Abstract

Introduction

Understanding the interplay of immune mediators in relation to clinical outcomes during acute infection has the potential to highlight immune networks critical to symptom recovery. The objective of the present study was to elucidate the immune networks critical to early symptom resolution following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

Methods

In a community-based randomised clinical trial comparing inhaled budesonide against usual care in 139 participants with early onset SARS-CoV-2 (the STOIC study; clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT04416399), significant clinical deterioration (reported need for urgent care, emergency department visit, hospitalisation: the primary outcome), self-reported symptom severity (Influenza Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaire) and immune mediator networks were assessed. Immune mediator networks were determined using pre-defined mathematical modelling of immune mediators, determined by the Meso Scale Discovery U-Plex platform, within the first 7 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to 22 healthy controls.

Results

Interferon- and chemokine-dominant networks were associated with high viral burden. Elevated levels of the mucosal network (chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)13, CCL17, interleukin (IL)-33, IL-5, IL-4, CCL26, IL-2, IL-12 and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor) was associated with a mean 3.7-day quicker recovery time, with no primary outcome events, irrespective of treatment arm. This mucosal network was associated with initial nasal and throat symptoms at day 0.

Conclusion

A nasal immune network is critical to accelerated recovery and improved patient outcomes in community-acquired viral infections. Overall, early prognostication and treatments aimed at inducing epithelial responses may prove clinically beneficial in enhancing early host response to virus.

Shareable abstract

A robust nasal mucosal epithelium-derived immune network is critical to accelerated recovery from community-acquired viral infection https://bit.ly/4byXlpV

Introduction

The inflammatory environment generated by viral infections such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is multifaceted. Cellular and molecular immunity work in coordinated pathways to confer best protection against invading pathogens [1, 2]. The interplay of immune cells and signalling molecules is vital in host defence to detect, control and inhibit viral replication while simultaneously orchestrating repair and providing immunological memory [3]. Due to this complexity in immune component interactions, network analysis attempts to provide a higher dimension assessment of immune mediator changes and place changes to singular mediators in greater context in needed.

The global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic highlighted the importance of lung health and understanding airway immunopathology to prevent disease. For instance, the Steroids in COVID-19 (STOIC) study (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT04416399) examined the first 2 weeks of community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection both immunologically and clinically [4]. This real-world dataset demonstrated firstly that an early nasal type 2 T-helper (Th2) response, comparable to nasal signatures seen in rhinovirus infection [5], is observed following SARS-CoV-2 infection, and secondly, that an attenuated nasal interferon (IFN) response with increased chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)24 can be used as a biomarker to predict severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [6]. Importantly, the STOIC study also showed early use of inhaled budesonide reduced the chance of clinically significant deterioration including hospitalisation, and an accelerated time to clinical resolution [4]; findings that since been replicated in a larger cohort study [7]. Therefore, the STOIC study offers a primary-care model of viral acquisition which can be used to assess the critical inflammatory pathways which lead to a better prognosis.

In the present study, we aimed to understand the contribution of inflammatory mediator expression networks on clinical outcomes in participants with SARS-CoV-2. From four pre-defined immune networks present in the nose within the first 7 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection, we showed that a mucosal epithelium network which included CCL13, CCL17, interleukin (IL)-33, IL-5 and IL-4, was associated with quicker self-reported recovery and no primary outcome events. Our work shows that immune networks offer insight into mechanisms of viral clearance and offer a framework for future studies of inflammatory diseases.

Methods

Participants and ethics

This study included 139 participants from the STOIC open-label, parallel-group, phase 2, randomised controlled trial (Fulham London Research Ethics Committee and the National Health Research Authority 20/HRA/2531; NCT04416399) [4] and 22 healthy controls recruited at the University of Oxford (Oxford, UK; 18/SC/0361). These participants represent a subset of enrolled STOIC participants, and inclusion in this study was based on symptom questionnaire and nasal mediator assessment participation.

Study design

Healthy controls recruited at the University of Oxford were adults aged ≥18 years without any known history of respiratory disease or COVID-19 symptoms. Healthy controls provided a negative COVID-19 antigen test on the day of nasal mucosa sampling. Nasal sampling was performed using a nasosorption FX.I device (Hunt Developments UK, London, UK). Briefly, the synthetic absorptive matrix (SAM) strip was pressed gently against the inferior turbinate for 1 min. SAM strips were processed in an elution buffer containing 1.2% Triton-X, 1.0% bovine serum albumin in PBS.

In STOIC [4], participants aged ≥18 years experiencing COVID-19 symptoms as defined by onset of cough, fever, anosmia or a combination of these symptoms for <7 days were recruited. Recruitment was undertaken from July 2020 until January 2021 by local primary care networks, local COVID-19 testing sites and via multichannel advertising. Participants were randomised into two treatment groups, budesonide or usual care, on day 0 (day of enrolment). Usual care consisted of supportive therapy and encouragement to take antipyrectics for symptoms of fever. Participants randomised to receive budesonide were provided with a dry powder inhaler dose of 400 μg per actuation (two puffs to be taken twice per day: total dose 1600 μg; Pulmicort Turbuhaler; AstraZeneca, Gothenburg, Sweden). Participants allocated to budesonide were asked to halt budesonide treatment when they felt they had recovered (clinical recovery). The primary outcome was significant clinical deterioration defined by a need for urgent care, emergency department visit or hospitalisation for COVID-19. To note, the STOIC study was halted early due to treatment efficacy and statistical futility with continuation.

Participants recruited as part of STOIC were seen at their homes at day 0, day 7 and day 14 by a trained respiratory research nurse. Self-performed nasopharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 quantification and daily Influenza Patient-Reported Outcome (FLU-PRO) [8] symptoms scores were collected. At day 0 (pre-randomisation) and day 14, self-performed nasosorption samples were collected.

SARS-CoV-2 detection and quantification

Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from and stored immediately in RNAse solution. RNA was extracted from clinical samples using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (catalogue 52906; Qiagen) following manufacturer's instructions. 10 µL of eluted RNA was assayed using the Taqman fast virus 1-step master mix (ThermoFisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK), utilising oligonucleotide primers (600 nM forward and 800 nM reverse per reaction) and fluorescent conjugated probes (two probes 100 nM each) (Eurofins Genomics, Wolverhampton, UK) for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNase p gene (RdRP) gene region using ABI-7500 SDS Instruments (Applied Biosystems). A standard curve was determined using a plasmid expressing a known concentration of the RdRP gene. Sequences for primer and probes for quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR were as follows.

Dual-labelled probe P2: CAG GTG GAA CCT CAT CAG GAG ATG C

Dual-labelled probe P1: CCA GGT GGW ACR TCA TCM GGT GAT GC

PCR primer RdRP F: GTG ARA TGG TCA TGT GTG GCG G

PCR primer RdRP R: CAR ATG TTA AAS ACA CTA TTA GCA TA

Nasal immune mediator assessment

CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL11, CCL13, CCL17, CCL24, CCL26, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)8, CXCL10, CXCL11, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN-α2α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-33, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were quantified using MSD Quickplex SQ 120 1300 (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD, USA). All values below the lower limit of detection or above the upper limit of detection were replaced by the appropriate limit of detection value.

Single-cell transcriptomic overlay analysis

Transcripts encoding for mucosal mediators were assessed using publicly available data via the Lung Cell Atlas consortium and CELL×GENE (www.cellxgene.cziscience.com/gene-expression). Briefly, Yoshida et al. [9] nasal cavity (37 513 cells) or bronchial brushing (11 672 cells) data were used to visualise CCL13, CCL17, IL-33, IL-5, IL-4, CCL26, IL-2, IL-12 and CSF2 (encoding for GM-CSF) transcripts in adults (age ≥18 years) with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

FLU-PRO questionnaire and symptom indexing

To capture symptom burden from a respiratory virus infection, the validated FLU-PRO respiratory questionnaire was used in the STOIC study [8]. The questionnaire comprises 32 questions which cover symptom severity in the nose, throat, eyes, chest/respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract and body/systemic symptoms. Participants scored symptoms from not at all (0) to very much (4).

Statistical analysis

Pre-defined networks analysis was performed on nasal mediators (as determined by nasal immune mediator assessment by quantitative electrochemiluminescence) by first eliminating from the correlations matrix the contribution corresponding to “noise” eigenvalues, i.e. those present in the Marcenko–Pastur distribution. The remaining corrected matrix was taxonomised into functional clusters using the Louvain algorithm, which finds in these conditions anti- or un-correlated networks [6]. Network nomenclature was based on the predominant inflammatory pattern, IFN (IFN: IFN-α2α and IFN-β), innate immunity-like (innate: TSLP, IFN-γ, VEGF, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-6 and CCL24) and chemokine-dominant (chemokine: CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL11, CXCL8, CXCL10, CXCL11 and TNF). The nomenclature for the mucosal epithelium network (mucosal: CCL13, CCL17, CCL26, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-12p70, IL-33 and GM-CSF) was determined by utilising CELL×GENE and publicly available nasal cavity single-cell RNA sequencing data (EGAD00001007718) [9]. Genes of interest (CCL13, CCL17, IL-33, IL-5, IL-4, CCL26, IL-2, IL-12 and CSF2) were projected on a uniform manifold approximation and determined mRNA expression in multiple nasal epithelial cell types including basal, secretory, duct and ciliated cells determining this network as mucosal epithelium-derived (supplementary figure S1A–C).

Mediators per inflammatory network were log2-transformed and averaged, per subject (inflammatory score). High network expression was determined by an increased expression more than two standard deviations above health. Kolmogorov–Smirnov testing was performed to test for normality. Heatmaps were produced using mean inflammatory score in R using heatmap.2 within gplots. Hierarchical clustering with Manhattan distance with Pearson correlation coefficient was performed using R, to detect possible clustering patients based on treatment arm. All packages are available at CRAN (https://cran.r-project.org/). Qualitative FLU-PRO scores were averaged daily or stratified on targeted physiology daily questions and averaged. Symptom data are presented as a daily mean plus or minus standard error of the mean up to a maximum of day 14, or to the day when more than a quarter of participants still reported symptoms. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism v9.1 (GraphPad Software). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Viral burden is associated with differential immune network expression at day 0

To account for the kinetics of viral acquisition and initiation of inflammatory processes, we stratified STOIC participants based on an arbitrary cycle threshold value ≥30 or <30 (virallow and viralhigh, respectively) at time of recruitment (table 1). To note, viral copy number in viralhigh participants decreased by day 7, replicating previous SARS-CoV-2 kinetic studies [10, 11] (figure 1a; supplementary figure S2A,B).

TABLE 1.

Subject characteristics in participants stratified as high (viralhigh) or low (virallow) viral burden, and healthy controls

| Viralhigh | Virallow | Healthy controls | |

| Participants n | 60 | 79 | 22 |

| Age years | 44.8±13.4* | 45.2±13.2* | 36.5±11.5* |

| Male | 43.5 | 40.8 | 40.9 |

| White Caucasian | 85.5 | 97.4 | 63.6 |

| BMI kg·m−2 | 26.7±4.6 | 26.2±5.1 | |

| Never-smokers | 64.5 | 61.8 | 81.8 |

| Smoking pack-years | 16.4±15.6 | 14.1±13.4 | |

| Time to clinical recovery or primary outcome# days | 9.5±6.1 | 10.0±7.0 | |

| Primary outcome# n | 4.0 | 5.0 | |

| Day 0 Ct value | 21.7±3.8¶ | 37.5±3.1¶ |

Data are presented as mean±sd or %, unless otherwise stated. BMI: body mass index; Ct: cycle threshold. #: significant clinical deterioration defined by a need for urgent care, emergency department visit or hospitalisation for coronavirus disease 2019. *: p<0.05 between health and both viralhigh or virallow; ¶: p<0.05 between viralhigh and virallow. Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons; Chi-squared test for proportional data.

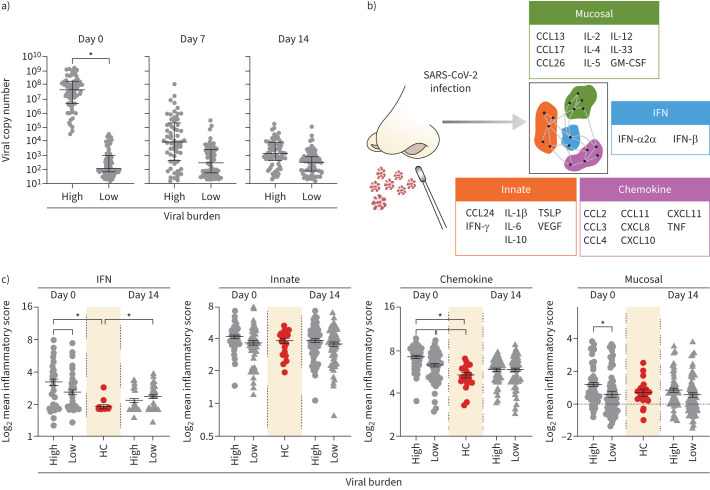

FIGURE 1.

Interferon, chemokine, and mucosal networks are increased in participants with high viral burden (viralhigh). a) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral copy number at days 0, 7 and 14 per subject stratified into viralhigh (n=60) or virallow (n=79) participants. b) Schematic showing day 0 upper respiratory tract networks defined by mathematical modelling in Baker et al. [6]. Data are presented as mean±sem; unpaired t-test with Welch's correction. c) Mean log2 network expression at days 0 and 14 compared to health. Data are presented as mean±sem; ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons. CCL: chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; IL: interleukin; GM-CSF: granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IFN: interferon; TSLP: thymic stromal lymphopoietin; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; CXCL: chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; TNF: tumour necrosis factor; HC: healthy controls. *: p<0.05.

Next, we assessed the impact of viral burden on pre-defined immune networks established within 7 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection [6] (figure 1b). Virushigh was associated with an elevated IFN, chemokine and mucosal network expression compared to virallow at day 0, i.e. within 7 days of symptom onset (figure 1c). The increase of the IFN and chemokine networks at day 0 dependent on viral burden replicates previous findings of immune response critical to virus defence [5, 12]. Notably, only the IFN and chemokine networks increased compared to health. We observed no difference in innate network expression between groups at either time point. As these networks form part of a complex inflammatory environment and are not observed in isolation, we performed hierarchical clustering which showed no grouping of participants based on network expression at day 0 or 14 (supplementary figure S2C,D). These data support concepts of robust initial IFN and chemokine response to infection [5, 12].

Budesonide maintains immune network expression

The primary aim of the STOIC study was to investigate the efficacy of inhaled budesonide, a corticosteroid, compared to usual care, on urgent care outcomes. Based on a random allocation to treatment, 54.4% of virallow and 45.0% of viralhigh participants were given budesonide, which provided a 4.6-day accelerated recovery in virallow participants and a trend to accelerated recovery in viralhigh participants (supplementary table S1). Notably, treatment did not affect viral copy number or any network expression, at any time point (supplementary figure S3A).

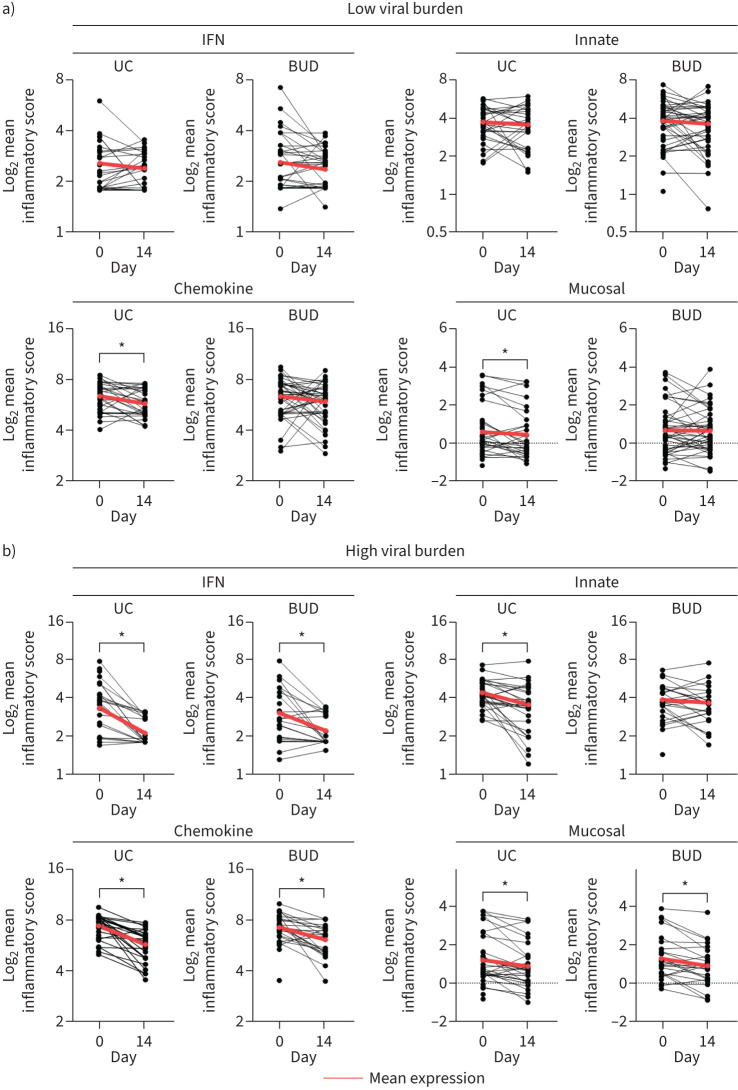

Given that corticosteroids impact immune mediators, SARS-CoV-2-induced network expression post-treatment at day 14 was investigated. No difference was observed in the IFN or innate network in viruslow participants in either treatment arm, while those in the usual care arm had decreased chemokine (1.52-fold) and mucosal network (1.10-fold) expression, potentially suggesting that budesonide aided recovery by maintaining higher expression across the disease time course (figure 2a). In viralhigh participants, there was a reduction over time in both treatment arms in the IFN (2.31-fold usual care; 1.78-fold budesonide), chemokine (1.25-fold usual care; 1.29-fold budesonide) and mucosal networks (3.10-fold usual care; 2.11-fold budesonide). In contrast, budesonide-treated viralhigh participants had unaltered innate network expression (figure 2b).

FIGURE 2.

Innate network expression was maintained by budesonide in participants with high viral burden (viralhigh). a) Paired analysis of day 0 and day 14 mean log2 immune network expression in virallow participants. b) Paired analysis of day 0 and day 14 mean log2 immune network expression in viralhigh participants. Data represent matched subject data daily. Paired t-test. Red line signifies the mean day 0 and day 14 expression. IFN: interferon; UC: usual care; BUD: budesonide. Participant numbers are presented in table 2. *: p<0.05.

Recovery was predominantly associated with innate and mucosal networks

To focus on the effects of budesonide on immune networks linked to recovery and symptoms, we assessed participants that were defined as high or low network expressors. A high network expressor was determined as having a mean expression two standard deviations higher than healthy controls. Clinical recovery was not different in participants with both high and low IFN/chemokine network expression (supplementary tables S2 and S3); however, clinical recovery was accelerated in budesonide arm of low innate (5.2-day) and low mucosal networks (5.6-day) in virallow participants (tables 2 and 3). High innate and high mucosal network expressors had a trend to accelerated recovery comparable to low expressors receiving budesonide. Therefore, we pursued the effects of innate and mucosal networks on symptom burden.

TABLE 2.

Innate network subject characteristics stratified based on treatment and viral burden

| Low innate network | High innate network | |||

| Usual care | Budesonide | Usual care | Budesonide | |

| High viral burden | ||||

| Participants n | 21 | 20 | 12 | 7 |

| Age years | 50.0±11.4 | 45.3±13.5 | 37.5±13.2 | 40.6±14.4 |

| Male | 52.4 | 35.0 | 41.7 | 57.1 |

| White Caucasian | 90.5 | 95.0 | 91.7 | 57.1 |

| BMI kg·m−2 | 27.4±4.9 | 26.6±4.6 | 25.6±4.5 | 26.7±4.5 |

| Never-smokers | 47.6 | 65.0 | 91.7 | 85.7 |

| Smoking pack-years | 13.9±16.3 | 20.1±15.2 | 2.5±0.0 | 31.3±0.0 |

| Time to clinical recovery or primary outcome# days | 11.0±7.8 | 8.4±3.8 | 9.3±7.2 | 8.5±2.6 |

| Primary outcome# n | 3.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| Day 0 Ct value | 21.3±3.5 | 22.4±4.1 | 21.6±4.2 | 21.1±3.9 |

| Low viral burden | ||||

| Participants n | 29 | 28 | 7 | 14 |

| Age years | 43.2±12.9 | 44.3±13.5 | 55.3±15.8 | 45.9±10.9 |

| Male | 35.0 | 55.2 | 14.3 | 28.6 |

| White Caucasian | 96.6 | 96.6 | 85.7 | 92.9 |

| BMI kg·m−2 | 25.3±3.7 | 26.8±5.6 | 27.9±6.3 | 26.2±5.8 |

| Never-smokers | 62.1 | 55.2 | 57.1 | 64.3 |

| Smoking pack-years | 15.6±13.5 | 17.7±15.1 | 11.6±10.1 | 3.2±3.4 |

| Time to clinical recovery or primary outcome# days | 13.5±9.0* | 8.3±4.0* | 8.7±3.5 | 7.1±6.1 |

| Primary outcome# n | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Day 0 Ct value | 38.2±2.8 | 36.2±3.5 | 38.5±2.8 | 38.1±2.9 |

Data are presented as mean±sd or %, unless otherwise stated. BMI: body mass index; Ct: cycle threshold. #: significant clinical deterioration defined by a need for urgent care, emergency department visit or hospitalisation for coronavirus disease 2019. *: p<0.05 low innate network; usual care versus budesonide. All statistics within viral burden groups. Ordinary two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons; Chi-squared test for proportional data.

TABLE 3.

Mucosal network was associated with improved recovery and no primary outcome events

| Low mucosal network | High mucosal network | |||

| Usual care | Budesonide | Usual care | Budesonide | |

| High viral burden | ||||

| Participants n | 24 | 21 | 9 | 6 |

| Age years | 49.8±11.2* | 47.8±12.4 | 34.0±12.5* | 31.0±9.5 |

| Male | 45.8 | 33.3 | 55.6 | 66.7 |

| White Caucasian | 95.8 | 100.0 | 77.8 | 33.3 |

| BMI kg·m−2 | 27.3±4.2 | 27.1±4.6 | 25.2±6.1 | 24.8±3.9 |

| Never-smokers | 54.2 | 66.7 | 88.9 | 83.3 |

| Smoking pack-years | 11.6±16.0 | 18.4±12.5 | 27.6±0.0 | 43.6±0.0 |

| Time to clinical recovery or primary outcome# days | 11.8±8.3 | 8.4±3.5 | 6.6±1.9 | 8.6±3.6 |

| Primary outcome# n | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Day 0 Ct value | 21.4±3.6 | 22.2±4.1 | 21.4±4.1 | 21.5±4.2 |

| Low viral burden | ||||

| Participants n | 30 | 33 | 6 | 10 |

| Age years | 48.5±12.7* | 46.5±12.7 | 30.8±12.0* | 39.3±11.1 |

| Male | 23.3 | 51.5 | 66.7 | 30.0 |

| White Caucasian | 96.7 | 93.9 | 83.3 | 100.0 |

| BMI kg·m−2 | 25.6±3.8 | 26.8±5.7 | 26.6±6.5 | 25.9±5.6 |

| Never-smokers | 56.7 | 57.6 | 83.3 | 60.0 |

| Smoking pack-years | 15.8±12.4 | 16.8±14.9 | 1.0±0.0 | 3.0±4.0 |

| Time to clinical recovery or primary outcome# days | 13.9±8.5+ | 8.3±4.8+ | 6.0±3.0+ | 6.7±4.9 |

| Primary outcome# n | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Day 0 Ct value | 38.1±2.7 | 37.4±2.8 | 38.7±3.2 | 34.9±4.3 |

Data are presented as mean±sd or %, unless otherwise stated. BMI: body mass index; Ct: cycle threshold. Subject characteristics stratified based on mucosal network and viral burden. #: significant clinical deterioration defined by a need for urgent care, emergency department visit or hospitalisation for coronavirus disease 2019. *: p<0.05 usual care; low versus high mucosal network; +: p<0.05 compared to usual care low mucosal network. All statistics within viral burden groups. Ordinary two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons; Chi-squared test for proportional data.

Innate network expression was associated with increased nasal symptoms

36.4% of usual care and 25.9% of budesonide-treated participants were classified as having high innate network expression at day 0 (table 2). Only increased nasal symptoms at day 0 was observed in high innate network virallow participants (figure 3a; supplementary figure S4A–C). Given that this difference in symptoms probably reflects inherent differences at enrolment, we proceeded to assess symptomology independent of treatment.

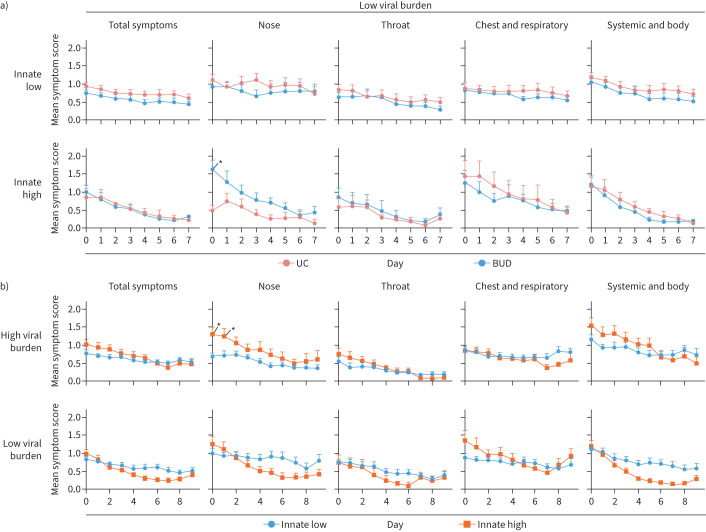

FIGURE 3.

High innate network expression was associated with increased nasal symptoms. a) Daily symptom severity in participants with low viral burden (virallow) based on treatment arm stratified into low or high innate network expressing participants. Daily participant numbers are shown in supplementary figure S4A,B. b) Daily symptom severity in low or high innate network expressing participants stratified into viralhigh and virallow participants. Daily participant numbers are shown in supplementary figure S4D. a, b) Data are presented as daily mean±sem. Ordinary two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test. UC: usual care; BUD: budesonide. Participant numbers are presented in table 3. *: p<0.05.

31.7% of viralhigh and 26.9% of virallow participants had high innate network expression. High innate network expression was associated with worsened nasal symptoms at day 0 and 1 with high viral burden (figure 3b; supplementary figure S4D). Thus, regardless of innate network expression, participants experienced similar symptom severity in both treatment arms, but high innate network expression was associated with increased nasal symptoms.

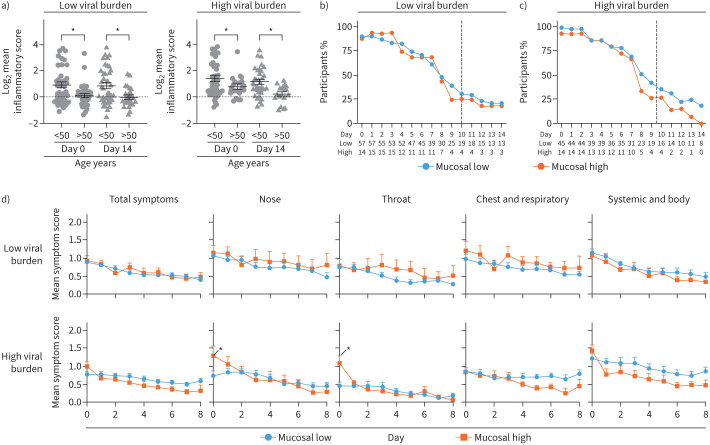

Mucosal network is associated with improved self-reported recovery and no primary outcome events

20.2% of virallow and 25.0% of viralhigh participants were classified as having high mucosal network expression at day 0. High mucosal network expression was the only network associated with no primary outcome events (tables 2 and 3, supplementary tables S2 and S3). To this end, high mucosal network participants had a mean 3.7-day accelerated recovery (virallow 2.5 days, viralhigh 4.8 days, averaged between treatments) and were typically younger (virallow 12.5 years younger, viralhigh 16.3 years younger) (table 3). Based on an arbitrary age threshold, the mucosal network was decreased in virallow and viralhigh in >50-year-old subjects (figure 4a). Notably, >50-year-old virallow and viralhigh subjects had decreased IFN network at day 0 and decreased innate network expression at day 14 respectively (supplementary figure S5A and B).

FIGURE 4.

High mucosal network expression was associated with more severe nasal and throat symptoms at day 0. a) Mean log2 mucosal network expression at day 0 and 14 in age-stratified groups. Data are presented as mean±sem. Two-way ANOVA. Daily percentage of participants reporting any symptom in low or high mucosal network expressing participants in b) participants with low viral burden (virallow) or c) viralhigh participants. Dotted line represents mean clinical recovery. Total number of participants are shown below each graph. d) Daily symptom severity in low or high mucosal network expressing participants stratified into viralhigh or virallow participants. Daily participant numbers are shown in b and c. Data are presented as the daily mean±sem. Ordinary two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test. *: p<0.05.

No difference was observed between usual care and budesonide arms in mucosal network expression (supplementary figure S3D). Therefore, symptom analysis was conducted independent of treatment. The number of virallow participants reporting symptoms were comparable in low and high mucosal network groups (figure 4b and d upper panel). In contrast, high mucosal network was associated with increased nasal and throat symptom severity at day 0 in viralhigh participants (figure 4c and d lower panel). Overall, these data suggest that while symptom severity is generally comparable in either low or high mucosal network participants, high network expression was associated with accelerated recovery and no primary outcome.

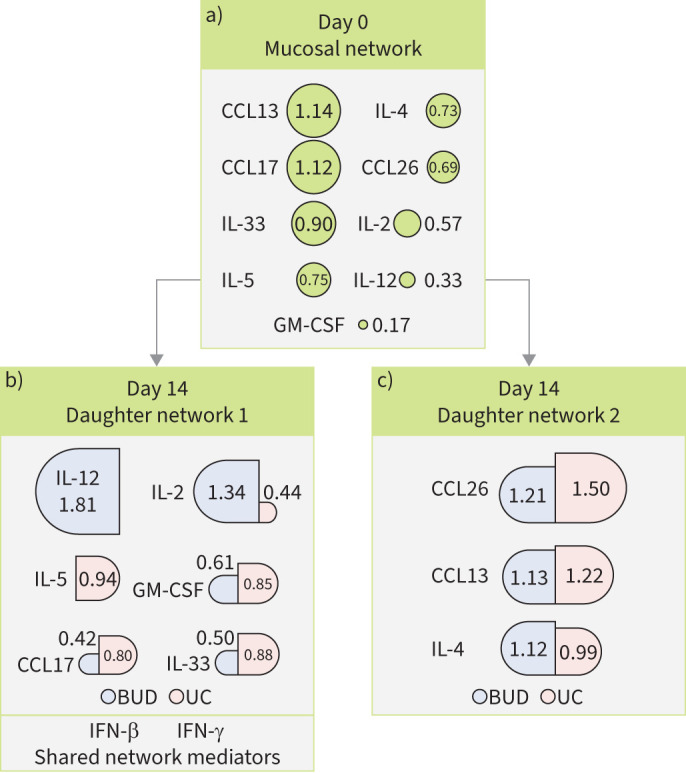

The mucosal network forms two daughter networks by day 14

Inflammatory pathways are dynamic, with multiple feedback loops influencing mediator expression. We determined the local weighted degree of connectivity between mediators in the mucosal network at days 0 and 14 to understand the contribution of each immune mediator to the network independent of viral burden or clinical outcome. At day 0, CCL13 (1.14), CCL17 (1.12) and IL-33 (0.90) had the greatest weighted degree and thus the most locally connected mediators in the mucosal network (figure 5a; supplementary table S4). By day 14, the mucosal network separated into two daughter networks consisting of networks of CCL17, IL-2, GM-CSF and IL-33 (figure 5b) or CCL26, CCL13 and IL-4 (figure 5c). These day-14 daughter networks became linked with other immune mediators outlined in supplementary table S4. Notably, daughter network 1 included IFN-β and IFN-γ in both budesonide and usual care subjects (figure 5b). Moreover, IFN-α was linked with daughter network 1 in budesonide participants and daughter network 2 in usual care participants, proposing that IFN-α and other IFN molecules are closely linked to mucosal network mediators. Together, these data propose the mucosal network divides into two daughter networks during the first 14 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

FIGURE 5.

Mucosal network-derived daughter networks at day 14 of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Schematic showing weighted degrees of connectivity of a) day 0 mucosal network and day 14 daughter network b) 1 and c) 2. Size of circles (day 0) and semicircles (day 14; stratified by treatment arm) are proportional to degree of connectivity in participants. CCL: chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; IL: interleukin; GM-CSF: granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; BUD: budesonide; UC: usual care; IFN: interferon.

Discussion

A coordinated immune response composed of cell and mediator interactions is vital for host defence. In this cohort, increased mucosal network mediators, which included CCL13, CCL17, IL-33, IL-5, IL-4 and CCL26, was associated with accelerated recovery. Notably, only high mucosal network expression was associated with no primary outcome in either treatment arm, unlike high expression of other networks. Previously, these mucosal mediators have each been associated with viral infections, in particular the alarmin, IL-33 (reviewed by Murdaca et al. [13]). In COVID-19 specifically, IL-33 has been strongly associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection [14], and together with CCL26 has been found in plasma within 10 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection [15]. Increased IL-4/5 [16], CCL13 [17] and CCL17 [18] has been observed in other respiratory infections in patients with atopy, suggesting that this mucosal network response is not SARS-CoV-2 specific. The expression of these mediators supports the role of Th2-like responses in the upper respiratory tract triggering cells including innate lymphoid cells, B-cells and eosinophils to perform early viral control [5, 16, 19].

The STOIC study previously demonstrated that inhaled budesonide treatment was beneficial for improved clinical recovery [4], and moreover, that budesonide decreased IL-33 and increased CCL17 in the upper respiratory tract in SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals [6]. Here, we expanded on this analysis, demonstrating that budesonide maintained innate and IFN network expression over a 14-day period as compared to usual care, but did not alter viral copy number. This suggests that budesonide modulates the fever response, but not cellular viral particle clearance. Hence, individuals report clinical recovery earlier, but viral load remains comparable between usual care and budesonide treated individuals. Notably, day 14 sampling was post-clinical recovery. Therefore, future studies aimed at elucidating budesonide impact on network kinetics during the first 7 days of infection are needed. Ultimately, our ability to modulate immune networks early, via budesonide or by network-specific therapies that avoid primary outcome strategies, will provide virus-infected patients with improved recovery outcomes.

The immune response to clear an insult and then restore tissue homeostasis is dynamic [1, 2]. In this study, we showed that the mucosal network splits into two daughter networks by day 14 with conserved links with IFN-α, -β and -γ, key mediators in the viral response, regardless of the treatment arm [20]. We showed that mucosal network transcripts were increased following infection in the nasal epithelium, cells important for barrier defence and IFN release, which through these multiple mediators together produce an effective antiviral response. More frequent sampling is necessary to identify the kinetic switch to these daughter networks during the first 14 days of infection. The dynamics of mediator networks will offer insight into viral immunopathology and highlight potential immunological mechanisms to stimulate the epithelium to hasten viral symptom recovery.

This community-based care study provides clinical outcomes with associated nasal inflammatory networks from a real-world setting. We observed a 3.7-day accelerated SARS-CoV-2 recovery in participants with high mucosal networks. Despite earlier recovery, we observed limited differences in symptom severity between high and low network expressing participants, with differences only observed at days 0 and 1. As participants were enrolled up to 7 days into symptom onset, the worst of symptoms may have passed [11], and thus inflammatory resolution may have begun. Importantly, as participants recovered, they stopped completing FLU-PRO questionnaires, therefore decreasing the statistical power at later time points to assess severity differences. Therefore, we restricted our analysis up to the day by which 25% of subjects still reported symptoms and acknowledge that to observe symptom severity differences between immune network expression a larger cohort is required.

Elderly individuals are at greater risk from SARS-CoV-2 infection due to epigenetic, immunosenescence and higher basal inflammation processes [21], even following vaccination [22]. Here, we demonstrated that a high mucosal network was observed in virallow and viralhigh adult participants 12.5 years and 16.3 years younger, respectively. Furthermore, >50-year-olds had decreased mucosal network expression regardless of viral burden. Given that COVID-19 caused more mortality in elderly patients [23], this observation provides mechanistic insight into this phenomenon. The paradigm is that individuals with higher basal or inducible mucosal network mediators can clear virus more quickly, and thus avoid the worst symptoms and complications of disease. This basal or inducible response wanes as individuals age, subsequently predisposing elderly individuals to viral infection. Notably, this study was not designed to compare age-dependent inflammatory and symptom severity responses to SARS-CoV-2, and further studies are needed to determine the role of mucosal immune networks in the elderly cohorts. We propose that a robust and coordinated upper respiratory tract mucosal network response is vital for a successful defence against SARS-CoV-2.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that an upper respiratory tract mucosal response which includes CCL13, CCL17, IL-33, IL-5, IL-4, CCL26, IL-2, IL-12 and GM-CSF was associated with a 3.7-day quicker symptom resolution in SARS-CoV-2-infected participants. In addition, elevated mucosal node was associated with younger adults and no primary outcome events. These data showed that symptom severity and clinical resolution was similar between participants with high and low viral burden. Together, these data offer insight into potential coordinating inflammatory mediators key to the control and swift symptom resolution of SARS-CoV-2. There are several potential clinical impacts that follow from our results. It would be important to study the potential role of inducing mucosal mediators in the epithelium to accelerate the resolution of viral infection. Moreover, these data highlight the importance of assessing cytokine panels as part of routine clinical practice to identify individuals at risk of poor clinical outcomes. It may also be possible to study the value of the mucosal mediators as prognostic markers in viral infection, thus allowing antiviral therapy to be guided to those at most risk.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT (487.8KB, pdf)

Figure S1 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT (1.7MB, tif)

Figure S2 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT2 (126.5KB, tif)

Figure S3 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT3 (171.6KB, tif)

Figure S4 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT4 (181.9KB, tif)

Figure S5 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT5 (95.6KB, tif)

Acknowledgements

We would like to specifically thank Karolina Krassowska, Beverly Langford and Helen Jeffers (Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK), and members of the Oxfordshire Primary Care Network for helping to enrol and collect respiratory samples.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Data sharing: All data can be shared upon written request to the corresponding author. A data sharing agreement will be needed.

Ethics statement: This study included participants from the STOIC open-label, parallel-group, phase 2, randomised controlled trial (Fulham London Research Ethics Committee and the National Health Research Authority 20/HRA/2531, NCT04416399) and 22 healthy controls recruited at the University of Oxford (18/SC/0361).

Author contributions: S.P. Cass wrote the manuscript. J.R. Baker, M. Mahdi, C. Mwasuku and S. Ramakrishnan were responsible for sample collection and processing. S.P. Cass, D.V. Nicolau Jr and R.T. Martinez-Nunez analysed the data. S.P. Cass, D.V. Nicolau Jr, J.R. Baker, C. Mwasuku, P.J. Barnes, L.E. Donnelly, R.T. Martinez-Nunez, R.E.K. Russell and M. Bafadhel were responsible for data interpretation and critical revision of the work. P.J. Barnes, L.E. Donnelly, R.E.K. Russell and M. Bafadhel conceived and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the contents of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: S.P. Cass is an early career editor of this journal. S. Ramakrishnan, L.E. Donnelly and M. Bafadhel report grants from AstraZeneca during the conduct of this study paid to the institute.

Support statement: This study was funded by the Oxford NIHR BRC and AstraZeneca (Gothenburg, Sweden). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Rieckmann JC, Geiger R, Hornburg D, et al. Social network architecture of human immune cells unveiled by quantitative proteomics. Nat Immunol 2017; 18: 583–593. doi: 10.1038/ni.3693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nish S, Medzhitov R. Host defense pathways: role of redundancy and compensation in infectious disease phenotypes. Immunity 2011; 34: 629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merad M, Blish CA, Sallusto F, et al. The immunology and immunopathology of COVID-19. Science 2022; 375: 1122–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.abm8108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramakrishnan S, Nicolau DV, Langford B, et al. Inhaled budesonide in the treatment of early COVID-19 (STOIC): a phase 2, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 763–772. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00160-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarze J, Mackenzie KJ. Novel insights into immune and inflammatory responses to respiratory viruses. Thorax 2013; 68: 108–110. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker JR, Mahdi M, Nicolau DV, et al. Early Th2 inflammation in the upper respiratory mucosa as a predictor of severe COVID-19 and modulation by early treatment with inhaled corticosteroids: a mechanistic analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10: 545–556. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00002-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu LM, Bafadhel M, Dorward J, et al. Inhaled budesonide for COVID-19 in people at high risk of complications in the community in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial. Lancet 2021; 398: 843–855. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01744-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powers JH, Bacci ED, Leidy NK, et al. Performance of the inFLUenza Patient-Reported Outcome (FLU-PRO) diary in patients with influenza-like illness (ILI). PLoS One 2018; 13: e0194180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida M, Worlock KB, Huang N, et al. Local and systemic responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adults. Nature 2022; 602: 321–327. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04345-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Néant N, Lingas G, Le Hingrat Q, et al. Modeling SARS-CoV-2 viral kinetics and association with mortality in hospitalized patients from the French COVID cohort. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2021; 118: e2017962118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2017962118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med 2020; 26: 672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melchjorsen J, Sørensen LN, Paludan SR. Expression and function of chemokines during viral infections: from molecular mechanisms to in vivo function. J Leukoc Biol 2003; 74: 331–343. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1102577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murdaca G, Paladin F, Tonacci A, et al. Involvement of Il-33 in the pathogenesis and prognosis of major respiratory viral infections: future perspectives for personalized therapy. Biomedicines 2022; 10: 715. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10030715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanczak MA, Sanin DE, Apostolova P, et al. IL-33 expression in response to SARS-CoV-2 correlates with seropositivity in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Nat Commun 2021; 12: 2133. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22449-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucas C, Wong P, Klein J, et al. Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature 2020; 584: 463–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2588-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansel TT, Tunstall T, Trujillo-Torralbo MB, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of nasal and bronchial cytokines and chemokines following experimental rhinovirus infection in allergic asthma: increased interferons (IFN-γ and IFN-λ) and type 2 inflammation (IL-5 and IL-13). EBioMedicine 2017; 19: 128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jha A, Thwaites RS, Tunstall T, et al. Increased nasal mucosal interferon and CCL13 response to a TLR7/8 agonist in asthma and allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 147: 694–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams TC, Jackson DJ, Maltby S, et al. Rhinovirus-induced CCL17 and CCL22 in asthma exacerbations and differential regulation by STAT6. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2021; 64: 344–356. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0011OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang YJ, Kim HY, Albacker LA, et al. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol 2011; 12: 631–638. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katze MG, He Y, Gale M. Viruses and interferon: a fight for supremacy. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2: 675–687. doi: 10.1038/nri888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueller AL, McNamara MS, Sinclair DA. Why does COVID-19 disproportionately affect older people? Aging 2020; 12: 9959–9981. doi: 10.18632/aging.103344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonelli M, Penfold RS, Merino J, et al. Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case–control study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22: 43–55. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00460-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray WK, Navaratnam AV, Day J, et al. COVID-19 hospital activity and in-hospital mortality during the first and second waves of the pandemic in England: an observational study. Thorax 2022; 77: 1113–1120. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-218025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT (487.8KB, pdf)

Figure S1 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT (1.7MB, tif)

Figure S2 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT2 (126.5KB, tif)

Figure S3 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT3 (171.6KB, tif)

Figure S4 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT4 (181.9KB, tif)

Figure S5 00919-2023.SUPPLEMENT5 (95.6KB, tif)