Abstract

Background:

The 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20) was developed to extend pneumococcal disease protection beyond 13-valent PCV (PCV13).

Methods:

This phase 3, double-blind study conducted in the United States/Puerto Rico evaluated PCV20 safety and immunogenicity. Healthy infants were randomized to receive a 4-dose series of PCV20 or PCV13 at 2, 4, 6 and 12–15 months old. Objectives included demonstrating noninferiority (NI) of PCV20 to PCV13 immunoglobulin G (IgG) geometric mean concentrations after doses 3 and 4 and percentages of participants with predefined IgG concentrations after dose 3, with 7 additional PCV20 serotypes compared with the lowest result among vaccine serotypes in the PCV13 group. Safety assessments included local reactions, systemic events, adverse events, serious adverse events and newly diagnosed chronic medical conditions.

Results:

Overall, 1991 participants were vaccinated (PCV20, n = 1001; PCV13, n = 990). For IgG geometric mean concentrations 1 month after both doses 3 and 4, all 20 serotypes met NI criteria (geometric mean ratio lower 2-sided 95% confidence interval > 0.5). For percentages of participants with predefined IgG concentrations after dose 3, NI (percentage differences lower 2-sided 95% confidence interval > –10%) was met for 8/13 matched serotypes and 6/7 additional serotypes; 4 serotypes missed the statistical NI criterion by small margins. PCV20 also elicited functional and boosting responses to all 20 serotypes. The safety profile of PCV20 was similar to PCV13.

Conclusion:

A 4-dose series of PVC20 was well tolerated and elicited robust serotype-specific immune responses expected to help protect infants and young children against pneumococcal disease due to the 20 vaccine serotypes. Clinical trial registration: NCT04382326.

Keywords: infants, immunogenicity and safety, 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, Streptococcus pneumoniae, clinical trial

Children younger than 5 years of age are disproportionately affected by pneumococcal disease, which can manifest as noninvasive disease, such as acute otitis media, as well as potentially life-threatening invasive pneumococcal disease, including bacteremic pneumonia, meningitis, or septicemia.1–3 A limited number of the more than 100 unique pneumococcal serotypes are associated with the majority of pneumococcal disease cases.4–6

The availability and widespread uptake of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) have substantially decreased the pneumococcal disease burden worldwide.7 The 7-valent PCV (PCV7; serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F and 23F) was incorporated into infant immunization programs starting in 2000 and replaced with the 13-valent PCV (PCV13), with conjugates for 6 additional serotypes (1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F and 19A), from 2010.8,9 Ten- and 15-valent PCVs are also available in some countries/regions.10,11 Globally, in the 10 years since initial introduction of PCV13 into national immunization programs, an estimated 175 million pneumococcal disease cases and >620,000 associated deaths have been averted in children <5 years old.7 However, a substantial disease burden remains, with an estimated 40% of pediatric invasive pneumococcal disease cases caused by non-PCV13 serotypes.12–17

To expand protection against non-PCV13 serotypes, a 20-valent PCV (PCV20) containing PCV13 components and conjugates for 7 additional serotypes (8, 10A, 11A, 12F, 15B, 22F and 33F) has been developed.18–25 These serotypes are a prevalent cause of pediatric illness, and the associated disease has been correlated with increased severity, invasive potential and antibiotic resistance.12,26–31 PCV20 is licensed for the prevention of pneumococcal disease in adults ≥18 years of age in several countries,32–34 in children from 6 weeks of age in the United States, Canada, Australia, Brazil and Argentina, and under review for use in pediatric populations in other countries.32,33,35,36

Here, we report the findings of a phase 3 trial of PCV20, evaluating the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of PCV20 administered as a 4-dose series (3 infant doses plus toddler dose) with routine pediatric vaccinations.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This phase 3, randomized, double-blind study, enrolled participants from 92 sites in the United States and Puerto Rico from May 20, 2020, to September 2, 2022 (NCT04382326). Healthy infants born at >36 weeks estimated gestational age and who were 42–98 days of age at the time of parental consent were eligible to participate. Key exclusion criteria included significant neurologic disorder or history of seizure or significant stable/evolving neurological disorders; known/suspected immunodeficiency or immunosuppression, or current treatment with immunosuppressive therapy; and prior receipt of pneumococcal, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, or Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines. Additional eligibility criteria, randomization and blinding details, ethical conduct and immunogenicity assessments are outlined in Text, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/F507.

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive PCV20 or PCV13 at approximately 2, 4, 6 and 12–15 months of age (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/INF/F508) administered intramuscularly into the anterolateral thigh muscle of the left leg at each vaccination visit. Participants received the same vaccine for all 4 doses. Concomitant with PCV20 or PCV13, participants also received diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis vaccine in combination with poliovirus and hepatitis B antigens (PEDIARIX; GlaxoSmithKline) and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine (HIBERIX; GlaxoSmithKline) at doses 1, 2 and 3 and measles, mumps and rubella (M-M-RII; Merck) and varicella (VARIVAX; Merck) vaccines at dose 4. Rotavirus and influenza vaccines could be given at any time (including with study vaccines) according to the advisory committee on immunization practices recommendations.

Objectives and Endpoints

Blood was collected for immunogenicity assessments 1 month after dose 3, and before and 1 month after dose 4, and analyzed at a central laboratory. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentrations were measured by the Pfizer Luminex assay and opsonophagocytic activity (OPA) titers were measured in the Pfizer OPA assay.37–39 The predefined IgG concentration was ≥0.35 μg/mL except for serotypes 5 (≥0.23 μg/mL), 6B (≥0.10 μg/mL) and 19A (≥0.12 μg/mL) based on bridging of the Luminex assay to the World Health Organization pneumococcal enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.40

The coprimary pneumococcal immunogenicity objectives were to demonstrate noninferiority (NI) of PCV20 to PCV13 by (1) serotype-specific IgG geometric mean concentrations (GMCs) for the 20 serotypes 1 month after dose 4 and (2) percentages of participants with predefined serotype-specific IgG concentrations for the 20 serotypes 1 month after dose 3. A key secondary objective was demonstration of NI of PCV20 to PCV13 IgG GMCs 1 month after dose 3. For the 13 matched serotypes, the PCV20 group was compared with the corresponding serotype in the PCV13 group; results for the 7 additional serotypes after PCV20 were compared with the lowest result among vaccine serotypes in the PCV13 group, excluding serotype 3 (due to its atypical immunogenicity characteristics for NI evaluation).

Other secondary and exploratory objectives included percentages of participants with predefined serotype-specific IgG concentrations in each group 1 month after dose 4; geometric mean fold rises in IgG concentrations and OPA titers, from before dose 4 to 1 month after dose 4, and from 1 month after dose 3 to 1 month after dose 4; OPA geometric mean titers (GMTs) and percentages of participants with OPA titers ≥ the lower limit of quantitation 1 month after doses 3 and 4. A supportive analysis used an alternate predefined IgG concentration [≥0.15 μg/mL except for serotypes 6B (≥0.10 μg/mL) and 19A (≥0.12 μg/mL)] based on a level inferred from a PCV7 efficacy trial.41 Based on regulatory precedent and consistent with World Health Organization guidance, overall evaluation of PCV performance includes considerations of the coprimary and key secondary IgG comparisons as well as the supportive data showing functional responses and evidence of memory responses.42,43

We also included primary concomitant immunogenicity objectives to demonstrate that at 1 month after dose 3, the percentages of participants with prespecified antibody levels to specific concomitant vaccine antigens when given with PCV20 were noninferior to the corresponding percentages when given with PCV13. These immunogenicity results will be described in a separate publication.

Safety objectives were to describe the frequency of local reactions, systemic events and adverse events (AEs) following vaccination. The percentages of participants reporting local reactions (redness, swelling and injection site pain) and systemic events (fever, decreased appetite, drowsiness and irritability) were collected by participants’ parents/legal guardians using an electronic diary daily for 7 days after each dose. AEs were assessed from dose 1 to 1 month after dose 3 and from dose 4 to 1 month after dose 4, serious AEs (SAEs) and newly diagnosed chronic medical conditions (NDCMCs) were assessed from dose 1 through 6 months after dose 4.

Statistical Analyses

Pneumococcal immunogenicity analyses were based on evaluable immunogenicity sets of eligible participants who were within the protocol-defined age window for dose 1 and dose 4, received 3 or 4 doses of the vaccine to which they were randomized, had ≥1 valid immunogenicity result from a blood sample collected within a prespecified window 1 month after dose 3 or 4, and had no other major protocol deviations. Sample size considerations and details on evaluable populations are provided in Text, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/F507.

IgG GMCs, OPA GMTs, IgG geometric mean ratios and IgG and OPA geometric mean fold rises were calculated by exponentiating the mean logarithm of IgG concentrations, OPA titers, differences in the means and fold rises respectively, with the associated CIs calculated based on Student t distributions. NI of PCV20 to PCV13 for IgG GMCs was declared for a serotype if the lower bound of the 2-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the IgG geometric mean ratio (PCV20 to PCV13) was greater than 0.5 (2-fold NI margin). NI of PCV20 to PCV13 for the percentage of participants with predefined serotype-specific IgG concentrations for a serotype was declared if the lower bound of the 2-sided 95% CI for the difference (PCV20–PCV13) in percentages, based on the Miettinen and Nurminen method, was greater than −10% (10% NI margin).

Descriptive summary statistics were provided for safety endpoints in the safety population (participants receiving ≥1 study vaccine dose) and other binary immunogenicity endpoints.

RESULTS

Participants

Overall, 1997 participants were randomized and 1991 were vaccinated (PCV20, n = 1001; PCV13, n = 990), with 93.1% (n = 1860) and 85.0% (n = 1697) completing 3 doses and 4 doses, respectively (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/INF/F509). Demographic characteristics of participants were generally similar in the 2 groups (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/INF/F510). Approximately 25% of the study population was nonwhite and about 30% were Hispanic/Latino. Median (range) age was 64 (42–97) days at dose 1 and 372 (365–460) days at dose 4.

Rotavirus vaccines were the most common nonstudy vaccines coadministered with study vaccines at dose 1 (87.4%), dose 2 (84.4%) and dose 3 (65.4%); approximately 10% of participants received influenza vaccines each at doses 3 and 4.

Immunogenicity

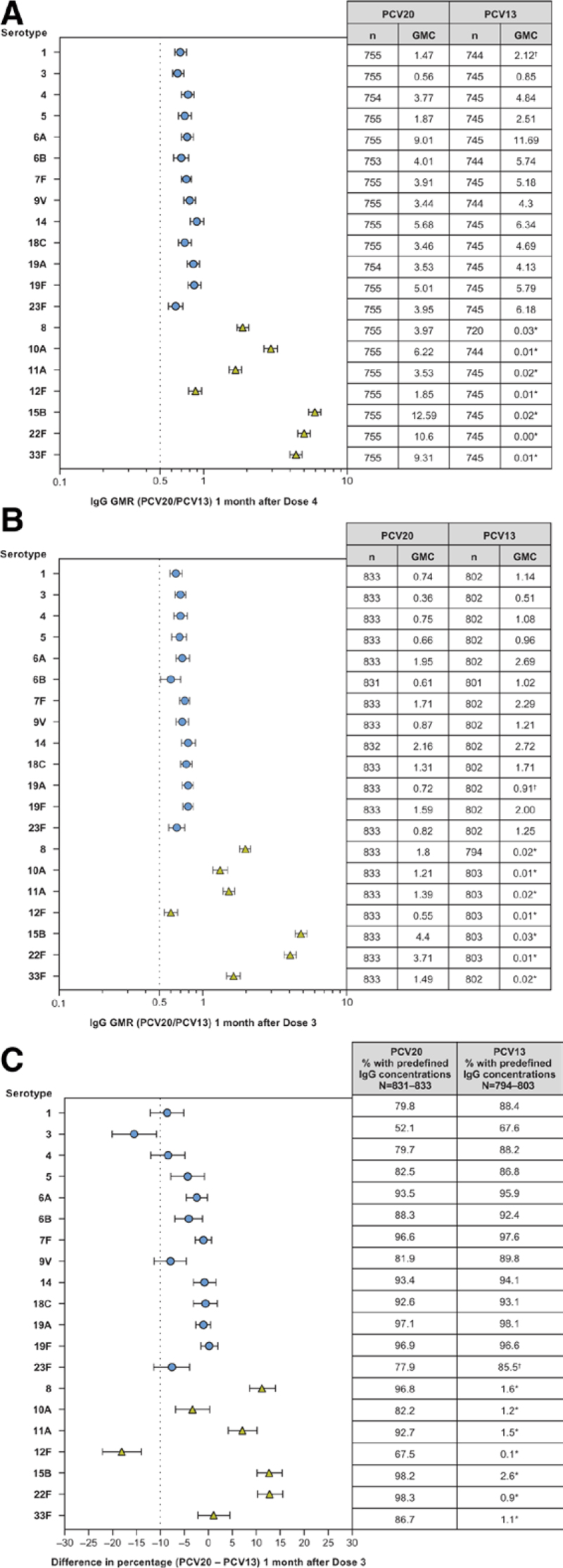

At 1 month after doses 3 and 4, IgG GMCs for all 13 matched serotypes in the PCV20 group were noninferior to the GMCs for the corresponding serotypes in the PCV13 group, and all 7 additional serotypes in the PCV20 group were noninferior to the lowest IgG GMC among the vaccine serotypes in the PCV13 group (Fig. 1A, B), excluding serotype 3. At 1 month after dose 3, the percentages of participants with predefined serotype-specific IgG concentrations for 8 of the 13 matched serotypes were noninferior to the percentages for the corresponding serotypes in the PCV13 group [serotypes 1, 4, 9V and 23F missed statistical NI by small margins (lower bounds of 2-sided 95% CIs of the difference ≥ −12.1%, NI criterion required the lower bound > −10%); Fig. 1C]. Percentages from 6 of 7 additional serotypes in the PCV20 group (all except serotype 12F) were noninferior to the lowest percentage among the vaccine serotypes (excluding serotype 3) in the PCV13 group. Reverse cumulative distribution curves show that the actual distributions of the IgG concentrations after doses 3 and 4 were generally similar in the 2 groups for the 13 matched serotypes and substantially higher than and well differentiated from those in the PCV13 group for the 7 additional serotypes (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/INF/F511). In the supportive analysis using an alternate predefined concentration 1 month after dose 3, all matched serotypes would have met NI of PCV20 compared with PCV13 using the same 10% NI criterion (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 6, http://links.lww.com/INF/F512). At 1 month after dose 4, strong IgG boosting responses were observed for the 20 serotypes when IgG concentrations were compared from before dose 4 and from 1 month after dose 3 (Fig. 2; Table, Supplemental Digital Content 7, http://links.lww.com/INF/F513), providing evidence to support PCV20-induced memory responses after 3 infant doses.

FIGURE 1.

GMRs (PCV20/PCV13) and 2-sided 95% CIs 1 month after (A) dose 4 and (B) dose 3 and (C) differences (PCV20 − PCV13) and 2-sided 95% CIs in percentages of participants with predefined IgG concentrations 1 month after dose 3. Assay results below LLOQ were set to 0.5 × LLOQ. For the PCV13 serotypes (circles), the compared results are from the corresponding serotype in the For the 7 additional serotypes (triangles), (A) the compared results are from serotype 1 (the PCV13 serotype with the lowest GMC, not including serotype 3) in the PCV13 group; (B) the compared results are from serotype 19A (the PCV13 serotype with the lowest GMC, not including serotype 3) in the PCV13 group and (C) the compared results are from serotype 23F (the PCV13 serotype with the lowest percentage, not including serotype 3) in the PCV13 group. Results are based on the evaluable immunogenicity population. *The IgG GMCs (A and B) and percentages with predefined IgG concentrations (C) shown in the tables for the 7 additional serotypes are the results from the corresponding serotypes. †The results used for the NI comparison for the 7 additional serotypes. GMC indicates geometric mean concentration; GMR, geometric mean ratio; IgG, immunoglobulin G; LLOQ, lower limit of quantitation; NI, noninferiority; PCV13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PCV20, 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

FIGURE 2.

IgG GMCs (2-sided 95% CIs) 1 month after dose 3 and 1 month after dose 4 and GMFRs. GMCs and 2-sided CIs were calculated by exponentiating the mean logarithm of the concentrations and the corresponding CIs (based on the Student t distribution). GMC indicates geometric mean concentrations; GMFR, geometric mean fold rise; IgG, immunoglobulin G; PCV13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PCV20, 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

PCV20 elicited OPA responses to all 20 serotypes at 1 month after dose 3 and 1 month after dose 4 based on OPA GMTs (Fig. 3) and the percentages of participants with OPA titers ≥ lower limit of quantitation (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 8, http://links.lww.com/INF/F514). OPA GMTs for the 13 matched serotypes after doses 3 and 4 of PCV20 were generally like those in the PCV13 group for most serotypes and substantially higher than the corresponding serotypes in the PCV13 group for the 7 additional serotypes. Evidence of OPA boosting was observed for all serotypes, similar to the boosting observed for the IgG responses, indicating that functional memory responses were elicited by PCV20 after the infant doses.

FIGURE 3.

OPA GMTs (2-sided 95% CIs) 1 month after dose 3 and 1 month after dose 4. Assay results below the LLOQ were set to 0.5 × LLOQ in the analysis. OPA titers were determined on serum from randomly selected subsets of participants assuring equal representation of both vaccine groups. GMTs and 2-sided CIs were calculated by exponentiating the mean logarithm of the titers and the corresponding CIs (based on the Student t distribution). GMFR indicates geometric mean fold rise; GMT, geometric mean titer; OPA, opsonophagocytic activity; PCV13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PCV20, 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Safety and Tolerability

Local reactions and systemic events were mainly mild or moderate in severity and the frequency was comparable between the PCV20 and PCV13 groups (Fig. 4). The most frequently reported local reaction was injection site pain (PCV20, 35.7%–49.1%; PCV13, 35.8%–45.3%), and the most frequently reported systemic event was irritability (PCV20, 61.0%–71.6%; PCV13, 61.1%–71.7%), followed by drowsiness (PCV20, 39.5%–67.2%; PCV13, 39.5%–66.0%). Fever >38.9 °C was reported infrequently; 6 participants in the PCV20 group (≤0.2% after any dose) and 1 participant in the PCV13 group experienced fever >40.0 °C. Across doses, local reactions and systemic events had a median onset of day 1–2 (where day 1 is the day of vaccination) and a median duration of 1–2 and 1–3 days, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Percentages of participants with reported (A) local reactions and (B) systemic events. Values above bars represent percentages of participants reporting events of any severity at each dose for each group. For redness and swelling, mild ≥ 0.0–2.0 cm, moderate ≥ 2.0–7.0 cm and severe ≥ 7.0 cm. For pain at the injection site, mild: hurts if gently touched; moderate: hurts if gently touched with crying; severe: causes limitation of limb movement. For decreased appetite, mild: decreased interest in eating; moderate: decreased oral intake; severe: refusal to feed. For drowsiness, mild: increased or prolonged sleeping bouts; moderate: slightly subdued interfering with daily activity; severe: disabling not interested in usual daily activity. For irritability, mild: easily consolable; moderate: requiring increased attention; severe: inconsolable, crying cannot be comforted. PCV20, n = 826–993. PCV13, n = 815–974. D indicates dose; PCV13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PCV20, 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

From dose 1 to 1 month after dose 3, ≥1 AE was reported in 36.6% of participants in the PCV20 group and 39.4% of participants in the PCV13 group (Table 1). AEs were generally consistent with illnesses and medical conditions expected in this age population; the most common AEs were upper respiratory tract infection (PCV20, 9.5%; PCV13, 9.7%) and otitis media (PCV20, 3.9%; PCV13, 3.2%). From dose 4 to 1 month after dose 4, ≥1 AE was reported in 15.1% and 15.0% of participants in the PCV20 and PCV13 groups, respectively; the most common AEs were otitis media (PCV20, 2.8%; PCV13, 2.6%) and upper respiratory tract infection (2.9% in both groups). One nonserious febrile seizure occurred 7 days after dose 4 of PCV20 in a child diagnosed with COVID-19.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Adverse Events (Safety Population)

| Time Point Type | PCV20 | PCV13 |

|---|---|---|

| From dose 1 to 1 month after dose 3, n (%) | (N = 1001) | (N = 988) |

| Any AE | 366 (36.6) | 389 (39.4) |

| Related | 7 (0.7) | 7 (0.7) |

| Severe | 8 (0.8) | 7 (0.7) |

| From dose 4 to 1 month after dose 4, n (%) | (N = 853) | (N = 841) |

| Any AE | 129 (15.1) | 126 (15.0) |

| Related | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Severe | 5 (0.6) | 2 (0.2) |

| For duration of study, n (%) | (N = 1001) | (N = 987)* |

| SAE | 45 (4.5) | 31 (3.1) |

One participant received incorrect vaccine at dose 4 and was therefore excluded in the summary denominator for SAEs across the whole study.

AE indicates adverse event; N, number of participants in the specified group and the denominator for the percentage calculations; N, number of participants reporting ≥1 occurrence of the specified event; PCV13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PCV20, 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; SAE, serious adverse event.

The percentages of participants with SAEs at any time after dose 1 through the 6-month follow-up period after the last dose were low and similar in the PCV20 (4.5%) and PCV13 (3.1%) groups. All SAEs were assessed by the investigators as unrelated to the study intervention; 1 febrile seizure occurred 14 days after dose 4 of PCV20 and was considered possibly related to concomitant measles, mumps and rubella and varicella vaccines. Discontinuations because of AEs were infrequent (PCV20, 0.2%; PCV13, 0.4%). The percentages of participants with NDCMCs after dose 1 were similar in the PCV20 (5.0%) and PCV13 (5.9%) groups. From dose 1 to 1 month after dose 3, NDCMCs were reported for ≤4.0% of all participants and from dose 4 to 1 month after dose 4 for 0.6% of all participants. The majority of NDCMCs were new diagnoses of atopic dermatitis, eczema, or food allergy.

DISCUSSION

There is an unmet need to protect children against non-PCV13 pneumococcal serotypes, an important cause of invasive pneumococcal disease in infants and children in many countries, while maintaining protection against disease due to PCV13 serotypes.17 The data from this phase 3 study in infants in the United States and Puerto Rico show that the 4-dose series of PCV20 elicited immune responses that are expected to provide protection against pneumococcal disease due to all 20 vaccine serotypes and had a similar tolerability and safety profile to PCV13.

Immune responses elicited by PCV20 were robust, with functional activity observed. The overall immunogenicity data showing PCV20 elicits IgG, OPA and boosting responses for the 20 vaccine serotypes together support that PCV20 administered in a 4-dose schedule in infants can infer effectiveness against disease caused by those serotypes. Although the statistical criterion for NI after PCV20 was not met for some serotypes for 1 coprimary objective at 1 month after dose 3, all serotypes met the key secondary objective at this time point and the other coprimary objective at dose 4. IgG concentration distributions were generally similar in the PCV20 and PCV13 groups for the 13 matched serotypes after the third and fourth doses, and substantially higher in the PCV20 group for the corresponding 7 additional serotypes. Additionally, the statistical criterion was missed by only a small margin for 4 of the matched serotypes (1, 4, 9V and 23F); for these and the other 2 serotypes (3 and 12F), substantial evidence showed that PCV20 responses were robust, functional and primed for memory response.

The protective immune responses of PCVs are multifactorial, and therefore it is important to assess immune responses across multiple endpoints; thus, NI comparison of IgG responses, especially using a predefined IgG concentration reference level that is not serotype-specific and not associated with individual protection, is not expected to be the sole determinant of effectiveness.42,43 The key clinical trials of PCV13 supporting licensure in the pediatric population found that serotypes 6B (both trials) and 9V (1 trial) missed 1 of the NI criteria compared to PCV7.44,45 Nevertheless, PCV13 was approved in 2010 based on the totality of data from multiple immunogenicity endpoints, including functional and boosting responses.46,47 After introduction in multiple infant immunization programs globally, PCV13 has maintained protection against vaccine serotypes.48,49

The safety and tolerability profile of PCV20 was consistent with that previously reported in phase 2 and 3 studies in infants.23–25 PCV20 was well tolerated, with most local reactions and systemic events being transient and mild or moderate in severity. No safety issues were identified. The AE profile was similar between PCV20 and PCV13; most SAEs and NDCMCs reported were consistent with medical events that may occur in young children.

A study strength was administration of routine concomitant childhood vaccines in most infants, which reflects real-world use. Limitations include that it was not feasible to power the study for all pneumococcal NI comparisons given that 60 individual comparisons were required between the coprimary and key secondary objectives. OPA titers were only measured in a subset of participants due to limited blood volume collected in infants and the number of serotypes needed to test; however, the sample size was adequate to show that PCV20 generated robust functional responses to all 20 serotypes. Additionally, the study is representative of populations that receive a 4-dose series.

The 4-dose series in this trial is recommended in the United States,50 and based on the schedule used in a key PCV7 efficacy trial.51 A 3-dose PCV regimen (2 infant doses plus toddler dose) is recommended in some other countries. A 3-dose PCV20 series was investigated in a recent phase 3, double-blind study in >1200 infants.25 In that study, 16/20 serotypes met NI for ≥1 primary objective after 2 infant doses and 19/20 serotypes met NI for IgG GMCs after the toddler dose.25 As with the 4-dose series in this study, the PCV20 3-dose series induced robust OPA activity and boosting responses against all vaccine serotypes.25 Both PCV20 regimens are expected to expand protection against pneumococcal disease when used in national infant immunization programs. Ultimately, vaccine schedules are generally approved by regulatory agencies and recommended by vaccine technical committees based on many factors including safety, effectiveness, immunogenicity, disease severity, epidemiology and feasibility.

In conclusion, a 4-dose infant series of PVC20 had a safety and tolerability profile like PCV13 and elicited robust immune responses expected to help protect against pneumococcal disease due to the 20 vaccine serotypes, 5 of which are not included in any other approved PCV. Findings from this study expand the data on the safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of PCV20 in a 4-dose vaccine schedule and supported the 2023 pediatric indication approvals for PCV20 in the United States and Canada.32,33

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the parents and children who participated in this study. The medical writing support was provided by Sheena Hunt, PhD, and Tricia Newell, PhD, of ICON (Blue Bell, PA) and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This study was supported by Pfizer Inc.

S.S.: Research support from Pfizer. N.P.K.: Research support from Pfizer, Merck, Sanofi Pasteur and GSK. N.T., A.T., G.B., J.T., Y.P., P.C.G., I.L.S., M.W.P., K.J.C., W.C.G., D.A.S. and W.W. are employees of Pfizer (or were employees at the time of the study) and may hold Pfizer stock or stock options.

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual deidentified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.pidj.com).

Contributor Information

Shelly Senders, Email: ssenders@senderspediatrics.com.

Nicola P. Klein, Email: Nicola.Klein@kp.org.

Allison Thompson, Email: juniordoc@aol.com.

Gary Baugher, Email: gary.baugher@pfizer.com.

James Trammel, Email: james.trammel@pfizer.com.

Yahong Peng, Email: yahong.peng@pfizer.com.

Peter Giardina, Email: peter.giardina@pfizer.com.

Ingrid L. Scully, Email: Ingrid.Scully@pfizer.com.

Michael Pride, Email: michael.pride@pfizer.com.

Kimberly J. Center, Email: Kimberly.Center@pfizer.com.

William C. Gruber, Email: bill.gruber@pfizer.com.

Daniel A. Scott, Email: dascottfamily55@gmail.com.

Wendy Watson, Email: wjw4go@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, et al. ; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wahl B, O’Brien KL, Greenbaum A, et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000-15. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e744–e757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines in Infants and Children Under 5 Years of Age: WHO Position Paper. February 2019. Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/310968/WER9408.pdf?ua=1. Accessed January 24, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geno KA, Gilbert GL, Song JY, et al. Pneumococcal capsules and their types: past, present, and future. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:871–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. Chapter 11: Pneumococcal. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/chpt11-pneumo.html. Accessed February 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Streptococcus pneumoniae. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/clinicians/streptococcus-pneumoniae.html. Accessed July 18, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman R, Sutton K, Dillon-Murphy D, et al. Ten year public health impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in infants: a modelling analysis. Vaccine. 2020;38:7138–7145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nuorti JP, Whitney CG; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children—use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress in introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine--worldwide, 2000-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1148–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaxneuvance (pneumococcal 15-valent conjugate vaccine). Full Prescribing Information. Merck & Co Inc; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Synflorix (pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine [adsorbed]). Summary of Product Characteristics. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals s.a, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balsells E, Guillot L, Nair H, et al. Serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing invasive disease in children in the post-PCV era: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hausdorff WP, Hanage WP. Interim results of an ecological experiment - conjugate vaccination against the pneumococcus and serotype replacement. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:358–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan SL, Barson WJ, Lin PL, et al. Selected impact of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) on invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) at eight children’s hospitals in the United States. 2014–2019. Presented at: IDWeek; October 21, 2020; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 15.GBD 2016 Lower Respiratory Infections Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1191–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang L, Wasserman M, Grant L, et al. Burden of pneumococcal disease due to serotypes covered by the 13-valent and new higher-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in the United States. Vaccine. 2022;40:4700–4708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant LR, Slack MPE, Theilacker C, et al. Distribution of serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in children from high-income countries and the impact of pediatric pneumococcal vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76:e1062–e1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson A, Lamberth E, Severs J, et al. Phase 1 trial of a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy adults. Vaccine. 2019;37:6201–6207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurley D, Griffin C, Young M, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20) in adults 60 to 64 years of age. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e1489–e1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannon K, Elder C, Young M, et al. A trial to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in populations of adults ≥65 years of age with different prior pneumococcal vaccination. Vaccine. 2021;39:7494–7502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein NP, Peyrani P, Yacisin K, et al. A phase 3, randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the immunogenicity and safety of 3 lots of 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naive adults 18 through 49 years of age. Vaccine. 2021;39:5428–5435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Essink B, Sabharwal C, Cannon K, et al. Pivotal phase 3 randomized clinical trial of the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults aged ≥18 years. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75:390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Senders S, Klein NP, Lamberth E, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy infants in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40:944–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer J, Silas P, Ouedraogo GL, et al. A phase 3 trial evaluating the safety and immunogenicity of a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy children 15 months through 17 years of age. Presented at: European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases; May 8-12, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korbal P, Wysocki J, Tamini N, et al. Phase 3 safety and immunogenicity Phase 3 safety and immunogenicity study of a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20) administered in a 3-dose infant immunization series. Presented at: European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases; May 8-12, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilishvili T, Gierke R, Farley M, et al. Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) following 18 years of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) use in the United States. Presented at: IDWeek; October 21, 2020; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen R, Levy C, Ouldali N, et al. Invasive disease potential of pneumococcal serotypes in children after PCV13 implementation. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:1453–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomczyk S, Lynfield R, Schaffner W, et al. Prevention of antibiotic-nonsusceptible invasive pneumococcal disease with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1119–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metcalf BJ, Gertz RE, Jr, Gladstone RA, et al. Strain features and distributions in pneumococci from children with invasive disease before and after 13-valent conjugate vaccine implementation in the USA. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:e9–e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harboe ZB, Thomsen RW, Riis A, et al. Pneumococcal serotypes and mortality following invasive pneumococcal disease: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oligbu G, Collins S, Sheppard CL, et al. Childhood deaths attributable to invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales, 2006-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfizer Inc. Highlights of Prescribing Information: Prevnar 20TM (Pneumococcal 20-Valent Conjugate Vaccine). Available at: https://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=15428. Accessed August 22, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfizer Canada. Product Monograph Pneumococcal 20-valent Conjugate Vaccine. Available at: https://webfiles.pfizer.com/file/eaacb9cc-8b8c-4ddf-af69-93e374730387?referrer=ccb731e5-4f2d-4f4a-b2dc-e5e912145fc6. Accessed January 9, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 34.European Medicines Agency. Apexxnar: Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Conjugate Vaccine (20-Valent, Adsorbed). Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/apexxnar. Accessed July 10, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Health Surveillance Agency MoH, Brazil,. Prevenar® 20 (20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine): new registration. Available at: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/novos-medicamentos-e-indicacoes/prevenar-r-20-vacina-pneumococica-20-valente-conjugada-novo-registro. Accessed February 8, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Therapeutic Goods Administration Australia. AUSTRALIAN PRODUCT INFORMATION – PREVENAR 20® (pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate, 20-valent adsorbed) VACCINE. Available at: https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2022-PI-02385-1&d=20240207172310101. Accessed February 8, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pavliakova D, Giardina PC, Moghazeh S, et al. Development and validation of 13-plex Luminex-based assay for measuring human serum antibodies to Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides. mSphere. 2018;3:e00128–e00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper D, Yu X, Sidhu M, et al. The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) elicits cross-functional opsonophagocytic killing responses in humans to Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 6C and 7A. Vaccine. 2011;29:7207–7211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scully IL, Cutler MW, Gangolli S, et al. Development, maintenance, and application of opsonophagocytic assays to measure functional antibody responses to support a 20 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(Suppl 2):S484. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan CY, Immermann FW, Sebastian S, et al. Evaluation of a validated Luminex-based multiplex immunoassay for measuring immunoglobulin G antibodies in serum to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides. mSphere. 2018;3:e00127–e00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Black S, Shinefield H. Safety and efficacy of the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: evidence from Northern California. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:S127–S131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization. Recommendations to Assure the Quality, Safety and Efficacy of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines, Annex 3, TRS No 977. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/pneumococcal-conjugate-vaccines-annex3-trs-977. Accessed July 11, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feavers I, Knezevic I, Powell M, et al. ; World Health Organization Consultation on Serological Criteria for Evaluation and Licensing of New Pneumococcal Vaccines. Challenges in the evaluation and licensing of new pneumococcal vaccines, 7-8 July 2008, Ottawa, Canada. Vaccine. 2009;27:3681–3688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeh SH, Gurtman A, Hurley DC, et al. ; 004 Study Group. Immunogenicity and safety of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e493–e505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kieninger DM, Kueper K, Steul K, et al. ; 006 study group. Safety, tolerability, and immunologic noninferiority of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared to a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine given with routine pediatric vaccinations in Germany. Vaccine. 2010;28:4192–4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfizer Inc. Highlights of Prescribing Information: Prevnar 13TM (Pneumococcal 13-Valent Conjugate Vaccine). Available at: http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=501. Accessed July 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Food and Drug Administration. Summary Basis for Regulatory Action. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/104317/download?attachment. Accessed April 26, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Linden M, Imohl M, Perniciaro S. Limited indirect effects of an infant pneumococcal vaccination program in an aging population. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0220453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ben-Shimol S, Regev-Yochay G, Givon-Lavi N, et al. ; Israeli Pediatric Bacteremia and Meningitis Group (IPBMG). Dynamics of invasive pneumococcal disease in Israel in children and adults in the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) era: a nationwide prospective surveillance. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:1639–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal Vaccine Recommendations. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/recommendations.html. Accessed June 21, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, et al. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.