinib/NS shRNA versus lorlatinib/GGN shRNA#1 (n = 3 each)), t = 4.396, df = 4 and p = 0.0178 (lorlatinib/NS shRNA versus lorlatinib/GGN shRNA#2 (n = 3 each)), t = 3.3884, df = 4. For Huh7 cells, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib for NS shRNA expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 46.98.02, df = 4, p = 0.0006 (lorlatinib/NS shRNA versus lorlatinib/GGN shRNA#1 (n = 3 each)), t = 9.986, df = 4 and p = 0.0018 (lorlatinib/NS shRNA versus lorlatinib/GGN shRNA#2 (n = 3 each)), t = 7.402, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(F) HepG2/C3A or Huh7 cells expressing either empty vector or NRG4 ORF were treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO for 96 h and then analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based annexin V-PE staining and analyzed apoptotic rates. For HepG2/C3A cells, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib for vector expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 17.11, df = 4 and p = 0.0082 (lorlatinib/vector versus lorlatinib/NRG4 expressing cells (n = 3 each)), t = 4.870, df = 4. For Huh7 cells, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib for vector expressing cells (n = 3 each)), t = 28.29, df = 4 and p < 0.0001 (lorlatinib/vector versus lorlatinib/NRG4 expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 20.95, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(G) HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells expressing either NS- or GGN-specific shRNAs were treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO for 96 h and then analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based cleaved caspase-3 staining. For HepG2/C3A cells, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus Lorlatinib for NS shRNA expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 34.99, df = 4, p < 0.0001 (lorlatinib/NS shRNA versus lorlatinib/GGN shRNA#1 (n = 3 each), t = 24.80, df = 4 and p < 0.0001 (lorlatinib/NS shRNA versus lorlatinib/GGN shRNA#2 (n = 3 each), t = 29.88, df = 4. For Huh7 cells, p = 0.007 (DMSO versus lorlatinib for NS shRNA expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 9.402.02, df = 4, p = 0.0020 (lorlatinib/NS shRNA versus lorlatinib/GGN shRNA#1 (n = 3 each), t = 7.162, df = 4 and p = 0.0042 (lorlatinib/NS shRNA versus lorlatinib/GGN shRNA#2 (n = 3 each), t = 5.870, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

(H) HepG2/C3A and Huh7 cells expressing either empty vector or NRG4 ORF were treated with lorlatinib (10 μM) or DMSO for 96 h and then analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based cleaved caspase-3 staining. For HepG2/C3A cells, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib for vector expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 55.14, df = 4 and p < 0.0001 (lorlatinib/vector versus lorlatinib/NRG4 expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 56.39, df = 4. For Huh7 cells, p < 0.0001 (DMSO versus lorlatinib for vector expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 32.60, df = 4 and p < 0.0001 (lorlatinib/vector versus lorlatinib/NRG4 expressing cells (n = 3 each), t = 35.22, df = 4. p values were calculated using a two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test.

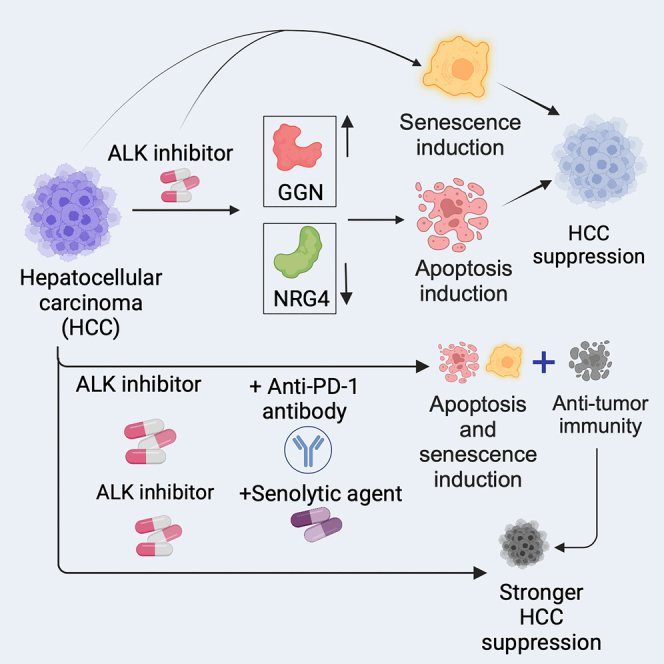

(I) Model (generated using BioRender): Our results demonstrate that ALK inhibition blocks HCC tumor growth and progression by inducing apoptosis and senescence and apoptosis-inducing effect of ALK inhibition is in part mediated through GGN and NRG4. Lorlatinib also enhance the therapeutic benefits of anti-PD-1 antibody and senolytic agents resulting in more potent inhibition of HCC. All quantitative data represent the mean ± SEM. See also, Figures S5–S10.

Next, we investigated whether GGN knockdown or NRG4 overexpression reversed the apoptosis or senescence-inducing effects of lorlatinib in HCC cells. To test this possibility, we measured the number of annexin V-positive and cleaved caspase-3-positive cells for apoptosis induction and SA β-gal cells in GGN-knockdown and NRG4-overexpressing cells following lorlatinib treatment. We found that GGN knockdown or NRG4 overexpression in HCC cells (Huh7 and HepG2/C3A) significantly suppressed lorlatinib-induced apoptosis (Figures 7E–7H) with no significant effect on senescence phenotype (Figure S10). Collectively, these results demonstrate that lorlatinib suppresses HCC tumor growth by inducing apoptosis, in part by regulating GGN and NRG4 expression.

Discussion

HCC is a significant cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. However, the current therapies are limited in their effectiveness. Through a comprehensive series of experiments utilizing both cell culture and in vivo models, we demonstrated the efficacy of ALK inhibitors for HCC treatment (Figure 7I). The pivotal role of ALK in oncogenesis has been well established in previous studies.10,11,16,29 The development and approval of highly efficacious ALK inhibitors for the treatment of ALK-positive cancers and their clinical success underline the significance of ALK as a therapeutic target.15 A previous study showed that HCC exhibited ALK gene amplification, which was associated with significantly poor overall survival.14 However, the utility of ALK inhibitors for HCC treatment remains unknown. Our study revealed that the ALK inhibitors (ceritinib and lorlatinib) effectively suppressed HCC cell proliferation and metastatic attributes, highlighting their potential as HCC treatment agents. This was further corroborated by genetic knockout experiments, which reinforced the notion that ALK is necessary for HCC growth. Similar to our study, another study showed that ALK inhibitor can suppress HCC growth;30 however, the authors did not perform any in vivo studies. Our investigations involving a series of orthotopic and metastatic mouse models as well as a PDX, which inherently maintains the complexity of the tumor microenvironment,31,32 validated the efficacy of lorlatinib in blocking HCC tumor growth and metastasis. Importantly, using a humanized mouse model with a human immune system, we established that the HCC-suppressive effect of lorlatinib was not contingent on the host immune system, thereby indicating a predominantly cell-intrinsic mechanism of action. The potential use of combinatorial therapies in cancer treatment prompted us to test lorlatinib in combination with the anti-PD-1 antibody in a mouse model. Predictably, the combination of lorlatinib and anti-PD-1 antibody exhibited superior efficacy in suppressing HCC tumor growth compared with either treatment alone. This strategic integration of a cell-intrinsic pathway blockade with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (cell-extrinsic pathway) provides a promising avenue for enhancing the therapeutic efficacy in HCC. HCC patients are now being treated with atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1 antibody) and bevacizumab (anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor (VEGFR) antibody) in clinic,33,34,35 and these agents show benefits in some patients.33,34,35 Therefore, it is likely that the addition of ALK inhibitors, such as lorlatinib, with atezolizumab/bevacizumab will further enhance their therapeutic benefits in HCC patients.

Furthermore, we found that ALK inhibition by lorlatinib resulted in both apoptosis and senescence induction, which provides a mechanism for the HCC-suppressive effect of ALK inhibitors, such as lorlatinib. Notably, we found that eradication of senescent cells using the senolytic agent ABT-263 enhanced the efficacy of lorlatinib. Senolytic agents are a class of drugs designed to selectively target and eliminate senescent cells.27,28 Senescent cells secrete inflammatory and cancer-promoting factors.26 Recent studies have documented promising results in various cancer models, showcasing the potential clinical value of these agents in combination with other previously approved anti-cancer drugs.27,28

Additionally, to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the suppressive effects of lorlatinib on HCC-suppressive effects, we conducted RNA-seq analysis following ALK inhibition. Our results highlight the key gene expression changes induced by lorlatinib treatment. Among these, NRG4 and GGN have emerged as potential mediators of the HCC-suppressive effect of lorlatinib. NRG4 encodes for neuregulin 4, which functions as a ligand for ERBB4.36,37 NRG4 signaling has been implicated in various physiological processes, including metabolism, heart function, neural development, and cancer.38,39,40 In particular, NRG4 has been implicated in prostate, breast, and bladder cancer.41,42,43 We showed that lorlatinib-treated cells exhibited reduced NRG4 expression, and ectopic expression of NRG4 in part restored HCC growth after lorlatinib treatment by suppressing lorlatinib-induced apoptosis. In addition to NRG4, we identified that lorlatinib treatment resulted in the upregulation of GGN. GGN has been shown to play a role in meiosis by involving in DNA double-strand break repair as well as sperm tail development and/or motility in the testis.44 GGN was also found to play a tumor-promoting role in bladder and colon cancers by regulating the cell cycle and apoptosis.45,46 We showed that knockdown of GGN partly restored HCC growth following ALK inhibition by suppressing lorlatinib-induced apoptosis. In conclusion, this study provides evidence for the therapeutic potential of ALK inhibition in HCC treatment. Our results highlight the significant impact of lorlatinib on HCC tumor growth and metastasis, both in vitro and in vivo, providing a strong rationale for further exploration of ALK-targeted therapies in clinical settings. The elucidation of specific gene modulations that contribute to the effect of lorlatinib provides a more comprehensive view of its mechanism of action, which could inform the development of combinatorial strategies to enhance therapeutic outcomes. Our study also underscores the important interplay between tumor-intrinsic and tumor-extrinsic (immune checkpoint modulation) pathways and their combinatorial targeting as a promising avenue for advancing HCC treatment strategies.

Limitations of the study

Although we demonstrate that ALK inhibitors, either alone or in combination with other agents, exhibit significant anti-HCC effects in pre-clinical settings, the inherent complexity of HCC—stemming from its varied etiology—renders it challenging to discern which patient subsets will most benefit from such treatments. Employing etiology-specific mouse models (for instance, models of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH)driven HCC) might provide a pathway to address this ambiguity. Moreover, the necessity for future research to pinpoint biomarkers predictive of a response to ALK inhibitors becomes evident, as ALK does not undergo mutation or translocation in HCC, unlike in other cancers. Determining whether ALK amplification alone suffices to forecast HCC patient outcomes to ALK inhibitor therapy, or if additional, HCC-specific factors modulate this response, remains to be resolved.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| ACTINB | Cell signaling | Cat# 4970; RRID: AB_2223172 |

| p-ALK (Tyr1278) | Cell Signaling | Cat# 6941; RRID: AB_10860598 |

| ALK | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-398791; RRID: AB_2889357 |

| p-AKT (Ser473) | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9271; RRID: AB_329825 |

| AKT | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9272; RRID: AB_329827 |

| V5-Tag | Cell Signaling | Cat# 13202; RRID: AB_2687461 |

| anti-mouse PD-1 | BioXcell | Cat#BE0146; RRID: AB_10949053 |

| Cleaved Caspase-3 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9664; RRID: AB_2070042 |

| Cleaved Caspase-3 (Alexa Fluor 647 Conjugate) [Flow cytometry] | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9602; RRID: AB_2687881 |

| Cleaved PARP | Cell Signaling | Cat# 5625; RRID: AB_10699459 |

| GGN | Bioss | Cat#BS-13347R |

| IL-8 | Cell signaling | Cat#94407; RRID: AB_3075425 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| DMEM | GIBCO | Cat# 11965-092 |

| RPMI | GIBCO | Cat# 11875-093 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | GIBCO | Cat# 10437-028 |

| Trypsin-EDTA | GIBCO | Cat# 25200-056 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | GIBCO | Cat# 15140-122 |

| Effectene Transfection Reagent | QIAGEN | Cat# 301427 |

| Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix | Corning | Cat# 356237 |

| Lorlatinib | Medchem express | Cat# HY-12215 |

| Ceritinib | Cayman Chemical | Cat# 19374 |

| Doxorubicin | Selleckchem | Cat# S1208 |

| ABT-263 | Selleckchem | Cat#S1001 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Annexin V staining Flow Cytometry kit | BD Pharmingen | Cat# 559763 |

| Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9860 |

| CytoSelect 96-well Cell Transformation Assay (Soft Agar Colony Formation), 96 wells | Cell Biolabs,Inc | Cat# CBA-130 |

| Deposited data | ||

| RNA-Seq performed with HepG2/C3A cells treated with either DMSO or lorlatinib | This paper | GEO:GSE178211 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines/organoids/PDXs | ||

| 293T | ATCC | ATCC CRL-3216 |

| HepG2/C3A | ATCC | ATCC CRL-10741 |

| Huh7 | Sigma-Aldrich | 01042712 |

| SK-HEP-1 | ATCC | ATCC HTB-52 |

| Hepa 1-6 | ATCC | ATCC CRL-1830 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: NSG | Jackson Laboratory | Stock No. 005557 |

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratory | Stock No: 000664 |

| Mouse: NOD.Cg-Prkdc<scid> Il2rg<tm1Wjl> Tg(IL15)1Sz/SzJ M03 Homozygous for Prkdc<scid> Hemizygous for Il2rg<tm1Wjl> Homozygous for Tg(IL15)1Sz |

Jackson Laboratory | Stock No: 030890 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| CYP3A5 shRNA#1 | TRCN0000064233 | |

| CYP3A5 shRNA#2 | TRCN0000064234 | |

| CYP3A43 shRNA#1 | TRCN0000064255 | |

| CYP3A43 shRNA#2 | TRCN0000064256 | |

| DBH shRNA#1 | TRCN0000078120 | |

| DBH shRNA#2 | TRCN0000078122 | |

| ZNF618 shRNA#1 | TRCN0000138191 | |

| ZNF618 shRNA#2 | TRCN0000138008 | |

| OGDHL shRNA#1 | TRCN0000036729 | |

| OGDHL shRNA#2 | TRCN0000036732 | |

| GGN shRNA#1 | V2LHS_43576 | |

| GGN shRNA#2 | V3LHS_345420 | |

| ACTINB qPCR Forward primer | gtcttcccctccatcgtggg | |

| ACTINB qPCR Reverse primer | cctctcttgctctgggcctc | |

| hDNAAF4 qPCR Forward primer | agaagcggccatgtgggaga | |

| hDNAAF4 qPCR Reverse primer | cttcccgctttgctgcagct | |

| hCPEB1 qPCR Forward primer | tgctgcagtcactccctccc | |

| hCPEB1 qPCR Reverse primer | gtgcagcctggcctctctct | |

| hRIBC2 qPCR Forward primer | cgagacctggactgggaccg | |

| hRIBC2 qPCR Reverse primer | cttggccaggctgaggttgc | |

| hTNFRSF10C qPCR Forward primer | cggcaggaggaagttcccca | |

| hTNFRSF10C qPCR Reverse primer | tgcacgggttacaggctcca | |

| hCCDC113 qPCR Forward primer | tcgctgcaacctcctcctcc | |

| hCCDC113 qPCR Reverse primer | ccagcctggccaacatggtg | |

| hSPEF2 qPCR Forward primer | aggcttggttcctggcgagt | |

| hSPEF2 qPCR Reverse primer | ctcacggtccgggacacctt | |

| hCA9 qPCR Forward primer | gaaggccaccgtttccctgc | |

| hCA9 qPCR Reverse primer | tcctccagaaaggcggccaa | |

| hDRD5P2 qPCR Forward primer | gcctgcctgctgaccctact | |

| hDRD5P2 qPCR Reverse primer | ttggtcatcttggcgcgcag | |

| hNRG4 qPCR Forward primer | agccctgtggtcccagtcac | |

| hNRG4 qPCR Reverse primer | tggatgctggagcctgggag | |

| hRTBDN qPCR Forward primer | cccagcaacaccatgggctg | |

| hRTBDN qPCR Reverse primer | tggtttccagggcccgatgt | |

| hLY96 qPCR Forward primer | tgcagagctctgaagggagagac | |

| hLY96 qPCR Reverse primer | agcatttcttctgggctccca | |

| hCUBN qPCR Forward primer | tgcccacctgagacgtacgg | |

| hCUBN qPCR Reverse primer | cccagcatcacagacgcagc | |

| hZNF225 qPCR Forward primer | ggtcagttccgcgagaccct | |

| hZNF225 qPCR Reverse primer | tgcctctgctctccgacgag | |

| hMOXD1 qPCR Forward primer | gaccagtcacgacctggcct | |

| hMOXD1 qPCR Reverse primer | tcactggcaggctgaggacc | |

| hSCG5 qPCR Forward primer | gccaggccccgagtggaata | |

| hSCG5 qPCR Reverse primer | actctgccacgatgttgggga | |

| hHLA-DMA qPCR Forward primer | gttggggaagctgggttggc | |

| hHLA-DMA qPCR Reverse primer | ggagtggggtagcagccaca | |

| hIQCC qPCR Forward primer | aagctgggacccacggactc | |

| hIQCC qPCR Reverse primer | ctcagctcgcaggctctgga | |

| hSLC16A7 qPCR Forward primer | cctccttctccgctggctgt | |

| hSLC16A7 qPCR Reverse primer | gccctccgttcccagcaaac | |

| hPNCK qPCR Forward primer | acgagatcgcagtgctccgt | |

| hPNCK qPCR Reverse primer | atgcggtcaaacagctcgcc | |

| hHS6ST2 qPCR Forward primer | gctctccgacctgaccctgg | |

| hHS6ST2 qPCR Reverse primer | gccgaagaacgccatgtgct | |

| hS1PR5 qPCR Forward primer | tacgccaaggcctacgtgct | |

| hS1PR5 qPCR Reverse primer | caaaggccaggagcaccacg | |

| hH4C3 qPCR Forward primer | tcgagacgccgtcacctatacg | |

| hH4C3 qPCR Reverse primer | agccgccgaagccatacaga | |

| hSYT8 qPCR Forward primer | tgcacctttagcccaggcct | |

| hSYT8 qPCR Reverse primer | ggtttgccagccatgcaggt | |

| hODAM qPCR Forward primer | acacaaccaggccccagtca | |

| hODAM qPCR Reverse primer | tgctgaggttgttcccagggt | |

| hTMEM40 qPCR Forward primer | acgcacaggagaccaagcca | |

| hTMEM40 qPCR Reverse primer | acacccaccctctgccttcc | |

| hCEP19 qPCR Forward primer | cgctgtggaaaccgctaggc | |

| hCEP19 qPCR Reverse primer | gcccgaaccctcaaacaccg | |

| hCHST15 qPCR Forward primer | tcaaggactgcaggccagct | |

| hCHST15 qPCR Reverse primer | gtcagaaacggtggctcgcc | |

| hDNAJC28 qPCR Forward primer | ggggtctcaggagctccgtt | |

| hDNAJC28 qPCR Reverse primer | tgtgaggcctcccaacacgt | |

| hSULT1E1 qPCR Forward primer | agcgttccaggcaagaccaga | |

| hSULT1E1 qPCR Reverse primer | tgcacttttccacatcaccctct | |

| hUGT2B4 qPCR Forward primer | gactgggttcctgctggcct | |

| hUGT2B4 qPCR Reverse primer | gggtttcccagcttccagcc | |

| hTRIM39 qPCR Forward primer | atgaggccggcacactgtct | |

| hTRIM39 qPCR Reverse primer | ccagcaggacacgggaagga | |

| hGTF2H2 qPCR Forward primer | gcatggcgcatttggatggc | |

| hGTF2H2 qPCR Reverse primer | tgccaagtggggagcagaca | |

| hADRA1B qPCR Forward primer | acactgccccagctggacat | |

| hADRA1B qPCR Reverse primer | agcacaggacatccacggct | |

| hCYP3A43 qPCR Forward primer | tgcacagcccagcaaagagc | |

| hCYP3A43 qPCR Reverse primer | tggcccaggaattcccagct | |

| hFONG qPCR Forward primer | tgcatgttcctggctgcagc | |

| hFONG qPCR Reverse primer | cctcctcgtgaaccagccca | |

| hS1PR3 qPCR Forward primer | cctgctctgcggctgtgttc | |

| hS1PR3 qPCR Reverse primer | atccacactgggcaggctgt | |

| hCLDN20 qPCR Forward primer | tggaacgcaggaggacaggg | |

| hCLDN20 qPCR Reverse primer | acctcgaggcccgtgatgtc | |

| hZNF618 qPCR Forward primer | cctcagacctgccacagcct | |

| hZNF618 qPCR Reverse primer | accatgctcactgccgtcct | |

| hTM4SF18 qPCR Forward primer | gctctgtgccaaagccaggg | |

| hTM4SF18 qPCR Reverse primer | tgggcccagagcatgaaggt | |

| hLHX6 qPCR Forward primer | ggtgaggagttcggcctggt | |

| hLHX6 qPCR Reverse primer | cagctgttccgcggtgaagg | |

| SPTB qPCR Forward primer | cctggaggggcccaacaaga | |

| SPTB qPCR Reverse primer | tccccagggccaggttcttg | |

| hPSTPIP2 qPCR Forward primer | agcctgagcccaacccacat | |

| hPSTPIP2 qPCR Reverse primer | gcaactcctcgaccccacct | |

| hKLF7 qPCR Forward primer | cgtggaagcggccatctgtg | |

| hKLF7 qPCR Reverse primer | cgttgagctgggcctggttg | |

| hCBLN3 qPCR Forward primer | caggtccagccctcagtgct | |

| hCBLN3 qPCR Reverse primer | tgtcccagctctgtcctgcc | |

| hGGN qPCR Forward primer | gcaacgtctctgcctggctg | |

| hGGN qPCR Reverse primer | ctgcaccctacccactgcct | |

| hPARP6 qPCR Forward primer | ggatcccctggcccatcctc | |

| hPARP6 qPCR Reverse primer | gcttcttggcggtccggaac | |

| hANKDD1A qPCR Forward primer | ggctgtgcgtctgcttctgg | |

| hANKDD1A qPCR Reverse primer | aggcagacaggagaagcgca | |

| hDBH qPCR Forward primer | ccgtggcgagcttgagaacg | |

| hDBH qPCR Reverse primer | gccttctggggtcctctgca | |

| hSNX19 qPCR Forward primer | gtccacttcaggtcggggct | |

| hSNX19 qPCR Reverse primer | ctggggcccacggacactta | |

| hRNF182 qPCR Forward primer | gtggaactgcacgtccctgc | |

| hRNF182 qPCR Reverse primer | gctcgaagggaccaggctga | |

| hGFRA1 qPCR Forward primer | acagggccctctgacagcag | |

| hGFRA1 qPCR Reverse primer | acgtggcccaggacttaccc | |

| hNOXO1 qPCR Forward primer | ggaccccacaggcttgaggt | |

| hNOXO1 qPCR Reverse primer | ccaactcctgcgcacgaagg | |

| hSLC35E4 qPCR Forward primer | agcctcactggtgcggatgt | |

| hSLC35E4 qPCR Reverse primer | ccacaccagtgctgccatgg | |

| hANKRD33B qPCR Forward primer | tcaccctcgtggccaaggag | |

| hANKRD33B qPCR Reverse primer | ctggctgggtcctcggttga | |

| hKLF2 qPCR Forward primer | ttggggcacttgggaggagg | |

| hKLF2 qPCR Reverse primer | cagctgtggggcaaagaggc | |

| hRGPD3 qPCR Forward primer | gaacctcaggacccgcccat | |

| hRGPD3 qPCR Reverse primer | cagcctcagcctccccaagt | |

| hCACNB3 qPCR Forward primer | gactcctacgtgcccgggtt | |

| hCACNB3 qPCR Reverse primer | ccctggactgggcactcctc | |

| hCLDN9 qPCR Forward primer | gcatgaccctggctgtgctg | |

| hCLDN9 qPCR Reverse primer | gcaccacgcaggacatccac | |

| hCDKL5 qPCR Forward primer | ctgcagacccaaagccagcc | |

| hCDKL5 qPCR Reverse primer | acatccaccgtctggcagct | |

| hCYP3A7 qPCR Forward primer | ggccgtggaaacctggcttc | |

| hCYP3A7 qPCR Reverse primer | cagaggtgtgggccctggaa | |

| hAMIGO1 qPCR Forward primer | tgagacacgtcctcgccgag | |

| hAMIGO1 qPCR Reverse primer | tgtcactggagtgggcgagg | |

| hOGDHL qPCR Forward primer | tccacactggcctctctcgc | |

| hOGDHL qPCR Reverse primer | tcctgcggtcaacctcctgg | |

| hKDM4D qPCR Forward primer | cgtggtcgccctcctcagaa | |

| hKDM4D qPCR Reverse primer | ggcccgaagctgtgcatgtt | |

| hIGFN1 qPCR Forward primer | atgcctggcgaggttttggc | |

| hIGFN1 qPCR Reverse primer | gggtccaggaggttcgctgt | |

| hGPR162 qPCR Forward primer | aacgcattgtcctggctggc | |

| hGPR162 qPCR Reverse primer | gaagcctgacgacgcagctg | |

| hLRRC73 qPCR Forward primer | ctctgcgaccgcgactttgg | |

| hLRRC73 qPCR Reverse primer | ctgggttcagcaaggccagc | |

| hCDH24 qPCR Forward primer | ggagacagctggacctggca | |

| hCDH24 qPCR Reverse primer | acgcacagaggccacatcct | |

| hCLEC18B qPCR Forward primer | ctgcacccactacacgcagc | |

| hCLEC18B qPCR Reverse primer | tgacctcccagttgcctccg | |

| hUPB1 qPCR Forward primer | aggcgggcagatcacaaggt | |

| hUPB1 qPCR Reverse primer | gtcgccaagctggagtgcag | |

| hATP2B2 qPCR Forward primer | tgcctgtggtgctctccctc | |

| hATP2B2 qPCR Reverse primer | cagtcacttcccagccccga | |

| hCYP3A5 qPCR Forward primer | ggcggtggaaacctggcttc | |

| hCYP3A5 qPCR Reverse primer | cagaggtgtgggccctggaa | |

| hZDHHC1 qPCR Forward primer | gcaacgtggatgtgagcgct | |

| hZDHHC1 qPCR Reverse primer | ggcaggcaggaacacgaacc | |

| hDIP2C qPCR Forward primer | caccaggaaggacgcaggga | |

| hDIP2C qPCR Reverse primer | acccagcacactgccatcct | |

| hC19orf84 qPCR Forward primer | ggagagcgtggcctctgtca | |

| hC19orf84 qPCR Reverse primer | tgcctgacttcccagcctcc | |

| hSYT11 qPCR Forward primer | cgggctggagtgcaatggtg | |

| hSYT11 qPCR Reverse primer | ccagcctggccaacatggtg | |

| hSLC22A4 qPCR Forward primer | gggaacgctccaacgccttc | |

| hSLC22A4 qPCR Reverse primer | tgtcttgtagctggggcgct | |

| hPDE5A qPCR Forward primer | cccgactggagcaggacgaa | |

| hPDE5A qPCR Reverse primer | tccagccatgcttcgaccga | |

| hSYT15 qPCR Forward primer | agctgtgctgggctccatca | |

| hSYT15 qPCR Reverse primer | caccagctccttgggcttgc | |

| hNOTCH2 qPCR Forward primer | tcctgccacctgtctgagcc | |

| hNOTCH2 qPCR Reverse primer | agttggcccaggggttctcc | |

| hEVC qPCR Forward primer | acactgatggaggcggcagt | |

| hEVC qPCR Reverse primer | gggaactgggccaggaacct | |

| hC1QTNF1 qPCR Forward primer | ggcctggtcctgagtcgtgt | |

| hIL8 qPCR Forward primer | aagctggccgtggctctctt | |

| hIL8 qPCR Reverse primer | ctgtgttggcgcagtgtggt | |

| NT sgRNAs sgRNA Forward primer | aaacccatcaggcggaagctttttc | |

| NT sgRNAs sgRNA Reverse primer | aaacccatcaggcggaagctttttc | |

| ALK sgRNAs sgRNA#1 Forward primer | caccgctgtagcactttcagaagcg | |

| ALK sgRNAs sgRNA#1 Reverse primer | aaaccgcttctgaaagtgctacagc | |

| ALK sgRNAs sgRNA#2 Forward primer | caccgtccagacaacccatttcgag | |

| ALK sgRNAs sgRNA#2 Reverse primer | aaacctcgaaatgggttgtctggac | |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid: piggyBac GFP-Luc | Ding et al.47 | N/A |

| Plasmid: Act-PBase | Ding et al.47 | N/A |

| Plasmid: psPAX2 | Addgene | Cat#12260, RRID:Addgene_12260 |

| Plasmid: pMD2.G | Addgene | Cat#12259, RRID:Addgene_12259 |

| Plasmid: pLX304-V5-BLAST | Addgene | Cat# 25890; RRID:Addgene_25890 |

| Plasmid: pLX304-SCG5-V5-BLAST | Horizon Discovery | Cat# OHS6085- 213579447 |

| Plasmid: pLX304-RIBC2-V5-BLAST | Horizon Discovery | Cat# OHS6085- 213584181 |

| Plasmid: pLX304-MOXD1-V5-BLAST | Horizon Discovery | Cat# OHS6085- 213580459 |

| Plasmid: pLX304-CHST15-V5-BLAST | Horizon Discovery | Cat# OHS6085-213575901 |

| Plasmid: pLenti-C-Myc-DDK-P2A-Puro-NRG4 | OriGene | Cat# RC204777L3 |

| Plasmid: pLenti-C-Myc-DDK-P2A-Puro-SYT8 | OriGene | Cat# RC214219L3 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism 9.0 | GraphPad | www.graphpad.com/scientificsoftware/prism |

| ImageJ | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij | N/A |

| FlowJo | BD Biosciences | https://www.flowjo.com/solutions/flowjo |

| Bowtie2 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml, RRID:SCR_016368 | |

| TopHat | http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml, RRID:SCR_013035 | |

| Cufflinks 2.2.1 | Cufflinks | http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/cuffmerge/, RRID:SCR_014597 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Narendra Wajapeyee (nwajapey@uab.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new animals, cell lines or unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

The data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession numbers GSE178211 (RNA-Seq performed with HepG2/C3A cells treated with either DMSO or lorlatinib)

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Cell culture

HepG2/C3A (RRID:CVCL_1098), SK-HEP-1 (RRID:CVCL_0525), Hepa1-6 (RRID:CVCL_0327), and HEK293T (RRID:CVCL_0063) cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Huh7 cells (RRID:CVCL_2957) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Huh7, HepG2/C3A, SK-HEP-1, Hepa1-6, and HEK293T cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. All provided cell lines were obtained with confirmed STR profiling status by ATCC and Sigma-Aldrich. Mycoplasma negative status of all cell lines was ensured using universal mycoplasma detection kit from ATCC (30-1012K).

Mouse tumorigenesis experiments

All protocols were approved by the UAB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol number 22012).

Mouse tumorigenesis experiment in the NSG mice using PDX

The HCC PDXs (NIBRX-2969) were obtained from the Dana Farber Cancer Center Novartis PDX Collection. Initially, the PDXs were expanded in NSG mice (stock no. 005557). After 5-6 weeks, the PDXs were harvested, and implanted into 5–6-week-old female NSG mice (stock no. 005557, Jackson Laboratory). In brief, F1-generation tumor tissues were minced to a size of 2 × 2 mm and subcutaneously implanted into the right flank of female NSG mice. The tumor volumes were measured weekly. When the tumor volumes reached approximately 100 mm3, the mice were randomized (n = 6 per group) and administered with vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 300, 5% Tween-80, and 45% saline) or lorlatinib (100 mg/kg body weight) by oral gavage every other day until the end of the experimental period. All protocols were approved by the UAB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Mouse tumorigenesis experiment in the immunodeficient Hu-NSG-IL15 and immunocompetent Hu-NSG-IL15-CD34 mouse model

NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl Tg (IL15)1Sz/Sz (Hu-NSG-IL15) and Hu-NSG-IL15-CD34 mice (16-24-week-old female mice) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. HCC PDX (Catalogue No. NIBRX-2969, Novartis PDX Collection, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) were obtained and the PDX were implanted into female (Hu-NSG-IL15) and Hu-NSG-IL15-CD34 mice (stock no. 030890, Jackson Laboratory). In brief, F1-generation tumor tissues were minced to a size of 2 × 2 mm and subcutaneously into the right flank of mice . The tumor volumes were measured weekly. When the tumor volumes reached approximately 100 mm3, the mice were randomized (n = 6 per group) and orally gavaged with vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 5% Tween-80, and 45% saline) or lorlatinib (100 mg/kg body weight) three times per week until the end of the experimental period. All protocols were approved by the UAB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Orthotopic hepatic tumor growth and spontaneous metastasis studies using human HCC cells

Male NSG mice (5-6-week-old) (stock no. 005557; The Jackson Laboratory) were anesthetized with isoflurane. For each mouse, the liver was located via an intra-abdominal incision. A Matrigel suspension (20 μL) containing Huh7-F-Luc and HepG2/C3A-F-Luc (2.5 × 105) was injected into the liver. The abdominal wall and skin were then closed using sutures. After 1 week, the mice were randomized into treatment groups (n = 5 per group) and were oral gavage three times per week until the end of the experimental period: vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 5% Tween-80, and 45% saline) or lorlatinib (100 mg/kg body weight) three times per week. The mice were imaged weekly until the completion of the experiment. Imaging was performed weekly by injecting the mice with D-luciferin. At the end point, the mice were euthanized, the livers and lungs were collected and placed in a 6-well plate, and images were obtained using the IVIS Xenogen imaging system. The total luminescence of the tumor-bearing areas was measured using Living Image in vivo imaging software (Perkin Elmer). All protocols for the mouse experiments were approved by the IACUC of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Lung metastasis studies with human HCC cells

SK-HEP-1-F-Luc cells were retro orbital injected into the right eye of the 5–6-week-old male NSG mice (stock no. 005557; The Jackson Laboratory). The mice were then treated with vehicle or 100 mg/kg of lorlatinib three times a week until the end of the experiment. Bioluminescence imaging was performed every week by injecting the mice with D-Luciferin until the end of the experiments. The mice were sacrificed, and the lungs were imaged to check metastasis. The intensities of the signals were measured ion ROI values using IVIS Lumina (Perkin Elmer). All protocols for the mouse experiments were approved by the IACUC of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Analysis of anti-PD-L1 and lorlatinib using Hepa1-6 based syngeneic model of hepatic tumor growth

The murine liver cancer cell line Hepa1-6 (1 x 107 cells in 100 μL of phosphate-buffered saline) was transplanted subcutaneously into 5-6-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (Stock: 000664, the Jackson Laboratories). After five days, when the tumors were established (mean tumor volume was approximately, 100 mm3), the mice were randomized based on tumor volumes. Tumor volumes were measured weekly and calculated using the following formula: length x width2 x 0.5. The mice were then administered with lorlatinib by oral gavage (100 mg/kg body weight) three times a week, while anti-PD-1 mAb (clone: RMP1-14; BioXcell) at 25 μg/mouse 3 times by intraperitoneal injections on days 5, 10 and 15 after tumor implantation. For combination experiments, lorlatinib was administered 30 min prior to anti-PD-1 administration. Mice in the control group were treated with the vehicle (10% DMSO, 40% PEG 300, 5% Tween-80, and 45% saline) by oral gavage. At the end of the experiment, the tumors were excised and photographed. All protocols were approved by the UAB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Method details

Plasmids, preparation of the lentivirus and generation of stable cell lines

The lentiviral empty vector (pLX304) and overexpression plasmids were purchased from Dharmacon and OriGene. The details of the plasmids are listed in the key resources table. Gene-specific lentiviral short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) were obtained from Open Biosystems. Lentiviral particles carrying shRNA or sgRNA were generated by co-transfecting shRNA or sgRNA plasmids with the lentiviral packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2.G into HEK293T cells using Effectene (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The culture medium was filtered using a 0.45-μm sterile filter to remove any dead or live cells. Stable cell lines were generated by infecting HCC cells with shRNA or sgRNA lentivirus in 12-well plates followed by puromycin selection (0.5-2 μg/ml). Details of the shRNA and sgRNA plasmids are listed in key resources table.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated using the ProScript First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (New England Biolabs). Quantitative PCR was performed using the Power SYBR Green Master Kit (Life Technologies). The oligonucleotide sequences used for the RT-qPCR are provided in the key resources table.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in ice-cold IP lysis buffer (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), containing protease inhibitor (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Briefly, lysed samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 45 min at 4°C and clarified supernatants were stored at –80°C. Protein concentrations were determined using Bradford Protein Assay Reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of protein samples (typically 20-25 μg) were electrophoresed on 6–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk prepared in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 and probed with relevant primary antibodies. After primary antibody incubation, the membranes were washed and incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000) (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and immunoblots were developed using either SuperSignal West Pico or Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific). All antibodies used for immunoblotting are listed in key resources table and provides information about their suppliers, catalogue numbers and RRID numbers.

Clonogenic assay

For clonogenic assays, Huh7 (10,000 cells), HepG2/C3A (5,000 cells) and SK-HEP-1 (1,000 cells) or ALK knockout cell lines or indicated gene knockdown or overexpression cells were seeded in a 6-well plate for clonogenic assay. After 48 h, the cells were treated with DMSO or lorlatinib or ABT-263 or ceritinib or doxorubicin or lorlatinib plus ABT-263 combination and allowed to grow for up to two weeks. Colonies were fixed and stained with a solution containing 50% methanol, 10% acetic acid, and 0.05% Coomassie Blue (Sigma-Aldrich).

Senescence associated β-galactosidase assay

Huh7 and HepG2/C3A or gene knockdown or overexpression HCC cells were seeded in a 6-well plate for senescence assay and treated with DMSO or 10 μM of lorlatinib for 96 h. The cells were stained according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cell Signaling; β-galactosidase staining kit). Briefly, cells were rinsed with 1X PBS and 1 ml of 1 X fixative solution was added and the cells were fixed for 10-15 min at the room temperature. This was followed by washing twice with 1X PBS. Next, 1 ml of the β-Galactosidase Staining Solution was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37°C overnight. β-Galactosidase staining solution was removed and the cells were overlayed with 70% glycerol and images were captured using the Olympus bright-field microscope.

CytoSelect 96-well quantitative soft agar assay

Anchorage-independent cell growth assay was performed using the CytoSelect 96-well Cell Transformation Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells per well) in triplicates and treated with either DMSO or lorlatinib (5 μM and 10 μM). After 7 days of incubation, culture medium was removed by inverting the plate and 50 μL of agar solubilization solution was added to each well of the 96-well plate and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The agar mixture was incubated with a CyQuant working solution. Fluorescence was measured at 485/520 nm using a 96-well microplate reader and relative florescence unit (RFU) were plotted as a graph.

Wound healing assay

For the wound healing assays, HepG2/C3A, SK-HEP-1, and Huh7 cells were grown in 6-well plates until they reached full confluence. A scratch was created using a sterile 10 μl pipette tip, and cell migration was monitored daily using light microscopy. For drug treatment experiments, the cells were treated with DMSO or lorlatinib (5 μM and 10 μM). Quantification of wound healing was performed using the ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Annexin V assay

The binding of annexin V to cells was measured using the PE-Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (Cat #559763; Pharmingen™, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, Huh7 and HepG2/C3A cells or GGN knockdown or NRG4 overexpressing cells were treated with either DMSO or 10 μM of the ALK inhibitor lorlatinib for 96 h. After treatment, cells were collected, washed twice with cold 1X PBS, and resuspended in 1x Binding Buffer. The cells were then stained with 5 μL PE Annexin V and 5 μL 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) and incubated for 15 min in the dark. Flow cytometry analysis was performed using a BD LSRFortessa Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Ashland, OR, USA).

Cleaved caspase-3 detection using flow cytometry

The induction of apoptosis in HCC cells or HCC with indicated shRNAs or open reading frame (ORF)-expressing cells without or with lorlatinib treatment (indicated in respective figure legends) were determined using an Alexa Fluor 647 Conjugated Cleaved Caspase-3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology; Cat# 9602) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, HCC cells were seeded in 6-well cell culture plates. After 24 h, cells were treated with DMSO or lorlatinib (10 μM). Following the incubation period of 96 h of lorlatinib treatment, the cells were trypsinized, collected, pelleted and were fixed by resuspending in 100 μl of 4% formaldehyde (methanol-free) (Cell Signaling Technology; Cat#47746) per 1 million cells. After 15 min of incubation at room temperature, cells were washed with 1X PBS and centrifuged. Pelleted cells were resuspended cells in 100 μl of 1X PBS and permeabilized by adding ice-cold 100% methanol slowly to pre-chilled cells, while gently vertexing, to a final concentration of 90% methanol for 15 min on ice. Thereafter, cells were washed twice by centrifugation in excess 1X PBS to remove methanol. The cells were then resuspended in 100 μl of diluted primary antibody (1:50) prepared in Antibody Dilution Buffer (0.5% BSA in 1X PBS), and were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in dark (protected from light). Next, cells were washed twice by centrifugation in 1X PBS. The cells were then resuspended cells in 350 μl of 1X PBS, and were analyzed by flow cytometry using LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Ashland).

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and data analysis