Abstract

The National Institute on Aging (NIA), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), was founded in 1974 to support and conduct research on aging and the health and well-being of older adults. Fifty years ago, the concept of studying aging generated much skepticism. Early NIA-funded research findings helped establish the great value of aging research and provided the foundation for significant science advances that have improved our understanding of the aging process, diseases and conditions associated with aging, and the effects of health inequities, as well as the need to promote healthy aging lifestyles. Today, we celebrate the many important contributions to aging research made possible by NIA, as well as opportunities to continue to make meaningful progress. NIA emphasizes that the broad aging research community must continue to increase and expand our collective efforts to recruit and train a diverse next generation of aging researchers.

Keywords: Aging research, healthy aging, diversity

Intro and historical highlights

Human aging looks considerably different today than it did in 1974 when the National Institute on Aging (NIA), one of 27 institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health, was established by an act of Congress. World-wide, the population of older adults is growing rapidly1, and thanks to medical advances, more people are living to older ages2. Concurrently, in the United States, large disparities persist, midlife mortality and morbidity is increasing3,4,5, and our nation is lagging behind other developed countries in longevity6.

In 1974 when NIA was founded, Robert N. Butler, M.D. (1927–2010), a geriatrician and the first NIA director, was committed to improving the lives of older adults by liberating this ever-growing segment of the population from the stigmas associated with older age. His many published works, including his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Why Survive? Being Old in America, increased public understanding of the challenges and opportunities of an aging society. One of his greatest accomplishments was enhancing appreciation of Alzheimer’s disease as a highly prevalent condition that imposes major burdens on individuals, families, communities, and our economy.

This initial groundwork and investments from Congress in the years since have enabled NIA to lead the federal government in funding and conducting research on a broad range of aging-related processes and conditions — including Alzheimer’s — as well as the overall health and well-being of older adults. These investments have yielded significant achievements. For example, dementia research advances are providing new hope, with a disease-modifying therapeutic available to a subpopulation of those living with Alzheimer’s, and other interventions not far behind.

NIA’s contributions over the past five decades have also highlighted the need for physical activity to maintain function, revealed that managing blood pressure can reduce the risk of cognitive impairment, and provided evidence that seemingly benign interventions (e.g., daily aspirin therapy and testosterone supplementation) may have limited positive impact and non-trivial risks.

So that our achievements continue to have a significant impact on aging research and public health, and our future discoveries will be most meaningful, we must ensure the research NIA funds and conducts is inclusive of diverse scientists and relevant to all populations, including those historically underrepresented or excluded from research. NIA’s efforts are bolstered by a broad range of initiatives in these areas, from diversity supplements to real-time clinical trial enrollment tracking systems. We also must expand the clinical scientific workforce — including physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals — focused on developing and testing interventions for dementia and other aging-related conditions. NIA-funded scientists have also demonstrated an increased need for more trained professionals who can implement evidence-based research as they work with and care for older adults.

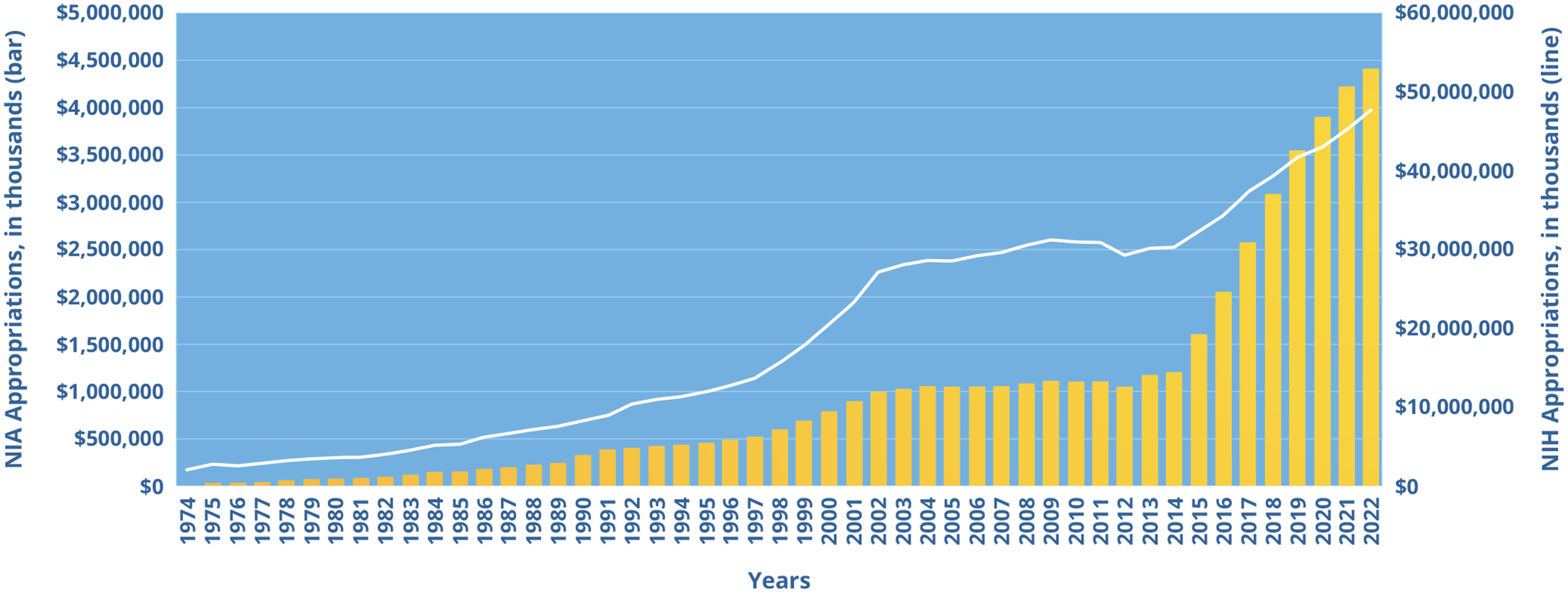

Congressional investments in NIA have been unprecedented in recent years (see Figure 1) and we hope the successes reflect the original intent of our institution as well as Dr. Butler’s hope for a better future for all individuals as they age.

FIGURE 1:

NIA Funding Over 50 Years

This figure shows NIA’s yearly appropriations (bars) since 1974 alongside appropriations for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (line). NIA is one of 27 Institutes and Centers of the NIH. It is now the third-largest Institute in terms of funding.

Contributions to aging research over the years

NIA’s mission to conduct genetic, biological, clinical, behavioral, social, and economic research on aging has resulted in key contributions to understanding the nature of aging and the aging process, and the diseases and conditions associated with growing older.

The biology of Alzheimer’s and related dementias.

In 2010, we knew of just 10 genetic areas associated with Alzheimer’s. Today, we know of at least 80, including rare gene variants that may help protect against the disease. Understanding genetic variants and how they are involved in dementia opens new avenues for further exploring mechanisms that cause the disease and may be targeted by new treatment. Researchers also now know far more about the underlying disease processes of dementia and the complex overlapping pathologies that lead to mixed dementia. Just a decade ago, dementia research was focused almost solely on the brain; today we are exploring interactions with other organs, including links between the vascular and digestive systems.

Dementia risk reduction.

A 2017 evidence-based, NIA-commissioned report concluded that evidence on lifestyle factors to prevent Alzheimer’s was encouraging in the areas of blood pressure control, physical activity, and cognitive training, but findings were still not conclusive. Since then, scientists have strengthened the evidence for dementia risk reduction in several areas, including blood pressure control. Findings from the SPRINT MIND trial indicate that intensive blood pressure control can reduce the risk for mild cognitive impairment7, often a precursor to dementia, and slow the development of white matter lesions in the brain8. Building on the ACTIVE study9, NIA is now supporting a large clinical trial to assess whether speed of processing training can reduce incidence of cognitive impairment and dementia. Multiple studies are examining the role of physical activity and other lifestyle modifications, with increasing emphasis on starting prevention efforts earlier in life and targeting individuals and groups at greatest risk. Another recent clinical trial showed that hearing aid use in people with a higher risk of dementia had an almost 50% reduction in the rate of cognitive decline compared with a control group10.

Discovery and development of biomarkers for Alzheimer’s and related dementias.

Before the early 2000s, autopsy was the only definitive way to diagnose Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia. Thanks to NIA-funded research, tests are now available to help physicians identify biomarkers associated with these diseases in a living person. Years of NIA investments helped lead to the first commercial blood test for amyloid. Scientists additionally continue to study new potential biomarkers, such as measuring brain inflammation, as well as digital health technologies to capture the various and complex behavioral changes associated with progressive cognitive impairment.

Treatments for dementia.

Over the past decade, NIA funding enabled the development and testing of 18 new dementia drug candidates in clinical trials, with two more ready to enter trials. NIA research has also been instrumental in other ways leading to more effective dementia treatments, for example, by developing amyloid PET imaging and elucidating the role of amyloid. In 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration provided its first traditional approval of an anti-amyloid drug — lecanemab — that affects the underlying disease process of Alzheimer’s instead of only treating symptoms. Researchers also recently found that donanemab, another anti-amyloid drug, was effective in slowing the rates of cognitive and functional decline in participants who have early symptoms of Alzheimer’s11.

Biology of aging.

Aging is a primary risk factor for many diseases and conditions, including dementia, most forms of cancer, many types of heart disease, osteoporosis and hip fracture, kidney failure, and diabetes. Biology of aging researchers seek a better understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms of aging characteristics and phenotypes to lead to improved health at older ages. The identification of several hallmarks of aging as the biological drivers of aging have provided for significant advances in aging research. Essential findings have helped catalyze in-depth research into the mechanisms of aging, such as:

Impacts on aging of senescence at the cellular level. Senescence, one of the hallmarks of aging, is a process in which cells lose function, including the ability to divide and replicate, but continue to secrete molecules that can damage neighboring cells. Recent evidence suggests immune cell senescence is a major driver of aging in multiple tissues12.

Calorie restriction. This has been shown to extend life span and delay adverse aging changes in animal models. A clinical trial in humans found that a 12% reduction in calories resulted in improvements in cardiometabolic risk factors, among other health benefits13. Researchers are also investigating other dietary manipulations, such as intermittent fasting, that can have profound effects on aging.

Genetic influences on life span. Single gene mutations can underlie shorter life spans (progeroid syndromes)14, 15, and human centenarians demonstrate the polygenic nature of longer and healthier life and importantly show that “compression of morbidity” is possible16.

Geroscience.

Understanding and modifying the molecular and cellular mechanisms responsible for aging could identify processes that underlie multiple chronic conditions of aging and could thus address multiple diseases and conditions simultaneously, leading to a healthier population. Changes in the hallmarks of aging can indicate either accelerated or delayed aging, or provide targets for preventing or treating various diseases. NIA-funded researchers have found that treatment with senolytics — compounds that selectively remove senescent cells — extended life span and health span in naturally aging mice. NIA is currently funding clinical trials in humans to test senolytic compounds for the prevention or alleviation of frailty, diabetic kidney disease, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (a serious lung disease), and more recently, to boost protection against COVID-19 and to examine the impact of life stressors and social determinants of health on biological aging.

The role of inflammation in aging.

Inflammation is an essential part of the recovery and healing process. In response to acute infection or injury, immune cells release inflammatory molecules called cytokines, which sound the alarm to recruit help from other immune cells. However, low-level chronic inflammation, including inflammation driven by lifestyle factors and psychosocial stress exposures, or other causes may increase the susceptibility to and rate of progression of age-related pathologies. Of note, low-level chronic inflammation is often associated with impaired inflammatory responses to adequate stimuli, such as antigens and vaccines. Growing evidence links chronic inflammation to risk of disorders including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, dementia, and cancer, as well as with conditions such as frailty, functional decline, and disability in activities of daily living.

Data infrastructure for social and behavioral research on aging.

NIA-supported research has improved our knowledge of the fundamental social, behavioral, psychological, and economic factors that influence aging at both the individual and societal levels. Multiple NIA-funded data resources — combining survey, administrative, contextual, and biological data — have enabled rigorous scientific study of these topics. Since 1992, Health and Retirement Study researchers and their international partners have provided a wealth of longitudinal data on aging, dementia, and the role of social institutions and individual life histories on health and well-being at older ages. For more than a decade, the National Health and Aging Trends Study has informed efforts to reduce disability, maximize health and independent functioning, and enhance quality of life at older ages. Through these and other multidisciplinary research approaches, we now have a deeper understanding of the aging process, the underlying causes of health disparities, and the psychosocial and contextual factors that affect health later in life.

Measures of health in old age.

An important conceptual contribution is the use of functional measures in healthy aging research. This concept has changed the care of older adults and laid the foundation of geriatric medicine. Prominent studies such as the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, which explores the determinants and measures of healthy biological aging over time and is the nation’s longest running scientific study of human aging, helped identify functional measures. Additionally, the Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders (LIFE) clinical trial showed that physical activity can help preserve function, including mobility, in older adults at high risk of disability17.

Clinical contributions.

Several rigorous large-scale clinical trials — rare before the 1970s — have yielded important findings. Examples include:

Aspirin for cardiovascular disease. Findings of the Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial found no effect of low-dose aspirin on survival free of persistent disability and dementia and showed a higher risk of hemorrhage18. Findings contributed to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2022 recommendation against initiating low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults 60 years or older.

Testosterone treatment for men. Testosterone supplementation trials in older men with hypogonadism found benefits related to sexual function, anemia, and bone mineral density, but no benefits for slow gait, perceived low energy, and cognition. They also found increases in coronary artery noncalcified plaque (a marker of cardiovascular risk)19.

Hormone therapy for women. Following findings from the Women’s Health Initiative20 on the adverse effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women, subsequent trials have helped clarify benefits and risks. For example, more recent clinical trial findings suggest that estrogen treatment in the early postmenopausal years has benefits for cardiovascular disease prevention21.

Deprescribing. The NIA-supported U.S. Deprescribing Network seeks to reduce or stop the use of unnecessary and potentially harmful medications to improve the health and well-being of older adults. One study showed that providing individualized medication reports made primary care clinicians more likely to perform a thorough medication reconciliation and discuss potentially inappropriate medications with patients22.

Aging research infrastructure and tools.

NIA launched and evolved multiple programs and resources over the past 50 years that provide researchers, academia, and industry with a robust infrastructure for conducting research, developing medicines and other products, bringing together scientists from different disciplines, and training the next generation of investigators. These efforts are supported, in part, by NIA’s robust centers programs, including 37 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers; eight Nathan Shock Centers of Excellence; 15 Edward R. Roybal Centers for Translational Research in the Behavioral and Social Sciences of Aging; 15 Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Centers; 15 Centers on the Demography and Economics of Aging and AD/ADRD; and 18 Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research.

Ongoing challenges and opportunities

Aging is an interplay of many factors that presents both new and evolving research challenges and opportunities. It is increasingly clear that one must look across the full life course to understand the drivers of aging and age-related diseases to consider optimal timepoints for intervention.

Complexity of dementia.

Alzheimer’s and related dementias are heterogeneous diseases, and individuals are often living with more than one underlying dementia pathology. For example, Alzheimer’s pathology (beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles) often co-occurs with blood vessel damage typical of vascular dementia. These diseases also do not affect all populations equally. Compared with White Americans, Hispanic Americans are about 1.5 times as likely to develop dementia, and Black Americans are about twice as likely23, 24. Despite this, dementia is under-diagnosed in these populations, pointing to the need for approaches to understand etiological factors, including social determinants, and improve diagnoses in underserved and minoritized communities.

Multimorbidity.

An estimated 67 percent of people age 65 and older have multiple chronic conditions25. Although combinations of conditions can be managed, sometimes specific disease-treatment interactions are problematic. NIA-funded researchers aim to understand why two or more conditions might occur together in older people, and more importantly, what to do about it.

Disparities in health and life span.

For decades, researchers have investigated the multiple determinants of health and the structural drivers of health inequities. NIA-supported population-based longitudinal studies continue to document large disparities in health and longevity among racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographically defined subgroups in our society, revealing worrying trends in midlife morbidity and mortality in some groups. Other research has shown that discrimination, trauma, and other life events contribute to accelerated aging of the immune system26. Researchers are also examining larger-scale issues, including health care access and delivery, as potential contributors to differences in health and life span. A life course perspective to understanding the mental, physical, and social health of individuals is paramount to better understanding and addressing disparities in health and longevity. The NIA Health Disparities Research Framework27 identifies nine priority populations and guides researchers to consider four key domains and various levels of analysis in aging research using a life course perspective.

Diversity in clinical research.

NIA currently is funding approximately 1,000 active clinical studies using more than 800 sites worldwide. This includes more than 450 active Alzheimer’s and related dementias prevention, treatment, and caregiving clinical trials28. To ensure that discoveries are broadly applicable, a top priority is for clinical trials and observational studies to better represent the affected population’s diversity. NIA resources include the Clinical Research Operations and Management System (CROMS), which provides NIA and grant recipients with real-time tracking, reporting, and management of clinical research enrollment data, including activities and inclusion of participants by sex and gender, race, and ethnicity. OutreachPro helps investigators create customized outreach materials for Alzheimer’s and related dementias clinical research using messages and images that have been tested with underrepresented audiences, including African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian American, and Pacific Islander populations.

Looking forward: What’s on the horizon?

NIA will build on past efforts to achieve even greater successes in aging research. A few big-picture topics include:

Recruiting and training a diverse and inclusive next generation of aging researchers and mentors.

NIA has fostered the development of scientists across the translational research spectrum and continues its commitment to a diverse and inclusive aging-focused workforce. One example is the Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research, a program designed to increase diversity among scientists who conduct social, behavioral, psychological, and economic research on aging. Another is the Butler-Williams Scholars Program, through which NIA provides unique opportunities for junior faculty and new researchers in the field to expand their networks, improve grant-writing skills, and gain a broader understanding of aging research. NIA also offers multiple individual fellowship and career development programs, and institutional training and research education that strongly encourage the participation of individuals from diverse backgrounds.

With the increasing number of older adults, now more than ever we need a robust clinical workforce, including geriatricians, palliative care specialists, nurses, geriatric psychologists, psychiatrists, and many others providing care to older adults. NIA will continue its efforts to attract and further expand the next generation of physicians and scientists to pursue careers in aging-related fields by funding training programs in geriatric medicine, geroscience, translational aging research, and related subspecialties.

Supporting small businesses.

In recent years, NIA has awarded more than $130 million per year29 in research and development grants annually through its Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer programs. One grant supported researchers in developing the first commercial blood test for Alzheimer’s disease. Another led to the development of a wearable sensor with automatic fall detection, fall risk assessment, and activity monitoring that has been integrated into widely available medical alert devices sold at mass-market retailers. NIA also recently launched a Start-Up Challenge and Accelerator initiative to stimulate innovation in aging research by providing cash prizes as well as entrepreneurial support and mentorship to individuals from diverse racial, ethnic, and professional backgrounds.

Health span versus life span.

Life span remains a bedrock metric for aging research; however, health span — the portion of life spent in good health — is arguably just as crucial. Studies in the basic biology of aging using laboratory animals, now extended to human populations, have demonstrated that the rate of aging can be slowed, suggesting that targeting aging will also slow the appearance and reduce the burden of numerous diseases. Improvements in preventing and managing chronic disease, delaying the onset of associated disabilities, and understanding risk factors for age-related morbidity will also help to maintain function and prolong good health.

Precision medicine.

The complexity of aging conditions and diseases, including dementia, underscores the importance of personalized medicine — delivering the right treatment in the right place at the right time for each individual. It is essential in tandem to ensure clinical research is inclusive so that study results are applicable to all populations.

Data access and real-world data.

Working collaboratively, NIA-supported researchers employ an open-science, open-source approach at every step of the translational research process to discover new and better targets for disease treatment and prevention, produce and analyze comprehensive and shareable sets of molecular, clinical, survey, and administrative data, including data from electronic health records and digital devices, and develop high-quality tools to move discoveries from the bench to the bedside.

Dementia care and caregiving.

NIA leads the nation in advancing dementia care and caregiving research. NIA will continue to fund studies on access and quality, improving models of care across different settings, and care coordination. Additionally, we support studies on the ways in which regulatory and socioeconomic incentives and constraints affect care access, quality, and health outcomes. One important goal is to facilitate intervention testing in more diverse older adult populations where they already live and receive care.

Palliative care.

NIA has been named the lead institute for coordination of palliative care research across NIH. As a first step to advance research that aims to improve quality of life for people with serious illness and their families, NIA and partner institutes seek to fund a new consortium that will generate scientific knowledge, foster training and mentoring, and engage health care systems and community-based organizations as research partners. The consortium would also facilitate research to understand and address disparities in access, quality, and use of palliative care services.

Exposome.

People are exposed to many environmental factors over the course of their life, from toxicants and pollutants in the air and water to social dynamics and relationships. The sum of these lifetime exposures to external factors is called the exposome. NIA-funded research is already finding compelling data indicating that these exposures can have a direct effect on human health, including contributing to the complexities and disparities associated with dementia.

Behavior change.

Because individual health behaviors and the practices of health systems and social institutions play major roles in shaping health outcomes for older adults, NIA promotes a range of rigorous approaches to understanding and advancing behavior change at the individual and organizational levels. This includes principle-based behavioral interventions, behavioral economic approaches to improve health behaviors and health care delivery, and large-scale pragmatic trials embedded in health systems to optimize care and care coordination. The NIH Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development30 offers guidance on best practices for generating, testing, and implementing effective behavioral interventions that can be delivered in real-world settings.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Rapidly advancing technologies will be increasingly prominent in aging research, and NIA is working to ensure that data can be used by advancing computing systems and processes. NIA is supporting a growing portfolio of infrastructure, data resources, and research that leverages artificial intelligence and machine learning to improve the health and well-being of older adults.

Summary: Here’s to the next 50 years

Fifty years ago, scientists interested in studying aging or age-related diseases fought enormous skepticism. Today, important findings of aging research appear regularly in scientific journals and major media outlets. These efforts are only possible through meaningful collaboration and innovative partnerships among the research community, industry, stakeholder organizations, other federal agencies, and the broader public.

As we embark on the next 50 years, we look forward to building on this momentum by welcoming a new generation of investigators from the full breadth of scientific disciplines, geriatricians and other aging-focused clinical providers, and others to an aging research career. Individuals who are interested in these fields are in the right place at the right time! We encourage you to learn more about and leverage all the platforms, infrastructure, and data resources available through NIA and our grant recipients. Together, we will continue to make crucial scientific advances in extending and enhancing the health and well-being of older adults.

Key points:

NIA-funded research has contributed to understanding the biological, clinical, and functional changes that occur with aging and the diseases and conditions associated with growing older.

Discoveries in the biology of aging, causes of diseases and conditions, social determinants of health, and structural drivers of health inequities point to interventions and behaviors that can improve health span for some people, and underscore new challenges and opportunities for aging research.

With the goal of achieving even greater successes, NIA will continue to fund a broad and robust research portfolio, and increase efforts to recruit and train a diverse and inclusive next generation of aging researchers.

Footnotes

This paper is part of the Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the National Institute on Aging special collection edited by Alexander Smith and George Kuchel. Once complete, you can explore the rest of the collection here: https://agsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/hub/journal/15325415/special-collections

Conflict of Interest

The authors are all current or recent employees of the National Institute on Aging.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ageing and Health. World Health Organization (online). Available at: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed December 12, 2023.

- 2.Global Health Estimates: Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. World Health Organization (online). Available at: www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy. Accessed December 12, 2023.

- 3.Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112(49):15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.High and Rising Mortality Rates Among Working-Age Adults. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (online). Available at: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/25976/high-and-rising-mortality-rates-among-working-age-adults. Accessed December 12, 2023. [PubMed]

- 5.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Buchanich JM, Bobby KJ, Zimmerman EB, Blackburn SM. Changes in midlife death rates across racial and ethnic groups in the United States: systematic analysis of vital statistics. BMJ 2018;362:k3096. Published 2018 Aug 15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolf SH. Falling Behind: The Growing Gap in Life Expectancy Between the United States and Other Countries, 1933–2021. Am J Public Health 2023;113(9):970–980. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The SPRINT MIND Investigators for the SPRINT Research Group. Effect of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control on Probable Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019;321(6):553–561. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The SPRINT MIND Investigators for the SPRINT Research Group. Association of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control With Cerebral White Matter Lesions. JAMA 2019;322(6):524–534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rebok GW, Ball K, Guey LT, et al. Ten-year effects of the advanced cognitive training for independent and vital elderly cognitive training trial on cognition and everyday functioning in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62(1):16–24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin FR, Pike JR, Albert MS, et al. Hearing intervention versus health education control to reduce cognitive decline in older adults with hearing loss in the USA (ACHIEVE): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2023;402(10404):786–797. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01406-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mintun MA, Lo AC, Duggan Evans C, et al. Donanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2021;384(18):1691–1704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yousefzadeh MJ, Flores RR, Zhu Y, et al. An aged immune system drives senescence and ageing of solid organs. Nature 2021;594(7861):100–105. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03547-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraus WE, Bhapkar M, Huffman KM, et al. 2 years of calorie restriction and cardiometabolic risk (CALERIE): exploratory outcomes of a multicentre, phase 2, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019;7(9):673–683. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30151-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu CE, Oshima J, Fu YH, et al. Positional cloning of the Werner’s syndrome gene. Science 1996;272(5259):258–262. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capell BC, Collins FS. Human laminopathies: nuclei gone genetically awry. Nat Rev Genet 2006;7(12):940–952. doi: 10.1038/nrg1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sebastiani P, Perls TT. The genetics of extreme longevity: lessons from the new England centenarian study. Front Genet 2012;3:277. Published 2012 Nov 30. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Anton SD, et al. Impact and Lessons From the Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders (LIFE) Clinical Trials of Physical Activity to Prevent Mobility Disability. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68(4):872–881. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. Effect of Aspirin on Disability-free Survival in the Healthy Elderly. N Engl J Med 2018;379(16):1499–1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snyder PJ, Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, et al. Lessons From the Testosterone Trials. Endocr Rev 2018;39(3):369–386. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaMonte MJ, Manson JE, Anderson GL, et al. Contributions of the Women’s Health Initiative to Cardiovascular Research: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80(3):256–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al. Vascular Effects of Early versus Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol. N Engl J Med 2016;374(13):1221–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mecca MC, Zenoni M, Fried TR. Primary care clinicians’ use of deprescribing recommendations: A mixed-methods study. Patient Educ Couns 2022;105(8):2715–2720. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manly JJ, Jones RN, Langa KM, et al. Estimating the Prevalence of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment in the US: The 2016 Health and Retirement Study Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol Project. JAMA Neurol 2022;79(12):1242–1249. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.3543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, McAninch EA, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020–2060). Alzheimers Dement 2021;17(12):1966–1975. doi: 10.1002/alz.12362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salive ME. Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev 2013;35:75–83. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxs009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klopack ET, Crimmins EM, Cole SW, Seeman TE, Carroll JE. Social stressors associated with age-related T lymphocyte percentages in older US adults: Evidence from the US Health and Retirement Study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022;119(25):e2202780119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2202780119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Disparities Framework. National Institute on Aging (online). Available at: www.nia.nih.gov/research/osp/framework. Accessed December 6, 2023.

- 28.NIA-Funded Active Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias Clinical Trials and Studies. National Institute on Aging (online). Available at: www.nia.nih.gov/research/ongoing-AD-trials. Accessed November 15, 2023.

- 29.Year Fiscal 2024. Budget. National Institute on Aging (online) Available at: www.nia.nih.gov/about/budget/fiscal-year-2024-budget. Accessed November 13, 2023.

- 30.NIH Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development. National Institute on Aging (online). Available at: www.nia.nih.gov/research/dbsr/nih-stage-model-behavioral-intervention-development. Accessed November 24, 2023.