Summary

In face-to-face interactions with infants, human adults exhibit a species-specific communicative signal. Adults present a distinctive social ensemble: They use infant-directed speech (parentese), respond contingently to infants’ actions and vocalizations, and react positively through mutual eye-gaze and smiling. Studies suggest that this social ensemble is essential for language learning. Our hypothesis is that the social ensemble attracts attentional systems to speech and that sensorimotor systems prepare infants to respond vocally, both of which advance language learning. Using infant magnetoencephalography (MEG), we measure 5-month-old infants’ neural responses during live verbal face-to-face (F2F) interaction with an adult (social condition), and during a control (nonsocial condition) in which the adult turns away from the infant to speak to another person. Using a longitudinal design, we tested whether infants’ brain responses to these conditions at 5 months of age predicted their language growth at five future time points. Brain areas involved in attention (right hemisphere inferior frontal, right hemisphere superior temporal, right hemisphere inferior parietal) show significantly higher theta activity in the social versus nonsocial condition. Critical to theory, we found that infants’ neural activity in response to F2F interaction in attentional and sensorimotor regions significantly predicted future language development into the third year of life, more than 2.5 years after the initial measurements. We develop a view of early language acquisition that underscores the centrality of the social ensemble, and we offer new insight into the neurobiological components that link infants’ language learning to their early brain functioning during social interaction.

Keywords: Magnetoencephalography (MEG), brain, language development, social interaction, infant, attention, behavior, neuroscience

eTOC Brief

How early social interaction impacts language acquisition is not well understood. Using MEG brain imaging, Bosseler et al. show that 5-month-old infants’ brain responses to social vs. nonsocial interactions predict individual variation in their language skills 2.5 years later, suggesting a potent role for social interaction in language development.

Introduction

Prior to producing their first words, infants learn the sound patterns that distinguish the words used in their native language(s). A sensitive period for phonetic learning occurs between 6 and 12 months of age, during which infants’ initially universal phonetic capacities narrow and become specific to their native language1,2,3,4. Laboratory studies in which infants are experimentally presented with a new language between 9 and 11 months of age reveal that infant learning during this early period requires social interaction5,6. Human infants born in the U.S. to English-speaking parents and exposed to Mandarin Chinese at 9 months of age, during live social interaction, learned speech sounds so rapidly and effectively that they performed equivalently to infants raised in Taiwan and exposed to Mandarin from birth5. Yet control conditions in this experiment showed that no phonetic learning occurred for infants exposed to the same information on the same schedule presented via a standard video screen.

We hypothesize that infants’ neuro-cognitive systems—social attention and sensorimotor processing—which are engaged by adults’ use of the species-specific social ensemble—support language learning. This hypothesis grows out of several lines of research. First, previous work has demonstrated that social attention increases during parent-child social interaction in toddlers7,8, which in turn is correlated with language learning9 (for review see10). Moreover, studies of young children at risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) show that a failure to attend to a social stimulus predicts ASD subtypes11. The degree of disinterest in parents’ speech by toddlers with ASD has been shown to be associated with the degree of autism symptom severity12,13.

Neural sensorimotor system engagement would also be expected to advance language development. In neurobiological research with songbirds, species capable of vocal learning, the social cues provided by an adult bird singing trigger events that aid the encoding of communicative information14. For example, in zebra finch, songbirds that require a social stimulus to learn species-typical song, social cues generated by the tutor bird activate neurons in the midbrain of the baby bird. These neurons release dopamine in a sensorimotor circuit that are shown to enhance the encoding of tutor song representations14. Thus, the social context enhances the initial encoding of the information needed in sensorimotor brain areas to imitate the tutor bird’s song. In humans, sensorimotor brain areas are activated during verbal social interaction with infants15. Hearing speech (but not nonspeech) activates sensorimotor brain areas when adults16,17,18 and infants19,20,21 listen to speech, and the nature and amount of language input from adults has been linked to growth of sensorimotor connections in the young human brain22. Thus, we here hypothesized that adult-infant live face-to-face interaction would enhance activation in infant sensorimotor brain areas and predict future language learning.

The hypothesis tested in the current study is that individual variation in brain activation in areas of the brain related to attention and sensorimotor processing in response to the social ensemble predicts individual variation in language skills up to 2.5 years later. To test this hypothesis, we use infant whole-head magnetoencephalography (MEG) brain imaging to compare typically developing 5-month-old infants’ neural activity during live interaction in a social versus a nonsocial situation (Figure 1), and we link individual differences in infants’ brain response during this interaction to future language growth. Specifically, we examine brain activity elicited during face-to-face social interactions at 5 months of age, prior to the well-documented initial period for phonetic and word learning15, and test its predictive value for children’s developing language skills. We hypothesize that infant attention to face-to-face social verbal interactions, prior to this sensitive period, may prepare infants for language learning when the sensitive period opens.

Figure 1. 5-month-old infant in a MEG brain-imaging device with social vs. nonsocial conditions.

(A) During the social condition, the experimenter, signaled by a green light, interacted with the infant by exhibiting the social ensemble of behaviors.

(B) During the nonsocial condition, the experimenter, signaled by a red light, turned 45 degrees toward an adult sitting out of view of the infant and spoke to them. For each infant, the conditions were presented randomly and separated by at least 7 s, with a minimum of 16 repetitions for each condition per infant. The recording session lasted about 13 min.

A brain-behavior, multi-time point longitudinal test of this type has not been done previously. Prior EEG studies used video rather than live stimuli to examine infants’ brain responses to social stimuli23,24,25, or investigated live sung speech presented noncontingently with infant behavior26. An fNIRS hyperscanning study examined adult-infant interaction, and found positive associations between: (i) turn-taking behavior and adult-infant neural synchrony, and (ii) turn-taking behavior and infant brain maturity and 24-month vocabulary, but did not directly link infants’ brain activity to longitudinally-measured language skills27.

The use of MEG brain imaging technology ensures spatial resolution (< 3 mm) that is superior to EEG, and temporal resolution (< 1 ms) much greater than fNIRS. MEG is safe and noninvasive, and has been maximized for infant testing28.

The experimental procedure entailed a within-subjects design, which included a social condition during which an adult female experimenter engaged the infant by speaking in parentese and reacted warmly and contingently to the infant, as well as a nonsocial condition during which the experimenter turned 45 degrees to speak (using adult-directed ‘standard’ speech29) to an adult who was seated to the infants’ left (out of view of the infant, see Figure 1). Our intention was to capture, as much as possible in a brain-imaging experiment, typical social interactions that infants experience every day in their home environments. In both conditions, the adult spoke naturally, providing both auditory and visual speech stimulation to the infant brain for the same duration.

Following our hypothesis, we focused on brain regions related to attention (right inferior frontal, r-IF; right superior temporal, r-ST; right inferior parietal, r-IP)30,31,32 and those related to speech-motor processing (left inferior frontal, l-IF)33,34, reasoning that differential activation in the social vs. nonsocial condition in these areas would predict infants’ future language skills. Given that infants heard auditory speech by the same adult experimenter speaking in both conditions, we did not expect differential activation to social vs. nonsocial in the auditory speech processing area (left superior temporal, l-ST) or in the left inferior parietal area (l-IP), nor did we expect that activity in these areas would predict future language growth.

We recorded MEG activity as the infant engaged in the social and nonsocial conditions and, in each ROI, measured infants’ oscillatory brain activity in the theta spectral band (4–8 Hz). We focus on the theta frequency band because previous studies in both adults and children implicate theta activity for sustained attention, active learning, cognitive load, and reward35,36,37,38. Moreover, EEG evidence indicates infant theta oscillations increase when processing positive social affect39, when listening to infant-directed speech40, and when viewing social vs. nonsocial videos23, 24.

The critical hypothesis for theory is that, at the level of individual participants, enhanced brain activation during the social condition would positively predict infants’ prospective language skills. For each infant participant (N = 21) we collected longitudinal behavioral measures of productive vocabulary at five sequential three-month intervals from 18 to 30 months of age. Vocabulary was measured using the standard MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (CDI) – Words and Sentences41, a widely used and validated measure of children’s language development. Growth curve models assessed the association between infants’ brain responses and children’s vocabulary growth (see Methods).

Results

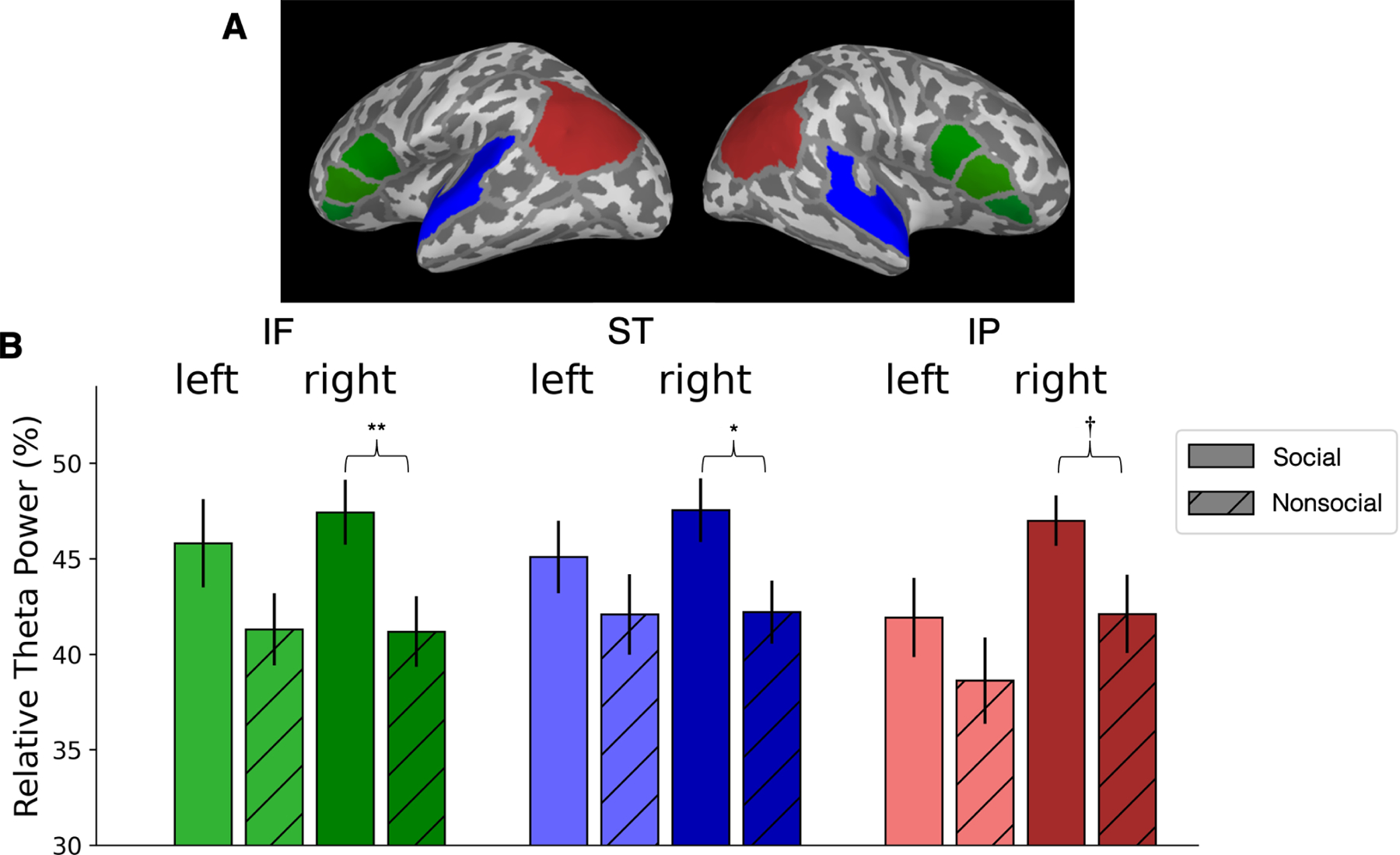

To test our hypothesis, we specified three brain regions of interest (ROIs), and used a priori planned comparisons to test the predicted differences between the social and nonsocial conditions in each ROI, and in each hemisphere, rather than conducting an overall ANOVA42. Figure 2A shows the cortical map of ROIs; and Figure 2B shows the mean relative theta power (RTP) as a function of Condition (social vs. nonsocial), ROI (IF, ST, and IP), and Hemisphere (left, right).

Figure 2. Mean neural activity during social and nonsocial conditions.

(A) Brain map showing regions of interest (ROI): Inferior Frontal (IF-green), Superior Temporal (ST-blue) and Inferior Parietal (IP-red) in the left and right hemispheres.

(B) Mean relative theta power (RTP), as percentage of total power between 0 and 60 Hz, in each ROI for Conditions and Hemispheres. Error bar indicates +/− 1 standard error, ** indicates statistical significance p ≤ 0.01, * indicates p ≤ 0.05, and † indicates trend toward significance p = 0.055, two-tailed paired t-tests.

Planned comparisons showed a significant effect of RTP in the social versus nonsocial condition in r-IF (p = 0.01, t(20) = 2.73, effect size η2 = 0.60), r-ST (p = 0.05, t(20) = 2.05, η2 = 0.45), and a trend toward significance in r-IP (p = 0.055, t(20) = 2.04, η2 = 0.44). Effects in l-IF were not statistically significant (l-IF, p = 0.10). As expected, no effects were observed in l-ST or l-IP (p = 0.26 and p = 0.08, respectively).

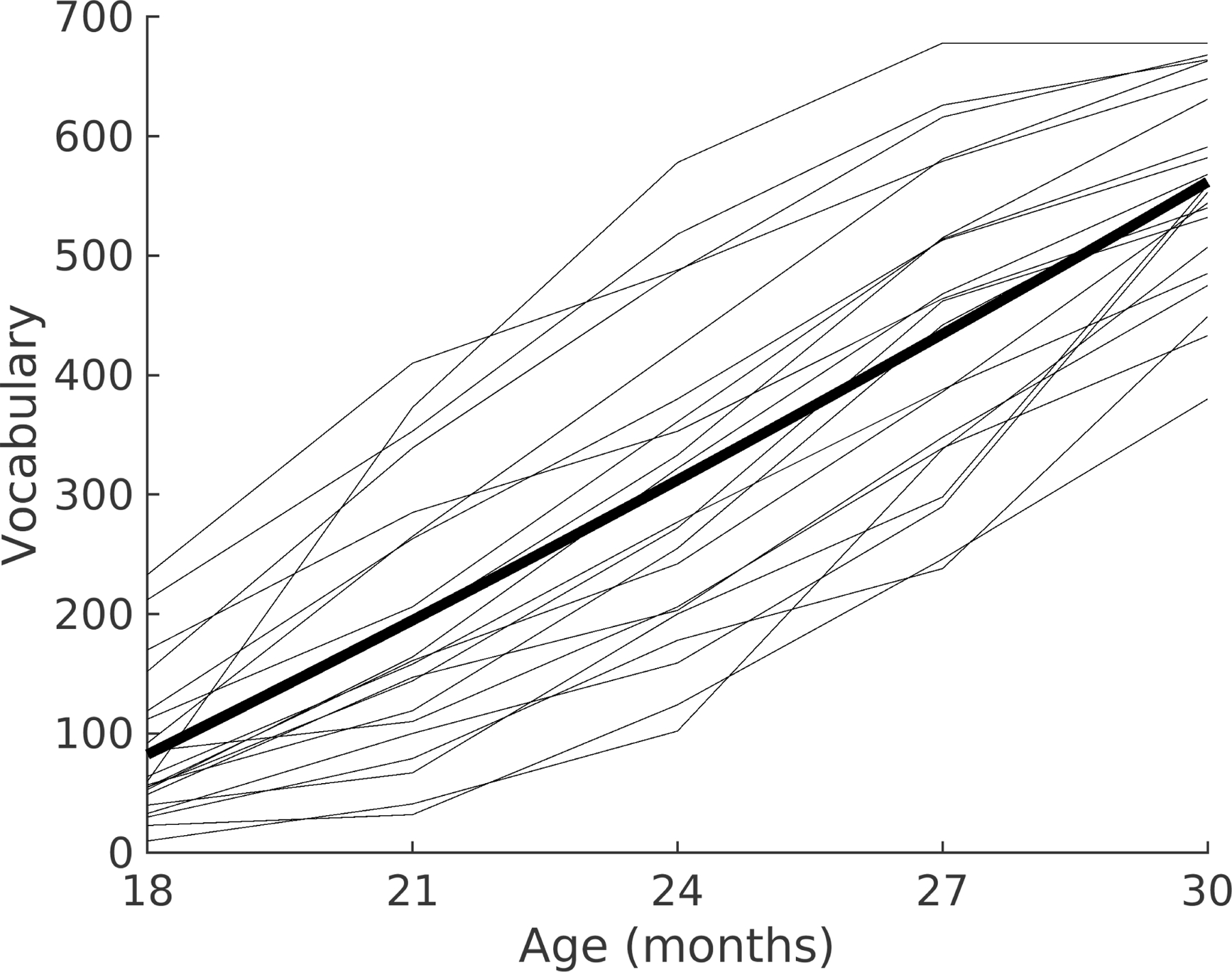

The hypothesis critical to theory is whether individual infants’ brain measures at 5 months of age predict individual differences in vocabulary development between 18 and 30 months of age (see Methods for vocabulary measurement details). We developed a series of linear mixed-effect models in each ROI of the left and right hemispheres, and for both the social and nonsocial conditions, to assess whether RTP at 5 months predicts growth in vocabulary from 18 to 30 months. As shown in Figure 3, productive vocabulary size measured at 18, 21, 24, 27, and 30 months shows typical growth trajectories for all infants43.

Figure 3. Vocabulary growth as a function of age.

Vocabulary growth (see Methods) as a function of age for each of the 21 individual children (grey lines) and the mean vocabulary score for the group (bold). Age is shown in months, and vocabulary in average words produced.

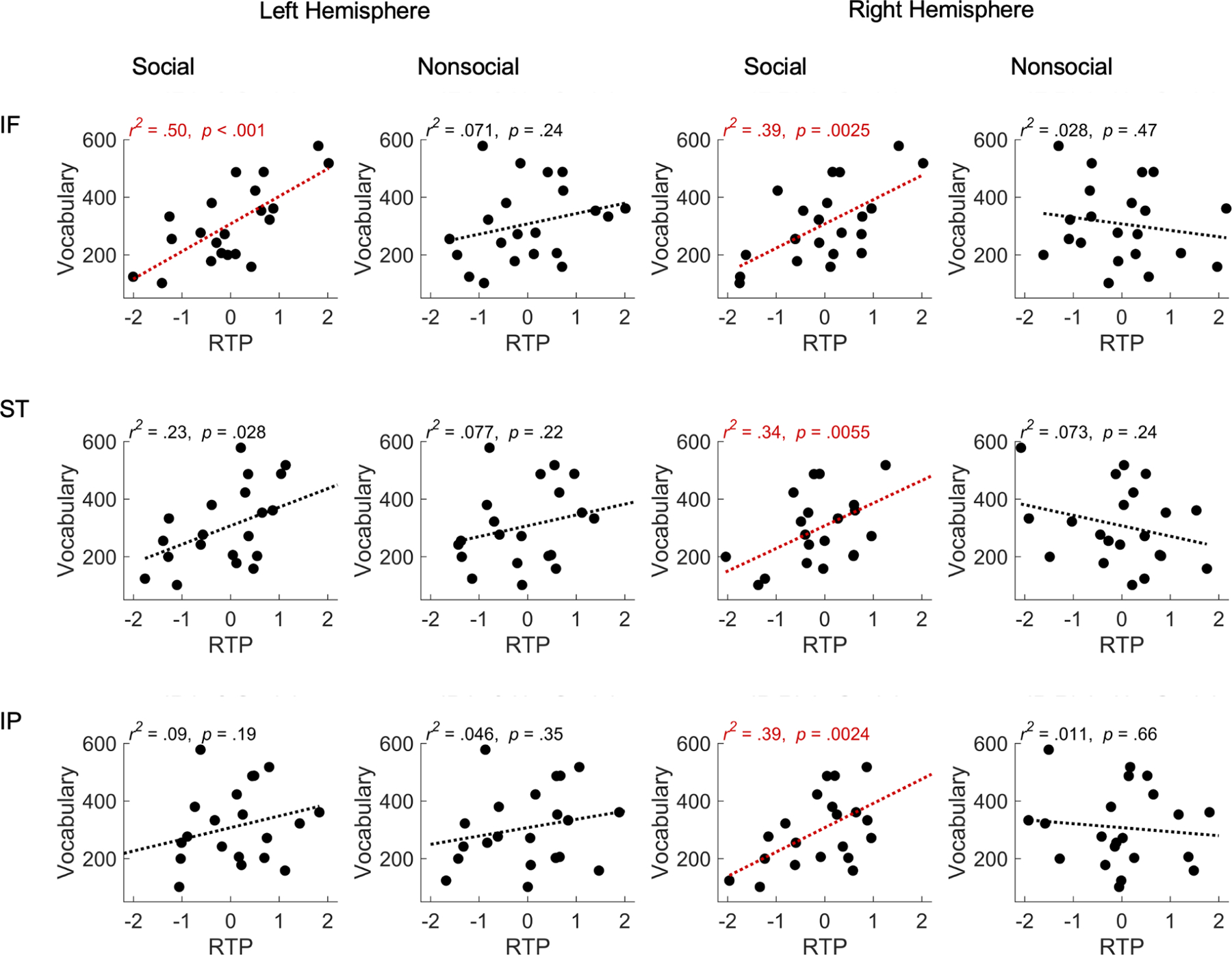

Figure 4 displays scatter plots relating RTP (in l-IF, r-IF, l-ST, r-ST, l-IP, and r-IP) to children’s CDI vocabulary scores at 24 months (the age that corresponds to the intercept in the linear models), for the social and nonsocial conditions. In brain regions related to attention (r-IF, r-ST, r-IP) and sensorimotor processing (l-IF), the magnitude of RTP during the social condition (all p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons) showed a significant positive association with the size of the 24-month vocabulary (see Supplementary Materials for an additional analysis), as well as a significant association with vocabulary growth from 18 through 30 months (see Table S1). In contrast, for the nonsocial condition, the same correlations were not significant (all p > 0.05, Bonferroni corrected, see Table S2).

Figure 4. Scatter plots showing the correlation between neural activity during social and nonsocial conditions at 5 months of age and children’s later language skills at 24 months.

Left two columns show RTP for the social and nonsocial conditions in relation to children’s productive vocabulary score at 24 months for the left hemisphere: inferior frontal (IF), superior temporal (ST), and inferior parietal (IP). Right two columns show the same information for the right hemisphere. Each point represents a single child participant. The x-axis values reflect standardized RTP. Lines are simple linear regression fits, with the variance explained (r2) p-values indicated (Bonferroni corrected p < 0.05). Significant effects are shown in red.

Discussion

The findings show that at 5 months of age, live face-to-face social verbal interaction between an infant and an adult who is responsive to the infant’s cues increases infants’ brain activity significantly in the 4–8 Hz (theta) band in brain regions involved in attention compared to a nonsocial control condition. Moreover, and more critical for theory, we found that infants’ individual levels of neural activation in both attention and sensorimotor brain areas during the social condition (but not the nonsocial condition) show a strong positive association with subsequent longitudinal measures of those same infants’ prospective language skills at 18, 21, 24, 27, and 30 months of age.

These differential effects of the social and nonsocial conditions cannot be attributed simply to hearing speech alone, because each infant listened to the same adult speak for the same amount of time in the two conditions, in each case using language that is appropriate to their social partners in natural everyday settings. The results are therefore unlikely to be attributed simply to infants’ brain processing of auditory speech in the two conditions. Instead, we argue that the results are attributable to infants’ attention and engagement in response to the species-specific social ensemble that exists when adults address and interact with young infants during face-to-face encounters.

To our knowledge, this is the first use of infant MEG brain imaging to study the effects of face-to-face social interaction on infants’ oscillatory brain activity. It is also the first study to link oscillatory activity during live natural social interaction with prospective measures of language growth at multiple time intervals in a longitudinal study. Our work fits with previous work showing larger theta activity to social stimuli during infancy26,24.

It is noteworthy that we measured infants’ attention prior to the initial ‘sensitive period’ that exists in early language learning to assess the potential link between infant attention and initial language learning. Selective attention to face-to-face social verbal interactions with an adult who responds naturally, adapting to the infant’s behavior during this early period, may support language learning when the sensitive periods opens.

The pattern of findings suggests that infants’ attention to the social ensemble when adults are in face-to-face social communication with them may play a more important role in language acquisition than previously acknowledged44. We hypothesize that the social ensemble initially helps capture infant attention. Caregivers’ animated faces, parentese speech, and their tendencies to respond contingently—the package that makes up the uniquely human social ensemble—attracts and holds infants’ attention, motivating them to learn, and may provide the initial impetus and opportunity for learning aspects of language. In the absence of children’s early attention to social speech stimuli, as is common in young children with ASD, language learning may be limited (see11,45,46,47 for data and discussion).

The current data contribute to several ongoing theoretical discussions about the role that the left inferior frontal (l-IF) area plays in speech processing. We show that infants’ responses in the l-IF area during the social condition is a strong predictor of future language development. Previous reports show that infants activate the l-IF in response to hearing speech, but not nonspeech, as early as 2 months of age19,20,21,48. This could indicate activation of speech-motor planning (though studies show that activation in motor brain regions can also be attributed to sensitivity to acoustic features of speech49). Moreover, behavioral studies have demonstrated that infants specifically map between auditory and motor instantiations of speech early in development: 5-month-old infants imitate the vowels they hear50 and detect the match between visually and auditorily presented vowel sounds51. Studies also show that somatosensory information can influence infants’ perception of speech52. Taken together, all of this work suggests that infants’ speech perception is deeply linked to sensorimotor representations. Additional studies will be necessary to understand the precise role that IF brain areas play in initial language learning prior to speech production by infants53,54, but our results tentatively suggest that social encounters involving speech not only activate infants’ inferior frontal areas (which include Broca’s area), but that the degree of activation in individual infants is strongly predictive of that infant’s prospective language abilities as shown by the longitudinal findings reported here.

In the present study, we examine infants’ brain responses to the entire social ensemble, reflecting infants’ everyday experiences. Individual components of the social ensemble, such as infant-directed speech55,56,57,58, contingency59, and parental sensitivity60 have been associated with future language abilities, but in older infants. Future neuroscience studies can isolate components of the ensemble, and examine how each affects infant attention, now that the current results establish that the composite social ensemble evokes brain responses in infants as young as 5 months of age that predict future language development.

Finally, we note that our results are compatible with extant two-person neuroscience studies in which both people are simultaneously measured by brain-imaging equipment while engaged in face-to-face exchanges. Dual-EEG, dual-fNIRS, and dual-MEG experiments show that neural regions in two brains engaged in social interaction activate in neural synchrony (see61,62 for reviews). These studies have suggested that neural synchrony may be a marker of attuned human social interaction, even during infancy61,63.

In summary, the current study shows that brain activity elicited during face-to-face language-rich social interactions between 5-month-old infants and an adult, prior to the initial ‘sensitive period’ for phonetic and word learning, is predictive of children’s developing language skills, as measured using longitudinal assessments in individual children. In typically developing children, attention to a social partner is advantageous and bidirectional, and may itself be rooted in the quality of one-on-one interactions between caregivers and their infants.

Sensorimotor brain activation may prompt and be prompted by early conversational turn-taking, which is significantly linked to future language as well as white matter growth in neural pathways that support the language network22. Social interactions in infancy may thus influence multiple aspects of development, including children’s later language, social, emotional, and cognitive development55,60,64. Further studies will be needed to advance our understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms that link infants’ language development to their social brains.

STAR★Methods

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Patricia K. Kuhl (pkkuhl@uw.edu).

Materials availability

The study did not produce new materials.

Data and code availability

Original data reported in this paper is available in the folder 2024-F2F-MEG at https://osf.io/2xf4y/.

Custom analysis scripts are available at https://bit.ly/2023-Infants-Brain.

Data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

Experimental Model and Study Participant Details

Forty-one typically developing English-learning infants participated in the MEG portion of the study. All participants were recruited through a university-wide Developmental Participants’ Pool at 5 months of age (M = 5.19, SD = 0.16; 22 male). The infants had no history of ear infections or other hearing difficulties, were born full term (39–42 weeks gestational age), had normal birth weights (6–10 lbs), and had no older siblings (first-born children). We obtained ethical approval from the University of Washington Human Subjects Division. The parents or legal guardians of all participants provided informed written consent as per the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data from three infants were not deemed useable due to fussiness during the nonsocial condition of MEG session and data collection was stopped and the data were not processed. These infants were not invited to complete the longitudinal portion of the language measure. Seventeen additional infants were not included in the final analysis because they left the longitudinal portion of the study (N = 1), had too few trials after data preprocessing (N = 6), had a later diagnosis of speech delay (N = 4) or developmental delay (N = 2), or technical error during recording and data could not be processed (N = 4). Twenty-one (13 male) had sufficient artifact-free MEG data, and completed all scheduled CDI questionnaires to be included in the analysis.

Method Details

MEG Recording and Behavioral Procedures

Whole-head magnetic field recordings were made with a SQUID-sensor MEG system (Neuromag - Elekta Oy, Helsinki, Finland), consisting of 204 planar gradiometers and 102 magnetometers. Prior to recording, five head position indicator (HPI) coils attached to a nylon cap were placed on the infant’s head. Positions of the coils, nasion and periauricular fiducial points as well as approximately 100 additional points across the head surface were marked using a digitizer system (Fastrak Polhemus - Colchester, VT, USA) for subsequent head movement tracking and anatomical reconstruction. A set of ECG electrodes was also affixed to the infant to measure magnetic fields produced by heart activity. Once the infant was seated under the MEG sensor helmet, field data were recorded continuously at a sampling rate of 3109 Hz and analog filtered between 0.03 and 1025 Hz while the infant sat face-to-face with an adult female experimenter. During the social condition (Figure 1A), the experimenter interacted naturally with the infant, talking and responding positively. During the nonsocial condition (Figure 1B), the experimenter turned 45 degrees away from the infant and interacted naturally with another adult, who was sitting out of view of the infant. The experimenter was cued about which condition was in effect by the color of an LED light controlled by an Arduino based minicomputer that was mounted on the front of the MEG device, visible to the adult experimenter but not the infant (Figure 1). Tucker-Davis RZ6 delivered triggers and allowed for communication between the triggers and the Arduino. Conditions were randomized, separated by 7 s, and a minimum of 16 trials occurred for each condition. The session lasted about 13 min.

Productive Vocabulary Assessment

Productive vocabulary was assessed when participants were 18, 21, 24, 27, and 30 months of age using the MacArthur-Bates CDI, specifically, the 680-word checklist, ‘Words and Sentences,’ a validated language inventory for research65,66. Using the CDI, parents reported the number of words produced by their child based on the 680-word checklist section of the CDI when their child reached the target age.

Quantification and statistical analysis

MEG Data Analysis

MEG data were analyzed with custom software based on the MNE-Python package67,68. Several preprocessing steps were implemented to minimize noise and artifacts and prepare the MEG data for source reconstruction28. First, sensor channels were rejected if they were flat, excessively noisy, or contained numerous transients, using an automated process complemented by manual inspection. Interference external to the helmet was then suppressed using temporal signal space separation (tSSS) with a 4-s buffer69,70, modified to incorporate a 3-component noise projection from the empty room recording71 (‘extended’ tSSS). The process reconstructed bad channels and transformed the MEG signals to account for head movements72. Finally, the signal space projection method73 (SSP) was applied to remove heartbeat artifact based on the ECG signal (or a proxy gradiometer channel when a robust ECG signal could not be obtained) followed by lowpass filtering at 80 Hz.

For source analysis, the sensor data was subsampled to 310.9 Hz and divided into 1-s epochs, overlapping by 0.5 s and spanning the first 7 s of every social and nonsocial condition. Individual epochs were rejected if fewer than 3 head coils were active, head motion was greater than 0.1 m/s translation or 10 deg/s rotation, or the amplitude was above or below criterion levels determined by an automated procedure74. The first 210 valid epochs for each condition were retained. Sources were localized to a high-resolution MRI template brain of a 14-month-old infant, spatially warped and aligned to the digitized head metrics of the individual subjects. The source space consisted of 4098 points per hemisphere, distributed uniformly across the gray-white matter boundary75. Source activity for each epoch was estimated using the sLORETA method76, yielding covariance-normalized temporal waveforms at every source point. Finally, the power spectral density (PSD) of each epoch’s estimated source activity was calculated using the multi-taper approach with a bandwidth parameter of 2 Hz. The power was summed into four bands (theta: 4–8 Hz, alpha: 8–12 Hz, beta: 12–28 Hz, gamma: 28–60 Hz) then normalized point-by-point by the average total power across epochs between 0 and 60 Hz. The values were transformed to log units, resulting in an approximately Gaussian distribution of power, then averaged across the respective epochs resulting in separate relative theta power values (RTP) for the social and nonsocial conditions at each point of the discrete source space.

Regions of Interest and Statistical Analyses

The cortical source space was parcellated into 34 cortical regions in each hemisphere according to the “Aparc” anatomical atlas available from FreeSurfer77. From these, the three ROIs of each hemisphere were defined (Figure 2A). The ST and IP ROIs were defined from the single Aparc regions of the same name. The IF ROI was defined by combining the pars orbitalis, triangularis, and opercularis regions. Combining anatomical regions was intended to mitigate localization errors incurred by imperfect head movement compensation and subject-to-subject variability in cortical topography, and the use of a surrogate MRI template for anatomical registration.

Statistical analysis was performed on RTP values averaged across all source points within each ROI then transformed from log units to a linear percentage scale. A priori planned comparisons were used to test for differences between response magnitudes during social and nonsocial conditions within each ROI and are two-tailed, α set at p < 0.05 and Cohen’s d reported as effect size. Preliminary independent sample two-tailed t-tests comparing RTP across ROIs with sex as the between group factor indicated no significant effects of sex for any of the ROIs (all ps > 0.13, with the exception of r-IF, p = 0.07). Thus, sex was excluded as a variable in subsequent analyses. Statistical calculations were conducted with the statistical computing package JASP (JASP Team, 2023. JASP Version 0.18.1 [Computer software], BibTeX).

Linear Modeling of Vocabulary Growth and Relation to RTP

Multivariate linear mixed effects models were developed to evaluate the relation between RTP levels at age 5 months and growth in language scores from 18 to 30 months. A baseline model included fixed and random effects for the intercept, slope (growth as function of age, in months, mean centered and standardized), and acceleration (age x age) terms. The acceleration term was included to capture non-linear growth in measured vocabulary, which was observed in the current sample and is expected for the CDI vocabulary measure at these ages65,66. Model comparisons indicated that the model including age provided a better fit to the data than either a model including only a linear growth term, or one including an additional cubic term (age). All fittings were carried out using custom software written in MATLAB (R2023a) and the MathWorks Statistics and Machine Learning toolbox.

After fitting the baseline model, a second set of models were developed to test the interaction between vocabulary development and RTP within each ROI and hemisphere, for the social and nonsocial conditions. Prior to fitting, RTP scores were mean centered and standardized within ROIs. For each ROI model, significance of the fixed coefficients was assessed after Bonferroni correction based on the number of models considered (6 in total: 3 ROIs and 2 hemispheres, see also Tables S1 and S2). The impact and significance of adding variables beyond the baseline model was assessed on the basis of r-square values and by comparison of likelihood ratios and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The residuals of all models exhibited acceptable homoskedasticity and approximately normal distributions according to the Shapiro test (p > 0.05 for all models).

An additional analysis compared the coefficients obtained for the social and nonsocial conditions in each ROI78. The results indicated significant differences between conditions in the l-IF, z(1.98), p = .024, r-IF, z(2.93), p = .002, r-ST z(2.74), p = 0.003, r-IP z(2.44), p = 0.007. Differences were not significant in l-ST z(0.90), p = 0.19 or in l-IP, z(0.47), p = 0.32.

Supplementary Material

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Software and algorithms | ||

| eSSS | Helle et al. 202071 | |

| FreeSurfer | Desikan et al. 200677 | RRID:SCR_001847 |

| JASP Version 0.18.1 | JASP Team: http://www.jasp-stats.org | RRID:SCR_015823 |

| MATLAB R2023a | Mathworks Inc.: https://www.mathworks.com/ | RRID:SCR_001622 |

| MNE-Python Version 1.0.3 | Gramfort et al. 2013, 201467,68 https://mne.tools |

RRID:SCR_005972 |

| sLORETA | Pascual-Marqui 200276 | RRID:SCR_013829 |

| SSP | Uusitalo & Ilmoniemi 199773 | |

| Tucker-Davis RZ6 | https://www.tdt.com/component/rz6-multi-i-o-processor/ | RRID:SCR_018153 |

| tSSS | Taulu & Simola 200670 | |

| Other | ||

| Custom analysis scripts | This paper | https://bit.ly/2023-Infants-Brain |

| Current Designs Fiber Optic Response Pad | https://www.curdes.com/mainforp/responsedevices/hhsc-2×4-c.html | SKU#: HHSC-2×4-C |

| I-LABS MEG Brain Imaging Center | https://ilabs.uw.edu/meg-brain-imaging/ | RRID:SCR_024836 |

| Polhemus Fastrak | Polhemus, Colchester, VT, USA | Electromagnetic digitizer |

Highlights.

Adults interact with human infants using a species-specific social ensemble

Infant neural responses to social vs. nonsocial interaction significantly differed

Brain areas involved in attention activate more strongly for the social condition

Individual variation in infant brain activation predicts language 2.5 years later

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by grants from the Bezos Family Foundation and the Overdeck Family Foundation to PKK and ANM, and from NIH (R21EB033577–01, R01NS104585–01A1) to ST. We thank A. Kunz, B. Woo, D. Hathaway, D. Padden, K. Edlefsen, M. Clarke, M. Reilly, N. Miles Dunn, N. Shoora, and R. Brooks, for assisting with the research and A. Canavan for the graphical illustration. We are grateful to the families that participated.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Werker JF, and Tees RC (1984). Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behav Dev 7, 49–63. 10.1016/S0163-6383(84)80022-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuhl PK, Stevens E, Hayashi A, Deguchi T, Kiritani S, and Iverson P (2006). Infants show a facilitation effect for native language phonetic perception between 6 and 12 months. Dev Sci 9, F13–F21. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Best CC, and McRoberts GW (2003). Infant perception of non-native consonant contrasts that adults assimilate in different ways. Lang Speech 46, 183–216. 10.1177/00238309030460020701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsao F-M, Liu H-M, and Kuhl PK (2006). Perception of native and non-native affricate-fricative contrasts: Cross-language tests on adults and infants. J Acoust Soc Am 120, 2285–2294. 10.1121/1.2338290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhl PK, Tsao F-M, and Liu H-M (2003). Foreign-language experience in infancy: Effects of short-term exposure and social interaction on phonetic learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 9096–0101. 10.1073/pnas.1532872100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conboy BT, and Kuhl PK (2011). Impact of second-language experience in infancy: Brain measures of first- and second-language speech perception. Dev Sci 14, 242–248. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00973.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakuno Y, Pirazzoli L, Blasi A, Johnson MH, and Lloyd-Fox S (2018). Optical imaging during toddlerhood: Brain responses during naturalistic social interactions. Neurophotonics 5, 011020. 10.1117/1.NPh.5.1.011020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colombo J, and Salley B (2015). Biopsychosocial perspectives on the development of attention in infancy. In Handbook of Infant Biopsychosocial Development, Calkins SD ed. (The Guilford Press; ), pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Felice S, Hamilton AFDC, Ponari M, and Vigliocco G (2023). Learning from others is good, with others is better: The role of social interaction in human acquisition of new knowledge. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 378, 20210357. 10.1098/rstb.2021.0357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werker JF, and Hensch TK (2015). Critical periods in speech perception: New directions. Annu Rev Psychol 66, 173–196. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce K, Wen TH, Zahiri J, Andreason C, Courchesne E, Barnes CC, Lopez L, Arias SJ, Ezquivel A, and Cheng A (2023). Level of attention to motherese speech as an early marker of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Network Open 6, e2255125. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhl PK, Coffey-Corina S, Padden D, Munson J, Estes A, and Dawson G (2013). Brain responses to words in 2-year-olds with autism predict developmental outcomes at age 6. PLoS ONE 8, e6496. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen TH, Cheng A, Andreason C, Zahiri J, Xiao Y, Xu R, Bao B, Courchesne E, Barnes CC, Arias SJ, and Pierce K (2022). Large scale validation of an early-age eye-tracking biomarker of an autism spectrum disorder subtype. Sci Rep 12, 4253. 10.1038/s41598-022-08102-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka M, Sun F, Li Y, and Mooney R (2018). A mesocortical dopamine circuit enables the cultureal transmission of vocal behavior. Nature 563, 117–120. 10.1038/s41586-018-0636-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pulvermüller F, and Fadiga L (2010). Active perception: Sensorimotor circuits as a cortical basis for language. Nat Rev Neurosci 11, 351–360. 10.1073/pnas.0509989103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson SM, Saygin AP, Sereno MI, and Iacoboni M (2004). Listening to speech activates motor areas involved in speech production. Nat Neurosci 7, 701–702. 10.1038/nn1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pulvermüller F, Huss M, Kherif F, Moscoso del Prado Martin F, Hauk O, and Shtyrov Y (2006). Motor cortex maps articulatory features of speech sounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 7865–7870. 10.1073/pnas.0509989103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cogan GB, Thesen T, Carlson C, Doyle W, Devinsky O, and Pesaran B (2014). Sensory-motor transformations for speech occur bilaterally. Nature 507, 94–98. 10.1038/nature12935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhl PK, Ramírez R, Bosseler AN, Lin J-FL, and Imada T (2014). Infants’ brain responses to speech suggest analysis by synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 11238–11245. 10.1073/pnas.1410963111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dehaene-Lambertz G, Hertz-Pannier L, Dubois J, Meriaux S, Roche A, Sigman M, and Dehaene S (2006). Functional organization of perisylvian activation during presentation of sentences in preverbal infants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 14240–14245. 10.1073/pnas.0606302103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imada T, Zhang Y, Cheour M, Taulu S, Ahonen A, and Kuhl PK (2006). Infant speech perception activates Broca’s area: A developmental magnetoencephalography study. NeuroReport 17, 957–962. 10.1097/01.wnr.0000223387.51704.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber E, Corrigan NM, Yarnykh VL, Ferjan Ramírez N, and Kuhl PK (2023). Language experience during infancy predicts white matter myelination at age 2 years. J Neurosci 43, 1590–1599. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1043-22.2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones EJH, Goodwin A, Orekhova E, Charman T, Dawson G, Webb SJ, and Johnson MH (2020). Infant EEG theta modulation predicts childhood intelligence. Sci Rep 10, 11232. 10.1038/s41598-020-67687-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Velde B, White T, and Kemner C (2021). The emergence of a theta social brain network during infancy. NeuroImage 240, 118298. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menn KH, Ward EK, Braukmann R, van den Boomen C, Buitelaar J, Hunnius S, and Snijders TM (2022). Neural tracking in infancy predicts language development in children with and without family history of autism. Neurobiology of Language 3, 495–514. 10.1162/nol_a_00074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones EJH, Venema K, Lowy R, Earl RK, and Webb SJ (2015). Developmental changes in infant brain activity during naturalistic social experiences. Dev Psychobiol 57, 842–853. 10.1002/dev.21336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen T, Zimmer L, and Hoehl S (2023). Your turn, my turn. Neural synchryony in mother–infant proto-conversation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 378, 20210488. 10.1098/rstb.2021.0488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke MD, Bosseler AN, Mizrahi JC, Peterson ER, Larson E, Meltzoff AN, Kuhl PK, and Taulu S (2022). Infant brain imaging using magnetoencephalography: Challenges, solutions, and best practices. Hum Brain Mapp 43, 3609–3619. 10.1002/hbm.25871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernald A, and Kuhl P (1987). Acoustic determinants of infant preference for motherese speech. Infant Behav Dev 10, 279–293. 10.1016/0163-6383(87)90017-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosseler AN, Clarke M, Tavabi K, Larson ED, Hippe DS, Taulu S, and Kuhl PK (2021). Using magnetoencephalography to examine word recognition, lateralization, and future language skills in 14-month-old infants. Dev Cogn Neurosci 47, 100901. 10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duncan J (2001). An adaptive coding model of neural function in prefrontal cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci 2, 820–829. 10.1038/35097575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramezanpour H, and Fallah M (2022). The role of temporal cortex in the control of attention. Current Research in Neurobiology 3, 100038. 10.1016/j.crneur.2022.100038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hickok G, Costanzo M, Capasso R, and Miceli G (2011). The role of Broca’s area in speech perception: Evidence from aphasia revisited. Brain and Language 119, 214–220. 10.1016/j.bandl.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fadiga L, Craighero L, and D’Ausilio A (2009). Broca’s area in language, action, and music. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1169, 448–458. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosseler AN, Taulu S, Pihko E, Mäkelä JP, Imada T, Ahonen A, and Kuhl PK (2013). Theta brain rhythms index perceptual narrowing in infant speech perception. Front Psychol 4, 690. 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klimesch W, Freunberger R, Sauseng P, and Gruber W (2008). A short review of slow phase synchronization and memory: Evidence for control processes in different memory systems? Brain Res 1235, 31–44. 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Begus K, and Bonawitz E (2020). The rhythm of learning: Theta oscillations as an index of active learning in infancy. Dev Cogn Neurosci 45, 100810. 10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawasaki M, and Yamaguchi Y (2013). Frontal theta and beta synchronizations for monetary reward increase visual working memory capacity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 8, 523–530. 10.1093/scan/nss027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bazhenova OV, Stroganova TA, Doussard-Roosevelt JA, Posikera IA, and Porges SW (2007). Physiological responses of 5-month-old infants to smiling and blank faces. Int J Psycholophysiol 63, 64–76. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orekhova EV, Stroganova TA, Posikera IN, and Elam M (2006). EEG theta rhythm in infants and preschool children. Clin Neurophysiol 117, 1047–1062. 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, Pethick SJ, Tomasello M, Mervis CB, and Stiles J (1994). Variability in early communicative development. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 59, 1–185. 10.2307/1166093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graziano AM, and Raulin ML (2020). Research methods: A process of inquiry 9th edn (Pearson; ). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fenson L, Pethick S, Renda C, Dale PS, and Reznick JS (1998). Normative data for the short form versions of the MacArthur communicative development inventories. Infant Behavior and Development 21, 404. 10.1016/S0163-6383(98)91617-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Call J, Behne T, and Moll H (2005). Understanding and sharing intentions: The origins of cultural cognition 28, 675–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stavropoulos KKM, and Carver LJ (2014). Reward anticipation and processing of social versus nonsocial stimuli in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 55, 1398–1408. 10.1111/jcpp.12270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stavropoulos KKM, and Carver LJ (2018). Oscillatory rhythm of reward: Anticipation and processing of rewards in children with and without autism. Mol Autism 9, 1–15. 10.1186/s13229-018-0189-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dawson G, Meltzoff AN, Osterling J, Rinaldi J, and Brown E (1998). Children with Autism fail to orient to naturally occurring social stimuli. J Autism Dev Disord 28, 479–485. 10.1023/a:1026043926488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clarke MD (2021). Neural dynamics of the motor system in speech perception. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheung C, Hamilton LS, Johnson K, and Chang EF (2016). The auditory representation of speech sounds in human motor cortex. eLife 5, e12577. 10.7554/eLife.12577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuhl PK, and Meltzoff AN (1996). Infant vocalizations in response to speech: Vocal imitation and developmental change. J Acoust Soc Am 100, 2425–2438. 10.1121/1.417951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuhl PK, and Meltzoff AN (1982). The bimodal perception of speech in infancy. Science 218, 1138–1141. 10.1126/science.7146899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruderer AG, Danielson DK, Kandhadai P, and Werker JF (2015). Sensorimotor influences on speech perception in infancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 13531–13536. 10.1073/pnas.1508631112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuhl PK (2021). Infant speech perception: Integration of multimodal data leads to a new hypothesis—Sensorimotor mechanisms underlie learning. In Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology: Human Communication: Origins, Mechanism, and Functions Vol. 40, Sera, Sera MD and Koenig M, eds. (Wiley; ), pp. 113–149. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi D, Yeung HH, and Werker JF (2023). Sensorimotor foundations of speech perception in infancy. Trends Cogn Sci 23, 773–784. 10.1016/j.tics.2023.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Golinkoff R, Hoff E, Rowe ML, Tamis-LeMonda CS, and Hirsch-Pasek K (2019). Language matters: Denying the existence of the 30-million-word gap has serious consequences. Child Dev 90, 985–992. 10.1111/cdev.13128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romeo RR, Leonard JA, Robinson ST, West MR, Mackey AP, Rowe ML, and Gabrieli JDE (2018). Beyond the 30-million-word gap: Children’s conversational exposure is associated with langauge-related brain function. Psychol Sci 29, 700–710. 10.1177/0956797617742725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferjan Ramírez N, Roseberry Lytle S, and Kuhl PK (2020). Parent coaching increases conversational turns and advances infant language development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117, 3484–3491. 10.1073/pnas.1921653117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Masek LR, Paterson SJ, Golinkoff RM, Bakeman R, Adamson LB, Owen MT, Pace A, and Hirsh-Pasek K (2021). Beyond talk: Contributions of quantity and quality of communication to language success across socioeconomic strata. Infancy 26, 123–147. 10.1111/infa.12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goldstein MH, and Schwade JA (2008). Social feedback to infants’ babbling facilitates rapid phonological learning. Psychol Sci 19, 515–523. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02117.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tamis-LeMonda CS, Kuchirko Y, and Song L (2014). Why is infant language learning facilitated by parental responsiveness? Current Directions in Psychol Sci 23, 121–126. 10.1177/0963721414522813 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin J-FL, Imada T, Meltzoff AN, Hiraishi H, Ikeda T, Takahashi T, Hasegawa C, Yoshimura Y, Kikuchi M, Hirata M, et al. (2023). Dual-MEG interbrain synchronization during turn-taking verbal interactions between mothers and children. Cereb Cortex 33, 4116–4134. 10.1093/cercor/bhac330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Endevelt-Shapira Y, Djalovski A, Dumas G, and Feldman R (2021). Maternal chemosignals enhance infant-adult brain-to-brain synchrony. Sci Adv 7, eabg6867. 10.1126/sciadv.abg6867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Endevelt-Shapira Y, and Feldman R (2023). Mother–infant brain-to-brain synchrony patterns reflect caregiving profiles. Biology 12, 248. 10.3390/biology12020284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.. Meltzoff AN, Kuhl PK, Movellan J, and Sejnowski TJ (2009). Foundations for a new science of learning. Science 325, 284–288. 10.1126/science.1175626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fenson L, Dale P, Reznick JS, Thal D, Bates E, Harung J, and Reilly J (1993). The MacArthur communicative development inventories: User’s guide and technical manual (Singular Publishing Group; ). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fenson L, Marchman VA, Thal D, Dale PS, Reznick JS, and Bates E (2006). MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventories: User’s guide and technical manual 2nd edn (Brookes; ). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gramfort A, Luessi M, Larson E, Engemann DA, Strohmeier D, Brodbeck C, Goj R, Jas M, Brooks R, Parkkonen L, et al. (2013). MEG and EEG data analysis with MNE_Python. Front Neurosci 7, 267. 10.3389/fnins.2013.00267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gramfort A, Luessi M, Larson E, Engemann DA, Strohmeier D, Brodbeck C, Parkkonen L, and Hämäläinen MS (2014). MNE software for processing MEG and EEG data. NeuroImage 86, 446–460. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taulu S, and Hari R (2009). Removal of magnetoencephalographic artifacts with temporal signal‐space separation: Demonstration with single‐trial auditory‐evoked responses. Hum Brain Mapp 30, 1524–1534. 10.1002/hbm.20627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taulu S, and Simola J (2006). Spatiotemporal signal space separation method for rejecting nearby interference in MEG measurements. Phys Med Biol 51, 1759. 10.1088/0031-9155/51/7/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Helle LM, Nenonen J, Larson E, Simola J, Parkkonen L, and Taulu S (2020). Extended Signal-Space Separation method for improved interference suppression in MEG. IEEE Tran Biomed Eng 68, 2211–2221. 10.1109/tbme.2020.3040373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Taulu S, and Kajola M (2005). Presentation of electromagnetic multichannel data: The signal space separation method. J Appl Phys 97, 124901–124910. 10.1063/1.1935742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uusitalo MA, and Ilmoniemi RJ (1997). Signal-space projection method for separating MEG or EEG into components. Med Biol Eng Comp 35, 135–140. 10.1007/bf02534144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jas M, Engemann DA, Bekhti Y, Raimondo F, and Gramfort A (2017). Autoreject: Automated artifact rejection for MEG and EEG data. NeuroImage 159, 417–429. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mittag M, Larson E, Clarke M, Taulu S, and Kuhl PK (2021). Auditory deficits in infants at risk for dyslexia during a linguistic sensitive period predict future language. NeuroImage Clin 30, 102578. 10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pascual-Marqui RD (2002). Standardized low-resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA): Technical details. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 24, 5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, et al. (2006). An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage 31, 968–980. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lenhard W, and Lenhard A (2014). Testing the significance of correlations. Psychometrica. 10.13140/RG.2.1.2954.1367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Original data reported in this paper is available in the folder 2024-F2F-MEG at https://osf.io/2xf4y/.

Custom analysis scripts are available at https://bit.ly/2023-Infants-Brain.

Data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.