Abstract

Objective

Primary resistance to trastuzumab frequently occurs in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive (+) breast cancer patients and remains a clinical challenge. Pyrotinib is a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor that has shown efficacy in the treatment of HER2+ breast cancer. However, the efficacy of pyrotinib in HER2+ breast cancer with primary trastuzumab resistance is unknown.

Methods

HER2+ breast cancer cells sensitive or primarily resistant to trastuzumab were treated with trastuzumab, pyrotinib, or the combination. Cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and HER2 downstream signal pathways were analyzed. The effects of pyrotinib plus trastuzumab and pertuzumab plus trastuzumab were compared in breast cancer cells in vitro and a xenograft mouse model with primary resistance to trastuzumab.

Results

Pyrotinib had a therapeutic effect on trastuzumab-sensitive HER2+ breast cancer cells by inhibiting phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) and rat sarcoma virus (RAS)/rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK) pathways. In primary trastuzumab-resistant cells, pyrotinib inhibited cell growth, migration, invasion, and HER2 downstream pathways, whereas trastuzumab had no effects. The combination with trastuzumab did not show increased effects compared with pyrotinib alone. Compared with pertuzumab plus trastuzumab, pyrotinib plus trastuzumab was more effective in inhibiting cell proliferation and HER2 downstream pathways in breast cancer cells and tumor growth in a trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ breast cancer xenograft model.

Conclusions

Pyrotinib-containing treatments exhibited anti-cancer effects in HER2+ breast cancer cells sensitive and with primary resistance to trastuzumab. Notably, pyrotinib plus trastuzumab was more effective than trastuzumab plus pertuzumab in inhibiting tumor growth and HER2 downstream pathways in HER2+ breast cancer with primary resistance to trastuzumab. These findings support clinical testing of the therapeutic efficacy of dual anti-HER2 treatment combining an intracellular small molecule with an extracellular antibody.

Keywords: Breast cancer, HER2, pyrotinib, trastuzumab, primary resistance, pertuzumab

Introduction

Overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is present in 15%−20% of all breast cancers (1,2) and is associated with a less favorable prognosis. Despite the substantial survival benefits from trastuzumab, the first monoclonal antibody targeting HER2 (3), approximately 6.8%−15.0% of HER2-positive (HER2+) early-stage breast cancer patients experience primary resistance to trastuzumab (4,5), which remains a challenge for patient treatment.

A series of HER2-targeted therapeutic drugs, including pertuzumab, were developed to address trastuzumab resistance (6). From the results of the NeoSphere trial, the combination of pertuzumab and trastuzumab has become the established first-line treatment option for neoadjuvant therapy in HER2+ breast cancer patients (2,7-9). However, the combination of trastuzumab and pertuzumab did not effectively inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer cells with primary resistance to trastuzumab (10,11). Therefore, the trastuzumab and pertuzumab combination treatment may not be the most suitable option for patients with primary trastuzumab resistance. Further exploration of novel treatment strategies is required to improve patient prognosis.

Pyrotinib is a novel small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that selectively targets HER1, HER2 and HER4. The TKI forms irreversible bonds with the intracellular domains of HER proteins to inhibit downstream signaling pathways, thereby inhibiting these receptors through a mechanism distinct from that of trastuzumab or pertuzumab (12,13). Studies have shown that pyrotinib significantly improved the survival of patients with advanced breast cancer who developed acquired resistance to trastuzumab (14,15). Unlike patients with acquired resistance, individuals with primary resistance tend to exhibit more aggressive disease characteristics and may not benefit from the reuse of trastuzumab (4,16). Whether pyrotinib represents an effective treatment for breast cancer patients with primary resistance to trastuzumab remains unclear.

To address this gap, we analyzed the therapeutic effect of pyrotinib and the anti-cancer efficacy of pyrotinib alone and in drug combinations in trastuzumab-sensitive and primary resistant HER2+ breast cancer cells and an in vivo xenograft model. These findings may serve as a foundation for the development of novel treatment strategies for HER2+ breast cancer patients with primary resistance to trastuzumab.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and chemicals

SK-BR-3, BT-474, BT-549, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and MCF-7 cells were purchased from the Shanghai Zhong Qiao Xin Zhou Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). HCC1569 and HCC1954 cells were purchased from the Nanjing Cobioer Biotechnology Corporation (Nanjing, China). HCC1937 cells were purchased from the Procell Life Science and Technology Co., Ltd (Wuhan, China). HCC1806 cells were purchased from the BeNa Culture Collection (Kunshan, China).

SK-BR-3, BT-474, HCC1569, HCC1954, HCC1806, MDA-MB-231, and HCC1937 cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Corning, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, ExCell Bio, Suzhou, China) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. MCF-7 cells were grown in MEM medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 0.005 mg/mL bovine insulin (Solarbio, Beijing, China). BT-549 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 0.023 IU/mL insulin (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). MDA-MB-468 cells were cultured in DMEM (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. All cell lines were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. All cell lines have been authenticated by the Shanghai Biowing Applied Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China), and the absence of mycoplasma contamination was confirmed before conducting the experiments.

Pyrotinib was obtained from the Jiangsu Hengrui Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. (Lianyungang, China). Pyrotinib was dissolved in sterilized water at a concentration of 10 mmol/L and stored at −20 °C. Trastuzumab (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, USA) was obtained from the Second Hospital of Shandong University. Pertuzumab (Genentech) at a concentration of 30 mg/mL was obtained from a pharmacy and stored at 4 °C.

Cell proliferation assay

Breast cancer cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 2.5×103−2.0×104 cells per well. After adherence, cells were treated with vehicle, trastuzumab, pyrotinib, or pertuzumab. Five wells were set for each treatment. After the indicated treatment times, cells were incubated with the Cell Counting Kit-8 reagent (Elabscience, Wuhan, China) for 3−4 h, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Colony formation assay

Colony formation assay was performed as previously described (17). Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 500−1,000 cells per well. After adherence, cells were treated with vehicle, trastuzumab (10 µg/mL), pyrotinib (100 nmol/L), or a combination of the two drugs for 3 d. The medium was then replaced with fresh medium, and cells were incubated for 7−14 d. Cell colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20−30 min at room temperature. The colonies were photographed, and the number of stained colonies containing >50 cells was counted with ImageJ software (Version 1.52v; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). All experiments were performed at least three times.

Wound healing assay

Wound healing assay was performed using scratch inserts (IBIDI, Regensburg, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, scratch inserts were placed into 12-well plates. Breast cancer cells were collected and resuspended in complete medium, and 3.3×104−5.5×104 cells were seeded into each well of the scratch insert. After adherence, the scratch inserts were removed, and fresh RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% FBS was added. Cells were treated with vehicle, trastuzumab (10 µg/mL), pyrotinib (100 nmol/L), or trastuzumab (10 µg/mL) combined with pyrotinib (100 nmol/L). Photographs were taken at 0, 24 and 48 h with an inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The percentage of wound closure at 24 and 48 h was estimated from the closed area of migratory cells by using ImageJ software. The formula for calculating the scratch healing rate is: wound closure (%) = (initial scratched area − scratch area at the time point)/initial scratched area × 100%. All experiments were performed at least three times.

Cell migration and invasion assays

For migration assays, transwell chambers (8 µm pore size, Corning) were placed into 24-well plates. SK-BR-3 and HCC1954 cells (3.0×104−1.0×105 cells in 200 µL complete medium) were seeded into the upper chamber of the transwell and 600 µL medium was added to the lower chamber. After adherence, the medium in the upper chamber was replaced with 200 µL of RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin, and the medium in the lower chamber was replaced with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS. Cells were treated with vehicle, trastuzumab (10 µg/mL), pyrotinib (100 nmol/L), or trastuzumab (10 µg/mL) combined with pyrotinib (100 nmol/L). Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24−48 h. The cells in the upper chamber were wiped away by cotton swabs. Cells on the lower surface of the polycarbonate membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde fixative for 30 min at room temperature, followed by staining with crystal violet for 20 min. An inverted microscope (Olympus) was used to take pictures of three random fields (200×). Cells were counted and the average was calculated.

For invasion assays, matrigel (Corning) and pre-cooled RPMI 1640 medium were mixed at a ratio of 1:9, and 50 µL of the mixture was spread evenly in the top transwell chamber, in 24-well plates, to prepare a basement membrane. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The subsequent steps were the same as those described for the migration assay.

Western blot analysis

Breast cancer cells were seeded into 6-well plates and treated with the indicated drugs. Preparation of whole cell protein lysates and western blot analysis were performed as previously described (18). Briefly, the treated cells were washed three times with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and lysed with radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer containing 1× phosphatase inhibitors, 1× protease inhibitors, and 1× phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime) on ice. The lysates were centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected; the BCA protein concentration assay kit (Beyotime) was used to determine the protein concentration of the supernatant. The protein samples were diluted with 5× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) sample loading buffer (Beyotime) and heated at 95 °C in a metal bath for 10 min. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After blocking with Tris-buffered saline with tween-20 containing 5% non-fat milk (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) at room temperature for 1 h, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China, Cat#ZB-2301) for 1 h at room temperature. Bands were detected with Immobilon Western horseradish peroxidase (HRP) substrate (Millipore). Protein bands were quantified using the Tanon Image software and analyzed with ImageJ software. The primary antibodies were as follows: phosphorylated (p) HER2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA, Cat#2243S), HER2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat#ab134182), pAKT (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#4060S), AKT (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#4691S), pERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#4370S), ERK1/2 (Abcam, Cat#ab17942), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Proteintech, Wuhan, China, Cat#10494-1-AP).

Tumor xenograft model

Four-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the Beijing HFK Bioscience (Beijing, China). Food and water were changed twice a week. Mice were acclimated to the environment for 3−5 d. All animal studies were performed following ethical regulations and approval by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Hospital of Shandong University.

HCC1954 cells were resuspended in PBS and mixed with Matrigel (Corning) in a volume ratio of 1:1. The mixture was implanted subcutaneously into the right flanks of mice with 4.0×106 cells per site. When the mean tumor volume reached approximately 200 mm3, mice were randomized into five groups: control, trastuzumab, pyrotinib, trastuzumab+pyrotinib, and trastuzumab+pertuzumab (n=6/group). Trastuzumab was administered by intraperitoneal injection twice a week at a dose of 10 mg/kg; pertuzumab was administered by intraperitoneal injection twice in the first week at a dose of 6 mg/kg followed by 6 mg/kg once a week; and pyrotinib was administered daily by oral gavage at a dose of 30 mg/kg. Tumors were measured with a digital caliper twice a week and tumor volumes were calculated using the following formula: volume (mm3) = (length × width2)/2. Mice were sacrificed after 24 d of treatment under anesthetization with isoflurane. Tumors were removed for subsequent analyses.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tumor tissues from tumor xenograft models were immersed in 4% formalin for fixation, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 3 µm-thick sections. Sections were stained with primary antibodies against pHER2, pAKT, pERK, and Ki-67 using a biotin-streptavidin HRP detection system (ZSGB-BIO) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, tumor tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and boiled in a pressure cooker with repair solution for antigen retrieval for 2.5 min. After treatment with endogenous peroxidase blocker for 10 min, sections were incubated with normal goat serum blocking solution (ZSGB-BIO) for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight or at room temperature for 1 h. The primary antibodies are as follows: pHER2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#2243S), pAKT (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#3787S), pERK (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#4370S), and Ki-67 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat#9449T). The sections were then incubated with HRP-coupled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody, and HRP activity was detected by 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride solution (ZSGB-BIO). Sections were scanned by a Digital Pathology Slide Scanner (400×) (NanoZoomer, Hamamatsu, Japan).

IHC scoring was performed as previously described (19). Briefly, IHC scoring was based on the proportion and intensity of positively stained invasive breast cancer cells on the slides. The proportion of positive tumor cells was recorded as a percentage. The intensity scores represent the average staining intensity of the positive tumor cells (negative =0; weak staining =1; moderate staining =2; and strong staining =3). The proportion and intensity scores were then multiplied to obtain a total IHC score, which ranges from 0 to 300.

Statistical analysis

All descriptive statistics are presented as  . Significant differences were compared using Student’s t test for two groups or one-way ANOVA accompanied by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test for more than two groups. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (Version 8.0.2; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The P value <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

. Significant differences were compared using Student’s t test for two groups or one-way ANOVA accompanied by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test for more than two groups. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (Version 8.0.2; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The P value <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Pyrotinib inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion, and HER2 downstream pathways in trastuzumab-sensitive HER2+ breast cancer cells

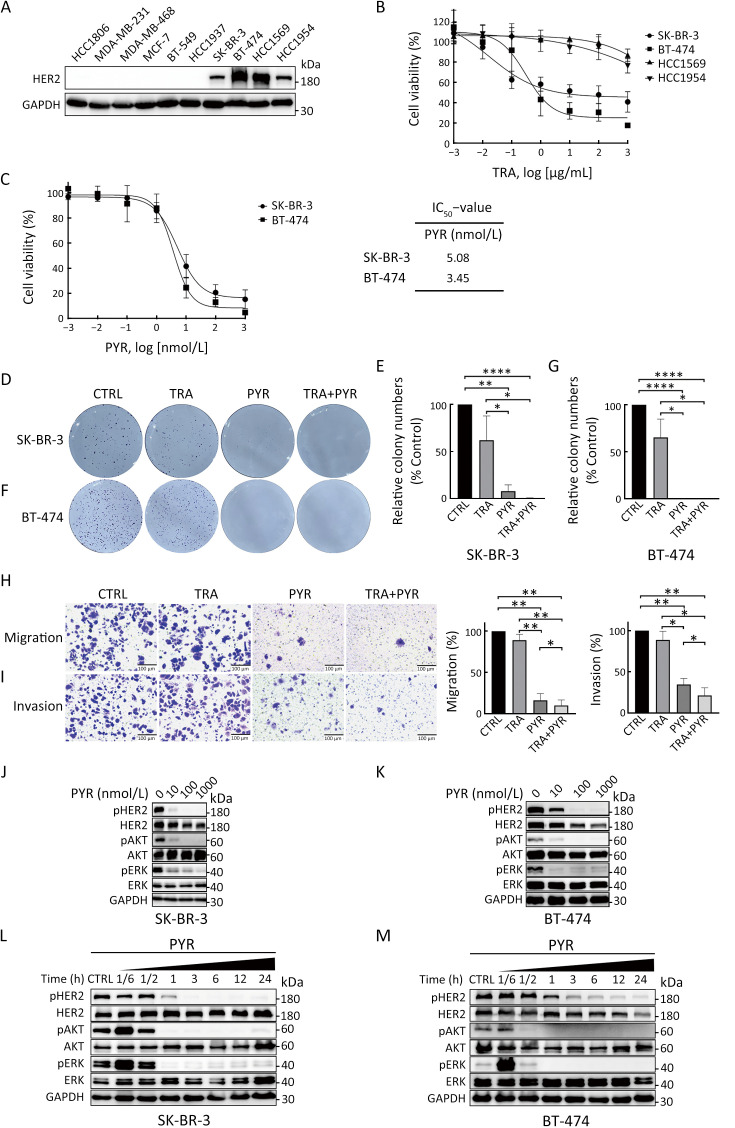

We first analyzed HER2 expression in 10 human breast cancer cell lines. Western blot results showed that SK-BR-3, BT-474, HCC1569 and HCC1954 were HER2+ cell lines (Figure 1A). We thus selected these HER2+ cell lines for subsequent studies. We then used cell proliferation assays to analyze the sensitivity of the HER2+ breast cancer cell lines to trastuzumab treatment. The results showed that SK-BR-3 and BT-474 cell lines were sensitive to trastuzumab treatment, while HCC1569 and HCC1954 cell lines were resistant to trastuzumab treatment (Figure 1B), which are consistent with a previous report (20).

Figure 1.

Pyrotinib inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion, and HER2 downstream pathways in trastuzumab-sensitive HER2+ breast cancer cells. (A) HER2 expression in human breast cancer cell lines was examined by western blot; (B) Dose-response curves in SK-BR-3, BT-474, HCC1569, and HCC1954 cells after 6 d of treatment with TRA; (C) Dose-response curves in SK-BR-3 and BT-474 cells after 3 d of treatment with PYR. IC50 values were determined after 3 d treatment with PYR; (D−G) Colony formation assays in SK-BR-3 (D,E) and BT-474 cells (F,G) treated with vehicle (CTRL), TRA (10 µg/mL), PYR (100 nmol/L), or a combination treatment (TRA+PYR). Relative number of colonies (normalized to CTRL) was quantified using ImageJ; (H,I) Migration (H) and invasion (I) of SK-BR-3 cells were evaluated by transwell assays without or with matrigel-coated inserts; (J−M) SK-BR-3 (J,L) and BT-474 (K,M) cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PYR for 24 h or indicated times with PYR. The levels of indicated protein were assessed by western blot. The quantifications of blots are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. TRA, trastuzumab; PYR, pyrotinib; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ****, P<0.0001.

To examine the effect of pyrotinib in trastuzumab-sensitive HER2+ breast cancer cells, we performed cell proliferation assays. Treatment with pyrotinib markedly reduced the proliferation of trastuzumab-sensitive cells (Figure 1C). Colony formation assay was performed to analyze the long-term effect of trastuzumab, pyrotinib, or the combination on the proliferation of trastuzumab-sensitive cells. Cells in the pyrotinib-containing treatment groups showed significantly reduced cell proliferation compared with controls (Figure 1D−G). Treatment of trastuzumab alone decreased colony formation ability of SK-BR-3 and BT-474 cells compared with controls, but the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 1D−G).

We next assessed the effect of trastuzumab and pyrotinib on the migration and invasion activities of SK-BR-3 cells using transwell assays. BT-474 cells were not used in this assay because of their low migration ability. Both the migration and invasion activities of SK-BR-3 cells were significantly suppressed by pyrotinib-containing treatments compared with controls (Figure 1H,I). Migration and invasion were slightly inhibited by trastuzumab, but there was no significant difference compared with the control group (Figure 1H,I).

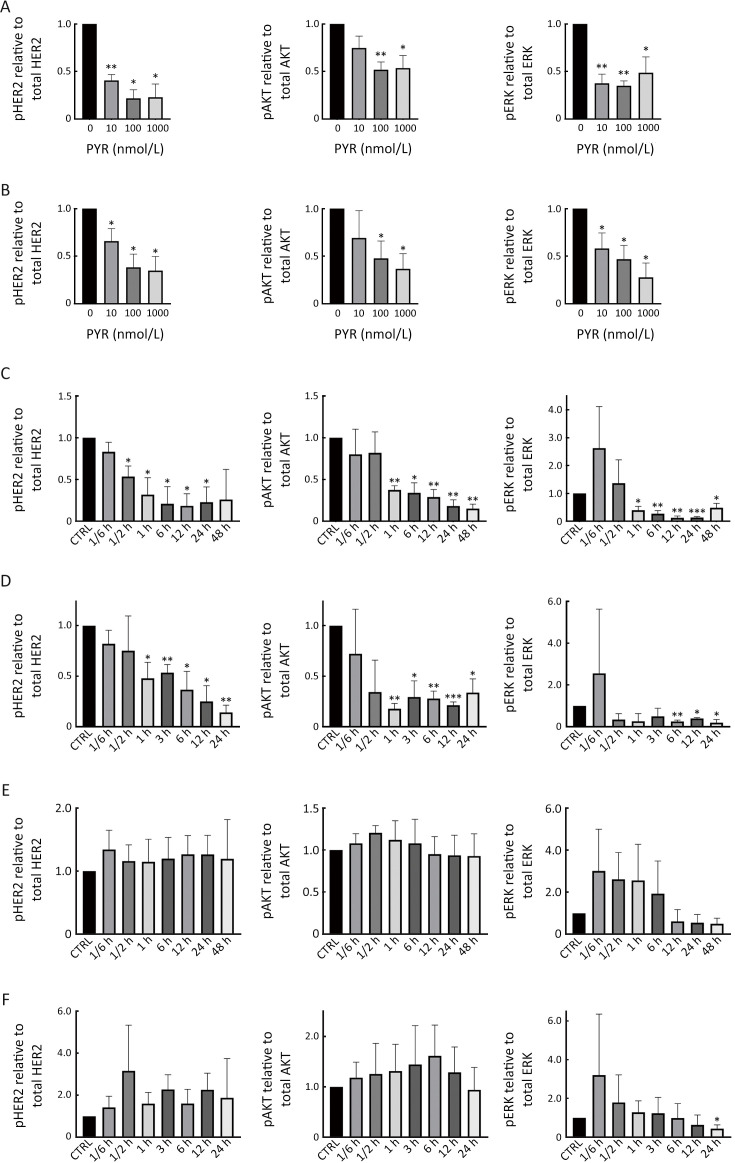

We then evaluated whether HER2 signaling and downstream pathways in trastuzumab-sensitive cells were affected by pyrotinib. Pyrotinib treatment led to markedly reduced pHER2 levels and inhibited downstream pathways, as assessed by phosphorylated protein kinase B (pAKT) and phosphorylated extracellular-signal regulated kinase (pERK), in trastuzumab-sensitive cells in a dose-dependent (Figure 1J,K, Supplementary Figure S1A,B) and time-dependent manner compared with controls (Figure 1L,M, Supplementary Figure S1C,D). Together, these results showed that pyrotinib inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion, and HER2 downstream pathways in trastuzumab-sensitive HER2+ breast cancer cells.

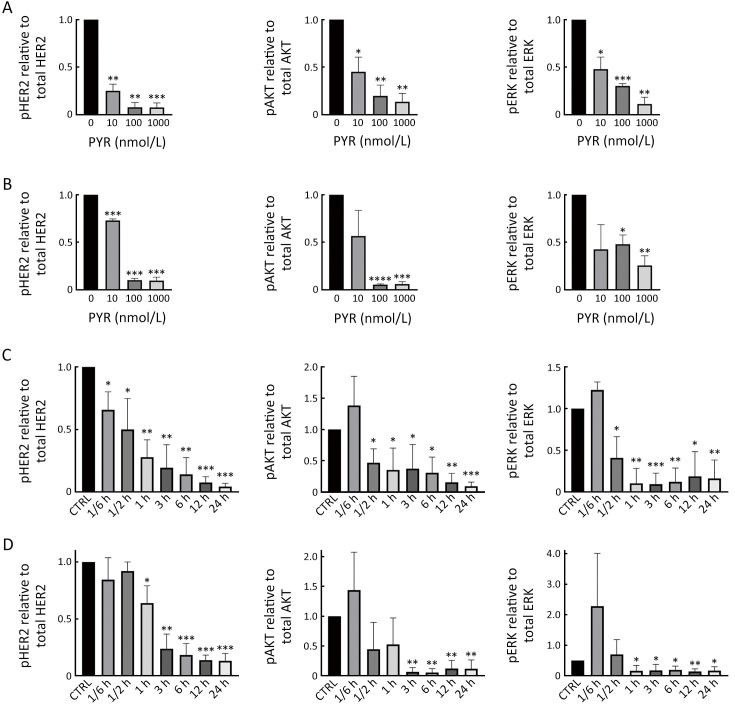

Figure S1.

Pyrotinib inhibits HER2 downstream pathways in trastuzumab-sensitive HER2+ breast cancer cells. (A,B) SK-BR-3 (A) and BT-474 (B) cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PYR for 24 h; (C,D) SK-BR-3 (C) and BT-474 (D) cells were treated with PYR for the indicated times. All the levels of pHER2, HER2, pAKT, AKT, pERK, ERK, and GAPDH were assessed by western blot. The quantifications of blots are shown above. PYR, pyrotinib; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

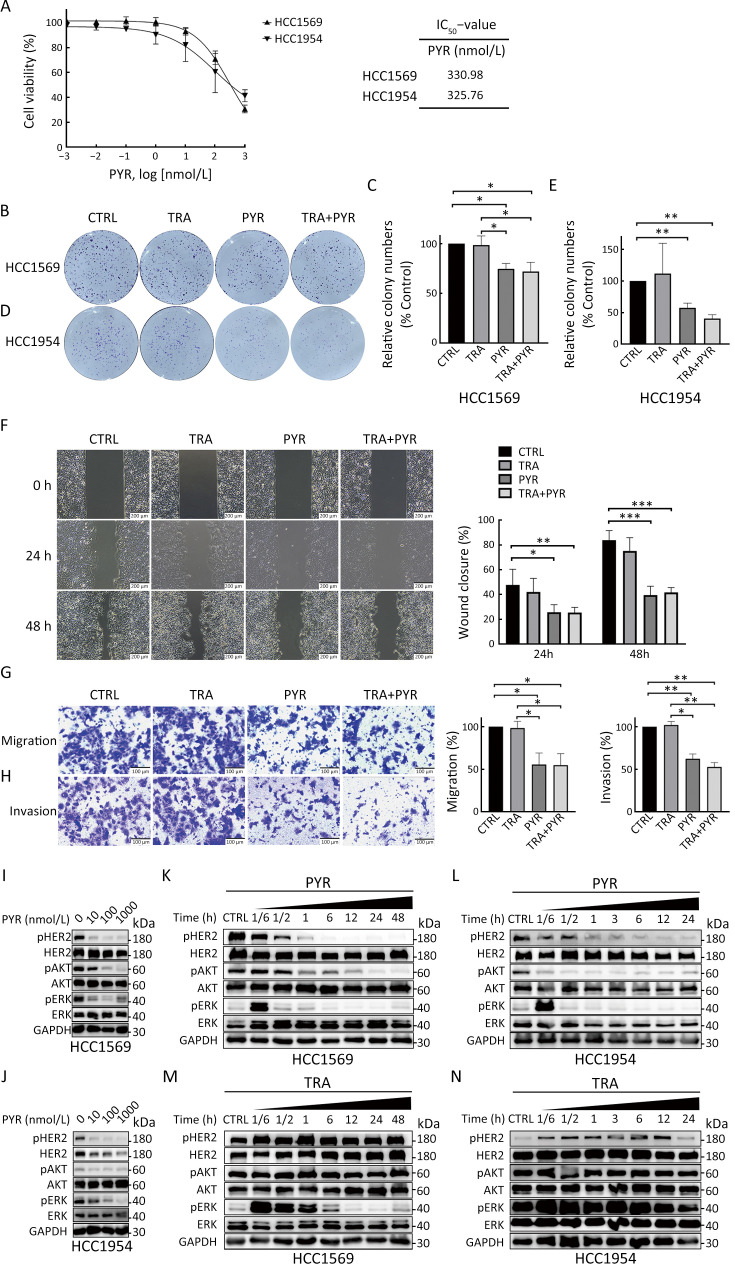

Pyrotinib inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion, and HER2 downstream pathways in trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ breast cancer cells

We next investigated the effect of pyrotinib on HER2+ breast cancer cells with primary resistance to trastuzumab (HCC1569 and HCC1954). The proliferation of HCC1569 and HCC1954 cells was markedly inhibited by pyrotinib but not trastuzumab (Figure 1B, Figure 2A). The IC50 values of pyrotinib in HCC1569 and HCC1954 cells were much higher compared with those in trastuzumab-sensitive cells (Figure 1C, Figure 2A). Colony formation of trastuzumab-resistant cells was also inhibited by treatment with pyrotinib or pyrotinib plus trastuzumab, but not by trastuzumab alone, compared with controls (Figure 2B−E). The addition of trastuzumab to pyrotinib did not further reduce the colony formation activity of trastuzumab-resistant cell lines compared with pyrotinib alone.

Figure 2.

Pyrotinib inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion, and HER2 downstream pathways in trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ breast cancer cells. (A) Dose-response curves of HCC1569 and HCC1954 cells after 3 d of treatment with PYR. IC50 values were determined after 3 d of treatment with PYR; (B−E) Colony formation assays in HCC1569 (B,C) and HCC1954 (D,E) cells treated with CTRL, trastuzumab (TRA, 10 µg/mL), PYR (100 nmol/L), or TRA+PYR. Relative number of colonies (normalized to CTRL) was quantified using ImageJ; (F) Wound healing assay for HCC1954 cells treated with CTRL, TRA, PYR, and TRA+PYR. Images were taken at 0, 24, and 48 h; (G,H) Migration (G) and invasion (H) of HCC1954 cells were evaluated by transwell assays without or with matrigel-coated insert; (I−L) HCC1569 (I,K) and HCC1954 (J,L) cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PYR for 24 h or indicated times with PYR. The levels of indicated protein were assessed by western blot; (M,N) HCC1569 (M) and HCC1954 (N) cells were treated with TRA for the indicated times. The levels of pHER2, HER2, pAKT, AKT, pERK, ERK, and GAPDH were assessed by western blot. The quantifications of blots are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. TRA, trastuzumab; PYR, pyrotinib; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Wound healing assay and transwell assays were conducted to determine the effect of pyrotinib and trastuzumab on HCC1954 cells. HCC1569 cells were not used in these assays because of their low migration ability. Both migration and invasion of HCC1954 cells were suppressed by pyrotinib alone or pyrotinib plus trastuzumab compared with controls, but not trastuzumab. The combination of the two drugs did not further suppress the migration and invasion of HCC1954 cells compared with pyrotinib alone (Figure 2F−H).

We next examined HER2 and the downstream pathways in HCC1569 and HCC1954 cells treated with trastuzumab and pyrotinib. Treatment with pyrotinib alone resulted in reduced levels of pHER2, pAKT, and pERK in a dose-dependent (Figure 2I,J, Supplementary Figure S2A,B) and time-dependent manner (Figure 2K,L, Supplementary Figure S2C,D) in trastuzumab-resistant cells compared with controls. Trastuzumab did not inhibit the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway (Figure 2M,N, Supplementary Figure S2E,F). Together, these results showed that pyrotinib inhibited proliferation, migration, invasion, and HER2 downstream pathways in trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ breast cancer cells, whereas trastuzumab did not exert these effects.

Figure S2.

Pyrotinib inhibits HER2 downstream pathways in trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ breast cancer cells. (A,B) HCC1569 (A) and HCC1954 (B) cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PYR for 24 h; (C,D) HCC1569 (C) and HCC1954 (D) cells were treated with PYR for the indicated times; (E,F) HCC1569 (E) and HCC1954 (F) cells were treated with TRA for the indicated times. All the levels of pHER2, HER2, pAKT, AKT, pERK, ERK, and GAPDH were assessed by western blot. The quantifications of blots are shown above. PYR, pyrotinib; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

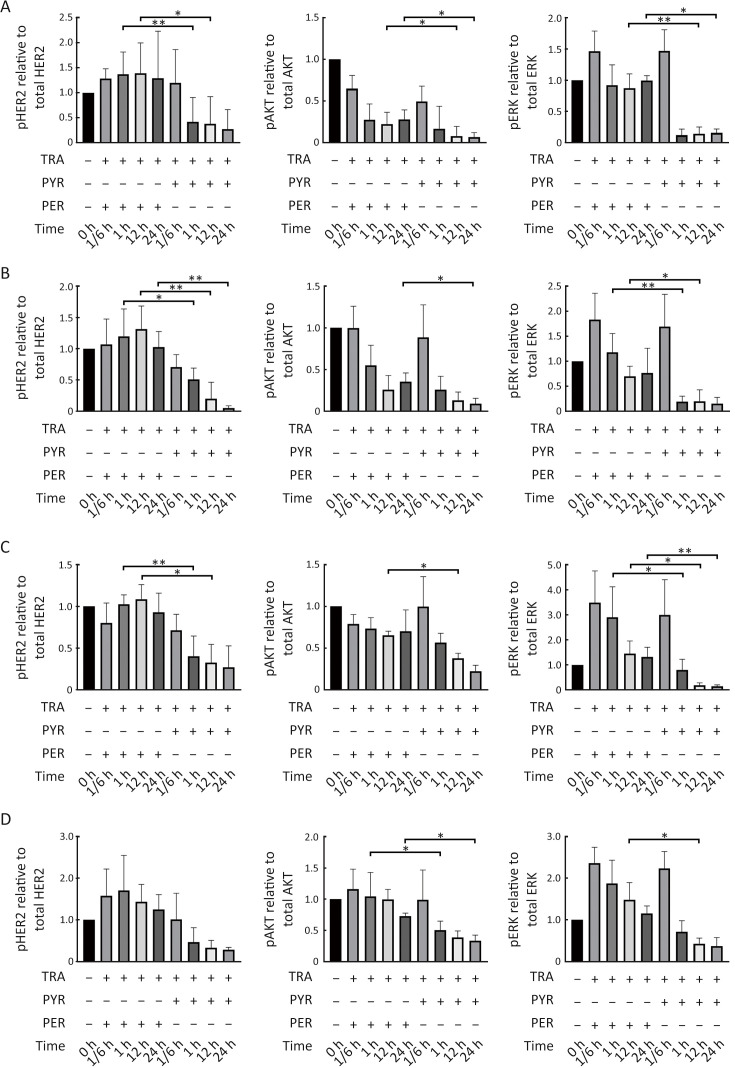

Pyrotinib is superior to pertuzumab in inhibiting proliferation and HER2 downstream pathways in HER2+ breast cancer cells

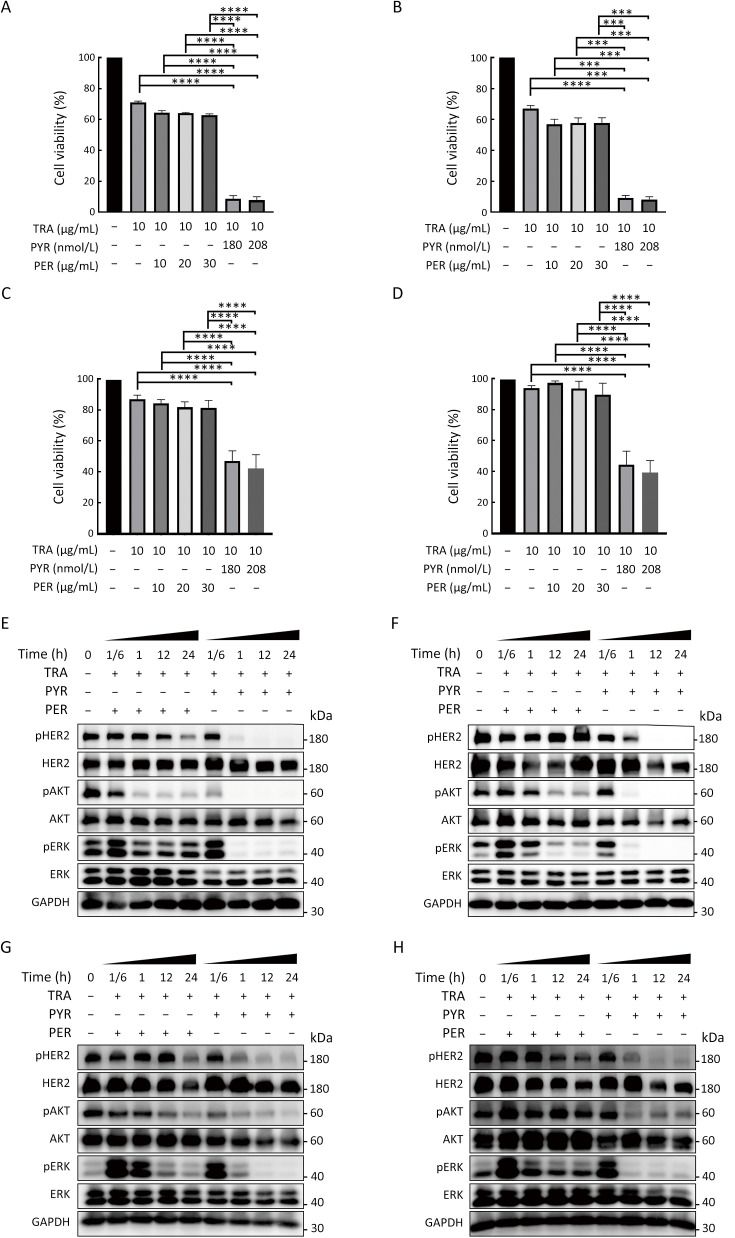

We next compared the effects of trastuzumab with pyrotinib or pertuzumab on trastuzumab-sensitive and trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ breast cancer cells. The cell lines were treated with trastuzumab plus pyrotinib or pertuzumab at concentrations adopted from the in vivo plasma concentrations of pyrotinib or pertuzumab reported in previous phase I clinical studies (21,22). Pyrotinib plus trastuzumab resulted in significantly higher inhibition of cell growth than pertuzumab plus trastuzumab (Figure 3A−D). We next evaluated the effects of the combination treatments on HER2 downstream pathways. The inhibitory effect of pyrotinib combined with trastuzumab on pHER2, PI3K/AKT, and rat sarcoma virus (RAS)/rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK pathways was stronger than that of pertuzumab combined with trastuzumab (Figure 3E−H, Supplementary Figure S3A−D). Taken together, our results showed the superior effects of pyrotinib plus trastuzumab compared with pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in treating trastuzumab-sensitive and trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ breast cancer cells.

Figure 3.

Pyrotinib is superior to pertuzumab in inhibiting proliferation and HER2 downstream pathway in HER2+ breast cancer cells. (A−D) SK-BR-3 (A), BT-474 (B), HCC1569 (C), and HCC1954 (D) cell lines were treated with TRA, TRA+PYR, or TRA+ PER at the indicated concentrations for 3 d. Proliferation of breast cancer cells was analyzed and normalized to CTRL (%); (E−H) SK-BR-3 (E), BT-474 (F), HCC1569 (G), and HCC1954 (H) cells were treated with CTRL, TRA (10 µg/mL) combined with PYR (100 nmol/L) or PER (10 µg/mL) for the indicated times. The levels of pHER2, HER2, pAKT, AKT, pERK, ERK, and GAPDH were assessed by western blot. The quantifications of blots are shown in Supplementary Figure S3. TRA, trastuzumab; PYR, pyrotinib; PER, pertuzumab; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001.

Figure S3.

Pyrotinib is superior to pertuzumab in inhibiting HER2 downstream pathways in HER2+ breast cancer cells. SK-BR-3 (A), BT-474 (B), HCC1569 (C), and HCC1954 (D) cells were treated with CTRL, TRA (10 µg/mL) combined with PYR (100 nmol/L) or PER (10 µg/mL) for the indicated times. The levels of pHER2, HER2, pAKT, AKT, pERK, ERK, and GAPDH were assessed by western blot. The quantifications of blots are shown above. TRA, trastuzumab; PYR, pyrotinib; PER, pertuzumab; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

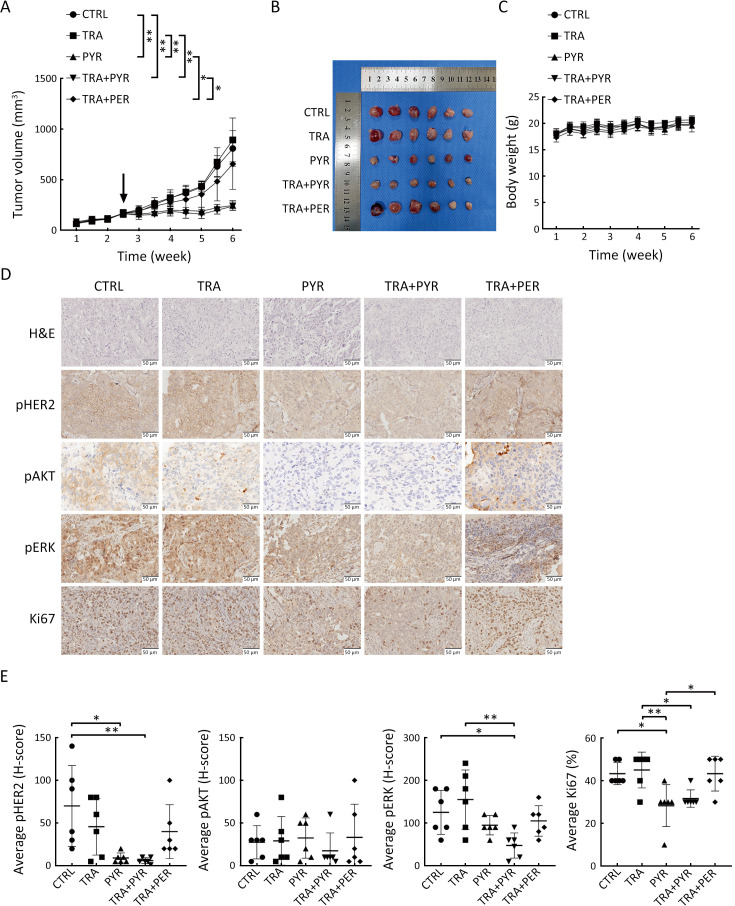

Pyrotinib is superior to pertuzumab in suppressing tumor growth in a trastuzumab-resistant xenograft model

We next evaluated the effect of pyrotinib on the growth of trastuzumab-resistant tumor cells in vivo using xenograft model established by subcutaneously injecting HCC1954 cells into the right flanks of BALB/c-nude mice. When tumor volumes reached approximately 200 mm3, mice were randomly assigned to the control group, trastuzumab group, pyrotinib group, trastuzumab plus pyrotinib group, or trastuzumab plus pertuzumab group. Tumor growth was significantly suppressed in the pyrotinib group and the trastuzumab plus pyrotinib group compared with controls; in contrast, trastuzumab or trastuzumab plus pertuzumab did not suppress HCC1954 xenograft tumor growth (Figure 4A,B). These results demonstrated that pyrotinib-containing treatments but not trastuzumab plus pertuzumab resulted in tumor regression. There was no significant difference in the body weight of mice in all treatment groups compared with the control group (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Pyrotinib is superior to pertuzumab in suppressing tumor growth in a xenograft model. (A) HCC1954 xenograft mouse model was treated with CTRL, TRA, PYR, TRA+PYR, or TRA+PER for 24 d. The black arrow indicates the initial time of treatment. Tumor volume was measured twice a week, and data are presented as  ; (B) After 24 d of treatment, mice were sacrificed, and tumors were dissected and photographed; (C) Body weight of mice was measured twice a week; data are presented as

; (B) After 24 d of treatment, mice were sacrificed, and tumors were dissected and photographed; (C) Body weight of mice was measured twice a week; data are presented as  ; (D) IHC staining was performed for pHER2, pAKT, pERK, and Ki-67 in paraffin sections of HCC1954 xenograft tumors; (E) IHC scores were quantified and presented. n=6/group. TRA, trastuzumab; PYR, pyrotinib; PER, pertuzumab; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

; (D) IHC staining was performed for pHER2, pAKT, pERK, and Ki-67 in paraffin sections of HCC1954 xenograft tumors; (E) IHC scores were quantified and presented. n=6/group. TRA, trastuzumab; PYR, pyrotinib; PER, pertuzumab; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

We performed IHC to examine pHER2, pAKT, pERK, and Ki-67 in the xenograft tumors harvested at the end of the experiment. Ki-67 expression was decreased in the pyrotinib group and trastuzumab plus pyrotinib group but not in the trastuzumab or trastuzumab plus pertuzumab groups. Furthermore, the combination of trastuzumab and pyrotinib did not result in increased effects compared with pyrotinib alone, which is consistent with the in vitro results. Moreover, pyrotinib alone inhibited Ki-67 expression to a greater extent compared with trastuzumab plus pertuzumab treatment (Figure 4D,E). Furthermore, the pyrotinib-containing treatments markedly reduced pHER2 and pERK expression compared with controls in vivo. Pyrotinib plus trastuzumab treatment showed the lowest levels of pAKT expression (Figure 4D,E). These results demonstrate that pyrotinib alone or in combination with trastuzumab suppressed trastuzumab-resistant xenograft tumor growth in vivo, while trastuzumab plus pertuzumab did not.

Discussion

Despite the substantial survival benefits achieved with trastuzumab (3), some HER2+ early-stage breast cancer patients experience primary resistance to trastuzumab (4,5). In this study, we demonstrated that pyrotinib exerted anti-cancer effects on trastuzumab-sensitive and trastuzumab-resistant HER2+ breast cancer cells and inhibited PI3K/AKT and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathways. Furthermore, pyrotinib showed a stronger inhibitory effect, compared with pertuzumab, in HER2+ breast cancer cells either sensitive or primarily resistant to trastuzumab, and the trastuzumab-resistant xenograft mouse model.

Previous clinical studies have shown that pyrotinib is an effective TKI for the treatment of both early and advanced HER2+ breast cancer patients (23). The PHEDRA trial examining pyrotinib with trastuzumab plus docetaxel as neoadjuvant therapy in patients with early or locally advanced HER2+ breast cancer reported that the total pathological complete response rate was 41% (24). The phase II PANDORA trial reported that pyrotinib plus docetaxel showed promising anti-tumor activity as a first-line treatment for patients with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (25). The randomized, double blind, phase III PHILA trial of HER2+ metastatic breast cancer patients showed that pyrotinib as first-line treatment resulted in significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with the placebo (median PFS: 24.3 vs. 10.4 months) (15). In this study, we showed that pyrotinib inhibited the proliferation, migration, invasion, and HER2 downstream pathways of HER2+ breast cancer cells. These results are in line with the findings from the clinical studies, showing that pyrotinib demonstrated very promising efficacy in breast cancer.

Trastuzumab is the primary treatment option for HER2+ breast cancer in clinical practice (3,9), but resistance to trastuzumab in patients with HER2+ breast cancer often occurs in the clinical setting (26). Studies have reported that pertuzumab alone or in combination with trastuzumab is unable to treat trastuzumab resistance in trastuzumab-resistant models (11,27). However, treatment with TKIs (such as neratinib or lapatinib), which form irreversible bonds with the intracellular domains of HER proteins, have an advantage in treating HER2+ breast cancer with trastuzumab resistance (28). In patient-derived xenograft models, neratinib significantly inhibited the growth of tumors that failed trastuzumab and lapatinib treatment (27). Nevertheless, the efficacy of lapatinib and neratinib did not translate into long-term survival benefits in clinical trials (29,30). The single-arm, multicenter, phase II PICTURE trial reported that in HER2+ advanced breast cancer patients with primary resistance to trastuzumab, the combination therapy of pyrotinib plus capecitabine resulted in a median PFS of 11.8 months, which crossed the pre-specified efficacy boundary of 8.0 months (16). Our latest clinical research results showed that compared with trastuzumab alone, the addition of pyrotinib with trastuzumab for another four cycles significantly improved the pathological complete response rate in non-responding HER2+ breast cancer patients who received two-cycle neoadjuvant trastuzumab plus chemotherapy (31). These findings indicate the efficacy of pyrotinib in treating trastuzumab primary resistance.

The mechanisms of primary resistance to trastuzumab have been previously described (32-34). In this study, we evaluated the effects of pyrotinib in HER2+ breast cancer cell lines (HCC1569 and HCC1954) with primary resistance to trastuzumab. The HCC1569 cell line is deficient for the expression of phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN) (35), and loss of PTEN was proven to reduce the efficacy of HER2-targeted therapy (36). The HCC1954 cell line contains a PI3K mutation (37), which leads to the continuous activation of downstream AKT. Trastuzumab and pertuzumab interact with the extracellular domain of HER2 and block HER2/HER3 dimerization but may fail to block continuous activation of PI3K/AKT. Pyrotinib binds the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain of the HER1, HER2 and HER4 receptors, which irreversibly inhibits tyrosine phosphorylation. Our results showed that the pyrotinib-containing treatments inhibited cell proliferation in vitro and tumor growth in vivo in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells, while pertuzumab plus trastuzumab could not. Further mechanistic study indicated that activation of HER2 downstream PI3K/AKT and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathways was inhibited by pyrotinib-containing treatments in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells, while the inhibitory effect of pertuzumab plus trastuzumab was very slight. These results showed that pyrotinib demonstrated superior efficacy compared with pertuzumab in inhibiting HER2 signaling in trastuzumab-resistant breast cancer cells.

A recent clinical study showed that the efficacy of neoadjuvant pyrotinib in locally advanced HER2+ breast cancer was independent of PI3K catalytic subunit p110α (PIK3CA) status (38). In a phase I study of pyrotinib for HER2+ metastatic breast cancer, PIK3CA and TP53 mutations in archival primary tumor samples were not associated with objective response (21). These findings may further support our results and suggest the benefit of pyrotinib in treating trastuzumab resistance induced by PIK3CA mutation.

In clinical studies of neoadjuvant therapy with pyrotinib, the most common grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events were diarrhea (15.5%−45.28%) (38-40). However, grade 3 diarrhea mainly occurred during the first cycle of treatment and the incidence did not increase thereafter (12,14,24,38). In our study, we did not find a significant decrease in body weight in the pyrotinib-containing treatment groups compared with controls, indicating the effective dose in our model was well tolerated. This dose was lower than the recommended human equivalent dose.

In our study, we found that acute trastuzumab or pyrotinib treatment led to increased pERK, which has also been reported elsewhere (41,42). The reason why inhibitors activate the ERK1/2 pathway may be related to the increased dimerization of epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR)/HER2 and HER2/HER4 caused by the increase of endogenous ligands (41,42). As EGFR, HER3, and HER4 have binding sites for src homology 2 domain-containing (Shc) and growth factor receptor bound protein 2 (Grb2) (43), and these two proteins are upstream molecules of MAPK/ERK, their activation would account for the increased activation of ERK by acute inhibitor treatment.

Several clinical implications can be drawn from our study. First, pyrotinib can be used in combination with trastuzumab for trastuzumab-sensitive HER2+ breast cancer, especially in treatment-naïve patients. Second, treatment with pyrotinib is superiorly effective to the antibody pertuzumab in patients with primary resistance to trastuzumab therapy, and our study demonstrated a possible mechanism of treating trastuzumab resistance by pyrotinib. Further head-to-head comparation between the two dual-targeted regimens (trastuzumab with pertuzumab or pyrotinib) in clinical trials may be needed. Third, breast cancer patients with concurrent PI3K mutations or PTEN deletions with HER2 overexpression may be less likely to respond optimally to trastuzumab and pertuzumab regimens, and pyrotinib may be a more effective option. Fourth, for patients with primary resistance to trastuzumab, it is necessary to conduct pathological evaluation of the tumor to determine whether PI3K mutation or PTEN loss has occurred; in these cases, the addition of pyrotinib may have better clinical benefits.

Our study has several limitations: 1) BT-474 is a breast cancer cell line with estrogen receptor (ER)+/HER2+ status; however, we did not examine the use of anti-estrogen receptor therapy in this study; and 2) Trastuzumab, an antibody targeting extracellular HER2, can induce antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxic effects; however, we did not examine T cell or natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxic effect in vitro, which was a deficiency of our study and might lead to different results compared to other research.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that pyrotinib-containing treatments exerted anti-cancer effects on HER2+ breast cancer cells sensitive to trastuzumab and with primary resistance to trastuzumab, and inhibited HER2 downstream pathways. Furthermore, pyrotinib plus trastuzumab was more beneficial than pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in HER2+ breast cancer cells and breast cancer tumors with primary resistance to trastuzumab in mice. These findings provide a pre-clinical basis for exploring pyrotinib plus trastuzumab as a dual-targeted therapy for HER2+ breast cancer with primary resistance to trastuzumab.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82072914); the Special Foundation for Taishan Scholars and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2022JC009).

Contributor Information

Shuya Huang, Email: huangsya@sdu.edu.cn.

Zhigang Yu, Email: yuzhigang@sdu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Pondé N, Brandão M, El-Hachem G, et al Treatment of advanced HER2-positive breast cancer: 2018 and beyond. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;67:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiang H, Xin L, Ye J, et al A multicenter study on efficacy of dual-target neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer and a consistent analysis of efficacy evaluation of neoadjuvant therapy by Miller-Payne and RCB pathological evaluation systems (CSBrS-026) Chin J Cancer Res. 2023;35:702–12. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2023.06.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez Marti JL, Nasrazadani A, Ding Y, et al Twenty-year follow-up of a phase II trial of taxotere/carboplatin/herceptin in patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer. Oncologist. 2023;28:e1123–6. doi: 10.1093/oncolo/oyad258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X, Wang J, Fan Y, et al Primary trastuzumab resistance after (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab-containing treatment for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer in real-world practice. Clin Breast Cancer. 2021;21:191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin-Castillo B, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Vazquez-Martin A, et al Basal/HER2 breast carcinomas: integrating molecular taxonomy with cancer stem cell dynamics to predict primary resistance to trastuzumab (Herceptin) Cell Cycle. 2013;12:225–45. doi: 10.4161/cc.23274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pernas S, Tolaney SM. HER2-positive breast cancer: new therapeutic frontiers and overcoming resistance. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2019;11:1758835919833519.

- 7.Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, et al Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Jiang Z Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer (CSCO BC) guidelines in 2022: stratification and classification. Cancer Biol Med. 2022;19:769–73. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2022.0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China National guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer 2022 in China (English version) Chin J Cancer Res. 2022;34:151–75. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2022.03.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Amico S, Krasnowska EK, Manni I, et al DHA affects microtubule dynamics through reduction of phospho-TCTP levels and enhances the antiproliferative effect of T-DM1 in trastuzumab-resistant HER2-positive breast cancer cell lines. Cells. 2020;9:1260. doi: 10.3390/cells9051260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canonici A, Ivers L, Conlon NT, et al HER-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors enhance response to trastuzumab and pertuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2019;37:441–51. doi: 10.1007/s10637-018-0649-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma F, Ouyang Q, Li W, et al Pyrotinib or lapatinib combined with capecitabine in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer with prior taxanes, anthracyclines, and/or trastuzumab: A randomized, phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2610–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Yang C, Wan H, et al Discovery and development of pyrotinib: A novel irreversible EGFR/HER2 dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor with favorable safety profiles for the treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;110:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu B, Yan M, Ma F, et al Pyrotinib plus capecitabine versus lapatinib plus capecitabine for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (PHOEBE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:351–60. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma F, Yan M, Li W, et al Pyrotinib versus placebo in combination with trastuzumab and docetaxel as first line treatment in patients with HER2 positive metastatic breast cancer (PHILA): randomised, double blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. BMJ. 2023;383:e076065. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-076065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao J, Teng Y, Li H, et al Pyrotinib plus capecitabine for trastuzumab-resistant, HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (PICTURE): a single-arm, multicenter phase 2 trial. BMC Med. 2023;21:300. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02999-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye C, Zhou W, Wang F, et al Prognostic value of gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase expression in female patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2022;150:705–17. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.An W, Yao S, Sun X, et al Glucocorticoid modulatory element-binding protein 1 (GMEB1) interacts with the de-ubiquitinase USP40 to stabilize CFLAR and inhibit apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:181. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1182-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin G, Liu L, Yu T, et al Genomic and transcriptomic analysis of breast cancer identifies novel signatures associated with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Genome Med. 2024;16:11. doi: 10.1186/s13073-024-01286-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins DM, Conlon NT, Kannan S, et al Preclinical characteristics of the irreversible pan-HER kinase inhibitor neratinib compared with lapatinib: implications for the treatment of HER2-positive and HER2-mutated breast cancer. Cancers. 2019;11:737. doi: 10.3390/cancers11060737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma F, Li Q, Chen S, et al Phase I study and biomarker analysis of pyrotinib, a novel irreversible pan-ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3105–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.6179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agus DB, Gordon MS, Taylor C, et al Phase I clinical study of pertuzumab, a novel HER dimerization inhibitor, in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2534–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blair HA Pyrotinib: First global approval. Drugs. 2018;78:1751–5. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0997-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Jiang Z, Liu Z, et al Neoadjuvant pyrotinib, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive breast cancer (PHEDRA): a double-blind, randomized phase 3 trial. BMC Med. 2022;20:498. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02708-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Y, Cao WM, Shao X, et al Pyrotinib plus docetaxel as first-line treatment for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer: the PANDORA phase II trial. Nat Commun. 2023;14:8314. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44140-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo L, Zhang Z, Qiu N, et al Disruption of FOXO3a-miRNA feedback inhibition of IGF2/IGF-1R/IRS1 signaling confers Herceptin resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer. Nat Communications. 2021;12:2699. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23052-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veeraraghavan J, Gutierrez C, Sethunath V, et al Neratinib plus trastuzumab is superior to pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer xenograft models. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021;7:63. doi: 10.1038/s41523-021-00274-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao W, Bian L, Wang T, et al Effectiveness of second-line anti-HER2 treatment in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients previously treated with trastuzumab: A real-world study. Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32:361–9. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.03.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huober J, Holmes E, Baselga J, et al Survival outcomes of the NeoALTTO study (BIG 1-06): updated results of a randomised multicenter phase III neoadjuvant clinical trial in patients with HER2-positive primary breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2019;118:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmes FA, Moy B, Delaloge S, et al Overall survival with neratinib after trastuzumab-based adjuvant therapy in HER2-positive breast cancer (ExteNET): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Eur J Cancer. 2023;184:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu ZG, Xiong B, Yang Z, et al The addition of pyrotinib in early or locally advanced HER2-positive breast cancer patients with no response to two cycles of neoadjuvant therapy: A prospective, multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:S428. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maadi H, Soheilifar MH, Choi WS, et al Trastuzumab mechanism of action; 20 years of research to unravel a dilemma. Cancers. 2021;13:3540. doi: 10.3390/cancers13143540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burguin A, Diorio C, Durocher F Breast cancer treatments: updates and new challenges. J Pers Med. 2021;11:808. doi: 10.3390/jpm11080808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanley A, Ashrafi GH, Seddon AM, Modjtahedi H Synergistic effects of various Her inhibitors in combination with IGF-1R, C-MET and Src targeting agents in breast cancer cell lines. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3964. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04301-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azimi I, Milevskiy MJG, Kaemmerer E, et al TRPC1 is a differential regulator of hypoxia-mediated events and Akt signalling in PTEN-deficient breast cancer cells. J Cell Sci. 2017;130:2292–305. doi: 10.1242/jcs.196659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagata Y, Lan KH, Zhou X, et al PTEN activation contributes to tumor inhibition by trastuzumab, and loss of PTEN predicts trastuzumab resistance in patients. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu XL, Liu JL, Xu YC, et al Membrane metallo-endopeptidase mediates cellular senescence induced by oncogenic PIK3CAH1047R accompanied with pro-tumorigenic secretome. Int J Cancer. 2019;145:817–29. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin W, Wang Y, Wu Z, et al Neoadjuvant trastuzumab and pyrotinib for locally advanced HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoATP): Primary analysis of a phase II study. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:3677–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding Y, Mo W, Xie X, et al Neoadjuvant pyrotinib plus trastuzumab, docetaxel, and carboplatin in early or locally advanced human epidermal receptor 2-positive breast cancer in China: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Oncol Res Treat. 2023;46:303–11. doi: 10.1159/000531492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao X, Lv P, Gong Y, et al Pyrotinib-containing neoadjuvant therapy in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:855512. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.855512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dokmanovic M, Wu Y, Shen Y, et al Trastuzumab-induced recruitment of Csk-homologous kinase (CHK) to ErbB2 receptor is associated with ErbB2-Y1248 phosphorylation and ErbB2 degradation to mediate cell growth inhibition. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:1029–41. doi: 10.4161/cbt.29171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gijsen M, King P, Perera T, et al HER2 phosphorylation is maintained by a PKB negative feedback loop in response to anti-HER2 herceptin in breast cancer. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cantor AJ, Shah NH, Kuriyan J Deep mutational analysis reveals functional trade-offs in the sequences of EGFR autophosphorylation sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E7303–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803598115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]