Abstract

Solvatochromism occurs in both homogeneous solvents and more complex biological environments, such as proteins. While in both cases the solvatochromic effects report on the surroundings of the chromophore, their interpretation in proteins becomes more complicated not only because of structural effects induced by the protein pocket but also because the protein environment is highly anisotropic. This is particularly evident for highly conjugated and flexible molecules such as carotenoids, whose excitation energy is strongly dependent on both the geometry and the electrostatics of the environment. Here, we introduce a machine learning (ML) strategy trained on quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics calculations of geometrical and electrochromic contributions to carotenoids’ excitation energies. We employ this strategy to compare solvatochromism in protein and solvent environments. Despite the important specifities of the protein, ML models trained on solvents can faithfully predict excitation energies in the protein environment, demonstrating the robustness of the chosen descriptors.

1. Introduction

Solvatochromism has been extensively investigated for molecules in common solvents using both empirical models and quantum chemical approaches combined with continuum and atomistic classical descriptions.1−9 The same strategies have also been applied to complex environments like proteins and other biological matrices.10−14 However, analyzing solvatochromism in these settings is notably more complicated, not only because the molecule is embedded in a highly anisotropic environment but also because the binding pocket can induce much larger geometrical distortions than what is generally observed in solution. By affecting the electronic density of the molecule, electrostatic anisotropy and geometrical distortions indirectly change the solvatochromism, making the traditional interpretation in terms of long- and short-range effects less applicable.

This increased complexity is particularly evident for molecules with large geometrical and electronic flexibility. A perfect example is represented by carotenoids, one of the largest families of naturally occurring pigments. Carotenoids are involved in various biological processes, but they have a fundamental role in photosynthesis.15,16 In organisms that live in light-deprived conditions, they act as accessory light-harvesting pigments to improve light absorption by the photosynthetic antenna complexes. Moreover, they have an essential role within all photosynthetic organisms due to their photoprotective function.

Such a multifaceted role is certainly connected to the large variety of molecular structures in naturally occurring carotenoids, which have in common a long conjugated backbone but can differ in the number of conjugated double bonds and in the position and nature of the peripheral functional groups. Carotenoids are also able to exert different functions when embedded in different environments due to their flexible photophysical and photochemical response.17−24 Given the importance of these solvatochromic effects, studies of carotenoids’ optical and photophysical properties in solvents of varying dielectric properties have been conducted.17,18,20,21,23,24 However, it is not clear to what extent can common solvents be taken as representative of the biological environment.23,25

The high flexibility of carotenoids’ photophysical properties is explained in terms of their unique electronic structure. A minimal model for the carotenoid electronic structure involves the ground-state S0, of approximate A–g symmetry, and the two lowest excited states S1 (2A–g) and S2 (1B+u). The transition from S0 to S1/2A–g is notoriously optically forbidden due to its symmetry properties;18,23,26 therefore, this state is also called the “dark” state, and its energetic location is difficult to pinpoint.18 It is instead the strongly allowed S0 → S2 transition that is responsible for the intense absorption of carotenoids in the visible region. Other low-lying dark states have been detected or proposed to account for spectroscopic observations or excited-state dynamics;27 however, a model with S1/2A–g and S2/1B+u is generally sufficient to explain most of the observed properties.23

Quantum chemical and multiscale calculations have been extremely useful to understand the excited-state properties of carotenoids in various environments.28−42 In particular, some of the present authors demonstrated that a quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) approach combining multireference semiempirical (SE) methods with electrostatic embedding of the environment is able to capture both the dark and the bright states of carotenoids.39−42

Here, we extend and generalize the analysis by combining QM/MM calculations with a machine learning (ML) approach to achieve a detailed understanding of the physics that underlies the differences in the solvatochromic shift when moving from a homogeneous solvent to proteins. ML models have now become increasingly useful, not only to substitute for or complement QM calculations but also to generate additional insight into chemical processes and, in particular, excited states.43−46

Solvatochromic effects may arise because a certain environment induces geometrical changes in the chromophore or because the electrostatic distribution of the environment (charges, dipoles, etc.) interacts with the electronic density of the chromophore, which we call the electrochromic effect. The idea is to exploit ML to disentangle the geometrical and electrochromic contributions to the solvatochromic effect47 in each different environment and finally compare the corresponding models to point out the specificity of the protein.

This analysis is here applied to the S1 and S2 states of the carotenoids that are commonly found in plant photosystems (Figure 1): lutein (Lut), violaxanthin (Vio), zeaxanthin (Zea), and neoxanthin (Neo). All of them belong to the family of xanthophylls, e.g., carotenoids containing oxygen atoms. We analyze their excitation energies in three different environments. Initially, we explore an isotropic yet polar solvent, methanol. Next, we create an artificial environment by introducing charges randomly within methanol, aiming to replicate a setting more akin to a protein environment. Finally, we consider the trimeric light-harvesting complex II (LHCII) of plants.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the carotenoids considered in this work.

We find that the electrostatics of the protein environment markedly differ from the electrostatic configurations experienced in the homogeneous solvent, even with artificially added charges. Nonetheless, the ML models are capable of extrapolating information from one environment to another without substantial drops in accuracy. This opens up the possibility of quickly and reliably analyzing solvatochromic effects in multiple environments.

2. Methods

2.1. Diabatization

In their adiabatic representation, carotenoids’ low-lying excited states can run into crossings along some dimensions of the PES, e.g., the bond length alternation (BLA), as shown in Figure 2. Moreover, the physical characteristics of each state (symmetry, MO occupancy, single/multireference character, transition dipole) exchange at those crossings. For these reasons, it is convenient to adopt a diabatic representation instead of an adiabatic one. Diabatic states are characterized by a smooth variation with respect to nuclear coordinates and preserve their character when going through crossing regions. A diabatic representation η can be obtained as a linear transformation of the adiabatic states ϕ

| 1 |

where T is an orthogonal transformation matrix chosen according to the nature of the transformation.48 An exact diabatic representation is not feasible because it would require considering the complete set of electronic states in the transformation. However, there are many ways to obtain an approximated quasi-diabatic basis,49−55 combining only an arbitrary number of adiabatic states.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic structure of Lut. The double bonds used for the BLA calculation are shown in red, and the single bonds, in blue. (b) Formula used to compute the BLA. (c) Relaxed scan over the BLA of Lut in vacuum. The geometry optimization (with fixed BLA) and excitation energies are computed with the R-AM1/FOMO-CISD(6,9) SE method. Different colors correspond to different adiabatic states (black for S0, red for S1, blue for S2, and orange for S3), and the color intensity depends on the value of the magnitude of the transition dipole moment from S0 to the other three states.

In this work, we use a two-state diabatization based on transition dipoles from the ground state to the S1 and S2 adiabatic states, that can be classified as a property-based method.49 We build the transformation matrix from the eigenvectors of a matrix containing dot products of transition dipoles (M)

| 2 |

| 3 |

where  is the transition dipole vector

between

the ground state and the n-th excited state. At this

point, the eigenvectors are used to transform the adiabatic excitation

energies of S1 and S2 stored in the diagonal

matrix A to a nondiagonal diabatic matrix D

is the transition dipole vector

between

the ground state and the n-th excited state. At this

point, the eigenvectors are used to transform the adiabatic excitation

energies of S1 and S2 stored in the diagonal

matrix A to a nondiagonal diabatic matrix D

| 4 |

The diagonal elements of D are the energies  of the diabatic

states that we refer to

as “dark”

of the diabatic

states that we refer to

as “dark”  and “bright”

and “bright”  states, whereas the off-diagonal elements

are the diabatic couplings.

states, whereas the off-diagonal elements

are the diabatic couplings.

This diabatization method is not general, but it is suited for our purpose for two reasons. First, we can limit our dataset so that the bright character (high transition dipole) is located either on S1 or S2 since we extract our training geometries from classical molecular dynamics where the percentage of frames where the bright state is higher-lying (S3) is very low. Second, considering only two states makes this approach simple and very efficient to disentangle the crossing between S1 and S2 (see Figure 2). The main drawback of this property-based diabatization method is that it is not able to distinguish between different dark states. This means that the resulting dark state is still a mixture of more than one state (for example, 2A–g and 1B–u). Nevertheless, for our purposes, it proved to be more efficient than other, more general, diabatization strategies. For example, a diabatization based on the maximization of the overlap matrix with reference states55 was used for carotenoids in various previous works by some of us,40−42 but it is less efficient when applied to geometries that are very different from the one used as a reference.49 Another issue generally regarding property-unblending strategies, like the one employed here, is that the sign of the diabatic couplings (off-diagonal elements of D) is arbitrary and can be inconsistent from geometry to geometry. This means that it is not possible to learn the coupling arising from this diabatization without further precautions to control the coupling sign. Several ways to fix this problem were proposed.49,53 Here, we refrain from considering the diabatic couplings and instead focus on the excitation energies of the dark and bright state.

2.2. Machine Learning Models

In this section, we detail our ML strategy. In particular, we train regression models to predict the excited state energies of carotenoids from snapshots of classical MD trajectories. The internal geometry of the carotenoid was described using the Coulomb matrix (CM) descriptor,56 which uses inverse pairwise distances weighted by the atomic number of the atoms involved

| 5 |

where rij = ∥ri – rj∥ is the Euclidean distance between atoms i and j. As the CM is symmetric, we have used just its off-diagonal part, also excluding hydrogen atoms. In particular, we remove the equivalent hydrogens of the methyl groups, which are the only atoms that can exchange within our molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. This avoids any atom permutations, which would be problematic for a non-permutation-invariant descriptor such as the CM.

The environment was included, using as a descriptor the electrostatic potential generated by the MM charges on each QM atom47

| 6 |

| 7 |

where the sum runs over the environment atoms, and rim is the Euclidean distance between the i-th QM atom and the m-th environment atom characterized by a charge qm. The descriptor is computed at each configuration by subtracting the mean of the potential over the QM atoms in order to ensure independence from the (arbitrary) zero of the electrostatic potential. The potential was computed for all the QM atoms, hydrogens included. The charges used for the environment atoms are the same as used those in the QM/MM calculations.

We have expressed the excitation energy of the dark and bright

diabatic states of the solvated (or embedded) molecule using a hierarchical

approach, where the predicted electrochromic shift  is added on top of a vacuum contribution

is added on top of a vacuum contribution

| 8 |

The “hat”

notation is

used to distinguish the prediction  from the target

from the target  .

.  is the excitation energy

of the diabatic

state in the absence of the environment. The electrochromic shift

is the excitation energy

of the diabatic

state in the absence of the environment. The electrochromic shift  is obtained instead by

subtracting

is obtained instead by

subtracting  from the energy of the

diabatic state obtained

in a QM/MM calculation,

from the energy of the

diabatic state obtained

in a QM/MM calculation,  , as detailed in the following

section.

The excitation energy in vacuum depends only on the molecular geometry,

while the electrochromic shift depends both on the geometry and on

the electrostatic potential generated by the environment.

, as detailed in the following

section.

The excitation energy in vacuum depends only on the molecular geometry,

while the electrochromic shift depends both on the geometry and on

the electrostatic potential generated by the environment.

Following

a strategy similar to ref (47), we have modeled the vacuum contribution  with Gaussian Process regression46 (GPR)

using the Matern kernel with ν =

2.5

with Gaussian Process regression46 (GPR)

using the Matern kernel with ν =

2.5

| 9 |

where d = ∥xCM – x′CM∥ is the Euclidean distance between the two points and λ is the length scale parameter of the kernel.

The electrochromic shift  was modeled with a composite kernel, where

the direct environment contribution to the shift is complemented with

an interaction term weighting the response by the internal geometry

of the carotenoid

was modeled with a composite kernel, where

the direct environment contribution to the shift is complemented with

an interaction term weighting the response by the internal geometry

of the carotenoid

| 10 |

where x = (xCM,xpot) is the molecular descriptor

of the carotenoid in the environment, comprising both the CM and the

electrostatic potential,  is the kernel expressing the direct contribution

of the environment, depending only on the electrostatic potential,

is the kernel expressing the direct contribution

of the environment, depending only on the electrostatic potential,  is a kernel describing the internal geometry

of the molecule, with the same functional form as eq 9, and β is a variance parameter

that provides a different weight to direct and interaction contributions

in the total kernel. For the direct contribution, we evaluated the

performance of a linear kernel

is a kernel describing the internal geometry

of the molecule, with the same functional form as eq 9, and β is a variance parameter

that provides a different weight to direct and interaction contributions

in the total kernel. For the direct contribution, we evaluated the

performance of a linear kernel

| 11 |

as was used for chlorophylls in ref (47), and a polynomial kernel of degree 2 without an intercept

| 12 |

where θ is an offset parameter used to weight differently the linear and quadratic terms. Both kernels are thus constrained to predict a vanishing electrochromic shift when the electrostatic potential is zero.

Given a point z, the vacuum  and the solvatochromic shift

and the solvatochromic shift  contributions are predicted as a linear

combination of kernel evaluations with the training points

contributions are predicted as a linear

combination of kernel evaluations with the training points

| 13 |

where  is

is  (eq 9) for the vacuum case and

(eq 9) for the vacuum case and  (eq 10) for the environment case. The coefficients

α are obtained

from the solution of

(eq 10) for the environment case. The coefficients

α are obtained

from the solution of  , where

, where  is the

matrix of kernel evaluations of

the N train points,

is the

matrix of kernel evaluations of

the N train points,  is the

identity matrix, and

is the

identity matrix, and  is a vector collecting the excitation energies

(

is a vector collecting the excitation energies

( or

or  ) in the train data set.

Kernel hyperparameters

have been determined by maximizing the log marginal likelihood with

the L-BFGS-B algorithm. We note that

) in the train data set.

Kernel hyperparameters

have been determined by maximizing the log marginal likelihood with

the L-BFGS-B algorithm. We note that  was scaled to unit variance

when training

the environment models, while no standardization was applied to

was scaled to unit variance

when training

the environment models, while no standardization was applied to  in the vacuum models.

in the vacuum models.

The performance of the ML models has been measured by means of the mean absolute error (MAE)

| 14 |

where  and

and  denote the i-th prediction

and target, respectively, and N is the number of

points. As an additional score, we have used the squared Pearson correlation

coefficient (r2)

denote the i-th prediction

and target, respectively, and N is the number of

points. As an additional score, we have used the squared Pearson correlation

coefficient (r2)

| 15 |

where  is the average target energy.

The r2 measures the linear relationship

between the

prediction and the target.

is the average target energy.

The r2 measures the linear relationship

between the

prediction and the target.

2.3. Quantum Chemical Targets

The QM adiabatic

electronic energies of carotenoids were computed using a SE configuration

interaction (CI) approach,57 which proved

to be effective in the description of their low-lying excited states.40−42,58 This method performs a CI calculation

within an active space. The targets  and

and  used to train the ML models were obtained

by performing our diabatization strategy.

used to train the ML models were obtained

by performing our diabatization strategy.

In order to obtain

the electrochromic shift  , consistency between

the vacuum and the

environment calculations is mandatory. In methods that exploit an

active space, such as this SECI approach, if the SCF is solved separately

in vacuum and environment, the MOs in the active space can be inconsistent

between the two calculations, leading to an incorrect value of the

shift. This is clear from Figure S1, where

we report the overlap matrix between the vacuum active MO coefficients

for a representative geometry and the same coefficients obtained in

the QM/MM calculation in methanol. As we can see from the overlap

matrix, the first MO “exits” the active space when we

include the environment. The effect of inconsistency can be seen from

a scan over the MM charges that we reported in Figure S2. When the shift is obtained from two calculations

that use inconsistent MO coefficients, it shows unphysical discontinuities.

To overcome this issue, we performed the QM/MM calculations using

the MO coefficients obtained in the vacuum calculation of the same

geometry. The contribution of the relaxation of the MOs to the environment

is then recovered by the CI coefficients. In Figure S2, we see how this expedient allows us to recover the correct

trend in the shift. This was also verified by performing the scan

over the environment charges at the time-dependent density-functional

theory (TD-DFT)/M062X/6-31G(d) level (Figure S2), which is a well-established method for the calculation of the

1B+u excitation

energy. We can see that the shift of the bright diabatic state computed

with SECI with consistent MO coefficients is qualitatively comparable

with TD-DFT.

, consistency between

the vacuum and the

environment calculations is mandatory. In methods that exploit an

active space, such as this SECI approach, if the SCF is solved separately

in vacuum and environment, the MOs in the active space can be inconsistent

between the two calculations, leading to an incorrect value of the

shift. This is clear from Figure S1, where

we report the overlap matrix between the vacuum active MO coefficients

for a representative geometry and the same coefficients obtained in

the QM/MM calculation in methanol. As we can see from the overlap

matrix, the first MO “exits” the active space when we

include the environment. The effect of inconsistency can be seen from

a scan over the MM charges that we reported in Figure S2. When the shift is obtained from two calculations

that use inconsistent MO coefficients, it shows unphysical discontinuities.

To overcome this issue, we performed the QM/MM calculations using

the MO coefficients obtained in the vacuum calculation of the same

geometry. The contribution of the relaxation of the MOs to the environment

is then recovered by the CI coefficients. In Figure S2, we see how this expedient allows us to recover the correct

trend in the shift. This was also verified by performing the scan

over the environment charges at the time-dependent density-functional

theory (TD-DFT)/M062X/6-31G(d) level (Figure S2), which is a well-established method for the calculation of the

1B+u excitation

energy. We can see that the shift of the bright diabatic state computed

with SECI with consistent MO coefficients is qualitatively comparable

with TD-DFT.

2.4. Datasets

In the vacuum ML models, the training set of Lut, Neo, Vio, and Zea is composed of approximately 4000 geometries, extracted from classical MD simulations of each carotenoid in MeOH. For the specific case of Lut, the same structures are also used for the environment ML models in methanol. The training points used in the LHCII models, instead, were extracted from a classical MD simulation of LHCII published previously by some of us.59 In the training set of LHCII, the two binding sites of Lut, L1, and L2, are equally represented (2000 structures from each site).

In all cases, the sampling of the training points was performed with an active learning60 procedure (Figure 3). In each step of this iterative procedure, we train a GPR model using the carotenoid structure encoded with the CM as input and the vacuum excitation energies of the S1 adiabatic state as target. The training set for the first step is obtained by sampling 200 geometries from the MD with the farthest point sampling (FPS) algorithm,61 in the space given by the CM. The model is used to predict the excitation energies of all the geometries in the “pool” (the remaining frames of the MD trajectory). At this point, the 200 predictions with the highest variance are selected to expand the training set for the next step. The new sample of each step is used as a test set to evaluate the current model and build the learning curve (Figure S3).

Figure 3.

Scheme representing the active learning process used to obtain the data set. (a) Classical MD simulation of Lut in MeOH. (b) Sampling of 200 initial geometries using the FPS algorithm. (c) Active learning: the initial sample is used to train a GPR model, using as input the CM and as target the excitation energies of the S1 adiabatic state; the model is used to predict the excitation energies of the structures in the pool; the 200 points with the higher variance are selected for enlarging the training set. (d) Evaluation of the current model using the latest sample as the test set.

For the MD in methanol, the procedure was repeated until 4000 geometries were obtained. In the case of LHCII, the training data set was generated with active learning separately for Lut-L1 and Lut-L2. The samples for each site were extracted from all three monomers of the protein. We obtained two sets of 2000 geometries that were put together to form the complete training set.

The test data sets were extracted from the remaining frames of the MD trajectories using the FPS algorithm. We selected about 500 geometries for methanol and 700 for LHCII.

In the data sets we obtained (both for training and testing), a few geometries (less than 1%) presented a large transition dipole moment in the third adiabatic excited state (S3). Those points were therefore excluded from the data set since our diabatization strategy only considers combinations of S1 and S2 to generate diabatic states.

3. Computational Details

3.1. MD Simulations

For the classical MD simulations in methanol (MeOH) of all carotenoids, we have employed an octahedral box extending for about 30 Å from the carotenoid. Carotenoids’ parameters have been published previously,62 while MeOH was simulated with parameters from ref (63), as available in AMBER 18.64 The final box consisted of a carotenoid solvated with approximately 8500 methanol molecules. The solvent was first minimized while keeping the carotenoid fixed with harmonic restraints. The temperature of the system was gradually raised from 0 to 300 K in a 100-ps-long NPT simulation. This step was followed by an equilibration phase of 100 ns in the NVT ensemble, which is not included in the subsequent analyses. Finally, the system was simulated for 2 μs in the NVT ensemble with a Langevin thermostat, using an integration step of 2 fs. SHAKE was employed to constrain the hydrogen atoms. Long-range electrostatics were treated with particle mesh Ewald. All simulations were run with the GPU-accelerated AMBER 18 simulation suite.64

3.2. QM Calculations

The electronic states of carotenoids were computed using a SE FOMO-CI approach.57,65 This method performs a CI calculation within an active space, adopting a floating and fractional occupation of the molecular orbitals of the active space. In the FOMO-CI calculations, we employed an active space of 6 electrons in 9 molecular orbitals of π type, a Gaussian energy width for floating occupation of 0.1 hartree, and a determinant space including all single and double excitations within the orbital active space (CISD). Semiempirical parameters were specifically optimized for Lut.40 Additional calculations with TD-DFT were performed at the M062X/6-31G(d) level. For the environment calculations, we adopted an electrostatic embedding QM/MM scheme, in which the carotenoid is treated at the QM level and the environment is handled by a classical force field. For both MeOH and LHCII, we used the standard MM AMBER force field ff14SB.66 The membrane lipids were described by the lipid14 force field,67 whereas chlorophylls in LHCII were described by the force field by Zhang et al.68 For the QM/MM calculations, we considered a subsystem of the box performing a cutoff of 30 Å from the carotenoid. All the SE calculations were performed using a development version of the MOPAC code,69 interfaced with the Tinker 6.3 package for the QM/MM part.70 TD-DFT calculations were performed with Gaussian 16.71

3.3. Machine Learning

All the GPR models were trained using our locally developed Python package GPX.72 The CM and electrostatic potential descriptors, and the FPS algorithm are implemented in the Python package Moldex.73 Both packages were implemented in JAX74 and are available on GitHub under the GNU LGPL agreement.

4. Results and Discussion

As already mentioned, the modeling of the solvatochromism we carried out in this work relies on three different environments. One is pure methanol (MeOH), as we wanted to observe the electrochromic response of carotenoids in a homogeneous but polar solvent. The second is an artificial environment (which we call MeOH+q), obtained by adding to each MeOH configuration 5 positive and 5 negative charges at random positions within 30 Å from the carotenoid. Specifically, we added a positive/negative unit charge to the carbon/oxygen atom of randomly chosen MeOH molecules. This was done to enhance the electrochromic shift with respect to MeOH with the aim of obtaining an environment that is more similar to a protein with charged moieties close to the solute. The third environment is instead the LHCII.

4.1. Geometrical Effect and Vacuum Models

As a first step, we focused on the geometric component of the excitation energy using calculations of isolated (i.e., vacuum) carotenoids in different geometries to obtain the first block of the hierarchical models (see Section 2.2).

We trained the GPR models, as described in Section 2.2, with a training set of about 4000 structures (points) generated with active learning from the MD in MeOH. For each structure, we computed the carotenoid’s excitation energies without including the environment but keeping the geometry obtained in the solvent. These calculations were then used to train the ML models, which from now on are indicated as vacuum models.

Both the dark and bright states in vacuum have been fitted for the four different carotenoids (Lut, Neo, Vio, and Zea, Figure 1). We note that the models of the dark and bright states are independent from each other. The performance of all the vacuum models is shown in Figure 4. All the learning curves reach a plateau between 2000 and 3000 training points; hence, the models would not be improved by enlarging the training data set. The metrics evaluated on the test set are reported in Table 1. We notice that the bright states are better predicted than the dark states for all carotenoids. The lower quality of the dark state prediction may be related to the difficulty of correctly describing the diabatic 2A–g state and some degree of mixing between the 2A–g and other dark states. Another notable point is that among the different carotenoids, Neo models make less accurate predictions. Indeed, Neo presents an allenyl group with a s-cis conformation on one side and a double bond with a cis configuration on the other, so the molecule tends to be folded on itself in many frames. This causes larger geometrical fluctuations compared to the other carotenoids, which complicates the ML predictions. Furthermore, the allene bond is more difficult to describe with MM force fields. Although all carotenoid force fields were reparametrized in previous work,62 we expect a lower accuracy for the Neo geometries. This difficulty is not met when building models for the other carotenoids. In fact, the relationship between the geometry and the excitation energy is captured well by the GPR models for the other carotenoids, with a r2 always larger than 0.9 and a MAE smaller than the 22% of the standard deviation of the excitation energy along the MD.

Figure 4.

Performance of the vacuum GPR models. The models are trained on diabatic excitation energies. The models of the dark and bright states are independent from each other. We show data for Lut and Neo. The corresponding data for Vio and Zea is shown in Figure S4. In the left panels, we show the performance of the models of each state, trained on the full dataset of about 4000 points and tested on additional geometries extracted from MD in methanol. The Pearson’s r2 is shown in the inset. In the right panel, we report the learning curves of each model, showing the trend of the MAE and Pearson’s r2 as a function of the training set size. Both metrics are evaluated on the validation test, with 3-fold cross-validation as the average of the validation score. The shaded region around each curve represents the uncertainty, computed as twice the standard deviation of the validation score.

Table 1. List of the Scores on a Test Set of All the Vacuum Modelsa.

| dark state |

bright state |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r2 | MAE (meV) | % of y std | r2 | MAE (meV) | % of y std | |

| Lut | 0.95 | 40.7 | 17.2 | 0.94 | 22.1 | 19.3 |

| Neo | 0.76 | 92.5 | 37.9 | 0.76 | 47.6 | 37.0 |

| Vio | 0.93 | 45.4 | 21.2 | 0.94 | 22.3 | 19.8 |

| Zea | 0.96 | 33.8 | 16.2 | 0.96 | 16.4 | 15.9 |

We report Pearson’s r2 index, the MAE and it’s percentage of the target standard deviation.

Training our models on geometries simulated in MeOH allowed us to extensively sample the carotenoid conformational landscape in order to build GPR models that are robust to alterations of the carotenoid’s structure. However, we are particularly interested in the carotenoid’s response within a biological matrix such as a LHC. In order to validate our models when the carotenoid is placed into a LHC, we have used the Lut models on a test set extracted from a MD trajectory of LHCII59 (see Figure 5a). Lut is found in two different pockets (L1 and L2) of LHCII, which give rise to distinct spectral forms in the LHCII trimers.25,75,76 The test set includes structures from both the L1 and L2 sites of all three monomers that compose the protein.

Figure 5.

(a) Visual representation of LHCII. (b) Predictions of the GPR models for the dark and bright state of Lut on test geometries from a MD of LHCII.

Figure 5b shows that models trained on geometries extracted from the methanol MD trajectory reproduce well the vacuum excitation energy of Lut in the LHC for both the bright and dark states. This indicates that our training geometries are general enough to robustly predict the geometrical effect in very different environments. The geometries attained by Lut in LHCII are different from those in solvent, as demonstrated in Section S5 of the Supporting Information, which shows the different distributions of several internal coordinates in the two environments. Nonetheless, our model is still able to reproduce the relationship between geometry and excitation energy.

4.2. Direct Electrochromic Shift and the Electrostatic Effect

Having built the first building block of our hierarchical model, namely, the vacuum excitation energy, we now move on to the modeling of the electrochromic shift. We focus in particular on Lut for two reasons: first, its vacuum excitation energies were satisfactorily predicted by our models, and second, Lut is found in two different pockets in LHCII, which allows us to investigate more in depth the effect of different protein environments. For the sake of simplicity, in this section, we present and discuss only the bright state, while we report the analogous results for the dark state in Figure S8 of the Supporting Information.

In a previous work by some of us,47 a similar hierarchical model to the one employed here was built for the Qy transition in chlorophylls a and b. Specifically, a linear kernel (eq 11) was used to capture the direct contribution of the environment to the excitation energy, using as a descriptor the electrostatic potential of the environment acting on the atoms of the solute. However, the conjugated backbone in carotenoids is nearly symmetrical. For a symmetric molecule, the response to an electric potential should not change if the electric field is inverted, i.e., if the electric potential changes sign. This cannot be true for a linear function of the potential, where the sign of the response changes with the sign of the potential. To illustrate this issue, we introduce the “potential imbalance” Δpot, a quantity describing the difference of electrostatic potential between the two sides of the molecule. The potential imbalance is obtained by dividing the molecule into two parts (A and B) and subtracting the cumulative electrostatic potential between the parts

| 16 |

In particular, here, we have divided the carotenoid at the central double bond to follow the near symmetry of the polyene backbone in Lut (see Figure S7). In practice, Δpot represents the average electric field along the carotenoid backbone.

In order to focus on the direct contribution of the electrochromic shift, in this analysis we consider a case where the internal geometry of Lut is fixed. Furthermore, we consider the shifts calculated in the MeOH+q environment as we want to include strong electrochromic shifts induced without preferential asymmetries in the potential imbalance.

In Figure 6a, we

report the electrochromic shift calculated at QM/MM level as a function

of the “potential imbalance”. The obtained results clearly

show that the electrostatic response of Lut is not linear with the

potential. On the contrary,  has an approximately

quadratic dependence

on potential imbalance.

has an approximately

quadratic dependence

on potential imbalance.

Figure 6.

(a–c) Relationship between the electrochromic shift and the potential imbalance of the bright state of Lut. The same analysis of the dark state of Lut in different environments can be found in the Supporting Information (section S6). We consider a dataset where a fixed internal geometry of the carotenoid is put in different configurations of the environment, MeOH+q. We plot the shift obtained in three ways: (a) with QM/MM calculations, (b) as predicted by a ML model that uses a linear kernel for the direct contribution of the shift (eq 12), and (c) with the ML model that uses a degree 2 polynomial kernel. The quadratic dependence is fitted to the data in each plot, and the shaded area around the dashed line represents a 95% confidence interval. (d) Three representative limit cases of electrostatic potential calculated on Lut’s atoms. The color blue indicates a positive potential, and the color red indicates a negative potential. The value of the potential imbalance and electrochromic shift for (i–iii) is highlighted in panels (a–c) (yellow diamonds).

As we show in Figure 6b, a linear model is clearly not capable of distinguishing between a strongly asymmetric potential (case i in Figure 6d) and a symmetric potential (case ii). The linear kernel performs slightly better in LHCII (Figure S9b,d) because the distribution of potential imbalances is more skewed, but its performance remains poor (r2 = 0.67). Figure 6c shows that employing a polynomial kernel of degree 2, which includes quadratic effects, recovers a much better fit than a linear kernel, both in MeOH+q (Figure S9a,c, r2 = 0.98) and in LHCII (Figure S9b,d, r2 = 0.94). In summary, a polynomial kernel well captures the physics behind the electrochromic shift of lutein.

4.3. Electrochromic Shift in Different Environments

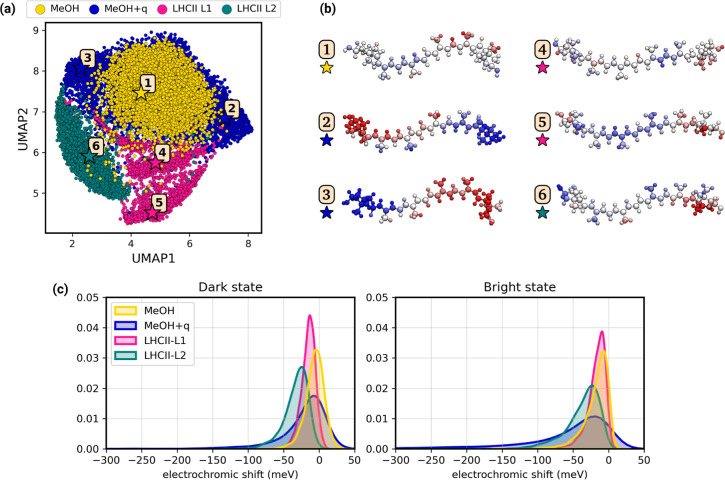

We are now able to analyze the similarities and differences between the environments employing the model developed in this work. To do so, we first represent the electrostatic configurations around Lut for the different environments through a dimensionality reduction technique. In particular, we use the UMAP algorithm,77 which is a dimensionality reduction method that can be used to visualize complex data sets in a concise way. With UMAP, a multidimensional feature vector can be projected into a two-dimensional space through a nonlinear function, which has the advantage of better compressing the data. On the other hand, distances between points in the UMAP space do not necessarily reflect distances in the original space. For this reason, the results of the UMAP should be carefully analyzed, as we do in the following. In Figure 7a we show the UMAP projection of the MM electrostatic potential in MeOH, MeOH+q and the two different binding sites for lutein in LHCII (L1 and L2). Each point corresponds to a different distribution of electrostatic potential on the Lut’s atoms.

Figure 7.

(a) UMAP77 projection of the MM electrostatic potential of the investigated solvents. The yellow dots correspond to the electrostatic potential of pure methanol (MeOH), the blue dots to methanol with additional charges (MeOH+q), and the pink and teal dots to the L1 and L2 sites of LHCII, respectively. Additional separate plots for each environment are shown in Figure S10. (b) Visual representation of the electrostatic potential on the atoms of Lut in 6 representative data points. The yellow star corresponds to a structure in MeOH, the blue stars to MeOH+q, the pink stars to LHCII-L1, and the teal star to LHCII-L2. A positive electrostatic potential is depicted in blue, while a negative potential is depicted in red. (c) Distributions of the solvatochromic shift in different environments (MeOH in yellow, MeOH+q in blue, L1 of LHCII in pink, and L2 of LHCII in teal) in the dark (left) and the bright state (right).

Strikingly, the LHCII environment is projected onto a different region from MeOH and MeOH + q (Figure 7a), and the two sites where Lut is located (L1 and L2) are separated by the first component. In other words, the variety of electrostatic configurations explored in the MeOH and MeOH+q solvents does not include those experienced inside the protein, and the two protein pockets of LHCII give rise to significantly different electrostatics. Regarding LHCII, the electrostatic environment of Lut L1 looks more similar to the homogeneous solvent case. Indeed, Figure 7c shows that the electrochromic shift induced by the L1 site is very similar to the shift in MeOH, especially for the bright state, while Lut L2 shows a larger shift. Instead, MeOH+q produces large negative shifts that are not observed in MeOH and LHCII, but the maximum of its distribution is still close to zero, as observed for MeOH (Figure 7c).

Interestingly, placing additional charges as done in MeOH+q is not sufficient to reproduce the electrostatic configurations experienced by Lut within the LHCII protein. The environment charge distribution is instead very specific to each protein pocket. This gives a narrower distribution of electrochromic shifts (Figure 7c) that is different for the two protein pockets and not necessarily comparable to that in solvent.

By comparing the picture given by Figure 7a,c, it can be seen that similar electrochromic shifts can be the result of fairly different environments: for example, the bright state experiences the same electrochromic shifts in the L1 pocket of LHCII and in MeOH, but the electrostatic configurations that give rise to these shifts are clearly different. This difference becomes apparent again when looking at the shifts in the dark state.

This analysis shows that the electrostatic configurations experienced by Lut in LHCII are not a subset of those in MeOH, either with or without added charges, even though for some properties they may give the same effect. For this reason, the photophysical properties in a solvent may not be fully representative of the same properties within a protein (and vice versa), even when the bright excited state shows the same shifts. We hypothesize that investigating the photophysics and photochemistry of carotenoids within a homogeneous solvent may fall short of explaining many aspects of the excited-state dynamics that occur in the protein environment.

In order to better understand the peculiarities of the electrostatics experienced in these environments, we have extracted Lut conformations from the UMAP and projected the electrostatic potential over the carotenoid atoms (Figure 7b). Points 1, 2, and 3 show that the configurations explored in MeOH and MeOH+q strongly correlate with the potential imbalance between the two halves of the lutein (Figure S7), which is strongly associated with a red shift in the excitation energies (Figure S11). Moving from MeOH/MeOH+q to the Lut L1 environment (Figure 7b, points 1, 4, and 5), the differences in the electrostatic potential are less pronounced, and not anymore related to the potential imbalance. Instead, we have a transition to more complex distributions of electrostatic potential along the carotenoid, with alternating localized regions of positive and negative electrostatic potential. Such local effects are induced by close-lying residues in the L1 pocket and become important to fine-tune the excited state properties of Lut in LHCII. Finally, Lut in L2 (point 6) shares similar features with Lut-L1, showing strong potential localization along its chain. Still, at variance with Lut-L1, Lut-L2 also experiences a larger potential imbalance, which eventually results in larger electrochromic shifts for both dark and bright states (Figure 7c).

We remark here that the internal geometry of the chromophore can modulate the response to the electrostatic potential of the environment; therefore, the electrochromic shift does not depend exclusively on the electrostatic potential. Nonetheless, the electrostatic configurations of Figure 7a,b can be used, at least qualitatively, to explain the shift distributions of Figure 7c.

Having analyzed the differences among the three environments, we now assess the generalization power of a regression model trained on each environment separately. To do so, for each state of Lut, we trained three separate GPR models in MeOH, MeOH+q, and LHCII (learning curves in Figure S12). Then, we used the three models to make predictions of the solvatochromic shift in the physical environments of MeOH and LHCII. The results of this cross-learning test are reported in Figure 8. We can see that all models extrapolate sufficiently well to different environments, with a r2 above 0.8/0.7 for the bright and dark states, respectively. As we have observed for the vacuum model, the difficulties in predicting the dark state shift are rooted in the diabatization technique. Furthermore, the dark state is less affected by the environment and thus presents smaller shifts that are harder to learn as compared to the bright state.

Figure 8.

Cross-learning of the electrochromic shift of the diabatic states (dark/bright) of Lut in MeOH (orange/yellow) and LHCII (dark/light pink). (a) Representation of the environments used for training the GPR models: MeOH (orange), MeOH+q (blue), and LHCII (pink). (b) Performance of each model on a test set of MeOH and LHCII. In the upper left corner of each plot, it is reported which model is used in each environment (e.g., MeOH → LHCII means that the ML model trained in MeOH is used to predict the electrochromic shift in LHCII). The r2 Pearson’s index of each model is reported in the inset.

In this cross-learning test, we noticed that the MeOH models perform as well as the MeOH+q models in extrapolating to LHCII (bottom row of Figure 8). In addition, the model directly trained on LHCII performs only marginally better than the other two. Although in the protein pocket(s) Lut experiences substantially different electrostatic potentials from MeOH/MeOH+q (Figure 7a), the models trained on the latter environments are still able to predict the electrochromic shifts in protein. All the models are also able to capture the difference between the solvatochromic effect in the two sites of LHCII to a few meV (Figure S13 and Table S1). From a practical point of view, this suggests a broader applicability of the model trained here to other unknown protein environments. More generally, this test demonstrates that the electrostatic potential descriptor, together with the internal geometry, contains all the information needed to explain the response of the chromophore to the charges of the environment. In turn, this enables more detailed analyses of the factors determining the electrochromic shifts, as we have shown with the UMAP projection in Figure 7a.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we have used ML to understand solvatochromism in complex molecules when moving from a solvent to a protein matrix. The approach has been applied to a specific family of molecules, the carotenoids, due to the unique sensitivity of their low-energy excitation energies to external perturbations.

Our strategy is based on learning the bright and dark diabatic states obtained from a diabatization based on transition dipoles from the ground state and predicting the energy with a hierarchical approach, where the electrochromic shift is added on top of a vacuum contribution. We demonstrate that the electrochromic shift is best captured by a ML model that takes into account the symmetrical response of the carotenoid to the external electrostatic field.

Our results show that the variety of electrostatic configurations found in a homogeneous solvent cannot account for the specificity of the protein environment, even when extra charges are added to the solvent. In a protein environment, indeed, the peculiarity of the protein pocket is crucial in determining how the electrostatic potential is distributed onto the molecule’s atoms. In this way, different protein pockets, such as L1 and L2 lutein binding sites in LHCII, can give rise to different electrochromic effects.

In spite of the marked difference in electrostatic potential between LHCII and the homogeneous solvent MeOH, the ML models trained on MeOH electrochromic shifts performed almost as well on LHCII as those trained directly on the same protein. Besides showing the soundness of the proposed electrostatic descriptors, this result also implies that it is not necessary to train these models specifically in each protein environment, but good performance can be expected in unseen environments, provided that enough training points are considered. We thus envision the possibility of calculating excitation energies along MD simulations of carotenoids in various environments with pretrained ML models without additional calculations. In addition, the models and descriptors proposed here can be used as a tool to complement or analyze QM/MM calculations. To increase the performance of a pretrained model, it is important to build a training set that includes the variety of anisotropies found in proteins. Adding artificial charges seems like a promising avenue, but the strategy of charge placement should be improved. We plan to explore alternative strategies in future work.

We finally note that within this work we have considered the effect of a purely electrostatic environment on the excitation energy of carotenoids. Nonetheless, it is known that their excitation energy also depends on the polarizability of the medium, especially in nonpolar solvents.21,23 This is a different physical mechanism than those investigated here, and its quantum chemical modeling requires polarizable embedding QM/MM methods.14 Furthermore, additional physical constraints should be built into the ML models to properly capture this effect.47 This additional effect is currently being investigated in our group.

Acknowledgments

E.C. and B.M. acknowledge funding by the European Research Council under the grant ERC-AdG-786714 (LIFETimeS). A.A., L.C., and B.M. acknowledge financial support from Italian MUR through the PRIN 2022 grant 2022N8PBLM (PhotoControl).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpca.4c00249.

Details on the semiempirical CI calculations; details of the scan over the MM charges; details on the active learning strategy; details on the definition of potential imbalance and the potential imbalance in MeOH, MeOH + q, and LHCII; performance of the linear and polynomial kernels in MeOH + q and LHCII; additional analysis of the UMAP projection of the environments; and learning curves for the ML models of the solvatochromic shift (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of The Journal of Physical Chemistry A virtual special issue “Gustavo Scuseria Festschrift”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Reichardt C. Solvatochromic Dyes as Solvent Polarity Indicators. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2319–2358. 10.1021/cr00032a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J. Hybrid Quantum and Molecular Mechanical Simulations: An Alternative Avenue to Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996, 29, 298–305. 10.1021/ar950140r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Implicit Solvation Models: Equilibria, Structure, Spectra, and Dynamics. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 2161–2200. 10.1021/cr960149m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi J.; Mennucci B.; Cammi R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3094. 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J. M.; Aidas K.; Mikkelsen K. V.; Kongsted J. Solvatochromic Shifts in Uracil: A Combined MD-QM/MM Study. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 249–256. 10.1021/ct900502s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurence C.; Legros J.; Chantzis A.; Planchat A.; Jacquemin D. A Database of Dispersion-Induction DI, Electrostatic ES, and Hydrogen Bonding α1 and β1 Solvent Parameters and Some Applications to the Multiparameter Correlation Analysis of Solvent Effects. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 3174–3184. 10.1021/jp512372c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budzák Š.; Laurent A. D.; Laurence C.; Medved’ M.; Jacquemin D. Solvatochromic Shifts in UV–Vis Absorption Spectra: The Challenging Case of 4-Nitropyridine N-Oxide. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 1919–1929. 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoli L.; Giovannini T.; Cappelli C. Assessing the Quality of QM/MM Approaches to Describe Vacuo-to-Water Solvatochromic Shifts. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 157, 214101. 10.1063/5.0118664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Humeniuk A.; Glover W. J. Conical Intersections in Solution With Polarizable Embedding: Integral-Exact Direct Reaction Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2022, 18, 6826–6839. 10.1021/acs.jctc.2c00662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco M.; Luque F. J. Theoretical Methods for the Description of the Solvent Effect in Biomolecular Systems. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 4187–4226. 10.1021/cr990052a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn H. M.; Thiel W. QM/MM Methods for Biomolecular Systems. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1198–1229. 10.1002/anie.200802019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morzan U. N.; Alonso de Armiño D. J.; Foglia N. O.; Ramírez F.; González Lebrero M. C.; Scherlis D. A.; Estrin D. A. Spectroscopy in Complex Environments From QM–MM Simulations. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4071–4113. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennucci B.; Corni S. Multiscale Modelling of Photoinduced Processes in Composite Systems. Nat. Rev. Chem 2019, 3, 315–330. 10.1038/s41570-019-0092-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondanza M.; Nottoli M.; Cupellini L.; Lipparini F.; Mennucci B. Polarizable Embedding QM/MM: The Future Gold Standard for Complex (Bio)systems?. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 14433–14448. 10.1039/D0CP02119A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H.; Sugai Y.; Uragami C.; Gardiner A. T.; Cogdell R. J. Natural and Artificial Light-Harvesting Systems Utilizing the Functions of Carotenoids. J. Photochem. Photobiol., C 2015, 25, 46–70. 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2015.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polívka T.; Frank H. A. Molecular Factors Controlling Photosynthetic Light Harvesting by Carotenoids. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1125–1134. 10.1021/ar100030m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank H. A.; Bautista J. A.; Josue J.; Pendon Z.; Hiller R. G.; Sharples F. P.; Gosztola D.; Wasielewski M. R. Effect of the Solvent Environment on the Spectroscopic Properties and Dynamics of the Lowest Excited States of Carotenoids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 4569–4577. 10.1021/jp000079u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polívka T.; Sundström V. Ultrafast Dynamics of Carotenoid Excited States-From Solution to Natural and Artificial Systems. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2021–2072. 10.1021/cr020674n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H.; Zhang P.; Wang C.; Liu Z.; Chang W. Two Lutein Molecules in LHCII Have Different Conformations and Functions: Insights Into the Molecular Mechanism of Thermal Dissipation in Plants. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 355, 457–463. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renge I.; Sild E. Absorption Shifts in Carotenoids—influence of Index of Refraction and Submolecular Electric Fields. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2011, 218, 156–161. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2010.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Pinto M. M.; Sansiaume E.; Hashimoto H.; Pascal A. A.; Gall A.; Robert B. Electronic Absorption and Ground State Structure of Carotenoid Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 11015–11021. 10.1021/jp309908r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liguori N.; Xu P.; van Stokkum I. H.; van Oort B.; Lu Y.; Karcher D.; Bock R.; Croce R. Different Carotenoid Conformations Have Distinct Functions in Light-Harvesting Regulation in Plants. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1994. 10.1038/s41467-017-02239-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llansola-Portoles M. J.; Pascal A. A.; Robert B. Electronic and Vibrational Properties of Carotenoids: From in Vitro to in Vivo. J. R. Soc., Interface 2017, 14, 20170504. 10.1098/rsif.2017.0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcolin G.; Collini E. Solvent-Dependent Characterization of Fucoxanthin Through 2D Electronic Spectroscopy Reveals New Details on the Intramolecular Charge-Transfer State Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 4833–4840. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c00851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Pinto M. M.; Galzerano D.; Telfer A.; Pascal A. A.; Robert B.; Ilioaia C. Mechanisms Underlying Carotenoid Absorption in Oxygenic Photosynthetic Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 18758–18765. 10.1074/jbc.M112.423681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H.; Uragami C.; Yukihira N.; Gardiner A. T.; Cogdell R. J. Understanding/Unravelling Carotenoid Excited Singlet States. J. R. Soc., Interface 2018, 15, 20180026. 10.1098/rsif.2018.0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polívka T.; Sundström V. Dark Excited States of Carotenoids: Consensus and Controversy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 477, 1–11. 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tavan P.; Schulten K. The Low-Lying Electronic Excitations in Long Polyenes: A PPP-MRD-CI Study. J. Chem. Phys. 1986, 85, 6602–6609. 10.1063/1.451442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroumov E.; Müller M. G.; Marian C. M.; Kleinschmidt M.; Holzwarth A. R. Electronic Coherence Provides a Direct Proof for Energy-Level Crossing in Photoexcited Lutein and β-Carotene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 108302. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.108302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmidt M.; Marian C. M.; Waletzke M.; Grimme S. Parallel multireference configuration interaction calculations on mini-β-carotenes and β-carotene. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 044708. 10.1063/1.3062842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M.; Tavan P. Electronic Excitations in Long Polyenes Revisited. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 124309. 10.1063/1.3696880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götze J. P.; Thiel W. TD-DFT and DFT/MRCI Study of Electronic Excitations in Violaxanthin and Zeaxanthin. Chem. Phys. 2013, 415, 247–255. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2013.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taffet E. J.; Lee B. G.; Toa Z. S. D.; Pace N.; Rumbles G.; Southall J.; Cogdell R. J.; Scholes G. D. Carotenoid Nuclear Reorganization and Interplay of Bright and Dark Excited States. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 8628–8643. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b04027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei T.; Balevičius V.; Polívka T.; Ruban A. V.; Duffy C. D. P. How Carotenoid Distortions May Determine Optical Properties: Lessons From the Orange Carotenoid Protein. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 23187–23197. 10.1039/C9CP03574E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov D.; Belov A. Ab Initio Study of Low-Lying Excited States of Carotenoid-Derived Polyenes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 5790–5803. 10.1021/acs.jpca.0c01678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov D.; Belov A. Toward an Accurate Ab Initio Description of Low-Lying Singlet Excited States of Polyenes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 4301–4315. 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c01293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loco D.; Buda F.; Lugtenburg J.; Mennucci B. The Dynamic Origin of Color Tuning in Proteins Revealed by a Carotenoid Pigment. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 2404–2410. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b00763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondanza M.; Cupellini L.; Lipparini F.; Mennucci B. The Multiple Roles of the Protein in the Photoactivation of Orange Carotenoid Protein. Chem 2020, 6, 187–203. 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondanza M.; Jacquemin D.; Mennucci B. Excited States of Xanthophylls Revisited: Toward the Simulation of Biologically Relevant Systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 6604–6612. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c01929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accomasso D.; Arslancan S.; Cupellini L.; Granucci G.; Mennucci B. Ultrafast Excited-State Dynamics of Carotenoids and the Role of the SX State. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 6762–6769. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c01555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono A.; Accomasso D.; Cupellini L.; Mennucci B. How Orange Carotenoid Protein Controls the Excited State Dynamics of Canthaxanthin. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 11158–11169. 10.1039/D3SC02662K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza González L.; Accomasso D.; Cupellini L.; Granucci G.; Mennucci B. Ultrafast Excited-State Dynamics of Luteins in the Major Light-Harvesting Complex LHCII. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2024, 23, 303–314. 10.1007/s43630-023-00518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith J. A.; Vassilev-Galindo V.; Cheng B.; Chmiela S.; Gastegger M.; Müller K. R.; Tkatchenko A. Combining Machine Learning and Computational Chemistry for Predictive Insights Into Chemical Systems. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 9816–9872. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermayr J.; Marquetand P. Machine Learning for Electronically Excited States of Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 9873–9926. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dral P. O.; Barbatti M. Molecular Excited States Through a Machine Learning Lens. Nat. Rev. Chem 2021, 5, 388–405. 10.1038/s41570-021-00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deringer V. L.; Bartók A. P.; Bernstein N.; Wilkins D. M.; Ceriotti M.; Csányi G. Gaussian Process Regression for Materials and Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 10073–10141. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cignoni E.; Cupellini L.; Mennucci B. Machine Learning Exciton Hamiltonians in Light-Harvesting Complexes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 965–977. 10.1021/acs.jctc.2c01044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead C. A.; Truhlar D. G. Conditions for the Definition of a Strictly Diabatic Electronic Basis for Molecular Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 6090–6098. 10.1063/1.443853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y.; Varga Z.; Kanchanakungwankul S.; Zhang L.; Truhlar D. G. Diabatic States of Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 992–1018. 10.1021/acs.jpca.1c10583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Meyer W. McSCF Study of the Avoided Curve Crossing of the Two Lowest 1Σ+ States of LiF. J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 74, 5802–5807. 10.1063/1.440893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer C. E.; Xu X.; Ma D.; Gagliardi L.; Truhlar D. G. Diabatization Based on the Dipole and Quadrupole: The DQ Method. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 114104. 10.1063/1.4894472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer C. E.; Parker K.; Gagliardi L.; Truhlar D. G. The DQ and DQΦ Electronic Structure Diabatization Methods: Validation for General Applications. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 194101. 10.1063/1.4948728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sršeň Š.; von Lilienfeld O. A.; Slavíček P. Fast and Accurate Excited States Predictions: Machine Learning and Diabatization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 4306–4319. 10.1039/D3CP05685F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. M. G.; Eisfeld W. Neural Network Diabatization: A New Ansatz for Accurate High-Dimensional Coupled Potential Energy Surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 149, 204106. 10.1063/1.5053664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accomasso D.; Persico M.; Granucci G. Diabatization by Localization in the Framework of Configuration Interaction Based on Floating Occupation Molecular Orbitals (FOMO-CI). ChemPhotoChem 2019, 3, 933–944. 10.1002/cptc.201900056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp M.; Tkatchenko A.; Müller K. R.; von Lilienfeld O. A. Fast and Accurate Modeling of Molecular Atomization Energies With Machine Learning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 058301. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.058301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granucci G.; Toniolo A. Molecular Gradients for Semiempirical CI Wavefunctions With Floating Occupation Molecular Orbitals. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 325, 79–85. 10.1016/S0009-2614(00)00691-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Accomasso D.; Londi G.; Cupellini L.; Mennucci B. The Nature of Carotenoid S* State and Its Role in the Nonphotochemical Quenching of Plants. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 847. 10.1038/s41467-024-45090-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupellini L.; Calvani D.; Jacquemin D.; Mennucci B. Charge Transfer From the Carotenoid Can Quench Chlorophyll Excitation in Antenna Complexes of Plants. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 662. 10.1038/s41467-020-14488-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. S.; Nebgen B.; Lubbers N.; Isayev O.; Roitberg A. E. Less Is More: Sampling Chemical Space With Active Learning. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 241733. 10.1063/1.5023802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochbaum D. S.; Shmoys D. B. A Best Possible Heuristic for the K-Center Problem. Math. Oper. Res. 1985, 10, 180–184. 10.1287/moor.10.2.180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prandi I. G.; Viani L.; Andreussi O.; Mennucci B. Combining Classical Molecular Dynamics and Quantum Mechanical Methods for the Description of Electronic Excitations: The Case of Carotenoids. J. Comput. Chem. 2016, 37, 981–991. 10.1002/jcc.24286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieplak P.; Caldwell J.; Kollman P. Molecular Mechanical Models for Organic and Biological Systems Going Beyond the Atom Centered Two Body Additive Approximation: Aqueous Solution Free Energies of Methanol and N-methyl Acetamide, Nucleic Acid Base, and Amide Hydrogen Bonding and Chloroform/Water Partition Coefficients of the Nucleic Acid Bases. J. Comput. Chem. 2001, 22, 1048–1057. 10.1002/jcc.1065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Case D. A.; Ben-Shalom I. Y.; Brozell S. R.; Cerutti D. S.; Cheatham T. E. III; Cruzeiro V. W. D.; Darden T. A.; Duke R.; Ghoreishi D.; et al. Amber 18; University of California: San Francisco, 2018..

- Silva-Junior M. R.; Thiel W. Benchmark of Electronically Excited States for Semiempirical Methods: MNDO, AM1, PM3, OM1, OM2, OM3, INDO/S, and INDO/S2. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010, 6, 1546–1564. 10.1021/ct100030j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier J. A.; Martinez C.; Kasavajhala K.; Wickstrom L.; Hauser K. E.; Simmerling C. Ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters From Ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–3713. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson C. J.; Madej B. D.; Skjevik A. A.; Betz R. M.; Teigen K.; Gould I. R.; Walker R. C. Lipid14: The Amber Lipid Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10, 865–879. 10.1021/ct4010307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Silva D.-A.; Yan Y.; Huang X. Force Field Development for Cofactors in the Photosystem II. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 1969–1980. 10.1002/jcc.23016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. J.MOPAC2002; Fujitsu Limited: Tokyo, Japan, 2002..

- Ponder J. W.TINKER—Software Tools for Molecular Design, Version 6.3, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Frisch M.; Trucks G.; Schlegel H.; Scuseria G.; Robb M.; Cheeseman J.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G.; Nakatsuji H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision A. 03; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2016; Vol. 3.

- Cignoni E.; Mazzeo P.; Arcidiacono A.; Cupellini L.; Mennucci B.. GPX: Gaussian Process Regression in JAX. 2023, https://github.com/Molecolab-Pisa/GPX (accessed August 1, 2024).

- Arcidiacono A.; Mazzeo P.; Cignoni E.; Cupellini L.; Mennucci B.. Moldex: Molecular Descriptors in JAX. 2023, https://github.com/Molecolab-Pisa/moldex.

- Bradbury J.; Frostig R.; Hawkins P.; Johnson M. J.; Leary C.; Maclaurin D.; Necula G.; Paszke A.; VanderPlas J.; Wanderman-Milne S.. et al. JAX: Composable Transformations of Python+NumPy Programs. 2018, http://github.com/google/jax (accessed August 1, 2024).

- Son M.; Pinnola A.; Bassi R.; Schlau-Cohen G. S. The Electronic Structure of Lutein 2 Is Optimized for Light Harvesting in Plants. Chem 2019, 5, 575–584. 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Artes Vivancos J. M.; Van Stokkum I. H.; Saccon F.; Hontani Y.; Kloz M.; Ruban A.; van Grondelle R.; Kennis J. T. Unraveling the Excited-State Dynamics and Light-Harvesting Functions of Xanthophylls in Light-Harvesting Complex II Using Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 17346–17355. 10.1021/jacs.0c04619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes L.; Healy J.; Melville J.. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. 2018, arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03426 (accessed Jan 11, 2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.