Abstract

Inhibition of hypoxanthine–guanine–xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase activity decreases the pool of 6-oxo and 6-amino purine nucleoside monophosphates required for DNA and RNA synthesis, resulting in a reduction in cell growth. Therefore, inhibitors of this enzyme have potential to control infections, caused by Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, Trypanosoma brucei, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Helicobacter pylori. Five compounds synthesized here that contain a purine base covalently linked by a prolinol group to one or two phosphonate groups have Ki values ranging from 3 nM to >10 μM, depending on the structure of the inhibitor and the biological origin of the enzyme. X-ray crystal structures show that, on binding, these prolinol-containing inhibitors stimulated the movement of active site loops in the enzyme. Against TBr in cell culture, a prodrug exhibited an EC50 of 10 μM. Thus, these compounds are excellent candidates for further development as drug leads against infectious diseases as well as being potential anticancer agents.

Introduction

Infectious diseases are a scourge in the world today prompting the search for previously untried drug targets, which will result in new drug therapeutics. A recognized way to reduce the replication and survival of any cell is to halt DNA/RNA production. This approach proved successful in the development of the antivirals adefovir, cidofovir, and tenofovir.1 These drugs act by selective inhibition of the polymerases and by inserting foreign nucleotides into the growing DNA chain, causing premature chain termination.1 Nucleic acid production can also be restricted by inhibiting the synthesis of the precursor molecules, the purine nucleoside monophosphates. These essential metabolites are synthesized by two pathways: de novo and/or the salvage of purine bases or nucleosides. Humans possess the enzymatic machinery to use both routes while other organisms may have to rely completely on salvage. These include the parasites, Plasmodium falciparum (Pf) and Plasmodium vivax (Pv), which have circumvented the energetically demanding de novo pathway2,3 and have evolved to salvage the purine bases and nucleosides they need from the host cell (Figure 1). The key enzyme in the salvage pathway is hypoxanthine–guanine–(xanthine) phosphoribosyltransferase (HG(X)PRT)4 (Figure 1). The xanthine in brackets in the abbreviated name acknowledges the fact that only three of these enzymes P. falciparum (Pf),5Helicobacter pylori (Hp),6 and Escherichia coli (Ec)7 are able to recognize xanthine as a substrate while the other four enzymes studied here cannot (human,8Pv,9Trypanosoma brucei (TBr),10 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mt)).11 Thus, it is proposed that inhibition of HG(X)PRT activity will be effective in arresting the proliferation of these cells. It has previously been reported that Plasmodium cells can transport AMP but how relevant this is to the overall mononucleotide pool is yet to be ascertained.12 Purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) is also a centrally important enzyme in the salvage pathway, using purine nucleosides and phosphate as substrates to produce the purine base and ribose-1-phosphate (Figure 1).13

Figure 1.

6-Oxo purine and the 6-amino purine nucleoside monophosphate synthetic pathways via salvage. (a) The first pathway for the synthesis of the 6-oxo purine and the 6-amino purine nucleoside monophosphates. (b) The second salvage pathway for the synthesis of the 6-amino and 6-oxopurine nucleoside monophosphates in TBr and Hp. ADA, AMP deaminase; IMPDH, IMP dehydrogenase; GMPS, GMP synthase; PNP, purine nucleoside phosphorylase. R = H (hypoxanthine) or −NH2 (guanine) or = O (xanthine). The molecules in the rectangles are imported from the host cell.

In contrast, TBr and Hp, while also being unable to synthesize the purine ring,14−18 possess two additional enzymes, adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (APRT) and adenosine kinase (AK).17−20 Therefore, this parasite and this bacterium are also able to utilize adenine and adenosine as a source of their nucleotides (Figure 1).

However, in these two organisms, studies have shown that HG(X)PRT activity is crucial for growth and function. In TBr, this was demonstrated by double RNAi silencing10 while, in Hp, this was demonstrated by the need for exogenous purine bases/nucleosides.18TBr parasites cause Human and Animal African Trypanosomiases (HAT and AAT). Although HAT caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense is progressing toward elimination of transmission and as public health problem, respectively,21 AAT continues to represent a significant economic burden due to lower meat and milk production, especially in affected areas of Sub-Saharan Africa. Mtb does indeed possess both de novo and salvage, but Griffin et al. used random transposon mutagenesis to identify that the hpt gene is essential for growth.22 In addition, human HGPRT is also being recognized more widely as a target for drug discovery against human cancers.23−26 Taken together, these studies demonstrate the crucial role that HG(X)PRT activity plays in almost all organisms.

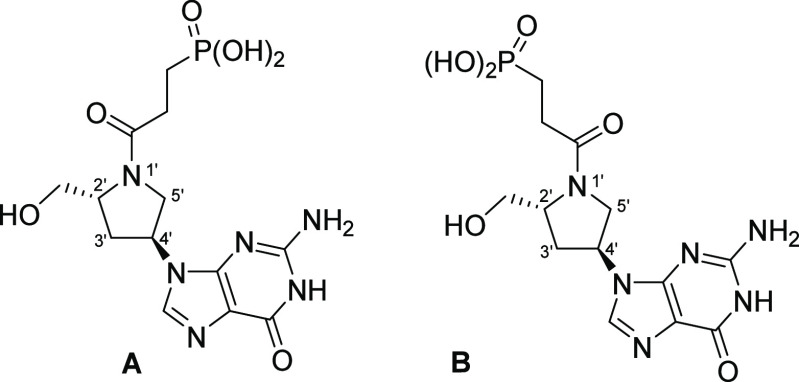

Using target-based design, compounds have been synthesized and examined for their ability to inhibit HG(X)PRT from several sources, including human, Pf, Pv, Escherichia coli, Mt, Hp and TBr. Noting that TBr possesses three isoforms identified as HGPRT1, HGPRT2, and HGXPRT, HGPRT1 is localized in the cytoplasm whereas the other two enzymes are found in the glyocosome of TBr.(10) The scaffolds of these inhibitors are based on mimicking the substrates, products, and transition-state analogues of the enzymatic reaction. Figure 2A shows the structure of the nucleoside monophosphate product of the reaction catalyzed by HG(X)PRT together with that of the transition-state analogues of the catalytic reaction, (1S)-1-(9-deazahypoxanthin-9-yl)-1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-d-ribitol 5-phosphate (ImmHP) and (1S)-1-(9-deazaguanin-9-yl)-1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-d-ribitol 5-phosphate (ImmGP; Figure 2B).27 The transition-state analogues are not ideal as drug leads since the phosphate group is susceptible to chemical/enzymatic hydrolysis in vivo.27

Figure 2.

(A) The nucleoside monophosphates, IMP, GMP, and XMP. R is −NH2 (guanine), −H (hypoxanthine), or =O (xanthine). (B) The transition-state analogues, ImmHP or ImmGP.

A major advance in inhibitor design was to replace the phosphate group with a stable phosphonate group.28 A second was to engineer into the design a different sequence of atoms into the linker connecting the purine base to the phosphonate group.29−32 One idea was to introduce different heterocycles into this linker representing, in part, the ribose ring of the mononucleotide product of the catalytic reaction (Figure 2A). The scaffolds for these inhibitor designs are given in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Phosphonate inhibitors of HG(X)PRT containing different heterocycle groups in the linker. The green bracket indicates where the linker can be further chemically modified to enhance affinity. (A) Pyrrolidines.33,34 (B) Imidazolines.35 (C) Imidazoles.35 (D) Triazoles.35 (E) Piperazines.36 (F) Piperidines.36

The Ki values for these compounds vary from 1.3 ± 0.5 and 2 ± 0.5 nM for [3R,4R]-4-hypoxanthin-9-yl-3-((S)-2-hydroxy-2-phosphonoethyl)oxy-1-N-(phosphonopropionyl)pyrrolidine with human HGPRT and PfHGXPRT, respectively,37 to >10 μM for diisopropyl (3-(2-(4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[3,2-d]pyrimidin-7-yl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)propyl)phosphonate with human HGPRT.35 The variability in the Ki values is attributed to three factors: (i) the organism from which the enzyme originates; (ii) the chemical structure of the heterocycle, which contributes to placing the functional groups in their optimal location; and (iii) the type of chemical groups attached to the heterocycle (Figure 3). The X-ray crystal structures of the best of these inhibitors with a HG(X)PRT from several organisms pointed the way for the design of the new inhibitors.

These newly synthesized compounds contain a different heterocycle in the linker (Figure 4). This is a d- or l-prolinol group, which is attached to the purine ring as the (S) or (R) isomer. The chemical versatility of the prolinol group allows for the attachment of different groups to the nitrogen or carbon atom to enhance binding in the active site of HG(X)PRT from humans, parasitic protozoa, bacterial, or mycobacterial origins. The scaffold for this design is given in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Scaffold for the design of the inhibitors containing a prolinol group in the linker. The arrows show the d- and l-enantiomers (orange arrow) and the isomeric attachment of the prolinol ring to the purine base (red arrow). The green brackets indicate areas where chemical modifications can be made. The base is also amenable to substitution with other purine bases.

Here, the Ki values for five such compounds have been measured against the H/G/X/PRTs from seven organisms. The / symbol signifies that these enzymes could have specificity for either one, two, or all three of the naturally occurring 6-oxopurine bases. The X-ray crystal structures of three of the prolinol inhibitors in complex with human HGPRT and TBrHGPRT1 have been obtained, providing structural insights into the reasons for the range of values of the inhibition constants not only between the compounds themselves but also between the enzymes from these organisms.

Results and Discussion

The Prolinols

The chemical structures of the five prolinols are given in Figure 5. These compounds all have guanine as the purine base and the chemical attachments to the carbon or nitrogen atom of the prolinol ring are identical. The differences between these molecules depend on whether the prolinol group exists as the l- or d-enantiomer and/or whether the prolinol is attached to the N9 atom of the purine ring as the (S) or (R) isomer (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 5.

Chemical structure of the five prolinol compounds (1–5). The numerals show the number of atoms between the N9 of the purine ring and the phosphorus atom. There are seven atoms between the phosphorus atom at the termini of the linker, which is attached to the carbon atom of the five-membered ring (red numerals) and six between the phosphorus atom at the termini of the linker attached to the nitrogen atom of the five-membered ring (blue numerals).

Synthesis

The newly designed compounds were prepared, as outlined in Scheme 1. Michael addition of diethyl vinylphosphonate to protected pyrrolidine 6a (or enantiomeric 6b) afforded phosphonate 7a (7b). In the next step, a guanine nucleobase was introduced by Mitsunobu reaction with 6-chloro-2-aminopurine and subsequent acidic hydrolysis yielded 8a (8b). A second phosphonate function was added by reaction with diisopropyl 3-phosphonopropionic acid catalyzed by EDC. The phosphonate esters were removed by treatment with TMSBr resulting in the two bisphosphonates, 3 and 4. Inversion of configuration of pyrrolidine carbon atom 4 of 7a (7b) via Mitsunobu esterification with 4-nitrobenzoic acid followed by methanolic ammonia ammonolysis afforded phosphonate 9a (9b). In the next step, the guanine nucleobase was introduced by Mitsunobu reaction with 6-chloro-2-aminopurine and subsequent acidic hydrolysis, yielding 10a (10b). Reaction with diisopropyl 3-phosphonopropionic acid catalyzed by EDC and TMSBr promoted phosphonate ester groups removal to give the final compounds, 2 and 5. Compound 1 was prepared from the protected hydroxyprolinol 11. Mitsunobu esterification with 4-nitrobenzoic acid followed by methanolic ammonia ammonolysis afforded 12, which then underwent Mitsunobu nucleosidation. The nucleoside, 13, was reacted with diisopropyl 3-phosphonopropionic acid catalyzed by EDC, and subsequent TMSBr promoted phosphonate ester group removal to produce 1.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Prolinol Phosphonate and Bisphosphonates, 1–5 (see Figure 5).

Inhibition Activity

Table 1 compares the Michaelis–Menten constants for the two substrates (PRPP and guanine), the Ki values for GMP (a nucleoside monophosphate product of the catalytic reaction) with the Ki values for the prolinol-containing inhibitors.

Table 1. Comparison of the Kinetic Constants of Seven H/G/X/PRTs for Their Naturally Occurring Substrates/Products with Those of the Five Prolinol Containing Inhibitors.

| enzyme | PRPPKm(μΜ) (PRPP) | base (G)Km(μΜ) Guanine | GMPKi(μΜ) GMP | 1Ki(μΜ) l-prolinol(R) isomer | 2Ki(μΜ) d-prolinol(S) isomer | 3Ki(μΜ) d-prolinol(R) isomer | 4Ki(μΜ) l-prolinol(S) isomer | 5Ki(μΜ) l-prolinol(R) isomer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammalian | ||||||||

| human HGPRT | 65 ± 538 | 1.9 ± 0.438 | 5.8 ± 0.239 | 0.09 ± 0.2 | 0.14 ± 0.3 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.003 ± 0.005 |

| Parasites | ||||||||

| Pf HGXPRT | 69 ± 438 | 0.83 ± 0.538 | 10 ± 140 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | >10 | 2 ± 0.5 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.01 ± 0.005 |

| Pv HGPRT | 73 ± 341 | 1.9 ± 0.441 | 26.1 ± 241 | 2.7 ± 1 | >10 | 1 ± 0.5 | 0.02 ± 0.005 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| TBr HGPRT1 | 31 ± 342 | 2.3 ± 0.442 | 30.5 ± 0.242 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | >10 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.003 ± 0.0006 |

| Mycobacteria and Bacteria | ||||||||

| Mtb HGPRT | 465 ± 1543 | 4.4 ± 0.433 | 20 ± 343 | 6 ± 2 | >10 | 2 ± 1 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| Hp XGHPRT | 27 ± 434 | 3.1 ± 0.234 | 23 ± 434 | 1 ± 0.2 | >10 | 0.1 ± 0.04 | 7 ± 2 | 0.1 ± 0.03 |

| Ec XGPRT | 64 ± 344 | 4.3 ± 0.345 | 4.5 ± 0.344 | 4 ± 2 | >10 | 1 ± 0.4 | 9 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 |

The Km values for the two substrates, PRPP and guanine, and for one of the products of the reaction, GMP, are similar for the human, protozoan parasite, bacterial, and mycobacterial enzymes (Table 1). The exception is the Km for PRPP for MtbHGPRT, which is significantly higher than those for the other six enzymes cf. 465 μM with 27–73 μM. The Km for guanine for all these enzymes ranges between 0.8 and 4.4 μM (5-fold) and, for GMP, the Ki values lie between 4.5 to 30.5 μM (6.8-fold) (Table 1). The spread of Ki values for the prolinols presented here is much wider than the Km values for the substrates and Ki values for the products (Table 1). For 1, the range of inhibition constants between the seven enzymes is 200-fold, for 3, the range is 33-fold, for 4, it is 900-fold, and for 5, it is around 1300-fold. One hypothesis to explain this data is that there are differences in the binding modes to the human, protozoan parasitic, bacterial, and mycobacterial enzymes which result in nonidentical interactions with active site side chain and main chain atoms. 2 is a very weak inhibitor of the enzymes from the pathogens having Ki values greater than 10 μM. It is a reasonable inhibitor of human HGPRT, though, demonstrating active site differences between the human enzyme and the enzymes from both the parasites and bacteria. These differences should be able to be exploited for selective drug design. Surprisingly, all the new compounds are comparatively weak inhibitors of EcXGPRT, with the best, 3, having a Ki of 1 μM. For human HGPRT, Pf HGXPRT and PvHGPRT, the inhibitors with the lowest Ki values are 4 and 3 while, for TBrHGPRT1, 1, 4, and 5 have low Ki values (3–30 nM). 5 has the lowest Ki value for MtbHGPRT, and 3 and 5 are the best inhibitors of HpXGHPRT. In general, therefore, 5 is the most effective broad-spectrum inhibitor though the degree of inhibition varies with Ki values between 3 and 300 nM for six of the enzymes and a Ki for EcXGPRT of 4 μM (Table 1).

Overall, the compounds with an l-prolinol in the linker are better inhibitors of these seven enzymes than those containing a d-prolinol group cf. 2 with 4 [(S) isomers] and 3 with 5 [(R) isomers]. There are only two exceptions to the preference for the l-prolinols. This is for the two bacterial enzymes, HpXGHPRT and EcXGPRT (Table 1). HpXGHPRT has the same Ki values for 3 and 5 (0.1 μM) while, for EcXGPRT, the Ki value is lower for 3 compared with 5 (1 μM cf 4 μM). 2 and 3 are d-prolinols and differ only in the isomeric attachment of prolinol group to the purine ring, (S) and (R), respectively. 4 and 5 are l-prolinols and also differ from each other only in the isomer that is attached.

The attachment of the prolinol group to the purine ring for both the l- and d-prolinols resulted in lower Ki values when this is as the (R)-isomer compared with the (S)-isomers (cf. 2 with 3 and 4 with 5). Indeed, for the d-prolinols as the (S)-isomer (2), the compounds bind very weakly to the protozoan parasite and bacterial enzymes (Ki > 10 μM), although this compound is a reasonable inhibitor of human HGPRT (Ki = 0.14 μM). The Ki ratio between these two isomers for the d-prolinols varies between 7 for the enzyme from Mt to 10 for the human and Pf enzymes to 17 for PvHGPRT and 66 for TBrHGPRT1. Thus, for the d-prolinols, the biggest effect of the changes in the isomers is for TBrHGPRT1.

1 is a l-prolinol with the five-membered ring attached to the purine base as the (R)-isomer. The effect of a second phosphonate group added to the five-membered ring can be determined by comparing inhibition constants for 1 and 5 (Figure 5 and Table 1). The absence of this second phosphonate group resulted in an increase in the Ki values. The scale of this increase depends on the species of the H/G/XPRT. For example, the greatest increase occurs between the human and the two Plasmodium enzymes (30–45-fold; cf1 with 5). The increase in Ki values for the enzymes from TBr, Mtb, and Hp was less significant being of the order of 10–20-fold, while the Ki values for EcXGPRT were the same (4 μM). The crystal structures of human HGPRT in complex with either 1 or 5 were determined to assess the reason for this effect. In general, the best inhibitors of these prolinol containing compounds are the l-prolinols with this five-membered ring attached to the N9 atom of the purine ring as the (R)-isomer (i.e., 5).

The effect of one or two phosphonate groups was deducted by comparing the structures of human HGPRT in complex with 1 or 5. Crystal structures of 5 in complex with human HGPRT or TBrHGPRT1 investigated any possible differences in the binding modes between the human enzyme and the enzyme from one of the parasites. The effect of the isomeric attachment at the N9 atom of the purine ring was examined by obtaining the crystal structures of two complexes, TBrHGPRT·4 and TBrHGPRT1·5.

The Crystal Structures of Human HGPRT in Complex with Compounds 1 or 5 and TBrHGPRT1 in Complex with Compounds 4 and 5

The X-ray data collection and refinement statistics of the four complexes are presented in Table 2. The two human HGPRT structures refine as a tetramer in the asymmetric unit. The TBrHGPRT1·4 complex refines as a dimer, while the TBrHGPRT1·5 complex refines as two dimers.

Table 2. X-ray Collection and Refinement Statistics for the Four Enzyme Inhibitor Complexes.

| humanHGPRT·1 | TBrHGPRT1·4 | humanHGPRT·5 | TBrHGPRT1·5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal parameters | ||||

| wavelength | 0.95373 | 0.95373 | 0.95373 | 0.95373 |

| space group | P 21 21 21 | P 42 21 2 | P 21 | P 21 |

| unit cell length, a, b, c(Å) | 74.46, 93.42, 129.32 | 93.03, 93.03, 105.70 | 55.64, 129.59, 64.33 | 56.86, 88.28, 94.31 |

| unit cell angle, α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 103.80, 90 | 90, 106.05, 90 |

| Diffraction data | ||||

| temperature (K) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| resolution rangea (Å) | 75.73–2.50 (2.59–2.50) | 41.2–2.20 (2.25–2.20) | 43.98–2.27 (2.41–2.27) | 45.97–2.46 (2.55–2.46) |

| total reflections | 73,412 (6943) | 84,604 (5885) | 129,885 (7590) | 93,048 (7589) |

| unique reflections | 31,919 (3156) | 24,294 (1690) | 43295 (2811) | 37,219 (3162) |

| multiplicity | 2.3 (2.2) | 3.5 (2.5) | 3.0 (2.7) | 2.5 (2.4) |

| completeness (%) | 99.90 (99.97) | 99.96 (100) | 98.97 (96.3) | 97.22 (95.02) |

| mean I/σ(I) | 7.32 (2.16) | 19.31 (3.75) | 9.41 (1.52) | 6.57 (3.34) |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 37.40 | 27.77 | 28.01 | 27.49 |

| R-pim | 0.0448 (0.396) | 0.019 (0.111) | 0.040 (0.437) | 0.091 (0.254) |

| CC1/2 | 0.997 (0.777) | 0.998 (0.97) | 0.997 (0.525) | 0.989 (0.851) |

| Refinement | ||||

| reflections used in refinement | 31887 (3146) | 24173 (1670) | 42442 (2791) | 31799 (2550) |

| Rwork | 0.200 (0.244) | 0.163 (0.190) | 0.358 (0.387) | 0.229 (0.313) |

| Rfree | 0.260 (0.339) | 0.217 (0.253) | 0.223 (0.289) | 0.287 (0.367) |

| RMS (bonds Å) | 0.006 | 0.012 | 0.004 | 0.006 |

| RMS (°) | 1.05 | 1.17 | 1.04 | 0.87 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 94.61 | 94.44 | 97.41 | 93.18 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.66 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.29 |

| clashscoreb | 11.3 | 5.30 | 6.56 | 8.92 |

| Components of the asymmetric unit | ||||

| subunits | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| inhibitors | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| magnesium ions | 3 | 2 | 8 | 0 |

| water molecules | 111 | 280 | 170 | 375 |

The values in parentheses are for the outer resolution shell.

A clash is defined as an atomic overlap of 0.4 A (Angstroms). The clash score is (1000x number of overlaps)/number of atoms in the structure.

Figure 6 shows the electron density maps of the three inhibitors bound in the active site of human HGPRT or TBrHGPRT1. These structures clearly show the binding modes of the ligands to human HGPRT and TBrHGPRT1. They emphasize the movements that occur as the ligands adjust to obtain an optimal fit in active site of the HGPRTs from the two different species.

Figure 6.

Connolly surface of human HGPRT and TBrHGPRT1 active sites with the electrostatic surface and Fo–Fc omit electron density maps for 1, 4, or 5 overlaid. The maps are contoured at the 3.0 sigma level. (A) Human HGPRT·5 complex. (B) Human HGPRT·1 complex. (C) TBrHGPRT1·4 complex. (D) TBrHGPRT1·5 complex.

Comparison of the Binding Mode of 1 and 5 in the Active Site of Human HGPRT

Figure 7 shows how compounds with one (1) or two (5) phosphonate groups bind in the active site of human HGPRT. Both contain a l-prolinol group in the linker, and this group is attached to the N9 atom of the purine ring as the R-isomer. Despite these commonalities, there are several differences in the binding modes of these two ligands (Figures 6A,B and 7). These include the purine base, the phosphonate group, and the carbonyl group (Figure 7B). In the human HGPRT·5 complex, the purine ring forms a well-aligned π-stacking arrangement with the aromatic ring of F186 (Figure 7A). On the other hand, when 1 binds, the purine ring is tilted forward, away from the back of the active site and toward surrounding solvent (Figure 7A,B). Thus, the purine base is not anchored as effectively for 1 compared to 5. This orientation of the purine ring is attributed to the contribution the second phosphonate group makes in placing the base in position.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the binding modes of 1 (silver) and 5 (green) in the active site of human HGPRT. (A) A side view of the binding of the purine ring of both compounds with F186. (B) Connolly surface of human HGPRT with 1 and 5 in their positions in the active site cavity. (C) The relative positions of 1 and 5 in the active site. The arrows highlight the differences in mode of binding of the functional groups: purple, purine base; cyan, phosphonate group; pink–carbonyl group; dark blue–nitrogen atom in the prolinol ring.

Another difference between these complexes is the positioning of phosphonate group in the 5′-phosphate binding pocket. For 5, there are seven atoms in the linker between the phosphorus atom and N9 of the purine base but only six for 1 (Figure 5). In GMP, there are five atoms between N9 and the phosphorus atom. When 5 binds, it is the longer linker attached to the carbon atom of the prolinol group that positions the phosphonate group in this pocket while, in 1, this site is occupied by the phosphonate group attached to the shorter linker, which comes off the prolinol nitrogen atom. On face value, it appears surprising that the human enzyme has been able to place the phosphonate group attached to the longer linker in this pocket as it was thought that there would be insufficient room in this cavity to accommodate it. However, the active sites of HG(X)PRTs, including human HGPRT, are known to be flexible.46,47 Since the electron density map (Figure 6A) clearly positions this phosphonate group in the 5′-phosphate binding pocket, this must mean either that the shape of the linker has to change to fit or there has to be a change in the structure of the enzyme itself. Figure 8 shows that it is the latter that occurs. The phosphonate group of 5 does push further into this pocket than the phosphonate group of 1 or GMP (Figure 8A), forcing the flexible loop (D137-T141) to move away (Figure 8B). The distance between the phosphorus atoms in 1 and 5 is 1.3 Å (Figure 8A), which is approximately the same distance that the loop moves. The movement of this loop triggers a further structural change, and this is between residues P168–V171 (Figure 8B). This loop also moves outward by approximately 1.7 Å. Figure 8B also demonstrates that residues 137–141 are adaptable, depending on the number of atoms connecting the phosphorus atom to the purine ring in the ligand. This movement in the structural complex is in the order GMP < 1 < 5 (Figure 7B). The structure of these two loops when 1 binds is a closer mimic of that when GMP binds.

Figure 8.

5′-Phosphate binding site in human HGPRT when three different ligands bind. (A) The position of the phosphate/phosphonate group in the human HGPRT, GMP, 1, and 5 complexes. GMP is blue, 1 is silver, and 5 is green. (B) The position of the two flexible loops surrounding this binding site (residues 137–141 and residues 168–171). GMP is blue, 1 is silver, and 5 is green.

It has previously been established based on crystal structures of human HGPRT with ImmGP47 and Pf HGXPRT in complex with ImmHP,47 and the acyclic immucillin phosphonate (AIP) inhibitor,48 that the side chain of the invariant aspartic acid, D137 (Figure 8), moves by at least 1 Å during catalysis, putting a carboxylate oxygen atom within 2.8 Å of the N7 atom of the purine base. In addition to these changes, a large flexible loop (R100 to T128, human HGPRT numbering)) also interacts with these transition-state analogues, resulting in sequestration of the active site from the solvent. However, when the prolinol inhibitors bind, neither does the large mobile loop cover the active site nor does a hydrogen bond form with the N7 atom of the purine base. In human HGPRT, the distance range is between 3.5 and 4.3 Å while, for TBrHGPRT1, it varies from 3.7 to 4.3 Å. For human HGPRT, the Ki values for the prolinol inhibitors are 90 nM (1), 9 nM (4), and 3 nM (5), and for the transition-state analogues identified above the Ki values range from 0.65 to 385 nM for PfHGXPRT and human HGPRT.48 Thus, the prolinol-containing inhibitors are powerful inhibitors despite the fact that the enzyme structure has not folded as if it were progressing toward the transition state, as is the case for ImmG, ImmHP, and AIP.

The hydroxyl group in 1 (Figure 5) is not placed in the same position as either of the two hydroxyls of the ribose ring of GMP. The hydroxyl group, indeed, does not form any interactions in the active site and appears to make no contribution to the Ki value. It is possible, however, that it may help in shaping the 3D structure of the linker.

Compound 5 has two “wings” coming off the prolinol group, each of which has a phosphonate group at its termini. One of the factors that contributes to its low Ki value is the interactions that each of these phosphonyl oxygens make with side chain or main chain atoms in the active site.

Comparison of the Binding Modes of 5 to Human HGPRT and TBrHGPRT1

5 is a nanomolar inhibitor of both human HGPRT and TBrHGPRT1 (Ki = 3 nM). Thus, one prediction that could be made is that 5 would bind in a similar manner in each instance. However, this is not the case. In both these structures, the purine ring forms a parallel π-stacking arrangement with the aromatic side chain of the conserved aromatic amino acid, F158 in human HGPRT and F166 in TBrHGPRT1 (Figure 9A). However, the location of each of the two phosphonate groups in these enzymes is reversed (Figure 9B). In human HGPRT, it is the phosphonate group attached to the carbon atom of the prolinol ring that enters the 5′-phosphate binding pocket whereas, when 5 is bound to TBrHGPRT1, it is the group that is attached to the nitrogen atom (Figure 9B). A major driving force for binding of 5 could be the location of the carbonyl group in the shorter linker. In the human HGPRT·5 complex, its position allows for coordination to a magnesium ion (Figure 10A). Perhaps, these interactions are not possible in the structure of TBrHGPRT1 and, hence, the change in orientation of the inhibitor. It is hypothesized that the loop surrounding this 5′-phosphate binding site is less flexible in TBr than the counterpart in the human enzyme (Figure 8B). Therefore, this loop is unable to move out to accommodate the longer linker and, as a result, the two phosphonate groups occupy alternate binding pockets in the human and Tbr enzymes. However, with this swap, the phosphorus atom in the pyrophosphate binding site is in the same location in both structures (Figure 10B).

Figure 9.

Comparison of the binding modes of 5 in the active site of human HGPRT (green) and TBrHGPRT1 (yellow). (A) The π-stacking arrangement of the purine ring. (B) The different conformations of the ligand. Human HGPRT (green) and TBrHGPRT1 (yellow). Arrows show the functional groups: pink, phosphonate group; dark blue, nitrogen in the prolinol ring; purple, carbonyl group; green, second phosphonate group.

Figure 10.

Binding site of the phosphonate group on the linker attached to the nitrogen in the prolinol ring in the structure of the human HGPRT·5 complex. (A) Coordination of the phosphonyl oxygen and the carbonyl oxygen to a magnesium ion. Yellow dashed lines are the distances to a magnesium ion (green sphere). The blue spheres are water molecules, and the magenta dashes indicate hydrogen bonds. (B) Superimposition of the human HGPRT·5 complex within the human. ImmGP.PPi complex (PDB code: 1BZY). Yellow is the pyrophosphate in the transition-state complex.

The phosphonate groups that point down to the bottom of the active site of each enzyme superimpose on each other perfectly (Figure 9B; green arrow). Despite this, the phosphonyl oxygens form completely different interactions in the active site (cf. Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 11.

Interactions that the phosphonate group (attached to the nitrogen of the prolinol ring) of 5 makes when bound in the active site of TBrHGPRT1. The blue sphere is a water molecule.

In the human HGPRT·5 complex, the phosphonyl and carbonyl oxygens are coordinated to a magnesium ion and this sets up a network of bonds which firmly anchors this inhibitor in place (Figure 10A). Superimposition of this complex onto that of the human enzyme in complex with the transition-state analogue, (1S)-1-(9-deazaguanyl-9-yl)-1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-d-ribitol 5-phosphate (ImmGP) together with pyrophosphate, shows that the phosphorus atom, the phosphonyl oxygens, and the carbonyl oxygen atoms of the inhibitor are located in a similar position as pyrophosphate (Figure 10B). These interactions may be one of the most important features of this ligand that contribute to the nanomolar Ki values for human HGPRT (3 nM; Table 1).

The carbonyl group in the TBrHGPRT1·5 complex does not form any interactions with active site residues. However, 5 is still an excellent inhibitor of TBrHGPRT1with a Ki value of 3 nM. Therefore, it is not always the case that only identical binding modes produce the same inhibition constants. Many different factors can be the driving force for inhibitors with high affinity.

There are no magnesium ions in the TBrHGPRT1·5 complex, and, as such, divalent metal ions do not play any role in anchoring this molecule in the active site. This is the opposite to the human HGPRT·5 complex, which contains two magnesium ions (Table 2). In the case of the TBr enzyme, the phosphonate group is held in position by only three hydrogen bonds (Figure 11).

However, these bonds, together with the other interactions in the active site, are sufficient to result in a high affinity of the compound for the enzyme.

Comparison of the Binding Modes of 4 and 5 in the Active Site of TBrHGPRT1

Figure 12 compares the 3D structure of 4 with 5 when they are bound in the active site of TBrHGPRT1. There is only one difference in the chemical structure of these two ligands, and this is the isomeric attachment of the prolinol ring to the N9 atom of the purine ring (Figure 5). The (R) isomer does once again have the highest affinity (cf. Ki value of 3 nM with 70 nM) (Table 1).

Figure 12.

Comparison of the binding modes of 4 (blue) and 5 (yellow) in the active site of TBrHGPRT1. (A) The purine ring. (B) Connolly surface of the enzyme with the two ligands in the active site. The arrows show the location of three of the functional groups engineered into the scaffold.

Both purine rings form a π-stacking arrangement with the aromatic side chain of F166, and both phosphonate groups located in the 5′-phosphate binding pocket form identical interactions with active site side chain and main chain atoms (Figure 12A,B). As found for 5, the carbonyl oxygen of 4 does not make any interactions in the active site. The difference in their binding, therefore, lies in the positioning of the phosphonate group attached to the nitrogen atom in the prolinol ring (Figure 12A). The interactions of the phosphonyl oxygens in the TBrHGPRT1·5 complex are given in Figure 11 and those of 4 in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Interactions of the phosphonyl oxygens of the phosphonate group at the termini of the linker attached to the carbon atom of the prolinol ring in theTBrHGPRT1·4 complex. The green sphere is a magnesium ion and blue spheres are water molecules.

The large electron density found around the phosphonate group attached to the carbon atom in the prolinol ring when 4 binds has been assigned to a magnesium ion (Figure 13). The distances between the metal ion and water and the phosphonyl oxygen agree with the ligation chemistry. Thus, when this compound binds, a magnesium ion is found in an unpredicted locality and assists in binding this ligand.

Other Interactions that Can Determine How Tightly the Ligands Bind to the Enzymes

Although the presence of magnesium ions is essential for catalysis to proceed in the H/G/X/PRTs, it does not play a direct role in catalysis. Rather, it assists in binding one of the two substrates (PRPP) and one of the two products of the reaction, i.e., PPi. It could be anticipated, therefore, that this ion could also play a role in helping the inhibitors to bind. One of the obvious ways this could be achieved is through coordination to the phosphonyl oxygens (Figures 10 and 13). Another possibility is through the OE1 and OD1 atoms of the two invariant acidic amino acid residues, glutamic and aspartic acid (133 and 134 in human HGPRT and 113 and 114 in TBrHGPRT1).

When ImmGP, PPi, and magnesium ion are bound in the active site of human HGPRT, the OE1 and OD1 atoms of the two acidic side chains are 2.7 Å apart (Figure 14A). In the transition-state complex, these oxygen atoms are not coordinated to a magnesium ion. Rather, they make hydrogen bonds to the hydroxyl groups of the ribose ring. To release the products of the reaction, the large mobile loop opens, the side chains move apart, and the distance between the OE1 and OD1 atoms becomes 4.2 Å (Figure 14A). This allows the release of the two products of the reaction, first pyrophosphate and the associated magnesium ion followed by the nucleotide, as has been proposed previously.49−51 When 1 and 5 bind to human HGPRT, the two side chains are 2.8 Å apart but, in this scenario, they coordinated directly to a magnesium ion (Figure 15B).

Figure 14.

Movement of the side chains of E133 and D134 when four different ligands bind in the active site of human HGPRT. The green sphere is magnesium. (A) Blue is the human. GMP complex (PDB code: 1HMP). Red is when the transition-state analogue, (1S)-1-(9-deazaguanin-9-yl)-1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-d-ribitol 5-phosphate (ImmGP),27 is bound (PDB code: 1BZY). (B) Silver is when 1 and green is when 5 is bound in the active site.

Figure 15.

Assisted binding of 1 (A) and 5 (B) to human HGPRT via a divalent metal ion. Water molecules are shown as blue spheres and the divalent metal ion as green spheres. In (A), the coordination bonds are shown as green or red dashes and a hydrogen bond as yellow dashes. In (B), the coordination bond distances are shown as magenta dashes and hydrogen bonds as yellow dashes.

Thus, the two side chains of D133 and E134 are in the “closed” position, mimicking when ImmGP and pyrophosphate are bound. However, in the case of the inhibitors, a metal ion is in the vicinity (Figure 15B) and this allows a network of interactions to be established. In both cases, the tightness of binding is assisted via hydrogen bonds between water molecules and the inhibitor itself and via coordination to a divalent metal, which is then coordinated to the two invariant acidic amino acids, D134 and E133 (Figure 15A,B).

In contrast, when 4 and 5 bind in the active site of TBrHGPRT1, the OD1 atoms of E113 and D114 are far apart (Figure 16) and there are no divalent metal ions in the vicinity. However, they can directly assist in binding the two ligands through several hydrogen bonds either directly to the phosphonyl oxygens or via a water molecule (Figure 16). Thus, although the precise interactions of the network differ, the OE1 and OD1 atoms of the invariant two acidic residues (ED) form bonds to the phosphonyl oxygens of the two phosphonate groups in both complexes and assist in anchoring these two inhibitors in the active site.

Figure 16.

Position of E113 and D114 when 4 (blue; A) and 5 (yellow; B) bind in the active site of TBrHGPRT1.

Prodrugs of the Most Potent Inhibitors and Their Biological Activity

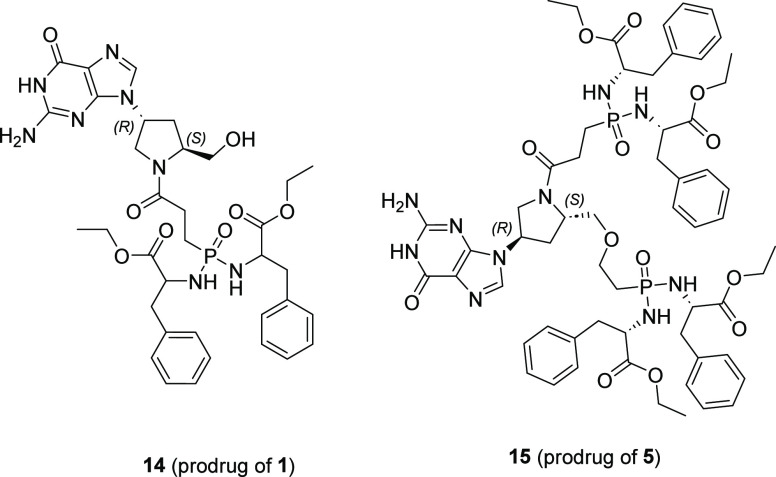

The prolinol inhibitors described here carry negative charges, making them unsuitable for biological testing against human pathogens. To begin to address this problem, phenylalanine amidate prodrugs 14 and 15 of inhibitors 1 and 5, respectively (Figure 17), were prepared according to procedures described previously.33

Figure 17.

Structure of prodrugs 14 and 15.

14 and 15 were tested for their antitrypanosomal activities against Trypanosoma brucei brucei and showed EC50 values of 9.98 ± 1.15 and 19.84 ± 0.27 μM, respectively. This result shows that in principle, if the prolinols can be delivered to the target pathogen, they can be effective in preventing the growth or killing a pathogen in culture.

The parent compounds, 1 and 5, are both potent inhibitors of TBrHGPRT1 with Ki values of 30 and 3 nM, respectively, with the primary difference being that, while 1 possesses only one phosphonate group, 5 has two. Thus, prodrug 14 is significantly smaller (735.78 Da) than 15 (1195.26 Da). The lower EC50 value for prodrug 14 compared to 15 is thus likely due to 14 having a lower overall molecular weight, facilitating transport across the cell membrane. In addition, it has only one masking group to be removed, which may also contribute to its lower EC50 value. The studies suggest that both potent inhibition of the TBrHGPRT1 enzyme and effective prodrug design are needed. To date, prodrug design has focused on improving the bioavailability of drugs containing a phosphonate group against viral infections.52 More work is needed to improve potency for the bacterial and mycobacterial enzymes and for the delivery of compounds into more challenging environments such as Plasmodium falciparum within red blood cells and Mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages.

Conclusions

The insertion of a prolinol group in the linker(s) connecting a purine base to one or two phosphonate groups allows for versatility in inhibitor design. The prolinol structure allows functional groups to be attached to this ring such that new modes of binding of H/G/X/PRT inhibitors can be explored. These newly designed compounds exhibit a wide range of Ki values for the human, parasitic, bacterial, and mycobacterial H/G/X/PRTs and, thus, can discriminate between enzymes in this class. For the human enzyme, the l-prolinol and (R)-isomer configuration is the preferred configuration (i.e., 5). Key to this preference is the parallel π stacking of the purine base with the conserved aromatic amino acid in the enzyme (i.e., F186 in human HGPRT) (Figure 7) and the fact that the 5′-phosphate pocket can expand to bind the 5′-phosphonate of 5. Such an expansion does not occur when GMP or 1 binds (Figure 8). The linker attached to the nitrogen of the prolinol also plays a critical role in affinity, with interactions to R199 and D193. In the latter, this is assisted by the presence of a Mg2+ and several water molecules (Figure 10A). The tail of the linker finds itself in a location that strongly mimics the location where pyrophosphate binds in the human ImmGP.PPi complex (Figure 10B). The prolinol ring does not make many interactions with the enzyme but plays an essential role in that it positions the purine ring, the 5′-phosphate, and the linker in positions that allow strong interactions in all three sites. The Ki values for the parasitic enzymes follow a similar trend to the human enzyme, with 5 being the most potent followed by 4. The Ki values of 5 for human and TbrHGPRT1 are virtually identical at 3 nM. This might suggest identical modes of binding in the two enzymes, but this is not the case. The prolinol ring in TbrHGPRT1 is rotated by ∼90° compared to its binding to the human counterpart (Figure 6). Nonetheless, the purine ring, the 5′-phosphate, and the linker all make highly favorable interactions with TbrHGPRT1, although these are different to human HGPRT (Figures 6 and 9). The binding of all compounds in the series is substantially weaker to the bacterial and mycobacterial enzymes. Additional crystal structures will be needed to explain why this is the case. The X-ray crystal structures reveal that these inhibitors interact with the enzyme by a mechanism of “induced fit”. 5 is one of the most potent of these inhibitors, especially for the parasitic enzymes and, as such, is an excellent scaffold for further development as antiparasitic drug leads.

The Ki values of 1 for human HGPRT and TbrHGPRT1 are 90 and 30 nM, respectively. For 5, as mentioned above, both compounds have Ki values of 3 nM. Thus, neither compound has a strong selectivity for the parasite enzyme over the human counterpart. However, previous studies on phosphonate prodrugs that inhibit HGPRT have shown that they have low toxicity in human cell lines, with CC50 values usually >300 μM.53,54 This is proposed to be because humans possess both salvage and de novo pathways for the synthesis of nucleoside monophosphates. Thus, while it appears to be an advantage for an inhibitor to have selectivity for the parasite enzyme over the human enzyme in antiparasitic drug development, it may not be an absolute requirement.

In addition, nucleotide metabolism has long been recognized to provide multiple pathways for the development of new anticancer treatments.55 Recently, it has emerged that HGPRT is upregulated in malignant tumors and localized to the surface in some cancer cells,56 this likely due to the increased rate of DNA production compared to normally replicating human cells. Thus, human HGPRT inhibitors such as the prolinols synthesized here also have potential as anticancer therapeutic agents.

Experimental Section

Synthesis

General Conditions and Used Materials

Unless stated otherwise, all solvents were anhydrous. TLC was performed on silica gel-precoated aluminum plates TLC Silica gel 60 F254 (Supelco), and compounds were detected by UV light (254 nm), by heating (detection of the dimethoxytrityl group, orange color), by spraying with 1% solution of ninhydrine to visualize amines, and by spraying with 1% solution of 4-(4-nitrobenzyl)pyridine in ethanol followed by heating and treating with gaseous ammonia (blue color of mono- and diesters of phosphonic acid). Preparative column chromatography was carried out on silica gel (40–63 μm, Fluorochem), and elution was performed at the flow rate of 60–80 mL/min. The following solvent systems were used for TLC and preparative chromatography:toluene-ethyl acetate 1:1 (T), chloroform–ethanol 9:1 (C1), ethyl acetate–acetone–ethanol–water 6:1:1:0.5 (H3), and ethyl acetate–acetone–ethanol–water 4:1:1:1 (H1). The concentrations of solvents are stated in volume percent (%, v/v). The purity of intermediates was determined by LC-MS performed on Waters AutoPurification System with 2545 Quaternary Gradient Module and 3100 Single Quadrupole Mass Detector using a Luna C18 column (Phenomenex, 100 × 4.6 mm, 3 μm) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The usual conditions are as follows: mobile phase, A—50 mM NH4HCO3, B—50 mm NH4HCO3 in 50% aq. CH3CN, C—CH3CN, A → B/10 min, B → C/10 min, C/5 min. Preparative RP HPLC was performed on LC5000 Liquid Chromatograph (INGOS-PIKRON, CR) using the Luna C18 (2) column (250 × 21.2 mm, 5 μm) at a flow rate of 10 mL/min by a gradient of methanol in 0.1 M TEAB pH 7.5 (A = 0.1 M TEAB, B = 0.1 M TEAB in 50% aq. methanol, C = methanol) or without buffer (TEAB). All final compounds were lyophilized from water. The purity of the final compounds was greater than 95%. Purity of final compounds was determined via LC-MS analysis using ACQUITY UPLC coupled with Xevo G2-XS QTof (Waters) using a ZIC cHHILIC column (Sigma-Aldrich; 100 × 2.1 mm, 3 μm) with gradient elution: 70% B 0–2 min, 100% A in 9 min, hold until 10.5 min. A = 50% acetonitrile with 10 mM ammonium acetate; B = acetonitrile; flow = 0.3 mL/min. Detection was performed using full scan mode in ESI+ (or ESI−) mode of ionization. Mass spectra were recorded on LTQ Orbitrap XL (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using ESI ionization. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700 spectrometer. Absorption maxima (νmax) are reported in wavenumbers (cm–1). Specific rotation values were determined with an Autopol IV (Rudolph Research Analytical, USA, 2001) polarimeter. Specific rotation values [α]D were measured in H2O (concentration units: g/100 mL). NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker AVANCE III HD 400 MHz (1H at 400.1 MHz, 13C at 100.6 MHz, and 31P at 162.0 MHz), Bruker AVANCE III HD 400 MHz Prodigy (1H at 401.0 MHz, 13C at 100.8 MHz, and 31P at 162.0 MHz), Bruker AVANCE III HD 500 MHz (1H at 500.0 MHz, 13C at 125.7 MHz, and 31P at 202.4 MHz), and JEOL JNM-ECZR 500 MHz (1H at 500.2 MHz, 13C at 125.8 MHz, and 31P at 202.5 MHz) spectrometers. D2O (reference (dioxane) = 1H 3.75 ppm, 13C 69.3 ppm). Chemical shifts (in ppm, δ scale) were referenced to TMS as internal standard, and coupling constants (J) are given in Hz. All intermediates were determined by LC-MS.

General Method A: Reaction with Diethyl Vinylphosphonate and Subsequent Removal of the DMTr-Protecting Group

A mixture of hydroxy derivative (1 mmol), diethyl vinylphosphonate (1.5 mmol), and Cs2CO3 (1 mmol) in t-BuOH (2.5 mL/mmol) was stirred under an argon atmosphere at 50 °C for 2 days. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, and the product was obtained by column chromatography on silica gel using a linear gradient of EtOH in chloroform. This led to a partially pure product, but it was used for the next step (DMTr PG removal) without further purification and characterization. The product was dissolved in 2% TFA in CHCl3 (10 mL/mmol) and stirred for 10 min. Solid NaHCO3 (1 g/mmol) was added and the suspension stirred until the pH was neutral. The suspension was filtered and the filtrate dried in vacuo. The desired product was obtained by column chromatography on silica gel using a linear gradient of EtOH in chloroform.

General Method B: Inversion of Configuration

The mixture of the hydroxy derivative (1 mmol), triphenylphosphine (2.5 mmol), lutidine (1.5 mmol), and 4-nitrobenzoic acid (1.3 mmol) was coevaporated with THF (2 × 10 mL) and dissolved in the same solvent (10 mL/mmol). DIAD (2.5 mmol) was added under an argon atmosphere, and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT overnight. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, and 4-nitrobenzoic acid ester with inverted configuration was obtained by column chromatography on silica gel using a linear gradient of ethanol in chloroform. The product was dissolved in methanol and the solution saturated with gaseous ammonia at 0 °C. The mixture was left at RT overnight and concentrated in vacuo. The desired hydroxy derivative with inverted configuration was obtained by column chromatography on silica gel using a linear gradient of ethanol in chloroform.

General Method C: Mitsunobu Nucleosidation

DIAD (3.5 mmol) was added to the solution of diphenylpyridylphosphine or triphenylphosphine (3.5 mmol) in THF (5 mL/mmol), and the mixture was stirred at RT under an argon atmosphere for 30 min. The mixture was then added to the mixture of hydroxy derivative (1 mmol) and 2-amino-6-chloropurine (1.5 mmol) (coevaporated prior to the reaction with THF (2 × 10 mL) in THF (5 mL/mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred under an argon atmosphere at RT overnight. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, and the chloropurine product was obtained by column chromatography on silica gel using a linear gradient of ethanol in chloroform.

General Method D: Boc Group Removal and Nucleobase Hydrolysis

Protected chloropurine derivative (1 mmol) was stirred with EtOH (10 mL/mmol) and 3 M aq. HCl (10 mL/mmol) at 80 °C overnight. The reaction mixture was diluted with water:EtOH 1:1 (20 mL/mmol) and applied to a column of Dowex 50 in H+ form (20 mL/mmol). The resin was washed with 50% aq. ethanol (50 mL/mmol), and the crude product eluted with 3% ammonia in 50% aq. ethanol. After evaporation, the product was used in the crude form for the next reaction step or purified using HPLC on the reversed phase using a linear gradient of MeOH in water.

General Method E: Attachment of Phosphonopropionic Acid

EDC (3 mmol) was added to the mixture of starting material (1 mmol) and diisopropyl phosphonopropionic acid (1.2 mmol) in DMF (10 mL/mmol) and the reaction mixture stirred under argon at 90 °C for 4 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo and the desired product obtained by column chromatography on silica gel using a linear gradient of the H1 system in ethyl acetate.

General Method F: Deesterification of Phosphonates

Di- or tetra-ester (1 mmol) was dissolved in MeCN (10 mL/mmol). TMSBr (5 or 7 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture stirred under an argon atmosphere at RT overnight. The solvent was removed in vacuo, the residue dissolved in 2 M aq. TEAB (5 mL/mmol) and EtOH (5 mL/mmol) and again concentrated. The target compound was obtained using preparative HPLC on a reversed phase with the linear gradient of MeOH in 0.1 M aq. TEAB. Fractions containing the desired product (according to LC-MS) were combined and evaporated. The residue was coevaporated with MeOH (3 × 10 mL/mmol) to remove all remaining TEAB. Finally, the product was converted to the sodium salt by chromatography on Dowex 50 in Na+ form. The final product was lyophilized from water to form a white solid.

General Method G Synthesis of Prodrugs

A mixture of phosphonate ester,26 (0.5 mmol), dry pyridine (8 mL), and BrSiMe3 (1 mL) was stirred overnight at room temperature under argon. After evaporation and codistillation with pyridine (2 × 5 mL) under an argon atmosphere, the residue was dissolved in dry pyridine (10 mL) and ethyl (l)-phenylalanine hydrochloride (1.75 g, 7.1 mmol) and triethylamine (3.1 mL) were added. The mixture was heated to 70 °C under an argon atmosphere, and then a solution of aldrithiol (2.31 g, 10.5 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (2.75 g, 10.5 mmol) in dry pyridine (8 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was heated at 70 °C for 3 days, the solvent was evaporated, and the residue was coevaporated with toluene (2 × 10 mL) and purified by column chromatography on silica gel (gradient CHCl3-MeOH) and the crude product further purified by preparative HPLC.

[2S,4R]-1-N-tert-Butyloxycarbonyl-4-dimethoxytrityloxy-2-hydroxymethylpyrrolidine (6a)

To a solution of [2S,4R]-1-N-tert-butyloxycarbonyl-2-(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)methyl-4-hydroxypyrrolidine (26.5 g, 80 mmol) in dry pyridine (800 mL), dimethoxytrityl chloride (32.5 g, 96 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The reaction was quenched by the addition of dry MeOH (10 mL), and the reaction mixture was concentrated, diluted with ethyl acetate (500 mL), and washed with brine (3 × 100 mL). The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, evaporated, and purified by chromatography on silica gel using a linear gradient of ethyl acetate in cyclohexane. To the obtained product, a freshly prepared 0.5 M solution of TBAF in THF (mL) was added and the mixture stirred for 10 min. Dowex 50 in Et3NH+ form was added and the mixture filtered and concentrated under vacuum. Compound 6a was obtained by chromatography on silica gel using a linear gradient of ethyl acetate in toluene in 86% yield (35.8 g) in the form of a yellow foam.

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, DMSO-d6, T = 80 °C): 1.35 (s, 9H, (CH3)3C); 1.80 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 12.9, J3b,2 = 6.2, J3b,4 = 4.6, H-3b); 1.86 (bddd, 1H, Jgem = 12.9, J3a,4 = 7.6, J3a,2 = 6.0, H-3a); 2.69, 2.77 (2 × bm, 2 × 1H, H-5); 3.26 (dt, 1H, Jgem = 10.6, JHb,2 = JHb,OH = 5.5, CHbHaO); 3.32 (bddd, 1H, Jgem = 10.6, JHa,OH = 4.7, JHa,2 = 3.8, CHbHaO); 3.756, 3.759 (2 × s, 2 × 3H, 2 × CH3O); 3.79 (bm, 1H, H-2); 4.19 (m, 1H, H-4); 4.33 (bdd, 1H, J = 5.5, 4.7, OH); 6.87–6.92 (m, 4H, H-m-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 7.23 (m, 1H, H-p-C6H5-DMTr); 7.25–7.30 (m, 4H, H-o-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 7.30–7.33 (m, 2H, H-m-C6H5-DMTr); 7.38–7.41 (m, 2H, H-o-C6H5-DMTr).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, DMSO-d6, T = 80 °C): 27.79 ((CH3)3C); 35.07 (b, CH2–3); 52.22 (CH2–5); 54.79 (CH3O–DMTr); 56.94 (CH-2); 62.09 (CH2O); 71.22 (b, CH-4); 77.84 ((CH3)3C); 85.69 (C-DMTr); 112.99, 113.02 (CH-m-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 126.31 (CH-p-C6H5-DMTr); 127.39 (CH-m-C6H5-DMTr); 127.47 (CH-o-C6H5-DMTr); 129.36, 129.39 (CH-o-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 136.12, 136.27 (C-i-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 145.22 (C-i-C6H5-DMTr); 153.46 (CO); 158.01 (C-p-C6H4OMe-DMTr).

IR νmax (CHCl3) 3626 (vw), 3361 (w), 3087 (w), 3061 (w), 2980 (m), 2957 (m), 2936 (m), 2839 (m), 1687 (s, sh), 1662 (s), 1608 (s), 1582 (w), 1509 (vs), 1495 (m), 1478 (m), 1464 (s), 1456 (s), 1446 (s), 1442 (s), 1412 (vs), 1393 (s, sh), 1368 (s), 1340 (m), 1302 (m), 1252 (vs), 1179 (vs), 1175 (vs), 1154 (s), 1117 (m), 1081 (s), 1070 (m, sh), 1035 (s), 1011 (m), 1002 (vw), 912 (w), 836 (m), 830 (s), 705 (m), 700 (m), 638 (w), 612 (w), 595 (m), 584 (m), 466 (w).

HR-ESI C31H37O6NNa (M+Na)+ calcd 542.25131, found 542.25101.

[2R,4S]-1-N-tert-Butyloxycarbonyl-4-dimethoxytrityloxy-2-hydroxymethylpyrrolidine (6b)

This compound was prepared using the same procedure as for its enantiomer 6a. All the spectra were identical to those for 6a.

[2S,4R]-1-N-tert-Butyloxycarbonyl-4-hydroxy-2-(diethylphosphono)ethoxymethyl-pyrrolidine (7a)

Compound 7a was prepared from 6a (7 g, 13.5 mmol) according to general procedure A. Yield 3.95 g, 77%.

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, DMSO-d6, T = 80 °C): 1.24 (t, 6H, Jvic = 7.0, CH3CH2O); 1.42 (s, 9H, (CH3)3C); 1.86 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 13.0, J3b,2 = 7.9, J3b,4 = 4.4, H-3b); 1.96 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 13.0, J3a,4 = 7.6, J3a,2 = 6.0, H-3a); 2.01 (dt, 2H, JH,P = 18.3, Jvic = 7.2, PCH2CH2O); 3.21–3.30 (m, 2H, H-5); 3.44 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 9.6, JHb,2 = 6.1, CHbHaO); 3.51 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 9.6, JHa,2 = 3.2, CHbHaO); 3.60 (dt, 2H, JH,P = 13.3, Jvic = 7.2, PCH2CH2O); 3.89 (dddd, 1H, J2,3 = 7.9, 6.0, J2,CH2 = 6.1, 3.2, H-2); 3.94–4.06 (m, 4H, CH3CH2O); 4.24 (m, 1H, H-4); 4.69 (bs, 1H, OH).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, DMSO-d6, T = 80 °C): 15.98 (d, JC,P = 5.6, CH3CH2O); 26.27 (d, JC,P = 137.4, PCH2CH2O); 28.04 ((CH3)3C); 37.24 (CH2–3); 54.56 (CH2–5); 55.23 (CH-2); 60.77 (d, JC,P = 6.2, CH3CH2O); 64.67 (PCH2CH2O); 67.80 (C-4); 71.09 (CH2O); 78.19 ((CH3)3C); 153.72 (CO).

31P[1H] NMR (202.3 MHz, DMSO-d6, T = 80 °C): 28.12.

IR νmax (CHCl3) 3613 (w), 3401 (w, vbr), 2984 (s), 2932 (m), 2874 (m), 1686 (vs), 1478 (m), 1455 (m), 1443 (m), 1405 (vs), 1393 (vs, sh), 1368 (s), 1246 (s, br), 1165 (s), 1099 (s, sh), 1055 (vs), 1030 (vs), 963 (s), 463 (vw).

HR-ESI C16H33O7NP (M+H)+ calcd 382.19892, found 382.19906; C16H32O7NPNa (M+Na)+ calcd 404.18086, found 404.18095.

[2R,4S]-1-N-tert-Butyloxycarbonyl-4-hydroxy-2-(diethyl phosphono)ethoxymethyl-pyrrolidine (7b)

This compound was prepared using the same procedure as for its enantiomer 7a. All the spectra were identical to those for 7a.

[2S,4S]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-(2-(diethyl phosphono)ethoxymethyl)pyrrolidine (8a)

8a was prepared from 7a (2.97 g, 7.79 mmol) in the presence of triphenylphosphine (4.5 g, 27.27 mmol) according to general procedures C and D. Yield 1.27 g, 39%.

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1.209, 1.212 (2 × t, 2 × 3H, Jvic = 7.3, CH3CH2O); 1.67 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 13.3, J3′b,2′ = 8.1, J3′b,4′ = 6.5, H-3′b); 1.99–2.13 (m, 2H, PCH2CH2O); 2.38 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 13.3, J3′a,4′ = 8.4, J3′a,2′ = 7.8, H-3′a); 3.00 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.1, J5′b,4′ = 4.8, H-5′b); 3.14 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.1, J5′a,4′ = 6.9, H-5′a); 3.28 (m, 1H, H-2′); 3.42 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 9.6, JHb,2′ = 5.3, CHbHaO); 3.46 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 9.6, JHa,2′ = 6.3, CHbHaO); 3.61 (dt, 2H, JH,P = 13.0, Jvic = 7.3, PCH2CH2O); 3.92–4.03 (m, 4H, CH3CH2O); 4.73 (dddd, 1H, J4′,3′ = 8.4, 6.5, J4′,5′ = 6.9, 4.8, H-4′); 6.43 (bs, 2H, NH2); 7.81 (s, 1H, H-8).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, DMSO-d6): 16.26 (d, JC,P = 5.7, CH3CH2O); 25.94 (d, JC,P = 136.9, PCH2CH2O); 35.44 (CH2–3′); 52.16 (CH2–5′); 53.78 (CH-4′); 57.07 (CH-2′); 60.98 (d, JC,P = 6.1, CH3CH2O); 64.54 (PCH2CH2O); 73.43 (CH2O); 116.59 (C-5); 135.58 (CH-8); 150.88 (C-4); 153.34 (C-2); 156.84 (C-6).

31P[1H] NMR (202.4 MHz, DMSO-d6): 29.81.

[2R,4R]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-(2-(diethyl phosphono)ethoxymethyl)pyrrolidine (8b)

This compound was prepared using the same procedure as for its enantiomer 8a. All the spectra were identical to those for 8a.

[2S,4S]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-(2-phosphonoethoxymethyl)-1-N-(3-phosphonopropionyl)pyrrolidine (4)

Compound 4 was prepared from 8a (0.40 g,

0.97 mmol) and diisopropyl phosphonopropionic acid according to general

procedures E and F. Yield 220 mg, 39%.

A:B ∼ 3:1

1H NMR (500.2 MHz, D2O, ref(dioxan) = 3.75 ppm): 1.77–2.00 (m, 8H, PCH2CH2O-A,B, PCH2CH2CO-A,B); 2.39–2.52 (m, 2H, H-3′b-A,B); 2.57–2.80 (m, 5H, H-3′a-A, PCH2CH2CO-A,B); 2.84 (dt, 1H, Jgem = 13.7, J3′a,2′ = J3′a,4′ = 8.4, H-3′a-B); 3.59 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 10.6, Jvic = 6.0, CHaHbO–B); 3.65–3.79 (m, 8H, H-5′b-B, CHaHbO–B, CH2O-A, PCH2CH2O-A,B); 3.89 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.1, J5′b,4′ = 8.8, H-5′b-A); 4.30 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.1, J5′a,4′ = 7.4, H-5′a-A); 4.35 (m, 1H, H-2′-A); 4.42 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 12.4, J5′a,4′ = 7.5, H-5′a-B); 4.49 (m, 1H, H-2′-B); 4.85 (m, 1H, H-4′-B); 4.90 (m, 1H, H-4′-A); 7.93 (s, 1H, H-8-B); 7.94 (s, 1H, H-8-A).

13C NMR (125.8 MHz, D2O, ref(dioxan) = 69.30 ppm): 25.97 (d, JC,P = 134.8, PCH2CH2CO-A); 26.51 (d, JC,P = 134.9, PCH2CH2CO-B); 30.53 (d, JC,P = 2.0, PCH2CH2CO-A); 31.50 (d, JC,P = 129.5, PCH2CH2O-A,B); 32.14 (d, JC,P = 2.3, PCH2CH2CO-A); 35.18 (CH2–3′-A); 36.17 (CH2–3′-B); 52.02 (CH2–5′-B); 53.84 (CH2–5′-A); 54.17 (CH-4′-B); 54.80 (CH-4′-A); 58.61 (CH-2′-A); 59.00 (CH-2′-B); 69.66 (d, JC,P = 1.4, PCH2CH2O-A); 69.70 (d, JC,P = 1.4, PCH2CH2O–B); 72.32 (CH2O-A); 74.43 (CH2O–B); 118.85 (C-5-A); 118.94 (C-5-B); 140.42 (CH-8-A,B); 154.45 (C-4-A,B); 156.26 (C-2-B); 156.30 (C-2-A); 161.56 (C-6-A,B); 177.01 (d, JC,P = 18.1, NCO-A); 177.60 (d, JC,P = 17.5, NCO-B).

31P[1H] NMR (202.5 MHz, D2O): 21.26 (PCH2CH2CO-B); 21.35 (PCH2CH2CO-A); 24.27 (PCH2CH2O–B); 24.38 (PCH2CH2O-A).

IR νmax (KBr) 3307 (m, br), 3113 (m, br), 2782 (m, vbr), 2368 (w, vbr), 1693 (vs), 1637 (s, br), 1613 (s, sh), 1575 (w, sh), 1534 (w), 1478 (w), 1416 (w), 1320 (w), 1070 (m, br), 898 (m, br), 781 (w), 695 (w), 640 (vw).

HR-ESI C15H23O9N6P2 (M-H)− calcd 493.10072, found 493.09988.

[α]D20 −11.4 (c 0.342, H2O)

[2R,4R]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-(2-phosphonoethoxymethyl)-1-N-(3-phosphonopropionyl)pyrrolidine (3)

Compound 3 was prepared from 8b (0.15 g, 0.36 mmol) and diisopropyl phosphonopropionic acid according to general procedures E and F. Yield 15 mg, 7%. All the spectra were identical to those for 4.

[2S,4S]-1-N-tert-Butyloxycarbonyl-4-hydroxy-2-(diethyl phosphono)ethoxymethylpyrrolidine (9a)

Compound 9a was prepared from 7a (1.95g, 4.8 mmol) according to general procedure B. Yield 1.36 g, 69%.

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1.25 (t, 6H, Jvic = 7.0, CH3CH2O); 1.42 (s, 9H, (CH3)3C); 1.84 (dtd, 1H, Jgem = 13.3, J3b,2 = J3b,4 = 3.5, J3b,5b = 1.2, H-3b); 1.98–2.09 (m, 3H, H-3a, PCH2CH2O); 3.06 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 11.3, J5b,4 = 3.5, J5b,3b = 1.2, H-5b); 3.48 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.3, J5a,4 = 5.5, H-5a); 3.54 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 9.2, JHb,2 = 7.9, CHaHbO); 3.57–3.68 (m, 3H, CHaHbO, OCH2CH2P); 3.81 (tt, 1H, J2,3 = 7.9, 3.5, J2,CH2 = 7.9, 3.5, H-2); 3.95–4.08 (m, 4H, CH3CH2O); 4.20 (tt, 1H, J4,3 = 5.5, 3.5, J4,5 = 5.5, 3.5, H-4); 4.69 (s, 1H, OH).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, DMSO-d6): 15.92 (d, JC,P = 5.6, CH3CH2O); 26.26 (d, JC,P = 137.3, PCH2CH2O); 27.96 ((CH3)3C); 36.23 (CH2–3); 54.62 (CH2–5); 55.45 (CH-2); 60.74 (d, JC,P = 6.3, CH3CH2O); 64.38 (d, JC,P = 1.2, OCH2CH2P); 68.42 (CH-4); 71.27 (CH2O); 78.22 ((CH3)3C); 153.48 (CO).

31P[1H] NMR (202.3 MHz, DMSO-d6): 28.02.

IR νmax (CHCl3) 3610 (vw), 3421 (m, br), 2983 (s), 2939 (m), 2875 (m), 1686 (vs), 1478 (m), 1469 (m), 1456 (m), 1444 (m), 1401 (vs, sh), 1394 (vs), 1367 (s), 1246 (s), 1167 (s), 1111 (s), 1088 (s), 1053 (vs), 1029 (vs), 963 (s), 463 (vw).

HR-ESI C16H33O7NP (M+H)+ calcd 382.19892, found 382.19871; C16H32O7NPNa (M+Na)+ calcd 404.18086, found 404.18061.

[2R,4R]-1-N-tert-Butyloxycarbonyl-4-hydroxy-2-(diethylphosphono)ethoxymethylpyrrolidine (9b)

This compound was prepared using the same procedure as for its enantiomer 9a. All the spectra were identical to those for 9a.

[2S,4R]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-(2-(diethyl phosphono)ethoxymethyl)pyrrolidine (10a)

Compound 10a was prepared from 9a (2 g, 5.24 mmol) according to general procedures C and D. Yield 0.94 g, 43%.

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1.22 (t, 6H, Jvic = 7.1, CH3CH2O); 1.94 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 13.7, J3′b,4′ = 8.1, J3′b,2′ = 7.0, H-3′b); 2.02–2.10 (m, 3H, H-3′a, PCH2CH2O); 2.98 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.3, J5′b,4′ = 4.6, H-5′b); 3.22 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.3, J5′a,4′ = 6.3, H-5′a); 3.32 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 9.5, JHb,2′ = 5.8, CHbHaO); 3.35 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 9.5, JHa,2′ = 6.1, CHbHaO); 3.55 (m, 1H, H-2′); 3.60 (dt, 2H, JH,P = 13.2, Jvic = 7.3, PCH2CH2O); 3.93–4.03 (m, 4H, CH3CH2O); 4.74 (m, 1H, H-4′); 6.43 (bs, 2H, NH2); 7.76 (s, 1H, H-8).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, DMSO-d6): 16.28 (d, JC,P = 5.9, CH3CH2O); 25.93 (d, JC,P = 136.9, PCH2CH2O); 35.16 (CH2–3′); 52.05 (CH2–5′); 54.24 (CH-4′); 56.31 (CH-2′); 61.00 (d, JC,P = 6.1, CH3CH2O); 64.54 (PCH2CH2O); 73.52 (CH2O); 116.73 (C-5); 135.70 (CH-8); 150.88 (C-4); 153.32 (C-2); 156.85 (C-6).

31P[1H] NMR (202.4 MHz, DMSO-d6): 29.84.

IR νmax (CHCl3) 3475 (w, vbr, sh), 3316 (w, vbr), 3130 (m, vbr), 2930 (m), 1692 (vs), 1658 (m), 1620 (w), 1576 (w), 1534 (w), 1479 (w), 1406 (w, sh), 1393 (w), 1376 (w), 1245 (w, sh), 1099 (vw), 1056 (m), 1029 (m), 964 (w), 638 (vw).

HR-ESI C16H28O5N6P (M+H)+ calcd 415.18533, found 415.18507; C16H27O5N6PNa (M+Na)+ calcd 437.16728, found 437.16689.

[2R,4S]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-(2-(diethyl phosphono)ethoxymethyl)pyrrolidine (10b)

The titled compound was prepared using the same procedure as for its enantiomer 10a. All the spectra were identical to those for 10a.

[2R,4S]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-(2-phosphonoethoxymethyl)-1-N-(3-phosphonopropionyl)pyrrolidine (2)

Compound 2 was prepared from 10b (0.42

g, 1.00 mmol) and diisopropyl phosphonopropionic acid according to

general procedures E and F. Yield 280 mg,

48%.

A:B ∼ 8:3

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, D2O, ref(dioxan) = 3.75 ppm): 1.67–1.88 (m, 4H, PCH2CH2CO-A,B); 1.92–2.09 (m, 4H, PCH2CH2O-A,B); 2.46–2.84 (m, 8H, H-3′-A,B, PCH2CH2CO-A,B); 3.64–3.84 (m, 8H, CH2O-A,B, PCH2CH2O-A,B); 3.87–3.94 (m, 3H, H-5′b-A, H-5′-B); 4.15 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.3, J5′a,4′ = 7.4, H-5′a-A); 4.51 (m, 1H, H-2′-A); 4.60 (m, 1H, H-2′-B); 5.21–5.30 (m, 2H, H-4′-A,B); 7.84 (s, 2H, H-8-A,B).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, D2O, ref(dioxan) = 69.30 ppm): 26.04 (d, JC,P = 134.3, PCH2CH2CO-A); 26.67 (d, JC,P = 133.9, PCH2CH2CO-B); 30.88 (PCH2CH2CO-B); 31.86 (d, JC,P = 128.7, PCH2CH2O-A,B); 32.07 (PCH2CH2CO-A); 35.51 (CH2–3′-A); 36.70 (CH2–3′-B); 53.25 (CH2–5′-B); 54.46 (CH2–5′-A); 54.62 (CH-4′-B); 55.47 (CH-4′-A); 58.95 (CH-2′-A); 59.78 (CH-2′-B); 70.16 (PCH2CH2O-A); 70.25 (PCH2CH2O–B); 72.62 (CH2O-A); 74.28 (CH2O–B); 118.98 (C-5-A); 119.04 (C-5-B); 140.63 (CH-8-A,B); 154.31 (C-4-A,B); 156.32 (C-2-B); 156.35 (C-2-A); 161.78 (C-6-A,B); 177.08 (d, JC,P = 18.5, NCO-A); 177.41 (d, JC,P = 18.5, NCO-B).

31P{1H} NMR (202.4 MHz, D2O): 20.81 (PCH2CH2CO-B); 20.89 (PCH2CH2CO-A); 23.68 (PCH2CH2O-A,B).

IR νmax (KBr) 3433 (s), 3112 (m), 2924 (m), 2855 (m, w), 1693 (vs), 1628 (s), 1536 (w), 1480 (w), 1176 (m), 1074 (m, br), 896 (w, br), 783 (w), 694 (w), 641 (w).

HR-ESI C15H23O9N6P2 (M-H)− calcd 493.10072, found 493.10061.

[α]D20 +13.9 (c 0.375, H2O)

[2S,4R]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-(2-phosphonoethoxymethyl)-1-N-(3-phosphonopropionyl)pyrrolidine (5)

Compound 5 was prepared from 10a (341 mg, 0.82 mmol) and diisopropyl phosphonopropionic acid according to general procedures E and F. Yield 138 mg, 29%. All the spectra were identical to those for 2.

[α]D20 −11.4 (c 0.395, H2O)

[2S,4R]-1-N-tert-Butyloxycarbonyl-2-dimethoxytrityloxymethyl-4-hydroxypyrrolidine (11)

To a solution of [2S,4R]-1-N-tert-butyloxycarbonyl-4-hydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)pyrrolidine57 (50 g, 230 mmol) in dry pyridine (1,000 mL), dimethoxytrityl chloride (97 g, 253 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. The reaction was quenched by the addition of dry MeOH (10 mL), and the reaction mixture was concentrated, diluted with chloroform (500 mL), and washed with brine (3 × 100 mL). The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, evaporated, and purified by chromatography on silica gel using a linear gradient of toluene in ethyl acetate. Compound 11 was obtained in 85% yield (111.7 g) in the form of a yellow foam.

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, DMSO-d6, T = 80 °C): 1.31 (bs, 9H, (CH3)3C); 1.95 (bm, 1H, H-3b); 2.03 (bm, 1H, H-3a); 2.99–3.01 (bm, 2H, CH2O); 3.29–3.39 (bm, 2H, H-5); 3.75 (s, 6H, CH3O); 3.97 (bm, 1H, H-2); 4.31 (bm, 1H, H-4); 4.69 (bm, 1H, OH); 6.85–6.90 (m, 4H, H-m-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 7.19–7.26 (m, 5H, H-o-C6H4OMe-DMTr, H-p-C6H5-DMTr); 7.28–7.32 (m, 2H, H-m-C6H5-DMTr); 7.34–7.38 (m, 2H, H-o-C6H5-DMTr).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, DMSO-d6, T = 80 °C): 27.77 ((CH3)3C); 38.10 (b, CH2–3); 54.48 (b, CH2–5); 54.76 (CH3O–DMTr); 55.91 (b, CH-2); 55.29 (CH3O–DMTr); 64.01 (b, CH2O); 67.75 (b, CH-4); 77.88 ((CH3)3C); 85.01 (C-DMTr); 112.90 (CH-m-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 126.22 (CH-p-C6H5-DMTr); 127.32 (CH-m-C6H5-DMTr); 127.39 (CH-o-C6H5-DMTr); 129.25, 129.26 (CH-o-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 135.61, 135.68 (C-i-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 144.66 (C-i-C6H5-DMTr); 153.47 (CO); 157.86 (C-p-C6H4OMe-DMTr).

IR νmax (KBr) 3430 (m, vbr), 3087 (w, sh), 3058 (w), 3035 (w), 2974 (m), 2872 (m), 2836 (m), 1694 (vs), 1672 (s), 1608 (s), 1583 (m), 1509 (vs), 1478 (m), 1446 (s), 1407 (s), 1393 (s, sh), 1366 (s), 1302 (s), 1251 (vs), 1175 (vs), 1161 (s, sh), 1115 (m), 1104 (m), 1086 (m, sh), 1074 (m), 1055 (m), 1035 (s), 1012 (m, sh), 914 (w), 829 (s), 772 (m), 727 (m), 702 (m), 635 (w), 596 (m), 585 (m), 548 (w), 465 w.

HR-ESI C31H37O6NNa (M+Na)+ calcd 542.25131, found 542.25110.

[2S,4S]-1-N-tert-Butyloxycarbonyl-2-dimethoxytrityloxymethyl-4-hydroxypyrrolidine (12)

Compound 12 was prepared from 11 (10.1 g, 19.4 mmol) according to general procedure B. Yield 8.05 g, 80%.

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, DMSO-d6, T = 80 °C): 1.29 (bs, 9H, (CH3)3C); 1.97 (bm, 1H, H-3b); 2.16 (bddd, 1H, Jgem = 13.7, J3a,4 = 8.3, J3a,2 = 6.2, H-3a); 3.01 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.2, J5b,4 = 4.2, H-5b); 3.16 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 8.3, JHb,2 = 7.6, CHbHaO); 3.25 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 8.3, JHa,2 = 4.5, CHbHaO); 3.55 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.2, J5a,4 = 5.8, H-5a) 3.755 (s, 6H, CH3O); 3.90 (m, 1H, H-2); 4.20 (bm, 1H, H-4); 4.70 (bm, 1H, OH); 6.85–6.89 (m, 4H, H-m-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 7.21 (m, 1H, H-p-C6H5-DMTr); 7.24–7.32 (m, 6H, H-o-C6H4OMe-DMTr, H-m-C6H5-DMTr); 7.38–7.41 (m, 2H, H-o-C6H5-DMTr).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, DMSO-d6, T = 80 °C): 27.72 ((CH3)3C); 36.30 (b, CH2–3); 54.08 (CH2–5); 54.75 (CH3O–DMTr); 55.65 (CH-2); 64.19 (CH2O); 67.98 (b, CH-4); 77.94 ((CH3)3C); 85.04 (C-DMTr); 112.83, 112.84 (CH-m-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 128.15 (CH-p-C6H5-DMTr); 127.24 (CH-m-C6H5-DMTr); 127.49 (CH-o-C6H5-DMTr); 129.34, 129.36 (CH-o-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 135.79, 135.82 (C-i-C6H4OMe-DMTr); 144.81 (C-i-C6H5-DMTr); 153.20 (CO); 157.82 (C-p-C6H4OMe-DMTr).

IR νmax (CHCl3) 3612 (w), 3421 (m, br), 3086 (w), 3061 (w), 2977 (s), 2960 (s, sh), 2937 (s), 2911 (m), 2880 (w, sh), 2839 (m), 1686 (vs), 1609 (s), 1584 (m), 1580 (m, sh), 1510 (vs), 1493 (m), 1465 (s), 1478 (m), 1447 (s), 1442 (s), 1401 (vs), 1392 (s), 1367 (s), 1340 (m), 1252 (vs), 1177 (vs), 1167 (s, sh), 1155 (s, sh), 1124 (s), 1088 (s), 1055 (s, sh), 1037 (vs), 1013 (m), 1005 (m), 936 (w), 915 (w), 830 (s), 704 (m), 635 (vw), 629 (w), 619 (vw), 596 (m), 585 (s), 461 (vw).

HR-ESI C31H37O6NNa (M+Na)+ calcd 542.25131, found 542.25126.

[2S,4R]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-hydroxymethylpyrrolidine (13)

Compound 13 was prepared from 12 (2.43 g, 4.68 mmol) in the presence of diphenylpyridylphosphine (2.46 g, 9.35 mmol) according to general procedures C and D. Yield 0.66 g, 56.8%.

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, DMSO-d6): 1.97 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 13.5, J3′b,4′ = 8.1, J3′b,2′ = 6.6, H-3′b); 2.02 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 13.5, J3′a,2′ = 7.8, J3′a,4′ = 4.8, H-3′a); 2.97 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.2, J5′b,4′ = 4.8, H-5′b); 3.23 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.2, J5′a,4′ = 6.4, H-5′a); 3.32 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 10.6, JHb,2′ = 5.6, CHbHaO); 3.36 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 10.3, JHa,2′ = 5.4, CHbHaO); 3.42 (dddd, 1H, J2′,3′ = 7.8, 6.6, J2′,CH2 = 5.6, 5.4, H-2′); 4.74 (ddt, 1H, J4′,3′ = 8.1, 4.8, J4′,5′ = 6.4, 4.8, H-4′); 6.45 (bs, 2H, NH2); 7.77 (s, 1H, H-8).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, DMSO-d6): 34.87 (CH2–3′); 52.13 (CH2–5′); 54.31 (CH-2′); 58.72 (CH-4′); 64.13 (CH2O); 116.69 (C-5); 135.65 (CH-8); 150.92 (C-4); 153.35 (C-2); 156.89 (C-6).

IR νmax (KBr) 3495 (s), 3424 (s, br, sh), 3319 (s, br), 3192 (s, br), 3125 (s), 2910 (s, sh), 2883 (s), 2825 (s, sh), 2848 (s), 2786 (s), 2733 (s, br), 1727 (s), 1689 (s), 1632 (vs), 1606 (s), 1536 (s), 1485 (s), 1388 (s), 1570 (s), 1329 (m), 1051 (m), 777 (m), 733 (w), 676 (m), 631 (w, br).

HR-ESI C10H15O2N6 (M+H)+ calcd 251.12510, found 251.12488; C10H14O2N6Na (M+Na)+ calcd 273.10704, found 273.10688.

[2S,4R]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-hydroxymethyl-1-N-(3-phosphonopropionyl)pyrrolidine (1)

Compound 1 was prepared from 13 (106 mg,

0.42 mmol) and diisopropyl phosphonopropionic acid according to general

procedures E and F. Yield 141 mg, 78%.

A:B ∼ 2:1

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, D2O, ref(tBuOH) = 1.24 ppm): 1.71–1.92 (m, 4H, PCH2CH2CO-A,B); 2.48–2.81 (m, 8H, H-3′-A,B, PCH2CH2CO-A,B); 3.68 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.7, Jvic = 3.2, CHaHbOH-A); 3.72 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 12.2, Jvic = 4.9, CHaHbOH-B); 3.82 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 12.2, Jvic = 5.2, CHaHbOH-B); 3.86–3.98 (m, 4H, H-5b-A, H-5-B, CHaHbOH-A); 4.13 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.5, J5′a,4′ = 7.1, H-5′a-A); 4.44 (m, 1H, H-2′-A); 4.52 (m, 1H, H-2′-B); 5.13–5.22 (m, 2H, H-4′-A,B); 7.80 (s, 1H, H-8-A); 7.81 (s, 1H, H-8-B).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, D2O, ref(tBuOH) = 30.29 ppm): 23.85 (d, JC,P = 135.0, PCH2CH2CO-A); 24.47 (d, JC,P = 135.0, PCH2CH2CO-B); 28.68 (d, JC,P = 2.5, PCH2CH2CO-B); 29.87 (d, JC,P = 2.5, PCH2CH2CO-A); 33.06 (CH2-3′-A); 34.23 (CH2-3′-B); 51.36 (CH2-5′-B); 52.68 (CH-4′-B); 52.95 (CH2-5′-A); 53.62 (CH-4′-A); 58.76 (CH-2′-B); 59.40 (CH-2′-A); 62.19 (CH2O-A); 63.71 (CH2O–B); 116.87 (C-5-A); 116.93 (C-5-B); 138.35 (CH-8-A); 138.37 (CH-8-B); 152.11 (C-4-A); 152.13 (C-4-B); 154.19 (C-2-B); 154.22 (C-2-A); 156.54 (C-6-B); 159.56 (C-6-A); 174.90 (d, JC,P = 17.7, NCO-A); 175.24 (d, JC,P = 17.8, NCO-B).

31P[1H] NMR (202.4 MHz, D2O): 24.23 (P-A); 24.24 (P–B).

IR νmax (KBr) 3401 (s, vbr), 3187 (s, br), 311 (s, br), 2953 (s, br), 2506 (m, br), 2308 (s, br), 1676 (vs, br), 1610 (vs, vbr), 1590 (vs, br), 1536 (s), 1444 (s, br), 1144 (s), 1056 (s, br), 781 (s), 726 (m), 643 (s),

HR-ESI C13H19O6N6PNa (M+Na)+ calcd 409.09959, found 409.09965; C13H18O6N6PNa2 (M+2Na)+ calcd 431.08153, found 431.08145.

Bis(l-phenylalanine ethyl ester) Prodrug of [2S,4R]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-hydroxymethyl-1-N-(3-phosphonopropionyl)pyrrolidine 14

Compound 14 was prepared according to general procedure G in 41% yield (0.18 g, 0.244 mmol).

A mixture of two rotamers ∼ 7:2, NMR of major rotamer:

1H NMR (600.1 MHz, CD3OD): 1.19, 1.23 (2 × t, 2 × 3H, Jvic = 7.1, CH3CH2O); 1.59–1.71 (m, 2H, PCH2CH2CO); 2.09–2.24 (m, 2H, PCH2CH2CO); 2.47 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 12.9, J3′b,4′ = 7.3, J3′b,2′ = 3.2, H-3′b); 2.65–2.73 (m, 2H, H-3′a, H-3b-Phe); 2.83 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 13.6, J3b,2 = 8.8, H-3b-Phe); 2.96, 3.06 (2 × dd, 2 × 1H, Jgem = 13.6, J3a,2 = 5.4, H-3a-Phe); 3.59 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.2, J6′b,2′ = 2.9, H-6′b); 3.73 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 10.7, J5′b,4′ = 6.8, H-5′b); 3.83 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 11.2, J6′a,2′ = 4.5, H-6′a); 3.87 (m, 1H, H-2-Phe); 3.92 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 10.7, J5′a,4′ = 7.7, H-5′a; 4.04–4.18 (m, 5H, H-2-Phe, CH3CH2O); 4.35 (m, 1H, H-2′); 5.29 (m, 1H, H-4′); 7.09–7.29 (m, 10H, H-o,m,p-Phe); 7.80 (s, 1H, H-8).

13C NMR (150.9 MHz, CD3OD): 14.40, 14.49 (CH3CH2O); 24.72 (d, JC,P = 118.2, PCH2CH2CO); 29.14 (d, JC,P = 2.8, PCH2CH2CO); 33.48 (CH2–3′); 41.29 (d, JC,P = 5.0, CH2–3-Phe); 41.47 (d, JC,P = 6.5, CH2–3-Phe); 53.03 (CH2–5′); 54.45 (CH-4′); 55.56, 55.92 (CH-2-Phe); 59.90 (CH-2′); 62.28, 62.33 (CH3CH2O); 63.18 (CH2–6′); 118.18 (C-5); 127.92, 128.00 (CH-p-Phe); 129.45, 129.52 (CH-m-Phe); 130.59, 130.85 (CH-o-Phe); 137.96 (CH-8); 138.48, 138.60 (C-i-Phe); 153.08 (C-4); 155.13 (C-2); 159.38 (C-6); 172.85 (d, JC,P = 13.5, NCO); 174.74 (d, JC,P = 3.8, C-1-Phe); 174.85 (d, JC,P = 1.9, C-1-Phe).

31P{1H} NMR (202.5 MHz, CD3OD): 32.16.

IR νmax (CHCl3) 3485 (vw), 3386 (w), 3319 (w, vbr), 3110 (w, vbr), 3089 (vw), 3065 (vw), 3034 (vw), 2965 (vs), 1733 (m), 1690 (m), 1625 (m), 1606 (w, sh), 1589 (w, sh), 1573 (w, sh), 1534 (w), 1496 (w), 1480 (w, sh), 1473 (s), 1462 (m), 1455 (m), 1448 (m), 1443 (m), 1398 (m), 1391 (m), 1370 (w), 1316 (vw), 1239 (m), 1183 (m), 1165 (w), 1098 (vw), 1072 (w), 1061 (w), 1034 (w), 1022 (w), 919 (vw), 701 (w), 554 (vw).

HR-ESI C35H44O8N8P (M-H)1 calcd 735.30252, found 735.30214.

Tetra-(l-phenylalanine ethyl ester) Prodrug of [2S,4R]-4-Guanin-9-yl-2-(2-phosphonoethoxymethyl)-1-N-(3-phosphonopropionyl)pyrrolidine 15

Compound 15 was prepared according to general procedure G in 12% yield (69 mg, 58 μmol).

A mixture of two rotamers ∼ 4:1, NMR of major rotamer:

1H NMR (500.0 MHz, CD3OD): 1.18, 1.19, 1.23, 1.26 (4 × t, 4 × 3H, Jvic = 7.1, CH3CH2O); 1.51–1.75 (m, 4H, PCH2CH2CO, PCH2CH2O); 2.01 (m, 1H, H-3′b); 2.04–2.20 (m, 2H, PCH2CH2CO); 2.33 (ddd, 1H, Jgem = 12.8, J3′a,4′ = 9.8, J3′a,2′ = 9.0, H-3′a); 2.69 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 13.6, Jvic = 8.2, H-3b-Phe); 2.77 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 13.4, Jvic = 7.5, H-3b-Phe); 2.82 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 13.5, Jvic = 8.7, H-3b-Phe); 2.91 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 13.5, Jvic = 7.9, H-3b-Phe); 2.93–2.99, 3.03–3.09 (2 × m, 2 × 2H, H-3a-Phe); 3.39–3.53 (m, 4H, OCH2, PCH2CH2O); 3.61 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 10.5, J5′b,4′ = 7.8, H-5′b); 3.78 (dd, 1H, Jgem = 10.5, J5′a,4′ = 7.8, H-5′a); 3.86 (ddd, 1H, J2,3 = 9.0, 8.7, JH,P = 5.7, H-2-Phe); 3.93 (ddd, 1H, J2,3 = 9.2, 7.5, JH,P = 5.4, H-2-Phe); 4.01–4.24 (m, 11H, H-2′, H-2-Phe, CH3CH2O); 5.13 (dq, 1H, J4′,3′ = 9.0, 7.8, J4′,5′ = 7.8, H-4′); 7.09–7.32 (m, 20H, H-o,m,p-Ph); 7.68 (s, 1H, H-8).

13C NMR (125.7 MHz, CD3OD): 14.43, 14.46, 14.50, 14.55 (CH3CH2O); 24.63 (d, JC,P = 118.2, PCH2CH2CO); 29.09 (d, JC,P = 2.0, PCH2CH2CO); 31.11 (d, JC,P = 115.0, PCH2CH2O); 33.04 (CH2–3′); 41.21–41.51 (m, CH2-3-Phe); 52.07 (CH2-5′); 54.35 (CH-4′); 55.28, 55.53, 55.71, 55.85 (CH-2-Phe); 57.51 (CH-2′); 62.26, 62.30, 62.35, 62.43 (CH3CH2O); 66.71 (d, JC,P = 5.0, PCH2CH2O); 71.75 (OCH2); 118.15 (C-5); 127.89, 127.93, 127.99 (CH-p-Ph); 129.43, 129.49, 129.51 (CH-m-Ph); 130.61, 130.86, 130.87 (CH-o-Ph); 138.41, 138.49, 138.63 (C-i-Ph); 138.38 (CH-8); 138.41, 138.49, 138.63 (C-i-Ph); 153.08 (C-4); 155.08 (C-2); 159.44 (C-6); 172.72 (d, JC,P = 13.7, NCO); 174.49 (d, JC,P = 5.4, C-1-Phe); 174.67 (d, JC,P = 3.9, C-1-Phe); 174.78, 174.79 (2 × d, JC,P = 3.6, C-1-Phe).

31P{1H} NMR (202.4 MHz, CD3OD): 30.88, 32.07.

IR νmax (CHCl3) 3386 (w), 3340 (w), 3302 (w), 3235 (w, br), 3202 (v, br), 3111 (vw), 3088 (vw), 3066 (vw), 3031 (w), 2985 (m), 2929 (w), 2909 (w), 2875 (w), 1737 (vs), 1693 (s), 1635 (s), 1603 (m), 1595 (m, sh), 1571 (m), 1536 (w), 1496 (w), 1485 (w), 1476 (w), 1455 (w), 1444 (m), 1428 (m), 1394 (w), 1369 (m), 1341 (w), 1236 (m), 1198 (s, sh), 1180 (s), 1158 (m), 1116 (m), 1098 (m, sh), 1079 (w), 1030 (m), 990 (w), 966 (w), 910 (w), 857 (w), 702 (m), 508 (vw).

HR-ESI C59H77O13N10P2 (M+H)+ calcd 1195.51413, found 1195.51577.

Determination of Ki Values

All the H/G/XPRTs were expressed and purified to homogeneity as previously described.31,34,41−43,45 The Km for PRPP and the Ki values for the compounds were measured in a continuous spectrophotometric assay in 0.1 M Tris–HCl, 0.01 M MgCl2, pH 7.4, 25 °C. The substrates and inhibitor were added to the cuvette, the reaction initiated by the addition of enzyme and followed for 60 s at 257.5 nm. The concentration of guanine was fixed at 60 μM, and the concentration of PRPP varied between 5 and 1000 μM depending on the Km(app) in the presence of the inhibitor. The Δε for the reaction is 5816.5 M–1 cm–1. GraphPad Prism was used to calculate the Ki value using the equation for competitive inhibitors, Km(app) = Km(1+[I]o/Ki).

Crystallization and Structure Determination