Abstract

Background:

Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) is used to map neuronal circuitry in the brain and restore lost sensory function, including vision, hearing, and somatosensation. The temporal response of cortical neurons to single pulse ICMS is remarkably stereotyped and comprises short latency excitation followed by prolonged inhibition and, in some cases, rebound excitation. However, the neural origin of the different response components to ICMS are poorly understood, and the interactions between the three response components during trains of ICMS pulses remains unclear.

Objective:

We used computational modeling to determine the mechanisms contributing to the temporal response to ICMS in model cortical neurons.

Methods:

We implemented a biophysically based computational model of a cortical column comprising neurons with realistic morphology and synapses and quantified the temporal response of cortical neurons to different ICMS protocols. We characterized the temporal responses to single pulse ICMS across stimulation intensities and inhibitory (GABA-B/GABA-A) synaptic strengths. To probe interactions between response components, we quantified the response to paired pulse ICMS at different inter-pulse intervals and the response to short trains at different stimulation frequencies. Finally, we evaluated the performance of biomimetic ICMS trains in evoking sustained neural responses.

Results:

Single pulse ICMS evoked short latency excitation followed by a period of inhibition, but model neurons did not exhibit post-inhibitory excitation. The strength of short latency excitation increased and the duration of inhibition increased with increased stimulation amplitude. Prolonged inhibition resulted from both after-hyperpolarization currents and GABA-B synaptic transmission. During the paired pulse protocol, the strength of short latency excitation evoked by a test pulse decreased marginally compared to those evoked by a single pulse for interpulse intervals (IPI) < 100 m s. Further, the duration of inhibition evoked by the test pulse was prolonged compared to single pulse for IPIs <50 m s and was not predicted by linear superposition of individual inhibitory responses. For IPIs>50 m s, the duration of inhibition evoked by the test pulse was comparable to those evoked by a single pulse. Short ICMS trains evoked repetitive excitatory responses against a background of inhibition. However, the strength of the repetitive excitatory response declined during ICMS at higher frequencies. Further, the duration of inhibition at the cessation of ICMS at higher frequencies was prolonged compared to the duration following a single pulse. Biomimetic pulse trains evoked comparable neural response between the onset and offset phases despite the presence of stimulation induced inhibition.

Conclusions:

The cortical column model replicated the short latency excitation and long-lasting inhibitory components of the stereotyped neural response documented in experimental studies of ICMS. Both cellular and synaptic mechanisms influenced the response components generated by ICMS. The non-linear interactions between response components resulted in dynamic ICMS-evoked neural activity and may play an important role in mediating the ICMS-induced precepts.

Keywords: Neural model, Cortical column, Intracortical microstimulation, Long-lasting inhibition, Rebound excitation, Short latency excitation

1. Introduction

Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) is a powerful tool both to probe neural circuits [1-3] and to produce artificial sensations of a variety of modalities, including vision, audition, and somatosensation [4-9]. For example, ICMS has been explored to restore movement-related sensations including touch and proprioception in persons with spinal cord injury [4,7,10]. The temporal response of cortical neurons in rodents and non-human primates (NHP) is remarkably stereotyped [1,11,12], and single pulse ICMS evokes short latency excitation (0–25 m s) followed by a period of inhibition (25–200 m s) and post-inhibitory rebound excitation (200–300 m s). However, the neural origins of this apparently ubiquitous response to single pulse ICMS are unclear, and interactions with subsequent stimulus pulses during trains of stimulation remain poorly understood.

Butovas and colleagues quantified the temporal response to ICMS of neurons in the somatosensory cortex (S1) of rats [1,13]. At stimulation threshold, single pulse ICMS evoked a short latency excitatory response followed by long-lasting inhibition [1], and a number of other groups subsequently replicated these findings [2,11,12,14-22]. The strength of short-latency excitation increased, and the duration of the inhibition became longer, with increased stimulation intensity [11,12]. Higher stimulation intensities or frequencies also precipitated rebound excitation following the inhibitory phase [1,12]. Subsequent pharmacological experiments revealed that the ICMS-induced inhibitory responses were dependent on GABA-B receptors [23]. Despite this understanding, no computational model exists that reproduces the stereotyped temporal effects of ICMS. Further, current experimental techniques used to quantify the neural responses to ICMS, such as 2-photon calcium imaging and microelectrode recordings, have limitations including limited temporal resolution, and short latency responses may be obscured by stimulation artifacts [1,24-26]. The relative contribution of various biophysical mechanisms including after-hyperpolarization (AHP) currents, short-term synaptic depression, and GABAergic synaptic transmission to the ICMS-induced inhibitory response are not known.

We used computational modeling to quantify and deconstruct the mechanisms underlying temporal responses to ICMS. We implemented a biophysically-based computational model of cortical neurons with realistic morphologies adapted from the Blue Brain library [27,28]. The model comprised five different cell types arranged vertically in a column with five layers [29], and each cell type included excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs from other cortical neurons. The results provide a mechanistic basis for the temporal responses to single pulse, paired pulses, and trains of ICMS and reveal the basis for the efficacy of “biomimetic” pulse trains in evoking more sustained neural responses.

2. Methods

2.1. Computational model of the cortical column

The computational model used in this study was developed in earlier work to study the spatial effects of ICMS and is described in detail elsewhere [29]. We implemented a computational model of a population of 6410 biophysically-based Hodgkin-Huxley style multi-compartment cortical neurons based on the Blue Brain cell library [27,28]. The model comprised three parts: (1) single-cell cortical neurons with realistic axon morphology, (2) synapses distributed on the dendritic tree of each neuron, and (3) the model neurons with synapses arranged in a cortical column with dimensions derived from histological sections from the rhesus macaque. The model neurons included five different cortical cell types: Layer 1 neurogliaform cell with dense axonal arbor (L1 NGC-DA), Layer 2/3 pyramidal cell (L2/3 PC), Layer 4 large basket cell (L4 LBC), Layer 5 thick tufted pyramidal cell (L5 TTPC) and Layer 6 tufted pyramidal cell (L6 TPC) (Fig. 1A). We incorporated synapses from the Blue Brain project to study the synaptic effects of ICMS [27]. For each cell type, the position of the postsynaptic compartments (on the dendritic tree) where an inbound synaptic connection was received was mapped in the Blue Brain project [27]. Fig. 1A shows the locations of excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic connections received by L5 PC cells from five different cell types (L1 NGC-DA, L2/3 PC, L4 LBC, L5 PC, and L6 PC). Further, Fig. S1 shows the locations of excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic connections received by L5 PC from all cortical cell types in the Blue Brain project. Neurons within the network were not interconnected, but rather isolated from one another, and were subjected to ongoing (intrinsic) synaptic inputs, synaptic events that were generated by stimulation, and the direct effects of stimulation.

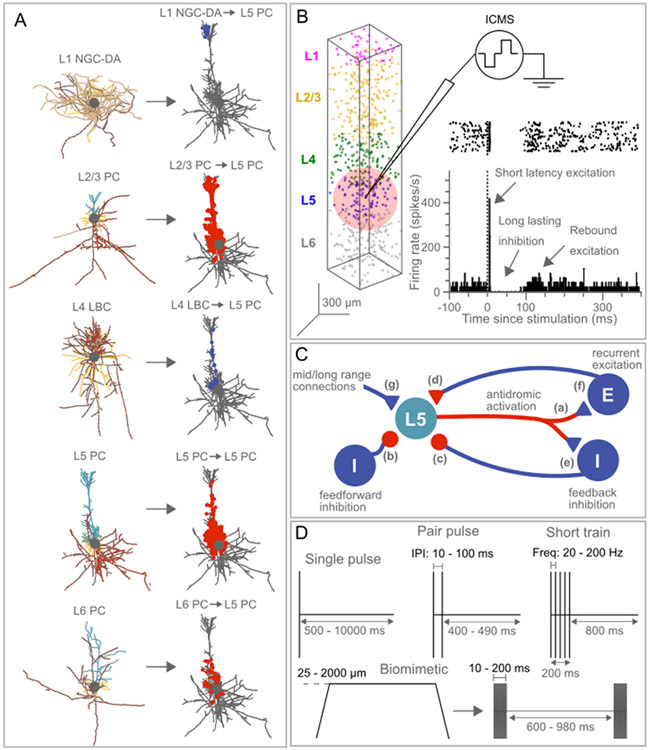

Fig. 1.

Biophysically-based computational model of intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) somatosensory cortex. (A) 3D morphology of Layer (L)-1 neuroglial cell, L2/3 pyramidal cell (PC), L4 basket cell, L5 thick tufted (TT) PC, L6 thick (T) PC. Model neurons were adapted from the Blue Brain library and had realistic axon morphologies [27,28]. Blue - apical dendrites, yellow-basal dendrites, brown - unmyelinated axon, gray - myelin, red - nodes of Ranvier, filled gray circle - soma. Model axons were myelinated, and the diameter range was consistent with those found in rhesus macaques [28,30]. Synaptic inputs to L5 PC from L1 NGC-DA, L2/3 PC, L4 LBC, L5 PC and L6 PC are shown in (A). Each cortical neuron (L1 NGC-DA, L2/3 PC, L4 LBC, L5 PC and L6 PC) received synaptic inputs from 55 presynaptic sources. All sources were cortical and did not include connections from other structures such as the thalamus, subcortex, etc. Excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic compartments are shown in red and blue-filled circles, respectively. Inhibitory synapses included GABA-A + GABA-B receptors and excitatory synapses included AMPA + NMDA receptors. The probability of synaptic activation to extracellular stimulation was an exponential function of the distance of the synapse from the electrode tip. (B) Cortical neurons were arranged in a column comprising five layers with dimensions of 400 μm × 400 μm × 2000 μm. Cortical thickness was determined from histological sections of the somatosensory cortex in the rhesus macaque [31], and the relative thickness of each layer was based on estimates from the visual cortex of rhesus macaque [32]. A uniform density of 20000 neurons/ mm3 was used across all layers, resulting in a total cell count of 6410 neurons for the cortical column. The stimulation electrode was in L5, and the neural response was recorded from L5 PCs with somas located within 150 μm from the stimulation electrode. The light pink circle indicates the recording volume around the stimulation electrode. The inset shows the stereotyped temporal response (raster and PSTH) to suprathreshold ICMS recorded experimentally in cortical neurons of rats including short latency excitation followed by a long-lasting inhibition and rebound excitation [1]. (C) Factors modulating the temporal response of L5 PC close to the stimulating microelectrode. The temporal response would be influenced by (a) direct activation of L5 PC, i.e., antidromic activation of soma due to direct activation of axon terminals, (b) synaptic activation of feedforward inhibitory terminals, (c) synaptic activation of feedback inhibitory terminals, (d) synaptic activation of recurrent excitatory terminals, (e) feedback inhibition due to activation of L5 PC → Interneurons → L5 PC, (f) recurrent excitation due to activation of L5 PC → other PC → L5 PC, and (g) synaptic activation of medium/long-range excitatory inputs (i.e., inputs from other cortical/subcortical regions). Neural elements marked in red show the effects captured in the model. E and I represent excitatory and inhibitory neurons, respectively. Triangular and circular terminals indicate excitatory and inhibitory synapses, respectively. (D) Four different ICMS protocols used in the model simulations: single pulse at different stimulation intensities/intervals, paired pulses at different inter-pulse intervals, short trains at different stimulation frequencies, and biomimetic stimulus at various indentation depths.

Each postsynaptic compartment contained models of both AMPA and NMDA receptor kinetics for excitatory connections and GABA-A and GABA-B receptor kinetics for inhibitory connections, as described in the original publication [27]. All inhibitory neurons in the model target both GABA-A and GABA-B receptors. However, the strength (conductance) of the GABA-A synaptic connection varies based on the pre- and post-synaptic cell types. The conductance of GABA-B synapses = conductance of the GABA-A synapses * GABA-B/GABA-A ratio. The synapses were modeled using a stochastic version of the Tsodyks-Markram model for dynamic synaptic transmission, including short-term facilitation (STF) and depression (STD). Tsodyks-Markram model were described by the following differential equations:

STD is simulated through variable , representing the fraction of resources available after neurotransmitter depletion. Variable denotes the fraction of resource ready to use for an upcoming spike and is used to simulate STF. is the decay time constant of the variable and is the recovery time constant of variable . representing synaptic efficacy, is the fraction of recovered neurotransmitter that is instantaneously released at each incoming spike. represents the postsynaptic current generated by a spike arriving at the time . is the decay time constant of the variable and is the maximum synaptic response possible following release of all neurotransmitters. The interplay between parameters , and is used to generate the effects of depression and facilitation. These parameters can be obtained from the original publication [27]. Fig. 2 shows an example of synaptic dynamics (IPSC) for a GABA-B synapse in response to a 2, 20, 100 and 200 Hz stimulation train, and synaptic dynamics for the AMPA, NMDA and GABA-A receptors are shown in Figs. S2-S4. The likelihood of activating a synapse by extracellular stimulation was an exponential function of the distance of the synapse from the electrode tip, and the space constant of the exponential function was larger for higher stimulation amplitudes than for lower amplitudes: 15 μA–50 μm, 30 μA–150 μm, 50 μA–250 μm, 100 μA–420 μm. Additional details on the derivation of spatial constants for synaptic activation are found elsewhere [29]. The cortical neurons with synapses were placed in a column with five layers (Fig. 1B), and details of the cortical column, including dimensions, the relative thickness of each layer, neural density, etc., are provided elsewhere [29].

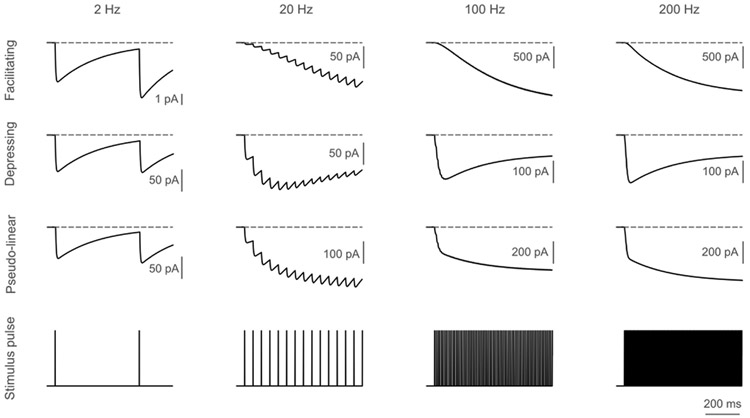

Fig. 2.

Properties of the (Tsodyks-Markram) GABA-B synapse. Inhibitory postsynaptic current (IPSC) showing dynamics of facilitating, depressing and pseudo-linear synapse in response to low (2, 20 Hz) and high (100, 200 Hz) frequency stimulation. The horizontal dashed line indicates 0 pA. See Supplementary Figs. S2-S4 for dynamics of other synapse types.

The overall objective of this study was to characterize the temporal response of cortical neurons close to the stimulation electrode, i.e., the activity of those neurons that can be recorded with the same electrode used for stimulation (Fig. 1B). The temporal response of L5 pyramidal cells (PC) close to the stimulating electrode would be primarily modulated by seven factors (Fig. 1C).

Direct activation of L5 PC, i.e., antidromic activation of soma due to direct activation of axon terminals,

Synaptic activation of feedforward inhibitory terminals,

Synaptic activation of feedback inhibitory terminals,

Synaptic activation of recurrent excitatory terminals,

Feedback inhibition due to activation of L5 PC → Interneurons → L5 PC,

Recurrent excitation due to activation of L5 PC → other PC → L5 PC,

Synaptic activation of medium/long-range excitatory inputs (i.e., inputs from other cortical/subcortical regions).

It is well established that during extracellular stimulation, action potentials are initiated in axon terminations [28,29,33,34]. Since the L5 PCs in our model include realistic axon morphologies, we capture the modulation of L5 temporal response from direct activation (a. above). From the Blue Brain project, we know the location of each synaptic input received by L5 PCs from a broad range of cortical input types (Fig. S1), including feedback, feedforward, and recurrent synaptic inputs. Using this information, in response to each stimulating pulse we activate these synapses based on their distance from the stimulating electrode – this is intended to mimic the effects of synaptic modulation of L5 PC due to direct activation of axon terminals of neurons projecting onto L5 PC (b.-d. above). However, the current model does not include effects due to feedback inhibition, recurrent excitation, and activation of inputs from other cortical or subcortical regions (e.-g. above). Although information on synaptic inputs received by other cell types from L5 PCs is available from the Blue Brain project (Fig. S5), setting up connections between neurons has been challenging due to the computational demand and paucity of information on synaptic dynamics. In the current version of the cortical column model, we model five cell types - L1 NGC-DA, L2/3 PC, L4 LBC, L5 TTPC and L6 TPC. However, L5 PCs receive synaptic inputs from 32 different cell types, and it is currently computationally infeasible to run such large-scale simulations, including all cell types and their connectivity. Even, the Blue Brain project, which simulated an entire cortical column including all cell types and connectivity between neurons on the IBM Blue Gene computer, replaced the realistic axon morphologies with stub axons to minimize the computational demand. We retained the realistic axon morphologies due to their prominent role in mediating the effects of extracellular stimulation.

2.2. Generation of intrinsic activity

To study the inhibitory effects of ICMS, the neurons must exhibit some ongoing intrinsic activity. We injected a 1.3 nA direct current (dc) intracellularly into the soma of each L5 PC, resulting in regular firing at a rate of ~20 Hz (Fig. 3A and B). In a subset of simulations, we studied the effect of different baseline firing rates on ICMS-induced temporal responses by modulating the intensity of the injected dc (1–2 nA in steps of 0.5 nA). We also generated intrinsic activity by driving excitatory synapses on the L5 PC with 20 Hz Poisson spike trains. This gave rise to an irregular firing activity in the model neurons at an average frequency of ~20 Hz (Figs. S12A and B). We also assessed the effect of the activation of different proportions of L5 excitatory synapses on the mean firing rate (Fig. S6). Driving only 10% of excitatory synapses with 20 Hz Poisson spikes did not generate any intrinsic activity in the model neurons (Fig. S6A). Driving 70%–100% of excitatory synapses with 20 Hz Poisson spikes yielded similar mean firing rates (13–21 Hz), with a 100% activation yielding a slightly higher firing rate than 70% (Fig. S6). Both intracellular current injection and ongoing synaptic input activity were used independently to generate intrinsic activity to assess the impact of the baseline firing on neural activity induced by single pulse, paired pulse, and biomimetic ICMS. Both methods produced identical results across the different stimulation protocols used in the study. Since both methods produced identical results, for the short-train stimulation protocol, intrinsic activity was generated only using ongoing synaptic inputs.

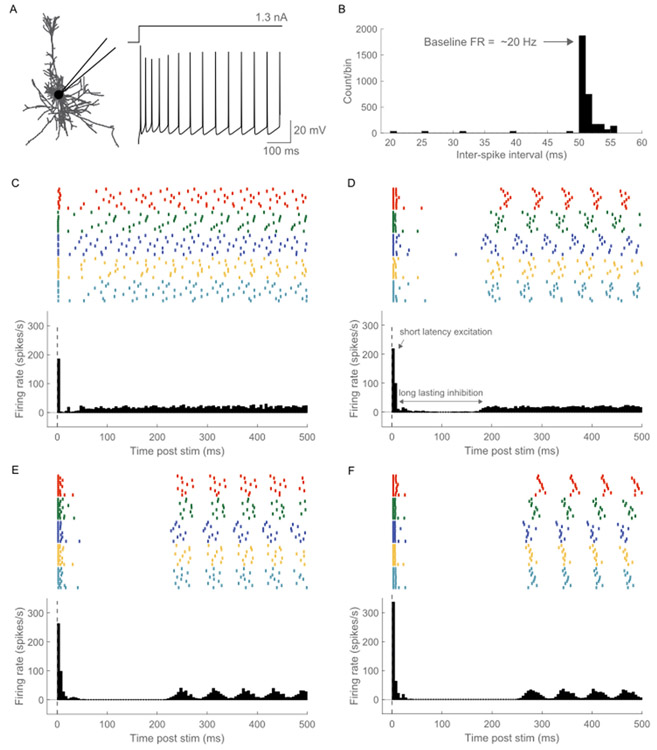

Fig. 3.

Temporal response of model neurons to ICMS at different stimulation intensities. (A) The intrinsic activity was generated by injecting a 1.3 nA dc current intracellularly into the soma of each neuron. (B) Inter-spike interval (ISI) histogram of baseline activity generated via injecting 1.3 nA dc into the soma of L5 PC. The model neurons exhibited a 20 Hz firing activity. Raster (top) and poststimulus time histogram (PSTH, below) to ICMS at (C) 15 μA, (D) 30 μA, (E) 50 μA and (F) 100 μA. Stimulation delivered at 2 Hz comprised a single biphasic pulse (cathodic first) with a fixed width of 200 μs/phase and an interphase interval of 50 μs. The stimulation electrode was in L5. Each color in the raster denotes a different L5 PC; within each neuron, a row represents one stimulus trial. The PSTH response was averaged across 34 L5 PCs with somas located within 150 μm from the stimulation electrode. The ratio was set at 1. A bin width of 5 m s was used to bin spike times. The temporal response to ICMS comprised short latency excitation followed by long-lasting inhibition. The strength of the excitatory response increased with stimulation intensity. Further, the duration of the inhibitory became longer with increased stimulation magnitude.

2.3. Neural data processing

Spiking activity was recorded from only those model neurons that were within a 150 μm radius around the stimulating electrode (Fig. 1B). Since the stimulating electrode was in L5 of the cortical column, activity was primarily recorded from L5 PCs. We constructed poststimulus time histograms (PSTH) by binning spike times in 5 m s bins across ten stimulation trials unless otherwise noted. We averaged the PSTH across ten stimulus trials for each neuron and then averaged the response across the neurons. The strength of the excitatory response was quantified by measuring the peak magnitude in the averaged PSTH response. Further, to quantify the relative contribution of direct versus synaptic activation to the excitatory response, we ran simulations of the model with and without synapses. We consider the relative contribution of direct activation to be peak excitatory response without synapses divided by the peak excitatory response in the model with synapses. For quantifying relative contribution of synaptic activation, we calculated the difference in peak excitatory response between the models with and without synapses and then divided that by the peak excitatory response in the model with synapses. Next, for each neuron, we quantified the duration of the inhibitory response by measuring the period when the firing rate was below 0.75 x the intrinsic firing rate for at least two consecutive bins. To quantify the relative contribution of AHP currents versus GABAergic synaptic transmission to the inhibitory response, we ran simulations of the model with and without inhibitory synapses. We consider the relative contribution of AHP currents to be inhibitory response duration without inhibitory synapses divided by the duration of inhibition in the intact model. For quantifying relative contribution of GABA synapses, we calculated the difference in inhibition duration between the models with and without inhibitory synapses and then divided that by the duration of inhibition in the model with synapses. For the short train protocol, a line was fit to the peak magnitude of the short latency excitatory responses evoked by each pulse in the stimulus train and the slope was estimated (peak excitatiory response (Hz) = m* time to peak (ms) + c). To assess the variation of temporal response with cortical depth, stimulation was delivered in L2/3, L4 and L6 for a subset of simulations, and recordings were made from neurons within a 150 μm radius around the stimulating electrode.

2.4. ICMS protocols

We tested three ICMS protocols: single pulse, paired pulse, and short trains (Fig. 1D). For single pulse and paired pulse protocols, ICMS was delivered at a repetition frequency of 2 Hz. The total simulation time was 5 s and with a repetition frequency of 2 Hz, this resulted in a total of 10 ICMS trials. For a subset of simulations, single pulse was delivered at repetition rates of 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 2 Hz. The total simulation time for each repetition rate was adjusted to get a total of 10 ICMS trials. For the short train protocol, ICMS was delivered at a repetition frequency of 1 Hz. The total simulation time was 10 s and with a repetition frequency of 1 Hz, this resulted in a total of 10 ICMS trials.

All stimuli were biphasic pulses (cathodic first) with a fixed width of 200 μs/phase and an interphase interval of 50 μs. To assess the effect of pulse type and width on the temporal response, cathodic first and anodic first biphasic pulse types at widths of 100–400 μs/phase were used in a subset of simulations. The single pulse was delivered at four clinically relevant intensities (15, 30, 50 and 100 μA) [4]. The depth-dependent excitation thresholds from the model were compared to published depth-dependent detection thresholds from NHP studies (Figs. S7-S8) [35,36]. Single pulse responses were also quantified at different GABA-B/GABA-A () synaptic strength ratios (0.2–1 in steps of 0.2). For some simulations, responses were quantified with excitatory and inhibitory synapses turned off by setting the synaptic conductances to zero (i.e., g_syn = 0 nS). For the paired pulse protocol, we quantified the response to five different interpulse intervals between the conditioning pulse and test pulse (10, 20, 25, 50 and 100 m s) at each stimulus intensity mentioned above. The timing of the test pulse always fell within the period of the prolonged inhibition. For the short train protocol, ICMS intensity was fixed at 50 μA, the frequency of pulses within the train was varied to include two low (20, 50 Hz) and two high frequencies (100, 200 Hz), and the duration of the short stimulus train was 200 m s. The duration of the short stimulus train was set to match those typically used in preclinical and clinical studies to induce sensory percepts [4,7,37].

2.5. Biomimetic ICMS trains

Biomimetic ICMS trains are intended to evoke neural activity in somatosensory cortex that mimics that evoked by sensory inputs such as tactile stimuli [38]. We tested biomimetic ICMS trains intended to mimic neural activity evoked by mechanical indentations applied onto the fingerpads of digits [39]. The mechanical stimulus consisted of 1 s long trapezoidal indentations delivered at a rate of 10 mm/s and depths ranging from 25 to 2000 μm (Fig. 10A). The somatosensory cortex is known to encode contact transients rather than the static contact [39], and thus ICMS trains were linearly mapped from the derivative of the indentation. The biomimetic ICMS trains consisted of five patterns with onset/offset phase durations of 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 m s (Fig. 10A). The onset/offset phases comprised cathodic first biphasic pulses with a fixed width of 200 μs/phase, interphase interval of 50 μs, frequency of 300 Hz and an amplitude of 50 μA.

2.6. Modeling ICMS

The stimulating tip of the electrode was approximated as a point current source [38,40]. Extracellular potentials due to the point current source in each compartment () of each model cortical neuron () were computed using the equation,

where is the stimulating current, is the distance from the stimulating electrode tip to each compartment of the model cortical neuron, and is the isotropic and homogeneous conductivity of the extracellular medium (0.3 S/m) [41]. All neurons that had a neural element (dendritic, somatic or axonal compartments) within 15 μm of the electrode tip were excluded from the analyses since estimation using a point source would be inaccurate for such close distances without considering the 3D geometry of the microelectrode [40].

Simulations were implemented in NEURON 7.7 with equations solved using the backward Euler method with a time step of 0.025 m s [42]. The values of were coupled to each neuronal compartment using the mechanism [42]. The simulation was parallelized by distributing the total number of neurons (6410) across 50 processors in a round-robin fashion (128 neurons/processor) [43]. The code for the model required to replicate the results will be available on ModelDB post-publication.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were used to infer the effects of ICMS intensity on the duration of the inhibitory response. First, we tested the assumption of normality of inhibition duration at each ICMS intensity using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Inhibition duration data were not normally distributed. Therefore, statistical inferences about the effect of ICMS intensity on inhibition duration were made using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When the omnibus test statistic revealed significance at p < 0.05, we performed Dunn-Sidak’s test for post hoc paired comparisons between individual ICMS intensities [44]. Similar tests were used to infer the effects of ICMS frequency on the slope of the excitatory response. Further, one sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine if the median slope was significantly different from zero. All statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA).

3. Results

3.1. Temporal response to single pulse ICMS

We quantified the response of model L5 cortical neurons to single pulse ICMS across different stimulation intensities, ratios of inhibitory synaptic conductances, , pulse types and pulse widths. The response to single pulse ICMS included short latency excitation followed by a period of inhibition (Fig. 3). ICMS in L2/3, L4, or L6 generated similar excitation-inhibition responses in model L2/3 PC, L4 LBC and L6 PC, respectively, as in L5 (Figs. S9-S11), and both responses were observed for all stimulus strengths. The temporal responses evoked by ICMS were similar whether the intrinsic activity was generated by dc current injection into the soma or via synaptic inputs (Figs. 3 and 4, S12, S13). The model neurons did not exhibit the post-inhibitory rebound excitation seen in experimental responses to ICMS at high intensities/frequencies (Figs. 3 and 4; see Discussion).

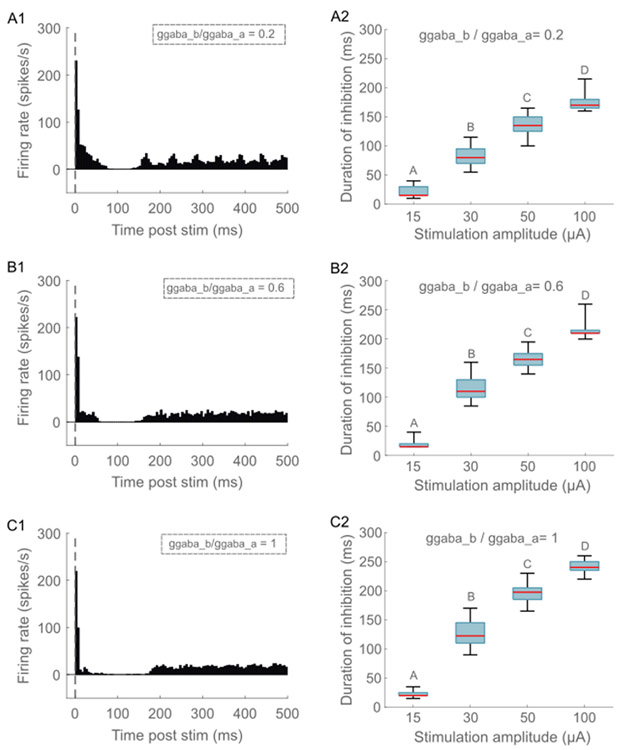

Fig. 4.

Model neuron responses to ICMS for different levels of GABA-B synaptic strength. PSTH response to ICMS at 30 μA and ratio of (A1) 0.2, (B1) 0.6, and (C1) 1. The response was averaged across 34 L5 PCs with somas located within 150 μm from the stimulation electrode. The intrinsic activity was generated by injecting 1.3 nA into the soma of neurons. A bin width of 5 m s was used to bin spike times. Duration of long-lasting inhibitory response as a function of ICMS amplitude for ratio of (A2) 0.2, (B2) 0.6, (C2) 1. Stimulation intensities that do not share the same letter are significantly different (p < 0.05, Dunn/Sidak method). For each box, the central mark indicates the median duration across neurons, the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range. The duration of inhibition was shorter for weaker GABA-B synapses compared to stronger synapses. Further, the duration of inhibition increased with stimulation intensity.

The strength of the short latency excitatory response increased with the intensity of stimulation for L2/3 and L5 PC (Fig. S14A), and the duration of the inhibitory response increased with the intensity of stimulation across all cell types (Fig. S14B). The strength of the excitatory response did not increase with intensity for L4 LBC and L6 PC due to their higher thresholds compared to L2/3 PC and L5 PC (Fig. S14A). At a ratio of 0.6, the median inhibition duration across neurons in response to 15 μA ICMS was ~10 m s and increased to ~200 m s at 100 μA (Fig. 4 B2). Stimulus intensity exerted a significant effect on inhibition duration (, p = 10−27, Kruskal – Wallis ANOVA, χ2(3) = 126.65), and post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference in inhibition duration between all stimulation intensities (Fig 4, p < 0.05, Dunn – Sidak method). The strength of the short latency excitatory response did not change substantially with different ratios (Fig. 4 A1, B1, C1), but the duration of the inhibitory component increased with ratio (Fig. 4). For example, at a stimulus intensity of 30 μA, the median inhibition duration at was ~85 m s compared to an inhibition duration of ~125 m s at (Fig. 4).

We computed the correlation between the peak magnitude of excitatory response and the distance of soma from the stimulating electrode for the L5 PC within 150 μm from the stimulation electrode (Fig. S15). There was a strong negative correlation between the peak strength of the excitatory response and the distance of soma from the stimulating electrode at the lower stimulation intensities (Figs. S15A, B, C), but this correlation declined at the higher stimulation intensities due to the maximal activation of all neurons within the recording volume (Fig. S15D).

We quantified the temporal response of model L5 neurons to different pulse polarities and phase widths (Fig. S16). The strength of the excitatory response increased with pulse width for the cathodic-first biphasic pulses (Fig S16G). Further, the strength of the excitatory response was larger for cathodic-first biphasic pulses compared to the anodic-first pulses (Fig. S16G). Similarly, the duration of inhibitory response increased with pulse width for both pulse polarities, and the duration was longer for cathodic-first than anodic-first pulses (Fig. S16H).

After the stimulation generated excitatory-inhibitory response, the model neurons returned to the ~20 Hz regular firing baseline activity generated by dc current injection into soma (Fig. 3, S17). However, the timing of return to the baseline activity for each neuron varied based on the stimulation intensity and ratio. At lower stimulation intensities, variability in the timing of return across stimulation trials and neurons desynchronized the 20 Hz firing when averaging activity across neurons (Fig. 3C and D). The reduced variability in response across stimulation trials and neurons at the higher stimulation intensities (due to the strong effect of stimulation) resulted in a synchronized return to baseline across neurons (Fig. 3E and F). Further, the synchronization of the post-inhibitory 20 Hz firing activity across neurons was stronger at lower ratios compared to higher ratios (Fig. S18). Baseline activity generated through synaptic activation of L5 PC using 20 Hz Poisson spike trains caused a unique irregular firing pattern at a mean rate of ~20 Hz in each model neuron (Fig S12). This desynchronized the post-inhibitory activity across neurons for all stimulation intensities and ratios (Figs. S12 and S13).

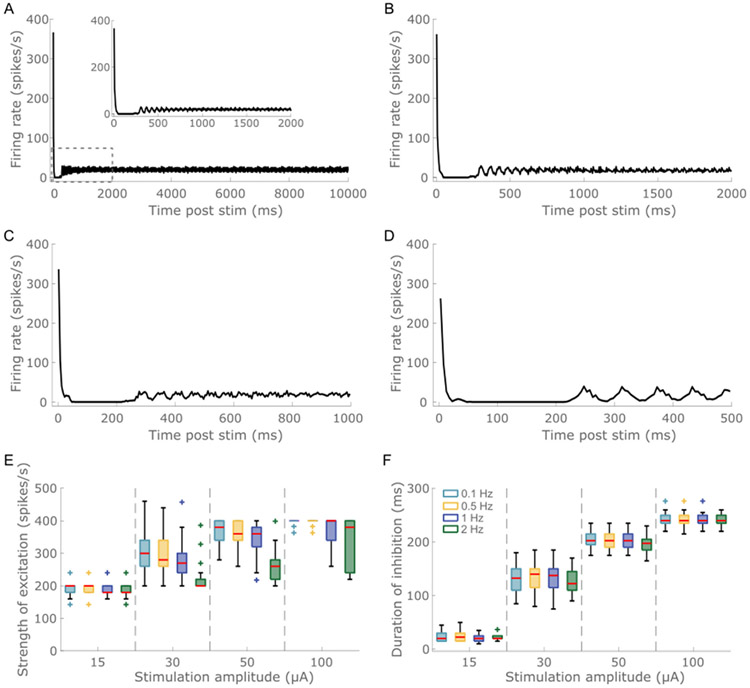

To investigate the effects of the dynamic response evoked by one pulse on the responses evoked by subsequent pulses, we quantified the ICMS-evoked neural activity with a single pulse delivered at different repetition rates −0.1, 0.5, 1 and 2 Hz (Fig. 5A, B, C, D). The strength of the excitatory response decreased marginally at repetition rates of 1 and 2 Hz compared to 0.1 and 0.5 Hz due to carry-over effects (i.e., GABAergic and AHP currents) generated by the previous pulse (Fig. 5A, B, C, D, E). Further, the increase in the strength of the excitatory response with stimulation intensity was less prominent at 2 Hz compared to 0.1, 0.5 and 1 Hz (Fig. 5E). This was again due to the increased carry-over effects at 2 Hz compared to lower frequencies. The strength of the excitatory response reached a steady state only at 0.5 Hz (Fig. 5E), indicating that the response generated by the present pulse was independent of the responses generated by previous pulses only at stimulation frequencies of ≤0.5 Hz. The duration of the inhibitory response remained comparable across all repetition rates (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

Model neuron response to single pulse ICMS delivered at different repetition rates. Stimulus triggered response to 50 μA ICMS pulse delivered at (A) 0.1 Hz, (B) 0.5 Hz, (C) 1 Hz and (D) 2 Hz. The inset in panel A shows the response to 0.1 Hz stimulation at a shorter time scale. For each condition, the stimulus triggered response was averaged across 10 pulses. The ratio was set at 1. Refer to Supplementary Fig. S19 for response to 100 μA ICMS pulse at different repetition rates. (E) The peak of the excitatory response as a function of stimulation amplitude across the four repetition rates. (F) Duration of inhibition as a function of stimulation amplitude for the four repetition rates. Each color box represents a different repetition rate: 0.1 Hz (light blue), 0.5 Hz (yellow), 1 Hz (dark blue), 2 Hz (green). For each box, the central mark indicates the median slope across neurons, the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the plus signs indicate outliers.

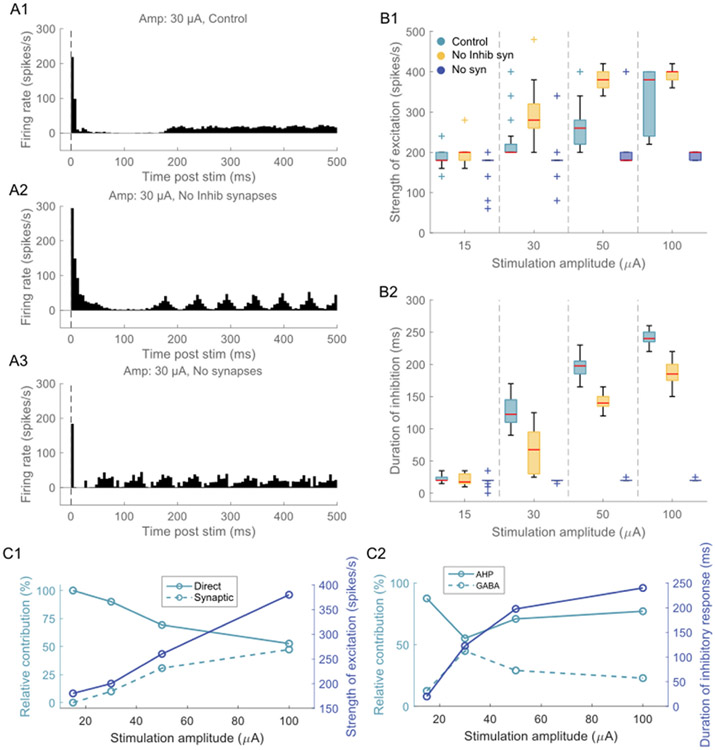

Next, we assessed whether the inhibitory response in the model neurons resulted from cellular mechanisms (afterhyperpolarization (AHP) currents) and/or synaptic mechanisms (GABA synapses and/or short-term depression). We ruled out the possibility of short-term depression because the inhibition duration across repetition rates remained consistent, indicating a change in excitatory synaptic conductance over time does not affect the inhibitory response (Fig. 5F). Removing inhibitory synaptic input increased the excitability of the model neurons, thereby increasing the strength of the short latency excitatory response compared to the control (with inhibitory synapses) condition (Fig. 6A1, A2, B1). Despite the lack of inhibitory synapses, the excitatory response was followed by a strong inhibitory response due to long-lasting AHP currents including calcium- and sodium-dependent potassium currents (Fig. 6A1, A2). However, the duration of the inhibitory component was shorter with inhibitory synapses off than in the control condition (Fig. 6B2). Further, when both excitatory and inhibitory synapses were turned off, the strength of the excitatory response and the duration of the inhibitory response were both substantially reduced compared to the control condition (Fig. 6B1, B2). These results were consistent across ratios (Figs. S20-S21). For stimulation intensities of 15, 50 and 100 μA, AHP currents contributed strongly (>70%) to the inhibitory response compared to GABA synapses (<30%) (Fig. 6C2). However, for the stimulation intensity of 30 μA, both AHP currents and GABA synapses contributed equally to the stimulation induced inhibitory response (Fig. 6C2). The excitatory response resulted mainly due to direct activation for stimulation intensities up to 50 μA, while both direct and synaptic activation contributed equally at 100 μA (Fig. 6C1).

Fig. 6.

Temporal response of model neurons to ICMS at 30 μA and ratio of 1 for (A1) control condition (intact synapses), (A2) without inhibitory synapses, (A3) without inhibitory and excitatory synapses. The vertical dashed line indicates onset of stimulation. The response was averaged across 34 L5 PCs with somas located within 150 μm from the stimulation electrode. A bin width of 5 m s was used to bin spike times. (B1) The peak of the excitatory response as a function of stimulation amplitude for the three conditions. (B2) Duration of inhibition as a function of stimulation amplitude for the three conditions. Each color box represents a different simulation condition: control condition (light blue), without inhibitory synapses (yellow), without inhibitory and excitatory synapses (dark blue). For each box, the central mark indicates the median slope across neurons, the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the plus signs indicate outliers. Refer to Supplementary Figs. S20-S21 for other ratios. (C1) Relative contribution of direct vs. synaptic activation to ICMS-evoked short latency excitatory response. (C2) Relative contribution of afterhyperpolarization (AHP) currents and GABA synapses to ICMS-evoked inhibitory response.

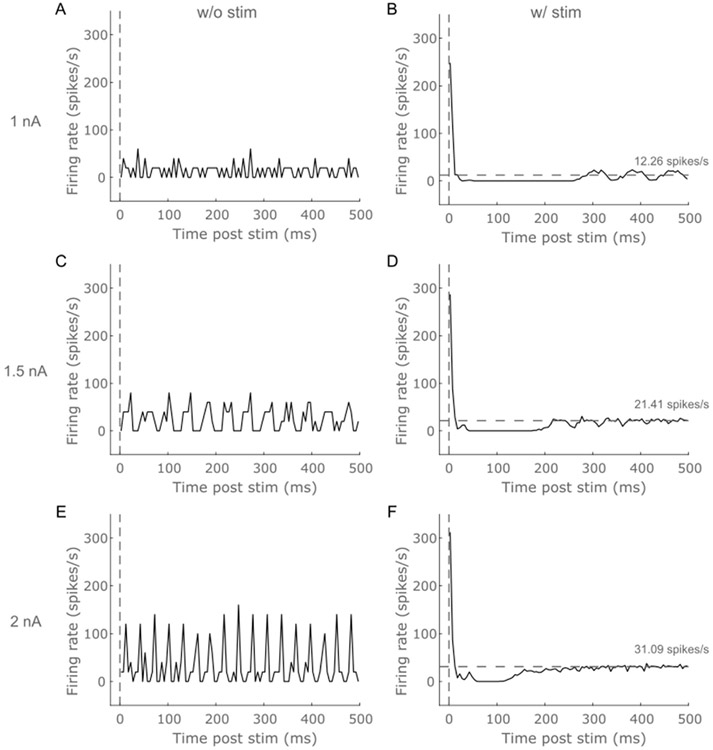

Finally, we assessed the impact of different mean baseline firing rates on the responses evoked by single pulse ICMS. The strength of the excitatory response increased with baseline firing rates, and the duration of the inhibitory response decreased with an increase in the baseline firing (Fig. 7). The mean baseline firing rate of model neurons influenced the synchronicity of the post-inhibitory firing activity between neurons with lower rates strongly synchronizing the firing compared to higher rates (Fig. 7). The strength of the excitatory response and duration of the inhibitory response did not vary substantially with differences in pulse timing relative to the 20 Hz regular firing baseline activity (Fig S22).

Fig. 7.

Effect of different mean intrinsic firing rates on the temporal response to ICMS at 50 μA and ratio of 1. Stimulus triggered response without ICMS for intracellular current injection of (A) 1 nA, (C) 1.5 nA, (E) 2 nA. Stimulus triggered response with ICMS for current injection levels of (B) 1 nA, (D) 1.5 nA, (F) 2 nA. Increasing current injection levels yielded higher mean intrinsic firing rate indicated by the horizontal dashed line. The duration of the inhibitory response is reduced with an increased mean firing rate. Further, the magnitude of the short latency excitatory response increased with the firing rate.

3.2. Temporal response to paired pulse ICMS

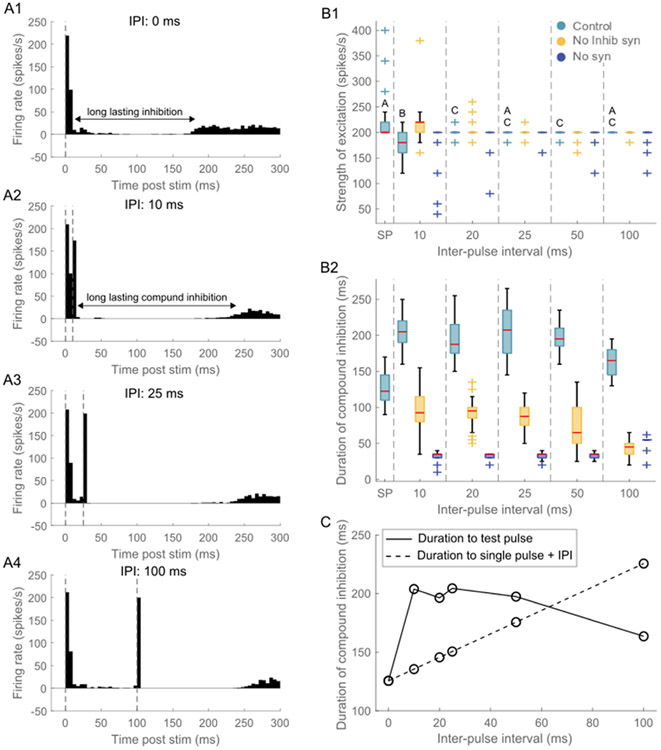

We delivered paired pulse ICMS at different interpulse intervals to investigate the effects of the inhibitory response evoked by the first (conditioning) pulse on the response evoked by the subsequent (test) pulse. The test pulse consistently evoked short latency excitatory and longer latency inhibitory responses across all IPIs (Figs. 8A1-A4). The strength of the excitatory response decreased slightly, in comparison to the response evoked by a single pulse, independent of the IPI (Fig. 8B1). The excitatory response was primarily generated by direct activation and removal of synapses did not have much of an effect on the magnitude of the excitatory response (Fig. 8B1). The duration of the inhibitory response evoked by the test pulse was comparable to that evoked by a single pulse for IPIs >50 m s but for IPI <50 m s, the duration of inhibition evoked by the test pulse was longer than predicted by linear superposition of the duration evoked by a single pulse plus the IPI. (Fig. 8C). Removing the inhibitory synapses made the duration of the compound inhibitory response return to those seen during a single pulse, indicating that GABA-B synapses play a prominent role in the prolongation of compound inhibitory response at IPIs <50 m s (Fig. 8B2). These responses to the paired pulse protocol were consistent across stimulation intensities (Figs. S23-S24) and were similar whether the intrinsic activity was generated by dc current injection into the soma or via synaptic inputs (Fig. 8, S25).

Fig. 8.

Response of model neurons to paired pulse ICMS. (A1) PSTH response to a single (conditioning) pulse applied at ms. Response to paired pulses with conditioning pulse applied at ms and test pulse applied at an inter-pulse interval (IPI) of (A2) 10 m s, (A3) 25 m s, (A4) 100 m s. The vertical dashed lines indicate the timing of the control and test pulses. The paired pulse stimulation was applied at 2 Hz and 30 μA. The conditioning pulse was applied at the same amplitude as the test pulse. Further, the interval of the test pulse was chosen to fall within the duration of the inhibitory response generated by the control pulse. The ratio was set at 1. A bin width of 5 m s was used to bin spike times. (B1) Strength of short latency excitatory response to test pulse at different IPIs for the three conditions. Each color box represents a different simulation condition: control condition (light blue), without inhibitory synapses (yellow), without inhibitory and excitatory synapses (dark blue). SP refers to the single pulse response. For the control condition, IPIs and SP that do not share the same letter are significantly different (p < 0.05, Dunn-Sidak method). For each box, the central mark indicates the median slope across neurons, the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the plus signs indicate outliers. The strength of excitatory response to test pulse decreased marginally compared to a single pulse and this effect was consistent across all stimulation intensities. This decrease can be attributed to the inhibitory effect triggered by the conditioning pulse. (B2) Duration of compound inhibitory response as a function of IPIs across the three simulation conditions. (C) The duration of inhibitory response to test pulse at 30 μA. Solid trace shows the inhibition duration to test pulses, whereas the dashed line indicates the duration predicted by linear superposition of individual inhibitory responses, i.e., duration of inhibition following single pulse + IPI. There was supra-linear addition of individual inhibitory responses for IPIs ≤50 m s and a sub-linear addition for IPIs >50 m s.

3.3. Temporal responses to short trains of ICMS

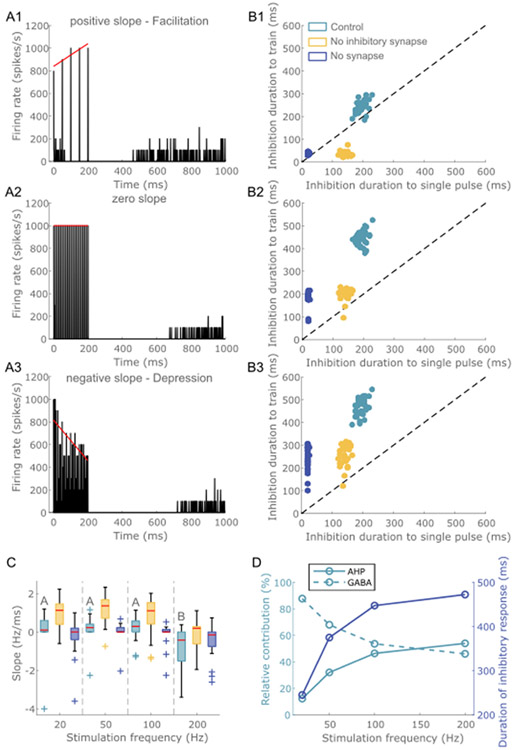

We applied short trains of ICMS, and the responses of model neurons were classified into three types based on the dynamics of the excitatory response during the stimulus train: (1) facilitation – the magnitude of the excitatory response increased during the course of the train (Fig. 9A1), (2) no change in the magnitude of excitatory responses during the train (Fig. 9A2), or (3) depression – the magnitude of the excitatory responses decreased during the train (Fig. 9A3). A line was fit to the peak excitatory response evoked by each pulse, and the slope was computed. Most neurons exhibited a negative slope (depression) at higher stimulus frequencies in contrast to lower frequencies, and the median slope across 34 L5 PC neurons was ~−0.4 Hz/ms at 200 Hz compared to ~0.1 Hz/ms at 20 Hz (Fig. 9C). Stimulus frequency exerted a significant effect on the slope (p = 10−9, Kruskal – Wallis ANOVA, χ2 (3) = 42.43), and post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference in slope across stimulation frequencies (Fig 9C, p < 0.05, Dunn – Sidak method). As well, for each stimulus frequency, a one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated that the median slope was significantly different from 0 (20 Hz: Z = 4.5649, p = 4.9981e-06, 50 Hz: Z = 4.5179, p = 6.2454e-06, 100 Hz: Z = 3.0110, p = 0.0026, 200 Hz: Z = −3.8567, p = 1.1494e-04). These results suggest that neurons were better able to follow low stimulation frequencies than higher frequencies. Excitatory synapses mediated the facilitatory effects at low stimulation frequencies, whereas GABA synapses were involved in the depression at higher stimulation frequencies (Fig. 9C). Further, the duration of inhibition at the end of the stimulus train at higher frequencies was longer than the duration of inhibition evoked by a single pulse (Fig. 9B1-B3). GABA synapses contributed strongly to the inhibitory response at low stimulus frequencies, while at higher frequencies (≥100 Hz) both AHP currents and GABA synapses contributed equally (Fig. 9D). These effects were consistent across ratios (Fig. S26).

Fig. 9.

Model response to short trains of ICMS at different frequencies. A line was fit to the peak short latency excitatory responses evoked by each pulse within the stimulus train. Model neurons exhibited three types of response dynamics: (A1) Positive slope - facilitation of the short latency excitatory response with the progression of the ICMS train, (A2) Zero slope – no change in the excitatory response during the train, (A3) Negative slope – decline of the short latency excitatory response with the progression of the ICMS train. A bin width of 1 m s was used to bin spike times for panels in A. The ratio was set at 1. Correlation of inhibition duration at the end of the train with inhibition duration following single pulse stimulation for short trains at frequencies (B1) 20 Hz, (B2) 100 Hz, (B3) 200 Hz. Each dot represents the duration of inhibition of each 34 L5 PCs across three conditions: control condition (light blue), without inhibitory synapses (yellow), without inhibitory and excitatory synapses (dark gray). The inhibition duration at the end of the ICMS train was longer than the duration following a single pulse for trains at higher stimulus frequencies compared to lower ones. (C) The slope of the line fit to the excitatory response as a function of stimulation frequency. For the control condition, stimulation frequencies that do not share the same letter are significantly different (p < 0.05, Dunn-Sidak method). For each box, the central mark indicates the median slope across neurons, the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the plus signs indicate outliers. Each color box represents a different simulation condition: control condition (light blue), without inhibitory synapses (yellow), and without inhibitory and excitatory synapses (dark blue). Most neurons exhibited a negative slope at higher stimulation frequencies. Refer to Supplementary Fig. S26 for other ratios. (D) Relative contribution of AHP currents and GABA synaptic transmission to ICMS-induced inhibitory response.

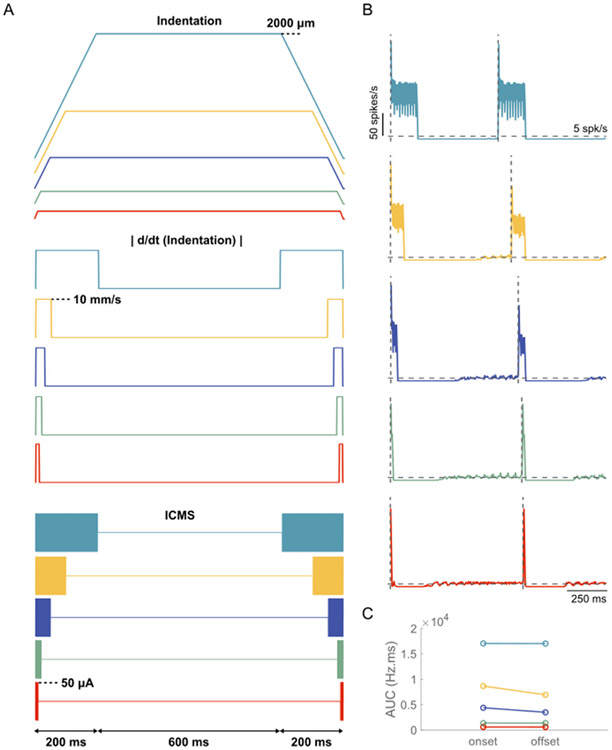

3.4. Temporal responses to biomimetic ICMS trains

Biomimetic pulse trains, comprising an onset phase, a plateau phase, and an offset phase, are intended to mimic the neural activity evoked during natural physiological inputs (Fig. 10A). We quantified the temporal response to biomimetic ICMS trains to determine whether they reliably evoke neural activity matching those evoked by mechanical (tactile) stimuli (Fig. 10A). The biomimetic trains reliably evoked a series of short latency excitatory responses during the stimulus onset and offset (Fig. 10B), and the area under the curve of the response did not change substantially between the onset and offset phases (Fig. 10C). The inhibition duration evoked at the end of the offset phase was similar to the duration at the end of the onset phase across all tested biomimetic stimulus trains (Fig. 10B). The responses evoked by biomimetic ICMS trains were similar whether the intrinsic activity was generated by dc current injection into the soma or via synaptic inputs (Fig. 10, S27).

Fig. 10.

Temporal response of model neurons to biomimetic ICMS trains. (A) 1-s long trapezoidal indentations delivered at a rate of 10 mm/s and depths ranging from 25 to 2000 μm. Absolute value of the first derivative of trapezoidal indentations . ICMS trains linearly mapped from . The onset/offset phases comprised cathodic first biphasic pulses with a fixed width of 200 μs/phase, interphase interval of 50 μs, frequency of 300 Hz and an amplitude of 50 μA. The temporal response of model neurons to biomimetic ICMS trains with onset/offset phase duration of (B1) 200 m s, (B2) 100 m s, (B3) 50 m s, (B4) 20 m s, (B5) 10 m s. The ratio was set at 1. The horizontal dashed line indicates the mean firing rate (~5 Hz) and vertical dashed line indicates onset of stimulation phases. A bin width of 5 m s was used to bin spike times. (C) Comparison of area under the curve of the responses during the onset and offset phases of the biomimetic ICMS trains.

4. Discussion

We implemented a computational model of a cortical column to decipher the mechanisms underlying the temporal responses to various ICMS protocols. Single pulse ICMS evoked a short latency excitatory response followed by a period of inhibition, and the strength of the excitatory response and the duration of inhibition increased with stimulation intensity. The excitatory response was primarily generated by direct activation at the lower stimulation intensities, while both direct and synaptic activation contributed equally at the higher stimulation intensities, and both AHP currents and GABAergic synaptic transmission were prominent in generating the inhibitory response. GABAergic synaptic transmission generated a strong inhibitory response that lasted for several hundred milliseconds post-stimulation and was primarily responsible for the rapid decline of the short latency excitatory response during stimulus trains at higher frequencies. Finally, biomimetic stimulus trains evoked similar responses across the onset and offset phases despite the effect of GABAergic inhibition.

4.1. Model validation

The temporal response to ICMS has been recorded and characterized in the sensorimotor areas of both rodents and non-human primates [1,11,12,14,15,18,22]. Butovas and colleagues observed short latency excitation and long-lasting inhibition that were linked across stimulation intensities (0.8–4 nC) and rebound excitation occurred at higher stimulation intensities (>2 nC) [1]. Similarly, our model neurons exhibited short latency excitation and long-duration inhibition, but none of the stimulation intensities evoked rebound excitation. Several studies replicated the results of Butovas and Schwarz and observed an increase in the duration of inhibition with stimulus amplitude [11,12,20]. We found a significant increase in inhibition duration with the stimulation intensity. Butovas et al. conducted follow up studies using pharmacological blockers to probe the neural origin of the long-duration inhibitory response [23]. The inhibitory response to ICMS was reduced following block of GABA-B receptors, and our finding that the duration of the inhibitory response in model neurons increased with the GABA-B/GABA-A synaptic strength ratio is consistent with these results. Other cortical stimulation modalities, including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), also evoke a triphasic temporal response pattern similar to that evoked by ICMS [16,17,45], and the stimulus intensity-dependent effects of TMS on the response components are similar to the intensity-dependent effects of ICMS [16,17,45]. However, there are some subtle differences in the onset latency of the excitatory response to TMS (~10 m s) compared to ICMS (within a few ms). This difference might be due to the variation in the electric fields generated by TMS and ICMS, and any attempts to model the temporal response to TMS using our modeling pipeline must consider the electric fields induced by TMS rather than ICMS.

In addition to the response to single pulse ICMS, Butovas and Schwarz quantified the response to paired pulses at IPIs of 25, 50 and 100 m s [1]. They found a supralinear addition of inhibition duration for the IPI of 25 m s and sublinear addition for the 50 and 100 m s IPIs. This matched with our findings where we observed a supra-linear addition for IPIs up to 50 m s and a sub-linear addition for IPIs >50 m s. The strength of the excitatory response to the test pulse at the various IPIs did not change substantially compared to the single pulse in the Butovas and Schwarz study, which was consistent with our findings.

Butovas and Schwarz also quantified the response to short stimulus trains at frequencies 5–40 Hz [1]. They found that low stimulation frequencies evoked repetitive excitatory responses over a background of inhibition, and we observed the same pattern in the model. In addition, we found that the excitatory response of most model neurons declined during the train at higher stimulus frequencies, similar to the results of recent studies [12,46]. As well, Sombeck et al. observed that the duration of inhibition at the end of the train was longer than the inhibition following a single pulse for stimulus trains at higher frequencies than at lower frequencies, consistent with our results [12].

4.2. Neural mechanisms of temporal response to single pulse ICMS

ICMS preferentially activates the axonal terminals near the stimulating microelectrode at the stimulus threshold [28,29,47]. The neural origin of the short-latency excitation response includes activation through antidromic (direct) and orthodromic (synaptic) contributions from activated axonal terminations. The excitatory response in the model neurons was predominantly generated by direct activation at lower stimulation intensities (15, 30 and 50 μA). However, both direct and synaptic activation contributed equally to the excitatory response at 100 μA. There are several potential contributors to the inhibitory response including AHP currents, GABAergic synaptic transmission, and short-term synaptic depression [48,49]. We ruled out the possibility of short-term depression of excitatory neurotransmitters because the inhibitory response was comparable across repetition rates, indicating that the change in excitatory synaptic conductance over time had a limited effect on the inhibitory response. There was a non-monotonic relationship between the relative contributions of AHP currents and GABA synaptic transmission across stimulus intensities. The AHP currents mainly contributed to the inhibitory response at stimulus intensities 15, 50 and 100 μA, while AHP currents and GABA synaptic transmissions contributed equally to the inhibitory response at 30 μA. The strength of the excitatory response (which generates the AHP currents) did not change much between stimulation intensities of 15 and 30 μA (refer Fig. 6B1). However, the space constant of GABA synaptic activation by ICMS tripled from 50 μm at 15 μA to 150 μm at 30 μA. This is why both AHP and GABA synaptic transmissions contributed equally to the inhibitory response at 30 μA. However, the strength of the excitatory response increased with stimulation intensity for 50 and 100 μA, thereby AHP currents dominated the generation of the inhibitory response at those intensities. Our findings on the neural origin of the temporal response to ICMS are expected to apply to the other cortical stimulation modalities, such as TMS, that generate similar neural responses to stimulation.

4.3. Relationship between ICMS-induced neural activity and ICMS-induced sensory perception

It is not clear what role each component of the temporal response to ICMS contributes to induced behavioral effects or perception. The intensity of the tactile percepts evoked by continuous ICMS declined more rapidly (tens of seconds) at higher stimulus frequencies than at lower ones [50]. Similarly, high frequency ICMS delivered at 100–200 Hz led the induced phosphenes to disappear within several hundred milliseconds [51]. The model suggests that this effect during continuous high frequency stimulation is due to the decline of the short latency excitatory response, which was more pronounced at higher frequencies. The literature includes several speculations as to why high frequency continuous ICMS may not be able to evoke a consistent response including contributions of synaptic depletion of neurotransmitters, strong hyperpolarizing currents in the soma preventing further spiking activity, small diameter (less myelination) of axons of cortical neurons, and GABA synaptic transmission [52-55]. The decline in activity at higher frequencies occurred in the model largely due to GABAergic synaptic transmission, and the inhibition lasted for several hundred milliseconds after stimulation.

5. Study limitations

Our cortical column model comprising neurons with realistic morphology and synapses is the most advanced modeling work to date to study the temporal effects of ICMS but nonetheless has some important limitations including modeling only a single column, lack of horizontal connections between columns, no connectivity between neurons, missing neural types, and lack of glia or other support cells that may contribute to the response. Despite these limitations, we replicated the major components seen in the experimentally measured temporal response to single pulse ICMS. However, we did not observe the post-inhibitory rebound excitatory response in the model neurons typically seen in the experimental response at the higher stimulation intensities and frequencies. The thalamus, which was not included in our model, appears to play a prominent role in generating the rebound response [56-58]. Stimulating the cortex causes brief excitation followed by inhibition in the cortical neurons [57]. This excitation-inhibition response propagates from the cortex to the thalamus [57]. Rebound excitation is generated in the thalamus in the post-inhibitory phase due to the activation of the T-type Ca2+ channels and subsequently propagates back to the cortex [57,58]. Thalamic ablation suppressed the rebound excitation response in the cortical neurons [56]. Thus, the absence of the thalamus and corticothalamic and thalamocortical connections may explain the lack of rebound excitation in model neurons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Joseph Sombeck and Aman Aberra for helpful discussions on this work. We acknowledge technical support from the Duke Compute Cluster. We also thank Bradley Barth for his assistance in preparing the figures.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (R01 NS095251, U01 NS126052).

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Karthik Kumaravelu: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Warren M. Grill: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2024.03.012.

References

- [1].Butovas S, Schwarz C. Spatiotemporal effects of microstimulation in rat neocortex: a parametric study using multielectrode recordings. J Neurophysiol 2003;90(5): 3024–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Logothetis NK, et al. The effects of electrical microstimulation on cortical signal propagation. Nat Neurosci 2010;13(10):1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shelchkova ND, et al. Microstimulation of human somatosensory cortex evokes task-dependent, spatially patterned responses in motor cortex. Nat Commun 2023; 14(1):7270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Flesher SN, et al. Intracortical microstimulation of human somatosensory cortex. Sci Transl Med 2016;8(361):361ra141. 361ra141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brindley GS, Lewin WS. The sensations produced by electrical stimulation of the visual cortex. J Physiol 1968;196(2):479–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rousche PJ, Normann RA. Chronic intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) of cat sensory cortex using the Utah Intracortical Electrode Array. IEEE Trans Rehabil Eng 1999;7(1):56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Salas MA, et al. Proprioceptive and cutaneous sensations in humans elicited by intracortical microstimulation. Elife 2018;7:e32904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tabot GA, et al. Restoring the sense of touch with a prosthetic hand through a brain interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110(45): 18279–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Romo R, et al. Somatosensory discrimination based on cortical microstimulation. Nature 1998;392(6674):387–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hughes CL, et al. Perception of microstimulation frequency in human somatosensory cortex. Elife 2021;10:e65128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hao Y, Riehle A, Brochier TG. Mapping horizontal spread of activity in monkey motor cortex using single pulse microstimulation. Front Neural Circ 2016;10:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sombeck JT, et al. Characterizing the short-latency evoked response to intracortical microstimulation across a multi-electrode array. J Neural Eng 2022; 19(2):026044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Klink PC, et al. Distinct feedforward and feedback effects of microstimulation in visual cortex reveal neural mechanisms of texture segregation. Neuron 2017;95(1):209–220. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kraskov A, et al. Ventral premotor–motor cortex interactions in the macaque monkey during grasp: response of single neurons to intracortical microstimulation. J Neurosci 2011;31(24):8812–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kunori N, Kajiwara R, Takashima I. Voltage-sensitive dye imaging of primary motor cortex activity produced by ventral tegmental area stimulation. J Neurosci 2014;34(26):8894–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li B, et al. Lifting the veil on the dynamics of neuronal activities evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Elife 2017;6:e30552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Romero MC, et al. Neural effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation at the single-cell level. Nat Commun 2019;10(1):2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Margalit SN, Slovin H. Spatio-temporal characteristics of population responses evoked by microstimulation in the barrel cortex. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fehervari TD, et al. In vivo voltage-sensitive dye study of lateral spreading of cortical activity in mouse primary visual cortex induced by a current impulse. PLoS One 2015;10(7):e0133853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yun R, et al. Responses of cortical neurons to intracortical microstimulation in awake primates, eneuro 2023; 10(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Allison-Walker T, et al. Microstimulation-evoked neural responses in visual cortex are depth dependent. Brain Stimul 2021;14(4):741–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Butovas S, Schwarz C. Local neuronal responses to intracortical microstimulation in rats’ barrel cortex are dependent on behavioral context. Front Behav Neurosci 2022;16:805178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Butovas S, et al. Effects of electrically coupled inhibitory networks on local neuronal responses to intracortical microstimulation. J Neurophysiol 2006;96(3):1227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dadarlat MC, Sun YJ, Stryker MP. Activity-dependent recruitment of inhibition and excitation in the awake mammalian cortex during electrical stimulation. Neuron 2023;112(5):821–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dadarlat MC, Sun Y, Stryker MP. Widespread activation of awake mouse cortex by electrical stimulation. 2019 9th international IEEE/EMBS conference on neural engineering (NER). IEEE; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hughes C, Kozai T. Dynamic amplitude modulation of microstimulation evokes biomimetic onset and offset transients and reduces depression of evoked calcium responses in sensory cortices. Brain Stimul 2023;16(3):939–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Markram H, et al. Reconstruction and simulation of neocortical microcircuitry. Cell 2015;163(2):456–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Aberra AS, Peterchev AV, Grill WM. Biophysically realistic neuron models for simulation of cortical stimulation. J Neural Eng 2018;15(6): 066023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kumaravelu K, et al. Stoney vs. Histed: quantifying the spatial effects of intracortical microstimulation. Brain Stimul 2022;15(1):14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Firmin L, et al. Axon diameters and conduction velocities in the macaque pyramidal tract. J Neurophysiol 2014; 112(6):1229–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].London BM, Miller LE. Responses of somatosensory area 2 neurons to actively and passively generated limb movements. J Neurophysiol 2013;109(6):1505–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Balaram P, Kaas JH. Towards a unified scheme of cortical lamination for primary visual cortex across primates: insights from NeuN and VGLUT2 immunoreactivity. Front Neuroanat 2014;8:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bower KL, McIntyre CC. Deep brain stimulation of terminating axons. Brain Stimul 2020;13(6):1863–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chakraborty D, et al. Neuromodulation of axon terminals. Cerebr Cortex 2018;28(8):2786–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tehovnik EJ, Slocum WM. Depth-dependent detection of microampere currents delivered to monkey V1. Eur J Neurosci 2009;29(7): 1477–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].DeYoe EA, Lewine JD, Doty RW. Laminar variation in threshold for detection of electrical excitation of striate cortex by macaques. J Neurophysiol 2005;94(5):3443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].O’Doherty JE, et al. Active tactile exploration using a brain–machine–brain interface. Nature 2011;479(7372): 228–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kumaravelu K, et al. A comprehensive model-based framework for optimal design of biomimetic patterns of electrical stimulation for prosthetic sensation. J Neural Eng 2020;17(4):046045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Callier T, Suresh AK, Bensmaia SJ. Neural coding of contact events in somatosensory cortex. Cerebr Cortex 2019;29(11):4613–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].McIntyre CC, Grill WM. Finite element analysis of the current-density and electric field generated by metal microelectrodes. Ann Biomed Eng 2001;29(3):227–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ranck JB. Specific impedance of rabbit cerebral cortex. Exp Neurol 1963;7(2): 144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hines ML, Carnevale NT. NEURON: a tool for neuroscientists. Neuroscientist 2001; 7(2): 123–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hines ML, Carnevale NT. Translating network models to parallel hardware in NEURON. J Neurosci Methods 2008;169(2):425–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Neter J, et al. Applied linear statistical models. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Moliadze V, et al. Effect of transcranial magnetic stimulation on single-unit activity in the cat primary visual cortex. J Physiol 2003;553(2):665–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Michelson NJ, et al. Calcium activation of cortical neurons by continuous electrical stimulation: frequency dependence, temporal fidelity, and activation density. J Neurosci Res 2019;97(5):620–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rattay F, Wenger C. Which elements of the mammalian central nervous system are excited by low current stimulation with microelectrodes? Neuroscience 2010;170(2):399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Gerstner W, et al. Neuronal dynamics: from single neurons to networks and models of cognition. Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sanchez-Vives MV, et al. GABAB receptors: modulation of thalamocortical dynamics and synaptic plasticity. Neuroscience 2021;456:131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hughes CL, Flesher SN, Gaunt RA. Effects of stimulus pulse rate on somatosensory adaptation in the human cortex. Brain Stimul 2022;15(4):987–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Schmidt EM, et al. Feasibility of a visual prosthesis for the blind based on intracortical micro stimulation of the visual cortex. Brain 1996;119(2):507–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Anderson TR, et al. Selective attenuation of afferent synaptic transmission as a mechanism of thalamic deep brain stimulation-induced tremor arrest. J Neurosci 2006;26(3):841–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Iremonger KJ, et al. Cellular mechanisms preventing sustained activation of cortex during subcortical high frequency stimulation. J Neurophysiol 2006;96(2):613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Fukuda S, et al. Use-dependent inactivation of the mouse visual cortex in response to microstimulation train. 2022 E-health and bioengineering conference (EHB). IEEE; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chomiak T, Hu B. Axonal and somatic filtering of antidromically evoked cortical excitation by simulated deep brain stimulation in rat brain. J Physiol 2007;579(2):403–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Grenier F, Timofeev I, Steriade M. Leading role of thalamic over cortical neurons during postinhibitory rebound excitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95(23):13929–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Claar LD, et al. Cortico-thalamo-cortical interactions modulate electrically evoked EEG responses in mice. Elife 2023;12:RP84630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Russo S, et al. Thalamic feedback shapes brain responses evoked by cortical stimulation in mice and humans. bioRxiv; 2024. p. 2024. 01. 31.578243. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.