Abstract

The existing data demonstrate that probiotic supplementation affords protective effects against neurotoxicity of exogenous (e.g., metals, ethanol, propionic acid, aflatoxin B1, organic pollutants) and endogenous (e.g., LPS, glucose, Aβ, phospho-tau, α-synuclein) agents. Although the protective mechanisms of probiotic treatments differ between various neurotoxic agents, several key mechanisms at both the intestinal and brain levels seem inherent to all of them. Specifically, probiotic-induced improvement in gut microbiota diversity and taxonomic characteristics results in modulation of gut-derived metabolite production with increased secretion of SFCA. Moreover, modulation of gut microbiota results in inhibition of intestinal absorption of neurotoxic agents and their deposition in brain. Probiotics also maintain gut wall integrity and inhibit intestinal inflammation, thus reducing systemic levels of LPS. Centrally, probiotics ameliorate neurotoxin-induced neuroinflammation by decreasing LPS-induced TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling and prevention of microglia activation. Neuroprotective mechanisms of probiotics also include inhibition of apoptosis and oxidative stress, at least partially by up-regulation of SIRT1 signaling. Moreover, probiotics reduce inhibitory effect of neurotoxic agents on BDNF expression, on neurogenesis, and on synaptic function. They can also reverse altered neurotransmitter metabolism and exert an antiamyloidogenic effect. The latter may be due to up-regulation of ADAM10 activity and down-regulation of presenilin 1 expression. Therefore, in view of the multiple mechanisms invoked for the neuroprotective effect of probiotics, as well as their high tolerance and safety, the use of probiotics should be considered as a therapeutic strategy for ameliorating adverse brain effects of various endogenous and exogenous agents.

1. Gut-brain axis and its role in neurotoxicity (Introduction)

The human intestine is colonized with approximately 1014 bacterial cells. In an adult human, the weight of the bacterial biomass accounts for 1.5–2.0 kg (Schroeder and Bäckhed, 2016), and the bacterial density significantly increases from the proximal intestine with 103 cells per each gram of intestinal content in the duodenum to 1012 cells/g in colon (Sekirov et al., 2010). The gut microbiome represented by bacterial genome was estimated to contain more than 5 million genes. Therefore, both the number of cells and the size of genome of the gut microbiota were suspected to exceed that of the host organism (Sommer and Bäckhed, 2013). However, more recent studies suggest only a slightly higher number of microbiomes genomes compared to that of humans (Chatterjee et al., 2022; Shoemaker et al., 2022; VanEvery et al., 2023). Due to a high number of cells and its metabolic activity, “normal” gut microbiota has a significant impact on host physiology. First, gut microbiota is involved in digestion (Rowland et al., 2018) and production of vitamins (Rudzki et al., 2021), as well as regulation of the development of intestinal epithelium and integrity of gut wall (Barbara et al., 2021). Concomitantly, the gut microbiota has various extraintestinal effects. Specifically, gut microbiota is involved in development and modulation of host immunity (Rooks and Garrett, 2016), also counteracting pathogenic microflora (Kamada et al., 2013). Moreover, the metabolic activity of gut microbiota has a significant impact on the skeletal (Cooney et al., 2021) and cardiovascular system (Tang et al., 2017), endocrine and reproductive systems (Qi et al., 2021). Given its wide spectrum of metabolic activities and its importance for the host organism, gut microbiota has been considered an endocrine organ (Clarke et al., 2014). As a consequence, dysregulation of gut microbiota was shown to contribute significantly to pathogenesis of various intestinal and extraintestinal diseases including obesity, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, and asthma, to name a few (Carding et al., 2015).

Brain function is also strongly dependent on gut microbiota due to the gut-brain axis (Cryan et al., 2019). The interaction between gut and brain takes place mainly through bacterial neuroactive metabolites. Specifically, neuroactive signaling molecules produced by gut microbiota may include de novo formed bacterial metabolites like lipopolysaccharide as a component of the bacterial cell wall or microbe-associated molecular pattern (MAMPs), as well as metabolites of host- and food-derived metabolites. Bacterial metabolism of dietary amino acids results in formation of neurotransmitters, polyamines, and phenols, to name a few. In turn, bacterial polysaccharide metabolism generates short-chain fatty acids, including butyrate. Microbial signals were shown to reach the brain through both systemic blood flow and vagal and afferent nerves (Mayer et al., 2022). In the brain, gut-derived neurotransmitters are involved in neuronal signaling (Jameson et al., 2020), whereas short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) were shown to modulate neuronal receptors, enteroendocrine signals, neuroimmune function, blood-brain barrier, and possess epigenetic effects (O’Riordan et al., 2022) with butyrate being one of the most significant modulators of neuronal activity (Stilling et al., 2016). In addition, lipopolysaccharide was shown to be a trigger of neuroinflammatory process (Batista et al., 2019). Metabolic activity and the formation of microbial metabolites is defined by taxonomic characteristics of gut microbiota. Butyrate production is characteristic for Roseburia, Eubacterium, Ruminococcus, certain Clostridium species, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzi to name a few (Chen et al., 2020). Lipopolysaccharide is a component of Gram-negative bacteria, inherent to the human gut by Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria phyla, including Enterobacteriaceae (Di Lorenzo et al., 2019). Therefore, gut dysbiosis results in altered formation of neuroactive metabolites contributing to neurological dysfunction and diseases (Rogers et al., 2016). Alterations in the gut-brain axis were shown to contribute to pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders like autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Hughes et al., 2018; Tizabi et al., 2023) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Cenit et al., 2017), anxiety and depression (Simpson et al., 2021), as well as dementia (Łuc et al., 2021).

In addition, gut microbiota was shown to play a regulatory role in neurotoxicity of various substances (Dempsey et al., 2019). It is proposed that the role of intestinal microflora in neurotoxicity of xenobiotics may be mediated by bacterial biotransformation of neurotoxicants, altered production of neuroactive microbial metabolites, disruption of intestinal barrier integrity, and mucosal dysfunction, although a much wider spectrum of mechanisms may be involved (Dempsey et al., 2019). Involvement of gut microbiota dysregulation in neurotoxicity upon exposure to persistent organic pollutants (Balaguer-Trias et al., 2022), pesticides (Giambò et al., 2021), ethanol (Leclercq et al., 2021) and several metals (Tinkov et al., 2021; Tizabi et al., 2023) was demonstrated.

Moreover, it has been shown that the gut-brain axis is disturbed by overload with endogenous metabolites possessing significant neurotoxicity. Specifically, gut dysbiosis is characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Hung et al., 2022) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Shen et al., 2021) that over express neurotoxic amyloid β (Aβ) (Reiss et al., 2018) and α-synuclein (Serratos et al., 2022), respectively, as well as phosphorylated tau protein that is common in both diseases (Lei et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2021). High glucose levels occurring during hyperglycemia in diabetes mellitus also possess neurotoxic effects (Tomlinson and Gardiner, 2008) that may be at least partially mediated by alteration of gut microbiota (Westfall et al., 2015). Finally, gut microbiota derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was also shown to possess neurotoxic effects through modulation of neuroinflammation (Zhao et al., 2019).

Modulation of gut microbiota for improvement of its diversity and taxonomic composition with probiotics was shown to modulate gut-brain axis (Ağagündüz et al., 2022). In view of the role of gut microbiota modulation in brain functioning, certain probiotics possessing modulatory effect on brain activity are also termed as psychobiotics (Choudhary et al., 2023). Specifically, several studies demonstrated beneficial effect of probiotics in treatment of neurodegenerative diseases (Ojha et al., 2023), depression (Huang et al., 2016), and even stroke (Zhong et al., 2021). In view of previous studies demonstrating the protective effect of probiotic against systemic toxicity of various pollutants (Chen, 2021) through their binding and degradation (Baralić et al., 2023), the protective effect of probiotic supplementation against endogenous and exogenous neurotoxic agents is of particular interest.

2. Exogenous neurotoxic agents

Existing data demonstrate that treatment with various probiotics affords neuroprotective effect against exogenous neurotoxic agents including toxic metals, alcohol, aflatoxin B1, organic pollutants, and propionic acid used as an animal model for ASD.

2.1. Lead (Pb)

Pb is a neurotoxic metal associated with a risk for Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Weisskopf et al., 2010), AD (Loef et al., 2011), ASD (Goel and Aschner, 2021; Tizabi et al., 2023), ADHD (Nicolescu et al., 2010), and cognitive decline (Boyle et al., 2021). The molecular mechanisms of Pb neurotoxicity involve mitochondrial dysfunction, redox imbalance, neuroinflammation, excitotoxicity, and ionic mimicry of calcium, to name a few (Virgolini and Aschner, 2021; Tizabi et al., 2023). Alteration in gut microbiota and dysregulation of gut-brain axis has also been shown to be involved in the neurotoxic effect of Pb (Sun et al., 2022; Tizabi et al., 2023).

Several studies demonstrated neuroprotective effect of probiotic supplementation in models of Pb overload. Specifically, Lactobacillus-based probiotic was shown to ameliorate Pb-induced brain necrosis, inflammation, gliosis, and loss of Purkinje cells in the exposed zebrafish (Margret et al., 2021). In addition, the adverse neurobehavioral effects and neuronal damage following Pb exposure in young rats were reversed by L. rhamnosus treatment, concomitantly increasing blood antioxidant enzyme activity and reduced glutathione (GSH) levels (Adli et al., 2023). Learning and memory dysfunction as well as brain oxidative stress induced by Pb exposure in mice were shown to be reduced by treatment with dietary supplements such as L. plantarum CCFM8661 enriched with polyphenols, vitamins, zinc, and calcium (Zhai et al., 2018).

The neuroprotective effect of probiotics is associated with improvement of gut microbiota taxonomic characteristics and metabolism in Pb-exposed animals. It has been shown that a probiotic containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium significantly reduced the adverse neurobehavioral effects of Pb exposure characterized by lower sucrose preference and higher immobility time during forced swim test and tail suspension test. These effects were associated with amelioration of the Pb-induced increase in abundance of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria at the phylum level and Ruminococcaceae, Clostridium, and s24–7 at the family level, as well as the Pb-induced decrease in the abundance of Firmicutes at the phylum level, and Lactobacillus, Spirochaetes, and Turicibacterales at the family level. In addition, intestinal acetic, propionic, butyric, isobutyric, valeric, and isovaleric acid levels were also increased by probiotic supplementation in Pb-exposed animals (Chen et al., 2022a,b).

Administration of L. plantarum WSJ-06 to Pb-exposed mice reduced anxiety and memory loss, as well as systemic inflammation by improving gut microbiota diversity associated with modulation of serum metabolomics, characterized by reduced LPS and L-kynurenine levels in parallel with elevated arachidonic acid, kynurenic acid O-hexside, vitamin B12, serotonin trehalose, as well as tryptophan hydroxylase (TH) (Li et al., 2022a,b).

In mice subjected to early-life Pb exposure, L. fermentum HNU312 significantly reduced Pb absorption and brain accumulation, decreased cerebral oxidative stress, microglia activation, and improved of blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity, altogether resulting in improved anxiety- and depression-like behaviors. Protective effects of probiotic were not limited to reduction in Pb absorption, but also prevention of Pb-induced disturbances in gut microbiota, and increases in SCFA-producing strains including Bacteroides uniformis, Parabacteroides distasonis, P. goldsteinii, and L. reuteri, amelioration of the inhibitory effect of Pb on intestinal propionic, isobutyric, butyric, isovaleric, and valeric acid production, as well as stimulation of intestinal acetate production (Zhang et al., 2023).

Treatment of Pb-exposed pregnant C57BL/6 mice with L. casei significantly reduced Pb levels in the blood of both dams and offspring, accumulation of Pb in the bone of offspring, as well as brain Pb levels in dams. Concomitantly, there was prevention of Pb-induced decreases in the relative abundance of Firmicutes and elevation of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria populations (Chen et al., 2023a,b). Reduction in brain Pb accumulation was also observed in Nile tilapia following L. plantarum supplementation (Zhai et al., 2017).

Furthermore, probiotic treatment in Pb-exposed animals was shown to modulate the pathways of Pb toxicity. Specifically, administration of L. rhamnosus significantly ameliorated Pb-induced learning and memory deficits, reduced brain gliosis and hippocampal IL-6 expression, improved dendritic spine density and reversed metal-induced down-regulation of hippocampal p-synapsin 1, vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1), and N-methyl D-aspartate receptor subtype 2B (NMDAR2B) mRNA expression in exposed rats. These effects were associated with improvement in gut microbiota richness and evenness and prevention of Pb-induced increase in the relative abundance of Staphylococcus, Prevotellaceae−UCG-001, and Alloprevotella, as well as Pb-induced decrease in intestinal occludin and tight junction protein 1 (TJP1) mRNA expression (Gu et al., 2022).

The protective effect of probiotic strains of Bifidobacteria, Lactobacilli, and S. thermophilus against Pb-induced memory impairments and dendritic spine alterations was associated with improvement of microbiota diversity and richness, reversal of Pb-induced increase in Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio and a decrease in relative abundance of Proteobacteria and Atinobacteria. At the genus level probiotic supplementation significantly increased the relative abundance of Helicobacter, Bifidobacterium, and Bacteroides, while decreasing that of Anaerovibrio, Ruminococcaceae_UCG-008, and Lactobacillus. The resulting changes in gut microbiota as well as a decrease in circulating interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels by probiotic treatment were associated with prevention of Pb-induced decrease in hippocampal histone H3 dimethylated at lysine 4 (H3K4me2), mediating the memory-protective effects of probiotic treatment (Xiao et al., 2020).

Administration of Limosilactobacillus fermentum SCHY34 to Pb acetate-exposed rats significantly reduced Pb accumulation in the brain, blood, liver, and kidney, as well as prevented Pb-induced hippocampal neuron damage, neurite shortening, oxidative stress, and reduction of brain Gln, glutamine synthetase (GS), acetylcholinesterase (AchE), norepinephrine (NE), cAMP, and adenylate cyclase (AC) levels, along with an increase in Glu content and monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity. The neuroprotective effect of the probiotic was associated with up-regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), c-fos, c-jun, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), superoxide dismutase (SOD-1/2), and B-cell lymphoma 2 protein (Bcl-2) mRNA expression, protein calmodulin (CaM), protein kinase A (PKA), N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors 1 and 2 (NMDAR1 and NMDAR2), synaptophysin (SYN), GSH, and phospho-cAMP response element-binding protein (p-CREB) expression, as well as down-regulation of Bax and Caspase 3 mRNA expression (Long et al., 2022). Similarly, neuroprotective effect of probiotic L. casei SYF-08 against Pb-induced toxicity was shown to be associated with enhancement of Pb excretion, as well as modulation of bile acid metabolism and down-regulation of intestinal farnesoid X receptor (FXR)/NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 (NLRP3) signaling (Chen et al., 2022a,b).

Taken together, the existing data demonstrate that probiotic treatment can significantly inhibit Pb absorption, ameliorate Pb-induced alterations of gut microbiota taxonomic and metabolite production, improve gut integrity, and reduce circulating LPS levels. These effects culminate in amelioration of systemic and neuronal inflammation, neuronal apoptosis and oxidative stress, synaptic dysfunction, and neurotransmitter dysregulation, hence providing neuroprotection against Pb-induced toxicity.

2.2. Aluminum (Al)

Aluminum (Al) is a known neurotoxic metal (Skalny et al., 2021), which may cause neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders (Lukiw et al., 2019). Studies have demonstrated the propensity of Al exposure to increase the accumulation and toxicity of amyloid beta, playing a potential role in pathogenesis of AD (Kawahara and Kato-Negishi, 2011). Al exposure, especially in combination with D-galactose, has been used to develop in vivo model of AD (Chiroma et al., 2018). Therefore, Al and Aβ, an endogenous neurotoxic molecule, share certain similarity in their toxicity that will be discussed later.

Several studies have demonstrated that probiotic treatment significantly ameliorated Al-induced behavioral and cognitive deficits through reduction of systemic and neuronal inflammation. Specifically, a combination of L. rhamnosus GG (LGG®) and Bifidobacterium BB-12 (BB-12®) significantly reduced anxiety-like behavior, spatial and recognition memory loss, as well as brain Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and IL-1β expression in AlCl3-exposed mice (Hamid and Zahid, 2023). In a similar model of Al exposure, probiotic treatment significantly reversed the Al-induced decrease in hippocampal BDNF expression and abolished the up-regulation of hippocampal and serum TNFα and IL-1β expression and hippocampal gliosis (Yuan et al., 2020).

In addition to inhibition of Al-induced neuroinflammation, probiotic administration reduced amyloid and tau accumulation. Specifically, supplementation with L. rhamnosus improved memory and learning abilities in AlCl3-exposed rats by reducing brain amyloid-β and phosphorylated tau accumulation, preventing TNFα, IL-1β, Bcl2, and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) mRNA expression, and inhibiting β-catenin and Wnt3a mRNA expression. However, the neuroprotective effect was shown to be more pronounced when probiotics were used in combination with Sesamol (Abu-Elfotuh et al., 2023). In a model of Al-exposed mice, treatment with L. plantarum CCFM639 probiotic reversed memory deficits by reducing brain Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 accumulation, brain TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels, normalized brain trace element levels (Fe, Zn, Mg, Ca), and increased brain tight junction protein (Occludin, Claudin-5, and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1)) expression (Yu et al., 2017). Supplementation with live and dead L. plantarum CCFM639 in Al-exposed C57BL/6 mice significantly reduced Al accumulation in the liver, but not in the brain, thus, preventing brain oxidative stress and dysregulation of brain Fe and Zn content. Live L. plantarum supplementation was more effective in reducing brain Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 accumulation and memory deficits as compared to dead cultures (Tian et al., 2017). Administration of L. plantarum probiotic was also shown to promote fecal excretion of Al along with modulation of gut microbiota in the exposed Nile tilapia (Yu et al., 2019).

Interestingly, in a model of AlCl3/D-galactose induced AD, preventive effect of L. plantarum DP189 supplementation was associated not only with prevention of AD-associated gut dysbiosis, but also with a reduction in neuronal damage, amyloid β accumulation, and tau phosphorylation through modulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway (Song et al., 2022). Furthermore, in a model of AD induced by D-galactose and AlCl3 exposure, treatment with L. plantarum MA2, reduced Aβ42 aggregation and neuroinflammation through Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/Myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MYD88)/NLRP3 signaling, effects that may be mediated by modulation of gut microbiota and probiotic metabolites, such as exopolysaccharides (Wang et al., 2022a,b).

Although the changes in gut microbiota taxonomic characteristics in AlCl3-exposed animals following probiotic treatment have yet to be fully determined, the existing data demonstrate strong protective effect of probiotics against Al neurotoxicity, at least partially by promoting Al excretion. Along with reduction of neuroinflammation, neuronal damage, leaky brain, and dysregulated brain trace element metabolism, probiotics have also been shown to reduce AlCl3-induced amyloidogenesis and tau phosphorylation.

2.3. Cadmium (Cd)

Cadmium (Cd) exposure was shown to be associated with increased risk of chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, cardiovascular diseases, as well as neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases (Satarug et al., 2023). In addition to oxidative stress, inflammation, geno-toxicity, and trace element dysregulation (Đukić-Ćosić et al., 2020), systemic effects of Cd exposure may be mediated secondary to altered gut microbiota composition and permeability (Tinkov et al., 2018). Specifically, alteration in gut microbiota following Cd exposure was linked to its neurotoxicity (Xu et al., 2023).

Supplementation with probiotic strains Lactobacillus and Acidobacillus was shown to ameliorate the inhibitory effect of CdCl2 exposure on murine brain BDNF levels and β-catenin gene expression, although the protective effect was more pronounced upon combination of probiotics with folic acid (Kadry and Megeed, 2018). In addition, Lactobacilli supplementation was shown to reduce both cerebral and intestinal aquaporin 4 mRNA expression in Cd-exposed rats which may underlie the protective effect of probiotics against leaky gut and brain edema (Rashed et al., 2022). Finally, the protective effect of certain probiotics including Bacillus coagulans and L. plantarum against Cd toxicity may be mediated by a reduction of metal absorption as well as an increase in its excretion (Majlesi et al., 2023). Moreover, enrichment of probiotic cultures may be considered an effective strategy to improve efficacy against Cd-induced toxicity. Specifically, administration of Se-enriched L. plantarum to Luciobarbus capito ameliorated memory loss by reducing brain Cd accumulation and modulating Cd-induced signaling pathways (Shang et al., 2022). Thus, it is reasonable to propose that administration of probiotics may be considered a protective strategy against Cd neurotoxicity, although further elucidation of the efficacy and the underlying mechanisms are required.

2.4. Mercury (Hg)

Analogous to Pb, mercury (Hg), due to its neurotoxic effects (Branco et al., 2021), has been considered a risk factor for brain diseases, including neurodegeneration (Chen et al., 2016) and neurodevelopmental disorders (Ijomone et al., 2020). The gut is also considered a potential target for both inorganic and methylmercury toxicity (Tian et al., 2023), and the impact of Hg-induced alterations in gut microbiota on brain was shown to be mediated by alterations in intestinal neuroactive metabolite production (Lin et al., 2020; Martins et al., 2021), corroborating the potential protective effects of probiotics against Hg toxicity (Ke et al., 2023). A probiotic based on S. thermophilus, L. acidophilus and B. bifidum was shown to possess neuroprotective effects in Hg-exposed rats by reducing cortical and cerebellar neuroinflammation, gliosis, and neurodegeneration (Abdel-Salam et al., 2018). Correspondingly, probiotic (S. thermophilus, L. acidophilus, and B. bifidum)-enriched mare milk was shown to ameliorate Hg-induced brain damage characterized by brain edema, neuronal chromatolysis and necrosis, as well as axonal demyelination (Abdel-Salam et al., 2010). Despite the limited evidence on the protective effects of probiotics against Hg neurotoxicity, several studies have demonstrated that modulation of gut microbiota by probiotics may reduce its toxic effects (Majlesi et al., 2017; Ke et al., 2023).

2.5. Arsenic (As)

As-induced gut dysbiosis is associated with altered brain metabolomics, indicative of the role of gut-brain axis in As-induced neurotoxicity (Wang et al., 2021). Maternal fecal microbiota transplantation significantly ameliorated As-induced neurobehavioral deficits and neuronal damage through modulation of gut-brain axis (Zhao et al., 2023), indicating that modulation of gut microbiota may be a protective strategy against As-induced neurotoxicity. A study by Park et al. (2017) demonstrated that administration of heat-killed Ruminococcus albus to As-exposed rats, reduced brain reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, prevented a decline in SOD activity and GSH levels, and prevented neuronal karyopyknosis in (Park et al., 2017). These effects may also be due to an increase in As excretion and a decrease in its accumulation in various organs (Luo et al., 2023).

2.6. Ethanol

Alcohol abuse is associated with a broad spectrum of pathological processes in the organism including alcohol-related brain damage (Zahr et al., 2011; Tizabi et al., 2021). It has been demonstrated that alcohol-induced dysregulation of gut-brain axis significantly contributes to ethanol-induced neurotoxicity through neuroinflammation and other mechanisms (Gorky and Schwaber, 2016). Therefore, it has been proposed that therapeutic interventions preventing dysbiosis by probiotic administration considered as protective strategies to attenuate alcohol-related brain damage (Li et al., 2022a,b).

In this regard, several studies have demonstrated neuroprotective effect of probiotic treatment in models of alcohol abuse. Specifically, L. casei-based probiotic significantly reduced ethanol-induced brain damage namely, edema, ischemic neuronal injury, and gliosis in rats (Soleimani et al., 2022). Probiotic treatment was also shown to improve memory in a model of ethanol-exposed rats (Hadidi Zavareh et al., 2020). Concomitantly, treatment with L. rhamnosus GG significantly reduced ethanol-induced neurobehavioral alterations and neuronal damage in zebrafish, at least partially by improvement the gut integrity (Aparna and Patri, 2023). In addition, treatment with BIOTICS (Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria) probiotic significantly attenuated anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors as well as stress levels in ethanol-exposed rats. This was postulated to be due to prevention of neuronal damage and improvement of synaptic function as evidenced by higher expression of glutamate receptor 1 (GluA1), postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD-95), and synaptophysin (SYP) proteins. The neuroprotective effects of this probiotic were also associated with reduction of ethanol-induced gut dysbiosis, increase in intestinal permeability and systemic LPS levels (Yao et al., 2023).

The neuroprotective effects of probiotics are mediated by inhibition of oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress, as well as proinflammatory signaling. Specifically, L. plantarum culture supernatant was shown to ameliorate brain damage and reduction in synaptic proteins SPD-95, synapsin-1, and synaptophysin in ethanol-exposed rats by reducing brain endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) with down-regulation of glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), phosphorylated protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), and phosphorylated inositol requiring-enzyme 1 alpha (IRE1α), as well as improvement of Nrf2, SOD2, pCREB (S133) and BDNF protein expression in hippocampus (Xu et al., 2022). Similar findings were obtained upon treatment with Acetobacter pasteurianus BP2201, which significantly reversed alcohol-induced cognitive decline and hippocampal damage in mice through improvement of gut microbiome and metabolome. Moreover, the probiotic resulted in up-regulation of hippocampal extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), CREB, BDNF, and tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) mRNA expression, and inhibition of NLRP3 mRNA expression in hippocampus (Wen et al., 2023).

Taken together, these existing data demonstrate that a variety of factors mediate probiotic effects in countering alcohol-induced toxicity and its behavioral consequences. These include improvement in gut microbiota, reduction of gut wall permeability, inhibition of systemic and neuronal inflammation, modulation of antioxidant system as well as amelioration of synaptic dysfunction.

2.7. Propionic acid (PPA)

According to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), propionic acid (PPA) is considered generally safe for humans and other organisms (Gad, 2014). However, intracerebroventricular administration of PPA was shown to possess significant neurotoxicity, resulting in development of autism-like behaviors and pathological features, demonstrating its usefulness as a rodent model for ASD (Shultz et al., 2015). Moreover, it has been proposed that gut microbiota-derived PPA may contribute to autism-like behavioral alterations (De Angelis et al., 2015). Given the role of gut dysbiosis and impaired gut-brain axis functioning in the pathogenesis of ASD (Hughes et al., 2018; Tizabi et al., 2023), as well as existing evidence demonstrating beneficial effect of probiotics in management of ASD (Tan et al., 2021), several studies have addressed the effect of probiotic administration in ameliorating PPA neurotoxicity.

In hamsters, the significant reduction in brain Mg and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels, and the increased glutamate/GABA ratios induced by propionic acid or clindamycin were ameliorated by treatment with probiotic mixture of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli. These mixtures further reduced the abundance of Clostridia and Candida albicans in the gut (El-Ansary et al., 2018). Correspondingly, probiotic treatment, not only increased brain GABA levels, but also ameliorated PPA-induced decline in GABA receptors A, B, and G (GABARA, GABARB, and GABARG) expression in rats (Bin-Khattaf et al., 2022). Furthermore, probiotic treatment significantly reduced cerebral caspase 3, caspase 7, IL-1β, IL-8, as well as heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) expression in both clindamycin and PPA-exposed mice, indicative of the protective effect of probiotic against neuronal apoptosis and inflammation in a model of ASD (Ben Bacha et al., 2021).

A combination of probiotic (Bifidobacteria, Lactobacilli, S. thermophilus) with bee pollen, as well as transplantation of healthy gut microbiota was shown to increase brain alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, β-endorphin, neurotensin, and substance P levels in a propionic acid-induced model of autism in rats (Alghamdi et al., 2022). This combination also reduced serum concentrations of zonulin and occludin proteins elevated by PPA treatment, indicative of the protective effect of the treatment against leaky gut in a rat model of ASD. Supplementation with probiotic and bee pollen also reduced the growth of Enterobacteriacea, Clostridium botulinum, and C. albicans in PPA-exposed rat intestine (Alonazi et al., 2023). A combination of bee pollen and probiotic also reduced PPA-induced neuroinflammation, characterized by elevated brain IL-1β, IL-8, and interferon γ (IFN-γ) levels, and a decrease in anti-inflammatory IL-10 content (Alonazi et al., 2022). Correspondingly, L. rhamnosus or yoghurt supplementation significantly reduced brain TNFα and IL-6 levels in PPA-induced model of ASD in rats (Alsubaiei et al., 2023).

Taken together, probiotic treatment affected key mechanisms associated with autistic behavior disorder induced by PPA treatment, including gut dysbiosis and increased gut wall permeability, dysregulated neurotransmitter metabolism, neuronal apoptosis, and neuroinflammation. However, in view of limitations of animal models of ASD (Silverman et al., 2022), it has yet to be determined whether the neuroprotective effect of probiotics will extend to clinically relevant studies in humans.

2.8. Aflatoxin B1

Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is a dietary toxin from the Aspergillus fungi, mainly A. flavus and A. parasiticus, that possesses a wide spectrum of toxicity (Rushing and Selim, 2019) including neurotoxic effects (Adedara et al., 2023). In view of the significant alterations of gut microbiota following AFB1 exposure (Zhou et al., 2019), it has been proposed that probiotics may ameliorate its neurotoxicity (Adedara et al., 2023). A probiotic containing Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli significantly reduced adverse neurobehavioral effects of AFB1 exposure characterized by anxiety and depression-like behaviors. This effect was associated with prevention of brain oxidative stress, gliosis, and neuronal loss including the loss of pyramidal cells (Aytekin Sahin et al., 2022). In addition, Lactobacilli-based probiotic was also shown to ameliorate AFB1-induced alterations in brain lipid profile by reducing brain cholesterol, triglyceride, and phospholipid content in the exposed rats (Ugbaja et al., 2020).

2.9. Organic pollutants

Exposure to various organic pollutants has been shown to induce adverse neurodevelopmental outcome in children, resulting in impaired psychomotor development, cognitive decline, and behavioral disorders (Berghuis et al., 2015). These effects are likely due to their neurotoxicity, including disruption of synaptic transmission and neurotransmitter metabolism (Latchney and Majewska, 2021), as well as neuroinflammation (Ahmed et al., 2021).

Perfluorinated chemicals, including perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS) were shown to possess neurotoxic effects (Slotkin et al., 2008). In view of previous indications of PFBS-induced alterations in gut microbiome (Chen et al., 2018) and metabolome (Chen et al., 2023a,b), it has been proposed that modulation of the gut-brain axis may reduce PFBS neurotoxicity.

Treatment with L. rhamnosus has been shown to reverse the increase in brain choline and epinephrine, as well as a decrease in serotonin level and down-regulation of mbp gene induced by PFBS exposure in zebrafish. L. rhamnosus also improved bile acid levels and transcription of genes involved in bile acid synthesis, decreased genomic DNA methylation, while enhancing its deme-thylation (Hu et al., 2022). In addition, probiotic supplementation was shown to reshape gut neurotransmitter levels in PFBS-exposed zebrafish (Liu et al., 2020).

Environmental pollution with micro- and nanoplastics was shown to cause significant health risk (Cortés et al., 2020). In addition to their own neurotoxic effects (Prüst et al., 2020), nanoplastics were found to act as the “Trojan horse” by increasing the bioaccessibility of other environmental pollutants (Sun et al., 2023). Dysregulation of gut-brain axis was also shown to contribute significantly to polystyrene nanoplastic-induced brain dysfunction (Teng et al., 2022), indicative of the potential protective effect of probiotic treatment (Bazeli et al., 2023). Yet, direct evidence seems to be lacking. Bifico probiotic (B, longum, L, acidophilus, and Enterococcus faecalis) significantly reduced hippocampal damage following polystyrene nanoplastics exposure by preventing down-regulation of hippocampal 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), GABA, BDNF, and CREB and up-regulating AChE and synuclein expression, as well as enhancing intestinal occludin, Claudin-1, and ZO-1 expression, proteins involved in keeping the gut wall integrity (Kang et al., 2023).

2.10. Other neurotoxic agents

Limited studies have also demonstrated the inhibitory effect of probiotic treatment on certain other agents possessing neurotoxicity, including isoflurane, acrylamide, as well as radiation.

Specifically, isoflurane, a volatile anesthetic, has been sown to afford neuroprotective effects in adults, while in newborns and elderly it may cause adverse neurological effects (Neag et al., 2020). Probiotic complex consisting of B. longum, L. bulgaricus, and S. thermophilus was shown to ameliorate the cognitive decline induced by prenatal isoflurane treatment at least partially by improving hippocampal BDNF levels. In view of association between the neurotoxic effects of isoflurane and decreases in gut microbiota diversity and richness, probiotic supplementation may counter this detrimental effect (Wang et al., 2022a,b).

Environmental pollution with acrylamide raises significant concerns due to its carcinogenic, reprotoxic, and neurotoxic effects (Tepe and Çebi, 2019). It has been demonstrated that both treatment and prevention with L. plantarum ATCC8014 significantly reduced lipid peroxidation, as well as reduced neuronal damage in hippocampus and cerebellum of acrylamide-exposed rats (Zhao et al., 2020).

In view of the significant alterations in gut-brain axis upon pesticide exposure, it has been proposed that probiotic treatment may reduce its neurotoxic effects, decreasing the risk of adverse neurological outcome including PD development, although direct evidence seems to be lacking (Rajawat et al., 2023).

In addition to neurotoxic chemicals, a single study demonstrated protective effect of probiotic treatment against radiation-induced brain damage. Specifically, supplementation with a complex probiotic (Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, S. thermophilus) was shown to improve intestinal integrity and reduce radiation-induced hippocampal neuronal death and neuroinflammation in the cortex (Venkidesh et al., 2023).

3. Endogenous neurotoxicants

In addition to exogenous neurotoxicants, probiotic treatment was shown to ameliorate toxicity of endogenous neurotoxic agents such as lipopolysaccharide, glucose, beta amyloid, α-synuclein and tau protein.

3.1. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

LPS is a structural component of Gram-negative bacteria cell membrane, and gut microbiota is a key source of circulating LPS in the organism (Di Lorenzo et al., 2019). An increase in systemic LPS level may be mediated by both gut dysbiosis and loss of gut wall integrity (Mohr et al., 2022). LPS is a potent inducer of inflammatory responses and neuroinflammation mainly through stimulation of TLR4 signaling and microglia activation (Batista et al., 2019). Given the key role of gut dysbiosis in elevation of systemic LPS levels, several studies addressed the protective effect of gut microbiota improvement by probiotic treatment against LPS neurotoxicity.

In view of the role of LPS in induction of inflammatory response, several studies addressed the protective effect of probiotic treatment against LPS-induced neurotoxicity. Specifically, administration of B. breve Bif11 in LPS-exposed mice significantly increased the relative abundance of Firmicutes, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, and Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio with a reduction in the number of Bacteroidetes, Clostridium, Klebsiella, Salmonella, and E. coli, in parallel with increased intestinal SFCA, specifically acetate and butyrate production. Together with improvement of gut permeability, these effects were associated with reduction in LPS-induced depressive behavior, improvement of neuronal viability and prefrontal BDNF levels, and reduction of C-reactive protein (CRP), matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2), IL-6, and TNFα protein expression in prefrontal cortex due to down-regulation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling (Sushma et al., 2023). Similarly, L. plantarum NK151 and B. longum NK173 treatment resulted in down-regulation of IL-1β, TNFα, and NF-κB and an increase in BDNF and IL-10 levels in the hippocampus, which coincided with cognitive improvements. These neuroprotective effects were associated with the reversal of LPS-induced increase in the relative abundance of Firmicutes and Deferribacteres, and reduction in the abundance of the Bacteroidetes population at the phylum level. Moreover, probiotic treatment was shown to increase the abundance of Muribaculaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Rikenellaceae, and Odoribacteraceae, as well as LPS-induced colitis (Lee et al., 2021). In this line, L. helveticus R0052 and B. longum R0175 treatment was also shown to ameliorate LPS-induced decline in hippocampal BDNF protein expression in rats (Mohammadi et al., 2019a,b). It was also shown that Lactobacilli-containing probiotic significantly improved the taxonomic characteristics of gut microbiota, reduced both circulating and hypothalamic, hippocampal, and prefrontal cortex mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα, and down-regulated TLR4 expression in male mice subjected to pubertal exposure to LPS. These neurochemical changes were associated with prevention of anxiety-like behavior and stress reactivity (Murray et al., 2019). A probiotic mixture containing Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria strains along with S. thermophilus was shown to improve exploratory behavior in LPS-exposed mice by increasing hippocampal neurogenesis and reducing microglia activation with subsequent up-regulation of IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα mRNA expression (Petrella et al., 2021). Interestingly, yeast-based probiotics also possess inhibitory effect on LPS-induced neuroinflammation. Specifically, S. cerevisiae-based probiotic prevented LPS-induced microglia activation and induced a shift to an anti-inflammatory phenotype characterized by down-regulation of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and inducible NO synthase (iNOS) mRNA expression and up-regulation of IL-10 and arginase mRNA expression (Armeli et al., 2022).

Another postulated mechanism for the protective effects of probiotic B. bifidum BGN4 and B. longum BORI strains is via increased indole-3-propionic acid production from tryptophan by intestinal microbiota. Specifically, in an in vitro model of LPS-induced BV-2 microglia cells probiotic treatment significantly reduced IL-1β mRNA and TNFα protein expression, while increasing BDNF and nerve growth factor (NGF) mRNA expression in SH-SY5Y cells (Kim et al., 2023).

In addition to modulation of neuroinflammation and improvement of BDNF-mediated neurogenesis, probiotic treatment was shown to prevent neuronal death upon LPS exposure. A mixture of L. helveticus R0052 and B. longum R0175 was shown to ameliorate LPS-induced hippocampal apoptosis by reducing Bax/Bcl2 ratio and protein expression of procaspase 3 and cleaved caspase 3 (Mohammadi et al., 2019a,b). Moreover, incubation of LPS-exposed SH-SY5Y cells with L. pentosus strain S-PT84 reduced IL-1β and IL-18 mRNA and protein expression, as well as prevented pyroptosis with reduction in cleaved caspase 1 and gasdermin D N-terminus (GSDMD-N) protein expression secondary to up-regulation of baculoviral IAP Repeat Containing 3 (BIRC3) mRNA and protein expression (Hu and Shao, 2022). It has been also demonstrated that L. reuterii probiotic treatment significantly diminished LPS-induced c-Fos expression in hippocampal Cornus Ammonis-1 and 3 (CA1 and CA3) regions as well as anxiety-like behaviors in male mice, whereas no significant effect of probiotic on c-Fos expression or behavior in LPS-exposed females was observed (Murray et al., 2020).

In a senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 (SAMP8) model characterized by elevated brain LPS levels, treatment with ProBiotic-4 (Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria strains) significantly reversed memory deficits associated with a decline in cerebral and cortical neurons and reduced synaptophysin expression. In addition, probiotic treatment ameliorated ageing-associated increase in the relative abundance of Proteobacteria (phylum), Pseudomonas (genus) and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group (genus), and a Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio in the gut, improved gut integrity by increasing the expression of claudin-1, occludin, and ZO-1 proteins, resulting in lower circulating and brain LPS levels. The latter was associated with inhibition of microglia activation subsequently leading to lower TNFα and IL-6 mRNA expression due to down-regulation of TLR4/NF-κB signaling, as well as reduced retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) expression (Yang et al., 2020). Correspondingly, administration of ProBiotic-4 was shown to reverse a significant increase in both intestinal and brain caspase 11, cleaved caspase 1, and alpha-protein kinase 1 (ALPK1) expression also preventing synaptic and neuronal injury as well as microglia activation in SAMP8 mice (Yang et al., 2023).

Probiotics also show protective effects against LPS-induced neurodegeneration. Specifically, supplementation with a combination of L. rhamnosus GG and B. animalis lactis significantly improved certain motor functions in an LPS-induced Parkinson’s disease (PD) model. Although this probiotic did not prevent LPS-induced dopaminergic degeneration and nigral microgliosis, a significant reduction of striatal microgliosis was observed in LPS-injected rats (Parra et al., 2023). In turn, treatment with B. bifidum and L. salivarius during pregnancy significantly prevented amyloidogenesis after maternal LPS exposure characterized by an increase in Aβ 1–42 accumulation in maternal brains, as well as elevation in amyloid precursor protein (APP), β and γ-secretase levels both in maternal and offspring brains. The probiotic increased BDNF mRNA expression both in maternal and offspring brains, and also ameliorated intestinal inflammation (Kar et al., 2022).

In regard to non-neurodegenerative conditions, administration of a probiotic strain Rouxiella badensis subsp. Acadiensis ameliorated LPS-induced depressive behavior in female mice by preventing a decrease in serotonin 1A (5HT1A) receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 and CA3 regions (Yahfoufi et al., 2021).

In a model of neuroendocrine toxicity, LPS exposure was shown to reduce glucocorticoid receptor expression in paraventricular nucleus and basolateral amygdala of male mice that was reversed by probiotic Lactobacilli strains (Smith et al., 2021).

Taken together, the existing data demonstrate that probiotic treatment significantly reverses LPS neurotoxicity by reducing TLR4-mediated NF-κB-dependent systemic and brain inflammation, prevents alterations in neurogenesis by improving BDNF expression, as well as ameliorates LPS-induced neuronal apoptosis and pyroptosis. These effects were also shown to be at least partially mediated by inhibition of LPS-induced amyloidogenesis.

3.2. Glucose

Glucose is an essential nutrient involved in a variety of metabolic processes. However, prolonged exposure of cells to high levels of glucose results in significant toxicity at least partially through induction of oxidative stress and formation of advanced glycation end-products (Kawahito et al., 2009). Along with vascular endothelial cells, pancreatic β cells, and kidneys, the brain is also considered highly sensitive to high glucose levels (Campos, 2012). The latter plays a role in the etiology of neurological complications in diabetics (Hamed, 2017). Dysregulation of gut microbiota in diabetes was shown to be involved not only in diabetes pathogenesis (Gurung et al., 2020), but also its neurological complications (Xu et al., 2017). It has been also demonstrated that gut microbiota modulates toxicity of advanced glycation end products (Aschner et al., 2023). Therefore, it has been proposed that probiotic treatment may be considered an effective strategy for diabetes management (Gomes et al., 2014). An earlier meta-analysis demonstrated a significant reduction of cardiovascular diabetes complications following probiotic supplementation (Hendijani and Akbari, 2018). Although clinical evidence of the beneficial effects of probiotics against diabetes-induced neurological damage is scant, it has been proposed that probiotics may provide a protective strategy against neurological damage in diabetes (Thakur et al., 2019).

A mixture of probiotic strains (Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria) has shown antidiabetic effects by reducing blood glucose levels and preventing a decline in circulating insulin level, as well as improved spatial learning and memory through stimulation of synaptic transmission in streptozotocin (STZ)-diabetic rats (Davari et al., 2013). In a model of STZ-induced diabetes L. reuteri GMNL-263 administration significantly reduced hippocampal neuronal damage by decreasing hippocampal TNFα, iNOS, and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) protein expression, inhibiting both Fas-dependent and mitochondrial apoptosis, as well as up-regulating insulin like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R)-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)- Glucose transporter (GLUT) 3 signaling (Lin et al., 2023). Administration of S. cerevisiae-based probiotic was shown to reduce brain oxidative stress in alloxan-diabetic rats (Aluwong et al., 2016).

Using a model of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion in diabetic mice, supplementation with Clostridium butyricum was shown not only to reduce blood glucose levels, but also ameliorated the cognitive decline and neuronal damage. This was postulated to be due to up-regulation Akt phosphorylation and inhibition of caspase-3-dependent apoptosis. Moreover, probiotics also reversed I/R-induced reductions in the relative abundance of Clostridium cluster XIVab, F. prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus, and increases in populations of Clostridium cluster XI, Clostridium cluster I, Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcus spp. (Sun et al., 2016).

Overall, the existing data support potential use of probiotics in management of diabetes-associated neuroinflammation, neuronal damage, and synaptic dysfunction, hence, countering neurological complications of diabetes mellitus.

3.3. Amyloid β (Aβ) and Alzheimer’s disease

Amyloid β is normally produced by the brain and some peripheral cells (Wang et al., 2017), yet its overproduction may lead to neurotoxicity, including AD pathogenesis (Broersen et al., 2010). Gut microbiota is known to be involved in regulation of amyloid beta metabolism (Pistollato et al., 2016). In turn, Aβ overaccumulation may affect gut microbiome and metabolome, providing an additional mechanism for AD pathogenesis (Qian et al., 2022). Indeed, AD patients are characterized by gut dysbiosis and dysregulation of the gut-brain axis (Hung et al., 2022). Therefore, modulation of gut microbiota has been considered a potential strategy to counteract Aβ neurotoxicity and AD pathogenesis (Guo et al., 2021; Lekchand Dasriya et al., 2022). In addition, probiotic treatment is expected to mitigate the neurotoxicity of another protein, tau, also involved in neurodegeneration (Flynn and Yuan, 2023). Results of meta-analysis demonstrated that probiotic treatment improved cognitive function in AD patients through modulation of inflammation and redox metabolism (Den et al., 2020). It has been also demonstrated that in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia treatment with probiotic (Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria strains) significantly reduced fecal zonulin content and increased the abundance of butyrate producing Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, also affecting tryptophan metabolism by increasing circulating kynurenine concentrations (Leblhuber et al., 2018).

Probiotic treatment was shown to reduce neurotoxic effects of Aβ. Specifically, treatment with B. bifidum and L. plantarum significantly reduced Aβ-induced alterations in learning and memory. Concomitantly, there was a reduction in CA1 neuronal death, and reversal of decreases in acetylcholine and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression. Interestingly, the neuroprotective effects of probiotic treatment were more pronounced upon combination with exercise training (Shamsipour et al., 2021). In rats intra-cerebroventricularly injected with Aβ(1−42), probiotic (Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria) treatment was shown to improve spatial learning and synaptic plasticity, also possessing hypolipidemic effect characterized by a reduction in circulating total cholesterol, triglycerides, and very low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (Rezaeiasl et al., 2019). Moreover, probiotic treatments in the same animal model of AD were shown to decrease the number of amyloid plaques in CA1 region, reduce hippocampal oxidative stress, improve cell morphology (Athari Nik Azm et al., 2018), and increase gut microbiota richness (Rezaei Asl et al., 2019).

The mechanisms of neuroprotective effects of probiotic treatment were evaluated in other models of AD. In App knock-in (KI) mice (AppNL-G-F) overproducing Aβ, supplementation with B. breve MCC1274 prevented memory loss, hippocampal Aβ40 and Aβ42 accumulation through an HIF1α-mediated increase in A Disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 (ADAM10), also known as α-secretase, activity despite the lack of probiotic effect on gut microbiota composition. In addition, probiotic treatment was shown to increase synaptic protein SYT and PSD95 protein expression in parallel with inhibition of microglial activation, as well as IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA expression, both in cortex and hippocampus (Abdelhamid et al., 2022a). The neuroprotective effect of B. breve MCC1274 administration was also observed in wild-type mice, characterized by reduction of hippocampal Aβ42 and phosphorylated tau levels via down-regulation of presenilin 1, which may be mediated by activation of Akt/GSK-3β pathway. In addition, B. breve MCC1274 treatment was shown to up-regulate hippocampal levels of synaptic proteins PSD-95, synaptotagmin (SYT), syntaxin, and SYP, as well as prevented microgliosis (Abdelhamid et al., 2022b). In another study using AppNL-G-F AD model, supplementation with VSL#3 probiotic (Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria strains and Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus), significantly increased gut microbiota diversity, reduced intestinal permeability and inflammation by up-regulating occludin protein levels and down-regulating IL-1β and Lipocalin protein levels in ileum (Kaur et al., 2020).

In 3xTg-AD mice, supplementation with Lab4P probiotic (Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria strains) significantly reduced cognitive decline and the decrease in synaptic plasticity as assessed by hippocampal spine density in both aged and HFD-fed animals. In HFD-exposed mice, however, probiotic supplementation also reduced neuroinflammation by down-regulating hippocampal IL-1β and TNFα mRNA expression. Moreover, probiotic metabolites from Lab4P-conditioned media improved cell viability in Aβ-exposed SH-SY5Y cells and reduced IL-6 mRNA expression (Webberley et al., 2023). It was also shown that the neuroprotective effect of B. breve MCC1274 metabolites may be mediated by down-regulation of perilipin 4 expression induced by oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y cells resulting in decreased lipid formation and IL-6 production (Bernier et al., 2023). In the same genetic model of AD, probiotic SLAB51 (Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, and S. thermophilus) treatment significantly increased brain sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) activity and expression with a subsequent decrease in p53 and RARβ acetylation, which is expected to result in reduced neuronal apoptosis and up-regulation of antiamyloidogenic α-secretase expression. In agreement with the role of SIRT1 in regulating Nrf2, it has been demonstrated that SLAB51 treatment reduces brain lipid and protein oxidation due to an increase in glutathione S-transferase (GST), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), catalase and SOD activity, as well as GSH levels (Bonfili et al., 2018). SLAB51 administration also reduced a cognitive decline in 3xTg-AD mice. This effect was associated with improved brain glucose homeostasis, up-regulation of glucose transporters (GLUT3, GLUT1) and insulin-like growth factor receptor β. On the other hand, there was reduced tau phosphorylation via AMPK/Akt signaling pathway modulation (Bonfili et al., 2020).

In other AD models, for example, D-galactose-induced AD, supplementation with L. plantarum, MTCC1325 significantly reduced spatial memory and behavioral impairments by decreasing the number of Aβ plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and improvement of acetylcholine levels through down-regulation of AChE activity (Nimgampalle and Kuna, 2017). Similarly, in a 5xFAD transgenic mouse model, treatment with a mixture containing L. casei along with Cuscuta australis seed extract and C. japonica Choisy seed extract reduced gut inflammation characterized by increased glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), TLR2, MyD88, C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2), CX3C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1), and NLRP3 expression (Ju et al., 2023). Moreover, in APP/PS1 mice, treatment with probiotic yeast S. boulardii significantly reduced neuronal damage and synaptic dysfunction, which were associated with microglia inactivation, mediated through TLR4- pathway. S. boulardii also significantly improved the maintenance of gut integrity, thus improving the gut-brain axis (Ye et al., 2022).

Taken together, probiotics, via manipulation of the gut microbiome, provide protection against amyloid neurotoxicity. The mechanisms involve inhibition of amyloidogenesis, decreased tau phosphorylation. up-regulation of ADAM10 activity, inhibition of presenilin 1 expression, activation of Akt signaling and GSK-3β phosphorylation, and up-regulation of SIRT1 signaling.

3.4. α-Synuclein and Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common progressive neurodegenerative disorder. It is associated with loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) that leads to striatal dopamine (DA) deficiency (Tizabi et al., 2021; González-Usigli et al., 2023). This dopaminergic loss results in motor deficits characterized by akinesia, rigidity, resting tremor, and postural instability as well as non-motor symptoms that might also involve other neurotransmitter systems (Mirelman et al., 2019; Quik et al., 2019). The non-motor symptoms may include cognitive deficits emotional changes, sleep perturbations, autonomic dysfunction, sensory symptoms, and gastrointestinal symptoms (Perez, 2015; González-Usigli et al., 2023). The most common treatment is focused on dopamine replacement (e.g., levodopa, L-Dopa) which losses its full efficacy in few years and can induce severe dyskinesia (Quik et al., 2019; Tizabi et al., 2021; di Biase et al., 2023). Hence, more efficacious interventions without such severe side effects are urgently needed. Recent evidence strongly implicates microbiome dysbiosis in etiology of PD. This knowledge further discussed below allows novel intervention in PD.

Protein misfolding underscored by α-synuclein is a critical player in PD pathology. This protein is synthesized in neurons and appears to be involved in dopamine metabolism (Yu et al., 2005). Yet, overaccumulation of α-synuclein and its subsequent aggregation with the formation of fibrils (Gadhe et al., 2022), possessing neurotoxic effects is associated with neurodegeneration and Parkinson’s disease development (Stefanis, 2012). It has been demonstrated that gut dysbiosis characteristic for PD patients (Hirayama and Ohno, 2021) modulates α-synuclein-induced neurotoxicity (Nielsen et al., 2021). Indeed, modulation of gut microbiota by probiotic treatment was shown to reduce motor and non-motor symptoms of PD (Park et al., 2023). The results of a clinical study demonstrated that probiotic strains of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria generally increase secretion of IL-4 and IL-10 while inhibiting production of IL-6 and IL-17A, as well as superoxide by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from PD patients. These effects were accompanied by a substantial decrease in E. coli and K. pneumoniae growth by probiotic strains (Magistrelli et al., 2019). However, further studies aimed at understating the molecular mechanisms linking probiotic treatment to neuroprotection in PD are warranted (Metta et al., 2022).

In a model of hemiparkinsonism induced by hydroxydopamine injection into striatum, pretreatment, and subsequent treatment with probiotics L. rhamnosus GG and B. lactis BB12 significantly decreased the loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive dopaminergic neurons and microglia activation in the striatum, resulting in improved the crossing speed and reduction of paw slips, indicative of improved motor function (Cuevas-Carbonell et al., 2022). Correspondingly, administration of a probiotic (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Lactobacillus reuteri, and Lactobacillus fermentum) in 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-exposed rats significantly reduced behavioral, cognitive, and memory impairments due to prevention of neuronal oxidative stress and neuronal damage characterized by increased vacuolation and karyopyknosis (Alipour Nosrani et al., 2021). Treatment with a probiotic complex (Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, and S. thermophilus) was also shown to ameliorate 6-OHDA-induced dopaminergic neuron loss with a decrease in tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine transporter (DAT) immunoreactivity, as well as down-regulation of BDNF, p-TrkB, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) protein expression both in striatum and substantia nigra. Moreover, probiotic treatment possessed anti-inflammatory effects by reducing gliosis, which was associated with down-regulation of NF-κB and stimulation of p-Nrf2 and HO-1 expression (Castelli et al., 2020). In a model of PD induced by intraperitoneal injection of noradrenergic neurotoxin DSP-4 (also known as N-(2-chloroethyl)-N-ethyl-2-bromobenzylamine) and stereotaxic injection of 6-OHDA, treatment with probiotic containing Lactobacilli strains and Enterococcus faecium prevented astrocyte and microglia activation, as well as the loss of TH-positive cells. Specifically, probiotic treatment prevented a decrease in intestinal butyrate levels, prevented an increase in Acetatifactor, Alloprevotella, Lachnospiraceae_NC2004, Ruminococcus_torques and UCG_009, but increased the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes in a PD-model. Probiotics also induced improvement of gut integrity associated with an up-regulation of occludin protein and a decrease in circulating LPS, TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 levels (Sancandi et al., 2023).

In another model of PD, probiotics significantly prevented 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)- and rotenone-induced behavioral alterations through amelioration of dopaminergic neurodegeneration as characterized by a decline in TH-positive neurons, striatal dopamine level and an increase in dopamine turnover. In addition, probiotics reduced microglial activation and increased nigral BDNF and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) content with subsequent activation of CREB via ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling, as well as increased β-hydroxybutyrate levels and a subsequent increase in histone H3 acetylation that is expected to be involved in up-regulation of neurotrophic factors (Srivastav et al., 2019). Administration of probiotic Pediococcus pentosaceus to mice exposed to MPTP improved motor functions and significantly reduced dopaminergic neurodegeneration and α-synuclein accumulation. These effects were associated with up-regulation of Nrf2 signaling, inhibition of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), increased brain GABA content and elevated antioxidant response. Moreover, gut microbiota dysbiosis, characterized by elevation of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria and a decrease in the abundance of Bacteroidota in MPTP-exposed rats, were reversed by probiotic (Pan et al., 2022). Similar results were reported for Clostridium butyricum supplementation in MPTP-induced PD model. There, probiotic treatment prevented motor dysfunction, loss of dopaminergic neurons, and gliosis. There was also concomitant up-regulation of colonic glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and G protein-coupled receptor 41/43 (GPR41) expression with increased brain GLP-1 receptor expression (Sun et al., 2021).

In agreement with other the previously discussed observations, in a MitoPark PD mouse model probiotic (L+B) supplementation significantly improved motor functions by prevention of dopaminergic neuron loss (Hsieh et al., 2020).

Several important findings were obtained from C. elegans models of PD-like neurodegeneration. Specifically, the probiotic Bacillus subtilis was shown to reduce α-synuclein aggregation in C. elegans at least partially by up-regulating sphingolipid metabolism genes (lagr-1, asm-3, and sptl-3) (Goya et al., 2020). Correspondingly, modulation of fatty acid metabolism and mitochondrial β-oxidation by L. rhamnosus HA-114 was shown to prevent age-dependent neurodegeneration in C. elegans (Labarre et al., 2022).

Thus, the evidence provided above, strongly support potential utility of probiotics in neurodegenerative diseases in general and PD in particular. Probiotics may target several key components leading to neurotoxicity including α-synuclein accumulation, dopaminergic dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and neuronal oxidative stress through improvement in gut microbiota diversity and richness, reduction in gut wall permeability, and modulation of gut-brain axis by an increase in SFCA production.

4. Conclusions

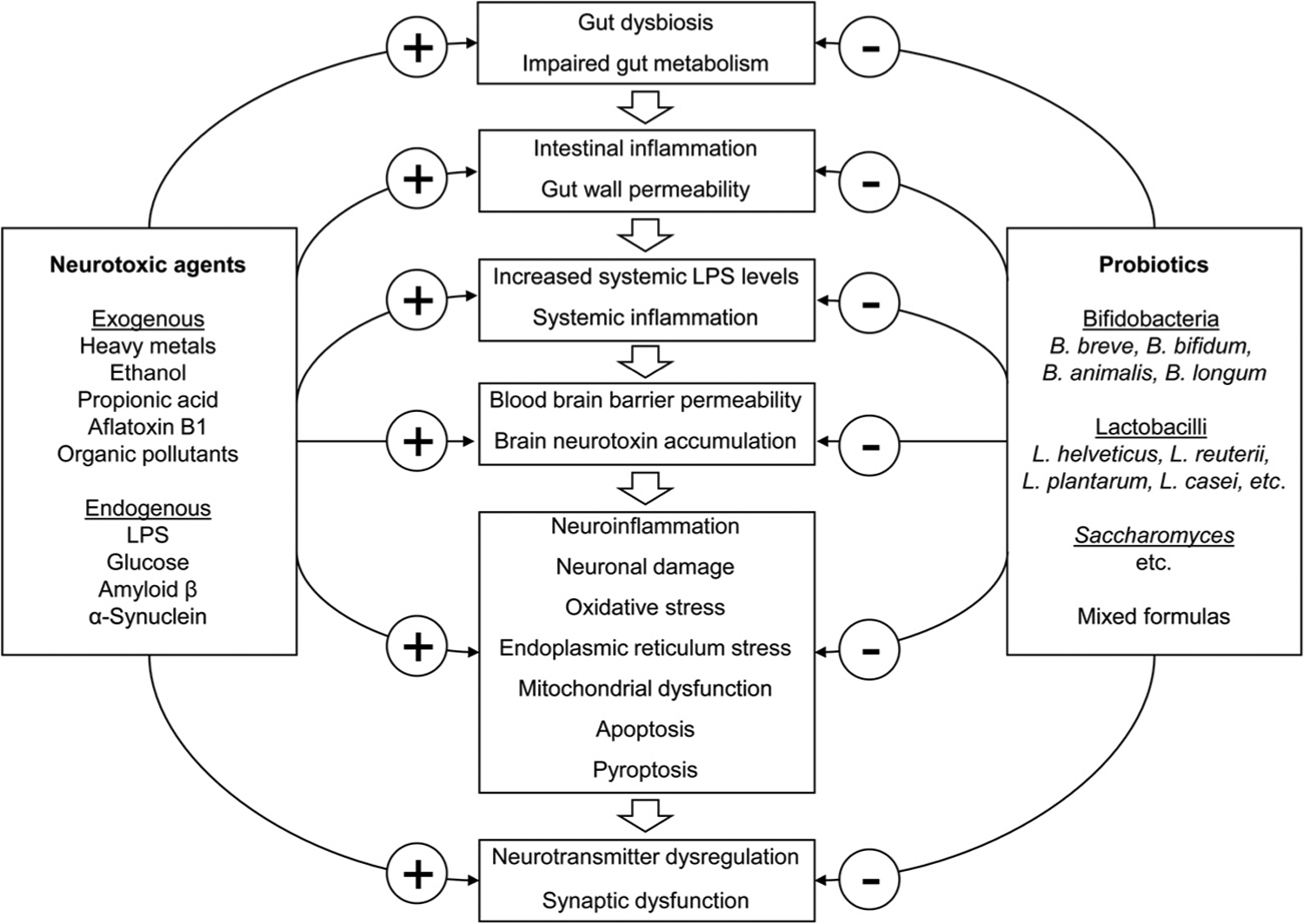

Existing data demonstrate that probiotic supplementation affords protective effects against neurotoxicity of exogenous (e.g., metals, metalloids, ethanol, propionic acid, AFB1, organic pollutants) and endogenous (e.g., LPS, glucose, Aβ, phospho-tau, α-synuclein) agents. Although the protective mechanisms of probiotic treatments differ between various neurotoxic agents, several key mechanisms at both the intestinal and brain levels seem inherent to all of them (Fig. 1). Specifically, probiotic-induced improvement in gut microbiota diversity and taxonomic characteristics results in modulation of gut-derived metabolite production with increased secretion of SFCA. Moreover, modulation of gut microbiota results in inhibition of intestinal absorption of neurotoxic agents and their deposition in brain. Probiotics also maintain gut wall integrity and inhibit intestinal inflammation, thus reducing systemic levels of LPS. Centrally, probiotics ameliorate neurotoxin-induced neuroinflammation by decreasing LPS-induced TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling and prevention of microglia activation.

Fig. 1.

The mechanisms underlying neuroprotective effects of probiotics against toxicity of exogenous and endogenous neurotoxicants.

Neuroprotective mechanisms of probiotic treatment also include inhibition of apoptosis and oxidative stress, at least partially by up-regulation of SIRT1 signaling. Moreover, probiotics reduce inhibitory effect of neurotoxic agents on BDNF expression, on neurogenesis, and on synaptic function. Improvement in synaptic transmission upon probiotic treatment in exposed animals also resulted from reversal of altered neurotransmitter metabolism with increased GABA/Glu ratios, acetylcholine and serotonin levels, as well as inhibition of dopaminergic neuron death. The antiamyloidogenic effect of probiotic treatment was shown to result from up-regulation of ADAM10 activity and down-regulation of presenilin 1 expression due to activation of Akt/pGSK-3β signaling, which also contributed to reduced tau phosphorylation. Finally, probiotic treatment significantly ameliorated the dysregulation of several essential trace elements metabolism both in the brain and at systemic levels, which may also underlie the neuroprotective effects of probiotics.

Therefore, in view of the multiple mechanisms invoked for the neuroprotective effect of probiotics, as well as their high tolerance and safety, the use of probiotics should be considered as a therapeutic strategy for ameliorating adverse brain effects of various endogenous and exogenous agents. However, additional studies are required to evaluate the strain-specific neuroprotective effects of various probiotics. Moreover, comparative analysis of the efficacy of probiotics in comparison to standard therapeutic approach should be carried out.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Project No. FENZ-2023-0004. MA was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) R01ES10563.

Abbreviations

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- 5HT1A

serotonin 1 A receptor

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- AC

adenylate cyclase

- AchE

acetylcholinesterase

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAM10

A Disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10

- ADHD

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- AFB1

Aflatoxin B1

- ALPK1

alpha-protein kinase 1

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- AppNL-G-F

App knock-in

- KI

mice

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

- ATF6

activating transcription factor 6

- Aβ

amyloid

- β

BBB blood-brain barrier

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2 protein

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BIRC3

Baculoviral IAP Repeat Containing 3

- CA1/3

Cornus Ammonis-1/3

- CaM

calmodulin

- CCR2

C-C chemokine receptor type 2

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CX3CR1

CX3C motif chemokine receptor 1

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- ERS

endoplasmic reticulum stress

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GABAR

GABA receptor

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- GLUT

Glucose transporter

- GPR41

G protein-coupled receptor 41/43

- GPX

glutathione peroxidase

- GRP78

glucose-regulated protein 78

- GS

glutamine synthetase

- GSDMD-N

Gasdermin D N-terminus

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSK-3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- H3K4me2

histone H3 dimethylated at lysine 4

- HO-1

heme oxygenase 1

- HSP70

heat shock protein 70

- IFN-γ

interferon γ

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- iNOS

inducible NO synthase

- IRE1α

inositol requiring-enzyme 1 alpha

- Keap1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAO

monoamine oxidase

- MMP2

matrix metalloproteinase 2

- MPTP

−1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- MYD88

Myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88

- NE

norepinephrine

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- NLRP3

NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3

- NMDAR1/2

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors 1 and 2

- NMDAR2B

N-methyl D-aspartate receptor subtype 2B

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PERK

protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- PFBS

perfluorobutane sulfonate

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PPA

propionic acid

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- PSD-95

postsynaptic density protein 95

- RIG-I

retinoic acid-inducible gene I

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SAMP8

senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8

- SCFAs

short-chain fatty acids

- SIRT1

sirtuin 1

- SNpc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- SOD-1/2

superoxide dismutase

- STZ

streptozotocin

- SYP

synaptophysin

- SYT

synaptotagmin

- TH

tryptophan hydroxylase

- TJP1

tight junction protein 1

- TrkB

tropomyosin receptor kinase B

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VGLUT1

Vesicular glutamate transporter 1

- ZO-1

zonula occludens-1

References

- Abdelhamid M, Zhou C, Jung CG, Michikawa M, 2022a. Probiotic Bifidobacterium breve MCC1274 mitigates Alzheimer’s disease-related pathologies in wild-type mice. Nutrients 14 (12), 2543. 10.3390/nu14122543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamid M, Zhou C, Ohno K, Kuhara T, Taslima F, Abdullah M, et al. , 2022b. Probiotic Bifidobacterium breve prevents memory impairment through the reduction of both amyloid-β production and microglia activation in APP knock-in mouse. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 85 (4), 1555–1571. 10.3233/JAD-215025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Salam AM, Al-Dekheil A, Babkr A, Farahna M, Mousa HM, 2010. High fiber probiotic fermented mare’s milk reduces the toxic effects of mercury in rats. N. Am. J. Med. Sci 2 (12), 569–575. 10.4297/najms.2010.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Salam AM, Al Hemaid WA, Afifi AA, Othman AI, Farrag ARH, Zeitoun MM, 2018. Consolidating probiotic with dandelion, coriander and date palm seeds extracts against mercury neurotoxicity and for maintaining normal testosterone levels in male rats. Toxicol. Rep 5, 1069–1077. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Elfotuh K, Selim HMRM, Riad OKM, Hamdan AME, Hassanin SO, Sharif AF, et al. , 2023. The protective effects of sesamol and/or the probiotic, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, against aluminum chloride-induced neurotoxicity and hepatotoxicity in rats: modulation of Wnt/β-catenin/GSK-3β, JAK-2/STAT-3, PPAR-γ, inflammatory, and apoptotic pathways. Front. Pharmacol 14, 1208252. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1208252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adedara IA, Atanda OE, Sant’Anna Monteiro C, Rosemberg DB, Aschner M, Farombi EO, et al. , 2023. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of aflatoxin B1-mediated neurotoxicity: the therapeutic role of natural bioactive compounds. Environ. Res 237 (Pt 1), 116869. 10.1016/j.envres.2023.116869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adli DEH, Benreguieg M, Brahmi M, Ziani K, Arabi W, Hachem K, et al. , 2023. The therapeutic effect of a Lactobacillus rhamnosus probiotic against chronic lead-induced neurotoxicity in developing Wistar rats (gestation and lactation). Fresenius Environ. Bull 32 (5), 2350–2362. [Google Scholar]

- Ağagündüz D, Gençer Bingöl F, Çelik E, Cemali Ö, Özenir Ç, Özoğul F, et al. , 2022. Recent developments in the probiotics as live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) as modulators of gut brain axis related neurological conditions. J. Transl. Me 20 (1), 460. 10.1186/s12967-022-03609-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed H, Sharif A, Bakht S, Javed F, Hassan W, 2021. Persistent organic pollutants and neurological disorders: from exposure to preventive interventions. Environmental Contaminants and Neurological Disorders Emerging Contaminants and Associated Treatment TechnologiesSpringer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-030-66376-6_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi MA, Al-Ayadhi L, Hassan WM, Bhat RS, Alonazi MA, El-Ansary A, 2022. Bee pollen and probiotics may alter brain neuropeptide levels in a rodent model of autism spectrum disorders. Metabolites 12 (6), 562. 10.3390/metabo12060562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alipour Nosrani E, Tamtaji OR, Alibolandi Z, Sarkar P, Ghazanfari M, Azami Tameh A, et al. , 2021. Neuroprotective effects of probiotics bacteria on animal model of Parkinson’s disease induced by 6-hydroxydopamine: a behavioral, biochemical, and histological study. J. Immunoass. Immunochem 42 (2), 106–120. 10.1080/15321819.2020.1833917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonazi M, Ben Bacha A, Al Suhaibani A, Almnaizel AT, Aloudah HS, El-Ansary A, 2022. Psychobiotics improve propionic acid-induced neuroinflammation in juvenile rats, rodent model of autism. Transl. Neurosci 13 (1), 292–300. 10.1515/tnsci-2022-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonazi M, Ben Bacha A, Alharbi MG, Khayyat AIA, Al-Ayadhi L, El-Ansary A, 2023. Bee pollen and probiotics’ potential to protect and treat intestinal permeability in propionic acid-induced rodent model of autism. Metabolites 13 (4), 548. 10.3390/metabo13040548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsubaiei SRM, Alfawaz HA, Bhat RS, El-Ansary A, 2023. Nutritional intervention as a complementary neuroprotective approach against propionic acid-induced neurotoxicity and associated biochemical autistic features in rat pups. Metabolites 13 (6), 738. 10.3390/metabo13060738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluwong T, Ayo JO, Kpukple A, Oladipo OO, 2016. Amelioration of hypergly-caemia, oxidative stress and dyslipidaemia in alloxan-induced diabetic wistar rats treated with probiotic and vitamin C. Nutrients 8 (5), 151. 10.3390/nu8050151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparna S, Patri M, 2023. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment potentiates ethanol-induced behavioral changes through modulation of intestinal epithelium in Danio rerio. Int. Microbiol 26 (3), 551–561. 10.1007/s10123-022-00320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli F, Mengoni B, Maggi E, Mazzoni C, Preziosi A, Mancini P, et al. , 2022. Milmed yeast alters the LPS-induced M1 microglia cells to form M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype. Biomedicines 10 (12), 3116. 10.3390/biomedicines10123116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschner M, Skalny AV, Gritsenko VA, Kartashova OL, Santamaria A, Rocha JBT, et al. , 2023. Role of gut microbiota in the modulation of the health effects of advanced glycation end-products (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med 51 (5), 44. 10.3892/ijmm.2023.5247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athari Nik Azm S, Djazayeri A, Safa M, Azami K, Ahmadvand B, Sabbaghziarani F, et al. , 2018. Lactobacilli and bifidobacteria ameliorate memory and learning deficits and oxidative stress in β-amyloid (1–42) injected rats. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab 43 (7), 718–726. 10.1139/apnm-2017-0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aytekin Sahin G, Karabulut D, Unal G, Sayan M, Sahin H, 2022. Effects of probiotic supplementation on very low dose AFB1-induced neurotoxicity in adult male rats. Life Sci 306, 120798. 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer-Trias J, Deepika D, Schuhmacher M, Kumar V, 2022. Impact of contaminants on microbiota: linking the gut-brain axis with neurotoxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (3), 1368. 10.3390/ijerph19031368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]