Abstract

Background:

Ninety percent of infants with Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) brain involvement have seizure onset before 2 years of age; this is associated with worse neurologic outcome. Presymptomatic treatment before seizure onset may delay seizure onset and improve outcome, as has been shown in other conditions with a high-risk of developing epilepsy such as tuberous sclerosis complex. Electroencephalogram (EEG) may be a biomarker to predict seizure onset. This retrospective clinical data analysis aims to assess impact of presymptomatic treatment in SWS.

Methods:

This two-centered, IRB-approved, retrospective study analyzed records from patients with SWS brain involvement. Clinical data recorded included demographics, age of seizure onset (if present), brain involvement extent (unilateral versus bilateral), port-wine birthmark (PWB) extent, family history of seizure, presymptomatic treatment if received, neuroscore, and anti-seizure medication. EEG reports prior to seizure onset were analyzed.

Results:

Ninety-two patients were included (48 females), and 32 received presymptomatic treatment outside of a formal protocol (5 aspirin, 16 aspirin and levetiracetam; 9 aspirin and oxcarbazepine, 2 valproic acid). Presymptomatically-treated patients were more likely to be seizure-free at 2 years (15 of 32; 47% versus 7 of 60; 12%; p<.001). A greater percentage of presymptomatically-treated patients had bilateral brain involvement (38% treated versus 17% untreated; p=.026). Median hemiparesis neuroscore at 2 years was better in presymptomatically-treated patients. In EEG reports prior to seizure onset, the presence of slowing, epileptiform discharges, or EEG-identified seizures was associated with seizure onset by 2 (p=.001).

Conclusion:

Presymptomatic treatment is a promising approach to children diagnosed with SWS prior to seizure onset. Further study is needed, including prospective drug trials, long-term neuropsychological outcome, and prospective EEG analysis to assess this approach and determine biomarkers for presymptomatic treatment.

Keywords: Sturge-Weber Syndrome, epilepsy, vascular malformation, presymptomatic treatment

Introduction

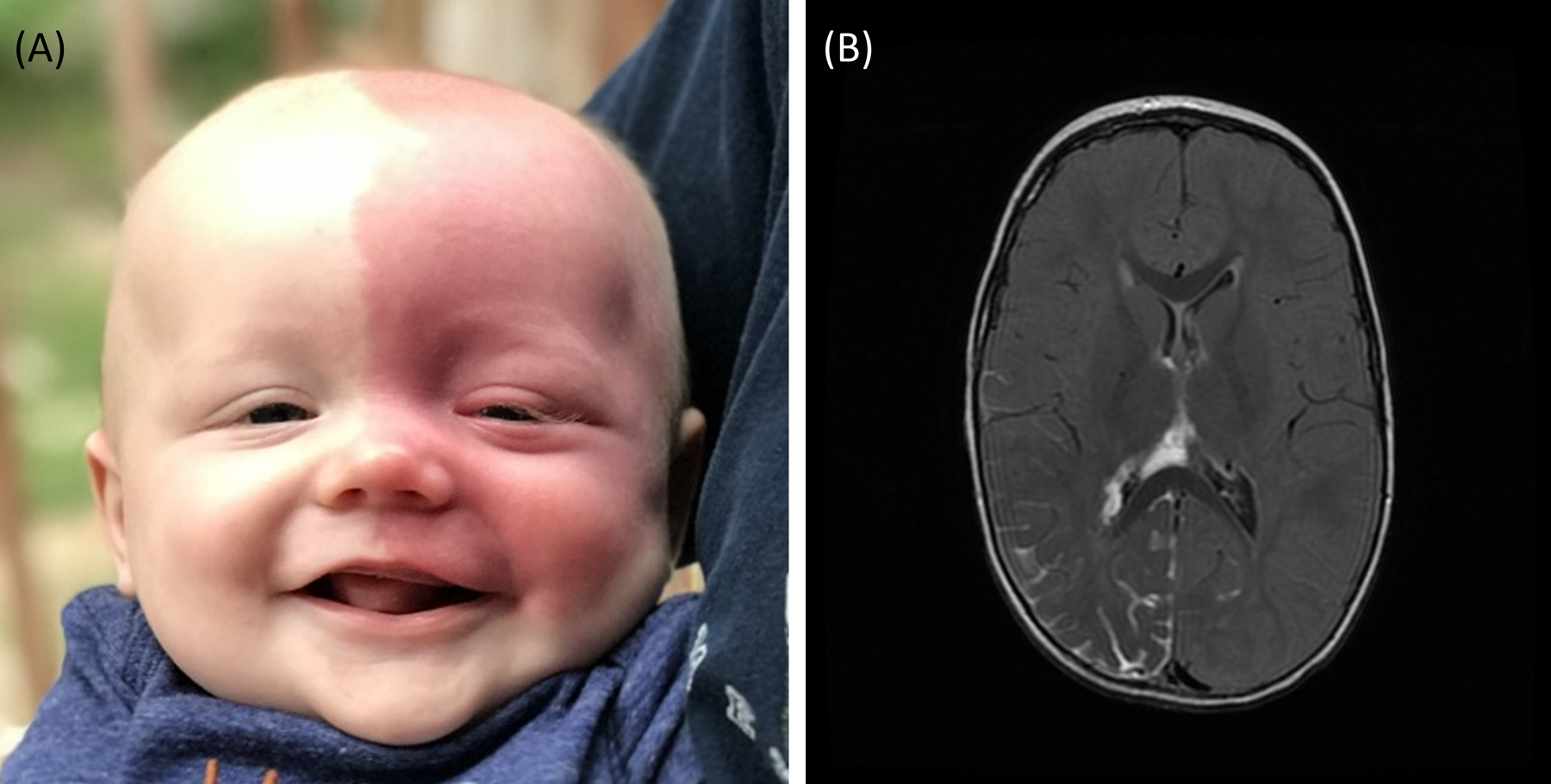

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a neurovascular disorder characterized by a vascular anomaly of the brain. It is a rare disorder that occurs in about 1 in 20,000 to 50,000 live births worldwide, and is usually caused by an R183Q somatic mosaic mutation in the GNAQ gene [1–7]. As a spectrum disorder, patients with SWS can have eye, skin, and/or brain involvement (Figure 1) at varying degrees of severity. Seizures are the most common neurological symptom in patients with brain involvement [8]. Perfusion deficits and venous hypertension result from the brain vascular malformations, and seizures further impair cerebral blood flow resulting in brain atrophy, calcification and injury over time [9–12]. SWS affects brain development in childhood causing intellectual disability, motor impairments, and developmental delays [13]. The extent of brain involvement as seen on contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), presence of high-risk port-wine birthmark (PWB; see Figure 1, Panel A) on the forehead, temple, or eyelids, and age of seizure onset have all been suggested to be predictors of severity of neurologic, cognitive, and epilepsy outcomes [14–17].

Figure 1.

Infant with SWS in panel A has a high-risk left-sided facial port-wine birthmark (PWB) covering the forehead, temple, and both eyelids. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in panel B (neuroimaging from another subject) shows typical SWS right-sided leptomeningeal enhancement on axial post-contrast T2 Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI of the brain.

Most infants with SWS brain involvement will have seizure onset by two years of age, and seizure onset by two years is a key milestone in the clinical course of SWS [18]. A greater extent of brain involvement has been associated with an earlier age of seizure onset and worse seizure severity [16–20]. Early seizure onset has been associated with lower intelligence quotient (IQ), hemiparesis severity, increased seizure activity, worse brain injury, and cognitive decline [13, 21–26]. In a study of 33 young children with SWS, lower outcome IQ was associated with younger age of seizure onset [27]. Studies have also suggested that the preservation of white matter may protect neurocognitive function and improve cognition in patients with SWS [24]. Other evidence from the epilepsy literature suggests that developmental and epileptic encephalopathies may be causative of intellectual disability [28]. Therefore, there is pressing need to find treatments that can delay or even prevent seizure onset.

Pre-symptomatic treatment in SWS – treating patients before the onset of seizure symptoms – carries the potential for delaying or preventing seizure onset. Presymptomatic treatment for infants with SWS brain involvement was first suggested in 2002 with phenobarbital used presymptomatically. This 2002 retrospective study of 16 patients presymptomatically treated with phenobarbital compared to 21 given standard treatment, suggested better seizure and cognitive outcome in the patients with prophylactic treatment. Since then, a couple other small case series have been reported [29, 30]. Research in conditions like tuberous sclerosis have demonstrated that presymptomatic treatment leads to a delay in seizure onset and decrease in seizure severity [31]. It seems likely that other conditions associated with a high risk of early seizures would also benefit from presymptomatic treatment [28]; this was hypothesized in earlier small cohorts of children with SWS [29, 30]. We previously reported initial data from 8 infants with SWS treated presymptomatically, prior to the onset of seizures, which suggested a delay of seizure onset and improved seizure scores in presymptomatically treated infants. Motivated by these early but small-sample-size studies, we hypothesized that presymptomatic treatment may delay seizure onset and improve neurocognitive outcomes in patients with SWS.

This study aims to test this hypothesis using multi-site and the biggest sample size of patients to date. We analyzed 92 patients from data retrospectively collected from Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH) and Kennedy Krieger Institute (KKI). We compared infants treated presymptomatically to those treated post-symptomatically (standard treatment) as part of a previously published protocol [32]. The effect was compared by the age of seizure onset, in these two groups, as well as SWS Neuroscores at 2 years of age [33–35].

Research Methods:

Ethics and Dissemination

This study involves human participants and was approved by Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board: IRB-P00014482 and IRB-P00025916 and by Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board: NA_00043846. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part. Data was de-identified before being recorded in REDCap and combined for analysis.

Data Collection

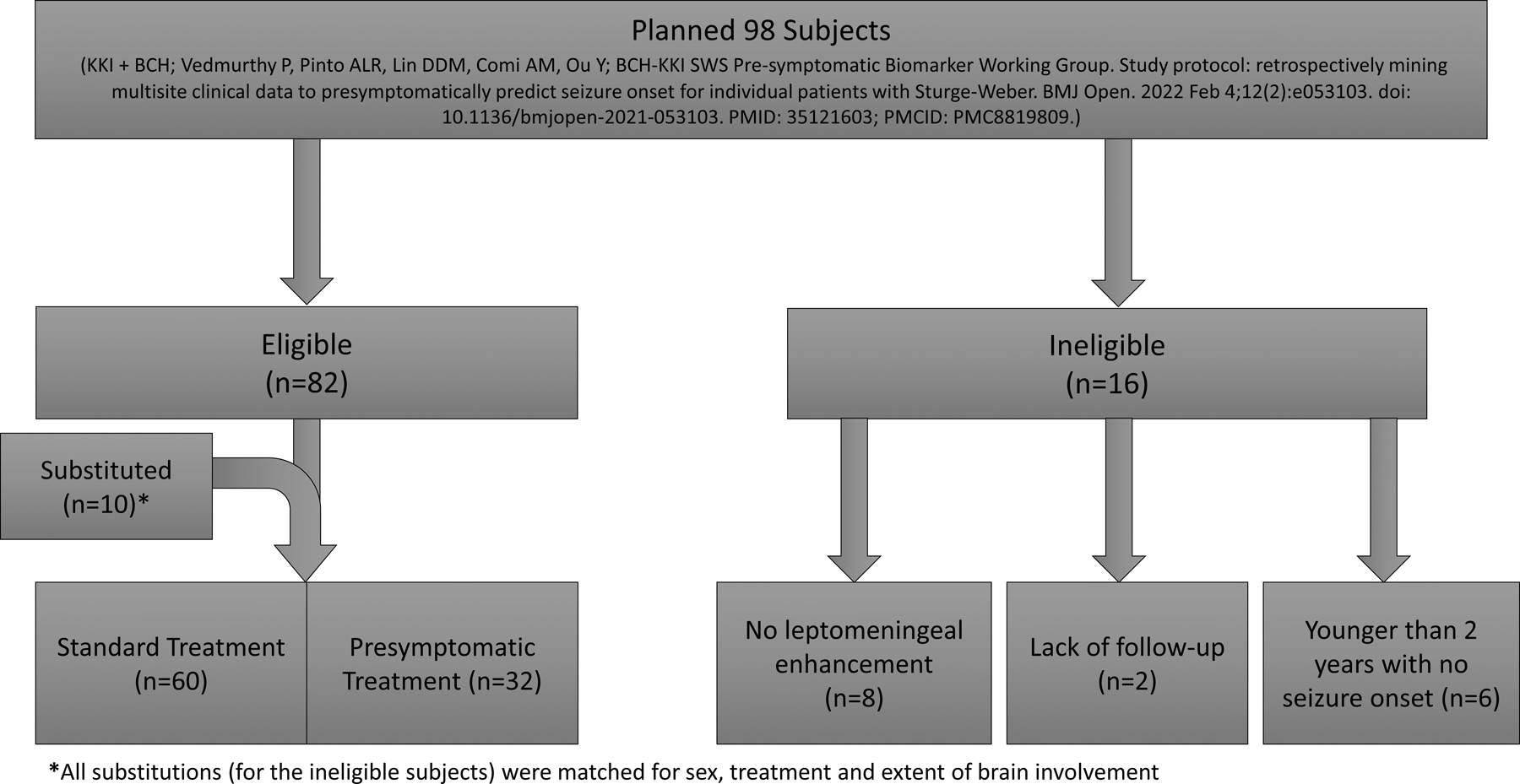

This two-center, retrospective, and IRB-approved study analyzed data from 92 patients (30 from BCH and 62 from KKI) with SWS brain involvement, who either had consent waived (BCH) or previously consented to having their de-identified medical records studied (KKI). Inclusion criteria include: (a) SWS brain involvement including the typical leptomeningeal enhancement on contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain before 2 years of age as confirmed by an SWS expert (Comi at KKI or Pinto at BCH), (b) follow-ups to determine whether they had seizure onset by 2 years of age. Please see the flow diagram (Figure 2) for details on these subjects. Fifteen of these 92 subjects (8 given anti-seizure medication (ASM) and aspirin and 2 given aspirin only presymptomatically; 5 standard treatment) had early data published previously [16]). De-identified data was entered into a REDCap database.

Figure 2.

Flow chart depicts subjects eligible for this study, based on published protocol, including replacement of ineligible subjects. Upon in-depth record review, 16 of the originally planned subjects had to be replaced, due to a lack of SWS brain involvement or sufficient follow up. Those who were replaced were matched for sex, treatment, and extent of brain involvement.

Clinical data recorded include: demographics, PWB and eye/glaucoma presence and extent (none, unilateral, or bilateral), family history of seizure, clinical involvement scores (assigned for each subject based on laterality of brain involvement, eye, and skin involvement; see Supplemental Table 1), extent of brain involvement (none, unilateral, or bilateral), presymptomatic treatment used, presence or absence of seizures by 2 years of age, age of seizure onset (in days; if present), type of seizure (if present), and both current and discontinued seizure medications at 2 years old [26]. Among them, clinical involvement scores were assigned as follows: a score of 0 (no involvement), 1 (unilateral involvement), or 2 (bilateral involvement) for brain, eye, and skin. Possible total scores were between 1 (unilateral brain involvement) and 6 (bilateral brain, skin and eye involvement).

SWS Neuroscore assigned at the clinical visit closest to 2 years was recorded. Neuroscore recorded more than 3 months before or after the participant’s second birthday were not analyzed (see Supplemental Table 2). The Neuroscore (0–15) is comprised of four sub-scores: presence/frequency of seizures (0–4), presence/severity of hemiparesis (0–4), presence of partial/full visual field cut (0–2) and cognitive function based on age (0–5). The cognitive function sub-score scale is age dependent for the following age ranges: birth through preschool aged, school aged, and adult. Higher scores indicate a more severe disease presentation. This score has been previously validated through neuropsychological testing [36], quantitative electroencephalogram (EEG) [37], and neuroimaging [10] and is utilized during other SWS treatment studies and prospective drug trials [33–35]. It is meant to be used as a clinical monitoring tool for patients with SWS. Clinical EEG reports were also reviewed by the same SWS expert clinicians, before entry into the REDCap database. EEGs analyzed were completed before seizure onset and before 2 years of age; however, the availability of a presymptomatic EEG was not an inclusion criterion. Abnormal EEG activity recorded in the clinical database included presence and location of asymmetry or decrease in voltage, excessive slowing, epileptiform discharges and EEG-identified seizures.

Statistical Analysis

All data was analyzed using non-parametric analyses (Chi-square tests of independence, Spearman correlations, Mann-Whitney U, Fisher’s Exact Test, Kruskal-Wallis Test, and Kaplan-Meier survival estimator) as follows: to study (1) which factors were associated with earlier age of seizure onset, 2-sided Mann-Whitney U and independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis Tests; (2) EEG for development as a biomarker for age of seizure onset, 2-sided Chi-square tests of independence and sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values were calculated for EEG data; (3) whether presymptomatic treatment was associated with a difference in seizure onset by two years, a 2-sided Chi-square test of independence and the Kaplan-Meier survival estimator; and (4) whether presymptomatic treatment was associated with improved Neuroscore, a 2-sided Mann-Whitney U test. See Figure 3 for over-view. A binary logistic model was performed including presymptomatic treatment, and clinical factors which prior studies have indicated are predictive of outcome in patients with SWS (extent of brain involvement, extent of skin involvement, and sex) to determine which factors predicted seizure onset by two years. All analysis was performed with SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) Version 28.0.1.1. The significance level for all analyses was p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Diagram shows the questions that this study focuses on answering and the relationship between clinical and diagnostic predictors, presymptomatic treatment, seizure onset, and neurological outcome.

Results:

Demographics

All subjects were born between 2008 and 2021. This study included 92 subjects (48 females and 44 males). Demographics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographics.

| Non-Presymptomatically Treated (n = 60) | Presymptomatically Treated (n = 32) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male Female |

29 (48%) 31 (52%) |

15 (47%) 17 (53%) |

| Brain Involvement | 50 unilateral; 10 bilateral | 20 unilateral;12 bilateral |

| Race | 39 White 3 Black 6 Asian 5 Multi-Racial 3 Other 4 Unknown |

24 White 2 Asian 1 Multi-Racial 1 Other 4 Unknown |

| Ethnicity | 46 Non-Hispanic or Latino 10 Hispanic or Latino 4 Unknown |

25 Non-Hispanic or Latino 3 Hispanic or Latino 4 Unknown |

Of those with seizure onset by two years of age (n=70; 41 female), median age of seizure onset was 199 days for those with unilateral brain involvement versus 112 days for those with bilateral brain involvement (p=.006, Mann-Whitney U). For subjects with no PWB, the median age of seizure onset was 228 days, 261 days for those with unilateral PWB, and 123 days for those with a bilateral PWB (p = .005, Kruskal-Wallis). This significant difference in seizure onset was driven by the relationship between unilateral and bilateral brain involvement (p = .006 Kruskal-Wallis, adjusted by the Dunn-Bonferroni correction for multiple tests). A family history of seizure was not associated with earlier seizure onset.

Presymptomatic Treatments

Sixty subjects (31 female) were not presymptomatically treated and 32 were presymptomatically treated (17 female); 20% of BCH subjects and 42% of KKI subjects (p = .038). Median age at first visit to the centers was 227 days in the standard treatment group and 101.5 days in the presymptomatically treated group (p < .001, Mann-Whitney U Test). Presymptomatic treatment included 5 subjects on low dose aspirin only, 16 on low dose aspirin with levetiracetam, 9 on low dose aspirin with oxcarbazepine, and 2 subjects on valproic acid only. Due to limited sample size in individual treatment types, all presymptomatically treated patients were merged into one group for analysis, regardless of the specific ASM. This strategy is the same as what was used in our previous hypothesis paper [29].

Presymptomatic Treatment and Seizure Onset by Two Years of Age

Seizure onset by age two was experienced by 88% of standard post-symptomatic treated subjects and 53% of those who were presymptomatically treated (X2(1, 92) = 14.2, p < .001). In those with seizure onset, the median age of seizure onset was 166 days in the standard treatment group and 297 days in the presymptomatic treatment group (non-significant). A Kaplan-Meier survival estimate and curve was generated for age of seizure onset (in days) in presymptomatically treated and non-presymptomatically treated groups (see Figure 4). Survival distributions between the two groups were significantly different (p < .001), with age of seizure onset being significantly older in the presymptomatically treated group. Thirty-three percent of those on low dose aspirin and oxcarbazepine (n=16) experienced seizure onset by age two. This is compared to the 69% of those on low dose aspirin and levetiracetam (n=9) who had seizure onset by age two (p=0.115; with no significant difference between these two groups in extent of brain or skin involvement, clinical involvement score, or neuroscore at 2 years of age).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves shows age of seizure onset data in the presymptomatic and standard treatment groups, with a follow-up duration of 2 years after birth (in days). At age 2, 45.2% of presymptomatically treated patients (bolded line) had not experienced seizure onset, while in the standard treatment group only 13.2% had no had seizure onset by two years of age.

There was a significantly higher total clinical involvement score in the presymptomatically treated group, when compared to the standard treatment group (median score 4, IQR 2–4 versus a median of 3, IQR 2–4, p = 0.023; see Table 2). A significantly higher percentage of subjects with bilateral brain involvement were in the presymptomatically treated group (38% versus 17%) than in the standard treatment group (X2(1, 92) = 5.0, p = .026; see Figure 5). Subjects in the presymptomatically treated group also had greater extent of skin involvement (53% bilaterally affected in the presymptomatic group versus 28% in the standard treatment group p = .004; see Table 3).

Table 2. Comparison between Seizure Onset by 2 Years and Sturge-Weber Extent.

| Seizure Onset Before 2 | No Seizure Onset Before 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sturge-Weber Extent | Extent of Involvement | n | % | n | % | Median Age of Seizure Onset (days) | P-value |

| Brain involvement | Unilateral | 53 | 75.5 | 17 | 77.3 | 199.0 | .006 |

| Bilateral | 17 | 24.3 | 5 | 22.7 | 112.0 | ||

| Skin involvement | None | 10 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 228.0 | .005 |

| Unilateral | 33 | 47.1 | 15 | 68.2 | 261.0 | ||

| Bilateral | 27 | 38.6 | 7 | 31.8 | 123.0 | ||

| Eye Involvement | None | 34 | 48.6 | 13 | 59.1 | 198.0 | .272 |

| Unilateral | 23 | 32.9 | 6 | 27.3 | 180.0 | ||

| Bilateral | 13 | 18.6 | 3 | 13.6 | 110.0 | ||

| Total SWS involvement | 1 | 10 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 228.0 | .057 |

| 2 | 14 | 20.0 | 11 | 50.0 | 267.5 | ||

| 3 | 19 | 27.1 | 2 | 9.1 | 180.0 | ||

| 4 | 16 | 22.9 | 7 | 31.8 | 140.5 | ||

| 5 | 3 | 4.3 | 0 | 0 | 62.0 | ||

| 6 | 8 | 11.4 | 2 | 9.1 | 84.5 | ||

Figure 5.

Bar graph shows a significantly higher percentage of subjects with bilateral brain involvement in the presymptomatically treated group, as compared to subjects in the standard treatment group.

Table 3. Comparison between Treatment Groups and Sturge-Weber Extent.

| Standard Treatment Group | Presymptomatic Treatment Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sturge-Weber Extent | Extent of Involvement | n | % | n | % | P-value |

| Brain involvement | Unilateral | 50 | 83.3 | 20 | 62.5 | .026 |

| Bilateral | 10 | 16.7 | 12 | 37.5 | ||

| Skin involvement | None | 10 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | .004 |

| Unilateral | 33 | 55.0 | 15 | 46.9 | ||

| Bilateral | 17 | 28.3 | 17 | 53.1 | ||

| Eye Involvement | None | 31 | 51.7 | 16 | 50.0 | .836 |

| Unilateral | 19 | 31.7 | 10 | 31.3 | ||

| Bilateral | 10 | 16.7 | 6 | 18.8 | ||

| Total SWS involvement | 1 | 10 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | .023 |

| 2 | 16 | 26.7 | 9 | 28.1 | ||

| 3 | 16 | 26.7 | 5 | 15.6 | ||

| 4 | 10 | 16.7 | 13 | 40.6 | ||

| 5 | 3 | 5.0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6 | 5 | 8.3 | 5 | 15.6 | ||

The binary logistic regression model correctly predicted seizure onset by two in 77.2% of participants, including 90% of those who experienced seizure onset and 36% of those who did not. Model estimates suggested that standard post-symptomatically treated subjects were 9.24 times more likely to have seizure onset by 2 years (p < .001, 95% CI 2.74 to 31.19). In this regression model, females were 3.67 times more likely to have seizure onset by 2 years (p = .029, 95% CI 1.139 to 11.834). Extent of brain and skin involvement were not significant in explaining seizure onset by 2 years in the model estimate.

Presymptomatic treatment and Other Neurologic Outcome at Two Years of Age

Total SWS Neuroscore demonstrated a trend for better neurologic outcome at 2 years ± 3 months in the presymptomatically treated group (see Figure 6); p = .064. Hemiparesis sub-scores were significantly better in the presymptomatically treated subjects compared to the non-presymptomatically treated subjects (see Figure 6; p = .045).

Figure 6.

Box-plots for total SWS Neuroscore and hemiparesis sub-score at 2 years of age. In the presymptomatically treated group there is a trend for a lower total neuroscore and a significantly lower hemiparesis subscore (where lower scores indicate better neurologic function), when compared to the standard treatment group.

EEG Abnormality and Seizure Onset by Two Years of Age

In the entire dataset (both presymptomatic and standard treatment groups; see Supplemental Table 3), subjects who had seizure onset before two years of age were also significantly more likely to have an EEG that reported either slowing, epileptiform discharges, or EEG seizures, n = 14 EEGs (10 subjects). Ninety-three percent (13/14) of EEGs had seizure onset by two years of age, X2 (1, 56) = 10.6, p = .001. This data results in a sensitivity of 41.9% and a specificity of 96%, for seizure onset by two years of age, and with 90% prevalence of seizure onset by two years, these clinical EEG reports have a positive predictive value of 99% and a negative predictive value of 16%. Adding asymmetric or decreased voltage as a factor did not increase the predictive value.

The time between the first reported abnormal EEG and seizure onset, ranged from 6–516 days; median=67 days); 6 (5 subjects) of these EEGs were from presymptomatically treated subjects. Only three subjects with these abnormalities had more than one EEG performed before seizure onset; of these, two subjects had consistently reported slowing. All 3 EEGs (2 subjects) with reported subclinical EEG seizures prior to clinical seizure onset experienced clinical seizure onset before 2 years.

Discussion:

We aimed to study the key question of whether presymptomatic treatment can effectively delay seizure onset in SWS and result in improved neurological outcome. Without intervention, about 90% of patients with SWS brain involvement will experience seizure onset by 2 years of age [18]. The results of this multi-site, and relatively large sample (N=92) extension of a prior single site and small sample (N=15) study [29] are consistent with previously reported studies; 88% of the subjects, in the group receiving treatment only after seizure onset (e.g. standard care at this time), developed clinical seizures by 2 years. Only about half of the 32 presymptomatically treated patients with SWS brain involvement had seizure onset by 2 years of age, suggesting that presymptomatic treatment is beneficial in delaying seizure onset. This data supports our previous pilot case series [29]. In addition, the current study results indicate that neurologic status at two years of age may be better in those who were presymptomatically treated, as compared to children with SWS brain involvement receiving standard, post-symptomatic treatment; this has not been previously reported. While long term cognitive, epilepsy, and neurologic data is still needed in these patients, the data reported here supports offering presymptomatic treatment to patients with extensive brain involvement.

Early seizure onset is associated with worse long-term neurocognitive outcomes and seizure activity in Sturge-Weber Syndrome [13, 22]. This is attributed potentially to the cortical-subcortical structure abnormalities causing impaired blood flow. Onset of seizures can further disrupt blood flow and cause cortical damage, which in turn worsens long-term outcomes; potentially as a result, cognitive impairments by school age are common in SWS [10, 38]. Early seizure onset is associated with status epilepticus, therefore, seizures in SWS further worsen blood flow and venous strokes or stroke-like episodes associated with seizures are common in young children with SWS [18, 22, 39]. A significant delay in seizure onset may allow for more normal neurological development in infants with Sturge-Weber Syndrome brain involvement, and may result in decreased brain injury and neurologic impairment [29, 30].

The most commonly received post-symptomatic ASM, given to infants and young children at our centers for SWS, is either oxcarbazepine or levetiracetam in combination with low dose aspirin (about 3–5 mg/kg/day). These were also the most commonly used presymptomatic treatment methods in our patients; moderate doses of ASM between 35–45 mg/kg/day have been most effective. The combination of ASM and low-dose aspirin aims to address the blood flow issues and seizures underlying brain injury in SWS. Oxcarbazepine has been noted to be associated with better seizure control than levetiracetam in SWS [40]; while this difference did not achieve significance in our analyses, a higher percentage of patients remained seizure free by two years on oxcarbazepine and low dose aspirin, than those on levetiracetam and low dose aspirin. Further evaluation of oxcarbazepine as a pre-symptomatic treatment in SWS is needed, especially in light of the widespread use of levetiracetam in the USA as a first-line treatment. Low-dose aspirin use in SWS is associated with decreased seizures and decreased stroke-like episodes [41–43]. Side effects associated with low dose aspirin use includes increased bruising and bleeding of the gums or nosebleeds [41–43]; serious side effects of low-dose aspirin use are rarely reported. With dosage adjustments, most children with SWS tolerate low dose aspirin well [41, 42], however this approach is still controversial amongst some centers and clinicians.

Historically, a greater extent of brain involvement in Sturge-Weber syndrome is associated with an earlier age of seizure onset [16–18], and data from the current study also indicates that bilateral brain involvement is associated with an earlier age of seizure onset. Early age of seizure onset is associated with intellectual disability and great seizure severity [22]. PWB extent is also associated with earlier age of seizure onset [16] and our data indicated this as well. The presymptomatic use of low dose aspirin and antiepileptic medications may be most beneficial in patients with extensive unilateral involvement or bilateral involvement who have the highest risk of seizures and neurocognitive deficits. Typically, at both our sites, parents of patients with 3 or more lobes of SWS brain involvement are offered presymptomatic treatment. Furthermore, there was a significantly higher percent of bilaterally involved subjects in the presymptomatic treatment group; providers typically target subjects with more extensive brain involvement for presymptomatic treatment, but this does suggest that later seizure onset in this group is likely not due to less SWS brain involvement. A single prior study indicated that family history of seizures and greater extent of skin involvement may impart a higher risk of early seizure onset [16], however results from our data was not consistent with this finding. Extent of PWB and brain involvement may be useful markers for prognosis, and may aid in the identification of subjects who may benefit the most from presymptomatic treatment. Further studies are needed to determine what combination of factors best predict the onset of seizures by two years of age.

EEG abnormalities and quantitative EEG have been used to screen for SWS brain involvement in high risk infants [44, 45]; the question of whether EEG abnormalities can predict the age of seizure onset by 2 years of age has not been previously evaluated. Our EEG data analysis suggests that the presence of slowing, epileptiform discharges, or subclinical seizures on EEG exam is strongly associated with onset of seizures by two years of age. Importantly, the time between obtaining the EEG, and the MRI where abnormality is first detected and seizure onset, suggests that in most cases, clinicians have several weeks to initiate pharmacological intervention. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and assess the timing and frequency of EEGs to predict seizure onset.

Much like patients with SWS, patients with tuberous sclerosis complex are at a high risk of developing epilepsy and these patients have been shown to benefit from presymptomatic diagnosis and treatment [46, 47]. Presymptomatic treatment in tuberous sclerosis complex has been shown to improve seizure control and reduce the risk of intellectual disability [48]. Treatment during the presymptomatic phase in tuberous sclerosis complex sets precedence for presymptomatic treatment in other developmental epilepsy disorders, like SWS, where a high percentage of patients will have seizure onset in the first few years of life, and where early age of seizure onset has been repeatedly associated with worse neurologic and developmental outcome [49–51]. More studies are needed to establish that presymptomatic treatment improves long-term neurologic and cognitive outcome in SWS. In the meantime, however, these results strongly suggest that presymptomatic treatment can significantly delay seizure onset in these infants.

We propose, therefore, that for now infants with a high risk facial PWB be seen by a Sturge-Weber specialist so that early diagnosis of brain involvement on MRI can be made and presymptomatic treatment considered. Based on this is preliminary data, EEG may be considered to aid prediction of seizure onset by 2 years, and along with obtaining a non-sedated, non-contrast MRI in very young infants, may aid timing for initiation of treatment. However, there is an urgent need for more extensive prospective trials to determine whether EEGs can aid in the identification of those patients who will most benefit from presymptomatic treatment, and provide clinically useful information, such as when seizure onset is expected and the optimal presymptomatic dosing of medication.

Limitations:

While this study is the first to present the results of presymptomatic treatment, from more than one center and from a comparatively large number of subjects, this is a retrospective study with the limitations inherent in that study design. Physicians typically recommended presymptomatic treatment in cases where there were 3 or more lobes of involvement and caregivers decided whether treatment would be initiated. SWS is a rare disease making prospective clinical trial studies very challenging; nevertheless, additional prospective studies are needed. This study is also limited by not having longer-term neuropsychological data to analyze as an additional outcome measure to assess whether delaying seizure onset results in improved neurocognitive outcomes. More study of the long-term efficacy of presymptomatic treatment is necessary. Low sample size for specific types of ASM also limits our ability to identify whether certain ASMs are more effective than others are when presymptomatically treating infants with SWS. The retrospective nature of the study led to fact that the therapeutic design was inconsistent and we could only faithfully document the inconsistency in the treatments. Future larger, prospective, and randomized studies are needed to systematically compare different presymptomatic treatment strategies. Due to the nature of this study, the exact age when patients first had the initiation of monitoring for possible SWS was not readily available for all subjects. Nevertheless, median age at first visit to our centers was statistically younger in the presymptomatically treated group. The majority of the subjects in this study were white. As we currently understand it, SWS has no known race predilection. This important limitation likely reflects disparities in referral patterns, as well as in the ability of patients to travel to these tertiary care centers of SWS expertise. Only subjects who provided consent to have their records studied were included in this study, and this introduces a self-selection bias that could also be a factor, especially in whether a family consented to start pre-symptomatic treatment. Further studies are needed to determine whether PWB on darker-skinned infants are less likely to be readily apparent, and to trigger appropriate referrals. Understanding these underlying disparities will be important to addressing them and insuring that all children have access to optimal medical care.

Future Directions:

Prospective, randomized studies on presymptomatic treatment are needed to conclude that treatment improves neurocognitive outcome in SWS. Study to confirm biomarkers for seizure onset is also necessary in this population. Large-scale, multi-site, and comprehensive data will be needed to power multivariate analysis and data-driven biomarker discovery. Future studies, that combine clinical factors and MRI variables, are planned to predict which patients will most benefit from presymptomatic treatment. If it is proven that early seizure onset results in worse neurologic outcome, and that presymptomatic treatment both delays age of seizure onset and improves neurodevelopmental outcome, then early identification of Sturge-Weber syndrome brain involvement and subsequent intervention of those at high risk for seizure activity would become a medical imperative.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NIH/NCATS) R21 TR004265 (Ou), and the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center at Kennedy Krieger (IDDRC). We thank Pooja Vedmurthy for initial subject selection. We acknowledge the support and interactions with the rest of the Boston-KKI SWS Presymptomatic Working Group, including: Mustafa Sahin, MD, Boston Children’s Hospital. P. Ellen Grant, MD, Boston Children’s Hospital. Katrina Boyer, PhD, Boston Children’s Hospital. Masanori Takeoka, MD, Boston Children’s Hospital. Joshua Ewen MD, Kennedy Krieger Institute Epilepsy. Teressa Garcia Reidy, MS, OTR/L, Kennedy Krieger Institute Occupational Therapy. Stacy Suskauer MD, Kennedy Krieger Institute Medical Rehabilitation. Doris D. M. Lin, MD PhD, Neuroradiology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Neuroradiology. We thank patients and families for participating in this research.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Anne Comi, Anna Pinto and Eric Kossoff are members of the ACNS editorial board.

References

- 1.Comi AM, Update on Sturge-Weber syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, quantitative measures, and controversies. Lymphat Res Biol, 2007. 5(4): p. 257–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shirley MD, et al. , Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med, 2013. 368(21): p. 1971–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galeffi F, et al. , A novel somatic mutation in GNAQ in a capillary malformation provides insight into molecular pathogenesis. Angiogenesis, 2022. 25(4): p. 493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang L, et al. , Somatic GNAQ Mutation is Enriched in Brain Endothelial Cells in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol, 2017. 67: p. 59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakashima M, et al. , The somatic GNAQ mutation c.548G>A (p.R183Q) is consistently found in Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Hum Genet, 2014. 59(12): p. 691–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rihani HT, et al. , Incidence of Sturge-Weber syndrome and associated ocular involvement in Olmsted County, Minnesota, United States. Ophthalmic Genet, 2020. 41(2): p. 108–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ha A, et al. , Incidence of Sturge-Weber Syndrome and Risk of Secondary Glaucoma: A Nationwide Population-based Study Using a Rare Disease Registry. Am J Ophthalmol, 2023. 247: p. 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higueros E, et al. , Sturge-Weber Syndrome: A Review. Actas Dermosifiliogr, 2017. 108(5): p. 407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, et al. , Cortical calcification in Sturge-Weber Syndrome on MRI-SWI: relation to brain perfusion status and seizure severity. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2011. 34(4): p. 791–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin DD, et al. , Dynamic MR perfusion and proton MR spectroscopic imaging in Sturge-Weber syndrome: correlation with neurological symptoms. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2006. 24(2): p. 274–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aylett SE, et al. , Sturge-Weber syndrome: cerebral haemodynamics during seizure activity. Dev Med Child Neurol, 1999. 41(7): p. 480–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Namer IJ, et al. , Subtraction ictal SPECT co-registered to MRI (SISCOM) in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Clin Nucl Med, 2005. 30(1): p. 39–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powell S, et al. , Neurological presentations and cognitive outcome in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2021. 34: p. 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poliner A, et al. , Port-wine Birthmarks: Update on Diagnosis, Risk Assessment for Sturge-Weber Syndrome, and Management. Pediatr Rev, 2022. 43(9): p. 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dymerska M, et al. , Size of Facial Port-Wine Birthmark May Predict Neurologic Outcome in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. J Pediatr, 2017. 188: p. 205–209 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Day AM, et al. , Physical and Family History Variables Associated With Neurological and Cognitive Development in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol, 2019. 96: p. 30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bebin EM and Gomez MR, Prognosis in Sturge-Weber disease: comparison of unihemispheric and bihemispheric involvement. J Child Neurol, 1988. 3(3): p. 181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sujansky E and Conradi S, Sturge-Weber syndrome: age of onset of seizures and glaucoma and the prognosis for affected children. J Child Neurol, 1995. 10(1): p. 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugano H, et al. , Extent of Leptomeningeal Capillary Malformation is Associated With Severity of Epilepsy in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol, 2021. 117: p. 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang S, et al. , Characteristics, surgical outcomes, and influential factors of epilepsy in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Brain, 2022. 145(10): p. 3431–3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kossoff EH, Ferenc L, and Comi AM, An infantile-onset, severe, yet sporadic seizure pattern is common in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Epilepsia, 2009. 50(9): p. 2154–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luat AF, et al. , Cognitive and motor outcomes in children with unilateral Sturge-Weber syndrome: Effect of age at seizure onset and side of brain involvement. Epilepsy Behav, 2018. 80: p. 202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juhasz C, Predicting and Preventing Epilepsy in Sturge-Weber Syndrome? Pediatr Neurol Briefs, 2016. 30(11): p. 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juhasz C, et al. , White matter volume as a major predictor of cognitive function in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Arch Neurol, 2007. 64(8): p. 1169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pilli VK, et al. , Clinical and metabolic correlates of cerebral calcifications in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol, 2017. 59(9): p. 952–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harmon KA, et al. , Quality of Life in Children With Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol, 2019. 101: p. 26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosnyak E, et al. , Predictors of Cognitive Functions in Children With Sturge-Weber Syndrome: A Longitudinal Study. Pediatr Neurol, 2016. 61: p. 38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raga S, et al. , Developmental and epileptic encephalopathies: recognition and approaches to care. Epileptic Disord, 2021. 23(1): p. 40–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day AM, et al. , Hypothesis: Presymptomatic treatment of Sturge-Weber Syndrome With Aspirin and Antiepileptic Drugs May Delay Seizure Onset. Pediatr Neurol, 2019. 90: p. 8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ville D, et al. , Prophylactic antiepileptic treatment in Sturge-Weber disease. Seizure, 2002. 11(3): p. 145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kotulska K, et al. , Prevention of Epilepsy in Infants with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex in the EPISTOP Trial. Ann Neurol, 2021. 89(2): p. 304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vedmurthy P, et al. , Study protocol: retrospectively mining multisite clinical data to presymptomatically predict seizure onset for individual patients with Sturge-Weber. BMJ Open, 2022. 12(2): p. e053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smegal LF, et al. , Cannabidiol Treatment for Neurological, Cognitive, and Psychiatric Symptoms in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol, 2022. 139: p. 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan EH, et al. , Cannabidiol Treatment for Refractory Seizures in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol, 2017. 71: p. 18–23 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sebold AJ, et al. , Sirolimus Treatment in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol, 2021. 115: p. 29–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kavanaugh B, et al. , [Formula: see text]Intellectual and adaptive functioning in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Child Neuropsychol, 2016. 22(6): p. 635–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatfield LA, et al. , Quantitative EEG asymmetry correlates with clinical severity in unilateral Sturge-Weber syndrome. Epilepsia, 2007. 48(1): p. 191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miao Y, et al. , Clinical correlates of white matter blood flow perfusion changes in Sturge-Weber syndrome: a dynamic MR perfusion-weighted imaging study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2011. 32(7): p. 1280–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Juhasz C, Toward a better understanding of stroke-like episodes in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2020. 25: p. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaplan EH, et al. , Anticonvulsant Efficacy in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol, 2016. 58: p. 31–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lance EI, et al. , Aspirin use in Sturge-Weber syndrome: side effects and clinical outcomes. J Child Neurol, 2013. 28(2): p. 213–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bay MJ, et al. , Survey of aspirin use in Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Child Neurol, 2011. 26(6): p. 692–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roach ES, et al. , Management of stroke in infants and children: a scientific statement from a Special Writing Group of the American Heart Association Stroke Council and the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Stroke, 2008. 39(9): p. 2644–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gill RE, et al. , Quantitative EEG improves prediction of Sturge-Weber syndrome in infants with port-wine birthmark. Clin Neurophysiol, 2021. 132(10): p. 2440–2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ewen JB, et al. , Use of quantitative EEG in infants with port-wine birthmark to assess for Sturge-Weber brain involvement. Clin Neurophysiol, 2009. 120(8): p. 1433–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chung CWT, et al. , Early Detection of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: An Opportunity for Improved Neurodevelopmental Outcome. Pediatr Neurol, 2017. 76: p. 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Saint Martin A, Napuri S, and Nguyen S, Tuberous sclerosis complex and epilepsy in infancy: prevention and early diagnosis. Archives de Pédiatrie, 2022. 29(5, Supplement): p. 5S8–5S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jóźwiak S, et al. , Antiepileptic treatment before the onset of seizures reduces epilepsy severity and risk of mental retardation in infants with tuberous sclerosis complex. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 2011. 15(5): p. 424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aronica E, et al. , Epileptogenesis in tuberous sclerosis complex-related developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Brain, 2023. 146(7): p. 2694–2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Capal JK, et al. , Influence of seizures on early development in tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Behav, 2017. 70(Pt A): p. 245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nabbout R, et al. , Epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis complex: Findings from the TOSCA Study. Epilepsia Open, 2019. 4(1): p. 73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.